Zitierweise / cite as:

Thomson, S. J. (Samuel John) <1853-1936>: An Indian village. -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlasenschaften, 5.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-29. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen055.htm

Erstmals publiziert in:

Thomson, S. J. (Samuel John) <1853-1936>: The silent India, being tales and sketches of the masses. -Edinburgh, London : Blackwood, 1913. . -- ix , 365 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- S. 15 - . -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/silentindiabeing00thomiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-29. -- "Not in copyright"

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2008-03-29

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Public Domain

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

S. J. Thomson war Mitarbeiter des Indian Medical Service

In view of the fact that, as said before, two-thirds at least of the population are concerned with agriculture, it may be not altogether uninteresting [S. 16] to consider the question of land tenure, and to depict, however feebly, the conditions under which the average villager lives. As regards the first point : in 1793 Lord Cornwallis introduced a permanent settlement into Bengal by which the demand of the State was fixed for ever a measure the wisdom of which has been largely questioned. Nowadays over the greater part of India a system of periodical settlement has been established, under which the State demand is revised at recurring periods of from ten to thirty years. When the revenue is assessed by the State permanently or temporarily on a individual or on a community owning an estate analogous to that of a landlord, the assessment is known as "zamindari" ; and when the revenue is imposed on individuals who are, or represent, the actual occupants of holdings, the arrangement is known as "ryotwari." Under either system there may be rent-paying sub-tenants.

In the surveyed and settled area 47 per cent of the total area is held by peasant proprietors, while 20 per cent is held by permanently settled and 33 per cent by temporarily settled proprietors. It is stated in the last Blue-Book on "Moral and Material Progress in India," from which the above remarks are taken, that the burden of the land revenue per head of population is about eighteen - pence. It is further stated that the British Government takes a very much smaller share of the gross produce than was customary [S. 17] before the days of our rule, and that the assessments are lower than those that prevail generally in Native States. Increased productiveness, due to private improvements, is considerately dealt with, reductions are made in the case of deterioration, and large remissions allowed on occasions of distress such as that caused by famine. A noticeable fact is the large proportion of the assessed area held by peasant proprietors.

With this brief sketch of the tenure under which he holds his land, we pass on to the consideration of the life of the agriculturist, and perhaps the best plan will be to attempt to describe a village and its inhabitants in Upper India to-day, in an area which the Government of India has described in a recent Parliamentary paper as fairly typical of the whole of the dependency.

Heera Singh is what we should call a small farmer, of good caste, and living in the little village of Muddunpore in the United Provinces, owning his own land of some four or five acres in extent, which has been in his family for many years, albeit it is rather heavily mortgaged to Buttun Lai, the village shopkeeper and moneylender, on account of the expenses incurred in the marriage of his two daughters some years ago. He has two sons, stalwart lads, who help him in his work, so that his mind is at ease as to the releasing of his soul and its saving from Hell when the time comes for him to be laid to draw his last breath upon the ground and for his body [S. 18] to be cremated at the burning-ghat. One is very anxious to become a recruit in the "Sirkar's" (Government's) army, but his father needs him on the farm, and parental authority is respected among uneducated folk in India. Old Mehr Singh, the Sikh native officer who has retired and owns a little land in a village a few miles off, is responsible for unsettling his mind, and the lad often trudges off across the fields to listen to the old man's stories of how Roberts Sahib Bahadur marched from Kabul to Kandahar and scattered the Afghan army there. Mehr Singh had marched with him in a regiment which averaged five feet nine in height, and was never tired of relating, with additions as time wore on, the gallant deeds they all performed there. He told of the race up to the guns in the charge at Kandahar, and how a little Goorkha, first up with a Highlander, jumped upon the smoking field-piece and rammed his cap with its badge down the muzzle, shouting "This gun belongs to my regiment," and many other stories to which the villagers listen with breathless interest. The boy had almost run away once when he stood by and saw the old "Subadar," in full uniform and all his medals on, and with his long moustache and whiskers tied behind his neck (for a Sikh never cuts his hair, and must carry cold steel upon his person), come out and present the hilt of his sword to be touched by the Colonel Sahib, who happened to be camping and shooting by the small lake near [S. 19] the village. The Colonel Sahib had a long talk with the veteran, and said things which brought the fire back to the old man's eye, and nearly sent the admiring lad off to the nearest recruiting station.

