|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 15. vaiśyavargaḥ (Über Vaiśyas). -- 14. Vers 106c - 112b: Handel V: Handelsgüter III. -- Fassung vom 2011-10-06. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa7/amara215n.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-10-06

Überarbeitungen:

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener,

gut ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener,

gut ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

| 106c./d. raṅga-vaṅge

atha picus tūlo 'tha kamalottaram रङ्ग-वङ्गे अथ पिचुस् तूलो ऽथ कमलोत्तरम् ।१०६ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Baumwolle:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Cotton."

पिचु - picu m.: Baumwolle (von Gossypium herbaceum L. 1753 oder Gossypium arboreum L. 1753)

Abb.: पिचुः । Gossypium herbaceum L. 1753 - Gewöhnliche

Baumwolle

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

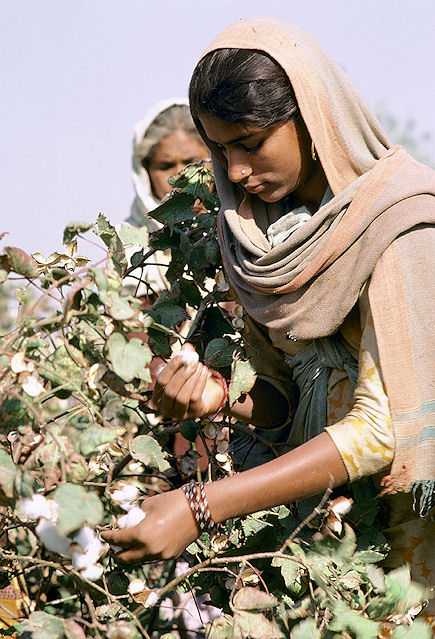

Abb.: पिचुः । Baumwollpflückerin, Indien

[Bildquelle: Ray Witlin / World Bank. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/worldbank/2183935466/. -- Zugriff am

2011-10-03. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

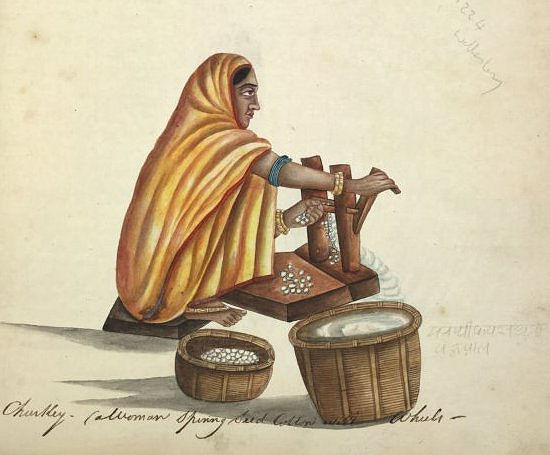

Abb.: पिचुः । Trennung der Baumwollfaser vom Samen, 1815/20

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: पिचुः । Gandhi beim Baumwoll-Spinnen, 192x

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: पिचुः । Webstuhl, Gopalpur, Rajshahi - রাজশাহী, Bangladesh

[Bildquelle: Anduze traveller. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/anduze-traveller/2317487305/. -- Zugriff am

2011-10-03. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

तूल - tūla m.: Flaum, Baumwolle (von Gossypium herbaceum L. 1753 oder Gossypium arboreum L. 1753)

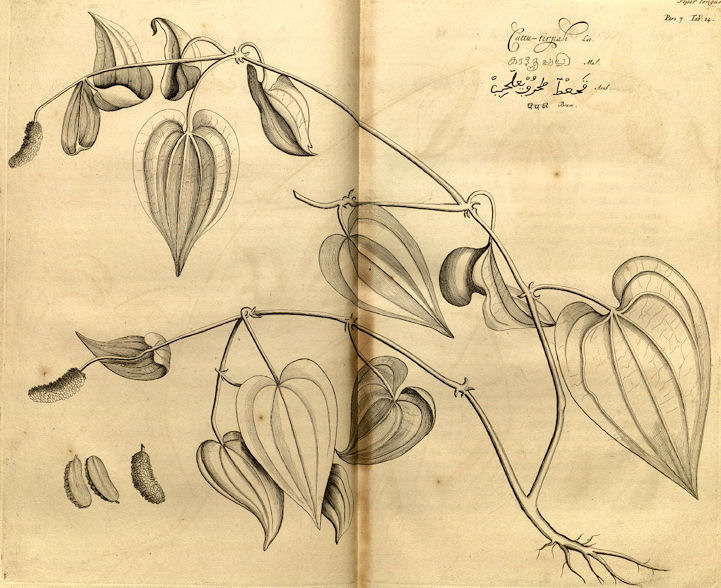

Abb.: तूलः । Gossypium herbaceum L. 1753 - Gewöhnliche

Baumwolle

[Bildquelle: Roxburgh. -- Vol III. -- 1819. -- Tab. 269. -- Image courtesy

Missouri Botanical Garden.

http://www.botanicus.org. --

Creative Commons Lizenz

(Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: तूलः । Zubereitung von Baumwolle für Matratzen, Nagaon -

নগাঁও, Assam

[Bildquelle: Michael Foley. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/michaelfoleyphotography/5554982936/. --

Zugriff am 2011-10-03. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keien Bearbeitung)]

"Cotton consists of the delicate, tubular, hair-like cells which clothe the seeds of species of gossypium. Its commercial value depends on the length and tenacity of these tubular hairs, which, in drying, become flattened, and are transparent, without joints, and twisted like a corkscrew. Under water, they appear like distinct, flat, narrow ribbons, with occasionally a transverse line, which indicates the end of cells.

In America, two distinct varieties are indigenous,— Gossypium Barbadense, yielding the cotton from the United States, and Gossypium Peruvianum or acuminatum, that which is produced in South America.

India also has two distinct species, —Gossypium herbaceum, or the common cotton of India, which has spread to the south of Europe, and Gossypium arboreum, or tree cotton, which yields none of the cotton of commerce.

Cotton plants have been characteristic of India from the earliest times ; and at the present day the majority of its people are clothed with fabrics made from cotton, which is woven to a large extent in India, but more largely in Europe and America.

[...]

The plant has always been grown in almost every district of India, for local use or export, in soils suitable and unsuitable to its growth ; and at the London Exhibition of 1862, the values of 138 samples exhibited ranged from sixpence to three shillings the pound.

Mr. Shaw says (p. 186, Cotton Export) cotton cultivation in India would not be a profitable speculation for Europeans ; the natives can grow it much cheaper. Our function is simply that of buyer. We have no local market for the American cotton. It does not answer for native spinning so well as their own.

The use of cotton dates from a very early period. Sanskrit records carry it back at least 2600 years, while in Peruvian sepulchres cotton cloth and seeds have been found. It is noticed in the book of Esther, i. 6, where its Sanskrit name Karpas is translated 'greens' in the English Bible. Herodotus and Ctesias notice it ; but it was not till the invasion of India by Alexander that the

Greeks were acquainted with the plant, as may be seen in Theophrastus, and also in Pliny. Pliny, writing about 500 years subsequent to the time of Herodotus, mentions (lib. 19, c. 1) that the upper part of Egypt, verging towards Arabia, produces a small shrub which some call gossypion, others xylon, and from the latter the cloth made from it, xylina, bearing a fruit like a nut, from the interior of which a kind of wool is produced, from which cloths are manufactured inferior to none for whiteness and softness, and therefore much prized by the Egyptian priesthood.

[...]

The Gossypium arboreum, or tree-cotton of India, and peculiar to India alone, is unfitted for manufacturing purposes, and is unknown to commerce, though yielding a beautifully soft and silky fibre, admirably adapted for padding cushions, pillows, etc.

In commerce, Indian cotton has usually been known under the names of the locality of its growth or place of shipment. The staple of these sorts appears to range from 0.85 to 1.1 of an inch in length ; the staple of the celebrated Sea Island cotton being usually 1.5 in length.

The three qualities by which the value of cottons are determined are, length of staple, strength of fibre, and cleanness of sample. Colour, which at one time was thought much of, is no longer looked upon as a matter of moment.

[...]

The cotton of India is allowed to be inferior as regards its staple and purity, but in durability it at least equals the produce of any part of America, and of this fact the Hindus are themselves perfectly aware. Dr. Royle gives 3 distinct varieties of cotton, all indigenous to Hindustan.

