Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Chronik Thailands = กาลานุกรมสยามประเทศไทย. -- Chronik 1898 (Rama V.). -- Fassung vom 2017-01-24. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/chronik1898.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2013-10-05

Überarbeitungen: 2017-01-24 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-12-28 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-12-03 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-02-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-11-24 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-10-10 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-07-11 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-06-23 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-05-01 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-04-16 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-28 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-16 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-02-28 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-12-13 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-12-02 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-09-21 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-08-11 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-03-08 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-02-28 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-01-13 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-11-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-11-07 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Herausgebers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Thailand von

Tüpfli's Global Village Library

ช้างตายทั้งตัวเอาใบบัวปิดไม่มิด

|

Gewidmet meiner lieben Frau Margarete Payer die seit unserem ersten Besuch in Thailand 1974 mit mir die Liebe zu den und die Sorge um die Bewohner Thailands teilt. |

|

Bei thailändischen Statistiken muss man mit allen Fehlerquellen rechnen, die in folgendem Werk beschrieben sind:

Die Statistikdiagramme geben also meistens eher qualitative als korrekte quantitative Beziehungen wieder.

|

1898 - 1902

Sultan Abdul Kadir Kamaruddin Syah (Phraya Pattani V) ist Sultan (سلطان) von Patani (ڤتاني)

Abb.: Sultan Abdul Kadir Kamaruddin Syah (Phraya Pattani V)

[Bildquelle: th.Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Lage des Sultanats von Patani (كراجأن ڤتاني)

[Bildquelle: Xufanc / Wikimedia. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]]

1898

Abb.: Phra Chao Suriyapong Paritdech (พระเจ้าสุริยพงษ์ผริตเดช - เจ้าสุริยะ ณ น่าน, 1832 - 1918), Herrscher von Nan (น่าน), 1898

Abb.: Lage von Nan (น่าน)

[Bildquelle: CIA. -- Public domain]

1898

Abb.: Amphoe Hang Dong (หางดง), 1898

Abb.: Lage der Amphoe Hang Dong (หางดง)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1898

Abb.: Birmanische Musiker, Mae Sariang (แม่สะเรียง), 1898

Abb.: Tänzerinnen, Mae Sariang (แม่สะเรียง), 1898

Abb.: Lage von Mae Sariang (แม่สะเรียง)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1898

Abb.: Schaukelfest (พิธีตรียัมปวาย / โล้ชิงช้า), Sao Ching Cha (เสาชิงช้า), Bangkok, 1898

1898

Provincial Administration Act

"THE PROVINCIAL ADMINISTRATION ACT OF 1898; THE NEW PLACE OF THE PROVINCIAL GOVERNOR

Six years after the great reorganization of 1892, the initial phase in the development of a new system of domestic government ended with a basic statute defining the structure and responsibilities of the elements of the tesapiban [เทศาภิบาล] system, supplemented by an appropriate set of rules and regulations. Twelve monthons [มณฑล] were in existence by 1898.

In the 1898 enactment, the position of the provincial governor in this new system was regularized. With the creation of the monthons, the governors were no longer the lords of their territories. The salaried governor was also flanked by two provincial boards whose purpose was to advise and assist him in the conduct of his duties, and by implication to cause him to function as a responsible governmental official rather than a semiautonomous ruler.

One board consisted of three senior (sanyabat) [สัญญาบัตร] and five junior provincial officials: the deputy governor, public prosecutor, and finance officer, and the provincial clerk, registrar, assistant prosecutor, assistant finance officer, and the governor’s secretary. Given the emphatically hierarchical character of Thai society, this board had little significance as an entity, though its statutory establishment indicated that the governor was to engage in a certain amount of consultation among his officials in the administration of his province.

The other board (krommakan nok tamnieb), [กรมการนอกทำเนียบ] appointed by the Minister of Interior on advice of the governor and the monthon commissioner, consisted of wealthy and influential residents of the province; they received honorific titles but no pay for their service. The aim of this arrangement was to increase and systematize communications between the government and wealthy leaders in the community, and to advise the governors "concerning the ways in which the livelihood of the provincial people could be improved. " These provincial consultative boards, a new departure in Thai public administration, reflected the fact that during the latter half of the nineteenth century the economy of the provinces had developed. Provincial centers contained important economic elites engaged in trade, fishing, forestry, commerce, agriculture, or mining, who were in a recognized position to contribute to the pursuit of the governmental goals of King Chulalongkorn and Prince Damrong [ดำรงราชานุภาพ, 1862 -1943].

These special boards, consisting of ten eligible persons appointed for three-year terms, were required to meet twice a year to consider the provincial annual report before it was sent to the monthon. Other meetings were called at the discretion of the governor, but board members were authorized to initiate and submit to the governor for consideration "any measure to be taken which would foster the earning of livings. " The board members also participated in an annual monthon meeting to consider the economic affairs of the provinces of the monthon.

Members of the board might be given the simulated rank of either noncommissioned or commissioned officials, and half of each board appears to have consisted of members who were granted permanent rank or title.

These advisory "citizen" boards were abolished by the Provincial Administration Act of 1922, but for two decades some of them appear to have made a contribution to the evolution of the new governmental system. Phraya Rachsena [พระยา ราชเสนา] observed that "the special officials were of great benefit.... Their positions were not obtained by flattery. They were positions of prestige and honor. The officials were induced into service not by any monetary remuneration but rather by dignity and prestige. "

It would be unwise to attach too much importance to the existence of these boards. They must have functioned in varying fashion as devices for communication and co-operation. But, in some cases, they formed a link between government and economically powerful leaders of individual communities, most of whom were Chinese. Their very existence amounted to a recognition of the importance of these groups, and implied, too, that they were more than mere subjects of an authoritarian regime. The boards represented an attempt at cooptation; they afforded the most meaningful rewards of the Thai system—official status and the prestige that went with it—to cooperative members of a blossoming provincial economic elite. The boards, established on the basis of pragmatic concerns rather than anything more, may have helped inspire the ideologically motivated provincial boards created in 1933 as an intended step toward the democratization of provincial government.

Under the tesapiban system the governor was no longer the chief judge of the province. He no longer possessed power to remove provincial officials of commissioned rank. While he continued to be formally subject to royal appointment and removal, his office was no longer quasi-hereditary. From chao muang (lord of the place) the governor had been reduced to pu warajakarn changwad [ผู้ว่าราชการ] (man in charge of the province for the king). And the change was symbolic of the basic modification which was under way in Thailand.

By the end of the nineteenth century—specifically, by 1898—the main outlines of the new Ministry of Interior had been drawn, and a new pattern of domestic government was in the making. The achievement, incomplete as it was, was stupendous. Meanwhile, significant changes occurred in the administration of justice and in tax collection —changes which were inseparably linked with the reconstruction of the Ministry of Interior."

[Quelle: Siffin, William J. <1922 - 1993>: The Thai bureaucracy: institutional change and development. -- Honolulu : East-West Center, 1966. -- 291 S. ; 24 cm. -- S. 73ff. -- Fair use]

1898

Abschaffung der richterlichen Beweisfindung durch Ordale.

1898 - 1900

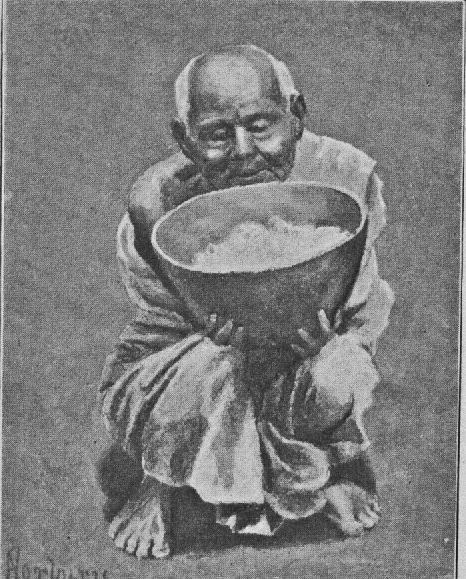

Vajirañāṇavarorasa [วชิรญาณวโรรส, 1880 - 1921] schickt 14 Mönche zur Inspektion der Klöster in den Monthons (มณฑล)

"In 1898-1900 Wachirayan [วชิรญาณวโรรส, 1880 - 1921], head of the Thammayut order [ธรรมยุติกนิกาย], sent fourteen administrative monks holding the title of education director (phu amnuaikan kanseuksa [ผู้อำนวยการการศึกษา]) to inspect monasteries in their respective monthon [มณฑล]. (A monthon was an administrative unit consisting of a number of meuangs [เมือง]. Each monthon was under the control of a resident commissioner, who had the power to override the semi-hereditary governors. See figure 3. ) All but two of the education directors were monks based in Bangkok temples. At the turn of the century most monthons were isolated from Bangkok. Only Bangkok itself and two other monthons in the southeastern region, Chanthaburi [จันทบุรี] and Prachinburi [ปราจีนบุรี], were sufficiently compact to facilitate travel and communication. In all others, the education directors could inspect only a fraction of the monasteries. Distant meuangs and their remote villages were beyond reach. The officials could not travel to the northernmost region at all. They went only as far as Uttaradit [อุตรดิตถ์], the northernmost meuang of the Central Plains. Much of the southern region remained inaccessible; large sections of monthon Phuket [ภูเก็ต] were still wild and sparsely populated. In the northeastern region, inspectors residing in Nakhon Ratchasima [นครราชสีมา] and Ubon Ratchathani [อุบล] could travel only in the vicinity of these two capital towns. [... ]

Traveling through all these remote meuangs was slow and arduous, especially in inclement weather. In each meuang the government officials provided the sangha [สังฆะ] inspectors with the best means of transportation available: a rowboat or a steamboat, a horse-drawn carriage or an oxcart on flat land, and elephants with mahouts over wet and low land. Servants and porters carried the inspectors’ supplies. But regardless of the assistance they received, the inspection trips were too long and arduous for many city-bred monks. Despite their relatively young age, some found the physical strain incapacitating. At the end of his second trip one education director was so ill he left the monkhood.

