|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 15. vaiśyavargaḥ (Über Vaiśyas). -- 12. Vers 90c - 99: Handel III: Handelsgüter I: Besitz, Juwelen, Metalle. -- Fassung vom 2011-09-29. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa7/amara215l.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-09-28

Überarbeitungen: 2011-09-29 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener,

gut ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener,

gut ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

| 90c./d. dravyaṃ vittaṃ svāpateyaṃ riktham ṛkthaṃ dhanaṃ vasu द्रव्यं वित्तं स्वापतेयं रिक्थम् ऋक्थं धनं वसु ।९० ख। [Bezeichnungen für Habe:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Substance, thing, or wealth."

द्रव्य - dravya n.: Gegenstand, Ding, Habe, Besitz

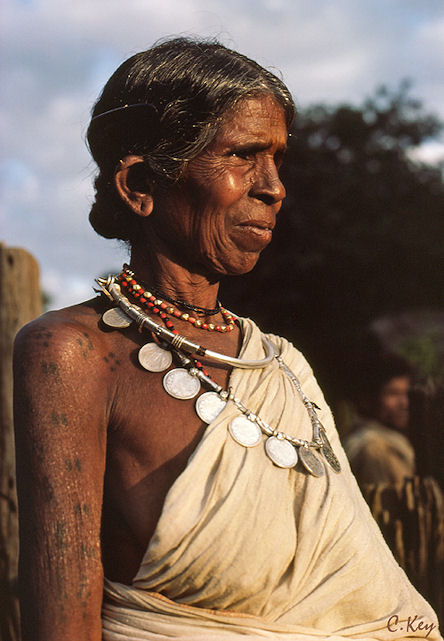

Abb.: द्रव्यम् । Narayanpur - नारायणपुर,

Chhattisgarh

[Bildquelle: Collin Key. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/collin_key/4597549269/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-22. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

वित्त - vitta n.: Fund, Besitz, Habe, Vermögen

Abb.: वित्तम् । Ajmer - अजमेर,

Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: Vincent Desjardins. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/endymion120/4874320093/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-22. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

स्वापतेय - svāpateya n.: Eigentum

Abb.: स्वापतेयम् । Dorf-Arbeiterin, Diu - દીવ; Daman and Diu

[Bildquelle: Meena Kadri. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/meanestindian/105210891/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-21. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

रिक्थ - riktha n., ऋक्थ - ṛktha n.: Nachlass, Erbe, Vermögen, Besitz

Abb.: रिक्थम् । Indien

[Bildquelle: World Bank / Curt Carnemark. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/worldbank/2243757037/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-22. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

धन - dhana n.: Beute, Gewinn, Kampfpreis, Reichtum, Geld

Abb.: धनम् ।

[Bildquelle: Virtualage / Wikipedia. -- Fair use]

वसु - vasu n.: Gut, Reichtum, Besitz

Abb.: वसु । Lakṣmī die Göttin des Reichtums, Pūjā an Śarad-pūrṇimā

[Bildquelle: Saugat22 / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

| 91a./b. hiraṇyaṃ draviṇaṃ dyumnam artha-rai-vibhavā api हिरण्यं द्रविणं द्युम्नम् अर्थ-रै-विभवा अपि ।९१ क। [Bezeichnungen für Gold:]

|

हिरण्य - hiraṇya n.: Gold, Reichtum

Abb.: हिरण्यम् । Mumbai - मुंबई, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Akshay Mahajan. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/lecercle/359226965/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-22. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

द्रविण - draviṇa n.: bewegliches Gut, Reichtum, Vermögen

Abb.: द्रविणम् । Adeliger mit Chauffeur, Indien, ca. 1900

[Bildquelle: Raja Lala Deen Dayal (1844 - 1905)]

द्युम्न - dyumna n.: Glanz, Kraft

Abb.: द्युम्नम् । Pūjā für Lakṣmī die Göttin des Reichtums, Mumbai - मुंबई,

Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Ben Piven. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/piven/1946901109/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-21. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

अर्थ - artha m: Zweck, Nutzen, Vermögen

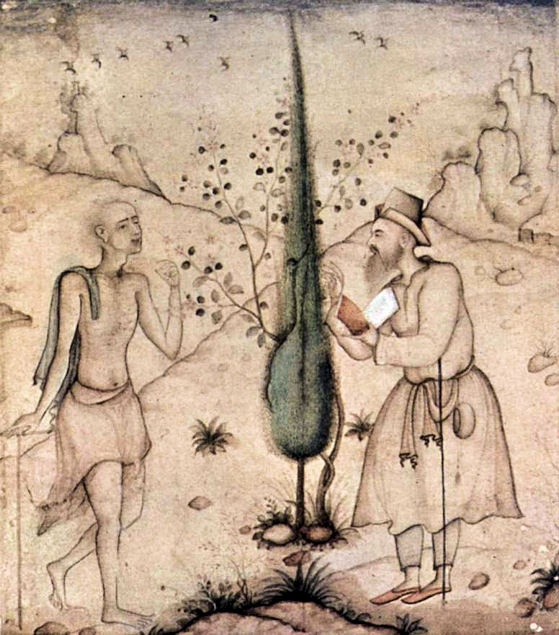

Abb.: अर्थश्च मोक्षश्च । Kaufmann und Asket, ca. 1600

रै - rai m.: Reichtum, Habe, Besitz

Abb.: राः । Bashir Bagh Palace, Hyderabad -

حیدرآباد, (heute:) Andhra Pradesh, um 1890

[Bildquelle: Raja Lala Deen Dayal (1844 - 1905)]

विभव - vibhava m.: Macht, Reichtum

Abb.: विभवः । Das Fotostudio von Raja Deen Dayal & Sons, Hyderabad -

حیدرآباد, (heute:] Andhra Pradesh, um 1890

[Bildquelle: Raja Lala Deen Dayal (1844 - 1905)]

| 91c./d. syāt kośaś ca hiraṇyaṃ ca hema-rūpye kṛtākṛte स्यात् कोशश् च हिरण्यं च हेम-रूप्ये कृताकृते ।९१ ख। Verarbeitetes und unverarbeitetes Gold (heman) und Silber (rūpya) heißen:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Wrought and unwrought gold, &c."

कोश - kośa m.: Behälter, Schatzbehälter, Schatz, verarbeitetes und unverarbeitetes Gold und Silber

Abb.: कोशः । Bijapur

[Bildquelle: Peter Elman. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/pepepe/4462965045/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-27. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

हिरण्य - hiraṇya n.: Gold, Reichtum, verarbeitetes und unverarbeitetes Gold und Silber

Abb.: हिरण्यम् । Indien

[Bildquelle: annemorgan71. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/23281382@N05/3504097838/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-27. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"MINERAL or inorganic medicines are generally described under five heads, namely.

- Rasa or mercury which forms a class by itself ;

- Uparasa or metallic ores and earths.,

- Dhātu or metals,

- Lavaṇa or salts, and

- Ratna or precious stones."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 23.]

"Dreizehntes Kapitel (31. Gegenstand). Der Goldaufseher in der Edelmetallschmiede [अक्षशालायां सुवर्णाध्यक्षः].

Der Goldaufseher soll für die Gold- und Silberbearbeitungen eine Edelmetallschmiede (akṣaśālā) errichten lassen mit vier Hallen und einer Türe und so, dass die einzelnen Werkstätten nicht zusammenhängen. Mitten an die Marktstraße soll er als königlichen Goldschmied einen kunstreichen, wohlgebornen und zuverlässigen Mann hinsetzen.

Gold (hat folgende Arten): das vom Flusse Jambū, das vom Flusse Śatakumbhā, das vom Goldland Hāṭaka, das vom Fluss (oder: Berg) Veṇu, das in Śṛiṅgiśukti entstandne; (oder auch:) gediegen vorgefundnes, Waschgold und Berggold.1

Lotosstaubfadenfarbig, geschmeidig, glatt, lange tönend und leuchtend ist das beste, rotgelb das mittlere, rot das schlechteste.

Von den besten Arten ist das unreine2 weißlich gelb oder weiß. Das, wodurch es unrein ist, soll er mit der vierfachen Menge Blei wegläutern. Wird es durch den Bleizusatz brüchig, so soll er es zusammen mit trocknen Haufen3 im Gebläse schmelzen. Wird es infolge seiner Sprödheit brüchig, dann soll er es in Sesamöl und Kuhmist eingießen.4

Zeigt sich das Berggold (wörtlich das Bergwerksgold, d.h. das aus Berggestein gewonnene) infolge des Bleizusatzes brüchig, dann soll er es in durchhitzte Blätter (Platten) verwandeln und diese auf Holzblöcken klopfen.5 Oder er durchsetze es mit einer Paste aus der Wurzelknolle der kandālī und des vajra.

Silber stammt vom Berge Tuttha, vom Gauḍaland (in Assam), vom Berg Kambu und vom Bergwerk Cakravāla. Das weiße, glatte und geschmeidige ist das beste. Im gegenteiligen Fall und wenn es zerbirst, ist es fehlerhaft. Solches läutre er durch ein Viertel so viel Blei. Kommen Wülstchen (Blasen) zum Vorschein, ist es hell, leuchtend und an Farbe wie saure Milch, dann ist es rein.6

Ein suvarṇa (von 16 māṣa) aus reinem gelbwurzfarbigem Gold bildet den Feingehalt.7 Sechzehn (Minder)gehalte ergibt es, indem von da aus immer um eine weitre kākaṇī Kupfer hineingetan wird bis zur Grenze von vier (māṣa Kupfer, also einem Viertel).8

Nachdem er zuerst das (zu prüfende) Gold über den Prüfstein gezogen hat, ziehe er das Mustergold darüber.9 Wenn sich der Strich als von gleicher Farbe erweist an den Stellen (des Probiersteins), die weder vertieft noch erhöht sind, dann hat es die Goldprobe bestanden.10 Wird (vom Prüfenden beim Strichziehen) stark aufgedrückt oder nur leise darüber hingefahren,11 oder unter den Fingernägeln hervor gelber Ocker draufgepulvert, dann wisse man, dass Betrug vorliegt. Wenn man die Fingerspitzen mit Zinnober oder mit Eisenvitriol, die man in Rindsurin gelöst hat, beschmiert und damit Gold berührt wird es weiß.

Der lotosstaubfadenhafte, glatte, weiche und leuchtende (von Gold hervorgerufene) Strich12 auf dem Probierstreifen ist der vorzüglichste.

