Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 3. Inschriften. -- 1. Zum Beispiel: Aśoka-Inschriften. -- Fassung vom 2008-04-05. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen031.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2008-03-03

Überarbeitungen: 2008-04-05 [Ergänzung]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Da zur Zeit nicht die Muße habe, meine eigene Übersetzung der Aśoka-Inschriften für eine Internet-Veröffentlichung zu überarbeiten, gebe ich im Folgenden die Übersetzung von Eugen Hultzsch (1857 - 1927) wieder aus seiner vorbildlichen Ausgabe der bis dahin (1925) aufgefundenen Aśoka-Inschriften:

Inscriptions of Aśoka / new ed. By E. Hultzsch. With 55 plates. -- 1925. -- cxxxi, 260 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm. -- Supersedes: Inscriptions of Aśoka / Prepared by Alexander Cunningham. -- Calcutta, 1887. -- (Corpus inscriptionum indicarum ; vol. I)

Obwohl die Übersetzung von Hultzsch in Einzelheiten überholt und korrigiert ist, ist sie im Ganzen immer noch eine Meisterleistung. Für die Fußnoten, Faksimiles und Transliteration der Texte konsultiere man das Originalwerk von Hultzsch.

|

|

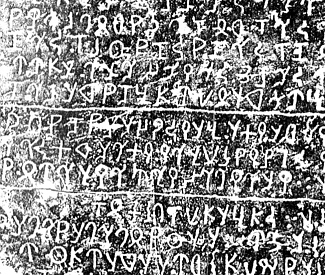

Eugen Hultzsch (1857 - 1927) |

|

"Hultzsch, Eugen, Indologe, geb. 29.3.1857

Dresden, gest. 16.1.1927 Halle/Saale Hultzsch studierte in Bonn und Leipzig Indologie, klassische Philologie, Persisch und Arabisch, wurde 1879 promoviert und setzte die indologischen Studien in London und Wien fort, wo er sich 1882 für orientalische Sprachen habilitierte. Er beschäftigte sich vor allem mit der indischen Epigraphik, ferner mit indischen Sanskrit-Manuskripten und brachte von der 1884 nach Kaschmir unternommenen Reise seltene Manuskripte mit. Hultzsch wirkte seit 1886 als Epigraphist to the Governement of Madras, Examiner of Sanskrit und Fellow of the University of Madras und wurde 1903 o. Prof. in Halle/Saale. Er beherrschte das klassische Sanskrit und Prakrit, veröffentlichte u.a. Inscriptions of Aśoka (1925) und war Herausgeber der South-Indian Inscriptions (Bd. 1-3, 1890-1903)." [Quelle: Deutsche biographische Enzyklopädie & Deutscher biographischer Index. -- CD-ROM-Ed. -- München : Saur, 2001. -- 1 CD-ROM. -- ISBN 3-598-40360-7. -- s.v.] |

Im Ganzen sind immer noch die Ausführungen von Eugen Hultzsch gültig:

"CHAPTER II. THE AUTHOR OF THE INSCRIPTIONS The king at whose orders the rock- and pillar-edicts published in the first and second parts of this volume were engraved, gives his name or title in various Prākṛt forms of which the Sanskrit would be Devānāṃpriyaḥ Priyadarśī rājā? This full

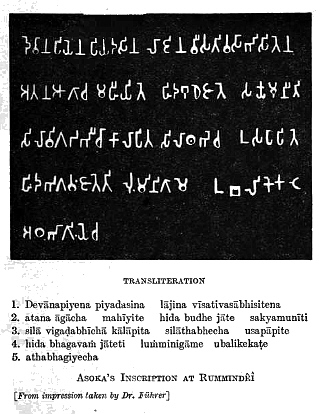

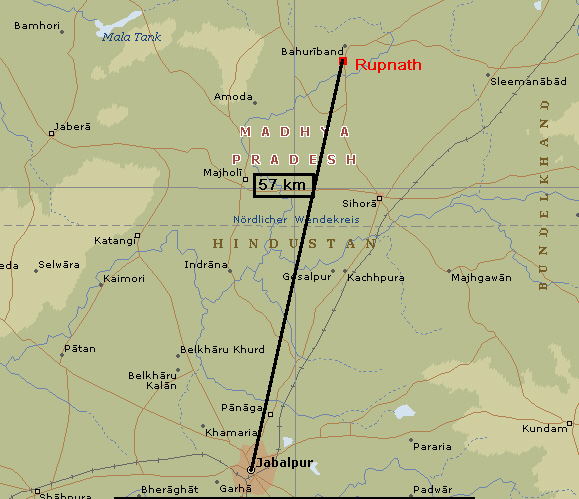

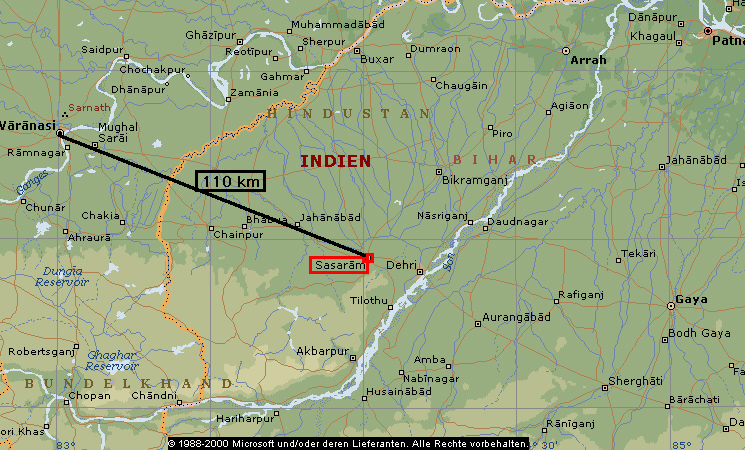

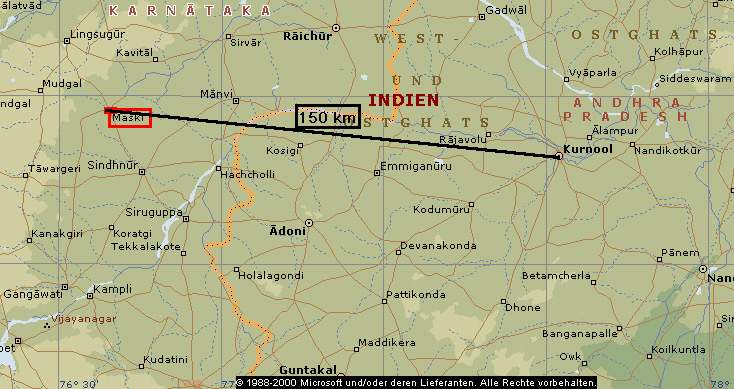

form of his title is shortened into Devānāṃpriyaḥ in section C of the Dhauli and Jaugaḍa rock-edict X, in all texts of the rock-edicts XII and XIII after the opening section, in which the full style is preserved, and in the Delhi-Toprā pillar-edict VII, RR. In the two separate rock-edicts at Dhauli and Jaugaḍa, in the Queen's pillar-edict, and in the Kauśāmbī pillar-edict, Devānāṃpriyaḥ alone is found.Among the records published in the third and fourth parts of this volume, the Rummindeī and Nigālī Sāgar pillars exhibit the full form Devānāṃpriyaḥ Priyadarśī raja. The Maski rock-inscription opens with the genitive case of Devānāṃpriya Aśoka. On the Sārnāth pillar and in the Rūpnāth, Sahasrām, Bairāṭ, and the three Mysore rock-inscriptions we have only Devānāṃpriyaḥ. On the Sāṃchī pillar this word is lost; but the contents of the Sāṃchī and Sārnāth pillars are so nearly related to those of the Kauśāmbī edict on the Allahabad-Kosam pillar, that they can be safely referred to the same royal author. The same applies to the rock-inscriptions at Rūpnāth, &c, which remind us of the rock- and pillar-edicts in many significant details.

There remain the Calcutta-Bairāṭ rock-inscription and the three Barābar Hill cave-inscriptions. In the former the king styles himself Priyadarśī rājā, and in the three others rājā Priyadarśī. In the Calcutta-Bairāṭ record the king shows a strong interest in Buddhism. It would be, therefore, hypercritical not to assign this document to the same sovereign who paid visits to Sambodhi, (rock-edict VIII, C), to Luṃmini (Rummindeī pillar), and to the Stūpa of Konākamana (Nigālī Sāgar pillar). We cannot, however, decide with certainty whether the three Barābar Hill inscriptions belong to the same king or to another member of his dynasty. In favour of the former alternative it may perhaps be urged that two of the caves on the Barābar Hill were dedicated to the Ājīvikas when the donor had been 'anointed twelve years'. For, this happens to be the regnal year in which the author of the rock- and pillar-edict commenced to issue 'rescripts on morality'; see the pillar-edict VI, B, and cf. the rock-edict IV, K.

The etymological meaning of the term Devānāṃpriya is 'dear to the gods'. According to Patañjali's Mahābhāshya on Pāṇini, II, 4, 56, and V, 3, 14, this word was used as an honorific like bhavan, dirghayuh, and ayushman. Pāṇini himself does not mention Devānāṃpriya, but states that the termination of the genitive case is preserved at the end of the first member of compounds if the meaning is abusive ṣaṣṭhyā ākrośe, VI, 3, 21). The Kāśikā commentary adduces the two examples caurasyakulaṃ ' the family of a thief, and vṛṣalasyakulaṃ, 'the family of a low-caste man'. Kātyāyana affixes to Pāṇini's Sutra five Vārttikas, the third of which states that the compound Devānāṃpriya ought to be added. Neither the Mahābhāshya nor the Kāśikā have the word murkhe, 'with the meaning of "fool", which the Siddhāntakaumudī adds to the Vārttika. This secondary meaning of Devānāṃpriya was already known to Patañjali's commentator Kaiyaṭa, while Kātyāyana and Patañjali ignore it, although Patañjali on Pāṇini, II, 4, 56, seems to have used Devānāṃpriya in an ironical sense. In Baṇa's Harshacharita it is found twice as an honorific. In the same way Devāṇuppiya is employed frequently in Jaina literature.In the Dīpavaṃsa, Devanampiya is prefixed to the name of Aśoka's contemporary, Tissa of Ceylon, and is often used alone to denote him, and in the Nāgārjunī Hill cave-inscriptions it follows the name of Aśoka's grandson Daśaratha. In a few of the inscriptions published in this volume it is employed as a synonym of rājan, ' a king': In the Kālsī, Shāhbāzgaṛhī, and Mānsehrā texts of the rock-edict VIII, A, the king's predecessors are called Devānaṃpiya and Devānāṃpriya, while the Gīrnār and Dhauli versions have rājāno and lājāne; and the word Devānaṃpiye in the second separate edict at Dhauli (twice in section G and thrice in I) corresponds to lājā in the Jaugaḍa text of the same edict (sections H and J).

As stated above (p. xxviii), another epithet of the king to whom the inscriptions published in this volume are due was Priyadarśin, 'he who glances amiably'. Both Piyadassi and Piyadassana, ' of amiable appearance', occur repeatedly in the Dīpavaṃsa as equivalents of Aśoka, the name of the great Maurya king. In the drama Mudrārākskasa, Piadaṃsaṇa is prefixed to Chandasiri, i.e. Chandragupta, the name of Aśoka's grandfather.

Before discussing Prinsep's identification of the king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin of the inscriptions with the Maurya king Aśoka, it will be advisable to quote from the texts a few details which are of leading importance in this connexion. The opening section of the Calcutta-Bairāṭ rock-inscription informs us that Priyadarśin was a Māgadha king, i. e. a ruler of Māgadha. From the rock-edict V, M, we learn that his capital was Pāṭaliputra; for, the words 'both in Pāṭaliputra and in the outlying [towns]' at Gīrnār correspond to 'here and in all the outlying towns' at Kālsī, Shāhbāzgaṛhī, Mānsehrā, and Dhauli. In the second and thirteenth rock-edicts the king refers to a number of contemporary Yona, i.e. Greek, kings : the rock-edict II, A, mentions 'the Yona king Antiyoka (Antiyaka at Gīrnār, Antiyoga at Kālsī and Mānsehrā) and the kings who are the neighbours of this Antiyoka'; and the rock-edict XIII, Q, 'the Yona king Antiyoka (Antiyoga at Kālsī and Mānsehrā), and beyond him four kings, viz. Turamāya (Tulamaya at Kālsī), Antekina (Antikini at Shāhbāzgaṛhī), Makā (Magā at Gīrnār), and Alikasudara (Alikyashudala at Kālsī)'.

