Zitierweise / cite as:

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā / übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. -- Anura. -- Fassung vom 2010-09-16. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/anura.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2010-09-16

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung SS 2007

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

WARNUNG: dies ist der Versuch einer

Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen Textes. Es ist keine

medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier genannten Heilmittel wird

darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut ausgebildeter ayurvedischer

Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen machen!

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Verwendete und zitierte Werke siehe: http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/caraka000b.htm

Liste von in Indien vorkommenden Amphibien, der die untenstehende Auflistung folgt: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_amphibians_of_India. -- Zugriff am 2007-09-03

In Indien kommen u.a. folgende Froscharten vor:

Abb.:

Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis - Common skittering frog,

Weibchen

[Bildquelle: Saleem Hameed / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.:

Euphlyctis hexadactylus - Indian Five-fingered Frog

[Bildquelle:

Saleem Hameed / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.:

Fejervarya cancrivora - Crab-eating Frog: verträgt

Leben im Salzwasser!

[Bildquelle: W.A. Djatmiko / Wikipedia. -- GNU

FDLicense]

Abb.:

Fejervarya limnocharis - Alpine cricket frog

[Bildquelle:

Saleem Hameed / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoplobatrachus. -- Zugriff am 2007-09-03

Abb.:

Hoplobatrachus tigerinus - Indian Bullfrog, Western Ghats

[Bildquelle: Sandilya Theuerkauf / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.:

Hoplobatrachus tigerinus - Indian Bullfrog, Bangalore (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)

[Bildquelle:

Saleem Hameed / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limnonectes.

-- Zugriff am 2007-09-03

Gattung Minervarya Dubois, Ohler, and Biju, 2001

Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minervarya_sahyadris. -- Zugriff am

2007-09-03

Wikipedia:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Occidozyga. -- Zugriff am 2007-09-03

Abb.:

Indirana semipalmata, Shola at Talakaveri (ತಲಕಾವೇರಿ),

Coorg (ಕೊಡಗು), India

[Bildquelle: L.

Shyamal / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.:

Clinotarsus curtipes - Bicolored Frog, Männchen in

Hochzeitskleidung

[Bildquelle: L. Shyamal / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.:

Clinotarsus curtipes - Bicolored Frog

[Bildquelle: L. Shyamal

/ Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.:

Hydrophylax malabaricus - Fungoid Frog

[Bildquelle: Viren Vaz

/ Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.:

Sylvirana temporalis - Bronzed Frog bei Begattung

[Bildquelle:

Sandilya Theuerkauf / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.:

Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis

[Bildquelle: Karthickbala / Wikipedia.

-- GNU FDLicense]

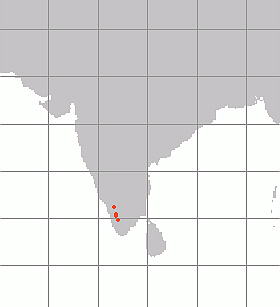

Abb.: Verbreitung des

Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis

[Bildquelle: L. Shyamal / Wikipedia. --

Public domain]

Cunningham:

"COMMON

FROGS AND TOADS OF AN INDIAN GARDEN" Ne let the unpleasant queyre of frogs still croking,

Make us to wish theyr choking.

SPENSER.COMMON bull-frogs, Rana tigrina, are imposing creatures, both in respect to size and colour. Large specimens are often

more than half a foot in length, and, in many cases, are very brilliantly coloured, more especially when they have just been summoned out from their subterranean haunts by the onset of the first heavy showers of the rainy season. At this time, and seemingly as the result of etiolation, they often show no dark markings, but are uniformly painted in a bright canary yellow that makes them stand out very conspicuously among the green tints of the surrounding grass and weeds. Very soon, however, they begin to darken, and presently their coats acquire a greenish-yellow or bright olive ground, thickly variegated with bold dark blotches, the general effect being such as to render them very likely to escape notice whilst in their wonted environments. In many cases, indeed, the harmony is so great, that the only thing about them that may lead to detection is the persistently brilliant yellow of their great, shining, goggle eyes. Even as it is, their marvellous capacity for absolute immobility often serves so effectually to conceal them that their presence is only revealed when they are almost underfoot, and go off with sudden and huge leaps that are very startling to the nerves of both men and dogs. The capacity for protective change in colour in this instance, although not acting so rapidly as it does in the case of wall-geckos and many kinds of fish, is yet very striking.Bull-frogs are excessively voracious, and