The common description is found scattered more or less throughout India, reared as a triennial or annual. It reaches the height of 5 or 6 feet in warm, moist climates. The seeds are five in number, clothed with a short greyish down. In the Peninsula there are two distinct varieties of this sort, known amongst the natives as Oopum and Nadum, The first thrives only on the richest black soil, and is an annual, producing a fine staple ; the latter is a triennial plant, and grows on the poorer rod soil, yielding small crops of inferior quality.

Second.—Dacca cotton is a distinct variety of the Gossypium Indicum. It differs from the previous variety in the plant being more erect, with fewer branches, and tinged with a reddish hue, whilst the cotton is finer, softer, and longer. This variety is reared more or less extensively throughout Bengal, especially in the Dacca district, where it is employed in the manufacture of the exquisitely fine muslin cloths known over a great part of the world as Dacca muslins, and whose delicacy of texture so long defied the imitation of the art-manufacturers of the West.

A third variety is the cotton grown in Berar, in the northern provinces of the Madras Presidency, and in Surat and Broach. This plant attains a greater size than the preceding, bears for a longer period, and produces a fibre of a finer quality than the former. It appears to thrive best on a light black soil.

Soil.—The soil in which all these Indian varieties thrive may be classed under two distinct heads, the black cotton soil and the red soil. The former of these, as its name indicates, is of a black or deep brown colour, absorbs and retains much rain, forming in the rains a heavy tenacious mass, and drying into solid lumps in the hot months. An analysis of this gives 74 per cent, of silex, 12 of carbonate of lime, 7¼ protoxide of iron, 3 of alumina, 2 of vegetable matter, and 1/3 salts, with a trace of magnesia. The red soil of India has been found in some localities better suited to the growth of cotton than the black earth. It is a rather coarse yellowish red soil, commingled with particles of the granitic rocks,—silex, felspar, and aluminous earth. It mainly differs in composition from the preceding in the iron existing in the state of peroxide or red oxide, whilst the carbonate of lime is found present in greater abundance.

[...]

Cotton-wool bears value according to its colour, length, strength, and fineness of fibre. Pure whiteness is generally held to denote a secondary quality ; whilst a yellowish tinge, provided it be not the result of casual exposure to damp, or the natural effect of an unfavourable season, is indicative of superior fineness. Many varieties of raw cotton are seen in commerce, each sort being distinguished by the name of the locality where it is produced. American, Bourbon, Egyptian, Amraoti, Dacca, Oopum, Nadura, Orleans, Sea Island, etc. etc. ; but the main distinction recognised is that between the long and short stapled qualities ; though of these, again, there are different degrees of excellence. The 'Sea Island' cotton of Georgia (so named from being raised on certain narrow sandy islets lying along the coast of that province) is esteemed the best of the long-stapled kind ; and the upland produce of the same state excels amongst the short-stapled classes. The indigenous Asiatic cotton is exclusively of the latter class.

The indigenous plant of India is an annual, and succeeds best in the rich black soil that characterizes various districts. The American plant, though in reality perennial, is practically an annual in India ; for in India neither native nor foreign cotton is cultivated on the same ground more than one year in three, it« properties being found to exhaust the productive powers of the soil. American cotton grows well on the black soil of India, but thrives still better on the light red lands.

Each of these species possesses advantages peculiar to itself. The Indian variety is capable of being manufactured into fabrics of extraordinary durability and wonderful fineness ; its colour, too, is superior, but the staple short.

[...]

The ordinary native cotton-cleaning machine, for freeing the cotton fibre from the seeds, has not yet been equalled by all the mechanical skill of Europe.

[...]

Indian cotton is somewhat difficult to spin, from its often breaking, and requiring more turns of the spindle, and from its shortness of fibre, than that of America. But the yarn made from a pound of East Indian cotton, which costs 3½d. sterling, will sell for 7d., while from the American, which costs 4½d. the pound, the yarn sells for 7¾d.

[...]

The largest consumption of cotton-wool is in the tropical countries. Americans consume 11½ pounds per head ; and it has been calculated that the British Indian people consume 10 pounds per head, but Great Britain only 4½ pounds per head.

[...]

In S. India the land should be well ploughed two or three times, and the deeper the better. All the weeds should be collected into heaps on the ploughed land and burnt, as the ashes make the best manure for cotton, and burning the soil improves its quality. Salt and lime are also good additions to a soil, as cotton requires chiefly alkalies and silicates for its nourishment. Animal and vegetable manures are injurious, as they breed insects, which destroy the roots, leaves, and young pods of the cotton. After the land has been well and deeply ploughed, it should be left for three or four days to get well aired ; it may again be ploughed into long ridges four to five feet apart. The seed is to be planted on the tops of these ridges carefully, at the depth of an inch or two and at the distance of five feet between each seed, for Oopuni, Naduni, or religious cotton ; [...] Cotton seed may be sown in any month of the year, but if there is no rain, it requires to be watered about three times; it germinates about the fifth day. If sown during the monsoon, the ridges must be eight inches high, and the water must be led away from the young plants, or they rot ; the seed must be sown on the top of the ridges. If the leaves begin to get pale or to shrivel up, the remedy is to dig trenches between the plants so as to let air in about the roots, but must not injure them. The uncultivated cotton plant lives for three or four years ; but it becomes dwarfed, and produces smaller leaves and smaller pods each year till it dies. In clay or cotton soils the plants do not attain nearly the size, nor do they produce such fine leaves or pods, as on sandy or loose soils. The cotton plants require sun, air, and moisture, but not so much of the last as of sun, light, and air at the roots ; the lighter and looser the soil, the more healthy is the plant. The best soil for cotton is a sandy soil with iron and salt ; or, if far from the sea, ashes of plants or of firewood may be used as a substitute for salt. When the cotton plants have attained the height of a foot, they do not require to be much watered ; once in ten days will be sufficient. Oopura or common country cotton varies from one to six feet in height, and covers from two to five feet of ground ; on cotton soils it seldom grows to more than two feet in height. [...]

Irrigation, in Assam, is generally unnecessary, though it may be found partially beneficial in dry and sandy soils, if judiciously applied.

Irrigation is not resorted to in the Benares, Allahabad, and Jubbulpur divisions, and the feeling is against its employment. In the N.W. Provinces the cotton crop is invariably irrigated, where a want of rain is likely to prove detrimental to the plant, and the process is not supposed to be in any way injurious to the fibre.

In most parts of the Madras Presidency artificial irrigation is not carried on ; this remark applies more particularly to Coimbatore, Madura, South Arcot, Bellary, Western Mysore, and Nellore. In Vizagapatam, on the other hand, the opinion is that irrigation would prove beneficial rather than injurious in seasons when rains fail or vary in their supply.

Artificial irrigation is almost unknown in the Bombay Presidency, Bcrar, and British Burma.

In some parts of the Panjab, cotton is irrigated from wells, and well water is considered better for the purpose than river or canal water. In other parts, more especially in the Jullundhur Doab, the best cotton is produced upon unirrigated lands, irrigation being very sparingly resorted to in tracts where water is abundant.

Artificial irrigation to cotton is rather the exception than the rule in most parts of India; [...]

In the Panjab, the localities best suited for the growth of cotton arc the submontane districts of Ambala, Hoshiarpur, Gujerat, and Peshawur. The time of sowing varies from February in the south, to the middle of June in some of the northern districts. The flowering commences according to locality, between August and December; the picking following about a month after the flowering, and continues at intervals for two months. There the average produce per acre, after the cotton is cleaned from its seed, is a little over one maund (or 80 lbs.), the rate varying from three maunds (240 lbs.) of raw cotton in the Hoshiarpur, to 16 seers (32 lbs.) of cleaned cotton in the Kangra district.

The Nurma-bun cotton is cultivated in small quantities all over Hindustan, and its produce is in great request for the manufacture of the best kind of Brahmanical thread. It is a bushy plant, grows to the height of about seven feet, and lasts about six years. It is cultivated all over Oudh, usually as a mixed crop, in light soils, with arhar (Cajanus Indica), or with kodo (Paspalum scrobiculatum), and often with maize. It is sown in the month of June, It is sown broadcast with the above, and nothing is done to until it begins to ripen the pods. The cotton is picked out of the shell, which is left on the tree. The proportion of staple produced is very small. It is generally on high lands, on which the rain water does not lie.

Agra, Rohilkhand, Meerut, and Allahabad are the great cotton-producing districts of the N.W. Provinces, and their average yield per acre is moderate. In Aligurh the sowing is in June and July, and gathering from October to end of December.

