Kompiliert von Alois Payer

Zitierweise | cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Bambus als Material. -- 3. Verarbeitung. -- (Architektur für die Tropen). -- Fassung vom 2010-01-10. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/tropenarchitektur/troparch033.htm

Erstmals veröffentlicht: 2009-10-14

Überarbeitungen: 2010-01-10 [Verbesserungen]

©opyright: Creative Commons Licence (by, no commercial use) (für Zitate und Abbildungen gelten die dort jeweils genannten Bedingungen)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilungen Architektur und Entwicklungsländerstudien von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

น้ำชา gewidmet

|

Arquitectura cultivable Grow your own house

|

ไม่เห็นน้ำอย่าเพ้อตัดกระบอก - Don't cut bamboo without

first checking for thorns

Wat Phra That Phanom (วัดพระธาตุพนมวรมหาวิหาร), Provinz Nakhon Phanom

(นครพนม),

Nordosttthailand (อีสาน).

[Bildquelle: Pawyi Lee / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Diese Kompilation will nur Denkanstöße geben. Für den baumeisterlichen Umgang mit Bambus muss die angegebene Literatur sowie die Erfahrung von Fachleuten herangezogen werden.

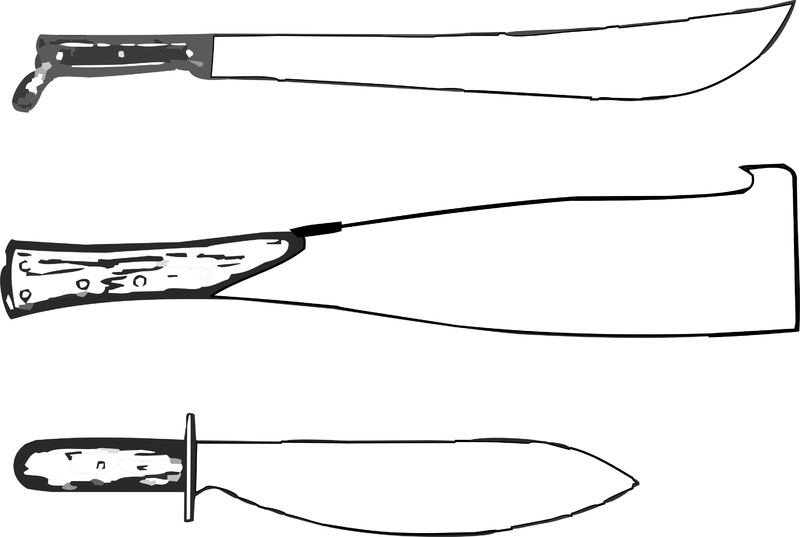

Abb.: "Commonly used tools for working with bamboo. ",

Buglas Bamboo Institute, Duamguete, Philippinen

[Bildquelle: suvajack. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/suvajack/1618565866/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-09-14. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Die Machete ist das wichtigste Bearbeitungswerkzeug für Bambus

[Bildquelle: Ehrenburg / Wikipedia. -- Gemeinfrei]

Kurze Zusammenfassung der Bearbeitungsmethoden von Bambus (nach einem Referat an der RWTH Aachen von einem nicht genannten Autor):

Spalten Durch die axiale Faserausrichtung lässt sich das Bambusrohr schnell und sauber mit einem Keil spalten. Bei der Rohrspaltung lassen sich mit einem Messerkranz Leisten zu Hälften, Vierteln oder Achteln spalten. Bei der Rohrwandspaltung werden aus diesen Leisten radial und tangential weitere Leisten aufgespalten.

Brechen Wird der Bambus gebrochen so fasert die Bruchstelle auf und ist kaum noch als Baumaterial zu verwenden Schneiden Haumesser und Schneidemesser Sägen Wegen der Härte sind Metallsägen am Besten geeignet. Schnitzen Ornamente und Muster lassen sich mit Messern Einritzen oder Schnitzen. Bohren Stein- und Metallbohrer. Brennbohren : Beim Brennbohren wird mit einer glühenden Aufreibspitze ein sehr genaues und glattes Loch erzeugt. Schleifen : Schleifpapier. Selten gebraucht da die Oberfläche nur bei nachträglicher Bemalung aufgeraut wird. Polieren : Mit heißem Pflanzenwachs erhält man eine glänzende Oberfläche Beizen : Salpetersäure = braun, Eisenvitriol = schwarz, Kupfervitriol = grün, Anflammen = fleckiges Braun Kalt-Biegen Bambus lässt sich durch seine hohe Elastizität gut biegen. Bei größeren Durchmessern und Wandstärken muss das Bambusrohr direkt nach dem Ernten vorgebogen trocknen. Zwängt man den Bambusspross beim Wachsen durch eine kastenförmige Schalung, so erhält man eine quadratische Deformierung des Querschnittes. Konvex gewachsene Bambusrohre werden nach dem Ernten aussortiert und direkt für entsprechend gebogene Bauteile verwendet.

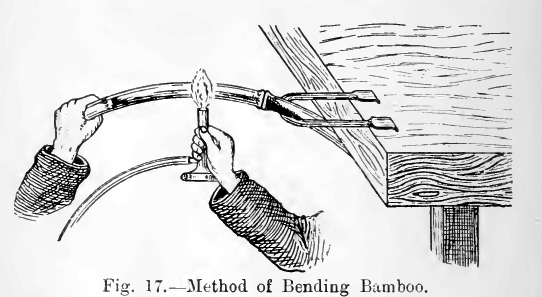

Warm-Biegen Erhitzt man ein Bambuswerkstück mit einem Brenner oder über einer Feuerglut auf 150 °C , so ist es plastisch verformbar. Kühlt das Werkstück ab, behält es seine neue Form.

Quelle der Tabelle: http://bambus.rwth-aachen.de/de/index.html. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-23 (Autor dort nicht genannt).

"PREPARING BAMBOO

Splitting Bamboo

To prepare bamboo for use in construction, the culms (stems) must be carefully split.

Tools and Materials

- Iron or hardwood bars, 2.5cm (1") thick

- Ax

- Steel wedges

- Wooden posts

- Splitting knives (Figure 4)

Figure 4Several devices can be used for splitting culms. When bamboo is split the edges of the bamboo strips can be razor-sharp; they should be handled carefully.

Splitting Small Culms

Small culms can be split to make withes (strips) for weaving and lashing:

- Use a splitting knife with a short handle and broad blade to make four cuts, at equal distances from each other, in the upper end of the culm (Figure 2).

