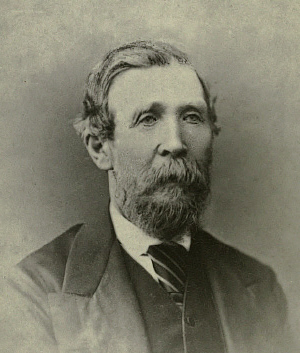

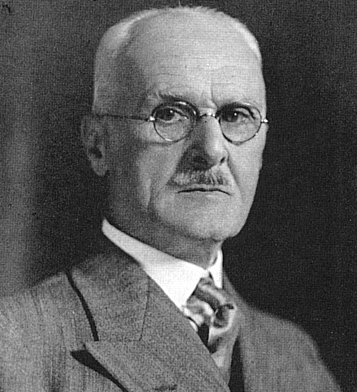

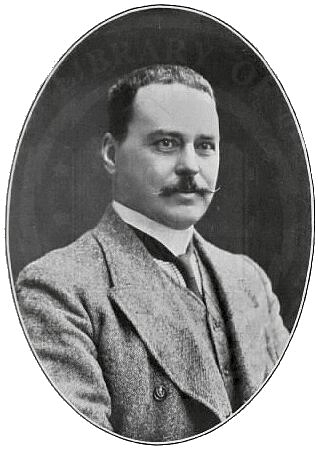

| "Allan Octavian Hume (June

6, 1829 -

July 31,

1912) son of

Joseph Hume was a

civil servant in British governed India, and a political reformer. He

was, along with Sir William Wedderburn, a founder of the

Indian National Congress. He has been called the father of Indian

Ornithology by some and, by those who found him dogmatic as the

Pope of Indian ornithology.[1] Life and career

Hume was born at St

Mary Cray, Kent,[2]

the son of

Joseph Hume, the Radical MP. He was educated at

Haileybury Training College and then

University College Hospital, studying medicine

and surgery.

In 1849 he sailed to India and the

following year joined the Bengal Civil Service at

Etawah (इतावाह) in

the North-Western Provinces, in what is now

Uttar Pradesh. He soon rose to become District Officer, introducing free

primary education and creating a local vernacular newspaper, Lokmitra

(The People's Friend). He married Mary Anne Grindall in 1853.[3]

He took up the cause of education and founded scholarships for higher

education. He wrote in 1859:[3]

a free and civilized government must look for its stability and

permanence to the enlightenment of the people and their moral and

intellectual capacity to appreciate its blessings.

In 1860 Hume was made

Companion of the Bath for his services during the rebellion or

Indian rebellion of 1857.

The system of departmental examinations introduced soon after (Hume

joined the civil services) enabled Hume so to outdistance his

seniors that when the Mutiny broke out he was officiating Collector

of Etawah, which lies between Agra and Cawnpur. Rebel troops were

constantly passing through the district, and for a time it was

necessary to abandon headquarters ; but both before and after the

removal of the women and children to Agra, Hume acted with vigour

and judgment. The steadfast loyalty of many native officials and

landowners, and the people generally, was largely due to his

influence, and enabled him to raise a local brigade of horse. In a

daring attack on a body of rebels at Jaswantnagar he carried away

the wounded joint magistrate, Mr. Clearmont Daniel, under a heavy

fire, and many months later he engaged in a desperate action against

Firoz Shah and his Oudh freebooters at Hurchandpur. Company rule had

come to an end before the ravines of the Jumna and the Chambul in

the district had been cleared of fugitive rebels. Hume richly

merited the C.B. (Civil division) awarded him in 1860. He remained

in charge of the district for ten years or so and did good work.

—Obituary The Times of August 1st, 1912

In 1863 he moved for separate schools for Juvenile delinquents rathern

than imprisonment. His efforts led to a Juvenile Reformatory not far from Etawah

(इतावाह). He

also started free schools in Etawah and by 1857 he established 181 schools

with 5186 students including two girls. In 1867 he became Commissioner of

Customs for the North West Province, and in 1870 he became attached to the

central government as Director-General of Agriculture. In 1879 he returned

to provincial government at Allahabad.[3]

Hume's appointment, in 1867, to be Commissioner of Customs in Upper

India gave him charge of the huge physical barrier[4]which

stretched across the country for 2,500 miles from Attock, on the

Indus, to the confines of the Madras Presidency. He carried out the

first negotiations with Rajputana Chiefs, leading to the abolition

of this barrier, and Lord Mayo rewarded him with the Secretaryship

to Government in the Home, and afterwards, from 1871, in the Revenue

and Agricultural Departments. Leaving Simla, he returned to the

North-West Provinces in October, 1879, as a member of the Board of

Revenue, and retired from the service in 1882.[5]

He was against the revenue earned through liquor traffic and described it

as "The wages of sin". With his progressive ideas about social reform, he

advocated women's education, was against infanticide and enforced widowhood.

Hume laid out in Etawah a neatly gridded commercial district that is now

known as Humeganj but often pronounced Homeganj. The high school that

he helped build with his own money is still in operation, now as a junior

college, and it has a floor plan resembling the letter H. This, according to

some is an indication of Hume's imperial ego, although the form can easily

be missed.

Hume proposed to develop fuelwood plantations "in every village in the

drier portions of the country" and thereby provide a substitute heating and

cooking fuel so that manure could be returned to the land. Such plantations,

he wrote, were "a thing that is entirely in accord with the traditions of

the country-a thing that the people would understand, appreciate, and, with

a little judicious pressure, cooperate in."

He also took note of rural indebtedness, chiefly caused by the use of

land as security, a practice the British themselves had introduced. Hume

denounced it as another of "the cruel blunders into which our narrow-minded,

though wholly benevolent, desire to reproduce England in India has led us."

Hume also wanted government-run banks, at least until cooperative banks

could be established.[3]

He was very outspoken and never feared to criticise when he thought the

Government was in the wrong. In 1861, he objected to the concentration of

police and judicial functions in the hands of the police superintendent. He

criticized the administration of

Lord Lytton (before 1879) which according to him cared little for the

welfare and aspiration of the people of India. Lord Lytton's foreign policy

according to him had led to the waste of "millions and millions of Indian

money".[3]

In 1879 the Government made their disapproval of his criticism and

frankness known and summarily removed him from the Secretariat. The

Englishman in an article dated 27 June 1879,

commenting on the event stated, "There is no security or safety now for

officers in Government employment."

