Zitierweise / cite as:

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā / übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. -- Melursus ursinus. -- Fassung vom 2010-12-09. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/melursus_ursinus.htm

Erstmals publiziert:

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung SS 2007

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

WARNUNG: dies ist der Versuch einer

Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen Textes. Es ist keine

medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier genannten Heilmittel wird

darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut ausgebildeter ayurvedischer

Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen machen!

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Verwendete und zitierte Werke siehe: http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/caraka000b.htm

Abb.: Melursus ursinus - Lippenbär, Sri Lanka

[Bildquelle: Bodhitha

/ Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

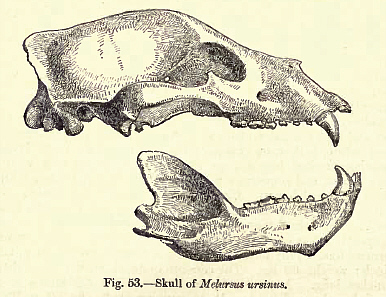

Abb.: Schädel von Melursus ursinus - Lippenbär

[Bildquelle: Blanford 1888/91]

Abb.: Bärenjagd mit Hunden

[Bildquelle: Sanderson, 1893]

Lydekker:

"THE SLOTH-BEAR.

Genus Melursus.

The well-known Indian sloth-bear (Melursus ursinus), commonly known in its native country by the name of Bhalu, but by the Mahrattas termed the Aswal, differs so remarkably from all the other members of the family that it is generally regarded as forming a genus by itself. It differs from all the typical bears by having but two pairs of incisor or front-teeth in the upper jaw, so that the total number of teeth is forty instead of forty-two. Moreover, all the cheek-teeth are much smaller in proportion to the size of the skull than in other bears, while the palate of the skull is deeply concave, instead of being nearly flat. The claws are also unusually large and powerful, and the snout and lower lip are much elongated and very mobile. The sloth-bear is, at best, but an ugly-looking animal, and is generally of smaller size and less bulk than the Himalayan black bear. It is covered with very long and coarse fur, which attains its greatest length on the shoulders. With the exception of the end of the muzzle being dirty grey, and of the white chevron on the chest, the colour of the fur is black, but the long claws are white. As regards size, this species measures from about 4½ feet to 5 feet 8 inches in the length of the head and body, the tail generally measuring from 4 to5 inches, exclusive of the hair; the height at the shoulder varying from 2 feet 2 inches to about 2 feet 9 inches. Large males

may weigh as much as 280 Ibs., while there is one instance recorded of a specimen weighing as much as 320 Ibs.The sloth-bear

may be regarded as one of the most characteristic, and at the same time one of the commonest of the mammals of India. It is found in Ceylon, and in the peninsula of India from Cape Comorin nearly to the foot of the Himalaya. Mr. Blanford states that it ranges as far west as the province of Katiawar, and is also occasionally found in Cutch, while to the northwards its range is probably limited by the great Indian desert. It occurs in North-Eastern Bengal, but how far its range extends in this direction is not fully ascertained, there being some doubt whether the large black bear found in the plains of Assam is this species or the Himalayan black bear. Within the last thirty or forty years it has been completely exterminated from some parts of Bengal and the Deccan.

Habits Perhaps the best account of the habits of this bear is one drawn up by Mr. Blanford, partly from the results of his own observations and partly from those of others. It is there stated that these bears "are generally found solitary or in pairs, or three together ; in the latter case a female with two cubs, often nearly or quite full-grown. Occasionally four or five are met with in company. They inhabit bush and forest, jungle and hills, and are particularly fond of caves in the hot season and monsoon, and also when they have young.