Most laypeople and local monks habitually traveled on foot or on horseback. Local monks in those days customarily kept horses in their wats and traveled on horseback, a most practical means of transportation when towns and villages were widely scattered— especially when a preacher-monk had to get to another wat in a hurry. But the visiting inspectors insisted that Bangkok’s disciplinary rules be observed. They told the local monks to get rid of their horses and stop riding them. This ruling proved impractical and could not be enforced. Monks continued to ride horses to villages where they had been invited to preach, and gifted preachers had to travel often. Even the Thammayut head of Ubon, Uan Tisso (titled Ratchamuni), had to yield to the local custom out of practicality. When in 1917-1918 he and local administrative monks went to inspect wats [วัด] in neighboring districts, all of them went by horseback. Four or five decades after the sangha centralization, local monks in the North and Northeast still traveled on horseback, and many village abbots in the Northeast still kept a few horses in their monasteries.

REGIONAL BUDDHIST TRADITIONS

The inspectors found that local monks and laypeople were observing customs foreign to Bangkok. A common feature of regional traditions was the assumption that monastics would remain engaged in village life. Regional monks organized festivals, worked on construction projects in the wat, tilled the fields, kept cattle or horses, carved boats, played musical instruments during the Bun Phawet festival [บุญผะเหวด], taught martial arts—and were still considered to be respectable bhikkhu [ภิกษุ] (monks) all the while. Cultural expectations and loyalties of kinship and community made all these activities legitimate ones for monks. Sangha officials, however, considered such activities improper, and they criticized the local monks for being lax. But as these monks saw it, they were neither improper nor lax. They had their own standards, which differed from Bangkok’s. Villagers and townspeople knew their monks—knew them well. The local elders knew who were good monks and who were bad, and they did not tolerate bad behavior.

The wat was in fact the center of lay Buddhism. In regional traditions, the monastery served many functions necessary to community life. It was a town hall for meetings, a school, a hospital (monks provided herbal medicine and took care of the sick), a social and recreation center, a playground for children, an inn for visitors and travelers, a warehouse for keeping boats and other communal objects, and a wildlife refuge (if the wat was near a forest). Village or town abbots consequently remained very much in the world, devoting their energies to community work that benefited local people.

Working with Their Hands

The Buddhist tradition that originated in the Bangkok court strongly discouraged manual work. Thammayut monks were to abstain from doing hard labor; they and their temples should instead receive gifts and donations of money and services. The Bangkok elite considered it undignified for a monk to work, sweat, or get dirty like a phrai [ไพร่] (commoner). He should look clean and neat, like a jao [เจ้า] (lord). By contrast, in many regional traditions laypeople expected a monk to perform hard labor. They expected him to be self-reliant and self-sufficient. When monks were not gifted in oratorical, artistic, or healing skills (which brought in donations), the wat had to survive any way it could. In many local traditions, monks had to work to support the monasteries by growing vegetables, tending orchards, carving boats, or raising cattle and horses. In all the monthons that they inspected, the sangha officials found that abbots as well as other monks did their own repairs and construction. Here are typical remarks from the reports: “The abbot constantly does repair work in his wat”; “he is much respected by the laity”; “the wat is well maintained, strong and clean. ” Although sangha authorities wanted temples to be well maintained and to look prosperous, they felt the burden of work should fall on the lay community.

In the countryside, however, monks often were expected to work the land because villagers feared the spirits believed to inhabit the fields. Villagers considered it auspicious to begin the new agricultural cycle by having the monks plow the paddies. Plowing was an acceptable activity for monks because it was done not for personal gain but to benefit the whole community. Villagers respected monks who performed this task. One such village (today in Loei Province) was Monk Field Village (Ban Na Phra), so named because the monks took part in plowing and harvesting as well as in performing religious ceremonies to chase away any bad spirits that might live in the fields.

From Bangkok’s perspective, however, monks who performed such work violated monastic rules. In their reports the sangha inspectors criticized local monks for devoting too much time to manual work and not enough to intellectual work (teaching from Bangkok’s texts). Some sangha inspectors did understand that lay-people expected monks to keep the monasteries in good repair and that they deemed monks lazy when they did not. Villagers, they knew, were often too busy with their own work in the fields to help the monks, who had all the necessary skills. When one inspector in the Northeast told a local abbot, “From now on, monks are forbidden to cut trees or elephant grass for thatch. Will you agree to this rule? ” the abbot replied, “If monks are not allowed to cut grass or trees, who will build our shelters or repair the wats? ” Nevertheless, this sangha inspector made everyone present at the meeting agree that manual work was improper for monks and that laypeople ought to do it.

For monks in regional traditions, the physical was inseparably entwined with the spiritual. Mundane activities could be spiritually useful when done with the proper mental attitude. Not only did monks and novices undertake construction work or repairs, they collected whatever raw materials were necessary. The revered monk Buddhadasa recalls the lengths he had to go to in order to get lumber during the 1920s. He and his abbot walked to a forest some distance away accompanied by laymen from a nearby village. After cutting the trees they needed, they floated the trunks downriver to the sea, towed them along the coast, and finally brought them upriver to their wat, where the monks sawed the logs into lumber and built their kuti (huts).

Li, a Lao monk, also recalls doing manual work as a village monk in the Northeast back in 1925. He and fellow monks went to the forest to get logs to build a preaching hall. The monks were hungry after their hard work, so they ate a meal late in the day— an offense according to the Pali vinaya. A Phu Thai [ผู้ไท / ຜູ້ໄທ] monk from a village in Sakon Nakhon [สกลนคร] recalls a similar event:

When it was time to construct a permanent building in the wat, the monks and novices had to spend the night in the forest felling trees and cutting planks. They usually brought drums along to create a lively atmosphere as a break from work. If the food supplies were inadequate, the abbot would allow some novices to disrobe temporarily and catch fish or crabs or to get other food supplies. Afterward the novices would be reordained.

When it was time to pull the logs to the wat, big rollers would be used for hauling. People of all ages—the young and old, women as well as men—came to help haul the logs. Other people would provide musical entertainment by beating drums, cymbals, and other percussion instruments all the way back to the wat. The monks, novices, and laywomen often took this opportunity to have fun together. This was all right as long as they [the monks] could keep their celibacy vows. (W, 15-16)

After this violation of disciplinary rules, a monk would seclude himself in a hut in the forest. During his solitary retreat, he would release himself from his offenses. This austere practice, called khao pariwatkam [เข้าปริวาสกรรม] (entering confinement), is part of the twelve festivals (hit sipsong [ฮีตสิบสอง]) of the Lao tradition in the Northeast and the twelve traditions of the Yuan tradition in the North (as well as in the Lan Sang [ລ້ານຊ້າງ] kingdom in Laos).

The hard labor in which monks as well as villagers participated was usually done during the slack period or at the beginning of the agricultural cycle. Village monks and abbots either helped villagers cut down trees and work the land or did all this themselves. Since villagers were often afraid of being punished by spirits that guarded the land, having monks working alongside gave them a sense of security. In the Lao tradition, it was the monks and novices who repaired and did clean-up work at sacred stupas such as Phra That Phanom [พระธาตุพนม]. Local people refused; they believed that anyone who touched, scrubbed, or climbed the stupa would sicken. In the Yuan tradition, similarly, it was the duty of the monks to clear or clean up the forest cemetery. If monks refused, nobody else would do it.

Participating in Local Festivals

Before Bangkok established control over regional Buddhist traditions, the wat and community were close. A community’s cultural life centered on the wat. When there was a festival in a town or a village, everyone including the monks participated. In the northern and northeastern regions there were as many as twelve yearly festivals. In his travels through Siam at the turn of the century, James McCarthy, a surveyor, came across monks participating in boat races in one northern community:

“The river had overflowed its banks, and a number of people, the majority being women, had assembled in their boats for races. A special feature of these races is that the boats’ crews are either all men or all women— never mixed. The women are young and marriageable, and, in fact, have only come for a grand flirtation. They challenge a boat of men to race. In the boats there are more priests than laymen, in some cases priests only."

[...]

"A widespread practice in every meuang is monks engaging in boat racing and throwing water at women.""

