|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 15. vaiśyavargaḥ (Über Vaiśyas). -- 13. Vers 100 - 106b: Handel IV: Handelsgüter II:

Farben, Nichtedelmetalle etc.. -- Fassung vom 2011-10-04. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa7/amara215m.htmErstmals hier publiziert: 2011-10-04

Überarbeitungen:

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener,

gut ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener,

gut ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

| 100a./b. kṣāraḥ kāco 'tha capalo rasaḥ sūtaś ca pārade क्षारः काचो ऽथ चपलो रसः सूतश् च पारदे ।१०० क। [Bezeichnungen für Glas:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Glass."

"Glas, eine durch Schmelzen erzeugte, bei hoher Temperatur dickflüssige, beim Erkalten allmählich aus dem zähflüssigen in den starren Zustand übergehende, vollständig amorphe Masse, die gewöhnlich aus Verbindungen der Kieselsäure mit mindestens zwei Basen (deren eine nur ausnahmsweise kein Alkali) besteht und in Wasser unlöslich ist. " [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

क्षार - kṣāra m.: "ein brennender, ätzender Stoff; besonders Ätzkali, Salpeter, Natrum, Pottasche u.s.w." (PW), Glas

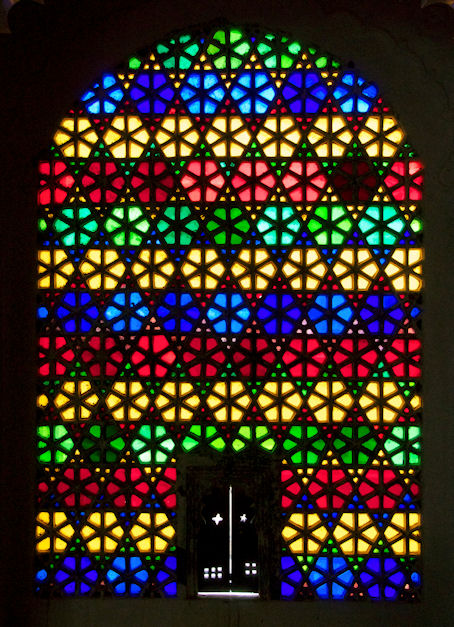

Abb.: क्षारः । Fenster, Bagore-ki-Haveli, Udaipur - उदयपुर, Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: Jon Connell. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ciamabue/4571277803/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-28. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

काच - kāca m.: Glas

Abb.: काचाः । Rāja mit Weingläsern und Weinflasche, Nagaur - नागौर,

Rajasthan, ca. 1700

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4838357000/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-27. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

"The basis of all glass is silica and alkali, of which the former, in the shape of common sand, is to be met with almost everywhere ; the latter is to be had cheaply and in abundance in most parts of India. The secondary materials also, indirectly essential to the manufacture of the best quality of glass, namely the fireclays used in the construction of the furnaces, are abundant, and of very superior descriptions. Yet with all these advantages the natives do not appear to have advanced in the manufacture beyond the first and very rudest stages ; and although it is one which, if successfully prosecuted, would probably meet with very extended encouragement, the manufacture of the commonest bottles is not yet practised. The chief defects of the native manufacture are the use of too large a quantity of alkali ; in fact, in some cases, it is so much in excess, that it might be tasted by applying the tongue to the article. The fault now remarked upon is probably connected with and caused by another, that of the material being melted at too low a temperature and in too small bulk ; and these again probably arise from the use of an improper furnace and an unsuitable kind of fuel. The native furnace is usually a rude hole dug in the ground, coated with ferruginous clay, which tends to discolour the glass, and the heat is raised by the use of bellows blast. Hence the temperature is confined to one point of the mass, and is insufficiently diffused while the body of metalunder fusion being small, and the dome and sides above ground being thin, the heat is dissipated from them, and never attains body and elevation sufficient to admit of the mass setting and purifying itself, or of its being freed from air-bubbles by the addition of the proper proportion of silica. What is required is the preparation of the glass in larger quantities at a time, and with this view larger and more carefully constructed furnaces, on the reverberating principle, to be heated by coal ; after this, that the process should be attended to more scrupulously, and the materials mixed by weight, instead of being thrown together by measure, as is too commonly the case at present.

Country glass is usually made of dhobi's earth, a crude carbonate of soda, with a mixture of a little potash and lime 60 to 70 parts, and yellowish white sand 30 to 40 parts, composed of small fragments of quartz, felspar, iron, and a trace of lime. In 100 parts, for good bottle glass of Europe, are needed sand 58, sulphate of soda 29, lime 11½, charcoal 1½.

Sulphate of soda only contains 45 per cent, of alkali, so that 29 parts contain 13 ; while the carbonate of soda obtained from dhobi's earth contains between 30 and 40 per cent, of alkali, according to which the alkali used by the natives of India would be to that employed in Europe in the proportion of 23 to 13.

The substances generally used by the natives in colouring glass are iron, which gives green, brown, and black shades ; manganese for pink, purple, and black ; copper for blue, green, and deep red ; arsenic for white ; and chromate of iron for a dull green. Bangles for the wrist are the chief articles now made in India, and some of the colours in the Bombay bazar are exquisite. [...]

The art of glass-making is yet in its extreme infancy in the Panjab. The glass sand occurs in the form of a whitish sand, mixed with an alkali, which effloresces naturally. It is there called reh ; that only of a good white colour makes glass. This substance is identical with the alkaline efflorescence which appears in many parts, and whose presence is destructive to cultivation. Wherever such an efflorescence occurs over clean sandy soil, there is naturally formed a mixture of sand and alkali, which fuses into coarse lamps of bottle-green glas.

Glass Beads. [...]

Coloured glass beads are largely worn in India by several non-Aryan races."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 1211.]

| 100a./b. kṣāraḥ kāco

'tha capalo rasaḥ sūtaś ca pārade क्षारः काचो ऽथ चपलो रसः सूतश् च पारदे ।१०० क। Bezeichnungen für पारद - pārada m.: Quecksilber:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Quicksilver."

पारद - pārada m.: Quecksilber

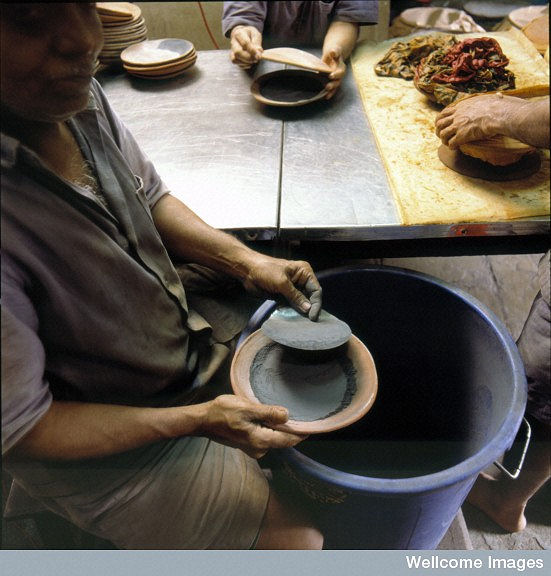

Abb.: पारदः । Quecksilbergewinnung, Zandu Realty Limited,

Mumbai - मुंबई, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Mark de Fraeye / Wellcome Images. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

"From the seventh century AD onwards, mercury became the principal ingredient in ayurvedic alchemy (rasayana). mercury is even today prepared from cinnabar (mercuric sulphide, HgS) and detoxified by incinerating in an hourglass-shaped furnace of clay."

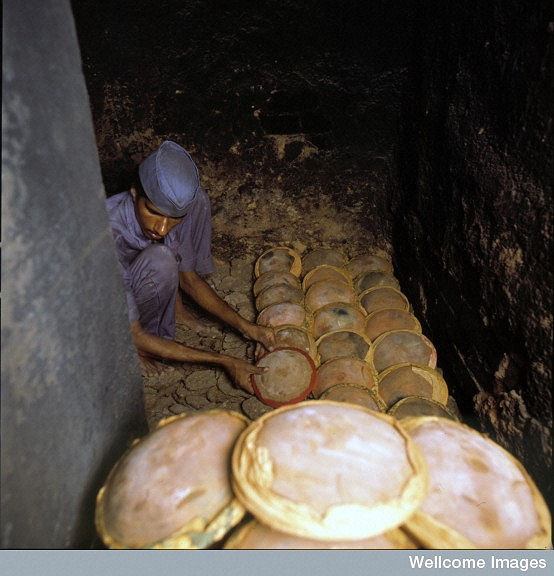

Abb.: पारदः । Quecksilbergewinnung, Zandu Realty Limited,

Mumbai - मुंबई, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Mark de Fraeye / Wellcome Images. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

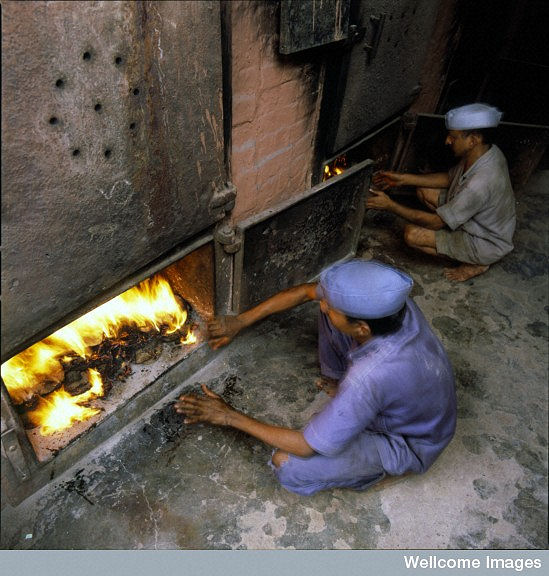

Abb.: पारदः । Quecksilbergewinnung, Zandu Realty Limited,

Mumbai - मुंबई, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Mark de Fraeye / Wellcome Images. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: पारदः । Quecksilbergewinnung, Zandu Realty Limited,

Mumbai - मुंबई, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Mark de Fraeye / Wellcome Images. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