In Gorakhpur and the neighbouring districts, the indigenous sorts are called Kukti, Murwa, and Desi. The Kukti kind is sown in February, in calcareous soils, when the ground has been but slightly prepared ; it is picked in September and October. It is an annual, and the same ground is never used in two consecutive seasons Murwa cotton, if carefully tended, is triennial, or even quinquennial ; it is generally grown both in silicious (bangar) or calcareous (bhat) soils, as a border round sugar-cane or vegetable plots. The Desi or indigenous variety is common to all Gorakhpur and its neighbouring districts. It is sown in June, in ground but little prepared for its reception, and does not yield till the following April, It is an annual ; bears pods for six weeks only, and is then cut down.

In Bundelkhand cotton grows to great perfection, and its produce is of a softer texture and of a whiter colour than that of the Doab. The mar or maura black soil of the first quality is the most productive, yielding on the average 286 lbs. per acre. The punca soil of Bundelkhand is reddish, a mixture of sand and clay, and yields 191 lbs. per acre, 2-7ths being the proportion of cleaned cotton. Bankar is a light-coloured, sandy, gravelly soil, which yields 143 lbs. per acre, 1-5th of the produce being cleaned cotton. In Bundelkhand cotton is sown as a mixed crop in the beginning of the rains, and if the season is favourable, picking begins in the middle of September in the poorer soils, but not till the middle or end of October in the rich ones. Two ploughings and three weedings are necessary. The seed is rubbed in moist cow-dung, to serve as manure, and is sown broadcast. The cost of cultivation per acre is Rs. 9. After the removal of the fibre, the seed (binoula) finds a ready sale in E. Oudh at 50 or 60 seers the rupee.

Jaloun, Jhansi, and Bundelkhand lie to the westward of the Jumna, and have always been famed among the natives for their cotton.

Central India cotton has always been esteemed. The soil in many places is the black cotton soil. In some parts of Nagpur the field is tilled and manured with ashes and cow-dung before sowing. In pargana Booudoo, besides the common Kapas, there are two other sorts of cotton, called Tureea and Guteh. The former is sown in October, and picked in April and May, the field being tilled ten or twelve times before sowing. The latter is sown in July ; cotton is picked two or three times in April ; the trees last from three to four years, producing cotton every year, and they are 2½ yards high. This is grown by the poorest class in their own premises. The time of picking, speaking generally, is the whole of November and December, excepting in pargana Boondoo, where, as already stated above, the Tureea and Guteh or Gujar are picked in the months of April and May.

In Berar, the Chundelee, a very fine cotton fabric of India, so costly as to be used only in native courts, was made from Amraoti cotton. The chief care bestowed was on the preparation of the thread, which, when of very fine quality, sold for its weight in silver. The weavers work in a dark under-ground room, the walls of which are kept purposely damp, to prevent dust from flying about.

[..]

Hinginghat cotton is admittedly one of the best staples indigenous to India. It is, properly speaking, the produce of the rich Wardha valley, brought for sale to the Hinginghat market ; but in good deal of the cotton known in Bombay as Hinginghat is not really produced in the neighbourhood of the town, but is grown elsewhere, attracted to Hinginghat by the ready market there found ; thus some of inferior quality goes into the market at Hinginghat. [...]

The Bombai Presidency's best cotton districts are the Southern Mahratta country, about 16° N. lat., where experimental farms were established.

In Gujerat and Kattyawar districts, superior cottons have long been grown by the natives ; in consequence of which, these were selected as the sites of the northern experimental farms, much favourable land for the purpose being found between the latitudes of 21° and 24° N. The causes which favour the growth of cotton, esteemed both in India and England, in the tract of country extending from Surat and Ahmadabad, or from about lat. 21° and 23°, in a broad band across Malwa to Banda and Rajakhaira, in about 25° and 27°, near the banks of the Jumna, are no doubt physical. The black cotton soil which is spread over a great portion of this tract, has undoubtedly a considerable share in producing the result ; but good crops of cotton are produced in some parts where there is no black soil, as immediately on the banks of the Jumna and in the Doab.

[...]

Cotton, wheat, and bajra (Penicillaria spicata) all ripen in Gujerat at the same period of the year, about the end of February, and the cotton-picking continues to the middle of April. The first picking of cotton affords the best kind, the second is the most abundant, and the third is greatly inferior to the other two, both in quantity and in quality.

In Cuttack and Orissa there are two highland or upland varieties, the one called the Daloona, because the plants throw out numerous branches. The second kind of upland is called yellow, from the colour of the flowers; the flower of the Daloona being white. A third variety may be called the lowland, and is known locally as the Keda. The upland varieties are grown more or less all over the Gurjuto or Hill States, wherever a virgin forest soil exists. They are grown generally in the Sumbulpore district and its dependencies, throughout the Tributary States, and in Dhenkanal and Khoordah. A virgin forest soil is the only requisite for the successful cultivation of these varieties. The jungle is cut down, all the brushwood cleared, heaped and burnt on the spot, the stems and roots of the larger trees being left in the ground, which then receives a superficial ploughing. These clearings are called taela, and the cotton grown in them Taela cotton. These preparatory processes are attended to in Sumbulpore, Khoordah, and Dhenkanal, just before and during the first falls of rain, in the latter half of May and the first half of June, so that the plants shoot and grow and arrive at maturity through the rainy months. Dwarf paddy, sooa, Panicum Italicum, Eleusine coracana, bajra, or castor-oil, are sown with the cotton seed broadcast. The edible seed-crops in the third or fourth month are gathered as they ripen, then the ground is weeded and turned about. In January and February the cotton plants yield the first picking, and a month after the castor-oil seed ripens, and its plants are plucked and removed. Daloona cotton plants last for two or three years, and yield three pickings annually, and reach a height of 9 to 12 feet. With the yellow upland, it is not so generally the practice of sowing other crops.

The cultivation of the Keda or lowland variety of cotton is confined almost to the settled and open districts of Cuttack, Puri, and Balasore ; a little is raised in Dhenkanal and Khoordah. The best soil selected for this variety is dofuslee, or double crop. It is generally a light sandy soil, handy for irrigation purposes. The seed used throughout the district for lowland cotton is procured from Khoordah and Dhenkanal, it being alleged that none other will germinate in the lowland districts. It is placed in a pot, and soaked in dung and water for a night, and then dried by exposure to the sun on the following day. It is afterwards laid on straw, contained in an earthen vessel covered over with castor-oil leaves and placed near a fire. So soon as the seed splits and shoots it is planted, and watered at intervals of two, three, and four days. November and December are the usual months for the planting. The plants are annual, and attain a height of 4 to 6 feet. The cold weather showers falling occasionally in December, January, and February, favour the plants, and when plentiful, constitute a good season. The pickings are obtained continuously in April, May, and June. In the latter month all the bolls are picked off the plants, and after exposure to the sun, open. After the month of June, the lowland cotton plants are plucked up, and the land cleared for a pulse crop.

[...]

In Bellary cotton is grown in drills along with cholum or millet ; with the former, the drills are about six feet apart, and have from four to six rows of sorghum between each one of cotton; with the latter, the drills of cotton are only three feet apart, and have two rows of millet between them. When the crop of the millet is cut down, a very singular and sudden change occurs ; one day nothing is seen but yellow grain, which on the next disappears, and a thick crop of green cotton plants, about half a yard high, remains. [...]

In Vizagapatam, about lat. 17° N., very liberal pruning is practised, and the return is much greater than in any other of the Madras districts. In sandy soils near the sea, the Oopum cotton yields the more largely.

In Mysore, large belts of land in the northern and central taluks are deemed excellent for cotton culture.

[...]

In Ceylon, cotton is grown very generally both by the Singhalese and Tamil races, but upon no regular plan nor to any extent.

Bengal Presidency. — The indigenous cotton of Dacca has long been celebrated for its superior quality. It is cultivated along the banks of the Megna from Feringybazar to Edilpore in Bakarganj, a distance of about forty miles, on the banks of the Brahmaputra creek (the ancient channel of the river of the same name), and along the Luckia and Banar. It presents different shades of quality, the finest of which is named Photee, and is the material of which the delicate muslins are made. It was described by Roxburgh as differing from the common herbaceous cotton plant of Bengal in several particulars, chiefly in having a longer, finer, and softer fibre. It has, however, often been doubted whether the superiority of the Dacca manufacture was dependent on the skill of the workmen or he goodness of the cotton ; but, from Mr. Lamb's account, it appears to have been carefully cultivated. Probably both both had some influence; and it is certain that the workmen prefer the Dacca cotton, because, as Mr. Webb long ago explained, its thread does not swell in bleaching, as is the case with the cotton grown in Northwestern and Central India.

