Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. --19. Zum Beispiel: Niccolao Manucci: Storia do Mogor, 1701 <Auszug>. -- Fassung vom 2008-06-12. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1519.htm

Erstmals publiziert:

Manucci, Niccolao <1639-1717>: A Pepys of Mogul India, 1653-1708 : being an abridged edition of the "Storia do Mogor" of Niccolao Manucci / abridged edition prepared by Margaret L. Irvine ; translated by William Irvine. -- London : John Murray, 1913. -- xii, 310 S. ; 21 cm. -- Originaltitel: Storia do mogor. -- S. 149 - 162. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/pepysofmongulind00manurich. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-20. -- "Not in copyright."

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2008-06-12

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Public domain.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

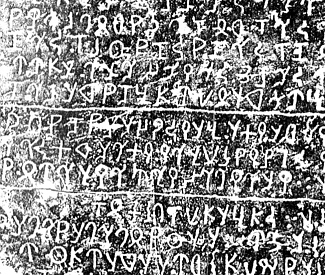

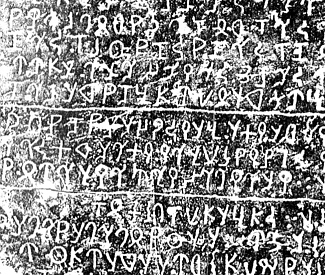

Abb.: Niccolao Manucci

[a.u.a.O., Vortitelblatt]

"Niccolao Manucci (1639–1717) was an Italian writer and traveller. He worked in the Mughal court. He worked in the service of Dara Shikoh [داراشكوه ], Shāh Alam, Raja Jai Singh and Kirat Singh. Storia do Mogor

Manucci is famous for his work "Storia do Mogor", an account of Mughal history and life. Manucci had first-hand knowledge of the Mughal court, and the book is considered to be the most detailed account of the Mughal court. It is an important account of the time of the later reign of Shāh Jahan and of the reign of Aurangzeb.

He wrote about his work: "I must add, that I have not relied on the knowledge of others; and I have spoken nothing which I have not seen or undergone..." but there are some very serious issues regarding the veracity of his work as explained in section that follows below.

ControversyManucci spent almost his entire life in India. He would then send home the manuscript for "Storia do Mogor" which was lent to the French historian François Catrou in 1707. Catrou wrote an another version as ‘Histoire générale de l’empire du Mogul’ in 1715. The original then emerged in Berlin in 1915 and was written in three different languages. This version was translated and then published. Among those who have doubted Manucci's authenticity are the famous British historian Stanley Lane-Poole and Ali Sadiq.

There are some popular events that are so misinterpreted that it is very hard to believe in the veracity of this authors work especially his work "Storia do Mogor". Some major examples are:

- On page 120 on this book, Manucci writes that Akbar (3rd mughal ruler) was born in Persia. It is a very well known fact that has been confirmed by many independent authors that Akbar was born in Sind and not Persia.

- On page 122 Manucci writes about the confrontation between Chand Bibi (regent of Bijapur) and Akbar. It is mentioned by Manucci that Akbar forces defeated Chand Bibi's forces and Akbar fell in love with her and moved her to his own palace. This event is again wrongly portrayed by Manucci, Akbar forces were able to defeat Chand Bibi's forces (they lost once) but Chand Bibi was in fact killed by her own troops and never by Akbar (almost all historians agree on this).

- Again on page 123 comes a completely flawed story about Akbar. Manucci mentioned that Akbar forces attacked Chittor fort and by deceit Akbar took 'Jaimal' a prisoner and asked his wife 'Rani Padmini' to marry Akbar and join his harem or else he will kill Jaimal. Then Manucci expounds in great detail about how Rani Padmini played a trick on Akbar and assured the release of his husband Jaimal (Jai Mall) from Akbars fort. While this event is true but it completely out of time. This event happened in early 1300 AD, almost 250 years before Akbar was born or 350 years before Manucci was born. It was Alauddin khilji, sultan (king) of Delhi at that time who attacked chittor and not Akbar. Rana Rattan Singh was husband of Padmini while Manucci writes Padmini's husband as Jaimal, it should be noted here that Jaimal was commander of Chittor forces in 1567 battle. This incident is widely recorded in Indian history through many paintings and writings and there is not even an iota of doubt that Manucci's work here is not representing history correctly.