The great decipherer of the old Brāhmī alphabet, James Prinsep, at first ascribed the edicts to Devānaṃpiya Tissa of Ceylon. This is of course impossible because we know now that the author of the edicts calls himself a king of Māgadha, and that he resided at Pāṭaliputra. The discovery of the Nāgārjunī Hill cave-inscriptions of Dashalatha Devānaṃpiya, whom Prinsep at once identified with Daśaratha, the grandson of the Maurya king Aśoka (id., p. 676 ft), and the fact that Turnour had found Piyadassi or Piyadassana used as a surname of Aśoka in the Dīpavaṃsa, induced Prinsep to abandon his original view, and to identify king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin with Aśoka himself (id., p. 790 ff.). A limine another member of the Maurya dynasty

might be meant as well; for, as stated above (p. xxx), the eighth rock-edict shows that the king's predecessors also bore the title Devānāṃpriya, and the Mudrārākshasa applies the epithet Priyadarśana to Chandragupta. Every such doubt is now set at rest by the discovery of the Maski edict, in which the king calls himself Devānāṃpriya Aśoka.In February, 1838, Prinsep published the text and a translation of the second rock-edict He found in the Gīrnār version of it (l. 3) the words Aṃtiyako Yona-rājā, and in the Dhauli version (l. 1) Aṃtiyoke nāma Yona-lājā, and identified the Yona king Antiyaka or Antiyoka with Antiochus III of Syria. In March, 1838, he discovered in the Gīrnār edict XIII (l. 8) the names of Turamāya, Aṃtikona, and Magā, whom he most ingeniously identified with Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt, Antigonus Gonatas of Macedonia (?), and Magas of Cyrene. At the same time he modified his earlier theory, and now referred the name Antiyoka to Antiochus I or II of Syria, preferably the former (id., p. 224 ff.).

On the Gīrnār rock the name of a fifth king, who was mentioned after Magā, is lost. The Shāhbāzgaṛhī version calls him Alikasudara. Norris recognised that this name corresponds to the Greek Αλεξανδρος, and suggested hesitatingly that Alexander of Epirus, the son of Pyrrhus, might be meant by it. This identification was endorsed by Westergaard, Lassen, and Senart. But Professor Beloch now thinks that Alexander of Corinth, the son of Craterus, has a better claim.

As will appear in the sequel, the mention of these five contemporaries in the inscriptions of king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin confirms in a general way the correctness of Prinsep's identification of the latter with Aśoka, the grandson of Chandragupta whose approximate time we know from Greek and Roman records. Antiochus I Soter of Syria reigned 280-261 B.C., his son Antiochus II Theos 261-246, Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt 285-247, Antigonus Gonatas of Macedonia 276-239, Magas of Cyrene c. 300-c. 250, Alexander of Epirus 272-c. 255, and Alexander of Corinth 252-c. 244. The rock-edict XIII cannot be placed earlier than twelve years after Aśoka's abhisheka, when he commenced publishing 'rescripts on morality'. If we assume that the rock-edicts are arranged in chronological order, it cannot have been issued earlier than thirteen years after the abhisheka, when Aśoka appointed 'Mahāmātras of morality' as he tells us in edict V. If the Alikasudara of edict XIII is Alexander of Epirus, its date would fall between 272 and 255, and if Alexander of Corinth is meant, between 252 and 250. For fixing the period of Aśoka's reign within narrower limits, we are thrown back on what information can be gathered from Indian and classical literature concerning Aśoka's grandfather Chandragupta.

The historical tradition of India, Ceylon, and Burma is unanimous in naming as the founder of the Maurya dynasty Chandragupta, and as his two immediate successors Bindusāra and Aśoka. The pseudo-prophetic account of the Purāṇas runs thus :

'Kauṭilya (or Chāṇakya) will establish king Chandragupta in the kingdom. Chandragupta will be king twenty-four years, Bindusāra twenty-five years, and Aśoka thirty-six years.'

According to the Dīpavaṃsa, Chandragupta reigned twenty-four years (V, 73, 100), and Bindusāra's son Aśoka thirty-seven years (V, 101).

The Mahāvamsa states that the Brāhmaṇa Chanakya anointed the Maurya Chandragupta (V, 16 f.), and that Chandragupta reigned twenty-four years, his son Bindusāra twenty-eight years (V, 18), and Bindusāra's son Aśoka (V, 19) thirty-seven years (XX, 6).

Buddhaghosha's Samāntapāsādikā agrees with the Mahāvaṃsa in allotting twenty-four years to Chandragupta and twenty-eight'years to Bindusāra.

The Burmese tradition assigns twenty-four years to Chandragupta and twenty-seven years to Bindusāra.

It will be seen that all sources agree in fixing the length of Chandragupta's reign at twenty-four years. To Bindusāra the Ceylonese chronicles allot twenty-eight years, Bigandet twenty-seven years, and the Purāṇas twenty-five years.

The Ceylonese sources state that Aśoka succeeded his father Bindusāra 214 years after Buddha's Nirvāṇa, and that his anointment took place four years after his father's death, or 218 years after the Nirvāṇa. The Burmese tradition confirms the two dates 214 and 218.

As, according to the Ceylonese sources, Bindusāra ruled twenty-eight years and Chandragupta twenty-four years, the former would have reigned A.B. 186—214, and the latter A.B. 162-186. If we deduct the year of Chandragupta's accession to the throne (162) from the traditional date of the Nirvāṇa, 544 B.C., the result is 382 B.C. This Would be about sixty years earlier than the actual accession of Chandragupta as ascertained from Greek sources. For, luckily, the approximate time of king Chandragupta of Pāṭaliputra has been already settled by one of the great pioneers of Indian research, Sir William Jones, who identified him with Σανδρακοττος of Παλιβοθρα, the contemporary of Seleucus Nikator.

Various devices were proposed in order to account for this chronological error, until Fleet showed that the Buddha-varsha of 544 B.C. is a comparatively modern fabrication, of the twelfth century, and that the difference of about sixty years is the quite natural result of accumulated mistakes which were made in rounding off the figures of the regnal years of the kings of Ceylon.

While thus the alleged date of the Nirvāṇa in 544 B.C. and that of Chandragupta's accession in 382 B.C. have no practical value, the traditional interval of 218 years between the Nirvāṇa and Aśoka's abhisheka might still be considered authentic. There are, however, two facts which in my opinion render it somewhat suspicious. It includes a period of 100 years between the Nirvāṇa and the Second Council. Such, a nice round sum as just 100 years looks very much like a clumsy guess and a pure invention. Secondly, the traditional figures of the Northern Buddhists are almost totally at variance with those of the Southern Buddhists.The leading passage concerning Chandragupta's date is found in Justin's Epitoma Pompei Trogi, XV, 4:

'[Seleucus] multa in Oriente post divisionem inter socios regni Macedonici bella gessit. Principio Babyloniam cepit; inde auctis ex victoria viribus Bactrianos expug-navit. Transitum deinde in Indiam fecit, quae post mortem Alexandri, veluti a cervicibus iugo servitutis excusso, praefectos eius occiderat. Auctor libertatis Sandrocottus fuerat, sed titulum libertatis post victoriam in servitutem verterat; siquidem occupato regno populum, que ab externa dominatione vindicaverat, ipse servitio premebat. Fuit hic humili quidem genere natus, sed ad regni potestatem maiestate numinis inpulsus. Quippe cum procacitate sua Nandrum regem offendisset, interfici a rege iussus salutem pedum celeritate quaesierat. Ex qua fatigatione cum somno captus iaceret, leo ingentis formae ad dormientem accessit sudoremque profluentem lingua ei detersit expergefactumque blande reliquit. Hoc prodigio primum ad spem regni inpulsus contractis latronibus Indos ad novitatem regni sollicitavit. Molienti deinde bellum adversus praefectos Alexandri elephantus ferus infinitae magnitudinis ultro se obtulit et veluti domita mansuetudine eum tergo excepit duxque belli et proeliator insignis fuit. Sic adquisito regno Sandrocottus ea tempestate, qua Seleucus futurae magnitudinis fundamenta iaciebat, Indiam possidebat, cum quo facta pactione Seleucus conpositisque in Oriente rebus in bellum Antigoni descendit.'

McCrindle translates this as follows:

'[Seleucus] waged many wars in the East after the partition of Alexander's empire among his generals. He first took Babylonia, and then with his forces augmented by victory subjugated the Bactrians. He then passed over into India, which after Alexander's death, as if the yoke of servitude had been shaken off from its neck, had put his prefects to death. Sandrocottus had been the leader who achieved their freedom, but after his victory he had forfeited by his tyranny all title to the name of liberator; for, having ascended the throne, he oppressed with servitude the very people whom he had emancipated from foreign thraldom. He was born in humble life, but was prompted to aspire to royalty by an omen significant of an august destiny. For when by his insolent behaviour he had offended king Nandrus, and was ordered by that king to be put to death, he had sought safety by a speedy flight. When he lay down overcome with fatigue and had fallen into a deep sleep, a lion of enormous size approaching the slumberer licked with its tongue the sweat which oozed profusely from his body, and when he awoke quietly took its departure. It was this prodigy which first inspired him with the hope of winning the throne, and so, having collected a band of robbers, he instigated the Indians to overthrow the existing government. When he was thereafter preparing to attack Alexanders prefects, a wild elephant of monstrous size approached him, and kneeling submissively like a tame elephant received him on to its back and fought vigorously in front of the army. Sandrocottus having thus won the throne was reigning over India when Seleucus was laying the foundations of his future greatness. Seleucus, having made a treaty with him and otherwise settled his affairs in the East, returned home to prosecute the war with Antigonus.'

The same transactions are referred to in Appian's Ρωμαικα, book Συριακη, chapter 55:

' [Seleucus] crossed the Indus and waged war on Androcottus, king of the Indians who dwelt about it, until he made friends and entered into relations of marriage with him.'

According to Strabo, Seleucus ceded to Sandrocottus a tract of land to the west of the Indus, entering into a matrimonial alliance with him and receiving in exchange five hundred elephants. We know from various sources that Megasthenes became the ambassador of Seleucus at Chandragupta's court. Strabo adds that Deimachus was sent on an embassy to Chandragupta's son, whom he calls Amitrochades :

' Megasthenes and Deïmachus were sent on an embassy, the former to Sandrocottus at Palimbothra, the other to Amitrochades his son; and they left accounts of their sojourn in the country'.

It may be concluded from this interesting notice that Chandragupta's son and successor Bindusāra had the surname Amitraghāta, i. e. ' the slayer of enemies'. The same king is referred to as a contemporary of Antiochus (I Soter of Syria) in a curious anecdote preserved by Athenaeus:

' Dried figs were so eagerly desired by all men.....that even Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochus asking him, says Hegesander, to purchase and send him sweet wine, dried figs, and a sophist: and that Antiochus wrote back: " We shall send you dried figs and sweet wine; but it is not lawful in Greece to sell a sophist."'

If this statement of Athenaeus is combined with the preceding one of Strabo, it appears that the friendly intercourse which had existed between Seleucus and Chandragupta, was continued by their respective sons and successors, Antiochus I and Bindusāra-Amitraghāta, and that Megasthenes, the ambassador of Seleucus at the court of Chandragupta, was succeeded by Deïmachus, the ambassador of Antiochus I at the court of Bindusāra-Amitraghāta. From Pliny we learn that another Greek potentate, Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt (B.C. 285-247), sent Dionysius as ambassador to an unnamed Indian king, who may be supposed to have been either Bindusāra or Aśoka.

