Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 4. Münzen. -- Fassung vom 2008-04-11. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen04.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2008-03-18

Überarbeitungen: 2008-04-11 [Ergänzungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Da ich (Alois Payer) in indischer Numismatik ein absoluter Laie bin, zitiere ich im Folgenden ausgiebig aus den Werken von Fachleuten. Aus Gründen des Copyrights kann ich hauptsächlich nur ältere Werke verwenden. Wenn diese auch in Einzelheiten überholt sind, geben sie doch einen guten Einblick in das Gebiet der indischen Münzen als Geschichtsquelle.

| "Splendid collections of coins might be made in this country. They

are found principally at Manikyala, Djlun, Pind-dadan Khan, at Nili

Daulla, Raval Pindi, and in the districts of the Hazaris and Hazaros.

They were formerly worked up into lotas and cooking vessels, and

ornaments. It was only in 1829, the period when my researches

commenced, that the inhabitants began to appreciate their value. The

copper coins are most numerous; the fear of being supposed to have

dug up a treasure leads the inhabitants to melt up those of silver

and gold, which makes their preservation comparatively rare." [Quelle: Court, Claude Auguste <1793- ? >: Further Information on the Topes of Manikyala. -- In: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. -- 1834. -- Abgedruckt in: A source-book of Indian archaeology / ed. by F. Raymond Allchin .... -- New Delhi : Manoharlal. -- Vol 1: Background. Early methods. Geography, climate and early man domestication of plants and animals. - 1979. - X, 354 S. : Ill. -- S. 107. -- Nach diesem Nachdruck wiedergegeben.] |

Numismatik (Münzkunde) hat sich von der "Münzbelustigung" von Liebhaber-Sammlern zu einer eigenständigen Wissenschaft entwickelt. Meist nur unter Beiziehung entsprechender Spezialisten kann ein Historiker Münzen als Quellen verwenden. Ahasver von Brandts Bemerkungen zur europäischen Numismatik gelten ebenso für die indische Numismatik:

"Allgemein gesehen hat sich die Numismatik in neuerer Zeit in zwei Richtungen weiterentwickelt. Im engeren Sinne hat sie als Lehre von den Münzen die Auswertung dieser konkreten Überreste als Quelle für fast alle Bereiche des menschlichen Gemeinschaftslebens betont und ermöglicht. In erweitertem Sinne hat sie als »Geldgeschichte« unter Einbeziehung auch anderer Geldformen und unter Erforschung der theoretischen, metrologischen und wirtschaftlichen Grundlagen der monetären Entwicklung sich zu einer historischen »Zweigwissenschaft«, einem autonomen Teil der Wirtschaftsgeschichte ausgebildet. In diesem Sinne unterscheidet sie sich z. B. von der Siegelkunde, bei der die i. e. S. »hilfswissenschaftliche« Betrachtungsweise durchaus vorherrscht. Die Numismatik ist ein weitgehend autonomes Fach geworden, insofern — von unserem Standpunkt aus gesehen — am ehesten der methodischen und fachlichen Sonderstellung der Historischen Geographie zu vergleichen. Das heißt, dass hier eine eigene Methodik, mit ungemein ausgebreiteter eigener Fachliteratur, entstanden ist, deren Beherrschung und Anwendung dem allgemeinen Historiker in der Regel nicht zuzumuten ist; ähnlich wie in der Geographie ist er hier vielmehr auf die Zusammenarbeit mit dem Fachmann dieses Gebietes angewiesen. Im Rahmen unserer Betrachtung können daher nur Andeutungen im Sinne des quellenkundlichen Arbeitsbereiches der eigentlichen »Münzkunde« gegeben werden." [Quelle: Brandt, Ahasver von <1909 - 1977>: Werkzeug des Historikers : eine Einführung in die historischen Hilfswissenschaften. --17. Aufl. / mit aktualisierten Literaturnachträgen und einem Nachwort von Franz Fuchs. -- Stuttgart : Kohlhammer, 2007. -- 223 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- (Kohlhammer-Urban-Taschenbücher ; Bd. 33). -- ISBN 978-3-17-019413-7. -- S. 149f.]

Funktion von Geld kann sein:

Diese drei Funktionen sind nicht notwendig aneinander gebunden und können auch durch andere Mittel als Geld erfüllt werden.

Auch in Indien kann man davon ausgehen, dass ein großer Teil wirtschaftlicher Transaktionen (besonders im ländlichen Bereich) im Tauschverkehr erfolgten. Geldwirtschaft war wohl eher ein Phänomen der Oberschichten, der staatlichen Institutionen und der Städter.

Auch Edelmetalle (Gold, Silber), die nicht die Form von Münzen haben, sondern nur abgewogen wurden waren vermutlich Mittel des Zahlungsverkehrs in Indien (z.B. Hacksilber).

Münzen sind

Münzen sind eine ganz wichtige Quelle zur Geschichte

So weit ich beurteilen kann, gibt es in diesem Gebiet bei indischen Münzen noch Pionierarbeiten zu leisten.

Eine hervorragende Anleitung zu einem "heimwerkerischen", experimentellen Zugang zur historischen Metallurgie ist:

Abb.: EinbandtitelMoesta, Hasso <1925 - >: Erze und Metalle - ihre Kulturgeschichte im Experiment. -- 2., korrigierte Aufl. -- Berlin [u.a.] : Springer, 1986. -- XI, 189 S. : Ill. ; 21 cm. -- ISBN 3-540-16561-4

Die folgenden Worte im Vorwort zur ersten Auflage seinen Indienkundigen ans Herz gelegt:

"Wir alle bewundern in Museen und Ausstellungen die Kunstwerke der Goldschmiede und Bronzegießer vergangener Jahrtausende. Wir erkennen ihr Kunstgefühl in den Formen und die Symbolik mancher Funde erschließt uns etwas von der Geisteshaltung ihrer Benutzer. Die Frage: „Wie wurde dieses Kunstwerk oder jene Waffe gemacht?" wird dabei häufig nicht oder nur unzureichend beantwortet. Dabei liegt in der Kenntnis des „Wie" neben dem „Wann" eine Fülle von Hintergrundmaterial, das ein Museumsstück zu einem Stück Menschheitsgeschichte werden lassen kann. Solches Hintergrundmaterial ist über eine Vielzahl von Wissenschaften verteilt. Dieses Buch will kulturhistorisch Relevantes aus Mineralogie, Chemie, Verfahrenstechnik und Handwerk im Wortsinne „handgreiflich" machen. Es wendet sich an den Liebhaber alter und schöner Dinge, an phantasievolle Freunde der Kulturen und ihrer Geschichte, die vor ein wenig „heimwerken" nicht zurückschrecken. Nur das Experiment kann jene Verbindung von Geist und Geschicklichkeit vermitteln, die über Jahrtausende hinweg die Fähigkeiten des Menschen gefordert, entwickelt und geprägt hat.

Die Versuchsbeschreibungen sind der Kern des Buches. Sie fordern keinerlei chemisch-experimentelle Vorbildung für ein Gelingen. Die Darlegungen aus der Geschichte sind als Hilfsmittel zur Einbettung der technisch-handwerklichen Entwicklung in den größeren Zusammenhang gedacht. Die herangezogene Literatur enthält sowohl Quellenmaterial als auch populäre Arbeiten, sie erscheint dem Autor für einen Einstieg in das Gebiet geeignet ohne Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit zu erheben."

[Quelle: Moesta, Hasso <1925 - >: Erze und Metalle - ihre Kulturgeschichte im Experiment. -- 2., korrigierte Aufl. -- Berlin [u.a.] : Springer, 1986. -- XI, 189 S. : Ill. ; 21 cm. -- ISBN 3-540-16561-4. -- S. VII-VIII.]

Anhand von Münzen der griechischen und römischen Antike zeigen die beiden Autoren folgenden Werkes in vorbildlicher, auch für den metallurgischen Laien verständlicher Weise, welche Fülle von Informationen man mit den Mitteln der Technik und Naturwissenschaften aus Münzen gewinnen kann:

Abb.: Umschlagtitel

Moesta, Hasso <1925 - > ; Franke, Peter Robert <1926 - >: Antike Metallurgie und Münzprägung : ein Beitrag zur Technikgeschichte. -- Basel [u.a.] : Birkhäuser, 1995. -- 184 S. : Ill.. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 3-7643-5166-7.

Hasso Moesta war 1970 bis 1991 Professor für Physikalische Chemie an der Universität des Saarlandes. Peter Robert Franke war von 1967 bis 1994 Professor für Alte Geschichte an der Universität des Saarlandes. Ein Schwerpunkt seiner Arbeit ist die antike Numismatik.

Münzen geben -- oft den einzigen -- Aufschluss zu

D. R. Bhandarkar, Carmichael Professor of Ancient Indian history and culture, Calcutta University, beschreibt einige der möglichen Erkenntnisse durch Münzen auf dem Gebiet der politischen Geschichte (wenn man auch seinen Schlussfolgerungen nicht unbedingt zustimmen muss):

"[S. 2] If numismatics is thus a source of history, as important as epigraphy itself, can it be shown, it may be asked, to shed light on the different aspects of the ancient Indian history ? Let us take the Political History first. It is hardly necessary for me to dwell on this point, because many of you are already aware how much beholden Political History is to this science. In a book of the ancient history of India, how often we read about the Indo-Bactrian Greek, Indo-Scythian, Indo-Parthian and Kushana kings, whose might overshadowed the north of India from about 250 B.C. to about 300 A.D. and who were either ruling conterminously or supplanting each other in succession? What would have been our knowledge of the Indo-Bactrian Greek princes, if we had not had their coins to help us? Of course, some Greek historians like Justin and Strabo have preserved an account of some of them, but this account is of four or five princes only and ranges scarcely over half a century. On the other hand, a study of their coins reveals to us no less than thirty- seven [S. 3] such Greek princes,1 whose sway extends over two centuries and a half. The condition of their contemporaneous barbarian potentates, viz., the Indo-Scythians,2 was even worse. Who would have heard at all of Vonones, Spalirises, Spalahores, Spalagadames, Azes I, Azilises and Azes II, if their coins had not been found ? Certainly no historian or traveller, Indian or foreign, has preserved any reminiscences of them. Again, it is their coins which not only give us their names but also enable us to fix their order of succession.3 The Indo-Parthians, who overthrew the Indo-Scythians, do not seem to have fared better. Of course, there is an epigraphic record of Gondophares, the founder of the Indo-Parthian dynasty, and there is also a reference to him, perhaps of a nebulous character, preserved in the Syriac version of the Legend of the Christian Apostle, Saint Thomas. But what about his successors, Abdgases, Orthagnes, Pakores and so forth ? If coins of these latter had not been recovered, should we have ever known anything about them ? It is true that in regard to the Kushanas we are luckily in possession of a [S. 4] fairly large number of inscriptions of Kanishka, Huvishka and Vsudeva. But what about their immediate predecessors, Kujula Kadphises and Wema Kadphises, who were the first to establish and propagate Kushana supremacy ? Are we not indebted for our knowledge of these rulers to the study of their coinage ? Perhaps the most important service done by numismatics to political history is in connection with the Western Kshatrapas who ruled over Kāṭhiāwāṛ and Mālwā. The founder of this dynasty was Chashṭana, who has been identified with Tiastenes of Ozene (Ujjain), mentioned by Ptolemy, and has been assigned to circa 130 A.D. Here too, as in the case of the Indo-Bactrian Greek princes, many names of the Kshatrapa rulers have been revealed by their coins, which, again, as they give the name and title not only of the ruler but also of his father, and, what is most important, specify dates, enable us to arrange them in their order of succession and to determine sometimes even the exact year in which one Kshatrapa ruler was succeeded by another.1 Nay, a careful study of their coins enables us even to find out where and on what three occasions there was a break in the direct line from Chashṭana. 1 CCIM., 5-6.

2 I agree with Mr. Whitehead in calling them Indo-Scythian. My reasons have been set forth in IA., 1911, 13, n. 15.

3 I was the first to fix this order of succession in JBBRAS., XX, 284 & ff., which was accepted by the late Dr. V. A, Smith in ZDMG., 1906, 59 & ff.

s1 CICBM-AKTB., Intro., cliii clvii.[S. 4] Let us now turn to the Administrative History of India and see whether the study of coins has [S. 5] ever proved to be of any use there. I hope you have not forgotten the two lectures on Administrative History which I delivered here two years ago. I had then occasion to bring into requisition the various items of information supplied on this point by Indian numismatics. Especially in the second of these lectures, which was concerned with the Saṃgha form of government I drew your prominent attention to three types of Collegiate Sovereignty denoted by the terms Gaṇa, Naigama and Janapada. Gaṇa I then told you, was an oligarchy and was thus a distinct political form of government. This conclusion was in the main based upon Chapter 107 of the Śāntiparvan of the Mahābhārata, but received corroboration from what we knew from numismatics. At least three types of coins have been brought to light which were issued by three different Gaṇas, viz., the Mālavas, Yaudheyas and Vṛishṇis.1 That all of them were Gaṇas was already known to us from inscriptions and Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra. And it may, therefore, perhaps be argued that these coins teach us nothing new. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that they possess great corroborative value, which cannot be ignored in a subject connected with Administrative History, which is still in its infancy. Although in respect of Gaṇa numismatics does not [S. 6]

1 CL., 1918. 157 & 166.

thus furnish us with new information, its value in respect of the other forms of Saṃgha government cannot be denied. In that second lecture of mine on Administrative History, I have clearly shown that side by side with oligarchy, democracy of a two-fold kind was flourishing in ancient India, one styled Naigama which was confined to a town, and the other Janapada which extended over a province. Of course, I am not here referring to the power which the people of towns and provinces, called Paura and Jānapada respectively, sometimes wielded in the administration of a country, and which is often alluded to in the epics and sometimes in works on law, but which was never of a political character. I am here referring to those cities and countries which enjoyed political autonomy and whose existence has been attested by coins alone. I hope you remember I mentioned one type of coins found in the Punjab on the obverse of which you find the word Negamā, i.e., Naigamāḥ, and on the reverse such names as Dojaka, Tālimata, Atakatakā and so forth, and told you that they were really the civic coins struck by the peoples of these cities.1 This, no doubt, reminds us of similar coinages of Phocaea, Cyzicus and other Greek cities,2 and further points to the fact that the Naigama or civic [S. 7] autonomy was as conspicuous among the Hindus of the old Punjab as among the Greeks on the Western coast of Asia Minor. That a country autonomy, or Janapada as it was called, was not unknown to India is similarly clear from a study of coins only. Thus we have two types of coins, one of which was issued by the Rājanya Janapada and the other by the Śibi Janapada of the Mādhyamikā country.1 A few other interesting facts connected with Administrative History are also revealed by numismatics, but it will take me long to mention them. Two administrative puzzles furnished by it I will, however, mention here by way of curiosity. Those of you who have critically examined the coins of the Indo-Scythian dynasty must have already been faced with one of these puzzles. Four kings of this family are Spalirises, Azes I, Azilises and Azes II. Now, the peculiarity of the coins of these princes is that over and above those each issues in his name alone, he strikes coins conjointly with his predecessor and his successor, but with this difference that in the first case his name appears on the Kharoshṭhī reverse and that of his predecessor on the Greek obverse, and in the second case his name on the Greek obverse and that of his successor on the Kharoshṭhī reverse. What is, however, puzzling is that the [S. 8] titles of the prince on the Greek obverse are of exactly the same political rank as those of the prince on the Kharoshṭhī reverse. Thus to take one instance, viz., that of Azes I and Azilises, the former is styled Basileōs Basileōn Megalou Azou and the latter Maharajasa rajarajasa mahatasa Ayilisasa. Here the titles Maharaja rajaraja mahata, which have been coupled with the name of Ayilisa, i. e., Azilises, are the exact translation in Prakrit of the Greek titles Basileōs Basileōn Megalou associated with the name of Azes. The titles are thus exactly identical, showing apparently that the two rulers wielded the same degree of political power. But how is this possible? because Azilises is the heir-apparent and Azes the real king. According to Hindu polity a Yuvarāja cannot possibly be assigned to the same political rank as his father the Mahārja. Such was also not the case with the many foreign tribes who established a kingdom in India. Take, e. g., the Kshatrapa dynasty which held sway over Kāṭhiāwāṛ and Mālwā and to which I have already referred in connection with the light which numismatics throws on political history. Here on their coins and in their inscriptions the actual ruler is invariably designated Mahākshatrapa and the heir-apparent merely Kshatrapa. Hence it becomes inexplicable how in the case of the Imperial Indo-Scythian dynasty the king and the prince-royal come to assume titles of precisely [S. 9] the same political grade. This knotty point I hope some one of you will be able to solve one day.

