Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlassenschaften. -- 1. Zum Beispiel: Taxila (ٹیکسلا, तक्षशिला, Takkasilā). -- Fassung vom 2008-04-20. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen051.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2008-04-17

Überarbeitungen: 2008-04-20 [Ergänzungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

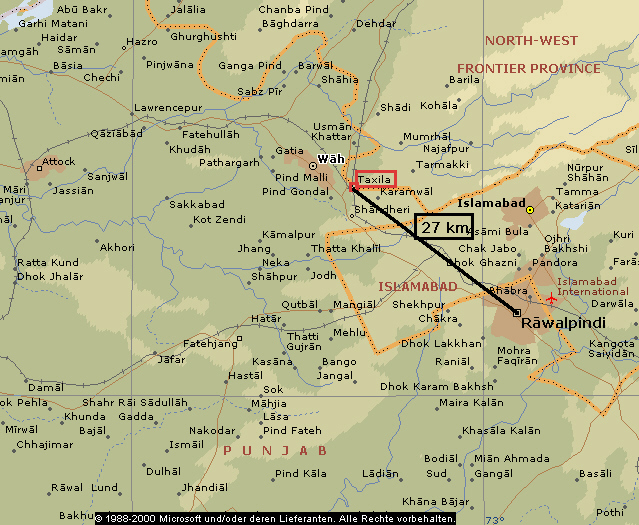

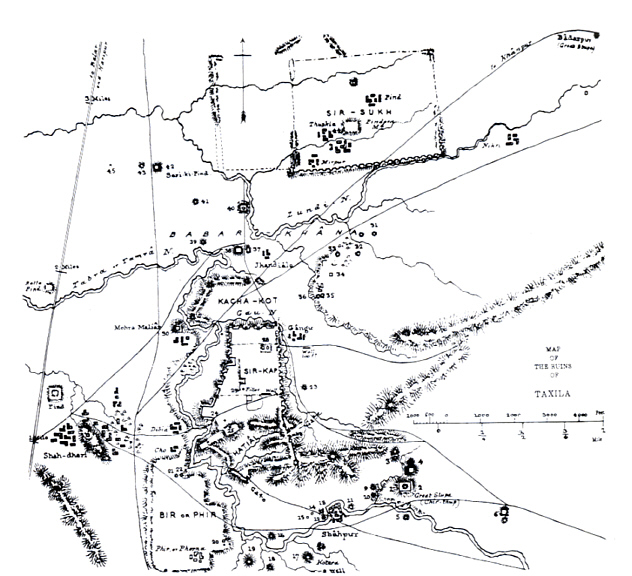

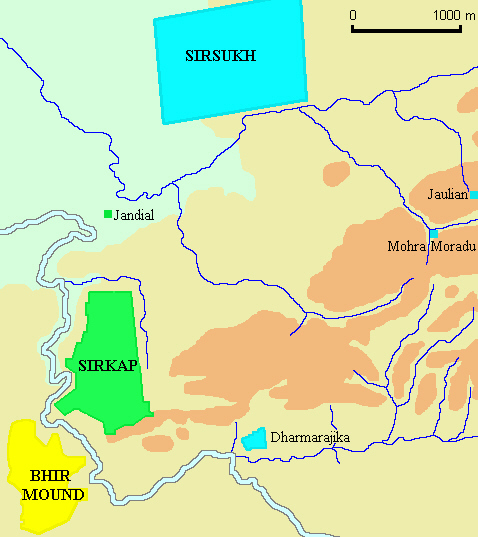

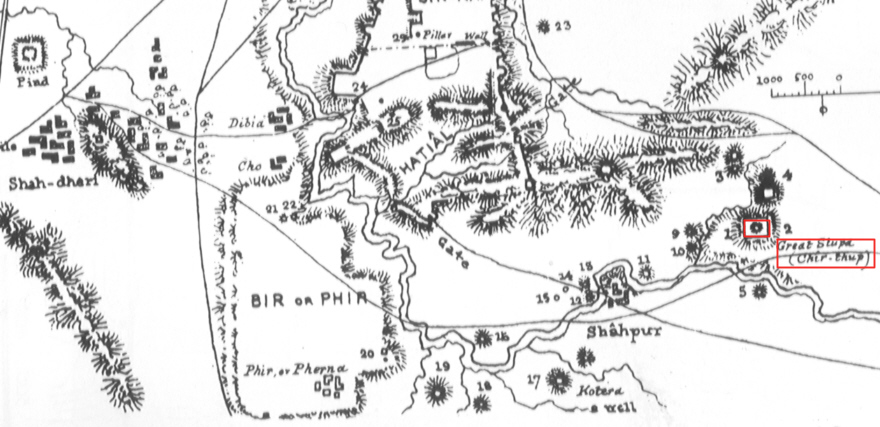

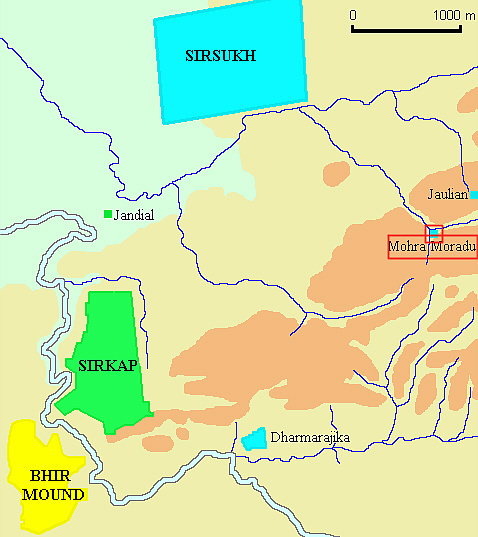

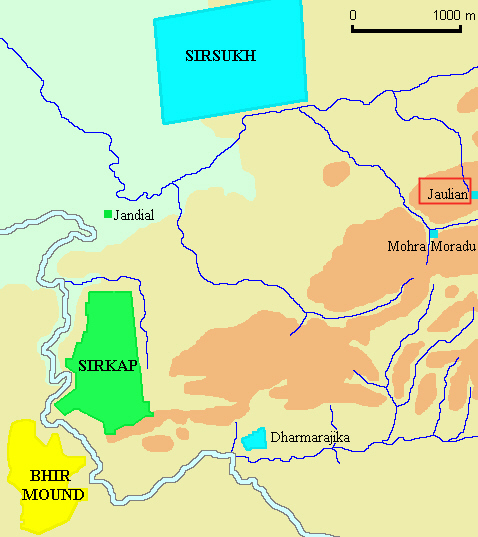

Taxila (ٹیکسلا, तक्षशिला, Takṣaśila, Takkasilā) liegt im Sind Sāgar Doāb ("Zweistromland") zwischen den Flüssen Jhelam (Jhelum) (دریاۓ جہلم, ਜੇਹਲਮ, झेलम) und Indus (Sindhu) (سندھ , ਸਿੰਧੂ, सिन्धु , حندو , ّآباسن , 印度 ,Ινδός) am Fuße der Murree (مری) Hills.

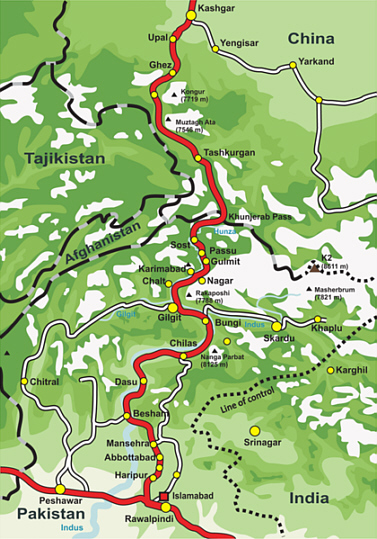

"Taxila (Urdu: ٹیکسلا, Sanskrit: तक्षशिला Takṣaśilā, Pali:Takkasilā) is an important archaeological site in Pakistan containing the ruins of the Gandhāran city of Takshashila (also Takkasila or Taxila) an important Vedic/Hindu and Buddhist centre of learning from the 6th century BCE to the 5th century CE. In 1980, Taxila was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site with multiple locations. Historically, Taxila lay at the crossroads of three major trade routes: the royal highway from Pāṭaliputra; the north-western route through Bactria, Kāpiśa, and Puṣkalāvatī (Peshawar); and the route from Kashmir and Central Asia, via Śrinagar, Mānsehrā, and the Haripur valley across the Khunjerab pass to the Silk Road.

Taxila is situated 35 km to the west of Islamabad Capital Territory—and to the northwest of Rawalpindi in Punjab—just off the Grand Trunk Road."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-17]

Abb.: Lage von Taxila

[©MS Encarta]

Panoramabilder: http://www.world-heritage-tour.org/asia/south-asia/pakistan/taxila/map.html. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-20. -- Sehenswert!

Abb.: Der Karakorum Highway nach Kashgar (Kaxgar; Uigurisch:

قەشقەر; 喀什)

folgt ungefähr der alten Handelsroute von Taxila nach Norden

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

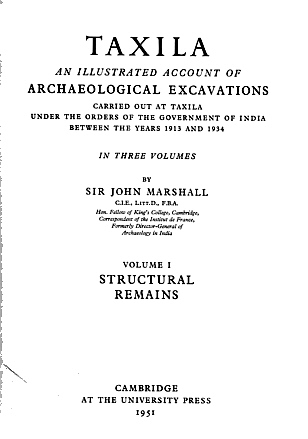

Hauptvorlage:

Marshall, John <1876 - 1958>: A guide to Taxila / by Sir John Marshall. - 4. ed.. - Karachi : Sani Communications, 1983. - V, 195 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Cambridge : University Press, for the Dept. of Archaeology in Pakistan, 1960. -- S. 40 - 46.

Viele Jahreszahlen sind nur Anhaltspunkte ohne gesicherte Grundlage!

538 - 530 v. Chr.

Kyros II. von Persien (کوروش, Kūruš, Kuraš, כורש, Cyrus) (590/580 - 530 v. Chr.) aus der Achämeniden-Dynastie erobert Baktrien (538), dann Gandhāra und dringt in den Panjāb bis zum Indus vor.