[Quelle: Kamala Tiyavanich [กมลา ติยะวนิช] <1948 - >: Forest recollections : wandering monks in twentieth-century Thailand. -- Honolulu : Univ. of Hawai’i Pr., 1997. -- ISBN 0824817818. -- S. 19 - 27. -- Faire use]

"The sangha inspectors’ reports provide evidence of the widespread popularity of jātakas [ชาดก] in all regions of Siam. This report is typical: "Most monks preach about alms giving, generosity, precepts, and moral conduct. Basically, the monks’ sermons consist of jātakas, especially the Great Birth story [มหาชาติชาดก]. "

In the Central Plains monks sought to master the Great Birth story

"because it is very popular among local people. "

In the South as well,

"Monks rely mostly on jātakas and the Questions of King Milinda [Milindapañhā] to propagate dhamma. "

In the northeastern region, where the Lao Buddhist tradition prevails,

"Laypeople share similar values; they prefer to listen to folk tales and jātakas, not dhamma sermons that expound doctrine. It is the villagers who choose the sermon they want to hear. They invariably choose folk stories such as Sang Sinchai, Phra Rot Meri, Phra Jao Liaplok, as well as the Wetsandon Chadok [มหาเวสสันดรชาดก]. "

In the Lao tradition, the festival of reading the Wetsandon Chadok (Vessantara Jātaka in Pali) is called Bun Phawet [บุญผะเหวด]; in the Siamese tradition it is called Mahachat [มหาชาติ] (Great Birth), and in the Yuan [ยวน] it is Tang Tham Luang [ตั้งธรรมหลวง] (Setting the Great Text). Reading this jātaka was one of the most popular of regional customs. The story tells of the Buddha’s life as the bodhisatta Wetsandon (Vessantara [เวสสันดร]) and of his last rebirth before becoming the Buddha. Local people were willing to sit all day and long into the night listening to the story when it was told dramatically. The themes of the Wetsandon Chadok are similar in different traditions, although the cultural identities of the characters vary according to local customs and languages. Prince Wetsandon, known for his generosity and selflessness, fulfills his vow to practice dāna (generosity) by giving whatever he is asked. He surrenders not only the sacred regalia of his father’s kingdom but even his own wife and children.

The sangha inspectors observed that many monks wanted to learn from their elders how to recite the story. Not everyone could be a preacher, of course: it took a lot of discipline and long training to master even a section of the Wetsandon Chadok, which consists of thirteen "chapters" (kan [ขันธ]), each chapter divided into thirty to forty sections. During the festival these chapters were assigned to particular monks and novices at the host monastery as well as to monks in neighboring monasteries who had been invited to take part. In training, however, a monk would try to recite all thirteen chapters by himself. A former preacher recalled:

"I started reciting at 7 a. m. [and] gradually I began to lose my voice. Yet I kept it up until I reached the final chapter. By then it was 6 p. m. and my voice was completely gone. For seven or eight days I had no voice. "

There were good reasons for this intensive training. In the days before microphones, a preacher had to project his voice and enunciate clearly, so that an audience of hundreds could hear him. He also had to know how to conserve his voice. Preaching improved his memory and mindfulness, which in turn helped him in his dhamma studies. Finally, he gained much merit if he succeeded in mastering the entire jātaka.

Only a master storyteller could do it well, altering his voice as he portrayed the tale’s many characters—demons, animals, old men, hermits, kings, princesses, children—evoking all the while a strong sense of involvement from his audience. In many traditions, special enclosed seats or booths helped preachers deliver their readings dramatically. In the Lan Na [ล้านนา] tradition, for example, the dhamma booth was a small enclosure in the shrine hall (wihan [วิหาร]) raised about a meter and a half above the floor. It had walls of carved wood on three sides, while the fourth was left wide open for entry by means of a ladder. As a former preacher explained,

"In this dhamma booth the monk could sit comfortably, since he could look out but the audience could not see him. He did not have to be dignified. He might remove his robes, put his hands over his ears, open his mouth widely, or tap his hands on the floor to aid his rhythm. [Instead of sitting on the floor] most preachers preferred to squat. My teacher told me that squatting lets the testicles hang naturally, so the preacher has no constraint in projecting his voice loudly. "

Bangkok authorities forbade monks to use these dhamma box seats. By doing so, they hoped to put an end to this kind of dramatic preaching.

Another integral part of a Great Birth story performance was music, especially the phin phat [ปี่พาทย์] ensemble. Inspector monks reported that in several monthons monks played various kinds of musical instruments. In every town and village large crowds of people would listen with rapt attention for hours while local monks took turns reciting stories about the Buddha’s former lives as bodhisattas [พระโพธิสัตว์]. Such stories figured more prominently in sermons than episodes from the life of the Buddha himself.

Because preaching the Wetsandon Chadok was an art requiring arduous discipline, few preachers achieved great oratorical skills. Those who did were much respected and in high demand. Their popularity was not without a price, however, as a former preacher explained:

"Often, monks with lesser skill are jealous and seek to ruin the preacher by using black magic [khun sai] [คุณไสย].

- So a good preacher must possess magical knowledge for self-protection.

- He must learn to recite sacred mantra for self-defense as well as to attract people with goodwill.

- He must tattoo protective amulets on his body for the same reason.

- He must always keep certain kinds of amulets or magic cloth [pha yan] [ผ้ายันต์] to make him invulnerable. "

[Quelle: Kamala Tiyavanich [กมลา ติยะวนิช] <1948 - >: Forest recollections : wandering monks in twentieth-century Thailand. -- Honolulu : Univ. of Hawai’i Pr., 1997. -- ISBN 0824817818. -- S. 30ff.. -- Faire use]

Abb.: Lage von meuang Ranong [เมืองระนอง]

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]"An incident in the southern region illustrates what happened when a sangha official introduced a Bangkok holy day with its recommended sermon. During his inspection trip in 1900 to meuang Ranong [เมืองระนอง] in the South, the sangha inspector wanted to demonstrate how Wisakha Bucha [วิสาขบูชา] should be observed. The ceremony, attended by some seventy local people, was supposed to last from 8 p. m. until dawn. Soon after the official monk started preaching the Mahabhinikkhamana Sutta, however, the laypeople started to leave. By the time the monk got to the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, only one person—the lay leader—remained in the audience. The abandoned sangha official commented in his report,

"People in this town have no appreciation or respect for dhamma sermons. ""

[Quelle: Kamala Tiyavanich [กมลา ติยะวนิช] <1948 - >: Forest recollections : wandering monks in twentieth-century Thailand. -- Honolulu : Univ. of Hawai’i Pr., 1997. -- ISBN 0824817818. -- S. 34. -- Faire use]

"To restrict the autonomy of these locally titled monks, Bangkok established a higher authority intended to outrank the local one, as this report by the sangha inspector of monthon Isan [มณฑลอีสาน] makes plain: In this monthon there is a local tradition called samoson sommut [authority based on popular consent]. Laypeople as well as monks in each village vote and confer their own titles of Phra Khru [พระครู] and Sangharat [สังฆราช]. In order to reflect his greater importance, the sangha head appointed by the king should bear a higher honorific title. We should title each Phra Khru according to the name of the district where he has authority. This way there should be no question of who has the higher authority, the locally appointed or the Bangkok-appointed monk. The Phra Khru title without the district name attached will have no meaning here, for there are already many Phra Khrus appointed by local people all over the northeast region. "

[Quelle: Kamala Tiyavanich [กมลา ติยะวนิช] <1948 - >: Forest recollections : wandering monks in twentieth-century Thailand. -- Honolulu : Univ. of Hawai’i Pr., 1997. -- ISBN 0824817818. -- S. 41. -- Faire use]

"...in several monasteries laypeople were not able to feed the mo because of poor crop yields. For example, in monthon Phuket, less th half of the forty-eight monasteries inspected were supported by the laity. From the education-director’s report, monthon Phuket. Ratchakijjanubeksa [Royal Thai government gazette] 18 (5 December 1900)" [Quelle: Kamala Tiyavanich [กมลา ติยะวนิช] <1948 - >: Forest recollections : wandering monks in twentieth-century Thailand. -- Honolulu : Univ. of Hawai’i Pr., 1997. -- ISBN 0824817818. -- S. 308, Anm. 10. -- Faire use]

1898

Öffentliche Schulen an Dhammayutika-Klöstern (ธรรมยุติกนิกาย):

- Bangkok: 4 Schulen mit 450 Schülern

- Provinzen: 3 Schulen mit 150 Schülern

1898

Thammayut-Mönche (ธรรมยุติกนิกาย) erhalten die Erlaubnis, die Normal School (Lehrerbildungsanstalt) zu besuchen. Dort erhalten sie eine schulpädagogische Ausbidung und einige werden als Englischlehrer ausgebildet.