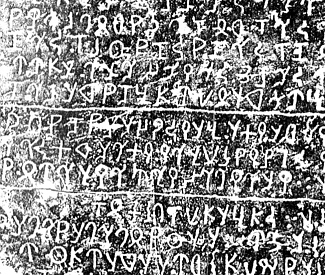

Country cart and baggage.

Heera Singh has a wife much younger than himself, who, however, sees nothing in the disparity of age, since it is so common in the country. She has more liberty than her sisters in the towns, but has practically never left the vicinity of the village, nor desired to do so, since she was brought with great banging of tom-toms and flaring of torches to her husband's house a long while ago. She had been betrothed as a child, but was not brought to him until after puberty. Once a year, it is true, she has an outing, anxiously looked forward to, albeit with some timidity, when she goes with her husband and relations in a happy, merry party to wash their sins away in the Holy River, and see the wonderful gathering of pilgrims at sacred Hardwar. They are carriage-folk, and own a great canopied cart drawn by two fine milk-white bullocks, with blue beads round their necks, in which she goes in state to local festivities and to see her relations, or to occasionally visit, closely veiled, the village where the weekly market is held, some five miles away, where pins and needles, thread and tape, oval mirrors folding into tin cases, stockings and mufflers with fearful and wonderful stripes, and a great deal of other cheap rubbish produced in Manchester and Birmingham, can be purchased. [S. 20] She is not devoid of vanity, and the skirt she wears, and the shawl or "chudder" with which she carefully covers her head and face on such occasions, are of the best material from Kampore and Dacca, and elaborately embroidered. Heera Singh himself is rarely seen in gala dress ; when he is, he appears with a voluminous white "puggri" on his head, a long purple coat of a strange cut ornamented with gold filigree, and his legs and feet adorned with thick white stockings, far too large for him, and projecting some inches beyond his toes. How he gets them into the red leather shoes with the green patches on the turned-up points, is a mystery.

Poor Lukshmi, it must be conceded, is not enlightened. She regards higher education with misgivings, as calculated to disturb religious beliefs and engender contempt for parents ; she views an owl with horror ; makes obeisance to the god of fire when she lights the lamps at night ; and has conscientious objections to vaccination, as an operation likely to offend the goddess connected with the appearance of smallpox. She has three little children, besides the grown-up ones ; there have been others between, but two, fortunately daughters, were swept away when cholera last visited the village, and one, a little boy, unhappily passed away from some unknown malady most probably caused by a stroke of the Evil Eye. She has help, but there are numerous domestic duties which she sees to herself: the [S. 21] care of the young ones, the cooking of the food, the mending of the clothes, &c. Then the idol must be kept cool by libations of water, probably brought back in bottles on the occasion of the last visit to Hardwar ; there are the daily devotions, and the consultations with the priest as to auspicious days for the performance of certain rites and duties ; the visits to festivals and relatives, &c., &c. Lukshmi's life is not dull from her point of view, and she is quite content with her position, though she cannot read or sign her name to save her life. She hears of the doings of her European sisters with no envy, but some surprise, but then, as she and her husband pleasantly agree, "All sahibs are more or less mad."

Much ignorant nonsense is spoken and written about the miserable and degraded position of woman in India. She holds the same power and influence which women, as women, exercise all the world over. Such statements are (as Mark Twain says regarding the report of his death) "much exaggerated."

Heera Singh himself can only just read and write sufficiently in the vernacular to keep a check on the machinations of Ruttun Lai the trader, and to carry on a limited correspondence with his acquaintances on scraps of thin brown country paper, weirdly addressed, and incapable of comprehension by any but the local native postman ; but he knows his own business very well. His time is spent almost entirely in the [S. 22] fields, and his system of cropping is arranged to suit the rainfall, which, in Upper India, in normal years, is plentiful between the end of June and the middle of October, with a lighter fall in the cold weather about Christmas. The summer crop constitutes the "khareef," and the winter the "rabi." January and February are largely occupied in irrigating the "rabi" crop, which will be harvested in March and April. This is a busy time, water is either obtained from wells, or is lifted from lakes in baskets by two or four men, who swing the receptacle with ropes into the water, and then empty it at the higher level into the channel by which it is meant to flow into the fields. It is very hard work, and the method cannot be employed when the lift is more than a few feet. Harvesting is very differently carried out to what it is in England. The crop being cut with the sickle, is carried at once to the threshing-floor, a well beaten-down piece of land in the fields, where the grain is trodden out by cattle as it was in the days of the Israelites, and the winnowing is performed by letting the grain fall from a height on a windy day, when the husks are blown away as the kernels fall to the ground.