Throughout several parts of the peninsula of India there are numerous hills of a granitoid gneiss that weathers into huge loose rounded masses. These blocks remain piled on each other, and the great cavities beneath them are favourite resorts of bears, as in such places the heat of the sun, and some of the insects that are most troublesome in the monsoon can be avoided. In the cold season, and at other times when no caves are available, this animal passes the day in grass or bushes, or in holes in the banks of ravines. It roams in search of food at night, and near human habitations is hardly seen in the daytime; but, in wild tracts uninhabited by man, it

may be found wandering about as late as eight or nine o'clock in the morning, and again an hour or even more before sunset in the afternoon. In wet or cloudy weather, as in the monsoon, it will sometimes keep on the move all day. But the sloth-bear, although, like most other Indian animals, it shuns the midday sun, appears by no means so sensitive to heat as might be expected from its black fur, and it appears far less reluctant to expose itself at noonday than is the tiger. I have seen a family of bears asleep at midday in May on a hillside in the sun. They had lain down in the shade of a small tree, but the shade had shifted without their being disturbed. It is scarcely necessary to observe that this bear does not hibernate. Owing to its long, shaggy, coarse fur, its peculiarly shaped head, its long mobile snout, and its short hind-legs, this is probably the most uncouth in appearance of all the bears, and its antics are as comical as its appearance. Its usual pace is a quick walk, but if alarmed or hurried it breaks into a clumsy gallop, so rough that when the animal is going away it looks almost as if propelled from behind and rolled over and over. It climbs over rocks well, and, like other bears, if alarmed or fired at on a steep hillside, not unfrequently rolls head-over-heels down hill. It climbs trees, but slowly and heavily; the unmistakable scratches left on the bark showing how often its feet have slipped back some inches before a firm hold was obtained."As might have been predicted from the small size and half-rudimentary condition of its molar teeth, the food of the sloth-bear consists almost exclusively of fruits, flowers, and insects, together with honey. Its favourite fruits appear to be those of the ebony tree, the jujube-plum, several kinds of figs, and the long pods of the cassia. Whether grapes, as shown in our illustration, form also part of the diet of these bears, or whether this is merely a fancy on the part of the artist, we are unaware. During the months of February and March, in

many parts of India, the beautiful fleshy scarlet flowers of the mowha tree are nightly shed in great profusion, and form a rich feast for many denizens of the jungle, prominent among which is the sloth-bear, by whom these flowers are greatly relished. In addition to beetles and their larvse, as well as young bees and honey, the sloth-bear is also passionately fond of white ants or termites. On this point Colonel Tickell, as abridged by Dr. Jerdon, observes that " the power of suction in this bear, as well as of propelling wind from its mouth, is very great. It is by this means it is enabled to procure its common food of white ants and larvse with ease. On arriving at an ant-hill, the bear scrapes away with the fore-feet until he reaches the large combs at the bottom of the galleries. He then with violent puffs dissipates the dust and crumbled particles of the nest, and sucks out the inhabitants of the comb by such forcible inhalations as to be heard at two hundred yards' distance or more. Large larvae are in this way sucked out from great depths under the soil. Where bears abound, their vicinity may be readily known by numbers of these uprooted ants' nests and excavations, in which the marks of their claws are plainly visible. They occasionally rob birds' nests and devour the eggs. . . . The sucking of the paw, accompanied by a drumming noise when at rest, and especially after meals, is common to all bears, and during the heat of the day they may often be heard humming and puffing far down in caverns and fissures of rocks.'Like the fox-bats and the palm-civets, the sloth-bear will often visit the vessels hung on the palm-trees for the sake of their juice, and is said frequently to become very drunk in consequence. Sugar-cane is likewise a favourite dainty of these bears, which frequently do a large amount of damage to such crops.

Although they generally subsist entirely on vegetable substances and insects, it seems that they will occasionally eat flesh ; Sanderson mentioning an instance where one of them devoured the carcase of a recently-killed muntjac deer, the proof that a bear was the devourer being afforded by the imprints of its feet in the wet soil. The same observer also mentions that he has known bears gnaw the dry bones of cattle that have died in the jungle.

With the exception of the puffing and humming noises already mentioned, the Indian sloth-bear is generally a silent animal. Mr. Blanford states, however, that "occasionally they make the most startling noise, whether connected with pairing or not I cannot say. I have only heard it in the beginning of the cold season, which is not their usual pairing-time. They occasionally fight under fruit-trees, but I think the noise then made is rather different."

Like most other members of the family, the sloth-bear has the sense of hearing but poorly developed, and its eyesight is also far from good ; and hence it has a peculiarly comical way of peering about when it suspects intruders, as though it were short-sighted. From these deficiencies of sense it can be approached very closely from the leeward side. Its sense of smell, is, however, wonderfully acute, and by its aid it is enabled to detect concealed supplies of honey, and also to scent out ants' nests when situated far below the ground.