1898

Gründung eines Thammayut Wat [ธรรมยุติกนิกาย] in Muang Kamutsai-Buriram

Abb.: Lage von Muang Kamutsai-Buriram

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"Prior to this [1906], a Thammayut wat [ธรรมยุติกนิกาย] had been established in 1898 in meuang Kamutsai-Buriram (now called Naung Bua Lamphu District [Nong Bua Lamphu / หนองบัวลำภู] in Udon Thani Province). It was established after Saeng, a native of Kamutsai-Buriram, came to meuang Ubon with a group of local monks and converted to the Thammayut order at Wat Sithaung [วัดศรีอุบลรัตนาราม / วัดศรีทอง]. The monks studied with the preceptor, Abbot Maw, before returning to Kamutsai-Buriram. At first they had no wat to stay in, so they wandered around teaching meditation. The ruler of Kamutsai-Buriram was impressed with their conduct and invited them to reside at Wat Mahachai. Later they set up a branch wat in Kumphawapi (today a district in Udon Thani), and three other branches in Loei and Khon Kaen. None of these Thammayut monasteries that Saeng set up are located in towns. Their isolated locations protected them from outside influences, and as a result Saeng and his fellow monks remained independent of Thammayut administrators. Saeng appointed himself a preceptor, ordained monks at will, and did not report to the Thammayut authorities in Ubon Ratchathani. (This was all before the Sangha Administrative Act was enforced in Udon Thani in 1908. )" [Quelle: Kamala Tiyavanich [กมลา ติยะวนิช] <1948 - >: Forest recollections : wandering monks in twentieth-century Thailand. -- Honolulu : Univ. of Hawai’i Pr., 1997. -- ISBN 0824817818. -- S. 344, Anm. 4. -- Faire use]

1898

In Bangkok gibt es sieben englischsprachige Schulen:

- Kings College (ราชวิทยาลัย)

- Normal School (Lehrerbildungsanstalt)

- Sunanthalai Girls School (โรงเรียนสตรีสุนันทาลัย) (geschlossen 1902; 1904 wiedereröffnet mit japanischen Lehrerinnen)

- Anglo-Siamese School (1903 geschlossen)

- English School in Wat Mahannapharam (วัดมหรรณพารามวรวิหาร) (1900 geschlossen)

- Englisch-Abendschule in Wat Suthat (วัดสุทัศนเทพวราราม ราชวรมหาวิหาร) (1900 geschlossen)

- Suankulap ( โรงเรียนสวนกุหลาบวิทยาลัย)

1898

König Chulalongkorn über Schulbildung für seine vielen Töchter:

"I cannot bring myself to think about my daughters education. I have never endorsed it ... , because it reminds me of my own teacher [Anna Leonowens] who authored a book which many believe. So whenever the suggestion is made that a girls' school be founded, I am quite annoyed." [Übersetzung: Barmé, Scot: Woman, man, Bangkok : love, sex, and popular culture in Thailand. -- Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. -- 273 S. : Ill. ; 24 cm. -- ISBN 0-7425-0157-4. -- S. 22]

ca. 1898

Abb.: Prince Bhanurangsi Savangwongse, The Prince Banubandhu Vongsevoradej (มเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ เจ้าฟ้าภาณุรังษีสว่างวงศ์ กรมพระยาภาณุพันธุวงศ์วรเดช, 1859 – 1928) in traditioneller Kriegsrüstung, Chiang Mai (เชียงใหม่), ca. 1898

1898

Strafgesetz: auf Vergewaltigung außerhalb der Ehe sowie "unnatürlichen Sexualverkehr" (Sodomie u.ä.) steht eine Strafe von bis zu 10 Jahren Haft.

1898

Abb.: Haushalt von Zweitfrauen, 1898

Abb.: Haushalt von Zweitfrauen, 1898

1898

Feuer im Vietnamesen-Viertel Bangkoks. Dies ermöglicht den Bau der Phahurat Road (พาหุรัด). Rama V. benennt diese Straße nach seiner früh verstorbenen Tochter Bahurada Manimaya (สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ เจ้าฟ้าพาหุรัดมาณีมัย กรมพระเทพนารีรัตน์, 1878-12-29 – 27 August 1887-08-27). Das Gebiet wird zum Inder-Viertel Bangkoks, besonders für Sikhs.

Abb.: Lage der Phahurat Road (พาหุรัด)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1898 (?)

Bau des Suan Kulap Palasts (วังสวนกุหลาบ) für Prinz Asdang Dejavudh (พลเรือเอก สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ เจ้าฟ้า อัษฎางค์เดชาวุธ กรมหลวงนครราชสีมา, 1889 - 1924)

Abb.: Lage des Suan Kulap Palasts (วังสวนกุหลาบ)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1898

Gründung der Bangkok Chamber of Commerce. Chinesische Firmen haben keinen Zugang.

1898

Der Brite Charles James Rivett-Carnac (1853 – 1935), Accountant General von britisch Burma, wird Finanzberater Siams.

Rivett-Carnac ist nach dem Urteil des britischen Gesandten George Greville

"a first-rate man and official, but who openly avows his ambition and that he has come here to make a name for himself:" [Zitiert in: Petersson, Niels P.: Imperialismus und Modernisierung : Siam, China und die europäischen Mächte 1895 - 1914. -- München : Oldenbourg, 2000. -- 492 S. ; 25 cm. -- (Studien zur internationalen Geschichte ; Bd. 11). -- ISBN 3-486-56506-0. -- Zugl.: Hagen, Fernuniv., Diss., 1999. -- S. 106]

1898

Alexander Olarowsky (Александр Эпиктетович Оларовский, 1830 - 1907) ist Gesandter des russischen Kaiserreichs in Siam. Er erhält vom Zaren den Auftrag, Siam beim Erhalt seiner Unabhängigkeit zu unterstützen. Olarowsky genießt am siamesischen Königshof besondere Privilegien.

1898

Abb.: Landwirtschaftssteuer-Beleg, 1898

1898

König Chulalongkorn stiftet in Chiang Mai (เชียงใหม่) Land für den Friedhof für Ausländer (สุสานต่างประเทศ).

Abb.: Lage des Foreign Cemetery (สุสานต่างประเทศ), Chiang Mai (เชียงใหม่)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Einbandtitel von: Wood, Richard Willoughby <1916 - 2002>: De mortuis : the story of the Chiang Mai foreign cemetery. -- 2. ed. -- Chiang Mai ; Hudson, 1986. -- 40 S.

1898

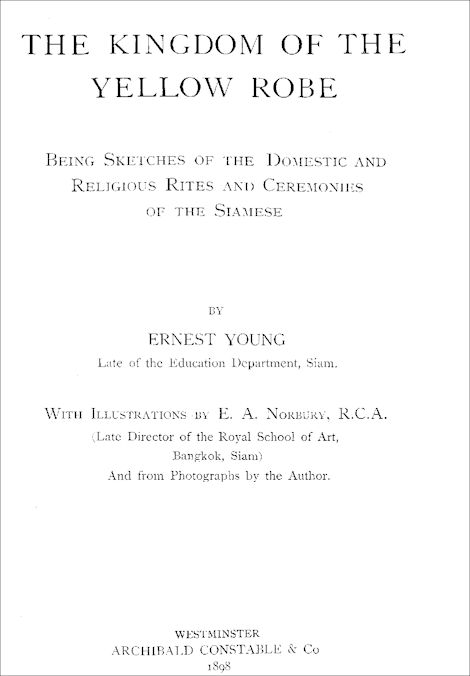

Es erscheint:

Smyth, H. (Herbert) Warington <1867 - 1943>: Five years in Siam : from 1891 to 1896. -- London : Murray, 1898. -- 2 Bde. ; 330 + 337 S. : Ill.

Abb.: Einbandtitel

"Herbert Warington Smyth (4 June 1867 – 19 December 1943) CMG, LLM, FGS, FRGS, was a British traveller, writer, naval officer and mining engineer who served the government of Siam and held several important posts in the Union of South Africa. Early life

Known as Warington, he was the elder son of Sir Warington Wilkinson Smyth FRS, Professor of Mining at the Royal School of Mines, and his wife Anna Maria Antonia Story Maskelyne. His younger brother Sir Nevill Maskelyne Smyth won the Victoria Cross at the Battle of Omdurman. He was educated at Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge.[1]

CareerAfter being an unpaid assistant to the Mineral Adviser to the Office of Woods from 1890 to 1891, he went to Siam. There he was Secretary of the Government Department of Mines from 1891 to 1895 and Director General from 1895 to 1897.[2] He became a Commander of the Order of the White Elephant of Siam and received the Murchison Award of the R.G.S. for journeys in Siam in 1898. In 1898, he was secretary of the Siamese legation from 1898 to 1901.

Warington Smyth was called to the bar in 1899 and in 1900 was delegate for Siam to the Congres International, Paris Exhibition. In 1900, he was Hon Secretary for London of the National Committee for the organization of a Volunteer Naval reserve. In 1901 he went to South Africa where he was Secretary for Mines in the Transvaal from 1901 to 1910. He was also Member of Legislative and Executive Councils, Transvaal in 1906 and 1907 and a JP and Advocate of the Supreme Court of the Transvaal. He was also President of the Transvaal Cornish Association from 1907 to 1910, in which year he was awarded the Queen's South Africa medal. From 1910, he was Secretary for Mines and Industries in South Africa and Commissioner of Mines for Natal as well as Chief Inspector of Factories.

He took an active part in World War I as an Acting Sub Lieutenant RNR in 1914, serving as Assistant Naval Transport Officer in the South-West Africa Campaign 1914 to 1915, when he was mentioned in dispatches. He became Lieutenant RNVR and Acting Naval Senior Officer at the Cape from 1915 to 1916, and Controller of Imports and Exports for the Union of South Africa in 1917. In 1919 he was awarded the C.M.G.. Following the war, he was South African government delegate to the International Labour Conferences at Washington in 1919 and Geneva in 1922.

He retired in 1927 and returned to England, living at Falmouth, Cornwall where he enjoyed yachting. In World War II, he was still active in the RNVR, serving in 1940 as Lieutenant Commander. He died in 1943 at Redruth.