I now return to the question of Chandragupta's date. Seleucus I Nikator of Syria (B.C. 312-280) 'arrived in Cappadocia in the autumn of 302 [the year preceding the battle of Ipsus]. The march thither from India must have required at least two summers. Consequently, the peace with Chandragupta has to be placed about the summer of 304, or at the latest in the next winter.' Thus the coronation of Chandragupta falls between B.C. 323 (Alexander's death) and 304 (the treaty with Seleucus). As the consolidation of an empire which, as described by Megasthenes in his Ινδικα, reached from Paṭnā to the Indus, must have been a matter of many years, I feel inclined to shift the date of Chandragupta's accession towards the earlier limit and to adopt as a working date the year B.C. 320 which Fleet has proposed. With this starting-point, and if the length of reigns as given in the Mahāvaṃsa is accepted, Chandragupta would have ruled 320-296, and Bindusāra 296-268. Aśoka would have been crowned (four years after his father's death) in B.C. 264. This date is confirmed approximately by Aśoka's thirteenth rock-edict, which, as stated above (p. xxxi), cannot be placed earlier than twelve or thirteen years after his abhisheka. 264—12/13 = 252/251 would be one or two years before the last possible year (B.C. 250) in which all the Greek kings mentioned in that edict were still alive. This synchronism would prove that the date of Chandragupta's coronation, on which that of Aśoka's coronation depends, can hardly be placed later than B.C. 320. It would follow further that the Antiyoka of edict XIII (and probably also of rock-edict II) was not Antiochus I, but Antiochus II (261-246), and that the Alikasudara of edict XIII was not Alexander of Epirus, but Alexander of Corinth (252-c. 244). But we must remember that the above figures rest only on the Ceylonese tradition, while the Purāṇas assign to Bindusāra twenty-five instead of twenty-eight years, and that, accordingly, Chandragupta's coronation might fall about three years later than B.C. 320. Besides, it must be kept in mind that the upper limit of Chandragupta's coronation is the death of Alexander the Great in B.C 323. The working date of B.C. 320 has the advantage of being the mean of the two outside dates 323 and 317.

I now append a list of the regnal dates which are incidentally mentioned in Aśoka's inscriptions, adding in brackets the year B.C. to which each year of his reign may be supposed to correspond.

- Eight years after the coronation (B.C. 256). The king conquered (the country of) the Kaliṅgas ; rock-edict XIII.

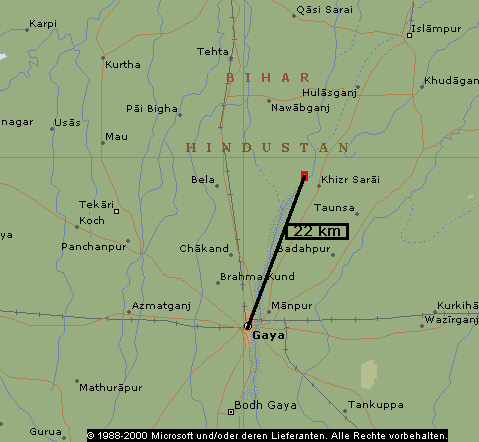

- Ten years after the coronation (B.C. 254). He went (on a visit) to Sambodhi (i.e. Bodh-Gayā); rock-edict VIII.

- Twelve years after the coronation (B.C. 252) :

- He ordered his officers to set out on a complete tour (throughout their charges) every five years ; rock-edict III.

- He promoted morality by public shows of edifying subjects ; rock-edict IV.

- He published rescripts on morality ; pillar-edict VI.

- He gave two caves to the Ājīvikas ; two of the Barābar Hill cave-inscriptions.

- Thirteen years after the coronation (B.C. 251). He appointed superintendents of morality; rock-edict V.

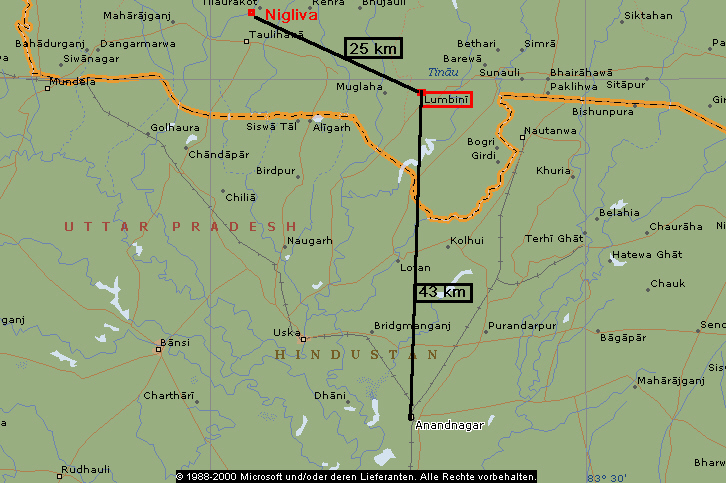

- Fourteen years after the coronation (B.C. 250). He enlarged the Stūpa of Konākamana to the double (of its size); Nigālī Sāgar pillar.

- Nineteen years after the coronation (B.C 245). He gave a cave (to the Ājīvikas); the third Barābar Hill cave-inscription.

- Twenty years after the coronation (B.C. 244). He visited the Buddha's birthplace at Luṃmini and the Stūpa of Konākamana ; Rummindeī and Nigālī Sāgar pillars.

- Twenty-six years after the coronation (B.C. 238). He issued the pillar-edicts I, IV, V, VI.

- Twenty-seven years after the coronation (B.C. 237). He issued the Delhi-Toprā pillar-edict VII."

[Quelle: Inscriptions of Aśoka / new ed. By E. Hultzsch. With 55 plates. -- 1925. -- cxxxi, 260 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm. -- Supersedes: Inscriptions of Aśoka / Prepared by Alexander Cunningham. -- Calcutta, 1887. -- (Corpus inscriptionum indicarum ; vol. I). -- S. XXVIII - XXXVI. -- Dort in den Fußnoten die Belege.]

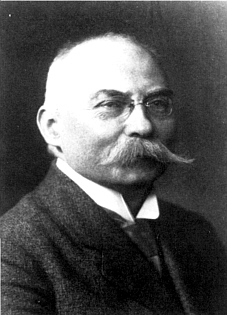

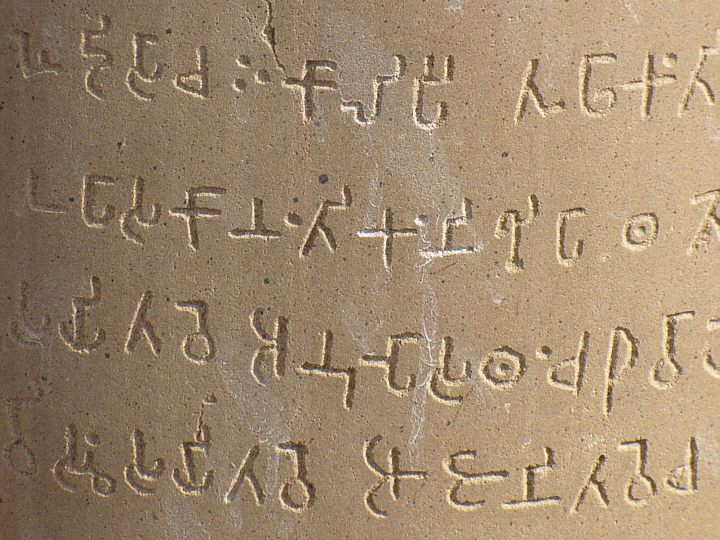

Abb.: Brāhmī-Schrift: Abschrift der Inschrift auf der Säule von Meerut (मेरठ, میرٹھ)

[Bildquelle: JASB 6 (1837), pl. 42. -- Hier nach Falk, 2006, S. 183]

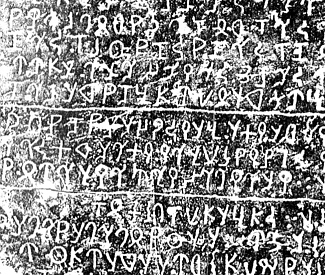

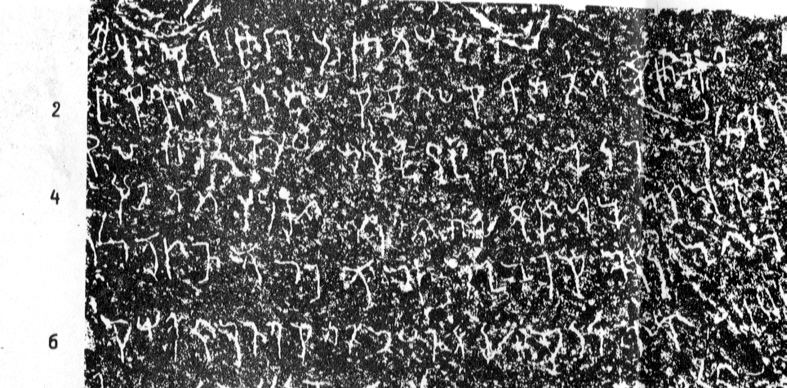

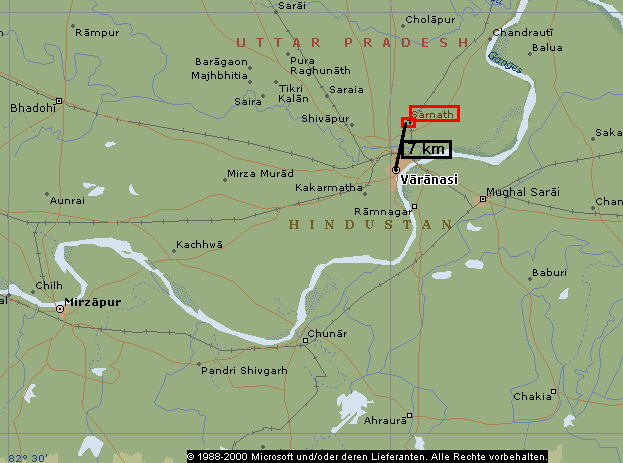

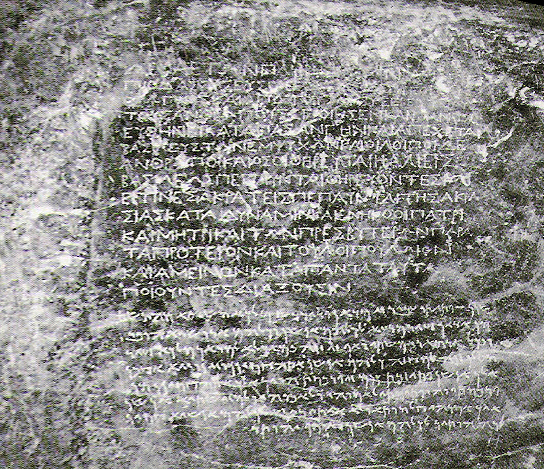

Abb.: Khāroṣṭhī-Schrift: Ausschnitt aus den Felsenedikten

in Shāhbāzgarhī

[Quelle der Abb.: Inscriptions of Aśoka / new ed. By E. Hultzsch. With 55 plates. -- 1925. -- cxxxi, 260 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm. -- Supersedes: Inscriptions of Aśoka / Prepared by Alexander Cunningham. -- Calcutta, 1887. -- (Corpus inscriptionum indicarum ; vol. I). -- Vor S. 57.]

