Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Chronik Thailands = กาลานุกรมสยามประเทศไทย. -- Chronik 1874 (Rama V.). -- Fassung vom 2017-01-28. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/chronik1874.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2013-09-10

Überarbeitungen: 2017-01-28 [Ergänzungen] ; 2017-01-11 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-04-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-12-27 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-09-27 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-09-15 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-08-22 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-04-29 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-04-02 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-24 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-12-17 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-11-12 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-09-27 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Herausgebers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Thailand von

Tüpfli's Global Village Library

ช้างตายทั้งตัวเอาใบบัวปิดไม่มิด

|

Gewidmet meiner lieben Frau Margarete Payer die seit unserem ersten Besuch in Thailand 1974 mit mir die Liebe zu den und die Sorge um die Bewohner Thailands teilt. |

|

Bei thailändischen Statistiken muss man mit allen Fehlerquellen rechnen, die in folgendem Werk beschrieben sind:

Die Statistikdiagramme geben also meistens eher qualitative als korrekte quantitative Beziehungen wieder.

|

1874

Royal Ordinance for the Finance Office.

1874

Gründung der Königlichen Siamesischen Armee. Der König bezweckt damit

"An adequate [...] force to put down unlawful persons within the country so that people might trade without hindrance from bandits and dangers." [Übersetzung: Battye, Noel Alfred <1935 - >: The military, government, and society in Siam, 1868-1910 : politics and military reform during the reign of King Chulalongkorn. -- 1974. -- 575 S. -- Diss., Cornell Univ. -- S. 132f.]

1874

Einrichtung eines Militärgerichtshofs

1874

Siam stationiert in Chiang Mai (เชียงใหม่) erstmals einen Kommissar. Beginn des Endes von Lan Na (ล้านนา) als selbständigem, Siam tributpflichtigem Staat. 1877 wird der Kommissar auch zuständig für Lampang (ลำปาง), Lamphun (ลำพูน), Phrae (แพร่) und Nan (น่าน).

"The timing of the creation and the siting of commissionerships were determined by specific pressures on the country. In 1874 the government created the commissionership of Chiangmai, which was the forerunner of the others, in order to forestall British intervention in the tributary states of the north. The possibility of such an event taking place had arisen as a result of the maladministration of forest concessions contracted between the local princes and Burmese citizens who came from British Lower Burma."

[Quelle: Tej Bunnag [เตช บุนนาค] <1943 - >: The provincial administration of Siam from 1892 to 1915 : a study off the creation, the growth, the achievements, and the implications for modern Siam, of the ministry of the interior under prince Damrong Rachanuphap. -- Diss. Oxford : St. Anthonys College, Michaelmas Term 1968. -- 429 S., Schreibmaschinenschrift. -- S. 101f.. -- Faire use]

"In another sphere of administration, the commissioners of Chiangmai intervened in the judicial autonomy of the Principality and thereby took the first step towards the centralization of the judicial administration of the tributary states. In 1874, the government was forced to establish a commissionership with special judicial responsibilities in Chiangmai in order to forestall British intervention in the north. The local princes themselves had made this necessary when, in 1871 there were disputes concerning timber rights between them and Burmese forest-concessionaires who came from British Burma. The Burmese, claiming the rights of extraterritoriality, took the cases down to the British Consular Court in Bangkok. During the course of the proceedings, the corruption in the administration of forest concessions was revealed and the princes lost eleven out of twenty one cases. After this event, Great Britain, by the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1874, made the Siamese government responsible for the adjudication of disputes between her Asian subjects without British papers and local citizens in Chiangmai, Lampang and Lamphun. The government, with the threat of British intervention hanging in the air, made the Chiangmai princes accept a commissioner, who was sent to carry out this arrangement. It was ironically as the caretaker of British extraterritorial rights that the government breached the judicial autonomy of a tributary state." [Quelle: Tej Bunnag [เตช บุนนาค] <1943 - >: The provincial administration of Siam from 1892 to 1915 : a study off the creation, the growth, the achievements, and the implications for modern Siam, of the ministry of the interior under prince Damrong Rachanuphap. -- Diss. Oxford : St. Anthonys College, Michaelmas Term 1968. -- 429 S., Schreibmaschinenschrift. -- S. 112f. -- Faire use]

1874

Der erste Gouverneur von Mae Hong Son (แม่ฮ่องสอน) lässt das Wat Phra That Doi Kong Mu (วัดพระธาตุดอยกองมู) bei Mae Hong Son erbauen.

Abb.: Lage von Mae Hong Son (แม่ฮ่องสอน)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Wat Phra That Doi Kong Mu (วัดพระธาตุดอยกองมู), 2011

[Bildquelel: Bessie and Kyle. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/bessieandkyle/5332974555/. -- Zugriff am 2012-05-01. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Wat Phra That Doi Kong Mu (วัดพระธาตุดอยกองมู), 2011

[Bildquelle: Nina. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/msnina/5592980932/. -- Zugriff am 2012-05-01. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

1874

Eröffnung des (öffentlichen) Nationalmuseums in Bangkok (พิพิธภัณฑสถานแห่งชาติ พระนคร)

"Das allererste Museum in Thailand wurde von König Mongkut (Rama IV.) eingerichtet. Er ließ 1862 auf dem Gelände des Großen Palastes ein Gebäude bauen, um seine Sammlung von Kunstobjekten und Antiquitäten aufzubewahren. Das Gebäude hieß „Prapat Bibidhabanda“ und stand auf dem Platz, an dem sich heute die „Sivilai Maha Prasat Halle“ befindet. Das erste öffentliche Museum ließ König Chulalongkorn (Rama V.) 1874 ebenfalls auf dem Palastgelände in der „Concordia Hall“, dem späteren „Sala Sahathai Samakhom“, einrichten. Nach dem Tode des letzten Uparat (มหาอุปราช) im August 1885 stand sein Palast, der so genannte „Vordere Palast“ (Phra Ratcha Wang Bowon Sathan Mongkon, Thai: พระราชวังบวรสถานมงคล - kurz Wang Na) leer. König Chulalongkorn ließ 1887 Ausstellungsstücke aus der Concordia Hall in den Wang Na transportieren, wo er die vorderen drei Gebäude als neuen Standort ausersah. Am 4. Dezember 1889 wurde durch ein königliches Dekret der Wang Na zum Museum erklärt unter der Schirmherrschaft des Erziehungs-Ministeriums. Zum Verwaltungsgebäude des soeben neu eingerichteten Ministeriums wurde 1892 das Gebäude des heutigen Nationaltheaters ernannt, welche ebenfalls auf dem Gebiet des ehemaligen Wang Na lag. Das Museum hatte zweimal in der Woche geöffnet. Es wurden Antiquitäten und Kunstobjekte ausgestellt, Kataloge wurden sowohl in Thai als auch in Englisch herausgegeben.

Am 19. April 1926 richtete König Prajadhipok (Rama VII.) das Royal Institute ein, und bestimmte Prinz Damrong Rajanubhab (สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ พระองค์เจ้าดิศวรกุมาร กรมพระยาดำรงราชานุภาพ, 1863 - 1942) zu seinem Präsidenten. Das Royal Institute siedelte sich im nördlichen Teil des Wang Na an, es übernahm anschließend die Verwaltung des „Bangkok Museum“, wie es ab sofort genannt wurde, und auch der „Bangkok Library“ (Bangkok Bibliothek). Die Gebäude des Museums wurden repariert und renoviert, so dass am 10. November 1926 zum Geburtstag des Königs die beiden neuen Institutionen in einer feierlichen Zeremonie eingeweiht werden konnten.

Im Laufe der Jahre befanden sich die Museumsgebäude in sehr schlechtem Zustand, so dass 1930 bereits Einsturz-Gefahr bestand. Da keine Mittel zur Verfügung standen, wurden zahlreiche Teakholz-Stämme benutzt, um die Dächer abzustützen. Nach dem Putsch von 1932 wurde am 3. Mai 1933 das Fine Arts Department (กรมศิลปากร, etwa: Ministerium der Schönen Künste) eingerichtet. Die Verwaltung des Bangkok Museum und der Vajiranyana Library wurde an das Ministerium übertragen. Gleichzeitig wurde das Bangkok Museum in „National Museum“ umbenannt, die Vajiranyana Library wurde zur „National Library“ (Nationalbibliothek).

Erst Anfang der 1950er Jahre konnten genug Mittel bereitgestellt werden, um die Gebäude des Museums zu reparieren und nach 20 Jahren die provisorischen Stützbalken zu entfernen. Die Restaurierung war erst 1952 abgeschlossen."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nationalmuseum_Bangkok. -- Zugriff am 2013-09-02]

1874 (1871?)

Die Regierung verbietet die Ausgabe von Pee-Geld (ปี้) durch Steuerpächter. Es sind über 2.000 Arten von Pee-Münzen im Umlauf.