Hume retired from the civil service in 1882. In 1883 he wrote an open

letter to the graduates of

Calcutta University, calling upon them to form their own national

political movement. This led in 1885 to the first session of the

Indian National Congress held in Bombay.

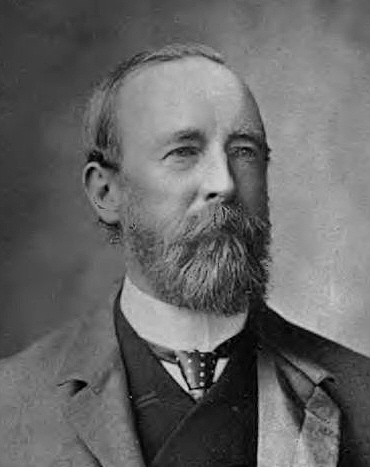

Hume served as its General Secretary until 1908. Along with Sir William

Wedderburn (1838-1918) they made it possible for Indians to organize

themselves in preparation of self government.

Mary Anne Grindall died in 1890, and their only daughter was the widow of

Mr. Ross Scott who was sometime Judicial Commissioner of Oudh (अवध). Hume left

India in 1894 and settled at The Chalet, 4, Kingswood Road,

Upper Norwood in

London. He

died at the age of eighty-three on July 31st, 1912. His ashes are buried in

Brookwood Cemetery.

In 1973, the Indian postal department released a commemorative stamp.[6]

TheosophyHume wanted to become a chela (student) of the Tibetan spiritual

gurus. During the few years of his connection with the

Theosophical Society Hume wrote three articles on Fragments of Occult

Truth under the pseudonym "H. X." published in The Theosophist.

These were written in response to questions from Mr. Terry, an Australian

Theosophist. He also privately printed several Theosophical pamphlets titled

Hints on Esoteric Theosophy. The later numbers of the Fragments, in

answer to the same enquirer, were written by

A.P. Sinnett and signed by him, as authorized by Mahatma K. H., A

Lay-Chela.

A long story, about Hume and his wife appears in A.P. Sinnett's book

Occult World, and the synopsis was published in a local paper of India.

The story relates how at a dinner party,

Madame Blavatsky asked Mrs Hume if there was anything she wanted. She

replied that there was a brooch, her mother had given her, that had gone out

of her possession some time ago. Blavatsky said she would try to recover it

through occult means. After some interlude, later that evening, the brooch

was found in a garden, where the party was directed by Blavatsky.

Madame Blavatsky was a regular visitor at Hume's Rothney castle at Simla and an

account of her visit may be found in Simla, Past and Present by

Edward John Buck (who succeeded Mr. Hume in charge of the Agricultural

Department). Later, Hume privately expressed grave doubts on certain powers

attributed to Madame Blavatsky and due to this, soon fell out of favour with

the Theosophists.

Hume lost all interest in theosophy when he got involved with the

creation of the Indian National Congress.

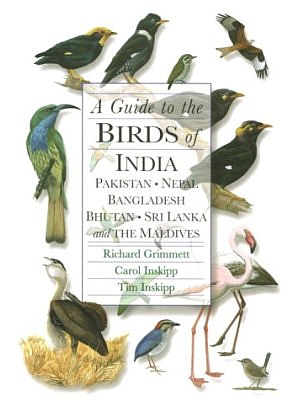

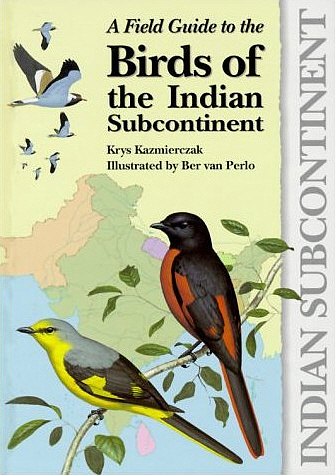

Contribution to ornithology

From early days, Hume had a special interest in science. Science, he

wrote

...teaches men to take an interest in things outside and beyond… The

gratification of the animal instinct and the sordid and selfish cares of

worldly advancement; it teaches a love of truth for its own sake and

leads to a purely disinterested exercise of intellectual faculties

and of natural history he wrote in 1867:[3]

... alike to young and old, the study of Natural History in all its

branches offers, next to religion, the most powerful safeguard against

those worldly temptations to which all ages are exposed. There is no

department of natural science the faithful study of which does not leave

us with juster and loftier views of the greatness, goodness, and wisdom

of the Creator, that does not leave us less selfish and less worldly,

less spiritually choked up with those devil’s thorns, the love of

dissipation, wealth, power, and place, that does not, in a word, leave

us wiser, better and more useful to our fellow-men.

During his career in Etawah, he built a personal collection of bird

specimens, however it was destroyed during the 1857 mutiny. Subsequently he

started afresh with a systematic plan to survey and document the birds of

the Indian Subcontinent and in the process he accumulated the largest

collection of Asiatic birds in the world, which he housed in a museum and

library at his home in Rothney Castle on Jakko Hill, Simla.

Rothney castle originally belonged to P. Mitchell, C.I.E and after Hume

bought it, he tried to convert the house into a veritable palace, which he

expected would be bought by the Government as a Viceregal residence in view

of the fact that the Governor-General then occupied Peterhoff, which

was too small for Viceregal entertainments. Hume spent over two hundred

thousand pounds on the grounds and buildings. He added enormous reception

rooms suitable for large dinner parties and balls, as well as a magnificent

conservatory and spacious hall with walls displaying his superb collection

of Indian horns. He hired a European gardener, and made the grounds and

conservatory a perpetual horticultural exhibition, to which he courteously

admitted all visitors.[3]

Rothney Castle could only be reached by a troublesome climb, and was

never purchased by the British Government and he himself did not use the

larger rooms except for one that he converted into a museum for his

wonderful collection of birds, and for occasional dances.[3]

He made many expeditions to collect birds both on health leaves and as

and where his work took him. He was Collector and Magistrate of Etawah from

1856 to 1867 during which time he studied the birds of that area. He later

became Commissioner of Inland Customs which made him responsible for the

control of 2500 miles of coast from near Peshawar in the northwest to

Cuttack on the Bay of Bengal. He travelled on horseback and camel in areas

of Rajasthan and negotiated treaties with various local maharajas to control

the export of natural resources such as salt. During these travels he made a

number of notes on various bird species:

The nests are placed indifferently on all kinds of trees (I have

notes of finding them on mango, plum, orange, tamarind, toon, etc.),

never at any great elevation from the ground, and usually in small trees,

be the kind chosen what it may. Sometimes a high hedgerow, such as our

great

Customs hedge, is chosen, and occasionally a solitary caper or

stunted acacia-bush.

