|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 15. vaiśyavargaḥ (Über Vaiśyas). -- 11. Vers 83d - 90b: Handel II: Zahlen und Maße. -- Fassung vom 2011-09-21. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa7/amara215k.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-09-21

Überarbeitungen:

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

| 83c./d. vipaṇo vikrayaḥ

saṃkhyāḥ saṃkhyeye hy ā daśa triṣu 84a./b. viṃśatyādyāḥ sadaikatve sarvāḥ saṃkhyeya-saṃkhyayoḥ 84c./d. saṃkhyārthe dvi-bahutve stas tāsu cā navateḥ striyaḥ 85a./b. paṅkteḥ śata-sahasrādikramād daśa-guṇottaram

विपणो विक्रयः

संख्याः संख्येये ह्य् आ दश त्रिषु ।८३ ख। Bezeichnung für das Zählbare (saṃkhyeya 3) ist संख्या - saṃkhyā f.: Zahl, Zahlwort, Numerus Die Kardinalzahlwörter bis 10 und solange sie daśan enthalten (d.h. bis 18 bzw. 19) sind Adjektive. Die Zahlwörter für 20 usw. sind immer Singular. Wenn sie verwendet werden im Sinne der Zahl des zu Zählenden und der Numerus (d.h. um den Numerus und die Kardinalzahl auszudrücken) stehen sie im Dual bzw. Plural. Von diesen (d.h. ab 20) sind die Kardinalzahlen bis 90 Feminina. In der Reihe śata (100), sahasra (1000) usw. ist das Nachfolgende jeweils das Zehnfache des Vorhergehenden. |

Colebrooke (1807): "Numerals. Numerals, from 1 to 18, agree in gender with the subject numbered. Other numerals (19) 20, &c. are singular ; but may be dual or plural, if used distributively. Ex. विंशती, two scores. The numerals, 20 to 90, are invariably feminine. Numeration proceeds in decuple proportion."

Abb.: संख्यानम् । Karni Mata (करणी माता)

Temple, Deshnoke - देशनोके, Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: Neil Hinchley. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/neilhinchley/50518886/in/photostream/. --

Zugriff am 2011-09-21. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

संख्या - saṃkhyā f.: Zahl, Zahlwort, Numerus

Zahlzeichen in verschiedenen indischen Schriften:

| English | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bengali | ০ | ১ | ২ | ৩ | ৪ | ৫ | ৬ | ৭ | ৮ | ৯ |

| Oriya | ୦ | ୧ | ୨ | ୩ | ୪ | ୫ | ୬ | ୭ | ୮ | ୯ |

| Devanagari | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| Punjabi | ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ |

| Gujarati | ૦ | ૧ | ૨ | ૩ | ૪ | ૫ | ૬ | ૭ | ૮ | ૯ |

| Gurmukhi | ੦ | ੧ | ੨ | ੩ | ੪ | ੫ | ੬ | ੭ | ੮ | ੯ |

| Telugu | ౦ | ౧ | ౨ | ౩ | ౪ | ౫ | ౬ | ౭ | ౮ | ౯ |

| Kannada | ೦ | ೧ | ೨ | ೩ | ೪ | ೫ | ೬ | ೭ | ೮ | ೯ |

| Malayalam | ൦ | ൧ | ൨ | ൩ | ൪ | ൫ | ൬ | ൭ | ൮ | ൯ |

| Tamil | ೦ | ௧ | ௨ | ௩ | ௪ | ௫ | ௬ | ௭ | ௮ | ௯ |

Die Kardinalzahlwörter bis 10 und solange sie daśan enthalten (d.h. bis 18 bzw. 19) sind Adjektive.

१ - 1 एक - eka 3 २ - 2 द्वि - dvi 3 ३ - 3 त्रि - tri 3 ४ - 4 चतुर् - catur 3 ५ - 5 पञ्च - pañca 3 ६ - 6 षष् - ṣaṣ 3 ७ - 7 सप्तन् - saptan 3 ८ - 8 अष्टन् - aṣṭan 3 ९ - 9 नवन् - navan 3 १० - 10 दशन् - daśan 3 ११ - 11 एकदशन् - ekadaśan 3 १२ - 12 द्वादशन् - dvādaśan 3 १३ - 13 त्रयोदशन् - trayodaśan 3 १४ - 14 चतुर्दशन् - caturdaśan 3 १५ - 15 पञ्चदशन् - pañcadaśan 3 १६ - 16 षोडशन् - ṣoḍaśan 3 १७ - 17 सप्तदशन् - saptadaśan 3 १८ - 18 अष्टादशन् - aṣṭādaśan 3 १९ - 19 नवदशन् - navadaśan 3 (ऊनविंशति ūnaviṃśati f.)

Von diesen (d.h. ab 20) sind die Kardinalzahlen bis 90 Feminina.

२० - 20 विंशति - viṃśati f. ३० - 30 त्रिंशत् - triṃśat f. ४० - 40 चत्वारिंशत् - catvāriṃśat f. ५० - 50 पञ्चाशत् - pañcāśat f. ६० - 60 षष्टि - ṣaṣṭi f. ७० - 70 सप्तति - saptati f.: ८० - 80 अशीति - aśīti f. ९० - 90 नवति - navati f.

In der Reihe 100, 1000 usw. ist das Nachfolgende jeweils das Zehnfache des Vorhergehenden.

| 100 | 102 | शत - śata n. | Hundert |

| 1.000 | 103 | सहस्र - sahasra n. | Tausend |

| 10.000 | 104 | अयुत - ayuta n. | |

| 100.000 | 105 | लक्ष - lakṣa n., f. | Lakh |

| 1.000.000 | 106 | प्रयुत - prayuta n. | Million |

| 10.000.000 | 107 | कोटि - koṭi f. | Crore |

| 100.000.000 | 108 | अर्बुद - arbuda n. | |

| 1.000.000.000 | 109 | अब्ज - abja n. | Milliarde |

| 10.000.000.000 | 1010 | खर्व - kharva m., n. | |

| 100.000.000.000 | 1011 | निखर्व - nikharva m., n. | |

| 1.000.000.000.000 | 1012 | महापद्म - mahāpadma m. | Billion |

| 10.000.000.000.000 | 1013 | शङ्कु - śaṅku m. | |

| 100.000.000.000.000 | 1014 | जलधि - jaladhi m. | |

| 1.000.000.000.000.000 | 1015 | अन्त्य - antya n. | Billiarde |

| 10.000.000.000.000.000 | 1016 | मध्य - madhya n. | |

| 100.000.000.000.000.000 | 1017 | परार्ध - parārdha n. |

Merkvers:

एक-दश-शत-सहस्रायुत-लक्ष-प्रयुत-कोटयः क्रमशः ।

अर्बुदम् अब्जं खर्व-निखर्व-महापद्म-शङ्कवस् तस्मात् ॥

जलधिश् चान्त्यं मध्यं परार्धम् इति दशगुणोत्तराः संज्ञाः ।

संख्यायाः स्थानानां व्यवहारार्थं कृताः पूर्वैः ॥

Bhāskara <ಭಾಸ್ಕರ> <1114–1185>: Līlāvatī. -- Vers 10-11

| 85c./d. yautavaṃ druvayaṃ pāyyam

iti mānārthakaṃ trayam यौतवं द्रुवयं पाय्यम् इति मानार्थकं त्रयम् ।८५ ख। Die drei Bezeichnungen für Maße sind:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Measure."

Für die einzelnen Maße und Gewichte können keine genauen metrischen Entsprechungen angegeben werden, da - wie auch in Europa vor der universellen Normierung - lokal, Waren-, Transaktions- und Berufs-bezogen die Werte der einzelnen Maße beträchtlich voneinander abwichen:

"A variety of nominal measures, and of values given to the same measure, exist in different parts of India, and even in the same district. Even in a single village a certain nominal measure will have half a dozen different values, according to which of as many different articles on the floor of the vendor in the bazaar is about to be sold. It is a very general custom that there should be two series of weights employed in each shop, according to the transaction. When the shopkeeper sells, he uses a maund of 24 lbs., but when he buys, this weight makes way for another of the same name of 28 lbs. In Azimgarh, for example, cotton and spice are measured by the seer of 80 tolas, ghee and salt by the seer of 96 tolas, while 96 tolas forms the rate for corn, sugar, and tobacco ; the merchants themselves employing for their own purchases seers of 105 and 108 tolas. In Malda the seer has no less than fifteen different values,—50, 58, 60, 72, 75, 70, 80, 80 5/8, 91, 92, 94, 96, 100, 101, and 105 tolas. In Dacca the relative values are 60, 70, and 82 tolas. Bhagulpur boasts of six different seers of 64, 67, 80, 88, 101, and 104 tolas respectively. The merchants of Juanpur employ in their own dealings a seer of 112¾ tolas, but retail to the people in seers of 80 and 96 tolas. Cotton is sold in Madras in candies of 500 lbs., but in many of the cotton districts the candy is but 480 lbs. to the ryot. In Mysore, the same name represents 560 lbs., while in Pondicherry it sinks to 517 lbs., omitting fractions, and rises in the purchases of the merchants to 562 lbs. ; while, as if further to complicate this measure, brass, copper, and zinc are valued according to candies of 450 lbs. In Kandesh, sesamum seed is sold by the candy of 560 lbs., mustard seed in Gujerat is measured by the candy of 612 lbs., while 580 lbs. is the value for mustard seed in Sholapur ; and the territory of Goa measures its kokum by the candy of 784 lbs. The coffee grown in Mysore is estimated in maunds of 28 lbs. If bought by a Madras merchant, it is priced in maunds of 25 lbs., and transmitted to him by railway in maunds of 82 lbs. ; but if bought for export from Calicut, it must be in maunds of 30 lbs. each.