Abb.: Das Perserreich unter Kyros II.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

522 - 486 v. Chr.

Vermutliches Datum der ersten Stadt auf dem Bhiṛ Mound.

Die Perser führen Aramäisch (ܐܪܡܝܐ) als Amtssprache ein.

ca. 518 v. Chr.

Dareios I. (داریوش, Darayavahuš, Dariamuš, Dariyamauiš, Dryhwš, Ahasveros, Darius) (549 - 486 v. Chr.) gliedert Nordwestindien samt Taxila dem Perserreich ein.

Abb.: Das Perserrreich unter Dareios I. (um 500 v. Chr.)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

ca. 515 v. Chr.

Skylax von Karyanda (Σκύλαξ ο Καρυανδεύς) erforscht im Auftrag von Dareios I u.a. den Unterlauf des Indus

326 v. Chr.

Abb.: Alexander der Große als Zeus Ammon (Ζεύς Ἄμμων), zeitgenössische Kamee (um 325 v. Chr.)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Tatradrachme Alexanders des Großen. Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]Ambhi, König von Taxila, unterwirft sich Alexander dem Großen (Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μέγας) von Makedonien (356 - 323 v. Chr.). Alexander besiegt den indischen König Puru (Poros/Πόρος) in der Schlacht am Hydaspes = Jhelam (झेलम, دریاۓ جہلم, ਜੇਹਲਮ). Philipp (Φιλιππoς), Sohn des Machatas wird Satrap von Taxila.

Abb.: Alexanders Feldzüge im Osten

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

326 v. Chr.

Philipp (Φιλιππoς), Sohn des Machatas wird ermordet. An seine Stelle treten Eudemos (Eύδημoς) (gest. 316 v. Chr.) und Taxiles/Taxilas (Tαξίλης/Ταξίλας)

Abb.: Östliche Satrapen

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia, Public domain]

323 v. Chr.

Tod Alexanders des Großen (Ἀλέξανδρος ὁ Μέγας) von Makedonien (356 - 323 v. Chr.) in Babylon.

ca. 317 v. Chr.

Eudemos (Eύδημoς) (gest. 316 v. Chr.) zieht sich aus dem Nordwesten Indiens zurück. Candragupta Maurya (चन्द्रगुप्त मौर्य, Σανδρόκυπτος / Σανδρόκοττος) (ca. 340 - 298 v. Chr.) nimmt den Panjāb in Besitz.

312 v. Chr.

Beginn der Seleukidenära.

305 v. Chr.

Abb.: Münze von Seleukos I. Nikator (Σέλευκος Α’ Νικάτωρ)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]Seleukos I. Nikator (Σέλευκος Α’ Νικάτωρ) (358 - 281 v. Chr.) marschiert in Nordostindien ein, wird von Candragupta Maurya geschlagen und schließt mit diesem einen Friedensvertrag.

ca. 300 v. Chr.

Megasthenes (Μεγασθενής) wird Gesandter von Seleukos I. Nikator am Hof Candragupta Mauryas in Pāṭaliputra (heute Patna/पटना).

298 v. Chr.

Tod Candraguptas. Sein Nachfolger wird sein Sohn Bindusāra (बिन्दुसार). Bindusāras Sohn Aśoka wird Vizekönig in Taxila. Deimachus (Δηιμάχος) wird Gesandter von Seleukos I. Nikator am Hof Bindusāras in Pāṭaliputra (heute Patna/पटना).

ca. 268

Aśoka (अशोक) Maurya, der Sohn Bindusāras wird dessen Nachfolger.

ca. 250

Abb.: Goldmünze von Diodotos I. Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]Diodotos I. spaltet Baktrien vom Seleukidenreich ab und begründet das Griechisch-Baktrische Königreich. Arsakes I. (ارشک) spaltet das Partherreich vom Seleukidenreich ab.

Abb.: Partherreich und Griechisch-Baktrisches Reich um 250 v. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

ca. 233 v. Chr.

Tod Aśokas. Allmählicher Zerfall des Maurya-Reichs.

206 v. Chr.

Der Seleukidenkönig Antiochos III. der Große (242 - 187 v. Chr.) schließt mit Euthydemos I. von Baktrien (Ευθύδημος Α΄ της Βακτρίας) Frieden und marschiert im Tal von Kabul (کابل) ein, dort unterwirft sich ihm der Maurya-Gouverneur Subhāgasena (Sophagasenus)

ca. 189 v. Chr.

Abb.: Demetrios I. ANIKETOS ("Der Unbesiegbare), unter Agathocles geprägt. Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]Demetrios I. (Δημήτριος) wird in Nachfolge seines Vaters Euthydemos I. König von Baktrien und erobert Gandhāra, den Panjāb und das Industal. Er erbaut seine Hauptstadt in Taxila.

Die darauf folgenden Könige des Griechisch-Baktrischen bzw. Indo-Baktrischen Reiches sind (Angaben ohne Gewähr!):

Unterkönige in Gandhāra waren ab Menander:

- Antimachus II (Αντιμαχος

- Polyxenus (Πολύξενος)

- Epander (Επανδρος)

- Philoxenus Φιλοξενος

- Diomedes (Διομήδης)

- Artemidorus (Ἀρτεμίδωρος)

"List of the Indo-Greek kings and their territories Today 36 Indo-Greek kings are known. Several of them are also recorded in Western and Indian historical sources, but the majority are known through numismatic evidence only. The exact chronology and sequencing of their rule is still a matter of scholarly inquiry, with adjustments regular being made with new analysis and coin finds (overstrikes of one king over another's coins being the most critical element in establishing chronological sequences). The system used here is adapted from Osmund Bopearachchi, supplemented by the views of R C Senior and occasionally other authorities.

INDO-GREEK KINGS AND THEIR TERRITORIES

Based on Bopearachchi (1991)Territories/

DatesPAROPAMISADAE

ARACHOSIA GANDHARA WESTERN PUNJAB EASTERN PUNJAB 200-190 BCE Demetrius I 190-180 BCE Agathocles Pantaleon 185-170 BCE Antimachus I 180-160 BCE Apollodotus I 175-170 BCE Demetrius II 160-155 BCE Antimachus II 170-145 BCE Eucratides 155-130 BCE Menander I 130-120 BCE Zoilos I Agathokleia 120-110 BCE Lysias Strato I 110-100 BCE Antialcidas Heliokles II 100 BCE Polyxenios Demetrius III 100-95 BCE Philoxenus 95-90 BCE Diomedes Amyntas Epander 90 BCE Theophilos Peukolaos Thraso 90-85 BCE Nicias Menander II Artemidoros 90-70 BCE Hermaeus Archebios Yuezhi tribes Maues (Indo-Scythian) 75-70 BCE Telephos Apollodotus II 65-55 BCE Hippostratos Dionysios 55-35 BCE Azes I (Indo-Scythian) Zoilos II 55-35 BCE Apollophanes 25 BCE- 10 CE Strato II Rajuvula (Indo-Scythian) [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-Greek. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-06]

ca. 184 v. Chr.

Puṣyamitra (regiert ca. 184 - 150 v. Chr.) ermordet den letzten Maurya und begründet die Śuṅga-Dynastie.

ca. 180 - 169 v. Chr.

Eine griechische Armee vertreibt Puṣyamitra aus Sagala (heute Sialkot سیالکوٹ) und dringt bis Pāṭaliputra (heute Patna) vor.

ca. 175 v. Chr.

Apollodotus I (Απολλόδωτος Α΄) wird Nachfolger von Agathokles (Αγαθοκλής) (ca. 182) in Taxila und anderen griechischen Territorien westlich des Jhelām

ca. 165-163 v. Chr.

Abb.: Silbertetradrachme Eukratides' I. Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

"Obv: Bust of Eucratides, helmet decorated with a bull's horn and ear, within bead and reel border.

Rev: Depiction of the Dioscuri, each holding palm in left hand, spear in righthand. Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΕΥΚΡΑΤΙΔΟΥ (BASILEŌS MEGALOU EUKRATIDOU) "Of Great King Eucratides". Mint monogram below.

Characteristics: Diameter 32 mm. Weight 15.9 g. Attic standard. One of the largest Hellenic coins ever minted."[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eucratides_I. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-07]

Eucratides I (ca. 170 - 145) beseitigt die Dynastie der Nachfolger von Euthydemos I. von Baktrien (Ευθύδημος Α΄ της Βακτρίας) und begründet seine eigene Dynastie. Er stoßt bis in den Hindukush und Gandhāra vor. Ob er den Indus überschritt und Taxila erreichte, ist unklar.

ca. 165/155

Abb.: Münze Menanders (Rückseite Athene). Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Silberdrachme von Menander

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

"Obv: Greek legend, ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ ΜΕΝΑΝΔΡΟΥ (BASILEOS SOTEROS MENANDROU) lit. "Of Saviour King Menander".

Rev: Kharosthi legend: MAHARAJA TRATASA MENADRASA "Saviour King Menander". Athena advancing right, with thunderbolt and shield. Taxila mint mark."[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Menander_I. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-07]

Menander (Μένανδρος) wird König Baktriens. Er vereinigt Gebiete östlich und westlich des Jhelām. Seine Hauptstadt ist Sagala (heute: Sialkot: سیالکوٹ).

Menander ist Gegenstand des buddhistischen Milindapañha (siehe: Payer, Alois: Materialien zur buddhistischen Psychologie. -- 2. Milindapañha: Die Frage nach dem Ich. -- 1. Einführung. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/buddhpsych/psych021.htm)

ca. 140 v. Chr.

Die Griechen weichen in Baktrien den iranischen Śaka (Saka, Σάκαι), einem skythischen (Σκύθης) Volk.

Abb.: Gebiet der Skythen um ca. 100 v. Chr.

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

ca. 125 v. Chr.

Abb.: Silberdrachme von Antialcidas (Αντιαλκίδας). Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

"Obv: Bust of Antialcidas wearing a helmet, with Greek legend BASILEOS NIKEPHOROU ANTIALKIDOU "(Coin) of victorious King Antialcidas".