So much for one administrative puzzle presented by the study of numismatics. I will now place another before you. I shall here come to a somewhat later period, viz. the Gupta period, and fix your attention on the coins of the founder of this dynasty. On the obverse are the figures of a king and his queen, who from the legends appear to be no other than Chandragupta I and his wife Kumāradevī, and on the reverse the legend has Licchavayaḥ, i.e. the Lichchhavis. What is the significance of these names ? Those who are numismatists need not be told that as the name of the Lichchhavis occurs on the reverse, they had evidently become subordinate to Chandragupta I. But how did they come to occupy this subordinate position ? Did Chandragupta conquer them ? This does not appear to be possible, because his son Samudragupta calls himself with pride Licchhavi-clauhitra, "the daughter's son of a Lichchhavi." This Lichchhavi father-in-law of Chandragupta could not have been a ruler of Nepāl as conjectured by Dr. Fleet. Before the conquest of Nepāl the Lichchhavis according to their tradition ruled at Pushpapura or Pāṭaliputra, and this is confirmed by one of the Nepāl inscriptions published by Pandit Bhagwanlal Indraji.1 The Lichchhavis, [S. 10] you know, were an oligarchic tribe and consisted not of one bat of many chiefs who ruled conjointly.1 How could they have become subordinate to Chandragupta even through this matrimonial alliance ? This is the real puzzle presented by Chandragupta's coins. Perhaps the solution is that he was already married to a Lichchhavi princess, and in some battle or through some such catastrophe all the Lichchhavi chiefs and their heirs were killed, leaving no male issue behind and leaving the whole state as patrimony to Kumāradevī, queen of Chandragupta. Kumāradevī thus through succession came to be the ruler of Pāṭaliputra and the surrounding Lichchhavi territory, and, being a Hindu wife, her husband was naturally associated with her in this rule. But that Kumāradevī was an actual ruler is seen from the fact that along with Chandragupta's her figure appears on the obverse of his coins. I do not claim any finality for the solution I have proposed, and I have no doubt that some one amongst you will suggest a better solution.

1 CL., 1918, 176.

2 The Gold Coinage of Asia before Alexander the Great by Percy Gardner, 32.

1 CL., 173.

1 IA., IX, 178, v. 7.[S. 4] Let us now turn to the Administrative History of India and see whether the study of coins has [S. 5] ever proved to be of any use there. I hope you have not forgotten the two lectures on Administrative History which I delivered here two years ago. I had then occasion to bring into requisition the various items of information supplied on this point by Indian numismatics. Especially in the second of these lectures, which was concerned with the Saṃgha form of government I drew your prominent attention to three types of Collegiate Sovereignty denoted by the terms Gaṇa, Naigama and Janapada. Gaṇa I then told you, was an oligarchy and was thus a distinct political form of government. This conclusion was in the main based upon Chapter 107 of the Śāntiparvan of the Mahābhārata, but received corroboration from what we knew from numismatics. At least three types of coins have been brought to light which were issued by three different Gaṇas, viz., the Mālavas, Yaudheyas and Vṛishṇis.1 That all of them were Gaṇas was already known to us from inscriptions and Kauṭilya's Arthaśāstra. And it may, therefore, perhaps be argued that these coins teach us nothing new. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that they possess great corroborative value, which cannot be ignored in a subject connected with Administrative History, which is still in its infancy. Although in respect of Gaṇa numismatics does not [S. 6]

1 CL., 1918. 157 & 166.

thus furnish us with new information, its value in respect of the other forms of Saṃgha government cannot be denied. In that second lecture of mine on Administrative History, I have clearly shown that side by side with oligarchy, democracy of a two-fold kind was flourishing in ancient India, one styled Naigama which was confined to a town, and the other Janapada which extended over a province. Of course, I am not here referring to the power which the people of towns and provinces, called Paura and Jānapada respectively, sometimes wielded in the administration of a country, and which is often alluded to in the epics and sometimes in works on law, but which was never of a political character. I am here referring to those cities and countries which enjoyed political autonomy and whose existence has been attested by coins alone. I hope you remember I mentioned one type of coins found in the Punjab on the obverse of which you find the word Negamā, i.e., Naigamāḥ, and on the reverse such names as Dojaka, Tālimata, Atakatakā and so forth, and told you that they were really the civic coins struck by the peoples of these cities.1 This, no doubt, reminds us of similar coinages of Phocaea, Cyzicus and other Greek cities,2 and further points to the fact that the Naigama or civic [S. 7] autonomy was as conspicuous among the Hindus of the old Punjab as among the Greeks on the Western coast of Asia Minor. That a country autonomy, or Janapada as it was called, was not unknown to India is similarly clear from a study of coins only. Thus we have two types of coins, one of which was issued by the Rājanya Janapada and the other by the Śibi Janapada of the Mādhyamikā country.1 A few other interesting facts connected with Administrative History are also revealed by numismatics, but it will take me long to mention them. Two administrative puzzles furnished by it I will, however, mention here by way of curiosity. Those of you who have critically examined the coins of the Indo-Scythian dynasty must have already been faced with one of these puzzles. Four kings of this family are Spalirises, Azes I, Azilises and Azes II. Now, the peculiarity of the coins of these princes is that over and above those each issues in his name alone, he strikes coins conjointly with his predecessor and his successor, but with this difference that in the first case his name appears on the Kharoshṭhī reverse and that of his predecessor on the Greek obverse, and in the second case his name on the Greek obverse and that of his successor on the Kharoshṭhī reverse. What is, however, puzzling is that the [S. 8] titles of the prince on the Greek obverse are of exactly the same political rank as those of the prince on the Kharoshṭhī reverse. Thus to take one instance, viz., that of Azes I and Azilises, the former is styled Basileōs Basileōn Megalou Azou and the latter Maharajasa rajarajasa mahatasa Ayilisasa. Here the titles Maharaja rajaraja mahata, which have been coupled with the name of Ayilisa, i. e., Azilises, are the exact translation in Prakrit of the Greek titles Basileōs Basileōn Megalou associated with the name of Azes. The titles are thus exactly identical, showing apparently that the two rulers wielded the same degree of political power. But how is this possible? because Azilises is the heir-apparent and Azes the real king. According to Hindu polity a Yuvarāja cannot possibly be assigned to the same political rank as his father the Mahārja. Such was also not the case with the many foreign tribes who established a kingdom in India. Take, e. g., the Kshatrapa dynasty which held sway over Kāṭhiāwāṛ and Mālwā and to which I have already referred in connection with the light which numismatics throws on political history. Here on their coins and in their inscriptions the actual ruler is invariably designated Mahākshatrapa and the heir-apparent merely Kshatrapa. Hence it becomes inexplicable how in the case of the Imperial Indo-Scythian dynasty the king and the prince-royal come to assume titles of precisely [S. 9] the same political grade. This knotty point I hope some one of you will be able to solve one day.

1 CL., 1918, 176.

2 The Gold Coinage of Asia before Alexander the Oreat by Percy Gardner, 32.

1 CL., 173.So much for one administrative puzzle presented by the study of numismatics. I will now place another before you. I shall here come to a somewhat later period, viz. the Gupta period, and fix your attention on the coins of the founder of this dynasty. On the obverse are the figures of a king and his queen, who from the legends appear to be no other than Chandragupta I and his wife Kumāradevī, and on the reverse the legend has Licchavayaḥ, i.e. the Lichchhavis. What is the significance of these names ? Those who are numismatists need not be told that as the name of the Lichchhavis occurs on the reverse, they had evidently become subordinate to Chandragupta I. But how did they come to occupy this subordinate position ? Did Chandragupta conquer them ? This does not appear to be possible, because his son Samudragupta calls himself with pride Licchhavi-clauhitra, "the daughter's son of a Lichchhavi." This Lichchhavi father-in-law of Chandragupta could not have been a ruler of Nepāl as conjectured by Dr. Fleet. Before the conquest of Nepāl the Lichchhavis according to their tradition ruled at Pushpapura or Pāṭaliputra, and this is confirmed by one of the Nepāl inscriptions published by Pandit Bhagwanlal Indraji.1 The Lichchhavis, [S. 10] you know, were an oligarchic tribe and consisted not of one bat of many chiefs who ruled conjointly.1 How could they have become subordinate to Chandragupta even through this matrimonial alliance ? This is the real puzzle presented by Chandragupta's coins. Perhaps the solution is that he was already married to a Lichchhavi princess, and in some battle or through some such catastrophe all the Lichchhavi chiefs and their heirs were killed, leaving no male issue behind and leaving the whole state as patrimony to Kumāradevī, queen of Chandragupta. Kumāradevī thus through succession came to be the ruler of Pāṭaliputra and the surrounding Lichchhavi territory, and, being a Hindu wife, her husband was naturally associated with her in this rule. But that Kumāradevī was an actual ruler is seen from the fact that along with Chandragupta's her figure appears on the obverse of his coins. I do not claim any finality for the solution I have proposed, and I have no doubt that some one amongst you will suggest a better solution.

1 IA., IX, 178, v. 7.

1 CL., 167-8."[Quelle: Bhandarkar, D. R. (Devadatta Ramakrishna) <1875-1950>: Lectures on ancient Indian numismatics. -- Calcutta : University of Calcutta, 1921. -- xii, 229 S. ; 20 cm. -- S. 2 - 10. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/lecturesonancien00bhaniala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-17. -- "Not in copyright"]

Münzen, deren Fundort bekannt ist, können helfen, Bezeichnungen für politisch-geographische Gebilde zu lokalisieren.

D. R. Bhandarkar beschreibt einige der möglichen Erkenntnisse durch Münzen auf dem Gebiet der historischen Geographie:

"[S. 10] We now turn to the sphere of Historical Geography and see what light numismatics throws on it. In this connection the coins issued by the old republics of ancient India are [S. 11] very useful. I shall give here two or three instances only. We know that the Yaudheyas were an oligarchic tribe and are mentioned in inscriptions as being opposed to Rudradāman about 150 A.D. and to Samudragupta about 330 A.D. They have also been referred to in the Mahābhārata and by Pāṇini.1 But the question arises : where are they to be located ? It is scarcely necessary for me to remind you of Pāṇini's Sūtra Janapade lup (IV. 2. 81), according to which the name of a tribe or people serves also as the name of the country occupied by them. Hence when the question is asked: 'where are the Yaudheyas to be located,' it is also meant 'which was the province occupied by them?' Now, the answer to this question can be given only by their coins, i.e., by taking into consideration the localities where the coins have been found. And we know that their coins 'are found in the Eastern Punjab, and all over the country between the Sutlej and Jumna Rivers. Two large finds have been made at Sonpath, between Delhi and Karnal.'2 It is this knowledge supplied by numismatics that enabled Sir Alexander Cunningham to identify the Yaudheyas, rightly I think, with the Johiyas [S. 12] settled along both banks of the Sutlej which part is consequently known as Johiya-bār.

1 CL., 165-7.

2 ASH:., XIV, 140; CJJ.,70.We know, again, from epigraphic records that the Mālavas were another tribe with oligarchic form of government. The present province of Mālwā which is in Central India was doubtless named after them when they were settled there. But when this province came to be called Mālwā after the Mālavas we do not exactly know, but certainly not till the Gupta period. In the time of Alexander, however, they were settled somewhere in the Punjab and have been referred to as the Malloi republic by the Greek historians who accompanied him.1 Certainly the Mālavas must have migrated through the intermediate regions before they passed from the Punjab to Central India. But it may be asked : Is there any evidence as to what this intervening province was through which they moved southwards? This evidence is furnished by their coins, which, as we know, have been picked up in large numbers in the south-east part of the Jaipur State called Nāgar-chāl in Rājputānā. As the coins here found range in date from circa 350 B.C. to circa 250 A.D., we may reasonably hold that in this period the Mālavas had established themselves in this province and must have been in occupation of that region when [S. 13] about 100 A.D. Ushavadāta, son-in-law of the Kshatrapa Nahapana, defeated them,1 as we learn from a Nāsik cave inscription. They were not then far distant from Pushkar near Ajmer.

1 CL., 158.

The migrations of the Mālavas remind us of the. migrations of another people which have been brought to light by their coins, I mean the Śibis whose coins have been found in and near Nagarī not far from Chitorgaṛh in Rājputānā and who have been called not a Gaṇa but Janapada. Of course, from the Mahābhārata and also from an inscription we know that the Śibis originally belonged to the Punjab,2 but coins show that some of them were settled in the Chitorgaṛh district shortly before Christ. It is curious, however, that the province so occupied by them is not called Śibi after them, but Madhyamikā, as is quite clear from their coin legend. In one of my lectures, I informed you that the province of Madhyamikā has been mentioned both in the Mahābhārata and Varāhamihira's Bṛihat-sahitā,3 and that Madhyamikā was in reality the name of both the province and its principal town as Avanti and Ayodhyā no doubt were. The coins thus enable us to identify the city of Madhyamikā with Nagarī, near Chitorgaṛh, which, as I have [S. 14] elsewhere shown, contains the ruins of a large town.1 The significance of this identification will flash on you. You are aware that Patañjali in his Mahābhāshya gives two instances of laṅ, viz., aruṇad-= Yavanaḥ Sāketam and aruṇad= Yavano Madhyamikām, to show that the past event denoted by this laṅ must be such as is capable of being witnessed by the speaker. Patañjali thus evidently gives us to understand that the city of Madhyamikā was besieged by a Yavana or Greek prince shortly before he wrote. And naturally curiosity centred round the location of this Madhyamikā. This curiosity, we know, was gratified by the study of coins only, i.e., by the occurrence of the name Madhyamikā on the coins of the Śibi Janapada. We thus see that this Madhyamikā can be no other than Nagarī itself, as far south as which place the Greek prince, whosoever he was, pushed forward in his expedition of conquest when Patañjali lived and wrote.