many well-authenticated instances are on record of their successful capture of small birds, and even of palm-squirrels, who have had the mishap to fall into ponds haunted by them. Their fiercely carnivorous tendencies manifest themselves very early. This may be readily ascertained by putting some of the small black tadpoles of the common toad, Bufo melanostictus, into an aquarium containing a few of their colossal grey relatives. At a time when I was not fully informed in regard to their habits, I tried keeping a mixed collection of both kinds of tadpoles in a jar of distilled water, and was astonished to find that the small ones rapidly disappeared. The process went on until it became necessary to introduce a fresh stock, and then the problem was solved ; for the frog-tadpoles were so ravenous, owing to prolonged fasting, that they fell upon the new arrivals at once, seizing, shaking, and worrying at them as soon as they entered the water. Their carnivorous habits render bull-frogs very unwelcome neighbours where it is desired to stock a small body of water with fish, as the havoc that they play among small and even half-grown fry is very great. They are quite omnivorous in their appetite for animal food, and sometimes come to grief in their greedy attempts to secure it. I once found a curiously illustrative specimen of the risks to which they are exposed by their voracity. It consisted of a dead bull-frog with the hind legs of a toad projecting from its mouth and firmly hooked down over the angles of the jaws. The frog had evidently seized its prey by the muzzle, but in the effort to gulp it down, had only succeeded in wedging it into its gullet, where it remained anchored.During

their periods of activity they are seldom to be found at any considerable distance from water, and even at times when the greater number of them are lying dormant, solitary specimens are sometimes to be met with, sitting silent and motionless on the bank of a pond, but ready on the least alarm to go off in a gigantic leap that lands them souse into the water with a resounding splash. It is quite astonishing to see how quickly they will people pieces of open ground that are converted into swamps by the onset of the monsoon. For weeks and months before, the ground may have remained seemingly quite dry, with all its grass and weeds baked by the continuous blaze of sunshine, and giving no hint of the presence of any frogs ; but, after a few hours of drenching rain, it will be dotted all over by huge yellow monsters filling the air with a deafening uproar. In some years many heavy thunderstorms take place long before the regular onset of the monsoon, and lure out a certain number of frogs to a premature emergence from which they are fain to retire on the recurrence of continuous dry weather. Almost every year, too, after one of the brief deluges attending a "nor'-wester," the gruntings of a few particularly anticipative individuals are temporarily audible. Like many other animals in tropical regions, they seem often to suffer from epidemic disease, for now and then they will be very scarce for several successive years in which the climatic conditions are highly favourable to their activity, whilst in other seasons, in which defective rainfall must have greatly narrowed the areas congenial to them, the sounds of their concerts are everywhere audible.When it is possible to watch the performers closely it will be found that the concerts are built

up of numerous dialogues, in which one of each pair says "ough," and the other forthwith replies "ver, rugh." Such utterances recur several times in succession; a short pause follows, and then the conversation begins again. The curious thing is that all the performers seated in one patch of swamp should have such a tendency to synchronous action that periods of total silence alternate with those of general uproar. The phenomenon is parallel to that of the synchronous luminosity that sometimes occurs so markedly in groups of fireflies. When bull-frogs first come out for the season, the din that they can make is often enough to be very annoying to light sleepers. A friend of mine, whilst living in a house close to which were two small frog-haunted ponds, used to go to bed every night with a hog-spear lying handy for use when the nocturnal uproar became more than usually offensive, and another inmate of the same place was often driven to make excursions with a saloon pistol in the vain hope of being able to kill his tormentors. In addition to their sexual grunting cries, bull-frogs have another and very distinct call which sounds exactly like a number of small bladders bursting in rapid succession.Considering

how essentially aquatic they are, it is somewhat surprising to find them depositing their ova in the sites which they generally choose for that purpose. The common toads, who are by no means inclined in their adult state to confine themselves to the immediate neighbourhood of water, and who are often to be met with in hosts in places in which the soil is very dry for many weeks at a time, always lay their eggs in water ; but bull-frogs certainly do not usually do so. On the contrary, they choose places which, although near and often overhanging bodies of water, are above, and often considerably above them. In the rainy season, large masses of white, frothy matter, looking like colossal "cuckoo spits," are often to be seen placed among the twigs of shrubs growing on the banks of ponds, or on any islet in the water. Their appearance is so peculiar and so little suggestive of their true nature that a very distinguished zoologist, on observing them in the Garden at Alipur, had some specimens collected and sent to me as fungal growths. A very casual inspection of their contents was enough to show that he was mistaken. They are composed of a frothy matrix, soft and semi-fluid in the interior of the mass, but setting into a membranous layer on the surface, and including innumerable ova. The latter hatch out into their soft bed, and the young tadpoles continue to inhabit it for a considerable time, passing through the earlier stages of evolution in it, and, only after having become considerably developed, working their way out to fall into or struggle down to the water. The spectacle that appears when one of the masses is laid open and discloses its frothy contents, alive with pallid, wriggling creatures, is truly gruesome.Every

evening during the rainy season all the lawns are thickly dotted over by multitudes of common toads, Bufo melanostictus, with brightly lustrous eyes and curiously mottled and tuberculate skins (Plate XXI.).