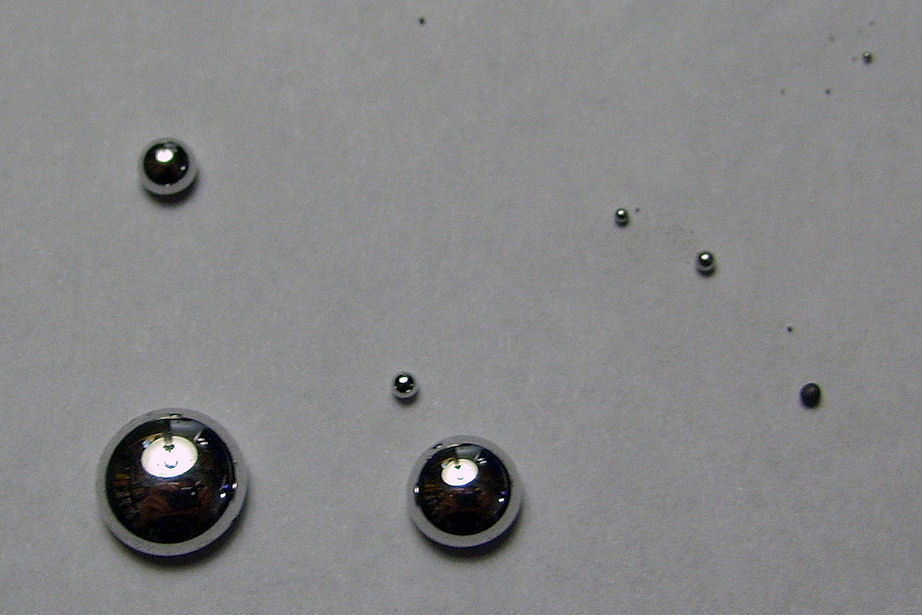

चपल - capala m.: Beweglicher, Quecksilber

Abb.: चपलः । Quecksilbertropfen (Hg)

[Bildquelle: p.Gordon. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/pgordon/4097094562/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-28. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

रस - rasa m.: Flüssigkeit, Quecksilber

Abb.: रसः । Quecksilber (Hg) bei Zimmertemperatur

[Bildquelle: Bionerd / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

सूत - sūta m.: "Geborener, in Bewegung Gesetzter", Quecksilber

Abb.: सूतः । Quecksilber auf dem Muttergestein Cinnabarit

[Bildquelle: Parent Géry / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"Quecksilber (altgr. ύδράργυρος Hydrargyros ,flüssiges Silber‘, davon abgeleitet das lat. Wort hydrargyrum (Hg), Name gegeben von Dioskurides) ist ein chemisches Element im Periodensystem der Elemente mit dem Symbol Hg und der Ordnungszahl 80. Obwohl es eine abgeschlossene d-Schale besitzt, wird es häufig zu den Übergangsmetallen gezählt, im Periodensystem steht es in der 2. Nebengruppe (Gruppe 12) oder Zinkgruppe. Es ist das einzige Metall und neben Brom das einzige Element, das bei Normalbedingungen flüssig ist. Aufgrund seiner hohen Oberflächenspannung benetzt Quecksilber seine Unterlage nicht, sondern bildet wegen seiner starken Kohäsion linsenförmige Tropfen. Es ist wie jedes andere Metall elektrisch leitfähig." [Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quecksilber. -- Zugriff am 2011-09-21]

"Mercury or quicksilver was known to the ancients. The Romans and Arabs seem to have employed it as a medicine externally, and the Hindus prescribed it internally. It is found in China, at Almaden in Spain, at Idria in Carniola, and likewise in S. America. Mercury was found by Dr. J. P. Malcolmson in the lava of Aden and in the laterite on the western coast of the Peninsula of India. It occurs usually as the native bisulphuret or cinnabar, combined with silver, forming a native amalgam ; or with chlorine, as in horn mercury. It is chiefly obtained from the sulphuret by distillation with lime or with iron, which, combining with the sulphur, the metal distils over and is condensed. Quicksilver is said to be brought to Ava from China.

Bichloride of Mercury, corrosive sublimate. Hydrargyri bichloridum. This is white, with an acrid, metallic, and persistent taste, without smell. It is met with in small crystals, or in semi-transparent masses. It is made in many parts of British India, and seems to have been long known to and prepared by the natives of India. It is much used as a preservative of timber, canvas, etc., from the ravages of mildew, the dry rot, and of white ants. A solution is made in the proportion of one pound to four gallons of water, and in this the article to be protected is steeped a variable time, according to its nature.

Chloride of Mercury. Hydrargyri chloridum. Calomel. Several preparations of mercury are described by the Sanskrit and Tamil writers. Dr. O'Shaughnessy examined the processes, and found that they generally led to the production of a mixture of calomel and corrosive sublimate. The ras-karpur is usually calomel. Once, however, he met a specimen which was corrosive sublimate of the finest kind.

Russapuspum, in great repute amongst the Tamil people, appears to be administered by them in larger doses than any other preparations of this metal. But it generally happens that through defective manipulation a mixture of calomel and bichloride is formed.

Shavirum is a strange compound, administered by the Tamils in very small quantities ; is a harsh, uncertain, and dangerous preparation. In the mode of preparing it, the vapours of calomel simultaneously rising and meeting the chlorine are converted into the bichloride of mercury."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 2. -- 1885. -- S. 929.]

"MINERAL or inorganic medicines are generally described under five heads, namely. Rasa or mercury which forms a class by itself [...]"

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 23.]

"MERCURY.

Sanskrit पारद, रस

Mercury, though not mentioned by Charaka and Susruta, has in later days come to be regarded as the most important medicine in the Hindu Pharmacopoeia. Pārada literally means that which protects, and mercury is so called because it protects mankind from all sorts of diseases. It is said that the physician who does not know how to use this merciful gift of God is an object of ridicule in society.

Good mercury is said to be bright like the mid-day sun externally, and of a bluish tinge internally. Mercury of a yellowish-white, purple, or variegated colour should not be used in medicine. Mercury, as met with in commerce, contains several sorts of impurities, such as tin, lead, dirt, stone, etc. If administered in an impure state it is said to bring on a number of diseases ; hence it is purified before use. Various processes for purifying mercury are described in books. At the present day the following is generally adopted by Kavirājas. Mercury is first rubbed with brick-dust and garlic, then tied in four folds of cloth and boiled in water over a gentle fire for three-hours in an apparatus called Dolā yantra. When cool, it is washed in cold water and dried in the sun. Some practitioners use betle-leaves instead of garlic for rubbing the mercury with. Mercury obtained by sublimation of cinnabar is considered pure and preferred for internal use. Cinnabar is first rubbed with lemon juice for three hours, and then sublimed in the apparatus called Urddliapātana yantra. The mercury is deposited within the upper pot of the apparatus, in form of a blackish powder. This is scraped, rubbed with lemon-juice and boiled in water, when it is fit for use. A peculiar form of mercury called Shadguna ball jārita rasa is thus prepared. A little sulphur is placed in an earthen pot, and over it some mercury. The pot is heated in a sand-bath, and, as the sulphur begins to melt, cautiously and gradually more of it is added to or placed over the mercury, altogether to the extent of six times the weight of the mercury. When the whole is melted like oil the pot should be quickly removed from the fire, aud cooled till the mass is consolidated. It should then be broken, and the mercury extracted from within the mass. Mercury thus obtained is said to be superior to all other forms, but it is not much used at present.

The purified metal obtained by the processes above mentioned is employed for the preparation of mercurial compounds. Four preparations of mercury are described in books, namely, black, white, yellow, and red, called respectively, krishna, sveta, pīta and rakta bhasmas,

1. Krishna bhasma. The black preparation is the black sulphide of mercury, made by rubbing together and dissolving over the fire three parts of mercury with one of sulphur.

2. Rasakarpura. The white preparation is the Rasakarpura or perchloride of mercury. Several processes are given for preparing it; one is as follows. Take of mercury and chalk equal parts, and rub them together till the globules disappear. Rub this mixture of chalk and mercury with pānsu (salt obtained from saline earth) and the juice of Euphorbia nereifolia (snuhi) repeatedly. Enclose in a covered crucible and heat it within a pot full of rock salt. The perchloride of mercury will be deposited in the shape of a pure white powder under the lid of the crucible. The Bhāvaprakāsa gives the following process for its preparation. Take of purified mercury, gairika (red-ochre) , brick dust, chalk, alum, rock salt, earth from ant-hill, kshāri lavana (impure sulphate of soda) and bhāndaranjaka, or red earth used in colouring pots, in equal parts, rub together and strain through cloth. Place the mixture in an earthen pot, cover it with another pot, face to face, and lute the two together with layers of clay and cloth. The pots so luted are then placed on fire, and heated for four days, after which they are opened, and the white camphor-like deposit in the upper pot is collected for use.

3. Pīta bhasma. The yellow preparation called Pīta bhasma is directed to be prepared as follows. Take of mercury and sulphur equal parts, rub them together for seven days with the juice of bhumyāmalaki (Phyllanthus neruri) and hastisundi (Heliotropium Indicum). Place the mixture in a covered crucible, and heat it in a sand-bath for twelve hours. The result will be a yellow compound.

4. Rakta bhasma. The red preparation called Rakta bhasma or Rasa sindura is prepared in a variety of ways- The following is one of them. Take of mercury and sulphur equal parts, rub together with the juice of the red buds of Ficus Bengalensis (vata) for three days successively, introduce the mixture within a bottle and heat it in a sand-bath for twelve hours. A red deposit will adhere belowthe neck of the bottle. It is taken out in the shape of dark red shining scales.

The four preparations of mercury above mentioned, though described in most works on metalic medicines, are not, practically used in the treatment of disease under these names. In the present day the yellow preparation is not in use. The white form called Rasakarpura is now prepared, not according to the processes described in Sanskrit works, but by subliming the black sulphide of mercury with common or rock salt. In this form it is largely manufactured and sold in all the bazars. The red preparation is better known as Rasa sindura ; and the black one as Rasa parpati. In fact, practically, prepared mercury means the red preparation or Rasa sindura and this is the form in which it is largely used. Besides this, the black and red sulphides of mercury are also used internally. The black sulphide is prepared by rubbing together equal parts of sulphur and mercury till the globules disappear. It is called Kajjali. The red sulphide or cinnabar is called hingula. These four preparations, namely, cinnabar, the black sulphide called Kajjali, the red preparation called Rasasindura, and the Rasakarpura of the bazar, are the four principal forms in which mercury is used in Hindu medicine ; that is, they constitute the basis of all the formulae containing mercury.

Mercury is said to be imbued with the six tastes, and capable of removing derangements of all the humours. It is the first of alterative tonics. Combined with other appropriate medicines it cures all diseases, acts as a powerful tonic and improves the vision and complexion.

In fevers of all descriptions, mercury is extensively used in combination with aconite, croton seed, datura, and other medicines."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 27 - 31.]