There are numerous other incidents in this book which are completely flawed, this raises very big concerns about the veracity of Manucci's work, especially his writings about initial mughal rules Humayun, Babar and Akbar.

Further reading

- Manucci, Niccolao, Storia do Mogor, Eng. trs. by W. Irvine, 4 vols. Hohn Murray, London 1906.

- Lal, K.S. (1988). The Mughal Harem. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-85179-03-2.

- Lane-Pool, Stanley. Aurangzeb and the decay of the Mughal empire (Delhi: S. Chand & Co.1964)

- Ali, Sadiq. A vindication of Aurangzeb in two parts (Calcutta: New Age Press. 1918)

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccolao_Manucci. -- Zugriff am 2008-06-13]

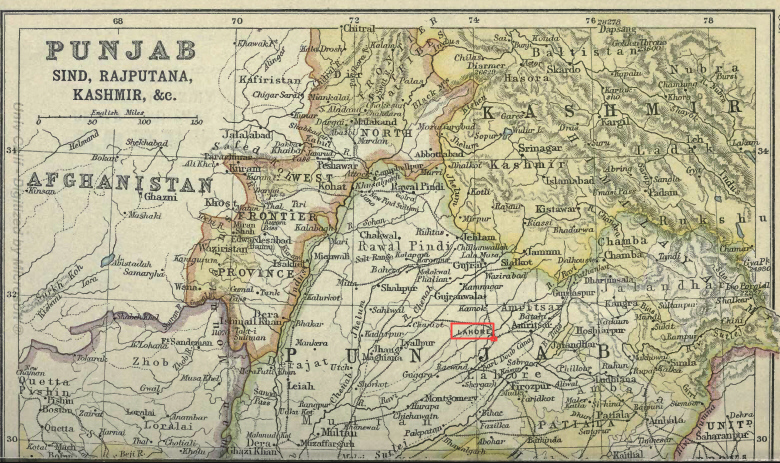

Abb.: Lāhore und Umgebung

[Bildquelle: Bartholomew, J. G. (John George) <1860-1920>: A literary and historical atlas of Asia. -- London : [1912] -- xi, 226 S. ; Ill. : 18 cm. -- S. 58. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/literaryhistoric00bartrich. -- Zugriff am 2008-06-10. -- "Not in cpopyright".]

[S. 149] He (Aurangzeb [اورنگزیب]) ordered, as I have said, that poison should be given to him secretly ; and, since he was on his way to Lāhor [لہور,ਲਾਹੌਰ, لاہو], they told the king there was in that city a Frank physician who might cure him. For this reason there came to me a letter without any name, which stated that in no way must I afford aid to Mahābat Khān [محبت خان]. He who brought me the letter, a man unknown to me, took me by the hand, and, pressing it, said I must pay great heed to the letter, and not to act to the contrary, and then off he went.

Knowing that Mahābat Khān was on his way, and being on friendly terms, I sent out to him a present of some good spirits, that I had prepared myself. His doctor, who had the order to give him the poison, seized the opportunity for my ruin and his own preservation. On the day that the Nawāb [نواب; नवाब,] drank my wine he gave him the poison in an elixir, such as the Mahomedans are accustomed to take. Mahābat Khān found himself troubled with sharp pains, and suspected that there must be poison in my spirits, and that I had acted thus at the instigation of Fidā,e Khān, his enemy. He sent to fetch me in the greatest haste, just as I was ready to go out for a stroll. At once I suspected something. I jumped on my horse and went off to him, he being eighteen leagues away.

Entering the tent, I found everyone in astonishment, for they had the idea that I would never come, being, as they asserted, the culprit. He ordered the tent to be prepared for me, and a good supper, sending [S. 150] to entertain me several of his nephews, great friends of mine ; also a captain called Mīrak Aṭā-ullah. This man was to spy upon me, and see if I spoke with any sign of fear or surprise ; but, as I was quite innocent, I spoke in my usual manner. Next morning I went to see Mahābat Khān again, and I asked him if he had tested the spirits that I had sent, and he said he had. Thereupon I prayed the favour of his giving me a drink of it. They brought me the bottle from which he had drank. I drank, and after I had done so I gave some to his nephews, who praised the liquor. I did this to let him be satisfied that it was not my liquor that had made him bad, but some other thing. I remained with him in talk a long time, and he observed that the spirits did neither me nor his nephews any harm. He then invited me to treat him. I made excuse, saying that he was provided with his own doctor, a very wise man, and that I was not acquainted with that disease. Thus I remained with him nineteen days, and he detained me to find out if the spirits we drank did any harm, either to me or his nephews. He was obliged to let me go without being able to find from me whether he had poison in his inside or not. At my departure he conferred on me a set of robes, and sent the same captain with twenty horsemen to escort me, so that his men, who thought me the cause of his illness, should not harm me. He died a few days afterwards of fetid discharges, a sign that his bowels were ulcerated.