Figure 2

- Split the culm the rest of the way by driving a hardwood cross along the cuts (Figure 3).

Figure 3

- Using a long-handled knife (see Figure 4), cut each strip in half (see Figure 5).

Figure 4

Figure 5A strip of bamboo can be held on the blade to make it thicker and speed up the work.

Use the same knife to split the soft, pithy inner strip from the hard outer strip (see Figure 6). The inner strip is usually discarded.

Figure 6

Build a cross of iron or hardwood bars about 2.5cm (1") thick, and place it on firmly set posts about 10cm (4") thick and 90cm (3") high (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

At the top end of the culm, use an ax to make two pairs of breaches at right angles to each other (see Figure 7).

Hold the breaches open with steel wedges placed a short distance from the end of the culm, until the culm is on the cross as shown in Figure 7.

Push and pull the culm until the cross splits the whole culm.

To split the culms again after they are split into four strips, use a simple steel wedge mounted on a post or block of wood (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

Paired wedges solidly mounted on a block or heavy bench can be used to split strips into three narrower strips (see Figure 9).

Figure 9Bamboo Preservation

Most bamboos are subject to attack by rot fungi and wood-eating insects. Bamboos with higher moisture and starch content seem to be more prone to attack, and insect pests may be more of a problem in some seasons than others. So bamboo should be cut if possible in the bugs' "off-season." There are many methods for making bamboo more resistant to attack. A simple method that combines proper curing and the use of a pesticide (insecticide and/or fungicide) is described here.

If bamboo is to be used to hold food or water, the only treatment recommended is immersion of green bamboo in a borax-boric acid solution (see Bamboo Piping).

Tools and Materials

Machete and hacksaw for felling and trimming bamboo culms

Pesticide-choice depends on the insect or fungus pests that are prevalent in your area. Consult your local extension agent or farmers in the neighborhood about the type and its use. Follow directions carefully.

Talc-to mix with dry pesticide according to package instructions. If talc is not available, other dry dusty materials such as finely powdered dried clay is used. Dusting bag (made from cloth with an open weave)

Bamboo should not be cut before it is mature. This is usually the end of the third season. Freshly-cut bamboo culms should be dried for 4 to 8 weeks before being used in building.

A clump-curing process tested by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Federal Experiment Station in Puerto Rico helps to reduce attack by insects and rot fungi. The steps are:

Cut the bamboo off at the base, but keep it upright in the clump.

Dust the fresh-cut lower end of the culm at once by patting it with a dusting bag filled with the pesticide-talc mixture. An alternative method of dusting is to dip the ends of the culms into a tray containing the mixture.

To keep the bamboo from being stained or rotted by fungi, raise each culm off the ground by putting a block of stone, brick, or wood under it.

Leave the culms in this position for 4 to 8 weeks, depending on whether the weather is dry or damp.

The culms should be as dry as possible before being placed near buildings, where wood eating insects usually are.

When the culms have dried as much as conditions will permit, take them down and trim them. Dust all cut surfaces immediately with the pesticide-talc mixture.

Finish the seasoning in a well-aired shelter where the culms are not exposed to rain and dew. Rain will stain the culms when they become dry.

This method will prevent damage by wood-eating insects while the culms are drying.

If the bamboo is to be stored for a long time, stacks and storage shelves should be sprayed every six months with the appropriate pesticide mixed in water or light oil. Local conditions may shorten or lengthen the time between sprayings.

In both storage and use, bamboo culms are best preserved when they are protected against rain in a well-ventilated place where they do not touch the ground.

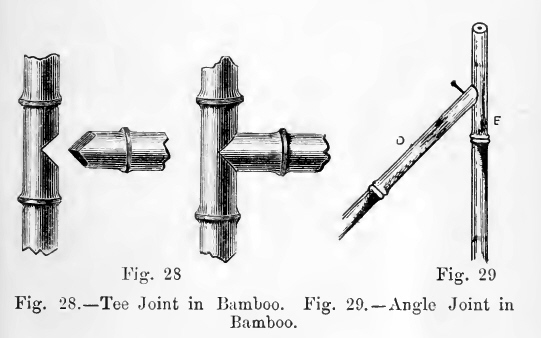

BAMBOO JOINTS

A number of methods of joining bamboo for making implements or for construction are shown in Figures 10 and 11.

Figure 10

Figure 11

Tools and Materials

Bamboo

Lashing material: cord or wire

Machete, hacksaw, knife, drill, and other bamboo working tools

Bamboo is useful for heavy construction because it is strong for its weight. This is because it is hollow with the strongest fibers on the outside where they give the greatest strength and produce a hard attractive surface. Bamboo has solid diaphragms across each joint or node, which prevent buckling and allow the bamboo to bend considerably before breaking.

Any cut in the bamboo, such as a notch or mortise, weakens it; therefore, mortise and tendon joints should not be used with bamboo. However, notches or saddle-like cuts can be made at the upper ends of posts which hold cross pieces (see Figure 10, C an D).

Bamboo parts are usually lashed together because nails will split most culms. The withes (strips) for lashing are often split from bamboo and sometimes from rattan. When all local bamboo yields brittle withes, lashing must be done with bark, vines or galvanized iron wire.

In bending bamboo--for example, for the "Double Butt Bent Joint" in Figure 11 you can help to keep the bamboo from splitting by boiling or steaming it and bending it while it is hot.

Local artisans often know the best species of bamboo and they have frequently worked out practical methods for making joints.BAMBOO BOARDS

Bamboo culms can be split and flattened to form boards for use in sheathing, walls, or floors.

Tools and Materials

- Machete

- Ax--lightweight, with a wedge-shaped head

- Spud--a long-handled shovel-like implement with a broad blade set at an angle to work parallel to the surface of the board.

- Large bamboo culms

Not all of the tools listed above are necessary, but they speed up the work when a large quantity is being produced.

- Remove the thick-walled lower part of the culm.

- Use an ax with a well-greased blade to split each node of the culm in several places (see Figure 12). This should be done carefully to avoid injuring one's feet.

Figure 12

- Spread the culm wide open with one long split.

- Remove the pith at the joints with a machete, adz, or spud (see Figure 13).

Figure 13

- Store the boards as shown in Figure 14.

Figure 14BAMBOO WALLS, PARTITIONS, AND CEILINGS

Bamboo buildings can be built to meet a variety of requirements for strength, light, ventilation, and protection against wind and rain. A few of the methods of building with bamboo are described here.