Abb.: Pee (ปี้)

[Bildquelle: http://www.oknation.net/blog/home/user_data/file_data/201407/08/6852872f7.jpg. -- Zugriff am 2015-04-29. -- Fair use]

"ปี้ bpee³ n. counters (used in gambling) made of glass (green, white and yellow), porcelain and brass or bronze. During the period when gambling was a recognized institution, the small fuang [เฟื้อง = 1/8 Baht] and salung [สลึง = ¼ Baht] bullet-shaped coins were found inconvenient to handle. To overcome this the owners of gambling establishments introduced these special counters, on which were inscribed, in Chinese characters, the name of the establishment, the value, and a classical quotation, and in Thai characters the value which the counter was supposed to represent. These were issued, not by, but with the authority of the Government and, though originally intended only as gambling counters, rapidly became a favourite medium of exchange, for they were found to fill so well a long felt want for small money, so that the circulation went much beyond its legal sphere. The control by the Government became naturally more and more difficult, and at last in 1871 (three years after King Mongkut’s death) it became necessary to prohibit and stop completely all circulation of these counters (le May, J. S. S. XVIII, 3, p. 395)." [Quelle: McFarland, George Bradley <1866 - 1942>: Thai-English dictionary. -- 2. American printing. -- Stanford, CA : Stanford Univ. Pr., 1953. -- 1019 S. -- S. 527f.]

1874

Es erscheint

Bergen, Friedrich Ludwig Werner von <1839 - 1901>: The passive verb of the Thai language. -- Bangkok, 1874. -- 17 S. ; 20 cm. -- Der Autor ist Konsul des Deutschen Reichs in Siam.

1874

Es erscheint:

Leroy-Beaulieu, Paul <1843-1916>: De la colonisation chez les peuples modernes. -- Paris : Guillaumin, 1874. -- 616 S. ; 22 cm.

Es ist eine wirtschaftsliberale Rechtfertigung der imperialistischen Kolonisation.

1874

In Großbritannien werden die ersten Abwasserkläranlagen mit chemischen Ausfällstoffen und keimtötenden Chemikalien gebaut.

Abb.: Abwasserkläranlage, Ko Phi Phi, 2008

[Bildquelle: Bridget Coila. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/10897362@N00/2505424826. -- Zugriff am 2013-11-12. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1874

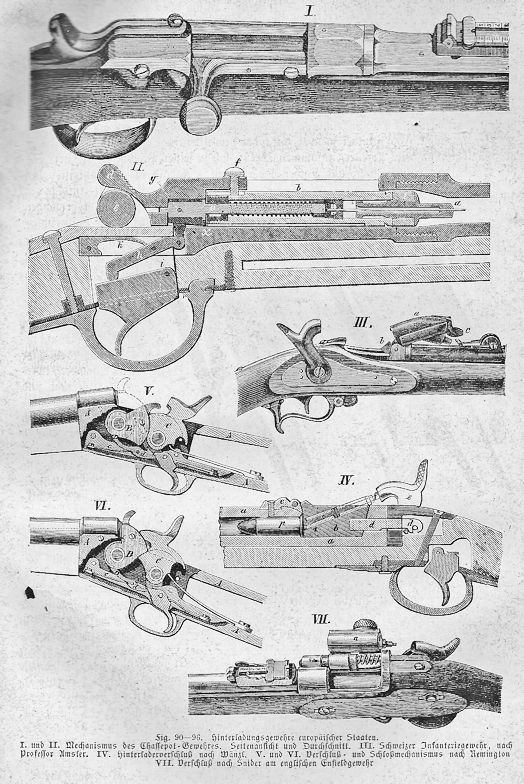

Abb.: Hinterladungsgewehre europäischer Staaten

[Bildquelle: Das Buch der Erfindungen. -- Bd. 6. -- 1874. -- S. 71]

1874

Es erscheint:

Galton, Francis <1822 - 1911>: English man of science : their nature and nurture. -- London : Macmillan, 1874. -- 270 S. -- Das Werk führt zur bis heute dauernden Diskussion über den Einfluss von Erbanlage und Umwelt (nature and nurture).

Abb.: Titelblatt

"PREFACE. I undertook the inquiry of which this volume is the result, after reading the recent work of M. de Candolle, in which he analyses the salient events in the history of 200 scientific men who have lived during the two past centuries, deducing therefrom many curious conclusions which well repay the attention of thoughtful readers. It so happened that I myself had been leisurely engaged on a parallel but more extended investigation—namely, as regards men of ability of all descriptions, with the view of supplementing at some future time my work on Hereditary Genius. The object of that book was to assert the claims of one of what may be called the “ pre-efficients ” of eminent men, the importance of which had been previously overlooked; and I had yet to work out more fully its relative efficacy, as compared with those of education, tradition, fortune, opportunity, and much else. It was therefore with no ordinary interest that I studied M. de Candolle’s work, finding in it many new ideas and much confirmation of my own opinions; also not a little criticism (supported, as I conceive, by very imperfect biographical evidence, ) of my published views on heredity. I thought it best to test the value of this dissent at once, by limiting my first publication to the same field as that on which M. de Candolle had worked—namely, to the history of men of science, and to investigate their sociology from wholly new, ample, and trustworthy materials. This I have done in the present volume; and I am confident that one effect of the evidence here collected will be to strengthen the utmost claims I ever made for the recognition of the importance of hereditary influence."

[a.a.O., S. V - VII]

"NATURE AND NURTURE. The phrase "nature and nurture" is a convenient jingle of words, for it separates under two distinct heads the innumerable elements of which personality is composed. Nature is all that a man brings with himself into the world; nurture is every influence from without that affects him after his birth. The distinction is clear: the one produces the infant such as it actually is, including its latent faculties of growth of body and mind; the other affords the environment amid which the growth takes place, by which natural tendencies may be strengthened or thwarted, or wholly new ones implanted. Neither of the terms implies any theory; natural gifts may or may not be hereditary; nurture does not especially consist of food, clothing, education or tradition, but it includes all these and similar influences whether known or unknown."

[a.a.O., S. 12]

1874-01-14

Vertrag zwischen dem britischen Govenment of India und Siam.

"NOTIFICATION - By Government of India Foreign Dept. The subjoined Treaty between the Government of India and the Siamese concluded at Calcutta [কলকাতা] on January 14, 1874, and duly ratified, is published for general information: -

Whereas the Government of India and the Siamese Government desire to conclude a Treaty for the purpose of promoting commercial intercourse between British Burmah and the adjoining territories of Chiangmai [เชียงใหม่], Lakon [= Lampang - ลำปาง,], and Lampoonchi [= Lamphun - ลำพูน], belonging to Siam, and of preventing dacoity and other heinous crimes in the territories aforesaid. The high contracting parties have for this purpose named and appointed their Plenipotentiaries, that is to say;

His Excellency the Right Honourable Thomas George Baring, Baron Northbrook of Stratton and a Baronet [1826 - 1904], Member of the Privy Council of Her Most Gracious Majesty the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, Grand Master of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India, Viceroy and Governor-General of India in Council, has on his part named and appointed

- Charles Umpherston Aitchison [1832 - 1896], Esquire, Companion of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India;

Abb.: Charles Umpherston Aitchison, 1896

[Bildquelle: Bourne & Shepard / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]and His Majesty

Somdetch Phra Paramindr Maha Chulalongkorn Bodindthong Depaya Maha Mongkut Purusaya Ratoreayyara-wiwongse Varutmawongse Pribat Warakattrya Raja Nikradom Chaduranta Porom Maha Chakrabantiray Songkat Poromdham Mik Maharaja Dhiray Poromnat Pobit Phra Chula Chom Klaw Chao Yuhua , Supreme King of Siam, fifth of the present Royal Dynasty, who founded the Great City of Bangkok Amratne Kodsindr Ayuthia,

[พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรมินทรมหาจุฬาลงกรณ์ บดินทรเทพยมหามงกุฏ บุรุษรัตนราชรวิวงศ วรุตมพงศบริพัตร์ วรขัติยราชนิกโรดม จาตุรันบรมมหาจักรพรรดิราชสังกาศ อุภโตสุชาติสังสุทธเคราะหณี จักรีบรมนาถ อดิศวรราชรามวรังกูร สุภาธิการรังสฤษดิ์ ธัญลักษณวิจิตรโสภาคยสรรพางค์ มหาชโนตมางคประนตบาทบงกชยุคล ประสิทธิสรรพศุภผลอุดม บรมสุขุมมาลย์ ทิพยเทพาวตารไพศาลเกียรติคุณอดุลยวิเศษ สรรพเทเวศรานุรักษ์ วิสิษฐศักดิ์สมญาพินิตประชานาถ เปรมกระมลขัติยราชประยูร มูลมุขราชดิลก มหาปริวารนายกอนันต มหันตวรฤทธิเดช สรรพวิเศษสิรินทร อเนกชนนิกรสโมสรสมมติ ประสิทธิ์วรยศมโหดมบรมราชสมบัติ นพปดลเศวตฉัตราดิฉัตร สิริรัตโนปลักษณมหาบรมราชาภิเษกาภิลิต สรรพทศทิศวิชิตชัย สกลมไหสวริยมหาสวามินทร์ มเหศวรมหินทร มหารามาธิราชวโรดม บรมนาถชาติอาชาวศรัย พุทธาทิไตยรัตนสรณารักษ์ อดุลยศักดิ์อรรคนเรศราธิบดี เมตตากรุณาสีตลหฤทัย อโนปมัยบุญการสกลไพศาล มหารัษฎาธิบดินทร ปรมินทรธรรมิกหาราชาธิราช บรมนาถบพิตร พระจุฬาลงกรณ์เกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว]

has on his part named and appointed

- Phya Charone Raja Maitri, Chief Judge of the Foreign Court, First Minister Plenipotentiary,

- Phya Samud Puranurax, Governor of the District of Samudr Prakar [สมุทรปราการ], Second Minister Plenipotentiary,

- and Phra Maha Muntri Sriongrax Samuha, Chief of the Department of the Royal Body-Guard of the Right, Advisor;

- and Edward Fowle, Esquire, Luang Siamanukroh, Consul for Siam at Rangoon, Advisor;

and the aforesaid Plenipotentiaries having communicated to each other their respective full powers and found them to be in good and due form have agreed upon and concluded the following Articles: -

ARTICLE I.

