Zitierweise | cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Manusmṛti. -- Kapitel 2. -- 1. Vers 1 - 25. -- Fassung vom 2008-09-25. -- http://www.payer.de/manu/manu02001.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2008-09-20

Überarbeitungen: 2008-09-25 [Verbesserungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung HS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Verse sind, wenn nichts anderes vermerkt ist, im Versmaß Śloka abgefasst.

Definition des Śloka in einem Śloka:

śloke ṣaṣṭhaṃ guru jñeyaṃ

sarvatra laghu pañcamam |

dvicatuṣpādayor hrasvaṃ

saptamaṃ dīrgham anyayoḥ |

"Im Śloka ist die sechste Silbe eines Pāda schwer, die fünfte in allen Pādas leicht

Die siebte Silbe ist im zweiten und vierten Pāda kurz, lang in den beiden anderen."

Das metrische Schema ist also:

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉ ̽

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ ̽

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉ ̽

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ ̽

Zur Metrik siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Einführung in die Exegese von Sanskrittexten : Skript. -- Kap. 8: Die eigentliche Exegese, Teil II: Zu einzelnen Fragestellungen synchronen Verstehens. -- Anhang B: Zur Metrik von Sanskrittexten. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/exegese/exeg08b.htm

vidvadbhiḥ

sevitaḥ sadbhir

nityam adveṣarāgibhiḥ

|

hṛdayenābhyanujñāto

yo dharmas taṃ

nibodhata |1|

1. Erkennt den Dharma1, der immer beachtet und im Herzen gutgeheißen2 wurde von den Wissenden3, Guten, die frei sind von Hass und Leidenschaft4.

Erläuterungen:

1 dharma: von Wz. dhar = festhalten. dharma ist das, was fest ist und fest hält (was die Welt im Innersten zusammenhält), entspricht also der lex naturae, dem Naturgesetz in physischer und moralischer Bedeutung. Deshalb dharma = moralisches und religiöses Gesetz, Religion, Wirklichkeit (z.B. die dharmas der Buddhistischen Scholastik), Natur, Buddhalehre (als Wiedergabe der Gesetzmäßigkeiten, die Erlösung als Option erlauben).

Medhātithi:

|

"The term 'dharma' as already explained denotes the performance of the Aṣṭaka and such other prescribed acts. External philosophers regard as 'dharma' also such acts as the wearing of ashes, the carrying of begging-bowls, and so forth;—and it is 'with a view to exclude these from the category of 'Dharma' that the author adds the qualifications —'followed by the learned,' and so forth." [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 158f.] |

2 im Herzen gutgeheißen

Medhātithi:

|

"The present statement refers to the following three cases :—

Other people explain this verse as serving the purpose of providing a general definition of 'Dharma'; the sense being—' that which is done by such persons should be regarded as Dharma' ; this definition is applicable to all forms of Dharma,—that which is directly prescribed by the Veda, that which is laid down in the Smṛti and also that which is got at from Right Usage. In accordance with this explanation, however, the right reading would be—'yaḥ etaiḥ sevyate taṃ dharmam nibodhata.' [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 161f.] |

3 Wissenden

Medhātithi:

|

"The 'learned' are those whose minds have been cultured by the study of the sciences ; those that are capable of discerning the real character of the means of knowledge and the objects of knowledge. The 'learned' (meant here) are those who know the real meaning of the Veda, and not others. In fact those persons that admit sources other than the Veda to be the 'means of knowledge' in regard to Dharma are 'unlearned,' 'ignorant'; in as much as their notions of the means and objects of knowledge are wrong. That this is so, we learn thoroughly from Mīmāṃsā (Sūtra, Adhyāya I)." [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 159.] |

4 die frei sind von Hass und Leidenschaft: nach Medhātithi dient das zur Abgrenzung gegenüber den Heterodoxen (Buddhisten usw.):

|

"' Who are free from love and hate'—What is referred to here is another cause that leads men to take to heterodox dharmas. ' Delusion' having been already described (as leading to the same end), the present phrase serves to indicate greed and the rest; the direct mention of 'love and hate' being meant to be only illustrative; e.g., it is by reason of Greed that people have recourse to magical incantations and rites. Or 'Greed' may be regarded as included (not merely indicated) by 'Love and Hate.' People who are too much addicted to what brings pleasure to themselves, on finding themselves unable to carry on their living by other means, are found to have recourse to such means of livelihood as the assuming of hypocritical guises and so forth. This has been thus described—' The wearing of ashes and carrying of begging bowls, being naked, wearing of discoloured clothes—these form the means of living for people devoid of intelligence and energy.'" [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 159] |

2. Nicht gepriesen wird, dass etwas als Wesen Begierde hat. Und auf dieser Welt gibt es keine Freiheit von Begierde, denn das Studium des Veda ist begehrlich und ebenso vom Veda vorgeschriebenes Handeln.

Erläuterungen:

1 Dies ist ein Einwand (ākṣepa, pūrvapakṣa): Dharma ist weder möglich noch nötig, da alles aus dem Puruṣartha (Lebensziel) kāma (Begierde) entspringt. dharma, artha, kāma (trivarga) sind die drei Lebensziele des Menschen (puruṣārtha), als viertes kommt bei den indischen Erlösungsreligionen noch mokṣa - Erlösung dazu.

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"II. 2. Āp. I, 6, 20, 1-4. 'Is not laudable,' because such a disposition leads not to final liberation, but to new births' (Gov., Kull.)." |

saṃkalpamūlaḥ

kāmo vai

yajñāḥ saṃkalpasaṃbhavāḥ

|

vratāni yamadharmāś ca

sarve saṃkalpajāḥ

smṛtāḥ |3|

3. Fürwahr: Begierde wurzelt in Zielvorstellung1, Opfer entstehen aus Zielvorstellung, ebenso Gelübde und religiöse Selbstzügelung -- alle entstehen aus Zielvorstellung.

Erläuterungen:

Dieser und der nächste Vers sind die Begründung des Einwands.

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"3. Nand. takes the beginning of the verse differently, 'The desire for rewards is the root of the resolve to perform an act' (saṃkalpa). 'Vows,' i.e. 'acts to be performed during one's whole lifetime, like those of the Snātaka' (chap. IV), Medh., Gov., Nār; 'the vows of a student,' Nand.; 'the laws prescribing restraints,' i.e. 'the prohibitive rules, e. g, those forbidding to injure living beings,' Medh., Gov., Nar.; 'the rules affecting hermits and Saṃnyāsins,' Nand. Kull. refers both terms to the rules in chap. IV." |

1 saṃkalpa: Vorstellung und Absicht, entspricht vielleicht am ehesten dem deutschen Begriff "Zielvorstellung"

akāmasya

kriyā kācid

dṛśyate neha karhicit |

yad

yad dhi kurute kiṃcit

tat tat kāmasya ceṣṭitam

|4|

4. In dieser Welt gibt es niemals irgend eine Tat, die ohne Begierde getan wird. Was auch immer jemand tut, ist von Begierde getrieben.

teṣu

samyag vartamāno

gacchaty amaralokatām |

yathā

saṃkalpitāṃś ceha

sarvān kāmān

samaśnute |5|

5. Wer sich in diesen Begierden recht verhält1, der wird in einer Unsterblichen-Welt2 wiedergeboren; und auch in dieser Welt erlangt er alle Sinnesgenüsse wie er sie sich vorgestellt und beabsichtigt hat.

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"5. 'In the right manner,' i.e. 'as they are prescribed in the Vedas and without expecting rewards.' ' The deathless state,' i.e. 'final liberation.'" |

1 Wer sich gegenüber diesen Begierden recht verhält: dies ist die Antwort auf den Einwand (siddhānta, samādhāna): der Einwand stimmt was die Geleitetheit durch Begierde betrifft, dharma leitet aber dazu an, sich gegenüber diesen Begierden recht (samyag) zu verhalten.

Medhātithi:

|

"To the above Pūrvapakṣa, the Author replies in this verse. [What is meant is that] one should behave in the right manner in regard to these-—desires. "What is this right behaviour?" It consists in doing an act

exactly in the manner in which it is found mentioned in the

scriptures. That is, in regard to the compulsory acts one should

not think of rewards at all, for the simple reason that no

rewards have been mentioned in connection with them; while in

regard to the voluntary acts, there is no prohibition of thinking

of rewards, for the simple reason that these acts are actually

mentioned as bringing definite rewards ; in fact what we know of

these acts from [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 169f.] |

|

"The Brahmavādins (Vedāntins) however regard the words 'it is not right to be absorbed in desires' as a prohibition of the Saurya and all such other acts as are laid down as bringing rewards ; and their reason is that all actions done with a view to rewards become setters of bondage; and it is only when an act is done without any thought of rewards—doing it simply as an offering to Brahman—that the man becomes released. This is what the revered Kṛṣṇa-Dvaipyana has declared in the words

[Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 171.] |

2 Medhātithi:

|

"By doing so [i.e., by behaving rightly in regard to desires] one goes to—attains—the position of Immortals, ' Immortals ' are the Gods ; their 'position' is Heaven ; and by reason of the Gods residing in Heaven, the term 'position' is applied to the gods themselves, the position being identified with the occupier of the position ; just as we have in the expression 'the elevated sheds are shouting' [where the 'sheds' stand for the men occupying them]. Hence the compound 'Amaraloka' is to be expounded as a Karmadhāraya—'the immortal positions'; and with the abstract affix 'tal' we have the form 'amaralokatā,' So the meaning is that 'he obtains the character of a divine being,' 'he attains divinity.' The author has made use of this expression in view of metrical exigencies. Or, the compound 'amaralokatā' may be explained as one who sees—' lokayati'-—the gods—'amarān' ; the term 'loka' being derived from the root 'loka' with the passive affix 'aṇ' (according to Pāṇini 3.2.1) ; and then the abstract affix tal added to it; so that the meaning is that 'he becomes capable of seeing the Gods'; and this also means that he attains heaven. Or again, the expression may mean that 'he is looked upon as a God'—'amara iva lokyate' -among men. This whole passage is mere

declamatory Arthavāda; and it does not lay down Heaven as

the result actually following from the action spoken of ; because

as a matter of fact, the compulsory acts do not lead to any

results at all, while the voluntary acts are prescribed as

leading to diverse results. So that what the 'attaining of

heaven' spoken of in the text means, is the due In the manner above described we have set aside the difficulty (that had been set up by the Pūrvapakṣa); for what the text prohibits is not the desire for each and everything, but the entertaining of desires only in connection with the compulsory acts; and in regard to these also there must be desire for the obtaining of things necessary for the due performance of them." [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 170f.] |

vedo

'khilo dharmamūlaṃ

smṛtiśīle ca

tadvidām |

ācāraś caiva sādhūnām

ātmanas tuṣṭir eva ca |6|

6. Wurzel des Dharma1 ist

der ganzen Veda2

die Überlieferung und die Sitte der Vedakundigen

das Verhalten der Guten

die Zufriedenheit der Seele3

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"6. Āp. I, I, I, 1-3; Gaut. I, 1-4; XXVIII, 48; Vas. I, 4-63; Baudh. I, I, I, 1-6 ; Yājñ. I, 7. Śīla, 'virtuous conduct,' i.e. 'the suppression of inordinate affection and hatred,' Medh., Gov. ; ' the thirteenfold Śīla., behaving as becomes a Brahmawa, devotedness to gods and parents, kindliness,' &c., Kull. ; ' that towards which many men who know the Veda naturally incline,' Nar. ; 'that which makes one honoured by good men,' Nand. ' Customs,' e. g. such as tying at marriages a thread round the wrist of the bride (Medh., Gov.), wearing a blanket or a garment of bark (Kull). Though the commentators try to find a difference between śīla and ācāra, it may be that both terms are used here, because in some Dharma-śātras, e.g. Gaut. I, 2, the former and in some the latter (e.g. Vas. I, 5) is mentioned. The 'self-satisfaction,' i.e. of the virtuous (Medh., Gov., Nand.), is the rule for cases not to be settled by any of the other authorities (Nar., Nand.), or for cases where an option is permitted (Medh., Gov., Kull.)." |

1 Dharma:

Medhātithi:

|

"The term 'dharma' we have already explained above; it is that which a man should do, and which is conducive to his welfare, and of a character different from such acts as are amenable to perception and the other ordinary means of knowledge. Land-cultivation, service, &c, also are conducive to man's welfare ; but this fact of their being so beneficial is ascertained by means of positive and negative induction ; and as regards the sort of cultivation that brings a good harvest of grains, this is ascertained by direct perception and other ordinary means of knowledge. On the other hand, the fact of sacrifices being conducive to welfare, and the manner in which they are beneficial, through the intervention of the 'Apūrva,'—all this is not amenable to perception or other ordinary means of knowledge. 'Welfare' is that which is, in its most general form, spoken of as ' pleasure,' consisting of the attaining what is desirable, in the shape of Heaven, landed property and so forth, and also (b) the avoiding of what is generally spoken of as 'pain,' which consists of illness, poverty, unhappiness, Hell and so forth. Others regard the attaining of Supreme Bliss only as 'welfare.'" [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 181.] |

2 Veda:

Medhātithi:

|

"[The opponent raises an initial objection]-—" What is the relevancy of what is stated in this verse ? It is Dharma that has been declared as the subject to be described ; and Dharma can be described only by means of Injunctions and Prohibitions. Now as regards the fact of the Veda being the source of Dharma, this cannot form the subject of any injunction such as 'the Veda should be known as the source of Dharma, as the authoritative means of ascertaining Dharma' ; because this fact can be known without its being enjoined in so many words; certainly the fact of the Veda being the source of Dharma does not stand in need of being notified by any injunctions of such writers as Manu and others ; in fact the authoritativeness of the Veda regarding matters relating to Dharma is as self-evident as that of Direct Perception,—being based upon the facts that

" It might be argued that—' what the text does is to refer to the well-established fact of the Veda being authoritative, with a view to indicate that the Smṛtis of Manu and others are based upon the Veda.' "But this explanation cannot be accepted. For this fact also does not need to be stated ; as

[...] Our answer to the above objection is as follows :— The authors of treatises on Dharma proceed to compose their works for the expounding of their subject for the benefit of such persons as are not learned (in the Vedas). Hence it is that having themselves learnt from the Veda that the Aṣṭakā and such other acts should be performed, they incorporate in their own work the injunctions of these acts, for the purpose of conveying the same knowledge to others ; similarly in the case of such matters as the authoritative character of the Veda [which are known by the Smṛti-writers themselves from the Veda, and yet they proceed to include that information in their work for the edification of persons not equally learned]. As a matter of fact, there are many enquirers who are incapable of ascertaining truth by means of independent reasoning,—not being endowed with an intellect capable of ratiocination ; and for the benefit of these persons even a logically established fact is stated by the writers in a friendly spirit. Hence what is herein stated regarding Veda being the source of Dharma is a well-established fact. What the statement 'Veda is the source of Dharma' means is that 'the fact of Veda being the source of Dharma has been ascertained after due consideration, and one should never doubt its authoritative character.' Even in ordinary experience we find people teaching others facts ascertained by other means of knowledge ; e.g. [when the physician teaches]—' you should not eat before the food already taken has been digested, for indigestion is the source of disease.' It cannot be rightly urged that "those who are unable to comprehend, by reasoning, the fact of Veda being the source of Dharma, can not comprehend it through teaching either" ; for as a matter of fact we find that when certain persons are known to be 'trustworthy,' people accept their word as true, without any further consideration. The whole of the present section therefore is based on purely logical facts, and not on the Veda. In other cases also,—e.g., in the case of Smṛtis dealing with law-suits, &c.—what is propounded is based upon logic, as we shall show later on, as occasion arises. How the performance of the Aṣṭakā, etc., is based upon the Veda we shall show in the present context itself. The word 'Veda' here stands for the Ṛg, Yajus and Sāman, along with their respective Brāhmaṇas; all these are fully distinguished, by students, from all other sentences (and compositions). Learners who have their intellect duly cultured through series of teachings, understand, as soon as a Vedic passage is uttered, that it is Veda,—their recognising of the Veda being as easy as the recognition of a man as a Brāhmaṇa. This word 'Veda' is applied to the whole collection of sentences,—beginning with 'Agnim īḷe purohitam,' 'Agnir vai devānāṃ varṇa,' and ending with ' Samsamidy uvase,' 'atha mahāvāratam' (Ṛgveda); as also to the several individual sentences forming part of the said collection; and this application of the word is not direct in the one case and indirect in the other,—as is the case with the word 'village' as applied (directly) to the entire group of habitations, and (indirectly) to each individual habitation. [...] This Veda is variously divided. The Sāma Veda is said to have a thousand 'paths' (i.e., Recensions), in the shape of 'Sātya, 'Mugri,' 'Rāṇāyanīya' and so forth ; there are a hundred Recensions of the Yajurveda, in the shape of 'Kāṭhaka' 'Vājasaneyaka' and the rest ; there are twenty-one Recensions of the Ṛgveda ; and nine of the Atharva Veda in the shape of 'Modaka' 'Paippalādaka,' and so forth. [ Objection]—"No one regards the Atharva as a Veda :

[all these speak of only three Vedas]. In fact we also find a prohibition regarding the Atharva—' One should not recite the Atharvaṇas.' It is in view of all these that people regard the followers of the Atharvaṇa as heretics, beyond the pale of the Vedic Triad." [Answer]—This is not right; all good men agree in regarding the Atharvaṇa as a Veda. In this Smṛti itself (11.33) we find the expression 'śrutīr atharvāṅgirasīḥ,' where the Atharva is spoken of as 'śruti,' and 'śruti' is the same as 'Veda.' Further [whether a certain Veda is called 'Veda' or not is of no import] ; when certain passages—e.g., those prescribing the Agnihotra and other sacrifices, which all people call 'Veda'—are regarded as authoritative in matters regarding Dharma, they are so accepted, not because they are called by the name of 'Veda';—because the name ' Veda' is sometimes applied to Itihāsa and the Āyurveda also, when, for instance, it is said that 'Itihāsa and Purāṇa are the fifth Veda' (Chandogya Upaniṣad, 7.1.2), [and yet these are not regarded as authorities on Dharma] ;—but because they are independent of human agency, and help to make known our duties, and because they are free from mistakes; and all these conditions are fulfilled by the Atharva: such acts as the Jyotiṣṭoma and the like are prescribed in the Atharva just as they are in the Yajus and the other Vedas. Some people have fallen into the mistake that the Atharva cannot be Veda because it abounds in teachings of acts dealing with malevolent magic (witchcraft). As a matter of fact, malevolent magic, as leading to the death of living beings, is always prohibited. [It is described, because] it is employed by the priests of kings who are well versed in magical spells ; but it is deprecated." [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 172f., 176f., 179] |

|

"It might be asked why no reason has been given [by Manu, why and how the entire Veda is the root of Dharma] ; but our answer is that this is a work in the form of Precept, and as such states well-established conclusions ; and those persons who seek after the 'why' and 'wherefore' of these conclusions are instructed by Pūrvamīmāṃsā. We have already said that this work is addressed to persons who are prepared to learn things from Precept alone." [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 187.] |