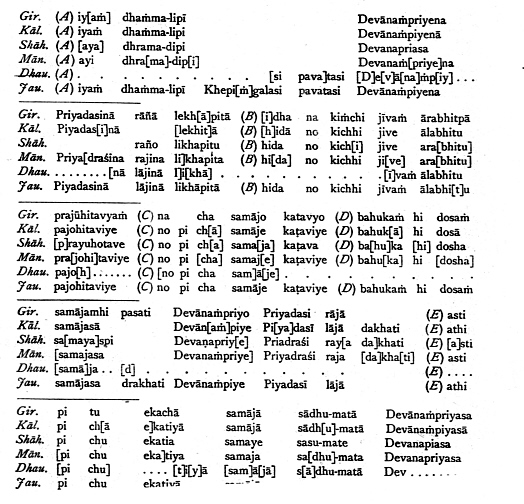

Einen ersten Eindruck von den regionalen Sprachvarianten gibt die synoptische Übersicht der Versionen des ersten Felsenedikts:

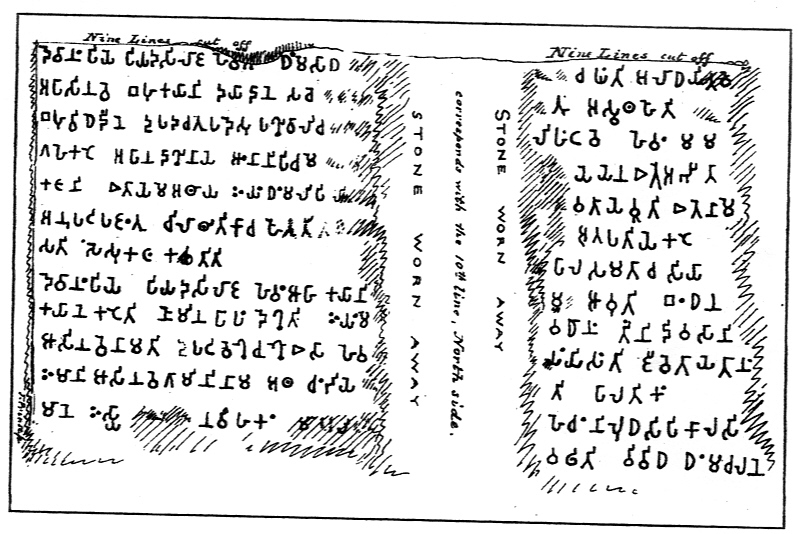

Abb.: Synopsis der Versionen des ersten Felsenedikts

[Quelle der Abb.: Inscriptions of Aśoka / new ed. By E. Hultzsch. With 55 plates. -- 1925. -- cxxxi, 260 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm. -- Supersedes: Inscriptions of Aśoka / Prepared by Alexander Cunningham. -- Calcutta, 1887. -- (Corpus inscriptionum indicarum ; vol. I). -- S. 183.]

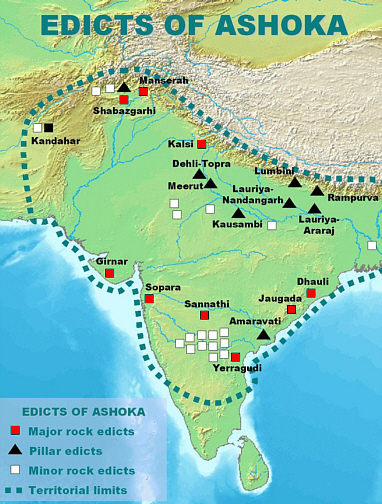

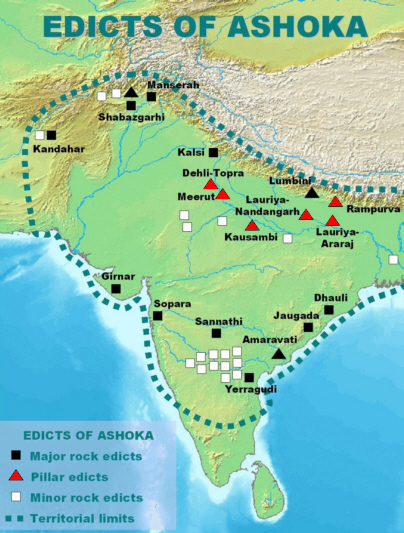

Abb.: Ungefähre Lage der Standorte der Felsenedikte

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Die Felsenedikte befinden sich in:

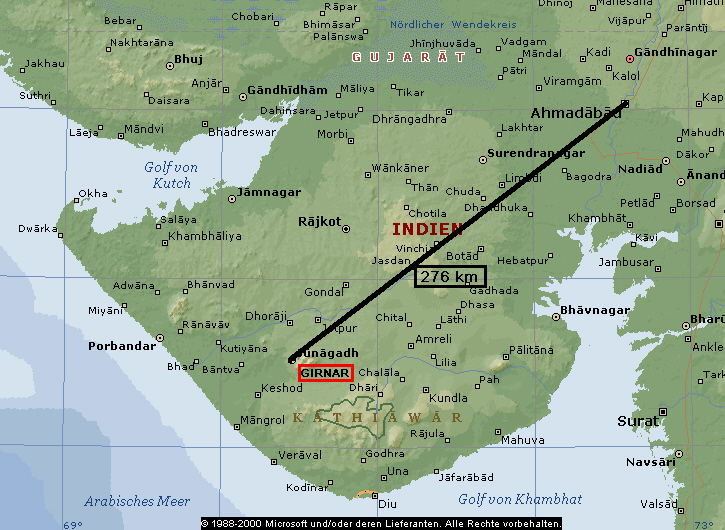

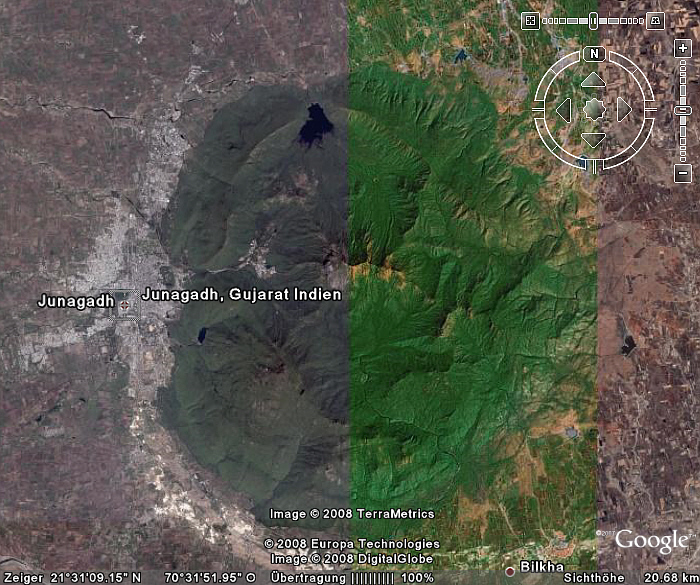

Abb.: Lage des Gīrnār-Berges (ગીરનાર) bei

Jūnāgāḍh (જૂનાગઢ), Gujarat

[©MS-Encarta]

Abb.: Blick auf den Gīrnār-Berg (im Hintergrund), die Felsenedikte sind ungefähr

dort, wohin der Pfeil weist

[Bildquelle: Jouni Lehti. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jlehti/2207220930/. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Gīrnār-Berge

[Bildquelle: ©Google Earth. -- Zugriff am 2008-02-29]

"Gīrnār [ગીરનાર] (also known as "Gīrnār Hill") is a collection of mountains in the Junagadh [જૂનાગઢ] District of Gujarat, India. The tallest of these rises to 945 meters (3600 feet), the highest peak in Gujarat. The five peaks of Gīrnār are topped by 866 intricately carved stone temples. A sturdy stone path — a pilgrimage route for both Hindus and Jains — climbs from peak to peak. It is claimed that there are exactly 9,999 steps from the trailhead to the last temple on the highest peak, but the actual number is roughly 8,000. Every year, a race is held, running from the base of the mountain to the peak and back. The locals in nearby Junagadh insist that the fastest-ever time was 42.36 minutes. However, most people take 5-8 hours to climb the mountain.

In the Hindu religion, the legend is that climbing Gīrnār barefooted earns one a place in Heaven. There is one holy stone; it is said that if a person attempts suicide from that stone then he becomes a part of Heaven.

The nearby Gir Forest serves as sanctuary for the last remaining Asiatic Lions.

It is also famous for the Kathiawadi culture in the adjacent region."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gīrnār. -- Zugriff am 2008-02-28]

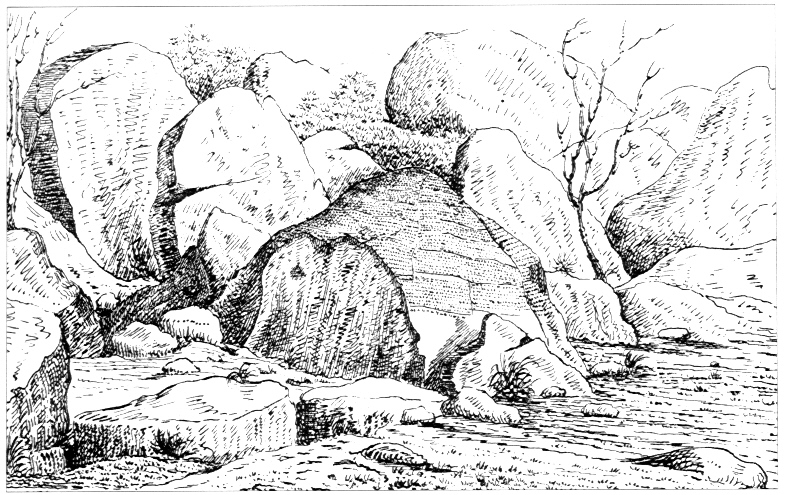

Abb.: Der Fels mit den Inschriften in Gīrnār, wie ihn Postans 1838 sah

[(JASB 7.1838, Pl. XII); hier nach Falk, 2006, S. 119]

Hultzsch schreibt über die Felsenedikte in Gīrnār:

"FIRST PART: THE ROCK-EDICTS The above term is meant to comprise

- the existing versions of the well-known 'fourteen edicts', and

- the two 'separate edicts' which the Dhauli and Jaugaḍa versions substitute for edicts XI to XIII.

It does not include the minor rock-inscriptions, which will be treated in the fourth part.

1. The Gīrnār Rock (Text, p. 1).

This famous set of Aśoka's fourteen edicts is found about a mile to the east of Junāgaṛh, the capital of the Junāgaṛh State in the Kāṭhiāvāṛ Peninsula, 'and at the entry of the dell or gorge which leads into the valley that girdles the mighty and sacred Gīrnār' mountain. The inscription 'covers considerably over a hundred square feet of the uneven surface of a huge rounded and somewhat conical granite boulder, rising 12 feet above the surface of the ground, and about 75 feet in circumference at the base.' The boulder bears, beside Aśoka's edicts, two other valuable documents: An inscription of the Mahākshatrapa Rudradaman records the restoration of the lake Sudarśana, which had been 'originally constructed by the Vaiśya Pushyagupta, the provincial governor (rāshṭriya) of the Maurya king Chandragupta, and subsequently adorned with conduits by the Yavana king Tushāspha for Aśoka the Maurya.' Among local names it mentions Girinagara, i. e. the town of Junāgaṛh or its ancient representative, and Ūrjayat, i. e. the mountain now called Gīrnār. The third inscription on the boulder is dated in the reign of the Gupta king Skandagupta and records further repairs of the lake Sudarśana made in a. d. 456-7 by Chakrapālita, the son of Parṇadatta who was governor of Surāshṭra.

The Aśoka inscription occupies the north-east face of the boulder. The fourteen edicts are arranged in two columns and divided from one another by straight lines. As may be seen on the third of the plates issued with Wilson's article in JRAS, 12. 153 ff., the left column consists of edicts I to V and the right one of edicts VI to XII ; and edicts XIII and XIV are placed below V and XII. When Major James Tod visited Gīrnār in December 1822, the inscription seems to have been intact. Subsequently portions of edicts V and XIII were blasted with gunpowder by the workmen of a pious merchant who constructed a causeway from Junāgaṛh to Gīrnār. At the recommendation of the late Dr. Burgess a shed has been specially built to protect the boulder from the sun and rain.