Der Stein vom Kalingaland oder vom Flusse Taptī, der die Farbe von Phaseolus Mungo hat, ist der beste Probierstein. Einer, der die Abfärbung (an allen Stellen) gleich aufnimmt, ist vorteilhaft für Kauf und Verkauf (von Gold). Einer, der der Elefantenhaut gleicht (d.h. ebenso rauh und hart ist), in seiner Färbung etwas Grünliches hat und für die Abfärbung empfänglich ist, der ist vorteilhaft für den Verkäufer. Ein harter, unebner und in der Farbe ungleicher ist für die Abfärbung unempfänglich, (also) vorteilhaft für den Käufer.13

Ist ein abgebrochnes Stück Gold an der Bruchstelle schlüpfrig anzufühlen, von gleichmäßiger Farbe, glatt, geschmeidig und leuchtend, so ist das ein vorzüglichstes. Erweist es sich bei der Erhitzung (tāpe) innen und außen als gleich im Aussehen, als lotosstaubfadenfarbig oder kuraṇḍablütenfarbig,14 dann ist es vorzüglichst. Zeigt es sich braun oder blau, dann ist es unrein.

Von Wagen und Gewichtssteinen werden wir im Kapitel vom Aufseher über Maß und Gewicht reden (Buch II, Kap. 19). Nach diesen Angaben soll er Silber und Gold verabfolgen und an sich nehmen.15

In die Edelmetallschmiede darf kein Unbefugter gehen. Wer doch dahingeht, soll vernichtet werden.16

Ein Angestellter aber, der mit Silber oder Gold (die Goldschmiede betritt), soll dessen verlustig gehen.

Die Handwerker in durchlöcherten Goldkügelchen, in Goldgeräten und in Goldschmuck,17 die Bläser (d.h. Schmelzer), die Hilfsarbeiter18 und die Reinmacher dürfen nur, nachdem ihre Kleider, Hände und geheimen Teile19 untersucht worden sind, hineinkommen und hinausgehen. All ihre Geräte und die von ihnen noch nicht vollendeten Arbeiten (prayoga) müssen an Ort und Stelle bleiben. Das Gold, das er empfangen hat, und die hergestellten Arbeiten soll er mitten im Bureau abgeben. Am Abend und am Morgen soll er alles mit dem Siegel des Herstellers und des Auftraggebers vorlegen.20

Einsetzen (kṣepaṇa), Schnursachen (guṇa) und Kleinarbeit (kṣudraka), das sind die verschiednen Arten von Goldschmiedearbeit. Einsetzen ist das Fassen von Glasperlen usw. (d.h. von Edelsteinen). Schnursachen sind die auf Faden gereihten Stücke.21 Kleinarbeit umfasst massive Dinge (wie Reife usw.), hohlräumige Gegenstände (wie Gefäße), sowie die Ziersachen, die mit durchlöcherten Kügelchen u. dgl. mehr versehen sind.

Beim Fassen von Edelsteinen wende er ein Fünftel auf die goldne Unterlage (kāñcana), ein Zehntel auf die festhaltende Einfassung (kaṭamāna).22 Silber, das mit einem Viertel so viel Kupfer gemischt ist, oder Gold, das mit einem Viertel Silber gemischt ist, heißt »hergerichtet« (saṃskṛitaka). Davor sei er auf der Hut.

Bei der Fassung von Edelsteinen zusammen mit durchlöcherten Kügelchen (mit »Tropfen«) sind drei Teile (der gesamten Goldmenge) Untergrund und zwei Teile Einfassung. Oder auch vier Teile Untergrund und drei Teile Einfassung.23

Beim Herstellen von Gefäßen u. dgl. mehr (tvaṣṭṛikarman) soll er ein Kupfergerät mit ebensoviel Gold überziehen (samyūhayet)A1.

Ein Silbergerät, sei es nun massiv (wie z.B. ein Ring) oder massiv-hohlräumig (wie Schüssel, Krug usw.) soll er mit halb so viel Gold (wie das Silber des Gefäßes usw. beträgt) überschmieren (avalepayet). Oder ein Viertel so viel Gold (wie die Silbermenge) zusammen mit geschmolznem oder pulverisiertem Sand und Zinnober möge er auftragen (vāsayet).24

Für Goldschmuck (tapanīya) nur das beste Gold.25

Feingold von vorzüglicher Farbe und Glut (surāga), zu gleichen Teilen mit Blei geläutert, in Form von durchhitzten Blättern ausgeglüht26 und mit Sindhererde (Steinsalz?) zum Aufkochen gebracht, gibt die Grundlage ab für Blau, Gelb, Weiß, Grün und die Farbe eines jungen Papageis. Und die verstärkte Form davon (tīkṣṇam asya) schimmert wie ein Pfauenhals und zeigt weiße Bruchstelle; es schillert sehr stark27 und ist gelb, wenn man es pulverisiert. Eine kākaṇī davon bildet den Farbstoff für einen suvarṇa.28

Feines Silber (tāra) oder nahezu reines (upaśuddha) wird viermal in Kupfervitriol mit (pulverisierten) Knochen, viermal in Kupfervitriol mit ebenso viel Blei (wie Kupfervitriol), viermal in trocknem Kupfervitriol, dreimal in kapāla, zweimal in Kuhmist, in dieser Weise siebenmal in Kupfervitriol geläutert und mit Sindhererde (Salzerde von Sindh; oder: mit Steinsalz?) aufgekocht – von diesem (Silber) wird dann je eine weitre kākaṇi weggenommen bis hinauf zu zwei māṣa. In Gold ist dazuzugeben. Darauf der Farbzusatz. So wird es Weißsilber (śvetatāra).29

Drei Teile geläutertes Gold, damit zweiunddreißig Teile Weißsilber zusammengeschmolzen, das wird eine rötlich weiße Legierung. (Mit ebensoviel) Kupfer (statt Gold) ergibt eine gelbe Legierung. Nachdem man geläutertes Gold (tapanīya) erhitzt hat, füge man ein Drittel30 Farbstoff dazu. Dann wird es gelbrot. Zwei Teile Weißsilber und ein Teil geläutertes Gold ergibt eine Legierung von der Farbe des Phaseolus Mungo. Wenn man es (wohl das Weißsilber) mit halb so viel Eisen31 bestreicht, wird es schwarz. Bestreicht man geläutertes Gold zwiefach mit anklebendem Goldsaft, dann bekommt es die Farbe von Papageienfedern.32

Unternimmt er dergleichen, dann mache er bei den verschiednen Färbungen (immer zuerst) eine Probe.33

Auch soll er sich auf die Behandlung34 von Eisen (tīkṣṇa) und Kupfer verstehen. Daher35 dann auch auf den Abfall bei den verschiednen Exemplaren von Diamanten, Edelsteinen, Perlen und Korallen und auf die erforderlichen Mengen (Material) bei der Herstellung von Gold- und Silberwaren.36

Die Vorzüge eines aus Gold gemachten Schmuckstücks (tapanīya) sind nach der Überlieferung diese: von gleichmäßiger Färbung und Glut, ein Teil genau wie der ihm entsprechende andre,37 die (dabei) verwendeten durchlöcherten Kügelchen nicht aneinanderklebend, solid, wohl poliert, unverfälscht,38 in sich zusammenstimmend, beim Tragen angenehm, geschmackvoll,39 glanzbegabt, ge fällig in der Form, ebenmäßig, das Gemüt und das Auge ergötzend.

Fußnoten

1 Nach den Indern: »vom Berg Śatakumbha«, und: »vom Bergwerk Hāṭaka. Śṛiṅgiśukti ist nach Gaṇ. ein Goldland. Könnte es heißen: aus der gehörnten Muschel entstanden«? Die Farbe soll bei den verschiedenen Arten immer verschieden sein. Man findet die Angaben bei Bhaṭṭ. und danach bei Sham. und Jolly. Jātarūpa von angeborener Gestalt oder Schönheit scheint gediegen vorgefundenes zu sein, rasaviddha »flüssigkeitdurchsetzt«, also wohl Waschgold. 315, 2 heißt rasaviddha giftdurchsetzt, vergiftet. Freilich haben wir ja schon vyadh, vedhana usw. als t. t. für das vom »Goldsaft« ausgehehende Durchdringen anderer Metalle kennen lernen, d.h. für deren Verwandeln in Gold. So muss man vielleicht rasaviddha nach 84, 2–4 und 10 verstehen und übersetzen: »durch Goldsaft erzeugtes.« Die ind. Lex. sagen ja, das Wort bedeute »künstliches Gold«. »Mit Quecksilber amalgamiert« (Sham: und Jolly) aber ist gewiss verkehrt. Trifft meine Übersetzung das Richtige, dann haben wir wieder die drei: bhūmidhātu, rasadhātu und prastaradhātu (60, 7; 81, 16). Ākarodgata wird auf jeden Fall = prastaradhātu Golderz in Gestein, Berggold sein.

2 Wörtl.: »das nicht dahingelangte«, also das unvollkommene. Gaṇ. zieht śreṣṭānām zum vorhergehenden Satz: »Von den besten Arten (Gold) ist das vorzüglichste staubfadenfarbig« usw. Dann hätten wir hier einfach: »Weißlichgelb oder weiß ist das unvollkommene.« Śreṣṭāṇām macht an beiden Orten Schwierigkeiten, bei Gaṇ.'s Auffassung aber mehr.

3 Paṭala »Haufen«, wie wir das Wort gebrauchen, nur eingeschränkt auf Kuhfladen und zwar nach dem Kom. sogar auf den trockenen vom Walde, wo ja das Vieh weidet.

4 Soll er damit infusieren, durchsetzen (niṣecayet).

5 Pākapattra »Durchhitzungsblatt« kehrt 88, 7 wieder, und pattra für ein Blatt, eine Platte, eine Schicht Metall haben wir öfters im Folgenden. Gaṇḍikā ist ein entästeter Baumstamm, ein Baumblock. So 206, 6; 363, 11. Dann überhaupt ein Holzblock wie im Pāli (Jāt. II, 124; III, 4; IV, 167, wohl auch Vin. II, 110; 136[?]; IV, 68[?]). Wahrscheinlich auch Balken, Stange oder Leiste (Vin. II, 172). Vgl. Pāli gaṇḍi Block, Richtblock (Jāt. III, 41, Z. 14; V, 303, Z. 24 und Str. 45).

6 Oder: »ist es frei von Wülstchen (Blasen)«? Es kommt wohl darauf an, ob an die noch heiße, flüssige Masse oder an das erkaltete Metall gedacht ist.

7 Bildet das Standard. Nur dies Wort entspricht wirklich. Varṇaka ist etwa = prativarṇaka 110, 13, also sample, Muster; dann Maßstab, Urbild, Ausgangspunkt und Sorte. Vgl. auch die im PW unter varṇaka aus dem Kathās. und der Rājat. angeführten Stellen.

