Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis

1858

14. Quellen auf Arabisch, Persisch und in Turksprachen

9. Zum Beispiel:

'Alī Ibrāhīm Khān: Tārīkh-i Ibrāhīm Khān (A.D. 1786)

<Auszüge>

hrsg. von Alois Payer

mailto:payer@payer.de

Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur

indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 14. Quellen auf Arabisch, Persisch und in Turksprachen.

-- 9. Zum Beispiel:

'Alī Ibrāhīm Khān: Tārīkh-i Ibrāhīm Khān (A.D. 1786)

<Auszüge>. -- Fassung

vom 2008-05-18. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen149.htm

Erstmals publiziert als:

The history of

India, as told by its own historians : The Muhammadan period / edited from the

posthumous papers of the late Sir H. M. [Henry Miers] Elliot [1808 - 1853], by John Dowson

[1820 - 1881]. -- London : Trübner,

1867-77. -- 8 Bde. ; 23 cm. -- Bde. 4-8 Titel: " ... The posthumous papers of the late Sir H. M. Elliot ... edited and

continued by Professor John Dowson." -- Bd. 8. -- S. 257 - 297. -- Online:

http://persian.packhum.org/persian/main. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-06

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2008-05-18

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Public domain.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Sanskrit von

Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht

dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B.

Tahoma.

EXTRACTS.

As the comprehension of the design of this work is

dependent on a previous acquaintance with the origin and genealogy of [S.

258] Bālājī

Rāo, the eloquent pen will first proceed to the discussion of that subject.

Origin and Genealogy of the Mahrattas.

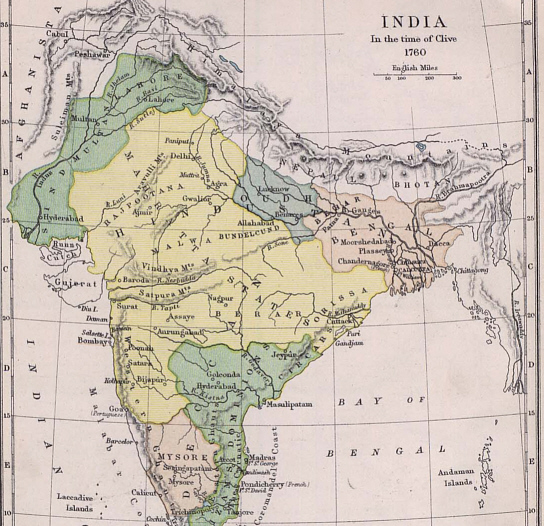

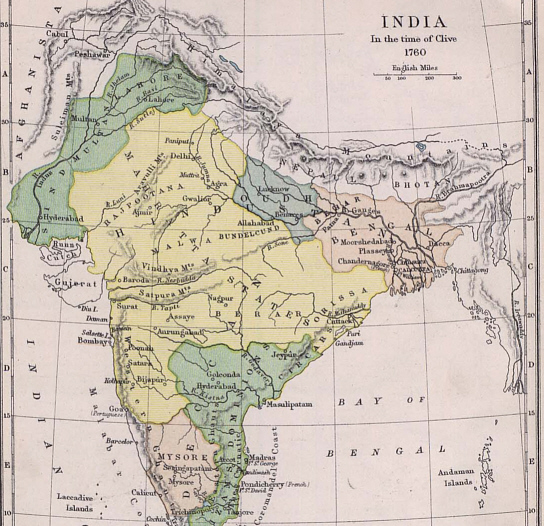

Abb.: Das Mahratta-Reich um 1760 (in gelb)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Be it not hidden, that in the language of the people

of the Dakhin, these territories and their dependencies are called "Dihast,"

and the inhabitants of the region are styled "Mahrattas." The Mahrattī

dialect is adopted exclusively by these classes, and the chieftainship of

the Mahrattas is centred in the Bhonsla tribe. The lineage of the Bhonslas

is derived from the Ūdīpūr Rājas, who bear the title of Rānā; and the first

of these, according to popular tradition, was one of the descendants of

Naushīrwān. At the time when the holy warriors of the army of Islām

subverted the realms of Īrān, Naushīrwān's descendants were scattered in

every direction; and one of them, having repaired to Hindūstān, was promoted

to the dignity of a Rāja. In a word, one of the Rānā's progeny afterwards

quitted the territory of Ūdīpūr, in consequence of the menacing and

disordered aspect of his affairs, and having proceeded to the country of

the Dakhin, fixed his abode in the Carnatic. The chiefs of the Dakhin,

regarding the majesty of his family with respect and reverence, entered into

the most amicable relations with him. His descendants separated into two

families; one the Aholias, the other the Bhonslas.

Memoir of Sāhūjī, of the tribe of Bhonslas.

Sāhūjī was first inrolled among the number of Nizām

Shāh's retainers, but afterwards entered into the service of Ibrāhīm 'Ādil

Shāh, who was the ruler of the Kokan. In return for the faithful discharge

of his duties, he received in jāgīr the parganas of Pūnā,

etc., where he made a permanent settlement after the manner of the

zamīndārs. Towards the close of his life, having attained the high

honour of serving the Emperor Jahāngīr, he was constantly in attendance on

him, while his son Sivajī stayed [S. 259] at the jāgīr. As Ibrāhīm 'Ādil Shāh

for the space of two years was threatened with impending death, great

disorder and confusion prevailed in his territories from the long duration

of his illness; and the troops and retainers, whom he had stationed here and

there, for the purpose of garrisoning the forts, and protecting the frontier

of the Kokan, abandoned themselves to neglect in consequence of their

master's indisposition.

Memoir of Siva, the son of Sāhū.

* * Ultimately, the Emperor Aurangzeb, the bulwark of

religion, resolved upon proceeding to the Dakhin, and in the year 1093 A.H.

bestowed fresh lustre on the city of Aurangābād by the favour of his august

presence. For a period of twenty-five years he strove to subvert the

Mahratta rule; but as several valiant chieftains displayed the utmost zeal

and activity in upholding their dynasty, their extermination could not be

satisfactorily accomplished. Towards the close of His Majesty's lifetime, a

truce was concluded with the Mahrattas, on these terms, viz. that three per

cent. out of the revenues drawn from the Imperial dominions in the Dakhin

should be allotted to them by way of sar deshmukhī; and accordingly

Ahsan Khān, commonly called Mīr Malik, set out from the threshold of royalty

with the documents confirming this grant to the Mahrattas, in order that,

after the treaty had been duly ratified, he might bring the chiefs of that

tribe to the court of the monarch of the world. However, before he had had

time to deliver these documents into their custody, a royal mandate was

issued, directing him to return and bring back the papers in question with

him. About this time, His Majesty Aurangzeb 'Ālamgīr hastened to the eternal

gardens of Paradise, at which period his successor Shāh 'Ālam (Bahādur Shāh)

was gracing the Dakhin with his presence. The latter settled ten per cent.

out of the produce belonging to the peasantry as sar deshmukhī on the

Mahrattas, and furnished them with the necessary documents confirming the

grant. [S. 260]

When Shāh 'Ālam (Bahādur Shāh) returned from the

Dakhin to the metropolis, Dāūd Khān remained behind to officiate for

Amīru-l umarā Zū-l fikār Khān in the government of the provinces. He

cultivated a good understanding with the Mahrattas, and concluded an

amicable treaty on the following footing, viz. that in addition to the

above-mentioned grant of a tithe as sar deshmukhī, a fourth of

whatever amount was collected in the country should be their property, while

the other three-fourths should be paid into the royal exchequer. This system

of division was accordingly put in practice; but no regular deed granting

the fourth share, which in the dialect of the Dakhin is called chauth,

was delivered to the Mahrattas. When Muhammad Farrukh Siyar sat as Emperor

on the throne of Dehlī, he entertained the worst suspicions against

Amīru-l umarā Saiyid Husain 'Alī Khān, the chief of the Bārha Saiyids.