Rev: Seated Zeus with lotus-tipped sceptre, with Nike on his extended arm, holding out a wreath to a baby elephant with bell. Kharoshti legend: MAHARAJASA JAYADHARASA ANTIALIKITASA "Victorious King Antialcidas"."[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antialcidas. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-07]

Antialcidas (Αντιαλκίδας) wird König von Taxila. Er sendet im 14. Jahr seiner Herrschaft eine Gesandtschaft unter Heliodorus, Sohn des Dion, zum Śuṅga-König Kaśīputra Bhāgabhadra nach Vidiśā. Heliodorus lässt in Vidiśā eine Säule zu Ehren Viṣṇus errichten:

"Devadevasa Va [sude]vasa Garudadhvajo ayam karito i[a] Heliodorena bhagavatena Diyasa putrena Takhasilakena Yonadatena agatena maharajasa Amtalikitasa upa[m]ta samkasam-rano Kasiput[r]asa [Bh]agabhadrasa tratarasa vasena [chatu]dasena rajena vadhamanasa" "This Garuda-standard of Vasudeva (Krishna or Vishnu), the God of Gods was erected here by the devotee Heliodoros, the son of Dion, a man of Taxila, sent by the Great Greek (Yona) King Antialkidas, as ambassador to King Kasiputra Bhagabhadra, the Savior son of the princess from Benares, in the fourteenth year of his reign." "Trini amutapadani‹[su] anuthitani nayamti svaga damo chago apramado" "Three immortal precepts (footsteps)... when practiced lead to heaven: self-restraint, charity, consciousness." Übersetzung: Archaeological Survey of India, Annual Report (1908-1909)

ca. 100 v. Chr.

Die Śakas werden aus Baktrien durch die zentralasiatischen Yuezhi (Yüeh-Chih) (月氏 / 月支) vertrieben.

Abb.: Der Vorstoß der Yuezhi (Yüeh-Chih) (月氏 / 月支)

[Bildquelel: Wikipedia, Public domain]

ca. 90 v. Chr.

Abb.: Silbertetradrachme von Maues. Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

"The obverse shows Zeus standing with a sceptre. The Greek legend reads ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΜΑΥΟΥ ((of the) Great King of Kings Maues). The reverse shows Nike standing, holding a wreath. Kharoshthi legend. Taxila mint." [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maues. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-07]

Archebius, der letzte griechische König Taxilas, wird vom Śaka Maues entmachtet. Mit ihm beginnen die indo-skythischen Dynastien (Śaka und parthische) in Taxila (Daten ohne Gewähr!):

- Vonones (ca. 75). Śpalahores, danach Śpalagadames sind seine Beauftragten in Taxila.

- (?) Hermaeus

Abb.: Silberdrachme des Hermaeus. Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"Obv: Helmetted bust of Hermaeus " with Greek legend: BASILEOS SOTĒROS ERMAIOU "Of The Saviour King Hermaeus.

Rev: Zeus-Mithra seated on throne, with scepter, and making a benediction gesture with the right hand. Monogram. Kharoshti legend MAHARAJA TRATARASA HERMAYASA "Of The Saviour King Hermaeus"."[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hermaeus

- Azes I (c. 38 b.c.), Rājuvula ist sein Beauftragter in Taxila.

Abb.: Münze von Azes I. Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"Obv: Azes I in military dress, on a horse, with couched spear. Greek legend: BASILEOS BASILEON MEGALOU AZOU "of the Great King of Kings Azes".

Rev: Zeus with long scepter and thunderbolt. Kharoshti legend: MAHARAJASA RAJARAJASA MAHATASA AYASA "of the Great King of Kings Azes"2[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Azes. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-07]

- Azilises (c. 10 b.c.).

- Azes II (c. a.d. 5), Aśpavarma, der strategos, ist sein Beauftragter in Taxila.

- Gondophares, with Aśpavarma, Sasan, (Abdagases?) sind nacheinander seine Beauftragten in Taxila

- Pacores (c. a.d. 50), Sasan ist sein Beauftragter in Taxila

Eine andere Chronologie:

Nordwestindien:

- Maues, ca. 90–60 v. Chr.

- Vonones, ca. 75–65 v. Chr.

- Śpalahores, ca. 75–65 v. Chr.

- Śpalirises, ca. 60–57 v. Chr.

- Azes I., ca. 57–35 v. Chr.

- Azilises, ca. 57–35 v. Chr.

- Azes II., ca. 35–12 v. Chr.

- Zeionises, ca. 10 v. Chr.–10 n. Chr.

- Kharahostes, ca. 10 v. Chr.–10 n. Chr.

- Hajatria

- Liaka Kusuluka, Satrap von Chuksa

- Kusulaka Patika, Satrap von Chuksa und Sohn von Liaka Kusulaka

[Quelle der zweiten Chronologie: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-skythische_Dynastie. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-07]

ca. 53 v. Chr.

"Vonones, Suren of Eastern Iran, assumes imperial title left vacant by death of Maues. The suzerainty of Vonones is acknowledged by Spalahores (Spalyris), contemporary ruler of Arachosia, and by his successors, Spalagadames and Spalirises. It is also acknowledged at Taxila, where Spalahores and Spalagadames probably acted as Vonones' legates."

[Quelle: Marshall, John <1876 - 1958>: A guide to Taxila / by Sir John Marshall. - 4. ed.. - Karachi : Sani Communications, 1983. - V, 195 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Cambridge : University Press, for the Dept. of Archaeology in Pakistan, 1960. -- S. 43.]

ca. 38 v. Chr.

Rajuvula errichtet im östlichen Panjāb eine Satrapie, später weitet er seine Satrapie auf Mathurā und Taxila aus und nennt sich mahākṣatrapa.

ca. 25 v. Chr.

Der Parther Gondophares (ΥΝΔΟΦΕΡΡΗΣ, Vindafarna) besiegt den Skythen Azes II. und errichtet seine Hauptstadt in Taxila.

ca. 40 n. Chr.

Der Apostel Thomas besucht den Hof von Gondophares. (Siehe unten!)

nach. 40 n. Chr.

Der griechische Philosoph, Heilslehrer und Mirakelmann Apollonios von Tyana (Ἀπολλώνιος ὁ Τυανεύς) besucht Taxila.

nach 90 n. Chr.

Abb.: Doppel-Stater von V'ima Kadphises. Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

"Obv: King wearing a crested helmet, with a long and heavy coat and holding a club. Flames issuing from shoulders. Seated on a low couch. Greek legend: BASILEUS OOIMO KADPHISIS "King Vima Kadphises".

Rev: Shiva, radiate, wearing a necklace, with a long trident in right hand, in front of a bull. Kharoshthi legend MAHARAJASA RAJADIRAJASA SARVALOGA ISVARASA MAHISVARASA VIMA KATHPHISASA TRADARA "The Great king, the king of kings, lord of the World, the Mahisvara (a name of Shiva), Vima Kathphisa, the defender".From "Indo-Greek Coins" Whitehead, 1914 edition. Public Domain."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Plate_XX_Vima_Kadphises.jpg. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-07]

Der Kuṣāṇa-Herrscher V'ima Kadphises (Οοημο Καδφισης, 阎膏珍) erobert Gandhara und West-Panjāb. Er führt eine Goldwährung ein. Der Standard entspricht den römischen aurei.

78 n. Chr.

Beginn der Śaka-Ära

Abb.: Das Kuṣāṇa-Reich

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

ca. 80 n. Chr.