– On the nesting of the Bay-backed

Shrike (Lanius vittatus) in The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds.

His expedition to the Indus area was one of the largest and it started in

late November 1871 and continued until the end of February 1872. In March

1873, he visited the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. In

1875 he visited the Laccadive Islands. And in 1881 he made his last

ornithological expedition to Manipur. This was made on special leave

following his demotion from the Central Government to a junior position on

the Board of Revenue of the North Western Provinces.

He used this vast bird collection to produce a massive publication on all

the birds of India. Unfortunately this work was lost in 1885 when all Hume's

manuscripts were sold by a servant as waste paper. Hume's interest in

ornithology reduced due to this theft as well as a landslip caused by heavy

rains in Simla which damaged his personal museum and specimens. He wrote to

the

British Museum wishing to donate his collection on certain conditions.

One of the conditions was that the collection was to be examined by Dr.

R. Bowdler Sharpe and personally packed by him, apart from raising Dr.

Sharpe's rank and salary due to the additional burden on his work caused by

his collection. The British Museum was unable to heed to his conditions. It

was only after the destruction of nearly 20000 specimens, that alarm bells

were raised by Dr. Sharpe and the Museum authorities let him visit India to

supervise the transfer of the specimens to the British Museum.[3]

Sharpe provides the following account of Hume's impressive private

ornithological museum:[3]

I arrived at Rothney Castle about 10 am on the 19th of May, and was

warmly welcomed by Mr Hume, who lives in a most picturesque situation

high up on Jakko…From my bedroom window, I had a fine view of the snowy

range. Although somewhat tired by my jolt in the Tonga from Solun, I

gladly accompanied Mr. Hume at once into the museum…I had heard so much

from my friends, who knew the collection intimately,…that I was not so

much surprised when at last I stood in the celebrated museum and gazed

at the dozens upon dozens of tin cases which filled the room. Before the

landslip occurred, which carried away one end of the museum, It must

have been an admirably arranged building, quite three times as large as

our meeting-room at the Zoological Society, and…much more lofty.

Throughout this large room went three rows of table cases with glass

tops, in which were arranged a series of the birds of India sufficient

for the identification of each species, while underneath these table-

cases where enormous cabinets made of tin, with trays inside, containing

species of birds in the table cases above. All of the rooms were racks

reaching up to the ceiling, and containing immense cases full of birds…

On the western side of the museum was the library, reached by a descent

of three steps, a cheerful room, furnished with large tables, and

containing besides the egg-cabinets, a well-chosen set of

working-volumes. One ceases to wonder at the amount of work its owner

got through when the excellent plan of his museum is considered. In a

few minutes an immense series of specimens could be spread out on the

tables, while all the books were at hand for immediate reference…After

explaining to me the contents of the museum, we went below into the

basement, which consisted of eight great rooms, six of them full, from

floor to ceiling, of cases of birds, while at the back of the house two

large verandahs were piled high with cases full of large birds, such as

Pelicans, Cranes, Vultures, &c. An inspection of a great cabinet

containing a further series of about 5000 eggs completed our survey. Mr.

Hume gave me the keys of the museum, and I was free to commence my task

at once.

Sharpe also noted:[3]

Mr. Hume was a naturalist of no ordinary calibre, and this great

collection will remain a monument of his genius and energy of its

founder long after he who formed it has passed away...Such a private

collection as Mr. Hume's is not likely to be formed again; for it is

doubtful if such a combination of genius for organisation with energy

for the completion of so great a scheme, and the scientific knowledge

requisite for its proper development will again be combined in a single

individual.

The Hume collection as it went to the British museum in 1884 consisted of

82,000 specimens of which 75,577 were finally placed in the Museum. A

break-up of that collection is as follows (old names retained).[3]

- 2830 Birds of Prey (Accipitriformes)… 8 types

- 1155 Owls (Strigiformes)…9 types

- 2819 Crows, Jays, Orioles etc…5 types

- 4493 Cuckoo-shrikes and Flycatchers… 21 types

- 4670 Thrushes and Warblers…28 types

- 3100 Bulbuls and wrens, Dippers, etc…16 types

- 7304 Timaliine birds…30 types

- 2119 Tits and Shrikes…9 types

- 1789 Sun-birds (Nectarinidae) and White-eyes (Zosteropidae)…8 types

- 3724 Swallows (Hirundiniidae), Wagtails and Pipits (Motacillidae)…8

types

- 2375 Finches (Fringillidae)…8 types

- 3766 Starlings (Sturnidae), Weaver-birds (Ploceidae), and larks (Alaudidae)…22

types

- 807 Ant-thrushes (Pittidae), Broadbills (Eurylaimidae)…4 types

- 1110 Hoopoes (Upupae), Swifts (Cypseli), Nightjars (Caprimulgidae)

and Frogmouths (Podargidae)…8 types

- 2277 Picidae, Hornbills (Bucerotes), Bee-eaters (Meropes),

Kingfishers (Halcyones), Rollers(Coracidae), Trogons (Trogones)…11 types

- 2339 Woodpeckers (Pici)…3 types

- 2417 Honey-guides (Indicatores), Barbets (Capiformes), and Cuckoos

(Coccyges)…8 types

- 813 Parrots (Psittaciformes)…3 types

- 1615 Pigeons (Columbiformes)…5 types

- 2120 Sand-grouse (Pterocletes), Game-birds and

Megapodes(Galliformes)…8 types

- 882 Rails (Ralliformes), Cranes (Gruiformes), Bustards (Otides)…6

types

- 1089 Ibises (Ibididae), Herons (Ardeidae), Pelicans and Cormorants

(Steganopodes), Grebes (Podicipediformes)…7 types

- 761 Geese and Ducks (Anseriformes)…2 types

- 15965 Eggs

The Hume Collection contained 258

types.

The egg collection was made up of carefully authenticated contributions

from knowledgeable contacts and on the authenticity and importance of the

collection, E. W. Oates wrote in the 1901 Catalogue of the collection of

birds' eggs in the British Museum (Volume 1):

The Hume Collection consists almost entirely of the eggs of Indian

birds. Mr. Hume seldom or never purchased a specimen, and the large

collection brought together by him in the course of many years was the

result of the willing co-operation of numerous friends resident in India

and Burma. Every specimen in the collection may be said to have been

properly authenticated by a competent naturalist; and the history of

most of the clutches has been carefully recorded in Mr. Hume's 'Nests

and Eggs of Indian Birds', of which two editions have been published.