He dismissed him to a distance from his presence by appointing him to the

control of the province of the Dakhin. On reaching his destination, the

latter applied himself rigorously to the task of organizing the affairs of

that kingdom; but royal letters were incessantly despatched to the address

of the chief of the Mahrattas, and more especially to Rāja Sāhū, urging him

to persist in hostilities with Amīru-l umarā. * *

In the year 1129 A.H. (1717 A.D.), by the intervention

of Muhammad Anwar Khān Burhānpūrī and Sankarājī Malhār, he concluded a

peace with the Mahrattas,

on condition that they would refrain from committing depredations and

robberies, and would always maintain 18,000 horsemen out of their tribe

wholly at the service of the Nāzim of the Dakhin. At the time that

this treaty was ratified, he sealed and delivered the documents confirming

the grant of the fourth of the revenues, and the sar deshmukhī of the

province of the Dakhin, as well as the proceeds of the Kokan and other

territories, which were designated as their ancient dominions. At the same

period Rāja Sāhū appointed Bālājī, son of Basū Nāth (Biswa Nāth), who

belonged [S. 261] to the class of Kokanī Brahmins, to fill the post of his vakīl

at the Court of the Emperor; and in all the districts of the six provinces

of the Dakhin he appointed two revenue commissioners of his own, one to

collect the sar deshmukhī, and the other to receive the fourth share

or chauth. * *

Amīru-l umarā Husain 'Alī, having increased the

mansabs held by Bālājī, the son of Basū Nāth, and Sankarājī Malhār,

deputed them to superintend the affairs of the Dakhin, and sent them to join

'Ālim 'Alī Khān. * * After the death of Bālājī, the son of Basū

Nāth, his son, named Bājī Rāo, became his successor, and Holkar, who was a

servant of Bālājī Rāo, having urged the steed of daring, at his master's

instigation, at full speed from the Dakhin towards Mālwā, put the (subadār)

Giridhar Bahādur to death on the field of battle. After this occurrence, the

government of that province was conferred on Muhammad Khān Bangash; but

owing to the turbulence of the Mahrattas, he was unable to restore it to

proper order. On his removal from office, the administration of that region

was entrusted to Rāja Jai Singh Sawāi. Unity of faith and religion

strengthened the bonds of amity between Bājī Rāo and Rāja Jai Singh; and

this circumstance was a source of additional power and influence to the

former, insomuch that during the year 1146 (1733 A.D.) he had the audacity

to advance and make an inroad into the confines of Hindūstān. The grand

wazīr 'Itimādu-d daula Kamru-d dīn Khān was first selected by the

Emperor Muhammad Shāh to oppose him, and on the second occasion Muzaffar

Khān, the brother of Samsāmu-d daula Khān-daurān. These two, having entered

the province of Mālwā, pushed on as far as Sironj, but Bājī Rāo returned to

the Dakhin without hazarding an engagement. * *

In the second year after the above-mentioned date,

Bājī Rāo attempted another invasion of Hindūstān, when the wazīr

'Itimādu-d daula Kamru-d dīn Khān Bahādur and the Nawāb Khān-daurān Khān

went forth from Dehlī to give him battle. * * On this occasion

several engagements took place, but [S. 262] victory fell to the lot of the wazīr;

and peace having been ultimately concluded, they both returned to Dehlī.

In the third year from the aforesaid date, through the

mediation of Amīru-l umarā Khān-daurān Khān Bahādur, the government

of Mālwā was bestowed on Bājī Rāo, whereby his power and influence was

increased twofold. The Rāo in question, having entered Mālwā with a numerous

force, soon reduced the province to a satisfactory state of order. About the

same time he attacked the Rāja of Bhadāwar, and after putting him to flight,

devastated his territory. From thence he despatched Pīlājī with the view of

subduing the kingdom of Antarbed (Doāb), which is situated between the

Ganges and Jumna. At that very time Nawāb Burhānu-l Mulk had moved out of

his own province, and advanced through Antarbed to the vicinity of Āgra.

Pīlājī therefore crossed the Jumna, and engaged in active hostilities

against the above-named Nawāb; but having been vanquished in battle, he was

forced to take to flight, and rejoin Bājī Rāo. An immense number of his army

were drowned while crossing the Jumna; but as for those who were captured or

taken prisoners, the Nawāb presented each one with two rupees and a cloth,

and gave him permission to depart. Bājī Rāo, becoming downcast and

dispirited after meeting with this ignominious defeat, turned his face from

that quarter, and proceeded towards Dehlī. * *

Samsāmu-d daula Amīru-l umarā Bahādur, after

considerable deliberation, sallied forth from Shāh-Jahānābād with intent to

check the enemy; but Bājī Rāo, not deeming it expedient at the time to

kindle the flame of war, retired towards Āgra, and Amīru-l umarā,

considering himself fortunate enough in having effected so much, re-entered

the metropolis. This was the first occasion on which the Mahrattas extended

their aggressions so far as to threaten the environs of the metropolis.

Though most of the men in the Mahratta army are unendowed with the

excellence of noble and illustrious birth, and husbandmen, carpenters, and

shopkeepers abound among their soldiery, yet, as they undergo all sorts of

toil and fatigue in prosecuting a guerilla warfare, they [S. 263] prove superior to

the easy and effeminate troops of Hind, who for the most part are of more

honourable birth and calling. If this class were to apply their energies

with equal zeal to the profession, and free themselves from the trammels of

indolence, their prowess would excel that of their rivals, for the

aristocracy ever possess more spirit than the vulgar herd. The free-booters

who form the vanguard of the Mahratta forces, and marching in advance of

their main body, ravage the enemy's country, are called puīkārahs (pūīkārahs?);

the troops who are stationed here and there by way of picquets at a distance

from the army, for the purpose of keeping a vigilant watch, are styled

mātī, and chhāppah is synonymous in their dialect with a

night-attack. Their food consists chiefly of cakes made of jawār, or

bājrā, dāl, arhad, with a little butter and red pepper; and hence it

is that, owing to the irascibility of their tempers, gentleness is never met

with in their dispositions. The ordinary dress worn by these people

comprises a turban, tunic, selah (loose mantle), and jānghiah

(short drawers). Among their horses are many mares, and among the offensive

weapons used by this tribe there are but few fire-arms, most of the men

being armed with swords, spears, or arrows instead. The system of military

service established among them is this: each man, according to his grade,

receives a fixed salary in cash and clothes every year. They call their

stables pāgāh, and the horsemen who are mounted on chargers belonging

to a superior officer are styled bārgīrs. * *

Bālājī's Exploits.

When Bājī Rāo, in the year 1153 A.H. (1740 A.D.), on

the banks of the river Nerbadda, bore the burden of his existence to the

shores of non-entity, his son, Bālājī Rāo, became his successor, and after

the manner of his father, engaged vigorously in the prosecution of

hostilities, the organization and equipment of a large army, and the

preparation of all the munitions of [S. 264] war. His son continued to pass his days,

sometimes at war, and at other times at peace, with the Nawāb Āsaf Jāh. At

length, in the year 1163 (1750 A.D.), Sāhū Rāo, the successor of Sambhājī,

passed away, and the supreme authority departed out of the direct line of

the Bhonslas. Bālājī Rāo selected another individual of that family, in

place of Sāhū's son, to occupy the post of Rāja, and seated him on the

throne, whilst he reserved for himself the entire administration of all the

affairs of the kingdom. Having then degraded the ancient chieftains from the

lofty position they had held, he denuded them of their dignity and influence,

and began aggrandizing the Kokanī Brahmins, who were of the same caste as

himself. He also constituted his cousin, Sadāsheo Rāo, commonly called Bhāo

Rāo, his chief agent and prime minister. The individual in question was of

acute understanding, and thoroughly conversant with the proper method of

government. Through the influence of his energetic counsels, many

undertakings were constantly brought to a successful issue, the recital of

which would lead to too great prolixity. In short, besides holding the

fortress of Bījāpūr, he took possession anew of Daulatābād, the seat of

government of the illustrious sovereigns, together with districts yielding

sixty lacs of rupees, after forcibly wresting it out of the hands of

Nizāmu-l Mulk Nizām 'Alī Khān Bahādur. He likewise took into his service

Ibrāhīm Khān Gārdī, who had a well-organized train of European artillery

with him.

The Abdālī Monarch.

Ahmad Shāh Abdālī, in the year 1171 A.H. (1757-8 A.D.),

came from the country of Kandahār to Hindūstān, and on the 7th of Jumāda-l

awwal of that year, had an interview with the Emperor 'Ālamgīr II., at the

palace of Shāh-Jahānābād; he exercised all kinds of severity and oppression

on the inhabitants of that city, and united the daughter of A'azzu-d dīn,

own brother to His Majesty, in the bonds of wedlock with his own son, Tīmūr

Shāh. After an [S. 265] interval of a month, he set out to coerce Rāja Sūraj Mal Jāt,

who, from a distant period, had extended his sway over the province of Āgra,

as far as the environs of the city of Dehlī. In three days he captured

Balamgarh, situated at a distance of fifteen kos from Dehlī, which

was furnished with all the requisites for standing a siege, and was well

manned by Sūraj Mal's followers. After causing a general massacre of the

garrison, he hastened towards Mathurā, and having razed that ancient

sanctuary of the Hindūs to the ground, made all the idolators fall a prey to

his relentless sword. Then he returned to Āgra, and deputed his

Commander-in-Chief, Jahān Khān, to reduce all the forts belonging to the Jāt chieftain. At this time a dreadful pestilence broke out with great

virulence in the Shāh's army, so that he was forced to abandon his intention

of chastising Sūraj Mal, and unwillingly made up his mind to repair to his

own kingdom.