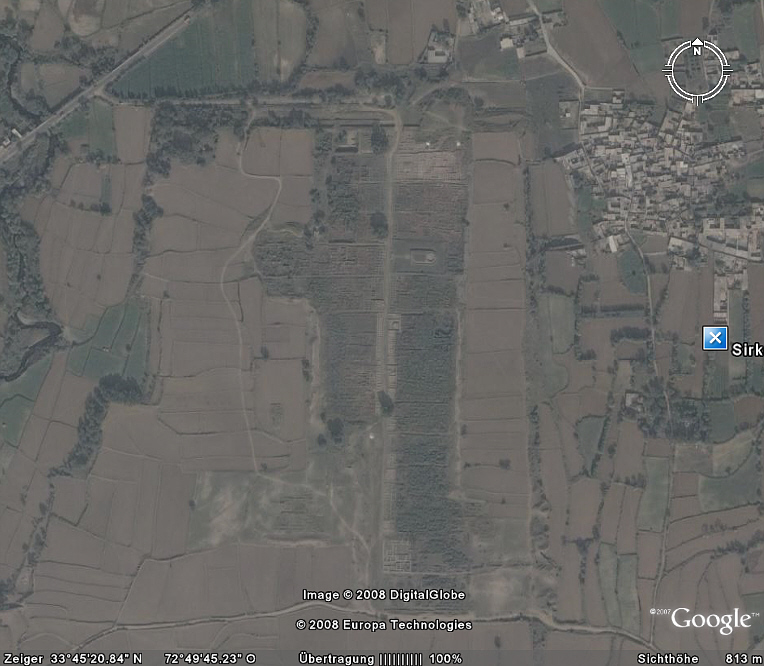

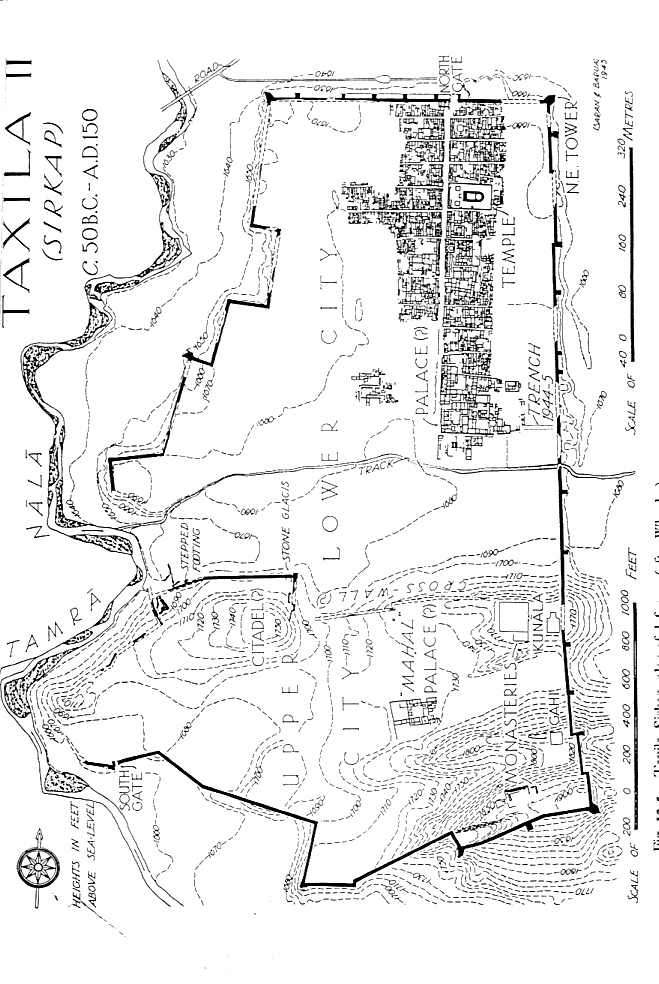

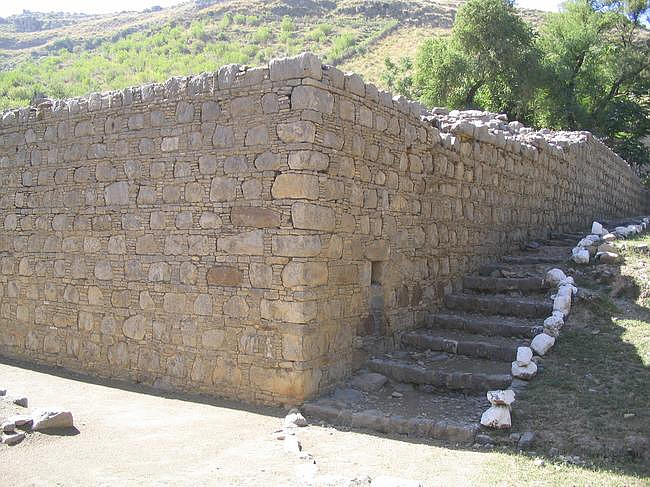

Gründung von Sirsukh.

ca. 230 n. Chr.

Ardaschir I. (Ardašir; اردشیر) (regierte 224 – 239/40), der Begründer des persischen Sassanidenreichs (پادشاهی ساسانیان) besiegt die Kuṣānas von Baktrien und dringt in den Hindukush, Gandhara und den westlichen Panjāb vor. Von da ab zerfallt die Macht der Kuṣāna südlich des Hindukush.

ca. 350 - 358

Der Sassaniden-Großkönig Schapur II. (شاپور) (309 - 379) Besetzt das Kabul-Tal, Gandhāra und Panjāb und bringt Taxila unter persische Herrschaft. In Taxila sieht man den Einfluss des persischen Kupfergeldes.

nach 350

Beginn der Herrschaft der Kidariten, eine Nachfolgedynastie der Kuṣāna, in Taxila

ca. 400

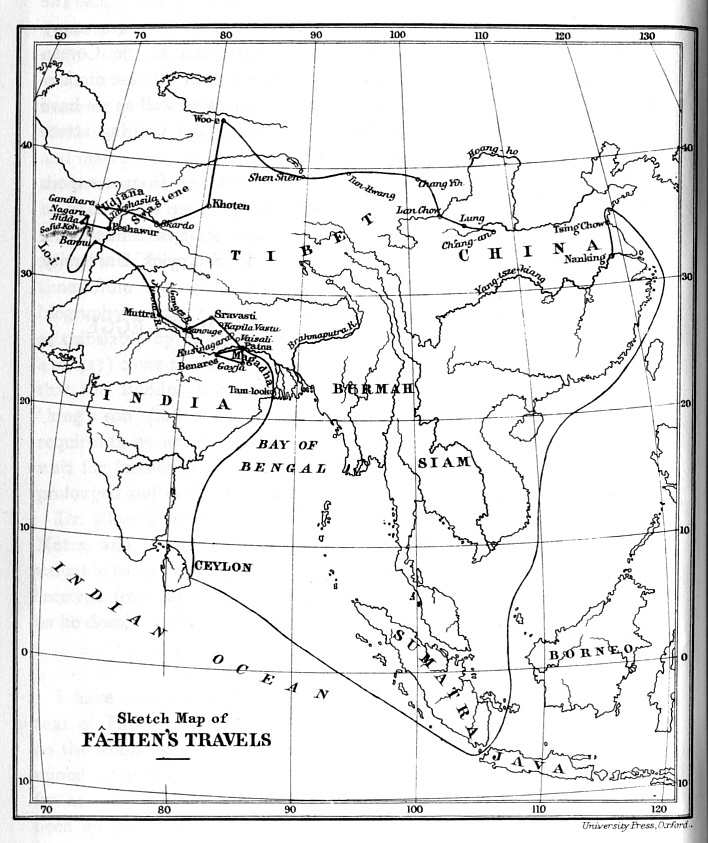

Der chinesische buddhistische Mönch Fǎxiǎn (Fa-hsien) (法顯) (377 - 422) besucht Taxila (siehe unten!)

ca. 460 - 470

Abb.: Münze des Hephthaliten König Lakhana von Oḍḍiyāna. Inschrift: "Raja Lakhana (udaya)ditya". Solche Münzen wurden auch in Taxila gefunden.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]Invasion der Hephthaliten (Weißen Hunnen). Sie zerstören in Taxila alle buddhistischen Klöster und Stūpa. Damit Ende der Blütezeiten Taxilas.

630 - 643

Der chinesische buddhistische Mönch Xuánzàng (Hsüan-tsan) (玄奘) (603 - 664) bereist Indien und besucht Taxila (siehe unten)

Die Aussagen über Takkasilā in der buddhistischen Pāli-Literatur fasst G. P. Malalasekera zusammen:

"Takkasilā The capital of Gandhāra. It is frequently mentioned as a centre of education, especially in the Jātakas. It is significant that it is never mentioned in the suttas, though, according to numerous Jātaka stories, it was a great centre of learning from pre-Buddhistic times. The Commentaries mention that in the Buddha's day, also, princes and other eminent men received their training at Takkasilā. Pasenadi, king of Kosala, Mahāli, chief of the Licchavis, and Bandhula, prince of the Mallas, were classmates in the university of Takkasilā (DhA.i.337). Among others described as being students of Takkasilā are Jīvaka, Angulimāla, Dhammapāla of Avanti, Kanhadinna, Bhāradvāja and Yasadatta (q.v.).

From Benares to Takkasilā was a distance of two thousand yojanas (J.i.395), though we are told that sometimes the journey was accomplished in one day (J.ii.47). The road passed through thick jungle infested by robbers (DhA.iv.66). Takkasilā was, however, a great centre of trade; people flocked to it from various parts of the country (MNid.i.154), not only from Benares, but also from Sāvatthi, from which city the road lay through Soreyya (DhA.i.326). In ancient times students came to the university from Lāla (J.i.447), from the Kuru country (DhA.iv.88), from Magadha (J.v.161), and from the Sivi country (J.v.210).

The students in the university studied the three Vedas and the eighteen sciences (vijjā) (J.i.159), which evidently included the science of archery (J.i.356; DhA.iv.66; also medicine and surgery, Vin.i.269f), the art of swordmanship (J.v.128), and elephant-craft (hatthi-sutta) (J.ii.47). Mention is also made of the study of magic, such as the ālambanamanta, for charming snakes (J.iv.457), and the Nidhiuddharanamanta, for recovering buried treasure (J.iii.116). The students were also taught the science of ritual (manta) (J.ii.200); but in this branch of learning Benares seems to have had a greater reputation, for we find students being sent there from Takkasilā in order to learn the mantas (DhA.iii.445).

The students generally paid a fee to the teacher on admission, the usual amount being one thousand gold pieces. They waited on the teacher by day and were taught by him at night. The paying students were entitled to various privileges, and lived with the teacher as members of his family, enjoying his constant company. The students seem mostly to have done their own domestic work, leading a co-operate life, gathering their own firewood and cooking their meals, though mention is made of servants, both male and female, helping in the various tasks (J.i.319).

Only brāhmanas and khattiyas appear to have been eligible for admission to Takkasilā (J.iv.391).

Discipline was evidently very rigorous, a breach of the rules being severely punished, irrespective of the status of the pupil, who was sometimes flogged on the back with a bamboo stick (J.ii.277f). Often the most promising students were given the daughters of the teachers in marriage as a mark of very special favour. (E.g., DhA.iv.66. Elsewhere (J.vi.347) it is stated that the teacher's daughter was given to the eldest pupil).

Sometimes the teacher and his pupils were invited to a meal at the house of a chief man of the city (J.iv.391). The principal teacher was called Disāpāmokkhācariya; under him were assistants, usually chosen from among his students, who were called pitthiācariyā (E.g., J.ii.100).

Takkasilā, being the capital of Gandhāra, was probably also the seat of government. Bimbisāra's contemporary in Gandhāra was Pukkusāti (J.i.399; ii.218). Mention is made in the Jātakas of a Takkasilā-rājā (AA.i.153; MA.i.335; ii.979, 987f). According to the Kumbhakāra Jātaka (q.v.), Takkasilā was the capital of Naggaji. The Dīpavamsa (iii.31) records that twelve kings, descendants of Dīpankara, ruled in succession at Takkasilā.

It is said in the Divyāvadāna (p.371) that Bindusāra's empire included Takkasilā. There was once a rebellion there and Aśoka was sent to quell it. From the minor Rock Edict II. of Aśoka it would appear that Takkasilā was the headquarters of a provincial government at Gandhāra, placed under a Kumāra or Viceroy. A rebellion broke out there again in the time of Aśoka, who sent his son Kunāla to settle it.