3 die Zufriedenheit der Seele: dies entspricht in etwa dem westlichen Begriff des (gebildeten!) Gewissens (conscientia)

Medhātithi:

|

"'ātmanas tuṣṭir eva ca',—'Self-satisfaction also'—' is source of Dharma' is to be construed here also. This ' self-satisfaction' also is meant to be of those only who are ' learned in the Veda and Good' ('Vedavidāṃ sādhūnām'). The fact of this 'Self-satisfaction' being 'source of Dharma' has been held to he based upon the trustworthy character (of the people, concerned). When such persons as are possessed of the stated qualifications (of being good and learned) have their mind satisfied with a certain act, and they do not feel any aversion towards it, that act is 'Dharma.' "But it may happen that a man's mind is satisfied with a prohibited (sinful) act; and this would have to be regarded as Dharma. Again, a man may have hesitation (and doubt) regarding what is enjoined in the Veda ; and this latter would have to be regarded as not 'Dharma.' "

[Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 206ff.] |

yaḥ

kaścit kasyacid

dharmo manunā parikīrtitaḥ

|

sa sarvo 'bhihito vede

sarvajñānamayo hi saḥ

|7|

7. Was für wen von Manu verkündeter Dharma ist, das alles ist im Veda mitgeteilt, denn dieser besteht und stammt1 aus Allwissen.

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.): bezieht das Allwissen auf Manu und übersetzt: "for that (sage was) omniscient"

|

"7. The last clause is taken differently by Gov., who explains it, 'for that (Veda) is made up, as it were, of all knowledge.' Medh. gives substantially the same explanation." |

1 besteht und stammt aus Allwissen: sarvajñānamaya entsprechend der doppelten Bedeutung des Suffixes -maya (bestehen aus, stammen von) doppelt übersetzt

sarvaṃ

tu samavekṣyedaṃ

nikhilaṃ jñānacakṣuṣā

|

śrutiprāmāṇyato vidvān

svadharme

niviśeta vai |8|

8. Fürwahr: Der Wissende/Vedakundige soll all das mit dem Auge der Erkenntnis betrachten und dass seinen eigenen Dharma angehen nach Maßgabe der Śruti (des Veda).

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"8. 'All this,' i.e. 'the śāstras' (Medh., Gov., Kull.); 'these Institutes of Manu' (Nar.) ; ' these different authorities' (Nand.). 'With the eye of knowledge,' i. e. ' with the help of grammar, of the Mīmāṃsā, &c.' (Medh., Kull.)." |

śrutismṛtyuditaṃ

dharmam

anutiṣṭhan hi mānavaḥ |

iha

kīrtim avāpnoti

pretya cānuttamaṃ sukham |9|

Denn ein Manu-Nachkomme, der den Dharma befolgt, der in Śruti und Smṛti genannt wird, erlangt in diesem Leben Ruhm und nach dem Weggang1 höchstes Glück.

Erläuterungen:

1 = Tod

śrutis

tu vedo vijñeyo

dharmaśāstraṃ tu vai

smṛtiḥ |

te sarvārtheṣv amīmāṃsye

tābhyāṃ dharmo hi nirbabhau |10|

10. Unter "Śruti" ist der Veda zu verstehen, "Smṛti" ist das Dharmalehrwerk. Diese beiden darf man unter keinen Umständen kritisieren1, denn aus ihnen ist der Dharma erschienen.

Erläuterungen:

1 kritisieren:

Medhātithi:

|

"Question :—"What is that common function of Revealed Word and Recollection which the present verse seeks to attribute to the Practices of Cultured Men?" Answer :—'In all matters these two should not be criticised' ;—'These two'—i.e., Revealed Word and Recollection. —'In all matter's'—i.e., even in regard to apparently inconceivable things, such as are entirely beyond the scope of those means of knowledge that are applicable to perceptible things ; e.g.,

In such matters, we should not proceed to discuss the various pros and cons. 'Criticism' consists in raising doubts and conceiving of contrary views. For example—-"If the act of killing is sinful, then since the act of killing is the same in all cases, that done in the course of Vedic sacrifices should also he sinful;—if the latter killing is a source of good, ordinary killing also should be conducive to good; the act being exactly the same in both cases." "What is prohibited here is that 'criticism,' in which we conceive of the form of an act to be quite the reverse of what is declared in the Veda, and proceeding to examine it by means of reasonings based upon false premisses, begin to insist on the conclusion thus arrived at. It is not meant to prohibit such enquiry and discussion as to whether the Prima Facie View or the Established Thesis is in due accord with the Veda. That such an inquiry is not meant to be prohibited is clear from what the author says later on—'He alone, and none else, knows Dharma, who examines it by reasonings.' (Manu, 12.106)" [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 212f.] |

yo

'vamanyeta te mūlea

hetuśāstrāśrayād

dvijaḥ |

sa sādhubhir bahiṣkāryo

nāstiko

vedanindakaḥ |11|

a Olivelle: tūbhe (aber diese beiden)

11. Wenn ein Zweimalgeborener diese beiden Wurzeln verachtet indem er sich auf heterodoxe Lehrwerke1 stützt, dann müssen ihn die Guten exkommunizieren als Ungläubigen und Veda-Verspötter.

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"11. 'Relying on the Institutes of dialectics,' i.e. 'relying on the atheistic institutes of reasoning, such as those of the Bauddhas and Cārvākas' (Medh); 'relying on methods of reasoning, directed against the Veda' (Kull., Nār.)." |

1 heterodoxe Lehrwerke: hetuśāstra: wörtlich: Begründungs-Lehrwerke, Lehrwerke der Dialektik. Könnte sich auf die buddhistische Sophistik beziehen.

Medhātithi:

|

"On the ground of 'untruthfulness' and 'unreliability' if a twice-born person, relying upon the science of dialectics ;— the 'science of dialectics' here stands for the polemical works written by Atheists, treatises of Bauddhas and Carvākas, in which it is repeatedly proclaimed that "the Veda is conducive to sin" ;—relying upon such a science, if one should scorn the Veda ; i.e., when advised by some one to desist from a certain course of action which is sinful according to the Veda and the Smṛti, in the words—'Do not do this, it is prohibited by the Veda,'—if he disregards this advice and persists in doing it, saying, 'what if it is prohibited in the Veda or in the Smṛtis ? They are not at all authoritative';— even without saying this, if he should even think in this manner,—and if he is found to pay much attention to the science of dialectics ;—such a person should be east out by the good—despised by all cultured persons—out of such acts as 'officiating at sacrifices,' 'teaching,' 'honours of a guest' and so forth. Since the text docs not specify the acts (from which the man should be kept out), it follows that he should he kept out of all those acts that are fit for the learned. And the reason for this lies in the fact that it is only the ignorant man, whose mind is uncultured and who smacks of the polemic, that can speak as above (in deprecation of the Veda) ; and to the said acts (of officiating, etc.) it is only the learned man that can be entitled. It is in view of this that such 'criticism' has been prohibited in the preceding verse,—such criticism being due to want of respect,—and it does not deprecate such inquiry as might be instituted for the purpose of elucidating the true meaning of the Veda." [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 216f.] |

vedaḥ

smṛtiḥ sadācāraḥ

svasya ca priyam

ātmanaḥ |

etac caturvidhaṃ prāhuḥ

sākṣād dharmasya lakṣaṇam |12|

12. Der Veda, die Smṛti, das Verhalten der Guten und das was der eigenen Seele lieb ist -- dies ist das vierfache unmittelbare Kennzeichen1 des Dharma.

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"12. The first half of this verse agrees literally with Yājñ. I, 7." |

1 unmittelbare Kennzeichen

= selbstevidente Erkenntnisquelle

arthakāmeṣv

asaktānāṃ

dharmajñānaṃ

vidhīyate |

dharmaṃ jijñāsamānānāṃ

pramāṇaṃ paramaṃ śrutiḥ |13|

13. Für die, die nicht mit zweckrationalen Handeln und den Sinneslüsten beschäftigt sind, wird die Kenntnis des Dharma angeordnet. Für die, die den Dharma kennen wollen, ist das höchste Erkenntnismittel die Śruti (der Veda).

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

13. According to 'another' commentator, quoted by Medh., and according to Gov., Kull., and Nār., the meaning of the first half is, 'the exhortation to learn the sacred law applies to those only who do not pursue worldly objects, because those who obey (or learn, Nār.) the sacred law merely in order to gain worldly advantages, such as wealth, fame, &c., derive no spiritual advantage from it (because they will not really obey it,' Nār.). Medh., on the other hand, thinks that vidhīyate, ' is prescribed,' means ' is found with.'" |

śrutidvaidhaṃ

tu yatra syāt

tatra dharmāv ubhau smṛtau |

ubhāv

api hi tau dharmau

samyag uktau manīṣibhiḥ |14|

14. Wo die Śruti widersprüchlich ist, dort ist beides als Dharma überliefert. Denn beides ist auch von den Weisen richtig als Dharma benannt worden.

udite

'nudite caiva

samayādhyuṣite tathā |

sarvathā

vartate yajña

itīyaṃ vaidikī śrutiḥ

|15|

15. Dies ist eine vedische Śruti: Das Opfer1 findet jederzeit statt: nach Sonnenaufgang, vor Sonnenaufgang und während der Dämmerung2.