On his return, as soon as he reached Dehlī, the

Emperor 'Ālamgīr went forth with Najību-d daula Bahādur, and had an

interview with him on the margin of the Maksūdābād lake, when he preferred

sore complaints against 'Imādu-l Mulk Ghāzīu-d dīn Khān Bahādur, who was at

that time at Farrukh-ābād, engaged in exciting seditious tumults. The Shāh,

after forming a matrimonial alliance with the daughter of his late Majesty

Muhammad Shāh, and investing Najību-d daula with the title of Amīru-l

umarā and the dignified post of bakhshī, set out for Lāhore. As

soon as he had planted his sublime standard on that spot, he conferred both

the government of Lāhore and Multān on his son, Tīmūr Shāh, and leaving

Jahān Khān behind with him, proceeded himself to Kandahār.

Jahān Khān despatched a warrant to Adīna Beg Khān, who

at that time had taken up his residence at Lakhī Jangal, investing him with

the supreme control of the territory of the Doāb, along with a khil'at

of immense value, and adopted the most conciliatory measures towards him,

whereupon the latter, esteeming this amicable attention as a mark of good

fortune, applied himself zealously to the proper administration of the [S.

266] Doāb.

When Jahān Khān, however, summoned him to his presence, he did not consider

it to his advantage to wait upon him; so, quitting the territory of the Doāb, he retired into the hill-country. After this occurrence, Jahān Khān

appointed a person named Murād Khān to the charge of the Doāb, and sent

Sarbu-land Khān and Sarfarāz Khān, of the Abdālī tribe, along with him to

assist him. Adīna Beg Khān, having united the Sikh nation to his own forces,

advanced to give battle to Murād Khān, when Sarbuland Khān quaffed the cup

of martyrdom on the field of action, and Murād Khān and Sarfarāz Khān,

seeing no resource left them but flight, returned to Jahān Khān, and the

Sikhs ravaged all the districts of the Doāb.

As soon as active hostilities were commenced between

Najību-d daula and 'Imādu-l Mulk, the latter set out from Farrukhābād

towards Dehlī, to oppose the former, and forwarded letters to Bālājī Rāo and

his cousin Bhāo, soliciting aid, and inviting the Mahratta army to espouse

his cause. Bhāo, who was always cherishing plans in his head for the

national aggrandizement, counselled Bālājī Rāo to despatch an army for the

conquest of the territories of Hindūstān, which he affirmed to be then, as

it were, an assembly unworthy of reverence, and a rose devoid of thorns.

Memoir of Raghunāth Rāo.

In 1171 A.H. (1757-8 A.D.) Raghunāth Rāo, a brother of

Bālājī Rāo, accompanied by Malhār Rāo Holkar, Shamsher Bahādur, and Jayajī

Sindhia, started from the Dakhin towards Dehlī at the head of a gallant and

irresistible army, to subdue the dominions of Hindūstān. As soon as they

reached Āgra, they turned off to Shāh-Jahānābād in company with 'Imādu-l

Mulk, the wazīr, who was the instigator of the irruption made by this

torrent of destruction. After a sanguinary engagement, they ejected Najību-d

daula from the city of Dehlī, and consigned the management of the affairs of

government to the care of 'Imādu-l Mulk, the wazīr. [S.

267]

Raghunāth Rāo and the rest of the Mahratta chiefs set

out from Dehlī towards Lāhore, at the solicitation of Adīna Beg Khān, of

whom mention has been briefly made above. After leaving the suburbs of

Dehlī, they arrived first at Sirhind, where they fought an action with

'Abdu-s Samad Khān, who had been installed in the government of that place

by the Abdālī Shāh, and took him prisoner. Turning away from thence, they

pushed on to Lāhore, and got ready for a conflict with Jahān Khān, who was

stationed there. The latter, however, being alarmed at the paucity of his

troops in comparison with the multitude of the enemy, resolved at once to

seek safety in flight. Accordingly, in the month of Sha'bān, 1171 A.H.

(April, 1758 A.D.), he pursued the road to Kābul with the utmost speed,

accompanied by Tīmūr Shāh, and made a present to the enemy of the heavy

baggage and property that he had accumulated during his administration of

that region. The Mahratta chieftains followed in pursuit of Tīmūr Shāh as

far as the river [S. 268] Attock, and then retraced their steps to Lāhore. This time

the Mahrattas extended their sway up to Multān. As the rainy season had

commenced, they delivered over the province of Lāhore to Adīna Beg Khān, on

his promising to pay a tributary offering of seventy-five lacs of

rupees; and made up their minds to return to the Dakhin, being anxious to

behold again their beloved families at home.

On reaching Dehlī in the course of their return, they

made straight for their destination, after leaving one of their warlike

chieftains, named Jankū, at the head of a formidable army in the vicinity of

the metropolis. It chanced that in the year 1172 A.H. (1758-9 A.D.) Adīna

Beg Khān passed away; whereupon Jankūjī entrusted the government of the

province of Lāhore to a Mahratta, called Sāmā, whom he despatched thither.

He also appointed Sādik Beg Khān, one of Adīna Beg Khān's followers, to the

administration of Sirhind, and gave the management of the Doāb to Adīna Beg

Khān's widow. Sāmā, after reaching Lāhore, applied himself to the task of

government, and pushed on his troops as far as the river Attock. In the

meanwhile, 'Imādu-l Mulk, the wazīr, caused Shāh 'Ālamgīr II. to

suffer martyrdom, in retaliation for an ancient grudge, and placed the son

of Muhi'u-s Sunnat, son of Kām Bakhsh, son of Aurangzeb 'Ālamgīr, on the

throne of Dehlī.

Dattā Sindhia.

Dattā Sindhia, Jankūjī's uncle, about that time formed

the design of invading the kingdom of the Rohillas; whereupon Najību-d daula

and other Rohilla chiefs, becoming cognizant of this fact, and perceiving

the image of ultimate misfortune reflected in the mirror of the very

beginning, wrote numerous letters to the Abdālī Shāh, and used every

persuasion to induce him to come to Hindūstān. The Shāh, who was vexed at

heart on account of Tīmūr Shāh and Jahān Khān having been compelled to take

to flight, and was brooding over plans of revenge, accounted this friendly

overture a signal advantage, and set himself at once in motion.

Dattā, in company with his nephew Jankū, after

crossing the Jumna, advanced against Najību-d daula, and 'Imādu-l Mulk, the

wazīr, hastened to Dattā's support, agreeably to his request. As the

number of the Mahratta troops amounted to nearly 80,000 horse, Najību-d

daula, finding his strength inadequate to risk an open battle, threw up

intrenchments at Sakartāl, one of the places belonging to Antarbed (the Doāb),

situated on the bank of the river Ganges, and there held himself in

readiness to oppose the enemy. As the rainy season presented an

insurmountable obstacle to Dattā's movements, he was forced to suspend

military operations, and in the interim Najību-d daula despatched several

letters to Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula, begging his assistance.

The Nawāb, urged by the promptings of valour and

gallantry, started from Lucknow in the height of the rains, which fell with

greater violence than in ordinary years, and having with the utmost spirit

and resolution traversed the intervening roads, which were [S. 269] all in a wretched

muddy condition, made Shāhābād the site of his camp. Till the conclusion of

the rainy season, however, he was unable to unite with Najību-d daula, owing

to the overflowing of the river Ganges.

No sooner had the rains come to an end, than one of

the Mahratta chieftains, who bore the appellation of Gobind Pandit, forded

the stream at Dattā's command, with a party of 20,000 cavalry, and allowed

no portion of Chāndpūr and many other populous places to escape

conflagration and plunder. He then betook himself to the spot where

Sa'du-llah Khān, Dūndī Khān, and Hāfiz Rahmat Khān had assembled, after

having risen up in arms and quitted their abodes, to afford succour to

Najību-d daula. These three, finding themselves unable to cope with him,

took refuge in the forests on the Kamāūn hills.

Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula, being apprised of this

circumstance, mounted the fleet steed of resolution, and in Rabī'u-l awwal,

1173 A.H. (Oct. Nov. 1759 A.D.), taking his troops resembling the stars in

his train, he repaired on the wings of speed to Chāndpūr, close to the

locality where Najību-d daula was stationed. As Gobind Pandit had reduced

the latter's force as well as his companions to great straits, by cutting

off their supply of provisions, Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula Bahādur despatched

10,000 cavalry, consisting of Mughals and others, under the command of Mirzā

Najaf Khān Bahādur, Mīr Bākar Himmatī and other leaders, to attack the

Pandit's camp. He also afterwards sent off Anūpgar Gusāīn, and Rāj Indar

Gusāīn in rear of these. The leaders in question having fought with becoming

gallantry, and performed the most valiant deeds, succeeded in routing the

enemy. Out of the whole of Gobind Pandit's force, 200 were left weltering in

blood, and as many more were captured alive, whilst a vast number were

overwhelmed in the waters of the Ganges. Immense booty also fell into the

hands of the victors, comprising every description of valuable goods,

together with horses and cattle. Gobind Pandit, who after suffering this

total defeat had escaped from the field of battle across the river Ganges,

gave himself up to despair, [S. 270] and took to a precipitate flight. As soon as

this intelligence reached the ears of Hāfiz Rahmat Khān and the rest of the

Rohilla chieftains, they sallied forth from the forests of Kamāūn, and

repaired to Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula's camp. Meanwhile Najību-d daula was

released from the perils and misfortunes of his position.

Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula Bahādur assembled the Rohilla

chiefs, and offered them advice in the following strain: "The enemy has an

innumerable army, his military prowess is formidable, and he has gained

possession of most of the districts in your territory; it is therefore

better for you to make overtures for peace." Every one, both high and low,

applauded the Nawāb's judicious counsel, and voted that pacific negociations

should be immediately entered into with Dattā; but the truce had not yet

been established on a secure basis, when the news of Ahmad Shāh Abdālī's

approach, and of his arrival on this side of Lāhore, astonished the ears of

all. Dattā, with the arrogance that ever filled his head, would not allow

the preliminaries of peace to be brought to a conclusion; but haughtily

discarding the amicable relations that he was in process of contracting,

moved with a resolute step along the road to Dehlī, with a view to encounter

the Abdālī Shāh. He was accompanied at that time by 80,000 horsemen, well

armed and equipped.

When the Shāh set out from Lāhore in the direction of

Dehlī, he thought to himself that on the direct road between these two

places, owing to the passage to and fro of the Mahratta troops, it would be

difficult to find any thriving villages, and grain and forage would be

almost unprocurable. Consequently, in the month of Rabī'u-l awwal, 1173

A.H., he crossed the river Jumna, and entered Antarbed. Be it not unknown,

that Antarbed is the name given to the land lying between the Ganges and

Jumna, its frontier being Hardwār and the Kamāūn hills, which are situated

in the northern quarter of Hind. * *

In short, Ahmad Shāh Durrānī entered Antarbed, and

Najību-d daula and the other Rohilla chiefs, whose territories were situated

[S. 271] in that kingdom, came to join the Shāh. They likewise brought sums of money,

as well as grain and provisions, to whatever extent they could procure them,

and delivered them over for the Shāh's use. Through this cordial support of

the Rohilla chiefs, the Shāh acquired redoubled strength, and having

directed his corps of Durrānīs, who were employed in the campaign on

skirmishing duties, to pursue the ordinary route, and be in readiness for an

engagement with Dattā, proceeded himself to the eastward, by way of

Antarbed.

On this side too, Dattā, travelling with the speed of

wind and lightning, conducted his army to Sirhind, where he happened to

fall in with the Shāh's skirmishing parties. As the Durrānīs are decidedly

superior to the Mahratta troops in the rapidity of their evolutions, and in

their system of predatory warfare, the moment they confronted each other,

Dattā's army was unable to hold its ground. Being compelled to give way, he

retired to Dehlī, keeping up a running fight all the way, and took up a

position in the plain of Bāwalī, which lies in the vicinity of

Shah-Jahānābād. At that juncture, Jankūjī proposed to his nephew with

haughty pride, that they should try and extricate themselves from their

critical situation, and Jankūjī at once did exactly what his respected uncle

suggested. In fact, Dattā and his troops dismounted from their horses after

the manner of the inhabitants of Hind about to sacrifice their lives, and

boldly maintained their footing on the field of battle. The Durrānīs

assailed the enemy with arrows, matchlocks, and swords, and so overpowered

them as not to allow a single individual to escape in safety from the scene

of action. This event took place in Jumāda-l awwal, 1173 A.H. (Jan. 1760

A.D.).

Malhār Rāo Holkar.

As soon as this intelligence reached the quick ear of

Malhār Rāo Holkar, who at that time was staying at Makandara, he consigned

the surrounding districts to the flames, and making up [S. 272] his mind, proceeded

in extreme haste to Sūraj Mal Jāt, and importuned that Rāja to join him in

the war against the Durrānī Shāh. The latter, however, strongly objected to

comply with his request, stating that he was unable to advance out of his

own territory to engage in hostilities with them, as he had not sufficient

strength to risk a pitched battle; and that if the enemy were to make an

attack upon him, he would seek refuge within his forts. In the interview, it

came to Holkar's knowledge, that the Afghāns of Antarbed had moved out of

their villages with treasure and provisions, with intent to convey them to

the Shāh's camp, and had arrived as far as Sikandra, which is one of the

dependencies of Antarbed, situated at a distance of twenty kos from

Dehlī towards the east. He consequently pursued them with the utmost

celerity, and having fallen upon them, delivered them up to indiscriminate

plunder.

The Abdālī Shāh, having been apprised of this

circumstance, deputed Shāh Kalandar Khān and Shāh Pasand Khān Durrānī, at

the head of 15,000 horse, to chastise Holkar. The individuals in question,

having reached Dehlī from Nār-naul, a distance of seventy kos, in

twenty-four hours, and having halted during the day to recover from their

fatigues, effected a rapid passage across the Jumna, as soon as half the

night was over, and by using the utmost expedition, succeeded in reaching

Sikandra by sunrise. They then encompassed Holkar's army, and made a vast

number of his men fall a prey to their relentless swords. Holkar found

himself reduced to great straits; he had not even sufficient leisure to

fasten a saddle on his horse, but was compelled to mount with merely a

saddle-cloth under him, and flee for his life. Three hundred more horsemen

also followed after him in the same destitute plight, but the remainder of

his troops, being completely hemmed in, were either slain or captured, and

an immense quantity of property and household goods, as well as numbers of

horses, fell into the hands of the Durrānīs. About this time, too, the Shāh

arrived at Dehlī from Nārnaul, and took up his quarters in the city.

[S. 273]

Forces of the Dakhin.

In the year 1172 A.H. (1758-9 A.D.), Raghunāth Rāo,

the brother of Bālājī Rāo, after confiding the provinces of Lāhore and

Multān to Adīna Beg Khān, and leaving Jankūjī with a formidable army in the

vicinity of the metropolis of Dehlī, arrived at the city of Pūnā along with

Shamsher Bahādur, Malhār Rāo Holkar, and Jayājī Sindhiya. Sadāsheo Rāo

Bhāojī, who was Bālājī Rāo's cousin, and his chief agent and prime minister,

began instituting inquiries as to the receipts and disbursements made during

the invasion of Hind. As soon as it became apparent, that after spending the

revenue that had been levied from the country, and the proceeds arising from

the plundered booty, the pay of the soldiery, amounting to about sixty

lacs of rupees, was due; the vain illusion was dissipated from Bhāojī's

brain. The latter's dislike to Raghunāth Rāo, moreover, had now broken into

open contumely and discord, and Bālājī Rāo, vexed and disgusted at finding

his own brother despised and disparaged, sent a letter to Bhāojī, declaring

that it was essentially requisite for him now to unfurl the standard of

invasion in person against Hindūstān, and endure the fatigues of the

campaign, since he was so admirably fitted for the undertaking. Bhāo,

without positively refusing to consent to his wishes, managed to evade

compliance for a whole year, by having recourse to prevarication and

subterfuge.

Biswās Rāo, the son of Bālājī Rāo.

Biswās Rāo, Bālājī Rāo's eldest son, who was seventeen

years old, solicited the command of the army from his father; and though the

latter was in reality displeased with his request, yet in the year 1173 A.H.

(1759-60 A.D.) he sent him off with Bhāojī in company. Malhār Rāo, Pīlājī

Jādaun, Jān Rāo Dhamadsarī, Shamsher Bahādur, Sabūlī Dādājī Rāo, Jaswant Rāo

Bewār, Balwant Rāo, Ganesh Rāo, and other famous and warlike leaders, along

with a force of 35,000 cavalry, were also associated with Bhāo. Ibrāhīm Khān

Gārdī, who was the superintendent [S. 274] of the European artillery, likewise

accompanied him. Owing to the extreme sultriness of the hot season, they

were obliged to rest every other day, and thus by alternate marches and

halts, they at length reached Gwālior.

As soon as the story of 'Imādu-l Mulk and Jankūjī

Sindhia's having sought refuge in the forts belonging to Sūraj Mal Jāt, and

the particulars of Dattā's death and Holkar's defeat, as well as the rout

and spoliation of both their forces, were poured into the ears of Biswās Rāo

and Bhāojī by the reporters of news and the detailers of intelligence, vast

excitement arose, so that a sojourn of two months took place at Gwālior.

Malhār Rāo Holkar, who had escaped with his life from the battle with the

Durrānīs, and in the mean time had joined Biswās Rāo's camp, then started

from Gwālior for Shāh-Jahānābād by Bhāo's order, at the head of a formidable

army, and having reached Āgra, took Jankūjī Sindhia along with him from

thence, and drew near to his destination.

Ahmad Shāh Abdālī, on ascertaining this news, sallied

out from the city of Dehlī to encounter him; but the latter, finding himself

unable to resist, merely made some dashing excursions to the right and left

for a few days, after the guerilla fashion. As the Shāh, however, would

never once refrain from pursuing him, he was ultimately forced to make an

ignominious retreat back along the road he had come, and having returned to

Gwālior, went and rejoined Bhāojī. The rainy season was coming on, * *

so Ahmad Shāh crossed the river Jumna, and having encamped at Sikandra, gave

instructions to the officers of his army, to prepare houses of wood and

grass for themselves, in place of tents and pavilions.