Takkasilā is identified with the Greek Taxila, in Rawalpindi in the Punjab."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

In den Thomasakten (Acta Thomae) aus dem 3. Jhdt. wird eine Begegnung des Apostels Thomas mit dem König Gondaphores berichtet. Dieser Text berichtet zwar nichts Nennenswertes über die Stadt, in der die Begegnung stattgefunden haben soll, und es ist auch nicht klar, ob es sich um Taxila oder eine andere Residenzstadt handelt; ich gebe diesen Text hier aber trotzdem wieder, da auf ihn immer wieder in der Literatur Bezug genommen wird, ohne dass klar ist, ob die Bezugnehmenden den Text überhaupt kennen.

"Thomasakten, das einzige vollständig erhaltene Buch einer Sammlung apokrypher Apostelakten, die unter dem Namen des Leucius Charinus umlief und Akten des Petrus, Johannes, Andreas, Paulus und Thomas umfasste. Im 4. Jh. zu einem Corpus verbunden, waren sie in gnostischen Kreisen, vor allem im Manichäismus in Gebrauch; doch sind sie auch bei den Enkratiten, den Apostolikern sowie bei Priscillian und seinen Anhängern bezeugt. Dass sie auch bei rechtgläubigen Christen beliebt waren, bezeugt die scharfe Verurteilung durch die Kirche. – Die Thomasakten sind in der 2. Hälfte des 3. Jh.s wahrscheinlich in Edessa in syrischer Sprache verfasst. Sie schildern die Mission des Apostels Thomas in Indien. Es ist jedoch fraglich, ob damit das heutige Indien gemeint ist. Eher ist darunter der äußerste Teil des Iran verstanden." [Quelle: H.-W. Bartsch. -- In: Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart. -- 3. Aufl. -- Bd. 6. -- 1963. -- S. 865]

"The Second Act: concerning his coming unto the king Gundaphorus. 17. Now when the apostle was come into the cities of India with Abbanes the merchant, Abbanes went to salute the king Gundaphorus, and reported to him of the carpenter whom he had brought with him. And the king was glad, and commanded him to come in to him. So when he was come in the king said unto him: What craft understandest thou? The apostle said unto him: The craft of carpentering and of building. The king saith unto him: What craftsmanship, then, knowest thou in wood, and what in stone? The apostle saith: In wood: ploughs, yokes, goads, pulleys, and boats and oars and masts; and in stone: plllars, temples, and court-houses for kings. And the king said: Canst thou build me a palace? And he answered: Yea, I can both build and furnish it; for to this end am I come, to build and to do the work of a carpenter.

18. And the king took him and went out of the city gates and began to speak with him on the way concerning the building of the court-house, and of the foundations, how they should be laid, until they came to the place wherein he desired that the building should be; and he said: Here will I that the building should be. And the apostle said: Yea, for this place is suitable for the building. But the place was woody and there was much water there. So the king said: Begin to build. But he said: I cannot begin to build now at this season. And the king said: When canst thou begin? And he said: I will begin in the month Dius and finish in Xanthicus. But the king marvelled and said: Every building is builded in summer, and canst thou in this very winter build and make ready a palace? And the apostle said: Thus it must be, and no otherwise is it possible. And the king said: If, then, this seem good to thee, draw me a plan, how the work shall be, because I shall return hither after some long time. And the apostle took a reed and drew, measuring the place; and the doors he set toward the sunrising to look toward the light, and the windows toward the west to the breezes, and the bakehouse he appointed to be toward the south and the aqueduct for the service toward the north. And the king saw it and said to the apostle: Verily thou art a craftsman and it belitteth thee to be a servant of kings. And he left much money with him and departed from him.

19. And from time to time he sent money and provision, and victual for him and the rest of the workmen. But Thomas receiving it all dispensed it, going about the cities and the villages round about, distributing and giving alms to the poor and afflicted, and relieving them, saying: The king knoweth how to obtain recompense fit for kings, but at this time it is needful that the poor should have refreshment.

After these things the king sent an ambassador unto the apostle, and wrote thus: Signify unto me what thou hast done or what I shall send thee, or of what thou hast need. And the apostle sent unto him, saying: The palace (praetorium) is builded and only the roof remaineth. And the king hearing it sent him again gold and silver (lit. unstamped), and wrote unto him: Let the palace be roofed, if it is done. And the apostle said unto the Lord: I thank thee O Lord in all things, that thou didst die for a little space that I might live for ever in thee, and that thou hast sold me that by me thou mightest set free many. And he ceased not to teach and to refresh the afflicted, saying: This hath the Lord dispensed unto you, and he giveth unto every man his food: for he is the nourisher of orphans and steward of the widows, and unto all that are afflicted he is relief and rest.

20. Now when the king came to the city he inquired of his friends concerning the palace which Judas that is called Thomas was building for him. And they told him: Neither hath he built a palace nor done aught else of that he promised to perform, but he goeth about the cities and countries, and whatsoever he hath he giveth unto the poor, and teacheth of a new God, and healeth the sick, and driveth out devils, and doeth many other wonderful things; and we think him to be a sorcerer. Yet his compassions and his cures which are done of him freely, and moreover the simplicity and kindness of him and his faith, do declare that he is a righteous man or an apostle of the new God whom he preacheth; for he fasteth continually and prayeth, and eateth bread only, with salt, and his drink is water, and he weareth but one garment alike in fair weather and in winter, and receiveth nought of any man, and that he hath he giveth unto others. And when the king heard that, he rubbed his face with his hands, and shook his head for a long space.

21. And he sent for the merchant which had brought him, and for the apostle, and said unto him: Hast thou built me the palace? And he said: Yea. And the king said: When, then, shall we go and see it? but he answered him and said: Thou canst not see it now, but when thou departest this life, then thou shalt see it. And the king was exceeding wroth, and commanded both the merchant and Judas which is called Thomas to be put in bonds and cast into prison until he should inquire and learn unto whom the king's money had been given, and so destroy both him and the merchant.

And the apostle went unto the prison rejoicing, and said to the merchant: Fear thou nothing, only believe in the God that is preached by me, and thou shalt indeed be set free from this world, but from the world to come thou shalt receive life. And the king took thought with what death he should destroy them. And when he had determined to flay them alive and burn them with fire, in the same night Gad the king's brother fell sick, and by reason of his vexation and the deceit which the king had suffered he was greatly oppressed; and sent for the king and said unto him: O king my brother, I commit unto thee mine house and my children; for I am vexed by reason of the provocation that hath befallen thee, and lo, I die; and if thou visit not with vengeance upon the head of that sorcerer, thou wilt give my soul no rest in hell. And the king said to his brother: All this night have I considered how I should put him to death and this hath seemed good to me, to flay him and burn him with fire, both him and the merchant which brought him (Syr. Then the brother of the king said to him: And if there be anything else that is worse than this, do it to him; and I give thee charge of my house and my children).

22. And as they talked together, the soul of his brother Gad departed. And the king mourned sore for Gad, for he loved him much, and commanded that he should be buried in royal and precious apparel (Syr. sepulchre). Now after this angels took the soul of Gad the king's brother and bore it up into heaven, showing unto him the places and dwellings that were there, and inquired of him: In which place wouldest thou dwell? And when they drew near unto the building of Thomas the apostle which he had built for the king, Gad saw it and said unto the angels: I beseech you, my lords, suffer me to dwell in one of the lowest rooms of these. And they said to him: Thou canst not dwell in this building. And he said: Wherefore ? And they say unto him: This is that palace which that Christian builded for thy brother. And he said: I beseech you, my lords, suffer me to go to my brother, that I may buy this palace of him, for my brother knoweth not of what sort it is, and he will sell it unto me.

23. Then the angels let the soul of Gad go. And as they were putting his grave clothes upon him, his soul entered into him and he said to them that stood about him: Call my brother unto me, that I may ask one petition of him. Straightway therefore they told the king, saying: Thy brother is revived. And the king ran forth with a great company and came unto his brother and entered in and stood by his bed as one amazed, not being able to speak to him. And his brother said: I know and am persuaded, my brother, that if any man had asked of thee the half of thy kingdom, thou wouldest have given it him for my sake; therefore I beg of thee to grant me one favour which I ask of thee, that thou wouldest sell me that which I ask of thee. And the king answered and said: And what is it which thou askest me to sell thee? And he said: Convince me by an oath that thou wilt grant it me. And the king sware unto him: One of my possessions, whatsoever thou shalt ask, I will give thee. And he saith to him: Sell me that palace which thou hast in the heavens ? And the king said: Whence should I have a palace in the heavens? And he said: Even that which that Christian built for thee which is now in the prison, whom the merchant brought unto thee, having purchased him of one Jesus: I mean that Hebrew slave whom thou desiredst to punish as having suffered deceit at his hand: whereat I was grieved and died, and am now revived.

24. Then the king considering the matter, understood it of those eternal benefits which should come to him and which concerned him, and said: That palace I cannot sell thee, but I pray to enter into it and dwell therein and to be accounted worthy of the inhabiters of it, but if thou indeed desirest to buy such a palace, lo, the man liveth and shall build thee one better than it. And forthwith he sent and brought out of prison the apostle and the merchant that was shut up with him, saying: I entreat thee, as a man that entreateth the minister of God, that thou wouldest pray for me and beseech him whose minister thou art to forgive me and overlook that which I have done unto thee or thought to do, and that I may become a worthy inhabiter of that dwelling for the which I took no pains, but thou hast builded it for me, labouring alone, the grace of thy God working with thee, and that I also may become a servant and serve this God whom thou preachest. And his brother also fell down before the apostle and said: I entreat and supplicate thee before thy God that I may become worthy of his ministry and service, and that it may fall to me to be worthy of the things that were shown unto me by his angels.

