Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Chronik Thailands = กาลานุกรมสยามประเทศไทย. -- Chronik 1833 (Rama III). -- Fassung vom 2017-01-10. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/chronik1833.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2013-07-01

Überarbeitungen: 2017-01-10 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-10-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-09-07 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-08-16 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-05-09 [Teilung des Kapitels] ; 2015-05-08 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-04-22 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-16 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-04 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-01-24 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-12-15 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-11-13 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-11-04 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-10-27 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-09-21 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-08-20 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-03-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-03-08 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-02-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-01-13 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-12-20 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-12-05 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-11-25 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-11-05 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-10-11 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-09-28 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-09-23 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-09-17 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-09-02 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-08-23 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-08-21 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-08-14 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-08-11 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-07-13 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-07-10 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-07-08 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der

Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche

Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Herausgebers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Thailand von

Tüpfli's Global Village Library

ช้างตายทั้งตัวเอาใบบัวปิดไม่มิด

|

Gewidmet meiner lieben Frau Margarete Payer die seit unserem ersten Besuch in Thailand 1974 mit mir die Liebe zu den und die Sorge um die Bewohner Thailands teilt. |

|

Bei thailändischen Statistiken muss man mit allen Fehlerquellen rechnen, die in folgendem Werk beschrieben sind:

Die Statistikdiagramme geben also meistens eher qualitative als korrekte quantitative Beziehungen wieder.

|

1833/34

Anhaltende Dürre. Der Reispreis ist 30 Baht pro Wagenladung.

1833/1834

Neue Steuern werden eingeführt:

- auf Feuerholz

- auf Nipapalmen (Nypa fruticans)

- auf Rohrzucker

- auf Palmzucker

Abb.: Nipapalme (Nypa fruticans)

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas 1880 - 1883 / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

1833

Rückeroberung des von Vietnam besetzten Houaphanh (ຫົວພັນ). Es wird Luang Prabang (ຫລວງພະບາງ) unterstellt. Vietnam behauptet aber weiterhin seine Oberherrschaft.

Abb.: Lage von Houaphanh (ຫົວພັນ) und Luang Prabang (ຫລວງພະບາງ), 1974

[Bildquelel: CIA. -- Public domain]

1833

Vietnam stationiert Truppen vis-a-vis von Nakhon Phanom (นครพนม), sowie in den Flusstäler der Flüsse Banghian, Bangfai (ແມ່ນ້ຳເຊບັ້ງໄຟ) und Kadin. Siamesische Truppen evakuieren und Verbrennen Dörfer am Mekanog, sodass vietnamesische Truppen keine Grundlage für ihre Versorgung haben. Rama III. befiehlt "die Routen der vietnamesischen Armeen völlig abzuschneiden."

Abb.: Lage von Nakhon Phanom (นครพนม), sowie in den Flusstäler der Flüsse Banghian, Bangfai (ແມ່ນ້ຳເຊບັ້ງໄຟ) und Kadin

[Bildquelle: CIA. -- Public domain.

1833 - 1834

"In 1833 rumors of Thai plans to invade Vietnam began to take concrete form. The Lao peoples’ fear and suspicion of the Vietnamese were increasing; in addition, famine struck the Lao hills. The court at Hue appears to have been less worried about Lao problems than about the possibility of Vietnamese "pirates" establishing bases in the Lao hills in order to strike against the lowlands. The Vietnamese garrison at the Plain of Jars [ທົ່ງໄຫຫິນ] remained small. Then Luang Prabang [ຫຼວງພະບາງ] ceased paying tribute, and some of its men, armed, appeared at Tran-ninh to trade. The court became suspicious and gave orders for its outposts to stay alert.

Abb.: Lage von Luang Prabang [ຫຼວງພະບາງ] und Tran-ninhRelations between Luang Prabang and Hue became strained, and the restlessness in the hills increased. More local chiefs took flight and moved to Thai territory. But when Luang Prabang did send tribute, Vietnamese vigilance relaxed, and Minh Mang [明命, 1791 - 1841]] agreed to the Lao request that the people of a certain muong [ເມືອງ], who had fled to Tran-ninh earlier, be permitted to return to Luang Prabang. Thus, the movement away from Vietnamese territory continued, right under the eyes of Hue. Leaders who had fled sent men back to draw others out. Word of Thai strength passed through the hills.

Toward the end of the year a Thai officer and a Lao prince announced explicitly that they were going to invade the outer territories under Vietnamese sway. The Thai forces began to move. Using local disaffection with Vietnamese control as their own pretext, the Thai opened a northern front at the same time that they fought the Vietnamese for control of Cambodia. Thai troops also struck across the central mountains into the Cam-lo area, in the western part of Quang-tri province in Vietnam.

New year 1834 came and went, with Minh Mang responding slowly. The Thai-Luang Prabang forces (500 Thais and 4,500 Lao) pressed on toward the Plain of Jars [ທົ່ງໄຫຫິນ], easily gaining control of the Vietnamese territories beyond Tran-ninh. The Plain itself, with its difficult entry and Vietnamese fortifications, was another matter. Vietnamese troops easily repulsed the Thai attacks. At this point, the chao-muong [ເຈົ້າເມືອງ]of Xieng Khouang [ຊຽງຂວາງ] rebelled, caught the Vietnamese completely by surprise, and massacred their garrisons. According to the Xieng Khouang chronicle, the chao- muong had actively sought Thai intervention.

Since the geopolitical relationship of the Plain of Jars [ທົ່ງໄຫຫິນ] to Vietnamese strength was obvious, the Thai decided here, and elsewhere on the periphery of Vietnam, to remove the population and to lay waste the area, intending to deprive the Vietnamese forces of as much support as possible upon their return. In this way, Bangkok ensured a definite buffer around the domain which it had so meticulously carved out. The Thai promised the men of Xieng Khouang neighboring territory on the other side of the Mekong, and they agreed to move. But they were driven deeper into the Thai state and forced to settle where they could be easily controlled by the Thai. Some, however, were able to break away and return home."

[Quelle: John K. Whitmore. -- In: Laos : war and revolution / ed. by Nina S. Adams and Alfred W. McCoy. -- New York : Harper & Row, 1970. -- 482 S. ; 21 cm. -- SBN 06-090221-3. -- S. 60ff. -- Fair use]

Abb.: Lage von Plain of Jars [ທົ່ງໄຫຫິນ], Xieng Khouang [ຊຽງຂວາງ] und Cam Lo

[Bildquelle: CIA. -- Public domain]

1833

Malaiische Kriegsgefangene werden nach Bangkok gebracht.

1833

Als erstes Dampfschiff patrouilliert HMS Diana der British Royal Navy in den Gewässern vor Penang und Phuket. Es hat zwei Kanonen an Bord und 25 Mann Besatzung.