The number of cubs produced at a birth is, as in most bears, usually two, but it appears that there

may sometimes be three. The young cubs are generally carried on the back of the female when the animals are on the move : and the author last mentioned observes that it is an amusing sight to watch the cubs dismount at the feeding-grounds, and scramble back to their seat at the first alarm. We are informed by Mr. Sanderson that the cubs are carried about in this manner till they are several months old and have attained the dimensions of a sheep-dog, and that when there is room for only one cub on the maternal back the other has perforce to walk by the side.In regard to their family life, Mr. Sanderson observes that these "bears are exceedingly affectionate animals amongst themselves, and are capable of being most thoroughly tamed when taken young. Either wild or tame they are very amusing in their ways, being exceedingly demonstrative and ridiculous. Though hard to kill, they are very soft as to their feelings, and make the most hideous outcries when shot at not only the wounded animal, but also its companions. It has frequently been stated by sportsmen that if a bear be wounded he immediately attacks his companions, thinking that they have caused his injuries. But I think this is not quite correct, at least in the majority of cases. I have observed that a wounded bear's companions generally rush to him to ascertain the cause of his grief, joining the \vhile in his cries, when he, not being in the best of humours, lays hold of them, and a fight ensues, really brought about by the affectionate but ill-timed solicitude of his friends."

In commenting upon the latter portion of this passage, Mr. Eianford supports the old view that the attack is made directly by the wounded animal ; and one instance is mentioned where he saw a female when wounded immediately commence an unprovoked attack upon her two half-grown cubs, which were severely cuffed. In another case, when two full-grown bears were both hit, they stood up and fought on their hind-legs, till one fell dead from the effects of the bullet.

Although generally timid in their nature, sloth-bears will on rare occasions attack human beings without provocation, and when they do so, fighting both with teeth and talons, and inflicting terrible wounds, more especially on the head and face. These attacks generally occur when a bear is accidentally stumbled upon by a native wandering in the jungle, and are then due more to timidity than to ferocity. Mr. Sanderson is of opinion that a bear, being a slow-witted animal, is more likely to attack in such a case than is a tiger or a leopard, which more rapidly collect their senses, and are thus less embarrassed by the sudden and unexpected encounter. Mr. Blanford states that when thus surprised a sloth-bear will sometimes merely knock a

man over with its paws, although thereby inflicting severe wounds; but on other occasions it seizes and holds in its paws its unfortunate victim, who is not released until bitten and clawed to death. Females with young, and occasionally solitary bears, will at times make unprovoked attacks of great ferocity. The idea that sloth-bears hug their victims is scouted by both writers.Sloth-bears are usually hunted in India either by driving them from cover with a line of beaters, or by the sportsman going to their caves or lairs among the rocks at daybreak, and shooting them as they return home from their nightly wanderings. Mr. Sanderson says that in the forests of Mysore he was in the habit of shooting bears by following them with trackers ; and that, as they seldom left off feeding before nine in the morning, it was generally possible by starting at daybreak to come up with them before they had retired to rest for the day. If, however, the party did not succeed in this, the bears would generally be found lying asleep under the shade of a clump of bamboos, or a rock, as there were no caves in the district into which they could disappear. Elephants, it appears, have a great dislike to bears, and on this account, as well as from the rocky nature of the country generally inhabited by these animals, are but rarely employed in bear-shooting. Mr. Sanderson was also in the habit of hunting bears with large dogs, and despatching them when brought to bay with his hunting-knife ; and in this exciting sport was very successful.

Regarding the sport afforded by the sloth-bear, the same hunter observes that "bear-shooting is one of the most entertaining of sports. Some sportsmen have spoken disparagingly of it, and I daresay sitting up half the night watching for a bear's return to his cave, and killing him without adventure,