Hardly had I reached Lāhor when a terrible affair happened. This was that the holy man of Balkh [بلخ], to whom Aurangzeb had married the daughter of Murād Bakhsh, went mad. I was treating him as such. But Fidā.e Khān, being away at Peshāwar [پښور; پشاور], Amānat Khān was in his place. He listened to the proposals of the sorcerers, who said that the holy man was possessed by a demon, and not mad. I was obliged to abandon the treatment, Amānat Khān being aggrieved that I had taken on myself to treat a royal connection without [S. 151] first of all consulting him. My answer was that, being by profession a medical man, I went to the house of anyone who sent for me, without making any distinctions ; but since he did not approve of my continuing the treatment, I would that very hour quit the house and the patient.

It happened that a few days afterwards, the sorcerers assuring him that the man was now sane and had no longer a demon in his inside, they allowed him to go for a walk with the princess and her ladies. Having a dagger in his waist-belt, he drew it, and, seizing the princess, stabbed her beneath the ribs towards the side. When the ladies and the eunuchs, on hearing her cries, ran to the spot, he killed one woman with the same dagger, and wounded another in the arm. After this he jumped into the reservoir, playing (bailando) with the dagger, and other obscenities. Then they carried away the princess in a palanquin as speedily as possible to the palace, and a eunuch came careering on horseback to my house. I was urged to make all haste ; I knew not why or wherefore. I sent an order to harness my carriage for us both to go together. But I could not extract from his mouth where it was necessary to go, until at last he told me to carry with me the remedies for the treatment of a wound that the holy man had inflicted on the princess. I protested that I could not go without the permission of the governor, because the princess was of royal blood, nor could I treat her without the king's orders. He paid no heed to those words, and most urgently entreated me not to delay, for the princess was in danger of death. He then told me the whole story.

We started in the carriage, and he made out I was drunk, ordering the carriage to be driven with all speed, stopping for neither hucksters' stalls nor people. Everybody was amazed to see a Frank, who usually went by rather quietly, rush past so desperately. We reached the palace, and, on being told the facts as to the wound, I feared a lesion of the bowels. However, [S. 152] continuing my inquiries, I found that the wounds were not mortal. I did my utmost to get an examination before I began the treatment; but the Mahomedans are very touchy in the matter of allowing their women to be seen, or even touched, by the hand ; above all, the lady being of royal blood, it could not be done without express permission from the king. Thus an examination was impossible. But I ordered them to describe the wound, and I had the dagger brought, and I saw that it was only by God's grace that it had not cut the bowels. I made my tents and plasters, mixing in them a balsam which I made ; and, since the persons in the service of these great people are intelligent, I instructed them as to what they had to do. By God's help the treatment succeeded, and in eleven days I healed her completely.

When for the first time I applied the medicine I went to the governor and reported the facts. This was to prevent his expressing surprise afterwards, on hearing such news, and becoming frightened that the king would remark on the want of care with which he had guarded a man who had been declared mad. He entreated me earnestly to make my best efforts to cure the princess. Meanwhile he wrote to the king about the case, and told him that a demon had entered the body of the holy man, and the princess had been mortally wounded with a dagger. But a Frank doctor named Ḥakīm Niccolao had attended her, and held out hopes that she would be well in a short time. This event brought me to the notice of many nobles who were in the camp. For on the matter becoming public, my friends wrote to their acquaintances, and the princess herself, as soon as she was well, wrote to the king that I had perfectly restored her, and she gave me a handsome present.

