Zitierweise / cite as:

Rageth, Nina: Zum Beispiel: Tempelinschriften in Tiruvaṇṇāmalai (திருவண்ணாமலை). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 3. Inschriften ; 7). -- Fassung vom 2008-07-17. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen037.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2008-07-17

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Referat in Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright:  Dieser Werk ist unter einer Creative Commons-Lizenz lizenziert

(Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, Weitergabe zu gleichen Bedingungen),

für zitierte Bilder und Texte gelten die dort genannten bzw. aus dem

Urheberrecht folgenden Bestimmungen.

Dieser Werk ist unter einer Creative Commons-Lizenz lizenziert

(Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, Weitergabe zu gleichen Bedingungen),

für zitierte Bilder und Texte gelten die dort genannten bzw. aus dem

Urheberrecht folgenden Bestimmungen.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

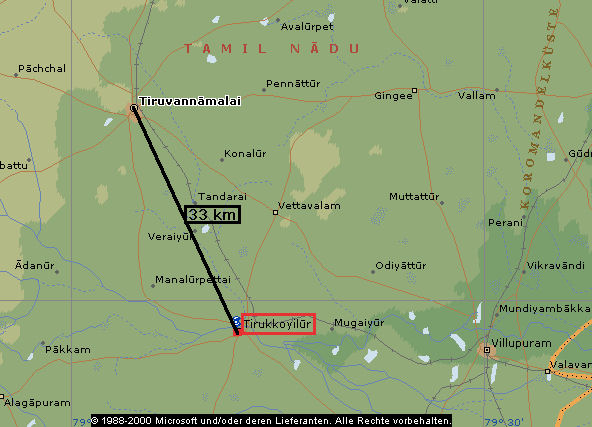

Abb.: Lage von Tiruvaṇṇāmalai (திருவண்ணாமலை)

(©MS Encarta)

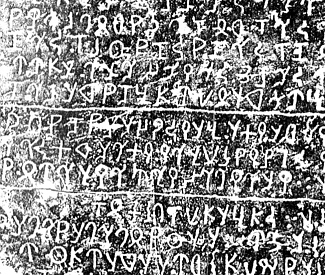

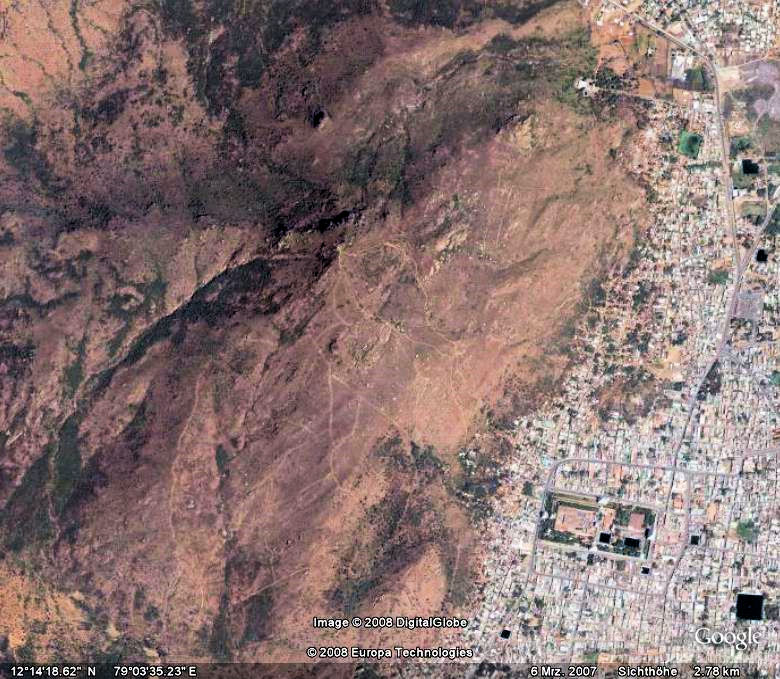

Tiruvaṇṇāmalai (திருவண்ணாமலை) liegt in Tamil Nadu (தமிழ் நாடு tamiḻ nāṭu), östlich von Pondicherry (Puducherry / புதுவை / புதுச்சேர), an den Ausläufern der Ostghats; nördlich des Flusses Ponnaiyār und zwar an einem früher sehr wichtigen Verkehrsknotenpunkt. In Tiruvaṇṇāmalai kreuzten sich zwei Hauptverkehrsachsen, welche den Norden mit dem Süden und den Osten mit dem Westen, dem Mysore Plateau, verbunden hatten. So war Tiruvaṇṇāmalai schon früh ein wichtiger Handels- und Kommunikationsknotenpunkt und auch ein strategisch günstiger Ort für politische und militärische Angelegenheiten. Die geographische Lage Tiruvaṇṇāmalais war entscheidend für seine weltliche, säkulare Wichtigkeit, für seine florierende Wirtschaft und die lange Beständigkeit der Stadt. Dank diesen Gegebenheiten konnte sich in dieser relativ unfruchtbaren Gegend, ein gut funktionierender und wohlhabender Tempelkomplex etablieren.

Abb.: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai (திருவண்ணாமலை)

US Army Map India and Pakistan 1 : 250.000 Blatt ND 44-14 (Conjeeveram). --

http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/ams/india/nd-44-14.jpg. -- Zugriff am

2008-07-16. -- Public domain

Abb.: Maßstab in km

Der Imperial Gazetteer of India enthält 1908 folgenden Eintrag zu Tiruvaṇṇāmalai:

"Tiruvaṇṇāmalai Tāluk.— North-western tāluk of South Arcot District, Madras, lying between 11° 58' and 12° 35' N. and 78° 38' and 79° 17' E. In the west a spur of the Javādi Hills of North Arcot, locally known as the Tenmalais ('south hills'), runs down into it ; and in the south it includes the corner of the Kalrāyan Hills round about Chekkadi, which is sometimes called the Chekkadi hills. Both these ranges are malarious. They are inhabited by Malaiyālis, a body of Tamils who at some remote period settled upon them and now differ considerably from their fellows in the plains in their ways and customs. On them are large blocks of 'reserved' forest in which grow sandal-wood, teak, and a few other timber trees, forming the most important of the Reserves in the District. Tiruvaṇṇāmalai is [S. 401] the largest tāluk in South Arcot, its area being 1,009 square miles, and its population, which numbered 244,085 in 1901, compared with 205,403 in 1891, increased during that decade by 18.8 per cent., showing a higher rate of growth than any other. It is still, however, the most sparsely peopled in the District, the density being only 242 persons per square mile, compared with the District average of 450. It contains 400 villages and one town, the municipality of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai (population, 17,069), the head-quarters. The rainfall is the lightest in South Arcot, being 36 inches annually, compared with the District average of 43 inches ; and the tāluk is more liable to scarcity than its neighbours. The demand for land revenue and cesses in 1903-4 amounted to Rs. 4,32,000. Tiruvaṇṇāmalai Town.—Head-quarters of the tāluk of the same name in South Arcot District, Madras, situated in 12° 14' N. and 79° 4' E., with a station on the Villupuram-Dharmavaram branch of the South Indian Railway. The population in 1901 was 17,069, of whom 14,981 were Hindus, 1,932 Musalmans, and the rest Christians. Roads diverge in four directions, and it is an entrepot of trade between South Arcot and the country to the west. The name means 'holy fire hill,' and is derived from the isolated peak at the back of the town, 2,668 feet above the sea, which is a conspicuous object for many miles around. The story runs that Śiva and Pārvatī his wife were walking one evening in the flower garden of Kailāśa, when Pārvatī playfully put her hands over Śiva's eyes. Instantly the whole world became darkened and the sun and moon ceased to give light ; and though to Śiva and his wife it seemed only a moment, yet to the unfortunate dwellers in the world the period of darkness lasted for years. They petitioned Śiva for relief, and to punish Pārvatī for her thoughtlessness he ordered her to do penance at various holy places. Tiruvaṇṇāmalai was one of these, and when she had performed her penance here Śiva appeared as a flame of fire at the top of the hill as a sign that she was forgiven. A large and beautifully sculptured temple stands at the foot of the hill, and at a festival in the month of Kārtigai (November-December) the priests light a huge beacon at the top of the hill in memory of the story. This festival is one of the chief cattle fairs in the District. The hill and the temple, commanding the Chengam pass into Salem, played an important part in the Wars of the Carnatic. Between. 1753 and 1790 they were subject to repeated attacks and captures. From 1760 the place was a British post, and Colonel Smith fell back upon it in 1767 as he retired through the Chengam pass before Haidar Alī and the Nizām. Here he held out till reinforced, when he signally defeated the allies. In 1790, after being repulsed from Tyāga Durgam, Tipū attacked the town and captured it. Tiruvaṇṇāmalai was constituted a municipality in 1896. [S. 402] The receipts and expenditure up to 1902-3 averaged Rs. 18,800 and Rs. 18,500 respectively. In 1903-4 the income, most of which was derived from tolls and the house and land taxes, was Rs. 20,800 ; and the expenditure was Rs. 19,100. The municipal area covers 11 square miles. One of the chief reasons for bringing it under sanitary control was that cholera used frequently to break out at the annual festival and be carried by the fleeing pilgrims far and wide through the District. The great want of the place is a proper water-supply, and experiments are in course of initiation."

[Quelle: The Imperial gazetteer of India / published under the authority of His Majesty’s Secretary of State for India in Council. -- New ed. -- Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1907-1909. -- 25 Bde. ; 22 cm. -- Bd. 23. -- 1908. -- S. 400 - 402. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/imperialgazettee23greauoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14]

Abb.:

Tiruvaṇṇāmalai (திருவண்ணாமலை)

und Aruṇācala

[©Google Earth. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14]

Abb.: Aruṇācala

[Bildquelle: imminent. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/imminent/292145263/. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-11.