The ordinary Madras maund is 25 lbs. ; in Bengal it is 82 lbs. ; while in Bombay it is 28 lbs. In some parts of the western coast of the Madras Presidency 30 lbs. is the value of the same nominal standard, while the indigo and other factory agents of Bengal reckon by a maund of nearly 75 lbs. In Bombay the bazar maund may contain 40 or 42 seers, while the candy may contain either 20, 21, or 22 maunds, and varies in weight from 500 to 560, 588, or even 616 lbs. In Surat and its neighbourhood, the maund may contain either 40, 41, 42, 43¼, or 44 seers, according to the article sold, or whether the transaction be wholesale or retail ; and further, these seers themselves differ so much in value, that while the maund of 40 seers weighs 31 lbs. avoirdupois, that of 41 seers weighs 38 lbs. ; that of 42 seers only 39 lbs. ; that of 43¼ seers weighs 44 lbs. ; and that of 44 seers only 41 lbs. ! In Travancore the maund is 32 lbs. In Cuttack salt is sold in maunds of 100 lbs.; the duty is paid in the Panjab on maunds of 80 lbs., and in Calcutta of 82 lbs.

The original unit of weight in Southern India seems to have been the gold coin called by the English a pagoda. It is now uncurrent, but was about 52½ grains weight. 80 pagodas weight is, according to the native tables, a seer (cutcha) of 24 rupees weight. This corresponded with the average weight of the old native rupee of 175 grains ; but since the introduction of the Company's rupee of 180 grains, the pagoda weight is 54 grains generally. The same confusion formerly existed in Bengal between a Sicca weight of 179 2/3 grains and a Sicca rupee of 192 grains. There are also seers both in Madras and Bombay of 84 rupees weight. A greater degree of confusion could not possibly exist, nor greater hindrances to internal trade and prosperity."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 3. -- 1885. -- S. 1057f.]

यौतव - yautava n.: Gewicht

Abb.: यौतवम् । Standard-Seer (سیر) von Almora -

अल्मोड़ा,

Uttarkhand

[Bildquelle: Shyamal / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

द्रुवय - druvaya n.: (hölzernes) Hohlmaß

Abb.: द्रुवयाणि । Hohlmaße, Folk Culture Museum - ಜನಪದ ಲೋಕ

- Janapada Loka, ರಾಮನಗರ - Ramanagara, Karnataka

[Bildquelle: Hari Prasad Nadig. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/hpnadig/4582673113/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-19. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

पाय्य - pāyya n.: Maß (wohl Längenmaß)

Abb.: पाय्यम् । Schneiderei, Delhi

[Bildquelle: Arti Sandhu. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/artisandhu/5447921425/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-19. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

"Neunzehntes Kapitel (37. Gegenstand). Eichung von Wagen und Maßen [तुलामानपौतवम् - tulāmānapautavam].

Der Eichungsaufseher soll auf die Eichung bezügliche Fabriken einrichten lassen.1

Bohnen vom Acker (dhānyamāṣa) oder 5 Guñjābeeren (Beeren des Abrus precatorius) sind eine Goldbohne (suvarṇamāṣa). 16 Goldbohnen sind 1 Suvarṇa (etwa »Goldener«) oder 1 karṣa (»Kritz?«).2 4 karṣa enthält 1 pala (»Stroh«?). 88 weiße Senfkörner sind eine Silberbohne (rūpyamāṣa). 16 davon3 oder 20 Śaibyakernchen (oder Śaibyabohnen) sind 1 dharaṇa. 20 Reiskörner sind gleich einem Diamanten-dharaṇa (vajradharaṇa).4

(Die Gewichte oder Gewichtsteine sind:) Ein halber māṣa (Bohne), 1 māṣa, 2, 4, 8 māṣa; 1 suvarṇa (oder karṣa), 2, 4, 8 suvarṇa; ferner: 10, 20, 30, 40, 100 (suvarṇa).

Die Gewichte sind gemacht: aus Eisen oder aus Stein vom Magadhaland oder aus MekhalasteinA1, 5 oder doch von solcher Art, dass sie durch Wasser und Beschmierung nicht (an Schwere) zunehmen und durch Hitze nicht abnehmen.

Von 6 aṅgula Länge und 1 pala (dazu verwendeten) Metall anfangend und von da an um je 8 aṅgula Länge und 1 pala Metall zunehmend, soll er 10 (Arten von) Wagbalken machen lassen. An jede der zwei Seiten eine Vorrichtung zum Halten oder eine Wagschalenschlinge (śikya).6

Er soll einen Samavṛttā-Wagbalken machen lassen aus 35 pala Metall und 72 aṅgula lang.7 An diesen soll er eine Wagschale (maṇḍala)8 von 5 pala Metall befestigen und ihn dann gleichmachen (d.h. die genaue Mitte ausfindig machen und bezeichnen) lassen. Dann soll er darauf bezeichnen lassen: von 1 karṣa aufwärts (alle karṣa bis zum pala), 1 pala, von 1 pala aufwärts, 10 pala, 12 pala, 15 pala, 20 pala.9 Dann soll er (alle Zehner) von 10 aufwärts bis 100 bezeichnen lassen. An allen Fünferstellen (also bei 5, 15, 20, 25 usw.) soll er das Segenszeichen (nāndī oder svastika) anbringen lassen.10

Er soll eine Wage (einen Wagbalken) aus zweimal soviel Metall und von 96 aṅgula Länge machen lassen, die parimāṇī (etwa »Messerin«). An ihr soll er, von dem Hundertzeichen anfangend, Zeichen für 20, 50, 100 anbringen lassen.11

1 bhāra (»Last« enthält bei dieser Wage) 20 tulā.12 1 pala (enthält bei dieser Wage) 10 dharaṇa.13 100 solcher pala sind eine āyamānī (»Einkommenmesserin«, wohl Einheit bei Berechnung des königlichen Einkommens, dann »Königswage«). Um je 5 pala nehmen die Gewichtsnormen (bhājanī) ab 1. für den gewöhnlichen Verkehr (vyavahārikī), 2. für die Dienerschaft (des Königs) und 3. für das Frauengemach.14

Bei ihnen nimmt das pala je um ein halbes dharaṇa ab, um je 2 pala das Metall des oberen Teiles (d.h. des Wagbalkens), um je 6 aṅgula die Länge.15

Bei den zwei ersten (der samavṛttā und der parimāṇī) gibt es eine Dreingabe (prayāma, »Streckung«) von 5 pala,16 ausgenommen bei Fleisch, Metall, Salz, und Edelsteinen.

Die Wage für Holz17 ist 8 hasta (also 12 Fuß)A2 lang, versehen mit Gewichtszeichen und Gegengewichten (d.h. Gewichtsteinen) und auf einem Pfauengestell18 ruhend.

25 pala Holz kochen ein prastha Reis gar. Dies ist ein Fingerzeig für viel und wenig.A3 19

Damit sind Wage und Gewichtssteine dargelegt.

Weiter:20 200 pala, nach dhānyamāṣa oder »Feldbohnen« berechnet, geben, 1 droṇa in āyamāna (der Messart des königlichen Einkommens), 187 ½ pala 1 droṇa nach der Norm des gewöhnlichen Verkehrs, 175 pala 1 droṇa nach dem Dienergewicht; 162 ½ pala nach der Haremsmaßordnung.

Diesen (4 Arten von droṇa) gegenüber nehmen āḍhaka, prastha und kuḍumba (oder kuḍuba) je um ein Viertel ab.21

16 droṇa sind 1 khārī. 1 kumbha enthält 20 droṇa. Durch 10 kumbha kommt 1 vaha zustande.22

Die Hohlmaße soll er aus trockenem, hartem Holz, ebenmäßig und mit einem Viertel als Häufung machen lassen, oder auch mit der Häufung innen drin.23

Bei Saft (von Zuckerrohr und Früchten), Likör, Blumen und Früchten, Kornhülsen und Holzkohlen und gelöschtem Kalk steigt die Mehrung (d.h. die Aufhäufung) zum Doppelten der Häufungsnorm hinauf.24

1 ¼ paṇa ist der Preis eines Droṇamaßes, ¾ paṇa der eines solchen von 1 āḍhaka, 6 māṣa der eines von 1 prastha, 1 māṣa der eines Kuḍumbamaßes. Doppelt so groß ist der Preis der Maße für Saft usw. 20 paṇa für die Gewichtsteine (zu einer Wage). Dreiviertel soviel ist der Preis einer Wage.25

Als Eichungsgebühr soll er 4 māṣa ansetzen. Die Buße für nicht Geeichtes beträgt 27¼ paṇa. Sie (die Verkäufer) sollen Tag um Tag dem Aufseher über Maße und Gewichte eine kākaṇī für die Eichungsgebühr entrichten.26

Die »Vergütungsgebühr bei Erhitztem« (taptavyājī) beträgt 1/32 bei Schmelzbutter, 1/64 bei Sesamöl. 1/50 ist Messabfluss bei Flüssigkeiten.27

Er soll Maße von 1, ½, ¼, 1/8 und kuḍumba machen lassen.