Another case occurred which made me famous throughout the kingdom. It was as follows: Fidā,e Khān ordered the beheadal of a powerful rebel, who plundered in all directions in the king's territories ; he [S. 153] was brother-in-law of the qāẓī [قاضي] of Lāhor. His name was Theka Araham (? Thīkā, Arāin) and he was extremely fat. I thought it was a good chance of laying in a stock of human fat, procuring it from the man and his companion, who also was very obese. I spoke to Fidā,e Khān, pointing out the necessity I was under of having this medicament. As the opportunity was favourable, would he give orders to remove the fat from these two condemned men ? He then ordered the koṭwāl to have this done, and in compliance with the order, men were sent to carry out the operation. I thus acquired eighteen sirs that is, five hundred and four ounces purified.

This matter caused great talk in the city, and the qāẓī, assembling many of the learned, sent men to complain to the king against Fidā,e Khān, for protecting a Frank. On his behalf he had committed the sacrilege of removing the fat of a Mahomedan, a man who read the Qurān [القرآن ] and yet had been thus afflicted. According to the strict law the Frank deserved to be burnt, but as Fidā.e Khān declined to listen to argument, they were forced to come to His Majesty to present a complaint and demand justice.

I was warned of the plot, and spoke to Fidā,e Khān about the qāẓī's intentions. He sent at once a messenger to court, to report that the population of Lāhor were restless, and if there came any complaint about the beheaded man, Thīkā,Arāin, it must not be listened to, for the qāẓī and others had been his supporters. This was enough to secure that on the arrival of the complaint at court, where many had clad themselves in mourning to present the petition, the king should send them away after saying very little, with the remark : "Caziey zemi, bessare zemi " (Qaẓāyā-i-zamīn bar-sar-i-zamīn). This means: "Cases about land are settled on the land itself." Thus I was left unharmed for that once, and freed from a great persecution that would have cost me my life.

God was pleased to deliver me once more after [S. 154] several months. For there came a relation of the beheaded man expressly to kill me. By a lucky chance he came when I was prescribing for the sick, distributing medicine, adding alms for those in want. He came into my dīwān with his sword and shield, leaving his spear and horse at my door. Without any salutation he sat down in front of me and watched my movements, the humanity with which I spoke to the sick, and the liberality with which I succoured the needy. Nor did I fail from time to time to observe the face of this new guest, without knowing either who he was or what he wanted. I wondered at his wrathful countenance, his head-shakings, and other signs of a man in anger. Having got rid of my patients, I asked him more than once if he wanted anything in which I could be of use, but he returned no answer. At length there being no one else left, he asked me if I knew the cause of his coming. I replied I did not. He said he had come resolved to kill me because I had removed the fat from his uncle. But finding that in my hands it was being well employed, he felt satisfied at making my acquaintance. He rose to his feet, refusing to eat, or take betel, or listen to my words. He could have killed me quite safely, but God was pleased to change his intentions, in reward for the little or much that I managed to do for the poor who were in ill-health.

The qāẓī did not find it so easy to forget his anger against me. Fidā,e Khān did not stay much longer in Lāhor. He (the qāẓī) then sent someone for me, and on my presenting myself he was very affectionate, but did all he knew to trip me up in my talk. He began a conversation about the fat of his brother-in-law, asking me if ever I gave such fat to be taken for a medicine, and for what complaints it was used. I answered, in ignorance of his maliciousness, that fat was not administered by the mouth, but served simply to make ointments in nervous disorders. It was lucky that I answered thus, for if I had said that the fat [S. 155] was also given by the mouth, it would have been enough to afford him an opening for planning a fresh persecution against me, and ordering me to be tortured.

It appeared to him most barbarous to prescribe human fat to be taken, imagining I did this to make mock of the Mahomedans, by getting one man to eat the fat of another. After this, I fell into conversation with him and discovered his malice, and saw the kindness God had done me in making me reply as above. For it was this which had delivered me from death. But he who came to catch me got caught himself. On his demanding of me some remedy for a cough he had, I told him of various drugs ; among other things I said that, as he was an old man, human "myrrh" would be good. He answered that he had already taken it, but it had done him not the least good. Upon this, with a smile, I said openly to him, that to me it did not seem much of a thing to give human fat through the mouth by way of medicine, when at the same time he had no scruple in eating human flesh and fat. For that is what is meant by human "myrrh." He also could not help laughing, and told me that such medicines were to be taken secretly only, so that no one knew.