--

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Neben der politisch und ökonomisch strategisch günstigen Lage, hatte der Ort auch eine spirituelle Anziehungskraft. Diese Anziehungskraft ist dem Aruṇācala Hügel zuzuschreiben, ein 800 Meter hoher Berg mit einem Umfang von 13 Kilometern. Es scheint, als ob sich eine Gemeinschaft um einen Berg angesiedelt hatte, von dem eine gewisse spirituelle Anziehungskraft ausgestrahlt wurde.

Die frühesten Belege, dass sich Dichter und andere spirituelle Leute in der Gegend um Tiruvaṇṇāmalai niedergelassen hatten, finden wir in der „Tamil Caṅkam (Sangam / தமிழ்) Literatur“ zwischen 100 vor und 200 nach Christus. Die frühesten Hymnen und Gedichte, die sich spezifisch auf den Ort Tiruvaṇṇāmalai, oder eher auf den Aruṇācala beziehen, stammen aber erst aus dem 7. Jh. n. Chr.

Die alten indischen Dichter wurden zu unzähligen Hymnen und Mythen inspiriert, in welchen sie eine Verbindung mit dem Berg- Feuer und Śiva; oder mit dem Berg und Śiva in seiner Feuersymbolik herstellten; so dass sich der Berg allmählich zu einem Śivaitischen Heiligtum entwickelte.

So erzählt zum Beispiel die Tradition, dass Śiva als kosmische Feuersäule, Brahmā und Viṣṇu auf dem Berg erschienen. Jeder von ihnen hielt sich selber für den Höchsten und Größten. Sie machten nun aus, dass derjenige der Śivas „Anfang oder Ende“ sehen konnte, gewonnen hatte. Doch Śiva, war so groß, dass sein Anfang und Ende nicht gesehen werden konnte. Viṣṇu in Gestalt eines Ebers und Brahmā in Gestalt eines Schwanes suchten erfolglos nach Anfang und Ende Śivas. So besiegte Śiva auf dem Aruṇācala die anderen beiden Gottheiten. Dieses Ereignis wird in vielen Śiva-Tempeln dargestellt; Śiva in der Feuersymbolik (lingodbhavamūrti) und an dessen Seiten Brahmā und Viṣṇu, welche ihn anbeten.

Tiruvaṇṇāmalai wird in vielen Sanskrit Texten für seine Heiligkeit und Schönheit gepriesen (Aruṇācalamāhātmya). Diese Texte wurden teilweise in berühmte Purāṇas aufgenommen, steigerten so die Popularität des Ortes und zogen viele Heilige und Studierte an, so dass sich allmählich ein Śivaitisches Zentrum um den Aruṇācala etablierte.

Abb.:

Aruṇācala

[Bildquelle: Jaggys. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jaggy/237779313/. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Aruṇācala

(©Google Earth. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-17)

Siehe auch:

Ramana's Arunachala : ocean of grace divine / by Sri Bhagavan's Devotees. Published by V. S. Ramanan. -- Tiruvannamali : Sri Ramanasramam, 2004. -- 402 S. -- Online: www.arunachala.org/downloads/books/ramanas-a-oogd.pdf. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14

Abb.: Wachstum des

Annamalaiyar Tempel (திருஅண்ணாமலையார் திருக்கோயில்):

vor 1030, um 1100, 1200, 1400, 1600 A.D.

[©Google Earth. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14]

Mit der Etablierung des Śivaitischen Zentrums um den Aruṇācala wurde auch mit dem Tempelbau in Tiruvaṇṇāmalai begonnen. Der älteste Teil des Tempels ist der innerste Schrein, das innerste Heiligtum. Diese erste Bauepoche fällt in die Cola-Periode. Dies wird durch Inschriften am Fundament des Schreines bestätigt, welche von ende des 9. anfangs 10. Jahrhundert stammen und somit die ältesten Inschriften des gesamten Tempelkomplexes überhaupt sind. Einige dieser Inschriften stehen auf dem Kopf, was darauf hinweist, dass dieser Schrein im Laufe der Zeit mindestens einmal verändert, oder erneuert wurde. Architektonische Studien weisen darauf hin, dass im 16. Jh. der innerste Schrein erneuert wurde.

Ein großer Teil der zweite Anlage wurde zwischen 1030 und 1040 gebaut, auch dies wird durch zahlreiche Inschriften bezeugt. Beendet wurde sie ende 12. Jh. Zur gleichen Zeit hat auch der Bau der dritten Anlage statt gefunden.

Die vierte und fünfte Anlagen wurden unter dem Hoysala (ಹೊಯ್ಸಳ) König Ballala III (ವೀರ ಬಲ್ಲಾಳ) geplant (1291-1342), wobei die fünfte Anlage, welche die bisherige Tempelgröße verdoppelte!, erst um 1570 beendet wurde. Dies war auch die Zeit als der innerste Schrein neu konstruiert wurde.

Der Tempel hat eine sehr lange Entstehungsgeschichte (von Ende 9. Jh. bis 1570), in welcher der Charakter des Tempels immer wieder stark verändert wurde. So war am Anfang der innerste Schrein das bedeutendste Element des Tempels. Die neu dazu gebauten Anlagen wurden dann aber kontinuierlich größer und dominanter zu ihren Vorbauten und die ganze Anlage wurde immer komplexer. Eine theologische Interpretation von dieser Architektur ist, dass der Tempel als das Zentrum der Welt gesehen wird, von dem die göttliche Energie ausgeht. Sie breitet sich in alle vier Himmelsrichtungen aus und während sie die systematisch immer größer werdenden Anlagen durchschreitet, wird sie immer intensiver.

Die immensen Bauten können aber auch als Ausdruck größenwahnsinniger Herrscher betrachtet werden, welche so ihrer Macht Ausdruck verleihen wollten und etwas Bleibendes, etwas, das ewig an sie erinnert, konstruieren wollten.

Abb.: Annamalaiyar Tempel (திருஅண்ணாமலையார் திருக்கோயில்)

[Bildquelle: James Gagen. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/fizzlefish/127423499/. -- Zugriff am

2008-07-14. --

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Annamalaiyar Tempel (திருஅண்ணாமலையார் திருக்கோயில்)

[©Google Earth. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14]

Der Tempel heute ist 465 m lang und 225 m breit. Seine heutige Größe ist das Tausendfache des ursprünglichen Tempels.

Heute hat der Tempel seine säkulare Bedeutung verloren. Ökonomische und politische Entwicklungen werden von der Stadt selber geleitet. Auch bestehen kaum mehr Verbindungen und Verträge zwischen dem Tempel und seiner Umgebung. Aber seine religiöse Bedeutung und spirituelle Anziehungskraft hat Tiruvaṇṇāmalai nicht eingebüsst. Zu den jährlichen Festen und Ritualen reisen immer noch tausende von Pilgern nach Tiruvaṇṇāmalai. Der Tempel ist als einer der wichtigsten heiligen Tempelanlagen in Tamil Nadu bekannt.

Abb.: Annamalaiyar Tempel (திருஅண்ணாமலையார் திருக்கோயில்) bei Vollmond

[Bildquelle: Jaggys. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jaggy/69317825/. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Karthikai Deepam (கார்த்திகை தீபம) in

Tiruvaṇṇāmalai

[Bildquelle: Jaggys. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jaggy/398365364/. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Zwischen 1980 und 1984 sammelten die Projektteilnehmer Inschriften im Tempels, in der Stadt und in den Dörfern der Umgebung. Es wurden insgesamt 360 Inschriften entdeckt und kopiert und auch einige wenige Kupferplatten gefunden.

Projektbeschreibung durch Marie-Louise Reiniche:

"TIRUVANNAMALAI A Śaiva sacred complex of South India

This is a collective programme of the Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient (Pondicherry) in which have been involved an Indian epigraphist (French Institute of Pondicherry), three members of the E.F.E.O. (covering geography, archaeology, architecture, iconography and related studies), an E.H.E.S.S. researcher (in ethnology) and a doctoral student in demography holding a scholarship for a period of study in India. In addition there was assistance from Indian associates (in Pondicherry) primarily in epigraphy (rubbings, card-indexing, etc.)

The project

These studies of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai originated with an historical enquiry : the antiquity of this sacred complex is attested by an epigraphical corpus which showed itself to be more significant than previously supposed when the epigraphist found that only a part of the inscriptions on the temple walls were recorded by the Epigraphy Department.

To undertake an overall survey of the temple and its surrounding area was the logical consequence of this first discovery. And since the object of this study was a sacred complex within a fully active town, a temple that had been constantly renovated over several centuries, it could not be limited to archaeology in the usual sense of the term. Other perspectives had to be considered which would take into account not only the past, but also a more sociological dimension as well as modern developments.

Field work

The rubbings, begun in 1980 but completed only in 1984, included rediscovered inscriptions from various places within the temple, the town and the surrounding villages, as well as several recently discovered copperplates. Archaeological and iconographical analyses and other investigations started gradually in 1981 and were carried out mainly between 1982 and 1984 ; several other complementary studies were undertaken in 1986. None of the participants were able to devote themselves to this research full-time over an extended period. Furthermore, the nature of certain of the studies (observation of festivals, the search for and collection of documents, and of information that was difficult to obtain) required that the research be extended over a longer period of time. Each participant, although having his own field of research, contributed assistance and information to the work of each of the others."

[Quelle: Marie-Louise Reiniche. -- In: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Bd. 1,1 und 1,2 mit dem Zusatz: a Saiva sacred complex of South India . -- Band 1. Inscriptions / introd., ed., trans.: P. R. [Pullur Ramasubrahmanya] Srinivasan ... -- Teil 1. -- Paris, 1990. -- 404 S. -- (Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie ; 75). -- Vor S. 1.]

Insgesamt erschienen fünf Publikationen im Zusammenhang mit diesem Projekt:

Abb.: Titelblatt Band I,1

Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris, 1990 - 1999. -- 5 Bde in 6. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Bd. 1,1 und 1,2 mit dem Zusatz: a Saiva sacred complex of South India . -- Bd. 1,1 und 1,2 in d. Reihe: Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie ; 75 erschienen.

Band 1 stellt alle gefundenen Inschriften von Tiruvaṇṇāmalai zusammen und liefert auch eine englische Übersetzung dazu.