In Burdwan the Wesbee or native cotton plant is sown in the month Ashar. The soil is ploughed four or five times, the seed is kept in water for three or four days, is taken out on the day before it has to be sown, and is then mixed with ashes and cow-dung, and in this state is scattered over the ground, which is then again ploughed. Some cultivators, however, put four or five seeds small holes at the interval of about 1½ cubits. In the month of Magh (January—February), when the plants become ½ cubit high, they are watered. The picking of the Wesbee cotton is commenced in the month of Cheyt, corresponding with April, and finished in June and July (Joyte). Nurma cotton is cultivated in the month of Ashar, corresponding with June. The roots of the plants are well covered with earth. No irrigation is required, as nurma cotton is a rainy season plant. Its cotton is picked in November and December.

The Garo, Tiperah, and Chittagong hills produce a large quantity of inferior cotton, called Bhoga. It is used in the manufacture of the inferior kinds of hummum, bafta, boonee, saree, jore, etc., also for making ropes and tapes, and the coarsest of all fabrics, viz. garlia and guzeeh, which are commonly used for packing other cloths, and for covering dead bodies, for which purpose a large quantity of them is consumed annually both by Hindus and Mahomedans. A piece of guzeeh cloth, measuring 10 yards, could be purchased for 12 annas (eighteen pence), which is the one hundred and twenty-fifth part of the price paid for a piece of mulmul-i-khas of the same dimensions.

In Tirhut the cottons produced are of the kinds called Bhojra, Bhogla, and Kooktee; the two former ripen in April and May, the Kooktee ripens in September. The fabric manufactured from Kooktee cotton is not white, but of a stained white colour, white cotton being produced only from the Bhojra and Bhogla kinds.

The soil upon which the cotton plant in Cachar is grown, consists of a rich red clay, considerably mixed with sand, which forms the soil of the principal hills in the district, and also of the small ranges of hillocks that run through it. The cotton cultivation lies on the slopes of these hills and mountains, such lands being never inundated, although they are wonderfully retentive of moisture. The same hills and slopes became in great request for the cultivation of the tea plant, the soil being peculiarly adapted for its growth. The cotton seeds, together with others, are put in in March and April ; they are planted irregularly, but never closer than from 3 or 4 feet apart. The whole cultivation is weeded three or four times during the rains. The cotton flowers in July and August ; the picking commences in September, and is continued till December."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 822 - 828.]

"COTTON MANUFACTURES. Amongst the goods which appear to have been brought to Europe from the Indian seas, in the days when Arab traders were the only medium of intercourse between the eastern and western worlds, we find mentioned cloths of silk and cotton of various colours and devices. It docs not appear, however, that there existed in Europe any great demand for cotton,—the consumption of the Roman people, who were then the customers for all luxuries, being chiefly confined to cloths of silk and wool. During the trade of Europeans with India by the long sea route, the calicoes and fine muslins of that country came into general notice; and until the production of machine-made fabrics in Britain, they continued to rise in public estimation. It was deemed a great thing with the Lancashire manufacturers, when, by the aid of mechanical and artistic skill, combined with the potent agency of steam, they found themselves able to produce an article which was considered equal to that which the unlettered Hindu had manipulated in his little mud hut on the remote banks of the Ganges, and which had been produced of like excellence by their ancestors, when the 'father of history ' penned his observations upon their countries. That the Hindus paid considerable attention to the details of this manufacture in the most remote ages, there remains sufficient proof on record. In the Indian work of highest antiquity the Rg Veda, believed to have been written fifteen centuries previous to the Christian era, occurs the following passage : 'Cares consume me, Satakralu ! although thy worshipper, as a rat gnaws a weaver's threads,'—the temptation to the rat being evidently the starch employed by the spinner to impart tenacity to the thread ; nor can there be any doubt that cotton was the thread alluded to. Again, in the Institutes of Menu, we find it directed as follows : 'Let the weaver who has received ten palas of cotton thread, give them back increased to eleven by the rice-water (starch) and the like used in weaving ; he who does otherwise shall pay a fine of twelve panas.' In recent times the cotton fabrics of India formed a considerable item in the exports from the East, during the early days of British Indian commerce ; the delicacy of their fabric, the elegance of their design, and the brilliancy of their colours, render them as attractive to the belter classes of consumers in Groat Britain, an are, in the present day, the shawls of Kashmir or the silks of Lyons. So much superrior, indeed, were the productions of the Indian spinning-wheel and handloom, to those turned out by the manufacturers of Lancashire in the middle of the 18th century, that not only were Indian calicoes and Indian prints preferred to the British-made articles, but the Manchester and Blackburn weavers actually imported Indian yarns in large quantities for employment in their factories. It was about the year 1771-72 that the Blackburn weavers, taking advantage of the discoveries and improvements of Arkwright, Hargreaves, and others, found themselves in a position to produce plain cotton goods, which, if they did not quite equal the fabrics of the East, at any rate found their way very rapidly into general consumption in Europe. The invention of the mule jenny in 1779 was the commencement of a new era in the history of the cotton manufacture of Great Britain ; and when, six years later, Arkwright's machines were thrown open to the public, a revolution was effected in the production of all kinds of yams. Great Britain found herself able not only to supply all her own wants with cotton goods of every variety of quality, but also to carry the produce of her looms 10,000 miles across the sea, and, placing them at the doors of the Indian consumer, undersell some kinds of the goods made by their own hands from cotton grown in his own garden. Nor is it only in the heavier goods that the West are able to beat out of their own markets the weaver of the East. There have been masters in their craft who produced fabrics more exquisitely delicate and light in texture than those beautiful muslins of Dacca, so long and justly celebrated with a world-wide fame. Although in some particulars these latter fabrics claim a certain degree of superiority, many of the Hindus prefer much of their own woven goods to those of Manchester and Glasgow ; and the cotton manufactures of British India have been steadily advancing in the out-turn of twist and yarn and piece-goods. It is generally believed that Manchester will fail to contend with the Indian mills in respect to the precise class of goods they are in the habit of turning out. The cotton mills of Bombay have made, since the date of their first starting in 1854, very rapid progress.

In the 25 years between 1857-58 and 1881-82, the value of all the cotton goods imported into British India from foreign countries rose from £5,726,018 to £20,772,098. Since 1868-69 the values of the twist and yarn and of the piece-goods have but little increased. In 1881-82 the twist and yarn was of value £32,220,648. British India has been latterly holding its own. The exports have consisted of cotton goods, including twist and yarn, and have risen from £637,651 in 1850-51, to £1,906,868 in 1881-82.

The yearly increasing exports from Europe misled exporters, for Europe had seldom been able to compete either with the delicate hand-made fibres which the Hindus and Mahomedans have been producing, or with the strong, coarse fabrics which the village weavers produce during the slack time of their agricultural pursuits. In the middle of the 19th century, British India also began to use machinery. In 1880 there were 58 cotton mills at work in British India, with 1,471,730 spindles, mules, and throstles, and 13,283 looms, turning out twist and yarn and cotton cloths, with a nominal capital of four millions sterling.

"With their rude implements the Hindus of Dacca formerly manufactured muslins, to which," as Dr. Ure observed, "European ingenuity can afford no parallel,—such, indeed, as has led a competent judge to say it is beyond his conception how this yarn, greatly finer than the highest number made m England, can be spun by the distaff and spindle, or woven by any machinery" (Ure"s Cotton Manufacture of Great Britain, i. p. 54).