8 Die Einheit eines survarṇa, d.h. eine Goldmenge im Gewicht von Goldmāṣa bildet also den Ausgangspunkt oder die Grundlage (s. Kap. 19, Text S. 103, 3 f.). Die wörtliche Übersetzung unserer Stelle, bei der man zunächst 88, 14 heranziehen muss, lautet: »Davon dann der von einer kākaṇī Kupfer anfangende und um je eine kākaṇī ansteigende Abzug bis zur Grenze« usw.; also apasārin + tā. Oder, und das ist das Wahrscheinlichere, man muss śulbena kākaṇy uttarāpasaritā lesen: »Davon wird im Austausch um Kupfer (immer) eine weitere (überzählige) kākaṇī (Gold) weggenommen«. Diese zweite Möglichkeit wird durch 91, 1 ff. nahegelegt. Uttarā »eine weitere« heißt dabei eine je um eins fortschreitende, anwachsende. Auch uttara weiter = überzählig wird mithereinspielen. Bhaṭṭ's Erklärung ist in der Sache ganz richtig, und über den Sinn kann kein Zweifel sein. Gold im Gewicht und Wert von einer kākaṇī, d.h. 1/64 des survarṇa, wird weggenommen und dafür ebensoviel Kupfer dazu getan. Das ergibt den ersten Mindergehalt, wo das Gold aus Teilen Gold und einem Teil Kupfer besteht. Beim zweiten wird für 2 kākaṇī Gold weggetan und 2 kākaṇī Kupfer hineingemischt. So hinauf bis zum 16. Mindergehalt, der sich aus 48 Teilen Gold und 16 Teilen Kupfer zusammensetzt. Dadurch erhalten wir zusammen mit dem Standard, dem Feingehalt oder Grundmuster, 17 Grade der Goldhaltigkeit.

9 Prativarṇikā 89, 3 bedeutet Probemuster, Versuchsmuster; prativarṇaka 62, 14; 110, 13 Muster. So wird wohl varṇikā etwa dasselbe heißen und Bhaṭṭ. recht haben, der freilich varṇaka liest. Sham., Sorabji und Jolly hätten die Geschichte nicht umdrehen sollen. In der Sache freilich kommt es schließlich auf das Gleiche hinaus. Aber auch die Inder werden doch nicht bloß das völlig reine Gold, den »Feingehalt«, als Prüfungsnorm von Legierungen verwendet haben, sondern, wie wir, eben auch Legierungen von bekanntem Gehalt.

10 Nikaṣita »geprüfsteint« oder »gegoldstricht«, d.h. auf dem Prüfstein oder durch den Strich auf dem Prüfstein als richtig befunden. Der vākyaśeṣa der indischen Erklärer ist also, soweit ich sehe, ganz unnötig. Die Bedeutungsentwicklung wäre vollkommen natürlich. – Statt animnonnate ist wahrscheinlich nimnonnate »an den vertieften und den erhöhten Stellen« einzusetzen.

11 Wörtlich: »daran geleckt« (parilīḍha).

12 Nicht nur das Neutr., sondern auch das Mask. nikaṣa hat neben der bekannten Bedeutung auch die des Striches auf dem Probierstein. Vgl. Kalāv. VIII, 4, wo mandaruciḥ gelesen werden muss. In unserem Text ist sakesaraḥ und nikaṣarāgaḥ richtig, wie schon Bhaṭṭ. hat.

13 Pratirāgin »der Abfärbung entsprechend, reagierend auf die Abfärbung«. Danach ist wohl samarāgin 86, 19 zu verstehen und folglich von Gaṇ. richtig erklärt. Mit ihm, muss im folgenden Satz chedaś statt śvetaś gelesen werden.

14 Kuraṇḍaka ist gelber Amaranth oder gelbe Barleria.

15 Wohl den Angaben jenes Kapitels. Aber auch die Lehren des vorliegenden Kapitels können gemeint sein.

16 Vgl. 26, 13–14. Da ist offenbar gemeint, der Betr. soll getötet werden. Also wird es hier nicht anders sein und wird Sham. recht haben, nicht aber Gaṇ., der da meint, es solle ihm all sein Gut genommen werden. Nichtangestellter (anāyukta) ist natürlich einer, der nicht in der Edelmetallschmiede beschäftigt ist. Von unredlichen Goldschmieden ist hier keine Rede.

17 Kāñcanapṛiṣata »Goldtropfen«. Die pṛiṣata werden wohl von Sham. richtig als durchlöcherte Kügelchen verstanden. Doch trennen er und Gaṇ., wohl nach Bhaṭṭ.'s Vorgang, kāñcana ab und sehen in den kāñcānakāru dann natürlich »Arbeiter in Gold«, was sich sonderbar ausnimmt. Gaṇ. meint, es seien die Leute, die geschickt seien, künstliches Gold zu machen. Ist kāñcanam allein in 87, 19 richtig und bezeichnet es also die Goldunterlage bei der Fassung von Edelsteinen, so möchte ich lieber die kāñcanakāru für die Künstler halten, die Edelsteine fassen. Bei denen schiene solch eine genaue Untersuchung auch nötiger zu sein als bei den Goldmachern. Tvaṣtṛikarman »Baumeisterarbeit«, vielleicht mit Hinblick auf Tvaṣṭar, den Verfertiger der Werkzeuge der Götter, ist nach Ausweis von 88, 4 ff. die Herstellung von Geräten (Gefäßen usw.). Tapanīya bezeichnet hier Goldschmuck, Goldsachen, die man trägt, wie die Schlußverse des Kapitels dartun.

18 Caraka wird hier von Sorabji und Gaṇ. wohl richtig paricāraka gleichgesetzt. Spion kann es hier kaum bedeuten.

19 Die Frauen können sich mit Hilfe der ihrigen ja die Schätze Golkondas aneignen. Für solch bequeme Schmuggelgelegenheit hatten die altindischen Schmuggelschnüffler jedenfalls eine bessere Nase als die unsrigen. Beim männlichen Gliede nun geht die Sache unendlich viel schlechter. Trotzdem wird guhya hier auch seine gewöhnliche Bedeutung haben, nicht nur die seltene, nach dem PW nur einmal, und da nicht völlig sicher belegte »After«, die hier allein statthaft scheinen möchte. Die altindischen Langfinger waren gewiss auch in diesem Stück fähig, sich zu großer Virtuosität zu trainieren. Überhaupt: Man hat viel vom Heroismus der Tugend geredet. Doch lassen wir die Tugend; sie ist nicht mehr salonfähig. Käme der homo sapiens einmal dahin, dass er ein Hundertstel des Heroismus, den er nicht nur für den Krieg, sondern auch für all seine anderen Verbrechen und Laster aufbringt, dem Dienste edler, wahrhaft freier Menschlichkeit widmete, welch ein Wunderort könnte noch diese klägliche Erde werden! Doch Träume sind Schäume. Wir haben's mit dir zu tun, o Kauṭilya. Warum wird denn der Mund nicht untersucht? Sogar mehr Gold kann jemand in diesem tragen, als ein Johannes Chrysostomos und die Morgenstunde zusammen.

20 Kārayitar wäre am ehesten der Besteller. Aber wie könnte der jeden Abend in die Goldschmiede kommen? Also am Ende doch der Anordner, der Vormann? Im Bureau wird genaue Kontrolle geführt. Das Gold, das der Goldschmied zur Verarbeitung erhält, und die fertigen Arbeiten (man muss wohl kṛitaṃ statt dhṛitaṃ lesen) hat er vorzulegen, ebenso jeden Morgen und Abend alles Wertvolle mit den genannten Siegeln dran, damit man im Bureau zu sehen vermag, dass in der Nacht nichts angetastet worden ist. Dem Goldschmied selber wäre natürlich nicht zu trauen, obgleich er »von guter Geburt und vertrauenswürdig« ist (85, 12 f.).

21 Also aufgereihte Gehänge wie Halsschnüre, Gürtel usw. Wörtlich: »das Weben von Schnüren usw.«.

22 Vgl. 88, 2–3 und 16 und verliere dein letztes bisschen Sicherheit! Im Text fasse ich es also so auf, dass zwei Zehntel des ganzen Schmuckes oder Zierstückes aus goldener Unterlage, ein Zehntel aus der Seiteneinfassung der Steine usw. bestehe. Möglich wäre auch: »ein Fünftel soviel Gold, wie die Edelsteine oder der Edelstein ausmachen« und »ein Zehntel soviel«. So hat es offenbar Bhaṭṭ. verstanden; denn er sagt: maṇeḥ (so lese ich statt des maṇau bei Sorabji und finde meine Mutmaßung durch Gaṇ. bestätigt) pañcamaṃ bhāgaṃ talabhāgakāñcanam ity ādhārasuvarṇaṃ praveśayet. Das setzt freilich große Edelsteine voraus. Vergleicht man nun aber 88, 2–3, so schiene trotz der schweren sachlichen Bedenken: »fünf Teile Gold als Unterlage und zehn Teile als Befestigung« nötig zu sein. D.h. ein Drittel der ganzen verwendeten Goldmasse käme auf die Unterlage und zwei Drittel auf die Einfassung. Das klingt aber höchst sonderbar. Dass kāñcana = GoldunterlageA2 sei, ist ebenfalls recht unsicher. Man wird am Ende doch kāñcanavāstukaṃ oder kāñcanaṃ vāstukam lesen müssen unter Vergleichung mit 88, 2 ff. – Gaṇ. liest kaṭumānam, Bhaṭṭ. haṭamānam. Kaṭamāna (vielleicht besser kaṭimāna) »Hüftenmaß« oder »Hüftenbau« sieht sehr vernünftig aus. Mit kaṭumāna aber sitzt man ganz auf dem Trockenen.

23 So nach Gaṇ.'s Text. Von der Schwierigkeit, die sich aus der Vergleichung mit 87, 19 ergibt, ganz zu schweigen, so ist schon das hi höchst sonderbar. Auch Gaṇ. hat es. Soll man dvibhāgāḥ, lesen: »drei zwiefache Teile« usw., d.h. zwiefach im Verhältnis zu dem Gefassten, sodass also hier Untergrund und Einfassung doppelt so viel ausmachen als das Gefasste oder gar 10, bzw. 14 mal so viel? Das klänge recht toll. So ist auch diese auf den ersten Blick ganz klare Stelle sehr dunkel.

24 Doch wohl weniger wahrscheinlich: »Oder eins, das aus einem Viertel Gold (und drei Vierteln Silber) besteht, möge er mit einer flüssigen oder einer pulverisierten Mischung aus Sand und Zinnober bekleiden« (vāsayet von vas, vaste). Vā, das freilich bei Gaṇ. fehlt, deutet aber am natürlichsten auf diese Auslegung. Sprachlich unmöglich ist die von Gaṇ.

25 Verwunderlich ist bei der bisherigen Auffassung, auf die ich zuerst verfiel, 1. dass da der doch so wichtige Goldschmuck keine Berücksichtigung fände, 2. dass die Beschreibung des Goldes für die Farbtinktur doch allzu überlastet wäre. Wörtlich also wohl doch lieber: »Goldschmuck ist das beste« (Gold).