May and June are slack months, in which he repairs his house and does various odd jobs for which there is no time in the busy seasons. July is fully occupied with sowing and weeding, and in August and September comes the ploughing for the "rabi." In October he commences to gather in [S. 23] the "khareef" harvest and sows for the winter crop. The latter work over, he finishes the winding-up of the "khareef," and irrigates the "rabi" until the end of the year.

The "khareef" is the summer crop, and includes various cereals, maize (Zea Mays), rice, millets, of which the principal are "juar" (Andropogon sorghum) and "bajra" (Pennisetum typhoideum, or spicatum), pulses, oil-seeds, and fibres. In the "rabi" are included wheat, barley, oats, "gram" (chick pea), peas, lentils, potatoes, mustard, and various pulses. There are special crops, such as sugar-cane, cotton, poppy, tobacco, &c., but these are not often attempted by the small cultivator, though many of the villagers grow a little tobacco for their own use. Rude as is the system, still the principle of rotations is preserved, much intelligence is shown in the selection of the right soil and situation for each crop, and even what strikes a European with surprise, the frequent plan of growing mixed forms of produce in the same field, is no haphazard arrangement, but is adopted as a sort of insurance, so that if one crop fails the other may succeed.

Among the things which probably most strike the traveller on his return home to England after a long absence, are the number of hedges and the general orderliness of things agricultural (which Wendell Holmes has also noted), and, if his exile has been passed in the East, the great size of the horses, cattle, and sheep, and the deserted appearance [S. 24] of the fields. In India the last are teeming with life and colour : men, women, and children at work, or passing along the roads or footpaths, give a bustling aspect to the scene, and the blue and red garments mostly worn by the agricultural women, dotted about among the green crops, give a very bright and pleasing impression to the eye.

During the day the village is practically abandoned, and somehow or other there always seems to be something or other to employ the people sowing, weeding, irrigating, harvesting, and planting out rice. When the crops are ripening, little rough platforms are erected in the fields, from whence boys and men watch these day and night, waging an incessant war against the birds of the air, especially flocks of parrakeets (there are no parrots in India), shrieking all the time, and hurling stones with much accuracy from slings against the feathered marauders.

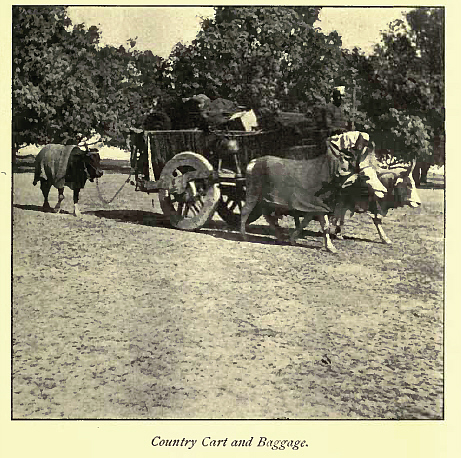

Irrigating the fields from wells.

With his two lusty sons, Heera Singh needs little outside help, but when he does, he pays mostly in kind, that is, in allowances of flour,grain, and pulses, with an occasional rupee or two. One of his sons guides the oxen up and down the ramp when he is lifting water in a big leathern bag from the well to irrigate his fields, and he usually himself stands above the well and directs the water into the proper channels. This operation is rather complicated, and is very important : the field is divided into little enclosures by means of slight elevations of soil some six [S. 25] inches in height, and each is irrigated in turn and then cut off by closing the opening in the little dam. He lives literally, as impecunious landlords have been advised to do in England, upon the produce of his own land, for the corn is ground into flour in his own house by the women, the pulses, oils, and spices come out of his own fields, and his simple regular diet consists of little else. Water is his only beverage ; the jungle supplies wood for fuel ; the tobacco he smokes, and the hemp he uses for his well-ropes, are grown on the farm ; and what he sells is for taxes, wages, clothes, and his very limited extravagances. Now and again a great charge, such as the marriage of a daughter, has to be met, but in normal years he usually has little financial trouble, and is seldom behindhand in his payment of revenue. Cattle for milk and labour he possesses : with sheep and poultry he has little concern, for his caste prevents their use as food.