The parts of a building that are not usually made from bamboo are the foundation and the frame.

Both split and unsplit bamboo culms are used in building. They can be used either horizontally or vertically. Culms exposed to the weather, however, will last longer if they are vertical because they will dry better after rain.

Tools and Materials

- Local bamboos

- Bamboo-working tools, such as machete, hacksaw, chisel, drill

- Lashing material: wire or cord

- Nails

- Barbed wire

- Plaster or stucco

Walls

A method commonly used in Ecuador for making walls is to lash wide bamboo strips or thin bamboo culms, horizontally and at close intervals, to both sides of hardwood or bamboo uprights. The spaces between the strips or culms are filled with mud alone or with mud and stones.

In Peru, flexible bamboo strips are woven together and then plastered on one or both sides with mud.

An attractive but weaker wall can be built by using bamboo boards, stretched laterally as they are attached, as a base for plaster or stucco. Barbed wire can be nailed to the surface to provide a better bond for the stucco. The exterior can be made very attractive by whitening it with lime or cement. <see figure 15>

Figure 15Partitions

Partitions are usually much lighter and weaker than walls. Often they are no more than a matting woven from thin bamboo strips and held in place by a light framework of bamboo poles. Bamboo matting is often used to finish ceilings and both interior and exterior walls; bamboos with thin-walled, tough culms are usually used for this.

Ceilings

Ceilings can be built with small, unsplit culms placed close together or with a lattice of lath-like strips split from larger culms. There should be some space to let smoke from kitchen fires escape.

Source:

McClure, F.A. Bamboo as a Building Material. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Agricultural Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture, 1953; reprinted 1963 by Office of International Housing, Department of Housing and Urban Development. [Online: http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/34/73/06.pdf. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-22 ]"[Quelle: Bamboo Construction. -- http://www.fastonline.org/CD3WD_40/VITA/BAMBOO/EN/BAMBOO.HTM. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-22]

Hans Spörry beschreibt 1903 die damals in Japan gebräuchlichen Bearbeitungsmethoden von Bambus:

"Bearbeitungsmethoden. Kat. Nr. 21-82.

Um Bambus zu den mannigfaltigen Gebrauchsgegenständen zu verarbeiten, wird er

zerschnitten,

gespalten,

gebogen,

gekrümmt,

aufgeschnitten und platt gedrückt,

geschnitzt,

gebeizt,

gebrannt,

geätzt,

geglättet,

glänzend poliert und

lackiert.

Abb.: Bambus spalten[Bildquelle: mann. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/chairmann/BambooWorkshop#5205133961163595138. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-30. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Für diese Behandlungen besitzt der Japaner eine besondere Geschicklichkeit, sie sind „seine Spezialität". Gewisse Effekte und Eigenschaften an den fertigen Produkten weiß er durch das einfache Mittel mehrmaliger, unterbrochener Behandlung, durch gründliches Trocknen und langes Ruhen lassen, hervorzubringen, was alles das Ergebnis ewigen Probierens, genauester Beobachtung und großer Geduld ist, Eigenschaften, über die der Japaner in hohem Maße verfügt. Seine Hilfsmittel sind primitiv (man betrachte die Werkzeuge Nr. 21 —73), um so größer sind darum die Anforderungen an die Geschicklichkeit des Arbeiters. „Übung macht den Meister", das gilt auch in Japan, und jeder Meister schafft hier etwas Eigenartiges.

Der Einblick in eine japanische Bambus-Flechter-, -Schreiner-, oder -Schnitzer-Werkstatt verspricht allerdings bei weitem nicht das, was man aus ihr hervorgehen sieht. Natürlich ist alles Hausindustrie. In Shizuoka [静岡] besuchte ich den Arbeiter, der Nr. 810 dieser Sammlung verfertigte. Ich wurde wohl eine halbe Stunde weit in eine ärmliche Vorstadt, mit vernachlässigten, halb baufälligen Häusern geführt, wo schließlich vor einem solchen Halt gemacht und guten Tag „kon-nichi-wa" [今日は], gerufen wurde, worauf die übliche Einladung erfolgte, einzutreten. Die meisten Häuser in den zusammengebauten Straßen sind von schmaler Front (nur Tür und Erkerfenster) aber ziemlich tief. Von der Haus-(schieb)-türe führte ein offener Gang, 1—1½ Meter breit, mit bloßem Erdboden, durch die ganze Hauslänge zur Hintertüre (diese in Angeln hängend) in den kleinen, vernachlässigten Garten oder Hof hinaus. In dieser Passage, wenn kein besserer Platz frei ist, steht auch der aus Lehm geformte Kochherd, und zur Linken der ganzen Länge nach, zirka 2' über dem Boden auf einer Balken- und Bretterunterlage mit tatami [畳] belegt, sind die Wohn- und Arbeitsräume, das heißt die vorderen 7—8 „tatami" sind Wohn-, Ess- und Schlafzimmer für die Familie, und die hinteren 6—8 „tatami", mit Aussicht in den Hof hinaus, sind die Werkstatt. So genau ist die Absonderung aber nicht innegehalten, sondern es liegt so ziemlich alles durcheinander, was Werkzeuge, Haushaltungs-Utensilien und dergleichen sind. Eine Zimmerdecke ist nicht vorhanden, sondern nur das bloße Dach (Bretter und Schindeln). Im Winter werden die bekannten Papiertüren eingeschoben, um die Wärme einigermaßen zusammenzuhalten, im Sommer sind sie alle weg und das ganze Innere ein Raum. Sehr appetitlich sieht es nicht aus, alles verstaubt und verraucht, [S. 37] schmutzig und schmierig. Und der Arbeiter? Nun, der hockt eben auf den „tatami", ein schon älterer Mann, mit „hi-bachi" [火鉢 und Tabakpfeife neben sich und spaltet und schabt, glättet und sortiert die Bambusstäbchen, aus denen er die meisterhaft schönen Körbchen herstellt. Inmitten seiner zahlreichen Schar schmutziger Kinder ist er munter und vergnügt und immer zu einem „hanashi" [はなし] (Gespräch), aufgelegt. Ich habe lange bei dem Manne gesessen und mir die Geheimnisse seiner Kunst erklären lassen, soweit wir uns gegenseitig verständlich machen konnten ; er sandte mir einige Monate später die Geflechtmuster (Nr. 810), die ich ihm bestellt hatte. Diese wenigen Proben bester, neuer Arbeit bezeugen genügsam, dass die Bambusflechterei nicht im Rückgange begriffen, wenn wir auch gewisse eigentümliche Formen und Verwendungen Alt -Japans nicht mehr antreffen.

