Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Chronik Thailands = กาลานุกรมสยามประเทศไทย. -- Chronik 1889 (Rama V.). -- Fassung vom 2017-01-27. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/chronik1889.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2013-09-23

Überarbeitungen: 2017-01-27 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-05-31 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-05-18 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-02-13 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-01-04 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-10-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-10-01 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-09-04 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-07-11 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-06-19 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-06-03 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-05-02 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-04-21 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-30 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-04 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-02-21 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-01-07 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-12-18 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-11-12 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-08-24 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-03-02 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-11-26 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der

Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche

Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Herausgebers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Thailand von

Tüpfli's Global Village Library

ช้างตายทั้งตัวเอาใบบัวปิดไม่มิด

|

Gewidmet meiner lieben Frau Margarete Payer die seit unserem ersten Besuch in Thailand 1974 mit mir die Liebe zu den und die Sorge um die Bewohner Thailands teilt. |

|

Bei thailändischen Statistiken muss man mit allen Fehlerquellen rechnen, die in folgendem Werk beschrieben sind:

Die Statistikdiagramme geben also meistens eher qualitative als korrekte quantitative Beziehungen wieder.

|

1889

Rebellion in San Sai (สันทราย) unter der Führung von Phraya Phap [พญาผาบ = Phraya Prapsongkhram - พระยาปราบสงคราม], um Chinesen und Siamesen loszuwerden. Anlass ist die Einführung einer Betelnusspalmen-Steuer (Areca catechu L.). Die Rebellion wird niedergeschlagen.

Abb.: Lage von San Sai (สันทราย)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1889

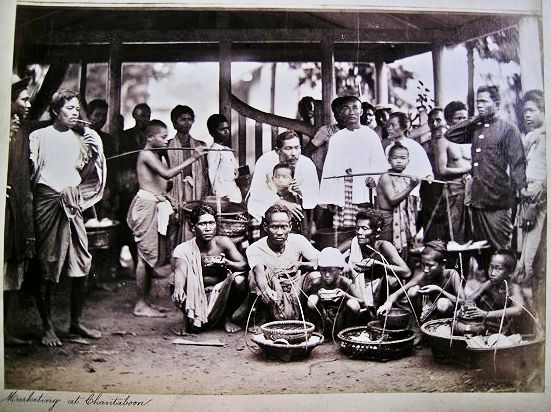

Abb.: Markt, Chantaburi (จันทบุรี), 1889

Abb.: Lage von Chantaburi (จันทบุรี)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1889

Abb.: Frauen, Suphanburi (สุพรรณบุรี), ca. 1889

Abb.: Lage von Suphanburi (สุพรรณบุรี)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1889

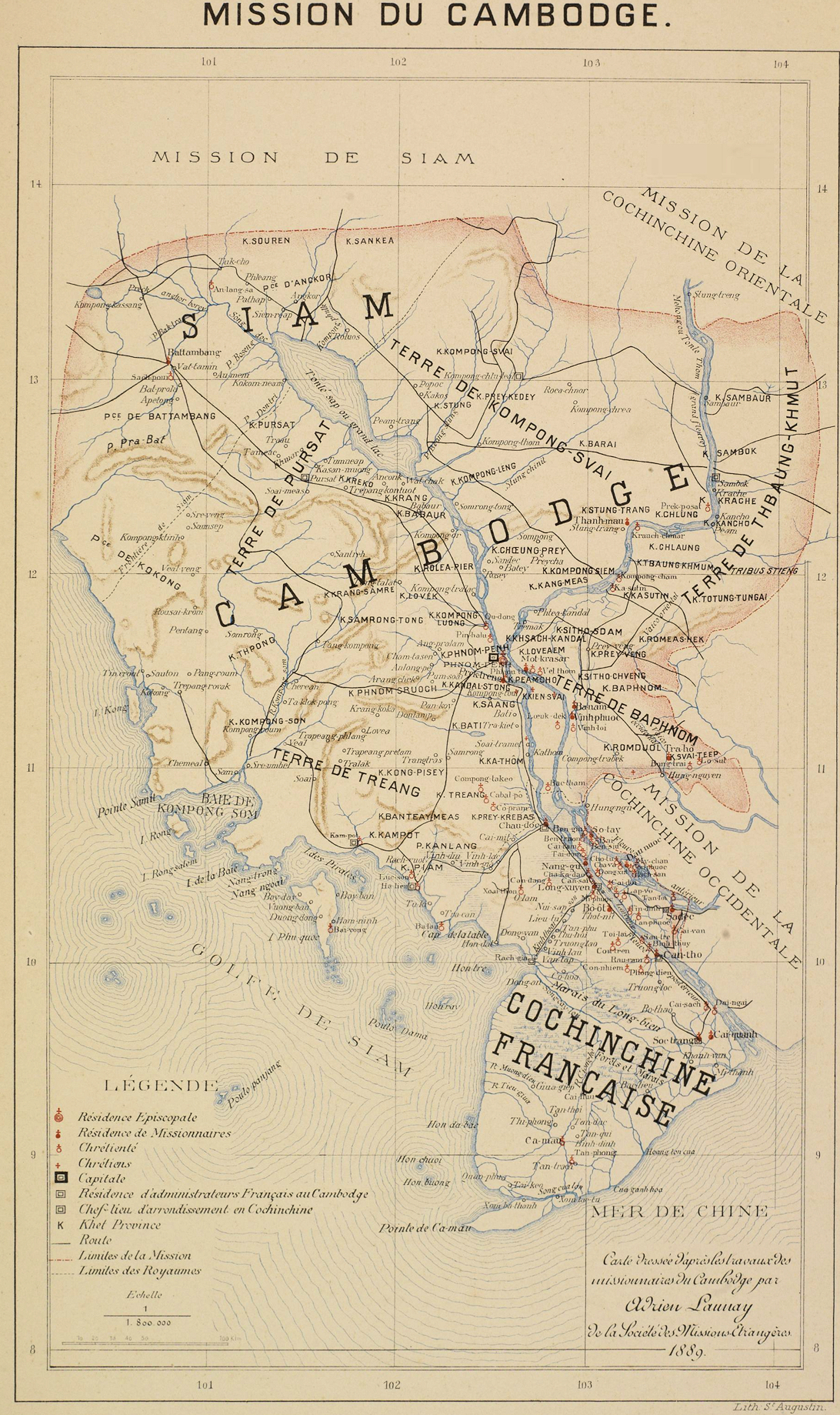

Abb.: Mission du Cambodge : carte dressée d'apres travaux des missionaires du

Cambodge / par Adrien Launay <1853-1927> de la

Société des Missions Etrangéres, 1889

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

1889

Neuer Palast des Gouverneurs in Phatthalung (พัทลุง) (Wang Chao Muang Phatthalung - Wang Mai - วังเจ้าเมืองพัทลุง – วังใหม่).

Abb.: Lage von Phatthalung (พัทลุง)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1889

Gründung einer Straßenbahngesellschaft in Bangkok.

Abb.: Straßenbahn in Bangkok, 189x

[Bildquelle: Sammlung Ric Francis]

"Siam, at this period in the eighties, was singularly lacking in means of land communication. The roads, where they existed at all, were mere tracks, and the railway was absolutely unknown. This state of affairs could not long exist in the presence of the new spirit which was animating Siamese life. The spell of Oriental indifferentism was broken in 1889, when a tramway company was formed at Bangkok. The enterprise was an immediate success, a dividend of 10 per cent, being paid on the capital. The line at the outset was a horse tramway of the ordinary type, but the management wisely in 1892 adopted electricity as the motive power, and it therefore happened that the Bangkok people were amongst the first in the East to enjoy the pleasures of a well-equipped electric tramway. " "The tramways, of the Siam Electricity Company, Ltd., are of a total length of 11.83 miles, single line with 46 sidings, divided into the following sections

Bangkolem line 5.63 miles Samsen line 5.37 miles Asadang line 0.33 miles Rachawongs line 0.50 miles The Bangkolem line runs from a point opposite the flagstaff at the royal palace through several minor streets in the city to Seekak Phya Sri, and thence along the entire length of New Road, the main artery of Bangkok, to Bangkolem Point on the River Menam. There is a very heavy traffic on this line, about 25,000 passengers being carried daily. It is extremely difficult to accommodate so many persons on a single line, but so far the Government authorities have not given their consent to a double line being laid, owing to the narrowness of the New Road. Trail cars, however, will soon be put in use and will relieve the difficulty.

The Samsen line connects-the suburbs Bangkrabu and Samsen with the city, through which it runs to a point near the Paknam railway station, cutting the Bangkolem line at the Royal Barracks and Sam Yek.

The Asadang and Rachawongs lines connect landings on the river with the main lines.

The rails arc grooved, 79 lbs. per yard, joined with substantial fishplates and copper bonded. The over-head material consists of double hard drawn copper wire, No. 00, and overhead feeders. The system is divided in six feeder sections with automatic switches.

Excepting ten obsolete cars, most of the cars are of the General Electricity Company (Schenectady) make. Up to the present only single motor-cars of 25-37 h.p. have been used, but double motor-cars with trail-cars are now being introduced. The car bodies are of teak-wood and constructed locally. There is accommodation for 126 cars in the company's three car-sheds, while the workshop has room for 14 more.