"Her captain, Sherrard Osborne, tells of his first encounter with Illanun pirates. The pirates, never having seen a steamship, decided from her smoke that she must be a sailing ship on fire, whose masts had burned down and was therefore a prime target. They approached, anticipating an easy capture. "To their horror the Diana came up to them against the wind and then, stopping opposite each prahu, poured in her broadsides at pistol shot range. One prahu was sunk, 90 Illanuns were killed, 150 wounded and 30 taken."

The other five galleys escaped in a shattered condition

"and baling out apparently nothing but blood and scarce a man at the oars ... three of them foundered before they reached home.""

[Quelle: Mackay, Colin <1936 - >: A history of Phuket and the surrounding region. -- Bangkok : White Lotus, 2013. -- 438 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN 978-974-480-195-1. -- S. 191f.]

1833

Der Mönch Vajirañāṇo Bhikkhu (วชิรญาโณ ภิกขุ), der spätere König Rama IV., gründet den Dhammayuttika Nikaya (Thammayut Nikaya) - ธรรมยุติกนิกาย

"Thammayut Nikaya (Pali), wörtlich „Die sich strikt an das Dhamma halten“ ist ein Orden der buddhistischen Theravada-Mönche in Thailand. Er steht im Gegensatz zur Mahanikai („Große Glaubensgemeinschaft“), dem bisherigen thailändischen Mönchsorden. Die Thammayut-Gemeinschaft wurde Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts von Prinz Mongkut gegründet. Prinz Mongkut war der Sohn von König Phra Phuttaloetla (Rama II.), er wurde später als Phra Chom Klao zum König von Siam gekrönt, im Ausland als König Mongkut (Rama IV.) bekannt. Mongkuts Bestreben war es, die Disziplin des Mönchsordens zu straffen, nachdem er beim Studium der Pali-Sprache eine große Diskrepanz feststellte zwischen den Regeln, die im Pali-Kanon geschrieben standen, und der alltäglichen Praxis in den Klöstern. Er sah, dass der siamesische Mönchsorden nur ein trauriges Abbild darstellte von der engagierten Gemeinschaft, die der Buddha selbst organisiert hatte, um seine Lehre weiterzutragen. Die alten Vorschriften wurden nur mehr mechanisch angewandt, die Disziplin war lax, es gab sogar korrupte Mönche, nur wenige interessierten sich für eine wissenschaftliche Weiterbildung, die Meditation wurde nur gelernt, um übernatürliche Kräfte zu erlangen.

Die Thammayut-Mönche nun verwarfen alle Zeremonien, die nur noch aus alter Gewohnheit durchgeführt wurden, aber keine Grundlage im Pali-Kanon hatten. Sie legten die Uposatha-Tage neu fest aufgrund der wirklichen Phasen des Mondes und nicht nach einem althergebrachten Kalender. Sie sahen die Jataka (Geburts-Geschichten), die von den letzten 550 Leben des Buddha erzählen, als reine Folklore an. Auch die Vorstellung von Himmel und Hölle, wie sie in dem alten Text Traiphum Phra Ruang seit Jahrhunderten gelesen wurde, lehnten sie als Aberglauben ab. Thammayut-Mönche essen nur ein einziges Mahl am Tag, und auch nur das, was sie auf ihrer morgendlichen Runde in ihre Mönchs-Schalen gelegt bekommen. Von den Thammayut-Mönchen wurde erwartet, dass sie die Sutras auch verstanden, die sie rezitierten. Prinz Mongkut richtete dazu eine eigene Pali-Schule im Wat Bowonniwet ein, zu dessen Abt er kurz zuvor berufen worden war.

Nicht zuletzt aufgrund eines Abtes von königlicher Herkunft und der ausdrücklichen Duldung von König Phra Nang Klao (Rama III.) wurde der Thammayut-Orden bald sehr bekannt. Fünf weitere Klöster schlossen sich der Bewegung an, und auch in den Mahanikai-Klöstern wurde über eine Verbesserung der augenblicklichen Situation nachgedacht.

Obwohl sich heute die Thammayut-Mönche noch immer in der Minderzahl befinden – das Verhältnis Mahanikai zu Thammayut ist etwa 35:1 – bekannten sich doch eine Reihe hochverehrter Mönche zu dieser Glaubensgemeinschaft, zum Beispiel Phra Ajahn Sao Kantasilo Mahathera (1861-1941) und Phra Ajahn Mun Bhuridatta (1870-1949). Auch der derzeitige Supreme Patriarch von Thailand, Somdet Phra Nyanasamvara Suvaddhan gehört dem Thammayut-Orden an.

Literatur

- A.B. Griswold: King Mongkut Of Siam. The Asia Society, New York 1961, distributed by The Siam Society, Bangkok"

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thammayut_Nikaya. -- Zugriff am 2011-10-18]

1833

Der Mönch Vajirañāṇo Bhikkhu (วชิรญาโณ ภิกขุ), der spätere König Rama IV. entdeckt (andere sagen: fälscht) in Sukhothai (สุโขทัย) eine Steinstele (ศิลาจารึกพ่อขุนรามคำแหง) mit einer Inschrift angeblich von König Ramkhamhaeng (พ่อขุนรามคำแหงมหาราช, 1239 - 1298), datiert 1835 B.E. (= 1292 C. E.). Die Inschrift wird eine nicht zu unterschätzende Rolle für die Staatsideologie Siam/Thailands spielen.

Abb.: Kopie der Ramkhamhaeng-Stele

[Bildquelle: Ananda / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Seite 2 der Inschrift

[Bildquelle: http://www.seasite.niu.edu/thai/inscription/Face21.jpg. -- Zugriff am 2013-01-14. -- Fair use]

"Stone inscription on the Ramkhamhaeng stele, now in the National Museum in Bangkok. This stone was allegedly discovered in 1833 by King Mongkut (then still a monk) in Wat Mahathat (วัดมหาธาตุ). The authenticity of the stone – or at least portions of it – has been brought into question.[7] Piriya Krairiksh, an academic at the Thai Khadi Research institute, notes that the stele's treatment of vowels suggests that its creators had been influenced by European alphabet systems; he concludes that the stele was fabricated by someone during the reign of Rama IV or shortly before. The subject is very controversial, since if the stone is a fabrication, the entire history of the period will have to be re-written.[8]

^ Centuries-old stone set in controversy, The Nation, Sep 8, 2003 ^ The Ramkhamhaeng Controversy: Selected Papers. Edited by James F. Chamberlain. The Siam Society, 1991" [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramkhamhaeng_inscription#The_Ramkhamhaeng_stele. -- Zugriff am 2013-01-14] Übersetzung der Inschrift: "My father was named Sri lndraditya, my mother was named Nang Suang, my elder brother was named Ban Muang. There were five of us born from the same womb: three boys and two girls. My eldest brother died when he was still a child.

When I was nineteen years old, Khun Sam Chon, the ruler of Muang Chot, came to raid Muang Tak. My father went to fight Khun Sam Chon on the left; Khun Sam Chon drove forward on the right. Khun Sam Chon charged in; my father’s men fled in confusion. I did not flee. I mounted my elephant, named Bekhpon, and pushed him ahead in front of my father. I fought an elephant duel with Khun Sam Chon. I fought Khun Sam Chon’s elephant, Mas Muang by name, and beat him. Khun Sam Chon fled. Then my father named me Phra Ramkhamhaeng because I fought Khun Sam Chon’s elephant.