1 IA., 1918, 75.

2 MASI, 123-4.

3 CL., 173, u. 3 ; MASI., 124-5.

1 MASI., 125 and ff."[Quelle: Bhandarkar, D. R. (Devadatta Ramakrishna) <1875-1950>: Lectures on ancient Indian numismatics. -- Calcutta : University of Calcutta, 1921. -- xii, 229 S. ; 20 cm. -- S. 10 - 14. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/lecturesonancien00bhaniala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-17. -- "Not in copyright"]

Münzen können u.a. Quellen sein für:

Münzumlauf: Vor allem bei Gold- und Silbermünzen ist wegen ihrer Weichheit der Gewichtsverlust durch einen längeren Umlauf nicht unbedeutend (Umlaufverlust).

Siehe die experimentellen Befunde von:

Kosambi, D. D. (Damodar Dharmanand) <1907-1966>: The effect of circulation upon the weight of metal currency. -- In: Current Science. -- 11 (1942). -- S. 227 - 231. -- Wieder abgedruckt in: Kosambi, D. D. (Damodar Dharmanand) <1907-1966>: Indian numismatics. -- New Delhi : Orient Longman, 1981. -- x, 159 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN 0861310187. -- S. 95 - 102

D. R. Bhandarkar unterscheidet Beiträge der Münzen zur

D. R. Bhandarkar beschreibt einige der möglichen Erkenntnisse durch Münzen auf dem Gebiet der Religionsgeschichte:

"[S. 14] So much for the light which numismatics sheds on the ancient Geography of India. Let us now see what its utility is for the History of Religion. Religious history is of two kinds, viz., socio-religious and mytho-religious. We shall first confine our attention, briefly, of course, to socio-religious history. The most important fact in this connection is the adoption of Hindu [S. 15] religion by, and absorption into Hindu Society of, the foreign tribes which poured into India from time to time. This subject has been handled at full length by me in a paper entitled Foreign Elements in the Hindu population.1 Epigraphic records are of great service in this respect, but numismatics is by no means far behind. What is noteworthy here is that not only did these foreigners embrace Hinduism, i.e., Buddhism or Brahmanism, but that some of them also actually adopted Hindu names. Thus Gondophares, the founder of the Indo-Parthian dynasty, has one type of coins on the reverse of which figures Śiva holding a trident.2 Similarly on at least two types of coins of Wema Kadphises, the second ruler of the Kushana family, we find Śiva bearing a trident, sometimes with his bull Nandin behind and sometimes with gourd and tiger skin.3 Here then we have two foreign kings who had become worshippers of Śiva and consequently followers of Brahmanism. The case was, however, different with Wema Kadphises' successors, Kanishka, Huvishka and Vāsudeva. Here we notice great eclecticism practised by those Kushana rulers in the matter of religious faith. We find very few Greek, many Iranian, and only some Hindu divinities selected for [S. 16] worship. This indicates a curious religious cast of mind with these Kushana sovereigns, and this sort of eclecticism we never find again in the religious history of India. But be it noted that this singular trait of religious mind evinced by these Kushanas in deducing a pantheon of their own by a selection from among the deities of various religions, which is of extreme importance for the religious history of any country, is made known to us for the first time not by epigraphy but numismatics only. Now, among the Indian divinities worshipped by these foreigners the most pre-eminent is, of course, Buddha, who, however, figures indubitably on the coins of Kanishka alone. There is nothing strange in this as Kanishka is looked upon as a patron of Buddhism. There can be no doubt in regard to the identity of Buddha on Kanishka's coins as he has been actually so named on them. And this is a very important piece of information and conveyed to us by numismatics only, because this is the earliest human representation of Buddha1 known to us so far which can be assigned to the reign of any particular king. Although Kanishka was a devotee of Buddha, he had not given up the Kushana family worship of Śiva, which god [S. 17] also appears on some of his coins,1 and also on those of Huvishka and Vāsudeva. The name of this god, as it appears on their coins, consists of four Greek letters ΟΗÞΟ, which has puzzled many numismatists. They are all convinced that the god so represented is no other than Śiva, but his name has baffled all their attempt at decipherment. Some numismatists equate it with Ugra (Śiva),2 some see in it some connection with ukshan or vṛisha,3 the bull of Śiva, and others take it to stand for Bhaveśa.4 But none of these readings can be considered satisfactory, because the word ukshan or vṛisha by itself can hardly denote Śiva; and Bhaveśa and Ugra, although they are names of Śiva, can hardly be represented in sound by the four Greek characters. Now, the second of these four letters, as I have just said is Η. Knowing as numismatists do how Η is confounded with M in the Kushana period, I feel no hesitation in reading the letters to be ΟMÞΟ, and taking them to stand for Umeśa.5 The worship of Śiva seems to have been continued by the Scvtho-Sassanians who succeeded [S. 18] the Kushanas. We thus have coins of Varahran V. (A.D. 422-440), the reverse of which bears Śiva and bull.1 This Śiva-bull type is afterwards found on the coins of only one king, viz., Śaśāṅka, king of Gauḍa (A.D. 600-625).2 But Śiva is not the only divinity that was worshipped. Other deities connected with him are found represented either jointly or severally on the coins of Huvishka, viz., Skanda, Kumāra, Viśākha and Mahāsena. Nay, an instance is not wanting of even the bull of Śiva being worshipped by these foreigners. Thus on some coins of Mihirakula, the most powerful Hūṇa potentate, we have a bull-emblem of Śiva with the legend jayatu vṛishaḥ on the reverse.3 1 IA., 1911, 7 and ff.

2 BMCOSKl., lviii and 104; JRAS., 1903, 285; CCPML., 151-2.

3 BUCGSKI., 124 and ff ; CCIM., 68 ; CCPML., 183.

1 Perhaps this goes back to the reign of his predecessor Kadaphes, because one coin-type on which his name is illegible but which on other grounds has been attributed to him, has on the obverse Buddha seated in conventional attitude (JASB., 1897, 300; CCPML , 181).1 BMCGSKL, 132; CCIM.. 74; CCPML., 187.

2 BMCGSKI., lxv.

3 Revue Numisinatique, 1888, 207 ; NChr., 1892, 62 ; JRAS., 1907. 1045, n.l.

4 JRAS., 1897, 323.

5 The name of Umā occurs on a coin of Huvishka (NChr., 1892., pl. XIII. 1) where M is twice written like H (JBAS,, 1897, 324).

1 C., pl. II, No. 15.

2 CCGD., 147.

3 CCIM., 236.As regards the adoption of Hindu names, there is but one instance among the foreign princes so far noted, viz., Vāsudeva, successor of Huvishka. But if you turn to the Kshatrapa dynasty which held Surāshṭra and Mālwā, you will find that except two all the twenty-seven names of these rulers supplied to us by their coins are distinctly Hindu. The founder of this family was, of course, Chashṭana, and his father's name was Ysāmotika, Both these names are Scythic and therefore foreign. But immediately after Chashṭana we begin to get a [S. 19] string of Hindu names, such as Jayadāman, Rudradāman and so forth, and as if to remind us that these Hindu names were borne by princes of alien extraction, we find immediately after Rudradāman the name Dāmaysada, about whose foreign origin no doubt can arise.

Let us now see whether a study of coins can prove itself useful in the sphere of mytho-religious history. A short while ago I told you that Gondophares and the Kushana rulers were devotees of Śiva and that this god was represented on the reverse of their coins. Evidently Śiva here figures as an object of worship. But how is Śiva worshipped now-a-days ? Do the Hindus worship this deity under his man-like representation, i.e., do they worship his image holding a trident and tiger-skin and standing near his bull, as we no doubt find him on the coins of these Indo-Scythian kings? Do they not invariably worship him under the form of Liṅga ? Of course, images of Śiva as on these coins are by no means unknown at the present day or even as far back as the post-Gupta period, but certainly they are not now, and were never then, objects of worship. On the coins of these foreign rulers, however, the figure of Śiva has no significance except as an object of worship, and yet we find on them not a Liṅga but a regular representation of Śiva. This clearly shows that up to the time of the Kushana [S. 20] king Vāsudeva at any rate, Śiva worship had not come to be identified with Liṅga worship. Of course, from Patañjali's Mahābhāshya on Pāṇini's Sūtra, jivik-ārthe ch-āpaṇye we learn that till his time, i.e., the middle of the second century B.C., an image of Śiva and not phallus was made for worship.1 But now we know that till the seventh century A.D., at any rate. Śiva in his human form continued to be worshipped, though already in the beginning of the Gupta period phallus worship was being foisted on the Śiva cult. And, in fact, the earliest representation of Liṅga that has been found in a Śaiva temple is at Guḍimallam in South India, and, on the grounds of plastic art, it cannot possibly be assigned to any date prior to the 4th century A.D. And even here, it is worthy of note, you do not see a mere Liṅga, but also a standing figure of Śiva attached to it in front2 showing clearly that even in this period the representation of Śiva was not entirely forgotten and was not completely supplanted by Liṅga.3 Another [S. 21] very early representation of phallus is that, supplied by the Liiiga stone found near the village of Karamḍāṇḍā and inscribed on the base.1 The epigraph is dated 117 G.E.=436 A.D.)., and speaks of the Liṅga as Bhagavān Mahādeva, showing a clear identification of phallus with Śiva in this instance. But it must have taken sometime longer for the phallus to completely supersede and supplant, all over India, the human form of Śiva as an object of worship. For Śiva in his human representation certainly occurs, as I have said above, on the coins of Śaśāṅka who flourished in the first half of the seventh century A.D.

1 JBBRAS., XVI, 208.

2 T. A. Gopinatha Rao's Elements of Hindu iconography. Vol. I., pt. I, p. 6.

3 There is a sculpture originally found at Bhīṭā but now lying in the Lucknow Museum. Dr. Führer, who discovered it, apparently took it to be the capital of a column. Mr. R. D. Banerji, however, says that Dr. Führer did not pay much attention to the inscription on it, from a careful study of which it appears that the sculpture represents a Liṅga and that the date of the Liṅga on palaeographic evidence is the first century B. C. (ASI.-AR., 1909-10, 147-8). Now, in the first place, the characters cannot with certainty be proved to be earlier than those of the time of the Kushana king. Vāsudeva (circa 200 A.D.). Secondly, Mr. Banerji no doubt reads l(iṃ)go in his transcript, but the word is clearly lago, whatever that may mean. The late Dr. Bloch also read it lago, as Mr. Banerji informs us in a footnote. Thirdly, even taking the word to be lingo with Mr. Banerji and further correcting it into liṅgaṃ, it cannot denote the "phallic symbol of Śiva." because in inscriptions such an image is termed Mahādeva, as was rightly maintained by Bloch. Fourthly, what is meant by saying that " the liṅga of the sons of Khajahūti was dedicated by Nāgasiri," as Mr. Banerji's translation has it? If the sons of Khajahūti had caused the idol to be made, the construction would have been liṅgaṃ kāritaṃ Khajahūti-putraiḥ pratishṭhāpitaṃ cha Vasishṭhīuputreṇa etc. Fifthly, Mr. Banerji's opinion that the sculpture represents a Liṅga is based merely on the inscription which, as we have seen, does not speak of any Liṅga at all. He does not tell us that the sculpture looks like a Liṅga. Dr. Führer, on the other hand, looks upon it as the capital of a column, as we have seen. It is exceedingly desirable that some archaeologist should examine this sculpture carefully and tell us whether it has the form of a Liṅga.

1 EI., X. 70 & ff.[S. 22] Connected with Śiva are the four gods, Skanda, Kumāra, Viśākha and Mahāsena. They are, however, regarded at present as only four different names of one and the same god, viz., Kārtikeya. The well-known two verses of the Amarakosha, which include these names, are taken as giving seventeen names of this deity. In ancient times, however, these four names denoted four different gods. Of course, the passage from Patañjali's Mahābhāshya, which I have just referred to and which speaks of an image of Śiva made for worship, speaks also of Skanda and Viśākha in that connection. This indicates that images not only of Śiva but also of Skanda and Viśākha were made in Patañjali's time for worship. Here both Skanda and Viśākha have been mentioned. Certainly, if these two names had denoted but a single deity, Patañjali would have mentioned only one, but as he has used two names, it is clear that Skanda and Viśākha must denote two different gods. But let us see what coins teach us on this point. Those of you who have studied the Kushana coinage need not be told that we have two types of Huvishka's coins which are of great interest to us in this connection. One type bears on the reverse three gods who have been named Skanda, Kumāra and Viśākha, and another, four gods named Skanda, Kumāra, Viśākha and Mahāsena.1 As [S. 23] all these names have each a figure corresponding to it, is it possible to doubt that Skanda, Kumāra, Viśākha and Mahāsena represent four different gods ? The coins thus convey to us an important piece of mythological knowledge, which we do not yet know from any other source. Huviskha, most of you are aware, flourished in the second half of the second century A. D., and the Amarakosha is now-a-days being assigned to the 4th century A. D.1 As the interval between the two is not very great, a doubt may naturally arise as to whether we are right in taking the two verses from the Amarakosha as giving us seventeen names of only one god, viz., Kārtikeya. The two verses in question consist of four lines, and strange to say, none of these lines mentions more than one of the four gods Skanda, Kumāra, Viśākha and Mahāsena. Thus the first line has Mahāsena, the second Skanda, the third Viśākha, and the fourth Kumāra only. Had we not rather take each line separately and say that it really intends setting forth the different names of each one of these four gods instead of saying as we have been doing up till now that all the four lines together give seventeen names of one and the same god?