Fig. 7 KorbflechterDie nachstehend angegebenen Verfahren stammen aus fachmännischen Quellen, dürften aber dennoch nicht bis in alle Details vollständig und genau sein, indem der japanische Bambuskünstler seine Berufsgeheimnisse ebenso gut zu verschweigen versteht wie andere Leute.

Für gewöhnliche Zwecke, z. B. Korbwaren und dergleichen für den alltäglichen Gebrauch, werden die Bambusrohre mit Strohwischen, Reis- und Weizenspreu, Lumpen und Wasser gefegt und mit Messern geschabt, um sie von der äußersten grünen, etwas fettigen Haut zu befreien.

Für feinere Zwecke wird das gelagerte Holz (siehe S. 19) mit Rochenhaut „same no kawa", Schachtelhalm „tokusa" [トクサ科] und mit „muku no ha" [ムク ノ ハ], Blättern der Aphananthe aspera Pursh, Familie der Ulmengewächse sorgfältig glatt gerieben, also ein abgestuftes Verfahren, wie bei uns vermittelst gröberem und feinerem Glaspapier (Nr. 74-77).

Beugen und Krümmen. Dünnere, d. h. bis ca. zwei fingerdicke Bambusrohre können beliebig gebogen werden. Die geeigneten Stücke werden ausgewählt, an der Biegestelle mit Öl oder Fett (geringstem Ochsenfett? „het") beschmiert und über einem Kohlenfeuer gedreht. Durch die Hitze wird das Rohr bald biegsam und muss dann schnell in die gewünschte Form zurechtgedrückt werden. Ganz dünne Rohre sind auch ohne Anwendung von Fett biegsam. Auf diese Art werden Fischruten, Schirmstöcke, Zaunstecken u. s. w. von bloßer Hand, oder vermittelst eines Richtholzes (Nr. 47—49) über dem Feuerbecken gerade gedrückt; sie erstarren, sowie sie [S. 38] erkalten. Stärkere Rohre werden mit gespannten Stricken, oder durch Einklemmen zwischen in Bretter gesteckte starke Holznägel geformt, die Nägel können so gestellt werden, dass beliebige Figuren herauskommen, allzu scharfe Krümmungen sind immerhin bei diesem Verfahren nicht möglich. Bei dicken Rohren wird durch Sägeeinschnitte nachgeholfen. Das Rohr muss bis zum vollständigen Erkalten in der Form gelassen werden. Für komplizierte Krümmungen von kleinen Stücken (gespaltener Rohre) soll folgendes Verfahren angewendet werden. In einer Lösung von:

100 momme [匁] = 375 Gramm Eisenvitriol „roha"

1 sho [升] = 1,8 Liter Salz „shio" [塩]

1 sho [升] 5 go [合] = 2,7 Liter Wasser „mizu" [水]welche in einem Kessel siedend erhalten wird, werden die Stücke an der Biegestelle eingetaucht, bis sie ganz durchwärmt sind und dann in jede beliebige Form gebogen und gedreht werden können; bis zum Erkalten (was bei so kleinen Stücken rasch eintritt) müssen sie aber festgehalten werden. Die Flüssigkeit soll nicht in das Holz eindringen und demselben auch nicht schaden. Für scharfe Biegungen soll dieses Verfahren deshalb das einzig mögliche sein, weil durch das Sieden das Holz rundum gleichmäßig erwärmt werde, also keine kalten (spröden) Stellen sich dem Biegen widersetzen oder brechen. Beim bloßen Wärmen am Feuer könne diese gleichmäßige Erhitzung nicht erzielt werden. Dünne Lamellen können durch bloßes Wärmen spiralförmig gedreht werden. Zum Biegen nach obigen beiden Methoden ist erforderlich, dass der Bambus frisch, oder nur seit kurzer Zeit geschnitten sei, mehrere Monate lang gelagerte, hartgewordene Rohre eignen sich nicht mehr dazu.

Abb.: Bambus krümmen[Bildquelle: mann. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/chairmann/BambooWorkshop#5205135786524696706 . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-30. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Plätten, d. h. Rohre brettartig ausbiegen. Auch hiefür kommt nur frisch (in der richtigen Jahreszeit und im richtigen Alter) gefällter Bambus zur Verwendung. Das Rohrstück wird der Länge nach aufgesägt, die „kawa" Haut, Rinde gleichmäßig abgehobelt oder abgeschabt, die Außenseite mit 'het' (bedeutet „abura", geringstes Fett irgendwelcher Natur) eingeschmiert, das Stück über ein Kohlenfeuer gelegt, und wenn es recht erhitzt ist, nach rechts und links auseinander gebogen, dann zwischen zwei Bretter gepresst, bis es erkaltet und erstarrt ist. Das genügt für dünnwandige Rohre, dickere müssen in siedendem Fett durchwärmt werden, nachdem sie wie oben geschält wurden; auch „het" soll nicht in das Holz eindringen. Die Innenseite des Rohres wird also zur Oberseite des Teebrettes.

Abb.: Plätten, Sleman, Java, Indonesien[Bildquelle: humanitarianbamboo.org. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/humanitarianbamboo/BambooFarmersFieldSchoolInSleman#5292 . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-29. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Schnitzen. Gewöhnlich wird nur gut gelagertes Rohr hiezu benutzt. Feine Schnitzereien werden als Kunststücke geschätzt, weil sie in dem harten Holze besonders schwierig auszuführen sind. Oft werden in die Haut kunstvolle Zeichnungen eingeritzt, wozu gleichfalls eine sichere Künstlerhand erforderlich ist (siehe Nr. 765); die Stichel hiezu sind unter Nr. 52—68 vollzählig vertreten.