FamilyIn 1900 he married Amabel Mary (1879-1965), third daughter of Sir Henry John Sutton KC and his wife Caroline Elizabeth Nanson. They had one daughter Amabel and three sons, Bevil, Nigel and Rodney. His wife's sister Marjorie was married to Julius Bertram

Publications

- Journey on the Upper Me Kong 1895

- Five years in Siam: from 1891-1896 (1898). Reprint 1994 Bangkok : White Lotus. ISBN 974-8495-98-1. (Chapter 1)

- Mast and Sail in Europe and Asia 1st edition 1906, 2nd edition 1929

- Sea-Wake and Jungle trail 1925

- Chase and Chance in Indo-China 1934"

[Quelle: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Warington_Smyth. -- Zugriff am 2017-01-14]

Abb.: Titelblatt von Bd. 1

Abb.: General index map

[a.a.O., Bd. 1]

Abb.: The Menam plain with the Western frontier <Ausschnitt>

[a.a.O., Bd. 1]

Abb.: Part of the Lao states <Ausschnitt>

[a.a.O., Bd. 1]

Abb.: The Malay Peninsula

[a.a.O., Bd. 2]

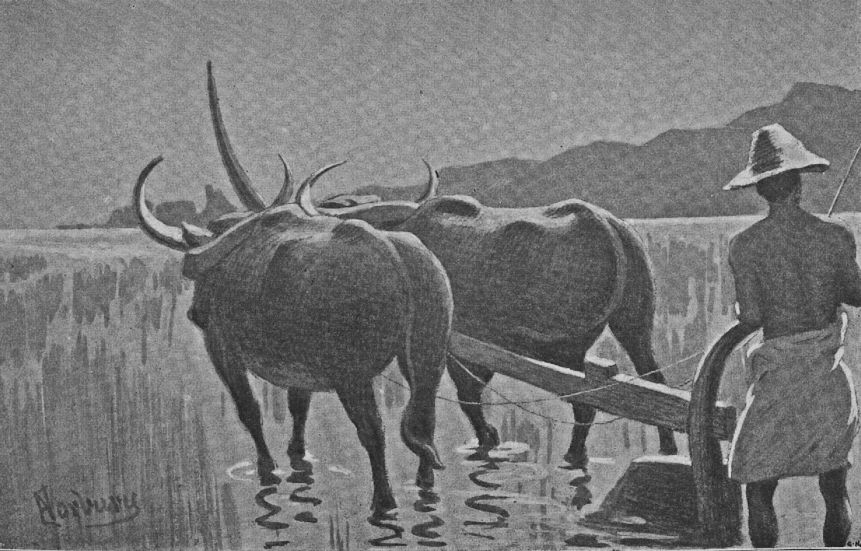

Abb.: Rice boat -- awaiting cargo

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 93]

Abb.: Outline of the upper waters of the Me Kawng [Mekong] and its brethren

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, nach S. 138]

Abb.: A highland Kaw [อีก้อ / Akha]

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, nach S. 172]

Abb.: Joint of clapper, cattle bell, the "Big Ben" of Nong Khai [หนองคาย]

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 254]

Abb.: Da and jungle knives

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 1]

Abb.: Sonkhla [สงขลา] fishing stakes

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 101]

Abb.: The gem districts of Chantabun [Chantaburi / จันทบุรี]

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, nach S. 102]

Abb.: 'Kek' or Lakawn [= Nakhon Si Thammarat - นครศรีธรรมราช] reaping hook

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 29]

Abb.: Wheel, Lakawn [= Nakhon Si Thammarat - นครศรีธรรมราช] tin cart

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 133]

Abb.: A fellow traveller off Chantabun [Chantaburi / จันทบุรี]

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, nach S. 164]

Abb.: Annamite settlement, Chantabun [Chantaburi / จันทบุรี]

[a.a.O., S. 173]

Abb.: In the rainy season

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, nach S. 218]

"In the old days the outlying provinces were ruled by vassal chiefs, who, as long as they paid certain tribute to the King de facto, might rule or misrule, as they wished. Their sons succeeded so long as they were agreeable to the over-lord. In fact, the governing was done by contract: ‘ If you look after the province and pay me, I keep your family in power’—-until the stronger rival came along. Throughout Indo-Chinese history no such official ever received a salary; it was the recognised right of the Governor to make what he could, and for his subordinates to do the same, each according to his position and ingenuity. The Governor might, and generally did, monopolise all the trade he could, using his official power to crush all rivals. In this the old kings set the example. The subordinates followed the great man’s example, and in a similar position the people would have done the same. For it was tamniem [ธรรมเนียม]. In moderation no one questioned the method, for it was the only one open to an official by which to make his living. Thus, under the majority of governors, bent on securing a competence for their large families, any man who had made a little money was liable to be brought to court on some fancy charge, and have his goods confiscated, while the highest bidder always got the verdict of the judge."

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 21f.]

"Of the Army and Navy, the latter was by far the smartest organisation. It is most regrettable that, owing partly, no doubt, to the inherent laziness of the nation, but also largely to the way in which the conscription is conducted, as well as to the wretched pay and to the manner in which the services are generally carried on, the Tahan [ทหาร] is universally looked down upon. The girls will not speak to him, and the common people avoid him ; he feels he is an outcast, with the inevitable result that when he gets the chance he behaves as such, and generally goes to the bad. The whole military instinct of the people seems to have been killed, and men and families will face anything rather than the prospect of serving, either for themselves or their relatives. No effort seems to have been made to create an esprit de corps. The men are tacitly permitted to assume the character of trained bands of coolies, to do whitewashing, or to figure in processions—a treatment which they very properly resent."

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 27f.]

"Since 1893 the extension of French rule to the left bank of the Me Kawng [Mekong] has introduced yet another complication, the effect of which is detrimental to the foresters. The Kamus [ຂະມຸ / ขมุ], who have formed for years the bulk of the forest labour, came from the left bank of the Me Kawng. The French authorities are now doing all they can to put a stop to emigration from that already thinly populated district. The consequence is that the supply of Kamu labour is falling off, and the forester must engage the less industrious and less reliable Karens, Shans, or Laos, who require a wage forty per cent, higher than that formerly paid to the thrifty Kamus." [a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 107]

"The position adopted by the Imperial and Indian Governments with regard to the connection of Burma with the valley of the Yellow River was very clearly given by Lord Salisbury [Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, 1830 – 1903], in June 1896, in reply to a deputation of the Associated Chambers of Commerce who asked the support of the Government in opening up trade routes, either from Maulmen [Moulmein / မော်လမြိုင်မြို့], via Siam, or from Rangun [ရန်ကုန်] through British territory, via Karenni, by building or guaranteeing a railway, and obtaining the permission of the Chinese Government to continue it from the frontier into their territory, via Sumao [Simao / 思茅]. Lord Salisbury pointed out that it was impossible to expect the Government to give money for a railway in other people’s territory; and that a railway through an independent country such as Siam would be under foreign control, and to all intents a foreign railway. As far, however, as our own territories were concerned, if capitalists found the money, they might be sure of the assistance of the Government, and he had little doubt that once on the Chinese frontier the Chinese would find it to their own obvious interest and to the advantage of their customs to facilitate our entrance into Yunan [雲南]. "

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 143]

Abb.: Lage von Nong Khai [หนองคาย], Korat [โคราช] und Luang Prabang [ຫຼວງພະບາງ]

[Bildquelle: CIA. -- Public domain]"Nawng Kai [Nong Khai / หนองคาย] is a scattered township with a population of some 5,000 people, and is the most important place between Korat [โคราช] and Luang Prabang [ຫຼວງພະບາງ]. It owes its existence to the downfall of Wieng Chan [Vientiane / ວຽງຈັນ] in 1828, since which it has been the chief Siamese administrative post of that portion of the Me Kawng [Mekong], and has more recently become the chief distributing centre of the northern end of the plateau, resorted to by the Chinese traders from Korat. A hundred boats or so per annum used to pass between Luang Prabang and Nawng Kai, so that a portion of the trade of the former place found its way south by this route; but few of the cargoes exceeded 20 cwt., and this trade has been reduced of recent years.

The Commissioner, Prince Prachak [กรมหลวงประจักษ์ศิลปาคม, 1856 - 1924], was a brother of the King, and a man of considerable energy; he dabbled in chemistry, and was a devotee of Reform with a big R. "

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 222]

[Über das Korat Plateau:] "Communications are, on the whole, worse than in any other part of the country. Distances without water in the hot season almost impossible to man and beast, bogs and unbridged torrents in the rains, no salas [ศาลา], or rest-houses, along the trails, dacoity not yet put down, and the least possible official recognition of the importance of encouraging trade: such are some of the causes of the lethargy of the people—attributable, first of all, as I think, to the nature of the country, and secondly to the incompetence and lack of interest of the official class.

Korat [โคราช], the trade centre of the whole plateau, has only 5,000 inhabitants; Ubon [อุบลราชธานี], the other great town of this portion of the country, 4,000. As Dr. Morrison truly observes, ‘ more people live in a city in China than in a whole province of Eastern Siam.’ The places called Muang [เมือง], or ‘town,’ do not exceed a couple of hundred houses as a rule. Disease—fever, smallpox, dysentery, and lately cholera—seems, so far, to have kept down the population, which one would have expected to show signs of increase since the cessation of the old perpetual warfare."

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S, 233f.]