In my father’s lifetime I served my father and I served my mother. When I caught any game or fish I brought them to my father, when I picked any acid [sour] or sweet fruits that were delicious and good to eat I brought them to my father. When I went hunting elephants and caught some, either by lasso or by driving them into a corral, I brought them to my father. When I raided a town or village and captured elephants, men and women, silver or gold, I turned them over to my father. When my father died, my elder brother was still alive, I served him steadfastly as I had served my father. When my elder brother died, I got the whole kingdom for myself.

In the time of King Ramkhamhaeng this land of Sukhothai is thriving. There are fish in the water and rice in the fields. The lord of the realm does not levy tolls on his subjects. They are free to lead their cattle or ride their horses to engage in trade; whoever wants to trade in elephants, does so; whoever wants to trade in horses, does so; whoever wants to trade in silver or gold, does so. When any commoner or man of rank dies, his estate — his elephants, wives, children, relatives, rice granaries, retainers and groves of areca and betel — is left in its entirety to his son. When commoners or men of rank differ and disagree, the King examines the case to get at the truth and then settles it justly for them. He does not connive with thieves or favor concealers of stolen goods. When he sees someone’s belongings, he does not covet them; when he sees someone’s wealth, he does not get envious. If anyone riding an elephant comes to him to put his own country under his protection, he helps him, treats him generously, and takes care of him; if someone comes to him with no elephants, no horses, no men or women, no silver or gold, he gives him some, and helps him until he can establish a state of his own. When he captures enemy warriors or their chiefs, he does not kill them or beat them.There is a bell hanging at the gate; if any commoner in the land is involved in a quarrel and wants to make his case known to his ruler and lord, it is easy; he goes and strikes the

bell which the King has hung there; King Ramkhamhaeng, the ruler of the kingdom, hears the bell; he calls the man in and questions him, examines the case, and decides it justly for him. So the people of this land of Sukhothai praise him. They plant areca groves all over the city; coconut groves and jackfruit groves are planted in abundance in the city. Anyone who plants them gets them for himself and keeps them. Inside this city there is a pond called Traphang Poisi, the water of which is as clear and as delicious as the water of the Khong in the dry season. The triple rampart surrounding this city of Sukhothai measures three thousand four hundred wa.

The people of this city of Sukhothai like to observe the precepts and bestow alms. King Ramkhamhaeng, the ruler of this city of Sukhothai, as well as the princes and princesses, the men and women of rank, and all the noblefolk without exception, both male and female, all have faith in the religion of the Buddha, and all observe the precepts during the rainy season. At the close of the rainy season they celebrate the Kathin ceremonies, which last a month, with heaps of cowries, with heaps of areca nuts with heaps of flowers, with cushions and pillows: the gifts they present to the monks as accessories to the Kathin amount to two million (cowries) each year. Everyone goes to the Araññika over there for the Kathin ceremonies. When they are ready to return to the city they walk together, forming a line all the way from the Araññika to the parade-ground. They join together in striking up the sound of musical instruments, chanting and singing. Whoever wants to make merry, does so; whoever wants to laugh, does so. As this city of Sukhothai has four very big gates, and as the people always crowd together to come in and watch the lighting of candles and setting off of fireworks, the city is as noisy as if it were bursting.

Inside this city of Sukhothai, there are viharas, there are golden statues of the Buddha, and Phra Attharos statues; there are big statues of the Buddha and medium-sized ones, there are big viharas and medium-sized ones; there are senior monks — nissayamuttakas, theras and mahatheras.

West of this city of Sukhothai is the Araññika, where King Ramkhamhaeng bestows alms to the Mahathera Sangharaja, the sage who has studied the Tripitaka from beginning to end, who is wiser than any other monk in the kingdom, and who has come here from Muang Sri Dhammaraja. Inside the Araññika there is a large rectangular vihara, tall and exceedingly beautiful, and a Phra Attharos statue standing up.

East of this city of Sukhothai there are viharas and senior monks, there is a vast open field, there are groves of areca and betel, upland and lowland farms, homesteads, large and small villages, groves of mango and tamarind. They are as beautiful to look at as if they were made for that purpose.North of this city of Sukhothai there is a bazaar, there is Phra Acana, there are prasadas, there are groves of coconut and jackfruit upland and lowland farms, homesteads, large and small villages.

South of this city of Sukhothai there are kutis and viharas where monks reside, there is a dam, there are groves of coconut and jackfruit, groves of mango and tamarind, there are small mountain springs and there is Phra Khaphung. The divine spirit of that mountain is more powerful than any other spirit in this kingdom. Whatever lord may rule this kingdom of Sukhothai, if he makes obeisance to him properly, with the right offerings, this kingdom will endure, this kingdom will thrive; but if obeisance is not made properly or the offerings are not right, the spirit of the mountain will no longer protect it and the kingdom will be lost.

In 1214 saka, a year of the dragon, King Ramkhamhaeng, lord of this kingdom of Sri Sajjanalai - Sukhothai, who had planted these sugar palm trees fourteen years before, commanded his craftsmen to carve a slab of stone and place it in the midst of these sugar palm trees. On the day of the new moon, the eighth day of the waxing moon, the day of the full moon, and the eighth day of the waning moon, the monks, theras or mahatheras go up and sit on the stone slab to preach the Dhamma to the throng of lay people who observe the precepts. When it is not a day for preaching the Dhamma, King Ramkhamhaeng, lord of the kingdom of Sri Sajjanalai - Sukhothai, goes up, sits on the stone slab, and gives audience to the officials, lords, princes and those who conduct affairs of state. On the day of the new moon and the day of the full moon, when the white elephant named Rucagri has been decked out with howdah and tasseled head cloth, and always with gold on both tusks, King Ramkhamhaeng mourns him, rides away to the Araññika to pay homage to the Buddha, and then returns.

There is an inscription in the city of Chaliang, erected beside the Sri Ratanadhatu; there is an inscription in the cave called Phra Ram’s Cave, which is located on the bank of the River Samphai; and there is an inscription in the Ratanadhatu Cave. In this Sugar Palm Grove there are two pavilions, one named Sala Phra Mas, one named Buddhasala. This slab of stone is named Manangsilabat. It is installed here for everyone to see.King Ramkhamhaeng, son of King Sri Indraditya, is the lord of the kingdom of Sri Sajjanalai - Sukhothai, and all the Ma, the Kao, the Lao, the Thai of the distant lands, and the Thai who live along the U and the Khong come to pay homage.

In 1207 saka, a year of the boar, he caused the holy relics to be dug up so that everyone could see them. They were worshipped and celebrated for a month and six days, then they were buried in the middle of Sri Sajjanalai, and a cetiya was built on top of them which was finished in six years. A wall of rock enclosing Phra Mahadhatu was built which was finished in three years.