Species described

Some of the species that were first described or discovered by Hume are

as follows. The numbers are references to species as given in S. D. Ripley's

synopsis[7]

and the old names are retained. Many of these names are no longer valid.[3]

- 12 Persian Shearwater (Procellaria lherminieri persica) (Puffinus

persicus)

- 17 Short-tailed Tropic-bird (Phaethon

aethereus indicus)

- 33 Great Whitebellied Heron (Ardea

insignis)

- 96 Grey, Andaman or Oceanic Teal (Anas

gibberifrons albogularis)

- 140 Burmese Shikra (Accipiter

badius poliopsis)

- 148 Indian Sparrow-hawk (Accipiter nisus melaschistos)

- 180,183 Indian Griffon Vulture (Gyps fulvus fulvescens)

- 181 Himalayan Griffon Vulture (Gyps

himalayensis)

- 200 Andaman Pale Serpent Eagle (Spilornis

cheela davisoni)

- 201 Nicobar Crested Serpent Eagle (Spilornis cheela minimus)

(=Spilornis

minimus)

- 235 Northern Chukor (Alectoris

chukar pallescens)

- 239 Assam Black Partridge (Francolinus francolinus

melanonotus)

- 263 Northern Painted Bush Quail (Perdicula

erythrorhyncha blewitti)

- 265 Manipur Bush Quail (Perdicula manipurensis manipurensis)

- 273 Redbreasted Hill Partridge (Arborophila

mandellii)

- 308 Mrs. Hume's Barredback Pheasant (Syrmaticus

humiae humiae)

- 330 Andaman Bluebreasted Banded Rail (Rallus striatus

obscurior)(=

Gallirallus striatus)

- 466 Roseate Tern (Sterna dougalli korustes)

- 476 Blackshafted Ternlet (Sterna saundersi) (=Sterna

albifrons)

- 516 Blue Rock Pigeon (Columba livia neglecta)

- 525 Andaman Wood Pigeon (Columba

palumboides)

- 555 Andaman Redcheeked Parakeet (Psittacula longicauda

tytleri)

- 563 Eastern Slatyheaded Parakeet (Psittacula finschii)

- 601 Bangladesh Crow-pheasant (Centropus sinensis intermedius)

- 607 Andaman Barn Owl (Tyto

alba deroepstorffi)

- 610 Ceylon Bay Owl (Phodilus

badius assimilis)

- 611 Western Spotted Scops Owl (Otus

spilocephalus huttoni)

- 613 Andaman Scops Owl (Otus

balli)

- 614 Pallid Scops Owl (Otus

brucei)

- 618b Nicobar Scops Owl (Otus scops nicobaricus) (=Otus

alius)

- 619 Punjab Collared Scops Owl (Otus

bakkamoena plumipes)

- 626a Himalayan Horned or Eagle Owl (Bubo bubo hemachalana)

- 643 Burmese Brown Hawk-owl (Ninox scutulata burmanica)

- 645 Hume's Brown Hawk-owl (Ninox scutulata obscura)

- 653 Forest Spotted Owlet (Athene blewitti) (=Heteroglaux

blewitti)

- 654

Hume's Owl (Strix

butleri)

- 669 Bourdillon's or Kerala Great Eared Nightjar (Eurostopodis

macrotis bourdilloni)

- 673 Hume's European Nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus unwini)

- 679 Andaman Longtailed Nightjar (Caprimulgus macrurus

andamanicus)

- 684 Hume's Swiftlet (Collocalia brevirostris innominata)

- 684a Black-nest Swiftlet (Collocalia maxima maxima)

- 686 Andaman Greyrumped or White-nest Swiftlet (Collocalia

fuciphaga inexpectata)

- 691 Brown-throated Spinetail Swift (Chaetura gigantea indica)

- 732 Nicobar Storkbilled Kingfisher ([Pelargopsis

capensis|Pelargopsis capensis intermedia]])

- 738 Andaman Whitebreasted Kingfisher (Halcyon

smyrnensis saturatior)

- 773

Narcondam Hornbill (Rhyticeros undulatus narcondami)

- 793 Pakistan Orangerumped Honeyguide (Indicator

xanthonotus radcliffi)

- 841 Manipur Crimsonbreasted Pied Woodpecker (Picoides

cathpharius pyrrhothorax)

- 887 Karakoram or Hume's Short-toed Lark (Calandrella

acutirostris acutirostris)

- 889 Indus Sand Lark (Calandrella raytal adamsi)

- 898 Baluchistan Crested Lark (Galerida

cristata magna)

- 915 Pale Crag Martin (Hirundo obsoleta pallida)

- 974 Large Andaman Drongo (Dicrurus andamanensis dicruriformis)

- 986 Andaman Glossy Stare (Aplonis panayensis tytleri)

- 998 Hume's or Afghan Starling (Sturnus vulgaris nobilior)

- 1000 Sind Starling (Sturnus vulgaris minor)

- 1041 Hume's Ground Chough (Podoces humilis)

- 1113 Andaman Blackheaded Bulbul (Pycnonotus atriceps

fuscoflavescens)

- 1165 Mishmi Brown Babbler (Pellorneum albiventre ignotum)

- 1172 Mount Abu Scimitar Babbler (Pomatorhinus schisticeps

obscurus)

- 1190 Manipur Longbilled Scimitar Babbler (Pomatorhinus

ochraceiceps austeni)

- 1225 Kerala Blackheaded Babbler (Rhopocichla atriceps

bourdilloni)

- 1234 Hume's Babbler (Chrysomma altirostre griseogularis)

- 1289 Western Variegated Laughing Thrush (Garrulax variegatus

similis)

- 1301 Khasi Hills Greysided Laughing Thrush (Garrulax

caerulatus subcaerulatus)

- 1330 Manipur Redheaded Laughing Thrush (Garrulax

erythrocephalus erythrolaema)

- 1363 Sikkim Whitebrowed Yuhina (Yuhina castaniceps rufigenis)

- 1389 Bombay Quaker Babbler (Alcippe

poioicephala brucei)

- 1424 Eastern Slaty Blue Flycatcher (Muscicapa leucomelanura

minuta)

