Kompiliert von Alois Payer

Zitierweise | cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Lehm als Material. -- (Architektur für die Tropen). -- Fassung vom 2009-11-10. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/tropenarchitektur/troparch02.htm

Erstmals veröffentlicht: 2009-06-16

Überarbeitungen: 2009-11-10 [Ergänzungen] ; 2009-10-14 [Verbesserungen] ; 2009-07-08 [Ergänzungen] ; 2009-07-06 [Ergänzungen] ; 2009-06-24 [Ergänzungen] ; 2009-06-24 [Ergänzungen] ; 2009-06-20 [Ergänzungen] ; 2009-06-18 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Creative Commons Licence (by, no commercial use) (für Zitate und Abbildungen gelten die dort jeweils genannten Bedingungen)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilungen Architektur und Entwicklungsländerstudien von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

น้ำชา gewidmet

| "It must be stressed that, contrary to

common belief, building with earth is not a simple

technology. The mere fact that natives of many countries have been

building their houses with earth since thousands of years does not

mean that the technology is sufficiently developed or known to

everyone. It is indeed the lack of expertise that brings about poor

constructions, which in turn gives the material its ill reputation.

However, with some guidance, virtually anyone can learn to build

satisfactorily with earth, and thus renew confidence in one of the

oldest and most versatile building materials." Quelle: Stulz, Roland ; Mukerji, Kiran: Appropriate building materials : a catalogue of potential solutions. -- rev., enlarged ed. -- St. Gallen : SKAT, 1993. -- 434 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- S. 9 |

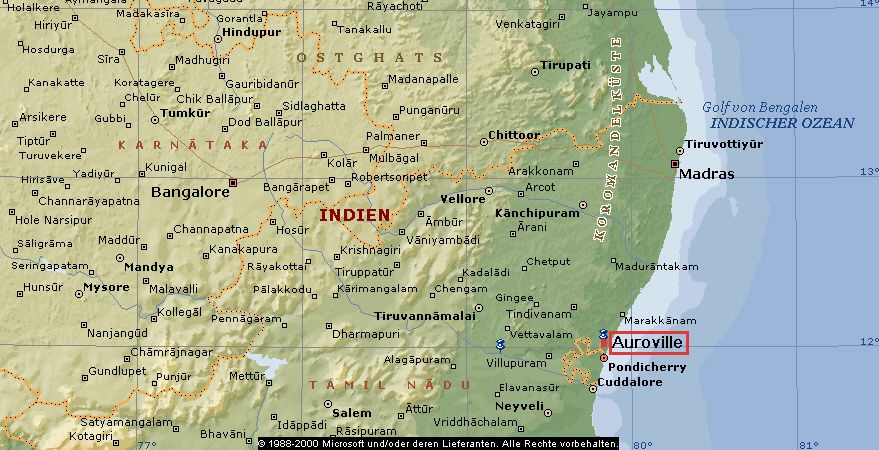

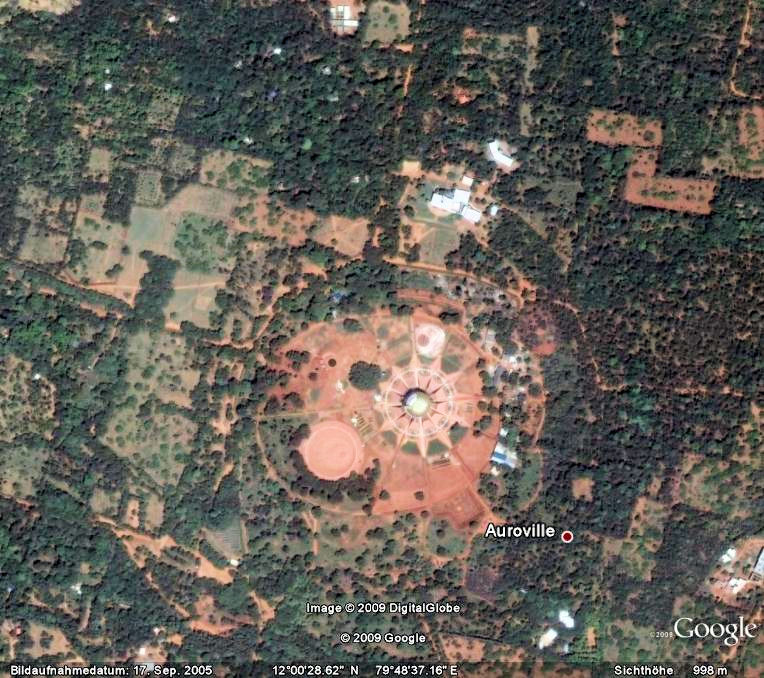

AEI = Auroville Earth Institute, Auroville, Tamil Nadu, India. -- http://www.earth-auroville.com/. -- Zugriff am 2009-06-11.

Copyright für AEI: "© Humanity as a whole, No rights reserved! All parts of the information contained in this website may be reproduced and disseminated worldwide. Please note that this information should be used with a lot of respect for Nature and it should aim sustainable development. Kindly acknowledge the source of information if you feel like disseminating it."

Minke (2009) = Minke, Gernot <1937 - >: Handbuch Lehmbau : Baustoffkunde, Techniken, Lehmarchitektur. -- 7., überarb., erw. und neu gestaltete Aufl. -- Staufen bei Freiburg, Br. : Ökobuch, 2009. -- 221 S. : Ill. ; 29 cm. -- ISBN 978-3-936896-41-1. -- Unentbehrlich!

"Lehm ist eine Mischung aus

- Sand (Korngröße > 63 µm),

- Schluff (Korngröße > 2 µm) und

- Ton (Korngröße < 2 µm).

Er entsteht entweder durch Verwitterung aus Fest- oder Lockergesteinen oder durch die unsortierte Ablagerung der genannten Bestandteile.

Lehm ist weit verbreitet und leicht verfügbar, er stellt einen der ältesten Baustoffe der Welt dar.

ZusammensetzungDie Mischungsverhältnisse von Sand, Schluff, und Ton können innerhalb definierter Grenzen schwanken, in kleinen Mengen kann noch gröberes Material (Kies und Steine) darin enthalten sein. Lehm mit nennenswertem Gehalt an Kalk, etwa in Folge wenig fortgeschrittener Verwitterung oder bei der Entstehung durch Ablagerung kalkigen Materials, wird als Mergel bezeichnet. Tonreiche Lehme werden als fett bezeichnet (nicht im Sinne von fetthaltig), tonarme als mager.

EigenschaftenLehm ist nicht so plastisch und wasserundurchlässig wie Ton, da die Korngröße der Bestandteile Sand und Schluff größer ist. In feuchtem Zustand ist Lehm formbar, in trockenem Zustand fest. Bei Wasserzugabe quillt Lehm, beim Trocknen schwindet oder schrumpft er, was im Lehmbau besonders zu beachten ist. Lehm als Baustoff speichert Wärme und wirkt regulierend auf die Luftfeuchtigkeit."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lehm . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-15]

Nach der Art der Lehmlagerstätten unterscheidet man:

Die einzelnen Bestandteile von Lehm:

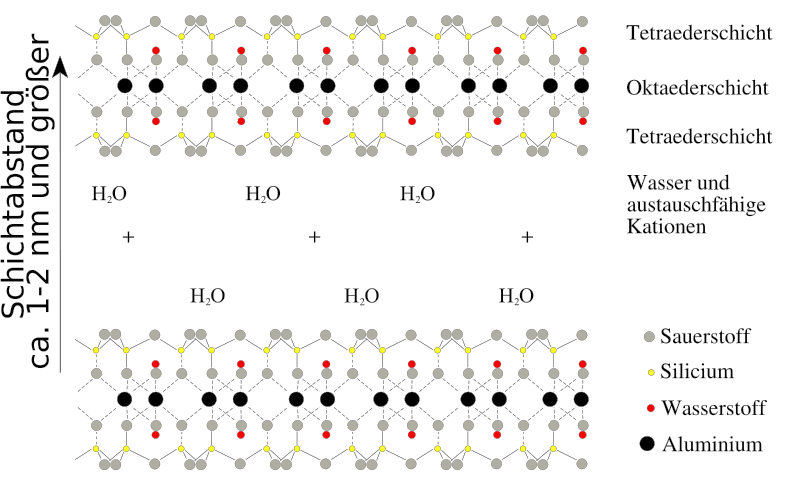

"Tonminerale bezeichnet einerseits Minerale, die überwiegend feinstkörnig (Korngröße < 2 µm) vorkommen, andererseits jedoch die Schichtsilikate, die nach ihrer schichtartigen Kristallstruktur aus Silizium und Sauerstoff, sowie Wasserstoff und meist Magnesium und Aluminium benannt sind. Beide Definitionen sind nicht deckungsgleich. Manche überwiegend feinstkörnig vorkommende Minerale, etwa Goethit oder Gibbsit, sind keine Silikate. Andererseits gibt es Schichtsilikate, wie z. B. Kaolinit, die oft größer als 2 µm sind. Tonminerale bezeichnen daher in der Regel solche Minerale, die beide Kriterien erfüllen. Entstehung

Tonminerale entstehen an der Erdoberfläche durch Verwitterung von anderen Mineralen oder Gläsern oder bilden sich neu aus übersättigten Bodenlösungen oder hydrothermalen Wässern. Bei der Diagenese kommt es zu Ordnungsprozessen im Kristallgitter der Tonminerale, die als Maß für die Reife eines Sediments verwendet werden kann.

StrukturTonminerale bestehen aus zwei charakteristischen Bauelementen:

- Tetraederschicht: eckenverknüpfte SiO4-Tetraeder, z. T. Substitution Si-Al

- Oktaederschicht: kantenverknüpfte AlO6-Oktaeder, z. T. Substitution Al-Mg

Je nach Anordnung dieser Schichten unterscheidet man:

- 1:1-Tonminerale (Zweischicht-Tonminerale): Tetraederschicht - Oktaederschicht: Bsp.: Kaolinit, Chrysotil

- 2:1-Tonminerale (Dreischicht-Tonminerale): Tetraederschicht - Oktaederschicht - Tetraederschicht Bsp: Illit

- 2:1:1-Tonminerale (Vierschicht-Tonminerale): Tetraederschicht-Oktaederschicht-Tetraederschicht-Oktaederschicht: Bsp. Chlorit

Durch die Substitution entsteht eine Schichtladung, die durch die Einlagerung von Kationen in der Zwischenschicht neutralisiert wird. Die Schichtladung der 1:1-Tonminerale ist stets Null. Die 2:1-Tonminerale werden nach ihrer Schichtladung klassifiziert:

- X = 0: Talk-Pyrophyllit-Gruppe

- 0,2 < X < 0,6: Smectit-Gruppe, z. B. Montmorillonit, Beidellit, Nontronit, Saponit, Hectorit

- 0,6 < X < 0,9: Vermiculit-Illit-Gruppe

- X = 1: Glimmer-Gruppe

Tonminerale mit nicht ganzzahligen Schichtladungen besitzen die Fähigkeit zur Quellung, d.h. zur temporären und reversiblen Wasseraufnahme in ihren Zwischenschichten.