84 kuḍumba Schmelzbutter und 64 Sesamöl gelten als ein vāraka, und ein Viertel (des betreffenden vāraka) ist bei beiden eine ghaṭikā.28

Fußnoten

1 Potu, nach den ind. Lex. = mānabhāṇḍaśodhaka »Prüfer der Maß- und Wägegeräte« bestätigt meine Vermutung, dass pauṭava Eichung bedeute. Völlig richtig und besser deutsch hieße die Kapitelüberschrift also: »Maß- und Gewichtswesen«. Mithin soll der Eichungsaufseher oder der Aufseher über Maß und Gewicht in den Fabriken Maß- und Wägegeräte herstellen lassen.

2 Ein karṣa nach Böhtlingk = 11,375 französische Gramm, nach Monier-Williams unter karṣa = 280 grains troy, unter suvarṇa aber = 175 grains troy. Diese zweite Angabe stimmt mit dem P.W., denn so bekommen wir ein ganz kleines bisschen weniger als 11,375 Gramm, oder genau: 11,3398163200 Gramm.

3 Muss bedeuten: von den Silberbohnen, obwohl es sich grammatisch eher auf die Senfkörner bezöge.

4 Gaṇ. sagt, es sei ein mitttelmäßiges unenthülstes Reiskorn gemeint. All die genannten sind Gewichtseinheiten.

5 Kann sein: ein Stein vom Berge Mekhala oder einer vom Lande der Mekhala. Zum folgenden vgl. auch Kalāv. VIII, 5.

6 Dies wohl besser als meine ursprüngliche Auffassung: »An beiden Seiten der Vorrichtung eine Wagbalkenschlinge oder auch nur an einer.« Zwar fand ich diese bei Bhaṭṭ., Sham. und Gaṇ. wieder. Aber sie ist grammatisch und sachlich nicht so wahrscheinlich. Immerhin kommt wohl vā bei Kauṭ. in der hier vorausgesetzten Bedeutung »beliebig« vor (vgl. 120, 9, 14). Doch dann sollte vā nach ubhayatas stehen. Die zweite Wage hat also einen Wagbalken von 14 aṅgula Länge und wiegt 2 pala, die zehnte ist 78 aṅgula lang und 10 pala schwer, wie uns Bhaṭṭ. vorrechnet.A4

7 Samavṛttā, seil. tulā, könnte auch heißen: ein gleichmäßig runder Wagbalken, und möglicherweise kommt daher der Name dieser Wage. Oder soll man es fassen als: Wage des gleichmäßigen Verfahrens, also Normalwage?A5

8 Vielleicht aber ist mit maṇḍala nicht die runde Wagschale, sondern einfach ein Metallring oder eine Metallkugel gemeint, mit deren Hilfe man die Mitte des Wagbalkens feststellt. Darauf deutet wohl das Gerundium oder Absolutivum. Eine Metallwagschale befindet sich aber jedenfalls an beiden Enden. Diese heißt jedoch 90, 16–17 kakṣya.

9 Es werden also Bezeichnungen (padāni) angebracht für 1 karṣa, 2 karṣa, 3 karṣa, 1 pala, 2 pala usw. bis zu 10 pala hinauf, dann aber nur für 10 pala, 12 pala usw., nicht mehr für die geringeren Gewichtsbestimmungen. Kārayet ergibt sich mühelos aus Sham.'s verstümmeltem Text. Padāni ist kaum nötig. Aber 104, 2–3 steht es, und so werden B und Gaṇ. recht haben, es auch hier zu setzen.

10 Gaṇ. hat naddhrīpinaddham. Dann: »soll er ein Riemchen (Lederstreifchen) draufbinden lassen«. Da kommt pinaddha besser zu seinem Recht. Dies Streifchen bezeichnet also die Fünferstellen.A6

11 Das wäre also eine weniger feine Wage.

12 »Eine tulā ist = 100 pala« (Bhaṭṭ.). Danach wäre 1 tulā = 4 Kilo 550 Gramm. Die »Last« betrüge da 91 Kilo.

13 Sham. sagt, nach dem Komm. sei dieses pala um ein karṣa größer als das gewöhnliche. Gan. aber bietet keine solche Bemerkung. Hat Sham. Recht, dann bekämen wir anscheinend sogar: 1 tulā = 5 Kilo 687½ Gramm, 1 »Last« = 113 Kilo 74 Gramm. Aber auch dann wären jene 5 karṣa wohl schließlich gleich 4 sonstigen. Vgl. Anm. 9.

14 Ist vielleicht die zweite dieser Wägenormen oder Wagen, weil sie einfach bhājanī (»Teilerin, Zuteilerin«) heißt, die ursprüngliche? Wunderlicher wäre das gewiss nicht als das ganze verzwickte, in seiner Verzwicktheit freilich nicht beispiellose System von Wägearten, die wohl schließlich alle darauf hinauslaufen, dem König Gewinn zu schaffen.

15 Also, wie uns Bhaṭṭ. auseinandersetzt:

10 dharaṇa =1 pala bei āyamānī-Gewicht (Einkommengewicht),

9½ dharaṇa =1 pala, bei vyavahārika- oder Verkehrsgewicht,

9 dharaṇa =1 pala bei bhājanī oder Dienergewicht,

8½ dharaṇa = 1 pala bei antaḥpurabhājinī oder Haremsnorm.

Das dharaṇa der Verkehrsnorm ist mithin um 1/20 größer als das des »Einkommengewichts«, das dharaṇa des Dienergewichts um 2/20, das der Haremswage um 3/20. Auf 100 pala ergibt das also bei der Wage des gewöhnlichen Lebens 5 pala, bei der zweiten Wage 10 pala, bei der dritten 15. Somit gleichen sich die Unterschiede aus. Das Dargewogene ist in Wirklichkeit immer gleich (gerade wie bei den verschiedenen Systemen der Philosophie). Erreicht wird so der höchste Triumph indischen Geistes: eine verzwickte Systematik. Ferner:

Die āyamānī ist 72 aṅgula lang und wiegt 53 pala.

Die vyavahārikī ist 66 aṅgula lang und wiegt 51 pala.

Die bhājanī ist 60 aṅgula lang und wiegt 49 pala.

Die antaḥpurabhājinī ist 54 aṅgula lang und wiegt 47 pala.

16 Man sollte erwarten und der Text könnte auch besagen, die Dreingabe betrage 5 pala beim gewöhnlichen Verkehrsgewicht und weitere 5 pala, also 10, beim Königsgewicht (oder doch auch hier 5 pala). Die Erläuterung im Text meiner Übersetzung kommt von Bhaṭṭ.

17 Wörtlich: »Holzwage«, was ebenso zweideutig ist wie das Deutsche. Aber das Folgende beweist, dass eine Wage für Holz gemeint ist, nicht eine aus Holz, wie die Inder meinen.

18 Wie Bhaṭṭ. erklärt, besteht dies aus zwei Pfosten mit einem verbindenden Balken obendrauf.

19 D.h. wohl nicht nur für geringere und größere Mengen des zu Kochenden, sondern auch: »Das ist ein Anhaltspunkt, Verschwendung oder Sparen festzustellen.«

20 Jetzt folgen die Hohlmaße.

21 D.h. ¼ droṇa= āḍhaka,

¼ āḍhaka=1 prastha,

¼ prastha=1 kuḍumba,

Oder:4 kuḍumba=1 prastha,

4 prastha=1 āḍhaka,

4 āḍhaka=1 droṇa.

Auf ein droṇa des königlichen Einkommens gingen nach dem, was wir eben gehört haben, 128000 der in Indien gewöhnlichsten Bohnen, d.h. der Frucht des Phaseolus radiatus. (Sie ist schmutzig schwarzbraun, wie es MBh. VII, 23, 52 heißt, malinaśyāma. Vgl. PW). Ein droṇa nach dem Verkehrsmaß enthält nur 120000 solcher Bohnen. Ein droṇa oder »Eimer« ist nach der Angabe von Monier-Williams (unter khārī) etwa = 6 quarts (1 quart = 1,1358955 Liter). Also kaufe sich, wer da kann, Bohnen des Phaseolus radiatus und zähle nach, ob es stimmt.

22 D.h. wohl ein Fuder. Die khārī beträgt nach Monier-Williams etwa 3 bushels (vgl. PW bes. unter droṇa, um die bösen Druckfehler von Mon.-Will. richtig zu stellen); das droṇa 6 quarts. Nach beiden Einheiten bekämen wir so 37½ bushels für den vaha oder über 2000 englische Pfund bei den schwereren Feldfrüchten, ein sehr ansehnliches Fuder für altindische Verhältnisse, möglicherweise aber ein Hinweis darauf, dass die Straßen verhältnismäßig in sehr gutem Zustand gewesen sind. Droṇa bedeutet sonst »Trog, Eimer«, kumbha »Krug«; hier ließe sich kumbha etwa mit »Kufe« wiedergeben. Das droṇa ist auch ein Feldmaß: »soviel Land, als zur Aussaat eines droṇa Getreides erforderlich ist« (PW). Vgl. damit unser deutsches ein »Scheffel Land« und ein »Krug Land« und dieses »Krug« auch mit kumbha.