Pl. XXI. Common Indian ToadWhen the weather becomes drier they cease to come out in such numbers, and, during the prolonged drought of winter and spring, very few venture to leave their retreats among the dead leaves in shaded coverts, or in the cavernous recesses beneath culverts and the basements of buildings. Individual specimens vary in colour very greatly, and both temporarily and permanently. At the time of their greatest activity some of them are deeply coloured with velvety black tubercles standing out on a background of rich brown, whilst a whole series of lighter varieties range through different shades of brown and ochre to culminate in specimens of such pale cream-colour as to seem almost white in the dusk. When they come out suddenly from their shaded diurnal retreats into strong light they show changes in tint parallel to those taking place in wall-geckos in like circumstances; and, when they have remained for a long time hidden away during continuous periods of dry weather, they acquire a specially dingy, dusky hue of a more persistent character, which is accompanied by a shrivelled and dusty condition of skin that makes them look very unlike what they are when humidity and food abound. When in full activity, and especially during the breeding season, the tubercles on their skins are full of a thick whitish secretion, which exudes on any external pressure or when the animal is excited or alarmed. It possesses highly acrid and irritant properties, as is very evident from the effect that it produces on dogs. Sporting terriers, in default of any nobler game, are very ready to put up with a toad-hunt, and when new to the country, will often lay hold on their quarry. A single experience of the results of doing so is, however, usually enough to teach them an effectual lesson of avoidance. Even very slight contact causes them to foam at the mouth and to go about shaking their heads from side to side with signs of extreme disgust, and a good grip is usually followed by such symptoms, together with violent sickness and evidences of great general depression. Most dogs, therefore, soon become very cautious of touching toads, and it is often very diverting to observe the conflict between desire to seize the game and dread of coming into contact with it. In some cases, however, no experience is effectual, and, in the excitement of the chase, prudence goes to the wall, with disastrous results. The toads seem to be quite aware of the protective nature of their venom, and in many cases obstinately refuse to stir even when patted by the paws of the dog, preferring to remain fixed on the spots at which they have been surprised, and to exude the poison while they blow themselves out until it appears as though they must inevitably burst.

Their call is a relatively feeble one, but, owing to the enormous numbers in which they occur, they are most important performers in the nocturnal concerts that fill the air in the neighbourhood of ponds, and are often so powerful as almost to drown those of the crickets and cicadas in the surrounding trees.

Their eggs, unlike those of the bull-frogs, are always laid in water, and, during the earlier half of the rainy season, almost every pond is full of swarms of their small, black tadpoles. A little later the young toads begin to come ashore, and then it is often very difficult to avoid treading on the hosts of little black creatures, who hop about over the roads and grass in such numbers that one might well imagine that "the land has brought forth frogs." The emergence of a flight of white ants is always an occasion of joyful excitement among the toads of the neighbourhood. They come hurrying in from every quarter to congregate around the place where the awkwardly struggling insects are crowding and rustling up from the soil, and settle themselves down to a prolonged and copious feast.

Abb. Grass Snake swallowing a ToadSeveral other kinds of frogs and toads are constantly to be found in gardens in numbers that vary according to the climatic conditions prevailing at different times of year. The most beautiful of all the frogs occurring about Calcutta is one in which the upper surface is painted in the most vivid emerald green, contrasting wonderfully with the snowy white of the under parts and with two patches of bright rose-colour near the angles of the mouth. Specimens of it are rarely noticed, but this may in great part be due to their essentially aquatic habits, and also to the wonderful way in which their colouring harmonises with that of the floating leaves on which they sit when they do emerge from the water. They very seldom venture to land upon the banks of a pond, and are usually to be seen sitting motionless on the leaves of Nymphaeas or Nelumbiums, and ready on the least alarm to slip off into the surrounding water.

Towards

the end of the rainy season, when everything is at its wettest, and specially in years when the rainfall has been so abundant as to cause the formation of numerous temporary pools in the hollows of grass-land, a curious little song may often be heard issuing from garden lawns. So sweet and clear is it, that, unless the nature of the songster is already known, it may readily be mistaken for that of a bird. If, however, the places from which it proceeds be stealthily approached and absolute immobility be maintained, it will be found that the songsters really are very small and wonder fully agile frogs, who every now and then lift up their heads and pour forth a torrent of small, sweet notes. The process of discovery is by no means an easy one, as the animals are very small, and provided with highly protective colouring, and also because their notes seem to alter in direction at frequent intervals in a curiously ventriloquial way.

Pl. XXI. Tree FrogThe

little tree-frogs, Rhacophorus maculatus (Plate XXI.), are not very common in Calcutta, but occasionally a garden will be found in which the local conditions are so much to their taste as to lead to the presence of a large colony within its limits. Now and then, too, a frog will come exploring into a house and go hopping around over the floors and furniture ; but such an event is rare, and they never show any inclination to establish themselves as permanent inmates. In many parts of Southern India, however, they are almost as common in houses as the wall-geckos, and indeed, owe their common Anglo-Indian name of "Chunam-frogs" to the way in which, on any alarm, they make off in a series of rapid leaps across the floor to spring up and remain adherent to the whitewash of the walls at a considerable height above the ground."[Quelle: Cunningham, D. D. (David Douglas) <1843-1914>: Some Indian friends and acquaintances; a study of the ways of birds and other animals frequenting Indian streets and gardens. -- London : J. Murray, 1903. -- viii, 423 S. : Ill. ; 21 cm. -- S. 359 - 369. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/someindianfriend00cunnrich. -- Zugriff am 2007-09-15]