Alternativ kann die Schichtladung in der Oktaederschicht auch dadurch kompensiert werden, dass nur zwei von drei Oktaedern besetzt sind. Daher unterscheidet man:

Eigenschaften

- dioktaedrische Tonminerale mit zwei besetzten Oktaederpositionen, z. B. Kaolinit

- trioktaedrische Tonminerale mit drei besetzten Oktaederpositionen, z. B. Chrysotil

Tonminerale sind sehr weich (Mohs-Härte 1) und reagieren plastisch auf mechanische Beanspruchung. Sie wandeln sich beim Erhitzen in härtere und festere Minerale um (Keramik). Tonminerale besitzen eine große spezifische Oberfläche, an die Stoffe adsorbiert und desorbiert werden können. Mit der großen Oberfläche ist eine hohe Kationenaustauschkapazität verbunden. Tonminerale haben eine geringe Wasserdurchlässigkeit. Suspensionen von Tonmineralen reagieren thixotrop auf mechanische Beanspruchung."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tonminerale . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-15]

Abb.: Schichtgitter von Montmorillonit als Beispiel für Schichtsilikate

[Bildquelle: Andreas Trepte / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Bindekraft und Plastizität (Formbarkeit) eines Lehms hängen von Art und Anteil der Tonminerale ab.

"Unter Schluff (auch englisch: Silt) versteht man in den Geowissenschaften unverfestigte klastische Sedimente (Feinböden) und Sedimentgesteine, die zu mindestens 95 % aus Komponenten mit einer Korngröße von 0,002 mm bis 0,063 mm bestehen. Dieses Korngrößenintervall nimmt damit eine Mittelstellung ein zwischen dem gröberen Sand und dem feineren Ton, und bildet einen wichtigen Anteil an den bindigen Böden, die umgangssprachlich als Lehm bezeichnet werden. Schluff bezeichnet anderseits aber auch den Siltanteil an einem Korngemisch aus verschiedenen Größen. Als Kurzbezeichnung für den Schluff dient ein großes „U“. Bestimmung im Gelände

Bei der provisorischen Untersuchung von Sedimentgesteinen während der geologischen und bodenkundlichen Gelände- und Feldarbeit ist eine Unterscheidung von Siltstein und Sandstein durch die sogenannte „Knirschprobe“ möglich. Hierbei wird ein kleines Stückchen des betreffenden Gesteins abgeknabbert. Ein charakteristisches Knirschen der Gesteinspartikel zwischen den Zähnen deutet auf Feinsand hin, der sonst mit bloßem Auge nur sehr schwer von Silt unterschieden werden kann. Bei Stadtböden und anthropogenen Substraten wird jedoch aus gesundheitlichen Gründen von der Knirschprobe abgeraten.

Die Abgrenzung von schluffigen zu tonigen Feinböden erfolgt im Gelände mittels „Fingerprobe“. Anders als Ton ist feuchter Schluff zwischen den Fingern nur mäßig formbar und es entstehen keine spiegelnden Gleitflächen auf den Fingerkuppen.

Die präzise Bestimmung der Korngrößen erfolgt jedoch im Labor durch Sieb- und Schlämmmethoden."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schluff . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-15]

"Sand ist ein natürlich vorkommendes, unverfestigtes Sedimentgestein, das sich aus einzelnen Sandkörnern mit einer Korngröße von 0,063 bis 2 mm zusammensetzt. Damit ordnet sich der Sand zwischen dem Feinkies (Korngröße 2 bis 6,3 mm) und dem Schluff (Korngröße 0,002 bis 0,063 mm) ein. Sand zählt zu den nicht bindigen Böden und stellt einen bedeutenden Rohstoff für das Bauwesen und die Glasindustrie dar. Entstehung

Sand entsteht durch die physikalische und chemische Verwitterung anderer Gesteine. Ursprüngliches Ausgangsmaterial sind magmatische und metamorphe Gesteine (z. B. Granit), aus denen typischerweise die Kristalle der mineralischen Bestandteile herausgelöst werden.

Durch die Schwerkraft, durch Wind und Wasser werden die Körner transportiert und dabei sowohl durchmischt als auch sortiert. Da die der Verwitterung und der Abnutzung beim Transport ausgesetzte Oberfläche stark vergrößert ist, können deren Kräfte jetzt besser ansetzen, so dass sich auch die Mineralzusammensetzung des Sandes und die Form der Körner vergleichsweise rasch ändern. So entstehen aus größeren Körnern kleinere, indem sie entlang der Kristallgrenzflächen gespalten oder durch Zusammenstöße der Körner untereinander kleinere Körner herausgebrochen werden. Einige Mineralien (vor allem mafische Minerale) werden unter Witterungseinfluss schnell chemisch umgewandelt und abgebaut, so dass ihr Anteil an der Gesamtmenge des Sandes deutlich abnimmt.

Durch mechanische Einflüsse beim Transport ändert sich die Form der Einzelkörner; generell werden Ecken und Kanten umso mehr gerundet und abgeschliffen, je länger der Transportweg ist. Dies ist allerdings kein linearer Prozess: Je runder und kleiner die Körner werden, umso widerstandsfähiger sind sie gegen weitere Veränderungen. Untersuchungen ergaben, dass häufig ein Transportweg von Tausenden von Kilometern nötig ist, um Sandkörner mittlerer Größe auch nur mäßig zu verrunden.

Beim Transport entlang von Flussläufen können diese Weglängen nur selten erreicht werden, und auch die stetigen Bewegungen in der Brandungszone eines Strandes reichen in den meisten Fällen nicht aus, um die Rundung von Sandkörnern zu erklären, besonders, wenn der Sand hauptsächlich aus widerstandsfähigem Quarz besteht. Der weitaus größte Teil des auf der Erde vorkommenden Sandes stammt daher aus Sandsteinen und hat somit schon mehrere Erosionszyklen hinter sich: Sand wird abgelagert (sedimentiert), überdeckt durch andere Sedimente, verfestigt sich, und die Körner werden durch Bindemittel miteinander verkittet (Diagenese). Wenn die Gesteine nach einer tektonischen Hebung wieder der Erosion ausgesetzt sind, werden die Einzelkörner freipräpariert und beim folgenden Transport wieder ein wenig weiter abgerundet, und es schließt sich ein weiterer Zyklus an. Selbst wenn man eine Zyklusdauer von 200 Millionen Jahren annimmt, so kann ein heutiges, gut gerundetes Quarz-Sandkorn durchaus zehn Erosionszyklen und damit fast die halbe Erdgeschichte durchlaufen haben.

Als Sonderfall ist Sand zu sehen, der aus den Überresten abgestorbener Lebewesen gebildet wurde, z. B. Muscheln oder Korallen. In geologischen Zeiträumen betrachtet, ist dieser Sand sehr kurzlebig, da die Einzelkörner während der Diagenese normalerweise so stark verändert werden, dass sie nach einer erneuten Heraushebung und Erosion nicht mehr in ihrer ursprünglichen Form in Erscheinung treten können.

Einteilung und Bezeichnungen [Bearbeiten]In der Bodenkunde ist der Sandboden die grobkörnigste der vier Hauptbodenarten. Nach der im deutschsprachigen Raum bevorzugten Einteilung nach DIN 4022 werden folgende Korngrößeneinteilungen (Kornklasseneinteilung auf Grundlage des Äquivalentdurchmessers) unterschieden:

Sand (S) Korngröße Grobsand (gS) 0,63 - 2,0 mm Mittelsand (mS) 0,20 - 0,63 mm Feinsand (fS) 0,063 - 0,20 mm In der Praxis findet man jedoch auch geringfügig andere Klassengrenzen und Bezeichnungen. Nachfolgende Aufzählung nennt weitere Begrifflichkeiten:

Zusammensetzung [Bearbeiten]

- Grobschluff und Sand werden nach der Einteilung nach Von Engelhardt seit 1953 als Psammite bezeichnet.

- Gröberer Sand heißt in Norddeutschland Grand, eine Bezeichnung, die auch in der Einteilung nach von Engelhardt für einen Korngrößenbereich verwendet wird, der den größten Teil der Grobsand- und der Feinkiesklasse der DIN-Norm umfasst.

- Sande, die hauptsächlich aus Körnern einer Korngröße bestehen, nennt man gut sortiert; entsprechend sind schlecht sortierte Sande solche, in denen ein breites Korngrößenspektrum vertreten ist.

- Schlechtsortierte Sande mit hohem Feinanteil sind bindiger als gutsortierte, feine Sande bindiger als grobe: Sie nehmen – unabhängig von jeweiliger Korngröße und der Gesteinsart – mehr Wasser, aber auch mehr Bindemittel auf.

- Rundsande bestehen primär aus rundlichen Komponenten (wie Geröll oder Kies), kantige Sande aus ebensolchen Körnern (Bruch- und Brechsande). Scharfkantige Sande werden wesentlich kompakter, sowohl in der Sedimentation als auch in Baumaterialien, weil sich die Körner verkanten. Sie lassen sich aber schlechter mischen und belasten alle Werkzeuge enorm.

- Flugsand nennt man den infolge seiner Reinheit, seiner geringen Korngröße und seiner guten Sortierung durch den Wind besonders leicht beweglichen Sand. Bei großflächigem Auftreten tritt er oft in Form von Dünen in Erscheinung.

- Geringbindige Sande können bei geringer Wasserzugabe „verflüssigt“ werden und sind dann unter dem Begriff Treibsand bekannt.

- Flusssand ist ein feinkörniger Sand, der in einem Fluss von der Strömung transportiert und dabei sortiert wurde und dessen Körner durch Reibung gerundet wurden. Er ist ausgewaschen und hat somit einen geringen Anteil an Schwebstoffen und an wasserlöslichen Stoffen. Er wird daher gern als Rohstoff in der Bauwirtschaft bzw. für die Betonherstellung verwendet. Fossile Flusssande nennt man Grubensand, sie werden in Sandgruben abgebaut und müssen meist noch gewaschen werden, weil sich tonige und organische Bestandteile angereichert haben.

- Bruchsand, natürliche scharfkantige Sande als Verwitterungsprodukt

- Quetschsand ist künstlich hergestellter Sand mit gebrochenen, scharfkantigen Körnern, siehe Gebrochene Mineralstoffe

Die mineralische Zusammensetzung von Sand kann je nach Ort sehr stark variieren. Der Großteil der Sandvorkommen besteht allerdings aus Quarz (Siliciumdioxid SiO2), denn er ist nicht nur häufig, sondern auf Grund seiner Härte (7 auf der 10-stufigen Mohs'schen Härteskala) und seiner chemischen Widerstandsfähigkeit besonders verwitterungsbeständig.