26 Und auch auf dem Holzblock gehämmert (wie 86, 3)? Nach Bhaṭṭ. dem alle anderen folgen: »mit trockenem Kuhmist zum Schmelzen gebracht«. Aber 86, 3 kommt man mit dieser Bedeutung kaum zurecht, obgleich pākapattra »Backblätter« ganz gut trockenen Kuhfladen bezeichnen könnte. Statt »geläutert« hieße es wörtlich: »durchpassiert« (durch den Läuterungsprozess?). Bhaṭṭ. umschreibt atikrānta aber allem Anschein nach richtig mit śodhita. Vgl. Zeile 13.

27 Cimicimāyate, das wir sonst nur in der Bedeutung stechen, prickeln keimen, hat jedenfalls die von Bhaṭṭ. angegebene Bedeutung, und zwar wird kaum die Vorstellung zugrunde liegen, dass der Farbenglast geradezu stechend oder prickelnd für die Augen sei. Vgl. das gleicherweise lautmalende simisimāyate »simmern« mit diesem cimicimāyate »schimmern«.

28 Von diesem Färbezusatz braucht es also nur 1/61, soviel wie von dem zu färbenden Gold; denn der suvarṇa ist ja = 64 kākaṇī.

29 Die Farbebeigabe müsste hier doch wohl eine Silberfarbtinktur sein. Nach Bhaṭṭ. aber bezeichnet rāga in Zeile 18 das tīkṣṇa von Zeile 10. Dann muss er wohl an unserer Stelle dasselbe annehmen. Auf jeden Fall ergeben sich so acht Silberlegierungen, von denen die erste nur 1/64 Gold, die letzte 8/64 enthält. Wir haben suvarṇe viṣaye in Gold (in Form von Gold) soll immer soviel hinzugegeben werden, wie man Silber weggenommen hat. Nicht aber kann es, wie man bisher geglaubt hat, heißen: »Zu einem suvarṇa Gold wird immer die betr. Menge Silber hinzugetan«. Denn dass eine Mischung von 1/64 Silber und 63/64 Gold Weißsilber ergeben sollte, ist ja heller Unsinn. Was die Läuterung mit Kupfervitriol betrifft, so muss man wohl annehmen, dass in den Fällen, wo Kupfervitriol (tuttha) nicht ausdrücklich genannt wird, es hinzugedacht werden muss. Doch bin ich der Übersetzung keineswegs sicher, weiß auch nicht, was kapāla hier bedeutet, weiß nur dies, dass die völlig verschiedene Auslegung der Stelle, die Bhaṭṭ. gibt, ganz töricht aussieht.

30 Oder: »drei Teile«. Aber wovon? Ist wirklich die Farbessenz (tīkṣṇa) von Zeile 10 bis 11 gemeint, dann wäre es wohl ein Drittel von jener Dosis, also 1/192 der zu färbenden Masse. Was hat aber hier, wo doch von den Legierungen des Weißsilbers geredet wird, auf einmal diese Goldmischung verloren? Man muss also vielleicht übersetzen: »Nachdem man geläutertes Gold aufgekocht hat, füge man (davon) ein Farbdrittel hinzu«, d.h. füge man zu Weißsilber, um ihm Farbenwärme zu geben, ein Drittel soviel von diesem Gold als man sonst Silberfarbstoff beifügte, hinzu. »Dann wird es gelbfarbig.«

31 Mit halb so viel Prozent Eisen, wie beim vorigen Rezept Gold beigegeben worden ist, also einem Sechstel, wie Bhaṭṭ. gewiss richtig sagt. Dann kann aber nicht Gold die schwarz zu färbende Masse sein, wie Sham., Jolly und Gaṇ. annehmen. Auch hätte es wenig Sinn, dass Kauṭ. in Zeile 2 ausdrücklich tapanīyam hinsetzte, wenn bereits im Vorhergehenden dies das Subjekt wäre. Endlich ist allem Anschein nach durchweg von 88, 12 an bis 89, 2 Weißsilber der einzige Gegenstand der Besprechung.

32 Drei verschiedene Auslegungen dieser Stelle gibt Bhaṭṭ. Von ihm geleitet, nehmen Sham., Jolly und Gaṇ. an, es handle sich hier um einen Anstrich aus Eisen und Quecksilber. Aber weder diese Auffassung noch die von Bhaṭṭ. aufgeführten scheinen dem Wortlaut und der Vernunft gerecht zu werden. Pratilepin kann nur etwa »anklebend« heißen, es sei denn, es bezeichne eine besondere Substanz, was kaum wahrscheinlich sein dürfte. Rasa nun bedeutet, soviel ich sehe, nirgends bei Kauṭ. klar und deutlich Quecksilber. Im Lichte der vorliegenden Kapitel betrachtet, kann es wohl nur als Saft, Flüssigkeit, namentlich Goldflüssigkeit verstanden werden. Sodann lässt es sich nicht denken, dass Gold durch doppelten Anstrich von Eisen, selbst wenn Quecksilber beigemischt ist, papageienfarbig würde, wenn schon durch den einfachen Anstrich Weißsilber (ja nach der bisherigen Auffassung Gold selber) schwarz wird. »Papageienfedernfarbig« bezeichnet nun an anderen Stellen, wo es vorkommt, allem Anschein nach ein Gelb. Da stünde also die Farbe im besten Einklang. Gewiss ist mir jedoch nur dies, dass alle anderen Erklärungen falsch, nicht aber, dass meine richtig ist.

33 Wörtlich: »er nehme ein Muster«, also: mache einen Versuch im Kleinen. Mit prativarṇikā vgl. varṇikā 86, 11 und prativarṇaka 62, 14; 110, 13, sowie varṇaka 86, 9–10.

34 Wörtlich wohl: »auf die Herrichtung« (saṃskāra). Das schlösse jedenfalls auch die Prüfung ein. Nur diese scheint Bhaṭṭ. hier zu sehen, wenn anders sein śodhana, »Reinigung«, aber auch »auf die Probe Stellen«, von Sham. richtig verstanden wird. Nun bedeutet tīkṣṇa, das wohl 83, 9 und 84, 3, kaum aber hier Eisen bezeichnen wird, auch Salpeter. Könnte also tīkṣṇatāmrasaṃskāra, dessen tāmra vielleicht eine falsche Lesart darstellt, eine Goldprüfungsart sein, ähnlich der unserigen mit Salpetersäure, d.h. mit dem Königswasser? Dass der Goldaufseher sich auch auf die ganze Behandlung von Kupfer und Eisen verstehen müsste, scheint eine unnötige Forderung zu sein. Denn soweit in der Goldschmiedekunst Kupfer zur Verwendung kommt, ginge es wohl ganz gut ohne solche eingehende Fachkenntnis von Kupfer, und Eisen spielt da gar keine weitere Rolle. Sodann sind Kupfer und Eisen und alles, was mit denen zusammenhängt, doch Sache des Anfsehers über die unedeln Metalle (lohādhyakṣa 84, 3 f.).

35 Oder: »danach.« Bhaṭṭ. sagt wohl richtig: »nach dem Beispiel des Goldes«; d.h. was Kauṭ. vom Gold gesagt hat, ist Anleitung auch für die Edelsteine usw.

36 Ein Blick schon auf apaneyiman lehrt, dass es von apanayati »wegnehmen« kommt. So sagt denn auch Bhaṭṭ., es sei = apanītatva, womit uns freilich nichts geholfen ist. Der erste Bestandteil apaneya gibt die zwei Möglichkeiten an die Hand: 1. Wegnehmbarkeit, Abziehbarkeit, 2. Notwendigkeit des Wegnehmens oder Abziehens. Im Text habe ich es im zweiten Sinn gefasst, weil es sich so am besten in den Zusammenhang fügt und auch sonst am ehesten zu passen scheint. Hat es die erste Bedeutung, dann muss es wohl heißen: er soll wissen, was, wieviel usw. die Betrüger bei Edelsteinen und den ihnen verwandten Dingen wegnehmen, fälschen, vertauschen, unterschieben können. So versteht es offenbar Gaṇ. Auch rūpyasuvarṇabandha hat seine Tücken. Man könnte auch übersetzen: »wieviel Bindung (Festigungszusatz) es braucht bei Waren aus Silber und Gold«. So erklärt es Gaṇ. Aber eine solche verengende Einzelheit scheint hier nicht am Platze zu sein. Das auch von Jolly gebrauchte »Herstellung« schließt jenes mit ein.

37 Wörtl.: »gleiche Paare oder Gegenstücke habend«.

38 Asaṃpīta, wörtl. etwa: »unverwässert, undurchtränkt.« Vgl. pāyita durchtränkt 415, 4.

39 Abhinīta. Nach den indisch. Lex. sollte das wohl etwa mit »vorzüglich hergerichtet« übersetzt werden. Vgl. aber das PW unter abhinī, ferner nīta, nīti und vinaya. Dem entsprechend also: feine Bildung des Geistes und sittliche Selbstkultur verratend, also auch frei von Aufdringlichkeit, keusch, nicht nur geistvoll.

A1 Mit saṃyūhayati vgl. nijjūhiūṇa zurückweisend (Uttarajjh. XXXV, 20). Dies könnte man von einem Denom. niryūthayati »aus des Herde hinaustun« ableiten. Aber zu XXXVI, 256 sagt der Kommentar, nijjūhaṇa (= tyāga) komme von niryūhana. Unsere Kauṭilyastelle gibt ihm Recht. Freilich ließe sich auch annehmen, die Wurzel yūh beruhe auf falscher Sanskritisierung.

A2 In Raghuv. VI, 79 lesen wir: Ratnaṃ samāgacchatu kāñcanena. Das könnte nun bedeuten: »Die Perle geselle sich einer Goldunterlage.« Aber es wird wohl einfach heißen: »dem Golde«, wie es die ind. Komm, verstehen."

[Quelle: Kauṭilya: Das altindische Buch vom Welt- und Staatsleben : das Arthaśāstra des Kauṭilya / [aus dem Sanskrit übersetzt und mit Einleitung und Anmerkungen versehen von] Johann Jakob Meyer [1870-1939]. -- Leipzig, 1926. -- Digitale Ausgabe in: Asiatische Philosophie. -- 1 CD-ROM. -- Berlin: Directmedia, 2003. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 94). -- S. 122 - 129.]

|

92a./b. tābhyāṃ yad anyat tat kupyaṃ rūpyaṃ tad dvayam āhatam ताभ्यां यद् अन्यत् तत् कुप्यं रूप्यं तद् द्वयम् आहतम् ।९२ क। Von diesen beiden (Gold und Silber) verschiedenes Metall heißt कुप्य - kupya n.: Nicht-Edelmetall, Metall (außer Gold uns Silber) |

Colebrooke (1807): "Base metals."

"The metals [dhātu] used in Sanskrit medicine are

- gold,

- silver,

- copper,

- tin,

- zinc,

- lead,

- iron,

- bell-metal, and

- brass."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 23.]