- 1434 Whitetailed Blue Flycatcher (Muscicapa concreta cyanea)

- 1453 Eastern Whitebrowed Fantail Flycatcher (Rhipidura

aureola burmanica)

- 1484 Hume's Bush Warbler (Cettia acanthizoides brunnescens)

- 1510 Northwestern Plain Wren-Warbler (Prinia subflava

terricolor)

- 1520 Northwestern Jungle Wren-Warbler (Prinia sylvatica

insignia)

- 1526 Sind Brown Hill Warbler (Prinia criniger striatula)

- 1540 Blacknecked Tailor Bird (Orthotomus atrogularis nitidus)

- 1569 Small Whitethroat (Sylvia curruca minula)

- 1570 Hume's Lesser Whitethroat (Sylvia curruca althaea)

- 1577 Plain Leaf Warbler (Phylloscopus neglectus)

- 1664 Andaman Magpie-Robin (Copsychus saularis andamanensis)

- 1707 Redtailed Chat (Oenanthe xanthoprymna kingi)

- 1714 Hume's Chat (Oenanthe alboniger)

- 1730 Burmese Whistling Thrush (Myiophonus caeruleus eugenei)

- 1820 Manipur Redheaded Tit (Aegithalos concinnus manipurensis)

- 1850 Manipur Tree Creeper (Certhia manipurensis)

- 1903 Andaman Flowerpecker (Dicaeum concolor virescens)

- 1913 Andaman Olivebacked Sunbird (Nectarinia jugularis

andamanica)

- 1918 Assam Purple Sunbird (Nectarinia asiatica intermedia)

- 1129a Nicobar Yellowbacked Sunbird (Aethopyga siparaja

nicobarica)

- 1955 Blanford's Snow Finch (Montifringilla blanfordi

blanfordi)

- 1960 Finn's Baya (Ploceus megarhynchus megarhynchus)

- 1970 Nicobar Whitebacked Munia (Lonchura striata semistriata)

- 1971-2 Jerdon's Rufousbellied Munia (Lonchura kelaarti

jerdoni)

- 1993 Tibetan Siskin (Carduelis thibetana)

- 1995 Stoliczka's Twite (Acanthis flavirostris montanella)

An additional species, the Large-billed Reed-Warbler

Acrocephalus orinus was known from just one specimen collected by

him in 1869.[8]

The status of the species was contested for long and DNA comparisons with

similar species in 2002 suggested that it was a valid species.[9]

It was only in 2006 that the species was seen again in Thailand.

Hume made several expeditions solely to study ornithology and in March

1873 he made one to the Andaman, Nicobar and other islands in the Bay of

Bengal along with geologists Dr.

Ferdinand Stoliczka and Dr. Dougall of the Geological Survey of India

and

James Wood-Mason of the Indian Museum in Calcutta.[3]

Hume employed

William Ruxton Davison as a curator of his personal bird collection and

also sent him out on collection trips to various parts of India, when he was

held up with official responsibilities.[3]

Stray Feathers

Hume started the quarterly journal Stray Feathers - A journal of

ornithology for India and dependencies in 1872. He used the journal to

publish descriptions of his new discoveries, such as Hume's Owl, Hume's

Wheatear and Hume's Whitethroat. He wrote extensively on his own observation

as well as critical reviews of all the ornithological works of the time and

earned himself the nickname of Pope of Indian ornithology.

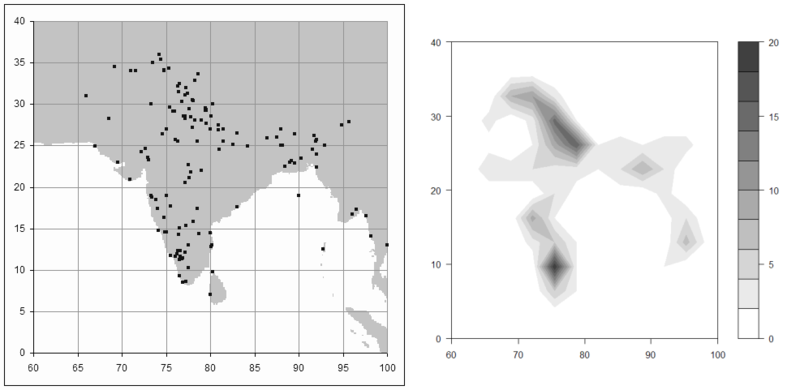

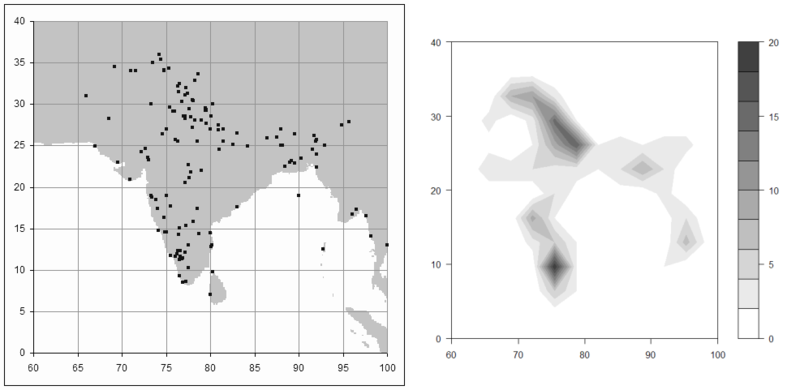

Hume's network of correspondents

Hume built up a network of ornithologists reporting from various parts of

India. A list based on the correspondents mentioned in Stray Feathers and in

his Game Birds is as follows. This is probably only a small fraction of the

subscribers of Stray Feathers. This huge network made it possible for Hume

to cover a much larger geographic region in his ornithological work.