Bhāo and Biswās Rāo, having marched from Gwālior,

after travelling many stages, and traversing long distances, as soon as they

reached Akbarābād; Holkar and Jankūjī, at Bhāo's instigation, betook

themselves to Rāja Sūraj Mal Jāt, and brought him along with them to have an

interview with Bhāo. The latter went out a kos from camp to meet him,

and 'Imādu-l [S. 275] Mulk, the wazīr, also held a conference with Bhāo

through Sūraj Mal's mediation. Sūraj Mal proposed that the campaign should

be conducted on the following plan, viz. that they should deposit their

extra baggage and heavy guns, together with their female relatives, in the

fort of Jhānsī, by the side of the river Chambal; and then proceed to wage a

predatory and desultory style of warfare against the enemy, as is the usual

practice of the Mahratta troops; for under these circumstances their own

territory would be behind their backs, and a constant supply of provisions

would not fail to reach their camp in safety. Bhāo and the other leaders,

after hearing Sūraj Mal's observations, approved of his decision; but Biswās

Rāo, who was an inexperienced youth, intoxicated with the wine of arrogance,

would not follow his advice. Bhāo accordingly carried on operations in

conformity with Biswās Rāo's directions, and set out from Akbarābād towards

Dehlī with the force that he had at his disposal. On Tuesday, the 9th of Zī-l hijja, 1173 A.H. (23 Sept. 1760 A.D.), about the time of rising of the

world-illumining sun, he enjoyed the felicity of beholding the fort of

Dehlī. The command of the garrison there was at that time entrusted to Ya'kūb 'Alī Khān Bahmanzāi, brother to Shāh Walī Khān, the prime minister of

the Durrānī Shāh; who, in spite of the multitude of his enemies, would not

succumb, and spared no exertions to protect the fort with the few martial

spirits that he had with him.

Capture of the fort of Dehlī.

Bhāo, conjecturing that the fort of Dehlī would be

devoid of the protection of any garrison, and would therefore, immediately

on being besieged, fall under his subjection, went and took up a position

near Sa'du-llah Khān's mansion, with a multitude of troops. * *

Ibrāhīm Khān Gārdī, who was a confederate of Bhāo, and had the

superintendence of the European artillery, planted his thundering cannon,

with their skilful gunners, [S. 276] opposite the fort on the side of the sandy plain,

and having made the battlements of the Octagon Tower and the Asad Burj a

mark for his lightning-darting guns, overturned many of the royal edifices.

Every day the tumultuous noise of attack on all sides of the fort filled the

minds of the garrison with alarm and apprehension. The overflowing of the

Jumna presented an insurmountable obstacle to the crossing of the Durrānī

Shāh's army, and hindered it from affording any succour to the besieged. The

provisions in the fort were very nearly expended, and Ya'kūb 'Alī Khān was

forced to enter into negociations for peace. He first removed, with his

female relatives and property, from the fort to the domicile of 'Alī Mardān

Khān, and then, having crossed the river Jumna from thence on board a boat,

betook himself to the Shāh's camp. On the 19th of the aforesaid month and

year, Bhāo entered the fort along with Biswās Rāo, and took possession of

all the property and goods that he could find in the old repositories of the

royal family. He also broke in pieces the silver ceiling of the Dīuān-i

Khāss, from which he extracted so much of the precious metal as to be

able to coin seventeen lacs of rupees out of it. Nārad Shankar

Brahmin was then appointed by Bhāo to the post of governor of the fort.

The Durrānī Shāh, after his engagement with Dattā,

which terminated in the destruction of the latter, had despatched Najību-d

daula to the province of Oudh with a conciliatory epistle, which was as it

were a treaty of friendship, for the purpose of fetching Nawāb Shujā'u-d

daula Bahādur. Najību-d daula accordingly betook himself by way of Etāwa to

Kanauj; and about the same time Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula marched from Lucknow,

and made the ferry of Mahdipūr, which is one of the places in Etāwa situated

on this side the river Ganges, the site of his camp. An interview took place

in that locality, and as soon as the friendly document had been perused, and

the Nawāb's heart had been comforted by its sincere promises, he came to the

fixed determination of waiting on the Shāh, and he sent back Rāja Benī

Bahādur, who at that time possessed greater power and [S. 277] influence than his

other followers, to rule as viceroy over the kingdom during his absence.

When Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula approached the Shāh's army, the prime minister,

Shāh Walī Khān, hastened out to meet him, and, having brought him along with

him in the most courteous and respectful manner, afforded him the

gratification, on the 4th of Zī-l hijja, 1173 A.H. (18th July, 1760 A.D.),

of paying his respects to the Shāh, and of folding the son of the latter,

Tīmūr Shāh, in his embrace.

Bhāo remained some time in the fort of Shāh-Jahānābād,

in consequence of the rainy season, which prevented the horses from stirring

a foot, and deprived the cavalry of the power of fighting; he sent a person

named Bhawānī Shankar Pandit to Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula, with the following

message: "If it is inconvenient for you to contract an alliance with your

friends, you should at least keep aloof from the enemy, and remain perfectly

neutral to both parties." The above-named Pandit, having crossed the river

Jumna, went to Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula Bahādur, and delivered this message.

The latter, after ascertaining its drift, despatched his eunuch Yākūt Khān,

who was one of the oldest and most confidential servants of his government,

in company with Bhawānī Shankar Pandit, and returned an answer of this

description: "As the Rājas of this empire and the Rohilla chiefs were

reduced to the last extremity by the violent aggressions of Raghunāth Rāo,

Dattā, Holkar, and their subordinates, they solicited the Abdālī Shāh to

come to Hindūstān, with the view of saving themselves from ruin. ‘The seed

that they sowed has now begun to bear fruit.’ Nevertheless, if peace be

agreeable to you, from true regard for our ancient friendship, my best

endeavours shall be used towards concluding one." Eventually, Bhāo proposed

that as far as Sirhind should be under the Shāh's dominion, and all on this

side of it should belong to him; but the whole rainy season was spent in

negocia-tion, and no peace was established.

In the interim, Rāja Sūraj Mal Jāt, who discerned the

speedy downfall of the Mahratta power, having moved with his troops, [S.

278] in

company with 'Imādu-l Mulk, the wazīr, from his position at Sarai

Badarpūr, which is situated at a distance of six kos from Dehlī on

the eastern side, and traversed fifty kos in one night, without

informing Bhāo betook himself to Balamgarh,

which is one of his forts.

As the Mahratta troops made repeated complaints to

Bhāo regarding the scarcity of grain and forage, the latter, on the 29th of

the month of Safar, 1174 A.H. (9th October, 1760 A.D.), removed Shāh Jahān,

son of Muhi'u-s Sunnat, son of Kām Bakhsh, son of Aurangzeb 'Ālamgīr, and

having seated the illustrious Prince, Mirzā Jawān Bakht, the grandson of

'Ālamgīr II., on the throne of Dehlī, publicly conferred the dignity of

wazīr on Shujā'u-d daula. His object was this, that the Durrānī Shāh

might become averse to and suspicious of the Nawāb in question. Leaving

Nārad Shankar Brahmin, of whom mention has been made above, behind in the

fort of Shāh-Jahānābād, he himself set out, with all his partisans and

retainers, in the direction of Kunjpūra.

This place is fifty-four kos to the west of Dehlī, and seven to the

north of the pargana of Karnāl, and it is a district the original

cultivators of which were the Rohillas.

Capture of the fort of Kunjpūra.

Bhāo, on the 10th of Rabī'u-l awwal, 1174 A.H. (19th

October, 1760), encompassed the fort of Kunjpūra with his troops, and

subdued it in the twinkling of an eye by the fire of his thundering cannon.

Several chiefs were in the fort, one of whom was 'Abdu-s Samad Khān Abdālī,

governor of Sirhind, who had been taken prisoner by Raghunāth Rāo in 1170

A.H. (1756-7), but had ultimately obtained his release, as was related in

the narrative of Adīna Beg Khān's proceedings. There were, besides, Kutb

Khān Rohilla, Dalīl Khān, and Nijābat Khān, all zamīndārs of places

[S. 279] in Antarbed, who had been guilty of conveying supplies to the Abdālī Shāh's

camp. After reducing the fort, Bhāo made 'Abdu-s Samad Khān and Kutb Khān

undergo capital punishment, and kept the rest in confinement; whilst he

allowed Kunjpūra itself to be sacked by his predatory hordes.