may be poor fun. . . . But bear-shooting conducted on proper principles, with two or three bears afoot together, lacks neither excitement nor amusement. It is not very dangerous sport, as the animal can be so easily seen, whilst he is not so active as a tiger or a panther. Still he is very tough, and to anyone who would value him for his demonstrations, he would appear sufficiently formidable. If a bear charges he can generally be killed without more ado by a shot in the head when within two paces. The belief that a bear rises on his hind-legs when near his adversary, and thus offers a shot at the horseshoe mark on his chest, is groundless. I have shot several bears within a few feet, and they were still coming on on all-fours. No doubt when a bear reaches his man he rises to claw and bite him, but not before."Jerdon states that in the extreme south of India, among certain hilltribes known as Polygars, sloth-bears used to be hunted with large dogs, and when brought to bay were attacked by the hunters with long poles smeared at the end with bird-lime. The bird-lime caused the shaggy coat of the bears to become fixed to the end of the pole, so that the animals soon became firmly held. A single fragment of a bone of the fore-limb discovered in a cave in Madras proves that the sloth-bear has been an inhabitant of India since a period when several kinds of extinct mammals flourished there.

And the extinct Theobald's bear from the Siwalik Hills, mentioned on p. 26, serves to indicate that the sloth-bear is a specially-modified form derived from bears belonging to the typical genus, since the skull of that extinct species presents characters intermediate between those of ordinary bears and that of the sloth-bear."[Quelle: Lydekker, Richard <1849-1915>: The royal natural history / edited by Richard Lydekker ; with preface by P.L. Sclate. -- London ; New York : F. Warne, 1893-96. -- 6 Bde. : ill. (some col.) ; 26 cm. -- Bd. 2. -- S. 26 - 32. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/royalnaturalhist02lyderich. -- Zugriff am 2007-09-27]

Blanford:

Melursus ursinus. The Sloth-Bear or Indian Bear.

Bradypus ursinus, Shaw, Naturalists' Miscellany, ii, pi. 58 (c. 1791).

Ursus labiatus, de Blainv. Bull. Soc. Philom. 1817, p. 74 ; Sykes, P. Z. S. 1831, p. 100 ; Elliot, Mad. Journ. L. S. x, p. 100 ; Tickell, Calc. Journ. N. H. i, p. 199, pi. vii ; Blyth, Cat. p. 77 ; Jerdon, Mam. p. 72.

Ursus inornatus, Pucheran, Rev. May. Zool. vii, p. 392 (1855).Rinch or Rick, Bhalū, Adam-zād, H. ; Bhalūk, Beng. ; Riksha, Sanscr. ; Aswal, Mahr ; Yerid, Yedjal, Asol, Gond. ; Bir Mendi, Oraon ; Bana, Kol ; Elugu, Tel. ; Kaddi or Karadi, Can. and Tarn. ; Pani Karudi, Mal. ; Usam Cingalese.

Fur long and coarse, longest between the shoulders. In the skull the palate is broad and concave, and extends back farther than in other bears, covering about two thirds of the space between the posterior molars and the hinder terminations of the pterygoids.

Colour. Black, end of muzzle dirty grey ; a narrow white horseshoe-shaped mark on the chest. Claws white.

Dimensions. Head and body 4 ft. 6 in. to about 5 ft. 8 in. long ; tail without hair 4 to 5 inches. Males as a rule are larger than females. Height at shoulder 2 ft. 2 in. to about 2 ft. 9 in. Weight of a small female 170 lbs. ; large males weigh as much as 20 stone (280 lbs.) or more ; I find one in the ' Asian ' recorded as weighing 320 lbs. A large male skull is 11 inches in basal length, and 7.8 broad across the zygomatic arches.

Distribution. The peninsula of India from near the base of the Himalayas to Cape Comorin, and Ceylon, chiefly in hilly and jungly parts. To the west this bear is found in Kattywar and has occasionally been met with in Cutch, whilst further north its range appears to be limited by the Indian desert. The eastern limit is more doubtful. The sloth-bear appears to be found, though not commonly, in Eastern and Northern Bengal ; but whether the bear of the Assam plains is this species or Ursus torquatus, I have not been able to ascertain. Theobald even suggests that the sloth-bear may occur in Pegu, as be possessed a young animal at Toungoo with but four upper incisors.

Habits. An excellent account is given by Tickell, and numerous details have been added by Jerdon, Forsyth, Sanderson, McMaster, and others, from which and my own observations the following notes are drawn up.

The sloth-bear is still one of the commonest wild animals of India, though its numbers have been greatly diminished by sportsmen throughout the country, and in some districts, as in parts of the Deccan and Bengal, where it was common 30 or 40 years ago, it has been exterminated. Wherever it occurs its presence is shown by the holes it digs to get at termites, by marks of its claws on trees that it has ascended for honey, and by its peculiar tracks.