The total daily car-mileage on the company's lines is 5,130, of which 2,617 are run on the Bangkolem line. The number of cars in daily traffic is 48. Great trouble has been taken by the management to assure exact time and to avoid delays, with the result that there is now immediate connection at all junctions. Curs are run at four-minute intervals on all the company's lines. A remarkable feature about the traffic is the small number of accidents which take place. This result is achieved by careful inspection and strict rules. The operators, all of whom are natives, are remarkably well paid, but heavily fined or dismissed in case of carelessness."

[Quelle: C. Lamont Groundwater in: Twentieth century impressions of Siam : its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources / ed. in chief: Arnold Wright. -- London [etc.] : Lloyds, 1908. -- S. 191]

1889

Ein Inserat des Verlags Rongphim Wat Ko [โรงพิมพ์วัดเกาะ] des Verlegers Sin sagt, dass der Verlag ca. 200 Titel auf Lager hat, darunter einige Erstveröffentlichungen. Die Bücher würden zu Hunderten und Tausenden verkauft.

Abb.: Einbandtitel einer der Verlagsproduktionen

1889

Außenminister Prinz Devavongse Varoprakarn (สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ กรมพระยาเทวะวงศ์วโรปการ, 1858 – 1923) besucht Japan. Er will einen gleichberechtigten Handelsvertrag mit Japan. Der Japaner Toshiki Masao wird von Siam als Rechtsberater angestellt.

1889

Die Berliner Siemens-Werke liefern über Siemens Brothers, London, nach Siam:

Telegrafenapparate

Eisenbahnsicherungsgeräte

Mess- und Kontrollapparate

Blitzableiter

Fernsprecher für die Armee

1889

Gründung der protestantischen Missionsstation in Ratchaburi (ราชบุรี)

Abb.: Lage von Ratchaburi (ราชบุรี)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1889 - 1894

Captain Henry Mitchell Jones (1831 - 1916) ist britischer Minister Resident and Consul-General.

1889

Stellungnahme von British India zur Frage der Rechte auf die Trans-Salween-Shan-Staaten:

Abb.: Lage der Trans-Salween-Staaten

[Bildquelle: Crosthwaite, Charles Haukes Todd <1835 - 1915>: , 1912. -- Vor S. 209]

"The following are the views of the Commissioners as adopted by the British government for transmission to the Thai government (summary): 1. As regards Trans-Salween Karenni [ကယားလူမျိုး]: There is no convincing proof for the claims of the Karenni Chief for the possession of the Mé Ngé and Mé Té Valleys... Her Majesty's Government are therefore ready to draw the boundary line between Karenni and Siam, so as to include the heads of the Mé Ché River. The whole of the Mé Pa Valley, and then to cut the east bank of the Salween [သံလွင်မြစ်] at a point opposite the British and Karenni boundary on the Western bank.

As regards the inhabitants, the population of the south of the Mé Pai and its tributaries was found to consist of a mixture of Shans [တႆး], White Karens [ကညီကလုာ်] and Red Karens [ကယားလူမျိုး]; in the district including the Mé Pai and its tributaries north and south, it consisted almost exclusively of Red Karens (or Karenni), who proved that they had occupied the country for at leas thirty or forty years; while in the north or Pilu section of Trans-Salween Karenni, the population was proved to be entirely Karenni, with Headmen of their own, who still acknowledge allegiance to the Karenni Chief.

The occupation of these people had been continuous for fully thirty or forty years, and they deposed that they had been the exclusive owners of the teak forests during that period.

The population of these three districts were all in favour of Karenni rule, and anxious to remain under the Karen chief.

The rightful boundary between Trans-Salween Karenni and Siam is therefore that laid down on the accompanying map, which has been drawn up by the British Commissioners.2. As regards Trans-Salween Mokmai, the Muang Mau and Mesakun districts:

The inhabitants of Muang Mau, estimated to number about 1500, were ascertained to be all Shans, and for the most part natives of Maukmai, or descendants of Maukmai settlers. Mesakun is a very wild and slightly populated district containing only about 400 inhabitants, all Shan settlers from the west of the Salween.

Her Majesty's government therefore considers that these two districts clearly belong to Mokmai, and as such are tributary to Great Britain.

3. As to Trans-Salween Muang Pan [Mong Pan - မိုင်းပန်မြို့], comprising the four small districts of Muang Tau, Muang Chuat, Muang Hang, and Muang Tuen.

These districts were visited by the Commission and the necessary steps were taken by them to carry out their administration by the British feudatory state of Muang Pan in accordance with the notice conveyed to the Siamese government by Her Majesty's Chargé d'Affaires on October 23, 1889.

Her Majesty's government must now decline to reopen the question of the claim of Siam to these territories.

4. and 5. As regards Muang Sat, Kaington (Chiengtung) [ၵဵင်းတုင် / เชียงตุง ], and the Mekong Valley States.

The whole, or the greater part of the Muang Sat lies beyond the Salween system, and geographically, it is more nearly connected with Kaington than with any other state. Its political connection is also with Kaington, and Kaington officials were in possession there in March last. Her Majesty's government has therefore come to the conclusion that this state should be recognised as belonging to Kaington.

While the Commission was engaged with the frontier questions above referred to, the state of Kaington tendered its submission to Great Britain; with its adjacent feudatories it became territory subject to the protection of the Indian government. "

[Zitiert in: Manich Jumsai [มานิจ ชุมสาย] <1908 - 2009>: History of Anglo-Thai relations. -- 6. ed. -- Bangkok : Chalermnit, 2000. -- 494 S. : Ill. ; 21 cm. -- S. 301 - 305]

1889

Die britische Verwaltung Singapurs meldet an das britische Foreign Office, dass Russland plant

Abb.: Lage von Tongkah (ทุ่งคา) - Phuket town (นครภูเก็ต)

[Bildquelle: Scottish Geographical Magazine, 1886. -- Public domain]

"to make Tongkah [ทุ่งคา] (Phuket town [นครภูเก็ต]) her headquarters, as long as possible whilst she preyed upon British commerce." [Zitiert in: Mackay, Colin <1936 - >: A history of Phuket and the surrounding region. -- Bangkok : White Lotus, 2013. -- 438 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN 978-974-480-195-1. -- S. 298]

Auf Druck Großbritanniens und Japans bricht Siam entsprechende Verhandlungen mit Russland ab.

1889

Phuket (ภูเก็ต): Bau des San Chao Saeng Tham Schreins des chinesischen Tan-Clans. Bauherr: Luang Amnat Nararak

1889

In den britischen Straits Settlements gibt es weniger als 30.000 chinesische Frauen. Davon sind 3.673 als Prostituierte registriert.

1889

Bangkok: Niederlassung des US-Nähmaschinenherstellers Singer Manufacturing Company. Es ist die erste Niederlassung einer US-Firma in Siam.

Abb.: Werbekarte der Firma Singer bei der Weltausstellung Chicago 1893. Dargestellt ist ein Paar aus Ceylon

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: "All Nations use Singer sewing machines": Werbekarte der Firma Singer bei der Weltausstellung Chicago 1893. Dargestellt sind: Italien, Spanien, Tunis, Manila (philippinen), Bosnien, Japan, Burma, Serbien, Norwegen, Indien, Schweden, Portugal, Rumänien

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

1889

Der Fürst von Nan (น่าน) unterwirft Muang Sing (ເມືອງສີງ).

Abb.: Lage von Nan (น่าน) und Muang Sing (ເມືອງສີງ)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Der Myosa von Muang Sing (ເມືອງສີງ) mit seinem Hofstaat

Muang Sing (laotisch ເມືອງສີງ, auch Müang Sing geschrieben) ist eine Stadt in der Provinz Luang Namtha (ຫຼວງນໍ້າທາ) im Norden von Laos, etwa 14 Kilometer von der Grenze zu China entfernt. Der Ort liegt in einer etwa 700 Meter hohen Talebene inmitten von hohen Bergen am Fluss Nam Sing und wurde nachweisbar seit 1792 besiedelt. Ab 1885 war er die Hauptstadt eines Müang (ເມືອງ, Fürstentum) der Tai Lü (ໄທລື້). In den 1890er-Jahren stießen hier die Kolonialansprüche Frankreichs und Großbritanniens zusammen. 1916 wurde es in das französische Kolonialreich eingegliedert. [...]

Politische GeschichteMuang Sing war seit seiner Gründung durch Lü-Herrscher von Chiang Khaeng von den Birmanen abhängig und lieferte, wie Chiang Kheang, über lange Jahre jährlichen Tribut in die birmanische Hauptstadt Ava. Nach der dunklen Zeit birmanischer Wirren, löste sich Chiang Khaeng von Ava und errichtete 1885 mit Muang Sing eine neue Hauptstadt, die gegen etwaige birmanische Vergeltungsangriffe besser zu verteidigen war. Beim Umzug der Hauptstadt wanderte auch deren Name mit und in vielen Dokumenten der folgenden Zeit wurde Muang Sing als Chiang Khaeng bezeichnet.[1]

Gleichzeitig beanspruchte aber auch das Müang Nan in Nordthailand die Herrschaft über dieses Gebiet. Durch eine Militäraktion setzte Nan den territorialen Anspruch 1889 durch. Wie Nan war Muang Sing ab 1890 Vasall des siamesischen Königs Chulalongkorn (Rama V.). 1895/96 ging Muang Sing im Kolonialreich Französisch-Indochina auf, dessen Kolonialherr Siam militärisch unter Druck gesetzt und für die Abtretung großer Gebiete am östlichen Ufer des Mekong gesorgt hatte. Die Franzosen waren nicht gerne gesehen, weshalb zwischen 1907 und 1911 Konflikte ausbrachen und der Herrscher von Muang Sing in das benachbarte, ebenfalls von Tai Lü beherrschte Müang Chiang Hung (เชียงรุ่ง) im südchinesischen Gebiet Sipsongpanna (สิบสองปันนา / 西雙版納傣族自治州) fliehen musste. Die Franzosen setzten ihn 1916 ab und unterstellten Muang Sing direkt ihrer Kolonialverwaltung.