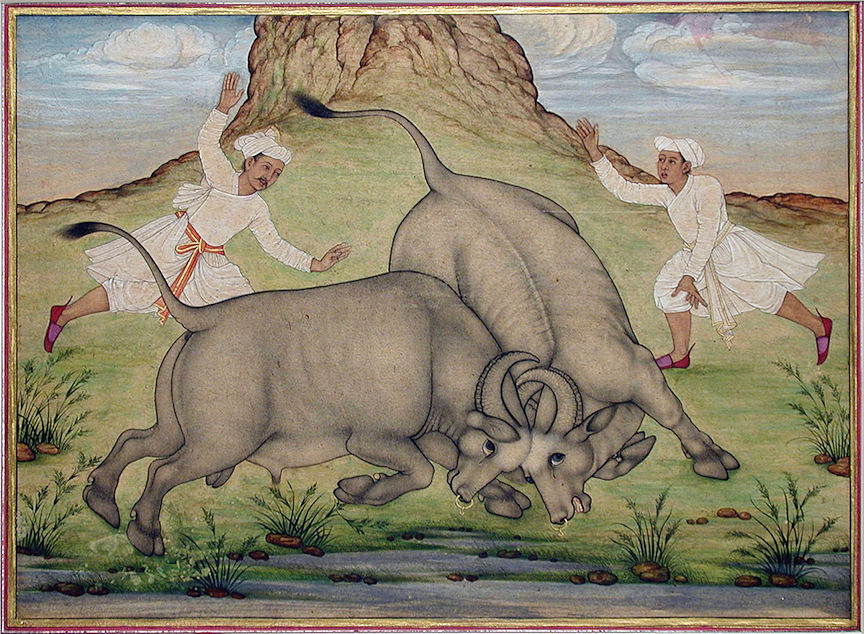

| 100c./d. gavalaṃ māhiṣaṃ śṛṅgam abhrakaṃ girijāmale गवलं माहिषं शृङ्गम् अभ्रकं गिरिजामले ।१०० ख। Das Horn eines Wasserbüffels heißt गवल - gavala n.: Büffelhorn |

Colebrooke (1807): "Buffalo's horn."

गवल - gavala n.: Büffelhorn

Abb.: गवलानि । Faizabad -

فیض آباد, Uttar Pradesh

[Bildquelle: The San Diego Museum of Art Collection. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/thesandiegomuseumofartcollection/6124595675/.

-- Zugriff am 2011-09-28. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: गवले । Goa

[Bildquelle: Roland van Stokkom. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dutch-tiger/4401554319/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-28. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

| 100c./d.

gavalaṃ māhiṣaṃ śṛṅgam abhrakaṃ

girijāmale गवलं माहिषं शृङ्गम् अभ्रकं गिरिजामले ।१०० ख। [Bezeichnungen Talk und Glimmer:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Talc."

"Talk, Mineral, sehr ähnlich dem Glimmer und Chlorit, zumal in der vollkommenen Spaltbarkeit nach einer Fläche (Basis), kristallisiert wahrscheinlich wie jene monoklin, bildet aber nur selten sechsseitige tafelförmige Kristalle, gewöhnlich in blätterigen und schuppigen, auch dichten Aggregaten, weiß, grünlich oder gelblich, auch farblos, in dünnen Blättchen durchscheinend, mit Perlmutter- oder Fettglanz auf der Basis, sehr mild und fettig anzufühlen. Härte 1, spez. Gew. 2,69–2,80. T. besteht aus kieselsaurer Magnesia H2Mg3Si4O12 mit etwas Eisenoxydul. Nach dem Glühen wird er hart (Härte 6) und ritzt das Glas. Ein dichter, kryptokristallinischer T. ist der Speckstein (Steatit)." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

"Glimmer, monoklin kristallisierende, scheinbar aber hexagonal entwickelte wasserhaltige Silikate von Tonerde und Kali (oder Natron), vielfach mit Magnesia und Eisenoxydul, Mineralien mit ausgezeichneter basischer Spaltbarkeit. Hauptarten: Kali-G. (Mica, Muskovit), silberweiß, ein wesentlicher Gemengteil vieler Gesteine (Gneis, Glimmerschiefer, Granit etc.); der in großen Tafeln auftretende Muskovit Rußlands dient zu Fensterscheiben, Lampenzylindern etc., gepulvert als Streusand. Magnesia-G. (Biotit, Meroxen), dunkel gefärbt, stark pleochroitisch, weit verbreitet. Seltenere Glimmerarten sind: Anomit, Phlogopit, Lepidomelan, Zinnwaldit (Lithion-G.), Lepidolith, Paragonit (Natron-G.), Margarit (Kalk-G.)." [Quelle: Brockhaus' Kleines Konversationslexikon, 1906. -- s. v.]

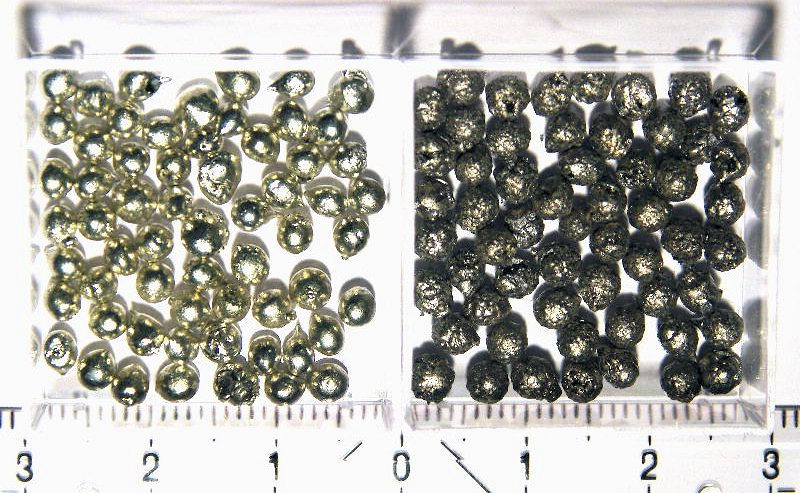

"The Uparasas used [in Indian medicine] are

- sulphur,

- talc or mica,

- two sorts of iron pyrites called Suvarṇamākṣika and Tāramākṣika,

- loadstone,

- orpiment,

- realgar,

- sulphate of copper,

- sulphate of iron,

- cinnabar,

- minium or red lead,

- sulphuret of lead,

- calamine (kharpara),

- Silājatu (a bituminous substance containing iron),

- alum,

- borax,

- chalk,

- calcined cowries and conch shells,

- Gairika a sort of red mountain earth or ochre,

- Kaṅkuṣṭha a sort of mountain earth,

- Saurāṣṭri a fragrant earth from Surat,

- sand,

- clay,

- etc."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 23.]

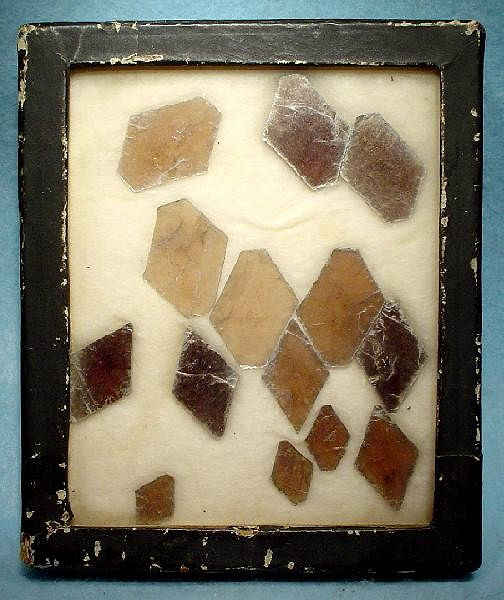

अभ्रक - abhraka n.: Talk (zu abhra n.: Wolke)

Abb.: अभ्रकम् । Talk

[Bildquelle: Ra'ike / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: अभ्रकाणि । Verschiedene Glimmer, USA

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikimedia. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

गिरिज - girija n.: aus dem Berg Entstandenes, Talk

Abb.: गिरिजम् । Talk, Deutschland

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

अमल - amala n.: Fleckenloses, Glänzendes, Talk

Abb.: अमलम् । Talk, Slovakei

[Bildquelle: Pelex / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"MICA OR TALC. Sans. अभ्र, Abhra.

FOUR varieties of talc are described by Sanskrit writers, namely,

- white,

- red,

- yellow and

- black.

Of these the white variety is used as a substitute for glass in making lanterns etc, and the black variety called vajrābhra is used in medicine. It is of a black colour, hard and heavy, and generally known by the name of kṛṣṇābhra or sheābhra.

Talc is purified in the following manner. It is first heated and washed in milk. The plates are then separated and soaked in the juice of Amaranthus polygamus ( tandulia ) and kāñjika for eight days. Talc thus purified is reduced to powder by being rubbed with paddy within a thick piece of cloth, when the powdered talc passes through the pores of the cloth in fine particles and is collected for use. Talc, thus reduced to powder, is called dhānyābhraka. It is prepared for medicinal use by being mixed with cow's urine and exposed to a high degree of heat within a closed crucible, repeatedly for a hundred times. Sometimes the process is said to be repeated a thousand times. When this is the case, the preparation is called sahasra putita abhra and sold at high price (eight rupees per tola). It is considered to be of superior efficacy. Prepared talc is a powder of brick-dust colour and a saline, earthy taste. Chemically it consists of silicate of magnesia with iron in excess. It is considered tonic and aphrodisiac and is used in combination with iron in anaemia, jaundice, chronic diarrhoea and dysentery, chronic fever, enlarged spleen, urinary diseases, impotence etc. Its efficacy is said to be increased by combination with iron. Dose, grains six to twelve."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 76f.]

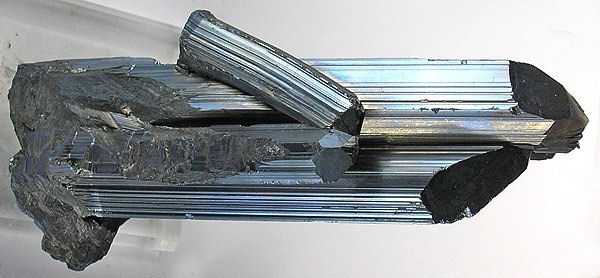

| 101a./b. srotoñjanaṃ tu sauvīraṃ

kāpotāñjana-yāmune स्रोतोञ्जनं तु सौवीरं कापोताञ्जन-यामुने ।१०१ क। [Bezeichnungen für Stibnit (Antimonsulfid) und Galenit (Bleiglanz):]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Antimony."

Die Inder machten meist keinen Unterschied zwischen Blei und Antimon.

Abb.: Galenit, USA

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Stibnit, China

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"Stibnit, auch unter den Namen Antimonit, Antimonglanz, Antimonsulfid oder Grauspießglanz bekannt, ist ein häufig vorkommendes Mineral aus der Mineralklasse der „Sulfide und Sulfosalze“. Er kristallisiert im orthorhombischen Kristallsystem mit der chemischen Zusammensetzung Sb2S3. Chemisch gesehen ist Stibnit damit ein Antimon(III)-sulfid (auch Antimontrisulfid), wenn man Antimon als Metall ansieht. Stibnit ist undurchsichtig und entwickelt meist kurze bis lange, prismatische, nadelige oder radialstrahlige Kristalle, aber auch massige Aggregate von bleigrauer Farbe und Strichfarbe. Die Stibnitkristalle sind typischerweise in Längsrichtung gestreift, zeigen im frischen Zustand einen ausgeprägten Metallglanz und können Längen bis über einem Meter erreichen.