Es sind aber auch andere Sandtypen möglich. Zum Beispiel besteht der feine, weiße Sand am Strand von Koralleninseln aus zermahlenen Korallenskeletten, und damit überwiegend aus Calciumcarbonat (CaCO3). Bekannt ist auch der grüne Sand von den Stränden Hawaiis, der seine Farbe durch das vulkanogene Olivin erhält. Feinkörnig verwitterter Basalt sorgt für schwarzen Sand, der vor allem aus mafischen Mineralen besteht. Nach der Zusammensetzung des Sandes unterscheidet man beispielsweise:

- Muschelsand, der aus mehr oder minder gerundeten Partikeln von Molluskenschalen besteht,

- Korallensand, der aus den kalkigen Resten der Korallen besteht und überall auf Koralleninseln vorkommt

- Vulkanischer Sand, der entweder aus Lava entstand, die durch die Kraft fließenden Wassers oder den Wellenschlag am Ufer größerer Gewässer erodiert wurde oder der sich in Form von vulkanischer Asche unmittelbar bei Vulkanausbrüchen bildete."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sand . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-15]

Man gewinnt Lehm als

Lehm ist nicht der einzige Erdbaustoff, der sich ungebrannt verarbeiten lässt. Auch Grassoden (also humusreiche Erde mit Grasbewuchs) können zum Bau sog. Grassodengebäude (sod house) verwendet werden. Für die Tropen kommt diese Bauweise wegen des damit verbundenen Ungeziefers nicht in Frage.

Abb.: Grassodenhäuser, Island

[Bildquelle: come from away. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/cfa/2618450180/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-15. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

"Ein Grassodenhaus hat Wände aus gestapelten Grassoden, die zumeist direkt vor Ort gestochen werden. Bauten mit Wänden in dieser Technik gab und gibt es gewöhnlich an Orten mit extremen Klimaschwankungen, insbesondere großer Kälte und wenig anderem Baumaterial wie Holz oder Stein. Island: Die ursprüngliche Bauweise auf Island fand mit Grassoden statt. Diese Häuser werden in den Boden gegraben, die dabei anfallenden Grassoden wurden zur Wand aufgestapelt. Sogar Kirchen wurden so gebaut.

Nordseeküste: Auch in Nordfriesland ist diese Bebauung bekannt. Siehe Rungholt.Nordamerika: In Nordamerika wurden Grassodenhäuser bei der Besiedlung der Prärie häufig als billige erste Behausung genutzt, da es hier oftmals kein leicht erreichbares Holz oder Steine als Baustoff gab. Da der Homestead Act besagte, dass man Land auch alleine dadurch erwerben konnte, indem man dort eine Behausung baute und das Land fünf Jahre lang kultivierte, fungierten Grassodenhäuser in der nordamerikanischen Prärie oftmals als die Keimzelle eines Grundbesitzes. Das dicke und vergleichsweise tiefe Wurzelwerk der Präriegräser gab den Wänden guten Halt. Diese boten zwar eine gute Isolation, hielten das Raumklima jedoch eher feucht. Von diesen Bauten scheinen sich bis heute keine erhalten zu haben."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grassodenhaus. -- Zugriff am 2009-06-15]

Minke (2009, S. 11f.) nennt folgende Vor- und Nachteile des Baustoffs Lehm:

Nachteile:

Abb.: Trockenrisse in Lehmziegeln

[Bildquelle: snarl. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/snarl/108302023/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-15. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Vorteile:

Da Lehm kein normierter Baustoff ist, muss der jeweilige Lehm zumindest mit einfachen Prüfmethoden auf seine Eigenschaften untersucht werden. Diese sind mit den Kenntnissen über daraus verfertigte Lehmbaustoffe zu verknüpfen. Nötigenfalls muss Lehm im Labor geprüft werden.

Für die einfache Prüfung muss humusfreier Lehm verwendet werden. Der Lehm soll so feucht bzw. trocken sein, dass man ihn gerade noch zu einer Kugel ballen kann.

Einfache Prüfverfahren sind:

Je nachdem ob die Lehmbaustoffe verwendet werden

werden an die Lehmbaustoffe und Lehmbauteile unterschiedliche Anforderungen gestellt.

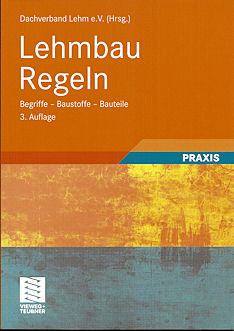

Nach

Lehmbau Regeln : Begriffe, Baustoffe, Bauteile / Dachverband Lehm e.V. (Hrsg.). -- 3., überarb. Aufl. -- Wiesbaden : Vieweg + Teubner, 2009. -- XIX, 120 S. : Ill. ; 21 cm. -- (Praxis). -- ISBN 978-3-8348-0189-0.

unterscheidet man:

| Lehmbaustoff | Beschreibung | Trockenrohdichte kg/m³ | Druckfestigkeit N/mm² |

Verwendung | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stampflehm (STL) | erdfeucht aufbereitet, gestampft oder gepresst | 1700 - 2400 | 2 - 5 | Stampfen in Schalung; Herstellung von Lehmsteinen durch Pressen oder Stampfen; Stampflehmfußböden |

|

| Wellerlehm (WL) | aufbereitetes Gemisch aus Stroh und Lehm | 1400 - 1700 | 1 | tragende oder nichttragende Wände | |

| Faserlehm (FL), Strohlehm (SL) | weich bis breiig aufbereitetes Gemisch aus pflanzlichen Fasern (Strohlehm: Stroh) und Lehm | 1200 - 1700 | Ausfachung von Wänden und Decken; putzähnliche Aufträge; Lehmsteine und Lehmplatten |

||

| Leichtlehm (LL) | flüssig bis breiig aufbereiteter, mit

Leichtzuschlägen vermischter Lehm Mischungen der unten genannten Zuschlagstoffe sind möglich |

leichte Mischungen: 300 - 800 schwere Mischungen: |

In Schalungen zum Bauteil verdichtet oder zu

Steinen, großformatigen Elementen oder Platten geformt:

Außen- und Innenwände, |

||

| Holzleichtlehm (HLL) | Leichtlehm mit Zuschlag von Holzschnitzeln und dergleichen | ||||

| Strohleichtlehm (SLL) | Leichtlehm mit Zuschlag von Stroh | ||||

| Faserleichtlehm (FLL) | Leichtlehm mit Zuschlag von gegen Einbaufeuchte beständigen Faserstoffen | ||||

| Mineralischer Leichtlehm (MLL) | Leichtlehm mit Zuschlag von porigen natürlichen oder künstlichen Gesteinen wie Bims, Blähton, Perlite, Blähschiefer, Blähglas usw. | ||||

| Lehmschüttungen (LT) | schüttfähige, lehmgebundene Aufbereitungen von Lehm und evtl. Zuschlagsstoffen (z.B. Sand, Holz) | 300 - 2200 (unter 1200 = Leichtlehmschüttungen) |

Massefüllung von Geschoßdecken; Verfüllen von Hohlräumern |

||

| Lehmsteine (LS) | meist quaderförmige, trockene Lehmbaustoffe | 600 - 2200 (unter 1200 = Leichtlehmsteine) |

2 - 4 | Verwendungsklassen:

I: verputztes, der Witterung ausgesetztes

Außenmauerwerk |

|

| Lehmplatten (LP) | plattenförmig | 300 - 1800 (unter 1200 = Leichtlehmplatten) |

vermauert oder trocken miteinander verbunden: nichttragende Wände; Ausfachungen von Decken oder Dachschrägen; Deckenauflagen; Bekleidungen; Putzträgerplatten |

||

| Lehmmörtel (LM) | mit feinkörnigen oder feinfaserigen Zuschlagsstoffen abgemagerte Baulehme | 600 - 1800 (unter 1200 = Leichtlehmmörtel) |

|||

| Lehm-Mauermörtel (LMM) | Vermauern von Lehmsteinen oder anderen künstlichen oder natürlichen Steinen | ||||

| Lehm-Putzmörtel (LPM) | Verputz im Innenbereich und witterungsgeschützten Außenbereich | ||||

| Lehm-Spritzmörtel (LSM) | Ausfachung von Holzkonstruktionen: Vorsatzschalen; Innenwände; Deckenfüllung |

||||

Man unterscheidet auch:

Abb.: Lehmmörtel, Rheinischen Freilichtmuseum Kommern

[Bild: A. Payer, 2009]

Abb.: Ausfachender Lehmbaustoff, Rheinischen Freilichtmuseum Kommern

[Bild: A. Payer, 2009]

Abb.: Feuchter Einbau von Lehm, Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum Kommern

[Bild: A. Payer, 2009]

Verringerung der Rissbildung beim Austrocknen:

Erhöhung der Wasserfestigkeit:

Erhöhung der Bindekraft:

Erhöhung der Druckfestigkeit:

Erhöhung der Abriebfestigkeit:

Erhöhung der Wärmedämmung:

Magerer, krümeliger, erdfeuchter Lehm muss in der Regel nicht aufbereitet werden. Fetter, klumpiger oder aus unterschiedlich fetten Schichten abgebauter Lehm muss vor der Verarbeitung

werden.

Methoden bzw. Arbeitsschritte der Aufbereitung sind:

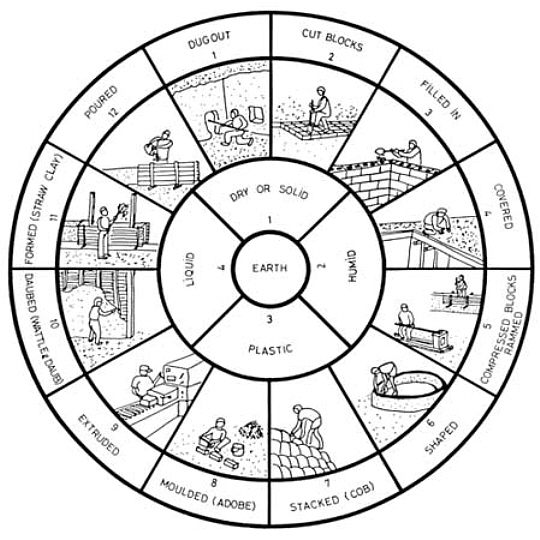

In Anlehnung an

Houben, Hugo <1944 - > ; Guillaud, Hubert <1952 - >: Traité de construction en terre / auteurs, Hugo Houben et Hubert Guillaud ; illustrations, Fabienne Dath, avec la collaboration de Patrice Doat ... [et al.]. -- Marseille : Parenthèses, ©1989. -- 355 S. : Ill. ; 30 cm. -- ISBN: 2863640410. -- (L’Encyclopédie de la construction en terre ; v. 1)

unterscheidet das Aurobindo Earth Institute:

Abb.: Die 12 Techniken des Lehmbaus

[Quelle: AEI]

dug out = in Lehm gegrabene Architektur

cut blocks = geschnittene Erdblöcke

filled in = eingefüllter Lehm

covered = Abdeckung mit Lehm

compressed blocks (rammed) = Stampflehm und Presslehm

shaped = geformter Lehm

stacked (cob) = geschichteter Lehm

Moduled (adobe) = Adobe (Lehmziegel)

extruded = stranggepresster Lehm

daubed (Wattle & daub) = Lehmbewurf

formed (straw clay) = Lehmformplatten

poured = Gusslehm

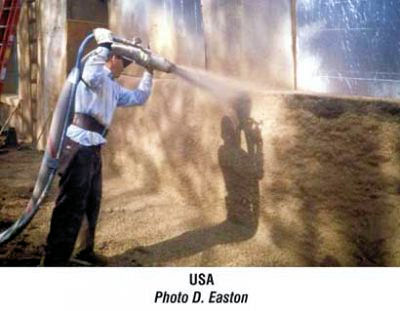

projected = Spritzlehm

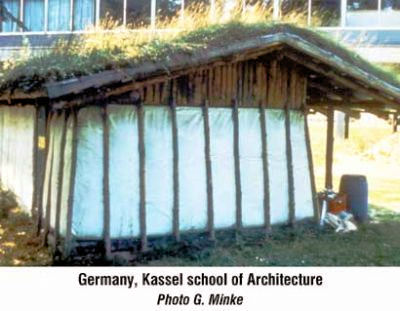

Gernot Minke (2009) unterscheidet:

Stampflehmbau

Lehmsteinbau

großformatige Lehmblöcke und Lehmplatten

direktes Formen mit Nasslehm

Nasslehm-Fülltechniken für Fachwerk- und Skelettbauweise

Stampf-, Schütt- und Pumptechniken für Leichtlehm

Lehmputze

Vertikal oder horizontal in Lehm gegrabene Architektur.