Formerly these Thai letters did not exist. In 1205 saka, a year of the goat, King Ramkamhaeng set his mind and his heart on devising these Thai letters. So these Thai letters exist because that lord devised them.

King Ramkhamhaeng is sovereign over all the Thai. He is the teacher who teaches all the Thai to understand merit and Dhamma rightly. Among men who live in the lands of the Thai, there is no one to equal him in knowledge and wisdom, in bravery and courage, in strength and energy. He is able to subdue a throng of enemies and possesses broad kingdoms and many elephants.

The places whose submission he receives on the east include Sra Luang Song Kwae, Lumbachai, Sakha, the banks of the Khong, Wiangchan and Wiangkham, which is the farthest place; on the south they include Khonthi, Phra Bang, Phraek, Suphannaphum, Ratchaburi, Phetchburi, Sri Dhammaraja, and the seacoast, which is the farthest place; on the west, they include Muang Chot, Muang …n, Hongsawadi, the seas being their limit; on the north, they include Muang Phrae, Muang Man, Muang N., Muang Phlua and, beyond the banks of the Khong, Muang Chawa, which is the farthest place. All the people who live in these lands have been reared by him in accordance with the Dhamma, every one of them.Scholarly Resources

THE INSCRIPTION OF KING RAMKAMHAENG THE GREAT. Edited by Chulalongkorn University on the 700th Anniversary of the Thai Alphabet.

This edition of the inscription includes a fold-out poster of the original script and an English translation. Our version here is a slight modification of this edition."

[Quelle der Übersetzung: http://www.thaibuddhism.net/face1.htm ff. -- Zugriff am 2013-01-14]

1833

Die Puffmutter Großmutter (mütterlicherseits) Faeng (ยายแฟง) lässt Wat Khanikaphon (วัดคณิกาผล = Kloster "Resultat der Huren") = Wat Mai Yai Faeng (วัดใหม่ยายแฟง) erbauen.

| "Wat Khanikphon (Thai:

วัดคณิกาผล) is

a Thai private temple (วัดราษฎร์) in Maha Nikaya (มหานิกาย) sect

of Buddhism[1],

located on Thanon Phlapphla Chai (ถนนพลับพลาไชย),

Khwaeng Pom Prap (แขวงป้อมปราบ), Khet Pom Prap Sattru Phai (เขตป้อมปราบศัตรูพ่าย),

Bangkok, in front of the Phlapphla Chai Police Office (โรงพักพลับพลาไชย). During the reign of King Nang Klao, a rich old woman whose name was Faeng (แฟง), often called Madam Faeng by the public, was a faithful Buddhist, despite being a manager of a brothel, called "Madam Faeng's Station (โรงยายแฟง)," situated on Thanon Yaowarat (ถนนเยาวราช). The old woman raised funds amongst the prostitutes in her brothel to build the temple in 1833.[1][3] In celebrating the temple, Madam Faeng invited Father To (ขรัวโ), a renown monk who later obtained an ecclesiastical title as Somdet Phra Phutthachan (To Phrommarangsi) (สมเด็จพระพุฒาจารย์ - โต พฺรหฺมรํสี) (1788 - 1872), to deliver a sermon, hoping that the monk would praise her contributions amongst the public. Father To addressed the public that the merits made by one for displaying his own virtue, even great in amount, would result in low goodness. The monk also said that the prostitution incomes which Madam Faeng spent in building the temple were considered the 'sinful money', it was regarded that Madam Faeng made the incomplete contributions, stating that "These charitable activities of the host are of various backgrounds. It is therefore considered that in making one pound of contribution, Madam Faeng would gain only one shilling of merit."[3][4] Originally, there was no official name of the temple. The people merely called the temple "Madam Faeng's Temple" (วัดใหม่ยายแฟง, literally 'New Temple by Madam Faeng').[1] As from its establishment, the temple has been opened to the public and a site of public religious activities. When King Chulalongkorn ascended to the throne, Madam Faeng's descendants renovated the temple and petitioned the King for its official name. King Chulalongkorn named the temple "Khanikaphon," from Pāḷi, Gaṇikābala, meaning the temple which was the result of the prostitutes' contributions.[1] Currently, the temple maintains many items existing since its establishment, including the presiding Buddha image, the central hall, the image halls, a small pagoda, the cloisters, the masonic bell tower, and the ancient file cabinet. There are also a model of Father To in front of the temple, and a half figure of Madam Faeng covered with gold leaves and placed inside the wall. On the base of the Madam Faeng figure, there is an inscription: "This Wat Khanikaphon was established in 1833 by Madam Faeng, ascendant of the Paorohit Family." ("วัดคณิกาผลนี้สร้างเมื่อพุทธศักราช 2376 โดยคุณยายแฟง บรรพบุรุษของตระกูลเปาโรหิตย์")[5] The temple also runs a primary school called "Wat Khanikaphon School," (โรงเรียนวัดคณิกาผล) subsidiary to the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration." [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wat_Khanikaphon. -- Zugriff am 2013-03-04] |

Abb.: Wat

Khanikaphon (วัดคณิกาผล) = Wat Mai Yai Faeng (วัดใหม่ยายแฟง)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1833

In Nakhon Khuan Khan (นครเขื่อนขันธ์ = Phra Pradaeng - พระประแดง) können die meisten Männer Thai und Burmesisch sprechen, wenige können lesen. Die Burmesisch-Kenntnisse reichen für den Geschäftsverkehr. Zwei Drittel der Männer können Mon lesen. Frauen können Thai sprechen, nur wenig Frauen verstehen Burmesisch.

Abb.: Lage von Nakhon Khuan Khan (นครเขื่อนขันธ์ = Phra Pradaeng -

พระประแดง)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1833

The Government of India Act 1833 beendet die kommerziellen Tätigkeiten der East India Company

"The Saint Helena Act 1833[1] or The Government of India Act 1833[2] (3 & 4 Will 4 c 85) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. As this Act was also meant for an extension of the royal charter granted to the company it is also called the Charter Act of 1833.[3] Even this extended the charter by 20 years. It contained the following provisions:

- It made the Governor-General of Bengal as the Governor-General of India. Lord William Bentick was the first Governor-General of India.

- It deprived the Governor of Bombay and Madras of their legislative powers. The Governor-General was given exclusive legislative powers for the entire British India.

- It ended the activities of the Company as a commercial body and became a purely administrative body.