"Metals and metallic compounds [for medical use] are subjected to a so-called process of purification in order to get rid of their impurities or deleterious qualities. If used in an unpurified state, they are supposed to induce certain diseases or morbid symptoms. The metals, for the most part, are purified by repeatedly heating their plates and plunging them in the following fluids, namely, oil, whey, sour conjee, cow's urine and the decoction of a pulse called kulattha (Dolichos uniflorus). Another method of purification consists in soaking the plates of heated metals in the juice of the plantain-tree.

Metals and metallic compounds are reduced to powder by various processes. The operation is called māraṇa, which literally means killing or destruction of metallic character but practically a reduction to powder, either in the metallic state, or after conversion into an oxide or a sulphide.

Various processes for the calcination of different metals are described in Sanskrit works on the subject. I will not burden these pages with a detailed account of these but shall only describe modes of preparation followed at the present day.

Although the Hindus had made some successful efforts in preparing a certain number of chemical compounds such us perchloride of mercury, sulphides of copper and silver, oxide of tin, some acids, alkalies, etc., yet their chemical operations were of a very rude and primitive character. The apparatus employed by them consisted of crucibles of different sorts, glass bottles and earthen pots arranged for sublimation of volatile compounds, retorts for distillation, sand and vapour baths, etc. The furnace for heating metals is usually a pit in the ground called गजपुट Gajapuṭa. It is made one and a quarter cubits in depth, length and breadth. This is filled with dried balls of cowdung. The metals or metallic compounds to be roasted are enclosed in a covered crucible and placed in the centre of the pit within the balls of cowdung, which are then set fire to and allowed to burn till consumed to ashes.

मुषायन्त्र Muṣāyantra or crucibles, are recommended to be made of husks of rice two parts, earth from ant-hills, iron rust, chalk and human hair cut into small bits, one part each. These are rubbed together into a paste with goat-milk, and made into crucibles which are dried in the sun. Practically, however, goldsmith's crucibles or common earthen cups are used. The compounds to be roasted are placed in one crucible, this is covered with a second, and the two are luted together with clay.

वालुकायन्त्र. The sand-bath called Vālukā yantra is made by filling an earthen pot with sand and heating it over the fire. Metalic preparations sublimed within glass bottles are heated in sand-baths.

दोलायन्त्र. When medicines, tied in a piece of cloth or other material, are suspended and boiled in a pot of water, the apparatus is called Dolā yantra. The steam-bath called Śvedana yantra is got up by covering the mouth of a pot of boiling water with a piece of cloth, placing the medicines to be heated by steam on this cloth, and then covering them with another pot.

For the sublimation of metals and metalic preparations, two sorts of apparatus are used. The first, called उर्द्धपातनयन्त्र Urddhapātana yantra, consists of two earthen pots placed one above the other with their rims luted together with clay. The lower pot containing the medicine is put on fire while the upper one is kept cool with wet rags. The sublimate is deposited in the interior of the upper pot. Sometimes the lower pot is covered with a concave dish and water poured into its hollow to keep it cool and changed as often as it gets hot. The second plan consists in placing the medicines to be sublimed in the bottom of a glass bottle which has been strengthened with layers of clay and cloth wrapped round it, and then exposing it to heat in a sand-bath. The sublimate is deposited in the neck of the bottle, whence it is extracted by breaking the latter.

तिर्यक्पातनयन्त्र Tiryakpātana yantra. This apparatus means the adjustment of retorts and receivers for sublimation and distillation. At the present day glass retorts of European manufacture are used. Country-made glass retorts are also available."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 24f.]

"ZINC. Sans. यशद, Yaśada. Vern. Dastā.

Zinc is not mentioned by the older writers, such as Susruta, nor does it enter into the composition of many prescriptions. The Bhāvaprakāśa mentions it in the chapter on metallic preparations, and directs it to be purified and reduced to powder in the same way as tin. It is said to be useful iu eye diseases, urinary disorders, anaemia and asthma.

Kharpara. This mineral is mentioned in most works. It enters into the composition of a number of prescriptions both for internal and external use. The article used under this name by the physicians of Upper India is a sort of calamine or zinc ore. Most of the physicians in Bengal are not acquainted with this ore, and substitute zinc for kharpara, that is, they consider kharpara as a mere synonym of zinc or yaśada. They accordingly direct that kharpara should be reduced to powder by being melted over a fire and rubbed with rock salt. Zinc thus prepared is a fine yellowish grey powder consisting of carbonate of zinc mixed with chloride of sodium. In the works of the physicians of Upper India, this preparation is not described. There they use the zinc ore, which does not dissolve on the application of heat. It is simply purified by being boiled in cow's urine or soaked in lemon juice and then powdered. The Bengali physicians who substitute zinc for kharpara are evidently wrong, for the description of some of the preparations of this drug, as for example of the collyrium mentioned below, can not apply to metallic zinc.

Kharpara, as sold by Hindustani medicine vendors, occurs in greyish or greyish black porous earthy masses composed of agglutinated granules. On chemical analysis it was found to consist of carbonate and silicate of zinc with traces of other metals as iron baryta, etc. Kharpara is described as tonic and alterative and useful in skin diseases, fevers etc. It is also much used as a collyrium in eye diseases. Dose, grains six to twelve.

[...]

A collyrium is prepared as follows. Rub some kharpara in a stone mortar with water, take the dissolved watery portion, rejecting any solid particles that may have subsided to the bottom. Evaporate this solution, powder the residue and soak it three times in a decoction of the three myrobalans. When dry add one tenth part of powdered camphor and mix intimately. This collyrium is said to be useful in various sorts of eye diseases."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 71f.]

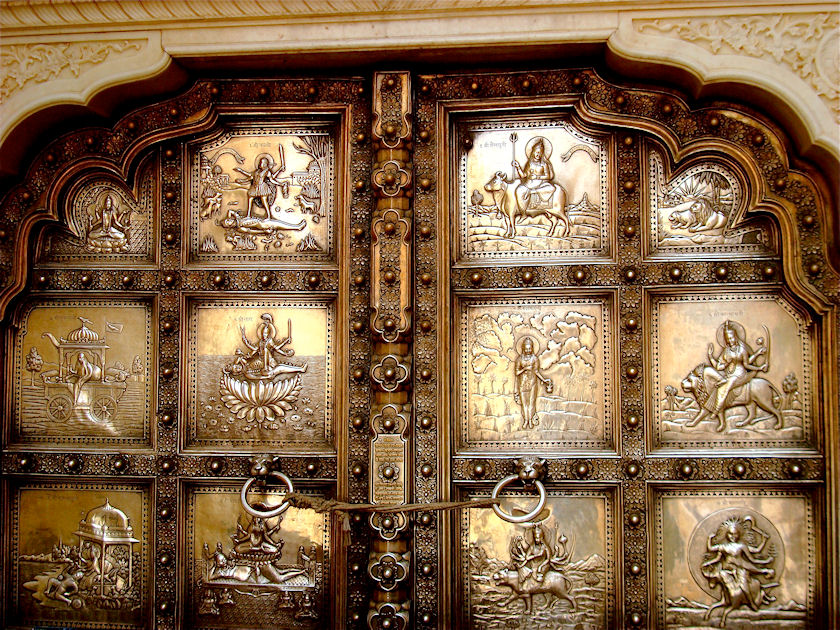

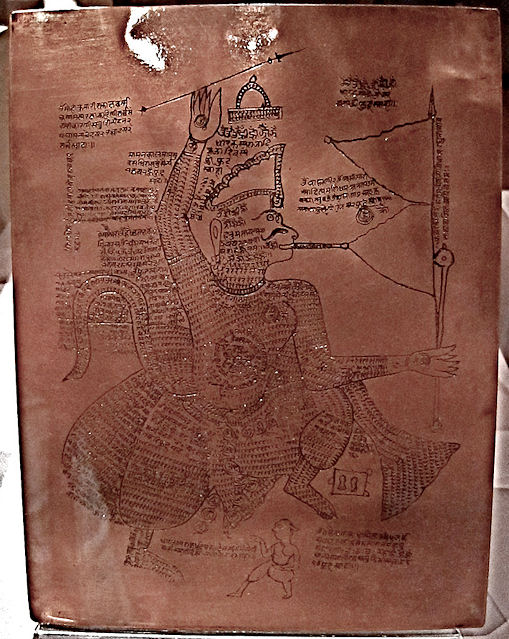

कुप्य - kupya n.: Nicht-Edelmetall, Metall (außer Gold uns Silber)

Abb.: कुप्यम् । Kupferplatte, Vijayaraṃga Cokka Nātha Nāyaka - విజయరంగ చోక్క

నాథ నాయక, Telugu, 1717

[Bildquelle: Daderot / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: कुप्यम् । Bleimünze von Vasisthiputra Sri Pulamavi (Sātavāhana), 1./2.

Jhdt n. Chr.

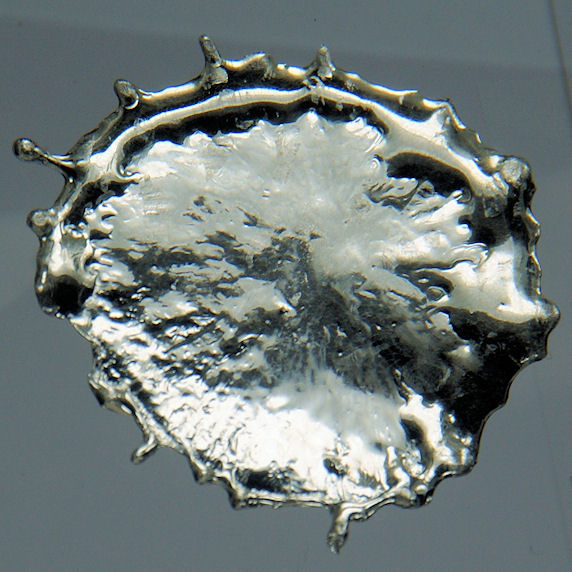

Abb.: कुप्यम् । Zink (Zn)

[Bildquelle: Alchemist-hp / Wikipedia. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung,

keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: कुप्यम् । Zinn (Sn)

[Bildquelle: Jurii / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

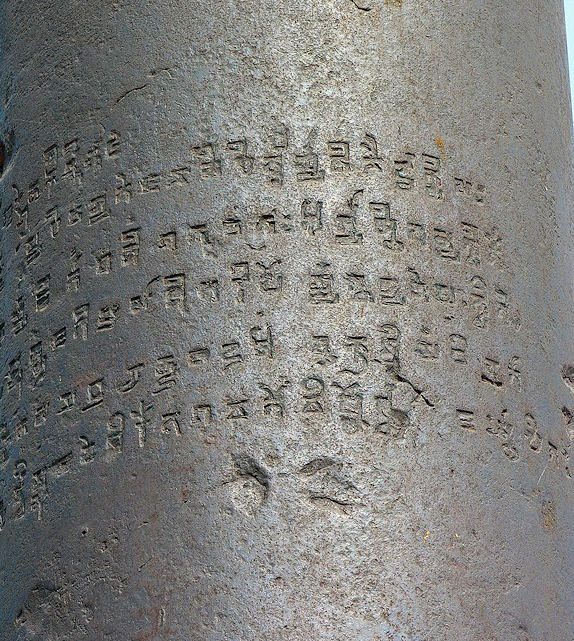

Abb.: कुप्यम् Inschrift auf 7 m hoher, nichtrostender Eisensäule, Delhi, 4. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Mark A. Wilson / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

"METALS.