Beispiele:

Abb.: Gebiete, in denen es yaodong = 窰洞

gibt

[Bildquelle: User:Ran / Wikipedia. GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: In Löss-Lehm gegrabene Wohnungen (yaodong

窰洞),

Luoyang = 洛阳,

Henan =

河南, China

[Bildquelle: kevinpoh. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kevinpoh/3596950930/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

"A yaodong (窰洞) is a dugout used as an abode or shelter in China. Yaodongs are common in north China, especially on the Loess Plateau. The history of yaodongs goes back centuries, and they continue to be used. Description

Yaodongs are usually carved out of a generally vertical side of a loess hill. If the side is not vertical, it must be cut vertical. The silty soil is soft and easy to dig. The cross section of a yaodong is similar to that of a cave: a rectangle in the lower part connected to a semicircle in the upper part. The width at the floor is from 3 to 4 meters, and the highest point in the ceiling is around 3 meters or higher. The depth of a yaodong can be 5 meters or more. Windows and doors are installed at the opening of the yaodong. The inner side wall is usually plastered with lime to make it white. A platform called kang is built to be used as a bed. A fireplace is built beside the kang and the smoke and hot gas go through the built-in channels inside the kang to heat it before exiting to outdoor through a chimney.

The hill, which is practically infinite in thickness, that separates the indoor space and outdoor serves as an effective insulator that keeps the inside of a yaodong warm in cold seasons and cool in hot seasons. Consequently, very little heating is required in winter, and in summer, it is as cool as an air-conditioned room.

More elaborate yaodongs may have a facade built with stones with fine patterns carved on the surface.

Yaodongs can also be constructed with stones or bricks as stand-alone structures. Often, three or more yaodongs in a row are constructed. First, stones or bricks are used to build the arch-shaped structure, and then soil is used to fill up the external space above the arches to make a thick and flat roof.

The most famous yaodongs in China are perhaps those in Yan'an. The communists led by Mao Zedong headquartered there in 1935-1948 and lived in yaodongs. Edgar Snow visited Mao and his party in Yan'an and wrote Red Star Over China. An estimated 40 million people in northern China live in yaodongs.

Further readingGolany, Gideon S. Chinese Earth-Sheltered Dwellings. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, Press, 1992."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yaodong . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-11]

Abb.: Eingang zu in Löss-Lehm gegrabene Wohnung (yaodong

窰洞)

[Bildquelle: nozomiiqel. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/nozomiiqel/261373083/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-11. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Innenraum einer Löss-Lehm gegrabene Wohnung (yaodong

窰洞)

[Bildquelle: gin_e. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/gin_e/1447188698/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-11.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Lage von Matmâta = مطماطة

©MS Encarta

Abb.: Höhlenwohnung, Matmâta, Tunesien

[Bildquelle: Bernard Gagnon / Wikipedia. GNU FDLIcense]

"Matmâta or Metmata is a small Berber speaking town in southern Tunisia. Some of the local Berber residents live in traditional underground "troglodyte" structures. The structures typical for the village are created by digging a large pit in the ground. Around the perimeter of this pit artificial caves are then dug to be used as rooms, with some homes comprised of multiple pits, connected by trench-like passageways. This type of home was made famous by serving as the location of the Lars Homestead, home to Luke Skywalker, his Aunt Beru Lars and Uncle Owen Lars for the Star Wars movies. The Lars Homestead was in fact the Hotel Sidi Driss, which offers traditional troglodyte accommodations. One of Call of Duty 2 missions takes place in Matmâta as part of North African Campaign.

HistoryAncient history

The history of this extraordinary place is not known, except from tales carried from generation to generation. The most probable one says that underground homes were first built in ancient times, when the Roman empire sent two Egyptian tribes to make their own homes in the Matmata region, after one of the Punic wars, with permission to kill every human being in their way. The dwellers of the region had to leave their homes and to dig caves in the ground to hide from those invaders, but they left their underground shelters in the night to attack invaders, which appeared to be very effective in sending the killer groups away from Matmata. A myth was made those days, that monsters emerge from beneath the ground and kill land usurpers. In any case, the underground settlements remained hidden in very hostile area for centuries, and no one had any knowledge of their existence until 1967.

The way of survival in those severe conditions was difficult: since Tunisia is famous for massive olive oil production, the men went searching for work north of the villages every spring, when the olive season began, getting back home in autumn, when the season was over. They were usually paid in olive oil, which they traded for other goods (in present days for money), and thus provided enough food, clothes and other things for normal life of their families.

Modern rediscoveryIt was not generally known until 1967 that there were regular settlements in this area besides wandering nomad tribes. That year, intensive rains that lasted for 22 days innundated the troglodyte homes and caused many of them to collapse. In order to get help from the authorities, a delegation was sent to the community center of the region in the town of Gabes. The visit came as a surprise, but help was provided, and the above ground settlement of Matmata was built. However, most of the people continued their lives in re-built underground homes, and only a few of the families moved to the new surface dwellings.

Today, Matmata is a well-known tourist attraction, and most of the population lives on tourism and folklore exhibitions in their homes."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matmata . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-11]

Abb.: Hotel Marhala, Matmâta, Tunesien

[Bildquelle: scottroberts. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/scottroberts/2192865673/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-11. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Eingang zu einem Hotel, Matmâta, Tunesien

[Bildquelle: bigdani. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/bigdani/2876323357/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-11.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

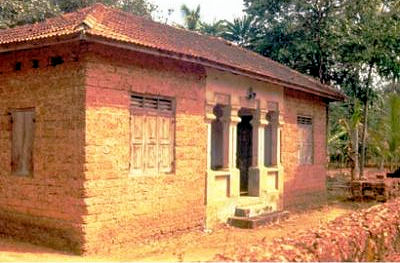

Vor allem aus tropischen Lateritböden schneidet man Erdblöcke, die man als Bausteine verwendet.

"Laterit (von lat. laterus, „Ziegelstein“) ist ein in tropischen Gebieten häufig auftretendes Oberflächenprodukt, das durch intensive und lang anhaltende Verwitterung der zugrunde liegenden Gesteine entsteht. An der Luft getrockneter Laterit dient in manchen Gegenden der Erde als Bauziegel. Abgrenzung

In den Geowissenschaften werden nur die mineralogisch-chemisch am stärksten veränderten Verwitterungsprodukte als Laterit bezeichnet; die schwächer verwitterten, aber häufig ganz ähnlich aussehenden und in den Tropen und Subtropen am meisten verbreiteten Oberflächenbildungen hingegen als Saprolith. Beide Verwitterungsbildungen können als Rückstands- oder Residualgesteine (siehe Sedimentgesteine) klassifiziert werden.

Entstehung und ZusammensetzungDie Gesteine an der Erdoberfläche werden unter dem Einfluss der hohen Temperaturen und Niederschläge der Tropen tiefgründig zersetzt, wobei die in den Ausgangsgesteinen auftretenden Minerale weitgehend gelöst werden. Bei dieser chemischen Verwitterung wird ein hoher Anteil der leichter löslichen Elemente Natrium, Kalium, Calcium, Magnesium und Silicium (Kieselsäure) im durchsickernden Niederschlagswasser fortgeführt, wodurch es zu einer starken Rückstandsanreicherung der schwerer löslichen Elemente Eisen und Aluminium kommt (Ferrallitisierung).

Laterite bestehen neben dem aus dem Ausgangsgestein stammenden, nur schwer löslichen Quarz vor allem aus den bei der Verwitterung neu gebildeten Mineralen Kaolinit, Goethit, Hämatit und Gibbsit (Hydrargillit). Die Eisenoxide Goethit und Hämatit bedingen die meist rotbraune Farbe der Laterite, welche zumeist nur wenige Meter mächtig sind, jedoch auch wesentlich höhere Mächtigkeiten erreichen können.

Laterite sind entweder weich bis bröcklig oder hart und physikalisch widerstandsfähig; sie können in Blöcken aus dem Boden gehauen und als Bausteine für einfache Häuser verwendet werden. Berühmte historische Beispiele sind die aus Lateritsteinen errichteten Tempelanlagen von Angkor. Auf diesen Gebrauch und das lateinische Wort later = Ziegelstein geht der Begriff Laterit zurück. Heutzutage werden härtere Lateritanteile vor allem im örtlichen Straßenbau (Lateritpisten) verwendet. Auch wird Lateritkies gern in Aquarien eingesetzt, wo er das Wachstum tropischer Pflanzen günstig beeinflussen soll.

Lateritische Böden bilden den obersten Bereich der Lateritdecken; hierfür sind in der Bodenkunde spezielle Bezeichnungen in Gebrauch (Oxisol, Latosol u.a.).

VorkommenLaterite sind über nahezu allen Gesteinsarten in Gebieten entstanden, die kein starkes Relief aufweisen, sodass die Verwitterungsdecken erhalten blieben und nicht der Erosion zum Opfer fielen. Laterite in heutzutage nicht-tropischen Klimagebieten sind ein Produkt früherer geologischer Epochen.