Band 1. Inscriptions / introd., ed., trans.: P. R. [Pullur Ramasubrahmanya] Srinivasan ; indexes, topography: Marie-Louise Reiniche

- Teil 1. -- Paris, 1990. -- 404 S. -- (Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie ; 75)

- Teil 2. -- Paris, 1990. -- S. 405 - 771. -- (Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie ; 75)

"Inscriptions copied from the temple: The temple at the place which has been celebrated for its holiness through the centuries, was patronised by the rulers of almost all the royal families of Tamiḻnāṭu including the Hoysaḷas and the Vijayanagara kings. During their rule, the kings themselves had made a variety of donations to the temple. Besides, some private individuals too had contributed their mite for its upkeep and maintenance. Such transactions had invariably been put into writing and engraved on the various parts of the temple. In the course of the centuries the temple received additions, alternations and modifications. During these times, some inscribed slabs were broken of which some fragments were reused in the new constructions but some others were probably lost. Between A.D. 1806 and 18184, when Col. Colin Mackenzie was engaged in copying the inscriptions in the temples of the Madras Presidency, he had arranged for copying the epigraphs in the temple in question. Curiously, of about 500 items of epigraphs found here, his assistants had copied only ten (South Indian Temple Ins., I, Nos. 105-114, pp. 114-24). Of these, S.I.T.I., Nos. 105, 107, 109, 110, 111 have been subsequently copied and the rest are not traceable. Besides, one-line notices of nineteen items prepared by two assistants are also found in the Mackenzie Mss. (D. 2869 and 2760 of S.I.T.I., pp. 124-25). The Office of the Government Epigraphist visited the place in 1902 and copied 106 epigraphs which were reported in that year's Annual Report as Nos. B 469-574. Subsequently their texts alone were published in South Indian Inscriptions, Vol. VIII (Madras 1937), as Nos. 57 to 165 totalling to 109 because of the fact that A.R.E. [Annual Report on Epigraphy] Nos. 476, 488, and 539 were each split into two. That office visited the place again 1928-29 and copied ten more inscriptions which are reported as A.R.E., 1928-29, Nos. B 419-28. In 1945-46, they visited the place once more and copied sixteen new inscriptions and reported them in the A.R.I.E. [Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy], 1945-46, as Nos. B 66-81. Lastly they paid a visit to the place in 1952-53. In this trip they copied only two stone Inscriptions (A.R.I.E., Nos. B 212-13 of 1952-53) and four copper-plate epigraphs (ibid., A 8-11) which were In the custody of the Executive Officer of the temple there. The epigraphy office had been able to bring 134 inscriptions and four copper-plate records from 1902 to 1952-53 of this place to the notice of the scholars. In our comprehensive and sustained survey of the temple for inscriptions conducted intermittently from 1979 to 1984, we have been able to copy about 360 new inscriptions, many of them in their full form containing important pieces of information and the rest fragmentary. Besides, four new copper-plate inscriptions have also been copied in this survey. A list of all the inscriptions arranged in a chronological order is appended at the end. They range in date from the last decade of the 9th century to about A.D. 1800.

4 South Indian Temple Inscriptions, I, Tamil Intro, p. XX."

[Quelle: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Bd. 1,1 und 1,2 mit dem Zusatz: a Saiva sacred complex of South India . -- Band 1. Inscriptions / introd., ed., trans.: P. R. [Pullur Ramasubrahmanya] Srinivasan ... -- Teil 1. -- Paris, 1990. -- 404 S. -- (Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie ; 75). -- S. 5f.]

Im Band 2 wird der Tempel in seinen geographisch- historischen Kontext gestellt. Die Region mit dem Schwerpunkt auf den Berg und die Stadt wird beschreiben und die Bedeutung der geographischen Lage wird thematisiert. Des weiteren wird die Tempelarchitektur und Ikonographie untersucht und der Tempelbau dargestellt.

Band 2. L' archéologie du site / Françoise L'Hernault ; Pierre Pichard, Jean Deloche. -- Paris, 1990. -- 119 S. : Ill. -- (Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- ISBN 2-85539-763-4

Abstract des Inhalts von Band 2:

"English Summary Chapter 1

Tiruvaṇṇāmalai in its regional context

Jean Deloche

If we try to find out what fundamental urge might have made people settle at Tiruvaṇṇāmalai in large numbers, we note that it was not the poor soils of the gneissic pediplain on which it is situated that have fostered the development of the town, although, through refashioning by the hand of man, the water supply available has proved sufficient.

The urban community seems to have grown around a spot where the divine presence was felt at some date unknown to us, but probably much before it has been extolled by śivaite saints in the 7th century of our era. The shrine, dominated by the sacred mountain, has thus generated the town and the landscape bears the marks of this specific factor.

Yet, if the settlement has not remained a uniquely religious one, it is because, locally, it also occupies a position that is favourable to continuous urban development. Situated at the margin of hill and plain, it is a contact town, at the junction of two important arterial roads. Thus Tiruvaṇṇāmalai played a crucial role in military operations from at least the 15th century onwards up to the end of the Mysore wars.

Under the pax britannica, the town was to loose this strategic function and to confine itself to its religious role and its activities as a market centre.Chapter 2

The Mountain

Françoise L'Hernault

Tiruvaṇṇāmalai is above all its mountain, which symbolises the pillar of fire from which Śiva emerged. This myth has given rise to two iconographic representations. One of them is well-known: the liṅgodbhavamūrti - Śiva appearing within the pillar of fire, flanked by Brahmā and Viṣṇu in the attitude of worshippers. The other is a later development, specific to Tiruvaṇṇāmalai, where Śiva and Pārvatī are figured on a stele covered with semi-circular incisions to represent the mountain; the rear face of this stele is a liṅga, which is visible from the rear niche of the sanctuary. This representation is known locally as aḍi muḍi, the high and the low. after the same words in poems by Sambandar and Sundarar. referring to the directions in which Brahmā and Viṣṇu sought the extremities of the pillar of fire.

The mountain itself, a cone standing alone in the midst of the plain, appears on the boundary-slabs of lands dedicated to the Deity of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai, in the form of a triangle covered with semi-circular incisions, set either above the dynastic emblem of gaṇḍabhēruṇḍa the two-headed bird, or above the vase of plenty.

The mountain symbolically defines different spaces. It is the wild, uncultivated place (Tamil: kāḍu [காடு]) as opposed to the cultivated area. This contrast is marked in the festival of Tiruvūḍal, when Śiva has his jewels stolen on the mountain in the West, and finds them again in the East, in landowners' villages on the edge of the town, in the locality where, according to legend, the palace of King Ballala used to stand.

At first the opposition between the top and the bottom of the mountain seems to be absent, since there is not, as at certain sites, a temple at the bottom for the deity with his consort, and a temple at the top for the deity in his yogic aspect. At Tiruvaṇṇāmalai the single temple (at the bottom) is identified with the mountain, for which it is the substitute. The opposition is nevertheless marked four times a year by purification ceremonies (prāyaścitta) for which the priests go up to the summit of the mountain.

First, at the time of the Śivarātri festival, the appearance of the pillar of fire manifests the supremacy of Śiva. A few months later comes the marriage ceremony, the Union of Śiva with the Goddess. A few months later again, at the festival of Kārttigai, commemorating the appearance of the pillar of fire, there is still, union with the Goddess, as is shown by the procession of the hermaphrodite Śiva, Ardhanārīśvara. After Kārttigai, the fourth and last purification ceremony represents separation from the Goddess and the renewed manifestation of the supremacy of Śiva the great Yogi.

Finally, as a symbol of the centre, the mountain, like all mystic centres, emanates a space which is cardinalised in the same way as a maṇḍala. The route of 14 kms around the mountain and centred on its vertical axis, is oriented to the cardinal points by the distribution of shrines consecrated to the liṅgas of the directions.

A few Pandya milestones which remain along the route, inscribed with the division to which they belong, have made it possible to reconstruct the division of this circuit into nine stages, each corresponding to one unit of time/distance, the nāḻi (24 minutes), equivalent to 1.4/1.6 kilometres. Besides the shrines of the cardinal points, the pilgrimage route is punctuated by small shrines founded by devoted individuals or groups, hermitages, about sixty sacred ponds, wayside resting places for the deity during his two annual processions, by Nandis, and by footprints (pāda) of Śiva.

Chapter 3

The Aruṇācaleśvara Temple: description

Françoise L'Hernault and Pierre Pichard

After some ten centuries of construction and enlargement, the temple today forms a large rectangle. 465 m long and 225 m wide. Its longitudinal axis deviates from the East-West line by 13 degrees. If we assume that this deviation was intended to align with the rising sun on the day of its foundation, this would have been on either the 16th of February or the 24th of October.

As usual, in this book the successive enclosure walls have been identified and numbered from centre to periphery. But according to local tradition:

- the present-day Śiva shrine marks the centre of a former courtyard, covered at a later date and surrounded by an enclosure wall which would logically be the first one, but which is known locally as the second.

- what the temple priests and officers today call the first prākāra is the low platform of late construction around the central shrine. Properly speaking, there is thus no first enclosure wall; but this numbering system may refer to a former first enclosure. It is also confirmed by a 13th century inscription which mentions a building in the third prākāra - this inscription (214-230) is now located in the courtyard of the third enclosure.

- following this system, the present outer enclosure wall is the fifth one, which would tally with the tradition that there should be an uneven number of enclosures. Ideally, this number should total seven, which would be achieved by counting the rectangle of the car-streets as the sixth, and the pilgrimage circuit (around the hill) as the seventh.

According to this system, all the elements of the temple have been given a reference number, which appears on plate 3. They are described in order, first architecturally, then iconographically.