These animals are generally found solitary or in pairs, or three together; in the latter case a female with two cubs, often nearly or quite full-grown. Occasionally four or five are met with in company. They inhabit bush and forest-jungle and hills, and are particularly fond of caves in the hot season and monsoon, and also when they have young. Throughout several parts of the peninsula of India there are numerous hills of a kind of granitoid gneiss that weathers into huge loose rounded masses. These blocks remain piled on each other, and the great cavities beneath them are favourite resorts of bears, as in such places the heat of the sun, and some of the insects (flies, mosquitoes, &c.) that are most troublesome in the monsoon, can be avoided. In the cold season, and at other times where no caves are available, this animal passes the day in grass or bushes or in holes in the banks of ravines. It roams in search of food at night, and, near human habitations, is rarely seen in the daytime ; but in wild tracts, uninhabited by man, it may be found wandering about as late as 8 or 9 o'clock in the morning, and again an hour or even more before sunset in the afternoon. In wet or cloudy weather, as in the monsoon, it sometimes keeps on the move all day. But the sloth-bear, although , like most other Indian animals, it shuns the midday sun, appears by no means so sensitive to heat as might be expected from its black fur, and it appears far less reluctant to expose itself at noonday than the tiger is. I have seen a family of bears asleep at midday in May on a hill-side in the sun. They had lain down in the shade of a small tree, but the shade had shifted without their being disturbed. It is scarcely necessary to observe that this bear does not hibernate.

Owing to its long shaggy coarse fur, its peculiarly shaped head, its long mobile snout, and its short hind legs, this is probably the most uncouth in appearance of all the bears, and its antics are as comical as its appearance. Its usual pace is a quick walk, but if alarmed or hurried it breaks into a clumsy gallop, so rough that when the animal is going away at full speed it looks almost as if propelled from behind and rolled over and over. It climbs over rocks well, and, like other bears, if alarmed or fired at on a steep hill-side, not unfrequently rolls head over heels down hill. It climbs trees, but slowly and heavily, the unmistakable scratches left on the bark showing how often its feet have slipped back some inches before a firm hold was secured. I cannot, however, confirm the statement of some observers that this animal only ascends trees with rough bark ; unless I am greatly mistaken I have seen its scratches far up the smooth stems of kowā trees (Terminalia arjuna).

The food of the sloth-bear consists almost entirely of fruits and insects. Amongst the former the jujube plum or ber (Zizyphus jujuba), the fruits of the ebony tree (Diospyros tnelanoxylori), jamun (Eugenia jambulana) bel (Aegle marmelos), and of various kinds of figs, especially bar or banyan (Ficus indica) and gular (F. glomerata), the pods of Cassia fistula, and the fleshy sweet flower of the mhowa (Bassia latifolia) are much eaten by these animals, each in its season, but many other wild and cultivated fruits are devoured when procurable. Beetles and their larvae, the honey and young of bees, and above all the combs of termites or white ants furnish food for the Indian bear. In their nocturnal rambles these animals visit many fruit-trees, sometimes climbing amongst the branches to shake down the fruit, or standing up and dragging it down with their paws ; they also turn over stones to search for insects and larvae, ascend trees to plunder bees' nests, and dig out the nests of white ants, sometimes making holes 5 or 6 feet deep for this purpose. These holes are easily recognized by the marks of the bears' claws.

Tickell says (and his views are confirmed by others) :" The power of suction in the bear, as well as of propelling wind from its mouth, is very great. It is by this means it is enabled to procure its common food of white ants and larva) with ease. On arriving at an ant-hill the bear scratches away with his fore feet until he reaches the large combs at the bottom of the galleries. He then, with violent puffs, dissipates the dust and crumbled particles of the nest, and sucks out the inhabitants of the comb by such forcible inhalations as to be heard at two hundred yards distance or more. Larvae, especially the large; ones of the Ateuchus sacer, are in this way sucked out from great depths under the soil."

In Southern India bears are fond of the fermented juice of the wild date-palm, and climb the trees to get at the pots in which it is collected. The animals are said at times to get very drunk with palm-juice. They are very fond, too, of sugar-cane, and do much damage to the crops ; they also occasionally eat various pulses, maize, and some other kinds of corn, and cultivated fruits such as mangoes.