The jawbone of the boalee fish (Silurus boalis), the teeth of which being fine, re-curved, and closely set, serves as a fine comb in removing minute particles of earthy and vegetable matter from the cotton. The Hindu spinner, with that inexhaustible patience which characterizes the race, sits down to the laborious task of cleaning with this instrument the fibres of each seed of cotton. Having accomplished this, she then separates the wool from the seeds by means of a small iron roller (dullun kathee), which is worked with the hands backward and forward, on a small quantity of the cotton seeds placed upon a flat board. The cotton is next bowed or teased with a small bow of bamboo, strung with a double row of catgut, muga silk, or the fibres of the plantain tree twisted together; and, having been reduced by this instrument to a state of light downy fleece, it is made up into a small cylindrical roll (puni), which is held in the hand during the process of spinning. The spinning apparatus is contained in a small basket or tray, not unlike the catheterae of the ancient Greeks. It consists of a delicate iron spindle (tukooa), having a small ball of clay attached to it, in order to give it sufficient weight in turning ; and of a piece of hard shell imbedded in a little clay, on which the point of the spindle revolves during the process of spinning. With this instrument the Hindu women almost rival Arachne's fabled skill in spinning. The thread which they make with it is exquisitely fine ; and -doubtless it is to their delicate organization and the sensibllity with which they are endowed by nature, that their inimitable skill in their art is to be ascribed. The finest thread is spun early in the morning, before the rising sun dissipates the dew on the grass, for such is the tenuity of its fibre, that it would break if an attempt were made to manufacture it during a drier and warmer portion of the day. The cohesive property of the filaments of cotton is impaired by high temperature accompanied with dryness of the air, and hence, when there is no dew on the ground in the morning to indicate the presence of moisture in the atmosphere, the spinners impart the requisite degree of humidity to the cotton, by making the thread over a shallow vessel of water.

A specimen which Dr. Taylor examined at Dacca in 1846 measured 1349 yards, and weighed only 22 grains, which is in the proportion of upwards of 250 miles to a pound weight of staple. During the process of preparing the thread, and before it is warped, it is steeped for a couple of days in fine charcoal powder, soot, or lampblack, mixed with water, and, after being well rinsed in clear water, wrung out, and dried in the shade, it is rubbed with a sizing made of parched rice (the husk of which has been removed by heated sand), fine lime, and water. The loom is light and portable ; its cloth and yarn beans, batten, templet, and shuttle are the appurtenances requisite for weaving.

Dacca was the seat of a manufacture of muslins known by its name, and spoken of by the ancients as 'woven webs of air.' The principal varieties of plain muslins manufactured at Dacca were Mulmul-i-Khas, Ab-rawan, Shab-nam, Khasa, Jhuna, Sircar Ali, Tanzeb, Alabullee, Nyan-zook, Baddan Khas, Turandam, Sarbutee, and Sarband, —names which either denote fineness, beauty, or transparency of texture, or refer to the origin of the manufacture of the fabrics, or the uses to which they are applied as articles of dress. The finest of all was the Mulmul-i-Khas (literally, muslin made for the special use of a prince or great personage). It was woven in half-pieces, measuring 10 yards in length and 1 yard in breadth, having 1900 threads in the warp, and weighing 10 siccas (about 3¾ ounces avoirdupois). The finest half-piece seen weighed 9 siccas, priced 100 rupees. Some of the other muslins were also beautiful productions of the loom, as Ab-rawan, compared by the natives from its clear pellucid texture to running water. Shab-nam, so named from its resemblance, when it is wetted and spread upon the bleaching field, to the evening dew on the grass. Jhuna, a light transparent net-like fabric, made for natives of rank and wealth, worn by the inmates of zenanas and dancers, and apparently the cloth referred to in the classics under the figurative names of Tela arenarum, Ventus textilis. All these muslins were made in full pieces of 20 yards in length by 1 in breadth, but varying considerably in the number of threads in the warp, and consequently in their weight. Of figured fabrics, as striped Dooria, chequered Charkhanee, and flowered Jamdanee, there exists a considerable variety, both in regard to quality and pattern. The flowered muslin was formerly in great demand both in India and Europe, and was the most expensive manufacture of the Dacca Urung, There was a monopoly of the finer fabrics for the court of Dehli ; those made for the emperor Aurangzeb cost 250 rupees per piece. This muslin is now seldom manufactured of a quality of higher value than 80 rupees per piece.

For the masses of the people, the British manufacturer sends to India the plain and striped Dooria, Mulmul, Aghabani, and other figured fabrics, which have established themselves there, and which, both from their good quality and moderate prices, are acceptable to the numerous classes who make use of them. Some of the chintzes of Masulipatam and of the south of India are as beautiful in design as they are chaste and elegant in colour.

Printed cloths are worn occasionally, as in Berar and Bundelkhand, for sarees ; and the ends and borders have peculiar local patterns. There is also a class of prints on coarse cloth, used for the skirts or petticoats of women of some of the poorer classes in Upper India ; but the greatest need of printed cloths is for the kind of bedcover called palempore (palangposh), or single quilts.

In the costlier cloths woven in India, the borders aiid ends are entirely of gold thread and silk, the former predominating. Many of the saree or women's cloths, made at Benares, Pytun, and Burhanpur, in Gujerat, at Narrainpet and Dhanwarum in the Hyderabad territory, at Yeokla in Kandesh, and in other localities, have gold thread in broad and narrow stripes alternating with silk or muslin. Gold flowers, checks, or zigzag patterns are used, the colours of the grounds being green, black, violet, crimson, purple, and grey ; and in silk, black shot with crimson or yellow, crimson with green, blue, or white, yellow with deep crimson and blue, all producing rich, harmonious, and even gorgeous effects, but without the least appearance of or approach to glaring colour, or offence to the most critical taste. They are colours and effects which suit the dark or fair complexions of the people of the country ; for an Indian lady who can afford to be choice in the selection of her wardrobe, is as particular as to what will suit her especial colour—dark or comparatively fair—as any lady of England or France. Another exquisitely beautiful article of Indian costume for men and women is the do-patta or scarf, worn more frequently by Mahomedan women than Hindu, and by the latter only when they have adopted the Mahomedan lunga or petticoat ; but invariably by men in dress costume. By women this is generally passed once round the waist over the petticoat or trousers, thence across the bosom and over the left shoulder and head ; by men, across the chest only.

The do-pattas, especially those of Benares, are perhaps the most exquisitely beautiful of all the ornamental fabrics of India ; and it is quite impossible to describe the effects of gold and silver thread, of the most delicate and ductile description imaginable, woven in broad, rich borders, and profusion of gold and silver flowers, or the elegance and intricacy of most of the arabesque patterns of the ribbon borders or broad stripes.

How such articles are woven at all, and how they are woven with their exquisite finish and strength, fine as their quality is, in the rude handlooms of the country, it is hard to understand. All these fabrics are of the most delicate and delightful colour,—the creamy white, and shades of pink, yellow, green, mauve, violet, and blue, are clear yet subdued, and always accord with the thread used, and the style of ornamentation, whether in gold or silver, or both combined. Many are of more decided colours—black, scarlet, and crimson, chocolate, dark green, and madder ; but whatever the colour may be, the ornamentation is chaste and suitable. For the most part, the fabrics of Benares are not intended for ordinary washing ; but the dyers and scourers of India have a process by which the former colour can be discharged from the fabric, and it can then be re-dyed. The gold or silver work is also carefully pressed and ironed, and the piece is restored, if not to its original beauty, at least to a very wearable condition.

The do-pattas of Pytun, and indeed most others except Benares, are, of a stronger fabric. Many of them are woven in fast colours, and the gold thread—silver is rarely used in them—is more substantial than that of Benares. On this account they are preferred in Central India and the Dekhan,—not only because they are ordinarily more durable, but because they bear washing or cleaning better. In point of delicate beauty, however, if not of richness, they are not comparable with the fabrics of Benares.

Scarfs are in use by every one,—plain muslins, or muslins with figured fields and borders without colour, plain fields of muslin with narrow edging of coloured silk or cotton (avoiding gold thread), and narrow end. Such articles, called sehla in India, are in everyday use among millions of Hindus and Mahomedans, men and women. They are always open-textured muslins, and the quality ranges from very ordinary yarn to that of the finest Dacca fibres. Comparatively few native women of any class or degree wear white ; if they do wear it, the dress has broad borders and ends. But what all classes wear are coloured cloths,—black, red, blue, occasionally orange and green, violet, and grey. All through Western, Central, and Southern India, sarees are striped and checked in an infinite variety of patterns. Narrainpet, Dhanwar, and Muktul, in the Nizam's territories ; Gudduk and Bettigerry in Dharwar ; Kolhapur, Nasik, Yeokla, and many other manufacturing towns in the Dekhan ; Arnee in the south, and elsewhere, send out articles of excellent texture, with beautifully arranged colours and patterns, both in stripes and checks. The costly and superb fabrics of cloths of gold and silver (kimkhab), and the classes of washing satins (mushroo and hemroo), even if European skill could imitate them by the handloom, it would be impossible to obtain the gold and silver thread unless they were imported from India. The native mode of making this thread is known, but the result achieved by the Indian workman is simply the effect of skilful and delicate manipulation. The gold and silver cloths (kimkhab) are used for state dresses and trousers, the latter by men and women ; and ladies of rank usually possess petticoats or skirts of these gorgeous fabrics. Mushroo and hemroo are not used for tunics, but for men's and women's trousers, and women's skirts ; as also for covering bedding and pillows. They are very strong and durable fabrics, wash well, and preserve their colour, however long worn or roughly used ; but they can hardly be compared with English satins, which, however, if more delicate in colour and texture, are unfitted for the purposes to which the Indian fabrics are applied. For example, a labada or dressing-gown, made of scarlet mushroo in 1842, has been washed over and over again, and subjected to all kinds of rough usage, yet the satin is still unfrayed, and the colour and gloss as bright as ever. Many of the borders of loongees, dhotees, and sarees are like plain silk ribbons, in some instances corded or ribbed, in others flat.