This persecution was bad enough, but without a doubt the Christians persecuted me worse than the Mahomedans. It arose from their envy at seeing me with name and fame, whereas at the place where I had settled down I had done no harm to any one of them. God alone knows how many times they tried to murder me, and they sent men to steal my books, on which I relied. Finding their projects had no success, they made up their minds to do openly what they had failed to do in hiding. To this end they sent four Europeans of various nations to murder me. Two came into the house as friends and began to talk to me ; another who was to do the deed stood in the doorway, shouting hoarsely a thousand abusive [S. 156] terms at my servants ; and the last sat on his horse with his pistols ready, to back up what was going on at the door. Hearing this row I came out, begging the disturber to hold his tongue ; he might come in if he wanted to, but if he did not come in, let him go his way. When he heard this he fired his pistol, which was already at full-cock, when one of my servants, grappling with him, took the pistol from his hand. He drew his sword to defend himself from the servants, who had begun settling his business for him with thick sticks, applying them without remorse to him and his servants until they fled. Then I recognised that it was planned treachery and ordered one of my servants, with a drawn bow, to see that the one on horseback should not move his hand in the direction of his pistols ; if he moved, an arrow was at once to be let fly at him. Thus terrorised, he was afraid to stir or to assist his companion who was getting his beating. I told the others with their bows and arrows to watch, without a word, over the two men in the house. Meanwhile, I ordered a good thrashing to be given to the insolent fellow. While drawing his sword to defend himself from the servants he cut his hand, and one of my servants seized him round the body so violently that he was brought to the ground. But he would not let his sword be taken away ; I therefore ordered them to give it to him well until he let go the sword. Seeing that he still clung to it, one of the men planted one foot on his chest, and so crushed it that he had to give up the sword. Thereupon I told them to bind him and carry him to the magistrate. But the man on horseback dismounted, and earnestly begged me not to pass this affront upon a white man. His petition was his undoing. I told him to fall at his protector's feet. He declined, but my servants by thumps and holding his neck got him to his knees.

Then I left all the four, and rode off at once to Fidā,e Khān, who at the time this happened was in [S. 157] Lāhor. He recognised that I had good reason for anything that I had done, and sent men to escort my assailants to the other side of the river Chināb [ਚਨਾਬ, चनाब, چناب], and on the road he who was the leader died. I will state here that my enemies seized this occasion at the time that the Europeans of the army were on their way to the attack on the Paṭhāns, since being war-time no one would be able to know afterwards who had made the attempt. But God, who seemed to cherish a special desire for my protection, would not permit my death at the hands of those who wished to do so on the quiet by entering my house in the guise of friends. They did not succeed in this or other treacheries, but my enemies managed to give me poison, from which I escaped, although I felt its effects for some years.

So great was the name that I had of being fortunate with the cases that I undertook that they came from many places distant from Lāhor to call me in to visit patients. This was of great profit to me, even to the extent that many wanted me in marriage. If I had been of little wisdom I should have had no want of marriage proposals of exceptional quality among the Mahomedans. But, thanks to God, although I left home a mere youth, there remained ever graven on my memory the good teaching of my parents.

But I cannot resist telling of one case that happened to me with a well-connected widow woman, the daughter of Dīndār Khān, Paṭhān. On one occasion I had treated one of her sisters at Qasūr, twenty leagues from Lāhor. This lady was present, and took such a fancy to me that she wanted to marry me. She herself spoke to me about it, and told me she would make her own arrangements for flight. At first I paid no heed to these things, still, seeing the woman so determined, and she being rich, well proportioned, and intelligent, I began to entertain the idea of carrying her off to Europe as she desired.

The agreement was that she should give sufficient [S. 158] money to buy a big ship, on which would be placed the bulk of her wealth. Then she would pretend that she had vowed a pilgrimage to Mekka, would obtain permission for this, and leave home. When she was on her voyage, and had left the port of Surat, I with my ship was to fall upon the vessel going to Mekka, and carry her off with me to Europe. The agreement was in process of execution, but she was not sufficiently prudent. She roused suspicions of her affection for me by forwarding message upon message by an old woman in her service. But the special cause for the non-execution of the agreement was a Portuguese called João Rodrigues de Abreu. After having done him many favours, and proved him sufficiently faithful, I confided our plans to him, intending to take him along with me. But he did not act in correspondence to my friendship, for he went off and told Misrī Khān, who was a suitor for marriage with the same woman.