1946 überfiel die Kuomintang (中國國民黨) von China aus Muang Sing und zerstörte teilweise den Markt. 1954 verließen die Franzosen Laos vollständig.

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muang_Sing. -- Zugriff am 2014-12-12]

1889

Es erscheint:

Hallett, Holt: My First Visit to Zimmé [Chiang Mai - เชียงใหม่]. -- In: Blackwood's Edinburgh magazine. -- Vol. 146 (1889). -- S. 327ff.

"The method practised when consulting the beneficent spirits—who like mortals are fond of retaliating when provoked—is as follows: When the physician’s skill has been found incapable of mastering a disease, a spirit-medium—a woman who claims to be in communion with the spirits—is called in. After arraying herself fantastically, the medium sits on a mat that has been spread for her in the front veranda, and is attended to with respect, and plied with arrack by the people of the house, and generally accompanied in her performance by a band of village musicians with modulated music. Between her tipplings she chants an improvised doggerel, which includes frequent incantations, till at length, in the excitement of her potations, and worked on by her song, her body begins to sway about and she becomes frantic and seemingly inspired. The spirits are then believed to have taken possession of her body, and all her utterances from that time are regarded as those of the spirits. On showing signs of being willing' to answer questions, the relations or friends of the sick person beseech the spirits to tell them what medicines and food should be given to the invalid to restore him or her to health; what they have been offended at; and how their just wrath may be appeased. Her knowledge of the family affairs and misdemeanors generally enables her to give shrewd and brief answers to the latter questions. She states that the Pee [ผี]—in this case the ancestral, or, perhaps, village spirits—are offended by such an action or actions, and that to propitiate them such and such offerings should be made. In case the spirits have not been offended, her answers are merely a prescription, after which, if only a neighbor, she is dismissed with a fee of two or three rupees and, being more or less intoxicated, is helped home. In case the spirit medium’s prescription proves ineffective, and the person gets worse, witchcraft is sometimes suspected and an exorcist is called in. The charge of witchcraft means ruin to the person accused, and to his or her family. It arises as follows : The ghost or spirit of witchcraft is called Pee-Kah [ผีกะ]. No one professes to have seen it, but it is said to have the form of a horse, from the sound of its passage through the forest resembling the clatter of a horse’s hoofs when at full gallop. These spirits are said to be reinforced by the deaths of very poor people, whose spirits were so disgusted with those who refused them food or shelter, that they determined to return and place themselves at the disposal of their descendants, to haunt their stingy and hard-hearted neighbors. Should anyone rave in delirium, a Pee-Kah is supposed to have passed by. Every class of spirits—even the ancestral, and those that guard the streets and villages—are afraid of the Pee-Kah. At its approach the household spirits take instant flight, nor will they return until it has worked its will and retired, or been exorcised. Yet the Pee-Kah is, as I have shown, itself an ancestral spirit, and follows as their shadow the son and daughter as it followed their parents through their lives. It is not ubiquitous, but at one time may attend the parent, and at another the child, when both are living. Its food is the entrails of its living victim, and its feast continues until its appetite is satisfied, or the feast is cut short by the incantations of the spirit-doctor or exorcist. Very often the result is the death of its victim. When the witch-finder is called in he puts on a knowing look, and after a cursory examination of the person, generally declares that the patient is suffering from a Pee-Kah. His task is then to find out whose Pee-Kah is devouring the invalid.

After calling the officer of the village and a few headmen as witnesses, he commences questioning the invalid. He first asks ‘ Whose spirit has bewitched you ? ’ The person may be in a stupor, half unconscious, half delirious from the severity of the disease, and therefore does not reply. A pinch or a stroke of a cane may restore consciousness. If so, the question is repeated ; if not, another pinch or stroke is administered. A cry of pain may be the result. That is one step toward the disclosure ; for it is a curious fact that, after the case has been pronounced one of witchcraft, each reply to the question, pinch, or stroke is considered as being uttered by the Pee-Kah through the mouth of the bewitched person. A person pinched or caned into consciousness cannot long endure the torture, especially if reduced by a long illness. Those who have not the wish or the heart to injure anyone, often refuse to name the wizard or witch until they have been unmercifully beaten. Or the sick person naming an individual as the owner of the spirit, other questions are asked, such as, ‘ How many buffaloes has he ? ’ ‘ How many pigs ? ’ ‘ How many chickens ? ’ ' How much money ? ’ etc. The answers to the questions are taken down by a scribe. A time is then appointed to meet at the house of the accused, and the same questions as to his possessions are put to him. If his answers agree with those of the sick person, he is condemned and held responsible for the acts of his ghost.

The case is then laid before the judge of the court, the verdict is confirmed, and a sentence of banishment is passed on the person and his or her family. The condemned person is barely given time to sell or remove his property. His house is wrecked or burnt, and the trees in the garden cut down, unless it happens to be sufficiently valuable for a purchaser to employ an exorcist, who for a small fee will render the house safe for the buyer; but it never fetches half its cost, and must be removed from the haunted ground. If the condemned person lingers beyond the time that has been granted to him, his house is set on fire, and, if he still delays, he is whipped out of the place with a cane. If he still refuses to go, or returns, he is put to death.

Some years ago a case came to the knowledge of the missionaries, where two Karens [กะเหรี่ยง] were brought to the city by some of their neighbors, charged with causing the death of a young man by witchcraft. The case was a clear one against the accused. The young man had been possessed of a musical instrument, and had refused to sell it to the accused, who wished to purchase it. Shortly afterward he became ill and died in fourteen days. At his cremation, a portion of his body would not burn, and was of a shape similar to the musical instrument. It was clear that the wizards had put. the form of the coveted instrument into his body to kill him. The Karens were beheaded, notwithstanding that they protested their innocence, and threatened that their spirits should return and wreak vengeance for their unjust punishment. In Mr. Wilson’s opinion, the charge of witchcraft often arises from envy or from spite, and sickness for the purpose of revenge is sometimes simulated. A neighbor wants a house or garden, and the owner either requires more than he wishes to pay or refuses to sell. Covetousness consumes his heart, and the witch-ghost is brought into action. Then the covetous person, or his child, or a neighbor falls ill, or feigns illness; the ailment baffles the skill of the physician, and the witch-finder is called in. Then all is smooth sailing, and little is left to chance.”

[Zitiert in: Siam : the land of the white elephant, as it was and is : early first-hand accounts and descriptions of Siam and the Siamese / by J.B. Pallegoix ... [et al.] ; compiled by George B. Bacon [1836 - 1876] ; revised by Frederick Wells Williams [1857 - 1928]. Reprint der ed New York 1893. -- Bangkok : Orchid, 2000. -- 296 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- (Itineraria Asiatica ; Thailand ; vol. 8). -- ISBN 9748304744.. -- S. 223 - 228]

1889

Es erscheint:

Branda, Paul [= Réveillère, Paul-Émile-Marie] <1829-1908>: Le Haut-Mékong ou le Laos ouvert. -- Nouvelle éd. -- Paris : Fischbacher, 1889. -- 88 S. ; 2 Kt.

Abb.: Titelblatt

Abb.: Karte des Mekong (Sông Mê Kông / មេគង្គ / แม่น้ำโขง / ແມ່ນ້ຳຂອງ)

[a.a.O.]

Abb.: Karte der Mekong-Fälle (ນ້ຳຕົກຕາດຄອນພະເພັງ)

[a.a.O.]

1889

Es erscheint:

Lanessan, Jean-Marie Antoine Louis de <1843 - 1919>: L'Indo-Chine française : étude politique, économique et administrative sur la Cochinchine, le Cambodge, l'Annam et le Tonkin. -- Paris : Alcan, 1889. -- 760 S. : 5 Karten

Abb.: Titelblatt

"Politiquement et administrativement, le peuple ne connaît guère autre chose que le bon plaisir du monarque et des princes qui se partagent le pays et l’exploitent à leur guise. Les autorités siamoises ne sont pas sans avoir quelques prétentions à copier les nations européennes. Les princes se font volontiers instruire en Angleterre, se servent de la langue anglaise et copient les coutumes européennes. Le gouvernement cherche à s’outiller militairement à l’instar de l'Europe et dépense de grosses sommes en achats d’armes et de navires, mais la défiance qu’il montre à peu prés également ou tour à tour à toutes les nations de l’Europe et l’isolement qui en est la conséquence ne sont pas faits pour rendre rapide la marche du progrès. Elle est d’ailleurs entravée plus sûrement encore par le désordre administratif et financier le plus déplorable. Cependant le pays est riche et s’ils étaient convenablement gouvernés ses habitants pourraient jouir d’une grande prospérité, surtout dans le delta du Mé-Nam [Chao Phraya - แม่น้ำเจ้าพระยา] où ils sont agglomérés." [a.a.O., S. 27]

1889

Paris: Eröffnung des Musée Guimet (heute: Musée national des arts asiatiques - Guimet)

Abb.: Lage des Musée Guimet

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"Le musée national des arts asiatiques - Guimet, abrégé en MNAAG et appelé encore couramment musée Guimet, est un musée d'art asiatique situé à Paris, 6 place d'Iéna, dans le 16e arrondissement. Conçu, lors de sa rénovation, en 1997, comme un grand centre de la connaissance des civilisations asiatiques au cœur de l’Europe, il présente aujourd'hui, regroupée dans un espace qui leur est dédié, l'une des plus complètes collections d'arts asiatiques au monde. Ce site est desservi par la station de métro Iéna.