In Europe, it has been usual to name particular fabrics after the place of their manufacture, and this practice was extended to eastern products, as calico from Calicut, gauze from Gaza, muslin from Mosul, chintz from the Hindi chinte, spotted. In British India, however, the people name their woven fabrics from the form of their construction, their appearance, or the use to which they are applied. The cotton goods sent from Bombay to the Paris Exhibition of 1855, comprised bafta, boonee, carpets, chandni, choli, dastarkhau, dhoti, ek-patta, dopatta, dungari, khadi, lungee, pesfgir, phatka, pagga, quilts, razai, sailcloth, saree, soosi, turband, tablecloth, table napkins, and towels.

Omitting the second-rate kinds of cloth, which constitute the great bulk of the Dacca cotton manufacture, a class worthy of attention is that of fabrics of a mixed texture of cotton and silk. They are designated by various names, as nowbuttee, kutan, roomee apjoola, and lucka ; and, when embroidered with the needle, as many of them frequently are, they are called kusheeda. The silk used in their manufacture is the indigenous muga silk of Assam and Sylhet ; but the cotton thread employed is now almost entirely English yarn, of qualities varying from Nos. 30 to 80. These cloths are made exclusively for the Jedda and Bussora market ; and a considerable stock is yearly exported in the Arab vessels that trade between Calcutta and these ports. Pilgrims, too, from the vicinity of Dacca not unfrequently take an investment of them, which they dispose of at the great annual fair held at Meena, near Mecca. They are used by the Arabs chiefly for turbands and gowns. The golden colour of the muga silk gives to some of these a rich lustrous appearance. Pieces made of native-spun cotton thread and of the best kind of muga silk, would be admired in England.

In Ganjam is fabricated a cotton cloth, each side of a different colour. This effect is produced not by dyeing the cloth after it is woven, but by a dexterous manner of throwing the woof across the warp on either side. Madapollam and Ingeram used to be famous for cotton cloths, but since the abolition of the Company's trade, the finer panjaras have not been made. Palampores, as bed coverings, of the former place deserve attention. Very fine muslins are made at Oopada, north of Cocanada, and handsome turbans, with gold thread interwoven; but all these things are far surpassed by the Bengal fabrics. The Chicacole muslins are, however, prized by European ladies. Cotton cloths from Nellore consist of manufactured articles which find a ready sale in the markets of this Presidency."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 829 - 832.]

"Gossypium Indicum (Linn.) N. O. Malvaceae. Indian Cotton plant [...]

Description.--Herbaceous ; [...]

Royle.

G. herbaceum, Linn.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii 184.—Royle. Ill. Him. Bot. t. 23, fig. 1.

Cultivated.

Economic Uses. — As flax is characteristic of Egypt, and the hemp of Europe, so cotton may truly be designated as belonging to India. Long before history can furnish any authentic account of this invaluable product, its uses must have been known to the inhabitants of this country, and their wants supplied from time immemorial, by the growth of a fleecy-like substance, covering the seeds of a plant, raised more perhaps by the bounty of Providence than the labour of mankind.

In Sanscrit, cotton is called kurpas, from whence is derived the Latin name carbasus, mentioned occasionally in Roman authors. This word subsequently came to mean sails for ships and tents. Herodotus says, talking of the products of India,—" And certain wild trees bear wool instead of fruit, that in beauty and quality exceeds that of sheep: and the Indians make their clothing from these trees" (iii. 106). And in the book of Esther (i. 6) the word green corresponds to the Hebrew kurpas, and is in the Vulgate translated carbasinu8. The above shows from how early a period cotton was cultivated in this country. "The natives," says Royle (alluding to its manufacture in India), " of that country early attained excellence in the arts of spinning and weaving, employing only their Angers and the spinning-wheel for the former; but they seem to have exhausted their ingenuity when they invented the hand- loom for weaving, as they have for ages remained in a stationary condition."

It has sometimes been considered a subject of doubt whether the cotton was indigenous to America as well as Asia, but without sufficient reason, as it is mentioned by very early voyagers as forming the only clothing of the natives of Mexico; and, as stated by Humboldt, it is one of the plants whose cultivation among the Aztec tribes was as ancient as that of the Agave, the Maize, and the Quinoa (Chenopodium). If more evidence be required, it may be mentioned that Mr Brown has in his possession cotton not separated from the seeds, as well as cloth manufactured from it brought from the Peruvian tombs; and it may be added that the species now recognised as American differ in character from all known Indian species (Royle).

Cotton is not less valuable to the inhabitants of India than it is to European nations. It forms the clothing of the immense population of that country, besides being used by them in a thousand different ways for carpets, tents, screens, pillows, curtains, &c. The great demand for cotton in Europe has led of late years to the most important consideration of improvements in its cultivation. The labours and outlay which Government has expended in obtaining so important an object have happily been attended with the best results. The introduction of American seeds and experimental cultivation in various parts of India have been of the greatest benefit. They have been the means of producing a better article for the market, simplifying its mode of culture, and proving to the Ryots how, with a little care and attention, the article may be made to yield tenfold, and greatly increase its former value. To neither the soil nor the climate can the failure of Indian cotton be traced: the want of easy transit, however, from the interior to the coast, the ruinous effect of absurd fiscal regulations, and other influences, were at work to account for its failure. In 1834, Professor Boyle drew attention to two circumstances : " I have no doubt that by the importation of foreign, and the selection of native seed—attention to the peculiarities not only of soil but also of climate, as regards the course of the seasons, and the temperature, dryness, and moisture of the atmosphere, as well as attention to the mode of cultivation, such as preparing the soil, sowing in lines so as to facilitate the circulation of air, weeding, ascertaining whether the mixture of other crops with the cotton be injurious or otherwise, pruning, picking the cotton as it ripens, and keeping it clean—great improvement must take place in the quality of the cotton. Experiments may at first be more expensive than the ordinary culture; the natives of India, when taught by example, would adopt the improved processes as regularly and as easily as the other; and as labour is nowhere cheaper, any extra outlay would be repaid fully as profitably as in countries where the best cottons are at present produced."

The experiments urged by so distinguished an authority were put in force in many parts of the country, and notwithstanding the great prejudice which existed to the introduction of novelty and other obstacles, the results have proved eminently successful. It has been urged that Indian cotton is valuable for qualities of its own, and especially that of wearing well. It is used for the same purposes as hemp and flax, hair and wool, are in England. There are, of course, a great many varieties in the market, whose value depends on the length, strength, and fineness as well as softness of the material, the chief distinction being the long stapled and the short stapled. Cotton was first imported into England from India in 1783, when about 114,133 lb. were received. In 1846, it has been calculated that the consumption of cotton for the last 30 years has increased at the compound ratio of 6 per cent, thereby doubling itself every twelve years. The chief parts of India where the cotton plant is cultivated are in Guzerat, especially in Surat and Broach, the principal cotton districts in the country; the southern Mahratta countries, including Dharwar, which is about a hundred miles from the seaport; the Concans, Canara, and Malabar. There has never been any great quantity exported from the Madras side, though it is cultivated in the Salem, Coimbatore, and Tinnevelly districts, having the port of Tuticorin on one coast, and of late years that of Cochin on the other, both increasing in importance as places of export In the Bengal Presidency, Behar and Benares, and the Saugor and Nerbudda territories, are the districts where it is chiefly cultivated.

The present species and its varieties are by far the most generally cultivated in India. Dacca cotton is a variety chiefly found in Bengal, furnishing that exceedingly fine cotton, and employed in manufacturing the very delicate and beautiful muslins of that place, the chief difference being in the mode of spinning, not in any inherent virtue in the cotton or soil where it grows. The Berar cotton is another variety with which the N. Circar long-cloth is made. This district, since it has come under British rule, promises to be one of the most fertile and valuable cotton districts in the whole country.