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"15. The Agnihotra, here referred to, consists of two sets of oblations, one of which is offered in the morning and the other in the evening. The expression samayādhyuṣite, rendered in accordance with Kull.'s gloss, 'when neither sun nor stars are visible,' is explained by Medh. as 'the time of dawn' (uṣasaḥ kālaḥ), or 'as the time when the night disappears,' with which latter interpretation Gov. agrees." |

1 Opfer: nämlich das Agnihotra-homa

2 samayādhyuṣite:

Medhātithi:

|

"By the compound word 'samayādhyuṣita' the time of early dawn is meant. Others have taken it as consisting of two words: 'samayā' meaning near, requires its correlative in the shape of something that is near ; and since the two points of time mentioned in the sentence are those 'before' and 'after sunrise,' the required correlative in the present instance is the time of twilight. 'Adhyuṣita' stands for the time of departure of the night, and means 'at the departure of night.' [So the compound means 'that twilight which comes after the departure of night.']" [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 225.] |

niṣekādiśmaśānānto

mantrair yasyodito vidhiḥ |

tasya śāstre

'dhikāro 'smiñ

jñeyo nānyasya kasyacit

|16|

16. Zu diesem Lehrwerk ist nur befugt, für wen für die Saṃskāras1 von Niṣeka2 bis zur Leichenverbrennung3 mit Mantras4 vorgeschrieben sind; kein anderer5.

Erläuterungen:

Bühler (S.B.E. z. St.):

|

"16. The persons meant are the males of the three Āryan varṇas. The sacraments may be performed for women and Śūdras also, but without the recitation of mantras (II, 66 ; X, 127)." |

1 Saṃskāras = Übergangsriten. Siehe zu Manu 2,26

2 Niṣeka = garbhādhāna

|

"Garbhādhāna :—The beginnings of this ceremony are found very early. Atharvaveda V. 25 appears to be a hymn intended for the garbhādhāna rite. Atharva V. 25. 3 and 5 are verses which occur in the Bṛ. Up. VI. 4. 21; the passage of the Bṛ. Up. VI. 4. 13, 19-22 may be rendered thus: ' At the end of

three days (after menstruation first appears) when she (wife )

has bathed, the husband should make her pound rice ( which is

then boiled and eaten with various other things according as he

desires a fair, brown or dark son or a learned son or a learned

daughter) … and then towards morning, after having

according to the rule of the Sthālīpāka performed

the preparation of the clarified butter, he sacrifices from the

Sthālīpāka little by little, [S. 202] saying '

This is for Agni, svāhā; this is for Anumati, svāhā;

this is for divine Savitṛ the true creator, svāhā

! Having sacrificed he takes out the rest of the rice, eats it

and after having eaten he gives some of it to his wife. Then he

washes his hands, fills a water jar and sprinkles her thrice with

water saying ' Rise, oh Viśvāvasu, seek another

blooming girl, a wife with her husband.' Then he embraces her and

says ' I am Ama, thou art Sā. Thou art Sā, I am Ama. I

am the Sāman, thou art the Ṛk. I am the sky, thou art

the earth. Come, let us strive together that a male child may be

begotten '

(VI. 4. 21-22 cannot be literally translated for reasons of decency). Briefly the husband

has intercourse with her and repeats certain mantras 'may Viṣṇu

make ready your private parts, may Tvaṣṭā frame

your beauty, may Prajāpati sprinkle and may Dhātā

implant an embryo into you ; Oh Sinīvāli ! Oh

Pṛthuṣṭukā ! implant embryo ( in her ),

may the two Asśins who wear a garland of lotuses plant in

thee an embryo … As the earth has fire inside it, as

heaven has Indra inside it, as the wind is inside (as the embryo

of) the quarters, so I plant a garbha in thee, oh, so and so (the

name of the woman being taken)'.

In the Āśv. gṛ. (I. 13. 1 ) it is expressly stated that in the Upaniṣad the ceremonies of Garbhālambhana (conceiving a child), Puṃsavana (securing a male child) and Anavalobhana (guarding against dangers to the embryo ) are mentioned. Evidently this is a reference to the Bṛ. Up. quoted above ( where four mantras used in the garbhādhāna saṃskāra by Hir. and other gṛhya sūtras occur ). The rite called caturthīkarma is described in the Śāṅkhāyana gṛ. (1.18-19, S. B. E. vol. 29, pp. 44-46) as follows "Three [S. 203]

nights after marriage having elapsed, on the fourth the husband

makes into fire eight offerings of cooked food to Agni, Vāyu,

Sūrya (the mantra being the same for all three except the

name of the deity ), Aryaman, Varuṇa, Pūṣan

(mantras being the same for these three), Prajāpati (the

mantra is Ṛg. X. 121. 10 ), to (Agni) Sviṣṭakṛt.

Then he pounds the root of Adhyaṇḍā plant and

sprinkles it into the wife's nostril with two verses ( Ṛg.

X. 85. 21-22) with svāhā at the end of each. He should

then touch her, when about to cohabit, with the words 'the mouth

of the Gandharva Viśvāvasu art thou '. Then he should

murmur 'into the breath I put the sperm, Oh ! so and so (the name

of the wife) or he repeats the verse' as the earth has fire

inside &c.' ( quoted above from Bṛ. Up, VI. 4. 22 ) or

several other verses in this strain ' may a male embryo enter thy

womb as an arrow into the quiver; may a man be born here, a son,

after ten months ".

The Pār. gṛ. (I. 11, S. B. E. vol. 29, pp. 288-290 ) also has a similar procedure. Āp. gṛ. ( 8. 10-11. S. B. E, vol, 30, pp. 267-268), Gobhila II. 5 ( S. B. E. vol. 30, pp. 51-52) give briefly a similar procedure, but refer to mantras given in the Mantrapāṭha ( e. g. Āp. M. P. I. 10. 1. to I. 11. 11 ). To modern minds it appears strange that intercourse should have been surrounded by so much of mysticism and religion in the ancient sūtras. But in ancient times every act was sought to be invested with a religious halo; so much so that according to Hir. gṛ. I. 7. 25. 3. (S. B. E. vol. 30, p. 200) Ātreya held that mantras were to be repeated at each cohabitation throughout life, while Bādarāyaṇa prescribed that this was necessary only at the first cohabitation and after each monthly course. The Hir. gṛ. ( I. 7, 23. 11 to 7, 25, S. B. E. vol. 30 pp 197-200) gives a very elaborate rite, but on the same lines as the above gṛhyasūtras. One of the mantras is interesting on account of its reference to the cakravāka birds (I. 7. 24. 6), 'The concord that

belongs to the cakravāka birds, that is brought out of the

rivers of which the divine Gandharva is possessed, thereby we are

concordant' (S. B. E. vol. 30, p. 198 ).

The Vaik. (III. 9 ) calls this ceremony ṛtusaṃgamana and is similar to Āp. gṛ. and Hir. gṛ. It will be seen that the [S. 204] caturthīkarma is treated by the gṛhya writers as part of the marriage rites and the rite was performed irrespective of the question whether it was the first appearance of menses or whether the wife had just before the marriage come out of her monthly illness. This indicates that it was taken for granted that the wife had generally attained the age of puberty at the time of marriage. As the marriageable age of girls came down it appears that the rite of caturthīkarma was discontinued and the rite was performed long after the ritual of marriage and appropriately named garbhādhāna. The smṛtis and nibandhas add many details some of which will have to be noticed. Manu (III. 46) and Yāj. I. 79 say that the natural period (for conception) is sixteen nights from the appearance of menses. Āp. gṛ. 9. 1 says that each of the even nights from the 4th to 16th (after the beginning of the monthly illness) are more and more suited for excellence of (male) offspring. Hārīta also says the same. These two appear to allow garbhādhāna on the fourth night, but Manu (III. 47 ), Yāj. ( I. 79) lay down that the first four nights must be omitted. Kātyāyana, Parāśara (VII. 17) and others say that a woman in her menses is purified by bathing on the 4th day. Laghu-Āśvalāyana (III. 1) says that the garbhādhāna ceremony should be performed on the first appearance of menses after the 4th day hat elapsed. The Sm. C. suggests that the 4th may be allowed if there is entire cessation of the flow. Manu ( IV. 128 ) and Yāj. I. 79 added further restrictions viz. that new moon and full moon days and the 8th and 14th tithis of the month were also to be omitted. Astrological details were added by Yāj. I. 80 (that the Mūla and Maghā constellations must be avoided and the moon must be auspiciously placed) and other later smṛtis like Laghu-Āśvalāyana III. 14-19 and in nibandhas like the Nirṇayasindhu and Dharmasindhu elaborate discussions are held about the months, tithis, week-days, [S. 205] nakṣatras, colour of clothes, that were deemed to be inauspicious for the first appearance of menses and about the śāntis (propitiatory rites) for averting their evil effects. Āp.gṛ., Manu (III. 48), Yāj. (T. 79), Vaik. III. 9 hold that a man desirous of male issue should cohabit on the even days from the 4th day after the appearance of menses and if he cohabits on uneven days a female child is born. Hir. gṛ. I. 7. 24. 8 (S. B. E. vol. 30 p. 199) and Bhāradvāja gṛ. (I. 20) prescribe that a woman in her menses who takes a bath on the 4th day should attire herself in white (or pure ) clothes, should ornament herself and talk with (worthy) brāhmaṇas (only). The Vaik. (III. 9) further adds that she should anoint herself with unguents, should not converse with a woman, or a śūdra, should see no one else except her husband, since the child born becomes like the male whom a woman taking a bath after the period looks at. Śaṅkha-Likhita convey a similar eugenic suggestion, viz. 'Women give birth to

a child similar in qualities to him on whomsoever their heart is

set in their periods.'