[...]

The metallic products of the East Indies comprise

- antimony,

- arsenic,

- chromium,

- cobalt,

- copper,

- gold,

- iron,

- lead,

- manganese,

- mercury,

- nickel,

- platinum,

- silver,

- tin,

- titanium, and

- zinc.

Metal casting in India is very largely practised, and the processes are of great simplicity. The natives generally prepare a model in wax, and imbed it in moist clays, which, after being dried in the sun, is heated in the fire, the wax run out, and the metal run in. A better plan, where accuracy is required, is to cut the model in lead, and, having bedded it in clay, it may, when the mould is dry, be melted and run out, and the metal run in. In Manbhum, a core is made of plastic clay, all carefully shaped to the internal form of the fish or other object to be imitated. This core is then baked and indurated. On this, the pattern designed to be represented is formed with clean beeswax. This done, and the wax having cooled, it becomes tolerably hard. Soft clay is moulded over all. The whole is then baked, the heat indurating the outer coating of clay, but softening the wax, which all runs out of the mould, leaving empty the space occupied by it. The mould being sufficiently dried, the molten brass is poured into the empty space, and, when cool, the clay is broken away, when the figured casting is seen. These are untouched after the casting, excepting on the smooth and flat surfaces, which are roughly filed. The Chinese excel in all working in metals, in ordinary blacksmith work, metal smelting, alloys, particularly their white metal of copper, zinc, iron, silver, and nickel, their sonorous gongs and bells, one at Pekin being 14½ feet by 13 feet, and their ingenious metallic mirrors, some with engravings. The Burmese, also, are skilled.

Indian metal ware is of several descriptions, some of it being much admired by Europeans. The black engraved work of Moradabad, N.W. Provinces, is well known, and so is the Tanjore brass ware. Madura men also manufacture brass vessels, to sell to the pilgrims. Messrs. Morrison, Rohde, Cal. Cat. Ex. 1862."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 2. -- 1885. -- S. 933f.]

|

92a./b.

tābhyāṃ yad anyat tat kupyaṃ

rūpyaṃ tad dvayam āhatam ताभ्यां यद् अन्यत् तत् कुप्यं रूप्यं तद् द्वयम् आहतम् ।९२ क। Geschlagene (geprägte) Edelmetalle heißen रूप्य - rūpya n.: "eine schöne Gestalt habend", Silber, gestempeltes oder geprägtes Gold und Silber |

Colebrooke (1807): "Bullion."

रूप्य - rūpya n.: "eine schöne Gestalt habend", Silber, gestempeltes oder geprägtes Gold und Silber

Abb.: रूप्यम् । Münze von Samudragupta zur Erinnerung an sein Aśvamedha, 4.

Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: रूप्यम् । Gestempelte Larin-Münze, 12./13. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. / Wikimedia. -- GNU

FDLicense]

Abb.: रूप्यम् । "Punch marked coin", Maurya, 3./2. Jhdt. v. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Per honor et gloria / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: रूप्यम् । Münze von Rudrasimha I, 2. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Per honor et gloria / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

| 92c./d. gārutmataṃ marakatam aśmagarbhaṃ harinmaṇiḥ गारुत्मतं मरकतम् अश्मगर्भं हरिन्मणिः ।९२ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Smaragd:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "An emerald."

"Smaragd ist eine im hexagonalen Kristallsystem kristallisierende Varietät des Silikat-Minerals Beryll und hat eine Härte von 7,5 bis 8. Seine chemische Zusammensetzung ist durch Be3Al2Si6O18 beschrieben. Die Farbe ist durch Beimengung von Chrom- und Vanadium-Ionen grün, die Strichfarbe ist weiß." [Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smaragd. -- Zugriff am 2011-09-21]

गारुत्मत - gārutmata n.: die Gestalt des Garuḍa habend, die Farbe des Garuḍa habend, Smaragd

Abb.: गारुत्मतम् । गरुडः - Garuḍa, Kullu - कुल्लू, Himachal Pradesh, 1750

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of

Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4838471614/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-12. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: गारुत्मतम् । Smaragd, Panjshir Valley ( درهٔ پنجشير

), Afghanistan

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

मरकत - marakata n.: Smaragd

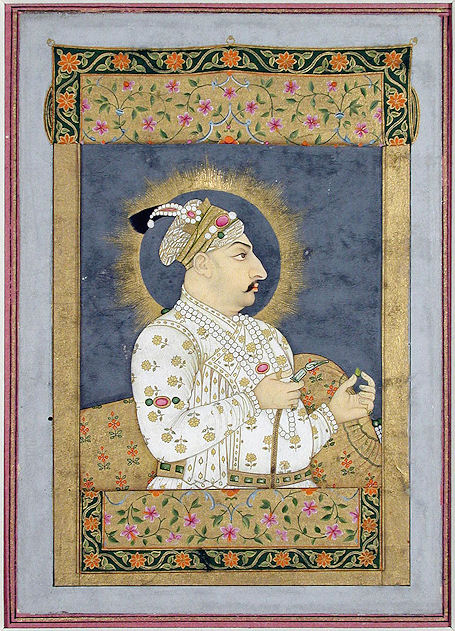

Abb.: मरकतम् । Emperor Muhammad Shah (محمد شاه) mit Smaragd in Hand / von Nidha Mal, ca. 1730

[Bildquelle: The San Diego Museum of

Art Collection. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/thesandiegomuseumofartcollection/6125078792/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-21. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

अश्मगर्भ - aśmagarbha n.: Stein als Ursprung habend, auf Stein wachsen, Smaragd

Abb.: अश्मगर्भम् । Smaragd, Badakhshan (بدخشان), Afghanistan

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

हरिन्मणि - harimaṇi m.: grüner Edelstein

Abb.: हरिमणिः । Smaragd, Panjshir Valley ( درهٔ پنجشير

), Afghanistan

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"EMERALD.

[...]

It is the rarest of all gems, of a beautiful green colour, unsurpassed by any gem. When of a deep rich grass-green colour, clear and free from flaws, it sells at from £20 to £40 the carat, those of lighter shade from 5s. to £15 the carat. The finest occur in a limestone rook at Muzo, in New Granada, near Santa Fé de Bogota 6° 28', at Odontchclong in Siberia, and near Ava.

From ancient times many stones hare been famed as emeralds, which can only bare been jasper or other green mineral. [...]

Aquamarine

includes clear beryls of a sea-green, or palebluish, or bluish-green tint. Hindus and Mahomedans use them pierced as pendants and in amulets. Many of the stones used as emeralds in India consist of beryl. Prismatic corundum or chrysoberyl, says Dr. Irvine, is found among the Tora hills near Rajmahal on the Bunas, in irregular rolled pieces, small, and generally of a light green colour. These stones are considered by the natives as emeralds, and are called in Panjabi Panna. The most esteemed colours are the Zababi, next the Saidi, said to come from the city Saidi in Egypt ; Raihani, new emeralds ; Fastiki, old emeralds, that is, such as have completed their 20 years ; Salki, Zangari, colour of verdigris ; Kirasi and Sabuni.

Most of the emeralds commonly in use in India are smooth, cut and bored like beads ; they are always full of flaws."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 1047f.]

| 93a./b. śoṇaratnaṃ lohitakaḥ padmarāgo 'tha mauktikam शोणरत्नं लोहितकः पम्द्मरागो ऽथ मौक्तिकम् ।९३ क। [Bezeichnungen für Rubin:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A ruby."

"Als Rubin [Al2O3, sowie Beimengungen von Cr] bezeichnet man die rote Varietät des Minerals Korund. Die rote Verfärbung ist auf geringe Beimengungen von Chrom zurückzuführen. Nur die roten Korunde heißen Rubine, wobei der Rotton zwischen Blassrot und Dunkelrot variieren kann. Rosafarbene werden allerdings ebenso wie blaue und alle anderen Farbvarietäten unter der Bezeichnung Saphir zusammengefasst." [Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubin. -- Zugriff am 2011-09-21]

शोणरत्न - śoṇaratna n.: roter Juwel

Abb.: शोणरत्नानि । Ring mit Rubinen und Smaragden, Moghulzeit, Indien

[Bildquelle: Val_McG. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/33676549@N04/3312614172. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-21. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

लोहितक - lohitaka m.: Roter, Rubin

Abb.: लोहितकः । Rubin, Mysore District - ಮೈಸೂರು ಜಿಲ್ಲೆ,

Karnataka

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

पम्द्मराग - padmarāga m.: Lotusfarbiger, Lotusroter, Rubin

Abb.: पद्मरागः । पद्मौ । Lotusse - Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. 1788,

Hyderabad - హైదరాబాదు,

Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: पद्मरागाः । Gold-Gürtel (

"RUBY.

[...]

The true oriental ruby, the sapphire, the topaz, and the emerald, though differing greatly in appearance, arc chemically the same substance, pure alumina ; but jewellers give this name to several other minerals possessing brilliant red colour. The oriental ruby is the most valuable of all gems when of large size, good colour, and free from flaws. The ruby in colour varies from the highest rose tint to the deepest carmine, but the most valuable tint is that of pigeon's blood, a pure, deep, rich red, and generally occurs in 6-sided prisms.

The hest come from India, Burma, and Ceylon; Bohemia furnishes an inferior article. They are found in Ava, Siam, the Cupelam mountains, ten days' journey from Syrian a city in Pegu, Ceylon, India, Borneo, Sumatra, on the Elbe, on the Espailly in Auvergne, and Iser in Bohemia. The ruby and sapphire mines of Burma are 25 miles south of Moongmeet. Many of the rubies and other precious stones that the Shans bring with them in their annual caravan from the north of Burma, are made of rock-crystal, coloured artificially. These are heated and plunged into coloured solutions. Fine rubies have from time to time been discovered in many of the corundum localities of Southern India, associated with this gem, particularly in the gneiss at Viralimodos and Sholasigamany. It occurs also in the Trichingode taluk and at Mallapollaye, but it is, comparatively speaking, rare.

In Ceylon, at Badulla and Saffragam, and also, it is said, at Matura, rubies, sapphires, and topaz are found. Badakhshan has been famed since the time of Marco Polo as the country producing the true balas ruby. Its ruby mines are in the Gharan district, 20 miles from the small Tajak state of Ishkashm, on the right bank of the Oxus. They have not been worked since the Kimduz chief took Badakhshan. Irritated by their small yield, he marched the inhabitants of the district, 500 families, to Kunduz, where he sold them as slaves.