Abb.: Bambusschnitzer, Nanjing (南京), China (中国)

[Bildquelle: springm / Markus Spring. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/springm/3056514213/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-13. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]Beizen. Färben. Sauber geglättete Bambuslamellen und Stäbchen für feine Geflechtarbeiten werden mit dem Saft der „kuchi-nashi" (Beeren der Gardenia florida) gelb gebeizt. Diese Früchte enthalten einen mit dem Safran [S. 39] (Crocin) verwandten gelben Farbstoff (Kat. Nr. 78). Gebeizt wird auch mit Salpetersäure „shosan", und das Holz nachher mit Lappen tüchtig gerieben. Kommt eine Inschrift oder eine Zeichnung darauf, so wird dieselbe vor dem Bestreichen des Holzes mit „shosan" vermittelst Kreidepulver „choku" aufgemalt. Schwarzgefärbt wird mit Eisenvitriol „roha", und grün mit Kupfervitriol „ryusan-do" oder „tampan". Die glänzend braunen, sogenannten „suzu-dake", sind meistens angerauchte Rohre aus den Dachböden und Dachsparren der Bauernhäuser (s. S. 43).

Brennen. (Nr. 668.) Diese Behandlung wird nicht häufig angetroffen und scheint bloßer Liebhaberei zu entspringen. Das Verfahren ist das denkbar einfachste, vermittelst glühender Drähte.

Ätzen. Während die harte Oberhaut des Bambusrohres die feinsten Schnitzereien treu bewahrt, eignet sich dessen Innenseite zu einer noch auffälligeren Behandlung. Ganz nach Art des Radierens können vermittelst Salpetersäure und weißem Wachs „haku-ro" (Nr. 79) als Deckung, allerlei Bilder eingeätzt werden (Nr. 138—139), wobei die Bambushaut etwas getrieben zu werden scheint, etwa wie Lithographiesteine beim Körnen.

Polieren geschieht durch Einreiben des Gegenstandes mit erwärmtem weißem Pflanzenwachs und tüchtigem Frottieren mit baumwollenen und seidenen Lappen, wodurch ein dauerhafter Glanz erzielt wird. Statt Wachs werden auch in eine Lackart „hana-urushi" (Nr. 80—81) getauchte Tuchlappen verwendet.

Das Durchbrechen der Knotenwände „fushi" in den zu Wasserleitungen bestimmten Bambusrohren geschieht vermittelst 4½ Meter langen Eisenstangen, an die zweierlei Kolben „fushi-nuki" oder „fushi-hari" angeschraubt werden. Zuerst ein solcher mit konischer Spitze (Fig. 8) (bis zur Spitze 6,2 cm. lang, an der Basis 3,3 cm. Durchmesser) zum Durchschlagen der Wände, dann einer mit vorne trichterförmiger Vertiefung und scharfkantigem Rand, zum Entfernen der Knotenwand -Ansätze im Innern des Rohres. Indem die Stange von beiden Seiten durchgeschleudert wird, können 30—40' lange Rohre durchbrochen werden.

Abb.: Kolben "fushi-nuki"[Quelle: Spörry, Hans <1859-1925> ; Schröter, Carl <1855-1939>: Die Verwendung des Bambus in Japan und Katalog der Spörry'schen Bambussammlung / von Hans Spörry. Mit einer botanischen Einleitung / von C. Schröter. -- Zürich : Zürcher & Furrer, 1903. -- 198 S. : 8 Tafeln im Anhang und etwa 100 Textbilder. -- (Geographisch-Ethnographische Gesellschaft Zürich). -- S. - 36 - 39. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/dieverwendungdes00sp. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-20]

Abb.: Zuschneiden von Bambus-Setzlingen, Philippinen

[Bildquelle: Jeff_Werner. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jeffwerner/531466724/in/set-72157600151000055/.

-- Zugriff am 2009-09-15. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

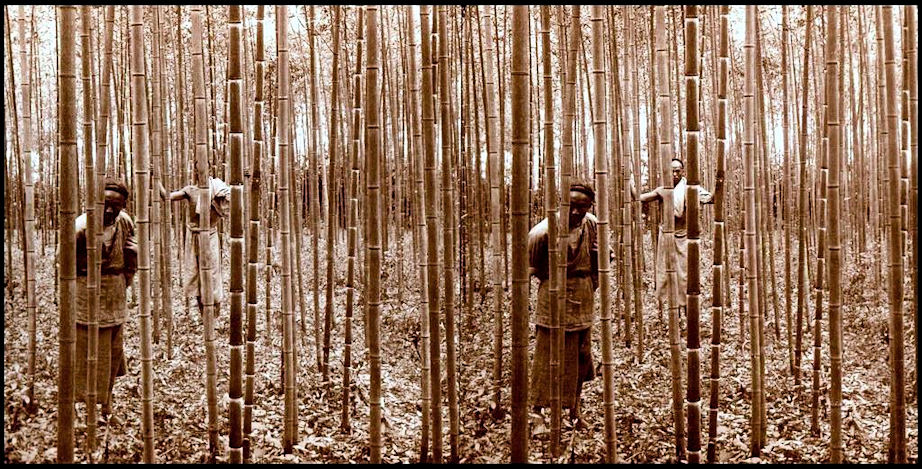

Abb.: Bambuskultur, Nanjing (南京),

China (中国),

um 1900

[Bildquelle: James Ricalton. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/24443965@N08/3484008662/. -- Zugriff am

2009-10-08. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

David Fairchild gab 1903 folgende Darstellung über die Bewirtschaftung von Bambuswäldern in Japan:

"JAPANESE MANAGEMENT OF BAMBOO GROVES. One of the best posted bamboo growers in Japan informed the writer that twenty years ago he did not know that his groves, which were then in a neglected state, had any money value, but that to-day those parts of his farm on which the groves are situated are its most valuable portions. The attention which he bestows upon them now is very inexpensive, but almost as careful as that given to any other of his crops. The following forest methods are largely those which Mr. Tsuboi described as, from his experience, the best. These are applicable with slight variations to the three principal timber bamboos in Japan, and pertain in a general way to the culture of the ornamental species.

Plate III: Bamboo forests. Fig. 1. A well-kept forest of Phyllostachys quilioi growing on poor soil filled with gravel. Weeding has not been as recently done as in that part of the forest shown in PI. II. The two photographs from which these plates were prepared were taken from points not 20 yards apart in the forest of Mr. Isuke Tsuboi, of Kusafuka. Photographed by Yendo. Fig. 2. A badly kept forest of timber bamboo (Phyllostachys quilioi ) growing on good soil adjacent to the well-kept forest shown in PI. II. This shows the effect of not weeding, thinning out, or fertilizing. Photographed by Yendo.