A debatable question is whether garbhādhāna is a saṃskāra of the garbha (the child in the womb) or of the woman. Gaut. VIII. 24, Manu. I. 16, and Yāj. I. 10 indicate that it is a saṃskāra of the garbha and not of the woman. Viśvarūpa on Yāj. I. 11 expressly asserts that all saṃskāras except Sīmantonnayana have to be performed again and again (as they are the saṃskāras of the garbha), while Sīmantonnayana being a saṃskāra of the woman has to be performed only once and this opinion was in consonance with the usage in his days. Laghu-Āśvalāyana (IV. 17 ) also holds the same view. Medhātithi on Manu II. 16 says that the garbhādhāna rite with mantras was performed after marriage only once at the time of the first cohabitation according to some, while according to [S. 206] others it was to be performed after every menstruation till conception. Later works like the Mit. (on Yāj. I. 11 ) the Sm. C, the Saṃskāratattva (p. 909) hold that garbhādhāna, puṃsavana and sīmantonnayana are saṃskāras of the woman and are to be performed only once and quote Hārīta in support. Aparārka holds that sīmantonnayana is performed only once at the first conception, while puṃsavana is repeated at each conception. He relies on Pār. gṛ. I. 15; and the Saṃskāra-mayūkha and the Saṃskāraprakāśa (pp. 170-171) hold the same opinion. Sm. C. (I. p. 17) quotes a verse of Viṣṇu that according to some even sīmantonnayana is repeated at each conception. About the rules for women who are rajasvalā (in their monthly course ) vide later on. According to Kullūka (on Manu II. 27), the Sm. C. (I. p. 14) and other works garbhādhāna is not of the nature of homa. The Dharmasindhu says that when garbhādhāna takes place on the first appearance of menses, homa for garbhādhāna is to be performed in the gṛhya fire, but there is no homa when the cohabitation takes place on the second or later appearance of menses; that those in whose sūtra no homa is prescribed should perform the garbhādhāna rite on the proper day after the first appearance of menses by reciting the mantras but without homa. The Saṃskārakaustubha (p. 59) relying on Gṛhyapariśiṣṭa prescribes homa in which cooked food is to be offered to Prajāpati and seven offerings of ājya are to be offered in fire, three with the verses ' Viṣṇur-yonim ' ( Ṛg. X. 184. 1-3 ). three with ' nejameṣa' ( Āp. M. P. I. 12. 7-9) and one with Ṛg. X. 121. 10 ( prajāpate na ). All saṃskāras other than garbhādhāna can be performed by any agnate in the absence of the husband (vide Saṃskāra-prakāśa p. 165)." [Quelle: [Kane, Pandurang Vaman <1880 - 1972>: History of Dharmasastra : (ancient and mediaeval, religious and civil law). -- Poona : Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. -- Vol. II,1. -- 2. ed. -- 1974. -- S. 201 - 206] |

3 Leichenverbrennung (śmaśāna): = antyeṣṭi

4 mit Mantras: dadurch werden Frauen ausgeschlossen (siehe Manu 2, 66)

5 kein anderer: d.h. kein Śūdra, geschweige denn ein "Dalit"

Medhātithi:

|

"Objection :—"When

the Śūdra is not entitled to study the scripture and

learn its meaning, how can he he entitled to the performance of

the acts therein prescribed ? Unless the man knows the exact form

of the act, he cannot do it; True; but the requisite knowledge can be obtained from the advice of other persons. The Śūdra may be dependent upon a Brāhmaṇa; or a Brāhmaṇa may he doing the work of instructing people for payment; and such a Brāhmaṇa might very well instruct the Śūdra to 'do this, after having done that' and so forth. So that the mere fact of the Śūdra performing the acts does not necessarily indicate that he is entitled to the study and understanding of the scriptures; as performance can be accomplished, even on the strength of what is learnt from others ; as is done in the case of women; what helps women (in the performance of their duties) is the learning of their husbands, which becomes available to them through companionship. Then again, the texts laying down the acts do not imply the direct knowledge (of the injunctive texts). It is only in the case of men, to whom is addressed the injunction of Vedic study—contained in the words 'one should study the Veda'—that the performance of duties proceeds upon the basis of their own learning ; and this injunction is meant only for the male members of the three higher castes. But in the case of these also their study and understanding of the scriptures is not prompted by their knowledge of what is contained in them ; it is prompted entirely by the two injunctions—(1) the injunction of having recourse to a duly qualified teacher, and (2) the injunction of Vedic study." [Übersetzung: Manu-smrti ; the laws of Manu with the bhāsya of Mēdhātithi / translated by Gangā-nātha Jhā [1871 - 1941]. -- [Calcutta] : University of Calcutta, 1920-26. -- Bd. III,1. -- S. 228f.] |

sarasvatīdṛśadvatyor

devanadyor yad antaram |

taṃ devanirmitaṃ deśaṃ

brahmāvartaṃ pracakṣate |17|

17. Die von den Göttern geschaffene Gegend zwischen den Götterflüssen Sarasvatī1 und Dṛṣadvatī2 heißt Brahmāvarta3.

Erläuterungen:

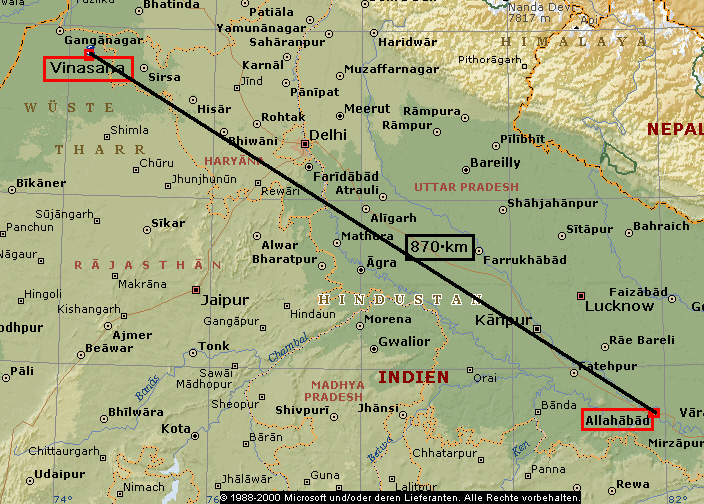

1 Sarasvatī: heiliger Fluss zwischen Yamunā und Sutudrī (Sutlej) im Punjab, der versickert, aber nach der Vorstellung der Inder unterirdisch weiterläuft und bei Prayāga (heute: Allahābād / इलाहाबाद / الہ آباد Ilāhābād) sich mit Gaṅgā und Yamunā vereinigt (Triveni Sangam). Vielleicht etwa der heutige Ghaggar-Hakra

|

"Saraswati (i).—River of the Punjab, rising in Sirmur State close to the borders of Ambala District. It debouches on the plains at Adh Badri, a place held sacred by all Hindus. A few miles farther on it disappears in the sand, but comes up again about three miles to the south at the village of Bhawanipur. At Balchhapar it again vanishes for a short distance, but emerges once more and flows on in a southwesterly direction across Karnal, until it joins the Ghaggar in Patiala territory after a course of about no miles. A District canal takes off from it near Pehowa in Karnal District. The word Saraswati, the feminine of Saraswat, is the Sanskrit form of the Zend Haragaiti (Arachosia) and means 'rich in lakes.' The name was probably given to the river by the Aryan invaders in memory of the Haragaiti of Arachosia, the modern Helmand in Seistan." [Quelle: The Imperial gazetteer of India / published under the authority of His Majesty’s Secretary of State for India in Council. -- New ed. -- Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1907-1909. -- 25 Bde. ; 22 cm. -- Bd. 22. -- 1908. -- S. 97. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/imperialgazettee22greauoft . -- Zugriff am 2008-06-16] |

|

"The Ghaggar-Hakra River is a believed to be an intermittent river in India and Pakistan that flows only during the monsoon season. It is often identified with the Vedic Sarasvati River, but it is disputed whether all Rigvedic references to the Sarasvati should be taken to refer to this river. Many references to this river are mythical and refer to the Indian Epics and Puranas.