His Majesty the King of Siam will cause the Prince of Chiangmai [เชียงใหม่] to establish and maintain Guard Stations under proper Officers on the Siamese bank of the Salween river, which forms the boundary of Chiangmai, belonging to Siam, and to maintain a sufficient Police force for the prevention of murder, robbery, dacoity and other heinous crimes.

ARTICLE II.

If any persons, having committed dacoity in any of the territories of Chiangmai [เชียงใหม่], Lakon [= Lampang - ลำปาง,], and Lampoonchi [= Lamphun - ลำพูน], cross the frontier into British territory, the British authorities and Police shall use their best endeavours to apprehend them. Such dacoits when apprehended shall, if Siamese subjects, be delivered over to the Siamese authorities at Chiangmai; if British subjects, they shall be dealt with by the British Officer in the Yoonzaleen District.

Abb.: Lage von Yoonzaleen

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]If any persons, having committed dacoity in British territory, cross the frontier into Chiangmai, Lakon, or Lampoonchi, the Siamese authorities and Police shall use their best endeavours to apprehend them. Such dacoits when apprehended shall, if British subjects, be delivered over to the British Officer in the Yoonzaleen District; if Siamese subjects, they shall be dealt with by the Siamese authorities at Chiangmai.

If any persons, whether provided with passports under Article VI of this Treaty or not, commit dacoity in British or Siamese territory and are apprehended in the territory in which the dacoity was committed, they may be tried and punished by the local Courts without question as to their nationality.

Property plundered by dacoits, when recovered by the authorities on either side of the frontier, shall be delivered to its proper owners.

ARTICLE III.

The Siamese authorities in Chiangmai, Lakon, and Lampoonchi will afford due assistance and protection to British subjects carrying on trade or business in any of those territories, and the British Government in India will afford similar assistance and protection to Siamese subjects from Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi carrying on trade or business in British territory.

ARTICLE IV.

British subjects entering Chiangmai, Lakon, and Lampoonchi from British Burmah must provide themselves with passports from The Chief Commissioner of British Burmah, or such Officer as he appoints in this behalf, stating their names, calling and description. Such passports must be renewed for each journey and must be shown to the Siamese Officers at the frontier stations, or in the interior of Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi on demand. Persons provided with passports and not carrying any articles prohibited under the Treaty concluded between Her Majesty the Queen of England and His Majesty the King of Siam on the eighteenth April one thousand eight hundred and fifty-five, and the supplementary agreement concluded between certain Royal Commissioners on the part of the Siamese Government and a Commissioner on the part of the British Government on the thirteenth May one thousand eight hundred and fifty-six shall be allowed to proceed on their journey without interference; persons unprovided with passports may be turned back to the frontier, but shall not be subjected to further interference.

ARTICLE V

For the purpose of settling future disputes of a civil nature between British and Siamese subjects in Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi belonging to Siam, the following provisions are agreed to: -

- His Majesty the King of Siam shall appoint proper persons to be Judges in Chiangmai with jurisdiction

- to investigate and decide claims of British subjects against Siamese subjects in Chiangmai, Lakon, Lampoonchi;

- to investigate and determine claims of Siamese subjects against British subjects entering Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi from British Burmah and having passports under Article IV provided such British Burmah subjects consent to the jurisdiction of the Court;

- Claims of Siamese subjects against British subjects entering Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi from British Burmah and holding passports under article IV., but not consenting to the jurisdiction of the Judges at Chiangmai appointed as aforesaid, shall be investigated and decided by the British Consul at Bangkok, or by the British Officer of the Yoonsaleen District;

- Claims of Siamese subjects against British subjects entering Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi from British Burmah, but not holding passports under Article IV., shall be investigated and decided by the ordinary local Courts.

ARTICLE VI

Siamese subjects in British Burmah having claims against each Other may apply to the Deputy Commissioner of the district in which they may happen to be, to arbitrate between them. Such Deputy Commissioner shall use his good offices to effect an amicable settlement of the dispute, and if both parties have agreed to this arbitration, his award shall be final and binding on them. Similarly British subjects in Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi having claims against each other may apply to any of the Judges at Chiangmai appointed under Article V., who shall use his good offices to effect an amicable settlement of the dispute, and if both parties have agreed to his arbitration, his award shall be final and binding on them.

ARTICLE VII.

Native Indian subjects of Her Britannic Majesty entering Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi from British Burmah, who are not provided with passports under Article IV., shall be liable to the local Courts and the local law for offences committed by them in Siamese territories. Native Indian subjects as aforesaid, who are provided with passports under Article IV., shall be dealt with for such offences by the British Officer in the Yoonsaleen district, according to British law.

ARTICLE VIII.

The Siamese authorities in Chiangmai, Lakon, and Lampoonchi and the British authorities in the Yoonsaleen District will at all times use their best endeavours to procure and furnish to the Courts in the Yoonsaleen District and the Consular Court at Bangkok and to the Court at Chiangmai respectively such evidence and witnesses as may be required for the determination of Civil and Criminal cases pending in these Courts.

ARTICLE IX.

In cases tried by the British Officer of the Yoonzaleen District, or by the Judges at Chiangmai appointed under Article V., in which Siamese or British subjects may respectively be interested the Siamese or British authorities may respectively depute an Officer to attend and listen to the investigation of the case and copies of the proceedings will be furnished gratis to the Siamese or British authorities respectively if required.

ARTICLE X.

British subjects provided with passports under Article IV., who desire to purchase, cut or girdle timber in the forests of

Chiangmai, Lakon and Lampoonchi, must enter into a written agreement for a definite period with the owner of the forest. Such agreement must be executed in duplicate, each party retaining a copy and each copy must be sealed by one of the Siamese Judges at Chiangmai appointed under Article V., and by the Prince of Chiangmai. A copy of every such agreement shall be furnished by the Judge at Chiangmai to the British Officer in the Yoonzaleen District. Any British subject cutting or girdling trees in any forest without the consent of the owner of the forest obtained as aforesaid, or after the expiry of the agreement relating thereto, shall, if provided with a passport, be liable to pay such compensation to the owner of the forest as the British consul at Bangkok or the Officer of the Yoonzaleen District may deem responsible; if unprovided with a passport, he maybe dealt with by the local courts according to the law of the country.ARTICLE XI.

The Judges at Chiangmai appointed under Article V., and the Prince of Chiangmai, shall endeavour to prevent owners of forests from executing agreements with more than one party for the same timber or forest, and to prevent any person from improperly marking or effacing the marks on timber which has been lawfully cut or marked by another person, and shall give such facilities as are in their power to purchasers and fellers of timber to identify their property. If the owners of forests prohibit the cutting, girdling, or removing of timber under agreements duly executed in accordance with Article X., the Judges at Chiangmai appointed under Article V., and the Prince of Chiangmai, shall enforce the agreements, and the owners of such forests acting as aforesaid shall be liable to pay such compensation to the persons with whom they have entered into such agreements as the judges at Chiangmai appointed as aforesaid may deem reasonable.

ARTICLE XII.

British subjects entering Siamese territory from British Burmah must, according to custom and the regulations of the country, pay the duties lawfully prescribed on goods liable to such duty.

Siamese subjects entering British territory must according to the regulations of the British Government, pay the duties lawfully prescribed on goods liable to such duty.

ARTICLE XIII.

The British Officer of the Yoonzaleen District may, subject to the conditions of this Treaty, exercise all or any of the powers that may be exercised by a British Consul under the Treaty concluded between Her Majesty the Queen of England and His Majesty the King of Siam on the eighteenth of April one thousand eight hundred and fifty-five, and the supplementary agreement concluded between certain Royal Commissioners on the part of the British Government on the thirteenth May one thousand eight hundred and fifty-six.

ARTICLE XIV.

Except as and to the extent herein specially provided, nothing in this Treaty shall be taken to affect the provisions of any Treaty or other agreement now in force between the British and Siamese Governments.

ARTICLE XV.

After the lapse of seven years from the date on which this Treaty shall come into force and on twelve months' notice given by either party this Treaty shall be subject to revision by commissioners appointed on both sides for this purpose, who shall be empowered to decide on and adopt such amendments as experience shall prove to be desirable.

ARTICLE XVI.

This Treaty has been executed in English and Siamese, both versions having the same meaning, but as the British Plenipotentiary has no knowledge of the Siamese language, it is hereby agreed that in the event of any question of construction arising on this Treaty, the English text shall be accepted as conveying in every respect its true meaning and intention.

ARTICLE XVII.

The ratification of this Treaty by His Excellency the Viceroy and Governor-General of India having been communicated to the Siamese Plenipotentiaries, this Treaty shall be ratified by His Majesty the King of Siam, and such ratification shall be transmitted to the Secretary to the government of India in the Foreign Department at Calcutta within four months or sooner if possible.

The Treaty having been so ratified shall come into force on the first January one thousand eight hundred and seventy-five Anno Domini, corresponding with the first day of the third Siamese moon in the year of Choh one thousand two hundred and thirty-six of the Siamese era, or on such earlier date as may be separately agreed upon.

In witness whereof, the respective Plenipotentiaries have signed in duplicate in English and Siamese the present Treaty and have affixed thereto their respective Seals.