- It attempted to introduce a system of open competitions for the selection of civil servants. However this provision was negated after opposition from the Court of Directors who were still holding the privilege of appointing the companies officials."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Helena_Act_1833. -- Zugriff am 2013-06-13]

1833

Es erscheint

Beaumont, William <1785 - 1853>: Experiments and observations on the gastric juice and the physiology of digestion. -- Plattsburgh : Allen, 1833. -- 280 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm

Abb.: Titelblatt

"Als am 6. Juni 1822 der frankokanadische Trapper Alexis St. Martin mit einer Schrotflinte in den Magen getroffen wurde, leitete Dr. Beaumont die Erstversorgung ein. Der Trapper überlebte mit einer Fistel im Magen. Beaumont begann seine Experimente über die Verdauung, in dem er Speisen an Fäden durch die offene Hautfalte in den Magen ließ und die Veränderungen nach ein paar Stunden beobachtete. Er entnahm eine Probe des Magensaftes und analysierte diese chemisch. Seine Forschung kamen zu dem Ergebnis, dass die Nahrung nicht durch eine Lebenskraft, sondern durch Magensaft verarbeitet wurden. Nach einer zweijährigen, unerlaubten Abwesenheit, in der St. Martin in Kanada heiratete und zwei Kinder bekam, machte ihn Beaumont ausfindig und überredete ihn, das Experiment ab 1829 gegen eine vertraglich festgelegte Bezahlung einschließlich Unterkunft und Essen fortzusetzen. In den nächsten fünf Jahren erfolgten, manchmal täglich, weitere Experimente, die Beaumont zu Berühmtheit in der Fachwelt verhalfen, jedoch ohne St. Martin zu erwähnen. 1833 publizierte Beaumont über seine Forschungen."

[Quelle: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Beaumont. -- Zugriff am 2015-10-26]

1833

Das Segelschiff Tuscany transportiert 180 Tonnen Eis von den Großen Seen von Boston (USA) nach Kolkata (কলকাতা, Indien), 100 Tonnen kommen in einwandfreiem Zustand an.

Abb.: Lage von Boston und Kolkata (কলকাতা)

[Bildquelle: CIA. -- Public domain]

1833-01-06

Der vietnamesische Kaiser Minh Mạng (明命, 1791 - 1841) befiehlt per Edikt den Katholiken, vom Glauben abzufallen und ihre Kirchen zu verbrennen. Dies führt dazu, dass die Katholiken die Lê Văn Khôi Revolte (1833–1835) unterstützen.

"The Lê Văn Khôi revolt (1833–1835) was an important revolt in 19th century Vietnam, in which southern Vietnamese, Vietnamese Catholics, French Catholic missionaries and Chinese settlers under the leadership of Lê Văn Khôi (黎文𠐤, - 1834)) opposed the Imperial rule of Minh Mạng (明命, 1791 - 1841). Origin

The revolt was spurred by the prosecutions launched by Minh Mạng against southern factions which had opposed his rule and tended to be favourable to Christianity. In particular, Minh Mạng prosecuted Lê Văn Duyệt (黎文悅, 1763/64 - 1832), a former faithful general of Emperor Gia Long (嘉隆, 1762 - 1820), who had opposed his enthronement.[4] Since Lê Văn Duyệt had already died earlier in 1832, his tomb was profaned, and inscribed with the words "This is the place where the infamous Lê Văn Duyệt was punished".[2]

Start of the revoltLê Văn Khôi, the adoptive son of general Lê Văn Duyệt, had also been imprisoned, but managed to escape on 10 May 1833.[2] Soon, numerous people joined the revolt, in the desire to avenge Lê Văn Duyệt and challenge the legitimacy of the Nguyễn Dynasty (阮朝).[5]

Catholic supportLê Văn Khôi declared himself in favour of the restoration of the line of Prince Cảnh (阮福景, 1780 - 1801), the original heir to Gia Long according to the rule of primogeniture, in the person of his remaining son An-hoa.[6] This choice was designed to obtain the support of Catholic missionaries and Vietnamese Catholic, who had been supporting with Lê Văn Duyệt the line of Prince Cảnh.[6] Lê Văn Khôi further promised to protect Catholicism.[6]

On 18 May 1833, the rebels managed to take the Citadel of Saigon (Thanh Phien-an, 嘉定城).[6] Lê Văn Khôi was able to conquer six provinces of Gia Dinh (嘉定省) in the span of one month.[2] The main actors of the revolt were Vietnamese Christians and Chinese settlers who had been suffering from the rule of Minh Mạng.[5]

Siamese supportAs Minh Mạng raised an army to quell the rebellion, Lê Văn Khôi fortified himself into the Saigon fortress, and asked for the help of the Siamese.[2] Rama III, king of Siam, accepted the offer and sent troops to attack the Vietnamese provinces of Ha-tien (Thị xã Hà Tiên/市社河僊) and An-giang (Tỉnh An Giang/省安江) and Vietnamese imperial forces in Laos and Cambodia.[6] The Siamese troops were accompanied by 2,000 Vietnamese Catholic troops under the command of Father Nguyen Van Tam.[1] These Siamo-Vietnamese forces were repelled in summer 1834 however by General Truong Minh Giang.[7] Lê Văn Khôi died in 1834 during the siege and was succeeded by his 8-year-old son Le Van Cu.[2]

Defeat and repressionIt took three years for Minh Mạng to quell the rebellion and the Siamese offensive. When the fortress of Phien An was invested in September 1835,[6] 1,831 people were executed and buried in mass graves (now situated in 3rd District, Saigon).[2] Only 6 survivors were temporarily spared,[8] among whom were Le Van Cu, but also the French missionary Father Joseph Marchand (1803 - 1835), of the Paris Foreign Missions Society (Société des Missions étrangères de Paris). Marchand had apparently been supporting the cause of Lê Văn Khôi, and asked for the help of the Siamese army, through communications to his counterpart in Siam, Father Taberd (Jean-Louis Taberd , 1794–1840). This revealed the strong Catholic involvement in the revolt[2] Father Marchand was tortured and executed on 5 November 1835, as was the child Le Van Cu.[2]

The failure of the revolt had a disastrous effect on the Christian communities of Vietnam.[5] New waves of persecutions against Christians followed, and demands were made to find and execute remaining missionaries.[1] Anti-Catholic edicts to this effect were issued by Minh Mạng in 1836 and 1838. In 1836–1838 six missionaries were executed: Ignacio Delgado (1761 - 1838), Dominico Henares (1865 - 1838), Jean-Charles Cornay (1809 – 1837), José Fernández (1775 - 1838), François Jaccard (1799 - 1838), and Bishop Pierre Borie (Pierre-Rose-Ursule Dumoulin-Borie, 1808 – 1838)."

[Quelle: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/L%C3%AA_V%C4%83n_Kh%C3%B4i_revolt. -- Zugriff am 2017-01-10]

1833-02-18 - 1833-04-06

Edmund Roberts (1784 - 1836) weilt aus Gesandter von US-Präsident Andrew Jackson (1767 - 1845) in Siam.

Roberts, ein Schiffseigner und Händler aus Portsmouth hatte zusammen mit John Shillaber, den US-Konsul in Batavia (heute Jakarta) bei US-Präsident Andrew Jackson lobbyiert, dass dieser eine Gesandtschaft nach Siam schickt. Jackson schickt Roberts.

Roberts kommt 1833-02-18 in Bangkok auf dem Kriegsschiff USS Peacock (1828 - 1841) von Long Island (New York) kommend an.