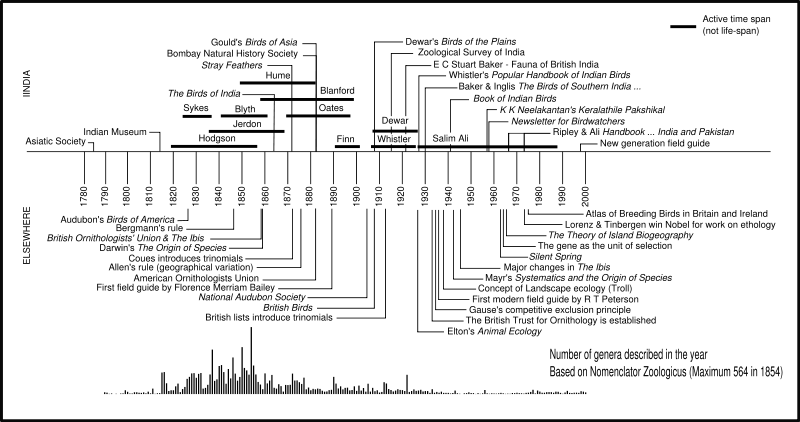

Distribution and density of Hume's correspondents across India

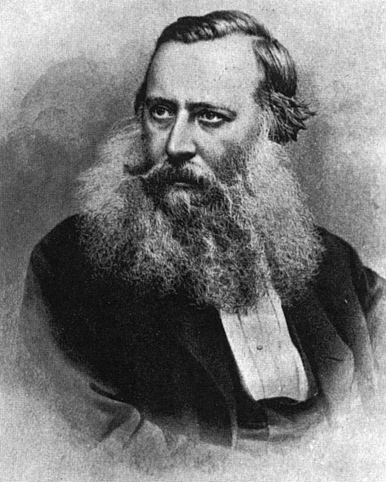

During the time of Hume, Blyth was considered the father of Indian

ornithology. Hume's achievement which made use of a large network of

correspondents was recognized even during his time:

Mr. Blyth, who is rightly called the Father of Indian Ornithology,

"was by far the most important contributor to our knowledge of the

Birds of India." Seated, as the head of the Asiatic Society's

Museum, he, by intercourse and through correspondents, not only

formed a large collection for the Society, but also enriched the

pages of the Society's Journal with the results of his study, and

thus did more for the extension of the study of the Avifauna of

India than all previous writers. There can be no work on Indian

Ornithology without reference to his voluminous contributions. The

most recent authority, however, is Mr. Allen O. Hume, C.B., who,

like Blyth and Jerdon, got around him numerous workers, and did so

much for Ornithology, that without his Journal Stray Feathers,

no accurate knowledge could be gained of the distribution of Indian

birds. His large museum, so liberally made over to the nation, is

ample evidence of his zeal and the purpose to which he worked. Ever

saddled with his official work, he yet found time for carrying out a

most noble object. His Nests and Eggs, Scrap Book and

numerous articles on birds of various parts of India, the Andamans

and the Malay Peninsula, are standing monuments of his fame

throughout the length and breadth of the civilized world. His

writings and the field notes of his curator, contributors and

collectors are the pith of every book on Indian Birds, and his vast

collection is the ground upon which all Indian Naturalists must work.

Though differing from him on some points, yet the palm is his as an

authority above the rest in regard to the Ornis of India. Amongst

the hundred and one contributors to the Science in the pages of

Stray Feathers, there are some who may be ranked as specialists

in this department, and their labors need a record. These are Mr. W.

T. Blanford, late of the Geological Survey, an ever watchful and

zealous Naturalist of some eminence. Mr. Theobald, also of the

Geological Survey, Mr. Ball of the same Department, and Mr. W. E.

Brooks. All these worked in Northern India, while for work in the

Western portion must stand the names of Major Butler, of the 66th

Regiment, Mr. W. F. Sinclair, Collector of Colaba, Mr. G. Vidal, the

Collector of Bombay, Mr. J. Davidson, Collector of Khandeish, and

Mr. Fairbank, each one having respectively worked the Avifauna of

Sind, the Concan, the Deccan and Khandeish.

Many of Hume's correspondents were eminent naturalists and sportsmen of

the time.

-

Leith Adams, Kashmir

- Lieut.

H. E. Barnes, Afghanistan, Chaman, Rajpootana

- Captain

R. C. Beavan, Maunbhoom District, Shimla, Mount Tongloo (1862)

- Colonel

John Biddulph, Gilgit

- Major

C. T. Bingham, Thoungyeen Valley, Burma, Tenasserim, Moulmein,

Allahabad

- Mr.

W. Blanford

- Mr.

Edward Blyth

- Mr.

W. Edwin Brooks

- Sir Edward Charles Buck, Gowra, Hatu, near Narkanda (in Himachal

Pradesh), Narkanda, (about 30 miles north of Shimla)

- Captain Boughey Burgess, Ahmednagar (?-1855)[11]

- Captain and then Colonel

E. A. Butler, Belgaum (1880), Karachi, Deesa, Abu

- Mr.

James Davidson, Satara and Sholapur districts,Khandeish,

Kondabhari Ghat

- Colonel

Godwin-Austen, Shillong, Umian valley, Assam

- Mr.

Brian Hodgson, Nepal

-

Duncan Charles Home, 'Hero of the Kashmir Gate' (Bulandshahr,

Aligarh)

- Dr.

T. C. Jerdon, Tellicherry

- Colonel

C. H. T. Marshall, Bhawulpoor, Murree

- Colonel

G. F. L. Marshall, Nainital, Bhim tal

- Mr.

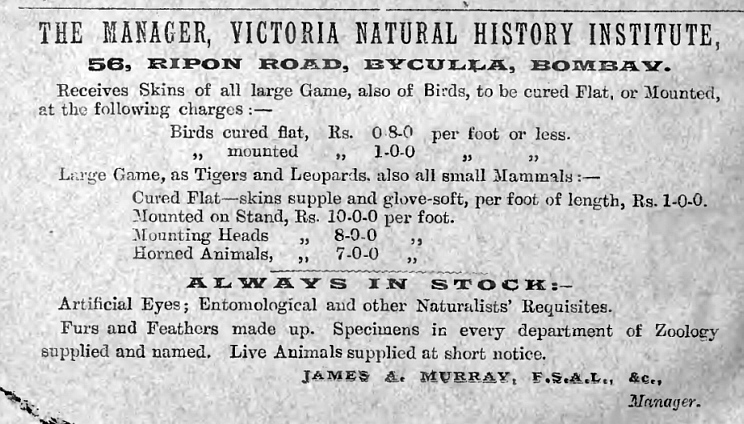

James A. Murray, Karachi Museum

- Mr.

Eugene Oates, Thayetmo, Tounghoo, Pegu

- Captain

Robert George Wardlaw Ramsay, Afghanistan, Karenee hills

- Mr.

G. P. Sanderson (Chittagong)

- Dr.

Ferdinand Stoliczka

- Mr.

Robert Swinhoe, Hongkong

- Mr.