HistoireLe musée s'est constitué à l'initiative d'Émile Guimet (1836-1918), industriel et érudit lyonnais. Grâce à des voyages en Égypte (le musée de Boulaq l'inspirera pour la muséographie de ses futurs musées), en Grèce, puis un tour du monde en 1876, avec des étapes au Japon, en Chine et en Inde, il réunit d'importantes collections d'objets d'art qu'il présenta à Lyon à partir de 1879.

Par la suite, il se spécialise dans les objets d'art asiatiques et transfère ses collections dans le musée qu'il fait construire à Paris et qui est inauguré en 1889. En 1927, le musée Guimet est rattaché à la Direction des musées de France et regroupe d'autres collections et legs de particuliers. C'est désormais la plus grande collection d'art asiatique hors d'Asie.

Entre 1878 et 1925, un musée indochinois4, conséquence des découvertes de l'explorateur Louis Delaporte, occupe un tiers de l'aile Passy du palais du Trocadéro ; les objets présentés sont ensuite transférés au musée Guimet, sauf 624 plâtres du temple d'Angkor qui restent au Trocadéro, donnés en 1936 au musée des monuments français, qui se trouve dans le nouveau palais de Chaillot5,6.

Le musée Guimet gère aussi le Panthéon bouddhique - Hôtel Heidelbach7, tout proche, et le musée d'Ennery consacrés, eux aussi, à l'art asiatique. Toutefois, alors que les collections sont réparties dans le musée par aire géographique et selon une évolution stylistique ayant pour but la connaissance de l'histoire des arts de l'Asie, l'approche du panthéon bouddhique est plus liée au projet originel d'Émile Guimet puisque son but est, par le choix d'objets particulièrement signifiants sur le plan iconographique, la connaissance des religions, en l'occurrence celles des formes de bouddhismes extrême-orientaux (Chine-Japon).

À l'heure actuelle les collections du musée, relativement exhaustives sur le plan de la répartition géographique de l'Asie Orientale, se limitent aux objets archéologiques ou d'arts anciens et excluent l'art contemporain et les objets ethnologiques. On peut noter toutefois une forme de diversification avec la création d'un département des textiles grâce au legs de Krishnâ Riboud.

Une place, bien que peu importante, est également parfois accordée à l'art contemporain en marge des expositions temporaires. En ce qui concerne les collections ethnologiques ou celles en marge des grands courants culturels et religieux (production des populations autrefois qualifiées de tribales), ils trouveront désormais leur place dans le cadre du Musée du quai Branly.

S'adaptant à l'évolution du monde muséal dans lequel les missions du musée s'étendent à celles d'un centre culturel, le musée organise des manifestations culturelles liées aux cultures de l'Asie : rétrospectives cinématographiques, récitals et concerts, spectacles de danse et de théâtre.

La bibliothèque et la toiture ont été inscrites au titre des monuments historiques par un arrêté du ."

[Quelle: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mus%C3%A9e_national_des_arts_asiatiques_-_Guimet. -- Zugriff am 2016-02-25]

1889

Obwohl Kambodscha französisches Protektorat ist, besteht die Palast-Kavallerie des Königs immer noch allein aus Siamesen. Am Königshof haben Siamesen auch sonst wichtige Posten inne.

1889

Die britische Royal Navy besteht aus 90.000 Mann und 300 Schiffen.

Abb.: Offiziersuniformen der Royal Navy 1837 - 1897

[Bildquelle: John Jellicoe (1859 - 1835). -- In: Swinburne, H. Lawrence (Henry Lawrence) ; Wilkinson, Norman L. <1878 ->: The Royal navy. -- London, 1907. -- Nach S. 354]

Abb.: Uniformen der Royal Navy 1850 - 1900

[Bildquelle: John Jellicoe (1859 - 1835). -- In: Swinburne, H. Lawrence (Henry Lawrence) ; Wilkinson, Norman L. <1878 ->: The Royal navy. -- London, 1907. -- Nach S. 356]

1889-01-01

Der König ordnet an, dass Jugendliche bis zum 20. Lebensjahre, die eine Schule besuchen, von Frondienst befreit sind. Männer über 20, die keinen Schulabschluss nach Standard II haben, können zum Frondienst und Militärdienst herangezogen werden. Über 20jährige können aber die Standard II-Prüfungen nachholen und sind ab dann wie andere Männer mit Standard II vom Frondienst und Militärdienst befreit.

1889-01-15

König Norodom I (ព្រះបាទនរោត្តម) von Kambodscha (1834 – 1904) erklärt dem französischen resident general, Louis Eugène Palasne de Champeaux (1840 - 1889), dass er alle Gebiete, in denen Kambodschaner (Khmer) leben, ohne Ausnahme als zu Kambodscha gehörig betrachtet (also auch die entsprechenden Gebiete in Siam und Cochinchina).

1889-02-11

Kaiser Meiji (明治天皇) von Japan proklamiert die erste Verfassung Japans (大日本帝國憲法). Damit wird Japan zur konstitutionellen Monarchie. Diese Verfassung bleibt bis 1947-05-02 in Kraft.

Abb.: Promulgation der Meiji-Verfassung (大日本帝國憲法) 1889 / von Toyohara Chikanobu (豊原周延, 1838–1912)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]Aus der Verfassung:

Kapitel I: Vom Kaiser Art. 1 Der japanische Staat wird für ewige Zeiten ununterbrochen von Kaisern regiert und beherrscht.

Art. 2 Die Krone ist den Bestimmungen des Kaiserlichen Hausgesetzes gemäss in dem Mannesstamme des Kaiserlichen Hauses erblich.

Art. 3 Die Person des Kaisers ist heilig und unverletzlich.

Art. 4 Der Kaiser ist das Oberhaupt des Staates. Er ist der Inhaber der Staatsgewalt und übt dieselbe nach den Bestimmungen der gegenwärtigen Verfassungsurkunde aus.

Art. 5 Der Kaiser übt die gesetzgebende Gewalt unter der Zustimmung des Landtages [Parlament des Kaiserreiches] aus.

Art. 6 Der Kaiser erteilt den Gesetzen die Sanktion und befiehlt deren Verkündigung und Ausführung.

Art. 7 Der Kaiser beruft den Landtag [Parlament des Kaiserreiches], eröffnet, schliesst und vertagt denselben und löst das Abgeordnetenhaus auf.

Art. 8 1Der Kaiser kann im Falle eines dringenden Bedürfnisses zur Aufrechterhaltung der öffentlichen Sicherheit oder zur Beseitigung eines öffentlichen Notstandes zu Zeiten, wenn der Landtag [Parlament des Kaiserreiches] nicht versammelt ist, Kaiserliche Verordnungen mit Gesetzeskraft erlassen.

2Solche Kaiserlichen Verordnungen sind dem Landtage bei seinem nächsten Zusammentreten vorzulegen und falls der Landtag dieselben nicht genehmigt, von der Regierung für künftig kraftlos zu erklären.Art. 9 Der Kaiser erlässt die zur Ausführung der Gesetze, zur Aufrechterhaltung des öffentlichen Friedens und der öffentlichen Ordnung und zur Beförderung der Wohlfahrt der Untertanen erforderlichen Verordnungen oder befiehlt den Erlass derselben. Solche Verordnungen dürfen jedoch in keiner Wiese ein bestehendes Gesetz ändern.

Art. 10 Der Kaiser bestimmt die Organisation der verschiedenen Zweige der Staatsverwaltung, ernennt und entlässt die sämtlichen Beamten und Militärpersonen und setzt das Einkommen derselben fest, sofern nicht Ausnahmen in der gegenwärtigen Verfassungsurkunde oder in anderen Gesetzen besonders vorgesehen sind.

Art. 11 Der Kaiser führt den Oberbefehl über das Heer und die Flotte.

Art. 12 Der Kaiser bestimmt die Organisation und die Friedenspräsenzstärke des Heeres und der Flotte.

Art. 13 Der Kaiser hat das Recht, Krieg zu erklären, Frieden zu schliessen und Verträge zu errichten.

Art. 14 1Der Kaiser erklärt den Belagerungszustand.

2Die Voraussetzungen und Wirkungen des Belagerungszustandes werden durch Gesetz bestimmt.Art. 15 Der Kaiser verleiht Adel, Rang, Orden und andere Auszeichnungen.