"We were able to go all the way to the King’s summer residence at Bangpain [Bang Pa-in / บางปะอิน] along the line. Trains could run part of the way, but, owing to the sinking of the abutments of some of the bridges, trollies had to be used for the rest. The unprofessional observer could not but be struck by the small amount of bed-ballast on the line, and six inches seemed certainly very little for a country of such heavy rainfall, and, in fact, every heavy rain has necessitated such extensive renewal of ballast that in all eighteen inches has been laid down in many places. With so little ballast as six inches and only fifty-pound rails, no fast running will be possible. The engines, however, are a cheap design, not likely to run fast, being hardly up to their work under ordinary circumstances. They are of two types—two-couple twelve-inch, and three- couple fourteen-inch cylinders for the hill sections. The most expensive part of the rolling stock is the royal saloon carriage and the ‘ officials’ ’ carriage.

The line has been delayed by a good deal of very unfortunate friction between the Royal Railway Department, represented by Herr Betche [Karl Bethge, 1847 - 1900], the Director-General, and Mr. Murray Campbell [George Murray Campbell, 1845 - 1942], the engineer who contracted to build the line. The failure of the bridges entailed enormous additional expense and delay, in transport by river to the higher sections of the line, and prevented the contractor from being able to push all his stores up by the line as it proceeded. The question whether the failure of the piers was due to faulty designing by the Railway Department or to bad construction by the contractor, together with other innumerable questions connected with this, have lately been referred to arbitration.

The extremely spongy nature of the top soil, the great depth to which it reaches, and the numbers of culverts and small bridges necessary to carry off the large quantities of water during the rains have added greatly to the difficulties of construction across the Me Nam plain. As far as Ayuthia the line runs parallel to the river, and though new villages may later on spring up in its neighbourhood, for some time to come the river is likely to monopolise the goods traffic, and to remain the centre of the population, as being a cheap highway open to all, and one to which the Siamese are accustomed by use and tradition.

From Ayuthia [อยุธยา] (42 miles) it turns eastward to Pakprio [ปากเพรียว] (Saraburi [สระบุรี]), on the Nam Sak [แม่น้ำป่าสัก], which is the starting-place for all the caravans for Korat [โคราช], goods coming thus far by water. At Keng Koi [แก่งคอย] (73 miles) the line leaves the river, and can be said to be no longer in competition with water traffic. It begins to ascend the poisonous terai through dense low scrub towards the first rock-cutting at Tap Kwang [ทับกวาง], and from here to Hinlap [หินลับ] it is winding its way into the forested hills of the dreaded Dawng Praya Yen [ดงพญาเย็น]. The work above Keng Koi has been attended by such mortality that it has often been almost impossible to procure coolies, and the contractor’s staff, owing to deaths and sickness, has been permanently short-handed."

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 243f.]

"The most striking innovation in Korat [โคราช] was the French Consulate.

There were no French subjects, and there was no French trade ; but a very charming consulate was being built at a cost of thirty thousand francs to replace the present building occupied by the consul and his interpreter, where we were most hospitably entertained.

Two tricolours floated in the compound, and M. Rochet informed us the flag would soon float over the whole of the country round. We learned further from him that Korat was a Cambodian city of great magnificence until ruined by the rapacious Siamese of late years. Encouraged, doubtless, by our innocent appearance, he also informed us that Cambodian was the language of the country people round Korat, and of the plateau generally, and that Siamese was not understood except in a few villages, being spoken only by the Governor and his followers.

It was difficult to understand what our host took us for. The doctor’s bland expression and keen interest doubtless encouraged our informant; but when he asked innocently how it was the consular interpreter spoke only Siamese, the flow of our host’s original and entertaining information ceased entirely.

The consul’s life must be a singularly lonely one, for he has not the distraction of work to occupy his mind. About a hundred registration papers had been sold to Chinamen at eighteen ticals apiece. None of these persons were French citizens, and hardly any had ever been in a French colony or protectorate, or their parents before them. The sale of papers did not reach this figure without considerable advertisement, and the consul has bravely faced the sun and heat in the market-place many weary hours, searching for Chinese to shake hands with and invite round to see him. He seemed so anxious to sell that, I am sure, the doctor’s kind heart was touched, and if they had been a little cheaper perhaps we might have indulged in one between us. The French consulate merits support, as any trade development which may haply result from it will be to the advantage of British importers almost exclusively. No other route from Korat can ever compete with the Saraburi [สระบุรี] route to Bangkok, even disregarding the advance of the railway; and all increase of trade therefore means increase of British trade, unless artificial obstructions such as tariffs are erected against it.

The attitude of mind of the French consul towards everything Siamese was instructive. To him, as to many of the less educated officials of the French Colonial empire, Siamese is synonymous with all that is most wicked and abominable in the universe. It is impossible for some of those afflicted with this mania to speak with moderation on things Siamese, or to deal with them according to the canons which generally rule in political or business intercourse."

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 249f.]

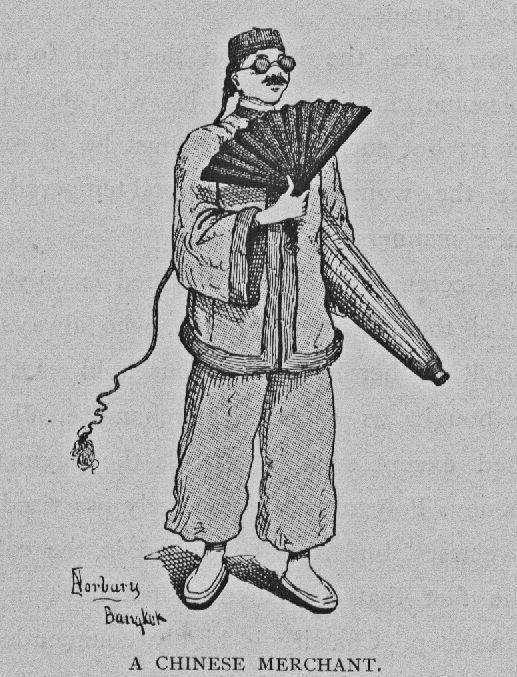

"The Chinese in Siam have always been exempt from corvée, and have only had to pay a triennial poll tax of about six shillings. Considering the money they make out of the country, and the freedom of action they enjoy when compared with the native Siamese, it is no wonder that the children of mixed marriages adopt the pigtail when they can. They are the Jews of Siam; and though they have bean subject to a little fleecing by local authorities, they have on the whole enjoyed an immunity from official interference which they have neither merited nor appreciated. Their only return has been that species of high-handed rowdyism which results from the methods followed by Chinese secret societies elsewhere. Cowardly attacks by large numbers upon solitary individuals, an occasional corpse in the river, or a headless trunk upon the track, mark the spread of their activity. The societies are nearly as powerful in Siam as the King himself. By judicious use of their business faculties and their powers of combination, they hold the Siamese in the palm of their hand. The toleration accorded to them by the Government is put down to fear; they bow and scrape before the authorities, but laugh behind their backs; and they could sack half Bangkok in a day. The societies need total suppression, as in the Straits, and the Chinese should be taxed and governed proportionately to the Mons and other Asiatic races who have taken up their abode in the country." [a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 285f.]

"The death-rate among the coolies [in den Minen von Prachadi], who are generally Hainanese [海南人] imported direct, is large in all the mining districts, which, being as a rule in the hill ranges, are the worst for fever and dysentery. The death-rate from these causes among new arrivals has, in many cases, exceeded 60 per cent. Panic accounts for many more, and as new drafts go up country the effect produced by the stories they hear is such that bolts and bars cannot keep them. As advances have to be made to all these men, it is a serious matter to lose 70 per cent, by desertion before arriving at the mines, and 60 per cent, of the remainder in the next rainy season. The local authorities, when requested to assist in finding and arresting the deserters, reply, ‘ If you bring the escaped men up before us, and charge them with breaking their contract, we will assist you by putting them in goal.’ During a scare at Prachadi the rate of desertion was eight men a day, and the manager of Watana [วัฒนา] on one occasion despatched a party of 120 men from Bangkok, of whom, notwithstanding close supervision, only forty arrived at the mines five days later. It is quite impossible to get Chinese who have been any time in the country to go to a mine, even by promises or advances of a most exorbitant kind. At Kabin [Kabinburi / กบินทร์บุรี] and Watana, in the neighbourhood of Prachim [Prachinburi / ปราจีนบุรี

], Lao labour has been to some extent utilised; but so insufficient control has never been obtained over it. On the western side, however, it is impossible to get native labour in sufficient quantity, even temporarily, and imported labour, with all its drawbacks, has therefore to be relied on."[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 301]

[Über Phuket [ะภูเก็ต]:] "In the old Rajah’s time the roads were in good repair, and it was possible to take oxcarts up to the inland mines without trouble. During our visit, the only workmen upon the roads were eager miners, who were demolishing them for the tin that lay beneath, or patient drivers rebuilding breaches in them sufficiently to get their buffalo carts across. The indifference of the Government to the condition of the roads imposed a further burden on the miners, especially the more distant ones. The incompetence of the Government officials in regard to all mining questions resulted in the accumulation of unsettled claims and counter-claims, and in quarrels over water rights and boundaries, which still further hampered them, and were a source of danger to the public peace.

With one of the junior commissioners, whose functions had been practically usurped by the ‘ special ’ commissioner, I went to one mine where the tavike had been deprived of water by his neighbour, who had tapped his lead at a higher point, and demanded a fee of some thousand dollars for its renewal. Our friend, who had some fifty men upon the mine, had done no work for three months, and quite acquiesced in the position of affairs. The other tauhe had more men and more guns, so, after a preliminary fight, he had decided to wait patiently for the rains, when he hoped to get some water.