Chapter 4

The Aruṇācaleśvara Temple: building chronology

Françoise L'Hernault and Pierre Pichard

The central shrine is obviously the most ancient part of the temple. This is confirmed by the inscriptions on and around its base, which are the oldest in the temple (end of 9th and beginning of 10th centuries ad). These are however fragmentary ones, some on the shrine itself, some on the platform later built around it, and some even placed upside down. This clearly shows that the shrine is of ancient foundation, but has been completely reconstructed and altered; this is confirmed by the stylistic study of its architecture. The square hall adjacent to its eastern side can be dated to the 16th century, and most probably the renovation of the shrine was carried out at the same period.

The present second enclosure wall was built in two parts; the most ancient is the western portion, where there are numerous inscriptions from 1030-1040 ad. This portion may represent three sides of a first enclosure (fig. 39) built soon after the completion of the central shrine. A second, partial enclosure wall was then added on its eastern side (fig. 40), certainly before the end of the 12th century when the third enclosure was built. In its courtyard several structures were added during the 12th and 13th centuries (fig. 41), including a shrine for the goddess at the site of the present one, which was first rebuilt during the 16th century and then again at the end of the 19th.

With the fourth enclosure begins the plan with four gateways, one on each side. The north and south ones however, with their unusually small size and location on the eastern part of the walls (fig. 42), can only be explained by reference to the fifth enclosure, which doubled the area of the temple at one stroke by a large eastward extension. These two enclosures must thus have been designed together as one project under the reign of Ballala III (1291-1342 AD), who attached his name to the eastern gateway of the fourth enclosure; but the fifth enclosure could not be completed before the 16th century.This was a very active period for the temple (fig. 43). with this huge fifth enclosure and its great gateways being completed by 1570, and construction of the 1000-pillared hall and the pond in front of it, as well as the complete transformation and reconstruction of the central shrine and first enclosure, which was again to be greatly altered under the Nattukkottai Chettyars at the beginning of our century.

This long history has brought about a drastic reversal in the image of the temple, from a structure where the central shrine is the dominant element (cf. Tanjavur [தஞ்சாவூர்]), towards a more complex design dominated by the gateways, which are larger and higher as one progresses outwards. This reversal is not due to technical factors, as to build a high tower above four gates involves more work than building a single one above the sanctum.

The new model is more elaborate. From the temple as centre of the world, the divine energy pervades the space around it in the four cardinal directions, its growing intensity expressed by the systematically increasing height of each successive gateway - contrary to human perceptions and actions, which decrease with distance (sight, voice, power. . .).

Architecturally stressing the gateways instead of the sanctum implies that the approach may be more important than the arrival. It may be relevant to link this architectural reversal to the bhakti movement and its emphasis on personal devotion: the progress, the approach to the god is then reflected in the entranceways to the temple by gates and doors which are progressively reduced until the dark, central, inner sanctum is attained.

Chapter 5

The town's archaeological remains

Françoise L'Hernault

The town which today with its 100,000 inhabitants possesses about 150 temples, had at the end of the 19th century only 10,000 inhabitants, and therefore proportionately far fewer religious buildings. These were essentially shrines consecrated to Śiva, for we know that the temples to Gaṇapati, Subrahmaṇya and the Goddess are a recent phenomenon.

Although there was a Kālī, protectress of the locality, facing North, it seems that a Durgā temple, connected with a local myth, was particularly developed and that its deity came to be considered the protectress of the town, as is shown by the ceremonies at the start of the Kārttigai festival.

Because of the sacred baths which devotees came to take, and the rituals accompanying them, which involved large crowd-movements, the whole life of the area was intimately bound up with bodies of water: the Ayyaṅkuḷam at the heart of the town, and other tanks on its outskirts."

[Quelle: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Bd. 1,1 und 1,2 mit dem Zusatz: a Saiva sacred complex of South India . -- Band 2. L' archéologie du site / Françoise L'Hernault ; Pierre Pichard, Jean Deloche. -- Paris, 1990. -- 119 S. : Ill. -- (Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- ISBN 2-85539-763-4. -- Vor S. 1.]

Der dritte Band beschäftigt sich mit den Ritualen, Festen, Pilgerreisen und der Mythologie.

Band 3. Rites et fêtes / Françoise L'Hernault ; Marie-Louise Reiniche . Suppl. : Le Parārthanityapūjāvidhi / introd., trad. partielle et notes par Hélène Brunner. - Paris, 1999. - 340 S. -- (Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156,3). -- ISBN 2-85539-920-3

Aus der Présentation von Marie-Louise Reiniche:

"La parution du volume 3, consacré aux rites et fêtes, a été très retardée. L'observation du cycle annuel festif du Temple, ainsi que celle des fêtes de temples locaux pour leur éventuel intérêt dans l'ensemble rituel, s'est obligatoirement étalée sur plusieurs années (faute de pouvoir résider en permanence à Tiruvaṇṇāmalai). Ensuite, s'est posée la question du traitement de telles données. En ce qui concerne le rituel quotidien, aucune observation de l'extérieur n'est fiable - ce que l'on comprend vite en

lisant la traduction d'un texte sanskrit du rituel quotidien que Hélène Brunner a bien voulu donner en supplément à ce volume. Les fêtes spectaculaires se prêtent mieux à la description, mais la seule mise à plat des données est d'un intérêt limité. Nous avons tenté de suggérer au mieux ce que sous-tend la densité mythico-rituelle qui s'est construite sur des siècles. Les traductions, réalisées par Paul Albert, de quelques textes peu aisés en tamoul nous y ont aussi aidés. Enfin, le temps passant, chacun s'est laissé prendre dans d'autres projets ou tâches plus immédiates, plutôt que de s'enliser dans les ruses de la raison mythico-rituelle en espérant enfin saisir ses modalités dans la fabrique humaine et sociale d'une civilisation.En contrepartie, ce volume 3 est plus beau que les autres. Françoise Boudignon l'a mis en forme avec compétence et pour cause—ses dessins et son texte de Tiruvaṇṇāmalai, un pèlerinage en Inde du Sud en 1845 ont ravi les enfants, mais aussi rendus jaloux les chercheurs. Elle a organisé le présent volume avec le souci graphique et la sensibilité esthétique qui mettent en valeur un texte, un lieu, la réflexion des auteurs. Bien plus son travail est un hommage rendu à celle qui a été la cheville-ouvrière de l'ensemble monographique sur Tiruvaṇṇāmalai—Françoise L'Hernault, qui n'ouvrira pas ce livre où sont inscrits ses efforts, ses peines et ses enthousiasmes, son énergie à suivre l'information jusqu'au moment où le fil conducteur, qu'on croit tenir, craque. Ainsi en a-t-il été quant à sa vigilance de chercheur toujours en tension pour le bénéfice de la communauté scientifique.

août 1999 Marie-Louise Reiniche"

[Quelle: Marie-Louise Reiniche. -- In: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Band 3. Rites et fêtes / Françoise L'Hernault ; Marie-Louise Reiniche . Suppl. : Le Parārthanityapūjāvidhi / introd., trad. partielle et notes par Hélène Brunner. - Paris, 1999. - 340 S. -- (Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156,3). -- ISBN 2-85539-920-3. -- S. 8f.]

Der vierte Band ist eine soziologische Untersuchung über die Tempelorganisation und die ökonomische Funktion des Tempels.

Band 4. La configuration sociologique du temple hindou / Marie-Louise Reiniche. -- Paris, 1989. -- 242 S. : Ill. --(Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- ISBN 2-85539-756-1

Abstract von Marie-Louise Reiniche:

"English Summary Tiruvaṇṇāmalai, a Śaiva Sacred Place in South India

The Sociological Pattern of the Temple

The organization of one of the largest Śiva temples is studied, taking into account the temple epigraphy (Xth-XVIth c.) and the changes brought about by British colonization and the modern legal system. The supposedly economic function of the temple as well as the concept of redistribution are reconsidered in the light of a study of the divinity's possessions and of the temple accounts in recent years. The investigation covers mostly the ritual services, mainly priesthood, temple management and patronage as well as the deity's status. At different levels, the analysis tends to underline an ambiguity basically contradictory to the caste system hierarchy: whereas an asymmetrical relationship is ritually maintained between the priest and the sacrificer, at the same time the possibility is affirmed for a Hindu of any caste to attain salvation in a direct relationship with the divinity. Through devotion and with a renouncer-like self-control, man as an individual agent in the world is restored. From a sociological point of view, this is having several implications: the priests are regarded as inferior to the non-priestly Brahmins; power's image is relatively enhanced; sectarian movements have developed around spiritual masters. Moreover it turns out that Hinduism has contributed some of the basic elements towards the build-up of democracy, once the legal conditions for a modern State had been laid down. An introduction sets the temple under investigation within the variety of sacred places found at different levels of Hindu society."

[Quelle: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Band 4. La configuration sociologique du temple hindou / Marie-Louise Reiniche. -- Paris, 1989. -- 242 S. : Ill. --(Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- ISBN 2-85539-756-1. -- Vor S. 1.]

Band 5 beschäftigt sich mit der Stadt; mit demographischen Veränderungen und der Entwicklung von religiösen Institutionen.

Band 5. La ville / Christophe Guilmoto ; Marie-Louise Reiniche ; Pierre Pichard. -- Paris, 1990. -- 215 S. : Ill. -- (Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- ISBN 2-85539-762-6

Abstract:

"English Summary Compared with the other volumes of the collection, which focus on Tiruvaṇṇāmalai as a sacred place, the present one is the study of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai as an urban agglomeration. It is subdivided in two main parts, together with a third, shorter one which is not a conclusion but considers the question of defining what may be called a town in the Hindu past of South India.

The first part of the volume, written by C. Guilmoto, a demographer, concerns the modern city, a tāluk [தாலுகா tālukā] headquarters of North Arcot District, its recent development and its position within the urban network of Tamilnadu. Though Tiruvaṇṇāmalai remains a sacred place attracting thousands of Hindu pilgrims at the time of its Kārttikai [கார்த்திகை] festival, this alone cannot account for the tremendous growth of the town since the end of the XIXth century. Today the structures and components of the city are fully connected with and dependent on, the dynamics of urban growth that are at work all over Tamilnadu and India.C. Guilmoto's study is not a mere survey of a town. His broad aim is to understand the historical and geographical context behind the present development of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai. His contribution focuses on the characteristics of the town from various angles: regional geography, demographic history, urban social morphology and economic analysis. The convergence of these different, but interrelated perspectives serves to develop a general framework in which it becomes possible to distinguish regional trends from Tiruvannamalai's idiosyncratic features.