Done at Calcutta this fourteenth day of January in the year one thousand eight hundred and seventy-four of the Christian era corresponding to the twelfth day of the second month of the twelfth waning moon of the year of Raka one thousand two hundred and thirty-five of the Siamese Era.

C. U. AITCHISON behalf of the Viceroy Governor-General of India

Signature of First

Signature of Second Plenipotentiary on Siamese Envoy Siamese Envoy"

[Zitiert in: Manich Jumsai [มานิจ ชุมสาย] <1908 - 2009>: History of Anglo-Thai relations. -- 6. ed. -- Bangkok : Chalermnit, 2000. -- 494 S. : Ill. ; 21 cm. -- S. 205 - 214]

1874-01-20

Vertrag von Pangkor: Perak (ڨيرق) wird britisches Protektorat. Mit deisem Vertrag beginnt das British Forward Movement auf der malaiischen Halbinsel, das bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg andauert. Ein Hauptvertreter des Forward Movement ist ab 1875 Sir Frank Athelstane Swettenham (1850 – 1946)

Abb.: Lage von Perak (ڨيرق)

[Bildquelle: Bartholomew, J. G. <1860 - 1920>: A literary & historical atlas of Asia. -- London, o. J.]

"Der Vertrag von Pangkor (engl. Pangkor Treaty) war ein Vertrag zwischen der britischen Regierung und dem Raja von Perak (ڨيرق). Der am 20. Januar 1874 von Sir Andrew Clarke und Raja Abdullah auf der Insel Pangkor vor Perak unterschriebene Vertrag hatte eine enorme Auswirkung auf die Geschichte des heutigen Malaysia. Er signalisierte offiziell den Beginn der britischen Einmischung in die Politik der Malaiischen Staaten. Geschichte

Die Region war zu dieser Zeit der weltgrößte Lieferant von Zinn und für die Briten, die damals schon in Penang, Malakka und Singapur auf der Malaiischen Halbinsel Stützpunkte hatten, äußerst wichtig. Machtkämpfe zwischen lokalen Fürsten und regelmäßige blutige Zwischenfälle um die beiden chinesischen Geheimorganisationen Ghee Hin und Hai San, die um die Kontrolle der Zinnminen kämpften, unterbrachen die Förderung des Metalles.

Der alte Herrscher von Perak Sultan Ali starb im Jahr 1871 und nach der fälligen komplizierten Thronfolge sollte Raja Abdullah der nächste Sultan werden. Stattdessen wurde Raja Ismail nach einigen Problemen gewählt. Später bat Raja Abdullah die Briten um Hilfe bei der Lösung der beiden Probleme. Die Briten erkannten die großartigen Möglichkeiten ihren Einfluss in Südostasien auszuweiten und das Monopol von Zinn zu stärken.

So kam es zu der Thronübernahme von Raja Abdullah und dem Vertrag von Pangkor 1874. Die Vereinbarung besagte :

- Raja Abdullah wird legitim als Sultan von Perak anerkannt und ersetzt Sultan Ismail, der einen Titel und eine Art monatliche finanzielle Abfindung in Höhe von 1000 mexikanischen Pesos bekommt.

- Dem Sultan wird ein britischer Resident zur Seite gestellt, dessen Rat in allen Fragen, außer Angelegenheiten von Religion oder Kultur, gesucht werden sollte.

- Die Kontrolle und Eintreibung der Steuern und die Verwaltung des Staates wird unter dem Namen des Sultans ausgeführt, aber angeordnet nach dem Ratschlag des Residenten.

- Der Minister von Larut wird weiter im Amt bleiben, aber nicht mehr als freier Führer anerkannt. Ein britischer Offizier wird an seiner Stelle mit weitreichenden Rechten in der Verwaltung ernannt.

- Nicht die britische Regierung, sondern der Sultan wird den Lohn des Residenten bezahlen.

Raja Ismal wusste nichts von dem Treffen zwischen Sir Andrew Clare und Raja Abdullah. Er hatte offensichtlich die Vereinbarung nicht anerkannt, konnte jedoch gegen das Bündnis von Raja Abdullah und den Briten nichts ausrichten. Sir J.W.W. Birch wurde zum ersten britischen Repräsentanten ernannt, nachdem der Vertrag in Kraft getreten war.

In den folgenden Jahren verstärkte sich der koloniale Einfluss und die drei malaiischen Staaten Negeri Sembilan (نڬري سمبيلن), Selangor (سلاڠور) und Pahang (ڤهڠ) wurden zu britischen Protektoraten. Diese Staaten bildeten ab 1896 die Föderierten Malaiischen Staaten (Federated Malay States, نڬري٢ ملايو برسكوتو)."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vertrag_von_Pangkor. -- ZUgriff am 2012-05-18]

1874-01-24

Es erscheint:

Caraman, Jean Fréderic <1840 - 1887>: Rapport sur le Combodge présenté le 24 Janvier 1874 au ministère de la marine et des colonies. -- Paris : Debons, 1874

"In January 1874, Caraman presented the Ministry of the Marine and Colonies with a printed document entitled Rapport sur le Cambodge, in which he argued forcefully against both the cession of the northwestern provinces to Bangkok and territorial claims of Cochinchina in the Gulf of Siam.14(1 According to the report, these territorial claims diminished French prestige in Cambodia and endangered the future of local trade and economic development. It was also entirely unworthy of the Grande Nation to coerce King Norodom into subsidizing the regional steamer service, which primarily served French interests and was of little value to the king. In arguing these points, Caraman claimed to act as "spokesperson of the Cambodian populations." In reality, he was probably acting as spokesperson for King Norodom to whom he wrote cryptically that he would return to Cambodia only "when certain affairs you have entrusted me with in private . . . are concluded."" [Quelle: Muller, Gregor [= Müller, Gregor] <1968 - >: Colonial Cambodia's 'bad Frenchmen' : the rise of French rule and the life of Thomas Caraman, 1840-87. -- London : Routledge, 2006. -- 294 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- (Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia ; 37). -- ISBN 978-0-415-54553-2. -- S. 99]

1874-02

Sir Andrew Clarke, Governor der britischen Straits Settlements, kommt mit einer Kriegsflotte nach Bandar Langat, dem Sultanssitz von Selangor (سلاڠور) unter dem Vorwand der Bestrafung von 8 Piraten aus Selangor, die in Malakka gefangen worden waren. Die Piraten werden in Selangor vor Gericht gestellt und sieben werden als schuldig befunden und hingerichtet. (Vermutlich handelt es sich um einen Justizirrtum.) Clarke nimmt den Vorfall zum Vorwand, Selangor zu zwingen, einen britischen Residenten zuzulassen.

Abb.: Lage von Bandar Langat

[Bildquelle: Swettenham: British Malaya, 1907, Beilage]

1874-02-20 - 1880-04-21

Benjamin Disraeli (1804 - 1881) ist Prime Minister Großbritanniens.

Abb.: Benjamin Disraeli / von Carlo Pellegrini (1839 - 1889)

[Bildquelle: Vanity Fair 1869-01-30 / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

1874-02-23

Der britische Major a. D. Walter Clopton Wingfield (1833 - 1912) lässt den Rasentennis (Lawn Tennis) patentieren.

Abb.: Titelblatt des Buchs von Walter Clopton Wingfield: Σφαιριστικη [Sphairistike] or Lawn tennis, 1874

[Bildquelel: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

1874-03

Der König an den Vizekönig von British India:

"We must make an effort to constrain the provinces." [Zitiert in: Battye, Noel Alfred <1935 - >: The military, government, and society in Siam, 1868-1910 : politics and military reform during the reign of King Chulalongkorn. -- 1974. -- 575 S. -- Diss., Cornell Univ. -- S. 146]

1874-03-15

Vertrag von Huế. Nachdem die Franzosen erkannt hatten, dass nur der Rote Fluss (紅河, Sông Hồng) den Landweg nach China eröffnet, hatten sie 1872 Teile Tongkins besetzt. Im Vertrag von Huế verpflichtet sich Frankreich, Tongkin wieder zu räumen, dafür muss Vietnam die Annexion der 1867 besetzten Gebiete Südvietnams anerkennen sowie weitere Häfen und den Roten Fluss für den französischen Handel öffnen. Die vietnamesische Regierung verpflichtet sich, ihre Außenpolitik mit der Frankreichs abzustimmen, und gibt Frankreich das Recht, bei der Aufrechterhaltung der inneren Ordnung und der Landesverteidigung "Hilfe" zu leisten. Die Handelsfreiheit auf dem Roten Fluss kann nicht richtig genutzt werden, da chinesische Banden (vor allem "Les Pavillons Noirs" - 黑旗军 - Quân cờ đen) faktisch Tonking kontrollieren. Französische Handelsgesellschaften fordern daraufhin von der französischen Regierung den Schutz ihrer vietnamesischen Niederlassungen.

Abb.: Der Rote Fluss (紅河, Sông Hồng)

[Bildquelle: Kmusser / Wikipedia. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1874-04

Heinrich Schüren (1849 - ?), deutscher Fotograf in Singapur, kommt nach Siam und fotografiert.

