|

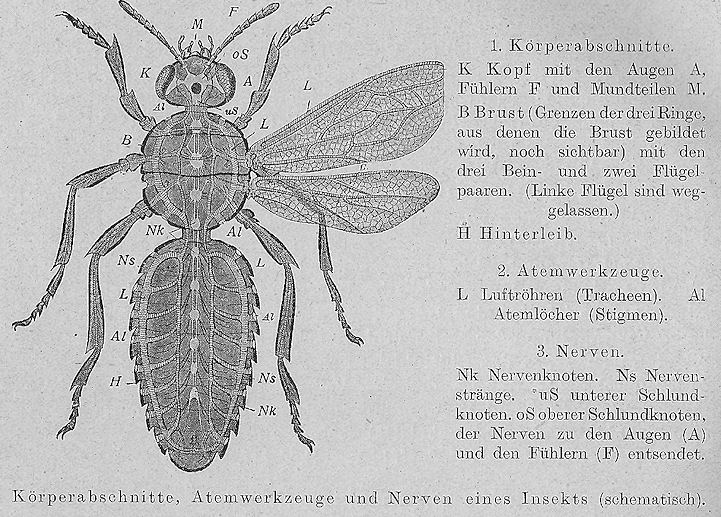

"INDIAN BLOODSUCKING INSECTS.

As we all know, India is a country which has

its full share of those vermin which spend the whole or part

of their lives on the bodies of men and other warm-blooded

animals, and also of those equally annoying insects which

alight upon the body of their victim only when intent on gorging

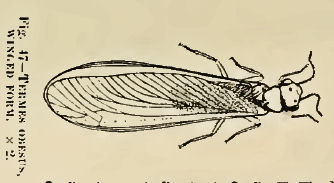

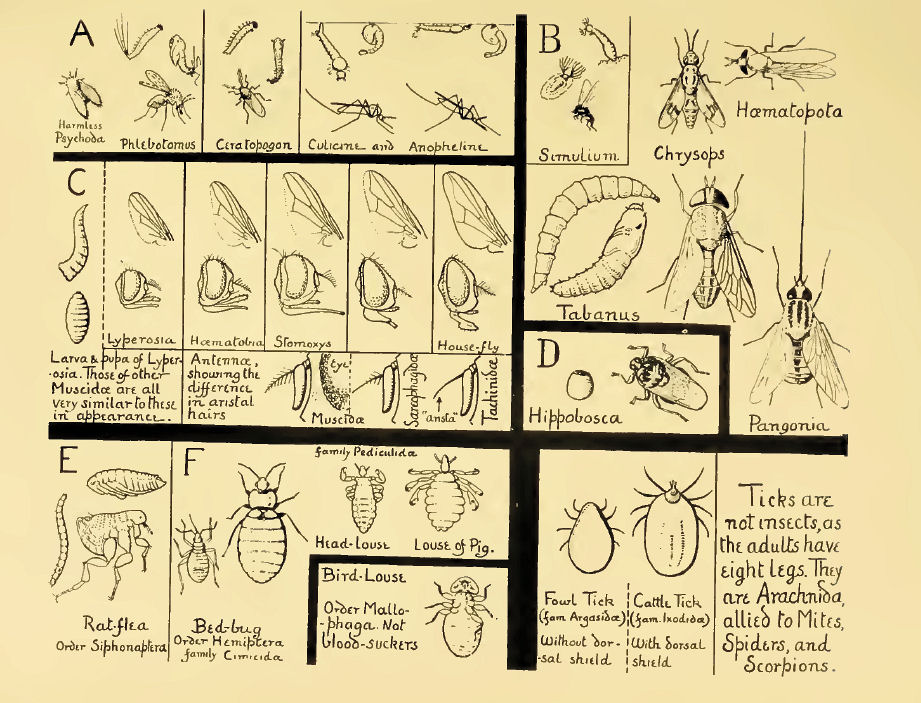

themselves with his blood. Of common vermin, the Bird-lice or

Mallophaga (p. 110), are not blood-suckers, though they live as parasites

on the bodies of their hosts : the blood-sucking species of insects at

present known in India may be said to belong exclusively to two Orders,

Diptera and Rhynchota.