Plate II: "A well-kept forest of Phyllostachys quilioi growing on good soil, showing an open drainage ditch in foreground and the thick mulch of leaves and straw which cover the ground. Age probably over 50 years. Photographed by Yendo.", Japan

The land chosen for a bamboo grove should be dug over to a depth of 1½ feet the autumn previous to being planted, and, if a heavy soil, should have worked into it a good quantity of trash from the stable. The plants should be set out at an equal distance from each other at the rate of about 300 to an acre, or 12 feet apart each way. If the soil is a dry one, the ball of earth and roots should be planted below the surface of the soil, but if a wet one a mound should be made and the plants set in the upper portion of it. After planting it is important, as already remarked, that the soil between the plants should be given a heavy mulch of straw, under which is a layer of cow manure. This mulch should be 7uaintained during the entire year. In the beginning the roots should be supplied with an abundance of water and in the autumn should be given plenty of rotted manure. If some of the plants die, they should be replaced by others so as to maintain as complete a stand as possible. It is essential as the new shoots spring up that the ground at their bases should be shaded by the foliage. The semiobscurity of a Japanese grove is not only its greatest charm, but one of the necessary factors of its growth. The sooner the ground can be shaded by the plants the better.

For the first three years at least all the shoots that appear should be allowed to mature, but after the grove is once well established only the largest shoots should be permitted to grow, the others being cut out as soon as they appear above the ground. This thinning process throws the strength of the plants into a comparatively few large culms, and gradually increases the height and strength of the forest.

In regions where the snows are so heavy that they break down the plants the practice of bringing the tops of several culms together and fastening them with rope is sometimes followed. The wigwam-like masses formed in this way are able to support without injury the weight of snow.

No culm should be cut for timber purposes until it is at least four years old, as before this time the wood is not mature. On the other [S. 22] hand, if left standing too long the wood becomes too brittle and loses in value, and the forest besides is benefited by the cutting out of the four-year-old stems. The crop of new shoots is larger. This thinning-out process should be so done that as few gaps as possible are made in the forest and the semiobscuritv below the mass of foliage is maintained.

The crop of new shoots varies in size every alternate year. A poor crop would mean 6 to 7 per cent of new shoots and a good crop 12 to 14 per cent. As there are commonly 10,000 culms in a hectare (or 4,545 in an acre) of properly planted grove ten to fifteen years old, this would mean the production of 600 to 700 culms per hectare for a light crop and 1,200 to 1,400 for a heavy one. These figures werevery kindly furnished the writer by Dr. T. Shiga, chief of the imperial forest management in Tokyo.

The experience of Mr. Tsuboi has been that some kinds of forest trees if standing in a grove prevent the growth of the bamboos near them. Oaks and chestnuts, he declares, are especially objectionable in this respect, while persimmons do not seem to affect in the least the production of new bamboo shoots. The effect of weeds in a forest is undesirable, and although comparatively few species are able to live in such a deep shade these should be dug out as from any cultivated field. Attention to these various details makes a great difference in the amount and quality of timber produced. A grove is not to be looked upon as merely a thicket and left to take care of itself, but as a plant culture which requires attention. Plates II and III show the effects of different methods of treating parts of the same grove.

One important element in the culture of this peculiar timber plant is the fact that a whole forest may bloom and die in a single season, and that it is not possible—as yet—to tell beforehand when this blooming will take place. The intervals between these periods are, however, so long that they are not taken into consideration by the Japanese farmer when he buys a bamboo grove. Little accurate information is obtainable regarding the length of life of the various Japanese species. but Phyllostachys humilis has the reputation in Japan of blooming oftener than either Phyllostachys quilioi, Phyllostachys mitis, or Phyllostachys nigra, the other three important timber species. A small grove near Kawasaki which bloomed this season (1902) was reported by the owner to have once bloomed about sixty years before. As there always remain in the field a number of living rhizomes, after the death of the forest, these renew the latter in a few years, so that the actual loss to the owner does not include the cost of replanting. This is the case at least with the Japanese bamboos. As culms which have bloomed are poor in quality, the practice is followed of cutting them as soon as possible after they show signs of blooming. [S. 23]

In Japan, where bamboos and rice arc often grown in adjoining plats of ground, some trouble is experienced from the underground stems spreading into the neighboring fields. To prevent this a ditch 2 feet wide and as many feet deep is dug about the grove and kept open by several rediggings during the year. This method is said to be a satisfactory one. It is a difficult matter, however, after a field has once been planted to bamboos, to clear it satisfactorily for other crops, for there is a mass of these tough rhizomes that are very difficult to dig out.

The harvesting of bamboo poles is not done before August, as culms cut earlier than this date are likely to be attacked by insects, not having had time to sufficiently harden. A Kyoto grower of black bamboos remarked that the Kobe exporters, by insisting on having their bamboos for export cut earlier than this date, had seriously injured the foreign demand, as the quality of the wood was much injured by this early harvest.

A saw is often used in cutting the shoots, by making cuts on opposite sides of it near the base. When cut, the poles are classified, tied into bundles, and stacked like hop or bean poles to dry. In the lumber yards of Japan these stacked poles of bamboo form a prominent feature."

[Quelle: Fairchild, David <1869-1954>: Japanese bamboos and their introduction into America. -- Washington : Govt. print. off., 1903. -- 36 S. : VIII Tafeln. -- 23 cm. -- S. 21 - 23. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/japanesebamboost00fair . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-20

Abb.: Bambusernte, Changzhou ( 常州市),

China (中国)

[Bildquelle: Augapfel. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/qilin/2117272521/in/photostream/. -- Zugriff am

2009-10-08. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Da das Ernten von Bambus arbeitsintensiv ist und die Arbeitskräfte dabei sehr verstreut sind, besteht die Gefahr, dass sie Kahlschlag betreiben, wie Jules J. A. Janssen bemerkt:

"A problem with the harvest is that it is very labour intensive and requires an extensive workforce. These people are widely scattered over the forest and cannot be controlled. For casual labour, the only interest is their day's income; the next harvest is beyond [S. 5] their scope. This tends to result in over-cutting within short distances of the road and less or no cutting at longer distances. A reduction of productivity is the result. This will not happen if the cutters are also the owners, i.e. a co-operatively owned bamboo plantation." [Quelle: Janssen, Julius Joseph Antonius <1935 - >: Building with bamboo : a handbook / Jules J.A. Janssen. -- 2nd ed. -- Warwickshire : Intermediate Technology Publications, ©1995. -- 65 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN 1-85339-203-0. -- S. 5f.]