1 CCPML., 207.

1 IA., 1912,216."[Quelle: Bhandarkar, D. R. (Devadatta Ramakrishna) <1875-1950>: Lectures on ancient Indian numismatics. -- Calcutta : University of Calcutta, 1921. -- xii, 229 S. ; 20 cm. -- S. 14 - 23. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/lecturesonancien00bhaniala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-17. -- "Not in copyright"]

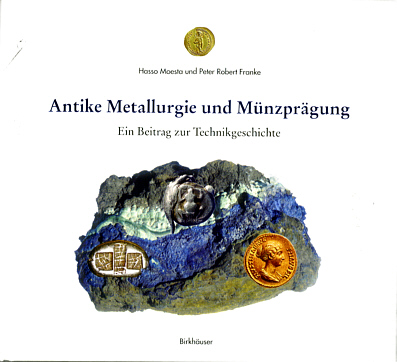

Münzen können bei Ausgrabungen oder bei anderen Funden Leitmünzen sein sein zur (relativen und absoluten) Datierung von Schichten oder zur sonstigen Einordnung (z.B. Dynastien, politische Gebilde). Man muss allerdings immer untersuchen, ob die Münzen ursprünglich zu der betreffenden Schicht bzw. in den betreffenden Zusammenhang gehörten, oder ab sie später hineingeraten sind, bzw. ob es sich überhaupt um eine einheitliche Schicht bzw. einen einheitlichen Zusammenhang handelt.

Folgende Zeichnung von Mortimer Wheeler zeigt deutlich die Trugschlüsse, denen man bei unprofessionellem Vorgehen erliegen kann:

Abb.: "Diagramme, die die Schichtung eines Siedlungshügels und das Versagen

einer Aufnahme nach mechanischen Höhenlinien zeigen."

[Bildquelle: Wheeler, Robert Eric Mortimer <1890 - 1976>: Moderne Archäologie : Methoden u. Technik d. Ausgrabung / Sir Mortimer Wheeler. -- Reinbek b. Hamburg : Rowohlt, 1960. -- 244 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- (rowohlts deutsche enzyklopädie ; 111/112). -- Originaltitel: Archaeology from the earth (1954). -- S. 62.]

Abb.: Metalldetektor

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia: Public domain]

Fundorte:

Art der Funde

Fundmenge

Abb.: Suche nach (modernen) Münzen, Karnataka: "One boy would go down under the

water and get a panful of sediment, and then the other would look through it for

discarded coins. They seemed to be finding quite a few."

[Bildquelle: Wm Jas. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/wmjas/2261869517/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-17. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Münzen aus Bodenfunden sind oft mit Verschmutzungen und Metallverbindungen und mit mineralischen Ablagerungen bedeckt (versintert) und korrodiert. Die Metallverbindungen und Ablagerungen bilden sich vor allem unter dem Einfluss der im Boden vorhandenen Säuren, Salze und Mineralien. Oft sind Kupfermünzen oder geringhaltige Silbermünzen zu großen Klumpen zusammengewachsen. All diese "Verschmutzungen" sollten nur von dafür ausgebildeten Restauratoren entfernt werden.

Die Grundgestalten der meisten indischen Münzen sind Scheiben in

Zur Gestaltung der beiden Seiten (der Rand scheint erst in neuerer Zeit gestaltet worden zu sein) siehe die Beispiele unten bei der Münzgeschichte.

Wertangaben sind oft nicht üblich und auch nicht notwendig, da der Wert durch Metall, Größe und Gewicht gegeben und klar zu erkennen war.

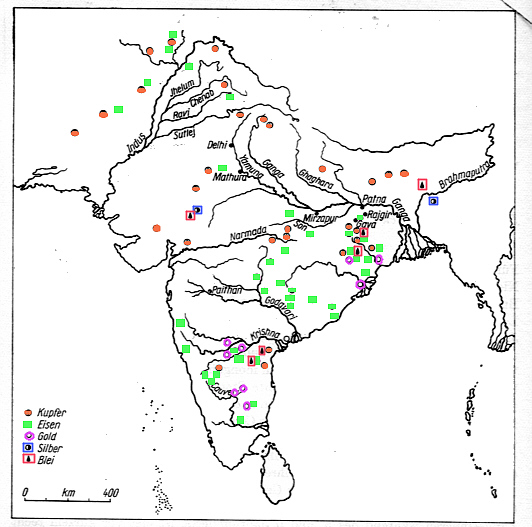

Abb.: Erzlager in Indien

[Bildvorlage: Kosambi, Damodar Dharmanand <1907 - 1966>: Das alte Indien : Seine Geschichte u. seine Kultur / D. D. Kosambi. Aus d. Engl. übers. u. in dt. Sprache hrsg. von Eva Ritschl u. Maria Schetelich. Mit einem Nachruf von Horst Krüger. -- Berlin : Akademie-Verl. , 1969. -- 277 S. : Ill ; 25 cm. -- Originaltitel The culture and civilisation of ancient India (1965). -- S. 116.]

"Der Mineralreichtum Indiens ist sehr bedeutend, aber erst neuerdings mehr ausgebeutet worden. Goldseifen bestehen seit undenklichen Zeiten an vielen Orten, liefern aber wenig Ertrag; dagegen haben die in Südindien im Wainad (am Westabhang der Nilgiri), in Kolar (Maisur) und in Birma bearbeiteten Goldquarzgänge eine stets wachsende Ausbeute ergeben. Insgesamt brachten die Goldminen an Wert 1902: 35,398,052 Mk.

Kupfer, in allen Zeiten stark ausgebeutet, wird jetzt nur noch in Radschputana und Tschutia Nagpur gewonnen,

Blei und Silber im westlichen Himalaja und in Radschputana;

Zinn in sehr reichen Lagern in Birma; Antimon-, Nickel- und Kobalterze in Radschputana, letztere auch in Nepal und Birma;

Manganerze (Ausfuhr 1904: 2,294,094 Rupien) in den Zentralprovinzen.

Sehr verbreitet sind Eisenerze, zuweilen von großem Reichtum und hoher Güte, so in Birma, Bengalen, den Nordwestprovinzen, Radschputana, Zentralindien, Pandschab, Zentralprovinzen, Madras, Maisur etc. Die Gewinnung des Eisens (1900: 63,000 Ton.) aus den Erzen ist vielfach noch sehr primitiv, doch liefert das staatliche Eisenwerk in Ranigandsch (Damodartal, Bengalen) allein etwa 57,000 Ton. jährlich."

[Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v. "Ostindien"]

Den Anteil von Legierungen an den Edelmetallen Gold bzw. Silber nennt man Feingehalt, das Gewicht des in der Münze enthaltenen Goldes bzw. Silbers Feingewicht. Das Gewicht der Münze als ganzer nennt man Rauhggewicht bzw. Münzgewicht.

Der Nennwert (Nominalwert = Wert einer Münze im Zahlungsverkehr) einer Münze setzt sich zusammen aus:

Abb.: Goldführendes Erz

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia, courtesy USGS, Public domain]

Abb.: Goldnuggets (gediegenes Gold)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Maria Schetelich fasst zusammen:

"In Indien verarbeitete man Gold bereits zur Zeit der Industal-Kultur (2600 bis 1800 v. Chr.) zu Schmuck, seltener auch zu Gebrauchsgegenständen wie Schalen, Haarnadeln usw. Vermutlich importierte man es zu jener Zeit aus Südindien (Gebiet Kollar). In späteren Jh. entwickelte sich die Gold-Schmiedekunst zu hoher Blüte. Gold-Schmuck wurde vorwiegend für den Bedarf der Oberschicht in den Städten und der höf. Kreise sowie für den Fernhandel bis in die Mittelmeerländer hergestellt. Als einer der gebräuchlichen Wertmesser diente Gold etwa seit dem 10.—8. Jh. v. Chr. zunächst in Form von Schmuck (Halsringe, Sanskrit Nischka), dann wohl als Barren von festgelegtem Gewicht. Gold-Münzen prägten zuerst die Kuschan (ca. 2.-3. Jh. n. Chr.), als durch den Fernhandel mit Rom und eine feste Seehandelsverbindung mit Hinterindien (Sanskrit Suvarnabhumi, 'Goldland') Gold in überreicher Menge nach Indien kam. Jedoch spielte Gold als Währung für den Binnenhandel keine bedeutende Rolle. " [Quelle: Maria Schetelich. -- In: Erklärendes Wörterbuch zur Kultur und Kunst des Alten Orients : Ägypten, Vorderasien, Indien, Ostasien / Helmut Freydank ... [Zeichn.: Hans-Ulrich Herold]. -- Hanau : Dausien, [1985]. -- 494 S. : Ill. ; 22 cm. -- Lizenzausgabe des im Verlag Koehler u. Amelang erschienenen Titels: Der Alte Orient in Stichworten. -- ISBN 3-7684-1554-6. -- S. 158.]

Gold wird gewonnen

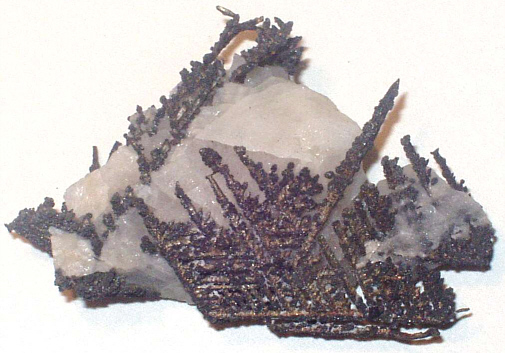

Abb.: Silbererz

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia, courtesy USGS, Public domain]

Abb.: Silber in Quarzmatrix, ca. 5 x 3 cm.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Reines Silber ist sehr weich und hat darum beachtliche Umlaufverluste. Besser für Münzen geeignet sind durch Kupfer gehärtete Legierungen.

Als Billon bezeichnet man Kupfer-Silber-Legierungen mit einem Feingehalt Silber unter 50%.

Potin nennt man minderwertige Legierungen aus Kupfer, Zinn, Blei und Silber sowie Spuren anderer Metalle. Die Legierungsverhältnisse sind sehr unterschiedlich.

Abb.: Drachme aus Billon des Huna Napki Malka (ca.

475-576).

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Obv: Napki Malka type bust with winged headdress. Pahlavi

legend "NAPKI MALKA".

Rev: Zoroastrian fire altar with attendants either side. Sun wheel, or

eight-spoked Buddhist Dharmacakra above left.

Actual size: 27 mm, 3.3 g. Findplace: Afghanistan/ Gandhara.

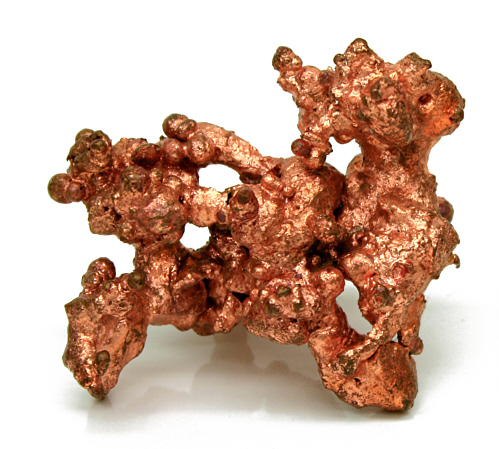

Kupfer ist neben Gold und Silber das wichtigste Münzmetall. Kupfer ist doppelt so hart wie Silber und dreifach so hart wie Gold. Man verwendete es darum für Legierungen, vor allem von Silber, um die Münzen abriebfester zu machen und damit die Umlaufverluste zu verringern. Kupfer ist allerdings anfällig gegen Säuren (-> Grünspan) und Schwefelverbindungen (-> Altersdunklung), es bildet auch Patina.

Kupferlegierungen, Plattierungen von Kupfer mit Silber und ähnliche Machenschaften und können dazu dienen, den Feingehalt der Münzen zu verringern -- sei's in privater Betrugsabsicht, sei's staatlicherseits, um das Geld zu "vermehren".

Kupfer ist vor allem gut geeignet für Münzen in kleinen Werten (Kleinmünzen = Scheidemünzen).

Abb.: gediegenes Kupfer, ca. 4 cm.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Kupferstufe, ca. 4 x 2 cm

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Bronzen sind Legierungen aus Kupfer, die meist Zinn, aber manchmal auch andere Metalle enthalten. (Eine Kupfer-Zink-Legierung wird aber Messing genannt.)

Bronze wird für den Guss von Münzen verwendet aber auch für Prägungen. Zum Prägen besonders geeignet ist Bronze mit einem Zinnanteil von 10 bis 15%, der teilweise durch Blei oder Zink ersetzt werden kann. Manches, was als Kupfermünze bezeichnet wird, ist in Wirklichkeit eine Bronzemünze.

In numismatischen Werken und Katalogen wird Bronze oft mit Æ (für lateinisch aes) abgekürzt.

Zum schwierigen Gebiet der Gewichtsmasse sowie Legierungsverhältnisse der Münzen muss ich mich hier der Bemerkung von John Allan, anschließen von 1907 bis 1947 Keeper of the Depatment of Coins and Medals des British Museum war:

"§ 197. Very little is known concerning the denominations and standards of ancient India. The information given in the law-books and similar literary sources is of little practical value when applied to the coins that have survived, and for the period covered by this volume we get no help from inscriptions. We need not here go again into the problem, fully discussed by Rapson, of reconciling the simplicity of the theoretical system given in the law-books with the great diversity in weights found in the coins themselves. Nor shall we go over the ground already covered by Cunningham in his discussion of the weights of the earliest Indian coins. We shall be content to point out that the ratio 16 annas = 1 rupee goes back at least 2,000 years to the 16 māṣakas = 1 kārṣāpaṇa of the law-books." [Quelle: Allan, John <1884-1955>: Catalogue of the coins of ancient India. -- London, Printed by order of the Trustees, 1936. -- lxvii, 318 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- S. clix.]

Die Punze ist ein Schlagstempel zur Metallbearbeitung. Eine Punzierung oder kurz Punze ist eine Prägung, bei der das Motiv mit dem Prägestock in das Metall als Negativ, also versenkt, zu sehen ist.