1874-05-06

Bildung des ersten "Council of State" (es hat zunächst die englische Bezeichnung "Khaonsin op Satet", später: สภาที่ปฤกษาราชการแผ่นดิน). Präambel zur königlichen Erlass:

"His Majesty wishes to remove oppression and lower his status so as to allow officials to sit on chairs instead of prostrating in his presence. His reason for founding this Council is that, as he cannot himself carry out public duties successfully, the assistance of others will bring prosperity to the country. Appointment of selected intellectuals is simply to advise the King, and in cases of controversy, he can decide impartially regardless of the seniority of persons concerned. Whatever is agreed on can be turned into a bill to be presented to the King at the following session. When the bill is finalized, it can be read to advisers. If all is found to be in order, and it concerns only a minor matter, it can be proclaimed as an act without further ado. If, on the other hand, it constitutes a major principle, it will be referred to the various Secretaries of State, and, if their consent is obtained, then the bill receives royal assent and becomes an Act." [Übersetzt in: Prachoom Chomchai [ประชุม โฉมฉาย] <1931 - >: Chulalongkorn the great : a volume of readings edited and translated from Thai texts. -- Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, 1965. -- 167 S. ; 19 cm. -- (East Asian cultural studies series ; no. 8.). -- S. 31]

Die Mitglieder des State Council erhalten einen Monatslohn von monatlich 300 Baht. Nach 5 Dienstjahren haben sie Anspruch auf eine Pension von 100 Baht monatlich.

Die Mitglieder des Council of State müssen einen Eid leisten:

"Before accepting the post of cabinet Minister, a person had to take an oath before the King (sacred water had also to be taken):

- to give advice on public affairs to the best of his knowledge and ability;

- not to be absent from a meeting without reasonable cause;

- to have at heart only public interest and welfare;

- neither to favour his own relatives and family members nor to fear any other person’s influence;

- to keep State secrets and to conceal what should not be disclosed;

- not to distort things for the sake of pecuniary gain;

- to co-operate with other Ministers in carrying out what had been agreed on and to oppose and fight against whoever stood in its way; and

- to behave himself in an exemplary manner and to be virtuous, loyal and grateful."

[Übersetzt in: Prachoom Chomchai [ประชุม โฉมฉาย] <1931 - >: Chulalongkorn the great : a volume of readings edited and translated from Thai texts. -- Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, 1965. -- 167 S. ; 19 cm. -- (East Asian cultural studies series ; no. 8.). -- S. 32f.]

Dem erste Council of State gehören an:

- Praya Raj Supawadi (พระยาราชสุภาวดี) / Peng Penkul (เพ็ง เพ็ญกุล)

- Phraya Si Phiphat (พระยาศรีพิพัฒน์

) / Phae Bunnag (แพ บุนนาค)- Praya Raj Waranukul (พระยาราชวรานุกูล) / Rod Kalyanamit (รอด กัลยาณมิตร)

- Praya Kasap Kitkosol (พระยากสาปณ์กิจโกศล) / Mode Amatayakul (โหมด อมาตยกุล)

- Phraya Phatsakorawong (พระยาภาสกรวงศ์

) / Phon Bunnag (พร บุนนาค) (1849–1920)- Praya Maha Amart (พระยามหาอำมาตย์) / Chun Kalyanamit (ชื่น กัลยาณมิตร)

- Praya Apai Ronarit (พระยาอภัยรณฤทธิ์ ) / แย้ม บุญยรัตพันธุ์

- Praya Ruchai (พระยาราไชย) / Chamrern Buranasiri (จำเริญ บุรณศิริ)

- Praya Charern Rajmaitri (พระยาเจริญราชไมตรี) / ตาด อมาตยกุล

- Praya Pipit Pokai (พระยาพิพิธโภไคย) / ทองคำ สุวรรณทัต

- Praya Rajyota (พระยาราชโยธา ) / ทองอยู่ ภูมิรัตน์

- Praya Klahom Rajsena (พระยากระลาโหมราชเสนา )

Gleichzeitig wird ein Council for State Administration gebildet, das 10 bis 20 Miglieder hat, darunter 6 Mitglieder der Königsfamilie. Diese können von Kabinettssitzungen ausgeschlossen, wenn dies 6 Mitglieder des Council of State wünschen.

1874-05-04

Jean Moura (1827 - 1885), Repräsentant Frankreichs in Kambodscha, berichtet an den Direktor im Innenministerium, Piquet, dass König Norodom I (ព្រះបាទនរោត្តម) von Kambodscha (Februar 1834 – 24. April 1904) darüber gekränkte gewesen war, dass er Siam Tribut zahlen musste. Bei der Unterzeichnung des Protektionsvertrages mit Frankreich 1863-08-11 sei es einer der Gründe für Norodom gewesen, dass Frankreich keine Tributzahlungen verlangte.

1874-05-08

Schaffung eines Privy Council (ที่ปฤกษาในพระองค์). Es hat 49 Mitglieder:

- 13 Angehörige der Königsfamilie

- 2 Chaophraya

- 34 Angehörige des niederen Adels und der Beamtenschaft

Eine der wichtigsten Entscheidungen des Privy Council in der Folgezeit ist die, ob der Telegraphiedienst staatlich oder privat ist. Aus dem Protokoll der Sitzung:

"When the question of telegraphic facilities was discussed, 45 voted in favour of and 3 against the motion to let the Government provide them. If this were to be left to a private company, it would give rise to several difficulties and would involve the Government in a payment to the company of 2400 changs [ชั่ง] [= 192.000 Baht]. If the Government itself provided the facilities, the amount of investment involved would be just the same. Moreover, there would be little controversy and the Government would not be too concerned over the question of whether the facilities were provided at a loss or at a profit, the objective being not so much to gain direct profit from them. The general consideration was that more exports would bring prosperity to the country and this would be advantageous to the Government on account of increased tax revenue. In the initial stages, it was expected to charge rates high enough to cover costs. Later on, however, if they proved to be useful and popular and brought prosperity to the country, rates would be reduced in the public interest. It was thus agreed in the Privy Council to let the Government undertake their provision, and this resolution would be sent to the Council of State and Secretaries of State, as required by custom. " [Übersetzt in: Prachoom Chomchai [ประชุม โฉมฉาย] <1931 - >: Chulalongkorn the great : a volume of readings edited and translated from Thai texts. -- Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, 1965. -- 167 S. ; 19 cm. -- (East Asian cultural studies series ; no. 8.). -- S. 39f.]

"Although the King became the legitimate ruler in 1873, when the Regency was dissolved on his coming of age, he still had no power, for the Regent's faction continued to dominate the government. Since he was not strong enough to dismiss the ministers, the King tried to bypass them and to govern the country directly through two councils, the State Council and the Privy Council [ที่ปฤกษาในพระองค์], which were set up respectively in June and August of 1874. The twelve State Councillors and forty-nine Privy Councillors who were the King's nominees, were enjoined to make known, 'what is or may be burdensome' to the people, and 'to effect their modification.' In the judicial sphere, the power of the ministerial courts was undermined by the establishment of the Supreme Court, the San Rapsang [ศาลรับสั่ง], in the same year. It was easier to make appeals to this court of ten judges than to the King, who up till then had been the highest appellate authority in the land."

[Quelle: Tej Bunnag [เตช บุนนาค] <1943 - >: The provincial administration of Siam from 1892 to 1915 : a study off the creation, the growth, the achievements, and the implications for modern Siam, of the ministry of the interior under prince Damrong Rachanuphap. -- Diss. Oxford : St. Anthonys College, Michaelmas Term 1968. -- 429 S., Schreibmaschinenschrift. -- S. 88. -- Faire use]

1874-05-13

Die Missionarin Harriet House eröffnet die Wang Lang Schule für Mädchen (โรงเรียนกุลสตรีวังหลัง), der Vorläuferin der Wattana Wittaya Academy (วัฒนาวิทยาลัย)

Abb.: Harriet House

"1870/2413: The land at Wanglang [วังหลัง] was bought. Reverend S. C. George was in charge of the construction. But the work was not completed due to budget had run out. He had to return to the US for health reason. Mrs. Harriet House solicited another 3,000 US. Dollars to finish off the construction.

1874/2417: On the 13th of May, Mrs. House began the operation of Wanglang School. This is considered the birth date of Wattana Wittaya Academy [วัฒนาวิทยาลัย].

1875/2418: There were 15 pupils at Wanglang School. Miss Arabella Anderson was the first teacher in Wanglang School. Since Mrs. House was well-known among courtiers, Phraya Surasakmontri [พระยาสุรศักดิ์มนตรี] (Saeng [แสง], who was the ancestor of Saeng-Xuto [แสง-ชูโต] family) sent 4 of his daughters to Wangalang School. Their ID numbers were 14, 15, 16 and 17. Their names were Yuen, Lek, Zin and Loy [เยื้อน เล็ก สิน ลอย].

1875/2418: Miss Anderson married Rev. H.B. Noyes, D.D. who was a doctor from China.

1875/2418: Miss S. D. Grimstead came to teach at Wanglang. There were 20 pupils.

1877/2420: Mrs. House’s health deteriorated. Doctor and Mrs. House had to return the the USA after 30 years work in Siam. They took Mr. Korn Amatyakul [นายกร อมาตยกุล] and Mr. Boontuan Boon Itt [อาจารย์บุญต๋วน บุญอิต, 1865 - 1903] to the USA with them, for education purpose.

Abb.: Boontuan Boon Itt (อาจารย์บุญต๋วน บุญอิต)

[Bildquelle: th.Wikipedia. -- Public domain]1877/2420: Miss Jennie Koresen came to teach at Wanglang. Miss Jennie married Rev. James McCauley D.D.

1878/2421: Miss Belle Caldwel became the Principal of Wanglang School. There were 29 pupils. The school had expense of US$490 and income of US$40.00. Miss Caldwel married Rev. J. Culberton.