Roberts handelt mit Dit Bunnag (ดิศ บุนนาค, 1788–1855) einen Handels- und Freundschaftsvertrag (Treaty of Amity and Commerce) zwischen den USA und Siam aus.

1833-03-18 erhält Roberts eine Audienz bei Rama III.

Der Vertrag wird 1833-03-20 unterschrieben.

Der US-Senat ratifiziert den Vertrag am 1835-01-03.

Dit Bunnag gibt Roberts eine lange Liste von Geschenken mit, die Rama III. von den USA wünscht.

Roberts kehrt 1836-04 nach Siam mit der Ratifikationsurkunde und Geschenken zurück.

Abb.: Andrew Jackson

Abb.: USS Peacock (1828 - 1841)

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb..: Treaty of Amity and Commerce 1833

[Bildquelle: http://www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/2013/nr13-135.html. -- Zugriff am 2015-03-16]Roberts war am 1833-03-08 mit USS Peacock (1828) nach Siam gekommen.

"Meanwhile, the United States Government endeavoured on its own account to enter into diplomatic relations with Siam. In 1833 Mr. Edmund Roberts was despatched by the Washington authorities to Bangkok with instructions to conduct negotiations for a commercial treaty. Mr. Roberts was indefatigable in his endeavours to secure privileges for his countrymen, but the Siamese Government resolutely declined to make any greater concessions than had been granted to Great Britain, and he had to be content with a colourless treaty conferring some worthless privileges upon American traders. A particular request made by Mr. Roberts for liberty for a United States consul to reside in Siam was refused on the ground that a similar application put forward by the British Government had not been entertained. In point of fact, both the treaty of Bangkok [mit der britischen East India Company] and its American prototype were practically useless. The American ship Sachem was the only vessel that attempted to trade under the United States treaty, and her experiences were so discouraging that she did not pay a second visit to Siam."

[Quelle: Arnold Wright in: Twentieth century impressions of Siam : its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources / ed. in chief: Arnold Wright. -- London [etc.] : Lloyds, 1908. -- S. 58]

"The treaty has removed all obstacles to a lucrative and important branch of our commerce ; the merchant being left free to sell or purchase where and of whom he pleases. Prior to this period, the American merchant was not allowed to sell to a private individual the cargo he imported, nor purchase a return cargo. The king claimed the exclusive right of purchase and sale in both cases; and furthermore, such parts of the imported cargoes as were most saleable, were selected and taken at his own valuation, which was always at prices far below the market value, as profit was the sole object in making the purchases. Secondly: he also fixed the prices of the articles wanted for return cargoes, and no individual dared offer any competition either in buying or selling.

Thirdly: the American merchant not only did not obtain a fair value for his merchandise, but it is notorious that he had to pay from twenty to thirty per cent, more for the produce of the country than he could have purchased it for from private hands.

Fourthly: the vexations occasioned by delay were a matter of serious complaint. It was no uncommon circumstance to be delayed from two to four months beyond the stipulated time. The loss sustained, say for three months' charter, and interest on the capital employed for that time, &c., &c., amounted to several thousand dollars. In addition to all these evils the merchant was frequently obliged to take payment in inferior articles, at the highest market value for the best, and even unsaleable merchandise at high prices.

Fifthly: the duties on imports were not permanent; they varied from eight to fifteen per centum.

Sixthly: the export duty on sugar of the first quality, was one dollar and a half (Spanish) per pecul, which was not less than from 20 to 30 per centum upon the first cost, and other articles were charged in the same proportion.

Seventlily: port-charges and other exactions were not defined and fixed, but they generally amounted to not less than three and a half (Spanish) dollars per ton.

Eighthly: Presents were expected, and in fact exacted, from the king to the lowest custom-house officer, according to the usages of Asiatics; there were but a few vessels that did not pay upward of a thousand dollars, if they had a valuable cargo."

[Quelle: Roberts, Edmund <1784 - 1836>: Embassy to the eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat; in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock, David Geisinger, Commander, during the years 1832-3-4. -- New York : Harper, 1837. -- 432 S. -- S. 314ff.]

Text des Vertrags:

"Treaty signed at Bangkok March 20, 1833

Senate advice and consent to ratification June 30, 1834

Ratified by the President of the United States January 3, 1835

Ratified by Siam April 14, 1836

Ratifications exchanged at Bangkok April 14, 1836

Entered into force April 14, 1836

Proclaimed by the President of the United States June 24, 1837 Modified by treaty of May 29, 1856

Replaced September 1, 1921, by treaty of December 16, 1920

8 Stat. 454; Treaty Series 321Treaty of Amity and Commerce between His Majesty the Magnificent King of Siam and the United States of America

His Majesty the Sovereign and Magnificent King in the City of Sia-Yut'hia, [ศรีอยุธยา] has appointed the Chau Phaya-Phraklang [เจ้าพระคลัง], one of the first Ministers of State, to treat with Edmund Roberts, Minister of the United States of America, who has been sent by the Government thereof, on its behalf, to form a treaty of sincere friendship and entire good faith between the two nations. For this purpose the Siamese and the citizens of the United States of America shall, with sincerity, hold commercial intercourse in the Ports of their respective nations as long as heaven and earth shall endure.

This Treaty is concluded on Wednesday, the last of the fourth month of the year 1194, called Pi-marong-chat-tavasok [ปีมะโรง], or the year of the Dragon, corresponding to the 20th day of March, in the year of our Lord 1833. One original is written in Siamese, the other in English; but as the Siamese are ignorant of English, and the Americans of Siamese, a Portuguese and a Chinese translation are annexed, to serve as testimony to the contents of the Treaty. The writing is of the same tenor and date in all the languages aforesaid. It is signed on the one part, with the name of the Chau Phaya-Phraklang, and sealed with the seal of the lotus flower, of glass. On the other part, it is signed with the name of Edmund Roberts, and sealed with a seal containing an eagle and stars.

One copy will be kept in Siam, and another will be taken by Edmund Roberts to the United States. If the Government of the United States shall ratify the said Treaty, and attach the Seal of the Government, then Siam will also ratify it on its part, and attach the Seal of its Government.

Article I

There shall be a perpetual Peace between the Magnificent King of Siam and the United States of America.

Article II

The Citizens of the United States shall have free liberty to enter all the Ports of the Kingdom of Siam, with their cargoes, of whatever kind the said cargoes may consist; and they shall have liberty to sell the same to any of the subjects of the King, or others who may wish to purchase the same, or to barter the same for any produce or manufacture of the Kingdom, or other articles that may be found there. No prices shall be fixed by the officers of the King on the articles to be sold by the merchants of the United States, or the merchandise they may wish to buy, but the Trade shall be free on both sides to sell, or buy, or exchange, on the terms and for the prices the owners may think fit. Whenever the said citizens of the United States shall be ready to depart, they shall be at liberty so to do, and the proper officers shall furnish them with Passports: Provided always, there be no legal impediment to the contrary. Nothing contained in this Article shall be understood as granting permission to import and sell munitions of war to any person excepting to the King, who, if he does not require, will not be bound to purchase them; neither is permission granted to import opium, which is contraband; or to export rice, which cannot be embarked as an article of commerce. These only are prohibited.