23 D.h. die Maße müssen so hoch aufgehäuft werden, dass ein Viertel des ganzen gemessenen Kubikinhalts als śikhā »Spitze« oder Aufhäufung emporragt. Das ist nun in Wirklichkeit, wenigstens bei Körnerfrüchten, unmöglich, es sei denn man mache die Maßgefäße sehr niedrig und weit. Der amerikanische bushel Weizen z.B. enthält, wenn er glattgestrichen ist, 2140,42 Kubikzoll, aufgehäuft aber, und das gewiss mit allerpeinlichster Sorgfalt, 2747,71 Kubikzoll (Smith's Applied Arithmetic, Chicago-New York 1917–1918, Appendix p. 305. So nach freundlicher Mitteilung meiner früheren Schülerin Martha Merz in Chicago). Stimmt das, so ginge es doch. Aber man möchte ansetzen: 4 Viertel ins Messgefäß, ein 5 Viertel oben drauf als Häufung. Wir haben aber wahrscheinlich wieder eine kniffliche Theorie, die freilich auf primitive Verhältnisse zurückgehen mag. Das Wichtige steckt wahrscheinlich in dem »oder auch«, das wohl eher ein »und zwar« sein sollte. D.h. es musste das Maßwerkzeug so groß gemacht werden, dass es dieses »Überviertel« noch mit enthielt, wenn man es genau bis zum Rande füllte. Bei Getreide wurde dann glattgestrichen, wenn ich nicht irre. Flüssigkeiten muss man selbstverständlich dem Rande gleich machen. Für diese ist also notgedrungenerweise das Häufungsviertel immer »innen drin«A7. Bhaṭṭ., Sham. und Gaṇ. fassen nun rasasya tu als ein besonderes, zum Vorigen gehörendes Sätzchen. Da wäre ausdrücklich gesagt: »Dies aber immer bei Flüssigkeiten«. Darauf komme ich zurück.

24 Śikhāvṛddhi ist, also wohl »Häufungszins«, wucherischer Zins, nicht wie Bṛhasp. XI, 7–8 angibt, »interest growing like a lock of hair«. Auch Gaṇ. liest śikhāmānaṃ dviguṇottarā.A8 Die zunächst auftauchende, ursprünglich auch von mir gemachte Übersetzung lautet da: »Bei Saft, Likör ... Kalk ist das Häufungsmaß eine Zugabe (eine ›Mehrung‹), die zum Doppelten (der gewöhnlichen ›Häufung‹) hinaufsteigt«, also doppelt soviel. Aber warum dann nicht einfach dviguṇottaram ohne das völlig entbehrliche vṛddhi? Etwas erträglicher wird der Ausdruck, wenn man śikhāmāna (vgl. droṇam āyamānam usw. 104, 16 ff.) als Häufungsnorm fasst und den anusvāra tilgt. Danach habe ich übersetzt. Die Sache selber bleibt die gleiche. Es gehen da, wie Bhaṭṭ. ausdrücklich erklärt, statt 4 kuḍumba deren 5 auf einen prastha. Verwerfen muss ich die schon erwähnte Abtrennung von rasasya tu zu einem Sätzchen, wobei nur sechs Sachen herauskämen und »Saft« wegfiele. Rasa bedeutet bei Kauṭ. meistens Saft, besonders Zuckerrohrsaft. Flüssigkeit heißt bei ihm eher drava, wie schon auf derselben Seite (105, 18) zu lesen steht; freilich auch rasa. Rasādīnām 105, 11 wäre sinnlos, wenn rasa Flüssigkeit und nicht »Saft« bedeutete. Dviguṇottara hieße übrigens eher: »um je das Doppelte aufsteigend (zunehmend)«, d.h. bei Saft doppelt so groß, bei Likör vierfach so groß, bei Blumen sechsmal so groß und so fort. Vgl. z.B. 108, 10. Aber wo kämen wir da hin!

25 Sham, nimmt tribhāga als ein Drittel, übersetzt also 6 2/3 pana. Noch weit billiger waren die Wagen nach der Auslegung Bhaṭṭasvāmins, der ebenfalls 1/3 ansetzt, aber von einem paṇa. Freilich sagt er, nur die zuerst beschriebene und billigste Art Wage habe soviel gekostet, die zehnte 1 1/3 paṇa. Auch ¾ paṇa wäre möglich. Freilich hätte in diesen zwei letzten Fällen die Deutlichkeit eigentlich ein paṇatribhāgaḥ erfordert.

26 Wörtlich »Die Eichungsgebühr sollen sie als eine kākiṇī betragend Tag um Tag bezahlen«, also in Raten von einer k. den Tag. Māṣa und kākiṇī, die wir als Gewichtseinheiten haben kennen lernen, sind beides auch kleine Geldeinheiten oder Münzen. Für die kākiṇī wird ¼ māṣa als Gleichwert angegeben. Beim Gewicht des Goldschmieds stimmte das. Hier mag kākiṇī Kaurimuschel sein, und dafür spricht auch der Gebrauch der kākiṇī als Würfel bei Kauṭ. (Buch III, Kap. 20). 80 kaparda oder Kaurimuscheln gehen auf 1 paṇa nach der gewöhnlichen Angabe, ebenso 20 māṣa. Oder nach der Gewichtsrechnung: 1 suvarṇa (paṇa) = 16 māṣa; 1 māṣa = 4 kākiṇī. Nach beiden Rechnungen hätten sie also in 16 Tagen ihre Eichungsgebühr abgetragen gehabt. Ist dann schon wieder geeicht worden? Nicht unmöglich; denn die Beamten müssen was zu tun haben, und der Staatssäckel braucht Geld. Nach Manu VIII, 403 wurden aller sechs Monate die Wagen geprüft. Gaṇ. nun liest caturmāsikam statt caturmāṣikam: »Aller vier Monate soll er die Eichung vornehmen lassen.« Nach ihm hätten sie also 120 kākiṇī zu zahlen. Die Ausdrücke pratividdha und prātivedhanika scheinen zu zeigen, dass zur Eichungsbeglaubigung irgend etwas durchlocht wurde. Oder nur »dagegengedrückt«, gestempelt? Vgl. S. 137, Anm. Zeile 39.A9

27 Diese Vergütung hätten natürlich die Käufer erhalten sollen. So versteht es auch Sham. Aber wie ich schon dargelegt habe, bekam wohl der König auch diese wie andere vyājī. Ebenso habe ich schon auseinandergesetzt, dass die »Vergütung bei Erhitztem« angesetzt wird, weil der Käufer soviel von diesen Fetten bekommen sollte, als von der erhitzten Flüssigkeit durch das betreffende Hohlmaß abgemessen wird, während sie doch in bedeutend festerem Zustand zum Verkauf gelangt, also etwas am Messgefäß hangen bleibt.

28 Vāraka, wörtlich: »Abhalter, Drinhalter«? Ghaṭlkā = Krug, Krüglein. Hier noch eine kleine Tabelle der Hohlmaße mit den englischen Entsprechungen.

1 droṇa=etwa 6 quarts

1 āḍhaka=etwa 1½ quarts.

1 prastha=etwa 3/8 quart

1 kumbha=3 bushels und 12 quarts

1 vāraka=etwa 8 quarts

1 ghaṭikā=etwa 2 quarts.

A1 Lies Mekala. Ebenso in der Anm.

A2 Lies: »also 14 Fuß«. Der hasta bei Wagen ist ja 28 aṅgula lang. Doch vgl. die Zusatzanm. zu 158. 41.

A3 Mithin braucht es 1137,5 Gramm Holz, einen prastha Reis, d.h. etwa 3/8 quart oder eine Mahlzeit für einen Mann zu kochen. Muss ein einzelner prastha zubereitet werden, dann wird das auch mit sehr trockenem Holz schwer halten. Wie die Weiber wissen, wann der Reis genug gekocht ist, berichtet Paramatthadīp. 67.

Ich habe nach dem natürlichen Sinn von mayūrapadādhiṣṭhita oder – ādhiṣṭhāna, wie Gaṇ. liest, übertragen. Stutzig aber macht eine Vergleichung von Bhaṭṭ.'s Erklärung und der Beschreibung des Gottesurteils mit der Wage in der Smṛti, besonders bei N. I, 260ff. Der Wagbalken ist da 4 hasta lang und muss aus bestimmten Holzarten bestehen, von denen das Tindukaholz befremdet, da es nach Viṣṇu LXI, 3 offenbar als magisch gefährlich gilt. Als Pfostenfüße werden zwei entastete Stämme (muṇḍaka), 2½ hasta voneinander entfernt, eingegraben, 2 hasta in die Erde hinein, 4 hasta emporragend. Oben darüber müssen wir uns offenbar einen Verbindungsbalken denken, an dem der Wagbalken befestigt wird. Danach schiene es, als solle man unsere Kauṭilyastelle übersetzen: »an einem Pfauengestell angebracht« (wörtlich etwa: darauf beruhend, davon abhängig). Aber beim Gottesurteil handelt es sich offenbar um ein besonderes altertümliches Gerät, wie schon śilā »Gewichtstein« und die ganze urtümliche Art des Wägens zeigt.