1878/2421: The second church was set up at Wanglang School.

1882/2425: In the Bangkok Centennial Celebration in April, Wanglang School participated in Thai children education exhibition and the school pupils’ handicrafts were on show in Somdej Phra Panvassa’s [สมเด็จพระพันวัสสา, 1862 - 1955] stall (She was the royal Grandmother of King Bhumiphol).

1885/2428: Miss Mary E. Hartwell and Miss Auara A. Olmstead managed the school during the time that there was no teacher from the Mission.

1885/2428: Mrs. Tuan [แม่ต๋วน], Mr. Boontuan Boon-Itt’s [อาจารย์บุญต๋วน บุญอิต] mother was both housekeeper and teacher, looking after Wanglang School.

1885/2428: Mrs. Tuan [แม่ต๋วน] resigned. Pupils loved and respected her very much. So, the older pupils also resigned.

1885/2428: Miss Cole asked teacher Yuan Tiang Yok [ครูญ่วน เตียงหยก] and his wife to come and help at Wanglang School. Miss Marry S. Handerson become Miss Cole’s assistant.

1885/2428: There was a full improvement of classroom and education equipment because school fee of 5 baht per month were collected. On the first term, there were only 16 pupils left. Miss Soi [แม่สร้อย] was an assistant teacher to Miss Olmstead

1887/2430: Miss Van Emmon became Wanglang School Principal. Later, she married Reverend Christian Berger

1888/2431: Miss Soi [แม่สร้อย] married Mr. Boonyee Boon-Itt [อาจารย์บุญยี่ บุญอิต] and moved to Chiangmai [เชียงใหม่].

1888/2431: Miss Tim [แม่ทิม] graduated and became a teacher. Miss Suwan [แม่สุวรรณ], Miss Chaem [แม่แช่ม], Miss Ploy [แม่พลอย] and Miss Tao [แม่เต่า] also became teachers at Wanglang School.

1888/2431: Prince Naradhip [กรมหมื่นนราธิประพันธ์พงษ์, 1861 - 1931] sponsored the school.

Abb.: Prinz Naradhip (กรมหมื่นนราธิประพันธ์พงษ์)

[Bilddquelle: th.Wikipedia. -- Public domain]1889/2432: Prince Naradhip [กรมหมื่นนราธิประพันธ์พงษ์] was the first royal family member who was so pleased with the school that he sent his eldest daughter – Princess Banbimol [ม่อมเจ้าหญิงพรรณพิมล] to study in the same class as ordinary people. Her pupil ID number was 131.

1890/2433: Miss S. E. Parker and Miss L.J. Cooper came to help teachers in Wanglang School. Miss Cooper went to open a school in Nakorn Chaisri [นครชัยศรี].

1891/2434: Prince Damrong [สมเด็จฯกรมพระยาดำรงราชานุภาพ, 1862 - 1943], the Minister of Education sent Edwin McFarland, Phra Artvidhyakom’s [พระอาจวิทยาคม = George Bradley McFarland, 1866 - 1942] elder brother, to study about USA’s education system.

1898/2441: King Chulalongkorn made a trip to Europe. He appointed Queen Saovabha-pongsri [สมเด็จพระนางเจ้าเสาวภาผ่องศรี, 1864 - 1919] as the Regent. Women were roused by this event a great deal. Girl schools were opened around Bangkok. Wanglang was teachers training ground for both private and almost all newly opened public schools. So, a person graduated from Wanglang was appointed as school principal immediately. Rajini [โรงเรียนราชินี] and Wanglang Schools cooperated to provide teachers for girl schools around the country.

1903/2446: Miss Edna Bruner, an expert in art, came to join Wanglang School for two years. Later, she married Dr. L.C. Bulkley and moved to Trang [ตรัง] Province.

1904/2447: Miss Tard [นางสาวตาด], Miss Linchee She [นางสาวลิ้นจี่ ชี], Miss Tongsuk [นางสาวทองสุก] and Miss Chaem [นางสาวแช่ม] passed the boys’ examination.

1905/2448: Miss Magaret C. McCord came to join Wanglang.

1905/2448: Miss Aroon [นางสาวอรุณ], the daughter of Mr. Tiensang Prateepasen [นายเทียนสั่ง ประทีปเสน] (later known as Khunying Aroon Medhadhibadi [คุณหญิงอรุณ เมธาธิบดี]) went for a further education in kindergarten teaching, according to Froebel Theory, at Normal Training College of Connecticut. Three years later, she came back to start kindergarten teaching in Wanglang School. So, Wanglang was the first school that provided kindergarten education. Khunying Aroon was the first lady to teach kindergarten in Thailand.

1908/2451: Miss Bertha Blount joined Wanglang School. At that time, King Chulalongkorn had abolished all kind of gambling. There was one large casino nearby that villagers used as pig sty. Miss Cole rented the place, cleaned it and used it as school as well as a place where villagers could obtain free medicine. Moreover, “Utissathan” [อุทิศสถาน] was also a kitchen where Miss McCord used to cook for pupils and Wanglang society. "

[Quelle: http://www.wanglangwattana.org/museum/history_3.html. -- Zugriff am 2015-03-24. -- Fair use]

1874-06-01

Auflösung der britischen Honourable East India Company.

1874-06-12

Rama V. über Sklaverei:

"On Wednesday, the ninth day of Waxing Moon, in the eighth month (corresponding to Wednesday, 12 July, B. E. 2417) the Advisers on State Affairs met in the Sommot Devaraj Upabat House in the evening, and the King brought up the question of reducing the age of emancipation for slaves and of allowing parents to sell them according to, and not at prices in excess of, the new scale. On this the King produced the following document outlining his view:

“I wish to see whatever is beneficial to the people accomplished gradually according to circumstances and unjust, though well-established, customs abolished. But, as it is impossible to change everything overnight, steady pruning is necessary to lighten the burden. If this practice is adopted, things will proceed smoothly and satisfactorily as time goes by.As far as slavery is concerned, children born to slaves in their creditors’ houses are considered by present legislation to be slaves. For this purpose, male slaves born in such circumstances from the age of 26 to 40 are worth each, according to present legislation, 14 tamlungs [ตำลึง = 4 Baht] [= 56 Baht], while female ones are worth each 12 tamlungs [= 48 Baht]. In the case of male slaves of more than 40 and female ones of more than 30, value declines gradually with advancing age until at 100 male slaves are worth 1 tamlung [= 4 Baht] while female ones 3 baht.

I feel that children born to slaves in their creditor’s houses, who are slaves as from the time of delivery and are worth something even beyond 100, have not been treated kindly. Children thus born have nothing to do with their parents’ wrong doing. The parents have not only sold themselves into slavery but also dragged their innocent children into lifetime slavery and suffering on their behalf. But to emancipate them straight away now would put them into the danger of being neglected and being left to die by themselves, since unkind creditors, seeing no use in letting mothers look after their children, will put these mothers to work. It is therefore felt that, if these children are of no use to their parents’ creditors, they will meet with no kindness. If the burden borne at present is so reduced as to allow them to become free, it seems advisable. Slaves’ children aged from 8 upwards can be depended upon to work, and thus their full worth should be calculated as from this age. With advancing years their worth should be reduced until at 21 they are emancipated just in time for ordination as priests and for embarking on their career.

Similarly, female slaves are emancipated just in time to get married and have children. If this practice is followed, their worth can be determined in this way.

Slaves’ children from their birth to 8 years are worth 8 tamlungs [= 32 Baht], and from then on value declines.

- Those from 9 to 11 are worth 7 tamlungs [= 28 Baht];

- 12 to 14, 5 tamlungs [= 20 Baht];

- 15 to 17, 3 tamlungs 2 baht [= 14 Baht];

- 18 to 20, 1 tamlung [= 4 Baht].

- Girls from 9 to 11 are worth 6 tamlungs [= 24 Baht];

- 12 to 14, 4 tamlungs 3 baht [= 19 Baht];

- 15 to 17, 3 tamlungs [= 12 Baht];

- 18 to 20, 3 baht.

Thus at 21 they are emancipated, and, in view of the fact that they have served their masters up to 20, enough advantage has been derived by their masters. Slaves children are obtained for nothing, and beyond 20 they should be set free from further oppression. If they are good, they still have time to vindicate themselves. This causes no distress to their masters, since these children’s services have been obtained for nothing. In any case, the practice of calculating their worth is no longer followed very strictly in high-ranking families, though the custom still remains.

Slaves’ children who are thus emancipated at 21 will probably be tattooed as slaves’ children having to pay an annual sum of 6 salungs [สลึง = ¼ Baht] [= 1½ Baht] to the State. They are in all probability unwilling to be tattooed as soms [ไพร่สม = zur Fron bei Adligen verpflichtet], since this involves payment of the higher annual sum of 6 baht. This unhappy situation has resulted from irregularity in collecting State dues. Moreover, once the slaves are emancipated, their creditors will hasten to send them to Krom Pra Suratsawadi to be tattooed for fear of having to continue payment to the State in respect of them. Krom Pra Suratsawadi [กรมพระสุรัสวดี] cannot leave them at large and have to chain them until there are masters to take them. If that is the natural course of things, what is meant to lighten their burden can indeed aggravate it. Being chained after emancipation is like being slaves all over again.