Lagerstätten in LateritenDie Lateritisierung ist besonders bedeutsam für die Bildung lateritischer Lagerstätten. Bauxite sind aluminium-reiche Lateritvarietäten, die sich aus vielen Gesteinen bilden können, wenn die Drainage besonders intensiv ist. Das bewirkt eine sehr starke Entfernung von Silicium und eine entsprechend hohe Anreicherung von Aluminium insbesondere als Hydrargillit. Die Lateritisierung ultramafischer Gesteine (Serpentinit, Dunit, Peridotit mit 0,2 - 0,3 % Ni) kann zu einer bedeutenden Nickelanreicherung führen. Zwei Arten lateritischer Nickelerze sind zu unterscheiden: Ein sehr eisenreiches Ni-Limonit-Erz an der Oberfläche enthält 1 - 2 % Nickel an Goethit gebunden, der infolge weitgehender Lösung von Silicium und Magnesium stark angereichert ist. Unterhalb dieser Zone steht in manchen Vorkommen Nickel-Silikat-Erz mit häufig mehr als 2 % Ni an, das in Silikaten insbesondere Serpentin gebunden ist. Darüber hinaus ist in Taschen und auf Klüften des Serpentinits grüner Garnierit in geringer Menge, aber mit sehr hohen Nickelgehalten zumeist 20 - 40 % ausgeschieden. Hierbei handelt es sich um ein Gemenge verschiedener Ni-reicher Schichtsilikate. Das gesamte in der Silikat-Zone vorliegende Nickel wurde aus der überlagernden Goethit-Zone gelöst und deszendent verlagert. Die Abwesenheit der Goethit-Zone ist auf Erosion zurückzuführen.

Literatur

- G.J.J. Aleva (Hrsg.): Laterites. Concepts, Geology, Morphology and Chemistry. ISRIC, Wageningen 1994, ISBN 90-6672-053-0.

- G. Bardossy und G.J.J. Aleva: Lateritic Bauxites. In: Developments in Economic Geology. 27, Elsevier, Amsterdam 1990, ISBN 0-444-98811-4.

- J.P. Golightly: Nickeliferous Laterite Deposits. In: Economic Geology. 75, 1981, S. 710-735.

- W. Schellmann: Geochemical Principles of Lateritic Nickel Ore Formation. In: Proceedings of the 2. International Seminar of Lateritisation Processes. Sao Paulo 1983, S. 119-135."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laterit . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-12]

Man schneidet solche Bausteine aus zwei Arten von Laterit:

harte Erdkrusten: Orissa (ଓଡ଼ିଶା) (Indien) und Burkina Faso

Abb.: Lateritbaustein, Angadipuram, Indien (Maßstab = 1 cm)

[Bildquelle: Werner Schellmann / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons Lizenz

(Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Laterithaus, bei Soranad, Kerala, Indien

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Lateritsteine: Basilica Bom Jesus, Goa, Indien

[Bildquelle: mckaysavage. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mckaysavage/342061956/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Schneiden von Lateritblöcken, bei Narangarh, Orissa (ଓଡ଼ିଶା),

Indien

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Zuhauen von Lateritblöcken, Orissa (ଓଡ଼ିଶା),

Indien

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Postamt aus Lateritblöcken, Kurdha, Orissa (ଓଡ଼ିଶା),

Indien

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Lehm kann eingefüllt werden:

Abb.: Lehmmauerkonstruktion mit lehmgefüllten Altreifen, Brighton Earthship,

Brighton, East Sussex, Großbritannien

[Bildquelle: Dominic's pics. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dominicspics/3288482283/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-16. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Superadobe-Konstruktion

[Bildquelle: ganast. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/anast/538180177/in/photostream/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-14. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Die wichtigsten Baumaterialien: Lehm-Pakete und Stacheldraht

[Bildquelle: London Permaculture. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/naturewise/2768360359/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-14. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

"Super Adobe is a form of Earthbag Construction that was developed by Iranian architect Nader Khalili. The technique uses long snake-like sand bags to form a beehive shaped compressive structure that employs arches, domes, and vaults to create single and double-curvature shell structures that are strong and aesthetically pleasing. It has received growing interest for the past two decades in the Natural building and Sustainability movements. Due to Super Adobe’s inexpensive nature, ease in construction, and use of locally available materials, it has also been proposed for use as a long term emergency shelter. Super Adobe is also known as Superadobe (one word), and also Superblock, but never Super Block. History

Although it is not known exactly how long, Earth bag shelters have been used for decades, primarily as implements of refuge in times of war. Military infantrymen have used sand filled sacks to create bunkers and barriers for protection prior to World War I. In the last century more peaceful earthbag buildings have undergone extensive research and are slowly beginning to gain worldwide recognition as a plausible solution to the global epidemic of housing shortages. German architect Frei Otto is said to have experimented with earth bags, as is more recently Gernot Minke. The technique’s current pioneer is Nader Khalili who originally developed the Super Adobe system in 1984 in response to a NASA call for housing designs for future human settlements on the Moon and on Mars. His proposal was to use moon dust to fill the plastic Super Adobe tubes and Velcro together the layers (instead of barbed wire). Some projects have been done using bags as low-tech foundations for Straw-bale construction. They can be covered in a waterproof membrane to keep the straw dry. In 1995 15 refugee shelters were built in Iran, by Nader Khalili and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in response to refugees from the Persian Gulf War. According to Khalili the cluster of 15 domes that was built could have been repeated by the thousands. Unfortunately the government dismantled the camp a few years later. since then, the Super Adobe Method has been put to use in Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Belize, Costa Rica, Chile, Iran, India, Siberia, and Thailand, as well as in the U.S.

MethodologyMaterials

Many different materials can be used to construct Super Adobe. Ideally you would have barbed wire, earth or sand, cement or lime, and Super Adobe fabric tubing (available from Cal-Earth), but the bags can be polypropylene, burlap, or some other material. What is important is that they are UV resistant or else quickly covered in plaster, in this regard you can even use grocery bags that are twisted shut and formed into balls. Virtually any fill material will actually work including un-stabilized sand, earth, gravel, crushed volcanic rock, rice hulls, etc. If the fill material is weak the bags have to be really strong and UV resistant, or else plastered right away. The material can be either wet or dry, but the structure is more stable when the tube's contents have been moistened. Other materials needed include, water, shovels, tampers, scissors, large plugs or pipes (for windows), and small buckets or coffee cans for filling the sacks. If you decide to go the quicker way, then electric or pneumatic tampers can make the tamping easier, electric or gas powered bucket chain that can reach 7m or higher would eliminate the need of manual filling of sacks or tubing using coffee cans or small pails.

ProcessThe foundation for the structure is formed by digging a 12” (aprox. 30,5 cm) deep circular trench with a 8’-14’ (aprox. 2,44-4,26 meter) diameter. 2-3 layers of the polypropylene filled sand tubes (Super Adobe fabric tubing) are set below the ground level in the foundation trench. A rope is anchored to the ground in the center of the circle and used like a compass to trace the shape of the base. Another rope is fastened to the ground on the inside base of the wall and used as a guide to shape the interior radius of the opposite wall of the dome. Ropes can be used from several points around the inside of the base to ensure accuracy of the finished dome. Or you can use a metal pipe and arm unit that is easier to keep level and in-line. On top of each layer of tamped, filled tubes, a loop of barbed wire is placed to help stabilize the location of each consecutive layer. Window voids can be placed in two ways, either by rolling the filled tube back on itself around a circular plug (forming an arched header) or by waiting for the earth mixture to set and sawing out a Gothic or pointed arch void. A round skylight can even be the top of the dome.

It is not recommended to exceed the 14’ (mt 4,26) diameter design in size, but many larger structures have been created by grouping several beehives together to form a sort of connected village of domes. Naturally this lends itself to residential applications, some rooms being for sleeping and some for living. There is a 32' (mt 9,75) dome being constructed in the St. Ignacio area of Belize, which when finished will be the centre dome of an eco-resort complex.

FinishingOnce the corbelled dome is complete, it can be covered in several different kinds of exterior treatments, usually plaster. Khalili developed a system that used 85% earth and 15% cement plaster and which is then covered by “Reptile”, a veneer of grapefruit sized balls of concrete and earth. Reptile is easy to install and because the balls create easy paths for stress, it doesn't crack with time. There are many different possibilities. Some Super Adobe buildings have even been covered by living grass, a kind of Green roof but covering the entire structure. Any exterior treatment and building details would need to be adapted to a region’s specific climatic needs.

Emergency shelters

According to Khalili's website in an emergency, impermanent shelters can be built using only dirt with no cement or lime, and for the sake of speed of construction windows can be punched out later due to the strength of the compressive nature of the dome/beehive. Ordinary sand bags can also be used to form the dome if no Super Adobe tubes can be procured; this in fact was how the original design was developed. There is a great potential for long-term emergency shelters with Super Adobe because of the simplicity of construction. Labor can be unskilled and high physical strength or formal training is unnecessary for the workers, so women and children are able to substantially contribute to the construction process. Local resources can be used with ease, Super Adobe is not an exact art and similar materials may be substituted if the most ideal ones are not readily available. In an interview with an AIA (American Institute of Architects) representative, Nader Khalili, super adobe’s founder and figure head said this about the emergency shelter aspects of Super Adobe: “A 400-square-foot (37 m2) house, with bedroom, bathroom, kitchen, and entry-I call it the Eco-Dome-can be put up in about four weeks, by one skilled and four unskilled people. Emergency shelters can go up much more quickly. After the Gulf War, the United Nations sent an architect here. We trained him, and he went to the Persian Gulf and put them up with refugees as they arrived at the camps. Every five incoming refugees put up a simple structure in five days. It's emergency shelter, but if you cover it with waterproofing and stucco, it will last for 30 or more years.”

SustainabilitySuper Adobe and other forms of Earth-Bag Construction are considered sustainable for several reasons. First of all, the system is extremely cheap and easy to build. Soil can be taken right from the site and the bags can be obtained for free or for a low cost. The technique demands few skills. Anyone can learn to do it, which makes this building technique accessible to low income communities. Additionally, the building can be erected very quickly, building with bags goes quicker then with any other Earth-building technique (i.e. Cob, Adobe, etc). Also, the system is very flexible, allowing for alterations in design and construction. This makes customizing a design to a specific individuals needs while the home is under construction relatively unencumbered compared to post permit alterations in modern day construction. Super Adobe is increasingly being realized as a Green building technique. Building sustainably does not just entail a focus on the health of the inhabitants of the structure or the environmental impacts of a certain technique or material. The ethics or social and economic impact of the technique and materials must also be considered. Sustainability implies a level of social awareness paramount to a healthy building culture. Super Adobe’s major ingredient is earth, which is non-toxic and readily available. If the earth is not from the immediate site than locating a nearby source is generally not terribly difficult, such close proximity to a materials source decreases the materials embodied energy, another focus of sustainability. In terms of energy conservation the walls are very thick and have significant thermal mass, which reduces heating and cooling costs as well as provides sound insulation, structural integrity, fire and pest protection. Like traditional adobe or concrete structures the walls are heated throughout the day, while maintaining a comfortable temperature on the inside. Then the heat is released slowly throughout night also contributing to a comfortable interior temperature. Another vital emphasis in green, or sustainable design is a structures connection to its natural environment. In the same interview with the AIA representative mentioned previously, Nader Khalili said this about his reason for creating the Super Adobe technique of construction. “I was searching for a way to create a building that was totally in harmony with nature, that could be available to everybody around the world.”