[...]

Etymologie und GeschichteDas Mineral ist bereits seit der Antike bekannt und wurde als schwarzer Schminkpuder zum Färben von Augenlidern und Augenbrauen verwendet. Dunkel gefärbte Augenränder gelten in der arabischen Kultur als Schönheitsideal und zugleich als magisches Abwehrmittel. In der Antike Griechenlands wurde es zudem zur Herstellung von Bronze eingesetzt.

Im arabischen Sprachraum ist al-kuhl (arabisch الكحل, das Färbende) das Wort für den traditionellen arabischen Antimon-Schminkpuder. Francis Bacon führte 1626 in seiner "Sylva sylvarum; or a naturall historie" diesen aus einem Mineral erstellten Puder unter dem Begriff Alcohole auf.[2]"

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stibnit. -- Zugriff am 2011-09-28]

"Pastes of Sb2S3 powder in fat or in other materials have been used since 3000 BC as eye cosmetics in the Middle East and farther afield; in this use, Sb2S3 is called kohl. It was used to darken the brows and lashes, or to draw a line around the perimeter of the eye. [...] The natural sulfide of antimony, stibnite, was known and used in Biblical times, as a medication and in Islamic/pre-Islamic times as a cosmetic. The Sunan Abi Dawood (سنن أبي داود) reports, “prophet Muhammad said: 'Among the best types of collyrium is antimony (ithmid) for it clears the vision and makes the hair sprout.'”"

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stibnite. -- Zugriff am 2011-09-28]

"ANTIMONY, SULPHURET OF. [...]

This is obtainable in most eastern bazars, and is used medicinally by native physicians, and by Mahoraedan men for an eyelid application. Both ores of iron and manganese and lead are often sold as surma. It is obtained in Cornwall, Saxony, Spain, Mexico, Siberia, Chin-kiang-fu in China, the Eastern Islands, Siam, Pegu, Martaban, Amherst, and Beluchistan? but the best is from Sarawak, in Borneo, and from Vizianagram. Ter-sulphide of antimony is said to be found in the Salt Range near the Keura salt mine. Vast quantities of antimony have been found by Maj. Hay in the Himalayan range of Spiti. A sulphic of antimony is found at Jaggatsukh Kulu, in the Kangra district, and specimens were sent from Bajaur, and it has been found near Beyla by Major Boyd ; it occurs massive in Beluchistan

[...]

Butter of antimony is a substance sometimes used with sulphate of copper for bronzing gun barrel, the iron decomposing the chloride, and depositing a thin film of antimony on its surface. The chi alloys of antimony are type metal, consisting of 4 lead and 1 of antimony ; stereotype metal, lead and 1 antimony,—music-plates consisting of lead, tin, and antimony ; Britannia metal, consisting of 100 parts of tin, 8 antimony, 2 of copper, and 2 bismuth. Pewter is sometimes formed of 12 parts of tin and 1 part antimony. Antimony is also used in the preparation of some enamels and other vitreous articles, and much employed in modern medicine as antimonial powder and tartrate of antimony. James's powder is said to consist of 43 parts of phosphate of lime, and 57 of oxide of antimony."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 116f.]

"Bleiglanz, Galenit, PbS, reguläres, metallisch glänzendes, bleigraues Mineral, bestehend aus Bleisulfid, meist mit etwas Silber, Antimon etc. Wichtigstes Erz zur Gewinnung von Blei, auch zur Glasur der Töpferwaren, zur Verzierung von Spielwaren und zu Streichfeuerzeugen gebraucht." [Quelle: Brockhaus' Kleines Konversationslexikon, 1906. -- s. v.]

"GALENA. Sans. अञ्जन, Añjana. सौवीराञ्जन, Sauvīrāñjana.

Galena or sulphide of lead is called añjana or sauvirāñjana in Sanskrit, and kṛṣṇa surmā in Vernacular. It is called añjana, which literally means collyrium or medicine for the eyes, from the circumstance of its being considered the best application or cosmetic for them. The other varieties of añjana mentioned are srotoñjana, puṣpāñjana and rasāñjana.

सौवीराञ्जन Sauvīrāñjana is said to be obtained from the mountains of Sauvīra, a country along the Indus, whence it derives its name. The article supplied under its vernacular name surmā is the sulphide of lead ore. Surmā is usually translated as sulphide of antimony, but I have not been able to obtain a single specimen of the antimonial ore from the shops of Calcutta and of some other towns. The sulphide of antimony occurs in fine streaky, fibrous, crystalline masses of a radiated texture. The lead ore on the contrary, occurs in cubic masses destitute of rays and is tabular in its crystalline arrangement.

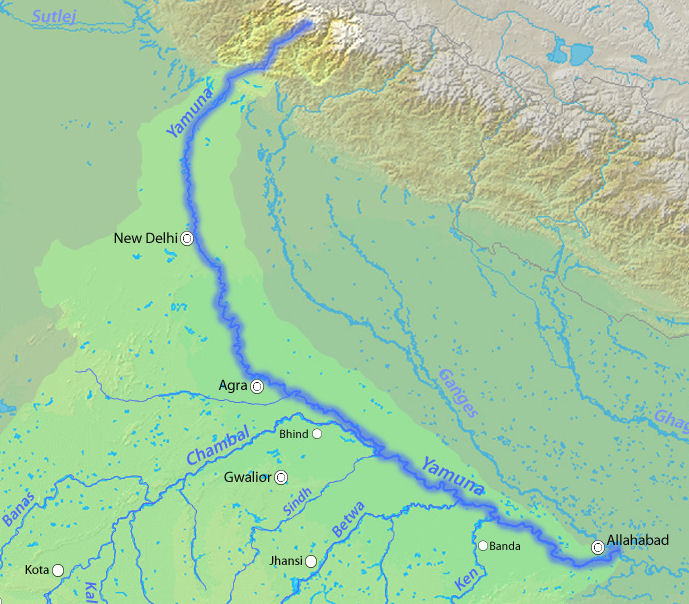

स्रोतोञ्जन Srotoñjana is described as of white colour, and is said to be produced in the bed of the Jamuna and other rivers. It is called saffed surmā in the vernacular, and the article supplied under this name by Hindustani medicine vendors is calcareous or Iceland spar. It is used as a collyrium for the eyes, but is considered inferior to the black surmā or galena.

पुष्पाञ्जन Puṣpāñjana is described as an alkaline substance. I have not met with any vernacular translation of this word, nor with any person who could identify or supply the drug. Wilson, in his Sanskrit-English Dictionary, translates the term as calx of brass, but I know not on what authority.

रसाञ्जन Rasāñjana is the extract of the wood of Berberis Asiatica called rasot in the vernacular. It will be noticed in its place in the Vegetable Materia Medica.

Sauvīrāñjana or galena is chiefly used as a cosmetic for the eyes, and is supposed to strengthen these organs, improve their appearance and preserve them from disease. It enters into the composition of some collyria for eye diseases. Galena, heated over a fire and cooled in a decoction of the three myrobalans for seven times in succession, is rubbed with human milk and used in various eye diseases.

Another collyriurn prepared with lead is as follows. To one part of purified and melted lead, add an equal portion of mercury and two parts of galena, rub them all together and reduce to powder. Now add camphor, equal in weight to one-tenth part of the mass and mix intimately. This preparation is said to be useful in eye diseases. From the composition and uses of lead and galena above described it would seem that by the term surmā the Hindus meant sulphide of lead, and not sulphide of antimony as is generally supposed."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 74ff.]

स्रोतोञ्जन - srotoñjana n.: "Fluss-Salbe", Galenit (Bleiglanz)

Abb.: स्रोतोञ्जनम् । Anbringen von Kajal (काजल

= Kohl = كحل ) an den Augen des

Bräutigams, Indien

[Bi8ldquelle: Maneesh Singh. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/maneeshks/366362761/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-28. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: स्रोतोञ्जनम् ।

[Bildquelle: Stuti Sakhalkar. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/theblackcanvas/3013332820/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-28. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

सौवीर - sauvīra n.: "aus Sauvīra stammend", Galenit (Bleiglanz)

Abb.: सौवीरम् । Lage von Sauvīra

[Bildquelle: JIJITH NR / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: सौवीरम् । Surmā-Auslage, Mumbai - मुंबई, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Meena Kadri. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/meanestindian/5231554628/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-29. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

कापोताञ्जन - kāpotāñjana n.: "Tauben-Salbe", als Kollyrium angewandter Stibnit (Antimonsulfid) oder Galenit (Bleiglanz)

Abb.: कपोताञ्जनम् । Chennamkary, Kerala

[Bildquelle: Paul H. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/babydinosaur/1918082173/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-28. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

यामुन - yāmuna n.: von der Yamunā kommend, Galenit (Bleiglanz)

Abb.: यामुनम् । Verlauf der Yamunā

[Bildquelle: Shannon / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLIcense]

Abb.: यामुनम् ।

[Bildquelle. Adib Roy. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/manunited/3765147158/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-29. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

| 101c./d. tutthāñjanaṃ śikhigrīvaṃ

vitunnaka-mayūrake तुत्थाञ्जनं शिखिग्रीवं वितुन्नक-मयूरके ।१०१ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Kupfersulfat (Chalkanthit):]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Blue vitriol."