The first decipherment of the Brāhmī alphabet and, with it, of the Gīrnār inscription, is due to the learning and ingenuity of James Prinsep. His transcript and translation were based on tracings on cloth which had been taken in 1835 by Captain Lang for the Rev. Dr. J. Wilson of Bombay. Fresh copies were made by Lieutenant Postans and Captain Lang in 1838, and by Captain (afterwards General) Le Grand Jacob and Professor Westergaard in 1842. These materials were utilized by Mr. E. Norris for drawing up an improved plate of the Gīrnār inscription, from which Professor H. H. Wilson's transcript and translation in JRAS, vol. 12 (1850), were made. No better materials were available to three other scholars who examined the Gīrnār version, viz. Professor Chr. Lassen (Indische Altertumskunde), E. Burnouf (Lotus de la Bonne Loi ; Paris, 1852), and Professor H. Kern (Over de Jaartelling der Zuidelijke Buddhisten en de Gedenkstukken van Acoka den Buddhist; Amsterdam, 1873).

The first perfectly mechanical estampages of the Gīrnār edicts were prepared in 1875 by Dr. J. Burgess. These were reproduced by collotype in 1876 in ASWI, 2. 98 ff., and also in IA, 5. 257 ff, with an English translation of Kern's Dutch versions of part of the edicts.

A complete edition of the Gīrnār edicts is included in Senart's Inscriptions de Piyadasi, vol. I. An abridged English translation of his work appeared in IA, vols. 9 and 10. In JA (8), 12. 311 ff., Senart added the results of his inspection of the Gīrnār rock in situ. Bühler published a number of corrections and the text of edict XIII in his Beiträge zur Erklärung der Aśoka-Inschriften (ZDMG, vols. 37-48), and the full text of the Gīrnār version in EI, 2. 447 ff. The plates which accompany this article are much clearer than those issued in 1876, but seem to have been touched up by hand. A Collection of Prakrit and Sanskrit Inscriptions printed at Bhavnagar (without year) contains the text, Sanskrit and English translations, and facsimiles, of the Gīrnār edicts.

Two fragments of the lost portion of edict XIII were recovered recently and are now preserved in the Junāgaṛh Museum. Both of them were discussed by Senart (JRAS, 1900. 335 ff), and the second of them also by Bühler (VOJ, 8. 318 ff). Both pieces are shown in the plate which accompanies my transcript of edict XIII.

As regards the Brāhmī alphabet of the Gīrnār inscription I can refer the reader to Bühler's Indian Paleography, edited by Fleet (IA, vol. 33, Appendix), § 16. The chief peculiarity of the Gīrnār alphabet is the addition of the horizontal bar, marking the length of initial ā, at the top of a, while it is elsewhere attached to the middle of the letter. The formation of groups of consonants, and the peculiar way in which the letter r is expressed in combination with other consonants, will be discussed in the chapter on the Gīrnār dialect (below, p. lviii. f.)."

[Quelle: Inscriptions of Aśoka / new ed. By E. Hultzsch. With 55 plates. -- 1925. -- cxxxi, 260 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm. -- Supersedes: Inscriptions of Aśoka / Prepared by Alexander Cunningham. -- Calcutta, 1887. -- (Corpus inscriptionum indicarum ; vol. I). -- S. IXf.]

(A) This rescript on morality has been caused to be

written by king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin.

(B) Here no living being must be killed and sacrificed.

(C) And no festival meeting must be held.

(D) For king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin sees much evil in festival meetings.

(E) But there are also some festival meetings which are considered meritorious

by king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin.

(P) Formerly in the kitchen of king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin many hundred

thousands of animals were killed daily for the sake of curry.

(G) But now, when this rescript on morality is written, only three animals are

being killed (daily) for the sake of curry, (viz.) two peacocks (and) one deer,

(but) even this deer not regularly.

(H) Even these three animals shall not be killed in future.

(A) Everywhere in the dominions of king

Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin, and likewise among (his) borderers, such as the Choḍas, the Pāṇdyas,

the Satiyaputa, the Ketalaputa, even Tāmraparṇī, the Yona king Antiyaka, and

also the

kings who are the neighbours of this Antiyaka,—everywhere two (kinds of) medical

treatment were established by king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin, (viz.) medical

treatment for men and medical treatment for cattle.

(B) And wherever there were no herbs that are beneficial to men and beneficial

to cattle, everywhere they were caused to be imported and to be planted.

(C) Wherever there were no roots and fruits, everywhere they were caused to be

imported and to be planted.

(D) On the roads wells were caused to be dug, and trees were caused to be

planted for the use of cattle and men.

(A) King Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin speaks thus.

(B) (When I had been) anointed twelve years, the following was ordered by me.

(C) Everywhere in my dominions the Yuktas, the Rājūka, and the Prādeśika shall

set out on a complete tour (throughout their charges) every five years for this

very purpose, (viz.) for the following instruction in morality as well as for

other business.

(D) 'Meritorious is obedience to mother and father. Liberality to friends,

acquaintances, and relatives, to Brāhmaṇas and Śramaṇas is meritorious.

Abstention from killing animals is meritorious. Moderation in expenditure (and)

moderation in possessions are meritorious.'

(E) The council (of Mahāmātras) also shall order the Yuktas to register (these

rules) both with (the addition of) reasons and according to the letter.

(A) In times past, for many hundreds

of years, there had ever been promoted the killing of animals and the hurting of

living beings, discourtesy to relatives, (and) discourtesy to Brāhmaṇas and

Śramaṇas.

(B) But now, in consequence of the practice of morality on the part of king

Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin, the sound of drums has become the sound of morality,

showing the people representations of aerial chariots, representations of

elephants, masses of fire, and other divine figures.

(C) Such as they had not existed before for many hundreds of years, thus there

are now promoted, through the instruction in morality on the part of king

Devānāṃpriya

Priyadarśin, abstention from killing animals, abstention from hurting living

beings, courtesy to relatives, courtesy to Brāhmaṇas and Śramaṇas, obedience to

mother (and) father, (and) obedience to the aged.

(D) In this and many other ways is the practice of morality promoted.

(E) And king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin will ever promote this practice of

morality.

(P) And the sons, grandsons, and great-grandsons of king Devānāṃpriya

Priyadarśin will promote this practice of morality until the aeon of destruction

(of the world), (and) will instruct (people) in morality, abiding by morality

(and) by good conduct.

(G) For this is the best work, viz. instruction in morality.

(H) And the practice of morality is not (possible) for (a person) devoid of good

conduct

(I) Therefore promotion and not neglect of this object is meritorious.

(J) For the following purpose has this been caused to be written, (viz. in order

that) they should devote themselves to the promotion of this practice, and that

the neglect (of it) should not be approved (by them).

(K) This was caused to be written by king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin (when he had

been) anointed twelve years.

(A) King Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin

speaks thus.

(B) It is difficult to perform virtuous deeds.

(C) He who starts performing virtuous deeds accomplishes something difficult.

(D) Now, by me many virtuous deeds have been performed.

(E) Therefore (among) my sons and grandsons, and (among) my descendants (who

shall come) after them until the aeon of destruction (of the world), those who

will conform to this (duty) will perform good deeds.

(F) But he who will neglect even a portion of this (duty) will perform evil

deeds.

(G) For sin is easily committed.

(H) In times past (officers) called Mahāmātras of morality (Dharma-mahāmātra)

did not exist before.

(I) But Mahāmātras of morality were appointed by me (when I had been) anointed

thirteen years.

(J) These are occupied with all sects in establishing morality..........of those

who are devoted to morality (even) among the Yoṇas, Kambojas, and Gandhāras, the

Risṭikas and Peteṇikas, and whatever other western borderers (of mine there are).

(K) They are occupied with servants and masters ..........for the..........happiness of those who are devoted to morality, (and) in freeing (them) from

desire (for worldly life).

(L) They are occupied in supporting prisoners (with money).......... (if one

has) children, or with those who are bewitched (i.e. incurably ill ?), or with

the aged.

(M) They are occupied everywhere, both in Pāṭaliputra and in the outlying

..........and whatever other relatives of mine (there are).

(N) These Mahāmātras of morality..........whether one is eager for

morality..........

(O) For the following purpose has this rescript on morality been written..........

(A) King Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin

speaks thus.

(B) In times past neither the disposal of affairs nor the submission of reports

at any time did exist before.

(C) But I have made the following (arrangement).

(D) Reporters are posted everywhere, (with instructions) to report to me the

affairs of the people at any time, while I am eating; in the harem, in the inner

apartment, even at the cowpen, in the palanquin, and in the parks.

(E) And everywhere I am disposing of the affairs of the people.

(F) And if in the council (of Mahāmātras) a dispute arises, or an amendment is

moved, in connexion with any donation or proclamation which I myself am ordering

verbally, or (in connexion with) an emergent matter which has been delegated to

the Mahāmātras, it must be reported to me immediately, anywhere, (and) at any

time.

(G) Thus I have ordered.

(H) For I am never content in exerting myself and in dispatching business.

(I) For I consider it my duty (to promote) the welfare of all men.

(J) But the root of that (is) this, (viz.) exertion and the dispatch of business.

(K) For no duty is more important than (promoting) the welfare of all men.

(L) And whatever effort I am making, (is made) in order that I may; discharge

the debt (which I owe) to living beings, (that) I may make them happy in this (world),

and (that) they may attain heaven in the other (world).

(M) For the following purpose has this rescript on morality been caused to be

written, (viz.) that it may last long, and that my sons, grandsons, and

great-grandsons may conform to this for the welfare of all men.

(N) But it is difficult to accomplish this without great zeal.

(A) King Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin

desires (that) all sects may reside everywhere.

(B) (For) all these desire both self-control and purity of mind.

(C) But men possess various desires (and) various passions.

(D) Either they will fulfil the whole, or they will fulfil (only) a portion (of

their duties).

(E) But even one who (practises) great liberality, (but) does not possess

self-control, purity of mind, gratitude, and firm devotion, is very mean.

(A) In times past kings used to set

out on pleasure-tours.

(B) On these (tours) hunting and other such pleasures were (enjoyed).

(C) But when king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin had been anointed ten years, he went

to Saṃbodhi.

(D) Therefore these tours of morality (were undertaken).

(E) On these (tours) the following takes place, (viz.) visiting Brāhmaṇas and

Śramaṇas and making gifts (to them), visiting the aged and supporting (them)

with gold, visiting the people of the country, instructing (them) in morality,

and questioning (them) about morality, as suitable for this (occasion).

(F) This second period (of the reign) of king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin becomes a

pleasure in a higher degree.

(A) King Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin

speaks thus.

(B) Men are practising various ceremonies during illness, or at the marriage of

a son or a daughter, or at the birth of a son, or when setting out on a journey

on these and other (occasions) men are practising various ceremonies.

(C) But in such (cases) women are practising many and various vulgar and useless

ceremonies.

(D) Now, ceremonies should certainly be practised.

(E) But ceremonies like these bear little fruit indeed.

(F) But the following practice bears much fruit, viz. the practice of morality.

(G) Herein the following (are comprised), (viz.) proper courtesy to slaves and

servants, reverence to elders, gentleness to animals, (and) liberality to

Brāhmaṇas and Śramaṇas ; these and other such (virtues) are called the practice

of morality.

(H) Therefore a father, or a son, or a brother, or a master ought to say:— 'This

is meritorious. This practice should be observed until the (desired) object is

attained.'

(I) And it has been said also: 'Gifts are meritorious.'

(J) But there is no such gift or benefit as the gift of morality or the benefit

of morality.

(K) Therefore a friend, or a well-wisher, or a relative, or a companion should

indeed admonish (another) on such and such an occasion:—'This ought to be done;

this is meritorious. By this (practice) it is possible to attain heaven.'

(L) And what is more desirable than this, viz. the attainment of heaven ?

(A) King Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin does

not think that either glory or fame conveys much advantage, except (on account

of his aim that) in the present time, and in the distant (future), men may (be

induced) by him to practise obedience to morality, and that they may conform to

the duties of morality.

(B) On this (account) king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin is desiring glory and fame.

(C) But whatever effort king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin is making, all that (is)

for the sake of (merit) in the other (world), (and) in order that all (men) may

run little danger.

(D) But the danger is this, viz. demerit.

(E) But it is indeed difficult either for a lowly person or for a high one to

accomplish this without great zeal (and without) laying aside every (other aim).

(F) But among these (two) it is indeed (more) difficult to accomplish for a high

(person).

(A) King Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin

speaks thus.