Ghaggar River The Ghaggar is an intermittent river in India, flowing during the monsoon rains. It originates in the Shivalik Hills of Himachal Pradesh and flows through Punjab and Haryana to Rajasthan; just southwest of Sirsa in Haryana and by the side of talwara jheel in Rajasthan, this seasonal river feeds two irrigation canals that extend into Rajasthan. The present-day Sarsuti Sarasvati River originates in a submontane region (Ambala district) and joins the Ghaggar near Shatrana in PEPSU. Near Sadulgarh (Hanumangarh) the Naiwal channel, a dried out channel of the Sutlej, joins the Ghaggar. Near Suratgarh the Ghaggar is then joined by the dried up Drishadvati (Chautang) river. The wide river bed (paleo-channel) of the Ghaggar river suggest that the river once flowed full of water, and that it formerly continued through the entire region, in the presently dry channel of the Hakra River, possibly emptying into the Rann of Kutch. It supposedly dried up due to the capture of its tributaries by the Indus and Yamuna rivers, and the loss of rainfall in much of its catchment area due to deforestation and overgrazing.[citation needed] This is supposed by some to have happened at the latest in 1900 BCE, but is much earlier [1] [2] Puri and Verma (1998) have argued that the present-day Tons River was the ancient upper-part of the Sarasvati River, which would then had been fed with Himalayan glaciers. The terrain of this river contains pebbles of quartzite and metamorphic rocks, while the lower terraces in these valleys do not contain such rocks.[3] However, a recent study shows that Bronze Age sediments from the glaciers of the Himalayas are missing along the Gagghar-Hakra, indicating that it did not have its sources in the high mountains.[4] In India there are also various small or middle-sized rivers called Sarasvati or Saraswati. One of them flows from the west end of the Aravalli Range into the east end of the Rann of Kutch. Hakra River The Hakra is the dried-out channel of a river in Pakistan that is the continuation of the Ghaggar River in India. Several times, but not continuously, it carried the water of the Sutlej during the Bronze Age period [5] Many settlements of the Indus Valley Civilisation have been found along the Ghaggar and Hakra rivers. Palaeogeography

Many hymns in all ten Books of the Rig Veda (except the 4th) extol or mention a divine and very large river named the Sarasvati [3], which flows mightily "from the mountains to the samudra, which some take as the Indian Ocean ” Talageri states that "the references to the Sarasvati far outnumber the references to the Indus" and "The Sarasvati is so important in the whole of the Rigveda that it is worshipped as one of the Three Great Goddesses". However these three goddesses (Bharati, etc.) are closely linked with the Bharata tribe that settled in the Sarasvati area after its victory in the "Ten Kings Battle", late in the Rigvedic period. They are missing in the old RV books 4, 6, 8. According to palaeoenvironmental scientists the desiccation of Sarasvati came about as a result of the diversion of at least two rivers that fed it, the Satluj and the Yamuna. "The chain of tectonic events … diverted the Satluj westward (into the Indus) and the Palaeo Yamuna eastward (into the Ganga) … This explains the ‘death’ of such a mighty river (the Sarasvati) … because its main feeders, the Satluj and Palaeo Yamuna were weaned away from it by the Indus and the Gangaa respectively”. This ended at c 1750 b.c., but it started much earlier, perhaps with the upheavals and the large flood of 1900 b.c., or more probably 2100 b.c. [11][12]. P H Francfort, utilizing images from the French satellite SPOT, finds that the large river Sarasvati is pre-Harappan altogether and started drying up in the middle of the 4th millennium BC; during Harappan times only a complex irrigation-canal network was being used in the southern region of the Indus Valley. With this the date should be pushed back to c 3800 BC. R. Mughal (1997), summing up the evidence, concludes that the Bronze Age Gagghar-Hakra sometimes carried more, sometimes less water (for example from the Sutlej). The latter point agrees with a recent isotope study [6] The Rig Vedic hymn X, however, gives a list of names of rivers where Sarasvati is merely mentioned while Sindhu receives all the praise. It is agreed that the tenth Book of the Rig Veda is later than the others. Some think that this may indicate that the Rig Veda could be dated to a period after the first drying up of Sarasvati (c. 3500) when the river lost its preeminence.[6] The assumption is contradicted by the appearance of horses and chariots all over the RV, which was possible only after their introduction after 2000 BCE. The 414 archeological sites along the bed of Sarasvati dwarf the number of sites so far recorded along the entire stretch of the Indus River, which number only about three dozen. However most of the Harappan sites along the Sarasvati are found in desert country, undisturbed since the end of the Indus Civilization. This contrasts with the heavy alluvium of the Indus and other large Panjab rivers that have obscured Harappan sites, including part of Mohenjo Daro. About 80 percent of the Saravati sites are datable to the fourth or third millennium B.C.E., suggesting that the river was flowing during this period. The ancient Ghaggar-Hakra and the Harappan civilization Some estimate that the period at which the river dried up range, very roughly, from 2500 to 2000 BC, with a further margin of error at either end of the date-range. This may be precise in geological terms, but for the mature Indus Valley Civilization (2600 to 1900 BC) it makes all the difference whether the river dried up in 2500 (its early phase) or 2000 (its late phase). Similarly, for the Gandhara grave culture, often identified with the early influx of Indo-Aryans from ca. 1600 BC, it makes a great difference whether the river dried up a millennium earlier, or only a few generations ago, so that by contact with remnants of the IVC like the Cemetery H culture, legendary knowledge of the event may have been acquired. Along the course of the Ghaggar-Hakra river are many archaeological sites of the Indus Valley Civilization; but not further south than the middle of Bahawalpur district. It has been assumed that the Sarasvati ended there in a series of terminal lakes, and some think that its water only reached the Indus or the sea in very wet rainy seasons. However, satellite images contradict this: they do not show subterranean water in reservoirs in the dunes between the Indus and the end of the Hakra west of Fort Derawar/Marot.[7] It may also have been affected by much of its water being taken for irrigation.[citation needed] In a survey conducted by M.R. Mughal between 1974 and 1977, over 400 sites were mapped along 300 miles of the Hakra river.[8] The majority of these sites were dated to the fourth or third millennium BCE.[9] S. P. Gupta however counts over 600 sites of the Indus civilization on the Hakra-Ghaggar river and its tributaries.[10][11] In contrast to this, only 90 to 96 Indus Valley sites have been discovered on the Indus and its tributaries (about 36 sites on the Indus river itself.)[12][13][14] V.N. Misra[15] states that over 530 Harappan sites (of the more than 800 known sites, not including Late Harappan or OCP) are located on the Hakra-Ghaggar.[16] The other sites are mainly in Kutch-Saurashtra (nearly 200 sites), Yamuna Valley (nearly 70 Late Harappan sites) and in the Indus Valley, in Baluchistan, and in the NW Frontier Province (less than 100 sites). Most of the Mature Harappan sites are located in the middle Ghaggar-Hakra river valley, and some on the Indus and in Kutch-Saurashtra. However, just as in other contemporary cultures, such as the BMAC, settlements move up-river due to climate changes around 2000 BCE. In the late Harappan period the number of late Harappan sites in the middle Hakra channel and in the Indus valley diminishes, while it expands in the upper Ghaggar-Sutlej channels and in Saurashtra. The abandonement of many sites on the Hakra-Ghaggar between the Harappan and the Late Harappan phase was probably due to the drying up of the Hakra-Ghaggar river. Painted Grey Ware sites (ca. 1000 BCE) have been found on the bed and not on the banks of the Ghaggar-Hakra river.[17][18] Because most of the Indus Valley sites known so far are actually located on the Hakra-Ghaggar river and its tributaries and not on the Indus river, some archaeologists, such as S.P. Gupta, have proposed to use the term "Indus Sarasvati Civilization" to refer to the Harappan culture which is named, as is common in archaeology, after the first place where the culture was discovered. The Ghaggar-Hakra and its ancient tributaries Satellite photography has shown that the Ghaggar-Hakra was indeed a large river that dried up several times (see Mughal 1997). The dried out Hakra river bed is between three and ten kilometers wide. Recent research indicates that the Sutlej and possibly also the Yamuna once flowed into the Sarasvati river bed. The Sutlej and Yamuna Rivers have changed their courses over the time.[19] Paleobotanical information also documents the aridity that developed after the drying up of the river. (Gadgil and Thapar 1990 and references therein). The disappearance of the river may have been caused by earthquakes which may have led to the redirection of its tributaries.[20] It has also been suggested that the loss of rainfall in much of its catchment area due to deforestation and overgrazing in what is now Pakistan may have also contributed to the drying up of the river. However, a similar phenomenon, caused by climate change, is seen at about the same period north of the Hindu Kush, in the area of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex. The Ghaggar-Hakra and the Sutlej There are no Harappan sites on the Sutlej in its present lower course, only in its upper course near the Siwaliks, and along the dried up channel of the ancient Sutlej,[10] which indicates the Sutlej did flow into the Sarasvati at that period of time. At Ropar the Sutlej river suddenly flows away from the Ghaggar in a sharp turn. The beforehand narrow Ghaggar river bed itself is becoming suddenly wider at the conjunction where the Sutlej should have met the Ghaggar river. And there is a major paleochannel between the point where the Sutlej takes a sharp turn and where the Ghaggar river bed widens.[21][22] In later texts like the Mahabharata, the Rigvedic Sutudri (of unknown, non-Sanskrit etymology [23] is called Shatudri (Shatadru/Shatadhara), which means a river with 100 flows.[24] The Sutlej (and the Beas and Ravi) have frequently changed their courses.[24] The Beas has also probably sometimes flown into the Sutlej further downstream from where it joins that river today. Before that Sutlej is said to have flown into Ghaggar[25][24] The Ghaggar-Hakra and the Yamuna There are also no Harappan sites on the present Yamuna river. There are however Painted Gray Ware (1000 - 600 BC) sites on the Yamuna channel, showing that the river must have flowed in the present channel during this period.[26] The distribution of the Painted Gray Ware sites in the Ghaggar river valley indicates that during this period the Ghaggar river was already partly dried up. Scholars like Raikes (1968) and Suraj Bhan (1972, 1973, 1975, 1977) have shown that based on archaeological, geomorphic and sedimentological research the Yamuna may have flowed into the Sarasvati during Harappan times.[27] There are several dried out river beds (paleochannels) between the Sutlej and the Yamuna, some of them two to ten kilometres wide. They are not always visible on the ground because of excessive silting and encroachment by sand of the dried out river channels. [28] The Yamuna may have flowed into the Sarasvati river through the Chautang or the Drishadvati channel, since many Harappan sites have been discovered on these dried out river beds.[29] Identification with the Rigvedic Sarasvati