Art. 16 Der Kaiser gewährt Amnestie, Straferlass, Strafumwandlung und Rehabilitation.

Art. 17 1Eine Regentschaft findet den Bestimmungen des Kaiserlichen Hausgesetzes gemäss statt.

2Der Regent übt die dem Kaiser zustehenden Gewalten in dessen Namen aus."

第一章 天皇

- 第一條

- 大日本帝國ハ萬世一系ノ天皇之ヲ統治ス

- 第二條

- 皇位ハ皇室典範ノ定ムル所ニ依リ皇男子孫之ヲ繼承ス

- 第三條

- 天皇ハ神聖ニシテ侵スヘカラス

- 第四條

- 天皇ハ國ノ元首ニシテ統治權ヲ總攬シ此ノ憲法ノ條規ニ依リ之ヲ行フ

- 第五條

- 天皇ハ帝國議會ノ協贊ヲ以テ立法權ヲ行フ

- 第六條

- 天皇ハ法律ヲ裁可シ其ノ公布及執行ヲ命ス

- 第七條

- 天皇ハ帝國議會ヲ召集シ其ノ開會閉會停會及衆議院ノ解散ヲ命ス

- 第八條

- 天皇ハ公共ノ安全ヲ保持シ又ハ其ノ災厄ヲ避クル爲緊急ノ必要ニ由リ帝國議會閉會ノ場合ニ於テ法律ニ代ルヘキ勅令ヲ發ス

- 此ノ勅令ハ次ノ會期ニ於テ帝國議會ニ提出スヘシ若議會ニ於テ承諾セサルトキハ政府ハ將來ニ向テ其ノ効力ヲ失フコトヲ公布スヘシ

- 第九條

- 天皇ハ法律ヲ執行スル爲ニ又ハ公共ノ安寧秩序ヲ保持シ及臣民ノ幸福ヲ增進スル爲ニ必要ナル命令ヲ發シ又ハ發セシム但シ命令ヲ以テ法律ヲ變更スルコトヲ得ス

- 第十條

- 天皇ハ行政各部ノ官制及文武官ノ俸給ヲ定メ及文武官ヲ任免ス但シ此ノ憲法又ハ他ノ法律ニ特例ヲ揭ケタルモノハ各〻其ノ條項ニ依ル

- 第十一條

- 天皇ハ陸海軍ヲ統帥ス

- 第十二條

- 天皇ハ陸海軍ノ編制及常備兵額ヲ定ム

- 第十三條

- 天皇ハ戰ヲ宣シ和ヲ講シ及諸般ノ條約ヲ締結ス

- 第十四條

- 天皇ハ戒嚴ヲ宣告ス

- 戒嚴ノ要件及効力ハ法律ヲ以テ之ヲ定ム

- 第十五條

- 天皇ハ爵位勳章及其ノ他ノ榮典ヲ授與ス

- 第十六條

- 天皇ハ大赦特赦減刑及復權ヲ命ス

- 第十七條

- 攝政ヲ置クハ皇室典範ノ定ムル所ニ依ル

- 攝政ハ天皇ノ名ニ於テ大權ヲ行フ

[Quelle: Altmann, Wilhelm, Ausgewählte Urkunden zur ausserdeutschen Verfassungsgeschichte seit 1776, Berlin 1913, S. 309 ff. -- http://www.cx.unibe.ch/~ruetsche/japan/Japan2.htm. -- Zugriff am 2015-05-02] [Quelle: http://ja.wikisource.org/wiki/大日本帝國憲法. -- Zugriff am 2015-05-02]

1889-03-04 - 1901-09-14

William McKinley (1843 - 1901) ist Präsident der USA.

Abb.: William McKinley 1896

[Bildquelle: Puck / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

1889-03

Im Audienzsaal des Königs von Luang Prabang (ຫຼວງພະບາງ) wird ein Ölgelmelde Ramas V. in Militäruniform aufgehängt als Zeichen des Vassallentums gegenüber Siam.

Abb.: Lage von Luang Prabang (ຫຼວງພະບາງ)

[Bildquelle: Scottish Geographical Magazine. -- 1886. -- Public domain]

1889-04

Die Suan-Kulab-Schule (โรงเรียนสวนกุหลาบ) führt Studiengebühren ein: 20 Baht pro Jahr. Begründung:

- "to prevent common people (khon leo [คนเลว]) from attending the school,

- to induce students to be more regular in their attendance, and

- to defray the cost of providing midday dining facilities for the students."

[Übersetzung: Wyatt, David K. <1937 - 2006>: The politics of reform in Thailand : education in the reign of King Chulalongkorn. -- New Haven : Yale UP, 1969. -- 425 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- (Yale Southeast Asia studies ; 4). -- SBN 300-01156-3. -- S. 121]

1890 wird die Studiengebühr ersetzt durch ein Pfandsystem. Zu Beginn des Studienjahr muss man 12 Baht hinterlegen. Für jeden Monat, in dem Leistung und Verhalten des Schülers zufriedenstellend ist, wird ein Baht zurückgezahlt. 12 Baht entspricht dem Monatsgehalt eines einfachen Staatsbeamten.

1889-04-03

Der französische Botschafter in London macht dem britischen Außenminister den Vorschlag, Siam zu neutralisieren. Großbritannien stimmt zu, fordert aber zuerst klare Grenzziehungen. Gemischt-siamesisch-britische und gemischt-siamesisch-französische Kommissionen beginnen mit der Festlegung der Grenzen.

"No further incident of importance occurred until April 3, 1889, when the French ambassador called upon Lord Salisbury at the Foreign Office and made a proposal for the neutralisation of Siam. "They (the French Government) wished," Lord Salisbury said in a despatch to Lord Lytton, the British ambassador at Paris, "to establish a strong independent kingdom of Siam with well-defined frontiers on both sides ; and they desired to come to an arrangement by which a permanent barrier might be established between the possessions of Great Britain and France in the Indo-Chinese Peninsula. Such an arrangement would be advantageous to both countries, and would prevent the complications which otherwise might arise between them. It would be necessary, in the first instance, that the frontier between Cochin China and Siam should be fixed, and her Majesty's Government would, no doubt, desire a settlement of the boundaries of Burmah. As regards the frontier of Cochin China, the French Government did not wish to extend it to Luang Prabang, but they would propose to draw a line from a point nearly due east of that place southwards to the Mekong, and below that point to make the river the dividing-line between the two countries until it entered the territory of Cambodia. They considered that both on the French and English side the boundaries of Siam should be defined up to the Chinese frontier." Lord Salisbury was sympathetic towards the idea mooted, but cautiously declined to commit himself to fuller particulars as to the contemplated arrangements for frontier rectification between Cochin China and Siam. The matter was subsequently referred to the Indian Government for consideration, and their view was that a delimitation of the frontiers of Siam should precede an agreement between Great Britain and France for the neutralisation of that State.

The task of delimiting the frontier between British Burma and Siam was undertaken in 1889 under the auspices of a joint British and Siamese Commission. An outcome of it was the publication of an interesting report by Mr. W. J. Archer, the head of the mission, relative to the then little - known country embraced within the Mekong basin. The production tended to remove misconceptions which had arisen in the public mind relative to the great value and productiveness of the district traversed. It was shown pretty conclusively by Mr. Archer that the country was unhealthy and that the local opportunities for trade were few. The report, however, drew attention to the important position which this tract occupied in reference to the problem of through railway communication between Siam and China.

"If," Mr. Archer said, " Yunnan is to be reached by a railway from the south, it must in my opinion run up the valley of the Mekong from Chiengsen. Not only would this route offer no great engineering difficulties, but it would pass through a comparatively populous and fertile country. It is true I have not been up the right bank above Chienglap, but Mr. Garner's party, who went that way as far as Chieng Hung in the rainy season of 1867, found the route a comparatively easy one. West of this line is very broken country, and the general direction of the ridges and watercourses is west to east down to the Mekong. It is noteworthy that from Bangkok to Chieng Hung a line ascending the valleys of the Menam and the Meping to Raheng, thence the Mewang to Lakhon, thence to Chiengsen through Payao, and from Chiengsen up the main valley of the Mekong, would meet with very few engineering difficulties, and only cross a low watershed and insignificant hills, while it would pass through perhaps the most promising country of Central Indo-China."

Mr. Archer, while holding these views, pointed out that the prospects of trade in Yunnan were poor, and that with the improvement in the Shan States the probability was that the little trade there was would find its way to Burma.

Mr. Archer's report, apart from the light it cast on the political problem of the time—the adjustment of British, French, and Siamese rights on the debateable land in the basin of the Mekong—contained much information of interest concerning the people and their habits.

Writing of the two great sections into which the population was divided, he said: "The Lüs and the Laos are so much alike that without the difference of dress it would be difficult to distinguish one from the other. The men among the Lüs wear loose trousers of dark blue with a fringe of all the colours of the rainbow at the lower edge, a small double-breasted jacket, also of dark blue, with embroidery, a turban and Chinese shoes—if shod at all. The women wear a petticoat of far brighter and more variegated colours than the people further south ; a jacket very similar to those of the men and a bright turban complete a very becoming costume. The men are a comparatively tall, active race, and the women small and much fairer than their southern neighbours, with sometimes even pink cheeks. The characteristics of the people seem to me to be their extreme simplicity and good nature, and I was much struck by the entire absence of presumption and self-importance which so often distinguish petty officials in Siam."