To the first of these may be assigned the

Fleas, which probably represent a much-specialised offshoot from the old

Dipterous stock, though they are generally given the rank of a separate Order

or Sub-order (Siphonaptera). They represent that section of the Diptera

which pass a considerable portion of their adult life on the host,

though the egg. larval, and pupal stages are usually gone through elsewhere, in

dusty and dirty places. Their importance in connexion with plague is

well known. Except for the fleas, few blood-sucking Diptera spend

much time on the body of the host, but the lives of adult Nycteribiidae

and Hippoboscidae afford an interesting series of examples of variation

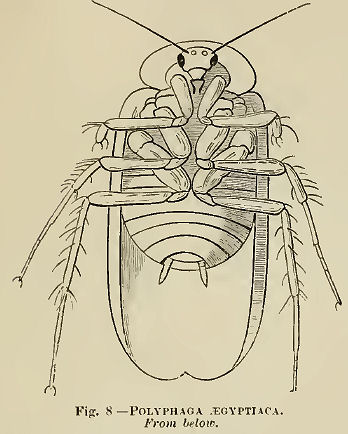

in this respect. Some of them, for instance the one figured on PI.

LXIX, fig. 8, appear to pass at least most of their lives on the host, and

most of these species are wingless or feeble-winged : at the other end

of the scale are the common cattle-flies (Hippobosca) which have strong wings, are quick

fliers, and are always ready to strike camp and leave the

host on whom they havesettled, though remaining if comfortable and

undisturbed. These two families exhibit the mode of reproduction

characteristic of the group (Pupipara) to which they belong (p. 655),

and although little is known of their habits and life-histories it is

probable that, as is the case with all other blood-sucking Diptera, the adult

stage is the only one which has any direct connexion with the host, while as

indicated above the closeness of this connexion varies considerably within

the limits of the two families, and probably has influenced the

reproductive processes to a considerable extent.

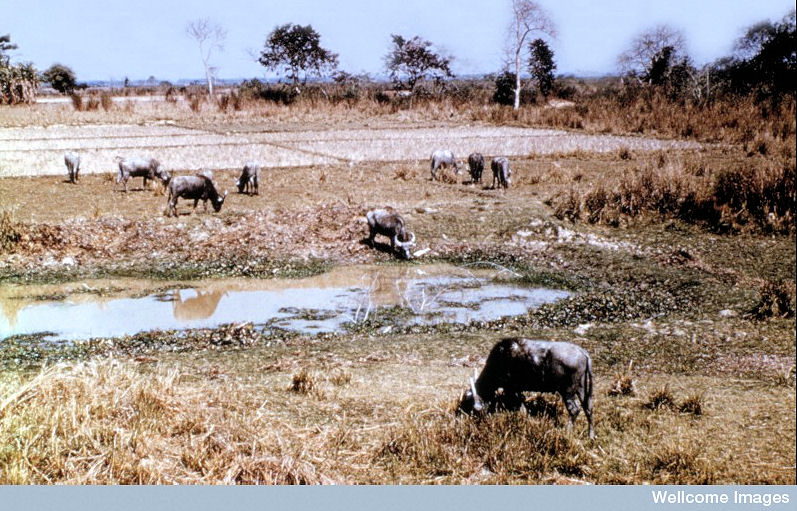

After those groups, Siphonaptera and Pupipara, which pass a considerable portion of their

adult lives on the host, we come to those Diptera which pay as a rule

only flying visits to their victim, and take their leave after a short

but hearty meal of blood. These belong to six families, and of these

families five are particularly well represented in this country, the sixth

(Chironomidae) being comparatively unimportant. The family which by relationship

and habits approaches most nearly to the Pupipara is the

Muscidae : as with the Hippoboscidae, which practically never bite

man, the attacks of the Indian species of Muscidae are as a general rule

confined to cattle, but this is by no means always the case, as in some

districts and climatic conditions they (especially Stomoxys) will bite men

viciously. Stomoxys is the commonest of the Indian genera, the others being

Lyperosia, Haematobia, Philaematomyia and Bdellolarynx. All the four

latter are found as larva in dung, but Stomoxys breeds by preference in

fermenting vegetable matter, especially in heaps of grass and

fodder, and in the piles of "seet" near indigo-vats, the flies being

often so abundant at the period of mahai as to be a serious nuisance. These

Muscidae often remain for a considerable time on the cattle, but this

is probably in part because they are so frequently interrupted in their

feeding by the movements of the victim, and they will persevere in the

attack until satisfied with blood. All the blood-sucking Muscidae have a

strong superficial likeness to many other Muscidae which do not suck

blood, such as the house-fly, and to others which are often found sucking

blood from wounds but which cannot pierce the skin for themselves :

this the five blood-sucking genera are of course able to do, but whereas

in Stomoxys, Lyperosia, and Haematobia we find a much modified and

developed piercing proboscis, the mouth-parts (as also the venation) in one

of the two new genera (Philaematomyia) differ much less

conspicuously from those of the non-bloodsucking Muscidae, and the genus represents a

connecting link between the two groups.