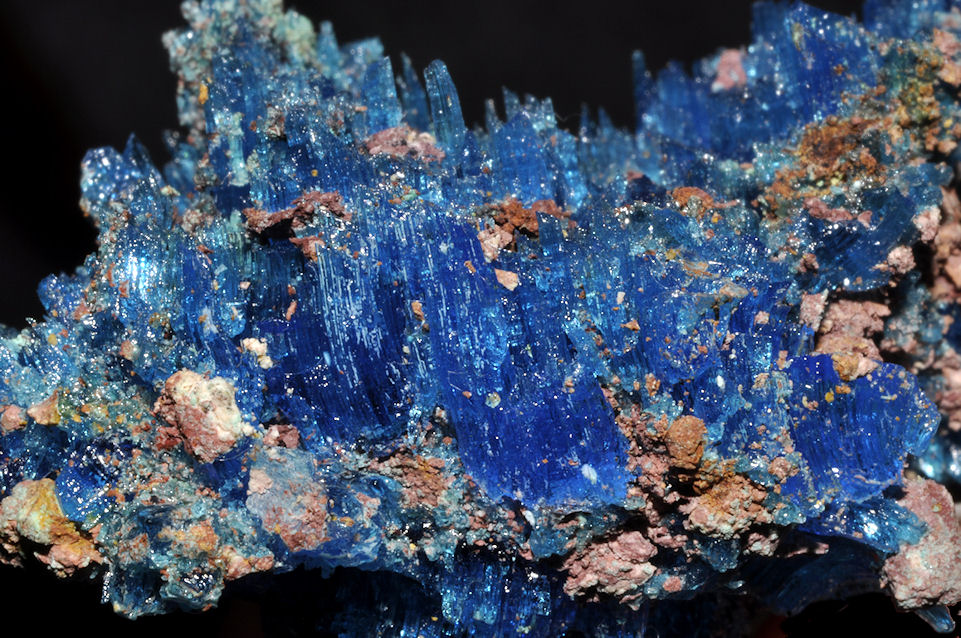

तुत्थाञ्जन - tutthañjana n.: Kupfersufat-Salbe

Abb.: तुत्थम् । Chalkanthit

[Bildquelle: Chmee2 / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

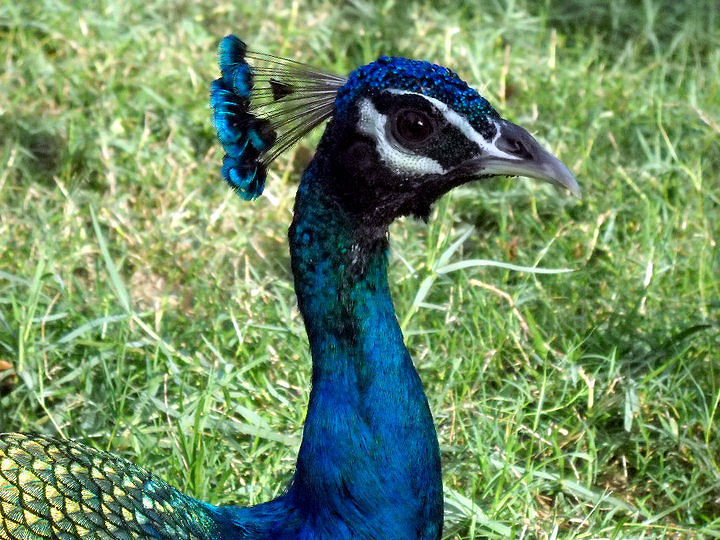

शिखिग्रीव - śikhigrīva n.: Pfauenhals(farbe), Chalkanthit

Abb.: शिखिग्रीवम् । Thiruvananthapuram -

തിരുവനന്തപുരം,, Kerala

[Bildquelle: Nithin1600 / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: शिखिग्रीवम् । Chalkanthit, Chile

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

वितुन्नक - vitunnaka n.: "Zerstochenes, Zerstechendes", Kupfersulfat, Chalkanthit

Abb.: वितुन्नकम् । Chalkanthit

[Bildquelle: Parent Géry / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

मयूरक - mayūraka n.: Pfauenfarbe, Kupfersulfat, Chalkanthit

Abb.: मयूरकम् । Chalkanthit, USA

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"Chalkanthit, in der Chemie auch als Kupfersulfat (veraltet Kupfervitriol) bekannt, ist ein eher selten vorkommendes Mineral aus der Mineralklasse der „Sulfate (und Verwandte)“ und dort Namensgeber der Chalkanthitgruppe. Es kristallisiert im triklinen Kristallsystem mit der chemischen Zusammensetzung Cu[SO4] · 5 H2O [1] und entwickelt meist krustige Überzüge oder faserige bzw. körnige Aggregate, selten auch kleine, prismatische bis tafelige Kristalle in hell- bis dunkelblauer Farbe. Sehr selten sind auch grüne bis grünblaue Kristalle zu finden." [Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kupfervitriol. -- Zugriff am 2011-09-21]

"Kupfervitriol (schwefelsaures Kupfer, Kupfersulfat, Kuprisulfat, blauer, cyprischer Vitriol, blauer Galitzenstein, Blaustein) CuSO4 findet sich in der Natur (Chalkanthit) als Zersetzungsprodukt von Kupfererzen, meist in stalaktitischen oder nierenförmigen Aggregaten, als Überzug und Beschlag, auch gelöst in Grubenwassern (Zementwassern), und wird erhalten, indem man Kupferoxyd (Kupferhammerschlag) in verdünnter Schwefelsäure oder metallisches Kupfer in heißer konzentrierter Schwefelsäure löst. Man erhält auch Kupfervitriol, wenn man Kupfer mit verdünnter Schwefelsäure bei Luftzutritt behandelt. [...] Man benutzt Kupfervitriol in der Färberei und Zeugdruckerei, zur Darstellung von Kupferfarben, als Fixiermittel für substantive Baumwollfarben (kupfern), in der Galvanoplastik, zum Konservieren des Holzes und der Tierbälge, zum Brünieren des Eisens, zum Färben des Goldes, zum Präparieren der Tonmasse im Deaconschen Chlorbereitungsprozess, zum Ausbringen des Silbers aus seinen Erzen, zum Beizen des Saatgetreides, in großer Menge und in mehrern Formen (Bordelaiser Brühe etc.) zum Bekämpfen von Pflanzenparasiten, als Brechmittel bei narkotischen Vergiftungen, bei Diphtherie, Phosphorvergiftung, Diabetes, auch äußerlich als Ätzmittel etc. Bei Einwirkung von Kupferoxyd, kohlensaurem Kupferoxyd, ätzenden oder kohlensauren Alkalien auf Kupfervitriol entstehen basische Salze, die sich zum Teil in der Natur in mehreren Mineralien finden, auch in der Farbentechnik benutzt werden. Basisch schwefelsaures Kupfer gibt mit Ammoniak eine tief dunkelblaue Lösung von basisch schwefelsaurem Kupferammoniak, die Baumwolle, Papier etc. zu einer schleimigen Flüssigkeit löst. Mit überschüssigem Ammoniak gibt Kupfervitriol eine tief lasurblaue Lösung, aus der nach vorsichtigem Übergießen mit Alkohol schwefelsaures Kupferoxydammoniak (Kupriammoniumsulfat, Kupfersalmiak) CuSO4+4NH3+H2O kristallisiert. Diese großen, tief dunkelblauen Kristalle riechen schwach ammoniakalisch, schmecken ekelhaft metallisch-ammoniakalisch, lösen sich in 1,5 Teil Wasser, verlieren an der Luft Wasser und Ammoniak und hinterlassen bei 150° die Verbindung CuSO4+2NH3 oder SO4-NH3-NH3-Cu. Man benutzt das Salz in der Feuerwerkerei und als Arzneimittel. Kupfervitriol war schon den Alchimisten bekannt, die oft von eisenhaltigem Kupfervitriol (Verbindung von Venus und Mars) ausgingen, um den Stein der Weisen zu finden. Van Helmont erhielt 1644 K. durch Erhitzen von Kupfer mit Schwefel an der Luft und Glauber 1648 aus Kupfer und Schwefelsäure."

[Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

"SULPHATE OF COPPER. Sans. तुत्थ, Tuttha. Vern. Tutia.

SULPHATE of copper was known in India from a very remote period. It is prepared by roasting copper pyrites, dissolving the roasted mass in water and evaporating the solution to obtain crystals of the sulphate. It was known as a salt of copper, for the Bhāvaprakāśa says it contains some copper and therefore possesses some of the properties of that metal. It is described in this work as astringent, emetic, caustic, and useful in eye diseases, skin diseases, poisoning etc. It is purified for internal use, by being rubbed with honey and ghee and exposed to heat in a crucible. It is then soaked for three days in whey, and dried. Sulphate of copper thus prepared is said not to produce vomiting when taken internally. Dose, one to two grains.

Sulphate of copper dissolved in hot water is administered in insensibility from poisoning to excite vomiting. It enters into the composition of some medicines for remittent fever, such as the Jvarāṅkuśa mentioned in Bhāvaprakāśa, but arsenic is the active ingredient in these preparations.

[...]

Sulphate of copper is applied to sinuses and fistula-in-ano with the object of stimulating and healing them. It is added to ointments for foul ulcers. A solution of sulphate of copper is poured into the eyes in opacity of the cornea."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 66ff.]

|

102a/b.. karparī

dārvikā kvāthodbhavaṃ tutthaṃ rasāñjanam कर्परी दार्विका क्वाथोद्भवं तुत्थं रसाञ्जनम् ।१०२ क। [Bezeichnung für eine bestimmte Art von Augenschnimke:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): Siehe zum Folgenden

| 102. karparī dārvikā kvāthodbhavaṃ

tutthaṃ rasāñjanam rasagarbhaṃ tārkṣyaśailaṃ gandhāśmani tu gandhikaḥ

कर्परी दार्विका क्वाथोद्भवं तुत्थं रसाञ्जनम् । Bezeichnungen für durch Abkochen gewonnene Augenschminke (tuttha n.: als Augenschminke benutztes Vitriol:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Collyrium.. Extracted from Ammomum Zanthorhizon, Roxb.[= Amomum xanthorhizon Roxb. ex Steud. = Zingiber montanum (J. König) Link ex A. Dietr. 1831 - Bengal-Ingwer - Bengal Ginger, Cassumunar Ginger] Some grammarians include karparī in the synonyma of the blue vitriol. Medical authors write it खर्परी or खर्परं, and make it a distinct sort of collyrium."

Colebrooke (1807) zu 120cb./c.: "Another sort. Some join this article with the preceding, omitting कर्परी from the synonyma ; this agrees with the medical books."

dārvī = Berberis aristata DC. 1821 - Begrannte Berberitze - Chitra.

Colebrookes Zingiber montanum (J. König) Link ex A. Dietr. 1831 stimmt wohl nicht.

दार्विका - dārvikā f.: aus Holz Entstandene (Abkochung von Berberis aristata DC. 1821 - Begrannte Berberitze - Chitra)

रसाञ्जन - rasāñjana n.: Saft-Schminke (Abkochung von Berberis aristata DC. 1821 - Begrannte Berberitze - Chitra)

रसगर्भ - rasagarbha n.: aus Saft Entstandenes (Abkochung von Berberis aristata DC. 1821 - Begrannte Berberitze - Chitra)

तार्क्ष्यशैल - tārkṣyaśaila n.: Tārkṣya-Fels (Abkochung von Berberis aristata DC. 1821 - Begrannte Berberitze - Chitra)

"रसाञ्जन Rasāñjana is the extract of the wood of Berberis Asiatica [= Berberis aristata DC. 1821] called rasot in the vernacular. It will be noticed in its place in the Vegetable Materia Medica." [Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 74.]