According to Tickell, they rob birds' nests and eat the eggs. I have never heard an authenticated case of their killing larger animals for food, and as a rule they do not touch flesh ; but Sanderson records an instance in which a muntjac that had been shot and left in the jungle was partly devoured by one, and he says that they often gnaw dry bones of cattle. McMaster also relates how the body of a bullock that had been killed by a tiger was pulled to pieces and devoured by two large bears. Young cubs reared in confinement eat flesh readily, cooked or raw.

The bears have a peculiar habit of sucking their paws and of making a humming sound at the same time, and the present species is much addicted to the practice. According to Tickell some tame young bears that he saw would suck any person's hand in the same manner as their own paws.

The eyesight of Melursus ursinus is by no means good, and it has a peculiarly comical way of peering about for intruders, that gives the idea of its being short-sighted. Its hearing is also, I believe, far from acute. Its sense of smell is much better ; by scent it can detect honeycombs in a tree overhead, and nests of termites or larvae of beetles at some depth below the surface of the ground. In smelling about for food, for instance when visiting fruit-trees at night, it makes a peculiar puffing sound that can be heard at a considerable distance. Except in puffing and humming, the Indian bears are quite silent animals as a rule, and have no call for each other. Occasionally, however, they make the most startling noise, whether connected with pairing or not I cannot say. I have only heard it in the beginning of the cold season, which is not their usual pairing-time. They occasionally fight under fruit-trees, but I think the noise then made rather different.

When surprised or disturbed, and especially when wounded, a bear is generally very noisy, uttering a series of loud guttural sounds. When hit by a bullet it is far more demonstrative than a tiger ; indeed I have more than once known a tiger to receive a bullet without a sound, but I never knew a bear to be hit without much howling. Besides this, when a bear is mortally wounded and lies dying he almost always makes peculiar wailing cries. This has been observed by McMaster.

If two or more bears are together and one is wounded, a fight generally ensues, which Sanderson considers due to an attack by the unwounded animal or animals ; but this is not necessarily the case, as I have seen an old female when hit attack two halfgrown cubs that were with her, and cuff them heartily, and in one instance, when both of two bears were hit, they stood up on their hind legs and fought till one dropped dead from the bullet-wound.

As a rule the sloth-bear is a timid animal, but occasionally it attacks men savagely, using both its claws and teeth, and especially clawing the head and face. Sometimes, especially when surprised suddenly and attempting to escape, a bear merely knocks a man down with a blow of its claws, often, however, inflicting severe wounds ; but in other cases it holds its victim with its claws and bites him severely, not leaving him until some time after he ceases to struggle. Many of the most savage attacks are made by female bears that have young with them, some are by wounded animals, but occasionally the onslaught appears quite unprovoked. The story of sloth-bears hugging is, I think, unknown to the natives of India, and is only repeated by those whose ideas on the subject are derived from European folk-lore.

There are, however, many folk-lore stories connected with the Indian bear. It is a common belief in parts of India that male bears abduct women. It is possible that the name of Adam-zad is connected with this story. The same belief exists in Baluchistan regarding U. torquatus.

Sportsmen in India generally either drive patches of jungle or hills, and shoot the bears as they run out, or else mark them down in the morning, and go up to their lair on foot. Elephants are seldom used, they have a great dread of bears, and are but rarely steady with them, and the country is frequently too rough and rocky for the sport. When bears inhabit hills, sportsmen occasionally post themselves before daybreak in a commanding spot, and intercept the animals on their return from their nocturnal rambles. Bears are occasionally speared from horseback, and have sometimes been hunted with large dogs and killed with a knife when seized. This is described by Sanderson. Jerdon gives an account of a curious method of hunting with dogs, practised by the Polygars among the hills in the extreme south of the Peninsula. When the bear is brought to bay, the hunters each thrust a long bamboo loaded with strong bird-lime into the shaggy coat of their quarry, and thus hold him firmly. Nets have also been employed.

A wounded bear usually escapes without attempting to fight, and, unless he can get into a cave, runs away until he drops, no matter what the temperature may be, frequently going many miles. Occasionally, however, he charges desperately, but a shot in the face, whether it hits or not, will almost always turn him.