This emancipation process should thus be carried further. Slaves’ children who are emancipated and have had their wrists tattooed should still be called slaves’ children, paying to the State an annual sum of 6 salungs [= 1½ Baht], whether they are with the old masters or with new ones. If slaves’ children thus emancipated misbehave and return to slavery, there should be a written evidence of the debt concerned. Once they have paid it up, they should be tattooed as soms according to the old law. Slaves or slaves’ children with such written documents, after having gained freedom, should be similarly tattooed as soms. Slaves’ children with no tattoo on the right wrists, having become free either because they have reached the emancipation age or have paid up their debt, should be tattooed as soms, unless they have become officials, since it is a penalty to have evaded earlier tattooing. This will reduce the number of slaves’ children who return to slavery and will give them an opportunity to start their career.

It also often happens that parents are indolent and become gamblers. After gambling losses they sell their children into slavery in order to pay their creditors. As the children grow up, their parents put more value on them. This being the case, it is rare that their children are able to redeem themselves owing to the high prices these children have to pay. The original law on slavery provided that parents and husbands could put down the names of their children and wives respectively in slavery documents, no matter whether this fact is made known by creditors or not, since parents, husbands and creditors are free. Later on Prabat Somdech Pra Chomklao Chaoyuhua [Rama IV. / ระบาทสมเด็จ พระจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว, 1804 - 1868] repealed this law and put in its place the following provisions. Parents can sell their children not: reaching the age of 15, provided that these children live with them, no matter whether or not they have affixed their fingerprints in place of signatures or consented. But, in cases where children do not live with their parents or where parents are divorced and children live with one parent, the other cannot clandestinely give their names for sale into slavery. On the other hand, children from the age of 15 can be sold by parents provided they affix their fingerprints in place of signatures to signify consent. Adopted orphans not having reached the age of 7 can be sold as though they were one’s own children, since they are rightful heirs; but if their age is beyond 15, their consent is required for such sale. All this shows that Prabat Somdech Pra Chomklao Chaoyuhua has already given liberal concessions.

My own feeling on this is that parents should still, according to King Chomklao’s law, be allowed to sell their children not reaching the age of 15, no matter whether these children are aware of this or not, so that they can be made to suffer on behalf of their parents. To forbid such sale will cause distress to parents who feel that children whom they have brought up with pains should be allowed to help them out on a rainy day. This is the difficulty preventing the custom of selling children into slavery from being rapidly uprooted. Besides, without such right of sale, parents will no longer be creditable borrowers. So this has to be allowed, though with a proviso that, in cases of children under 15, their worth upon sale must be determined according to my new formula; as far as children beyond the age of 15 are concerned, they should be told of this, and, sale is allowed, according to King Chomklao’s law, only with the children’s consent, even at prices in excess of those determined by the formula. All this I wanted to see in the very first year in which I came to the throne, that is the Year of the Dragon. In future, slaves’ children born in that year should be subjected to my formula as from their 9th year, while those born before that year would remain subject to the old law on the ground of difficulty in applying the new formula to them. However, it will be difficult to think always on the basis of the Year of the Dragon, since many children were sold at very high prices in the Year of the Dog. It seems reasonable to lay down the rule that the new Act should not apply to sales effected before it comes into force.

However, I do not think that my proposal can be carried to its logical conclusions, since pressure exists in the direction of making people want to become slaves despite our desire to see the contrary. Slaves do not have to pay high State dues and do not have to engage in any regular occupation, since they are maintained by their masters. They work when work comes to them; otherwise they are unoccupied. When there is nothing to do and they happen to come by a bit of money, they gamble, since there is no risk of losing their means of subsistence. To eradicate slavery it is necessary to go to its root causes; but whatever can be done in the circumstances should proceed step by step. Whenever time is ripe, the basic cause, namely, inequality in paying State dues, should be eliminated through levelling downwards and upwards so that, finally, no matter whether persons are free or not, the same payment is due from them. Moreover, sufficient public revenue must be found to make up for abolition of this important institution causing people a loss of time devoted to earning their living. For this to succeed buoyant times are required. Pending this state of affairs and pending an adequate increase in public revenue, there can be no complete abolition of slavery. But what is possible must be done to open floodgates to the reform which will ensue with a change of circumstances. If any one of you see any inconsistency between my proposal on the one hand and the old law and customs on other or any distress on the part of creditors and slaves now and in the future likely to be caused by my proposal, please say so, this business of slavery being connected with so many laws and so many other activities that it is unlikely for one man to have a whole view of it. If any one of you can think of snags likely to crop up now or in the future, kindly put the relevant considerations into writing for further discussion among us. If there are obstacles we can go as far as we can; if there are none, we shall see the whole thing through. If my proposal really succeeds, I can think of one other thing which can effectively liberate slaves’ children from slavery. Slaves’ children are compelled to serve their masters from an early age and know nothing other than what pleases their masters. Instead of getting vocational training, they spend their free time in gambling from early childhood so that this habit becomes ingrained, thereby preventing them from seeing any value in having a career. If they really have to quit slavery, they do not possess sufficient knowledge to improve their status and are compelled to return to slavery. It is because of this that there should be an institution for education similar to the old alms-house where, by royal command, education was given to children. There have been a good many men educated in this manner, and many available clerks at the moment came from such institution. However, education was not thorough, since teachers were not interested in teaching and in enforcing discipline to ensure regular attendance. In addition to this, monastery schools have been founded for noblemen’s children, and these have produced better results than alms-houses. Again, there is no regular attendance and it takes some time to educate these children. At the present time, there are not enough clerks to go round. Literate people are in great demand among the noblemen and will not readily remain slaves. This is why I feel that education can really free slaves. If slaves’ children can be liberated in the manner I propose, then the establishment of schools can help them. For instance, slaves’ children of the age of 11 or 12 can be bought at 7 tamlungs [= 28 Baht] or 5 tamlungs 2 [= 22 Baht] baht and compelled to go to school. With regular teaching and boarding facilities, they can be kept from exposure to gambling in which children of 12 to 14 tend to indulge. Once they can read and write, various subjects including those derived from translated European texts can be taught. At 17 or 18 they should be able to apply their knowledge to various branches of the civil service as petty officials or clerks, or secure employment outside the civil service. There is little likelihood, then, of their going to the dogs, unless they are inherently bad. But school education is an increasingly expensive undertaking, and should begin in a small way with possibilities of gradual expansion. This will not only reduce the number of slaves but will also bring prosperity to the country, paving the way for a more drastic reform in the future. As the country prospers, the whole thing will have to be reviewed and put into effect at a time which you consider best. ”

[Übersetzt in: Prachoom Chomchai [ประชุม โฉมฉาย] <1931 - >: Chulalongkorn the great : a volume of readings edited and translated from Thai texts. -- Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, 1965. -- 167 S. ; 19 cm. -- (East Asian cultural studies series ; no. 8.). -- S. 51 - 58]

1874-06-22

Der König verkündet öffentlich die Bildung eines Council of State (สภาที่ปฤกษาราชการแผ่นดิน):

"Anything contemplated by His Majesty which is unjust and causes popular distress because pressure is put on the people to contribute more to the public coffers can be opposed by the Council. The King alone, checked by the Council, cannot go very far in exercising his power in the wrong direction, no matter how much power rests with him." In closing he said. All of you will wonder why I should appoint people to stop me from exercising my power. Please understand that the Council is meant to do away with such steps and practices as have brought trouble to the people. When the masses which constitute the blood of the country are happy and are engaged in legitimate occupations, the country can indeed prosper."

[Übersetzt in: Prachoom Chomchai [ประชุม โฉมฉาย] <1931 - >: Chulalongkorn the great : a volume of readings edited and translated from Thai texts. -- Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, 1965. -- 167 S. ; 19 cm. -- (East Asian cultural studies series ; no. 8.). -- S. 33f.]

1874-07

"In July 1874, the Council of State recommended that Phraya Ahan Borirak [พระยา บริรักษ์], the Minister of Lands and a nephew of Sisuryawong [Ex-Regent สมเด็จเจ้าพระยา บรมมหาศรีสุริยวงศ์ aka. Chuang Bunnag - ช่วง บุนนาค, 1808 - 1883], be removed from the council for unwillingness to disclose information about land taxes. By November, a committee of the council chaired by Phraya Kasap (Mot Amatayakul [อมาตยกุล]) had tried the minister, found him guilty of embezzling and sentenced him to imprisonment. Meanwhile, the council had also recommended a measure to abolish slavery which passed into law. It was said that the ministers and the people feared the new council." [Quelle: Battye, Noel Alfred <1935 - >: The military, government, and society in Siam, 1868-1910 : politics and military reform during the reign of King Chulalongkorn. -- 1974. -- 575 S. -- Diss., Cornell Univ. -- S. 155]

1874-07-07 - 1875-06

Es erscheint die Wochenzeitung

ดรุโณวาท [Darunovad - Belehrung der Jugend] / hrsg. von พระองค์เจ้าเกษมสันต์โสภาคย์ [H.R.H. Prince Kasemsanta] <1856 - 1924>

Es ist die erste Zeitung Siams im Besitz eines Siamesen.

Abb.: Titelblatt

1874-09-15 - 1874-10-09

Weltpostkongress in Bern (Schweiz): 21 Länder unterzeichen den Allgemeinen Postvereinsvertrag (Berner Konvention). Sie tritt am 1875-01-01 in Kraft.

Abb.: Gründung des Weltpostvereins 1874

[Bildquelle: Sammelbild Homann Margarinewerk, 1934]

1874-12-05

Sisuryawong [สมเด็จเจ้าพระยาบรมมหาศรีสุริยวงศ์, aka. Chuang Bunnag - ช่วง บุนนาค, 1803 - 1883] bittet den britischen Konsul Thomas George Knox (1824 - 1887), Prinz Bovorn Vichaichan (กรมพระราชวังบวรวิไชยชาญ, 1838 - 1885) mit aller Macht zu unterstützen.