25. And the apostle, filled with joy, said: I praise thee, O Lord Jesu, that thou hast revealed thy truth in these men; for thou only art the God of truth, and none other, and thou art he that knoweth all things that are unknown to the most; thou, Lord, art he that in all things showest compassion and sparest men. For men by reason of the error that is in them have overlooked thee but thou hast not overlooked them. And now at mv supplication and request do thou receive the king and his brother and join them unto thy fold, cleansing them with thy washing and anointing them with thine oil from the error that encompasseth them: and keep them also from the wolves, bearing them into thy meadows. And give them drink out of thine immortal fountain which is neither fouled nor drieth up; for they entreat and supplicate thee and desire to become thy servants and ministers, and for this they are content even to be persecuted of thine enemies, and for thy sake to be hated of them and to be mocked and to die, like as thou for our sake didst suffer all these things, that thou mightest preserve us, thou that art Lord and verily the good shepherd. And do thou grant them to have confidence in thee alone, and the succour that cometh of thee and the hope of their salvation which they look for from thee alone; and that they may be grounded in thy mysteries and receive the perfect good of thy graces and gifts, and flourish in thy ministry and come to perfection in thy Father.

26. Being therefore wholly set upon the apostle, both the king Gundaphorus and Gad his brother followed him and departed not from him at all, and they also relieved them that had need giving unto all and refreshing all. And they besought him that they also might henceforth receive the seal of the word, saying unto him: Seeing that our souls are at leisure and eager toward God, give thou us the seal; for we have heard thee say that the God whom thou preachest knoweth his own sheep by his seal. And the apostle said unto them: I also rejoice and entreat you to receive this seal, and to partake with me in this eucharist and blessing of the Lord, and to be made perfect therein. For this is the Lord and God of all, even Jesus Christ whom I preach, and he is the father of truth, in whom I have taught you to believe. And he commanded them to bring oil, that they might receive the seal by the oil. They brought the oil therefore, and lighted many lamps; for it was night (Syr. whom I preach: and the king gave orders that the bath should be closed for seven days, and that no man should bathe in it: and when the seven days were done, on the eighth day they three entered into the bath by night that Judas might baptize them. And many lamps were lighted in the bath).

27. And the apostle arose and sealed them. And the Lord was revealed unto them by a voice, saying: Peace be unto you brethren. And they heard his voice only, but his likeness they saw not, for they had not yet received the added sealing of the seal (Syr. had not been baptized). And the apostle took the oil and poured it upon their heads and anointed and chrismed them, and began to say (Syr. And Judas went up and stood upon the edge of the cistern and poured oil upon their heads and said):

Come, thou holy name of the Christ that is above every name.

Come, thou power of the Most High, and the compassion that is perfect.

Come, gift (charism) of the Most High.

Come, compassionate mother.

Come, communion of the male.

Come, she that revealeth the hidden mysteries.

Come, mother of the seven houses, that thy rest may be in the eighth house.

Come, elder of the five members, mind, thought, refiection, consideration, reason; communicate with these young men.

Come, holy spirit, and cleanse their reins and their heart, and give them the added seal, in the name of the Father and Son and Holy Ghost.And when they were sealed, there appeared unto them a youth holding a lighted torch, so that their lamps became dim at the approach of the light thereof. And he went forth and was no more seen of them. And the apostle said unto the Lord: Thy light, O Lord, is not to be contained by us, and we are not able to bear it, for it is too great for our sight.

And when the dawn came and it was morning, he brake bread and made them partakers of the eucharist of the Christ. And they were glad and rejoiced.

And many others also, believing, were added to them, and came into the refuge of the Saviour.

28. And the apostle ceased not to preach and to say unto them: Ye men and women, boys and girls, young men and maidens, strong men and aged, whether bond or free, abstain from fornication and covetousness and the service of the belly: for under these three heads all iniquity cometh about. For fornication blindeth the mind and darkeneth the eyes of the soul, and is an impediment to the life (conversation) of the body, turning the whole man unto weakness and casting the whole body into sickness. And greed putteth the soul into fear and shame; being within the body it seizeth upon the goods of others, and is under fear lest if it restore other men's goods to their owner it be put to shame. And the service of the belly casteth the soul into thoughts and cares and vexations, taking thought lest it come to be in want, and have need of those things that are far from it. If, then, ye be rid of these ye become free of care and grief and fear, and that abideth with you which was said by the Saviour: Take no thought for the morrow, for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself. Remember also that word of him of whom I spake: Look at the ravens and see the fowls of the heaven, that they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and God dispenseth unto them; how much more unto you, O ye of little faith? But look ye for his coming and have your hope in him and believe on his name. For he is the judge of quick and dead, and he giveth to every one according to their deeds, and at his coming and his latter appearing no man hath any word of excuse when he is to be judged by him, as though he had not heard. For his heralds do proclaim in the four quarters (climates) of the world. Repent ye, therefore, and believe the promise and receive the yoke of meekness and the light burden, that ye may live and not die. These things get, these keep. Come forth of the darkness that the light may receive you! Come unto him that is indeed good, that ye may receive grace of him and implant his sign in your souls.

29 And when he had thus spoken, some of them that stood by said: It is time for the creditor to receive the debt. And he said unto them: He that is lord of the debt desireth alway to receive more; but let us give him that which is due. And he blessed them, and took bread and oil and herbs and salt and blessed and gave unto them; but he himself continued his fast, for the Lord's day was coming on (Syr. And he himself ate, because the Sunday was dawning).

And when night fell and he slept, the Lord came and stood at his head, saying: Thomas, rise early, and having blessed them all, after the prayer and the ministry go by the eastern road two miles and there will I show thee my glory: for by thy going shall many take refuge with me, and thou shalt bring to light the nature and power of the enemy. And he rose up from sleep and said unto the brethren that were with him: Children, the Lord would accomplish somewhat by me to-day, but let us pray, and entreat of him that we may have no impediment toward him, but that as at all times, so now also it may be done according to his desire and will by us. And having so said, he laid his hands on them and blessed them, and brake the bread of the eucharist and gave it them, saying: This eucharist shall be unto you for compassion and mercy, and not unto judgement and retribution. And they said Amen."

[Quelle der Übersetzung: The apocryphal New Testament / translated by M. R. (Montague Rhodes) James [1862 - 1936]. -- Oxford : Clarendon, 1924. -- Online: http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/actsthomas.html. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-07]

Abb.: Darstellung des Apollonius von Tyana auf römischer Münze

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

"Apollonios von Tyana (in Kappadokien), neupythagoreischer Philosoph, Theurg und Magier, der, ungefähr gleichalterig mit Christus, durch seine Reisen, Abenteuer, Prophezeiungen, sogenannte Wunder, großes Aufsehen bei seinen Zeitgenossen erregt zu haben scheint und ungefähr 100jährig in Ephesos starb. Von dem höchsten Gott hatte er eine gereinigte Vorstellung: ihm sollen keine Opfer gebracht, er soll nicht einmal mit Worten genannt, vielmehr nur mit dem Verstand erfasst werden. Tempel, Altäre und Bildsäulen wurden dem Apollonios in vielen Städten, besonders Kleinasiens und Griechenlands, errichtet sowie Münzen auf sein noch den Kaisern Caracalla, Aurelian und Alexander Severus heiliges Andenken geschlagen. Gegner des Christentums in alter und neuer Zeit stellten ihn neben Christus oder sogar über ihn, so Hierokles unter Diokletian, Voltaire, Wieland u.a. Eine ausführliche, romanhaft tendenziöse, historisch wertlose Biographie des Apollonios besitzen wir noch von Flavius Philostratos (s. d.), der sie auf Veranlassung der Julia Domna, Gemahlin des Septimius Severus, in acht Büchern niederschrieb. Die Schriften des Apollonios sind verloren bis auf 85 Briefe, die, wahrscheinlich unecht, mit jener Lebensbeschreibung in den Ausgaben der Werke des Philostratos von Westermann (Par. 1849) und Kayser (Bd. 1, Leipz. 1870) abgedruckt worden sind. Vgl. Baur, Apollonios von Tyana und Christus (Tübing. 1832); Jessen, Apollonios von Tyana und sein Biograph Philostratus (Hamb. 1885); Göttsching, Apollonios von Tyana (Berl. 1889)." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

Das Folgende ist eine Übersetzung aus dem griechischen "Leben des Apollonius von Tyana" des Flavius Philostratos (Φιλοστράτος) (um 200 n. Chr.):

"§19] And as they were being conveyed across the Indus, they say that they came across many river-horses and many crocodiles; and they say that the vegetation on the Indus resembles that which grows along the Nile, and that the climate of India is sunny in winter, but suffocating in summer; but to conteract this Providence has excellently contrived that it should often rain in their country . And they also say that they learned from the Indians that the king was in the habit of coming to this river when it rose in the appropriate seasons, and would sacrifice to the river black bulls and horses; for white is less esteemed by the Indians than black, because, I imagine, the latter is their own color; and when he has sacrificed, they say that he plunges into the river a measure of gold made to resemble that which is used in measuring wheat.

And why the king does this, the Indians, they say, have no idea; but they themselves conjectured that this measure was sunk in the river, either to secure the plentiful harvest, whose yield the farmers use such a measure to gauge, or to keep the river within its proper bounds and prevent it from rising to such heights as that it would drown the land.

[§20] And after they had crossed the river, they were conducted by the satrap's guide direct to Taxila, where the Indian had his royal palace. And they say that on that side of the Indus the dress of the people consists of native linen, with shoes of byblus and a hat when it rains; but that the upper classes there are appareled in byssus; and that the byssus grows upon a tree of which the stem resembles that of the white poplar, and the leaves those of the willow. And Apollonius says that he was delighted with the byssus, because it resembled his sable philosopher's cloak. And the byssus is imported into Egypt from India for many sacred uses.Taxila, they tell us, is about as big as Nineveh, and was fortified fairly well after the manner of Greek cities; and here was the royal residence of the personage who then ruled the empire of Porus.

And they saw a Temple, they saw, in front of the wall, which was not far short of 100 feet in size, made of porphyry,[3] and there was constructed within it a shrine, somewhat small as compared with the great size of the Temple which is surrounded with columns, but deserving of notice. For bronze tablets were nailed into each of its walls on which were engraved the exploits of Porus and Alexander. But the pattern was wrought with orichalcus and silver and gold and black bronze, of elephants, horses, soldiers, helmets, shields, but spears, and javelins and swords, were all made of iron; and the composition was like the subject of some famous painting by Zeuxis or Polygnotus and Euphranor, who delighted in light and shade; and, they say, here also was an appearance of real life, as well as depth and relief. And the metals were blended in the design, melted in like so many colors; and the character of the picture was also pleasing in itself, for Porus dedicated these designs after the death of the Macedonian, who is depicted in the hour of victory, restoring Porus who is wounded, and presenting him with India which was now his gift.