Although not

blood-suckers, the flies whose larvae live in wounds or sores may be here

noted as also belonging at all events for the most part to the family

Muscidae : the attacks of these maggots produce results often of a serious

and revolting nature, and are technically known under the term "

Myiasis." They attack both men and animals.

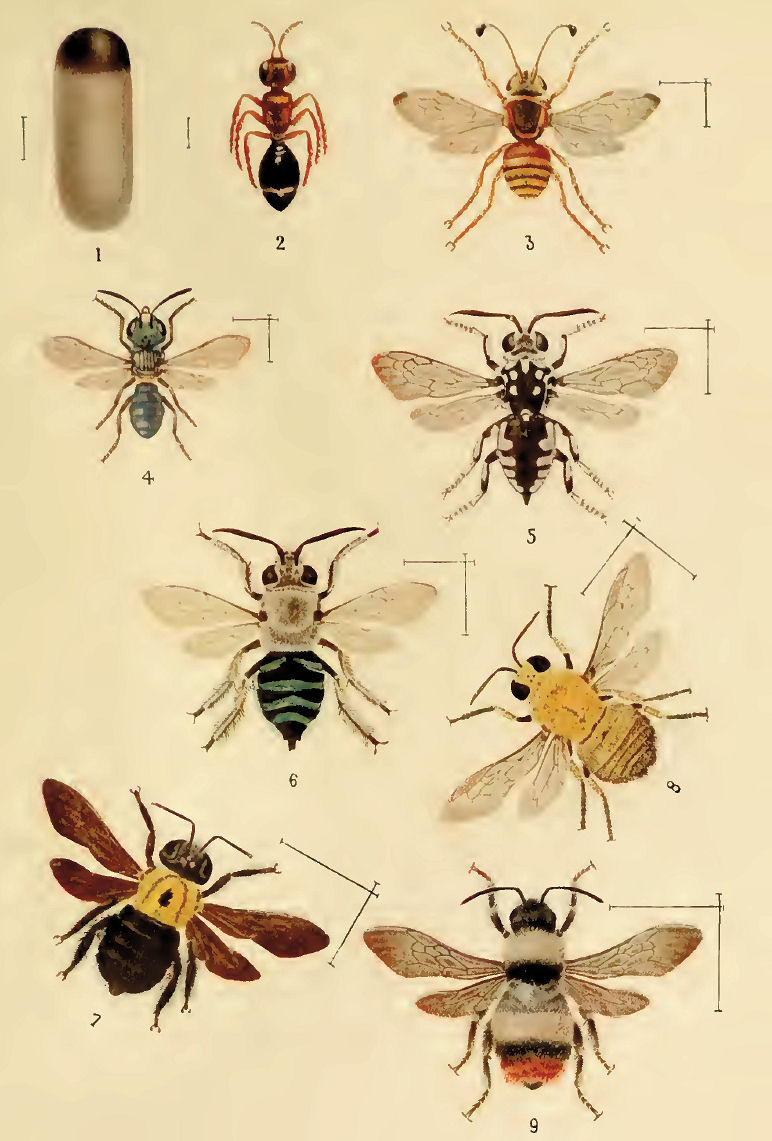

To the family Tabanidae (Pl. LXII) belong a

large number of species of the well-known Indian Horse-flies,

Dans-flies, gad-flies, or "Clegs." The Siphonaptera, Pupipara, and Muscidae

comprise only insects whose immature stages are purely terrestrial, but

in practically all species belonging to the remaining families of

blood-suckers we find semi-aquatic or purely aquatic larvae ; these families

may be arranged roughly in the order Tabanidae and Psychodidae (genus

Phlebotomus). Chironimidae (genus "Ceratopogon"), Siniuliidae and

Culicidae.

The larvae and pupa of the last two families

are purely aquatic ; the larvae of Tabanidae and Phlebotomus live in

mud, slime, or wet earth, and seek a comparatively dry spot in which to

pupate, while the larvae of Ceratopogon are of two kinds, some living

under bark and in similar damp shady places, while others are purely aquatic

and agree in this respect with the numerous species of

non-blood-sucking Chironomidae. We may make a further generalization by saying that

in these families with aquatic or semi-aquatic larvae it is only

the female that sucks blood, whereas in the purely terrestrial families

both sexes may do so. None of the former group spend any very

appreciable portion of their lives on the victim, whereas several of the latter do.

As to the numerical ratio between

blood-sucking and non-bloodsucking species, this varies in the different

families to a considerable extent. Excepting a very few particular

cases, we may say that at least one sex of all species of Siphonaptera.