Of the accounts of the ruby mines of Burma, one was written by Père Giuseppe D'Amato, an Italian Jesuit missionary to Burma, a translation of which appeared in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1833 ; and another account by Mr. Bredmeyer, who about 1870 was in charge of some minor ruby mines within 16 miles of Mandalay. The mines visited by Père D'Amato are said to be 60 or 70 miles distant from Ava in a north-east direction, and separated from the Irawadi valley by the Shoay-aoung or Golden Mountain range, which are only occasionally visible from the town of Male, owing to the constant fogs and mists that hang around, and snow lies on them for four months of the year, beginning with the middle or end of November. They are situated north-east from Mandalay, and distant about 60 or 70 miles. The principal road to them leaves the Irawadi at Tsiuguh-Myo, and passes through Shuemale. There are other roads, from Tsarapaynago and other villages to the north. The mines lie nearly due east from the village. The villages in the immediate neighbourhood of the mines are Kyatpen, Mogouk, and Katheyuwa. The gems are procurecl over an area of probably 100 square miles. The mode of seeking for them is simply sinking pits until the gem-bed or ruby earth is met with ; this is then raised to the surface and washed. The gem-bed is met with at various depths, sometimes not more than two or three feet from the surface, and occasionally not at all. When the layer of earthy sand containing the rubies is met, lateral shafts are driven in on it, and the bed followed up, until it either becomes necessary to sink another pit in it, or it becomes exhausted. It varies in thickness from a few inches to two or three feet. The rubies are, for the most part, small, not averaging more than a quarter of a rati, and when large are generally full of flaws. Well-marked crystals occasionally occur, but the vast majority of stones are well rounded and ground down. It is very rare to find a large ruby without flaws ; and Mr. Spears states that he had never seen a perfect ruby weighing more than half a rupee. The same authority mentions that sapphires are also found in the same earth with the rubies, but are much more rare, and are generally found of a larger size. Stones of ten or fifteen rati without a flaw are common, whereas a perfect ruby of that size is hardly ever seen. The largest perfect sapphire he ever saw weighed one tikal. It was polished, but he has seen a rough one weighing 26 tikal. For every 500 rubies, he does not think they get one sapphire. You see very small sapphires in the market, while small rubies are abundant and cheap. The value of the gems, rubies, and sapphires obtained in a year maybe from £12,500 to £15,000. They are considered the sole property of the king, and strictly monopolized, but, notwithstanding the care that is taken, considerable quantities are smuggled. There are about 20 lapidaries or polishers of these stones at Amarapura ; they are not allowed to carry on their trade at the mines. For polishing, small rubies and worthless pebbles brought from the mines, being pounded fine and mixed up with an adhesive substance, and then made into cakes some ten inches long by four broad, are employed to rub down the gem. After it has been brought to the form and size required, another stone of finer grain is employed. The final process is performed by rubbing the ruby on a plate of copper or brass until it is thoroughly polished, when the gem is ready for the market. Rubies of Burma are not exported to any large extent, and then only stones of inferior value. But a pink spar found in the ruby district is a more important item of export. It is believed to be used for one of the classes of distinctive mandarin cap-knobs. Great numbers of these gems are brought down to Rangoon for sale, but a heavy price is always demanded for them, and it requires an experienced eye to purchase them with a view to profit. Topazes are also found in the vicinity of the rubies and sapphires, but they are scarce, and fetch a higher price in Burma than they would realize in England.

Recently, rubies and sapphires have been found in Siam, about four days' journey from Bangkok, in a very feverish locality. The stones, though inferior to those obtained in Upper Burma, are said by the Burmese to be so plentiful near Bangkok, that even women are anxious to proceed to the mines.

Ceylon ruby is a term applied in England to the garnets and carbuncle which come from Siam through Ceylon, and also to peculiar tinted almandines. The stones are of a rich red tinged with yellow. They are superior to those of the mine of Zobletz in Silesia, from the Tyrol, and from Hungary. Under the designation Ceylon rubies, jewellers obtain a large price for them from the ignorant. A stone of a fine rich tint, free from flaws, of a certain size, will range from £8 to £10.

Balas ruby is a term used by lapidaries to designate the rose-red varieties of spinel. Spinel is seen of all shades,—blood red, the proper spinel ruby ; rose red, the balas ruby ; orange or red rubicelle ; and voilet-coloured or almandine ruby.

Red tourmaline is sometimes mistaken for the ruby, and the pink topaz for the balas ruby. Spinel and balas rubies are found in Ceylon, Ava, Mysore, Baluchistan ; the spinel ruby is comparatively of little value, but they are often sold for a true ruby, and the true ruby is occasionally parted with as a spinel ruby.

Tavernier gives the figures of a ruby that belonged to the king of Persia. It was in shape and bigness like an egg, bored through in the middle, deep coloured, fair, and clean, except one flaw in the side. They would not tell what it cost, nor what it weighed ; only it had been several years in the treasury. He likewise gives the figure of a balas ruby, sold for such to Giafer Khan, uncle of the Great Moghul, who paid 9,50,000 rupees = 1,425,000 livres for it. But an old Indian jeweller affirming afterwards that it was no balas ruby, that it was not worth above 500 rupees, and that Gaifer Khan was cheated, and his opinion being confirmed by Shah Jahan, the most skilful in jewels of any person in the empire, Aurangzeb compelled the merchant to take it again, and to restore the money back. Tavernier gives also the figure of a ruby belonging to the king of Visapur. It weighed fourteen mangelin, or seventeen carats and a half, a Visapur mangelin being but five grains. It cost the king 14,200 new pagodas or 74,500 livres. Also, he figures a ruby that a Banya showed him at Benares ; it weighed 58 rati or 50¾ carat, being of the second rank in beauty, in shape like a plump almond bored through the end. He offered 40,000 rupees or 6000 livres for it, but the merchant demanded 55,000 rupees.

The largest oriental ruby known was brought from China to Prince Gargarin, governor of Siberia ; it afterwards came into possession of Prince Menzikoff, and now constitutes a jewel in the imperial crown of Russia."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 3. -- 1885. -- S. 449f.]

| 93a./b. śoṇaratnaṃ lohitakaḥ padmarāgo 'tha mauktikam 93c./d. muktātha vidrumaḥ puṃsi prabālaṃ puṃ-napuṃsakam

शोणरत्नं लोहितकः पम्द्मरागो

ऽथ मौक्तिकम् ।९३ क। [Bezeichnungen für Perle:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A pearl."

मौक्तिक - mauktika n.: Perle

Abb.: मौक्तिकानि । Die Tochter des Nizam, Hyderabad -

حیدرآباد, (heute:) Andhra Pradesh, 1890

[Bildquelle: Raja Lala Deen Dayal (1844 - 1905)]

मुक्ता

- muktā f.: Perle

Abb.: मुक्ताः । Bräutigam, New Delhi

[Bildquelle: Maja. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/maja-h/5207499893/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-22. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

"PEARL.

[...]

Pearls are found in several molluscs inhabiting shallow seas and sandbanks in the old and new world, but the most productive mollusc is the Meleagrina margaritifera or Avicula margaritifera, the pearl oyster ; and the best known localities are the Persian Gulf, the west coast of Ceylon in the Gulf of Manaar, Panama, the shores of California, Australia, Red Sea, Arabian coasts, the Aru Islands, Zebu, the Sulu Archipelago, Mindanao, coast of New Guinea, Torres Straits, Gulf of Omra, and coasts of Japan.

Friar Jordanus, a quaint old missionary bishop, who was in India in 1330, says that 8000 boats were engaged in this fishery and that of Ceylon, and that the quantity of pearls was astounding and almost incredible. The headquarters of the fishery was then, and indeed from the days of Ptolemy to the 17th century continued to be, at Chayl or Coil, literally, the temple, on the sandy promontory of Ramnad, which sends off a reef of rocks towards Ceylon, known as Adam's Bridge. And Ludovico di Varthema mentions having seen the pearls fished for in the sea near the town of Chayl, in about a.d. 1500 ; and Barbosa, who travelled about the same time, says that the people of Chayl are jewellers who trade in pearls. This place is, as Dr. Vincent has clearly shown, the Koru of Ptolemy, the Kolkhi of the author of Periplus, the Coll or Chayl of the travellers of the Middle Ages, the Ramana-Koil (temple of Rama) of the natives, the same as the sacred promontory of Ramnad and isle of Rameswaram, the headquarters of the Indian pearl fishery from time immemorial.

In Arabic poetry, pearls are fabled to be drops of vernal rain congealed in oyster shells. Benjamin of Tudela says that in the month of March the drops of rain-water which fall on the surface of the sea are swallowed by the mothers-of-pearl, and carried to the bottom of the sea, where, being fished for and opened in September, they are found to contain pearls. The Hindus poetically describe them as drops of dew falling into the shells when the molluscs rise to the surface of the sea in the month of May, and becoming, by some unexplained action of the sun's rays, transformed into pearls. Pliny and Dioscorides believed that pearls were productions of dew ; but that observant old Elizabethan navigator, Sir Richard Hawkins, shrewdly remarked that 'this must be some old philosopher's conceit, for it cannot be made probable how the dew should come into the oyster.'

[...]

In whatever way produced, pearls of considerable size, on account of their beauty and rarity, have been valued at enormous prices in past ages, and are still among the choicest objects of the jeweller's art. Their delicate and silvery lustre has been as widely celebrated as the brilliance of the diamond. The Meleagrina margaritifera furnishes the finest pearls and finest nacre. When secreted in the globular form, it is the pearl ; on the inner walls of the shell, it is the nacre. A pearl, to be pure, should be of perfect whiteness, be spherical or of a regular pear shape; those of blue reflection are less valued, and the yellow pearls still less. Tavernier was of opinion that the yellow colour was a stain from the rotting mollusc.

The pearl mollusc multiplies by means of what technically called spat or spawn, which is thrown out in sonic years in great quantities, —perhaps similar to the edible oyster of Britain,´which threw much spat in 1849, and not again until 1860, and not then up at least to 1866. The pat floats in and on the water, and attaches itself to anything it comes in contact with, attaining, it is said, the size of a shilling in six months. In its seventh year the pearl mussel attains its maturity as a pearl producer; pearls obtained from a seven-year mussel being of double the value of those from one of six years of age. In mussels under four years the pearls are not of any mercantile value, and after seven years the pearls deteriorate. Those from mussels of about four years old have a yellow tinge, and the older kinds a pinky hue ; but pearls of a red and even black, as also with other colours, are likewise met with.