The first section is devoted to the description of Tiruvannamalai's regional setting in a semi-dry area from the major irrigation zones. The regional agrarian structure, with the transformations brought about by the introduction of groundnut as a new commercial crop, had a direct impact on the prosperity of the town - an impact later enhanced by the development of well irrigation and rice cultivation. This study of the geographical and historical setting in itself explains how Tiruvaṇṇāmalai came to be described as an oasis in a "urban desert".

The main part of this section (I.A. 2) is however concerned with the detailed examination of the town's demographic evolution in relation to other historical changes affecting both Tiruvaṇṇāmalai and its sub-region. Starting from the end of the XIXth century, regular census data help us to delineate the main cycles of the town's demographic growth. In order to do that, demographic statistics were analysed in a strict comparative way which allows to weigh carefully the respective importance of regional and urban factors (see Fig. 2 through 8). During a first period (1881-1931), Tiruvannamalai's growth was rapid, though erratic because of its vulnerability to the level of agricultural activities. In the 1960's Tiruvaṇṇāmalai emerged from a long period of relative stagnation to become one of the State's most successful agricultural towns. Technological changes in its rural hinterland brought direct and indirect prosperity, as well as large numbers of migrants, to the city.

The second section is a description of the town itself: first of its morphology (I.B), and secondly of its social areas (I.C). The town's structure derives firstly from the generic model of South Indian temple towns: a large central shrine with four converging streets and a perpendicular grid of streets around. The modern extension of the built-up areas along the regional axes of circulation gives to the town a star-shaped morphology, a feature reinforced by peripheral industrial development. The link between residence and occupation remains to some extent related to caste membership. However important sociological and economic changes might have been since the beginning of the town's growth, the temple and the old town's geometric structure still act as the guiding principle for the development of the urban space. This description of the urban morphology of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai is conforted by the point of view of an architect, P. Pichard, who analyses Tiruvaṇṇāmalai cadastral survey of 1927 (I.B. 3), and also points out the centrality of the temple, the density of the urban texture, and the characteristics of built plots very long in proportion and further reduced by family partition typical of traditional settlements of people of good status in Tamilnadu. As to the previous periods, the question remains open regarding the shifting and resettlement of the population surrounding the temple, as the temple premises were considerably extended several times along the centuries.

The morphological study is broadened by the analysis of the social composition of the town. It is worth recalling that the population of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai has increased tenfold within a hundred years, which implies a considerable mingling of people in relation to the migratory flows. To supplement the general information provided by the census, a rapid fieldwork inquiry was conducted at the street and house levels, which made it possible to ascertain the approximative number of houses and households as well as other data pertaining to the main occupations, social origins, and to a limited extent only, the regional origins of the population. Tiruvannamalai's present population is quite heterogenous, and none of the largest jāti [சாதி cāti] or castes living in the surrounding region is numerically dominant: though inhabitants of agrarian origin constitute a majority, they are further divided internally along social and regional, as well as political and economic lines. Based on the memories of elderly informants and results of his own enquiries, C. Guilmoto proposes two maps which can be compared to shed light on the development of social settlement in Tiruvaṇṇāmalai between circa 1910 and the 1980s. To a certain extent the social settlement remains segmented according to jāti and regional affiliations: particularly striking is the concentration of Muslims and that of Harijans, who remain clustered in settlements (cēri [சேரி], now called "colonies") once at the limits of the town and now surrounded by newly built areas. However, when the members of a jāti are scattered all over the municipal area, socio-economic factors tend to supersede the traditional settlement linked to caste identity. That also demonstrates the spatial articulation of social changes newly brought about by urban dynamics.

The analysis of the economic activities of the town (I.D) presents the basic data for assessing the economic role of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai, and its main actors. Whereas the industrial sector is limited to food-processing (rice and oil mills) and to a few mechanical industries producing diesel and electrical pumps for agriculture, the occupational structure shows clearly the importance of trade in the urban economy. The strength of the trading sector allows Tiruvaṇṇāmalai to play a crucial role in the economic relationships between the villages and within a large area of northern Tamilnadu, especially because the town is a regional centre for the processing and distribution of agricultural produces. C. Guilmoto's analysis of the complementary functions of the wholesale market (mandi [மண்டி maṇṭi]) and the regulated market emphasizes the centrality of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai for a large area - a role which has limited the possible commercial development of the small surrounding towns. For Tiruvaṇṇāmalai is also the place where large part of the local merchants' customers is provided by what is called the "floating population": the villagers of all the rural places round the city and the thousands of pilgrims thronging every year. With the help of its function as an interface between large rural areas and the urban economy, Tiruvaṇṇāmalai has been able to benefit directly from the growing economic exchanges: traditional trading castes (mostly Hindu but with a significant Muslim component) and fractions of the better-off local peasant castes were the first recipients of this prosperity.

The last part of this chapter (I.E) aims at stressing the global spatial factor behind Tiruvannamalai's changing fortunes. For this purpose, casting away the regional identity of the town would be misleading as its rural component has been part and parcel of its social and economic history. In the models based on the theory of central places, towns are simply considered redistributive centers for their hinterlands and then ranked according to the number of their central functions. However, this model is not very useful in the case of towns like Tiruvaṇṇāmalai whose growth is mainly the consequence of the transfer of agricultural surplus from the countryside to the town. The theoretical model presented here (based on gravity) aims at mapping various urban fields ("Umlands") surrounding the main towns of northern Tamilnadu. It assumes that a town's attraction is a direct function of its demographic size. The map thus obtained (Fig. 26) attempts to sum up the various geographical settings of each urban umland. Differences are clearly related to the general economic orientation of the towns. With its very large umland (several tāluks), Tiruvaṇṇāmalai as a classical type of agricultural market town stands apart from narrow urban regions relying on industrial activities. Its present upgrading to the level of a new district's headquarters is a testimony to its durable hegemony over large rural tracts of northern Tamilnadu.

After this study of the town of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai as it has evolved since the late XIXth century, involving many factors which have been analysed from different standpoints, the second part of the book again focusses on Tiruvaṇṇāmalai as a sacred place, but in this case the emphasis is on the geographical dimension of the sacred place through a study of the pilgrims.

Based on a survey carried out by C. Guilmoto at the time of the festival of Kārttikai in 1983, the first chapter (II. A-C) attempts to estimate the importance of this festival by locking into the composition of pilgrims it attracts. Before analysing the results of this survey, in a critical reading of the available literature C. Guilmoto gives an account of the main features and varieties of pilgrimages in India and in the Tamil tradition. There is no way to obtain a reliable estimate of the number of pilgrims attending religious festivals such as Kārttikai in Tiruvaṇṇāmalai. The great majority of pilgrims come from the North and South Arcot districts, and two thirds of them are villagers. Most of them belong to castes of peasant origins. Least numerous are pilgrims of Brahmin castes and Harijans. Regarding occupation, 54% of the surveyed pilgrims belonged to the non-agricultural sector, and among them, those who are engaged in trade or business are numerically important, as already observed in other sacred places in India. If we take into account the high proportion of literate or well educated pilgrims it appears that those coming from wealthy peasant classes and from urban middle castes (excluding Brahmins) constitute a significant substratum of Tiruvannamalai's pilgrims. All these informations help to locate the site of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai in the hierarchy of South Indian sacred places.

Another important feature of pilgrimage places are the pilgrims boarding-houses, "choultries" (cattiram [சத்திரம்]), called "madam" [மடம் maṭam] (sanskrit: matha, "monastery") at Tiruvaṇṇāmalai (III. A-D). 113 madam have been registered in the municipality, out of which more than the three quarters are still functioning institutions. Also included in this census are monasteries with a spiritual leader, hermitages (often founded around the tomb-samadhi of a guru), and a few charitable institutions but 75% of the total are simple choultries, each associated with a caste (Tabl. 25). These madam are mostly located (Fig. 30) along the procession routes of the temple divinity. Many of them were founded, or renovated, at the end of the XIXth century, as is the case of the wealthiest of them, built by the Nattukkottai Cettiyar of Ramnad, who at that time financed the renovation of the temple at Tiruvaṇṇāmalai - as they did in many other sacred places of Tamilnadu. Though the growth of the town has probably contributed to the increase in the number of madam, this kind of institution is quite old and historically attested. The madam vary in size and type of building: some are simply an open space for resting, many are houses of a usual type, a few are well built with a sanctuary (III. A; Fig. 31-35). A characteristic feature is the emphasis given to the dining area, and therefore to the giving of food. The madam is, in a way, a festive space related to the ceremonies of the temple.

As a boarding-house, every madam usually belongs to a group of people, members of one caste and in most cases of one of its subdivisions, who have inherited the right to occupy the madam as well as the duty to maintain it and to perform the religious charities (dharma) established by the founder. M.L. Reiniche's study analyses the diverse incomes of the madam (coming increasingly from various kinds of rents) and the religious purposes of the endowment (III. B & C). These issues raise several questions concerning the nature of such an institution, whose material form is a building which cannot be sold, and which consists of hereditary rights and duties as defined by the vow of the founder, and supposed to be everlasting.