(B) There is no such gift as the gift of morality, or acquaintance through

morality, or the distribution of morality, or kinship through morality.

(C) Herein the following are (comprised), (viz.) proper courtesy to slaves and

servants, obedience to mother (and) father, liberality to friends, acquaintances,

and relatives, to Brāhmaṇas and Śramaṇas, (and) abstention from killing animals.

(D) Concerning this a father, or a son, or a brother, or a friend, an

acquaintance, or a relative, (or) even (mere) neighbours, ought to say: 'This

is meritorious. This ought to be done.'

(E) If one is acting thus, the attainment of (happiness) in this world is (secured),

and endless merit is produced in the other (world) by that gift of morality.

(A) King Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin is

honouring all sects: both ascetics and householders; both with gifts and with

honours of various kinds he is honouring them.

(B) But Devānāṃpriya does not value either gifts or honours so (highly) as (this),

(viz.) that a promotion of the essentials of all sects should take place.

(C) But a promotion of the essentials (is possible) in many ways.

(D) But its root is this, viz. guarding (one's) speech, (i. e.) that neither

praising one's own sect nor blaming other sects should take place on improper

occasions, or (that) it should be moderate in every case.

(E) But other sects ought to be duly honoured in every case.

(F) If one is acting thus, he is both promoting his own sect and benefiting

other sects.

(G) If one is acting otherwise than thus, he is both hurting his own sect and

wronging other sects, as well.

(H) For whosoever praises his own sect or blames other sects,—all (this) out of

devotion to his own sect, (i. e.) with the view of glorifying his own sect,—if

he is acting thus, he rather injures his own sect very severely.

(I) Therefore concord alone is meritorious, (i. e.) that they should both hear

and obey each other's morals.

(J) For this is the desire of Devānāṃpriya, (viz.) that all sects should be full

of learning, and should be pure in doctrine.

(K) And to those who are attached to their respective (sects)ought to be spoken

to (as follows).

(L) Devānāṃpriya does not value either gifts or honours so (highly) as (this),

(viz.) that a promotion of the essentials of all sects should take place.

(M) And many (officers) are occupied for this purpose, (viz.) the Mahāmātras of

morality, the Mahāmātras controlling women, the inspectors of cowpens, and other

classes (of officials).

(N) And this is the fruit of it, (viz.) that both the promotion of one's own

sect takes place, and the glorification of morality.

(A)......... . the Kaliṅgas..........

(B)..........one hundred thousand in number were those who were slain

there, (and) many times as many those who died.

(C) After that, now that (the country of) the Kaliṅgas has been taken, a zealous

study of morality..........

(D).....[the repentance] of Devānāṃpriya..........

(E)..........slaughter, death, and deportation of people, this is considered

very painful and deplorable by Devānāṃpriya.

(G) . . ........Brāhmaṇas or Śramaṇas, [or] other .......... obedience to

mother (and) to father, obedience to elders..........to friends, acquaintances,

companions, and relatives, [to] slaves..........or deportation of (their)

beloved ones.

(H)..........[companions] and relatives are then incurring misfortune,

this (misfortune) as well becomes an injury to those (persons). (I) This is

shared [by] all ..........

(J)..........these classes..........except among the Yonas..........where men are not indeed attached to some sect.

(K) As many people as at that time..........part is considered deplorable by

Devanam[priya],

(L)..........what can be forgiven.

(M) And even the forests which are (included) in the dominions of Devānāṃpriya

..........

(N) They are [told]..........of Devānāṃpriya..........

(O)..........towards all beings abstention from hurting, self-control,

impartiality, and kindness.

(Q)..........has been won by [Devā]nāṃpriya here and among all..........the Yona king, and beyond him four kings, (viz.) Turamāya, Antekina, Magā..........

(R).....here in the king's territory, [among] the Yonas and Kambo[jas]

..........among the [A]ndhras and Pārindas,—everywhere (people) are conforming

to Devānāṃpriya's instruction in morality.

(S) Even where the envoys..........and the instruction in morality, are

conforming to morality..........

(T)..........this conquest,—a conquest (won) in every respect (and)

repeatedly,—causes the feeling of satisfaction.

(U) This satisfaction has been obtained (by me) at the conquest by morality.

(W)..........[Devānā]ṃpriya.

(X) For the following purpose this [rescript] on morality..........should not

think that a [fresh] conquest ought to be made, (that), if a conquest does

please them, mercy..........

(Y)..........in the other world.

(AA)..........both in this world and in the other world.

Unterhalb des 13. Felsenedikts, rechte Seite:

............. the entirely white elephant bringing indeed happiness to the whole world.

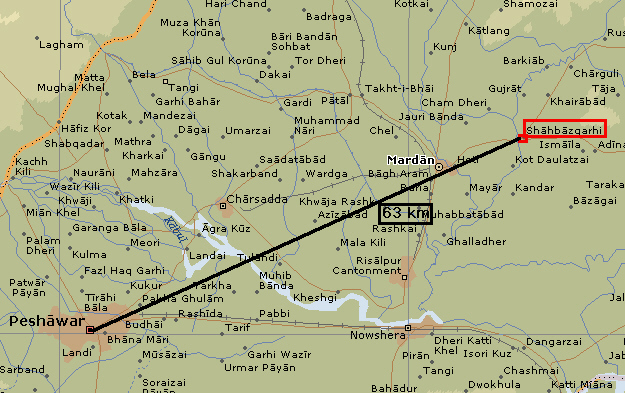

Shāhbāzgarhī, Mardan (مردان) District, North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) (شمال مغربی سرحدی صوبہ), Pakistan

Abb.: Lage von Shāhbāzgarhī

[©MS Encarta]

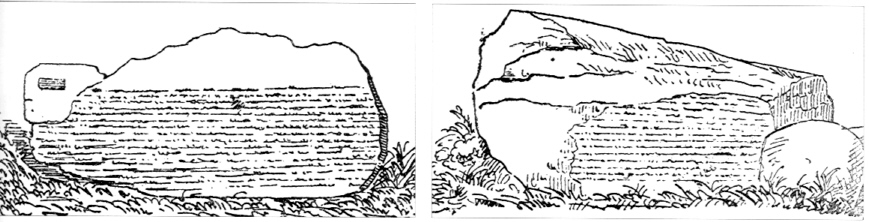

Abb.: Lage der Felsedikte 1 - 11 (links) und 13 - 14 (rechts)

[nach Cunningham, 1877, Pl. XXIX; hier nach Falk, 2006, S. 133]

Abb.: Lage der Felsedikte, Shāhbāzgarhī

[Bildquelle: Livius. --

http://www.livius.org/man-md/mauryas/mauryas.html. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-05.

-- "© Jona Lendering. Photos can be downloaded and used for non-commercial

purposes, but you have to acknowledge Livius."]

Abb.: Felsedikte, Shāhbāzgarhī

[Bildquelle: Livius. --

http://www.livius.org/a/pakistan/shahbazgarhi/shahbazgarhi.html. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-05.

-- "© Jona Lendering. Photos can be downloaded and used for non-commercial

purposes, but you have to acknowledge Livius."]

Abb.: Felsedikte, Shāhbāzgarhī

[Bildquelle: Livius. --

http://www.livius.org/a/pakistan/shahbazgarhi/shahbazgarhi.html. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-05.

-- "© Jona Lendering. Photos can be downloaded and used for non-commercial

purposes, but you have to acknowledge Livius."]

Hultzsch schreibt über die Felsenedikte in Shāhbāzgarhī:

"III. The Shāhbāzgaṛhī Rock (Text, p. 50). While the alphabet of the two preceding sets of the fourteen edicts is the Brāhmī, this one is written in those north-western cursive characters running from the right to the left which used to be called Indo-Bactrian or Ariano-Pali, but to which Bühler restored the indigenous name Kharoshṭhī. The honour of the decipherment of this alphabet is divided between Prinsep, Lassen, Norris, and Cunningham. A number of Kharoshṭhī letters had been already identified from bilingual coins of the Indo-Grecian and Indo-Scythian kings, before the Shāhbāzgaṛhī inscription was discovered.

Shāhbāzgaṛhī is a village on the Makām river, nine miles from Mardān, the headquarters of the Yūsufzai subdivision of the Peshāvar district of the North-West Frontier Province. The inscription is about half a mile distant from this village and two miles from the village of Kapurdagaṛhī. It 'is engraved on a large shapeless mass of trap rock, lying about 80 feet up the slope of the hill, with its western face looking downwards towards the village of Shāhbāzgaṛhī.' The edicts I to XI are on the east face (edict VII being entered on the left at the top of the rock), and the edicts XIII and XIV are on the west face. Edict XII is engraved on a separate boulder, which is now enclosed within a wall.

M. (afterwards General) Court, of Mahārāja Ranjit Singh's service, first notified the existence of a Kharoshṭhī inscription near Shāhbāzgaṛhī in 1836 and gave a few letters copied by himself. In 1838 Captain Burnes, being at Peshāvar, sent an agent to Shāhbāzgaṛhī, who returned with an imperfect paper impression. In the same year Mr. C. Masson obtained through a young man a partial impression on calico. He then proceeded to the spot himself and prepared fresh copies. His zeal deserves much praise, as at that time a journey through such an unpacified tract involved considerable personal risk. Masson's materials were brought to Europe and examined by Norris, who first read in them the word Devanaṃpiyasa. With the help of this discovery, Dowson ascertained that the portion of which a facsimile is given in JRAS, 8 (1846). 303, is a duplicate of edict VII of the Gīrnār inscription. Norris further found that the front of the rock contained the edicts I to XI, and traced on the back of it portions of edict XIII. He also published the text of edict VII (id., p. 306 f.). In 1850 Wilson contributed a tentative transcript of both faces of the Shāhbāzgaṛhī rock, accompanied by plates drawn by Norris from Masson's copies (id., 12. 153 ff.). An independent eye-copy of the Shāhbāzgaṛhī inscription was prepared by Cunningham (Inscriptions of Aśoka, p. 10).

Senart's transcript in his Inscriptions de Piyadasi, vol. I, had still to be based on the same imperfect materials. Pandit Bhagvanlal Indraji furnished transcripts of the Shāhbāzgaṛhī and other versions of edict I (IA, 10. 107) and of edict VIII (JBBRAS, 15. 284). After the return from a trip to India, Senart published the results of his examination of edicts I to XI in situ (JA (8), 11. 521 ff.). The missing edict XII was discovered on a separate boulder by Captain Deane and edited both by Senart (id., p. 511 ff.) and by Bühler (EI, 1. 16 ff.). The latter published the whole Shāhbāzgaṛhī version in ZDMG, 43. 128 ff., and a fresh transcript and a translation of it in EI, 2. 447 ff., from estampages by Burgess. The only portions of which mechanical copies have been made public so far are edict VII (ZDMG, vol 43) and edict XII (EI, 1. 16)."

[Quelle: Inscriptions of Aśoka / new ed. By E. Hultzsch. With 55 plates. -- 1925. -- cxxxi, 260 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm. -- Supersedes: Inscriptions of Aśoka / Prepared by Alexander Cunningham. -- Calcutta, 1887. -- (Corpus inscriptionum indicarum ; vol. I). -- S. XIf.]

Hultsch's Übersetzung:

(A) When king

Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin had been anointed eight years, (the country of) the

Kaliṅgas was conquered by (him).

(B) One hundred and fifty thousand in number were the men who were deported

thence, one hundred thousand in number were those who were slain there, and many

times as many those who died.

(C) After that, now that (the country of) the Kaliṅgas has been taken,

Devānāṃpriya (is devoted) to a zealous study of morality, to the love of

morality, and to the instruction (of people) in morality.

(D) This is the repentance of Devānāṃpriya on account of his conquest of (the

country of) the Kaliṅgas.

(E) For, this is considered very painful and deplorable by Devānāṃpriya, that,

while one is conquering an unconquered (country), slaughter, death, and

deportation of people (are taking place) there.

(F) But the following is considered even more deplorable than this by

Devānāṃpriya.