As soon as this intelligence reached the Shāh's ear,

the sea of his wrath was deeply agitated; and notwithstanding that the

stream of the Jumna had not yet subsided sufficiently to admit of its being

forded, a royal edict was promulgated, directing his troops to pay no regard

to the current, but cross at once from one bank to the other. As there was

no help but to comply with this mandate, on the 16th of the month of

Rabī'u-l awwal, 1174 A.H. (25th October, 1760 A.D.), near Shāh-Jahānābād, on

the road to Pākpat, which is situated fifteen kos to the north of

Dehlī, they resigned themselves to fate, and succeeded in crossing. A

number were swallowed up by the waves, and a small portion of the baggage

and quadrupeds belonging to the army was lost in the passage. As soon as the

intelligence reached Bhāo's ear, that a party of Durrānīs had crossed,

* * he sounded the drum of retreat from Kunjpūra, and with his force

of 40,000 well-mounted and veteran cavalry, and a powerful train of European

artillery, under the superintendence of Ibrāhīm Khān Gārdī, he repaired

expeditiously to Pānīpat, which lies forty kos from Dehlī towards the

west.

Battle between the Mahratta Army and the Durrānīs.

The Abdālī Shāh, after crossing the river Jumna at the

ghāt of Pākpat, proceeded in a westerly direction, and commanded that

Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula Bahādur and Najību-d daula should pitch their tents on

the left of the royal army, and Dūndī Khān, Hāfizu-l Mulk Hāfiz Rahmat Khān,

and Ahmad Khān Bangash on the right. As Bhāo perceived that it was difficult

to contend against the Durrānīs in the open field, by the advice of his

counsellors he made a permanent encampment of his troops in the outskirts of

the city of Pānīpat, and having intrenched [S. 280] it all round with his artillery,

took up his quarters in this formidable position. * *

In the interim Gobind Pandit, who was the tahsīldār

of the district of Shukohābād, etc., betook himself to Dehlī at Bhāo's

suggestion, with a body of 10,000 cavalry, and intercepted the transport of

supplies to the Durrānī Shāh's army.

* *

When the basis of the enemy's power had been

overthrown (at Pānīpat), and the surface of the plain had been relieved of

the insolent foe, the triumphant champions of the victorious army proceeded

eagerly to pillage the Mahratta camp, and succeeded in gaining possession of

an unlimited quantity of silver and jewels, 500 enormous elephants, 50,000

horses, 1000 camels, and two lacs of bullocks, with a vast amount of

goods and chattels, and a countless assortment of camp equipage. Nearly

30,000 labourers too, who drew their origin from the Dakhin, fell into

captivity. Towards evening the Abdālī Shāh went out to look at the bodies of

the slain, and found great heaps of corpses, and running streams produced by

the flood of gore. * * Thirty-two mounds of slain were counted,

and the ditch, protected by artillery, of such immense length that it could

contain several lacs of human beings, besides cattle and baggage, was

completely filled with dead bodies.

Assassination of Sindhia Jankūjī.

Rāo Kāshī Nāth, on seeing Jankūjī, who was a youth of

twenty, with a handsome countenance, and at that time had his wounded hand

hanging in a sling from his neck, became deeply grieved, and the tears

started from his eyes. * * Jankūjī raised his head and exclaimed:

"It is better to die with one's friends than to live among one's enemies."

The Nawāb, in unison with Shāh Walī Khān, solicited

the Shāh to spare Jankūjī's life; whereupon, the Shāh summoned Barkhūrdār

Khān, and consulted him on the propriety of the [S. 281] step, to which the Khān in

question returned a decided negative. At the same time, one of the Durrānīs,

at Barkhūrdār Khān's suggestion, went and cut Jankūjī's throat, and buried

him under ground inside the very tent in which he was imprisoned.

Ibrāhīm Khān Gārdī's Death.

Shujā'u Kulī Khān, a powerful and influential servant

of the Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula Bahādur, having captured Ibrāhīm Khān Gārdī on

the field of battle, kept him with the said Nawāb's cognizance in his own

tent. No sooner did this intelligence become public, than the Durrānīs

began in a body to raise a violent tumult, and clamorously congregating

round the door of the Shāh's tent, declared that Ibrāhīm Gārdī's neck was

answerable for the loss of so many thousands of their fellow-countrymen, and

that whoever sought to protect him would incur the penalty of their

resentment. Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula, feeling that one seeking refuge cannot

be slain, prepared for a contest with the Durrānī forces, whereupon there

ensued a frightful disturbance. At length, Shāh Walī Khān took Nawāb

Shujā'u-d daula aside privately, and addressing him in a friendly and

affectionate tone, proposed, that he should deliver up Ibrāhīm Khān Gārdī to

him, for the sake of appeasing the wrath of the Durrānīs; and after a week,

when their evil passions had been allayed, he would restore to him the

individual entrusted to his care. In short, Ashrafu-l Wuzrā (Shāh Walī

Khān), having obtained him from the Nawāb, applied a poisonous plaister to

his wounds; so that, by the expiration of a week, his career was brought to

a close.

Discovery of Bhāojī's Corpse.

The termination of Bhāojī's career has been

differently related. Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula, having mounted after the

victory, took Shishā Dhar Pandit, Ganesh Pandit, and other associates of

Bhāojī along with him, and began wandering over the field of battle,

searching for the corpses of the Mahratta chiefs, and more [S. 282] especially for Bhāojī's dead body. They accordingly recognized the persons of Jaswant Rāo

Balwār, Pīlājī, and Sabhājī Nāth who had received forty sword-cuts, lying on

the scene of action; and, in like manner, those of other famous characters

also came in view. Bhāo's corpse had not been found, when from beneath a

dead body three valuable gems unexpectedly shone forth. The Nawāb presented

those pearls to the Pandits mentioned above, and directed them to try and

recognize that lifeless form. They succeeded in doing so through the scar of

a gunshot wound in the foot, and another on the side behind the back, which

Bhāo had received in former days. With their eyes bathed in tears they

exclaimed: "This is Bhāo, the ruler of the Dakhin."

Some entertain an opinion, that Bhāo, after Biswās Rāo's death, performed

prodigies of valour, and then disappeared from sight, and no one ever saw

him afterwards. Two individuals consequently, both natives of the Dakhin,

have publicly assumed the name of Bhāo, and dragged a number of people into

their deceitful snare. As a falsehood cannot bear the light, one was

eventually put to death somewhere in the Dakhin by order of the chiefs in

that quarter; and the other, having excited an insurrection at Benares, was

confined for some time in the fort of Chunār. After his release, despairing

of the success of his project, he died in the suburbs of Gorakhpūr in the

year 1193 A.H.

Nawāb Shujā'u-d daula Bahādur, having obtained

permission of the Shāh to burn the bodies [of the Bhāo and other chiefs],

deputed Rāja Himmat Bahādur and Rāo Kāshī Nāth, his principal attendants, to

perform the task of cremation. Out of all those hapless and unfortunate

beings [who survived the battle], a number maintained a precarious

existence against the violent assaults of death for some days; but

notwithstanding that they used the most strenuous exertions to effect their

escape in divers directions from Pānīpat, not a single one was saved from

being slain and plundered by the zamīndārs of that quarter. Out of

the whole of the celebrated chiefs too, with the exception of [S. 283] Malhār Rāo

Holkar, 'Appājī Gaikawār and Bithal Sudeo, not another was ever able to

reach the Dakhin.

Account of Bhāojī's Wife.

Bhāo's wife, in company with Shamsher Bahādur,

half-brother

to Bālājī Rāo, and a party of confidential attendants, traversed a long

distance with the utmost celerity, and betook herself to the fortress of

Dīg. There that broken-hearted lady remained for two or three days mourning

the loss of her husband, and having then made up her mind to prepare for an

expedition to the Dakhin, Rāja Sūraj Mal Jāt gave her one morning a suitable

escort to attend her, and bade her adieu. She accordingly reached the

Dakhin; but Shamsher Bahādur, who was severely wounded, died after arriving

at Dīg.

Death of Bālājī.

Shortly before the occurrence of these disasters,

Bālājī Rāo had marched from Pūnā. He had only proceeded as far as Bhīlsa,

when, having been informed of the event, he grew tired of existence, and

shed tears of blood lamenting the loss of a son and a brother. He then moved

from where he was to Sironj, and about that very time a messenger reached

him from the Abdālī Shāh, with a mourning khil'at. The Rāo, feigning

obedience to his commands, humbly dressed his person in the Shāh's

khil'at, and turning away from Sironj, re-entered Pūnā. From excess of

grief and woe, however, he remained for two months afflicted with a

harrowing disease; and as he perceived the image of death reflected from the

mirror of his condition, he sent for his brother, Raghunāth Rāo, to whom he

gave in charge his best beloved son, the younger brother of the lately slain

Biswās Rāo, who bore the name of Mādhū Rāo, and had just entered his twelfth

year, exclaiming: "Fulfil all the duties of [S. 284] goodwill towards this fatherless

child, treating him as if he were your own son, and do not permit any harm

to come upon him." Having said this, he departed from the world on the 9th

of Zī-l ka'da, 1174 A.H. (14th June, 1761 A.D.), and the period of his reign

was twenty-one years.