Much diversity of opinion exists as to the best soil and climate adapted for the growth of the cotton plant; and considering that it grows at altitudes of 9000 feet, where Humboldt found it in the Andes, as well as at the level of the sea, in rich black soil and also on the sandy tracts of the sea-shore, it is superfluous to attempt specifying the particular amount of dryness or moisture absolutely requisite to insure perfection in the crop. It seems to be a favourite idea, however, that the neighbourhood of the sea-coast and islands are more favourable for the cultivation of the plant than places far inland, where the saline moisture of the sea-air cannot reach. But such is certainly not the case in Mexico and parts of Brazil, where the best districts for cotton-growing are far inland, removed from the influence of sea-air. Perhaps the different species of the plant may require different climates. However that may be, it is certain that they are found growing in every diversity of climate and soil, even on the Indian continent; while it is well known that the best and largest crops have invariably been obtained from island plantations, or those in the vicinity of the sea on the mainland.

A fine sort of cotton is grown in the eastern districts of Bengal for the most delicate manufactures; and a coarse kind is gathered in every part of the province from plants thinly interspersed in fields of pulse or grain. Captain Jenkins describes the cotton in Cachar as gathered from the Jaum cultivation : this consists in the jungle being burnt down after periods of from four to six years, the ground roughly hoed, and the seeds sown without further culture. Dr Buchanan Hamilton, in his statistical account of Dinagepore, gives a full account of the mode of cultivation in that district, where he says some cotton of bad quality is grown along with turmeric, and some by itself, which is sown in the beginning of May, and the produce collected from the middle of August to the middle of October, but the cultivation is miserable. A much better method, however, he adds, is practised in the south-east parts of the district, the cotton of which is finer than that imported from the west of India: The land is of the first quality, and the cotton is made to succeed rice, which is cut between August and the middle of September. The field is immediately ploughed until well broken, for which purpose it may require six double ploughings. After one-half of these has been given, it is manured with dung, or mud from ditches. Between the middle of October and the same time in November, the seed is sown broadcast; twenty measures of cotton and one of mustard. That of the cotton, before it is sown, is put into water for one-third of an hour, after which it is rubbed with a little dry earth to facilitate the sowing. About the beginning of February the mustard is ripe, when it is plucked and the field weeded. Between the 12th of April and 12th of June the cotton is collected as it ripens. The produce of a single acre is about 300 lb. of cotton, worth ten rupees; and as much mustard-seed, worth three rupees. A still greater quantity of cotton, - Dr Hamilton continues, is reared on stiff clay-land, where the ground is also high and tanks numerous. If the soil is rich it gives a summer crop of rice in the same year, or at least produces the seedling rice that is to be transplanted. In the beginning of October the field is ploughed, and in the end of the month the cotton-seed is sown, mingled with Sorisha or Lara (species of Sinapis and Eruca); and some rows of flax and safflower are generally intermixed. About the end of January, or later, the oil-seeds are plucked, the field is hoed and manured with cow-dung and ashes, mud from tanks, and oil-cake; it is then watered once in from eight to twelve days. The cotton is gathered between the middle of April and the middle of June, and its produce may be from 360 to 500 lb. an acre.

In the most northern provinces of India the greatest care is bestowed on the cultivation. The seasons for sowing are about the middle of March and April, after the winter crops have been gathered in, and again about the commencement of the rainy season. The crops are commenced being gathered about the conclusion of the rains, and during October and November, after which the cold becomes considerable, and the rains again severe. About the beginning of February the cotton plants shoot forth new leaves, produce fresh flowers, and a second crop of cotton is produced, which is gathered during March and beginning of April. The same occurs with the cottons of Central India, one crop being collected after the rains and the other in February, and what is late in the beginning of March.

I venture to insert here the following interesting particulars about cotton manufacture : " The shrub Perutti, which produces the finer kind of cotton, requires in India little cultivation or care. When the cotton has been gathered it is thrown upon a floor and threshed, in order that it may be separated from the black seeds and husks which serve it as a covering. It is then put into bags or tied up in bales containing from 300 to 320 lb. of 16 oz. each. After it has been carded it is spun out into such delicate threads that a piece of cotton cloth 20 yards in length may almost be concealed in the hollows of both hands. Most of these pieces of cloth are twice washed; others remain as they come from the loom, and are dipped in cocoa-nut oil in order that they may be longer preserved. It is customary also to draw them through conjee or rice-water, that they may acquire more smoothness and body. This conjee is sometimes applied to cotton articles in so ingenious a manner that purchasers are often deceived, and imagine the cloth to be much stronger than it really is; for as soon as washed the conjee vanishes, and the cloth appears quite slight and thin.

"There are reckoned to be no less than 22 different kinds of cotton articles manufactured in India, without including muslin or coloured stuffs. The latter are not, as in Europe, printed by means of wooden blocks, but painted with a brush made of coir, which approaches near to horse-hair, becomes very elastic, and can be formed into any shape the painter chooses. The colours employed are indigo (Indigofera tinctoria), the stem and leaves of which plant yield that beautiful dark blue with which the Indian chintzes, coverlets, and other articles are painted, and which never loses the smallest shade of its beauty. Also curcuma or Indian saffron, a plant which dyes yellow; and lastly, gum-lac, together with some flowers, roots, and fruits which are used to dye red. With these few pigments, which are applied sometimes singly, sometimes mixed, the natives produce on their cotton cloths that admirable and beautiful painting which exceeds anything of the kind exhibited in Europe.

" No person in Turkey, Persia, or Europe has yet imitated the Betilla, a certain kind of white East Indian chintz made at Masulipatam, and known under the name of Organdi. The manufacture of this cloth, which was known in the time of Job, the painting of it, and the preparation of the colours, give employment in India to male and female, young and old. A great deal of cotton is brought from Arabia and Persia and mixed with that of India."—Bart. Voy. to East Indies.

The remaining uses of this valuable plant must now claim our attention. The seeds are bruised for their oil, which is very pure, and is largely manufactured at Marseilles from seeds brought from Egypt. These seeds are given as a fattening food to cattle. Cottonseed cake is imported from the West Indies into England, being used as a valuable food for cattle. The produce of oil-cake and oil from cotton-seeds is, 2 gallons of oil to 1 cwt. of seeds, and 96 lb. of cake. A great quantity is shipped from China, chiefly from Shanghai, for the English market. It forms an invaluable manure for the farmer.—Royle on Cotton Cultivation. Simmonds. Lindley. Roxb."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"GOSSYPIUM STOCKSII, Mast., var.herbaceum, Linn.

Fig.—Wight Ic, t. 9,11 ; Royle Ill. t. 23.

Cotton plant

Hab.--Sindh. Cultivated in most hot coutries.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—Cotton, the Karpasi of Sanskrit writers, was doubtless first known and made use of by the Hindus; it is the βυσσος of the later Greek writers, such as Philostratus and Pausanias, but not of the earlier Greeks, who applied this term to a fine kind of flax used for making mummy cloths. Theophrastus calls it Eriophora, Pliny Gossympinus, Gossypion, and Xylinum. In Arabic cotton is kuttun and kurfuss, the latter term being evidently derived from the Sanskrit. Eastern physicians consider all parts of the cotton plant to be hot and moist; a syrup of the flowers is prescribed in hypochondriasis on account of its stimulating and exhilarant effect; a poultice of them is applied to burns and scalds. Cotton cloth or mixed fabrics of cotton with wool or silk are recommended as the most healthy for wear. Burnt cotton is applied to sores and wounds to promote healthy granulation ; dropsical or paralysed limbs are wrapped in cotton after the application of a ginger or zedoary lep (plaster); pounded cotton seed, mixed with ginger and water, is applied in orchitis. Cotton is also used as a moxa, and the seeds as a laxative, expectorant, and aphrodisiac. -The juice of the leaves is considered a good remedy in dysentery, and the leaves with oil are applied as a plaster to gouty joints ; a hip bath of the young leaves and roots is recommended in uterine colic. In the Concan the root of the Deokapas (fairy or sacred cotton bush) rubbed to a paste with the juice of patchouli leaves, has a reputation as a promoter of granulation in wounds, and the juice of the leaves made into a Paste with the seeds of Vernonia anthelmintica is applied to eruptions of the skin following fever. In Pudukota the leaves ground and mixed with milk are given for strangury.