There is also something of a paradox in the fact that in most cases the present right-owners of a choultry constitute one segment of a caste, although the madam was usually founded on an individual initiative. In the case of monasteries or hermitages, there is always at the origin of the institution one individual who has renounced the world and become a spiritual head for a community of disciples; even in that case, the present spiritual head may belong to a lineage of gurus (comparable to a descent line from father to son), while the disciples, even if socially mixed, keep some loose links through caste status and regional origin. The case of a choultry is comparable: at the origin there is an individual, a devotee of the presiding deity of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai. who came from elsewhere and decided to found a choultry in order to have a place to stay near the sacred

centre, and to perpetuate his devotion through an endowment. It is then possible to follow in theory the evolutive pattern of a madam: the choultry with the duties attached to the endowment is inherited by the founder's sons or very close relatives; it may then remain the very private concern of the founder's descendants, but it will more usually become the concern of the latter's locality-group. Then through relations of kinship and alliance the rights and duties connected with the madam are extended to the caste segment. As a further development, the madam may be taken under the control of the modern association of the caste (saṅgha [சங்கம் caṅkam]), and then virtually every member of the caste has a right on the madam. In the latter case however, the caste-members living in Tiruvaṇṇāmalai have the direct control over the madam; whereas in all other cases, the control remains in the hands of people living outside the sacred centre, which they visit at the time of the festival when they stay at the madam.The last section (III. D) is the comparative analysis of the different types of choultries in relation to caste, kinship and territorial settings of their members. On the basis of the information obtained from fieldwork, maps have been drawn (Fig. 37-44) representing the territorial areas associated to the Tiruvaṇṇāmalai choultries according to castes or caste-segments. From the global map (Fig. 44) it appears that the potential pilgrims having some rights on a madam located at Tiruvaṇṇāmalai originate from all over Tamilnadu; however, the attraction of the sacred place is primarily important for the area and the tāluks immediately surrounding Tiruvaṇṇāmalai, and then for the North Arcot district. These results are compared with those from C. Guilmoto's survey (II. B-C). Some other territorial distinctions are also pinpointed according to caste (castes of peasant origin versus traders' castes). It may be argued further that this analysis of choultries and the phenomenon of caste, which presents itself in diverse modes, makes evident that what is known as "caste" actually does not exist in itself (if not only as an abstract administrative category), but that it exists through the variable formations of small groupings. The geographical corollary is that each caste-segment, in its relation to the sacred place through a madam, is located in a discontinuous area, more or less delimited and shared by the territorial areas of other social groupings. The sum of these areas constitutes a potential network of relationships between Tiruvaṇṇāmalai place and an extended but discontinuous territory.

The third part of the volume is an attempt to understand how, and on what grounds, a locality may be characterised as "urban" in a given socio-historical context. Having analyzed the town of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai from various points of view and considered particularly its demographic and economic development, is it at all justified to consider Tiruvaṇṇāmalai a town in the past—that is, before the British administration made it the headquarters of a tāluk? More generally, how could we define a precolonial town in South India?

From the above analysis, we may deduce that the urban status of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai is demonstrated by the geographical extent of its attraction from the demographical and economic point of view as well as from the socio-religious one. Put it in another way, the geographical extent of various networks of relationships centered on a locality confers on it an urban dimension. If we now consider the topographical information provided by the temple inscriptions of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai from the Xth to the XVIth c. (from which maps have been drawn: see Fig. 45-50), and the large geographical extent of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai relationships at various periods of time, it seems logically possible to deduce that Tiruvaṇṇāmalai was already a town in the precolonial past. However the epigraphical information conveys only the point of view of the temple, and almost nothing can be directly inferred about the urban nature of the human settlement around it.

So in the next analysis are set forth, first, from a reading of the inscriptions, some clues relevant to the subject; and secondly, the potential role of a temple in conferring an urban dimension to its surroundings, as seems to have been the case for Tiruvaṇṇāmalai (always admitting that a temple alone does not make a town, if certain other conditions are not present).

Finally, a few hypotheses are stated in relation to the example of Tiruvaṇṇāmalai as one possible model of precolonial South Indian towns."[Quelle: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Band 5. La ville / Christophe Guilmoto ; Marie-Louise Reiniche ; Pierre Pichard. -- Paris, 1990. -- 215 S. : Ill. -- (Publications de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- ISBN 2-85539-762-6. -- Vor S. 1.]

Der von mir verwendete Band beginnt mit einer knappen Beschreibung der einzelnen Inschriften und zwar in einer chronologischen Reihenfolge. Das heißt, die erste beschriebene Inschrift aus dem Jahre 885 n. Chr. aus der Cola Periode ist auch die älteste Tempelinschrift.

Man kann diesen Teil des Werkes als einen historischen Abriss des Tempels betrachten, der anhand der Inschriften rekonstruiert wurde.

Dann folgt eine Zusammenstellung aller Orte, wo sich die Inschriften befinden. Die Orte wurden auch auf einer Karte eingezeichnet.

Nach einer knappen chronologischen Auflistung aller gefunden Inschriften, folgt dann der Hauptteil des Werkes, eine chronologisch geordnete Zusammenstellung aller gefunden Inschriften mit der jeweiligen englischen Übersetzung.

Zum Schluss folgen Indices, u.a. ein topographischer Index. Hier wurde versucht, alle Lokalitäten, die in den Inschriften genannt werden, ausfindig zu machen und zusammen zu stellen. Die Orte wurden auch in verschiedenen Karten eingezeichnet.

Während mehreren Jahrhunderten wurde der Tempel für seine Heiligkeit gepriesen, und er wurde auch von den meisten Herrschern der verschiedenen Königsfamilien von Tamil Nadu gefördert und unterstützt. Die Könige hatten während ihrer Herrschaftszeiten dem Tempel viele verschiedene Stiftungen gemacht. Dazu kamen private Spenden. Diese Transaktionen wurden meist niedergeschrieben und an verschiedenen Orten im Tempel eingraviert und verewigt. So sind die Tempelinschriften hauptsächlich Zeugnisse von Schenkungen und Gaben an den Tempel, an das Objekt der Verehrung und das religiöse und spirituelle Zentrum.

Ich möchte nun zwei konkrete Inschriften erläutern und habe hierfür aus den knapp 400 Inschriften zwei herausgesucht, die in einer gewissen Weise einen „verschiedenen Charakter“ haben.

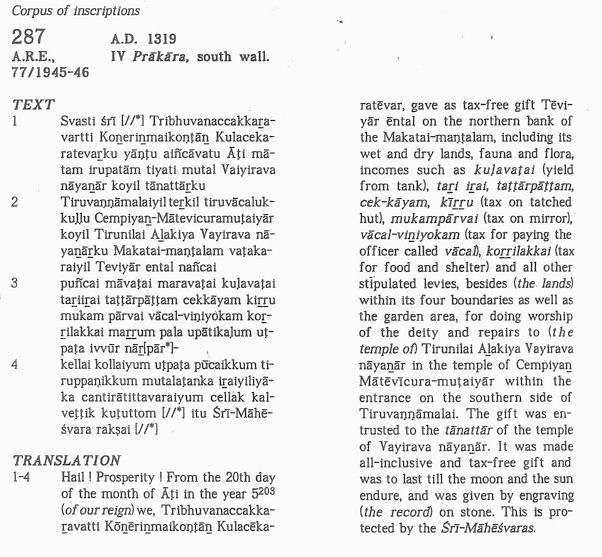

Das eine Beispiel (Nr. 86) ist eine typische Schenkungsinschrift. Bei der anderen Inschrift (Nr. 287) handelt es sich um eine, die die damalige „Steuersituation“ beschreibt.

Als Hilfsmittel für die Erläuterungen dienten vor allem

Sircar, D. C. (Dines Chandra) <1907 – 1983>: Indian epigraphical glossary / D. C. Sircar. - 1. ed.. - Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass, 1966. - XII, 560 S. -- ISBN 81-208-0562-3. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/indianepigraphic00sircuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14

Tamil lexicon : in six volumes / publ. under the authority of the University of Madras. -- Madras : Univ. of Madras, 1924 - 1939. -- 6 Bde + 1 Suppl. -- Online: http://dsal.uchicago.edu/dictionaries/tamil-lex/. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14

General Index. -- In: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Band 1. Inscriptions / introd., ed., trans.: P. R. [Pullur Ramasubrahmanya] Srinivasan ; indexes, topography: Marie-Louise Reiniche. -- Teil 2. -- Paris, 1990. -- S. 405 - 771. -- (Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie ; 75). -- S. 693 - 721.

Ausgabe:

Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Band 1. Inscriptions / introd., ed., trans.: P. R. [Pullur Ramasubrahmanya] Srinivasan ; indexes, topography: Marie-Louise Reiniche. -- Teil 1. -- Paris, 1990. -- 404 S. -- (Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie ; 75). -- S. 236 f.

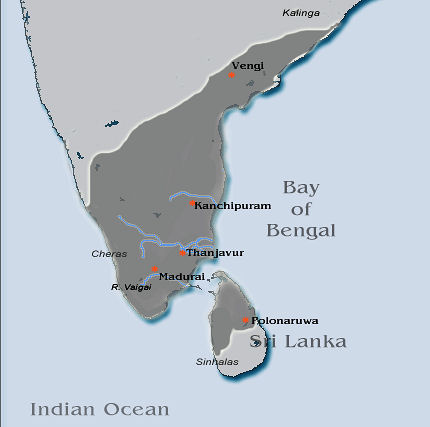

Dieses erste Beispiel stammt aus dem Jahre 1180 n. Chr. aus der Cola-Periode (சோழர் குலம்), aus welcher insgesamt 180 typische Schenkungsinschriften gefunden wurden. Diese Fülle an Schenkungen und Gaben mit denen der Tempel unterstützt wurde, zeigt, dass Tiruvaṇṇāmalai und der Śiva-Tempel viel Aufmerksamkeit von den Cola-Königen bekommen hatte und daher wohl eine wichtige Bedeutung für die Herrscher hatte.

Abb.: Das Cola-Reich und seine Einflussgebiete um ca. A.D. 1130

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Unter dem Cola-König Kulottuṅka III (குலோத்துங்க சோழன்) (1178- 1218) wurden 49 Inschriften gemacht, in denen viele verschiedene Schenkungen aufgezählt werden. Dies ist die größte Anzahl unter allen Cola-Monarchen. Diese Epoche wird die goldenen Epoche in der Geschichte des Tempels genannt. In ihr wurde auch die dritte Anlage des Tempels gebaut.