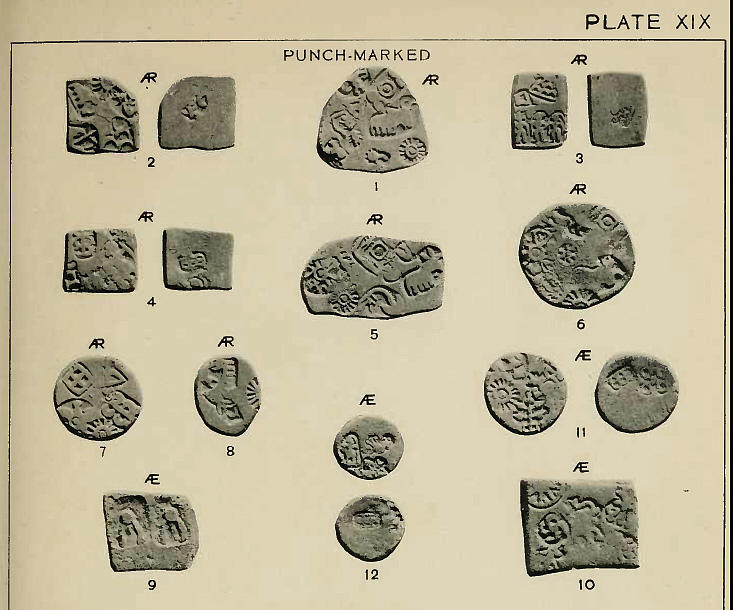

Abb.: Gepunzte (punch-marked) Münze der Maurya

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Abb.: Gepunzte (punch-marked) Münzen

[Bildquelle: Smith, Vincent Arthur, 1848-1920: Catalogue of the coins in the Indian Museum. -- Oxford : Clarendon Pr. -- Vol I, Part II: Ancient coins of Indian types. -- 1906. -- Pl. XIX. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/pt2catalogueofco01indiuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15]

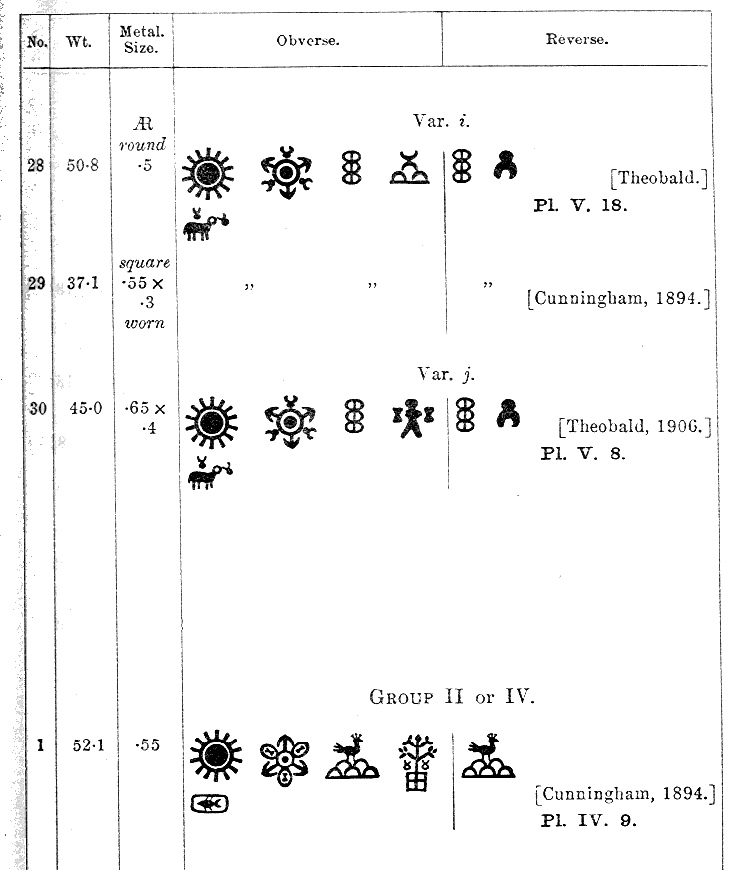

Abb.: Beispiel für Punzmarken auf Silbermünzen

[Bildquelle: Allan, John <1884-1955>: Catalogue of the coins of ancient India. -- London, Printed by order of the Trustees, 1936. -- lxvii, 318 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- S. 31

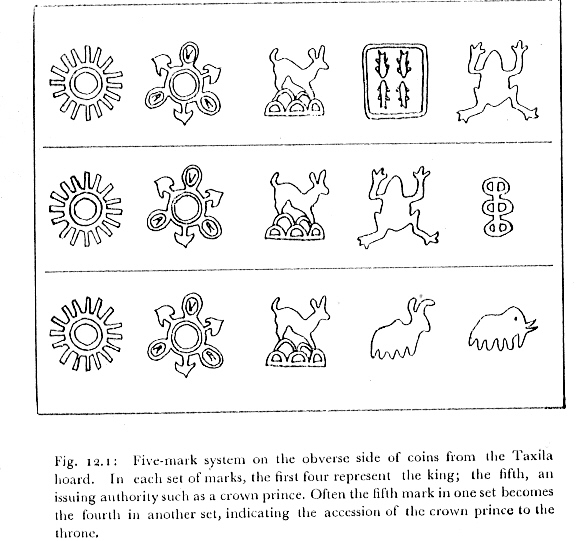

Gepunzte Münzen haben in der Regel fünf Punzmarkierungen auf der Vorderseite und eine nicht einheitliche Anzahl von solchen Markierungen auf der Rückseite. Die Bedeutung der Punzmarkierungen, die wohl gleichzeitig angebracht wurden, ist umstritten. D. D. Kosambi entwickelte die Hypothese, dass bei den fünf Markierungen der Vorderseite die ersten vier den König bezeichnen, die fünfte die herausgebende Autorität (den Kronprinzen):

Abb.: Kosambis Deutung der Punzmarkierungen

[Quelle der Abb.: Kosambi, D. D. (Damodar Dharmanand) <1907-1966>: Scientific numismatics. -- In: Scientific American. -- Febr. 1966. -- S. 102 - 11. -- Abgedruckt in: Kosambi, D. D. (Damodar Dharmanand) <1907-1966>: Indian numismatics. -- New Delhi : Orient Longman, 1981. -- x, 159 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN 0861310187. -- S. 146. -- Man konsultiere in der Aufsatzsammlung Kosambis ausführliche Abhandlungen zu punchmarked coins.]

Zu den Deutungen der Punzmarkierungen kann ich keine Stellung nehmen. Mir als Laien erscheint aber noch sehr vieles im Dunkeln zu sein.

Sehr anschaulich wird das Prinzip in folgendem Zitat geschildert:

"Wir haben die Tatsache vor uns, dass es vor dem 7. Jahrhundert keine Münzen auf der Welt gab und dass diese Neuerung vergleichsweise schlagartig die Welt eroberte und veränderte. Technisch scheint auf den ersten Blick der Fortschritt vom markierten Barrengeld zur geprägten Münze nicht so erheblich wie der Übergang vom Pferdewagen zum Motorfahrzeug, und doch waren die Auswirkungen ähnlich bedeutsam. Münzen kann man gießen oder prägen. Dem Laien erscheint das Gussverfahren einfacher, in der Praxis hat sich aber das Prägeverfahren bis auf China überall durchgesetzt.

Zunächst wird das Münzmetall geschmolzen und in kleine runde Scheiben gegossen, die den gleichen Durchmesser, die gleiche Dicke und das gleiche Gewicht haben. Dann wird dieses Metallplättchen, »Schrötling« genannt, auf einen Amboss gelegt, in den (aus gehärtetem Metall) der Vorderseiten- oder Aversstempel eingelassen ist. Jetzt nimmt man den Oberstempel (siehe Abbildung Seite 45), an dessen Unterseite der Stempel für das Revers, das ist die Rückseite der Münze, angebracht ist und prägt mit einem oder mehreren Hammerschlägen die Münzen aus vergleichsweise weichem Metall (Gold, Silber, Kupfer). Der Schrötling konnte entweder warm, d. h. noch erhitzt zur Prägung kommen oder kalt verformt werden. Die Stempel bestanden für gewöhnlich aus einer speziell gehärteten Bronze mit hohem Zinngehalt oder aus einem fast stahlartigen Eisen. Der Oberstempel wurde wie ein Meißel frei in der Hand gehalten. Mit dieser scheinbar so simplen Technik konnten von einem Stempel mindestens 10000 Münzen geprägt wurden - wahrscheinlich dürfte das Maximum erheblich höher gewesen sein - ohne Schaden oder Abnutzungsspuren am Stempel zu verursachen. Die erste Massenproduktion hatte das Licht der Welt erblickt."

[Quelle von Text und Abb.: Geld / [Dt. Bank AG Frankfurt am Main. Hrsg. von Hans Joachim Funck. Mit Beitr. u. fachl. Beratung von Siegfried Otto u. Ludwig Devrient]. -- Frankfurt am Main : Dt. Bank, 1982. -- 368 S. : Ill. ; 18 cm. -- (Edition Deutsche Bank). -- ISBN 3-87045-213-7. -- S. 44f.]

Abb.: Was man zum einfachen Bronzeguss braucht

[Bildquelle: hans s. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/archeon/10682908/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-18. --

![]()

![]() Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Bronzeguss unter einfachen Bedingungen

[Bildquelle: hans s. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/archeon/52688570/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-18. --

![]()

![]() Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Bronze-Münze, ½ Kārṣāpaṇa, Śuṅga, 2./1. Jhdt v. Chr.

Ostindien

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Das Gussverfahren ist bedeutend aufwendiger und teurer als Prägung oder Punzierung. Folgende Bemerkungen vonMoesta und Franke in Bezug auf Antike Münzen gelten sicher analog auch für indische Verhältnisse:

"Sind uns auch keine Berichte über die genauen Auflagenzahlen einzelner Prägungen der frühen Zeit überliefert, können wir trotzdem eine rohe Vorstellung von solchen Zahlen aus einfachen Überlegungen erhalten: Damit eine Münze dem Handel dienen kann, müssen an zahlreichen Orten zahlreiche Münzen vorhanden sein. Weniger als einige tausend Exemplare können eine Funktion als Geld nicht entfalten. Die Herstellung einiger tausend Münzen ist also sicher die untere Grenze der Auflagenhöhe für die Hinführung eines Geldes. Andererseits schraubt die Aufgabe, z.B. ein Söldnerheer einige Monate zu entlohnen, die Stückzahl der zu prägenden Münzen in die Hunderttausende oder gar vielen Millionen. Bei solch großen Auflagen ist das Prägeverfahren sicher am geeignetsten. Dabei ist die teure und schwer erhältliche qualifizierte Arbeit das Schneiden der Stempel. Da von einem Stempel sehr viele Abschläge gemacht werden, ist der gesamte Aufwand bei hohen Stückzahlen vergleichsweise gering, da die Arbeit der Schlägergruppe an Ofen und Amboß zwar Geschick, aber kaum eine besondere Begabung (und damit etwa erhöhte Kosten) erfordert.

Schon nur einige tausend Metallstücke mit einem klar erkenn- und haltbaren Zeichen bei gleichzeitig engen Gewichtstoleranzen zu versehen, bringt beim Gießverfahren einen sehr großen Aufwand bei der Formherstellung mit sich. Jede einzelne Münze braucht eine eigene, nur einmal zu verwendende Form. Ein Formmaterial, welches einer mehrfachen Verwendung bei den hohen Gießtemperaturen der Edelmetalle standgehalten hätte, gab es damals nicht. Trotzdem kennen wir auch in der Antike Serien gegossener Münzen. Das Verfahren ist zweifellos teuer, gestattet aber vielleicht den Verzicht auf besonders qualifizierte Arbeitskräfte."

[Quelle: Moesta, Hasso <1925 - > ; Franke, Peter Robert <1926 - >: Antike Metallurgie und Münzprägung : ein Beitrag zur Technikgeschichte. -- Basel [u.a.] : Birkhäuser, 1995. -- 184 S. : Ill.. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 3-7643-5166-7. -- S. 78.]

Man muss beachten, dass das Datum, das (in späterer Zeit) auf den Münzen angegeben wird, nicht unbedingt das Jahr der Prägung oder Ausgabe ist. Man prägte auch nach alten Vorlagen oder mit alten Stempeln, manchmal auch mit dann schlechterem Material (staatlicher Betrug).

Zu den Zeitrechnungen siehe:

Fleet, J. F. (John Faithful) <1847-1917>: Hindu Chronology (1910). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 3. Inschriften, 5.). -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen035.htm

Siehe die ausgezeichnete Gesamtdarstellung:

Brown, C. J.: The coins of India (1922). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 4. Münzen, 1.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-14. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen041.htm

Im Folgenden ergänze ich die Darstellung Browns durch zusätzliche Abbildungen. Die Abbildungen entsprechen nicht der Wichtigkeit der betreffenden Münzen, sondern dem urheberrechtlich frei zur Verfügung stehenden Material.

Auf die verschiedenen Möglichkeiten, indische Münzen zu klassifizieren, kann hier nicht eingegangen werden.

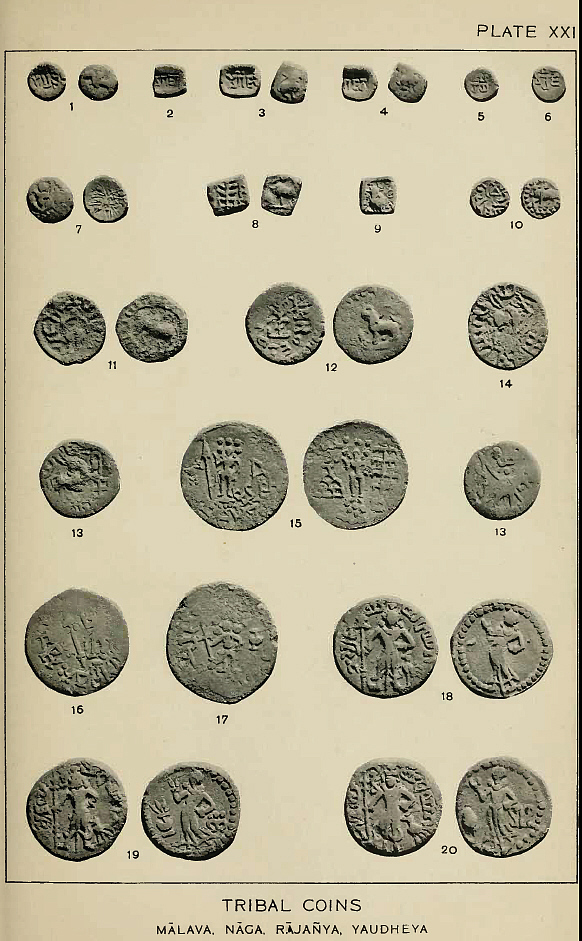

Abb.: Münzen der Mālava, Nāga. Rājañya, Yaudheya

[Bildquelle: Smith, Vincent Arthur, 1848-1920: Catalogue of the coins in the Indian Museum. -- Oxford : Clarendon Pr. -- Vol I, Part II: Ancient coins of Indian types. -- 1906. -- Pl. XXI. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/pt2catalogueofco01indiuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15]

Abb.: Silbermünze, Kuninda, ca. 1. Jhdt v. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