दार्वीक्वाथसमं क्षीऋअं पादं पक्वा यदा घनम् ।

तदा रसाञ्जनाख्यं तन्नेत्रयोः परमं हितम् ॥२०३॥"Decoction of dārvī [Berberis aristata] added with equal quantity of milk is boiled and reduced to one-fourth of the total quantity and allowed to cool. After it becomes thick jelly it is called as Rasāñjana (dārvīrasāñjana) and is highly beneficial to the eyes (when used as collyrium)."

[Quelle: Bhāvaprakāśa Bd. 1, S. 192]

dārvī = Berberis aristata DC. 1821 - Begrannte Berberitze - Chitra

Abb.: दार्वी । Berberis aristata DC. 1821 - Begrannte Berberitze -

Chitra

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine, v. 52 (1825), Tab. 2549]

Abb.: दार्वी । Berberis aristata DC. 1821 - Begrannte Berberitze -

Chitra, Shimla -

"Berberis tinctoria (Lesch.) Dyer's Berberry

Description.—Shrub, 6-10 feet; [...] flowers yellow; berries 2-3 seeded.

Fl. Jan.—ApriL

W. & A. Prod. i. 16.

Neilgherries. Pulney mountains.

Economic Uses.—This species of Berberry, found on the Neilgherries, serves, as the name implies, for dyeing a yellow colour. The roots contain 17 per cent of useful colouring matter. According to Leschenault, who had the wood analysed, it contained the yellow colouring principle in a greater state of purity than the common English Berberry. According to recent investigations, this, species is identical with the B. aristata.—(Dec.) It ranges on the mountains of India from the Himalaya to the Neilgherries, and to Newera Ellin, in Ceylon. It is a handsome and ornamental shrub, remarkable for its fine large compound racemes of flowers; the fruit is of an oblong shape and brownish-purple colour, with little or no bloom. It is very distinct from other species, and grows quickly. The root and wood are of a dark yellow colour, and form the yellow wood of Persian .authors. In Nepaul the fruit of this .species is dried like raisins.—Wight. Loudon, Journ. Agri. Hort. Soc., iii. 272."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"BERBERIS, ARISTATA, DC.

Fig.—Bentl. and Trim., t. 16.

Nepaul Barberry

Hab.—Temperate Himalaya, Nilgiri Mountains, Ceylon.

B. LYCIUM, Boyle.

Ophthalmic Barberry

Hab.—Western Himalaya from Garwhal to Hazara.

B. ASIATICA, - Roxb.

Fig.—Deless. Ic. Sel. ii. t. 1.

Hab .—Himalaya, Behar on Parasnath.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—Varions species of Barberry occur oh the Himalaya and Nilgiri mountains in India, at elevations between 6,000 and 10,000 feet. The wood (Daruharidra), extract (Rasanjana), and probably the fruit, have been used by the natives from a very early date. The Greeks were acquainted with the extract under the name of Indian Lycium as long ago as the first century; it would appear, though, that there were other kinds of Lycium in use at that time. (Confer. Pharmacographia, p. 84.*) The early Arabian writers were also acquainted with it by the name of Huziz-i-Hindi,+ and mention its Indian name, which some of them derive from Ras, juice, and Uth (uthna, to boil). Hakim Abd-el-Hamid describes its manufacture from the powdered wood by exhaustion with water, filtration, and admixture with an equal bulk of cow's milk, the mixture being finally evaporated to the consistence of an extract, and enveloped in leaves; this method of preparation is the same as that described in Sanskrit works.

* Dios. i. 117; Plin. 24, 76, 77; Cels. 5, 26 ; 6, 7; 8, 6 ; Scrib. Larg. Comp. 19, in the early stage of ophthalmia.

+ They describe two kinds, Maki or the λυκιον of the Greeks, and Hindi or Indian ; the former was derived from Rhamnus infectorius, the berries of which are used in dyeing leather yellow.

Royle, in 1833, brought Rusot more prominently to the notice of Europeans; since then it has been pretty extensively employed as a tonic and febrifuge. The root-bark of Barberry is now official in the Pharmacopoeia of India, it is noticed in the Tuhfat-el-inuminin under the name of Arghis, and is said to possess all the properties of Mamiran. Surgeon-General Cornish, of Madras, states that the Nilgiri Barberry bark (Mullu-kulla- puttai Tam.,) has been used in the treatment of ague with good results. A similar opinion appears to be generally held by medical men in India. In the bazaars the stern, extract and fruit are always obtainable; the two first are considered cold and dry, and are prescribed in combination with other bitters and aromatics, as tonics and antiperiodics, especially when bilious symptoms and diarrhoea are present; they are also used in menorrhagia. Rusot mixed with opium, alum, rock salt, chebulic myrobalans, and various other-drugs, is much used as an external application in inflammatory swellings, and is rubbed in round the orbit in painful affections of the conjunctiva; it is also used mixed with honey as an application to aphthae, and abrasions and ulcerations of the skin, and mixed with milk it is dropped into the eye in conjunctivitis. The fruit is cooling and acid. Berberine in doses of grain given subcutaneously kills rabbits, with symptoms of prostration and fall of temperature; but a dose eight times as great given to them by the mouth has no action, and 15 grains only produce in man slight colicky pains and diarrhoea. Is said to cause contraction of the intestines and of the spleen, and to lessen oxidation in the blood. (Lauder Brunton.) The drugs which contain this alkaloid are very useful in malarial dyspepsia accompanied by a febrile condition."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 64ff.]

Zingiber montanum (J. König) Link ex A. Dietr. 1831 - Bengal-Ingwer - Bengal Ginger, Cassumunar Ginger

Abb.: Zingiber montanum (J. König) Link ex A. Dietr. 1831 -

Bengal-Ingwer - Bengal Ginger, Cassumunar Ginger

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas, 1880 / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

| 102c./d. rasagarbhaṃ tārkṣyaśailaṃ

gandhāśmani tu gandhikaḥ 103a./b. saugandhikaś ca cakṣuṣyā-kulālyau tu kulatthikā

रसगर्भं तार्क्ष्यशैलं

गन्धाश्मनि तु गन्धिकः ।१०२ ख। Bezeichnungen für Schwefel (गन्धाश्मन् - gandhāśman m.: "Geruchstein", Schwefel):

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Sulphur."

गन्धाश्मन् - gandhāśman m.: "Geruchstein", Schwefel

Abb.: गन्धाश्मा । Schwefel (S)

[Bildquelle: Ben Mills / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

गन्धिक - gandhika m.: "Riechender", Schwefel

Abb.: गन्धिकः । Schwefel, Pakistan

[Bildquelle: Scott Christian. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/askwhat/286907982/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-30. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

सौगन्धिक - saugandhika m.: Wohlriechender, Schwefel

Abb.: सौगन्धिकः । Schwefelbad, Dehradun - देहरादून, Uttarkhand

[Bildquelle: Deep Goswami. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/deepgoswami/3678942708/. -- Zugriff am

2011-09-30. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung]

"SULPHUR, Brimstone.

[...]

Sulphur, from Sal, salt, and πυρ, fire, was employed in medicine by the Greeks, Arabs, and Hindus. Native or virgin sulphur uncombined, is either a volcanic product, or occurs in beds in many parts of the world ; found in combination with metals, as in the ores called pyrites, the sulphurets of iron, copper, lead, mercury, etc., whence it is obtained by roasting. Distilling it from earthen pots arranged in two rows on a large furnace, the sulphur fuses and sublimes, and passes through a lateral tube in each pot into another place on the outside of the furnace, which is perforated near the bottom, to allow the melted sulphur to flow into a pail containing water, where it congeals and forms rough or crude sulphur. This being re-distilled, forms refined sulphur. When fused and cast into moulds, it forms stick or roll sulphur.

The great repositories of sulphur are either beds of gypsum and the associated rocks, or the regions of active or extinct volcanoes. [...]

Most of the sulphur brought to Hindustan contains a considerable portion of orpiment,

being much less pure than either that which is dug out of the solfatara near Naples, or that imported from Sicily.

Sulphur and saltpetre are found in the mountains behind Teheran ; also in Kishni and in a hilly tract near Khamir, a town on the Persian continent, about 25 miles N.E. from Luft. It is met with in the district of Balkh ; also, according to Morier, at Balianlia in Persia. In Baluchistan it is got from the Suni mine, on the ridges separating Saharawan from Cutch Gandava ; the great mart for its sale is Bagh in Cutch Gandava; also in mountains south of Kalat, in the province of Mekran.

Sulphur, somewhat mixed with impurities, occurs in the Murree Hills, and the Sulaiman Hills near Dehm Ismail Khan, at Kalabagh. It is found extensively throughout the Salt Range. The valley of Puga in Ladakh, from whence borax is obtained, yields also sulphur. The Puga sulphur mine is situated a short distance from the Rulangchu, a small stream which is full of hot springs, and runs into the Indus at the foot of a gypsum cliff. Besides the numerous springs charged with sulphuretted hydrogen, and which deposit sulphur on the rock over which they pass, and on the grass and weeds by their sides, sulphur in a mineral form occurs near the surface of the nummulite limestone at Jabba, a little above the petroleum springs, in a white porous gypsum. Sulphur also occurs near Panobar, four miles from Shadipur, on the Indus. The crystals picked out of the rock are called Aunlisar.

In Udaipur it is to be met with, but of a quality inferior to that which is brought from the gulfs of Cutch and Persia. It is found in small quantities in Salem, Masulipatam, Guntur, Cuddapah, and Trichinopoly, along with gypsum in marl and clay beds, and in form of metallic sulphurets.

In the Wodiapolliam jungle, south of Wolandurpet, in the N. Arcot district, and which extends E. and W. across the Peninsula, a sulphurous earth is said to be found, covering an extent of low swampy ground, and the sulphur effloresces on the friable brown earth after rains, in yellow crystals."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 3. -- 1885. -- S. 758f.]

"SULPHUR.

Sans. गन्धक Gandhaka.

Four varieties of sulphur are mentioned by Sanskrit writers, namely, red, yellow, white and black. Of these the red and black are not now available. The yellow variety or vitreous sulphur is called āmlā-sār, because its semi-transparent crystals resemble the translucent ripe fruits of the āmalaki (Phyllanthus emblica). It is preferred for internal use in combination with mercury. The white variety or ordinary roll sulphur is inferior to the yellow, and used for external application in skin diseases.

Sulphur is purified by being washed in milk. It is first dissolved in an iron ladle smeared with butter and then gradually poured into a basin of milk. When cool and solidified it is fit for use. Dose twelve to twenty-four grains with milk or other vehicle. Sulphur is described as of bitter, astringent taste, with a peculiar strong smell. It increases bile, acts as a laxative and alterative, and is useful in skin diseases, rheumatism, consumption, enlarged spleen etc. In combination with mercury it is used in almost all diseases. The circumstance of its readily combining with and fixing metalic mercury, has led to its extensive use in combination with that metal.