Charles Swinhoe, S. Afghanistan

- Colonel

Samuel Tickell

- Colonel Tytler, Dacca, 1852

- Mr.

Valentine Ball, Rajmahal hills, Subanrika (Subansiri)

-

Richard Lydekker

He also corresponded with ornithologists outside India including

R. Bowdler-Sharpe, the

Marquis of Tweeddale,

Pere David,

Dresser,

Benedykt Dybowski,

John Henry Gurney, J.H.Gurney, Jr. ,Johann

Friedrich Naumann,

Severtzov, Dr.

Middendorff.

My Scrap book: or rough notes on Indian Oology and

ornithology (1869)This was Hume's first major work. It had 422 pages and accounts of 81

species. It was dedicated to

Edward Blyth and Dr.

Thomas C. Jerdon who had done more for Indian Ornithology than all

other modern observers put together and he described himself as their

their friend and pupil. He hoped that his book would form a nucleus

round which future observation may crystallize and that others around

the country could help him fill in many of the woeful blanks remaining in

record.

Game Birds of India, Burmah and Ceylon (1879-1881)

This work was co-authored by

C. H. T. Marshall. The three volume work on the game birds was made

using contributions and notes from a network of 200 or more correspondents.

Hume delegated the task of getting the plates made to Marshall. The

chromolithographs of the birds were drawn by W. Foster, E. Neale, M.

Herbert, Stanley Wilson and others and the plates were produced by F. Waller

in London. Hume had sent specific notes on colours of soft parts and

instructions to the artists. He was unsatisfied with many of the plates and

included additional notes on the plates in the book.

In the preface Hume wrote

In the second place, we have had great disappointment in artists.

Some have proved careless, some have subordinated accuracy of

delineation to pictorial effect, and though we have, at some loss,

rejected many, we have yet been compelled to retain some plates which

are far from satisfactory to us.

while his co-author Marshall, wrote

I have performed my portion of the work to the very best of my

abilities, and yet personally felt almost as if I were sailing under

false colors in appearing before the world as one of the authors of this

book; but I allow my name to appear as such, partly because Mr. Hume

strongly wishes it, partly because I do believe that as Mr. Hume says

this work, which has been for years called for, would never have

appeared had I not proceeded to England, and arranged for the

preparation of the plates, and partly because with the explanation thus

afforded no one can justly misconstrue my action.

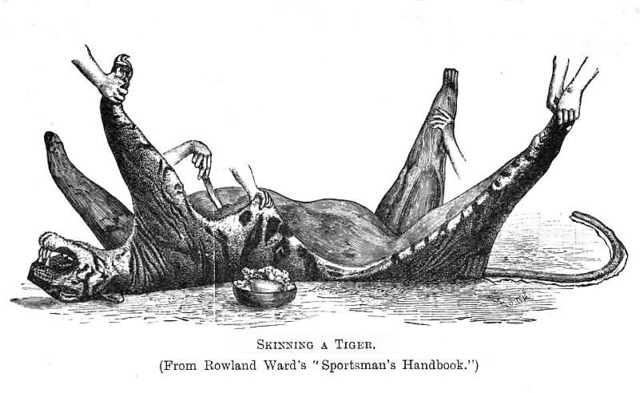

Hume's comment on the illustration The plate is a cruel

caricature of the species, just sufficiently like to permit of

identification, but miscolored to a degree only explicable on

the hypothesis of somebody's colour-blindness… Fortunately for

our supporters, this is the very worst plate in the three

volumes.

White-fronted Goose One of the illustrations that Hume

considered as exceptionally good.

Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds (1883)

This was another major work by Hume and in it he covered descriptions of

the nests, eggs and the breeding seasons of most Indian bird species. It

makes use of notes from contributors to his journals as well as other

correspondents and works of the time.

A second edition of this book was made in 1889 which was edited by

Eugene Oates. This was published when he had himself given up all

interest in ornithology. An event precipitated by the loss of his

manuscripts through the actions of a servant. He wrote in the preface:

I have long regretted my inability to issue a revised edition of

'Nests and Eggs'. For many years after the first Rough Draft

appeared, I went on laboriously accumulating materials for a

re-issue, but subsequently circumstances prevented my undertaking

the work. Now, fortunately, my friend Mr. Eugene Oates has taken the

matter up, and much as I may personally regret having to hand over

to another a task, the performance of which I should so much have

enjoyed, it is some consolation to feel that the readers, at any

rate, of this work will have no cause for regret, but rather of

rejoicing that the work has passed into younger and stronger hands.

One thing seems necessary to explain. The present Edition does not

include quite all the materials I had accumulated for this work.

Many years ago, during my absence from Simla, a servant broke into

my museum and stole thence several cwts. of manuscript, which he

sold as waste paper. This manuscript included more or less complete

life-histories of some 700 species of birds, and also a certain

number of detailed accounts of nidification. All small notes on

slips of paper were left, but almost every article written on

full-sized foolscap sheets was abstracted. It was not for many

months that the theft was discovered, and then very little of the

MSS. could be recovered.

—Rothney Castle, Simla, October 19th, 1889

Eugene Oates wrote his own editorial note

Mr. Hume has sufficiently explained the circumstances under which

this edition of his popular work has been brought about. I have

merely to add that, as I was engaged on a work on the Birds of India,

I thought it would be easier for me than for anyone else to assist

Mr. Hume. I was also in England, and knew that my labour would be

very much lightened by passing the work through the press in this

country. Another reason, perhaps the most important, was the fear

that, as Mr. Hume had given up entirely and absolutely the study of

birds, the valuable material he had taken such pains to accumulate

for this edition might be irretrievably lost or further injured by

lapse of time unless early steps were taken to utilize it.

This nearly marked the end of Hume's interest in ornithology. Hume's last

piece of ornithological writing was done in 1891 as part of an

Introduction to the Scientific Results of the Second Yarkand Mission an

official publication on the contributions of Dr. Ferdinand Stoliczka, who

died during the return journey on this mission. Stoliczka in a dying request

had asked that Hume should edit the volume on the ornithological results.

Indian National Congress

After retiring from the civil services and towards the end of Lord

Lytton's rule, Hume sensed that the people of India had got a sense of

hopelessness and wanted to do something, "a sudden violent outbreak of

sporadic crime, murders of obnoxious persons, robbery of bankers and looting

of bazaars, acts really of lawlessness which by a due coalescence of forces

might any day develop into a National Revolt." There were agrarian riots in

the Deccan and Bombay and Hume decided that an Indian Union would be a good

safety valve and outlet for this unrest. On the 1st of March 1883 he wrote a

letter to the graduates of Calcutta University:[12]

If only fifty men, good and true, can be found to join as founders,

the thing can be established and the further development will be

comparatively easy. ...