Of all the substances used for personal decoration, the pearl alone derives nothing from art. The Baghdad dealers prefer the round white pearl. Those of Bombay esteem pearls of a yellow hue and perfect sphericity. According to European taste, a perfect pearl should be round or drop-shaped, of a pure white, slightly transparent, free from specks, spots, or blemish, and possess the peculiar lustre characteristic of the gem. In India and China, the bright yellow colour is preferred. The rose-tinted pearl of Scotland is in large esteem amongst Paris ladies. The pearls of Scotland of the best kind range in price from £5 to £50, but £100 has been paid for a fine specimen. Pearls of the Persian Gulf and Ceylon realize from Rs. 1000 to Rs. 1500 a tola of 180 grains.

A pair of very fine black pearls was recently sold to a rich iron merchant in Paris for 500,000 francs. The pink pearl ranks with the clear white pearl in value. Some specimens have been found with purple, cream, and salmon colours.

Pearls are designated in Europe by their colours, white, yellow, or black ; or by their size, as seed-pearl. The best pearls are of a clear, bright whiteness, free from spots or stains, with the surface naturally smooth and glossy. Those of a round form are preferred, but the larger pear-shaped ones are esteemed for ear-rings, Seed-pearls are those of the smallest size.

The dealers in Ceylon recognise twelve classes, in none of which is the actual weight taken into consideration

Called Ani, comprising those pearls to which Pliny first applied the term 'unio,' in which all the highest perfections of lustre and sphericity are centred ;

Anathari are such as fail a little in one point, either in lustre or sphericity ;

Sanadayam, and

Kayeral, such as fail in both ;

Massagu, or confusion;

Vadivu, beauty;

Medangu, bent or 'folded ' pearls ;

Kurwal, double pearls ;

Kalippu, signifying abundance ;

Poesal, and

Kural, mis-shapen. These find a ready sale in India, all kinds and shapes being indiscriminately used to adorn the roughly made breastplates of gold worn by women of high caste.

Thool, literally 'powder.' These are all easily disposed of in India, where they are sometimes made into lime to chow with betle.

Pearls arc found in the Unio marginalis, Lam., and Unio flavidus, Benson, of the Bhandardali lake near Berhampore.

In the salt-water inlets along the entire seacoast of Sind, a thin-shelled variety of the oyster occurs on the sandbanks, called Kenjur, that are left dry at low tides, but chiefly in the creeks near Kurachee, a seed-pearl is found, selling at Rs. 15 the tola. The seed-pearl fishery was let by the Amirs successively for Rs. 650, Rs. 1300, and Rs. 19,000. After 1839, they let them out for Rs. 1100, Rs. 21,000, and Rs. 35,000, but the contractors failed.

The produce of the fisheries in the Gulf of Manaar has varied greatly at long intervals. From 1838 to 1854 there was no fishery at all. A similar interruption had been experienced between 1820 and 1828. The Dutch had no fishery for 27 years, from 1768 to 1796 ; and they were equally unsuccessful from 1732 to 1746. It has now been satisfactorily proved that the pearl-oysters occasional disappearance is perfectly natural. The Arabs of the Persian Gulf, according to Colonel Pelly, attribute the decay of the Sind and Ceylon fisheries to the mixture of mud and earthy substance with the sand of the beds.

In the Persian Gulf the pearl banks extend 300 miles in a straight line, and the best beds are level and of white sand, overlying the coral in clear water ; and any mixture of mud or earthy substance with the sand is considered to be detrimental to the pearl mollusc. These banks are from 3 to 6 miles off shore, in 6 to 7 fathoms water. 400 boats of all sizes are annually employed, carrying crews of from 13 to 25 persons, half of them divers. The yearly produce was estimated at 40,000 tomans, each toman 18 piastres Rumi. —the masters drawing three shares, divers two shares, and assistants one share. Some of the Arab colonies on the Persian littoral retain a right to fish on the banks, which are appanages of the parent Arabian tribe.

In the Persian Gulf there is both a spring and a summer fishery, and as many as 5000 boats will assemble from Bahrein and the islands, and continue fishing from April to September. The total amount derived in the pearl fisheries of the Persian Gulf has been estimated at £400,000, employing about 30,000 persons. During a recent year, 30 divers engaged in the pearl fishery in the Persian Gulf lost their lives, most of them being victims of sea monsters. The value of the pearls taken in 1879 in the Persian Gulf was set down at about £300,000. There were 7,000,000 fished, and it was believed that but for the frequent interruption by weather, 2,000,000 more might have been lifted.

Off the coast of Ceylon the fishing season is inaugurated by numerous ceremonies, and the fleet, sometimes of 150 boats, then puts to sea. Each boat has a stage at its side, and is manned by ten rowers, ten divers, a steersman, and a shark charmer (Pillal karras). The men go down five at a time, each expediting his descent by means of a stone 20 to 25 lbs. in weight, and. holding their nostrils, gather into a net or basket about 100 shells in the minute or so which they remain under water. Each man makes 40 to 50 descents daily. The pearl -oysters are thrown on the beach and left to putrefy. It has been ascertained that no diving apparatus could, with any advantage, be substituted. The common time for remaining under water is 50 or 60 seconds, but Sir Henry Ward timed one man at 80 seconds, and another at 84 seconds. When the oysters reach the Government kottus, they are divided into four heaps. The divers then remove their share, and the remaining three-fourths, belonging to Government, divided into heaps of 1000 each, are sold by auction to the highest bidder. Sir Henry Ward says,—I have seen myself 32 pearls taken out of one oyster, three of which were worth £1 a piece, while even the smallest had a marketable value.

Pearl banks dot the coast from the sandy island of Rameswaram southwards to the mouth of the Tambraparni river.

In 1881, about 27 millions of oysters were fished, which were sold for an average of Rs. 33 per 1000, about 3000 men being employed at the work. About the year 1794, the Madras Government undertook the management of the pearl fisheries on the S.E. coast of the Peninsula, and in the 83 years realized about 12 lakhs of rupees, their annual expenditure being about Rs. 6000.

[...]

The larger pearls are considered the more valuable.

[...]

The prices of the smaller-sized pearls, like those of the smaller-sized diamonds, are rapidly Hill casing. A pearl of 3 grains will cost about £; a pearl of 30 grains, £110. The Imam of Muscat has one worth £32,000. "

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 168ff.]

"PEARLS AND CORAL. Sans. मुक्ता Muktā, Pearls. प्रवाल Pravāla, Coral.

THESE gems have been used in medicine from a very ancient period and are mentioned by Susruta. Pearls are purified by being boiled in the juice of the leaves of Sesbania aculeata (jayanti), or of the flowers of Agati grandiflora (vaka). Coral is purified by being boiled in a decoction of the three myrobalans. Both are prepared for medicinal use by being calcined in covered crucibles and then reduced to powder. The properties of both these articles are said to be alike and they are generally used in combination. They are said to be useful in urinary diseases, consumption etc, and to increase the strength, nutrition, and energy of weak persons."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 93.]

| 93c./d. muktātha vidrumaḥ puṃsi prabālaṃ puṃ-napuṃsakam मुक्ताथ विद्रुमः पुंसि प्रबालं पुं-नपुंसकम् ।९३ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Koralle:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Coral."

विद्रुम - vidruma m.: "absonderlicher Baum", Koralle

Abb.: विद्रुमः । Kanyakumari - கன்னியாகுமரி,

Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: wildxplorer. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/krayker/2117971591/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-22. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

प्रबाल - prabāla m., n.: Schoß, Trieb, Zweig, Koralle

Abb.: प्रबालः । Batticaloa (மட்டக்களப்பு

/ මඩකලපුව), Sri Lanka

[Bildquelle: Danushka Senadheera. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/advanture_srilanka/4834500777/. -- Zugriff

am 2011-09-22. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

| 94a./b. ratnaṃ maṇir dvayor aśmajātau muktādike 'pi ca रत्नं मणिर् द्वयोर् अश्मजातौ मुक्तादिके ऽपि च ।९४ क। Korallen und andere auf Stein Gewachsene heißen:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Any gem."

रत्न ratna n.: Juwel

Abb.: रत्नानि । Khambhat - ખંભાત, Gujarat

[Bildquelle: The National Labor Committee. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/nlcnet/4401722056/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-22. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

"These gemstones are grinded in India and sold for large profits in the U.S.

and Europe."

मणि - maṇi m., f.: Juwel, Edelstein

Abb.: मणयः । Bangalore - ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು,

Karnataka

[Bildquelle: najeebkhan. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/42429527@N03/3984963296/in/photostream/. --

Zugriff am 2011-09-22. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

"The precious stones described are,

- Hīraka, diamond ;

- Gārutmat, emerald;

- Puṣparāga, topaz;

- Māṇikya, ruby;

- Indranīla, sapphire;

- Gomeda, a yellow gem of the colour of fat;

- Vaidūrya, a gem of a dark blue colour, the lapis lazuli;

- Mauktika, pearls;

- Vidruma, corals.

Collectively they are called Navaratna or the nine gems. Rājavarta, an inferior kind of diamond from Virat, and Vaikrānta, another inferior kind of diamond, are sometimes used instead of diamond."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 23.]

| 94c./d. svarṇaṃ suvarṇaṃ kanakaṃ hiraṇyaṃ hema-hāṭakam 95a./b. tapanīyaṃ śātakumbhaṃ gāṅgeyaṃ bharma karburam 95c./d. cāmīkaraṃ jātarūpaṃ mahārajata-kāñcane 96a./b. rukmaṃ kārtasvaraṃ jāmbūnadam aṣṭāpado 'striyām

स्वर्णं सुवर्णं कनकं हिरण्यं हेम-हाटकम् ।९४

ख। [Bezeichnungen für Gold:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Gold."

स्वर्ण - svarṇa n.: Schönfarbiges, Gold

Abb.: स्वर्णम् । Harmandir Sahib (ਹਰਿਮੰਦਰ ਸਾਹਿਬ), Amritsar -

ਅੰਮ੍ਰਿਤਸਰ, Punjab,

vergoldet vor 1830

[Bildquelle: Oleg Yunakov / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: स्वर्णम् । Schlagen von Blattgold, Mandalay -

မန္တလေးမြို့, Myanmar

[Bildquelle: Damien Halleux Radermecker. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dayapragm/4350796844/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-28. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

सुवर्ण - suvarṇa n.: Schönfarbiges, Gold

Abb.: सुवर्णम् । Buddhistisches Reliquiar, gestiftet von Kaniṣka (Κανηϸκι),

Peshawar (پشاور),

Pakistan, 2. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Teresa Merrigan / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

कनक - kanaka n.: "Glänzendes", Gold

Abb.: कनकम् । Männermantel, Moghul, Indien, frühes 18. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: airforceJK. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/35663527@N06/3305001609. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-27. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

हिरण्य - hiraṇya n.: Gold, Reichtum

Abb.: हिरण्यम् । Ohrringe, die über 100 Gramm wiegen, Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: sowrirajan s. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/sowri/1144968763/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-27. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

हेमन् - heman n.: Gold

Abb.: हेम । Matrimandir (मातृमन्दिर), Auroville -

ஆரோவில்,

Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: Sujit kumar / Wikimedia. --

Creative