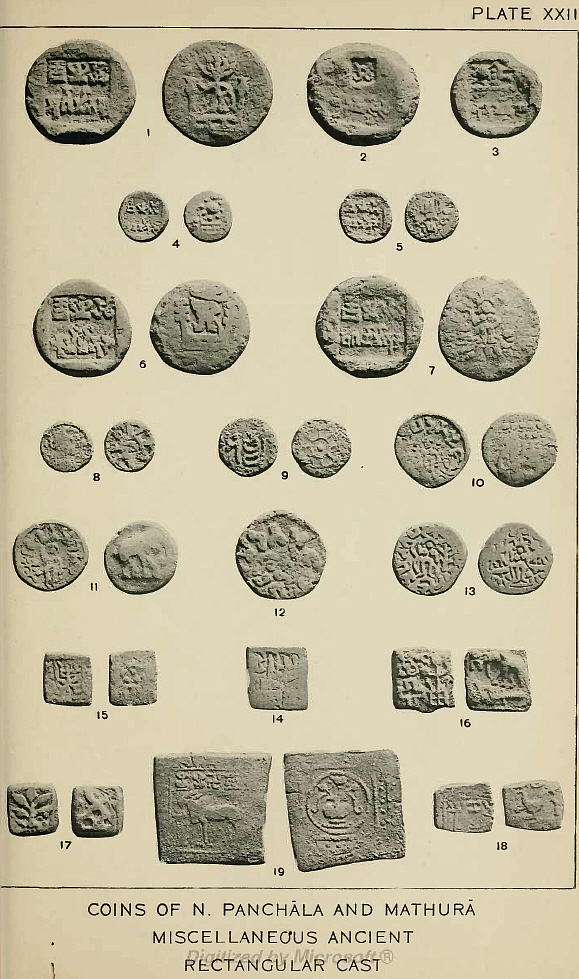

Abb.: Münzen aus Pañcāla und Mathurā, verschiedene quadratische Münzen

[Bildquelle: Smith, Vincent Arthur, 1848-1920: Catalogue of the coins in the Indian Museum. -- Oxford : Clarendon Pr. -- Vol I, Part II: Ancient coins of Indian types. -- 1906. -- Pl. XXII. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/pt2catalogueofco01indiuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15]

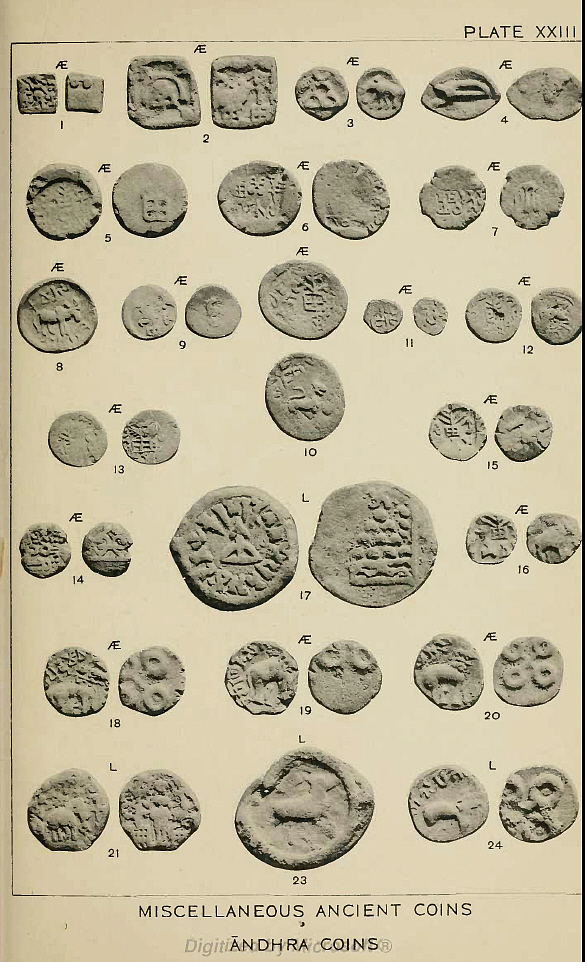

Abb.: Münzen der Āndhra, sonstige Münzen

[Bildquelle: Smith, Vincent Arthur, 1848-1920: Catalogue of the coins in the Indian Museum. -- Oxford : Clarendon Pr. -- Vol I, Part II: Ancient coins of Indian types. -- 1906. -- Pl. XXIII. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/pt2catalogueofco01indiuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15]

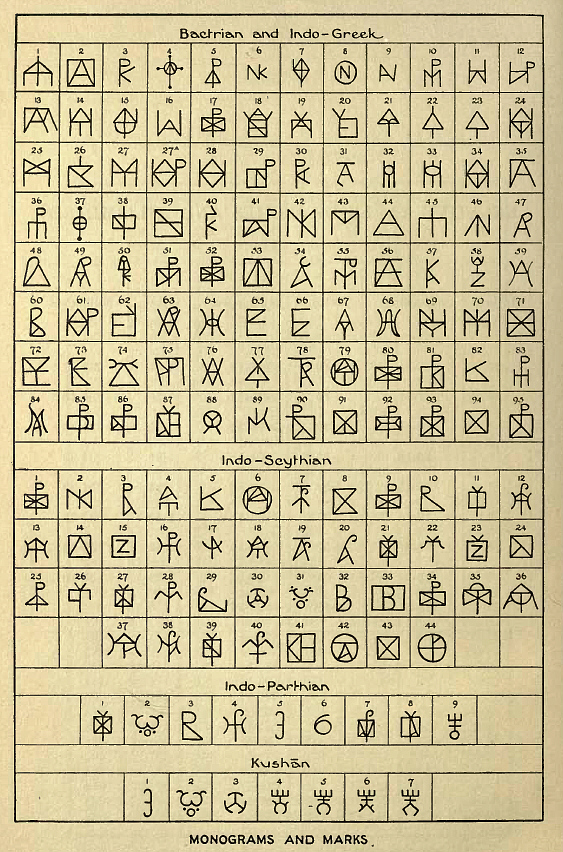

Abb.: Monograms and marks

[Bildquelle: Whitehead, R. B. (Richard Bertram): Catalogue of coins in the Panjab museum, Lahore. -- Oxford : Published for the Panjab government by the Clarendon Press. -- Vol. 1. Indo-Greek coins. -- 1914. -- 218 S. : 20 Pl. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins01lahoiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-11. -- "Not in copyright". -- S. 218]

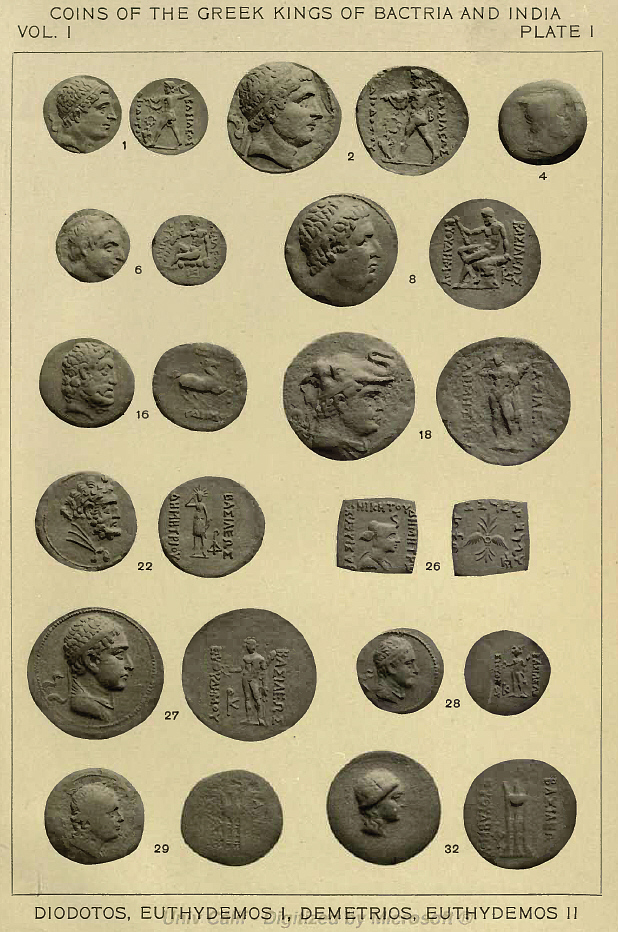

[Bildquelle: Whitehead, R. B. (Richard Bertram): Catalogue of coins in the Panjab museum, Lahore. -- Oxford : Published for the Panjab government by the Clarendon Press. -- Vol. 1. Indo-Greek coins. -- 1914. -- 218 S. : 20 Pl. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins01lahoiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-11. -- "Not in copyright". -- Pl. I.]

Abb.: Münze von Agathokles, Baktrien, ca. 200 bis 145 v. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Griechische Inschrift: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ

Abb.: Silber Tetradrachme von Eukratides

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Griechische Inschrift: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΕΥΚΡΑΤΙΔΟΥ

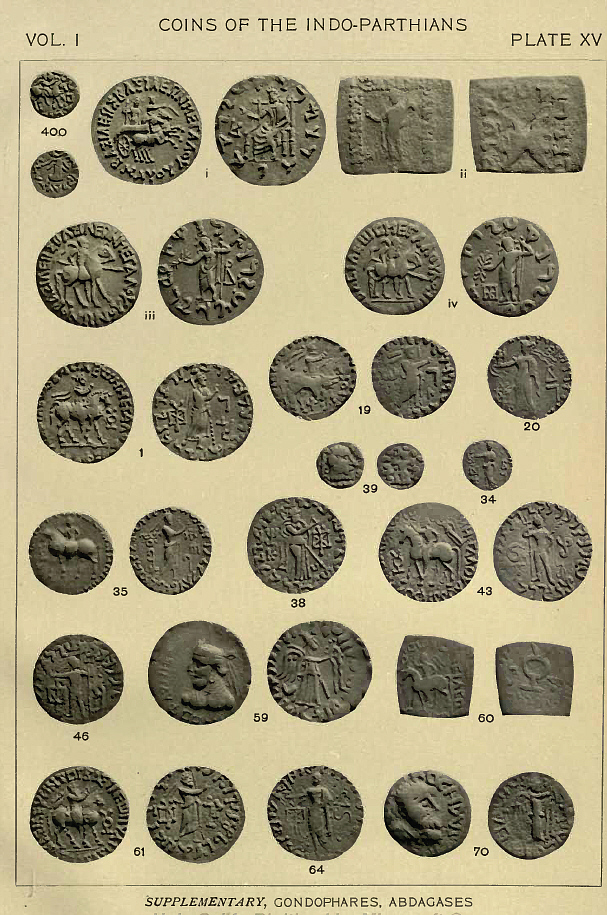

[Bildquelle: Whitehead, R. B. (Richard Bertram): Catalogue of coins in the Panjab museum, Lahore. -- Oxford : Published for the Panjab government by the Clarendon Press. -- Vol. 1. Indo-Greek coins. -- 1914. -- 218 S. : 20 Pl. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins01lahoiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-11. -- "Not in copyright". --Pl. XV.]

Abb.: Zwei Münzen des indo-parthischen Königs Abdagases, 1. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

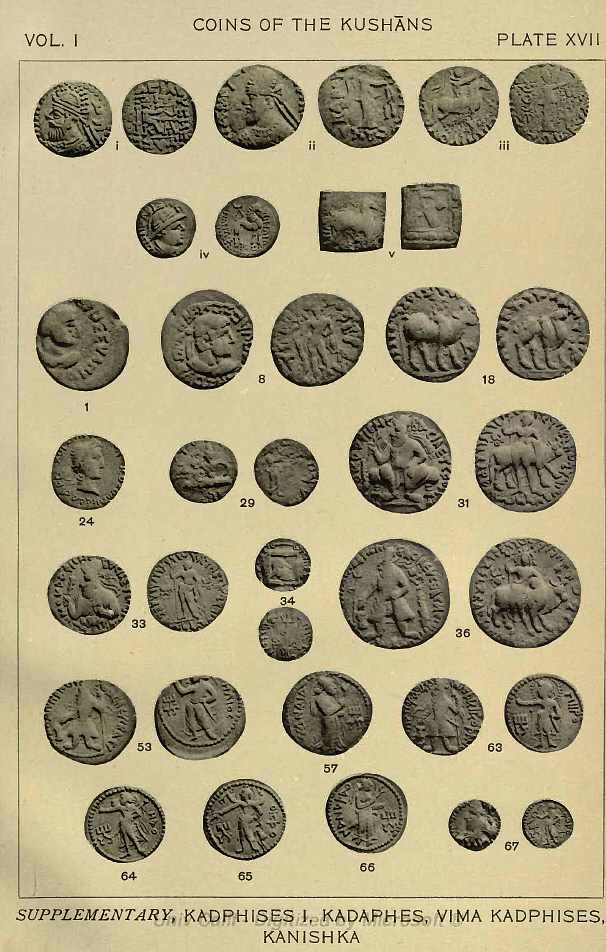

[Bildquelle: Whitehead, R. B. (Richard Bertram): Catalogue of coins in the Panjab museum, Lahore. -- Oxford : Published for the Panjab government by the Clarendon Press. -- Vol. 1. Indo-Greek coins. -- 1914. -- 218 S. : 20 Pl. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins01lahoiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-11. -- "Not in copyright". -- Pl. XVII.]

Abb.: Münze des Kuṣāṇa-Herrschers Śaka I (325 - 345 n. Chr.)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Abb.: Didrachme (1.70 g.) von Pāratarāja Bhimajhunasa, 1. Jhdt v. Chr. - 1. Jhdt

n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Brāhmī-Inschrift: Yolatanamputrasa Parataraja Bhimajhunasa ("Of the Parataraja Bhimajhuna, son of Yolatanam").

Abb.: Münze des Śaka Bhratadaman (278 - 295 n. Chr.).

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Silbermünze des Indo-Sassaniden Ardashir I (mit Feueraltar verso) (British

Museum London)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Münze von Hormizd I, Afghanistan

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Münze von Varhran I (4. Jhdt n. Chr.).

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Karṣāpāṇa, Blei (14,3 g), 27 mm, von Mulananda (ca. 125-345 n.Chr.)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Abb.: Zwei Münzen von Candragupta II. (375 - 413/15 n. Chr.)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Abb.: Münze der Yaudheyas mit Darstellung des

Kārttikeya

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Abb.: Münze der Yaudheyas mit Darstellung des

Kārttikeya

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Münze des Hūna Napki Malka (ca. 475-576)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Münze des Hūna Lakhana of Udyana

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Inschrift: RAJA LAKHANA (UDAYA) DITYA

Abb.: Münze der Pratihara mit Darstellung Viṣṇus als Varāha-Avatāra, 850-900 n.

Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Münze von Ali Adil Shah II, 1660 n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

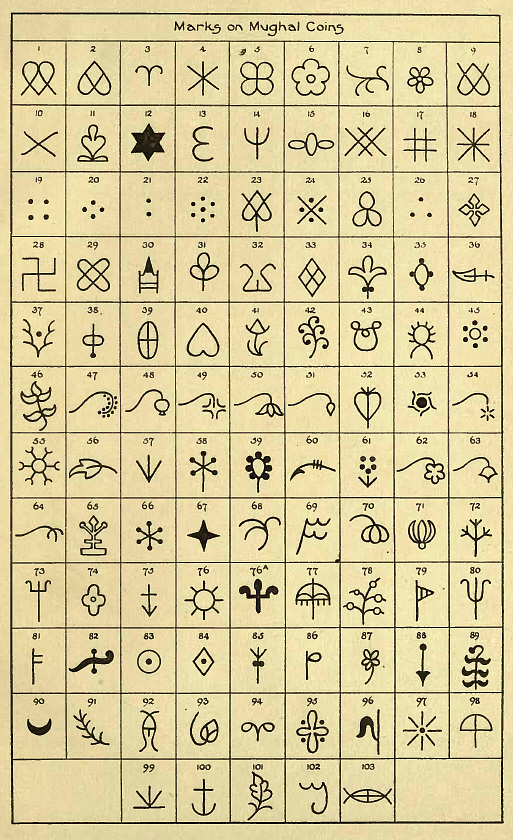

Abb.: Marks on Moghul coins

[Bildquelle: Whitehead, R. B. (Richard Bertram): Catalogue of coins in the Panjab museum, Lahore. -- Oxford : Published for the Panjab government by the Clarendon Press. -- Vol. 1. Coins of the Mughal emperors. -- 1914. -- CXV, 441 S. : 21 Pl. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins02lahouoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15. -- "Not in copyright". -- S. 441.]