The impression left on my mind after finishing our work in Puket was that the ‘ special commissioner, ’ Praya Tip Kosa [พระยาทิพโกษา], must be imbued with a profound hatred of the Chinaman, and must be very anxious to see the last of him. Beyond the very high qualities of which he is undoubtedly possessed—qualities shared perhaps equally by the buffalo—I confess I have no great admiration for the Chinese coolie, and I felt perhaps a slight sympathy with the Commissioner on the object it was natural to attribute to him. I ventured, consequently, to congratulate him in my most genial manner on the very thorough and efficacious methods he had adopted to turn the Chinese out of the provinces under his charge. My remarks were received with singular coldness.

I was told in Bangkok that he was an extremely clever man, a fact which no one who knew him would think of disputing; and one could not presume to suppose he had adopted this policy of bleeding the western States without being fully alive to the obvious consequences. It is only surprising that the Siamese Government should acquiesce. He was recently reappointed for another term of office, and every mark of confidence was bestowed upon him. His success in revenue-remitting has been undoubtedly very great; he has made it a fine art, and is said to maintain an average return to Bangkok of $-300, 000 annually. No Governor could have done more in this respect, and certainly no governor in the world could have spent less on the provinces under his charge.

Besides the Government offices and the special commissioner’s own residence, we noted three other instances of public works which need to be recorded to show that some money is spent in Puket. A piece of road near Naitu [= Kathu / กะทู้] was repaired before we left, for a distance of some two hundred yards. It may have cost a hundred dollars. Secondly, when the police barrack fell down, a brand-new bamboo shed was erected, I believe not at the expense of the policemen. Thirdly, the tide gauge, marks, and buoys in Puket harbour all showed undoubted signs of paint, The paint, it was true, was paid for by Captain Weber, a local resident in charge of the police, but it was put on by men in Government service."

[a.a.O., Bd. 1, S. 320f.]

Abb.: Lage von Trang [ตรัง]

[a.a.O., Bd. 2]"Trang [ตรัง] is the Tarangue of the Portuguese. The present Rajah, Praya Rasada [พระยารัษฎานุประดิษฐ์มหิศรภักดี (คอซิมบี๊ ณ ระนอง / 許心美), 1857 - 1913], is a Chinaman, known familiarly as Simbi. His two brothers are the Rajahs of Renawng [Ranong / ระนอง] and Langsuan [หลังสวน], but neither can equal him in energy, popularity, or good nature. He has travelled in Burma, visited Java, and is at home in the Straits. Of his own initiative he introduced the Burma village system into his province. In 1892 he moved his capital bodily down river to be near the sea. At the time of our visit, ten miles of road had been completed, six large wells had been sunk, and bricked and covered in ; a gaol, a court-house, and a landing pier had been built, and hundreds of acres of padi land had been cleared and drained round the new town. The old capital, Kontani [Khuan Thani / ควนธานี] (Captain Low’s Khoantani), was being connected with the new one, Kantan [Kantang / กันตัง], and also with the great pepper district of Taptieng [Thap Thiang / ทับเที่ยง], by the opening of new roads, and the repair of old ones. All the work was thorough. Dacoity had practically disappeared. Even the secret societies, which generally work their own sweet will in Siam, had received a warning in the total suppression of one of their number to which a murder had been traced."

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 8]

"For filth and mismanagement this place ran Puket [ภูเก็ต] very fine. Once, subsequently, when discussing the condition of the various western provinces with his Majesty, he observed,

‘ I noticed at Takuapa [ตะกั่วป่า] that they had taken much more care to hide things from me than in any other place I visited. They always try to hide a great deal from me,’ he added, smiling, ‘ but there was very much to be hidden there.’

All the usual symptoms of inefficient government existed ; unsatisfied litigants, unsettled claims, and untried prisoners. The police, who numbered twenty-four all told, were underpaid and overworked. They were ill- clad, disgracefully housed, and worse armed. Scattered in twos and threes about the province, they were so outnumbered by the coolie class, of whom there were probably eight thousand, that, incapable of mutual support, they were practically useless for purposes of keeping order. Mining affairs were in inextricable confusion, and we heard endless complaints. The acting Governor and his officials were evidently incapable of dealing with the intricate and technical character of a large proportion of the questions brought before them. While litigants complained to us of the delays and the unfair decisions they were expected to submit to, the officials themselves confessed to us their own incompetence, and begged us for advice, in the winning way customary in the East when there is no intention whatever of following one’s counsel, but merely a wish to disarm and be rid of one as rapidly and peacefully as possible."

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 19f.]

"At Renawng [Ranong / ระนอง] we were cordially welcomed by the Rajah, Praya Setthi [พระยาเศรษฐี], and his secretary, Dr. Gunn. The hospitality of Renawng has long been proverbial with British officials in the Tenasserim provinces [ဏၚ်ကသဳ]. More recently the price of tin has fallen, and the special commissioner at Puket [ภูเก็ต] has commenced to have his say in the place, with the result that the Rajah has been compelled to retrench; the roads show signs of disrepair, a large coolie emigration is now yearly taking place, and there are other signs that Renawng’s best days are over.

The Rajah was long the most enlightened ruler in the peninsula. From a, tiny fishing village he made the place into an important mining centre. Landing-stages, smelting- houses, first-class roads, and charming bungalows sprang into being in the pretty semicircle of hills to the north-east of the river mouth. A regular system of mining regulations was established, an efficient police force was created, and justice was meted out to all. The natural result was that when the King visited Renawng during his peninsular tour he found it in the most flourishing condition. From that time the central Government began to interfere with the Rajah, and the chief commissioner was given the power to meddle in his own way, with what results might be anticipated. The Rajah’s experience and capacity have fortunately been recently recognised by his appointment to the commissionership of Champawn [Chumphon / ชุมพร]. I saw a good deal of the old gentleman subsequently, when he was summoned to Bangkok to assist the committee appointed by the Legislative Council to consider the draft of the Mining Regulation submitted by our department. He was the only member of the committee who made any pretension to punctuality. His quiet deferential manner always marked him as an unusual man, and he never spoke except when specially asked for his opinion. It was invariably worth the asking for, in striking contrast to the many opinions which were volunteered.

The Siamese and Malay population of Renawng consists of only about 7,000 persons. There is very little rice grown in the province, and the villages are poor, scattered, and generally lie along the banks of the stream, or among the wide creeks and inlets which run into the country behind the outer coast-line. The people are of the usual type of the peninsula people we had everywhere met, and had the same nasal twang. The girls wore the old-fashioned long locks of hair over their ears, the rest of the hair being cut short and standing upright in the usual way. The men seemed to prefer the Malay sarong [صارون] to the Siamese panung [ผ้านุ่ง], and had generally the restrained manners of the former. It was curious, as showing how largely the prosperity of Renawng had had to do with Chinamen, that Dr. Gunn, the Rajah’s right-hand man, scarcely spoke a word of Siamese."

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 27f.]

[Über die Inseln vor Chumphon (ชุมพร):]

Abb.: Lage von Chumphon (ชุมพร)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]"In these islands the edible birds’ nests, loved of Chinamen, are collected. The Governor of Chaiya [ไชยา], who up to the end of 1896 farmed them of the Government at a rent of four hundred and twenty katis, or 2, 240 l. a year, has them protected against poaching by armed guards, and a fleet of more than twenty rua pets is kept up for their relief and supply. They act as cruisers and guard boats at a cost of a hundred and ninety katis [斤], or 1, 000 l. [= £] a year. The range over which these nests are found is extensive. From the Gulf of Tongkin to the Andamans, in the Gulf of Siam, among the Mergui Islands, and in the Malay Archipelago, wherever the steep-sided limestone islands stand up from the water’s edge, there the little swift known as Peale’s swiftlet (Collocalia spodiopygia [= Aerodramus spodiopygius (Peale, 1848)]) builds his shallow cup-like nest against the rock and in the caves. The silvery appearance of the nest, and the absence of all but the finest threads and attachments, make it look like a beautiful white gelatine.

Converted into soup, it is like a tasteless vermicelli, although pronounced by Chinamen and Siamese as extraordinarily nutritious and strengthening for invalids. Collocalia Linchi [(Horsfield & Moore, 1854)](Horsfield’s swiftlet) and C. esculenta [(L. 1758)], as well as Hirundinapus Indicus [Hirundapus giganteus indicus ?], are credited with being the clever architects of some of the edible nests, but I believe that although their nests are of much the same shape, and occur in similar localities, they are less sought for by the nest collectors, being considered to have a larger amount of vegetable matter mixed into them. The difference in colour of the nests, which gives rise to the distinctions in the market quality, is often caused by the fact that they are built by different varieties.

The nests are gathered by the Siamese three times a year, in January-February, in April-May, and in August. Care has to be taken to begin just when they are finished and before the eggs are laid; after an egg is once laid, if the nest be taken, the Siamese declare the birds will not build again. The question of the material with which they build, although long a puzzle to the Westerner, has never troubled the mind of the Siamese, for he knows full well that at each flight the bird goes up to heaven to obtain it.

The favourite positions for the nests are in the most inaccessible places, and especially in caves to which there are open-air shafts. The collector can often only reach them swinging in the bight of a rope, and he sweeps them down with the aid of a long bamboo.