Article III

Vessels of the United States entering any Port within His Majesty's dominions, and selling or purchasing cargoes of merchandise, shall pay in lieu of import and export duties, tonnage, licence to trade, or any other charge whatever, a measurement duty only, as follows: The measurement shall be made from side to side, in the middle of the vessel's length; and, if a single-decked vessel, on such single deck; if otherwise, on the lower deck. On every vessel selling merchandise, the sum of 1700 Ticals, or Bats, shall be paid for every Siamese fathom in breadth, so measured, the said fathom being computed to contain 78 English or American inches, corresponding to 96 Siamese inches; but if the said vessel should come without merchandise, and purchase a cargo with specie only, she shall then pay the sum of 1,500 ticals, or bats, for each and every fathom before described. Furthermore, neither the aforesaid measurement duty, nor any other charge whatever, shall be paid by any vessel of the United States that enters a Siamese port for the purpose of refitting, or for refreshments, or to inquire the state of the market.

Article IV

If hereafter the Duties payable by foreign vessels be diminished in favour of any other nation, the same diminution shall be made in favour of the vessels of the United States.

Article V

If any vessel of the United States shall suffer shipwreck on any part of the Magnificent King's dominions, the persons escaping from the wreck shall be taken care of and hospitably entertained at the expense of the King, until they shall find an opportunity to be returned to their country; and the property saved from such wreck shall be carefully preserved and restored to its owners; and the United States will repay all expenses incurred by His Majesty on account of such wreck.

Article VI

If any citizen of the United States, coming to Siam for the purpose of trade, shall contract debts to any individual of Siam, or if any individual of Siam shall contract debts to any citizen of the United States, the debtor shall be obliged to bring forward and sell all his goods to pay his debts therewith. When the product of such bona fide sale shall not suffice, he shall no longer be liable for the remainder, nor shall the creditor be able to retain him as a slave, imprison, flog, or otherwise punish him, to compel the payment of any balance remaining due, but shall leave him at perfect liberty.

Article VII

Merchants of the United States coming to trade in the Kingdom of Siam and wishing to rent houses therein, shall rent the King's Factories, and pay the customary rent of the country. If the said merchants bring their goods on shore, the King's officers shall take account thereof, but shall not levy any duty thereupon.

Article VIII

If any citizens of the United States, or their vessels, or other property, shall be taken by pirates and brought within the dominions of the Magnificent King, the persons shall be set at liberty, and the property restored to its owners.

Article IX

Merchants of the United States, trading in the Kingdom of Siam, shall respect and follow the laws and customs of the country in all points.

Article X

If thereafter any foreign nation other than the Portuguese shall request and obtain His Majesty's consent to the appointment of Consuls to reside in Siam, the United States shall be at liberty to appoint Consuls to reside in Siam, equally with such other foreign nation.

Whereas, the undersigned, Edmund Roberts, a citizen of Portsmouth, in the State of New Hampshire, in the United States of America, being duly appointed as Envoy, by Letters Patent, under the Signature of the President and Seal of the United States of America, bearing date at the City of Washington, the 26th day of January, in the year of our Lord 1832, for negotiating and concluding a Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the United States of America and His Majesty, the King of Siam.

Now know ye, that I, Edmund Roberts, Envoy as aforesaid, do conclude the foregoing Treaty of Amity and Commerce, and every Article and Clause therein contained; reserving the same, nevertheless, for the final Ratification of the President of the United States of America, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate of the said United States.

Done at the Royal City of Sia-Yut'hia (commonly called Bangkok), on the 20th day of March, in the year of our Lord 1833, and of the Independence of the United States of America the 57th.

Edmund Roberts"

[Quelle: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Amity_and_Commerce_between_Siam_and_the_United_States,_1833. -- Zugriff am 2015-03-16]

Roberts nennt folgende Zahlen zum Staatshaushalt Siams:

Abb.: Annual revenue obtained by the Government of Siam from farms and duties (1)

Abb.: Annual revenue obtained by the Government of Siam from farms and duties (2) ; Expenditure[Quelle der beiden Abbildungen: Roberts, Edmund <1784 - 1836>: Embassy to the eastern courts of Cochin-China, Siam, ans Muscat; in the U. S. sloop-of-war Peacock, David Geisinger, Commander, during the years 1832-3-4. -- New York : Harper, 1837. -- 432 S. -- S. 426f.]

Rama IV. sendet dem Präsidenten der USA u.a. folgende Geschenke:

""Yesterday and today a variety of presents was sent to the Envoy, from the Chao Phia Phra Klang (sic) [the Thai equivalent of foreign minister]. They consisted of

- elephant's teeth (sic) [tusks],

- sugar (nam tan) [น้ำตาล],

- sugar-candy,

- pepper,

- cardammus [Amomum krervanh, or Elettaria sp.] (krawan) [กระวาน]

- gambooge (sic) [Garcinia hanburyi] (rong tong), [รงทอง]

- agila [Aquilaria agallocha] (maykrisana), [ไม้กฤษณา]

- sopan [sapanwood (Caesalpinia sappan) used for red and violet dye, but also used medicinally throughout Southeast Asia] wood (sic) (mayfang), [ไม้ฝาง]

- etc. "

[Roberts. -- Zitiert in: http://www.mnh.si.edu/treasures/frame_exhibit_gallery1_main.htm. -- Zugriff am 2015-03-16]

Die Gesandtschaft von Roberts ist erstaunt, dass die zwölfjährige Tochter des Gouverneurs von Paknam (ปากน้ำ, heute Samut Prakan - สมุทรปราการ) splitternackt herumläuft und eine Zigarre pafft. Jedermann, selbst Kleinkinder, raucht. Der König und sein Hof raucht vor allem Tabak aus Kanchanaburi (กาญจนบุรี) und Phetchaburi (เพชรบุรี).

Abb.: Lage von Paknam (ปากน้ำ, heute Samut Prakan - สมุทรปราการ), Kanchanaburi (กาญจนบุรี) und Phetchaburi (เพชรบุรี)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1833-03-25

Der US-amerikanische protestantische Missionar John Taylor Jones (1802 – 1851), seine Frau Eliza Grew Jones (1803 – 1838) und ihr Pflegekind Samuel Jones Smith (1820 - 1909) kommen nach Siam.