Muddunpore lies in the fields, but is situated on one side close to a grove of mango-trees owned by Heera Singh, under which the village cattle rest during the great heat of the day, after having been driven out in the early morning, by a small ragged urchin armed with a long bamboo stick, to forage on the waste and fallow land in the neighbourhood. The site is well wooded. The "mohwa" (Brassia latifolia), a tall, handsome tree with yellow waxy flowers which fall to the ground in April, and are eaten both raw and cooked, throws [S. 26] its welcome shade over the ground. In some parts of the country it furnishes an important source of food-supply. The flowers are sweet and greatly beloved of bears ; the sugar they contain is readily converted into alcohol, and much native spirit is distilled from them. The "mango" often grows to a large size, and its luscious fruit is more important as a source of food than that of all the other trees put together. It bears produce ten years after being planted, and will yield a crop for a generation or more growing readily in most soils, though the fruit varies much in taste and flavour. In May and June the whole population seems to be eating it, in the same way that they are all munching the sugar-cane in December and January. The "neem" (Melia azadirachta) is a slow-growing but shady tree, with narrow leaves, and yielding a small berry, the oil of which is much prized as medicine. The invaluable bamboo, of which the uses are innumerable; the "sheeshum" (Dalbergia sissoo), affording excellent timber; the "babool" (Acacia arabica), with its little balls of fragrant flowerets, are also probably there. This last tree yields tannin from the bark, while the timber is utilised for making agricultural implements and carts especially the naves of wheels. It is unpretending in appearance, lightly foliaged and thorny, and from its boughs very commonly may be seen hanging the marvellous nests of the clever little finches the "bayas" or weaver birds (Ploceus baya).

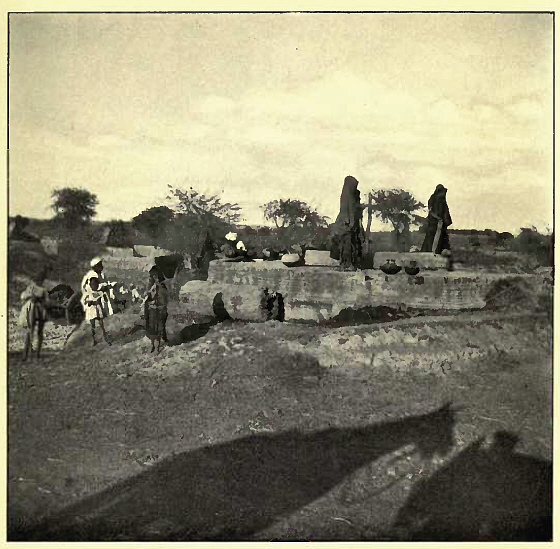

[S. 27] There are probably not more that forty or fifty huts in the village built of mud and thatched with grass, and nearly all consisting of one room scantily furnished ; though sometimes there is an enclosed space in front or behind, in which domestic duties are performed and articles stored, and which affords more seclusion to the women of the household. If the occupant possesses a bullock or bullocks, they are tied up in this enclosure being fed out of earthenware vessels embedded in raised mounds of earth. The vicinity of the dwelling is far from what the sanitarian approves of, for the general rubbish and sweepings are piled up here for fear of theft, before their removal for use as manure in the fields ; but the interior of the hut is usually scrupulously clean, despite the fact that it is regularly daubed over with a mixture of mud and water and a little cow-dung. This last is carefully kept for use as fuel, and usually decorates the external walls of the dwelling in patches stuck on to dry in the sun. Landowners, it is true, will often allow the villagers to cut a little wood from their "dhak" jungles, as it is of little use for other purposes, so it is known as "the poor man's tree" ; and curiously enough the author found in South Africa that a somewhat similar tree was known as "the Kaffir tree," for apparently very much the same reason. On one side of the village is the pond -- an unsightly excavation, holding stagnant water and affording an excellent breeding-ground for mosquitoes [S. 28] -- in which pigs wallow and from which the cattle drink. Its presence is inevitable, since it has been caused by the removal of the earth for the purpose of building and repairing the huts -- landlords naturally objecting to their fields being so utilised. Then there are the village wells -- some for high caste and some for low caste people, -- where the women gather to draw water for drinking and other purposes, and to discuss in endless and noisy conversation the doings of their neighbours, &c. ; while close by is the council-tree of the community, surrounded by a raised earth platform, where the village elders sit and smoke and talk far into the warm night.

The village well.

The little village temple is nearly always overshadowed by the sacred peepul-tree (Ficus religiosa). There are usually gods in these trees -- demons prefer the tamarind. The former has large leaves hanging loosely on a long stalk, and which move with the least breath of air ; so that when all is apparently still they rustle mysteriously, and the movement is attributed to supernatural causes.