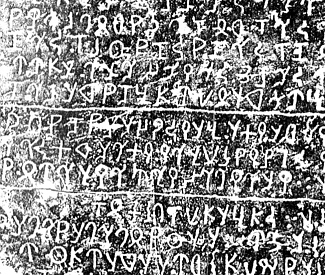

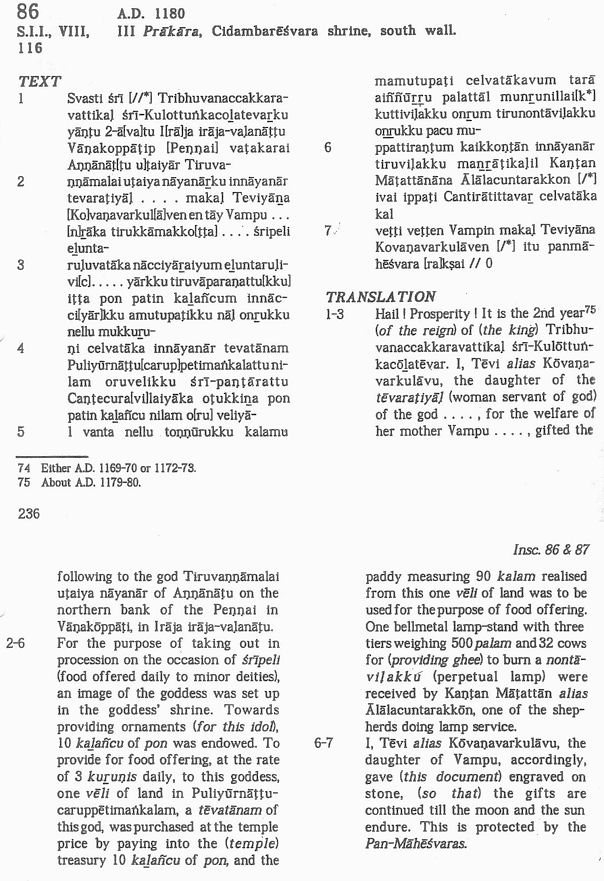

Faksimile der Ausgabe:

Abb.: Schenkungsinschrift (Nr. 86);

Prākāra

III, Cidambarēśvara

Schrein, south wall; 3r

Kopf der Ausgabe der Inschrift:

Nr. 86

S.I.I., VIII, 116a

A.D. 1180III Prākārab, Cidambarēśvara shrinec, south wall

Erläuterungen:

a S.I.I. = South Indian inscriptions. -- Madras : Printed by the Superintendent, Govt. Press. -- 1,1890ff.

b III Prākāra: 3. Ummauerung

c Cidambarēśvara shrine: Schrein des Herrn (īśvara) von Chidambaram (சிதம்பரம் / Citamparam), d.h. Śiva Naṭarāja (நடராசர்), Śiva, der den kosmischen Tanz tanzt.

Abb.: Prākāra III und Cidambarēśvara-Schrein im

Annamalaiyar Tempel (திருஅண்ணாமலையார் திருக்கோயில்)

[©Google Earth. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-14]

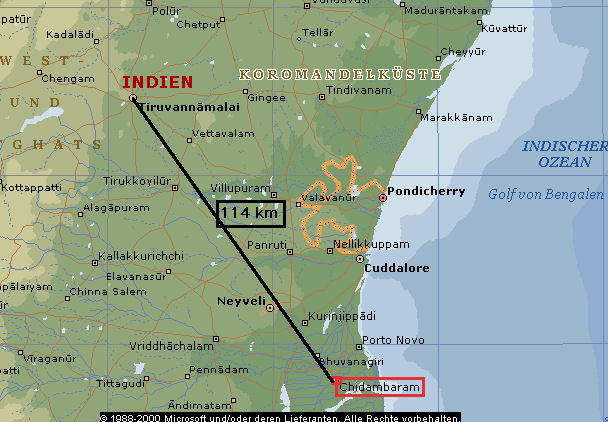

Abb.: Lage von Chidambaram (சிதம்பரம்)

(©MS Encarta)

"Chidambaram Town (Chit Ambalam, 'the atmosphere of wisdom').—Head-quarters of the tāluk of the same name in South Arcot District, Madras, situated in 11° 25' N. and 79° 42' E., on the South Indian Railway. The population in 1901 was 19,909, of whom 18,627 were Hindus and 1.191 Musalmāns. A municipality was constituted [S. 219] in 1873. The receipts and expenditure during the ten years ending 1902-3 averaged Rs. 24,800 and Rs. 25,100 respectively. In 1903-4 they were Rs. 25,800 and Rs. 27,600, the former consisting chiefly of the proceeds of the taxes on houses and land. An estimate for a water-supply amounting to Rs. 2,82,000 is now under consideration. During the Carnatic Wars Chidambaram was a place of considerable strategic importance. In 1749 the ill-fated expedition under Captain Cope against Devikottai halted here on its retreat to Fort St. David. In 1753 the French occupied it. In 1759 an attempt by the English failed, but it capitulated to Major Monson in 1760. Later on, Haidar Alī improved the defences and placed a garrison in the great temple. In 1781 Sir Eyre Coote attacked the temple, but was driven off.

Chidambaram is principally famous for its great Śiva temple. This covers an area of 39 acres in the heart of the town, and is surrounded on all four sides by streets about 60 feet wide. It contains one of the five great liṅgams, namely, the 'air liṅgam,' which is known also as the Chidambara Rahasyam or the ' secret of Chidambaram.' No liṅgam actually exists ; but a curtain is hung before a wall, and when visitors enter the curtain is withdrawn and the wall exhibited, the 'liṅgam of air' being, of course, invisible. The temple is held in the highest reverence throughout Southern India and Ceylon, and one of the annual festivals held in December and January is largely attended by pilgrims from all parts of India. As an architectural edifice it is a wonderful structure, for it stands in the middle of an alluvial plain between two rivers where there is no building stone within 40 miles ; and yet the outer walls are faced with dressed granite, the whole of the great area enclosed by the inner walls is paved with stone, the temple contains a hall which stands on more than 1,000 monolithic pillars, into the gateways are built blocks of stone 30 feet high and more than 3 feet square, and the reservoir, which is 150 feet long and 100 feet broad and very deep, has long flights of stone steps leading down to the water on all four sides. The labour expended in bringing all this and other material 40 miles through a country without roads and across the Vellār river must have been enormous.

The temple contains five Sabhas or halls, besides shrines to Vishṇu and Gaṇeśa. Its age and architecture are discussed at some length in Fergusson's History of Indian Architecture, which also contains several woodcuts of different parts of it. The Nāttukottai subdivision of the Chetti caste have recently been restoring the building at considerable cost. It possesses no landed endowments, and is managed in a most unusual way by the members of a sect of Brāhmans called Dīkshitars, who are peculiar to Chidambaram and depend entirely upon public offerings for their own maintenance and for the upkeep of the temple. The management may be described as a domestic hierarchy, each male [S. 220] married member of the sect possessing an equal share in its control. No accounts are kept. The Dīkshitars take it in turns to perform the daily worship. Except the temple, the place contains little of interest. There is a resthouse built by a Nāttukottai Chetti in which poor pilgrims are fed daily, and many other resthouses provide accommodation for travellers. A high school in the town is managed by the trustees of the well-known Pachayyappa charities."

[Quelle: The Imperial gazetteer of India / published under the authority of His Majesty’s Secretary of State for India in Council. -- New ed. -- Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1907-1909. -- 25 Bde. ; 22 cm. -- Bd. 10. -- 1908. -- S. 218 - 220. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/imperialgazettee10greauoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-07-15]

Text:

(1) Svasti śrī [//*] Tribhuvanacakkaravattikaḷ śrī-Kulottuṅkacoḻatevarku yāṇṭu 2-ā[va]tu I[rā]ja irāja-vaḷanāṭṭu Vāṇakoppātṭip [Peṇṇai] vaṭakarai Aṇnāṇaṭ[ṭu u]ṭaiyār Tiruva-

(2) ṇṇāmalai uṭaiya nāyanārku innāyanār tevararaṭiyāḷ .... makaḷ Teviyāḻa [Ko]vaṇarkul[ā]venentāy Vampu .... [n]rāka tirukkāmako[ṭṭa] .... śripeli elunta-

(3) ruḷuvatāka nācciyāraiyum eḻunta-ruḷivi[c] ... yārkkutiruvāparaṇattu[kku] iṭṭa pon pattin kaḻañcum innācci[yār]kku amutupaṭikku nāḷ onrukku nellu mukkuru-

(4) ṇi calvatāka innāyanār tevatānam Puliyuṛnāṭṭu[carup]petimaṅkalattu nilam oruvelikku śrī-paṇṭārattu Caṇṭecura[vi]laiyāka oṭukkiḻa pon patin kaḻañcu nilam o[ru] veliyā-

(5) l vanta nellu toṇṇūrukku kalamu mamutupaṭi celvatākavum tarā aiññūrru palattāl munrunillai[k*] kuttiviḷakku onrum tirunontāviḷakku oḻrukku pacu mu-

(6) ppatiraṇṭum kaikkoṇṭān innāyanār tiruviḷakku manrāṭikaḷil Kaṇṭan Māṭattānāna Ālālacuntarakkon [/*] ivai ippaṭi Cantirātittavar celvatāka kal

(7) veṭṭi veṭṭen Vampin makaḷ Teviyāna Kovaṇavarkulāven [/*] itu panmāhēśvara [ra]kṣai // 0

Englische Übersetzung:

(1-3) Hail! Prosperity! It is in the 2nd year1 (of the reign) of (the king) Tribhuvanacakkaravattikaḷ2 śrī-Kulōttuṅkacōḻatēvar3, I, Tēvi4 alias Kōvaṇarkulāvu5, the daughter of the tēvaraṭiyāḷ6 (woman servant of the god) of the god .... for the welfare of her mother Vampu7 .... , giftet the following to the god Tiruvaṇṇāmalai8 uṭaiya9 nāyanār10 of Aṇnāṇaṭṭu11 on the northern Bank of the Peṇṇai12 in Vāṇakōppātṭi13 in Irāja irāja-vaḷanāṭṭu14.(2-6) For the purpose of taking out in procession on the occasion of śrīpeli15 (food offered daily to minor deities), an image of the goddess15a was set up in the goddess' shrine. Towards providing ornaments (for this idol), 10 kaḻañcu16 of pon17 was endowed. To provide for food offering, at the rate of 3 kuṟuṇis18 daily, to this goddess, one vēli19 of Land in Puliyūrnāṭṭucaruppētimaṅkalam20, a tēvatānam21 of this god, was purchased at the temple price by paying into the (temple) treasury 10 kaḻañcu16 of pon17, and the paddy22 measuring 90 kalam23 realised from this one vēli19 of land was to be used for the purpose of food offering. One bellmetal24 lamp-stand with three tiers weighing 500 palam25 and 32 cows for (providing ghee26) to burn a nontāviḷakku27 (perpetual lamp) were received by Kaṇṭan Māṭattān28 alias Ālālacuntarakkōn29, one of the shepherds30 doing lamp service.