In skin diseases sulphur is used both internally and externally. Internally it is given with milk or in the shape of a sulphurated butter, prepared from milk boiled with the addition of sulphur. The butter thus obtained is called Gandha taila, and is taken internally, and applied externally, in skin diseases. Sulphur and yavakṣāra (an impure carbonate of potash), mixed with mustard oil, is applied in pityriasis psoriasis etc. Sulphur enters into the composition of a large number of applications for skin diseases, the following is an example.

Ādityapāka taila. Take of sesamum oil four seers, madder, the three myrobalans, lac, turmeric, orpiment, realgar and sulphur equal parts, in all one seer. Mix and expose to the sun. This oil is useful in eczema, scabies etc.

In rheumatism it is used in combination with bdellium, as in the following, called Siṃhanāda guggulu. Take of sulphur eight tolas, bdellium eight tolas, decoction of the three myrobalans seventy-two tolas, castor oil thirty-two tolas, mix and boil together in an iron vessel till reduced to the consistence of a confection. Dose about one drachm twice daily. It is useful in chronic rheumatism, lameness, cough, asthma, and skin diseases."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 26f..]

| 103a./b. saugandhikaś ca

cakṣuṣyā-kulālyau tu kulatthikā सौगन्धिकश् च चक्षुष्या-कुलाल्यौ तु कुलत्थिका ।१०३ क। [Bezeichnungen für einen bestimmten als Augenschminke benutzten blauen Stein:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A blue stone used as a collyrium. Some make these three terms synonymous with the following."

Von mir nicht identifizierbar.

| 103c./d. rītipuṣpaṃ puṣpaketu

pauṣpakaṃ kusumāñjanam रीतिपुष्पं पुष्पकेतु पौष्पकं कुसुमाञ्जनम् ।१०३ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Messingoxid (?):]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Calx of brass."

Wohl eine Ausblühung an der Oberfläche von Messing.

"पुष्पाञ्जन Puṣpāñjana is described as an alkaline substance. I have not met with any vernacular translation of this word, nor with any person who could identify or supply the drug. Wilson, in his Sanskrit-English Dictionary, translates the term as calx of brass, but I know not on what authority." [Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 74.]

| 104a./b. piñjaraṃ pītakaṃ tālam

ālaṃ ca haritālake पिञ्जरं पीतकं तालम् आलं च हरितालके ।१०४ क। Bezeichnungen für Auripigment (हरितालक - haritālaka n.: Auripigment <zu harita 3: gelb>):

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Yellow orpiment."

हरितालक - haritālaka n.: Auripigment (zu harita 3: gelb)

Abb.: हरितालकम् । Auripigment (gelb) mit einem Restanteil Realgar (rot)

[Bildquelle: Ra'ike / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

पिञ्जर - piñjara n.: Goldfarbenes, Auripigment

Abb.: पिञ्जरम् । Auripigment, China

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

पीतक - pītaka n.: Gelbes, Auripigment

Abb.: पीतकम् । Auripigment, Georgien

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

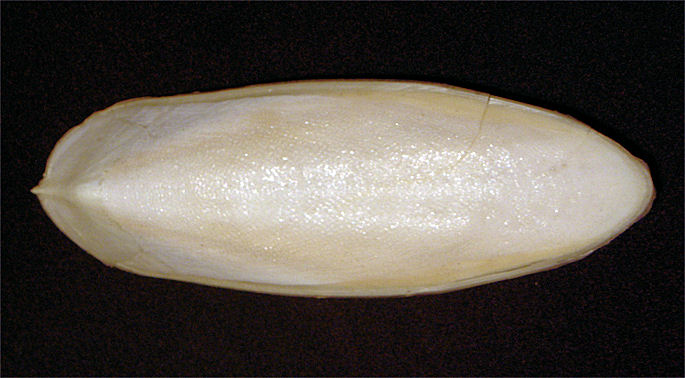

ताल - tāla n.: Frucht der Palmyrapalme

(Borassus flabellifer L. 1753), Auripigment

Abb.: तलानि । Früchte der Palmyrapalme

Abb.: तालम् । Auripigment, USA

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

आल - āla n.: Auripigment

Abb.: आलम् । Auripigment, USA

[Bildquelle: Rob Lavinsky, iRocks.com / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"Auripigment, As4S6, auch unter der im englischen Sprachraum verbreiteten Bezeichnung Orpiment, den veralteten Namen Arsenblende oder Rauschgelb, seltener unter seiner chemischen Bezeichnung Arsen(III)-sulfid bekannt, ist ein häufig vorkommendes Arsen-Schwefel-Mineral aus der Mineralklasse der nichtmetallartigen Sulfide." [Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auripigment. -- Zugriff am 2011-09-30]

"ORPIMENT. Sans. हरिताल, Haritāla.

ORPIMENT occurs in two forms, namely, in smooth shining gold-coloured scales called Vaṃsapatri haritāla, and in yellow opaque masses called Piṇḍa haritāla. Vaṃsapatri haritāla is preferred for internal use as an alterative and febrifuge. Piṇḍa haritāla is chiefly used as a colouring ingredient in paints, and for sizing country paper. Most of the older Sanskrit MSS. are written on paper prepared with haritāla, to preserve them from the ravages of insects, and this it does most effectually.*

* Babu Rajendralala Mitra gives the following interesting account of arsenicised paper in his report on Sanskrit manuscripts, published in the Proceedings of the Asiatic Society, for March 1875. " The manuscripts examined have mostly been written on country paper sized with yellow arsenic and an emulsion of tamarind seeds, and then polished by rubing with a conch-shell. A few are on white Kasmiri paper, and some on Palm-leaf. White arsenic is rarely used for the size, but I have seen a few codices sized with it, the mucilage employed in such cases being acacia gum. The surface of ordinary country paper being rough, a thick coating of size is necessary for easy writing ; and the tamarind-seed emulsion affords this admirably. The paper used for ordinary writing is sized with rice gruel ; but such paper attracts damp and vermin of all kinds, and that great pest of literature, the silver-fish thrives luxuriantly on it. The object of the arsenic is to keep off this insect, and it serves the purpose most effectually. No insect or worm of any kind will attack arsenicised paper, and so far the MSS. are perfectly secure against its ravages. The superior appearance and cheapness of European paper has of late induced many persons to use it instead of the country arsenicised paper in writing puthis ; but this is a great mistake, as the latter is not near so durable as the former, and is liable to be rapidly destroyed by insects. I cannot better illustrate this than by referring to some of the MSS. in the Library of the Asiatic Society. There are among them several volumes written on foolscap paper, which dates from 1820 to 1830, and they already look decayed, mouldering, and touched in several places by silver-fish. Others on John-letter paper which is thicker, larger and stouter, are already so far injured that the ink has quite faded, and become in many places illegible, whereas the MSS. which were originally copied on arsenicated paper for the College of Fort William in the first decade of this century, are now quite as fresh as they were when first written, I have seen many MSS. in private collections which are much older, and still quite as fresh. This fact would suggest the propriety of Government records in Mofussil Courts being written on arsenicised paper instead of the ordinary English foolscap, which is so rapidly destroyed both by the climate and also by white-ants. To guard against mistake I should add here that the ordinary yellow paper sold in the bazars is dyed with turmeric, and not at all proof against the attack of insects,"

Haritāla is purified for internal use by being successively boiled in kāñjika, the juice of the fruit of Benincasa cerifera (kuṣmāṇḍa) , sesamum oil, and a decoction of the three myrobalans, for three hours in each fluid. Some physicians, probably to save time, mix all these fluids together, and boil the orpiment in the mixture for three hours only. The dose of orpiment thus purified is from two to four grains.

Several methods of roasting orpiment are described. The Bhāvaprakāśa recommends that orpiment should be powdered and made into a ball with the juice of Boerhaavia diffusa (punarṇavā) and placed in the centre of a pot full of the ashes of that plant. The pot should be now covered with a dish, luted with clay, and heated over a fire for twenty hours. When cool the ball of roasted orpiment is taken out from the pot and reduced to powder. Another process is as follows. Take of purified orpiment and yavakṣāra, equal parts, rub them together with the juice of Vitex Negundo (nirgundi), and roast the mixture in a closed crucible. The resulting compound from both these processes is described as a white camphor-like substance.

A specimen of roasted orpiment supplied to me by an upcountry physician was analyzed and found to contain but a small proportion of white arsenic. Bengali physicians do not prepare this drug from a superstitious notion that the man who roasts orpiment dies very soon. They purchase it from Fakirs or religious mendicants. It is said that some specimens of roasted orpiment are highly poisonous, and contain a large proportion of white arsenic. The quality of the drug would no doubt vary according to the method in which it is prepared.

Orpiment is said to cure fevers and skin diseases, to increase strength and beauty, and to prolong life. In fever it is used in combination with mercury, aconite, etc.

[...]

The use of orpiment as a depilatory was known to the ancient Hindus. It enters into the composition of numerous formulae for the removal of hair."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 41ff.]

| 104c./d. gaireyam arthyaṃ girijam

aśmajaṃ ca śilājatu गैरेयम् अर्थ्यं गिरिजम् अश्मजं च शिलाजतु ।१०४ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Asphalt (oder Ocker):]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Red chalk. According to a different explanation, bitumen."

"Asphalt (griech., Erdpech), Mineral, schwarz bis schwarzbraun, fettglänzend, undurchsichtig, Härte 2, spez. Gew. 1,1–1,2, riecht, zumal gerieben, stark bituminös, ist brennbar, schmilzt bei 100°, löst sich in Terpentin, Petroleum und Benzin. Es findet sich derb, eingesprengt, in Hohlräumen verschiedenartiger Gesteine, auch als Kluftausfüllung und auf Erzgängen, als Imprägnation von Sandsteinen und Kalksteinen, selten lagerartig, wie bei Avlona in Albanien." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

"Ocker (Ocher), natürlich vorkommendes Gemenge von erdigem Eisenhydroxyd mit Ton und Kalk, bald heller, bald dunkler bräunlich. Ocker findet sich am Harz, in Bayern, im Siegenschen, in England, Frankreich und Italien. Er dient als Farbstoff, indem man ihn durch Abschlämmen von beigemengtem Sand reinigt, trocknet, mahlt und siebt. Gewöhnliche Sorten heißen Gelberde. Durch vorsichtiges Erhitzen wird ihre Farbe feuriger, und man unterscheidet dann je nach der Nuance: Schöngelb, Kasselergoldgelb, Chinesergelb, Gelbocker, Lichtocker, Satinocker, Amberger Erde und Dunkelocker. Bei starkem Erhitzen hinterlässt Ocker rotes Eisenoxyd. Der gebrannte Ocker heißt auch Berlinerrot, Preußischrot, Nürnbergerrot, Hausrot, Braunrot Roter Ocker findet sich bei Saalfeld, am Harz, in Böhmen; die beste Sorte ist die Sienaerde. Ocker wird als Wasser-, Öl- und Kalkfarbe benutzt; er ist sehr dauerhaft und deckt ziemlich gut. Als Staubfarbe dient er zum Färben des sämischgaren Leders. " [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

गैरेय - gaireya n.: vom Berg Stammendes, roter Ocker, PW: "Bergpech, Erdharz"

Abb.: गैरेयम् । Natürlicher Asphalt

[Bildquelle: Piotr Gut / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"RED OCHRE. Sans. गैरिक Gairika. Vern. Gerumati.