A4 Übrigens wäre es wichtig zu erfahren, aus welchem Metall (loha) denn Kauṭ.'s Wagen gemacht sind. Man stelle sich z.B. die letztgenannte vor. Sechs Fuß und vier Zoll, also beinahe zwei Meter ist sie lang und wiegt nur einen Schatten mehr als ein englisch-amerikanisches Pfund, also weniger als ein gewöhnliches europäisches. Ja, vielleicht sind die Wagbalken noch etwas länger; denn bei Wagen hat der hasta 28 aṅgula statt der gewöhnlichen 24. Oder ist da der aṅgula entsprechend kleiner, so dass 28 aṅgula der Wage = 24 gewöhnlichen aṅgula sind? Mit solch einem dünnen, natürlich mit dem dünnen Rücken nach oben schauenden Wagbalken kann man auf jeden Fall nur leichte Sachen wägen.

A5 Kārayeta caturhastāṃ samāṃ lakṣaṇalakṣitām \ tulāṃ kāṣṭhamayāṃ rājā śikyaprāntāvalambinīm. Jolly, Quotation from N. VI, 24. Da heißt sama ebenmäßig und glatt.

A6 Nāndī = svastika haben wir wohl auch in Viṣ. LXIII, 29, wo eine Menge Dinge aufgezählt wird, die der Hausvater anschauen soll, ehe er auf eine Reise geht. Darunter auch nāndyāvarta. Nandap. versteht nun zunächst die Stelle dahin, dass der Mann auf seiner Reise all die genannten Personen und Sachen nach rechts umwandeln oder rechts liegen lassen solle. Das wäre bei den meisten unmöglich. Sodann sagt der Text einfach: »Nachdem er diese angeschaut hat, breche er auf.« Nandap. sieht nun in nāndyāvarta »eine Art Königspalast«. Āvarta wird aber Haarwirbel bedeuten. Solche am Leib des Menschen spenden Glück, und an Pferden sind sie als segenbringend schon aus dem Nalalied bekannt. Siehe auch Śiśup. V, 4 und Mall. dazu, sowie die langen Ausführungen in Śukran. IV, 7, 154ff. Kein Wunder da, dass Śiva auch Śatāvarta heißt: »der mit den hundert Haarwirbeln« (MBh. XII, 284, 77). Freilich könnte nāndyāvarta (nandyāvarta) auch die so benamste Figur oder ein Gegenstand von dieser Gestalt sein. Siehe MBh. VII, 82, 20. vgl. auch die svastika-Tempel (prāsāda!) in Śukran. IV, 4, 143.

A7 Hinter »innen drin« füge ein: Ob aber nur für diese? Die Hauptsache ist doch wohl einfach und nach dem natürlichen Verständnis des Sanskritausdrucks so: Ein prastha-Maß, das ja vier kuḍumba halten soll, wird von aller Anfang so gemacht, dass nur drei kuḍumba hineingehen, wenn man das Messgerät ebenmäßig mit dem Borde voll macht. Das vierte kuḍumba muss oben darauf getürmt werden. Besonders bei Körnerfrüchten ergibt sich damit eine große Ungenauigkeit, denn bestimmte Arten kann man bedeutend höher aufhäufen als andere. Vergleichen wir bei uns z.B. Weizen und Hafer. Wurden nun auch für diese Messgefäße »mit der Häufung innen« darin gebraucht und dann glatt gestrichen, wie ich angenommen habe? Aus Kauṭ. können wir kein Licht bekommen. Schließen aber dürfen wir wohl folgendermaßen: Blumen, Obst, Getreidehülsen, Kohlen und Kalk gestatten eine besonders hohe Aufhäufung. Da lacht dem Inder das Herz und er tut nun flugs doppelt so viel wie sonst oben darauf. Wird er da seine ja auch auf geistigem Gebiet so ungezügelte Auftürmungslust bezwingen und z.B. bei Getreide glatt abstreichen können? Kaum. Warum aber dann auch bei Flüssigkeiten, die sich doch überhaupt zu keiner Aufhäufung hergeben, sogar die doppelte? Vieles Unbegreifliche gibt es auf Erden, das Unbegreiflichste ist der Mensch.

A8 Wegen der śikhāvṛddhi vgl. auch G. XII, 35 und Bühlers Anmerkungen dazu (SBE. II, S. 240). Kātyāyanas und Haradattas Erklärungen scheinen mir ebenfalls besser zu »Aufhäufungszins« zu stimmen. Gemeint ist mit dem »Auftürmungszins« wohl der aufs Kapital geschlagene Zins, den auch Kauṭ. als ungesetzlich ansieht (174, 10f.; Übers. 275, 6ff.).

A9 Kommt dann daher das dunkle nīhāra in Vas. XIX, 14 und ist dies = nirhāra »Herausnahme«, dann »Eichung« und endlich »Abgabe an den Eichmeister«? Auf jeden Fall scheint die amtliche Beglaubigung durch punching in Altindien sehr gewöhnlich gewesen zu sein, da sie ja bei den ältesten einheimischen Münzen geschah und diese deshalb »punch- marked« heißen. S. Rapson, Indian Coins §§ 5, 46, 129. Aber auch da haben wir keine Durchlochung, sondern eine Eindrückung, den Abdruck eines dhvaja oder Wahrzeichens der hohen Familie oder der Macht."

[Quelle: Kauṭilya: Das altindische Buch vom Welt- und Staatsleben : das Arthaśāstra des Kauṭilya / [aus dem Sanskrit übersetzt und mit Einleitung und Anmerkungen versehen von] Johann Jakob Meyer [1870-1939]. -- Leipzig, 1926. -- Digitale Ausgabe in: Asiatische Philosophie. -- 1 CD-ROM. -- Berlin: Directmedia, 2003. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 94). -- S. 158- 162.]

| 86a./b. mānaṃ tulāṅguli-prasthair guñjāḥ pañcādyamāṣakaḥ मानं तुलाङ्गुलि-प्रस्थैर् गुञ्जाः पञ्चाद्यमाषकः ।८६ क। Maß (māna n.) gibt es nach

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Of three sorts. By weight, measure of length, and measure of capacity."

तुला - tulā f.: Wage, Gewicht

Abb.: तुला । ca. 1825

[Bildquelle: The San Diego Museum of Art Collection. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/thesandiegomuseumofartcollection/6125146422/.

-- Zugriff am 2011-09-21. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: तुला । Madurai - மதுரை, Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: Patrik M. Loeff. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/bupia/2352020192/. - Zugriff am 2011-09-19.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

अ

ङ्गुलि - aṅguli f.: Finger, Daumenbreite (d.h. Länge)

Abb.: अङ्गुलिः । 1-Rupee Münze, Indien

[Bildquelle: blind dayze. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/blinddayze/5068327501/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-19. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

5. yava-udarair aṅgulam aṣṭa-saṃkhyais hasto 'ṅgulaiḥ ṣaṣ-guṇitaiś caturbhiḥ ।

hastaiś caturbhir bhavatīha daṇḍaḥ krośaḥ sahasra-dvitayena teṣām ॥

6. syāt yojanam krośa-catuṣṭayena tathā karāṇāṃ daśakena vaṃśaḥ ।

nivartanaṃ %viṃśati-vaṃśa-saṃkhyaiḥ kṣetraṃ caturbhiś ca bhujaiṛ nibaddham ॥5—6. Eight breadths of a barley-corn3 are here a finger ; four times six fingers, a cubit ;4 four cubits, a staff;5 and a krośa contains two thousand of these ; and a yojana, four krośas.

So a bambu pole consists of ten cubits ; and a field (or plane figure) bounded by four sides, measuring twenty bambu poles, is a nivartana.6

3 Eight barley-corns (yava) by breadth, or three grains of rice by length, are equal to one finger (aṅgula). Gaṇ.

4 Hasta, kara and synonyma of hand or fore arm. According to the commentator Gaṇeś'a, this intends the practical cubit as received by artisans, and vulgarly called gaj [or gaz]. It is nearer to the yard than to the true cubit : but the commentator seems to have no sufficient ground for so enlarging the cubit.

5 Daṇḍa, a staff: directed to be cut nearly of man's height. Manu, 2. 46,

6 A superficial measure or area containing 400 square poles. Sur."[Quelle: Bhāskara <ಭಾಸ್ಕರ> <1114–1185>: Līlāvatī. -- Übersetzt in: Algebra with arithmetic and mensuration : from the Sanskrit of Brahmagupta and Bhāskara / translated by Henry Thomas Colebrooke <1765 - 1837>. -- London : Murray, 1817. -- S. 2f.]

"The linear measure unit of India is generally the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger of a tall man. This length is known as the Hat'h, Hid., Malum, Tam., Mora, Tel., and averages 19½ inches. It is always translated cubit, though invariably exceeding the English cubit of 18 inches by 1½ or 2 inches. In the Southern Carnatic, the adi or length of a tall man's foot is in use, and averages 10¼ inches.