Abb.: Glossary of the words an phrases used on the coins[Bildquelle: Whitehead, R. B. (Richard Bertram): Catalogue of coins in the Panjab museum, Lahore. -- Oxford : Published for the Panjab government by the Clarendon Press. -- Vol. 1. Coins of the Mughal emperors. -- 1914. -- CXV, 441 S. : 21 Pl. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins02lahouoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15. -- "Not in copyright". -- S. 436f.]

Abb.: Münze von Akbar (1562 - 1605), Gobindpur-Münzstätte

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

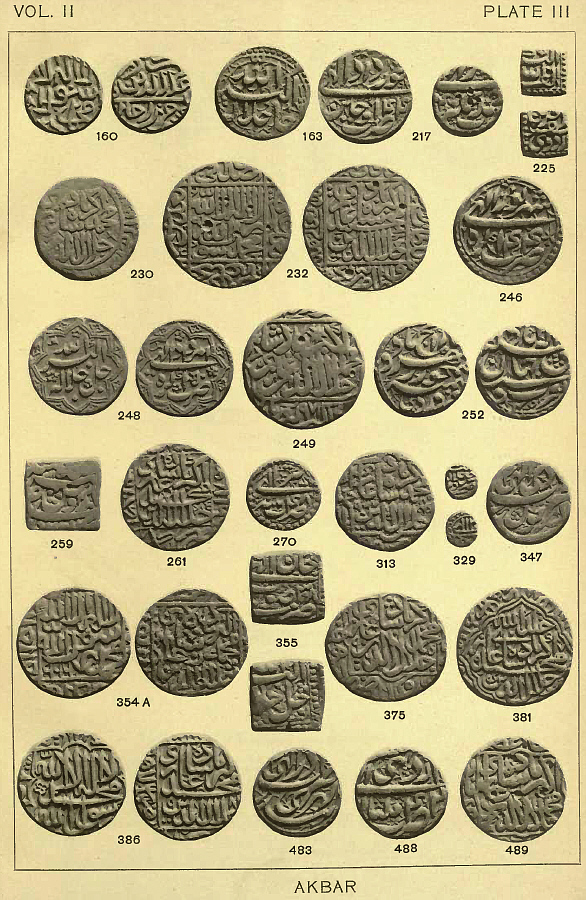

Abb.: Münzen von Akbar

[Bildquelle: Whitehead, R. B. (Richard Bertram): Catalogue of coins in the Panjab museum, Lahore. -- Oxford : Published for the Panjab government by the Clarendon Press. -- Vol. 1. Coins of the Mughal emperors. -- 1914. -- CXV, 441 S. : 21 Pl. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins02lahouoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15. -- "Not in copyright". -- Pl. III.]

Eine wichtige Münzstätte unter Akbar und seinem Sohn Jahangir (1569 - 1627) (نور الدین جهانگیر) war Agra (आगरा, آگرا).

Abb.: Silber-Rupie von Alamgir II (1699 - 1759), geprägt in der Münzstätte der

British East India Compagny, Madras, 1817 - 1835 (eingefrorenes Datum: 1172 AH =

1758/59 n. Chr.)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Abb.: 20 Bazarucos, Diu, 1799, Vorderseite

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: 20 Bazarucos, Diu, 1799, Rückseite

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

In Goa (गोंय; गोवा) wurden schon zur Regierungszeit von Manoel I von Portugal (regierte 1495 - 1521) Münzen geprägt; es waren die ersten Überseemünzen eines europäischen Staates.

Abb.: One Quarter Anna, East India Company, 1835

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

1 Anna = 1/16 Rupie = 4 Pysa = 12 Pie.

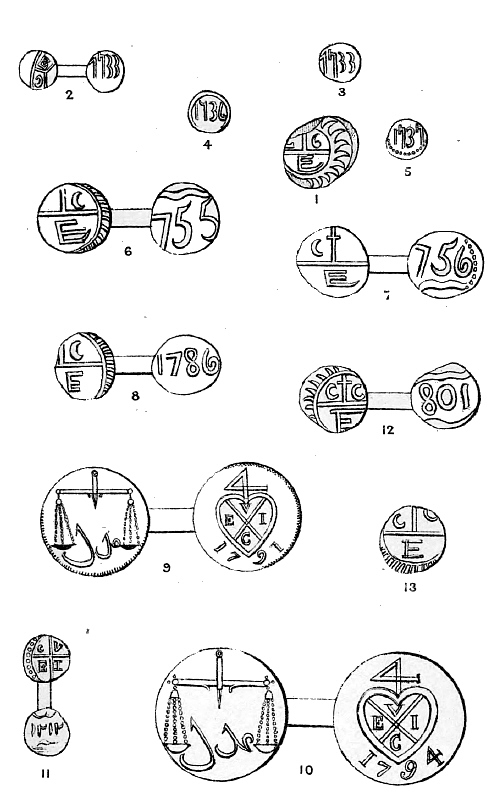

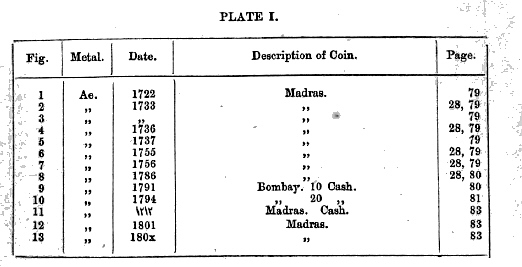

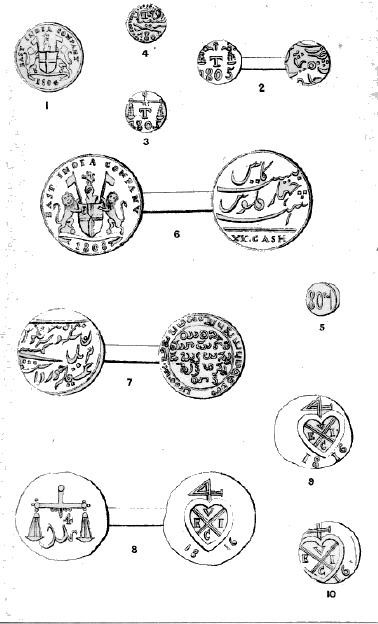

Abb.: Münzen der East India Company, 1722 - 1801

[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855-1935>: History of the coinage of the territories of the East India company in the Indian peninsula: and catalogue of the coins in the Madras museum. -- Madras : Government press, 1890. 123 S. : XX Pl. ; 25 cm. -- Pl. I. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/coinsindiamad00goveuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15]

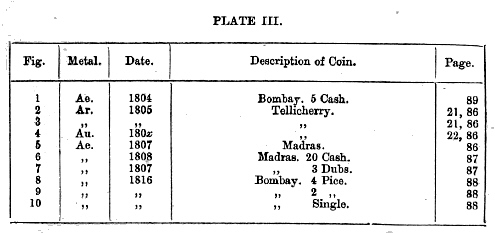

Abb.: Münzen der East India Company, 1804 - 1816

[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855-1935>: History of the coinage of the territories of the East India company in the Indian peninsula: and catalogue of the coins in the Madras museum. -- Madras : Government press, 1890. 123 S. : XX Pl. ; 25 cm. -- Pl. III. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/coinsindiamad00goveuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-15]

Münzstätten der East India Company waren

ab 1671: Bombay (heute: Mumbai - मुंबई); ab 1858 arbeitete siese Münzstätte für die englische Krone, seit der Unabhängigkeit arbeitet sie für die Indische Republik

ab Ende 17. Jhdt.: Madras (heute Chennai (சென்னை)

Abb.: Titelblatt

Agrawal, Bhanu ; Rai, Subas: Indian punch-marked coins. -- Delhi : Kanishka , 1994. -- 178 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN 81-85475-86-5. -- [Über einen Depotfund von 221 Münzen in Taxila]

Abb.: Titelblatt

Allan, John <1884-1955>: Catalogue of the coins of ancient India. -- London, Printed by order of the Trustees, 1936. -- lxvii, 318 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- ["This volume of the Catalogue of Indian coins in the British Museum, the seventh of the series, deals with the coins issued by native rulers from the earliest times to about A. D. 300."--Pref. The coins here described are largely from the collection of Sir Alexander Cunningham. cf. Introd., p. [xiii].]

Abb.: Titelblatt

Brown, C. J.: The coins of India. -- Calcutta : Association Press ; London [etc.] : Oxford University Press, 1922. -- 120 S. XII Pl. ; 19 cm. -- (The heritage of India series). -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/coinsofindia00browuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-11. -- "Not in copyright"

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Howgego, Christopher: Geld in der antiken Welt : was Münzen über Geschichte verraten. -- Darmstadt : Wiss. Buchges., 2000 .-- X, 223 S. : Ill. ; 22 cm. -- Originaltitel: Ancient history from coins (1995). -- [Zeigt anhand der griechischen und römischen Münzen, wie Numismatik und Historie sich gegenseitig bereichern können.]

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Jain, Rekha: Ancient Indian coinage : a systematic study of money economy from janapada period to early medieval period (600 BC to AD 1200). -- New Delhi : D.K. Printworld, 1995. -- XII, 247 S. : ill. ; 22 cm. -- ISBN 81-246-0052-X

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Kosambi, D. D. (Damodar Dharmanand) <1907-1966>: Indian numismatics. -- New Delhi : Orient Longman, 1981. -- x, 159 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN 0861310187. -- Sammlung von Aufsätzen des Pioniers der wissenschaftlichen Numismatik in Indien.

Abb.: Titelleiste

Rapson, E. J. (Edward James) <1861-1937>: Sources of Indian history : coins. -- Straßburg : Trübner, 1897. -- 55 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- (Grundriss der Indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 2,3b). -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/sourcesofindianh00rapsuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-14. -- [War damals das Standardwerk.]

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Sarma, I.K. (Inguva Karthikeya) <1937 - >: Numismatic researches : critical studies from excavated context. -- Delhi : Book India, 2000. -- XIII, 203 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN 81-85638-13-6

Journal of the Numismatic Society of India / Hindu University. -- Varanasi : Soc. -- 1.1939 ff.

Von den vielen Museen in Indien sei nur genannt das

Indian Museum, Kolkata (কলকাতা) (gegründet 1814)

In Europa führend ist das

Department of Coins and Medals des British Museum, London (wichtig auch die Catalogues of the Indian coins in the British Museum)