(6) (To) the Brāhmaṇas or Śramaṇas, or other sects or householders, who are

living there, (and) among whom the following are practised: obedience to those

who receive high pay, obedience to mother and father, obedience to elders,

proper courtesy to friends, acquaintances, companions, and relatives, to slaves

and servants, (and) firm devotion,—to these then happen injury or slaughter or

deportation of (their) beloved ones.

(H) Or, if there are then incurring misfortune the friends, acquaintances,

companions, and relatives of those whose affection (for the latter) is

undiminished, although they are (themselves) well provided for, this (misfortune)

as well becomes an injury to those (persons) themselves.

(I) This is shared by all men and is considered deplorable by Devānāṃpriya.

(J)

And there is no (place where men) are not indeed attached to some sect.

(K) Therefore even the hundredth part or the thousandth part of all those people

who were slain, who died, and who were deported at that time in Kaliṅga, (would)

now be considered very deplorable by Devānāṃpriya.

(L) And Devānāṃpriya thinks that even (to one) who should wrong (him), what can

be forgiven is to be forgiven.

(M) And even (the inhabitants of) the forests which are (included) in the

dominions of Devānāṃpriya, even those he pacifies (and)

converts.

(N) And they are told of the power (to punish them) which Devānāṃpriya (possesses)

in spite of (his) repentance, in order that they may be ashamed (of their crimes)

and may not be killed.

(O) For Devānāṃpriya desires towards all beings abstention from hurting,

self-control, (and) impartiality in (case of) violence.

(P) And this conquest is considered the principal one by Devānāṃpriya, viz. the

conquest by morality.

(Q) And this (conquest) has been won repeatedly by Devānāṃpriya both here and

among all (his) borderers, even as far as at (the distance of) six hundred

yojanas, where the Yona king named Antiyoka (is ruling), and beyond this

Antiyoka, (where) four—4—kings (are ruling), (viz. the king) named Turamaya, (the

king) named Antikini, (the king) named Maka, (and the king) named Alikasudara,

(and) towards the south, (where) the Choḍas and Pāṇḍyas (are ruling), as far as

Tāmraparṇī.

(R) Likewise here in the king's territory, among the Yonas and Kamboyas, among

the Nabhakas and Nabhitis, among the Bhojas and Pitinikas, among the Andhras and

Palidas,—everywhere (people) are conforming to Devānāṃpriya's instruction in

morality.

(S) Even those to whom the envoys of Devānāṃpriya do not go, having heard of the

duties of morality, the ordinances, (and) the instruction in morality of

Devānāṃpriya, are conforming to morality and will conform to (it).

(T) This conquest, which has been won by this everywhere,—a conquest (won)

everywhere (and) repeatedly,—causes the feeling of satisfaction.

(U) Satisfaction has been obtained (by me) at the conquest by morality.

(V) But this satisfaction is indeed of little (consequence).

(W) Devānāṃpriya thinks that only the fruits in the other (world) are of great (value).

(X) And for the following purpose has this rescript on morality been written, (viz.)

in order that the sons (and) great-grandsons (who) may be (born) to me, should

not think that a fresh conquest ought to be made, (that), if a conquest does

please them, they should take pleasure in mercy and light punishments, and (that)

they should regard the conquest by morality as the only (true) conquest

(Y) This (conquest bears fruit) in this world (and) in the other world.

(Z) And let there be (to them) pleasure in the abandonment of all (other aims),

which is pleasure in morality.

(AA) For this (bears fruit) in this world (and) in the other world.

(A) These rescripts on morality have

been caused to be written by king Devānāṃpriya Priyadarśin either in an abridged

(form), or of middle (size), or at full length.

(B) And the whole was not suitable everywhere.

(C) For (my) dominions are wide, and much has been written, and I shall cause

still (more) to be written.

(D) And some of this has been stated again and again because of the charm of

certain topics, (and) in order that men should act accordingly.

(E) In some instances (some) of this may have been written incompletely, either

on account of the locality, or because (my) motive was not liked, or by the

fault of the writer.

In Dhaulī und Jaugaḍa, beide im heutigen Orissa, gibt es zwei Sonderfelsedikte, die an den anderen Orten mit Felsedikten nicht vorkommen.

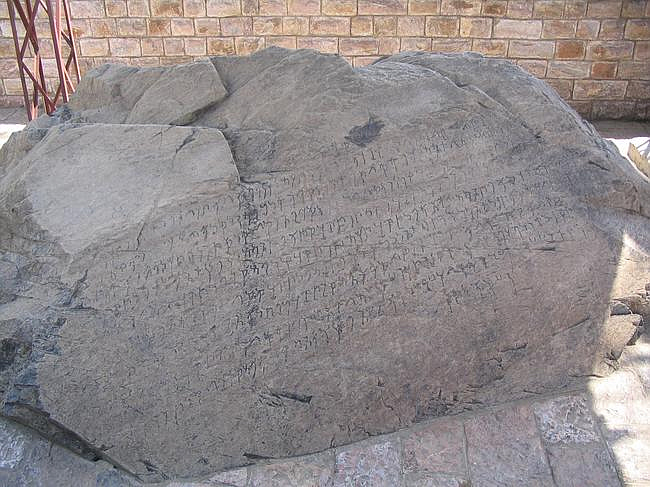

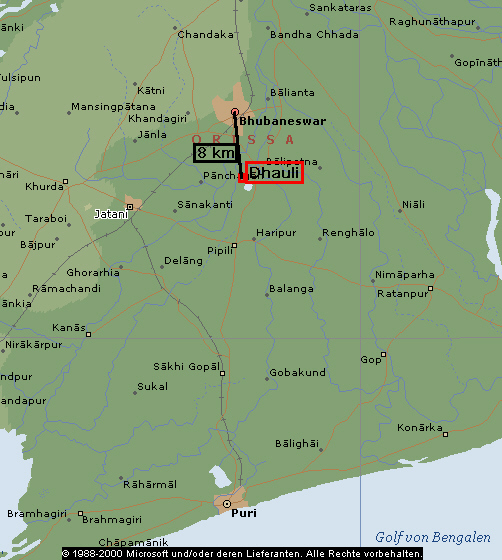

Abb.: Lage von Dhaulī, Pūri District, Orissa (ଓଡ଼ିଆ) - 20°11' N;

85°50' E

[©MS Encarta]

Abb.: Dhaulī Hill

[Bildquelle: ©Google Earth. -- Zugriff am 2008-02-29]

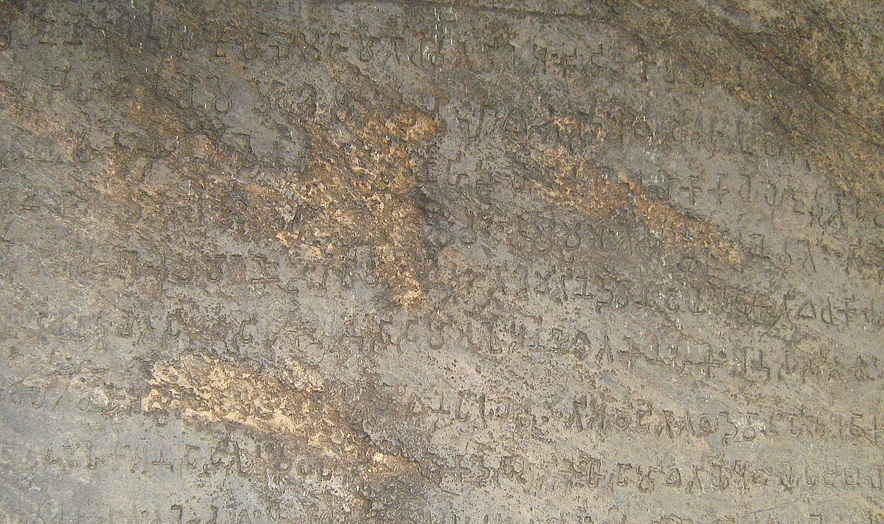

Abb.: Felsenedikt, Dhaulī, Ausschnitt

[Bildquelle: vegdevil. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/vegdevil/915850174/. -- Zugriff am 2008-02-29.

--

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Hultzsch schreibt über die Felsenedikte in Dhauli:

"V. The Dhauli Rock (Text, p. 84). Dhauli is a village in the Khurdā subdivision of the Purī district, Orissa, about seven miles south of Bhuvanesvar. The inscribed rock near the village was discovered in 1837 by Lieutenant Kittoe, who calls it 'Aswastama'. It 'is situated on a rocky eminence forming one of a cluster of hills, three in number, on the south bank of the Dyah river.'

'The hills before alluded to rise abruptly from the plains and occupy a space of about five furlongs by three; they have a singular appearance from their isolated position, no other hills being nearer than eight or ten miles. They are apparently volcanic, and composed of upheaved breccia with quartzose rock intermixed.'

'The Aswastama is situated on the northern face of the southernmost rock near its summit; the rock has been hewn and polished for a space of fifteen feet long by ten in height, and the inscription deeply cut thereon.'

'Immediately above the inscription is a terrace sixteen feet by fourteen, on the right side of which (as you face the inscription) is the fore half of an elephant, four feet high, of superior workmanship; the whole is hewn out of the solid rock.'

While Prinsep was examining a lithograph of Kittoe's copies, he found that the greater part of the Dhauli inscription was identical with the Gīrnār edicts (JASB, 7. 157). He further ascertained that the Dhauli rock omits edicts XI to XIII of the Gīrnār version, but compensates for them by two separate edicts (id., p. 219). These two he edited with a tentative translation (id., p. 438 ff.), adding Kittoe's lithograph of the whole Dhauli inscription (id., plate 10). As may be seen on this plate, the inscription is arranged in three columns. The middle column contains edicts I to VI, and the right column edicts VII to X and XIV, and below them, within a border of straight lines, the second separate edict, while the first separate edict occupies the whole of the left column.

Cunningham showed that it would be more correct to exchange the two designations 'first and second separate edict': the separate edict engraved in continuation of edict XIV ought to be called No. I, and the one engraved separately on the left No. II. This order is confirmed by the Jaugaḍa rock (No. VII, below) where Prinsep's No. II is actually placed above No. I. But as all editors (besides Kern) have followed Prinseps arrangement, a change of numbers would now lead to much contusion, and it will be sufficient to keep in mind that the separate edict No. I was engraved after No. II.

The two separate edicts were re-edited and translated by Burnouf (Lotus, p. 671ff.) and, from Cunningham's copies, by Kern (JRAS, 1880. 379 ff.). Senart's edition of them was based on estampages by Burgess. The same applies to Bühler's editions of the Dhauli version. He published the whole of it twice: once in German (ZDMG, 39. 489 ff., and 41. 1 ff.) and once in English (ASSI, I. 114 ff.). His second edition is accompanied by photo-lithographs (plates 64-66)."

[Quelle: Inscriptions of Aśoka / new ed. By E. Hultzsch. With 55 plates. -- 1925. -- cxxxi, 260 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm. -- Supersedes: Inscriptions of Aśoka / Prepared by Alexander Cunningham. -- Calcutta, 1887. -- (Corpus inscriptionum indicarum ; vol. I). -- S. XIIIf.]

(A) At the word of Devānāṃpriya, the

Mahāmātras at

Tosalī, (who are) the judicial officers of the city, have to be told (thus).

(B) Whatever I recognize (to be right), that I strive to carry out by deeds, and

to accomplish by (various) means.

(C) And this is considered by me the principal means for this object, viz. (to

give) instruction to you.

(D) For you are occupied with many thousands of men, with the object of gaining

the affection of men.

(E) All men are my children.

(F) As on behalf of (my own) children I desire that they may be provided with

complete welfare and happiness in this world and in the other world, the same I

desire also on behalf of [all] men.

(G) And you do not learn how far this (my) object reaches.

(H) Some single person only learns this, (and) even he (only) a portion, (but)

not the whole.

(I) Now you must pay attention to this, although you are well provided for.

(J) It happens in the administration (of justice) that a single person suffers

either imprisonment or harsh treatment,

(K) In this case (an order) cancelling the imprisonment is (obtained) by him

accidentally, while [many] other people continue to suffer.