There is a common idea, quite unfounded, that a bear always rises on its hind legs to attack, and may then be shot in the chest. It very rarely, if ever, does this when really angry and assailing an enemy already clearly recognized. The act of rising on the hind legs is generally due to surprise, and to an endeavour, on the part of the bear, to make out his enemy better.

The pairing-time appears to vary, but is generally about June, at the commencement of the monsoon. The period of gestation is said by Tickell to be seven months ; if so, it rather exceeds that of other bears. The young are born at various times from October till February, but most often in December or January ; they are usually two in number, the size of Newfoundland pups, are blind for the first three weeks (18 days according to McMaster), and are covered with soft, short hair, which after a couple of months becomes rougher and coarser. After a time (2 or 3 months I believe) the mother takes them with her, carrying them on her back, where they cling to the long hair. They ride thus, at times, until of tolerable size ; one cub may sometimes be seen following its mother whilst the other is carried. They take between two and three years to reach maturity, and generally remain with the mother till full-grown. Sloth-bears have been known to live in captivity for 40 years. They are, when taken young, easily tamed, and, although fretful and querulous at times, generally playful, amusing, good-tempered, and much attached to their masters."

[Quelle: Blanford, W. T. <1832 – 1905>: Mammalia. -- 1888 - 1891. -- (Fauna of British India including Ceylon and Burma). -- S. 201 - 205. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/mammalia00blaniala. -- Zugriff am 2007-09-06]

Sanderson:

"THE INDIAN BLACK BEAR (URSUS LABIATUS).

DESCRIPTION OF HABITS AND DISPOSITION - SHE-BEARS CARRYING THEIK CUBS -

WOUNDED BEARS ATTACKING EACH OTHER - FOOD - BEARS DRINKING HENDA EATING FLESH - DANGER OF MEETING BEARS - MODES OF HUNTING BEARS

This is the common bear of India and Ceylon : it is sometimes called the sloth bear. It is found from the extreme south of India to the Ganges. Two other species occur in the Himalayas, but Ursus labiatus is the only one inhabiting the plains. It does not hibernate, and though covered with so thick a coat seems quite at home in the hottest localities.

The hair is black, coarse, and shaggy ; the muzzle and tip of feet whiteybrown ; and a crescent-shaped mark on the breast in sportsman's parlance the horse-shoe is white or yellowish in different individuals.

The largest bear I ever killed weighed exactly 20 st., stood three feet high at the shoulder, and approached six feet in length.

Bears have formidable claws, four inches in length, with which they dig for insects. The sole of the foot is very like that of a man's in shape, but shorter and broader ; and the print left by it is sufficiently like a man's to admit of a mistake being made regarding it by any one unaccustomed to tracking.

The male and female bear frequently live together, except when the female has cubs. Three bears are not unfrequently found in company, in which case it is usually a mother and two large cubs. The female has two, sometimes, I believe, three, young at a birth, and often carries them on her Lack during her travels. It is an amusing sight to see the youngsters dismount at the feeding-grounds and scramble up again if anything alarms them. The young are thus carried on occasions until they are several months old, and so large that only one can be accommodated. I once shot a she-bear carrying one young one whilst the other followed, through a thicket where it was a wonder the young bear, which was as large as a sheep-dog, could keep its seat.

Bears are exceedingly affectionate animals amongst themselves, and are capable of being most thoroughly tamed when taken young. Either wild or tame they are very amusing in their ways, being exceedingly demonstrative and ridiculous. Though hard to kill they are very soft as to their feelings, and make the most hideous outcries when shot at, not only the wounded animal but also its companions. It has frequently been stated by sportsmen that if a bear be wounded he immediately attacks his companions, thinking that they have caused his injuries. But I think this is not quite correct, at least in the majority of cases. I have observed that a wounded bear's companions generally rush to him to ascertain the cause of his grief, joining the while in his cries, when he, not being in the best of humours, lays hold of them, and a fight ensues, really brought about by the affectionate but ill-timed solicitude of his friends.