Properties

Super Adobe has also been proven to be competitively strong by modern western construction standards. Strength and resiliency tests done at Cal-Earth under the supervision of the ICBO (International Conference of Building Officials) showed that under static load testing conditions simulating seismic, wind, and snow loads, the Super Adobe system exceeded by 200 percent the 1991 Uniform Building Code Requirements. Due to this, California granted its first permit for the Earth Bag Construction for the Hesperia Museum and Nature Center. Earth bag shelters have since been built in the U.S., Mexico, Canada, the Bahamas, and Mongolia. Like many Sustainable building techniques, sand bag construction has gained interest in the public eye as environmental consciousness increases.

Criticisms

Structural design issuesSeveral building departments have required that substantial changes be made to designs to meet seismic building codes. Most building codes require positive vertical connections between structural members, but since Super Adobe is reinforced by barb wire placed between sand bag layers, no positive connection exists between bag layers to contain dynamic vertical loads and prevent separation. The Eco-Dome constructed at the Pomona College Organic Farm, in Los Angeles County, for example included a reinforcing rebar and welded wire mesh faced in shotcrete on both the inner and outer surfaces.

Architectural design issuesSome architects criticize Cal-Earth designs as being a 'regressive technique'. In a New York Times article11 Peter Berman, a Montana architect, raised objections over economy of scale. Berman asserts that technology should be foremost in architecture and that buildings should be 'lighter, stronger and more transparent'. Moreover, Berman has stated that he does not view Khalili as a professional, due in most part to his rejection of industrialized processes and products, stating the issues of installing "standard windows and doors".

High labor costsAs an experimental/developmental technique Super Adobe has been criticized as being overly-expensive, since the construction is so proportionally labor-intensive.[citation needed] Super Adobe, for this reason, is well suited for communal, volunteer constructions, or for places where the cost of labor is low.[citation needed] Within a commercial model, Mr. Khalili estimated that a four-bedroom, 2,000-square-foot (190 m2) house would cost $75,000 to build, including labor, materials and utilities.[citation needed]

Poor insulationThe Cal-Earth Eco-Dome design has U-Factors of 0.103 (9.7 R-value) for 18-inch (460 mm) thick walls and 0.253 (3.9 R-value) for a 6-inch (150 mm) thick roof. It should be noted that materials with a low R-value and high thermal mass and specific heat constants typically perform much better than their insulating qualities simulate.

Use of energy intensive or petroleum-based materialsIn the Super Adobe process, cement is mixed with earth in the ratio of 15 percent or more (for the external waterproofing material only). A Cal-Earth design, such as the double Eco-Dome, requires 70,000 lb (32,000 kg) of Portland cement for a structure having less than 800 interior square feet.[citation needed] Also, since earth contains materials such as clay or organic matter that interfere with the binding properties of cement, it may result in inefficient use of cement. In soils with high clay content, Cal-Earth recommends increasing the percentage of cement or lime. Alternatively, petroleum based materials such as asphalt emulsion are applied to the exterior surfaces of the structure for weatherproofing. (However, there are no design restrictions on the waterproofing material, so conceivably any material can be used.)

Bibliography

- Khalili, Nader. "Nader Khalili." Cal-Earth. 19 Jan. 2007 [1].

- Katauskas, Ted. "Dirt-Cheap Houses from Elemental Materials." Architecture Week. Aug. 1998. 19 Jan. 2007 [2].

- Husain, Yasha. "Space-Friendly Architecture: Meet Nader Khalili." Space.com. 17 Nov. 2000. 19 Jan. 2007 [3].

- Sinclair, Cameron, and Kate Stohr. "Super Adobe." Design Like You Give a Damn. Ed. Diana Murphy, Adrian Crabbs, and Cory Reynolds. Ney York: Distributed Art Publishers, Inc., 2006. 104-13.

- Kellogg, Stuart, and James Quigg. "Good Earth." Daily Press. 18 Dec. 2005.

- Freedom Communications, Inc. 22 Jan. 2007 [4].

- Alternative Construction: Contemporary Natural Building Methods. Ed. Lynne Elizabeth and Cassandra Adams. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000.

- Hunter, Kaki, and Donald Kiffmeyer. Earthbag Building. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers, 2004.

- Kennedy, Joseph F. "Building With Earthbags." Natural Building Colloquium. NetWorks Productions. 14 Feb. 2007 [5].

- Aga Khan Development Network. "The Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2004." Sandbag Shelter Prototypes, various locations. 14 Feb. 2007 [6].

- The Green Building Program. "Earth Construction." Sustainable Building Sourcebook. 2006. 14 Feb. 2007 [7].

- NBRC. "NBRC Misc. Photos." NBRC: Other Super Adobe Buildings. 10 Dec. 1997. 14 Feb. 2007 [8].

- CCD. "CS05__Cal-Earth SuperAdobe." Combating Crisis with Design. 20 Sept. 2006. 14 Feb. 2007 [9].

- American Institute of Architects. A Conversation with Nader Khalili. 2004. 14 Feb. 2007 [10].

- New York Times. When Shelter is made from the Earth's Own Dust. 15 Apr 1999 [11]"

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superadobe . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-14]

Abb.: Vorfabrizierte Schablone für Fensteraussparung

[Bildquelle: ken mccown. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kenmccown/2493600619/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-14. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Leichtlehmgefülltes PVC

[Bildquelle: G. Minke / AEI]

Abb.: Leichtlehmgefüllte PVC-Schläuche

[Bildquelle: G. Minke / AEI]

Abb.: Musterhäuser, Cal-Earth, Kalifornien

[Bildquelle: London Permaculture. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/naturewise/2768310617/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-14. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Musterhäuser, Cal-Earth, Kalifornien

[Bildquelle: London Permaculture. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/naturewise/2768391081/. -- Zugriff am

2009-06-14. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Auch marktübliche Hohlblockbausteine (Schalungssteine) kann man in nichttragenden Wänden statt mit Beton mit Lehm ausgießen.

Abb.: Begrünte Dächer, Norðragøta, Eysturoy, Faröer

[Bildquelle: Erik Christensen / Wikipedia. GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Dachbegrünung, California Academy of Sciences

[Bildquelle: Marlith / Wikipedia.

Creative Commons Lizenz

(Namensnennung, share alike)]

"Constructed for low maintenance by intentionally neglecting a wide selection of native plant species, with only the hardiest surviving varieties selected for installation on the roof."

Abb.: Dachbegrünung, School of Art, Design, and Media, Nanyang Technological

University (南洋理工大学), Singapur

[Bildquelle: Taekwonweirdo. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/alanchan/2386344576/. -- Zugriff am 2009-06-24.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Siehe:

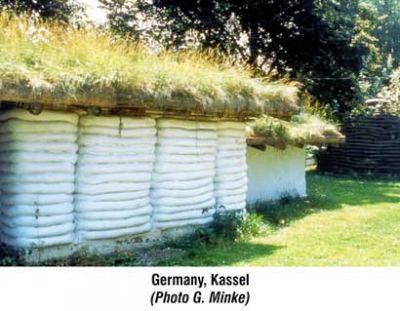

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Minke, Gernot <1937 - >: Dächer begrünen : einfach und wirkungsvoll ; Planung, Ausführungshinweise und Praxistipps. --3., verb. und erw. Aufl. -- Staufen bei Freiburg : Ökobuch, 2006. -- 94 S. : zahlr. Ill. ; 24 cm. -- (Ökobuch Faktum). -- ISBN 978-3-936896-22-0. -- Sehr empfehlenswert.

Gernot Minke nennt folgende Vorteile der Dachbegrünung (a.a.O., S. 10f.):

"Begrünte Dächer tragen also wesentlich zu einem ökologisch-ökonomischen Bauen bei. Wie im folgenden beschrieben wird, tragen sie dazu bei:

- den Freiflächenverbrauch und den Anteil an versiegelter Fläche zu vermindern,

- Sauerstoff zu erzeugen und Kohlendioxid zu binden,

- Staub- und Schmutzpartikel aus der Luft zu filtern und Schadstoffe zu absorbieren,

- das Aufheizen der Dächer und damit die Staubaufwirbelung zu vermindern,

- die Temperaturschwankungen im Tag-Nacht-Zyklus zu reduzieren und

- die Feuchtigkeitsschwankungen in der Luft zu verringern.

Außerdem

- haben sie bei fachgerechter Ausführung eine nahezu unbegrenzte Lebensdauer,

- wirken wärmedämmend,

- schützen im ausgebauten Dachgeschoß im Sommer vor intensiver Sonneneinstrahlung,

- reduzieren Schall,

- gelten als nicht brennbar und

- verzögern den Regenabfluss, wodurch sie das Kanalsystem entlasten.

Und nicht zuletzt

- erzeugen Wildkräuter im Gründach aromatische Gerüche,

- bieten begrünte Dächer Lebensraum für Insekten und Käfer,

- ist ein Gründach ästhetisch und wirkt positiv und entspannend auf die menschliche Gemütsverfassung."

[Quelle: Minke, Gernot <1937 - >: Dächer begrünen : einfach und wirkungsvoll ; Planung, Ausführungshinweise und Praxistipps. --3., verb. und erw. Aufl. -- Staufen bei Freiburg : Ökobuch, 2006. -- 94 S. : zahlr. Ill. ; 24 cm. -- (Ökobuch Faktum). -- ISBN 978-3-936896-22-0. -- S. 10f.]

Abb.: Stampflehm-Boden, Rheinisches Freilichtmuseum Kommern

[Bild: A. Payer, 2009]

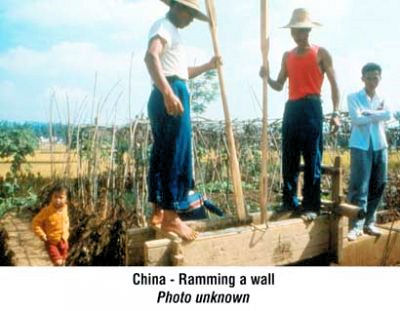

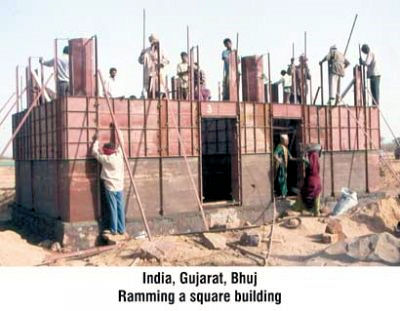

Abb.: Stampflehm-Herstellung, China

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Stampflehmbau, Barichara, Santander, Kolumbien

[Bildquelle: zug55. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/zug55/3356651894/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-12.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Stampflehmbau, Bhuj (ભુજ), Gujarat,

Indien

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Bau mit Stampflehmblöcken, Saint Étienne, Dep. Loire, Frankreich

[Bildquelle: AEI]

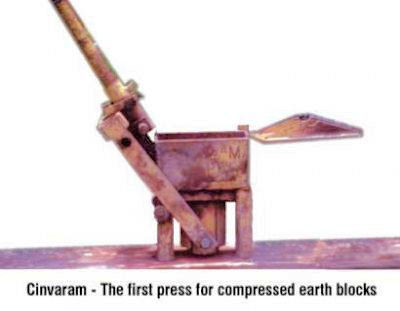

Abb.: Presse für Lehmblöcke, Indien

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Moderne, handbetriebene Lehmpresse

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Höchstes Stampflehmgebäude Deutschlands, Weilburg, Hessen, erbaut vor 1836

[Bildquelle: Oliver Abels / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

"Der Stampflehmbau (archäologisch als Pisé bezeichnet) ist die zweitälteste massive Lehmbau-Art, die seit der Vorzeit belegt ist. Zur Römerzeit wurde sie in Südfrankreich, später auch in Mittelfrankreich bis in das Mittelalter hinein verwendet. Dann geriet sie in Vergessenheit, bis zur erneuten Aufnahme Ende des 18. Jahrhundert in Form des “Lehmpisé-Baus” (frz. piser, span. pisar = stampfen). Verarbeitung

Die Verarbeitung findet statt indem 10-15 cm hohe Schichten (nicht höher, da sonst keine gute Verdichtung mehr möglich ist) erdfeuchten Lehms mit einer Rohdichte von 1700 bis 2200 kg/m³ zwischen eine druckfeste Schalung geschüttet und mit Stampfgeräten verdichtet werden. Gegenüber traditionellen Techniken reduziert maschinelles Stampfen den Zeit- und Arbeitsaufwand. Nach Fertigstellung kann sofort ausgeschalt werden, da es keine Abbind-Wartezeit gibt. Das Herumlaufen sollte aber auf einem gerade ausgeschalten Satz zunächst vermieden werden. Im Falle einer nicht freistehenden Stampflehmwand darf das Verhältnis von Höhe/Tiefe (h/t) den Wert 12 nicht übersteigen.