(L) In this case you must strive to deal (with all of them) impartially.

(M) But one fails to act (thus) on account of the following dispositions: envy,

anger, cruelty, hurry, want of practice, laziness, (and) fatigue.

(N) (You) must strive for this, that these dispositions may not arise to you.

(O) And the root of all this is the absence of anger and the avoidance of hurry.

(P) He who is fatigued in the administration (of justice), will not rise; but

one ought to move, to walk, and to advance.

(Q) He who will pay attention to this, must tell you: 'See that (you) discharge

the debt (which you owe to the king); such and such is the instruction of Devānāṃpriya.'

(R) The observance of this produces great fruit, (but its) non-observance (becomes)

a great evil.

(S) For if one fails to observe this, there will be neither attainment of heaven

nor satisfaction of the king.

(T) For how (could) my mind be pleased if one badly fulfils this duty ?

(U) But if (you) observe this, you will attain heaven, and you will discharge

the debt (which you owe) to me.

(V) And this edict must be listened to (by all) on (every day of) the

constellation Tishya.

(W) And it may be listened to even by a single (person) also on frequent (other)

occasions between (the days of) Tishya.

(X) And if (you) act thus, you will be able to fulfil (this duty).

(Y) For the following purpose has this rescript been written here, (viz.) in

order that the judicial officers of the city may strive at all times (for this),

[that] neither undeserved fettering nor undeserved harsh treatment are happening

to [men].

(Z) And for the following purpose I shall send out every five years [a Mahāmātra]

who will be neither harsh nor fierce, (but) of gentle actions, (viz. in order to

ascertain)

whether (the judicial officers), paying attention to this object,.....are acting

thus, as

my instruction (implies).

(AA) But from Ujjayinī also the prince (governor) will send out for the same

purpose.....a person of the same description, and he will not allow (more than)

three years to pass (without such a deputation).

(BB) In the same way (an officer will be deputed) from Takshaśilā also.

(CC) When.....these Mahāmātras will set out on tour, then, without neglecting

their own duties, they will ascertain this as well, (viz.) whether (the judicial

officers) are carrying out this also thus, as the instruction of the king (implies).

(A) At the word of Devānāṃpriya, the prince (governor) and

the Mahāmātras at Tosalī have to be told (thus).

(B) Whatever I recognize (to be right), that..........and to accomplish by

(various) means.

(C) And this is considered by me the principal means for this object, viz.

...........to you.

(D)..........my.....

(E) As on behalf of (my own) children I desire that they may be provided with

complete welfare and happiness in this world and in the other world, thus..........

(F) It might occur to (my) unconquered borderers (to ask): 'What does the king

desire with reference to us ?'

(G) [This] alone is my wish with reference to the borderers, that they may learn

that Devānāṃpriya..........that they may not be afraid of me, but may have

confidence (in me); that they may obtain only happiness from me, not misery;

that they may [learn] this, that Devānāṃpriya will forgive them what can be

forgiven ; that they may (be induced) by me (to) practise morality; (and) that

they may attain (happiness in) this world and (in) the other world

(H) For the following purpose I am instructing you, (viz. that) I may discharge

the debt (which I owe to them) by this, that I instruct (you) and inform (you)

of (my) will, i. e. my unshakable resolution and vow.

(I) Therefore, acting thus, (you) must fulfil (your) duty and must inspire

confidence to them, in order that they may learn that Devānāṃpriya is to them

like a father, that Devānāṃpriya loves them like himself, and that they are to

Devānāṃpriya like (his own) children.

(J) Therefore, having instructed (you), and having informed you of (my) will, I

shall have (i. e. entertain) officers in (all) provinces for this object.

(K) For you are able to inspire confidence to those (borderers) and (to secure

their) welfare and happiness in this world and in the other world.

(L) And if (you) act thus, you will attain heaven, and will discharge the debt (which

you owe) to me.

(M) And for the following purpose has this rescript been written here, (viz.) in

order that the Mahāmātras may strive at all times to inspire confidence to those

borderers (of mine) and (to induce them) to practise morality.

(N) And this rescript must be listened to (by all) every four months on (the day

of) the constellation Tishya.

(O) But if desired, it may be listened to even by a single (person) also on

frequent (other) occasions between (the days of) Tishya.

(P) If (you) act thus, you will be able to carry out (my orders).

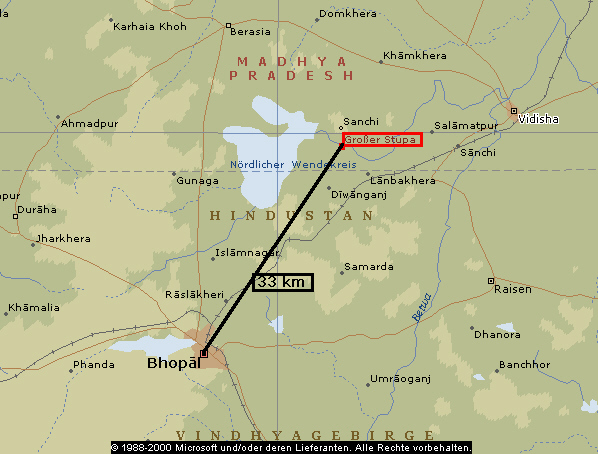

Abb.: Ungefähre Lage der (ursprünglichen) Standorte der großen Säulenedikte

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Die großen Säulenedikte befinden/befanden sich auf Säulen in

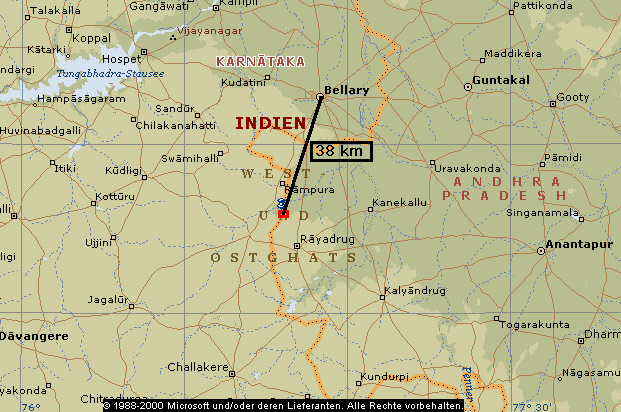

Abb.: Lage von Khizrābād, Haryana, in dessen Nähe sich die Säule von Toprā

ursprünglich befunden haben soll

[©MS Encarta]

Hultzsch schreibt über die Säulenedikte von Delhi-Toprā:

"SECOND PART: THE PILLAR-EDICTS This term is meant to comprise the Aśoka inscriptions on the Delhi-Toprā pillar and on the five other pillars which bear six of the seven edicts inscribed on it. The minor pillar-inscriptions will be treated separately in the third part. The ' Queen's edict' and the ' Kauśāmbī edict', however, are included in the second part, because they are inscribed on the Allahabad-Kosam column which bears also six of the chief pillar-edicts.

I. The Delhi-Toprā Pillar (Text, p. 119).

This famous monument 'is a single shaft of pale pinkish sandstone, 42 feet 7 inches in length, of which the upper portion, 35 feet in length, has received a very high polish, while the remainder is left quite rough.' It used to be known by the names of 'Bhīmasena's pillar', 'Golden pillar',' Fīrōz Shāh's pillar', and 'Delhi-Siwālik pillar'. Shams-i Sirāj, a historian of Firōz Shāh (A. D. 1351-88), informs us that it stood originally 'in the village of Tobra, in the district of Sālaura and Khizrābād, in the hills'; that Sultan Firōz had it carried to Delhi; and that he erected it again on the top of his palace at Firōzābād. From Tobra near Khizrābād, which was ninety kōs from Delhi, the column was carried on a truck with forty-two wheels to the bank of the Jamnā, whence it was floated down the river to Firōzābād (Delhi) on a number of large boats.

Cunningham (Arch. Reports, 14. 78 f.) identified the village of Tobra, where the pillar stood originally, with the present Toprā, on the direct line between Ambālā and Sirsāvā, eighteen miles to the south of Sādhorā, and twenty-two miles to the south-west of Khizrābād. The pillar is standing to the present day on the roof of the three-storied citadel (koṭla) of Firōz Shāh outside the 'Delhi Gate' to the south-east of modern Delhi. An elevation of the building, with the pillar on the top of it, was published in 1788 in the first volume of the Asiatic Researches, p. 379, and a sketch of it in 1803 in vol. 7, p. 175, plate 4.

The Delhi-Toprā. pillar bears seven edicts of Aśoka, of which the last and longest is unique, while other specimens of the first six edicts have been discovered elsewhere. The first six edicts and the eleven first lines of the seventh edict are arranged in four columns on the north, west, south, and east faces of the pillar; the eleven remaining lines of the seventh edict run all round the pillar.

Besides the Aśoka edicts and several minor records of pilgrims and travellers, the pillar bears three short inscriptions of the Chāhamāna Vīsaladeva of Śākambarī, son of Ānnalladeva (EI, 9. 67, n. 5), dated A. D. 1164, which have been edited last by Kielhorn from Fleet's impressions (IA, 19. 215 ff.).

The Delhi-Toprā pillar-inscription is the first record of Aśoka that was read and translated in 1837 by Prinsep (JASB, 6. 566 ff.). Facsimiles of this inscription had been in the possession of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 'since its very foundation, without any successful attempt having been made to decipher them' (id., p. 566).

'On searching the Society's portfolio' Prinsep 'found the five original manuscript plates of Captain Hoare, whence the engravings published in the Researches seem to have been copied.'

'I found also two much larger drawings of the first and last inscription of the series, apparently of the actual dimensions.—These I suppose to have been the originals presented to Sir William Jones by Colonel Polier, and therefore of themselves venerable for their antiquity!' (id., p. 567).

The ingenious manner in which Prinsep succeeded in deciphering the ancient Brāhmī alphabet deserves to be recorded here in his own words:

'In laying open a discovery of this nature, some little explanation is generally expected of the means by which it has been attained. Like most other inventions, when once found it appears extremely simple; and, as in most others, accident, rather than study, has had the merit of solving the enigma which has so long baffled the learned.'

'While arranging and lithographing the numerous scraps of facsimiles for Plate XXVII, I was struck at their all terminating with the same two letters, dānaṃ. Coupling this circumstance with their extreme brevity and insulated position, which proved that they could not be fragments of a continuous text, it immediately occurred [to me] that they must record either obituary notices, or more probably the offerings and presents of votaries, as is shown to be the present custom in the Buddhist temples of Ava; where numerous dhvajas or flag-staffs, images, and small chaityas are crowded within the enclosure, surrounding the chief cupola, each bearing the name of the donor. The next point noted was the frequent occurrence of the letter sa, already set down incontestably as s, before the final word:—now this I had learnt from the Saurāshṭra coins, deciphered only a day or two before, to be one sign of the genitive case singular, being the ssa of the Pali, or sya of the Sanskrit. "Of so and so the gift", must then be the form of each brief sentence; and the vowel ā and Anusvāra led to the speedy recognition of the word dānaṃ (gift), teaching me the very two letters, d and n, most different from known forms, and which had foiled me most in my former attempts. Since 1834 also my acquaintance with ancient alphabets had become so familiar that most of the remaining letters in the present examples could be named at once on re-inspection. In the course of a few minutes I thus became possessed of the whole alphabet, which I tested by applying it to the inscription on the Delhi column' (id., p. 460 f.).

The first four edicts were examined by Burnouf in his Lotus, and the fourth and sixth by Kern in his Jaartelling. Senart's edition and translation of the Delhi-Toprā pillar-edicts in his Inscriptions de Piyadasi (2. 1 ff.) were based on Cunningham's eye-copies. In 1884 Fleet issued excellent photo-lithographs, to which Bühler added transcripts in the Nāgarī character (IA, 13. 306 ff.), and which were utilized in Sir George Grierson's English translation of Senart's French article (IA, vols. 17 and 18). Finally Bühler edited and translated the seven pillar-edicts twice, in German (ZDMG, vols. 45 and 46) and in English (EI, 2. 245 ff.)."