Pupipara, Tabanidae, Simuliidae, and Culicidae suck blood, but of the total

number of species of Muscidae, Psychodidae and Chironimidae only a very small

percentage have the habit : this paucity of species unfortunately

does not mean that the number of individuals of these three families

is any the less, for most of us have had abundant opportunities of

observing the prevalence of sand-flies (Phlebotomus) at certain seasons

of the year, although the number of species of this blood-sucking genus

probably does not represent five per cent, of the total number of

harmless species in the family to which it belongs. The same is true in an

even greater degree of the Midges (Ceratopogon. family Chironomidae) and

of the blood-sucking Muscidae, for they constitute only a very

small fraction of the total number of species in their respective

families.

As regards the second Order, Rhynchota, which

includes bloodsucking species among its members, we find again that

these form only quite a small proportion of the Order as a

whole. Among the Lice (Pediculidae) are species which pass their

whole lives from egg to adult on the body of the host, and whose structure has

evidently undergone great modification to fit them for a purely

parasitic existence. The Bugs (Cimicidae), though often remaining for

some considerable time on the body of the host (generally man), usually

pass the greater part of their lives elsewhere, and seek their victim

only when wanting blood.

The results of recent work on the relations

which exist between the life of blood-sucking insects on the one

hand, and on the other the life of man and of those animals which he breeds for

his pleasure and profit, have shown an unexpectedly close connection

between the two, and of this the practical outcome is seen in the growing

body of knowledge relating to the transmission and spread of disease

among men and cattle. There are two ways in which insects may carry the "germs" of disease from one place to another. They may alight upon

the excrement of diseased persons or animals, or upon sores on the body

or on any other infective matter, and may then convey the infection

elsewhere on their contaminated bodies or in their excreta. The transmission

in this case is purely mechanical and it is immaterial by what kind

of insect it is effected, though owing to the nature of their habits it

is the Diptera which are chiefly concerned. It is not however in this

connexion that the chief importance of blood-sucking insects lies, but

rather in the part they play in the propagation of diseases which are due

to the presence of certain microscopic parasites in the blood. It seems

that in general these parasites can infect a healthy animal only by being

directly introduced into its blood, and in the absence of

blood-sucking insects it is difficult to see how this could very often occur : on the

other hand, if blood-sucking insects are present they afford at once a

ready means whereby a blood-parasite might be sucked up from one

animal and introduced into another at a subsequent bite.

It is in this way that the parasites appear to be usually transmitted,

but there is still uncertainty as to the details of the process in many

cases : the chief difficulty lies in deciding whether the parasite is carried by

the insect from one animal to another in a simply 'mechanical' way, undergoing no change en route, or whether, as in the case of the

malarial mosquitoes, the parasite on entering the insect's body undergoes a

more or less prolonged series of changes before it is in a fit state again

to infect a healthy animal's blood. The fact that insects have been found

to have parasites of their own which are extremely similar to certain

forms of mammalian blood parasites renders the matter more

complicated, as does also the remarkable hereditary transmission of infective power

exhibited by certain Ticks. The consideration of the Arachnids is

outside the field covered by this book, but the Ticks are of great

importance as pests of cattle and dogs, which they infect with spirillar

diseases ("Tick-fever," etc.) and with Piroplasmosis (Biliary fever), while

they are also responsible for an often fatal disease of fowls and for a

human relapsing fever, a remarkable feature being that in some species

the infection is not transmitted by the Tick which bites a diseased animal,

but by that Ticks' young ones. As regards the Rhynchota, there

is a strong presumption that Bed-bugs are responsible for the spread

of human disease, and it appears that they are capable of harbouring

the organism which causes Kala-azar and possibly of transmitting it by

their bite (Rogers and Patton). Comparatively little attention has

yet been paid to the Pediculidae which infest animals in India, but the human

head-louse has been shown to transmit a spirillar fever among

school-children (Mackie). Of those Diptera which chiefly attack cattle

(Hippobosca, Stomoxys, and Tabanidae) all three families are suspected

of being the agents whereby Surra, a serious cattle-disease, is spread,

and investigations are now being carried on in this country with a view

to deciding their relative importance in this connexion. (Leese).