1874-12-28 - 1875-02-25

Front-Palast-Krise (วิกฤตการณ์วังหน้า).

"The Front Palace crisis or the Front Palace incident (Thai: วิกฤตการณ์วังหน้า) (Wang Na crisis or incident) was a political crisis that took place in the Kingdom of Siam from 28 December 1874 to 25 February 1875. The crisis was a power struggle between the reformist King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) and the conservative Prince Bovorn Vichaichan (กรมพระราชวังบวรวิไชยชาญ, 1838 - 1885) the Second King. Chulalongkorn came to the throne in 1868, Vichaichan was appointed Front Palace (กรมพระราชวังบวรสถานมงคล / วังหน้า) or Second King in the same year. The progressive reforms of King Chulalongkorn aroused the ire of Prince Vichaichan and the nobility, who saw their power and influence being slowly eroded. A fire in the Grand Palace (พระบรมมหาราชวัง) led to an open confrontation between the two factions. Prompting Vichaichan to flee to the British Consulate, as a result the crisis reached stalemate. The crisis was finally resolved with the presence of Sir Andrew Clarke (1824 - 1902) the Governor of the Straits Settlements, who supported the king over his cousin. Afterwards the Front Palace was stripped of its power and after Vichaichan's death in 1885 the title was abolished.

PreludeVichaichan

Since the elevation of Second King Pinklao((พระบาทสมเด็จพระปิ่นเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว, 1808 - 1866) by his brother King Mongkut (Rama IV) twenty years earlier, the office of Front Palace had gained considerable amount of power and prestige. Since Siam did not have a law of succession, the position of Second King was seen as the strongest claimant and was therefore also the position of the heir presumptive to the throne.[1] The Second King also had his own army of over 2,000 men, western trained and western armed.[2] He also controlled a naval forces of several steam powered gunboats. The Prince also had a large share of state revenues over one-third of which is given directly to him for the maintenance of his officials, retinue, court, concubines and advisors.[1][3][4]

In August 1868 King Mongkut contracted malaria whilst on an expedition to see a solar eclipse in Prachuap Khiri Khan province (ประจวบคีรีขันธ์), six weeks later he died on 1 October. The young Chulalongkorn (who was only 15 years old at the time) was unanimously declared king by a council of high-ranking nobility, princes of the Chakri Dynasty and monks.[5] The council was presided by Si Suriyawongse (สมเด็จเจ้าพระยาบรมมหาศรีสุริยวงศ์, 1808 - 1883) who was also appointed Regent for the young King.[6][7]

During the meeting when one of the Princes nominated Prince Yodying Prayurayot Krom Muen Bovorn Vichaichan as the next Front Palace, many in the council objected. The most notable objection of this nomination came from Prince Vorachak Tharanubhab.[6] The Prince argued that the appointment of such an important position was the sole prerogative of the king and not of the council, and that the council should wait until the king was old enough to appoint his own. Furthermore the position was not hereditary and the appointment of the son of the former could set a dangerous precedent.[1] The nomination of Vichaichan however was supported by the powerful Regent and Prime Minister Chao Phraya Si Suriyawongse (Chuang Bunnag) who wanted to secure a line of succession by appointing an able and experienced Front Palace (as the second-in-line to the throne).[7] Si Suriyawongse was determined, he retorted by accusing the Prince of wanting to be appointed himself, saying: "You don't agree. Is it because you want to be (Uparaja) yourself?" ("ที่ไม่ยอมนั้น อยากจะเป็นเองหรือ"). The Prince replied wearily "If you want me to agree then I agree" ("ถ้าจะให้ยอมก็ต้องยอม").[7][8] As a result Prince Vichaichan, at the age of 30, was appointed Front Palace (Krom Phra Rajawang Bovorn Sathan Mongkol) and Second King without the full consent of the incoming monarch.[6] The relationship between Chulalongkorn and the Vichaichan would remain difficult for the rest of the latter's life, based on this fact.[9] On 11 November 1868 Vichaichan's cousin Chulalongkorn was crowned Supreme King of Siam at the Grand Palace.

ChulalongkornOn 20 September 1873 King Chulalongkorn formally reached his majority at the age of 20 resulting in the dissolution of the regency of Si Suriyawongse. During the five years of the regency Vichaicharn decided to limit his role and power out of reverence for the Regent, who arranged for his appointment.[10] However with the dissolution of the regency Vichaichan was ready to reassert the powers of his office. Unfortunately Chulalongkorn and his brothers or Young Siam was at the same time trying to consolidate his own authority and return to the Grand Palace the power it had lost since the death of his father.[11] Spurred on by their Western education, Young Siam was intent on creating a centralized and strong nation under an absolute monarch. In order to achieve this goal, he needed to implement radical reforms in all parts of the Royal Government.[12]

In 1873 the king established the 'Auditing Office' (หอรัษฎากรพิพัฒน์, now the Ministry of Finance). The office was created to modernize and simplify the collection of state revenues and taxes to the treasury. At the same time however it deprived the nobility (as landowners) control over tax farms, which for generations had constituted a large part of their income.[12] Then in 1874 the king by Royal Decree created the 'Privy Council of Siam' (สภากรรมการองคมนตรี). Copied from the European tradition, the council was an effort by the king to shore up his own legitimacy and to create an elite he could rely on. In their inauguration speeches the forty-eight councilors pledged allegiance to the Monarch and his heirs.[1]

These two reforms infuriated the conservative faction at court or Old Siam composed mainly of old aristocratic families. The financial reforms eroded some of their old privileges. Politically the creation of the Privy Council meant that only royal favourites had access to political offices, depriving them of their influences.[13] This group included Vichaichan, whose role in the finance and the government of the kingdom was slowly being eroded. Conflict between the two sides seemed inevitable. Vichaichan had the support of the British Consul-General to Siam: Thomas George Knox, he was originally recruited by Pinklao to modernize the Front Palace's armed forces. After Mongkut's death, Knox greatly preferred the mature and experienced Vichaichan — who was also the son of one of the most westernized member of the elite to ascend the throne — over the young, unknown and radical Chulalongkorn.[14]

Crisis Fire within the Grand PalaceIn early December 1874, Vichaichan received an anonymous letter threatening his life, in response to the letter he mobilized up to 600 troops and quartered them within his own Palace. As tensions grew the king also mobilized his own troops, however this underlined the fact that the Front Palace's guards were more numerous and better equipped than the King's own, as well as creating great unease and tension between the two kings.[15] On the night of the 28 December a mysterious fire broke out after a small explosion within the walls of the Grand Palace, the fire spread and was in danger of consuming the King's own residential halls and the Temple of the Emerald Buddha (วัดพระแก้ว) itself.[10][15]

The Front Palace guards immediately set off across the Sanam Luang (สนามหลวง)from their quarters to help extinguish the fire. When they arrived, they were turned away by the suspicious Royal guards, who suspected that the fire was started by the Front Palace as an excuse to enter the Grand Palace under false pretense.[10] The fire was however soon extinguished. During the episode Vichaichan remained at his palace, rather than leading his men into the Grand Palace. This act was contrary to ancient custom, which dictated that the Front Palace must take an active role in defending the Royal compound and the king in any situation. Using this pretext Chualongkorn ordered his guards to immediately surround to the Front Palace compound in attempt to contain the situation.[8][9][15]

Once the conflict began, Chulalongkorn and his ministers agreed instantly that the only person with enough clout to settle the crisis was the ex-regent Si Suriyawongse, who was in Ratchaburi (ราชบุรี) to the west of Bangkok. The king commented privately that he was being forced to "Swim to the crocodile", this reinforced the fact that the king was still incapable of asserting his will over the nobility, and needed the help of others to rule.[15] Si Suriyawongse took immediate action, seeing an opportunity to redress the balance of power between the king and Vichaichan and perhaps increase his own influences. First he advised the king to strip Vichaichan of the rank of Second King but allow him to keep the title of Front Palace. At the same time he wrote, hinting to the acting Consul-General a Mr. Newman[16] (Knox having returned to England earlier that year) that given the situation, he should send a British gunboat to protect British lives and interests. The Royal Navy steam frigate HMS Charybdis was immediately despatched from Singapore to the Chao Phraya (แม่น้ำเจ้าพระยา) river for this purpose.[16] Lastly he wrote to Prince Vichaichan, hinting that Chulalongkorn favoured his execution as punishment for the crisis,[17] when in truth Chulalongkorn only wanted to curb the Front Palace's power over men and weapons.[15] This gave Si Suriyawongse the power to mediate between the different factions within the crisis to boost his own control.[17]

Escape to the ConsulateIn the early hours of 2 January 1875, Vichaichan fled his palace to seek refuge in the British Consulate (south of Phra Nakhon (พระนคร), in Bang Kho Laem - บางคอแหลม)[18] and under protection and support of the British Government. Vichaichan was immediately condemned by a council of high officials (convened by Si Suriyawongse), a resolution was written accusing the Prince of seeking foreign intervention in an internal dispute at the expense of national sovereignty and royal authority. Chulalongkorn intervened before the document could be passed, by suggesting simply that they should try to invite the Front Palace to return instead. Vichaichan refused reconciliation and remained in the British Consulate with the support of both the British and French representatives.[19]