And if even the leaders of thought are all either such poor creatures,

or so selfishly wedded to personal concerns that they dare not strike a

blow for their country's sake, then justly and rightly are they kept

down and trampled on, for they deserve nothing better. Every nation

secures precisely as good a Government as it merits. If you the picked

men, the most highly educated of the nation, cannot, scorning personal

ease and selfish objects, make a resolute struggle to secure greater

freedom for yourselves and your country, a more impartial administration,

a larger share in the management of your own affairs, then we, your

friends, are wrong and our adversaries right, then are Lord Ripon's

noble aspirations for your good fruitless and visionary, then, at

present at any rate all hopes of progress are at an end and India truly

neither desires nor deserves any better Government than she enjoys. Only,

if this -be so, let us hear no more factious, peevish complaints that

you are kept in leading strings and treated like children, for you will

have proved yourself such. Men know how to act. Let there be no

more complaining of Englishmen being preferred to you in all important

offices, for if you lack that public spirit, that highest form of

altruistic devotion that leads men to subordinate private ease to the

public, weal that patriotism that has made Englishmen what they are,-

then rightly are these preferred to you, rightly and inevitably have

they become your rulers. And rulers and task-masters they must continue,

let the yoke gall your shoulders never so sorely, until you realise and

stand prepared to act upon the eternal truth that self-sacrifice and

unselfishness are the only unfailing guides to freedom and happiness.

The idea of the Indian Union took shape and Hume also had support from

Lord Dufferin for this although the latter wished to keep a low profile in

the matter. It has been suggested that the idea was originally conceived in

a private meeting of seventeen men after a Theosophical Convention held at

Madras in December 1884. Hume took the initiative, and it was in March 1885,

when the first notice was issued convening the first Indian National Union

to meet at Poona the following December.[12]

South London Botanical Institute

Shortly after Hume's return to London he took up an interest in botany, and

founded and endowed the

South London Botanical Institute which continues to promote the study of

plants to the present day. It was intended as a sort of local alternative to

Kew. The SLBI has a herbarium containing approximately 100,000 specimens

mostly of flowering plants from the British Isles and Europe including many

collected by Hume. The collection was later augmented by the addition of

other herbaria over the years, and has significant collections of Rubus

(bramble) species and of the Shetland flora, the latter including a major

gift from the late Richard Palmer, joint author of the standard work on

Shetland plants. Other resources include a very good library originally

containing Hume's own books. The institute today has classroom facilities, a

small botanical garden, and an ongoing programme of talks and courses. In

the years leading up to the establishment of the Institute, Hume built up

links with many of the leading botanists of his day. He worked with F. H.

Davey and in the Flora of Cornwall (1909), Davey thanks Hume as his

companion on excursions in Cornwall and Devon, and for helping in the

compilation of that Flora, publication of which was financed by him.

References

-

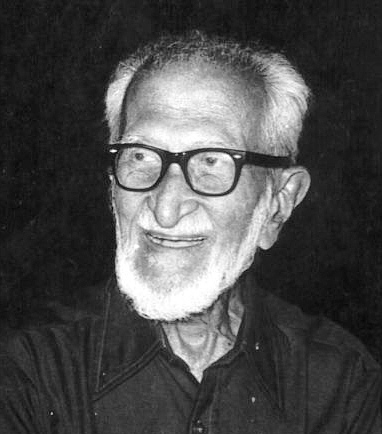

^ Ali, S. (1979) Bird study in India:Its history and its

importance. Azad Memorial lecture for 1978. Indian Council for

Cultural Relations. New Delhi.

-

^ According to the Dictionary of National Biography however

Encyclopaedia Britannica

[1] gives his birthplace as Montrose, Forfarshire

- ^

a

b

c

d

e

f

g

h

i

j

k

l

m

n

o Moulton, Edward (2003) 'The

Contributions of Allan O. Hume to the Scientific Advancement of

Indian Ornithology' in Petronia: Fifty Years of Post-Independence

Ornithology in India, ed. J. C. Daniel and G. W. Ugra.

Bombay Natural History Society - New Delhi: Oxford University

Press, New Delhi. Pages 295-317.

-

^ Footnote in Lydekker, 1913: This was a thorn-hedge

supplemented by walls and ditches, and strongly patrolled for

preventing the introduction into British territory of untaxed salt

from native states(see Sir

John Strachey's "India," London, 1888).

-

^ Lydekker, R. (1913) Catalogue of the Heads and Horns of

Indian Big Game bequeathed by A. O. Hume, C. B., to the British

Museum.

Scanned version

-

^

Stamp commemorating Hume - Indian Postal Department

-

^ S. Dillon Ripley (1961) A Synopsis of the Birds of India

and Pakistan. Bombay Natural History Society.

-

^ Hume, A. 1869. Ibis 2 (5): 355–357 (no title).

-

^ Bensch, S and D. Pearson (2002) The Large-billed Reed

Warbler Acrocephalus orinus revisited. Ibis (2002), 144:259–267

PDF

Nucleotide sequence

-

^ Murray, James A. 1888. The avifauna of British India and

its dependencies. Truebner. Volume 1.

-

^ Warr, F. E. 1996. Manuscripts and Drawings in the

ornithology and Rothschild libraries of The Natural History Museum

at Tring. BOC.

- ^

a

b Sitaramayya, B. Pattabhi. 1935. The

History of the Indian National Congress. Working Committee of the

Congress.

Scanned version

Further reading

- Bruce, Duncan A. (2000) The Scottish 100: Portraits of History's

Most Influential Scots, Carroll & Graf Publishers.

- Buck, E. J. (1904) Simla, Past and Present. Thacker & Spink,

Calcutta, 1904.

excerpt

- Mearns and Mearns (1988) Biographies for Birdwatchers.

Academic Press.

ISBN 0-12-487422-3

- Moxham, Roy (2002) The Great Hedge of India.

ISBN 0-7567-8755-6

- Wedderburn, W. 1913. Allan Octavian Hume. C.B. Father of the Indian

National Congress. T.F. Unwin. London.

External links

[Quelle:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allan_Octavian_Hume. -- Zugriff am

2007-09-05] |