Dabei sollte die Ernte von Bambusstängeln in Plenterbetrieb bzw. als Auflichtung geschehen, wie Dunkelberg fordert:

"Der Kahlhieb mag die gebräuchlichste Hiebmethode sein, aber auf eine sinnvolle 'Bambuswirtschaft' bezogen ist sie unökonomisch. Meist betreiben die Eingeborenen im Landesinneren keine Wiederaufforstung; deshalb sollte der Plenterhieb bevorzugt werden. Bei den weiten Halmabständen monopodialer Spezies ist die Entnahme der Bambusstangen eine typische Plenterung. Bei der Beerntung von horstbildenden Bambusarten trifft eher die Bezeichnung Läuterung oder Auflichtung zu (Hosseus). In 2-4 jähriger Wiederkehr entnimmt der Hieb dem Horst bis zu 30% der reifen Stangen. Die richtige Jahreszeit in den Subtropen wäre Herbst und Winter, in den Tropen die Trockenzeit.

Der Abhieb sollte nicht höher als 30 cm über dem Boden liegen (Hildebrand). Das Fällen geschieht am besten mit dem Haumesser (Machete o.ä.). Wenn abgesägt, dann verfault der zugehörige Wurzelteil nicht, zum Nachteil der neuen Triebe. Das Verfaulen wird beschleunigt, wenn anschließend die Wurzel kreuzweise durchschlagen wird, damit Regen und Sickerwasser besser eindringen können (Hackel).

Der Hieb sollte die Verbindung der verbleibenden Halme untereinander nicht beeinträchtigen. Fehlt im Horst die gegenseitige Stützhilfe, dann neigen sich die Halme, und man erhält künftig nur noch verbogene Stangen. Für die Wahl des Hiebturnus sind die Kenntnisse von der jährlichen Leistungsfähigkeit der Horste unumgänglich. Nach Pearson entfällt auf ca. vier alte Halme ein neuer Halm. Es wäre mehr als vier Jahre nötig, die alten Halme zu ersetzen. Die Leistungsfähigkeit, neue Halme im Horst hervorzubringen, ist artenverschieden (Tab. 28).

Art Ort/Zeit % Bambusa arundinacea Orissa, 1959 10% Bambusa tulda New Forest, 1958 18% Teinostachym dullooa Assam, 1955/6 34% Dendrocalamus hamiltonii Assam, 1955/6 38% Tab. 28: Durchschnittsproduktion an jungen Halmen im Jahr; Angaben in % der alten Halme; nach Mathauda.

Zur Festlegung des Hiebsatzes sollte die mittlere Jahresproduktion der jeweils letzten 15 Jahre berücksichtigt werden; dadurch lässt sich am besten eine nachhaltige Ernte sichern. Mit der ersten Halmernte kann erst dann begonnen werden, wenn der Horst seine volle Hiebreife erlangt hat; das wird nicht vor 6 Jahren nach seiner Begründung sein. Innerhalb der staatlichen Wälder in Indien werden die Horste alle 3-4 Jahre beerntet, und zwar nur die älteren Halme (Prasad). Etwa 10 Stangen sollten stehen bleiben, wobei die Peripherie des Horstes vom Hieb verschont bleiben sollte. Die belassenen Stangen stützen nicht nur die jungen Triebe, sondern erhalten auch die volle Wuchskraft der Rhizome (Hildebrand). Zwei- bis fünfjährige Bambusstangen gelten als geeignetste Bau- und Werkstoffe.

Bei dreijährigem Umlauf ist mit einer Ernte zwischen 3.000 bis 15.000 Halmen/ha zu rechnen, das entspricht einer Trockensubstanz von 7,5 bis 38 t/ha (Hubermann). In Deutschland ist der jährliche Holzeinschlag ebenfalls an die Nachhaltigkeit der Wälder gebunden. Er beträgt nur 3,5 fm/ha, was etwa 1,4 t/ha lufttrockenem Holz entspricht (Bertelsmann)

Nach dem Fällen müssen die Zweige so sorgfältig von den Stangen entfernt werden, daß die Außenhaut des Rohres nicht verletzt wird (Austin). Beim Abschlagen des Astansatzes werden oft breite Rindenstreifen über die nächsten Internodien hin aus der Rohrwand herausgerissen. Der Schutzschild gegen Nässe und Schädlinge ist dann undicht."

[Quelle: Dunkelberg, 1978. -- S. 92]

Abb.: Verschieden zugeschnittene Bambusformate,

Buglas Bamboo Institute, Duamguete, Philippinen

[Bildquelle: suvajack. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/suvajack/1617660201/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-09-14. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Sägen mit der Kreissäge, Indonesien

[Bildquelle: humanitarianbamboo.org. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/humanitarianbamboo/PrefabricationOfCHFSheltersInNUMPUKAN . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-29. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Bambus spalten, Indonesien

[Bildquelle: Gwen Bubbles. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/inbetweens/3723879362/. -- Zugriff am

2009-09-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Bambus-"Rippen", PT bamboo factory, Sibang Kaja, bIndonesien

[Bildquelle: jsigharas. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jsigharas/2131523531/in/set-72157605942819126/

. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-14. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Verbindungen sind möglich

Klebeverbindungen für Bambusstängel sind m. W. noch nicht ausgereift.

Abb.: Lage als Verbund (Boden): Bau einer Kompostier-Toilette, Ubud, Bali,

Indonesien

[Bildquelle: Jeff_Werner. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jeffwerner/1320876720/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-10-09. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

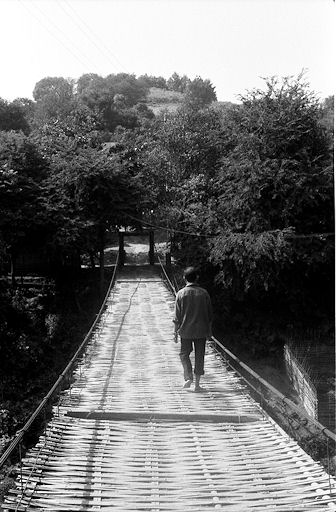

Abb.: Bambusflechtwerk als Brüchenbelag, Sơn La, Vietnam

[Bildquelle: Tom Churchill. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/tomchurchill/346944377/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-10-08. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Bambus-Flechten für Wände, Mingun (မင်းကွန်မြို့),

Myanmar

[Bildquelle: Freddimus. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/fellatemefreddy/449088374/. -- Zugriff am

2009-10-10. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

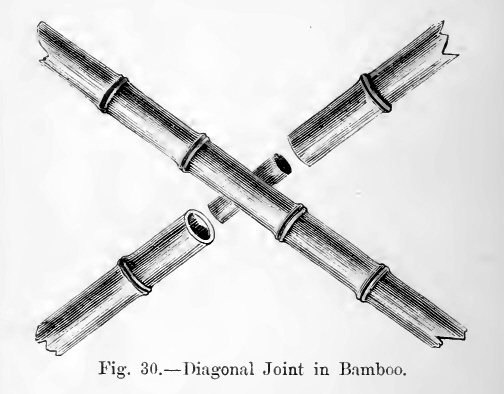

Abb.: Bambusverbindungen

[Bildquelle: Hasluck, Paul N.