VorteileEin großer Vorteil der Stampflehmbau-Technik ist, dass sich das in der Natur häufig vorkommende Gemisch aus Lehm, Sand und Schotter für den Stampflehmbau am besten eignet. Die Erzeugung dieses Baustoffs kann ohne zusätzlichen Einsatz von Primärenergie, im Gegensatz zu anderen Baustoffen wie Beton, direkt verwendet werden.

Eine typische solide Stampflehmwand erreicht den F90-Standard, kann aber bei einer Brandbekämpfung zerstört werden infolge des Hochdruckwasserstrahls der Feuerwehrschläuche.

FarbenStampflehm gibt es in verschiedenen Tönungen, somit sollten bei Bauteilen mit stampflehmsichtigen Oberflächen wie im Sichtbeton-Bau rechtzeitig Musterflächen angelegt werden. Stampflehm hat keine verbindliche Farbigkeit, auch bei den Farb-Varianten können, gegeben durch die natürlichen Lehme, Tone und Zuschläge, mehr oder weniger starke Abweichungen der Färbung auftreten. Gewünschte Färbungen können mit Erdpigmenten erreicht werden."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stampflehm . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-12)

Neuere Stampflehm-Bauweisen sind (Einzelheiten bei Minke 2009, S. 65ff.)

Abb.: Kasbah (قصبة) (Zitadelle), Skoura palm grove, Marokko

Abb.: Haus aus Stampflehm (Fujian

Tulou = 福建土楼)

der Hakka (客家), Yongding (永定县), Fujian (永定县), China

[Bildquelle: mars!. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/marshsu/70873614/ . -- Zugriff am 209-06-12. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

"Fujian Tulou (simplified Chinese: 福建土楼; traditional Chinese: 福建土樓; pinyin: Fújiàn Tǔlóu) is a unique Chinese rammed earth building of the Hakka and other people in the mountainous areas in southwestern Fujian, China. They are mostly built between the 12th to the 20th centuries.[1] Tulou is usually a large enclosed building, rectangular or circular in configuration, with a very thick weight supporting earth wall (up to 6 feet thick) and wooden skeletons, from three to five stories high, housing up to 80 families. These earth buildings usually have only one main gate, guarded by 4-5 inch thick wooden doors reinforced with an outer shell of iron plate. The top level of these earth buildings has gun holes for defense against bandits. 46 Fujian Tulou sites including Chuxi tulou cluster, Tianluokeng tulou cluster, Hekeng tulou cluster, Gaobei tulou cluster, Dadi tulou cluster, Hongkeng tulou cluster, Yangxian lou, Huiyuan lou, Zhengfu lou and Hegui lou have been inscribed in 2008 by UNESCO as World Heritage Site,"as exceptional examples of a building tradition and function exemplifying a particular type of communal living and defensive organization, and, in terms of their harmonious relationship with their environment".[1]

TerminologyIn the 80s, Fujian Tulou had being variously called "Hakka tulou", "earth dwelling", "round stronghouse" or simply "tulou". Since the 90s, scholars in Chinese architecture have standardized on the term Fujian Tulou. It is incorrect to assume that all residents of tulou were Hakka people, because there were also large number of southern Fujian people lived in Tulous. Fujian Tulou is the official name adopted by UNESCO.

Part of Hakka tulou belong to Fujian Tulou category. All south Fujian Tulou belongs to Fujian Tulou category, but do not belong to "Hakka tulou".

Furthermore, "Fujian Tulou" is not a synonym for "tulou", but rather a special subgroup of the latter. There are more than 20,000 tulous in Fujian, while there are only three thousand plus "Fujian Tulou".

Fujian Tulous is defined as: "A large multi storey building in southeast Fujian mountainous region for large community living and defense, built with weight bearing rammed earth wall and wood frame structure."[2]

There are about three thousand plus Fujian Tulous located in southwestern region of Fujian province, mostly in the mountainous regions of Yongding County of Longyan City and Nanjing County of Zhangzhou City."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fujian_Tulou . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-12]

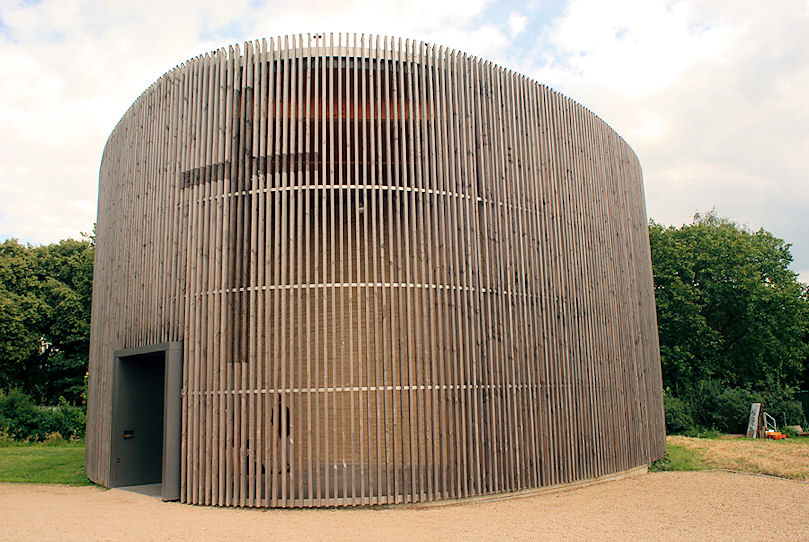

Abb.: Stampflehmwand, Eden Project, Cornwall, England

[Bildquelle: Andrew Dunn / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, shere alike)]

Abb.: Church of the Holy Cross, High Hills of the Santee, Stateburg, South

Carolina, USA, Gebäude aus Stampflehm

[Bildquelle: Pollinator / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

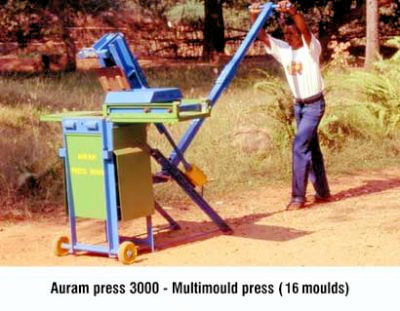

Abb.: Kapelle der Versöhnung, Berlin Mitte, 2000 von Martin Rauch in

Stampflehmbauweise errichtet, Ummantelung mit Holzstäben

[Bildquelle: super.heavy. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/adamcnelson/1225981136/in/photostream/ . --

Zugriff am 2009-06-12. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Umgang der Kapelle der Versöhnung, Berlin Mitte, 2000 von Martin Rauch in

Stampflehmbauweise errichtet, Ummantelung mit Holzstäben

[Bildquelle: mistersmed. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mistersmed/3127429548/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-12. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Inneres der Kapelle der Versöhnung, Berlin Mitte, 2000 von Martin Rauch in

Stampflehmbauweise errichtet

[Bildquelle: super.heavy. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/adamcnelson/1225982386/ -- Zugriff am

2009-06-12. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

"Die Kapelle der Versöhnung ist eine Kirche in der Bernauer Straße im Berliner Bezirk Mitte, die 2000 auf dem Fundament der Versöhnungskirche in Lehmbauweise gebaut wurde. Sie ist Teil der Gedenkstätte Berliner Mauer. Geschichte

Durch den Bau der Berliner Mauer wurde auch die Versöhnungsgemeinde geteilt. Ab 1961 war die 1894 gebaute Versöhnungskirche für die im Westteil der Stadt gelegene Gemeinde nicht mehr zugänglich, weil sie auf dem „Todesstreifen“ zwischen innerer und äußerer Mauer stand. 1985 wurde sie dann schließlich von der DDR gesprengt. Nach der Wende erhielt die Gemeinde 1995 das Grundstück mit der Auflage einer sakralen Nutzung zurück.

Die Architekten Peter Sassenroth und Rudolf Reitermann entwarfen einen ungewöhnlichen Kirchenbau. Auf den Fundamenten des Chorraums wurde ein ovaler Kirchenraum von Lehmbaukünstler Martin Rauch in Stampflehmbauweise errichtet, der von außen mit Holzstäben ummantelt ist. Es ist seit mehr als 100 Jahren der erste öffentlich gebaute Lehmbau in Deutschland. So weit wie möglich wurden Materialien der Versöhnungskirche in dem Bau verarbeitet. Das Retabel wurde in den schlichten Innenraum integriert, und Teile des Bauschutts wurden zermahlen als Zusatz in die Lehmmasse gegeben. Die geretteten Glocken sind in einem Glockengerüst außerhalb der Kapelle aufgehängt. Der Grundriss der Versöhnungskirche ist um die Kapelle markiert.

Am 9. November 2000 wurde die Kapelle der Versöhnung eingeweiht und ist Teil der Gedenkstätte Berliner Mauer in der Bernauer Straße. Im Gemeindehaus, das 1965 als Ersatz für die unzugängliche Kirche gebaut wurde, ist das dazugehörige Dokumentationszentrum untergebracht.