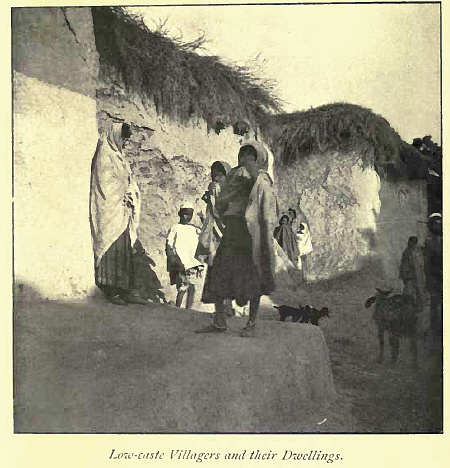

There are few shops in Muddunpore. Buttun Lai squats in a shanty in the principal street, watching over a number of open sacks holding food-stuffs, spices, salt, and sweat-meats, amid a cloud of hornets and wasps, and with a great brass bell hanging in front of him. Lower down, in a similar shop, iron and brass cooking-pots, big-headed nails, matches, and (recently) awful [S. 29] cigarettes, can be purchased. There are sure to be several potters -- very useful servants to the community -- fashioning out the mud vessels with the aid of the wheel of which the use goes back to remote antiquity. And on the outskirts of the settlement the wheelwright has his workshop, where he builds and repairs the heavy country carts used in the rural areas and drawn by oxen and buffaloes -- ponderous conveyances constructed solely of wood, bamboo, and string, which by yielding survive the jolts and shocks incidental to passage over the rough country tracks. The public buildings consist of the village shrine, with a few trees round it, and the shed in which the children absorb some scraps of elementary education through the medium of an elementary schoolmaster. A little apart from the rest of the dwellings is a small group of wretched tenements, where dwell the very low caste "chamars" -- the people who flay dead animals for the sake of their skins and live largely on the flesh. None of the streets are paved the -- foot goes into some six inches of dust or mud. Buffaloes, goats, cows, and sacred bulls wander all over the site ; monkeys swarm unmolested over the houses, roads, and trees; while scores of ownerless pariah-dogs, of all shapes and sizes, roam about the village and dispute with their own kind during the day, and with the jackals at night, for a precarious meal of offal and garbage.

Low-caste villagers and their dwellings.

This is a purely Hindoo village, and there is no [S. 30] provision for Muhaminadan occupation -- those who come here for work living with their co-religionists in a hamlet a little way off; but the general description will apply to most little centres of population in Upper India, where the two sects live and work together as they have done for centuries.

Heera Singh's house is the only two-storied residence in Muddunpore, and it also possesses the crowning glory of a tiled roof. It is quadrangular in shape, with a courtyard in the centre, in which is the little altar, with the "tulsee" or holy basil to be placed on the tongue of the dying, and where are also tethered the bullocks ; while in a corner of the same enclosure a weedy pony is tied by his head and heels to pegs in the ground under a grass thatch. This is the riding pony of the proprietor, and is of more value than its appearance indicates, on account of its steady amble ; and it is surprising how fast and comfortably a rider not given to equestrian feats can get over the ground with an animal trained to this peculiar gait. The members of the family occupy the upper rooms, while the ground floor -- much of it consisting of open verandahs -- is thronged with poor relations and hangers-on, who loaf about the place, do odd jobs when required, and roll themselves up in their blankets to sleep when and where they like. The local status and reputation of an Indian gentleman is largely gauged by the extent of his toleration and support of the tag-rag [S. 31] and bobtail which infests him ; but, apart from this, the people of India are probably the most charitable in the world, and such a thing as State relief is not necessary except in famine times. Poorhouses exist in most towns, but are usually either empty or occupied by lepers, blind folk, waifs and strays.

Our Eastern farmer is an industrious and thrifty man, and he and his sons and employés are up at daylight, and having repeated some texts from the Puranas, made oblations to the sun, cleaned their teeth with sticks which they throw away, proceed, muffled up in blankets over their heads and bodies and with nothing round their legs, to the scene of their labours. They will wash themselves all over at a well in the fields, say their prayers, take their food, smoke the pipe of peace, sleep for an hour or two during the great heat of the day, and return home after their work at sunset. Then they again pray, take the principal meal, and after more smoking and perchance a chat under the council tree, lie down to rest, wrapped up in their blankets, on a rough bed constructed of wood and laced with stout string.