(Paul Nooncree) <1854-1931>: Bamboo work. -- [London [u.a.] : Cassell,

1901]. -- 160 S. : Ill. --("Work" handbooks). -- S. 34. -- Online:

http://www.archive.org/details/bambooworkcompri00hasl. -- Zugriff am

2009-09-20]

[Bildquelle: Hasluck, Paul N.

(Paul Nooncree) <1854-1931>: Bamboo work. -- [London [u.a.] : Cassell,

1901]. -- 160 S. : Ill. --("Work" handbooks). -- S. 35. -- Online:

http://www.archive.org/details/bambooworkcompri00hasl. -- Zugriff am

2009-09-20]

[Bildquelle: Hasluck, Paul N. (Paul Nooncree) <1854-1931>: Bamboo work. -- [London [u.a.] : Cassell, 1901]. -- 160 S. : Ill. --("Work" handbooks). -- S. 36. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/bambooworkcompri00hasl. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-20]

Abb.: Verknotung, Bambus-Brücke, Glendurgan Garden, Falmouth, UK

[Bildquelle: Tim Green aka atoach. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/atoach/2800852664/. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-14.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielel Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Einfache Binde-Verbindung

[Bildquelle: humanitarianbamboo.org. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/humanitarianbamboo/DonYangRefugeeCamp29409# . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-28. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Bambusverbindungen, Yogyakarta, Indonesien[Bildquelle: humanitarianbamboo.org. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/humanitarianbamboo/BambooSchoolInSouthernJogjakarta# . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-29. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Bambus-Verbindung (Stuhl), Buglas Bamboo Institute, Duamguete, Philippinen

[Bildquelle: suvajack. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/suvajack/1593732423/ . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-14. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Bambusverbindung, Geländer, Kinkaku-ji (金閣寺), Kyōto (京都市), Japan (日本)

[Bildquelle: Khaz. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/khaz/2656323385/. -- Zugriff am 2009-10-09. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Sicherung von Bambusverbindungen mit Draht

[Bildquelle: humanitarianbamboo.org. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/humanitarianbamboo/OxfamTShelterPictureSoloLPTPOxfam#5333818960563431026 . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-29. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Auch Stahlbänder sowie andere Verbindungsmittel aus Stahl können als Verbindung verwendet werden.

Abb.: Steckelemente für Fahrradkonstruktion, Oregon, USA

[Bildquelle: taisau. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/taisau/1977174376/. -- Zugriff am 2009-10-09.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Steckverbindung

[Bildquelle: kremisimo. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kremisimo/2351099675/in/photostream/ . --

Zugriff am 2009-10-09. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

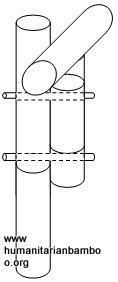

Abb.: Bolzenverbindung

[Bildquelle: humanitarianbamboo.org. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/humanitarianbamboo/BambooCommunityStructureInTembi02# . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-28. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Bolzenverbindung

[Bildquelle: humanitarianbamboo.org. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/humanitarianbamboo/BambooCommunityStructureInTembi02# . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-28. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Schraubverbindung

[Bildquelle: kremisimo. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kremisimo/2351929790/. -- Zugriff am

2009-10-09. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Nageln birgt die Gefahr, dass der Bambus aufspaltet.

"Little equipment is needed to build with bamboo, only simple tools. The manner of joining stalks is simple and secure. Wherever two pieces of bamboo connect, holes are drilled in the internode portion of the stalks. A bolt is pushed through both pieces, and the internodes are filled with mortar. The mortar distributes the load of the bolt through the whole piece of bamboo and prevents it from splitting.

Steel bolts through mortar in internodes"[Quelle: http://www.appropedia.org/CCAT_decomisioned_bamboo_construction. -- Zugriff am 2009-10-12. -- Zeichnung von John Halley. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Man unterscheidet

Abb.: Prinzip der Warm-Biegeverformung von Bambus

[Bildquelle: Hasluck, Paul N.

(Paul Nooncree) <1854-1931>: Bamboo work. -- [London [u.a.] : Cassell,

1901]. -- 160 S. : Ill. --("Work" handbooks). -- S. 28. -- Online:

http://www.archive.org/details/bambooworkcompri00hasl. -- Zugriff am

2009-09-20]

Abb.: Bambus-Armierung für Beton, Mae Sot (แม่สอด),

Thailand (ประเทศไทย)

[Bildquelle: Mrs Hilksom. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/95976276@N00/96578246/ . --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnnenung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Betonarmierung aus Bambus

[Bildquelle: humanitarianbamboo.org. -- http://picasaweb.google.com/humanitarianbamboo/BambooReinforcedConcrete02#5333814982324051682 . -- Zugriff am 2009-09-29. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Gestaltung kann geschehen u.a. durch

Abb.: Angemalter Bambus als Decke

[Bildquelle: chris5aw. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/21629395@N07/3546357410/ . -- Zugriff am

2009-10-08. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Behältnis für Kalk zum Betelkauen, mit Ritzverzierung, Bagobo, Mindanao,

Philippinen

[Quelle: Kroeber, A. L. (Alfred Louis) <1876-1960>: Peoples of the

Philippines. -- New York : [American Museum Press], 1919. -- S. 89.-- Online:

http://www.archive.org/details/peoplesofphilipp00kroeuoft. -- Zugriff am

2009-10-10]

Abb.: Bambusbehälter für Betel, mit Ritzzeichnung, Dayak, Borneo

[Bildquelle: Roth. -- 1896]

Abb.: Detail einer Ritzzeichnung auf Bambusbehälter für Betel, Dayak, Borneo.

Die Ritzung wird durch eingeriebenes rotes Harz (Drachenblut) hervorgehoben

[Bildquelle: Roth. -- 1896]