And it is said that Porus mourned over the death of Alexander, and that he lamented him as generous and a good prince; and as long as Alexander was alive after his departure from India, he never used the royal diction and style, although he had license to do so, nor issued kingly edicts to the Indians, but figured himself as satrap full of moderation, and guided every action by the wish to please Alexander.

§21] My argument does not allow me to pass over the accounts written of this Porus. For when the Macedonian was about to cross the river, and some of Porus' advisers wished him to make an alliance with the kings on the other side of the Hyphasis and the Ganges, urging that the invader would never face a general coalition against him of the whole of India, he replied: "If the temper of my subjects is such that I cannot save myself without allies, then for me it is better not to be king."

And when someone announced to him that Alexander had captured Darius, he remarked, "a king but not a man." And when the mule driver had caparisoned the elephant on which he meant to fight, he replied: "Nay, I shall carry him, if I prove myself the same man I used to be." And when they counseled him to sacrifice to the river, and induce it to reject the rafts of the Macedonians, and make it impassable to Alexander, he said: "It ill befits those who have arms to resort to imprecation."

And after the battle, in which his conduct struck Alexander as divine and superhuman, when one of his relations said to him: "If you had only paid homage to him after he had crossed, O Porus, you would not yourself have been defeated in battle, nor would so many Indians have lost their lives, nor would you yourself have been wounded," he said: "I knew from my report that Alexander was so fond of glory that, if I did homage to him, he would regard me as a slave, but if I fought him, as a king. And I much preferred his admiration to his pity, not was I wrong in my calculation. For by showing myself to be such a man as Alexander found me, I both lost and won everything that day."

Such is the character which historians give to this Indian, and they say that he was the handsomest of his race, and in stature taller than any man since the Trojan heroes, but that he was quite young, when he went to war with Alexander.

[...]

[§23] While the sage was engaged in this conversation, messengers and an interpreter presented themselves from the king, to say that the king would make him his guest for three days, because the laws did not allow of strangers residing in the city for a longer time; and accordingly they conducted him into the palace. I have already described the way in which the city is walled, but they say that it was divided up into narrow streets in the same irregular manner as in Athens, and that the houses were built in such a way that if you look at them from outside they had only one story, while if you went into one of them, you at once found subterranean chambers extending as far below the level of the earth as did the chambers above.

[§24] And they say that they saw a Temple of the Sun in which was kept loose a sacred elephant called Ajax, and there were images of Alexander made of gold, and others of Porus, though the latter were of black bronze. But on the walls of the Temple there were red stones, and gold glittered underneath, and gave off a sheen as bright as sunlight. But the statue was compacted of pearls arranged in the symbolic manner affected by all barbarians in their shrines.

[§25] And in the palace they say that they saw no magnificent chambers, nor any bodyguards or sentinels, but, considering what is usual in the houses of magnates, a few servants, and three or four people who wished, so I suppose, to converse with the king. And they say that they admired this arrangement more than they did the pompous splendor of Babylon, and their esteem was enhanced when they went within. For the men's chambers and the porticoes and the whole of the vestibule were in a very chaste style.

[§26] So the Indian was regarded by Apollonius as a philosopher, and addressing him through an interpreter, he said: "I am delighted, O king, to find you living like a philosopher.""And, I" said the other, "am delighted that you should think of me thus."

"And," said Apollonius, "is this customary among you, or was it you yourself established your government on so modest a scale?"

"Our customs," said the king, "are dictated by moderation, and I am still more moderate in my carrying them out; and though I have more than other men, yet I want little, for I regard most things as belonging to my own friends."

"Blessed are you then in your treasure," said Apollonius, "if you rate your friends more highly than gold and silver, for out of them grows up for you a harvest of blessings."

"Nay more," said the king, "I share my wealth also with my enemies. For the barbarians who live on the border of this country were perpetually quarreling with us and making raids into my territories, but I keep them quiet and control them with money, so that my country is patrolled by them, and instead of their invading my dominions, they themselves keep off the barbarians that are on the other side of the frontier, and are difficult people to deal with."

And when Apollonius asked him, whether Porus also had paid them subsidy, he replied: "Porus was as fond of war as I am of peace."

By expressing such sentiments he quite disarmed Apollonius, who was so captivated by him, that once, when he was rebuking Euphrates for his want of philosophic self-respect, he remarked: "Nay, let us at least reverence Phraotes the Indian," for this was the name of the Indian.

And when a satrap, for the great esteem in which he held the monarch, desired to bind on his brow a golden mitre adorned with various stones, he said: "Even if I were an admirer of such things, I should decline them now, and cast them off my head, because I have met with Apollonius. And how can I now adorn myself with ornaments which I never before deigned to bind upon my head, without ignoring my guest and forgetting myself?"

Apollonius also asked him about his diet, and he replied: "I drink just as much wine as I pour out in libation to the Sun; and whatever I take in the chase I give to others to eat, for I am satisfied with the exercise I get. But my own meal consists of vegetables and of the pith and fruit of date palms, and of all that a well-watered garden yields in the way of fruit. And a great deal of fruit is yielded to me by the trees which I cultivate with these hands."

When Apollonius heard this, he was more than gratified, and kept glancing at Damis.

[§27] And when they had conversed a good deal about which road to take to the Brahmans, the king ordered the guide from Babylon to be well entertained, as it was customary so to treat those who came from Babylon; and the guide from the satrap, to be dismissed after being given provisions for the road.

Then he took Apollonius by the hand, and having bidden the interpreter to depart, he said: "You will then, I hope, choose me for your boon companion."

And he asked question of him in the Greek tongue. But Apollonius was surprised, and remarked: "Why did you not converse with me thus, from the beginning?"

"I was afraid," said the king, "of seeming presumptuous, seeming, that is, not to know myself and not to know that I am a barbarian by decree of fate; but you have won my affection, and as soon as I saw that you take pleasure in my society, I was unable to keep myself concealed. But that I am quite competent in the Greek speech I will show you amply."

"Why then," said Apollonius, "did you not invite me to the banquet, instead of begging me to invite you?"

"Because," he replied, "I regard you as my superior, for wisdom has more of the kingly quality about it."

And with that he led him and his companions to where he was accustomed to bathe. And the bathing-place was a garden, a stade in length, in the middle of which was dug out a pool, which was fed by fountains of water, cold and drinkable; and on each side there were exercising places, in which he was accustomed to practice himself after the manner of the Greeks with javelin and quoit-throwing; for physically he was very robust, both because he was still young, for he was only seven-and-twenty years old, and because he trained himself in this way. And when he had had enough exercise, he would jump into the water and exercised himself in swimming.

But when they had taken their bath, they proceeded into the banqueting chamber with wreaths upon their heads; for this is the custom of the Indians, whenever they drink wine in the palace.

[§28] And I must on no account omit to describe the arrangement of the banquet, since this has been clearly described and recorded by Damis. The king then banquets upon a mattress, and as many as five of his nearest relations with him; but all the rest join in the feast sitting upon chairs.

And the table resembles an altar in that it is built up to the height of a man's knee in the middle of the chamber, and allows rooms for thirty to dispose themselves around it like a choir in a close circle. Upon it laurels are strewn, and other branches which are similar to the myrtle, but yield to the Indians their balm. Upon it are served up fish and birds, and there are also laid upon it whole lions and gazelles and swine and the loins of tigers; for they decline to eat the other parts of this animal, because they say that, as soon as it is born, it lifts up its front paws to the rising Sun.

Next, the master of ceremonies rises and goes to the table, and he selects some of the viands for himself, and cuts off other portions, and then he goes back to his own chair and eats his full, constantly munching bread with it. And when they all have had enough, goblets of silver and gold are brought in, each of which is enough for ten banqueters, and out of these they drink, stooping down like animals that are being watered.

And while they are drinking, they have brought in performers of various dangerous feats, not undeserving of serious study. For a boy, like one employed by dancing-girls, would be tossed lightly aloft, and at the same moment an arrow is aimed at him, up in the air, and when he was a long way from the ground, the boy would, by a tumblers' leap, raise himself above the weapen, and if he missed his leap, he was sure to be hit. For the archer, before he let fly, went round the banqueters and showed them the point of his weapon, and let them try the missile themselves. Shooting through a ring, too, or hitting a hair with an arrow, or for a man to mark the outline of his own son with arrows, as he stands in front of a board, keeps them occupied at their banquets, and they aim straight, even when they are drinking.

[§29] Well, the companions of Damis marveled at the accuracy of their eye, and were surprised at the exactness with which they aimed their weapons; but Apollonius, who ate with the king, since they agreed in diet, was less interested in these feats and said to the king: "Tell me, O King, how you acquired such a command of the Greek tongue, and whence you derived all your philosophical attainments in this place? For I don't imagine that you owe them to teachers, for it is not likely that there are, in India, any who could teach it."The king smiled and said: "In old days they would ask men who arrived by sea whether they were pirates, so common did they consider that way of living, hard though it is; but so far as I can make out, you Greeks ask your visitors whether they are not philosophers, so convinced you are that everyone you meet with must needs possess the divinest of human attainments. And that philosophy and piracy are one and the same thing among you, I am well aware; for they say that a man like yourself is not to be found anywhere; but that most of your philosophers are like people who have despoiled another man of his garment and then have dressed themselves up in it, although it does not fit them, and proceed to strut about trailing another man's garment. Nay, by Zeus, just as robbers live in luxury, well knowing that they lie at the mercy of justice, so are they, it is said, addicted to gluttony and riotous living and to delicate apparel.