The identification with the Sarasvati River is based the mentionings in Vedic texts (e.g. in the enumeration of the rivers in Rigveda 10.75.05, the order is Ganga, Yamuna, Sarasvati, Sutudri Sutlej), Parusni, etc., and other geological and paleobotanical findings. This however, is disputed. The Victorian era scholar C.F. Oldham (1886) was the first to suggest that geological events had redirected the river, and to connect it to the lost Saraswati: "[it] was formerly the Sarasvati; that name is still known amongst the people, and the famous fortress of Sarsuti or Sarasvati was built upon its banks, nearly 100 miles below the present junction with the Ghaggar."[30][31] References

Bibliography

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghaggar-Hakra_river. -- Zugriff am 2008-09-14] |

||

|

"Triveni Sangam is the confluence of three rivers (Ganga, Yamuna and the legendary Saraswati River) near Allahābād, India. Background Sangama is the Sanskrit word for confluence. The Triveni Sangam in Allahābād is a confluence of three rivers, the Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati. Of these three, the river Saraswati is invisible and is said to flow underground and join the other two rivers from below. The point of confluence is a sacred place for Hindus. A bath here is said to wash away all one's sins and free one from the cycle of rebirth. The sight of the Sangam is a treat to the eyes. One can see the muddy and pale-yellow waters of Ganga merging with the blue waters of Yamuna. The Ganga is only 4 feet deep, while Yamuna is 40 feet deep near the point of their nexus. The river Yamuna merges into the Ganges at this point and the Ganges continues on until it meets the sea at the Bay of Bengal. At the confluence of these two great Indian rivers, where the invisible Saraswati conjoins them, many tirtha yatris take boats to bathe from platforms erected in the Sangam. This, together with the migratory birds give a picturesque look to the river during the kumbh, in the month of January. It is believed that all the gods come in human form to take a dip at the sangam and expiate their sins. The pollution of this great river is a grave cause of concern for all religious-minded people. Although on paper the Government has spent crores of rupees to cleanse the Ganga, corruption has left the river in no better state, despite the river being venerated by all those high-placed industrialists, judges and politicians. Above all, the common man has never given thought to keeping it clean. This was the river where an earlier Prime minister of India, Indira Gandhi used to come for a holy dip. The people should take urgent steps to stop the pollution of this great, holy river, where the "nectar pot" was kept, as stated in the Puranas. On the bank of Ganga at Daraganj, just before the confluence of ganga and Yamuna,the well known statistician Ravindra Khattree, spent his early years when he attended Ewing Christian College, situated on the bank of Yamuna few miles before the confluence. On the other bank of the river Ganga at Arail is located the Maharshi Institute of Management, named for Maharshi Mahesh Yogiwho was a student at the University of Allahābād. The Harish Chandra Research Institute, named after the famous mathematician Harish Chandra, from Allahābād is also located on the same side in the village of Jhusi. Religious significance The Triveni Sangam is believed to be the same place where drops of Nectar fell from the pitcher, from the hands of the Gods. So it is believed that a bath in the Sangam will wash away all one's sins and will clear the way to heaven. Devout Hindus from all over India come to this sacred pilgrimage point to offer prayers and take a dip in the holy waters. The sacred Kumbh Mela is held every 12 years on the banks of the Sangam. According to myth, the Prakrista Yajna was performed here by Lord Brahma. That is how Allahābād received its ancient name, Prayāg. Allahābād is also called Tirtha-Raja (Prayāg Raj), king of all holy places. It is said that Lord Rama visited Allahābād when he was in exile." [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sangam_at_Allahābād. -- Zugriff am 2008-09-14] |

2 Dṛṣadvatī: ("die Felsige")

|

"The Drsadvati River (dṛṣad-vatī, meaning "she with many stones") is a river already mentioned in the Rig Veda (RV 3.23.4) together with Sarasvati and Apaya. In later texts, Vedic sacrifices are performed on this river and on the Sarasvati River (Pancavimsa Brahmana; Katyayana Sratua Sutra; Latyayana Srauta Sutra). In the Manu Smriti, this river and the Sarasvati River define the boundary of Brahmavarta.

The Drsadvati River has often been identified with the Chautang River.[1] Talageri (2000) identifies it with the Hariyupiya and the Yavyavati. References

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drishadvati. -- Zugriff am 2008-09-14] |

|

"Chautang.—River in the Ambala and Karnal Districts of the Punjab, rising in the plains a few miles south of the Saraswati, to which it runs parallel for a distance. Near Balchhapar the two rivers apparently unite in the sands, but reappear in two distinct channels farther down, the Chautang running parallel to the Jumnā, and then turning westward towards Hansi and Hissar. The bed in this part of its course affords a channel for the Hissar branch of the Western Jumnā Canal. Traces of the deserted waterway are visible as far as the Ghaggar, which it formerly joined some miles below Bhatnair, after a course of about 260 miles : but the stream is now entirely diverted into the canal. In former days it lost itself in the sand, like others of the smaller cis-Sutlej rivers. Some authorities consider that the Chautang was originally an artificial channel. Cultivation extends along its banks in a few isolated patches, but for the most part a fringe of dense jungle lines its course." [Quelle: The Imperial gazetteer of India / published under the authority of His Majesty’s Secretary of State for India in Council. -- New ed. -- Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1907-1909. -- 25 Bde. ; 22 cm. -- Bd. 10. -- 1908. -- S. 186. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/imperialgazettee10greauoft . -- Zugriff am 2008-06-16] |

3 Brahmāvarta: Brahma-āvarta: "Wo sich Brahman, der Veda, zuwendet" und "Tummelplatz des Veda"

tasmin

deśe ya ācāraḥ

pāramparyakramāgataḥ

|

varṇānāṃ sāntarālānāṃ

sa sadācāra ucyate | 18 |

18. Das Verhalten, das in dieser Gegend durch ununterbrochene Überlieferung für die Stände samt Zwischenständen überkommen ist, nennt man Verhalten der Guten.

kurukṣetraṃ

ca matsyāś

ca pañcālāḥ

śūrasenakāḥ |

eṣa brahmarṣideśo

vai

brahmāvartād anantaraḥ |19|

19. Unmittelbar anschließend an Brahmāvarta liegt Brahmarṣideśa1, bestehend aus Kurukṣetra2 und den Ländern der Matsya3, der Pañcāla4 und der Śūrasenaka5.

Erläuterungen:

1 Brahmarṣideśa: "Land der Brahma-Ṛṣis" = "Veda-Ṛṣis" bzw. Brahmanische Ṛṣis (die Liste ist unterschiedlich) = die höchste Gruppe der Ṛṣis.

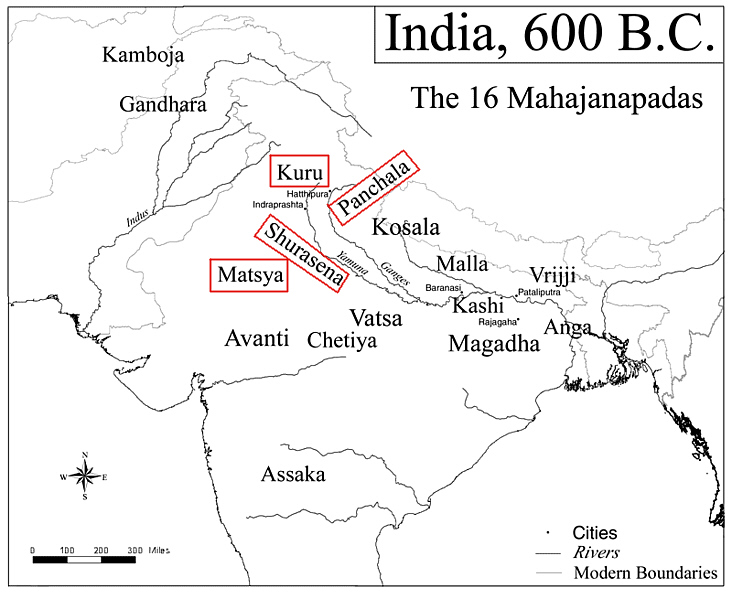

Abb.:

Ungefähre Lage von Kurukṣetra, Matsya, Pañcāla

und Śūrasena

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

2 Kurukṣetra: heute mit dem Distrikt "Kurukshetra" in Haryana identifiziert. Medhātithi zitiert folgende Volksetymologie von Kuru-kṣetra: kuru sukṛtam atra kṣipraṃ trāṇaṃ bhavati "Tue (kuru) Gutes hier und schnell kommt Erlösung."