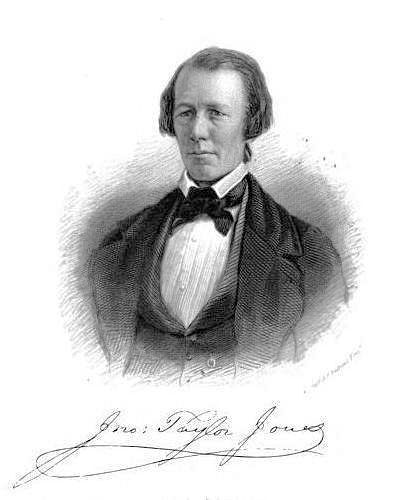

Abb.: John

Taylor Jones

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Eliza Grew Jones, 1842

[Bildquelel: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

|

"Rev. Dr. John Taylor Jones

(July 16, 1802 – September 13, 1851) was one of the earliest Protestant

missionaries to Siam (now Thailand) with his wife, Eliza Grew Jones (1803 -

1838). He is credited with introducing to Siam the modern world map,[1][2]

and producing a translation of the New Testament in Siamese

(Thai) from Greek. Biography Jones was born in New Ipswich, New Hampshire, on July 16, 1802, to Elisha and Persia Taylor Jones. He attended preparatory school at New Ipswich Academy and Bradford Academy. He attended Brown College from 1819–1820, and worked as a teacher from 1820-1823. He graduated from Amherst College in 1825, and undertook graduate studies at Andover Theological Seminary from 1827–1830, and then at Newton Theological Institution in 1830.[3] He married Eliza Grew Jones on July 14, 1830, and was ordained in Boston on July 28, 1830, as a missionary to Burma under the American Baptist Missionary Union (ABMU). He and his wife set sail for the country shortly thereafter. Rev. and Mrs. Jones worked with Adoniram Judson (1788 - 1850) in Burma, residing for about two years at Maulmein (မော်လမြိုင်မြို့), and later at Rangoon (ရန်ကုန်).[4]:pp.267-8 After Karl Gützlaff (1803 - 1851) petitioned the ABMU for more missionaries, the Rev. and Mrs. Jones were reassigned to Siam in 1832. Destined to became the first long-term Protestant missionaries in the country, they arrived in April 1833 on the schooner Reliance owned by the Reverend Robert Hunter, who was a friend of the Siamese foreign minister (known only by his office, that of praklang - พระคลัง.) Rev. Hunter had interceded with him on behalf of Rev. Gützlaff, who, in an excess of zeal, offended the Siamese within the first two days of his arrival by throwing thousands of tracts into many cottages, and every floating house, boat and junk– following which he was ordered expelled and his tracts burnt. Rev. Hunter persuaded the praklang to have the tracts translated for the king to read. The king found nothing objectionable in them, but said candidly and openly that he preferred his own religion.[4]:p.269 The Rev. and Mrs. Jones were made welcome in the accommodations of the embassy of diplomatist Edmund Roberts (1784 - 1836) until their own could be made ready. Rev. Hunter introduced Rev. Jones to the praklang, who received him with apparent kindness, likely because they were American citizens. Roberts, indeed, had been told American negotiations for a treaty were proceeding at an unprecedented pace. Rev. Jones informed Roberts that Major Burney (1792 - 1845), the British ambassador at the court of Ava (အင်းဝမြို့) who had six years previously negotiated the Burney Treaty, told Rev. Jones that Americans were decidedly preferred to any other foreigners.[4]:p.269 The praklang sent down a boat to convey Rev. Jones and his family to their new residence at Cokai, which had been arranged by the French-, English-, and Siamese=speaking Portuguese consul Mr. Silveiro, near a campong [settlement] of Burmese. The residence had been previously occupied by a Mr. Abeel, another American missionary, of whom Roberts writes:

Rev. Jones' proselytizing work was primarily with the Chinese in Bangkok. He founded a Chinese Baptist church in 1835. His first baptism was the re-baptism of Boon Tee, a Chaozhou (潮州)) Chinese who had previously been baptized by Gützlaff, but not by immersion[5] Eliza Jones died of cholera at Bangkok on March 28, 1838. Rev. Jones remarried in November 1840, to Judith Leavitt. She died on March 21, 1846. He was married for a third and final time on August 20, 1847, to Sarah Sleeper (b. Gilford, New Hampshire, 1812-05-12 - d. Bangkok, 1889-04-30) who, after Jones' death in 1851, had in turn married Rev S.J. Smith on 1853-10-26. Sleeper served 42 years as a missionary in Bangkok[6] Jones died on 1851-09-13. He is buried at the Bangkok Protestant Cemetery. Works

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Taylor_Jones. -- Zugriff am 2013-02-06] |

|

Eliza Grew Jones (March 30, 1803 –

March 28, 1838) is noted for having created a romanized script for writing the

Siamese language, and for creating the first Siamese-English dictionary. Biography Born Eliza Grew to Rev. Henry Grew, Jones was a native of Providence, Rhode Island. Presaging her future accomplishments, an early school teacher noted that she had an unusual ability in languages, learning Greek without the aid of a teacher. She married Rev. Dr. John Taylor Jones on July 14, 1830.[4] Her husband was ordained in Boston two weeks later under the American Baptist Missionary Union, and the couple was then assigned to work in Burma. Her first large work was a Siamese-English dictionary that she completed in December 1833, after she had been transferred to Siam. It was not published due to the difficulty of printing with Siamese type. No extant copy is known to exist. Later, she also created a romanized script for writing the Siamese language. She wrote portions of Biblical history in Siamese. In Burma and Thailand, she gave birth to four children, two of whom died in childhood. Jones died in Bangkok of cholera on March 28, 1838. She is buried in the Bangkok Protestant Cemetery. [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eliza_Grew_Jones. -- Zugriff am 2015-04-01] |

1833

Der Reutlinger Wirtschaftwissenschaftler Daniel Friedrich List (1789 - 1846) veröffentlicht die kostenlose Schrift „Ueber ein sächsisches Eisenbahnsystem als Grundlage eines allgemeinen deutschen Eisenbahnsystems und insbesondere über die Anlegung einer Eisenbahn von Leipzig nach Dresden“, Leipzig 1833. "Darin hat List die wirtschaftlichen Vorteile einer solchen Bahn klar dargelegt: Danach ermögliche die Eisenbahn einen billigen, schnellen und regelmäßigen Massentransport, der förderlich für die Entwicklung der Arbeitsteilung, die Standortwahl gewerblicher Betriebe und letztlich einen höheren Absatz der Produkte sei." (Wikipedia).

Abb.: Lists Entwurf eines Eisenbahnsystems für Deutschland 1833

[Bildquelel: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

1833-11 - 1834-02

Rebellion in Cochin-China. Die Rebellen bitten Siam um Unterstützung bei der Trennung von Annam. Siam schickt Truppen (40.000 Mann). Nach anfänglichen Erfolgen wird Siam geschlagen und zieht seine Truppen zurück. Annam hat nun sieben Jahre lang freie Hand in Kambodscha.

Abb.: Lage von Annam und Cochin-China 1886

[Bildquelle: Map of Indo-China showing proposed Burma-Siam-China Railway. -- In: Scottish Geographical Magazine. -- 2 (1886)]Chantaburi (จันทบุรี) wird Garnisonsstadt für den Krieg in Kambodscha.

Abb.: Lage von Chantaburi (จันทบุรี)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

ausführlich: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/ressourcen.htm