"Our rupees and two-anna bits were in great request, but the common currency are pieces of silver usually of the shape of a half-globe and of the diameter of a rupee. Out of this bits of the value of the article to be purchased are struck with a chisel on stones placed for this purpose in a basket in the middle of the market."

"The government of Luang Prabang, which appears to be entirely in the hands of the Siamese Commissioner, compares favourably with that of nearly any other part of Siam that I know. . . . The real curse of the country appears to be the almost universal habit of opium-smoking amongst the Laos of Luang Prabang ; boys learn its use from an early age and never seem to abandon it. The result is that the people of Luang Prabang are in point of physique a far inferior race to the Laos of Chiengmai or of Nan. The women, moreover, openly drink the native liquor, though not to an intoxicating extent. Withal, they are a remarkably light-hearted race, and Luang Prabang may well be described as the town of song and merriment. As soon as the sun sets music is heard everywhere, and the strains of the somewhat monotonous Lao organ are heard usually throughout the night. A curious custom also obtains for the female respectable members of the community to promenade the streets in the evenings singing in chorus. No men are allowed in these processions, which are never interfered with, strange to say. This and other customs prevail only in the town of Luang Prabang."

About the middle of 1890 a Franco-Siamese Commission commenced the delimitation of the frontier in the districts bordering on Indo-China. The principal French official employed was M. Pavie, whom we have met before actively engaged in the patriotic enterprise of promoting French influence in Luang Prabang. M. Pavie was a man of much force of character, who had worked his way to the front by sheer ability. He first went out to Siam in 1884 as a telegraph operator on the staff employed on the construction of the line between Saigon and Bangkok. The topographical and political experience gained in the course of his work was turned by him to such good account that the French authorities, in recognition of his services, appointed him in 1888 vice-consul at Luang Prabang. From that time forward, until the appointment of the Boundary Commission, he was constantly employed in surveying and reporting on the country to the north-west of the French position. It was doubtless upon the strength of his information as to the strategic and commercial value of particular districts that the French claims, the pressing of which precipitated such a grave crisis at a later period, were based. These, as has been seen from the despatch of Lord Salisbury of April 3, 1889, previously quoted, were to the districts lying eastward of the Mekong from the point where it leaves China. The Siamese occupation of a considerable portion of this area for a long period of years was unquestionable, but their rights, it was held, were overridden by a French title based on prior ownership by Annam, now a portion of the Indo-Chinese dominions of France.

The position of the question at the time of the constitution of the Franco-Siamese Delimitation Commission is set forth in the following extract from a despatch from Captain Jones, the British minister at Bangkok, to Lord Salisbury of January 6, 1890 :— "As the existing situation of the contested districts will be maintained until modified by the decisions of the Joint Commission, Siam will continue to hold the Basin of the Mekong from (about) the 13th to the 22nd parallel of north latitude, with the exception of three small districts on this side of the Khao-Luang range, settled by the Annamites, where the routes from the east debouch from the mountains into the plains. These are :--

Ai-Lao-Dign, in latitude 17° north.

Kia-Heup, in latitude 17½° north

Kan-Muan (about) in latitude 18¼° northBeyond these to the north, the Siamese hold the districts called Pan-Ha-Thang Hok [หัวพันทั้งห้าทั้งหก / ຫົວພັນ] ('the nation of five or six chiefs'), and the French will continue to occupy Sipsong-Chu-Thai [สิบสองเจ้าไต / สิบสองจุไทย / ສິບສອງຈຸໄຕ / ສິບສອງເຈົ້າໄຕ] (' the twelve small Siamese States '), from which they have succeeded in driving the Chin Haws and other marauders."

In November, 1890, M. Pavie visited Bangkok after completing a portion of his work on the frontier. During his sojourn in the city he had frequent interviews with the Siamese Minister for Foreign Affairs and endeavoured to extract from him trading privileges and immunities on behalf of the French Mekong Trading Corporation. He even suggested that there should be free trade between Siam and French Indo-China, the object aimed at doubtless being a French monopoly of trade in the northern districts of Siam. The Siamese Government emphatically declined to entertain the proposals. M. Pavie was told by the Siamese Foreign Minister that the revenues of the kingdom were too meagre to admit of their being further diminished by such a far-reaching arrangement as that contemplated. Furthermore, the minister said that Siam was itself contemplating the construction of a railway from Bangkok to Korat, to be afterwards continued to Nong Khai on the Mekong, and he represented that it could not be reasonably expected that these extraordinary privileges would be granted to a foreign trading corporation which would be a formidable competitor for the traffic necessary for the successful working of the railway. The unyielding attitude assumed by the Siamese authorities in this matter had the effect of stimulating the French Government to further action in the disputed territory.

In July, 1891, a French force occupied a position in the Luang Prabang district. This advance was a manifest breach of the arrangement entered into with Siam, but it was justified on the ground of Siamese activity—the pushing forward of posts to points far beyond the limits of territory previously occupied. Whatever may have been the truth as to this accusation, the French advance into Luang Prabang made it perfectly clear that the adjustment of the dispute would not be easily attained.

In England a not unjust suspicion was excited by this new move, and there was a call upon the Government to pursue a strong policy in upholding the territorial integrity of Siam. The French Government appear to have felt the desirability of coming to terms with Great Britain before they took any further step. On February 16, 1892, the French ambassador proposed to Lord Salisbury that in order to avoid differences between the two Powers they should mutually pledge themselves not to extend their influence beyond the Mekong. Neither Power, it was pointed out, had yet advanced to the bank of the river, and this engagement would prevent either Power suspecting the other of a desire to encroach upon what was an essentially Siamese district. The proposal was referred by Lord Salisbury to the Government of India for their opinion, and this, when forthcoming, was entirely opposed to the conclusion of any arrangement of the kind contemplated.

Later the French Government put forward a modified proposal limiting the understanding to the Upper Mekong and embodying a pledge by the French, on the one side, that they would in no case extend their sphere of influence to the westward, and by the British, on the other, that they would not seek development to the south of it. The Indian Government liked this suggestion even less than the original one, and after a decent interval the French Government were politely given to understand that the idea could not be entertained.

Meanwhile the relations between the Siamese and the French Governments were becoming daily more strained. Lord Dufferin on February 7, 1893, in a despatch to Lord Rosebery (who had by that time become Foreign Secretary) set out the points in the dispute. "The charges brought against the Siamese Government," he wrote, "are summed up in a speech by M. Francois Deloncle, contained in the full report of the debate. M. Deloncle asserted that the Siamese persistently ignore the rights of the kingdoms of Annam and Cambodia over the whole of Laos and the territories situated on the two banks of the Mekong, and that the Government were still of the opinion expressed by their predecessors two years ago, to the effect that the left bank of the Mekong was the western limit of the sphere of French influence and that this opinion was based on the incontestable rights of Annam, which had been exercised for several centuries."

Somewhat later M. Waddington, the French ambassador in London, called upon Lord Rosebery and revived the proposal for an understanding as to the boundaries of Siam. The views of the British Government on the subject at the time are embodied in the following despatch from Lord Rosebery to M. Waddington of the date April 3, 1893 :—"... Her Majesty's Government have not attempted to express an opinion, or to enter into any discussion on the question of the proper frontier of Siam towards the French possessions. But they do not consider it admissible, and they scarcely conceive that the French Government can wish to propose that the two Governments should assume exclusive spheres of influence in territory which actually belongs or which may hereafter be assigned to Siam, and that their respective interests in the independence and integrity of the kingdom should be divided by the Mekong River. Such an arrangement has, as far as I am aware, no precedent in international practice, and seems at variance with the principle of the national independence of Siam, which both Governments wish to preserve.

"As regards territories outside of Siam, Great Britain, as I have already explained, has acquired certain rights to the east of the Mekong in virtue of her annexation of Burmah and her Protectorate of Kyangton. Some of those rights H.M. Government have arranged to cede to Siam, and the others they are proposing to cede on certain conditions to China. They have frankly explained their intentions to the French Government, who will see that they are not of a nature to give rise to uneasiness or jealousy on the part of France. But until these arrangements are completed, and they are furnished with some more definite explanations of the views of the French Government with regard to the frontiers of Siam on the east and north-east, it does not seem to them that there is a sufficiently clear basis for a formal engagement between the two Governments with regard to their respective interests and spheres of influence in these regions."

[Quelle: Arnold Wright in: Twentieth century impressions of Siam : its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources / ed. in chief: Arnold Wright. -- London [etc.] : Lloyds, 1908. -- S. 71ff.]