Mādhū Rāo, son of Bālājī.

Mādhū Rāo, after the demise of his father, was

installed in the throne of sovereignty at Pūnā; and Raghunāth Rāo conducted

the administration of affairs as prime minister, after the manner of the

late Bhāo.

Account of the pretender Bhāo.

One of the remarkable incidents that occurred in Mādhū

Rāo's reign was the appearance of a counterfeit Bhāo, who, in the year 1175

A.H. (1762-3 A.D.), having induced a number of refractory characters to

flock to his standard, and having collected together a small amount of

baggage and effects, with camp equipage and cattle, excited an insurrection

near the fort of Karāza, which is situated at a distance of twelve kos

from Jhānsī towards the west. He gave intimation to the governor of the

fort, who held his appointment of the Pūnā chiefs, as to his name and

pretensions, and summoned him by threats and promises into his presence. The

latter, who, up to that time, had been in doubt whether Bhāo was dead or

alive, being apprehensive lest this individual should in reality prove to be

Bhāo, proceeded to wait upon him, and presented some cash and valuables by

way of offering. After that, the Bhāo in question sent letters into other

parganas, and having summoned the revenue officers from all quarters,

commenced seizing and appropriating all the cash, property and goods.

Whatever horses, elephants, or camels he found with any one, he immediately

sent for, and kept in his own possession.

This pretender to the name of Bhāo always kept his

face [S. 285] half covered under a veil, both in public and private, on the plea that

the wound on his visage was still unhealed, and people were completely

deceived by the stratagem; no one could have the impudence to scrutinize his

features. In short, for six months he persevered in his imposture, until the

news reached Pūnā, when some spies went over to him to examine strictly into

the case, and discovered that he was not Bhāo.

About the same period, Malhār Rāo Holkar was moving

from the Dakhin towards Hindūstān, and his road happened to lie through the

spot where the pretender in question had pitched his tents. The

above-mentioned spies disclosed the particulars of the case to Malhār Rāo,

who thought to himself, that until Pārbatī Bāi, the late Bhāo's wife, had

seen this individual with her own eyes, and all her doubts had been removed,

it would not do to inflict capital punishment on the impostor, for fear the

lady should think in her heart that he had killed her husband out of spite

and malice. For this reason, Malhār Rāo merely took the impostor prisoner,

and having appointed thirty or forty horsemen to take care of him, forwarded

him from thence to Pūnā. The few weak-minded beings, who had gathered round

him, were allowed to depart to their several homes, and Holkar proceeded to

his destination. When the pretender was brought to Pūnā, Mādhū Rāo likewise,

out of regard for the feelings of the late Bhāo's wife, deemed it proper to

defer his execution, and kept him confined in one of the forts within his

own dominions. Strange to say, the silly people in that fort did not

discover the falseness of the impostor's claims, and leagued themselves with

him, so that a fresh riot was very nearly being set on foot. Mādhū Rāo,

however, having been apprised of the circumstances, despatched him from

that fort to another stronghold; and in the same way his removal and

transfer was constantly taking place from various forts in succession, till

he was finally confined in a stronghold, that lies contiguous to the sea on

the island of Kolāba, which is a dependency of the Kokan territory. [S.

286]

Nawāb Nizām 'Alī Khān Bahādur.

The following is another of the events of Mādhū Rāo's

reign: Bithal, dīwān of Nawāb Nizām 'Alī Khān Bahādur, advised his

master, that as the Mahrattas were then devoid of influence, and the

supreme authority was vested in an inexperienced child, it would be

advisable to ravage Pūnā. Jānūjī Bhonsla Rāja of Nāgpūr, Gopāl Rāo a servant

of the Peshwa, and some more chiefs of the Mahratta nation, approved of the

dīwān's suggestion, and led their forces in a compact mass towards

Pūnā. When they drew near its frontier, Raghunāth Rāo, who was Mādhū Rāo's

chief agent and prime minister, got terrified at the enemy's numbers, and

finding himself incompetent to cope with them, retired with his master from

Pūnā. Nawāb Nizām 'Alī Khān Bahādur then entered the city, and did not spare

any efforts in completing its destruction.

After some time, Raghunāth Rāo recovered himself, and

having entered into friendly communication with Jānūjī Bhonsla and the other

chiefs of his own tribe, by opening an epistolary correspondence with them,

he alienated the minds of these men from the Nawāb. In short, the

above-named chiefs separated from the Nawāb on the pretence of its being the

rainy season, and returned to their own territories. In the interim,

Raghunāth Rāo and Mādhū Rāo set out to engage Nawāb Nizām 'Alī Khān

Bahā-dur, who, deeming it expedient to proceed to his original quarters,

beat a retreat from the position he was occupying. When the bank of the

river Godāverī became the site of his encampment, an order was issued for

the troops to cross over. Half the matériel of the army was still on

this side, and half on that; when Raghunāth, considering it a favourable

opportunity, commenced a furious onslaught. The six remaining chiefs of the

Nawāb's army were slain, and about 7000 Afghāns, etc., acquired eternal

renown by gallantly sacrificing their lives. After this sanguinary conflict,

the Nawāb hastily crossed the river, and extricated himself from his

perilous position. As soon as the flame of strife had been [S. 287] extinguished, a

peace was established through the intervention of Malhār Rāo Holkar, who had

escaped with his life in safety from the battle with Abdālī Shāh. Both

parties concurring in the advantages of an amicable understanding, returned

to their respective quarters.

Quarrel between Raghunāth Rāo and Mādhū Rāo.

When Raghunāth Rāo began to usurp greater authority

over the administration of affairs; Gopikā Bāi, Mādhū Rāo's mother, growing

envious of his influence, inspired her son with evil suspicions against him,

and planned several stratagems, whereby their mutual friendship might result

in hatred and animosity, till at length Raghunāth Rāo became convinced that

he would some day be imprisoned. Consequently, he mounted his horse one

night, and fled precipitately from Pūnā with only a few adherents. Stopping

at Nāsik, which lies at a distance of eight stages from Pūnā, he fixed upon

that town as his place of refuge and abode, and employed himself in

collecting troops; insomuch that Nāradjī Sankar, the revenue collector of

Jhānsī, Jaswant Rāo Lūd, Sakhā Rām Bāpū and Nīlkanth Mahādeo, volunteered to

join him, and eagerly engaged in active hostilities against Mādhū Rāo. As

soon as Raghunāth Rāo arrived in this condition close to Pūnā, Mādhū Rāo was

also obliged to sally forth from it in company with Trimbak Rāo, Bāpūjī

Mānik, Gopāl Rāo and Bhīmjī Lamdī. When the line of battle began to be

formed, Raghunāth Rāo assumed the initiative in attacking his adversaries,

and succeeded in routing Mādhū Rāo's force by a series of overwhelming

assaults; and even captured the Rāo himself, together with Nar Singh Rāo.

After gaining this agreeable victory, as he perceived Mādhū Rāo to be in

safety, and his malicious antagonists overthrown, he could not contain

himself for joy. As soon as he returned from the battle-field to his

encampment, he seated Mādhū Rāo on a throne, and remained himself standing

in front of him, after the manner of slaves. By fawning and coaxing, [S.

288] he then

removed every trace of annoyance from Mādhū Rāo's mind, and requested him to

return to Pūnā. After dismissing him to that city, he himself went with his

retinue and soldiery to Nāsik.

Haidar Nāik.

After the lapse of some years of Mādhū Rāo's reign, a

vast disturbance arose in the Dakhin. Haidar Nāik having assembled some bold

and ferocious troops, * * with intent to subdue the territory of

the Mahrattas, set out in the direction of Pūnā. Mādhū Rāo came out from

Pūnā, and summoned Raghunāth Rāo to his assistance from Nāsik, whereupon the

latter joined him with a body of 20,000 of his cavalry. In short, they

marched with their combined forces against the enemy; and on several

occasions encounters took place, in which the lives of vast multitudes were

destroyed. Although Haidar Nāik's army proved themselves superior in the

field, yet peace was ultimately concluded on the cession and surrender of

some few tracts in the royal dominions; after which Haidar Nāik refrained

from hostilities, and returned to his own territory; whilst Mādhū Rāo

retired to Pūnā, and Raghunāth Rāo to Nāsik.

Raghunāth Rāo's movements.

When a short time had elapsed after this, the idea of

organizing the affairs of Hindūstān entered into Raghunāth Rāo's mind. For

the sake of preserving outward propriety, therefore, he first gave

intimation to Mādhū Rāo of his intention, and asked his sanction. The Rāo in

question, who did not feel himself secure from Raghunāth Rāo, and

considered any increase to his power a source of greater weakness to

himself, addressed him a reply couched in these terms: "It were better for

you to remain where you are, in the enjoyment of repose." * *

Raghunāth Rāo would not listen to these words, but marched out of Nāsik in

company with Mahājī Sindhia, taking three powerful armies along with him.