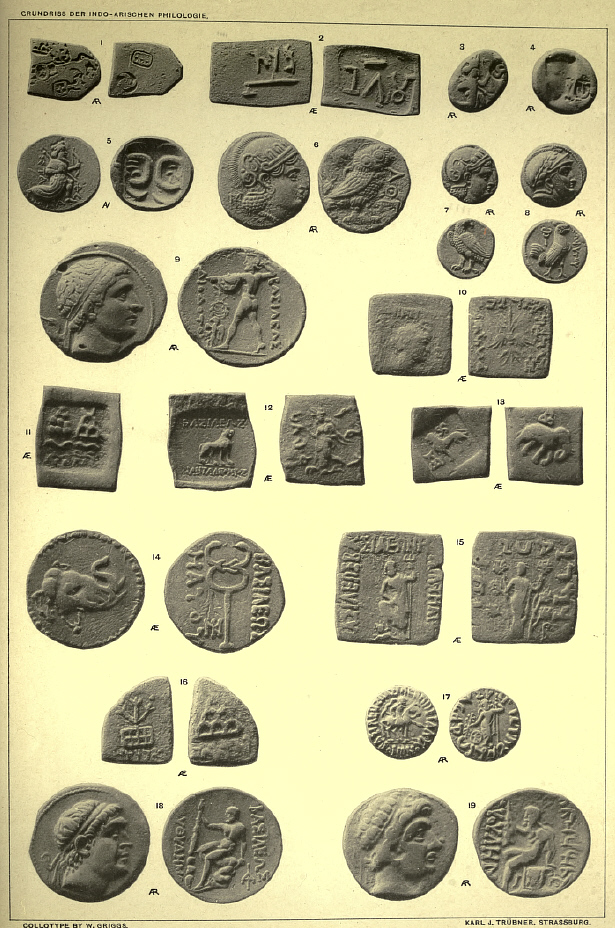

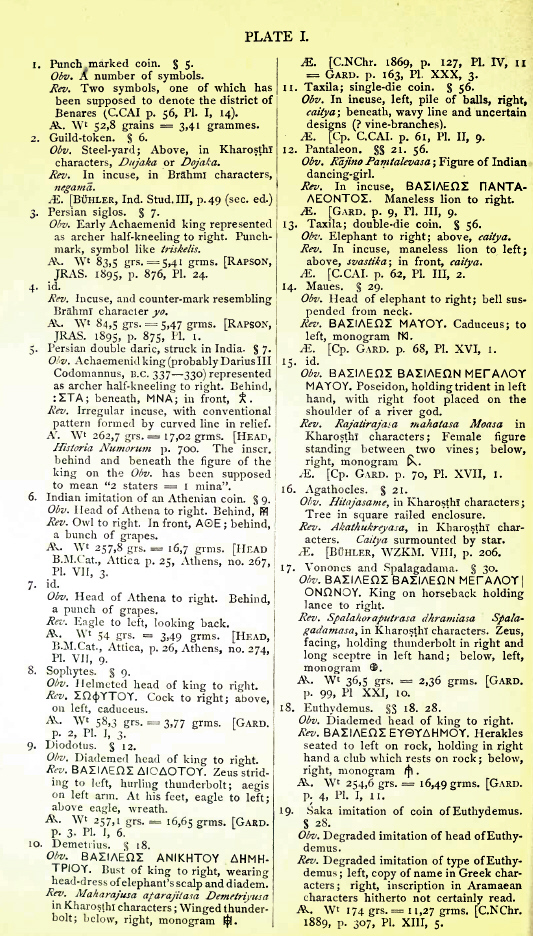

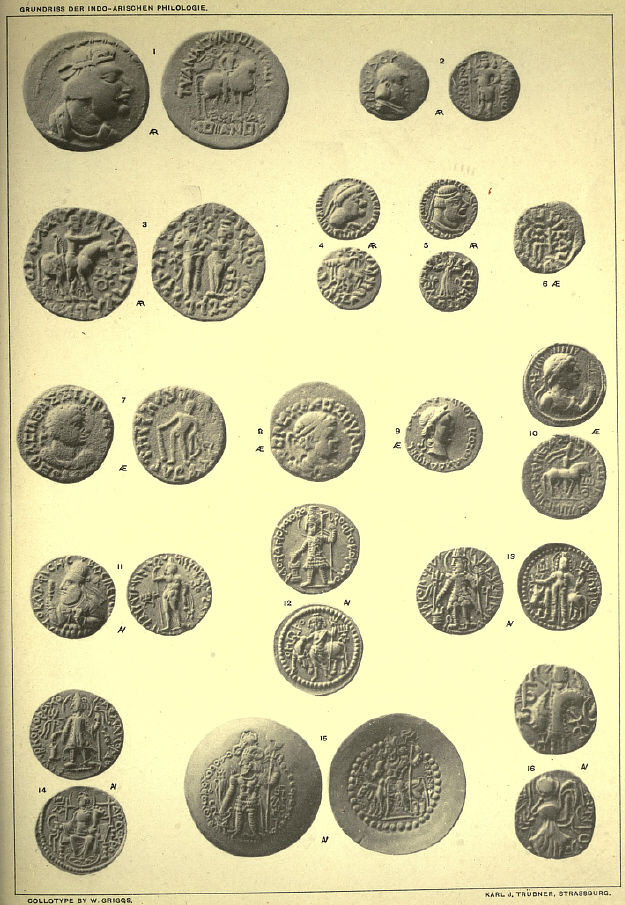

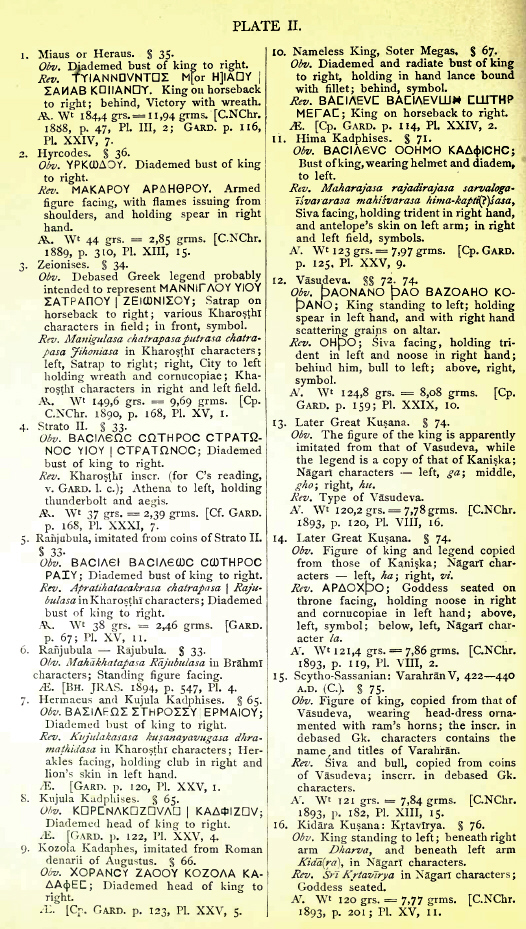

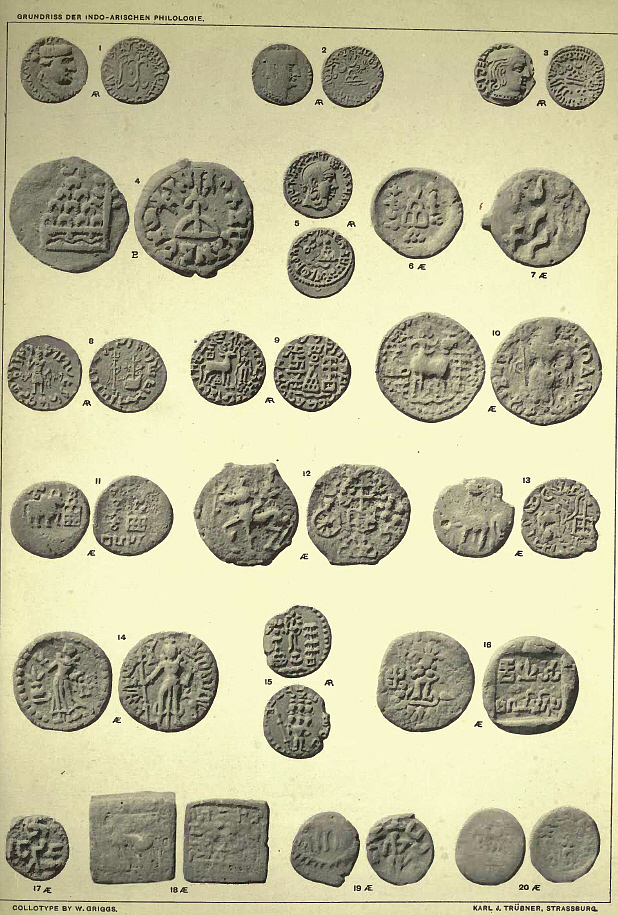

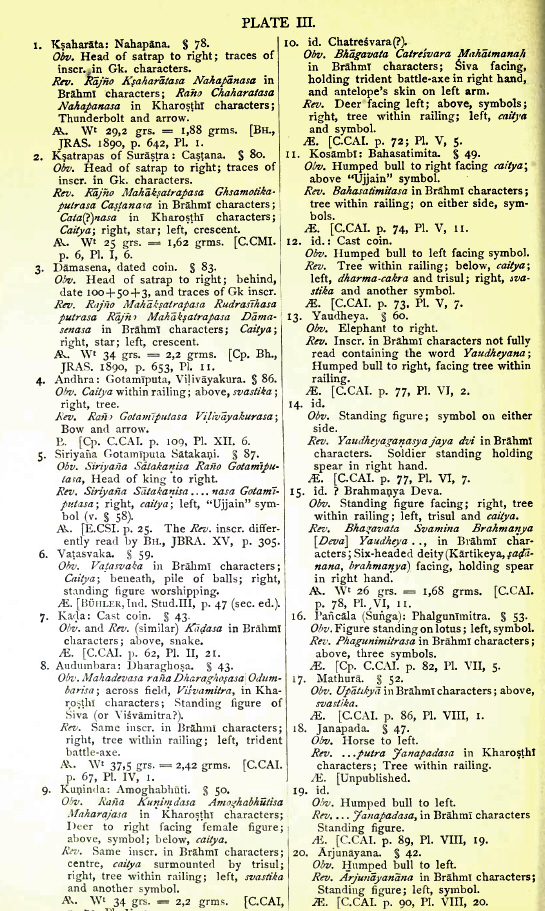

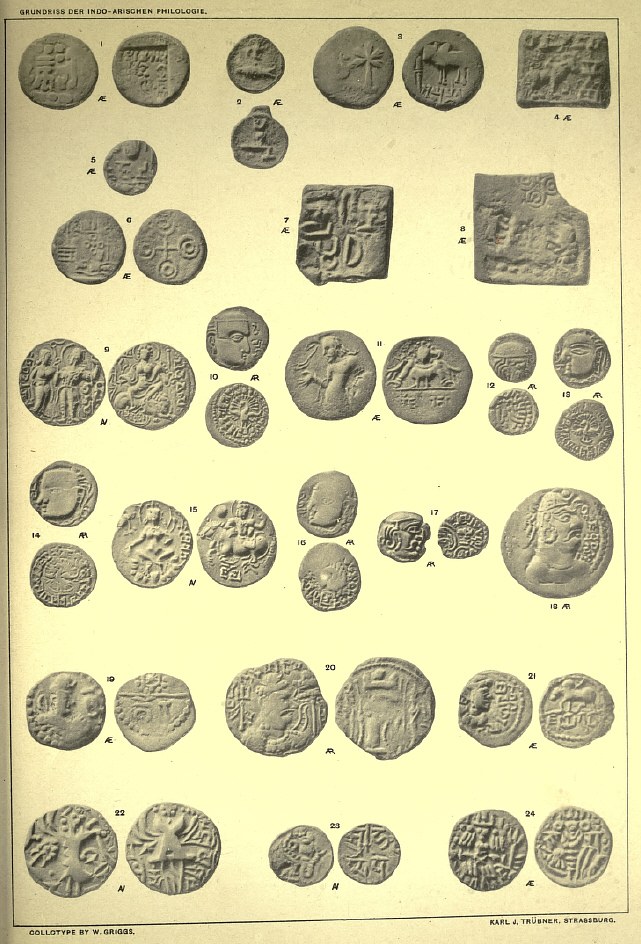

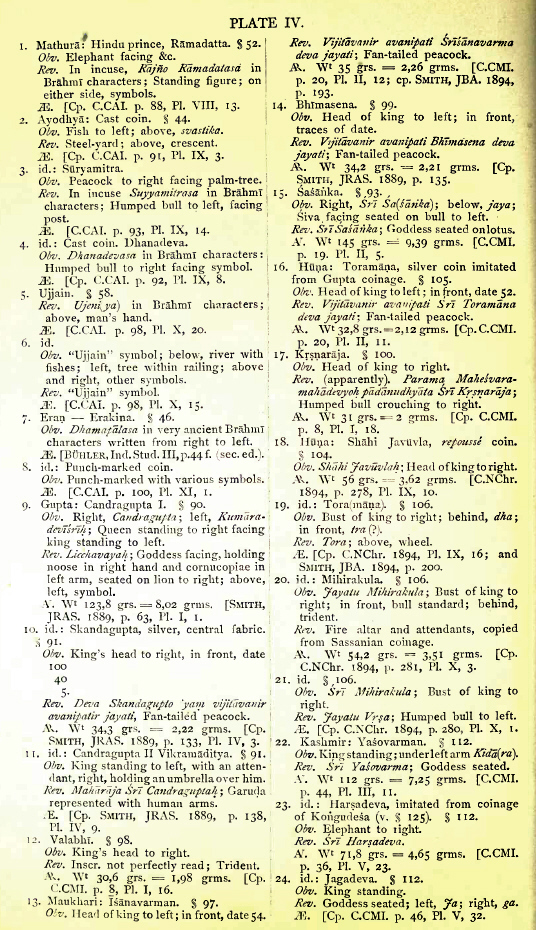

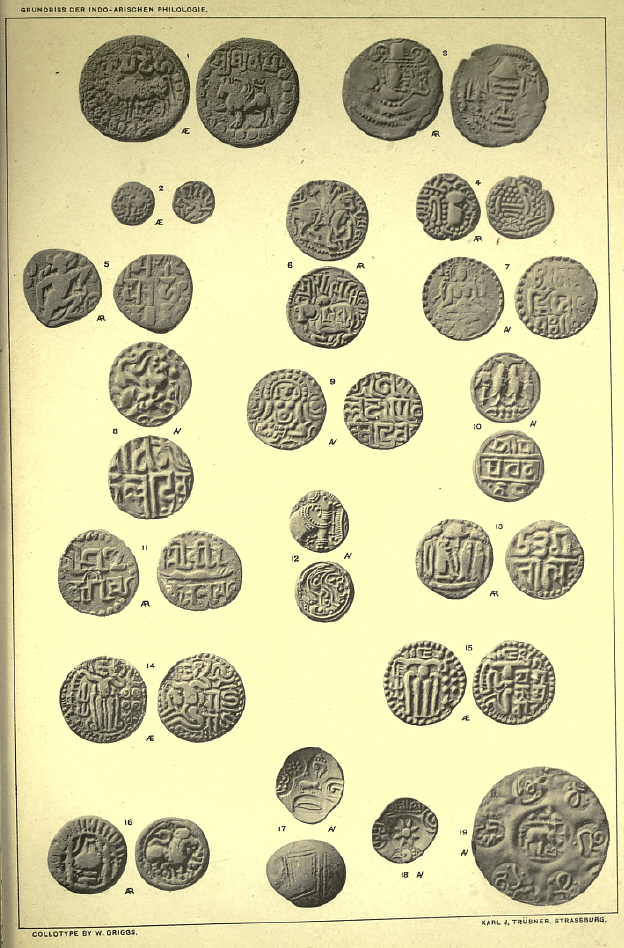

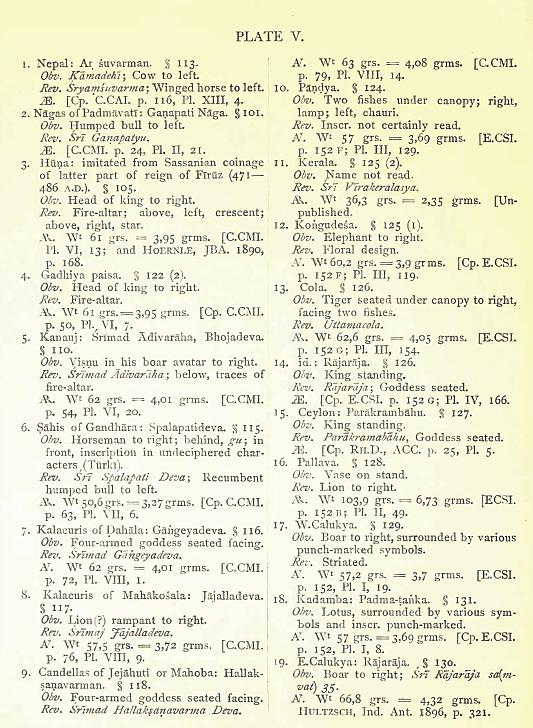

Zur Einführung in ein genaueres Studium indischer Münzen sind hier die Tafeln Rapson's mit ihren genauen Beschreibungen wiedergegeben.

Rapson, E. J. (Edward James) <1861-1937>: Sources of Indian history : coins. -- Straßburg : Trübner, 1897. -- 55 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- (Grundriss der Indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 2,3b). -- Pl. I. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/sourcesofindianh00rapsuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-14.

Rapson, E. J. (Edward James) <1861-1937>: Sources of Indian history : coins. -- Straßburg : Trübner, 1897. -- 55 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- (Grundriss der Indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 2,3b). -- Pl. II. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/sourcesofindianh00rapsuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-14.

Rapson, E. J. (Edward James) <1861-1937>: Sources of Indian history : coins. -- Straßburg : Trübner, 1897. -- 55 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- (Grundriss der Indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 2,3b). -- Pl. III. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/sourcesofindianh00rapsuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-14.

Rapson, E. J. (Edward James) <1861-1937>: Sources of Indian history : coins. -- Straßburg : Trübner, 1897. -- 55 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- (Grundriss der Indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 2,3b). -- Pl. IV. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/sourcesofindianh00rapsuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-14.

Rapson, E. J. (Edward James) <1861-1937>: Sources of Indian history : coins. -- Straßburg : Trübner, 1897. -- 55 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- (Grundriss der Indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 2,3b). -- Pl. V. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/sourcesofindianh00rapsuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-14.

Zu: Brown, C. J.: The coins of India (1922)