Cotton root bark is official in the United States Pharmacopoeia, also a fluid extract of the bark ; it appears to have first attracted attention from being used by the female negroes to produce abortion. There appears to be little doubt that it acts like ergot upon the uterus, and is useful in dysmenorrhea and suppression of the menses when produced by cold; a decoction of 4 ounces of the bark in two pints of water boiled down to one pint may be used in doses of two ounces every 20 or 30 minutes, or the fluid extract may be prescribed in doses of from 30 to 60 minims. Cotton seed tea is given in dysentery in America; the seeds are also reputed to be galactagogue. (Stillé and Maisch., Nat. Disp., p. 678.) By treating cotton first with a dilute alkali, then with a 5 per cent, solution of chloride of lime, and lastly with water acidulated with hydrochloric acid, and afterwards well washing it with water, it loses its greasiness and becomes absorbent and a valuable dressing for wounds; this absorbent cotton may be medicated by sprinkling it with solutions of carbolic acid, salicylic acid, boracic acid, &c. Pyroxylin or Gun Cotton is made by dipping cotton into a mixture of equal parts of nitric and sulphuric acids, washing freely with water, and drying."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 224ff.]

| 106c./d. raṅga-vaṅge atha picus tūlo

'tha kamalottaram 107a./b. syāt kusumbhaṃ vahniśikhaṃ mahārajanam ity api

रङ्ग-वङ्गे अथ पिचुस् तूलो

ऽथ कमलोत्तरम् ।१०६ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Färberdistel - Carthamus tinctorius L. 1753:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Safflower ; carthamus."

कमलोत्तर - kamalottara n.: dem Lotus überlegen, Färberdistel

Abb.: कमलोत्तरम् । Carthamus tinctorius L. 1753 - Färberdistel -

Dyer's Saffron, USA

[Bildquelle: Shihmei Barger 舒詩玫. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/beautifulcataya/3762455663/. -- Zugriff am

2011-10-03. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Zum Vergleich: Lotus - Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn 1788, Hyderabad

- హైదరాబాద్,

Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

कुसुम्भ - kusumbha n.: Färberdistel, Krug

Abb.: कुसुम्भम् । Carthamus tinctorius L. 1753 - Färberdistel -

Dyer's Saffron, Japan

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

वह्निशिख - vahniśikha n.: Feuerflamme

Abb.: वह्निशिखम् । Carthamus tinctorius L. 1753 - Färberdistel -

Dyer's Saffron, Deutschland

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

महारजन - mahārajana n.: große Farbe

Abb.: महारजनम् । Carthamus tinctorius L. 1753 - Färberdistel - Dyer's

Saffron, Blütenblätter, Japan

[Bildquelle: 松岡明芳 / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"CARTHAMUS TINCTORIUS. Safflower. "The safflower is grown very abundantly all over India, Burma, and China, and is very largely used in dyeing. The plant is propagated by seed sown in drills at 1½ feet distance from each other. The young plants appear in about a month, and after the second month are hoed and thinned, each plant being left a foot from the other. The richer the land, the larger the proportion of colouring matter afforded by the flower. On the opening of the flowerets, they are rapidly gathered without being allowed to expand fully. They are then dried in the shade with great care. The produce of Paterghauta and Belispore is considered, in the London market, as the best that is exported from India. The Dacca safflower ranks next to that of China, which is reputed to be of a superior quality. Safflower is widely grown on the banks of the Irawadi and Salwin. Its flowers furnish the best yellow dye in the country, and, mixed with other ingredients, they are used to dye red, and to give a variety of tints, and in dyeing pink and scarlet. This plant yields six or seven distinct shades of red, the palest pink or piyazi gulabi (pink), gulabi surkh (rose colour), kulfi or gul-i-shaftalu (deep-red). In combination with harsinghar flowers (Nyctanthes arbor-tristis), it yields soneri or golden orange, narangi, deep orange, and sharbati, salmon-colour ; and with turmeric (haldi, zard chob), it gives a splendid scarlet, gul-i-anar, and other tints ; again, if combined with indigo, Prussian blue, etc., a series of beautiful purples, known as lajwardi, uda, nafarmani, soeani, kasni (a delicate mauve), falsai, kokai, and the deep-purple baingni. All these tints are more or less beautiful, but scarcely one of them will stand washing.

The yellow principle is worthless as a dye. It is soluble in water, is removed by washing, and thrown away as the first step in the preparation of the valuable red product. The red dye is an acid resinous substance of superb colour, insoluble in water and in acid solutions, little soluble in alcohol, and not at all in ether. It is dissolved freely by aqueous alkaline solutions, which it neutralizes. Its salts (carthamates) are crystalizable, and quite colourless ; acids precipitate the carthamic acids from solutions of these salts. To obtain it on a large scale, after the separation of the yellow matter, the dried flowers are treated by a solution of carbonate of soda, and lemon juice added ; the carthamic acid precipitate is collected by subsidence, washed, and carefully dried at a gentle heat. The most lovely tints are imparted by this dye to silk and cotton ; rouge is a mixture of the dry carthamic acid and finely powdered talc. The pink saucers used for giving a flesh tint to silk are prepared from this dye, with a small portion of soda. 8 oz. of the prepared petals and 2 oz. carbonate of soda are acted on by 2 gallons of water. 4 lbs. of prepared chalk are added, and the colour precipitated upon this by citric or tartaric acid. The Chinese card-rouge is a carthamate of soda, colourless when rubbed on, but by the salt being decomposed by the acetic acid secreted by the skin itself, the carthamic acid separates in the most perfect rosy tint which can be imagined. The seeds yield abundance of fixed oil, which is used as an external application in paralytic affections, and for bad ulcers ; and small seeds are reckoned by the Vytians amongst their laxative medicines."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 591.]

"CARTHAMUS TINCTORIUS, Linn. Fig.—Reich. Ic. Fl. Germ. t. 746; Bot. Reg. t. 170; Rumph. Amb. V. 79.

Safflower, Parrot seed

Hab.—Cultivated throughout India. (C. oxycantha, Bieb., is perhaps the wild form of this plant.) The flowers and seeds.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—This plant is the Kusumbha of Sanskrit writers, who describe the seeds as purgative, and mention a medicated oil which is prepared from the plant for external application in rheumatism and paralysis. It is the κνικος of the Greeks, who used the leaves like rennet to curdle milk in making cheese. Pliny (21, 53,) calls it Cnecos. Mahometan writers enumerate a great many diseases in which the seeds may be used as a laxative ; they consider them to have the power of removing phlegmatic and adust humours from the system.

The author of the Makhzan states that Kurtum, Hab-el-asfar, and Bazr-el-ahris are the Arabic names for the seeds, and Khasakdanah and Tukm-i-kafshah the Persian. He also says that in Ghilan they are called Tukm-i-lajrah or Tukm-i-kazirah, in Syria Kashni, and in Turkey Kantawaras, and that the Greeks call them Atraktus (ατρακτυλις), and Dioscorides Knikus (κνικος). Ainslie has the following notice of the plant :— "A fixed oil is prepared from it which the Vytians use as an external application in rheumatic pains and paralytic affections also for bad ulcers ; the small seeds are reckoned amongst their laxative medicines, for which purpose I see they are also used in Jamaica (the kernels beat into an emulsion with honeyed water). Barham tells us that a drachm of the dried flowers taken cures the jaundice." {Mat. Ind. ii., 364.)

The seeds are known in England as Parrot seed. Under the name of safflower the flowers form an important export article to Europe; they contain two colouring matters, yellow and red, the latter is the most valuable. In silk dyeing it affords various shades of pink, rose, crimson and scarlet. Rouge is also made from it. According to Calvert (Dyeing and Calico Printing, Bd. 1878,) though the safflower has lost much of its value as a dye since the discovery of the aniline colours, it is still used extensively in Lancashire for the production of peculiar shades of pink of the Eastern markets. It is also used for dyeing red tape, and there is no more striking instance of "red-tapeism," than the love which is shown for this particular colour by the users of that article. Much cheaper pinks can be produced from aniline, but notwithstanding the attempts which have many times been made to introduce them, they have failed in every instance, because the exact shade has not been obtained."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 308f..]

"CARTHAMUS TINCTORIUS, Linn. Fig.—Reich. Ic. Fl. Germ. t. 746; Bot. Reg. t. 170; Rumph. Amb. V. 79.