While the Indian Hippoboscidae, Muscidae, and

Tahanidae are primarily pests of horses, dogs, and cattle, the

remaining families of Diptera attack man freely, though they none of them

confine their attentions entirely to human beings; the bull-flies or

"buffalo-gnats" (Simuliidae) are said to bite so fiercely and impartially

as to render certain hill districts practically uninhabitable during

part of the year, either for man or beast, and the ferocious little

sand-flies of the plains are well-known as disturbers of our slumbers. No very

serious study of the Simuliidae,. or of Chironomidae or Psychodidae

seems to have been made from the medical or veterinary point of view,

attention having been mainly directed to following up and extending

the original researches of Ross and others on Mosquitoes, but the

possibility of sand-flies transmitting disease would seem at least worth

investigation in this country.

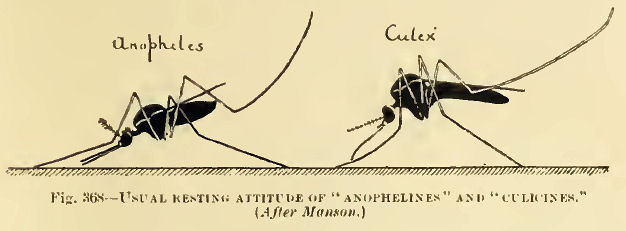

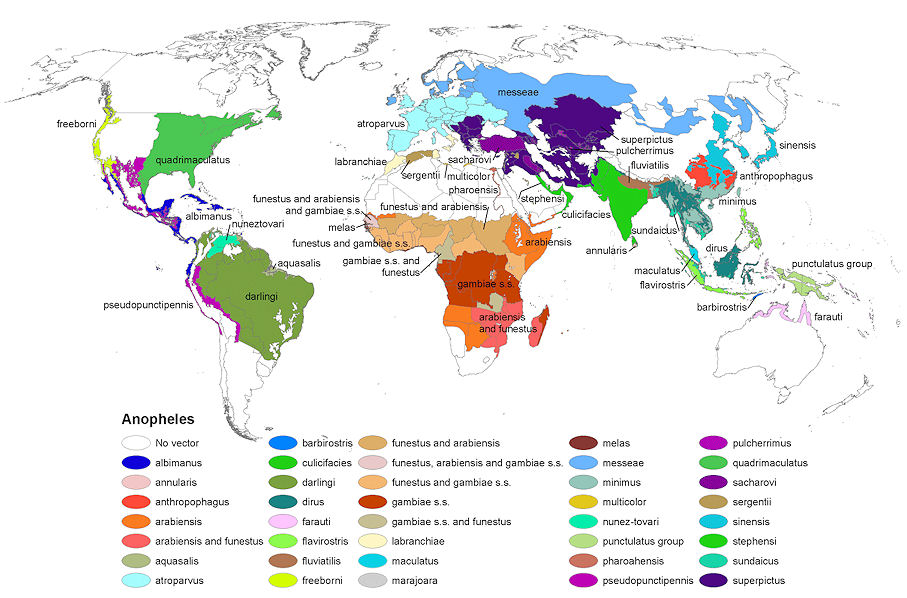

As far as the Indian species of Culicidce are

concerned, reference to the list will show that we have about a

hundred species at present known, though it is certain that a

considerable number still await discovery. Of these only a part act as

disease-carriers ; and, of those species known to be capable of so

acting, not all have been found actually carrying disease-parasites in

nature, but have been proved by experiment to be able to carry them. It is

not improbable that all species of the genus Anopheles will be found

capable of carrying the malaria-parasite. The commonest Myzomyia (M.

rossi) is not a natural malaria-carrier, but M. culicifacies, christophersi (=listoni) and Turkhudi are. Of the genus Nyssorhynchus, N.

stephensi, fuliginosus, Indiensis, and Theobaldi are carriers :

perhaps also Cellia albimana. All these species are Anophelinae. Among the

Toxorhynchinae and Addinae none are known to convey disease, but the

Culicidae include several dangerous species. Of these by far the

commonest is Culex fatigans, the common brown household mosquito of Northern

India. This insect carries the worm-like parasite (Filaria)

which is t4ie cause of various painful and unsightly conditions grouped

together as "Filariasis" and including elephantiasis, lymphangitis,

and divers varicose affections particularly common in South India. Culex fatigans has been suspected

of complicity in the spread of some other

diseases, but hitherto without definite proof. Another Culicinae

genus, Stegomyia, is abundant in India, the commonest species being S. scutellaris, which seems to be widely spread. A closely related species, S.

fasciata, occurs, in Bengal, in the neighbourhood of Calcutta, and this

particular species is well known to be the carrier of yellow fever in

the West Indies : whether S. scutellaris can also convey this most

deadly disease is unknown."

[Quelle:

Maxwell-Lefroy, H. (Harold)

<1877-1925>: Indian insect life : a manual of the insects of

the plains (tropical India). -- Calcutta, 1909. -- S. 659ff.] |