1889-04-23 - 1897-07-26

Cheek-Affäre:

"The only outstanding event in Siamo-American relations in the closing years of the nineteenth century was the famous Cheek case, which involved not only an important commercial venture but the then burning question of extraterritoriality. The Siamese Government had advanced large sums of money to an American, Dr. M. [Marian] A. Cheek [1853 - 1895], to enable him to work extensive teak concessions in the north. In 1892 the Government seized Dr. Cheek’s property, claiming that he had failed to carry out the terms on which the money had been loaned, chiefly in regard to paying interest. Cheek contended that this was a violation of treaty rights, and the dispute then begun was terminated only in 1897 when the two interested parties referred the case to the arbitration of Sir Nicholas Hannen, the outstanding authority of the time on extraterritoriality problems. The arbitrator found that in seizing Cheek’s property the Siamese Government had violated its treaty with the United States; and as it was not proved that Cheek had defaulted in his agreement, the Government was ordered to pay Tcs. 700,000 to the Cheek estates and also to surrender full rights over the elephants attached to his property in the north. It is hard to see any justification for President Cleveland’s optimistic comment that this judgment "cemented forever the traditional friendship and mutual confidence between Siam and the United States"; for it certainly made the Siamese more desirous than ever of throwing off the shackles of extraterritoriality." [Quelle: Thompson, Virginia <1903 - 1990>: Thailand the new Siam. -- New York : Macmillan, 1941. -- S. 204.]

"ARBITRATION OF THE CLAIM OF M. A. CHEEK AGAINST THE SIAMESE GOVERNMENT. To the Senate:

I transmit herewith, in response to the resolution of the Senate of February 24, 1897, a report from the Secretary of State in relation to the claim of

M. A. Cheek against the Siamese Government, with accompanying papers.

EXECUTIVE MANSION,

Washington, March 2, 1897.GROVER CLEVELAND.

The PRESIDENT:

In answer to the resolution of the Senate, dated February 24, 1897, requesting that that body be furnished with "all the information in possession of the Department of State relating to the claim of M. A. Cheek against the Siamese Government," I have the honor to say that the correspondence on file in this Department relating to the claim of M. A. Cheek against Siam is so voluminous that it is physically impossible to place copies of it before the Senate during the continuance of the present session. There are not less than 2,000 pages of typewritten matter. The resolution, moreover, does not call specifically for correspondence, but for information. I submit, therefore, as a substitute for the full correspondence, a brief synopsis of the case, together with copies of the most recent communications that have passed between the two Governments:"[Es folgt ein ausführlicher Bericht]

[Quelle: http://images.library.wisc.edu/FRUS/EFacs/1897/reference/frus.frus1897.i0030.pdf. -- Zugriff am 2013-11-26]

1889-05-06 - 1889-10-31

Weltausstellung Paris 1889 (Exposition universelle de Paris de 1889). Siam nimmt teil.

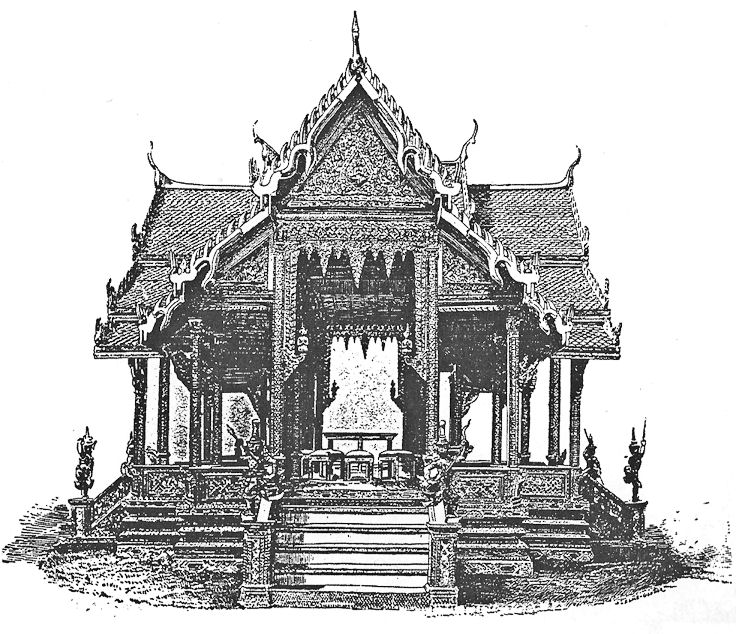

Abb.: Siamesischer Pavillon an der Weltausstellung Paris 1889 (Exposition

universelle de Paris de 1889)

1889-05-06 - 1889-10-31

Auf der Weltausstellung zeigt die Französin Herminie Cardolle (1845 - 1926) den von ihr erfundenen Büstenhalter.

Abb.: Büstenhalter von Herminie Cardolle

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Büstenhalter, Bangkok, 2012

[Bildquelle: Jill Chen. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/94489149@N00/8127012605. -- Zugriff am 2013-08-24. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

1889-05-13

USA, Oberstes Gericht: CHAE CHAN PING v. UNITED STATES.1

"The discovery of gold in California in 1848, as is well known, was followed by a large immigration thither from all parts of the world, attracted not only by the hope of gain from the mines, but from the great prices paid for all kinds of labor. The news of the discovery penetrated China, and laborers came from there in great numbers, a few with their own means, but by far the greater number under contract with employers, for whose benefit they worked. These laborers readily secured employment, and, as domestic servants, and in various kinds of outdoor work, proved to be exceedingly useful. For some years little opposition was made to them, except when they sought to work in the mines, but, as their numbers increased, they began to engage in various mechanical pursuits and trades, and thus came in competition with our artisans and mechanics, as well as our laborers in the field. The competition steadily increased as the laborers came in crowds on each steamer that arrived from China, or Hong Kong, an adjacent English port. They were generally industrious and frugal. Not being accompanied by families, except in rare instances, their expenses were small; and they were content with the simplest fare, such as would not suffice for our laborers and artisans. The competition between them and our people was for this reason altogether in their favor, and the consequent irritation, proportionately deep and bitter, was followed, in many cases, by open conflicts, to the great disturbance of the public peace. The differences of race added greatly to the difficulties of the situation. Notwithstanding the favorable provisions of the new articles of the treaty of 1868, by which all the privileges, immunities, and exemptions were extended to subjects of China in the United States which were accorded to citizens or subjects of the most favored nation, they remained strangers in the land, residing apart by themselves, and adhering to the customs and usages of their own country. It seemed impossible for them to assimilate with our people, or to make any change in their habits or modes of living. As they grew in numbers each year the people of the coast saw, or believed they saw, in the facility of immigration, and in the crowded millions of China, where population presses upon the means of subsistence, great danger that at no distant day that portion of our country would be overrun by them, unless prompt action was taken to restrict their immigration. The people there accordingly petitioned earnestly for protective legislation. In December, 1878, the convention which framed the present constitution of California, being in session, took this subject up, and memorialized congress upon it, setting forth, in substance, that the presence of Chinese laborers had a baneful effect upon the material interests of the state, and upon public morals; that their immigration was in numbers approaching the character of an Oriental invasion, and was a menace to our civilization; that the discontent from this cause was not confined to any political party, or to any class or nationality, but was well nigh universal; that they retained the habits and customs of their own country, and in fact constituted a Chinese settlement within the state, without any interest in our country or its institutions; and praying congress to take measures to prevent their further immigration. This memorial was presented to congress in February, 1879. So urgent and constant were the prayers for relief against existing and anticipated evils, both from the public authorities of the Pacific coast and from private individuals, that congress was impelled to act on the subject. Many persons, however, both in and out of congress, were of opinion that, so long as the treaty remained unmodified, legislation restricting immigration would be a breach of faith with China. A statute was accordingly passed appropriating money to send commissioners to China to act with our minister there in negotiating and concluding by treaty a settlement of such matters of interest between the two governments as might be confided to them. 21 St. p. 133, c. 88. Such commissioners were appointed, and as the result of their negotiations the supplementary treaty of November 17, 1880, was concluded and ratified in May of the following year. 22 St. 826. It declares in its first article that 'Whenever, in the opinion of the government of the United States, the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States, or their residence therein, affects or threatens to affect the interests of that country, or to endanger the good order of the said country or of any locality within the territory thereof, the government of China agrees that the government of the United States may regulate, limit, or suspend such coming or residence, but may not absolutely prohibit it. The limitation or suspension shall be reasonable, and shall apply only to Chinese who may go to the United States as laborers, other classes not being included in the limitations. Legislation taken in regard to Chinese laborers will be of such a character only as is necessary to enforce the regulation, limitation, or suspension of immigration, and immigrants shall not be subject to personal maltreatment or abuse.' In its second article it declares that 'Chinese subjects, whether proceeding to the United States as teachers, students, merchants, or from curiosity, together with their body and household servants, and Chinese laborers who are now in the United States, shall be allowed to go and come of their own free will and accord, and shall be accorded all the rights, privileges, immunities, and exemptions which are accorded to the citizens and subjects of the most favored nation.'"

[Quelle: https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/130/581. -- Zugriff am 2015-07-11]

1889-06-21

Schwere Unruhen zwischen den chinesischen Triaden ( 三合會) der Teochew (潮州人 aus Chaoshan - 潮汕) und der Fujian (福建人) auf der Charoeng Krung Road (ถนนเจริญกรุง). Anlass war, dass zwei Chinesen (Brüder), die zum Markt gingen, um 12 Dollar nach Hause zu überweisen, von einer gegnerischen Bande angegriffen wurden. Der ältere Bruder wird in den Fluss geworfen und ertrinkt.. 900 Chinesen werden verhaftet, an ihren Zöpfen zu je Hundert als Demütigung zusammengebunden und bestraft.

Abb.: Lage der Charoeng Krung Road (ถนนเจริญกรุง)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]Es gibt sechs Triaden / Kongsi / Angyi ( 三合會 / 公司 / อั้งยี่ / 红字).