Guz (ﮔﺰ).—Akbar, after very considerable inquiry, introduced as the only legal measure, what is called the Ilahi guz. The Ayin Akbari informs us that this was taken as the mean of three chief guz then existing, the smallest about 28 inches, and the Ilahi guz between 33 and 34 inches. Mr. Duncan, after prolonged inquiry, estimated it at 33.6 inches, while others have valued it from 33 to 34.25 inches; a mean of these is 33.75 inches. Jervis thinks it was exactly 33.5 inches. Jonathan Duncan employed, when engaged in 'settling' the N.W. Provinces, a guz of 33½ inches. In the coast districts of the west, the most common guz is that of about 28 inches. In other parts there is a group whose average is about 39 inches. Frequently two or more of these are present in one locality for different transactions. Merchants will buy by the guz of 34 inches, and sell by that of 30 ; or silk will be measured by one, cloth (cotton or woollen) by another, while carpenters and bricklayers will use each a distinct measure. For instance, cotton cloth in Surat is measured by the guz of 27.8 inches, silk and other valuable stuffs by the guz of 34.7 inches, while the carpenter employs a guz of 27.2 inches. At Juanpur, the carpenter values his guz at 30 inches, the tailor estimates his at 34 inches, while the cloth seller employs one of 40 inches. The muslin seller at Farrakhabad uses a guz of 33¾ inches, the cloth seller one of 34 inches, while the seller of silk for turbands and full-dress coats uses no other than 38¼ inches. Similar cases might be adduced in infinite abundance. Wherever the cubit varies, the guz follows, usually in the proportion of 12 to 7, though this is by no means an invariable rule.

The guz in the Madras Presidency is from 26 to 39 inches. It is, however, very much superseded by the English yard measure. In the districts of Madura and Tinnevelly, the tutchakole or artificer's stick is 33 English inches.

In the south of India the guz is subdivided into 24 ungulum, each of which, taking the Tanjore guz of 33½ inches, is 1 4/10 of an English inch. The term ungulum in Tamil signifies the thumb, and in the above measure it is the distance from the thumb joint to the tip of the nail. This unguium is considered equal to 2 virrul kuddei, or finger-tip breadths.

The term ungulum is, however, sometimes used to mean a thumb-breadth, and is then the same as the virrul kuddei or finger-breadth or digit, or the 24th part of a cubit (about 0.82 inch), according to the following table :

- 4 finger-breadths = 1 palm.

- 12 finger-breadths = 1 span.

- 24 finger-breadths = 1 cubit.

- 4 cubits = 1 fathom.

The tutcha-muluvi or artificer's cubit (double) of Trichinopoly is 33 inches, or the same as the Tinnevelly tutcha-kolv, and is subdivided into 24 ungulum.

The bam, translated fathom, in Salem and Coimbatore averages 6 feet 4¼ inches, and in Guntur 6 feet 6 3/10 inches. It is generally, but not always, subdivided into 4 cubits. The bam or fathom is also used by native seamen on the lead line.

For distances of greater length, there is no defined measure in Southern India. A nali-vulli in Tamil is derried from Vulli, a road or way, and Nali, a period of time, which is the 60th part of the 24 hours, or 24 English minutes, generally known as an 'Indian hour.' The distance that is usually walked in this time is called a nalivulli, and is about 1½ English miles or somewhat less. Seven nali-vulli make a kadum of about 10 miles.

The cos is generally considered 2 English miles, but, according to Colebroke, as follows :

- 4 cubits = 1 danda or staff.

- 2000 danda = 1 cos.

Taking the cubit at 19½ inches, the cos would be 2.46 miles.

Hat'h, in the linear systems of India, is the cubit or human forearm ; and in oriental countries, as well as in the west, this unit is divided into two spans and 24 finger-breadths. Under the Hindu princes, the hat'h (in Sanskrit, hasta) was equal to two vitesti or spans, and to 24 angul (angula). The angul, finger, is divided into 8 jau (Sanskrit, yava) or barley-corns, 4 hat'h or cubits = 1 danda or staff ; 2000 danda make 1 krosa or cos, which by this estimation should be 4000 yards English, or 2¼ miles. The Lilavati states that 10 hat'h make one bans or bamboo, and 20 bans in length and breadth = 1 niranga of arable land. Natives of India, in speaking of the hat'h or cubit, allude to the natural human measure of 18 inches, more or less, and it is practically used in measuring off cloths, ribbons, etc., and in taking the draught of water of a boat. In many places, also, in Bengal and in Southern India, the English cubit has been adopted as of the same value as the native measure. [...]

Jureeb, Pers., is a measuring chain or rope. Before Akbar's time it was a rope, but he directed it should be made of bamboo with iron joints, as the rope was subject to the influence of the weather. European surveyors use a chain. A jureeb contains 60 guz or 20 gant'ha, and, is the standard measurement of the upper provinces of India, is equal to 5 chains of 11 yards, each chain being equal to 4 gant'ha. A square of one jureeb is a bigha (बीघा). Till the new system of survey was established, it was usual to measure lands paying revenue to Govenunent with only 18 knots of the jureeb, which was effected by bringing two knots over the shoulder of the measurer to his waist Rent-free land was measured with the entire jureeb of 20 knots."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 3. -- 1885. -- S. 1059.]

| 86a./b.

mānaṃ tulāṅguli-prasthair guñjāḥ

pañcādyamāṣakaḥ मानं तुलाङ्गुलि-प्रस्थैर् गुञ्जाः पञ्चाद्यमाषकः ।८६ क। Funf गुञ्ज - guñjā f.: Abrus precatorius L. 1767 - Paternostererbse - Indian Licorice, sind ein आद्यमाषक - ādyamāṣaka m.: Ādyamāṣaka |

Colebrooke (1807): "A Māṣa. Equal to five rettis or seeds of the abrus precatorius."

3. tulyā yavābhyāṃ kathitātra guñjā vallas tri-guñjo dharaṇaṃ ca te 'ṣṭau ।

gadyāṇakas tad-dvayam indra-tulyair vallais tathaiko ghaṭakaḥ pradiṣṭaḥ ॥

4. daśārdha-guñjaṃ pravadanti māṣam māṣa-āhvayaiḥ ṣoḍaśabhiś ca karṣam ।

karṣaiś caturbhiś ca palaṃ tulā-jñāḥ karṣaṃ suvarṇasya suvarṇa-saṃjñam ॥"3. A guñja1 (or seed of Abrus) is reckoned equal to two barley-corns; a valla. to two guñjas; and eight of these are a dhāraṇa; two of which make a gadyāṇaka. In this manner one ghaṭaka (oder: dhātaka) is composed of fourteen vallas.

4. Half ten guñjas are called a māṣa2, by such as are conversant with the use of the balance: a a karṣa contains sixteen of what are termed māṣas; a pala, four karṣas. A katṣa of gold is named suvarṇa.

1 A seed of Abrus precatorius: black or red; the one called kṛṣṇala; the other rakti, raktikā or rattikā; whence Hind. ratti.

2 Physicians reckon seven gañjas to the māṣa; lawyers, seven and a half. The same weight is intended; and the difference of description arises only from counting the heavier or lighter seeds of Abrus: in like manner the earth is the same, whether rated 3300 yojanas; or with the Śiromaṇi, 4967; or according to others, 6522. Gaṇ."

[Quelle: Bhāskara <ಭಾಸ್ಕರ> <1114–1185>: Līlāvatī. -- Übersetzt in: Algebra with arithmetic and mensuration : from the Sanskrit of Brahmagupta and Bhāskara / translated by Henry Thomas Colebrooke <1765 - 1837>. -- London : Murray, 1817. -- S. 2.]

गुञ्ज - guñjā f.: Abrus precatorius L. 1767 - Paternostererbse - Indian Licorice

Abb.: गुञ्जाः । Abrus precatorius L. 1767 - Paternostererbse -

Indian Licorice

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

Abb.: गुञ्जे । Abrus precatorius L. 1767 - Paternostererbse -

Indian Licorice, Hawaii

[Bildquelle: Forest & Kim Starr. --

http://www.hear.org/starr/images/image/?q=031108-3196&o=plants. -- Zugriff

am 2011-09-19. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

sind ein आद्यमाषक - ādyamāṣaka m.: Ādyamāṣaka

माष - māṣa m.: Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper 1956 - Urdbohne - Black Gram

Abb.: माष - māṣa m.: Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper 1956 - Urdbohne - Black

Gram

[Bildquelle: Tracey Slotta @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

"It is reasonable to infer, as a general rule, that all schemes of weights devised by isolated peoples, developing their own social laws, should primarily be based upon some readily accessible unit of limited proportions, rather than upon any higher measure of weight which advancing civilization and authoritative legislation might impose upon the normal datum. Such a metric test was found ready to men's hands in India, in the seed of the Wild Licorice (Abrus precatorius), a plant whose habitat was as extended as its produce was uniform and comparatively exempt from desiccation,—advantages which from immemorial time have secured for the local rati a representative place amid the adjuncts of the goldsmith's and money-changer's scales. The later Sanskrit writers freely conceded its claim to the title of "Balance or Scales seed" (तुलाबीज tulābīja), and the great Akbar, in the sixteenth century, still continued to recognize Its position, under one of its ancient names, in the "red" (surkh) : for all reductions upon provincial payments of revenue, though, having felt the inconvenience of so inconclusive a test in more exact mint analyses, he ordained that the State trial weights should henceforth be kept in pieces of cut agate.