[S. 289]

As soon as he reached Gwālior, he commenced

hostilities against Rānā Chattar Singh, who possessed all the country round

Gohad, and laid siege to the town itself. Godh is the name of a city,

founded by the aforesaid Rānā. It is fortified with earthen towers and

battlements, and is situated eighteen kos from Gwālior. Mādhū Rāo,

during the continuance of the siege, kept constantly sending messages to

Rānā Chattar Singh, telling him to persist in his opposition to Raghunāth

with a stout heart, as the army of the Dakhin should not be despatched to

his kingdom to reinforce the latter. In a word, for the period of a year

they used the most arduous endeavours to capture Gohad, but failed in

attaining their object. During this campaign, the sum of thirty-two lacs

of rupees, taken from the pay of the troops and the purses of the wealthy

bankers, was incurred by Raghunāth Rāo as a debt to be duly repaid. He then

returned to the Dakhin distressed and overwhelmed with shame, and entered

the city of Nāsik, whither Mādhū Rāo also repaired about the same time, to

see and inquire after his fortunes. In the course of the interview, he

expressed the deepest regret for the toils and disappointment that the Rāo

had endured, and ultimately returned in haste to Pūnā, after thus sprinkling

salt on the galling wound. Shortly after this, Kankumā Tāntiā and his other

friends persuaded Raghunāth Rāo to adopt a Brahmin's son. * *

Accordingly the Rāo attended to the advice of his foolish counsellors, and

selected an individual for adoption. He constituted Amrat Rāo his heir.

Raghunāth Rāo's imprisonment at Pūnā.

Mādhū Rāo no sooner became cognizant of this fact,

than he felt certain that Raghunāth Rāo was meditating mischief and

rebellion, and seeking to usurp a share in the sovereignty of the realm. He

consequently set out for Nāsik with a force of 25,000 horsemen, whilst, on

the other hand, Raghunāth Rāo also organized his troops, and got ready for

warfare. Just about that [S. 290] period, however, Kankumā Tāntiā and Takūjī Holkar,

who were two of the most powerful and influential men in Raghunāth's army,

declared to him that it was necessary for them to respect their former

obligations to Mādhū Rāo, and therefore improper to draw the sword upon him.

After a long altercation, they left the Rāo where he was, and departed from

Nāsik. Raghunāth, from the paucity of his troops, not deeming it

advantageous to fight, preferred enduring disgrace, and fled with 2000

adherents to the fort of Dhūdhat.

Mādhū Rāo then entered Nāsik, and commenced

sequestrating his property and imprisoning his partisans; after which he

pitched his camp at the foot of the above-named fort, and placed Raghunāth

in a most precarious position. For two or three days the incessant discharge

of artillery and musketry caused the flames of war to blaze high, but

pacific negocia-tions were subsequently opened, and a firm treaty of

friendship entered into, whereupon the said Rāo came down from the fort,

and had an interview with Mādhū Rāo. The latter then placed his head upon

the other's feet, and asked pardon for his offences. Next day, having

mounted Raghunāth Rāo on his own private elephant, he himself occupied the

seat usually assigned to the attendants, and continued for several days

travelling in this fashion the distance to Pūnā. As soon as they entered

Pūnā, Mādhū Rāo, imitating the behaviour of an inferior to a superior,

exceeded all bounds in his kind and consoling attentions towards Raghunāth

Rāo. After that he selected a small quantity of goods and a moderate

equipment of horses and elephants, out of his own establishment, and having

deposited them all together in one of the most lofty and spacious

apartments, solicited Raghunāth Rāo in a respectful manner to take up his

abode there. The latter then became aware of his being a prisoner with the

semblance of freedom, and reluctantly complied with Mādhū Rāo's requisition.

[S. 291]

Rāja of Nāgpūr.

As soon as Mādhū Rāo had delivered his mind from all

apprehension regarding Raghunāth Rāo, he led his army in the direction of

Nāgpūr, in order to avenge himself on Jānūjī Bhonsla, the Rāja of that

place, who had been an ally and auxiliary of Raghunāth Rāo, in one of his

engagements. The Rāja in question, not finding himself capable of resisting

him, fled from his original residence; so that for a period of three months

Mādhū Rāo was actively engaged in pursuing his adversary, and that

unfortunate outcast from his native land was constantly fleeing before him.

Ultimately, having presented an offering of fifteen lacs of rupees,

he drew back his foot from the path of flight, and set out in safety and

security for his own home.

Mādhū Rāo's Death.

After chastising the Rāja of Nāgpūr, Mādhū Rāo entered

Pūnā with immense pomp and splendour, and amused himself with gay and

festive entertainments. But he was attacked with a fatal disease, and *

* his life was in danger. On one occasion he laid his head on

Raghunāth Rāo's feet, and * * asked forgiveness for the faults

of bygone days. Raghunāth Rāo grieved deeply on account of his youth. *

* He applied himself zealously to the cure of the invalid, and

whenever he found a trace, in any quarter or direction, of austere Brahmins

and skilful Pandits, he sent for them to administer medicines for his

recovery. At length, when the sick man began to despair of living, he

imitated the example of his deceased father, and placed his younger brother,

whose name was Narāin Rāo, under the charge of Raghunāth Rāo, and having

performed the duty of recommending him to his care, yielded up his soul in

the year 1186 A.H. (1772 A.D.). The duration of his reign was twelve years.

[S. 292]

Narāin Rāo, son of Bālājī Rāo.

Narāin Rāo, after being seated on the throne of

sovereignty, owing to his tender age, committed various acts that produced

an ill-feeling among his adherents, both great and small, at Pūnā; more

especially in Raghunāth Rāo, on whom he inflicted unbecoming indignities.

Although Mādhū Rāo had not behaved towards his uncle with the respect due to

such a relative, yet, beyond this much, that he would not grant him

permission to move away from Pūnā, he had treated him with no other

incivility; but used always, till the day of his death, to show him the

attention due from an inferior to a superior; and supplied him with wealth

and property far exceeding the limits of his wants. In short, Raghunāth Rāo,

having begun to form plans for taking Narāin Rāo prisoner, first disclosed

his secret to Sakhā Rām Bāpū, who was Mādhū Rāo's prime minister, and having

seduced that artless courtier from his allegiance, made him an accomplice in

his treacherous designs. Secondly, having induced Kharak Singh and Shamsher

Singh, the chiefs of the body of Gārdīs, to join his conspiracy, he raised

the standard of insurrection. Accordingly, those two faithless wretches one

day, under the pretence of demanding pay for the troops, made an assault on

the door of Narāin Rāo's apartment, and reduced him to great distress. That

helpless being, who had not the slightest cognizance of the deceitful

stratagems of the conspirators, despatched a few simple-minded adherents to

oppose the insurgents, and then stealthily repaired to Raghunāth Rāo's

house. Kharak Singh and Shamsher Singh, being apprised of the circumstance,

hurried after him, and, unsheathing their swords, rushed into Raghunāth

Rāo's domicile. Raghunāth Rāo first fell wounded in the affray, and

subsequently Narāin Rāo was slain. This event took place in the year 1187

A.H., so that the period of Narāin Rāo's reign was one year. [S.

293]

Reign of Raghunāth Rāo.

Kharak Singh and Shamsher Singh, through whose brains

the fumes of arrogance had spread, in consequence of their control over the

whole train of European artillery, with wilful and headstrong insolence

seated Raghunāth Rāo on the throne of sovereignty, without the concurrence

of the other chiefs; and the said Rāo continued to live for two months at

Pūnā after the manner of rightful rulers. After Narāin Rāo had been put to

death, a certain degree of shame and remorse came over the Pūnā chiefs, and

the dread of their own overthrow entered their minds. Sakhā Rām Bāpū

consequently, in unison with Trimbak Rāo, commonly called Mātamādharī

Balhah,

and others, deemed it advisable to persuade Raghunāth Rāo that he should go

forth from Pūnā, and employ himself in settling the kingdom. The said Rāo

accordingly acted upon their suggestion, and marched out of Pūnā, attended

by the Mahratta chiefs. As soon as he had got to the distance of two or

three stages from the city, the wily chiefs, by alleging some excuse,

obtained leave from Raghunāth Rāo to return, and repaired from the camp to

the city. They then summoned to them in private all the commanders of the

army, both great and small; when they came to the unanimous decision, that

it was incompatible with justice to acquiesce in Raghunāth Rāo's being

invested with the supreme authority, and that it would be better, as Narāin

Rāo's wife was six months advanced in pregnancy, providing she gave birth to

a male child, to invest that infant with the sovereignty, and conduct the

affairs of government agreeably to the details of prudence. As soon as they

had unanimously settled the question after this fashion, a few of the chiefs

took up a position in the outskirts of the city of Pūnā, by way of

protection, and formed a sturdy barrier against the Magog of turbulence.

Raghunāth Rāo, having become aware of the designs of the conspirators,

remained with a slender party [S. 294] in his encampment. Having brooded over his