|

"Kurukshetra.—A sacred tract of the Hindus, lying between 29° 15' and 30° N. and 76° 20' and 77° E., in the Karnāl District and the Jīnd State of the Punjab. According to the Mahābhārata, which contains the oldest account of the tract, it lay between the Saraswatī and Drishadwatī (now the Rakshī), being watered by seven or nine streams, including these two. It was also divided into seven or nine bans or forests. The circuit of Kurukshetra probably did not exceed 160 miles ; and it formed an irregular quadrilateral, its northern side extending from Ber at the junction of the Saraswatī and Ghaggar to Thānesar, and its southern from Sinkh, south of Safīdon, to Rām Rai, south-west of Jīnd. The name, 'the field of Kuru,' is derived from Kuru, the ancestor of the Kauravas and Pāndavas, between whom was fought the great conflict described in the Mahābhārata ; but the tract was also called the Dharmakshetra or 'holy land,' and would appear to have been famous long before the time of the Kauravas, for at Thānesar Parasu Rāma is said to have slain the Kshattriyas, and the lake of Sarvanavat on the skirts of Kurukshetra is alluded to in the Rig-veda in connexion with the legend of the horse-headed Dadhyanch. Nardak is another name for Kurukshetra, probably derived from nirdukh, 'without sorrow.' The Chinese pilgrim, Hiuen Tsiang, who visited it in the seventh century, calls it 'the field of happiness.' Kurukshetra contains, it is said, 360 places connected with these legends or with the cults of Siva and the Sun-god, which have long been places of pilgrimage. Of these the principal are Thānesar, Pehowa, Jīnd, Safīdon, and Kaithal ; but numerous other sites preserve their ancient names and sanctity." [Quelle: The Imperial gazetteer of India / published under the authority of His Majesty’s Secretary of State for India in Council. -- New ed. -- Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1907-1909. -- 25 Bde. ; 22 cm. -- Bd. 16. -- 1908. -- S. 54f. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/imperialgazettee16greauoft . -- Zugriff am 2008-06-16] |

|

"Kurukshetra (Sanskrit, m., कुरुक्षेत्र, kurukṣetra, "das Feld der Kurus") ist eine Stadt im indischen Bundesstaat Haryana. Sie zählt 154 000 Einwohner (Stand 2005) und ist Verwaltungssitz des Distrikts Kurukshetra. Kurukshetra liegt etwa 160 Kilometer nördlich von Delhi, 39 Kilometer nördlich von Karnal und 40 Kilometer südlich von Ambala. 6 Kilometer von der Stadt entfernt bei Pipli liegt der National Highway 1, bekannt als Grand Trunk Road. Die Stadt hat eine Universität (Kurukshetra University). Mythologie Auf dem "Feld Kurus" fand der Überlieferung des Mahabharata zufolge eine große Schlacht statt, die den Hintergrund für die Bhagavadgita bildete. In dieser 18 Tage dauernden Schlacht kämpften die Kauravas, Nachkommen der Kuru Dynastie gegen die Pandavas, die ebenfalls zu den Kurus gehörten. Die Pandavas waren zuvor von den Kauravas um ihr Königreich betrogen worden und verlangten nach einer 13-jährigen Verbannung ihren Anteil zurück. In der daraus resultierenden Schlacht kämpften die nahen Blutsverwandten aus drei Generationen gegeneinander sowie als Verbündete die größten Krieger ihrer Zeit. In dieser schwierigen Situation - vor Beginn des Kampfes - erläutert der göttliche Krishna als Wagenlenker von Arjuna, dem großen Helden der Pandavas, warum er kämpfen muss. Diese philosophischen Erläuterungen fassen das Wissen der verschiedenen geistigen und religiösen Strömungen der Vergangenheit zusammen. Dieser "Gesang des Erhabenen", die Bhagavadgita, zählt auch heute noch zu den meistgelesenen heiligen Büchern Indiens. Es wird immer wieder behauptet, die Schlacht habe vor ca. 3000 v.Chr. stattgefunden. Die im Mahabharata erwähnten Sternenkonstellationen lassen eine derartige Deutung zwar zu, allerdings sprechen die beschriebenen Waffen und Streitwagen für eine deutlich spätere Zeit (1. Jahrtausend v.Chr.). Trotz aller Unsicherheiten sehen viele Hindus diese Schlacht als historische Begebenheit, aber auch als Allegorie. So wie etwa Aurobindo in seinem Essays on the Gita, interpretieren sie die kriegerischen Auseinandersetzungen in Kurukshetra auch als Sinnbild für das 'Schlachtfeld' des Yogas und die Auseinandersetzung zwischen den Kräften der göttlichen Ordnung und denen des Egos. Sehenswürdigkeiten In einem Sri-Krishna-Museum sind Arbeiten von Hunderten von Künstlern aus ganz Indien ausgestellt, die Krishna in Holz, Stein, Bronze, Elfenbein und auf andern Materialien modern oder traditionell porträtiert haben. In einem Kurukshetra Panorama & Science Center wird die Schlacht aus dem Mahabharata in Modellen nachgebildet. In der Nähe von Kurukshetra in Jyotisar befindet sich ein Tempel mit einem Banyanbaum, welcher der Spross des Baumes sein soll unter dem Krishna Arjuna die Bhagavadgita offenbarte." [Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurukshetra. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-14] |

3 Matsya:

|

"Matsya or Machcha (Sanskrit for fish) was the name of a tribe and the state of the Vedic civilization of India. It lay to south of the kingdom of Kurus and west of the Yamuna which separated it from the kingdom of Panchalas. It roughly corresponded to former state of Jaipur in Rajasthan, and included the whole of Alwar with portions of Bharatpur. The capital of Matsya was at Viratanagara (modern Bairat) which is said to have been named after its founder king Virata. In Pāli literature, the Matsya tribe is usually associated with the Surasena. The western Matsya was the hill tract on the north bank of Chambal. A branch of Matsya is also found in later days in Visakhapatnam region. In early 6th century BCE, Matsya was one the solasa (sixteen) Mahajanapadas (great kingdoms) mentioned in the Buddhist text Anguttara Nikaya, but its political clout had greatly dwindled and had not much of political importance left by the time of Buddha. The Mahabharata (V.74.16) refers to a King Sahaja, who ruled over both the Chedis and the Matsyas which implicates that Matsya once formed a part of the Chedi Kingdom. Meenas are considered the brothers and kinsmen of Virata, the ruler of Virat Nagar. They ruled this area (near to Virat Nagar) till 11th century CE." [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matsya_Rajya. -- Zugriff am 2008-09-14] |

4 Pañcāla:

|

"Panchāla.—An ancient kingdom of Northern India, forming the centre of the Madhya-Desa or 'middle country.' There were two divisions : Northern Panchāla, with its capital at Ahīchhattra or Adikshetra, in Bareilly ; and Southern Panchāla, with its capital at Kampil, in Farrukhābād. They were divided by the Ganges, and together reached from the Himālayas to the Chambal. In the Mahābhārata we find the Pāndava brothers, after leaving Hastināpur (in Meerut District) and wandering in the jungles, coming to the tournament at the court of Drupada, king of Panchāla, the prize for which was the hand of his daughter, Draupadī. The scene of the contest is still pointed out west of Kampil, and a common flower in the village lanes bears the name of draupadī. In the second century B.C. Northern Panchāla appears to have been a kingdom of some importance, for coins of about a dozen kings inscribed in characters of that period are found in various parts of it, but not elsewhere. It has been conjectured that these were the Sunga kings who, according to the Purānas, reigned after the Mauryas ; but only a single name, Agni Mitra, is found both in the Purānic lists and on the coins, though many others are compounds with Mitra ('friend'). The coins point to an absence of Buddhistic tendencies. Varāha Mihira, the Sanskrit geographer of the sixth century A. D., mentions a people, the Panchālas, who evidently inhabited the region described above. [Lassen, Ind. Alt., vol. i, p. 598 ; Cunningham, Coins of Ancient India, p. 79; Fleet, Ind. Ant., 1893, p. 170]" [Quelle: The Imperial gazetteer of India / published under the authority of His Majesty’s Secretary of State for India in Council. -- New ed. -- Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1907-1909. -- 25 Bde. ; 22 cm. -- Bd. 19. -- 1908. -- S. 377f. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/imperialgazettee19greauoft . -- Zugriff am 2008-06-16] |

|

"Panchala (Sanskrit: पांचाल) corresponds to the geographical area around the Ganges River and Yamuna River, the upper Gangetic plain in particular. This would encompass the modern-day states of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. During ancient times, it was home to an Indian kingdom, the Panchalas, one of the Mahajanapadas. The Panchalas occupied the country to the east of the Kurus, between the upper Himalayas and the river Ganga. It roughly corresponded to modern Budaun, Farrukhabad and the adjoining districts of Uttar Pradesh. The country was divided into Uttara-Panchala and Dakshina-Panchala. The northern Panchala had its capital at Adhichhatra or Chhatravati (modern Ramnagar, Uttarakhand in the Nainital District), while southern Panchala had it capital at Kampilya or Kampil in Farrukhabad District. The famous city of Kanyakubja or Kannauj was situated in the kingdom of Panchala. Panchala was the second "urban" center of Vedic civilization, as its focus moved east from the Punjab, after the focus of power had been with the Kurus in the early Iron Age. This period is associated with the Painted Grey Ware culture, arising beginning around 1100 BC, and declining from 600 BC, with the end of the Vedic period. The Shaunaka and Taittiriya Vedic schools were located in the area of Panchala. Originally a monarchical clan, the Panchals appear to have switched to republican corporation around 500 BC. The 4th century BC Arthashastra also attests the Panchalas as following the Rajashabdopajivin (king consul) constitution. In the Indian Hindu epic Mahabharata, Draupadi (wife of the five Pandava brothers) was the princess of Panchala; Panchali was her other name." [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Panchala. -- Zugriff am 2008-09-14] |

5 Śūrasenaka: Bevölkerung von Śūrasena rund um Mathurā

|