As the nests are valuable, it is often a great temptation to passing mariners to stop under the lee of an island and do a profitable morning’s work. In three years Praya Chaiya’s guards have caught as many as two hundred poachers, and now the guards generally open fire on any boat approaching an island in their charge nearer than a hundred yards, with the result that now and then boats in distress get unexpected contributions of lead ballast.

It is an adventurous life, that of these island guards. Their cottages have a most romantic aspect, perched high upon the bare precipices, or nestling snugly on the little patch of shingle beneath a palm or two. The stories of wrecks and storms, of alarms and armed encounters, and of hardship and endurance connected with them, would form a strange chronicle, such as few callings could equal."

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 53ff.]

Abb.: Lage von Songkhla (สงขลา)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]"Singora, or Sungkla [Songkhla / สงขลา], as Siamese know it, was seized at the beginning of the century by Chinese from Amoy [廈門], led by the great-grandfather of the present governor, and for a long time they were little meddled with from Bangkok, under which they had placed themselves.

The present Commissioner at Sungkla is Pra Vichit [พระวิชิต], who will be remembered as having been at the Siamese Legation in London three or four years ago. He has the provinces of Lakawn [= Nakhon Si Thammarat / นครศรีธรรมราช] and Patalung [พัทลุง] as well under his jurisdiction. His energy and earnest desire to improve matters have wrought such changes in Sungkla that he has already won the heartfelt gratitude of the people.

The governor himself, one of the most open-minded in the country, is a man of ideas, with considerable mechanical skill, and he has taken up eagerly Pra Vichit’s plans for roads, hospitals, courthouses, improvement of prisons, and so forth. It is very evident, however, that they, like the governor of Chaiya, are hampered by the lack of adequate assistance, a trouble which is felt by all men endeavouring to carry out good work in the country. It is impossible to get reliable and efficient men to aid in the work when there are no adequate salaries forthcoming. Obliged to fall back upon the services of inferiors, untrustworthy in every sense, the honest men have to keep as much work as possible in their own hands, with the result that they are soon overworked and ill, and matters fall into arrears. Among the methods of making money open to dishonest officials are: neglect in giving receipts for land tax, and collecting them again by threats of force, twice or even three times; refusing to give titles to people taking up new (forest) land to clear, without a bribe; tolls on boats; falsification in counterfoils of receipts given; incorrect measurements and entries of land, &c. &c. —malpractices that it is almost impossible for one person, with but two or three reliable assistants, to detect in the business of a large province. And wherever there are Chinamen there bribery is an epidemic, for the giving and taking of bribes is as necessary to the happiness of the Chinaman as are his pork and pigtail. The only remedy is for the Government to spend more money in the provinces, and to institute a sufficiently salaried Civil Service. In this way alone will such men as Pra Vichit, Praya Chaiya, Praya Setthi, and others of their type succeed, and such Augean stables as Lakawn be cleansed.

Again, the abolition of the corvée has very practical drawbacks in Sungkla, for the governor finds it almost impossible to get people to work, even at the fixed wage offered. He is powerless to enforce orders, for the people look upon abolition of corvée as abolition of his right to give orders, and the only people he has undoubted command over, and can use for work, are the gangs of convicts.

It has often happened that work has been sanctioned from Bangkok to be done perhaps in a hurry, and then the money is not found, and a governor is told to settle. If he is a fair man he is out of pocket—if an unfair man, he does not pay for the work. Thus he often chafes under a natural feeling of isolation and neglect.

Prince Damrong [ดำรงราชานุภาพ, 1862 -1943] has done his best to get the importance of the interior recognised in Bangkok, but until it is thoroughly understood by the Government that, as a preliminary, money has to be spent for a little, real reform will never come.

The inclination, as already pointed out, is to regard the provinces as the proper sources from which the money may be systematically bled to pay for the glorification of Bangkok.

Sungkla (the Sangore of Captain Hamilton) is by far the most important place along the coast, and its possibilities as a harbour and its central position are greatly in its favour, both from a commercial and administrative point of view. The population of the town and suburbs, including the very large Malay settlement on the west side of the harbour at Lem Son [แหลมสน], which stands as Flushing does to Falmouth, is 10, 000. The Malays retain their customs like those of Chaiya [ไชยา], but have lost their language and many other characteristics of the pukka [genuin] Malay. They are indolent and heavy, and an unsatisfactory people on the whole, without the positive virtues of the Malay or the Siamese. It is curious that in Lakawn, to the northward, the Malays have preserved a proper pride of race, and still speak their own tongue and are in every way superior to the Chaiya and Sungkla men, for whom they profess a well-merited disdain.

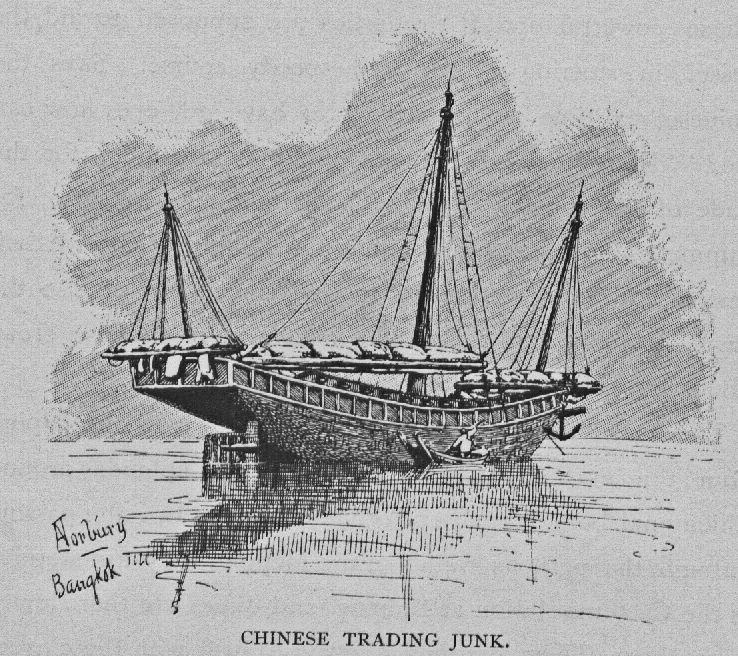

There are also a large number of Chinese traders who have practically got the monopoly of the local trade and own many junks. During the ‘ close ’ season of the year —the north-east monsoon—they buy up the produce from the poor growers, to whom they are in a position to dictate terms, and then despatch their junks, as opportunity offers, to Singapore, Bangkok, and all the smaller ports on the coast. They are, as may be supposed, very averse to Europeans coining into the country, and, as there seems absolutely no likelihood of the Keda-Singora railway being ever finished at the present rate of progress, there is every probability that the Chinaman will be paramount in the place for many years to come.

It is noteworthy that, notwithstanding the number and influence of the Chinese, there is not in Sungkla, as elsewhere, any Chinese coolie class."

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 93ff.]

"There are about a hundred elephants owned in the province [Nakhon Si Thammarat / นครศรีธรรมราช], and the best price ruling for a handsome tusker who is also a good carrier is about $500, or 56 l. [= £]; an average animal fetching $400, or 45 l. The former should carry 9½ cwt. [centum weight, 1 cwt. = ca. 51 kg.] with his mahout and saddle, the latter 8 cwt., which is very little more than the weight of food they eat per day. It is interesting to compare these figures with those in the Lao States, where elephants are even more extensively used. Prices at Nan [น่าน] and on the Mekawng [Mekong] varied (in 1893) from 24 l. to 32 l. a head, farther west the price for an average animal is as high again as 50l. and in Chieng Mai [เชียงใหม่] a really experienced teak-hauling elephant with good tusks may fetch Rs. 3, 000, about 150 l. In those mountain districts, where long and rough journeys are performed, the weight of load is only about one third of that which is usual in the tin States of the peninsula, seldom exceeding 300 lbs., or, at most, 3 cwt., which would be considered absurd in the peninsula. The heavy loads mentioned are only ventured on when the journeys are comparatively short, and the animals must be well fed and have good saddles. The elephants we saw in Sungkla were badly equipped in the last respect. The saddles were often carelessly made, and, though certainly light, were insufficiently supplied with the usual supply of skins and mats to save the back. In the way in which its two separate panniers dispose of the weight upon the ribs, this saddle is an excellent type for heavy loads, but from its low position it is atrocious to ride in. A small barrel- roof of bark was fitted on many.

I did not see any mahouts here armed with the usual spiked goad; they seemed to prefer a loaded cane, the heavy root forming the hitting end, the top having a twist for the handle, and with these they kept the animals well in order.

Our elephants here, accustomed to their heavy load, had not the quick gait of some of the Lao animals, but maintained fairly well the 2½ miles an hour which is the average speed of the elephant, and indeed of all caravan travelling in Siam, and which is rarely exceeded for a long trip, when fords, obstructions, and other things are taken into consideration, except by the independent pedestrian.

Here, as elsewhere in the peninsula, it is a mark of disrespect to be given a female elephant to ride.

In the old days, Burmans and Shans used to travel all the way down to Sungkla [Songkhla / สงขลา] and Lakawn [Nakhon Si Thammarat / นครศรีธรรมราช] to buy elephants, marching back with them up the peninsula, and taking a year or two over the expedition, but this traffic has nearly ceased, although now and then some are exported to Calcutta [কলকাতা] by way of Keda [قدح ]."

[a.a.O., Bd. 2, S. 107f.]

Abb.: Lage von Chanthaburi (จันทบุรี)