Bears are numerous in some parts of Mysore, especially in the jungles at the foot of hill-ranges, where they find shelter in small detached hills. Those in Mysore are frequently formed of granite boulders, amongst which are numerous caverns and cool recesses. Bears will, however, lie out in the forest, at the foot of a bamboo-clump or shady tree, or in a thicket. They retire to caves chiefly in the rains, when mosquitoes and gnats are troublesome in the thickets. In localities where they are not liable to be disturbed, bears sometimes sleep daring the day in very exposed situations, and do not mind an amount of sun that would be thought disagreeable to creatures with so warm a coat. They are usually in their retreats by eight o'clock in the morning, and are again on the move an hour before sunset. In showery, cloudy weather, especially at the commencement of the rains, when they have been put to straits to obtain a livelihood during the hot months, owing to the hardness of the ground preventing their digging for insects, they may be found feeding throughout the day in quiet places.

Their sight is poor, nor is their hearing particularly good, and when engaged in searching for food they may be approached to within a few paces. But their sense of smell is wonderfully acute ; by it they discover insects deep under ground, honey in trees overhead, and are able to detect a man to windward at an immense distance.

The food of the bear consists chiefly of black and white ants, whose underground colonies he is ever attacking ; the larvae of large beetles ; and fruit. He is particularly fond of the pods of the Cassia fistula (a very common shrub in the Mysore jungles), which contain a sweet black gum between the seeds, of a highly laxative character. Bears are fond of sugarcane, jak fruit, and melons. In some places they are troublesome in the groves of wild date-trees (Phoenix sylvestris), from which henda the fermented sap of the tree is obtained. The date-trees are seldom more than twenty feet high ; the bears climb them, and by tipping up the pot in which the juice is collected with their paws they manage to drink its contents. The henda-drawers would not begrudge them a few quarts, but they break a large number of pots by their clumsiness before they get what they require. The natives are unanimous in asserting that the bears drop down backwards instead of taking the trouble to climb down, and that they constantly get drunk with their potations. This seems not unlikely from the manner in which monkeys and other animals are affected by strong drinks. Bears are also very fond of the fruit of the date-palm, which they find on the ground under the trees, and of honey when they can obtain it.

Ursus labiatus is usually believed to be non-carnivorous, but I have known of one case of a bear devouring a jungle-sheep (muntjac-deer), which one of

my men had shot and left in the jungle overnight, being unable to carry it home. It rained heavily before morning, so there was no mistaking the footmarks of the marauder, which might otherwise have been supposed to have been a panther or hyaena. I have seen where bears have gnawed the dry bones of cattle that have died in the jungles. They do not. however, attempt to kill any animals for food, and their eating flesh at all is decidedly exceptional.Bears are dangerous to an unarmed man. Woodcutters and others, whose avocations take them into the jungles, are frequently roughly handled by them. They are most dangerous, like all wild animals, if suddenly stumbled upon, when their natural timidity leads to their becoming the aggressors. Perhaps fewer accidents occur under such circumstances of sudden meetings from tigers and panthers than any other animals ; they are naturally quickwitted, and not so much embarrassed by an unexpected encounter as some other creatures. The blundering fear of a suddenly aroused bear is distinct from any fierceness of disposition. Bears are very peaceable if left alone, and even when wounded and sorely provoked frequently behave in a pusillanimous manner. Injuries inflicted by them are less commonly fatal than from the Felidae.

The usual methods of hunting the bear are, driving him with beaters if in jungle, or sitting over his cave at daybreak and shooting him on his return from his night's wanderings if his quarters are amongst rocks. In the forests about Morlay I always shot bears by following them with trackers. As they seldom ceased feeding in wet weather before 9 A.M., if we hit off a trail early in the morning we could generally catch the animal up before it retired for the day. There were no caves of any magnitude, and the bears were generally found lying under the shelter of a rock or bamboo clump, if not overtaken whilst yet afoot. Tracking is most easy in September and October, when the grass is about two feet high and the dews heavy. A bear leaves a very plain trail through this."

The sleeping beauties awakened.[Quelle: Sanderson, G. P. (George P.): Thirteen years among the wild beasts of India: their haunts and habits from personal observations; with an account of the modes and capturing and taming elephants. -- 5th ed. -- London, W. H. Allen, 1893. -- xviii, 387 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- S. 365 - 368. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/thirteenyearsamo00sand. -- Zugriff am 2007-09-14. -- Dort weiteres über den Lippenbären.]