After the rati, in ascending order, appears the māṣa, which, in its acceptance far and near, beyond its Indian home, may almost claim the title of a second unit, if not that of a separate standard ; as such, indeed, its name has come to figure in the Indigenous speech as "an elementary weight." In its static sense this measure also owes its parentage to the vegetable world, in the form of a tangible seed, whose properties of permanence are shared with the associate rati, in a hard compact texture and a protecting, glazed skin. Unlike the wild rati, however, this is a cultivated bean, which has hitherto been identified with the Phaseolus radiatus ; but none of the seeds of this plant, even the most highly developed, at all approach the required weight : so that the representatives of the true Māsh i Hindī tad to be sought among other varieties, when the prototype was readily traced in the Phaseolus vulgaris, which has disappeared from the north-west of India, to be preserved in the agriculture of the south, where, like other congenial products of the soil, it has the advantage in point of growth over its counterpart of the higher latitude, and even discloses a weight slightly in excess of that demanded by the metallic silver māṣa.

The māṣa is concurrently mentioned as a food grain in Manu (ix. 39); and Prof. Weber remarks, that the name, in its metric sense, is not found in any texts authentically Vedic, though it seems that the term, as applied to pulse, occurs in the Atharva Veda."

[Quelle: Thomas, Edward <1813 - 1886>: Ancient Indian weights. -- London : Trübner, 1874. -- (Marsden's numismata orientalia. New ed. ; part I). -- S. 10f.]

| 86c./d. te ṣoḍaśākṣaḥ karṣo 'strī palaṃ karṣa-catuṣṭayam ते षोडशाक्षः कर्षो ऽस्त्री पलं कर्ष-चतुष्टयम् ।८६ ख। 16 Ādyamāṣaka sind

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Sixteen times as much."

| 86c./d. te ṣoḍaśākṣaḥ karṣo 'strī

palaṃ karṣa-catuṣṭayam ते षोडशाक्षः कर्षो ऽस्त्री पलं कर्ष-चतुष्टयम् ।८६ ख। 4 Karṣa sind 1 पल - pala n.: Pala |

Colebrooke (1807): "Four times the last."

| 87a./b. suvarṇa-vistau hemno 'kṣe

kuruvistas tu tat-pale सुवर्ण-विस्तौ हेम्नो ऽक्षे कुरुविस्तस् तु तत्पले ।८७ क। Ein Akṣa (Karṣa) Gold heißt:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A karṣa of gold."

| 87a./b.

suvarṇa-vistau hemno 'kṣe

kuruvistas tu tat-pale सुवर्ण-विस्तौ हेम्नो ऽक्षे कुरुविस्तस् तु तत्पले ।८७ क। Ein Pala Gold heißt कुरुविस्त - kuruvista m.: Kurusvista (Kuru-Vista) |

Colebrooke (1807): "A pala of gold."

| 87c./d. tulā striyāṃ pala-śataṃ bhāraḥ syād viṃśatis tulāḥ तुला स्त्रियां पल-शतं भारः स्याद् विंशतिस् तुलाः ।८७ ख। 100 Pala sind 1 तु्ला - tulā f.: Tulā ("Waage") |

Colebrooke (1807): "100 Palas."

Abb.: तुला । Silber Rupee der East India Company, Madras Presidency,

in britischer Zeit das faktische Standardgewicht 1 Tola (تولا

l तोला), 1817/1835

[Bildquelle: Jungpionier / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

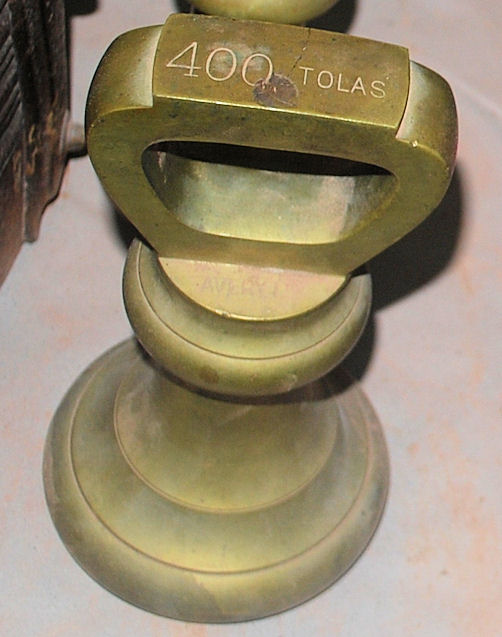

Abb.: तुला । 400 Tolas (

| 87c./d. tulā striyāṃ pala-śataṃ

bhāraḥ syād viṃśatis tulāḥ तुला स्त्रियां पल-शतं भारः स्याद् विंशतिस् तुलाः ।८७ ख। 20 Tulā sind 1 भार - bhāra m.: Bhāra ("Last") |

Colebrooke (1807): "Twenty times as much."

| 88a./b. ācitaṃ daśa bhārāḥ syuḥ

śākaṭo bhāra ācitaḥ आचितं दश भाराः स्युः शाकटो भार आचितः ।८८ क। 10 Bhāra sind 1 आचित - ācita n.: Ācita ("Angehäuftes") 1 Ācita ist eine Wagenladung (śākaṭa bhāra) |

Colebrooke (1807): "Ten times the last. "A cartload.""

| 88c./d. kārṣāpaṇaḥ kārṣikaḥ syāt kārṣike tāmrike paṇaḥ कार्षापणः कार्षिकः स्यात् कार्षिके ताम्रिके पनः ।८८ ख। [Bezeichnungen für einen Karṣa:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A karṣa of silver. Same with पुराणः, equivalent to 16 Panas of cowries."

कार्षापण - kāṛṣāpaṇa m.: Kārṣāpana ("Münze vom Gewicht eines Karṣa (in der Regel aus Kupfer)" PW)

Abb.: कार्षापणः । Kārṣāpaṇa aus Blei, 14,30 g, 27 mm Ø, Śātavāhana (శాతవాహన),

125/345 n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

| 88c./d. kārṣāpaṇaḥ kārṣikaḥ syāt

kārṣike tāmrike paṇaḥ कार्षापणः कार्षिकः स्यात् कार्षिके ताम्रिके पनः ।८८ ख। Ein Kārṣika Kupfer heißt पण - paṇa m.: Paṇa ("Wetteinsatz") |

Colebrooke (1807): "A pana of copper. Equivalent to 80 cowries."

| 89a./b. astriyām āḍhaka-droṇau

khārī vāho nikuñcakaḥ 89c./d. kuḍavaḥ prastha ityādyāḥ parimāṇārthakāḥ pṛthak

अस्त्रियाम् आढक-द्रोणौ खारी वाहो निकुञ्चकः ।८९ क। Hohlmaße sind:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Various measures of capacity. Severally, viz.

4 āḍhakas = 1 droṇa ; and

16 droṇas = 1 khārī. Also

20 droṇas = 1 kumbha ; and

10 khārīs = 1 vāha.

Some state

1/4 khārī = 1 mānī.

1/4 mānī = 1 droṇa.

1/4 droṇa = 1 āḍhaka.

1/4 āḍhaka = 1 prastha.

1/4 prastha = 1 kuḍava.

1/4 kuḍava = 1 nikuñcaka."

Abb.: परिमाणम् । Abmessen von Milch zum Verkauf, Indien

[Bildquelle: ILRI. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ilri/3971663762/. -- Zugriff am 2011-09-21.

--

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

share alike)]

7. hasta-unmitair vistṛti-dairghya-piṇḍair yad dvādaśāsraṃ ghana-hasta-saṃjñam |

dhānyādike yat ghana-hasta-mānaṃ śāstroditā māgadha-khārikā sā ||

8. droṇas tu khāryāḥ khalu ṣoḍaśāṃśaḥ syāt āḍhako droṇa-caturtha-bhāgaḥ |

prasthaś caturthāṃśa ihāḍhakasya prasthāṅghrir ādyair kuḍavaḥ pradiṣṭaḥ ||

(9.pādona-gadyāṇaka-tulya-ṭaṅkair dvi-sapta-tulyaiḥ kathito 'tra seraḥ |

maṇābhidhānaṃ kha-yugaiś ca serair dhānyādi-taulyeṣu turuṣka-saṃjñā ||)"7. A cube,7 which in length, breadth and thickness measures a cubit, is termed a solid cubit : and, in the meting of corn and the like, a measure, which contains a solid cubit, is a khārī of Magadha1 as it is denominated in science.

8. A droṇa is the sixteenth part of a khārī; an āḍhaka is a quarter of a droṇa ; a prastha is a fourth part of an āḍhaka ; and a kuḍaba2 is by the ancients3 termed a quarter of a prastha.4

7 Dvādaśāsri, lit. dodecagon, but meaning a parallelopipedon ; the term asra, corner or angle, being here applied to the edge or line of incidence of two planes. See Caturveda on Brahmagupta, §6.

1 The country or province situated on the Śonabhadrā river. —Gaṇ. It is South Bihar. See, concerning other cārī measures, a note on § 236.