Discovering thus the agreement we had made, and the friendship of the said widow, which she had declared by sending me messages with valuable presents, Misrī Khān, through fear of Fidā,e Khān and other nobles who were very fond of me, was content not to do me any harm, or send men to murder me, but only wrote me a letter in which he said that he knew quite well why Jānī Bībī, the widow's maidservant, came so often to my house, but he saw quite well that what I was doing would in the end cost me my life. I pretended I did not understand the letter, and replied that Jānī Bībī came and went as if she were my mother. If it displeased him that she came to my house he had only to tell her not to go again. By this means I found out we were already discovered. When Jānī Bībī came I asked her to inform her mistress that it was no longer safe to come, and she must conceal everything or she would cause my death. On finding that her project could not succeed, the widow married Misrī Khān, but only lived for eight days after her marriage. If I had been like many [S. 159] Europeans in the Mogul country and Hindustan, I should have accepted the money that she wanted to give me for buying the ship, then taken flight for Europe, disregarding the marriage and all my promises. I did not act thus, not for fear of discovery, but because I had always professed to be an honest man, and thus I did not allow myself to fall into this temptation. The only thing that weighed upon me was that, through the treachery of that Portuguese, the lady continued to be a Mahomedan when she desired to become a Christian.

The fame I had acquired as a good surgeon and physician was the cause, among other things, that I was importuned by the eunuch Daulat, a man of staid habits, rich, and well known. This eunuch was in the employ of 'Ali Mardān Khān, he who made over the fortress of Qandahar [کندهار] to the King Shāhjahān [شاه جهان]. When his master died, in the year one thousand six hundred and fifty-two, this eunuch of his carried his bones to Persia to be buried in the tomb of his forefathers. The fact became known to Shāh 'Abbās [شاه عباس ], at that time King of Persia, who ordered the arrest of the eunuch Daulat. 'Ali Mardān Khān's remains he directed to be burnt, and the eunuch's nose and ears to be cut off. He was then to be expelled from the country. The king held it an act of presumption to bring the bones of a traitor to the kingdom of which in his lifetime he was a declared enemy.

The wretched Daulat retired full of shame to Lāhor, and kept close within his house. Knowing the work I had done, he several times requested me by some art or ingenuity to make his nostrils and ears grow again, an impossible thing. But he imagined that Christians could do impossible things with elixirs. Therefore he besought and entreated me that I would do to him this favour, and he would give me anything I asked. I answered that now there was no remedy, the wounds being old, for if they had been fresh something might have been done. This reply of mine [S. 160] only inspired greater hopes, and he asked me to renew the sores by making new wounds. Then I was to cut off the best-shaped nose and the finest ears from one or other of his slaves, and apply them to his face. He embraced me, he styled me Galen, Bū Alī (i.e. Avicenna), Aristotle, and Plato ; he begged me to do him this favour, and make him happy all the rest of his life.

The slaves then present were in a great state of mind lest I should accept the eunuch's proposal, and gazed at me with mournful faces, as if entreating me not to comply with the request. I was laughing inwardly at them, contrasting the eagerness of Daulat with the fright of the slaves. But as a final answer I stated that even if I did what he asked, and cut off the noses and ears of the slaves, it would be of no avail, for being another's flesh it would never unite, the only result being to disfigure his slaves without any benefit to him. Finding there was no remedy, and being a facetious fellow, he said in joke : "I know not what sins I have committed to be made an out-and-out eunuch twice over, first in my inferior part, and secondly in my upper half. Now there is nothing more to deprive me of, nor do I fear anything but losing my head itself." This saying served us often afterwards as a subject of conversation.

Not only was I famed as a doctor, but it was rumoured that I possessed the power of expelling demons from the bodies of the possessed. This idea spread because I was a man capable of conversation, in which I showed my nimbleness of wit whenever an occasion presented itself. Once some Mahomedans were at my house consulting me about their complaints, when night came on. I did not want to lose the chance of over-aweing them, and letting them see that I had the power of giving orders to the devil. In the middle of our talk I began to speak as if to some demon, telling him to hold his tongue and not interrupt my talk, and let me serve these gentlemen, for it was already late. Then [S. 161] I resumed my conversation with the Mahomedans. But now they had only half their souls left in their bodies, and spoke in trembling tones. I made use of their terror for my own amusement, and raising my voice still more I shouted at him whom I assumed to be present, lying invisible in some corner. I resumed my talk to the Mahomedans, and this I did four or five times, each time showing myself more provoked and fierce. At length I threatened the demon with expulsion from the house, and rising to my feet, angrily laid hold of a coarse glass bottle in which I had a little spirits of wine, and going near the candle set light to it, and uttered a lot of abuse to the supposed unquiet spirit. Then approaching the window, I made a noise with the bottle like a pistol-shot. I returned the bottle to its place and said to the demon that I objected to his coming any more into my house. I then turned again to the Mahomedans, and resumed the conversation. They were unable to speak a word out of fright, and prayed for permission to leave, they would come back another time. But the special joke was that they were afraid to go out, dreading that the demon might attack them in the street. I reassured them by saying that the demon stood in fear of me, and would not do such a thing, for I had the means of punishing him. It would suffice, while going to their houses, for them to say en route that they came from the Doctor Sāhib. A grand medicine certainly, and a great exorcism for a make-believe phantasm !