Andachten für die Toten an der Berliner MauerSeit dem 13. August 2005 findet in der Kapelle der Versöhnung täglich von Dienstag bis Freitag um 12 Uhr mittags eine 15-minütige Andacht statt, in der die Biografie eines an der Berliner Mauer Gestorbenen verlesen wird. Die Biographien sind das Ergebnis eines Kooperationsprojekts des Vereins Berliner Mauer und des Zentrums für Zeithistorische Forschung in Potsdam, in dem Historiker die Biografien von Maueropfern recherchieren."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kapelle_der_Vers%C3%B6hnung . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-12]

Abb.: Formung eines Getreidespeichers, Jos, Plateau State, Nigeria

[Bildquelle: AEI]

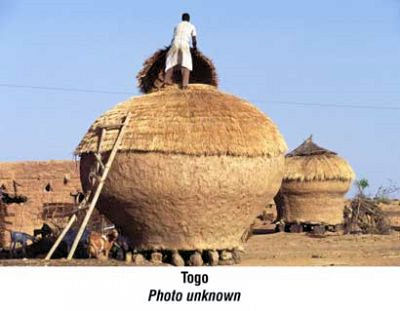

Abb.: Getreidespeicher, Togo

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Speicher, Tiébélé, Burkina Faso

[Bildquelle: Rita Willaert. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rietje/3381542754/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-13.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Lemschichtung (cob)

[Bildquelle: Fountains of Bryn Mawr / Wikipedia. GNU FDLIcense]

"Cob is a building material consisting of clay, sand, straw, water, and earth, similar to adobe. Cob is fireproof, resistant to seismic activity, and inexpensive. It can be used to create artistic, sculptural forms and has been revived in recent years by the natural building and sustainability movements. History and usage

Cob is an ancient building material, that has possibly been used for construction since prehistoric times. Cobwork (tabya) first appeared in the Maghreb and al-Andalus in the 11th century and was first described in detail by Ibn Khaldun in the 14th century. Cobwork later spread to other parts of Europe from the 12th century onwards.[1]

Cob structures can be found in a variety of climates across the globe; In the UK it is most strongly associated with counties of Devon and Cornwall in the West Country; the Vale of Glamorgan and Gower peninsula in Wales; Donegal Bay in Ulster and Munster, South-West Ireland; and Finisterre in Brittany where many homes have survived over 500 years and are still inhabited. Many old cob buildings can be found in Africa, the Middle East, Wales, Devon, Ireland, Cornwall, Brittany and some parts of the eastern United States. Traditionally, English cob was made by mixing the clay-based subsoil with straw and water using oxen to trample it. The earthen mixture was then ladled onto a stone foundation in courses and trodden onto the wall by workers in a process known as cobbing. The construction would progress according to the time required for the prior course to dry. After drying, the walls would be trimmed and the next course built, with lintels for later openings such as doors and windows being placed as the wall takes shape.

The walls of a cob house were generally about 24 inches thick, and windows were correspondingly deepset giving the homes a characteristic internal appearance. The thick walls provided excellent thermal mass which was easy to keep warm in winter and cool in summer. Walls with a high thermal mass value act as a thermal flywheel inside the home. The material has a long life span even in rainy climates, provided a tall foundation and large roof overhang are present.

Modern cob buildingsWhen Kevin McCabe built a two-storey, four bedroom cob house in England in 1994, it was reputedly the first cob residence built in the country in 70 years. His methods remained very traditional; the only innovations he added were using a tractor to mix the cob itself, and adding sand or shillet (a gravel of crushed shale) to reduce the shrinkage.

From 2002 to 2004, sustainability enthusiast Rob Hopkins initiated the building of a cob house for his family, the first new one in Ireland in about one hundred years. It was undertaken as a community project, but destroyed by an unknown arsonist shortly before completion.[2]

In 2006, a modern, four-bedroom cob house in Worcestershire, UK, designed by Associated Architects sold for £745 000. Cobtun House was built in 2001 and won the Royal Institute of British Architects' Sustainable Building of the Year award in 2005. The total construction cost was £300 000, but the metre-thick cob outer wall cost only £20 000.[3]

In the Pacific Northwest of North America there has been a resurgence of cob building both as an alternative building practice and one desired for its form, function and cost effectiveness. There are more than ten cob houses in the Southern Gulf Islands of British Columbia built by Pat Hennebery, Tracy Calvert, Elke Cole and the Cobworks workshops.

In 2007, Ann and Gord Baird began constructing a two-storey cob house in Victoria, British Columbia for an estimated $210,000 CDN. The 2,150 sq. ft. home includes heated floors, solar panels and a southern exposure for passive solar heating. [4]

The building process known as "Oregon Cob" is one which was refined by Welsh architect Ianto Evans and researcher Linda Smiley in the 1980s. Oregon Cob integrates the variation of wall layup technique which uses loaves of mud mixed with sand and straw with a rounded architectural stylism.[5][6]

Reference Works

- Building With Cob, A Step by Step Guide by Adam Weismann and Katy Bryce. Published by Green Books ; 2006, ISBN 1-903998-727.

- The Hand-Sculpted House: A Philosophical and Practical Guide to Building a Cob Cottage (The Real Goods Solar Living Book) by Ianto Evans, Michael G. Smith, Linda Smiley, Deanne Bednar (Illustrator), Chelsea Green Publishing Company; (June 2002), ISBN 1-890132-34-9."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cob_(building). -- Zugriff am 2009-06-13]

Andere Lehmschichttechniken (vor allem im Fachwerkbau) sind:

Wickelstaken aus Strohlehm

Lehmflaschen (flaschenförmig geformte Strohballen, die mit Lehm umhüllt werden)

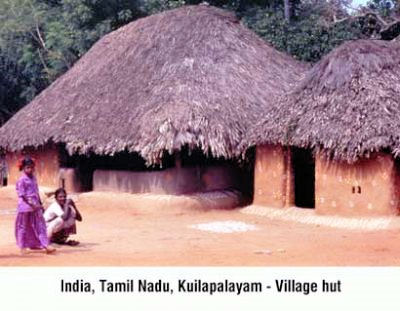

Abb.: Haus, Kilapalayam, Tamil Nadu, Indien

[Bildquelle: AEI]

Abb.: Haus, Rajasthan, Indien

[Bildquelle: judepics. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/judepics/3244639411/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-13. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennenung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Minarett, 27 m hoch, Agadez, Niger

[Bildquelle: Imcari. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/imcari/2256611525/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-13.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Sana'a (صنعاء) , Jemen: Lehmgebäude

in Adobe- und Schichttechnik

[Bildquelle: eesti. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/eesti/350141599/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-06-13. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Festung Masmak (Qasr al-Masmak قصر المصمك), erbaut 1865, Riad (

الرياض ), Saudi-Arabien

[Bildquelle: jwinfred. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jimmysmith/266937192/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-06-13. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Cob-Gebäude, Pazifische Nordwestküste, Kanada

[Bildquelle: Gerry Thomasen / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Verzierung einer Cob-Wand

[Bildquelle: Josh Larios / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Eine Sonderform des geschichteten Lehms sind die Dünner Lehmbrote:

"Das Dünner-Lehmbrote-Verfahren ist eine leicht erlernbare Lehmbautechnik, mit der kapital- und materialsparend, jedoch mit erheblichem Personalaufwand, Häuser errichtet werden können. Dieses Verfahren wird auch „Kraftsches Verfahren“, genannt nach dem Missionar Kraft, der das Verfahren nach einer Einladung von Gustav von Bodelschwingh in Dünne vorführte. In der Zeit nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg gab es weder Kapital noch Material zum Wiederaufbau der Häuser der ärmeren Bevölkerung. Lehm jedoch war in ausreichendem Umfang vorhanden und konnte als Baustoff genutzt werden. Die Technik ist leicht zu erlernen, und es gab viele Arbeiter, die anpacken konnten.

Im Jahre 1923 errichtete Pastor Gustav von Bodelschwingh in seiner Heimatgemeinde Dünne (Kreis Herford) zunächst sein eigenes Haus mit Wänden aus „Lehmbroten“, eine Technik, die er als Missionar in Ostafrika kennengelernt hatte. Bis 1949 wurden dann mehr als 300 Siedlungshäuser in dieser Bauweise fertiggestellt.

Die Technik stammt ursprünglich aus der Slowakei und dem Jemen. Ihr Vorteil gegenüber der Stampflehm- und der Lehmwellerbau-Technik ist, dass diese wesentlich mehr Kraftaufwand und Fachkenntnisse erfordern.

In der Lehmbrot-Technik erfolgt die Errichtung und Deckung des Daches zunächst auf Rundholzstützen, dann werden darunter die Außen- und Innenwände aus Lehmbroten aufgeschichtet. Die Lehmbrote (etwa Ziegelstein-Größe) werden auf Tischen mit Händen oder mittels einer Strangpresse geformt und feucht im Mauerverband ohne Mörtel verlegt. Zur besseren Putzhaftung werden mit Fingern oder Stöcken kleine Löcher gebohrt und auch kleine Steine eingebracht.

Als Wetterschutz dienen zwei Lagen Kalkputz auf den Außenwänden. Wenn die Lehmbrote manuell ohne Strangpresse hergestellt werden, benötigt man keinerlei technische Hilfen, was besonders in ärmeren Regionen ein Vorteil ist.

Abb.: Formung von Adobe-Ziegeln, Rumänien

[Bildquelle: Soare / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Trocknung von Adobe-Ziegeln, Milyanfan (Милянфан),

Kirgisistan

[Bildquelle: Vmenkov / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Adobe is a natural building material made from sand, clay, and water, with some kind of fibrous or organic material (sticks, straw, dung), which is shaped into bricks using frames and dried in the sun. It is similar to cob and mudbrick. Adobe structures are extremely durable and account for some of the oldest extant buildings on the planet. In hot climates, compared to wooden buildings, adobe buildings offer significant advantages due to their greater thermal mass, but they are known to be particularly susceptible to seismic damage in an event such as an earthquake.citation needed] Buildings made of sun-dried earth are common in the Middle East, North Africa, South America, southwestern North America, and in Spain (usually in the Mudéjar style). Adobe had been in use by indigenous peoples of the Americas in the Southwestern United States, Mesoamerica, and the Andean region of South America for several thousand years, although often substantial amounts of stone are used in the walls of Pueblo buildings.1] (Also, the Pueblo people built their adobe structures with handfuls or basketfuls of adobe, until the Spanish introduced them to the making of bricks.) Adobe brickmaking was used in Spain already in the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age, from the eighth century B.C. on. Chazelles-Gazzal 1997:49-57] Its wide use can be attributed to its simplicity of design and make, and the cheapness thereby in creating it.2]

A distinction is sometimes made between the smaller adobes, which are about the size of ordinary baked bricks, and the larger adobines, some of which are as much as from one to two yards (2 m) long

EtymologyThe word adobe (pronounced /əˈdoʊbiː/) has come to us over some 4000 years with little change in either pronunciation or meaning: the word can be traced from the Middle Egyptian (c. 2000 BC) word dj-b-t "mud i.e., sun-dried] brick." As Middle Egyptian evolved into Late Egyptian, Demotic, and finally Coptic (c. 600 BC), dj-b-t became tobe "mud] brick." This evolved into Arabic al-tub (الطّوب al "the" + tub "brick") "mud] brick," which was assimilated into Old Spanish as adobe aˈdobe], still with the meaning "mud brick." English borrowed the word from Spanish in the early 18th century.

In more modern English usage, the term "adobe" has come to include a style of architecture that is popular in the desert climates of North America, especially in New Mexico. (Compare with stucco).