2 ' In the Kuṭapa, the depth is a finger and a half; the length and breadth, each, three.' Śrīdhara ācārya cited by Gaṅgād'hara and Sū'ryadāsa. 'The kuṭapa or kuḍaba is a wooden measure containing 13½ cubic aṅgulas ; the prastha, (four times as many) 54; the āḍhaka, 216; the droṇa, 864; the cārī, 13824.'—Gaṅg, and Sūr. See As. Res. vol. 5, p. 102.

3 By Śrīd'hara and the rest. Sūr.

4 Another stanza, (an eighth, on the subject of weights and measures,) occurs in one copy of the text; and that number is indicated in the Manorañjana. But the commentaries of Gaṇeśa and Sūryadāsa specify seven, and Gaṅgādhara alone expounds the additional stanza. It is therefore to be rejected as spurious, and interpolated : not being found in other copies of the text. The subject of it is the maṇa (maṇ) of forty setas (sēr) ; which, as a measure of corn by weight, is ascribed to the Turushcas or Muhammedans of India ; the people of Yavana-deśa, as the commentator terms them.

5 "The seta is here reckoned at twice seven taṅkas, each equal to three-fourths of a gadyānaka: and a maṇa, at forty setas. The name is in use among the Turushcas, for a weight of corn and like articles." See notes on § 97 and 236."

[Quelle: Bhāskara <ಭಾಸ್ಕರ> <1114–1185>: Līlāvatī. -- Übersetzt in: Algebra with arithmetic and mensuration : from the Sanskrit of Brahmagupta and Bhāskara / translated by Henry Thomas Colebrooke <1765 - 1837>. -- London : Murray, 1817. -- S. 2f.]

"Dry and Liquid Measures.—India does not, properly speaking, possess dry or liquid measures. When these are employed, they depend upon, and in fact represent, the seer (سیر) or man weight, and the value of a vessel of capacity rests solely on the weight contained in it. The mode in which this is effected for the dry measures of the south and west of India, is by taking an equal mixture of the principal grains, and forming a vessel to hold a given weight thereof, so as to obtain an average measure; sometimes salt is included amongst the ingredients. The maund and seer measures of capacity are supposed to represent the equivalents of a maund and seer weight, although it is evident, since no two articles have exactly the same proportionate bulk, that no two measures need correspond. In the absence of suitable standards of capacity, almost every article is sold by weight, even ghee, oil, and milk. Grain is sold either by weight or measure, but with an understood proportion between them ; thus in Madras the measure for paddy is exactly the bulk of a viss weight. There are, however, a few measures of a well-ascertained value, which appear to have been arranged in something like order around the cubic cubit. An old writer on arithmetic, Bhaskaracharya, states explicitly that a measure called karika was the cubic cubit or ghunuhustu. Above this was the cube of a double cubit, and ten times the half of this is the garce, a measure well known through all Southern India, and formerly universal ; so that the garce is 40 karika. The half of the karika is the parah. One-tenth part of the cubic cubit \a the mercal. In Western India there is the candy of 10 cubic cubits. The cube of one-fourth of a cubic cubit is the pyli. In Southern India there is the tūmi of four hundredths of the garce, and the paddacu or one-fifth of the cubic cubit ; while in the Telugu districts there is the pūti of two cubic cubits, and another tūmi one-tenth of one cubit. Turning northwards to Ganjam we find the burnum of two cubic cubits, and the nawty of one-tenth of a cubic cubit, and the tūm of one-fortieth of the same measure.

On the other side of India, in Bombay, there is the khundi, exactly corresponding with the garce. The cube of half the side of the garce, or the half of the cubic cubit, is the parah of the same value as in Southern India, while the cube of one-fourth the side of the parah is the seer. In Malwan, the khundi is greatly altered in value, and becomes ten cubic cubits, proving that there is an understood connection between the cubit and measures of capacity. In the same district is the parah of half the cubic cubit As an official recognition of the relation between measures of capacity and the cubit, it may be mentioned that when the Government of Bombay ordered that the measures for salt throughout the Konkan should be rendered uniform, it was resolved to employ a parah of exactly half a cubic cubit, estimated at 19.5 inches. Reducing the measures referred to into a table, we find the following in cubic cubits :

Madras garce 40 Malwan khundi 10 Puti or burnum, 2 Ghunuhustu 1 Mercal 1/16 Tumi 1/16 Nawty 1/16 Tum 1/40 We see here two kinds of division besides the ordinary one of halves and fourths.

- 10 mercab = 1 cubic cubit.

- 10 cubic cubit = 1 khundi.

- Cube of ¼ side of cubic cubit = pyli.

- Cube of ¼ side of cubic parah = seer.

If we compare the lengths assigned to the cubit in different parts of India, omitting one or two of the smallest and plainly diminished cubits, we shall find the average to be from 19.5 to 19.7 inches.

Trichinopoly is the only place where grain is said never to be sold by weight. The marcal (properly marakkal, from the Tamil) and parah are the commonest measures ; the latter is known throughout India. In Calcutta it is called ferrah, and is used in measuring lime, etc., which is still recorded, however, in the man weight. In its weights, Southern India retained, from the ancient metrology of the Hindus, most of the names and terms properly Hindu,

Throughout the Moghul empire, on the contrary, the seer and man were predominant. The word man, of Arabic or Hebrew origin, is used throughout Persia and Northern India, but it represents very different values in different places. Thus the man of Tabreez is only 6 1/3 lbs. avoir., while that of Palloda in Ahmadnaggur is 163¼ lbs.

The following is the scale of measures in use at Madras :

The Madras Revenue Board, on the 19th May 1883, furnished the revenue collectors with a statement, showing equivalents in Government seers of 80 tolas of local measures of different food-grains and of salt. The grains tested were four kinds of unhusked and husked rice, Oryza sativa; the horse-gram, Dolichos uniflorus; the jowari or cholum, Sorghum vulgare ; the bajri or cumboo, Penicillaria spicata ; the varagoo, Panicum miliaceum ; the ragi, Eleusine coracana ; the ulundu, Phaseolus muugo ; and wheat, Triticum aestivum.

Tūm.— In the Ganjam district, the assumed normal contents of the turn, in rice, ranged from 80 to 280 tolas, with measures of cubic capacity 64.88 to 231.82 inches.

Seven seer measures, in use in the Madras Presidency, some of them struck, some liberally or moderately heaped, the assumed normal contents ranged from 75 to 130 tolas, viz. 75, 78, 80, 86, 90, 92, 130.

The tavva of four taluks of Vizagapatam is 33 tolas.

The Bezwara mercal, liberally heaped, 260 tolas.

The adda of Gudivada in the Kistna district, 210 tolas.

The manilca and padi manika measure is in use in the Nellore and Kistna district, and liberally heaped contains from 106 to 200 tolas.

The measure in use in Bellary, Kumool, Cuddapah, Madras town, and Chingleput is of 75, 80, 114, 120, 128, 130, 132, 135, 144, 150, and 160 tolas ; and there is a half measure of 75 at Madarpak, and one of 64 at the Neilgherries.

The padi is in use in the Tamil districts, where there are seven quantities of 75, 86, 116, 133, 140, 144, and 150 tolas ; and from half padi of 65, 66-5, 70, and 72 tolas.

The nali of Cochin is of 43 tolas.

A garce is assumed to contain 3200 measures, the weight of a measure of each of the following grains being—rice, unhusked, 80 tolas ; do. husked, 120 ; Sorghum vulgare, wheat, and Eleusine coracana, each 111 ; Penicillaria spicata and Panicum miliaceum, each 102 ; Phaseolus mungo, 115; Dolichus uniflorus and salt, each 120.

The mercal of the Madras grain market is equal to eight Madras struck measures of 120 tolas each.

Seer (سیر).—The most common grain measure, and one which is to some extent known in almost every part of India, is the seer measure ; this is always understood to be a measure which, when heaped, will contain a seer weight of rice, or in some places, instead of rice, a mixture of the nine most common grains, known as the nou-daniam measurement. The nine grains used in the Madras Presidency are rice, chenna, culti, pessalu, minamalu, dholl, anamalu, gingelly oilseed, and wheat. As only heaped measure is recognised by native usage, it is evident that there is no rule as to the cubic contents of the measures used ; for vessels of very different cubic contents may contain the same when heaped, in consequence of having different diameters. It is on this account that the values given to Indian measures, in such tables as those of Major Jervis, or Dr. Kelly in his Cambist, being founded on the gauged cubic contents, do not represent the true quantities."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 3. -- 1885. -- S. 1061f.]

| 90a./b. pādas turīyo bhāgaḥ syād aṃśa-bhāgau tu vaṇṭake पादस् तुरीयो भागः स्याद् अंश-भागौ तु वण्टके ।९० क। Der vierte Teil heißt पाद - pāda m.: Fuß, Viertel (von vierbeinigen Tieren abgeleitet) |

Colebrooke (1807): "A quarter."

| 90a./b. pādas turīyo bhāgaḥ syād

aṃśa-bhāgau tu vaṇṭake पादस् तुरीयो भागः स्याद् अंश-भागौ तु वण्टके ।९० क। Bezeichnungen für Teil (वण्टक - vaṇṭaka m.: Teil):

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A part, share, or portion."

Zu Vaiśyavarga - Vers 90c - 112b (Handel III: Handelsgüter I: Besitz, Juwelen, Metalle)