But this was not enough to induce them to venture out ; whereby I was forced to send with them one of my servants, who as they progressed was to mutter : "Duhāī Ḥakīm Jī" that is : "On the part of the Doctor Sahib." Under these conditions I got rid of all those Mahomedans. Being credulous in matters of sorcery, they began to bruit abroad in all directions that the Frank doctor had the power of expelling demons, including dominion over them. This was enough to make many come, and among them they [S. 162] brought before me many women who pretended to be possessed (as is their habit when they want to leave their houses to carry out their tricks, and meet their lovers), and it was hoped that I could deal with them. The usual treatment was bullying, tricks, emetics, clysters, which caused much amazement, the actual cautery, and evil-smelling fumigation with filthy things. Nor did I desist until the patients were worn out and said that now the devil had fled. In this manner I restored many to their senses, with great increase of reputation, and still greater diversion for myself. It may be that some reader will not put faith in me, but Europeans who are acquainted with the Mogul country, and my character in India, know that I was capable of many practical jokes of this sort. What is certain is that I very seldom lost my temper, and knew how to divert myself in proper time and place with harmless amusements.

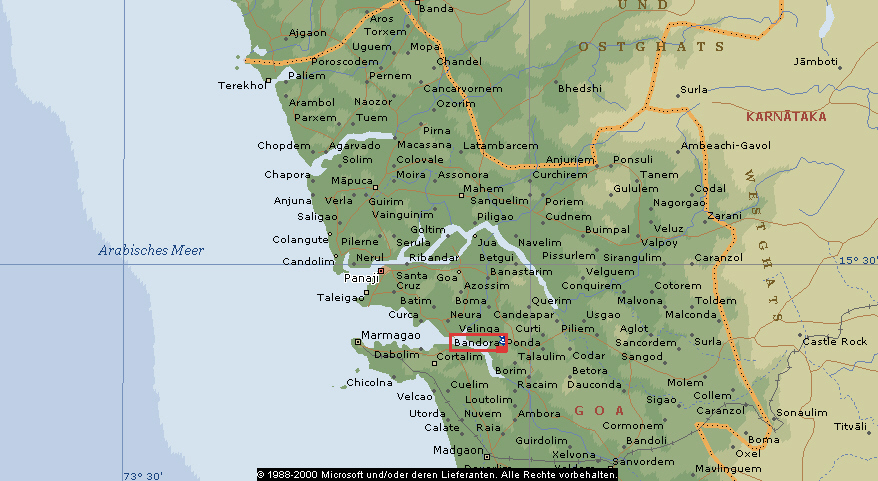

Abb.: Lage von Bandora

(©MS Encarta)

Having acquired a sufficient capital, I became desirous of withdrawing from the Mogul country and living once more amongst Christians. This I could not effect by moving to Goa, for the mode of life of those gentlemen did not suit me. I resolved to retire to a village called Bandora, which is under the Jesuit Fathers, who do not allow any of the Portuguese to live in it, beyond a few of their own faction. For as soon as a white man appears they put a spy on him, who follows him constantly. On no account will they allow such a man to sleep in the village. Nevertheless, as they knew that I was not a troublesome man, they were content to allow me to become a resident. In the village dwelt many merchants of different nations, it being a place of trade. One could live there in security through the efforts of the fathers in defending themselves from the thieves, who traversed the ocean in such numbers that it was necessary for many vessels together to leave port, for the Malavares (? Mālabārīs) and Sanganes (? Sanjānīs) infest this coast."

Zu: 16. Quellen aus der Zeit des British Raj