(6-7) I, Tēvi4, alias Kōvaṇavarkulāvu5, the daughter of Vampu7, accordingly, gave (this document) engraved on stone, (so that) the gifts are continued till the moon and the sun endure. This is protected by the Pan-Māhēśvaras31.

Erläuterungen

1 in the 2nd year2 Tribhuvanacakkaravattikaḷ « Sanskrit: Tribhuvanacakravartin: Ein Weltenherrscher (Cakravartin) über die drei Welten (Unterwelt, Welt, auf der wir leben, und Oberwelt) mit seiner universalen Herrschaft von Ozean bis Ozean setzt er das Rad (cakra) der Gerechtigkeit in Bewegung (vṛt -> vartin) und garantiert Frieden und Recht

3 śrī-Kulōttuṅkacōḻatēvar: "der herrliche (śrī) König (tēvar) Kulōttuṅka aus dem Coḷa-Geschlecht"

śrī (்ரீ) = Sanskrit śrī: ein Titel der Respekt ausdrückt

Kulōttuṅkacōḻa III. (குலோத்துங்க சோழன் III) (1178- 1218): Kulōttuṅka (Kulottuṅga), der Coḷa (Chola)

tēvar (தேவர்) « Sanskrit deva: Gott, König

Pullur Ramasubrahmanya Srinivasan, der Herausgeber der Inschriften schreibt zu Kulōttuṅkacōḻa III.:

"Kulōttuṅka III (circa A.D. 1178-1218) Inscriptions belonging to Kulōttuṅka III's time "are very numerous". This seems to get support from the fact that our collection of epigraphs from this single temple includes as many as forty-nine items attributable to the period of reign of Kulōttuṅka III, the successor of Rājādhirāja II. According to Prof. Sastri, "the former's relationship with the latter, if any, is not clear"36. The same author in another context categorically states that "it is quite impossible that Kulōttuṅka III was one of the children of Rājarāja, said to have been one and two years old at the time of his death ; for he came to the throne in A.D. 1178 within six years after Rājarāja's death, and took an active part in the war of Pāṇḍyan Succession which had begun while Rājarāja was still living. The evidence of Kulōttuṅgaṉ Kōvai and Śaṅkaracōḻaṉ ulā also points to the same conclusion"37. But while examining the "most important record" from Pallavarāyaṉ-pēṭṭai, the A.R.E, 1923-24, pp. 103-04, confidently says that the two children of 1 and 2 years of age were the children of Rājarāja II and "being an infant Kulōttuṅka III, the son of Rājarāja II did not succeed his father immediately". This was accepted in 1957 itself by T.V. Sadasiva Pandarattar who has also categorically stated that Kulōttuṅka III was the son of Rājarāja II38. He has also accepted and stated that Rājādhirāja II was the grandson of Vikrama-cōḻa39. That the date of accession of Rājādhirāja II may be A.D. 1166 has already been suggested as the probable one by Prof. Sastri40, although his ignoring of the other facts is difficult to understand. So, the recent re-study of the problem after an elaborate examination of the Pallavarāyaṉ-pēṭṭai [S. 16] epigraph is good in so far as it goes to confirm the earlier views and for stating that Rājādhirāja II was the son of Rājarāja II's sister named Neṟiyutaipperumā41.

36 K.A.N. Sastri, The Cōḻas (2nd edn. 1955), p. 372.

37 Ibid, p. 360, quoting Sen Tamiḻ, III, pp. 164 ff; contra A.R.E., 1909, II, 48 ; 1928, II, 21 ; E.I., XXI. p. 186.

38 See his Piṟkālac-Cōḻar Cartttiram, (in Tamil, Annamalai University, 1957), part II, pp. 145-146.

39 Ibid, pp. 123, 145. Also stated earlier by K.A.N. Sastri, The Cōḻas (2nd edn. 1955), p. 354.

40 K.A.N. Sastri, The Cōḻas (2nd edn. 1955), p. 359.

41 N. Sethuraman, The Cholas.... (1977), pp. 123 ff.

Kulōttuṅka III ruled for forty years and his records upto that year are known. But in our collection, records belonging to the regnal years 2 to 35 excepting those of the years 7 to 9, 12, 15, 16, 22, 23, 31 and 34 are available. One of the second year (87) commencing abruptly with the name of the king Vīrarācēntiracōḻatēvar which was attributed by others to Vīrarājendra of A.D. 1067 is included here for the reasons stated above (see p. 20). Another epigraph of the 11th year (94) is included here just because the title of Tripuvana-Vīracōḻatēvar of the king occurs in it, although the king is stated to have borne the title only from his 24th year42 and that the astronomical details preserved by this record were found by Kielhorn not to work out correctly for this reign43. Amongst the epigraphs under study only one genuine record (128) of the 35th year contains the title Tiripuvanavīratēvar. One epigraph (131) which does not preserve the date particulars but containing the name Vīrarācēntiracōḻatēvar coupled with the title Tiripuvanaccakkaravattikaḷ is included on the basis of the title44. Two inscriptions (132, 133) engraved one on each wall of the Kiḷi-gōpura, which are in Sanskrit and in the Grantha script of the 12th century find a place here in spite of the fact that they do not contain the name of the king or any other particulars relating to him on the assumption that Mantrīśvara Bhāskara who, according to the epigraphs, was responsible for the coming into existence of the gōpura (gōpur-ōdaya karaṇam) and was an important Mantri of Kulōttuṅka III. As shown below (see chapter on Buildings Works), the gōpura along with the enclosure wall and other adjuncts associated with it might have come into existence by the 2nd year of the king's reign because of the existence on its wall of the 2nd year record (87) already referred to.

42 K.A.N. Sastri, op.cit, p. 397.

43 E.I., VII, pp. 7-8.

44 K.A.N. Sastri, The Cōḻas, Vol. II (Madras, 1937), p. 717.

The meykkīrttis of the king are not seen in any of the inscriptions dealt with here. Neither do they contain descriptive titles mentioning about his campaigns and conquests of Karuvūr and Kāñcīpuram or about his performing anointments (vīra- or vijayābhiṣēka)45. However, in five records, three of the 27th year (114, 115, 118), one of the 28th year (120) and one in which the date is not preserved (129), the title Maturaiyum Īḻamum Pāṇṭiyaṉ muṭittalaiyuṅ koṇṭaruliya occurs. This means "who was pleased to take Maturai, Īḻam and the crowned head of the Pāṇṭiya". The occurence of this single title amongst his 49 inscriptions dealt with here gives room to infer that the king valued the achievements mentioned here as important and characteristic of his regime while the other ones were of an ephemeral nature46.

45 K.AN. Sastri, The Cōḻas (2nd edn. 1955), p. 377.

46 N. Sethuraman, The Cholas.... (1977), pp. 119 ff. T.V. Sadasiva Pandarattar, Piṟkālac-Cōḻar Cartttiram, Part II, pp. 151 ff."

[Quelle: Tiruvaṇṇāmalai : un lieu saint sivaïte du sud de l'Inde. - Paris. -- (Publications de l'Ecole Française d'Extrême-Orient ; 156). -- Bd. 1,1 und 1,2 mit dem Zusatz: a Saiva sacred complex of South India . -- Band 1. Inscriptions / introd., ed., trans.: P. R. [Pullur Ramasubrahmanya] Srinivasan ... -- Teil 1. -- Paris, 1990. -- 404 S. -- (Publications de l'Institut Français d'Indologie ; 75). -- S. 15f.]

4 Tēvi (தேவி) « Sanskrit devī: Göttin; Königin; Dame aus hohem Stand; hohe Frau

5 Kōvaṇarkulāvu

Kōvaṇa ist eine Bezeichnung für Śiva

6 tēvaraṭiyāḷ (woman servant of the god)

tēvar (தேவர்) « Sanskrit deva: Gott, König;

aṭiyāḷ: Dienerin, Ergebene

also: Gottesdienerin

7 Vampu (வம்பு)

8 -10 Tiruvaṇṇāmalai uṭaiya nāyanār: Herr von Tiruvaṇṇāmalai

8 Tiruvaṇṇāmalai

Tiru (திரு) « vermutlich Sanskrit śrī: als Vorsilbe betont die Größe;

aṇṇāmalai ist ein Synonym für Aruṇāchala und besteht aus

aṇṇaṉ (அண்ணன்): Gott, Śiva

malai (மலை): Hügel, Berg

9 uṭaiya adj. gehören zu, besitzen (bezeichnet den Genetiv)

10 nāyanār (நாயனார்): Herr, Herrscher, Gott

11 Aṇnāṇaṭṭu: Gottesland (?)

aṇṇaṉ (அண்ணன்): Gott, Śiva;

ṇaṭṭu eventuell = nātu (ஞாடு): Land, Erde, Gebiet

12 Peṇṇai

13 Vāṇakōppātṭi: im Tiruvaṇṇāmalai tāluk

14 Irāja irāja-vaḷanāṭṭu

irāja (இராசா irācā) « Sanskrit rājan (rāja): König, irāja-irāja = König der Könige

vālanāṭu: Distrikt