Bangkok Times vom 1889-07-20 über die Bestrafung:

"The enquiry into the cases of the Chinese rioters who have been captured and sentences passed and confirmed by H.M. the King. Out of the Ang Yee [อั้งยี่ / 红字] society ringleaders, including the woman Ma Lao, eight are sentenced to receive 60 lashes each and to be imprisoned with harsh labour for terms of 7, 5 and 3 years respectively. The flogging part of the sentence was carried into effect in public, near the Central Gaol. Eight ringleaders, wearing neck chains in addition to ankle chains, then received 60 strokes each, some of them with great stoicism. The punishment concluded, the prisoners were conducted back to Gaol."

[Abgedruckt in: Burslem, Chris: Tales of old Bangkok. -- Hong Kong : Earnshaw, 2012. -- ISBN 13-978-988-19984-2-2. -- S. 98]

Abb.: Herkunft der Teochew (潮州人)

(2) und der Fujian (福建人) (3)

[Bildquelle: CIA. -- Public domain]

1889-06-22

Deutsches Reich: Gesetz, betreffend die Invaliditäts- und Altersversicherung

1889-07-14

Paris: Internationaler Arbeiterkongress: 384 Delegierte von ca. 300 Organisationen aus 20 Ländern. Gründung der Zweiten Sozialistischen Internationale.

Abb.: Die soziale Revolution (La révolution sociale) / von Félicien Rops (1833 - 1898)

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

1889-08-29

Großbritannien fordert, dass Frankreich zuerst alle Grenzstreitigkeiten mit Siam löst bevor weitere britisch-französische Verhandlungen stattfinden können.

1889-09-09

Charles Hardouin wird geschäftsführender Leiter des Französischen Konsulats in Bangkok und Chargé d'Affaires (1893 wird er Konsul). Hardouin ist Experte der französischen Gesandtschaft für siamesische Sprache und Politik. Er ist ein imperialistischer Hardliner und hat in der Folgezeit großen Einfluss in der französischen Gesandtschaft.

1889-09-30

Der französische Außenminister Eugène Spuller (1835 - 1896) gibt seine Zustimmung zur dritten Mission Pavie unter folgender Bedingung:

'...nous devons absolument limiter nos prétentions si nous voulons avoir une chance de les faire admettre sans avoir recours à une expédition militaire que l'opinion publique en France n'accepterait point.' [Zitiert in: Tuck, Patrick J. N.: The French wolf and the Siamese lamb : the French threat to Siamese independence, 1858-1907. -- Bangkok : White Lotus, 1995. -- 434 S. : Ill. ; 22 cm. -- ISBN 974-8496-28-7. -- S. 360, Anm. 42]

Abb.: Eugène Spuller

[Bildquelle: André Gill (1840–1885). -- In: Les hommes d'ajourd'hui. -- No. 38. -- Public domain]

1889 - 1891

Dritte Mission Pavie: Forschungs-, Spionage- und Eroberungsexpedition unter der Leitung von Auguste Pavie (1847 - 1925). Sie führt entlang dem Mekong (Sông Mê Kông / មេគង្គ / แม่น้ำโขง / ແມ່ນ້ຳຂອງ) von Saigon (Sài Gòn / 嘉定 / heute Ho Chi Minh City) bis Luang Prabang (ຫຼວງພະບາງ). Hauptziel ist, hitorische Quellen zu finden, die den Anspruch Frankreichs als Nachfolger Vietnams auf das Gebiet östlich des Mekong begründen. Diesen Nachweis kann die Expedition nicht erbringen.

Abb.: Lage von Saigon Saigon (Sài Gòn / 嘉定) und Luang Prabang (ຫຼວງພະບາງ)

[Bildquelle: Scottish Geographical Magazine. -- 1886. -- Public domain]

1889-10

Es erscheint

Carte politique de l’Indo-chine / par François Deloncle [1856 - 1922]. -- 1889. -- Maßstab 1 : 3.700.000.

Die Karte gibt die Ansprüche der parti colonial wieder.

Abb.: Fassung der Karte aus dem Jahr 1901

[Bildquelle: Reimach: Le Laos. -- Bd. 1. -- 1901]

Fréderic Haas, ehemaliger französischer Konsul in Mandalay (Burma), gründet das Syndicat français du Haut Laos. Direktor: Léon Tharel. Wird 1891 umgewandelt in die Handelsgesellschaft La société du Haut Laos.

1889-10-29

Abkommen von Konstantinopel zwischen dem Vereinigten Königreich, Deutschland, Österreich-Ungarn, Spanien, Frankreich, Italien, Niederlande, Russland und dem Osmanischen Reich über die Nutzung des Suezkanals: im Vertrag wurde die Neutralisierung des Kanals vereinbart. Artikel I gewährleistet die freie Durchfahrt für alle Schiffe im Krieg und Frieden. Der Vertrag gilt bis heute.

Abb.: Signatarmächte des Vertrags von Konstatinopel

Abb.: Lage des Suezkanals

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1889-11-01

Eröffnung eines Irrenhauses für 30 Patienten. Die Patienten werden angekettet oder eingesperrt.

1889-11-20

Ernennungsschreiben des Königs für Tae Tienjin (郑天浸) als palad chin [ปลัดจีน] von Trad [ตราด]:

Abb.: Lage von Trad [ตราด]

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"The letter ... appoints Tae Tienjin [郑天浸], grandson of Tae Poh, a Hokkien [福建人] patriarch of the Sreshthaputra [เศรษฐบุตร] clan, to the position of Phra Pranee-Chinpracha, the palad chin [ปลัดจีน] of Trad [ตราด], one of the eastern provinces along the coast of Siam near Batambang. The letter informs us that apart from being prominent in the Bangkok community Tae Tienjin was also the son-in-law of the late palad chin of Trad. It instructs Pranee-Chinpracha to report to the governor of Trad and the town council, and tells him to assume the responsibility of solving conflicts among Chinese. However, the letter states that conflicts between Siamese and Chinese must be considered in consultation with the governor. It enlists the responsibilities of the palad chin in the enforcement of the law, monitoring and reporting on various Chinese activities, including prevention of violence and tua hia gangster rackets that may be harmful to the community. In doing so, he may employ Chinese assistants. The palad chin, dressed in Chinese robes, must represent the Chinese community in all official functions including the ceremony to "pledge loyalty" to the king of Siam." [Quelle: Sng, Jeffery ; Pimphraphai Bisalputra [พิมพ์ประไพ พิศาลบุตร] <1945 - >: A history of the Thai-Chinese. -- Singapore : Didier Millet, 2015. -- 447 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- ISBN 978-981-4385-77-0. -- S. 194f.]

1889-11-23

Louis Glass (1845 - 1924) führt in San Francisco erstmals die von ihm erfundene Jukebox vor.

Abb.: Jukebox, die Wachszylinder abspielt

[Bildquelle: S Jones. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/82862615@N00/2751920189. -- Zugriff am 2013-09-01. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1889-11-27 - 1910-07-10

มิรซากุลามอุชเซ็น (geb. 1849) ist muslimischer Chularajamontri พระยาจุฬาราชมนตรี (สิน อหะหมัดจุฬา)

Abb.: มิรซากุลามอุชเซ็น

[Bildquelle: th.Wikipedia]

1889-12-17 - 1889-12-29

Prinz Heinrich von Preußen (1862 - 1929) besucht Siam.

Abb.: Prinz Heinrich von Preußen

ausführlich: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/ressourcen.htm

Phongpaichit, Pasuk <ผาสุก พงษ์ไพจิตร, 1946 - > ; Baker, Chris <1948 - >: Thailand : economy and politics. -- Selangor : Oxford Univ. Pr., 1995. -- 449 S. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 983-56-0024-4. -- Beste Geschichte des modernen Thailand.

Ingram, James C.: Economic change in Thailand 1850 - 1870. -- Stanford : Stanford Univ. Pr., 1971. -- 352 S. ; 23 cm. -- "A new edition of Economic change in Thailand since 1850 with two new chapters on developments since 1950". -- Grundlegend.

Akira, Suehiro [末廣昭] <1951 - >: Capital accumulation in Thailand 1855 - 1985. -- Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, ©1989. -- 427 S. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 4896561058. -- Grundlegend.

Skinner, William <1925 - 2008>: Chinese society in Thailand : an analytical history. -- Ithaca, NY : Cornell Univ. Press, 1957. -- 459 S. ; 24 cm. -- Grundlegend.

Mitchell, B. R. (Brian R.): International historical statistics : Africa and Asia. -- London : Macmillan, 1982. -- 761 S. ; 28 cm. -- ISBN 0-333-3163-0

Smyth, H. Warington (Herbert Warington) <1867-1943>: Five years in Siam : from 1891 to 1896. -- London : Murray, 1898. -- 2 Bde. : Ill ; cm.

ศกดา ศิริพันธุ์ = Sakda Siripant: พระบาทสมเด็จพระจุลจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว พระบิดาแห่งการถ่ายภาพไทย = H.M. King Chulalongkorn : the father of Thai photography. -- กรุงเทพๆ : ด่านสุทธา, 2555 = 2012. -- 354 S. : Ill. ; 30 cm. -- ISBN 978-616-305-569-9