The little community is a distinct unit in itself, and, differing from conditions in other countries, most of the labourers work for themselves and not for employers a fact to be borne in mind by oracles on wage-statistics. Lalloo the weaver and his caste-fellows provide most of the clothing and blankets ; Buddhoo the sweeper and his class look [S. 32] to the conservancy of the place ; Paiga the watchman (a modest servant of the Government, clad in a blue jean coat and red puggri, registrar of births and deaths, and the usual ultimate source of evidence in police cases) rends the air at night with wild howls to keep off marauders ; Seetul the water-carrier dispenses that commodity to consumers from his leather bag ; and the barber shaves the community, retails gossip, and usually acts as the preliminary go-between among the parents when arrangements are made for alliances between the young folk of the village, before the family priest opens formal negotiations. The Brahman at the shrine attends to their religious wants; while the "patwari" keeps the revenue accounts and records the changes of tenure of land on curious, portable, and dirty maps.

Life proceeds very quietly in the village, with few excitements beyond the religious festivals, the visits to the neighbouring weekly market, the occasional inspection by a "sahib" connected with one or other of the State departments, or the outbreak of epidemic disease. Literature is at a discount, for few can read, and the tastes of those who can run mostly towards descriptions of the remarkable deeds and exploits of worthies in the distant past akin to the classic legend of the Great Panjandrum ; or else to the counsels and wisdom of religious sages. Politics, art, science, and the doings of the outside world interest them but little, and the stray vernacular newspaper with its [S. 33] editor's views as to proper government, which occasionally reaches the village, is perused and discussed in some bewilderment. Of crime there is very little -- the circumstances of all are so well known that theft is almost certain of detection ; female frailty is attended with more deterrent consequences than the divorce court ; and outbreaks of violence between individuals are few and far between. The village council settles very many disputes, and ostracism from the caste is a terrible penalty. Heera Singh, as headman, has a good reputation for maintaining order in his village, -- the little unpleasantness about the landmark between him and a neighbouring landowner, which happened about the time that the latter was found clubbed to death in his field, is well-nigh forgotten, though it might have gone hard with him had not Paiga the watchman and another villager fortunately chanced to observe the accused man stretched unconscious on a bed of sickness some twenty miles away, at the exact time of the murder.

Life being what it is, there is of course a dark side to the picture which has been drawn. There are times when cholera stalks through the little settlement, taking its victims from all indiscriminately : the strong breadwinners, the infants, and the old and feeble. Plague has of late years exacted its human toll ; malaria, that curse of India, is an ever-threatening foe ; and now and again famine holds the people in its fell [S. 34] grip. But the peasant bows his head, imbued with a spirit of resignation which is a merciful gift to its possessor, and presently the clouds roll by and the sun shines once more.

This is a rough sketch, which must be somewhat modified according to the particular part of the country, of the life and environment of probably at least two-thirds of the population of India the real India, the voiceless simple people of which politicians know so little and are perhaps so tempted to ignore. Yet they are very real men and women, and with thoughts and feelings very deeply rooted, and worthy of consideration. They are not believers, it is true, in what Mr A. C. Benson calls "the gospel of push" ; but then, as that writer goes on to observe, it has got to be proved that one was sent into the world to be "effective," and it is not even certain that a man has fulfilled the higher law of being if he has made a large fortune by business. Heera Singh and his friends have certain consolations, they seldom suffer from "brain-storms" and the something or other "ego," suicides are rare, and the death registers have no column for "neurasthenia."

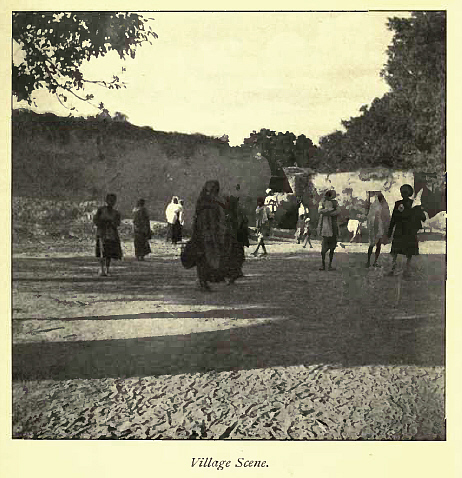

Village Scene.

Zu: 5.6. Burial custons / by Edward Balfour (1885)