Two sorts of gairika or ochre are mentioned by Sanskrit writers, namely, red and yellow. The red variety, called also Raktapāṣāṇa is used in medicine. It is a silicate of alumina coloured with oxide of iron It is purified by being soaked in milk seven times, and is described as sweetish, astringent, cooling, and useful in ulcers, burns, boils etc. It is rarely used internally except as an ingredient of some of the complex prescriptions containing a large number of mineral drugs, such as the preparation called Jvarakuñjara pārindra rasa, which contains nearly all the mineral substances."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 96.]

Abb.: गैरेयानि । Verschiedene Ocker

[Bildquelle: Oguenther / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

अर्थ्य - arthya n.: geeignet, reich, roter Ocker, PW: "Erdharz"

Abb.: अर्थ्यम् । Asphaltquelle, USA

[Bildquelle: Lldenke / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

गिरिज - girija n.: vom Berg Stammendes, roter Ocker, PW: "rote Kreide oder Erdharz"

Abb.: गिरिजम् । Mohenjo-daro (موئن جو

دڙو), Pakistan, ca. 2600 v. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Benny Lin. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/benny_lin/4557592878/. -- Zugriff am

2011-10-01. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

अश्मज - aśmaja n.: aus Stein entstanden, roter Ocker PW: "Erdharz, Eisen"

Abb.: अश्मजम् । Natürlicher Asphalt, Totes Meer, Israel

[Bildquelle: Daniel Zvi / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

शिलाजतु - śilājatu n.: Steinlack, Steingummi, Bitumen, Asphalt, PW: "Erdharz"

Abb.: शिलाजतु । Das Pechtropfenexperiment : Langzeitversuch zur Beobachtung

des Tropfverhaltens von Bitumen, eines bei Zimmertemperatur superzähen

Stoffes, der augenscheinlich ein Feststoff ist.

[Bildquelle: John Mainstone / University of Queensland / Wikipedia. -- GNU

FDLicense]

"ŚILĀJATU.

Śilājatu literally means stone and lac. The term is applied to certain bituminous substances said to exude from rocks during the hot weather. It is said to be produced in the Vindhya and other mountains where iron abounds. It is a dark sticky unctuous substance resembling bdellium in appearance. It has a bitter taste and a strong smell resembling stale cow's urine. Over platinum foil it burns with a little inflammable smoke and leaves a large quantity of ashes consisting chiefly of lime, magnesia, silica, and iron in a mixed state of proto and peroxide.*

* The silajit or alum earth of Nepal is a different article from the Śilājatu of the Sanskrit Materia Medica. The former is an article of Yunani not Hindu Medicine.

Śilājatu is prepared for medicinal use by being washed with cold water and then rubbed into an emulsion with its bulk of hot water or milk in an iron pot. This emulsion is exposed to the sun, when a black cream-like substance collects on its surface and; this is removed. The process is continued as long as any cream rises. If the mixture becomes too thick, hot water is added from time to time as required, but too much water should not be added at once, for then the cream will not rise to the surface. The Śilājatu thus collected is dried in the sun and preserved for use. The dregs at the bottom are thrown away. The extract of Śilājatu thus obtained is purified by being soaked in a decoction of the following plants, namely. Shorea robusta, (sāla), Buchanania latifolia (piāla), Terminalia tomentosa (asana) and Acacia catechu (khadira). Śilājatu is regarded as a powerful alterative tonic and is considered specially useful in urinary diseases, diabetes, gravel, anaemia, consumption, cough, and skin diseases. The extract of Śilājatu is given in doses of six to twelve grains. In strangury or painful micturition it is given with honey or with the decoction of Tribulus terrestris (gokshura). In urinary complaints it is given in combination with preparations of lead or tin. As an alterative tonic, it is used in combination with iron."

[Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 95.]

| 105a./b.

vola-gandharasa-prāṇa-piṇḍa-goparasāḥ samāḥ वोल-गन्धरस-प्राण-पिण्ड-गोपरसाः समाः ।१०५ क। [Bezeichnungen für Myrrhe (Harz von Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl. 1833 - Echte Myrrhe - Myrrh):]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "myrrh."

"Myrrhe (Myrrhenharz), Gummiharz, das aus Arabien und von der Somalküste meist über Aden und Bombay in den Handel kommt. Die afrikanische Myrrhe stammt von Commiphora abyssinica, die arabische Fadhilimyrrhe von andern Commiphora-Arten, sie fließt aus der Rinde aus und bildet nach dem Erstarren unregelmäßige Körner oder größere Massen, ist gelblich bis braun, spröde, durchscheinend, riecht eigentümlich balsamisch, schmeckt gewürzhaft bitter, gibt mit Wasser eine Emulsion, löst sich auch in Alkohol unvollständig, bläht sich beim Erhitzen auf, ohne zu schmelzen, und verbreitet dabei einen angenehmen Geruch. Sie besteht aus Gummi, Harz, ätherischem Öl etc. Das Öl ist farblos, riecht nach M., schmeckt mild, dann balsamisch kampferartig, spez. Gew. 1,019 und besteht hauptsächlich aus einem Körper C10H14O. M. dient als tonisch balsamisches Mittel bei zu starken Absonderungen der Atmungs- und Urogenitalorgane, bei Verdauungsstörungen, Magenkatarrh, äußerlich als Myrrhentinktur (aus 1 Teil M. und 5 Teilen Alkohol bereitet) zum Verbinden schlecht eiternder Geschwüre und zu adstringierenden Mundwässern. Das Myrrhenöl dient zu Mundwässern und Zahnmitteln. M. bildete seit den ältesten Zeiten neben Weihrauch einen Bestandteil von Räucherungsmitteln und Salben und wurde von den Ägyptern auch beim Einbalsamieren benutzt. Besonders zu gottesdienstlichen Zwecken blieb die M. fortwährend auch bei den Griechen im Gebrauch, und als »Smyrna« findet sie sich auf der Liste der römischen Zollstätte in Alexandria. Die römische Kirche aber bevorzugte bei weitem den Weihrauch." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl. 1833 - Echte Myrrhe - Myrrh

Abb.: Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl. 1833 - Echte Myrrhe - Myrrh

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883-1914]

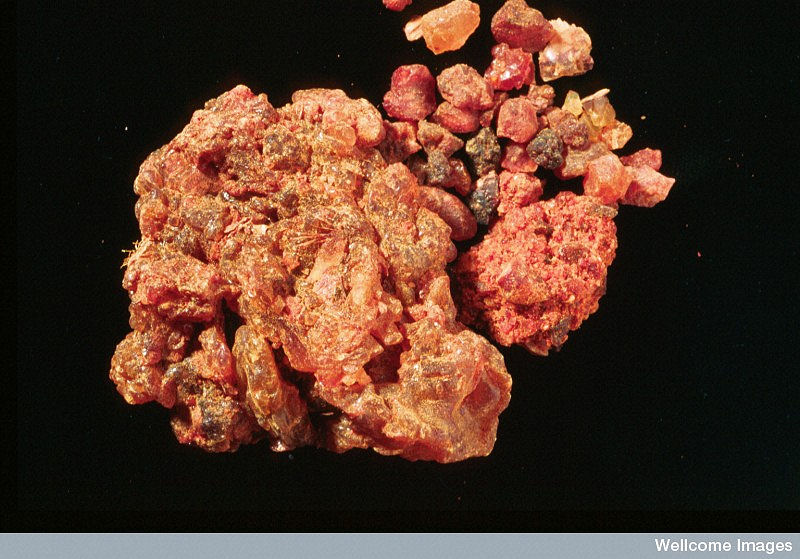

वोल - vola m.: Myrrhe

Abb.: वोलः । Myrrhe aus der Dhofar-Region - ظفار,

Oman

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

गन्धरस - gandharasa m.: "Geruchssaft", Myrrhe

Abb.: गन्धरसाः ।

[Bildquelle: Sjschen / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Some commonly used raw incense and incense-making materials (from top down, left to right)

- Makko powder (抹香; Machilus thunbergii),

- Borneol camphor (Dryobalanops aromatica),

- Sumatra Benzoin (Styrax benzoin),

- Omani frankincense (Boswellia sacra),

- Guggul (Commiphora wightii),

- Golden Frankincense (Boswellia papyrifera),

- the new world Tolu balsam (Myroxylon toluifera) from South America,

- Somali myrrh (Commiphora myrrha),

- Labdanum (Cistus villosus),

- Opoponax (Commiphora opoponax), and

- white Indian sandalwood powder (Santalum album)"

प्राण - prāṇa m.: Odem, Myrrhe

Abb.: प्राणः । Myrrhe (Commiphora myrrha)

[Bildquelle:

पिण्ड - piṇḍa m.: Klumpen

Abb.: पिण्डाः । Myrrhe

[Bildquelle: Birgit Lachner / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

गोपरस - goparasa m.: "Kuhhirtensaft, Kṛṣṇa-Saft", Myrrhe

Dem neugeborenen Kṛṣṇa wurde u.a. Myrrhe dargebracht (wie dem Jesuskind)

Abb.: गोपरसः । Baby Kṛṣṇa

[Bildquelle: Nwchar / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"MYRRH is called Vola in Sanskrit and is described as an article to be had in the beniah's shop, thereby implying it to be an imported drug. It is said to be useful in fever, epilepsy and uterine affections, but is not much used in practice." [Quelle: Dutt, Uday Chand: The materia medica of the Hindus / Uday Chand Dutt. With a glossary of Indian plants by George King. -- 2. ed. with additions and alterations / by Binod Lall Sen & Ashutosh Sen. -- Calcutta, 1900. - XVIII, 356 S. -- S. 136.]

"BALSAMODENDRON, Sp. var. Fig.—Bentl. and Trim., t. 60.

Hab.—Africa, Socotra, Arabia. Myrrh.

[...]