And the reason is this: you have laws, I believe, to the effect that if a man is caught forging money, he must die, and the same if anyone illegally enrolls a child upon the register, or there is some penalty, I know not what; but people who utter counterfeit philosophy or corrupt her are not, I believe, restrained among you by any law, nor is there any authority set to suppress them.[§30] Now among us few engage in philosophy, and they are sifted and tried as follows: A young man so soon as he reaches the age of eighteen, and this I think is accounted the time of full age among you also, must pass across the river Hyphasis to the men who you are set upon visiting, after first making a public statement that he will become a philosopher, so that those who wish to may exclude him, if he does not approach the study in a state of purity. And by pure I mean, firstly, in respect of his parentage, that no disgraceful deed can be proved against either his father or his mother; next that their parents in turn, and the third generation upwards, are equally pure, that there was no ruffian among them, no debauchee, nor any unjust usurer.

And when no scar or reproach can be proved against them, nor any other stain whatever, then it is time narrowly to inspect the young man himself and test him, to see firstly, whether he has a good memory, and secondly, whether he is modest and reserved in disposition, and does not merely pretend to be so, whether he is addicted to drink, or greed, or a quack, or a buffoon, or rash, or abusive, to see whether he is obedient to his father, to his mother, to his teachers, to his school-masters, and above all, if he makes no bad use of his personal attractions.The particulars then of his parents and of their progenitors are gathered from witnesses and from the public archives. For whenever an Indian dies, there visits his house a particular authority charged by the law to make a record of him, and of how he lived. And if this officer lies or allows himself to be deceived, he is condemned by the law and forbidden ever to hold another office, on the ground that he has counterfeited a man's life.

But the particulars of the youths themselves are duly learnt by inspection of them. For in many cases a man's eyes reveal the secrets of his character, and in many cases there is material for forming a judgment and appraising his value in his eyebrows and cheeks, for from these features the dispositions of people can be detected by wise and scientific men, as images are seen in a looking-glass. For seeing that philosophy is highly esteemed in this country, and it is held in honor by the Indians, it is absolutely necessary that those who take to it should be tested and subjected to a thousand modes of proof.

Well then, that we study philosophy under direction of teachers, and that admission to philosophy is by examination among us, I have clearly explained; and now I will relate to you my own history.

[§31] [The king of Taxila continued:] "My grandfather was king, and had the same name as myself; but my father was a private person. For he was left quite young and two of his relations were appointed guardians in accordance with the laws of the Indians. But they did not carry on the king's government honestly on his behalf. No, by the Sun, but so unfairly that their subjects found their regime oppressive and the government fell into bad repute. A conspiracy then was formed against them by some of the magnates, who attacked them and slew them when they were sacrificing to the river Indus. The conspirators than seized upon the reins of government and took control of the State.

Now my father's kinsmen entertained apprehensions of him, because he was not yet sixteen years of age, so they sent him across the Hyphasis to the king there. And he has more subjects than I have, and his country is much more fertile than this one. This monarch wished to adopt him, but this my father declined on the ground that he would not struggle with fate that robbed him of his kingdom; but he besought to allow him to take his way to the sages and become a philosopher, for he said that this would make it easier for him to bear the reverses of his house. The king however being anxious to restore him to his father's kingdom, my father said: "If you see that I am become a genuine philosopher, then restore me; but if not, let me remain as I am."

The king accordingly went in person to the sages, and said that he would lie under great obligation to them if they would take care of a youth who had already showed such nobility of character, and they, discerning in him something out of the common run, were delighted to impart to him their wisdom, and were glad to educate him when they saw how addicted he was to learning.

Now seven years afterwards the king fell sick, and at the very moment when he was dying, he sent for my father, and appointed him co-heir in the government with his own son, and promised his daughter in marriage to him as she was already of marriageable age. And my father, since he saw that the king's son was the victim of flatterers and of wine and of such like vices, and was also full of suspicions of himself, said to him: "Do you keep all this and swill down the whole Empire as your own; for it is ridiculous that one who could not even gain the kingdom which belonged to him should presume to meddle with one which does not; but give me your sister, for this is all I want of yours."

So having obtained her in marriage he lived hard by the sage in seven fertile village which the king bestowed upon his sister as her pin-money. I then am the issue of this marriage, and my father after a Greek education brought me to the sages at an age somewhat too early perhaps, for I was only twelve at the time, but they brought me up like their own son; for any that they admit knowing the Greek tongue they are especially fond of, because they consider that in virtue of the similarity of his disposition he already belongs to themselves.

[§32] And when my parents had died, which they did almost together, the sages bade me repair to the villages and look after my own affairs, for I was now nineteen years of age. But, alas, my good uncle had already taken away the villages, and didn't even leave me the few acres my father had acquired; for he said that the whole of them belonged to his kingdom, and that I should get more than I deserved if he spared my life. I accordingly raised a subscription among my mother's freedmen, and kept four retainers.

And one day when I was reading the play The Children of Heracles, a man presented himself from my own country, bringing a letter from a person devoted to my father, who urged me to cross the river Hydraotes and confer with him about my present kingdom; for he said there was a good prospect of recovering it, if I did not dawdle. I cannot but think that some god set me on reading this drama at the moment, and I followed the omen; and having crossed the river I learnt that one of the usurpers of the throne was dead, and that the other was besieged in this very palace.

Accordingly I hurried forward, and proclaimed to the inhabitants of the villages through which I passed that I was the sons of so and so, naming my father, and that I was come to take possession of my own kingdom; but they received me with open arms and escorted me, recognizing my resemblance to my grandfather, and they had daggers and bows, and our numbers increased from day to day. And when I approached the gates the population received me with such enthusiasm that they snatched up torches off the altar of the Sun and came before the gates and escorted me hither with many hymns in praise of my father and grandfather. But the drone that was within they walled up, although I protested against his being put to such death."

[§33] Here Apollonius interrupted and said: "You have exactly played the part of the restored sons of Heracles in the play, and praised be the gods who have helped so noble a man to come by his own and restored you by their noble intervention. But tell me this about these sages: were they not once actually subject to Alexander, and were they not brought before him to philosophize about the heavens?""Those were the Oxydracae," he said, "and a race that has always been independent and well equipped for war; and they assert that they deal in wisdom, though they know nothing of value. But the genuine sages live between the Hyphasis and the Ganges, in a country which Alexander never assailed; not I imagine because he was afraid of what was in it, but, I think, because the omens warned him against it. But if he had crossed the Hyphasis, and had been able to take the surrounding country, he could certainly never have taken possession of their castle in which they live, not even if he had had ten thousand like Achilles, and thirty thousand like Ajax behind him; for they do not do battle with those who approach them, but they repulse them with prodigies and thunderbolts which they send forth, for they are holy men and beloved of the gods.

It is related, anyhow, that Heracles of Egypt and Dionysus after they had overrun the Indian people with their arms, at last attached them in company, and that they constructed engines of war, and tried to take the place by assault; but the sages, instead of taking the field against them, lay quiet and passive, as it seemed to the enemy; but as soon as the latter approached they were driven off by rockets of fire and thunderbolts which were hurled obliquely from above and fell upon their armor.

It was on that occasion, they say, that Hercules lost his golden shield, and the sages dedicated it as an offering, partly out of respect for Hercules' reputation, and partly because of the reliefs upon the shield. For in these Hercules is represented fixing the frontier of the world at Gadira, and turning the mountains into pillars, and confining the ocean within its bounds. Thence it is clear that it was not the Theban Hercules, but the Egyptian one, that came to Gadira, and fixed the limits of the world."

[§34] While they were thus talking, the strain of the hymn sung to the pipe fell upon their ears, and Apollonius asked the king what was the meaning of their cheerful ode. "The Indians," he answered, "sing their admonitions to the king, at the moment of his going to bed; and they pray that he may have good dreams, and rise up propitious and affable towards his subjects."

"And how," said Apollonius, "do you, O king, feel in regard to this matter? For it is yourself I suppose that they honor with their pipes."

"I don't laugh at them," he said, "for I must allow it because of the law, although I do not require any admonition of the kind: for in so far as a king behaves himself with moderation and integrity, he will bestow, I imagine, favors on himself rather than on his subjects."

[§35] After this conversation they laid themselves down to repose; but when a new day had dawned, the king himself went to the chamber in which Apollonius and his companions were sleeping, and gently stroking the bed he addressed the sage, and asked him what he was thinking about. "For," he said, "I don't imagine you are asleep, since you drink water and despise wine."

Said the other: "Then you don't think that those who drink water go to sleep?"

"Yes," said the king, "they sleep, but with a very light sleep, which just sits upon the tips of their eyelids, as we say, but not upon their minds."

"Nay with both do they sleep," said Apollonius, "and perhaps more with the mind than with the eyelids. For unless the mind is thoroughly composed, the eyes will not admit of sleep either. For note how madmen are not able to go to sleep because their mind leaps with excitement, and their thoughts run coursing hither and thither, so that their glances are full of fury and morbid impulse, like those of the dragons who never sleep.

Since then, O king," he went on, "we have clearly intimated the use and function of sleep, and what it signifies for men, let us examine whether the drinker of water need sleep less soundly than the drunkard."

"Do not quibble," said the king, "for if you put forward the case of a drunkard, he, I admit, will not sleep at all, for his mind is in a state of revel, and whirls him about and fills him with uproar. All, I tell you, who try to go to sleep when in drink seem to themselves to be rushed up on the roof, and then to be dashed down to the ground, and to fall into a whirl, as they say happened toIxion. Now I do not put the case of a drunkard, but of a man who has merely drunk wine, but remains sober; I wish to consider whether he will sleep, and how much better he will sleep than a man who drinks no wine."

And when no scar or reproach can be proved against them, nor any other stain whatever, then it is time narrowly to inspect the young man himself and test him, to see firstly, whether he has a good memory, and secondly, whether he is modest and reserved in disposition, and does not merely pretend to be so, whether he is addicted to drink, or greed, or a quack, or a buffoon, or rash, or abusive, to see whether he is obedient to his father, to his mother, to his teachers, to his school-masters, and above all, if he makes no bad use of his personal attractions.

The particulars then of his parents and of their progenitors are gathered from witnesses and from the public archives. For whenever an Indian dies, there visits his house a particular authority charged by the law to make a record of him, and of how he lived. And if this officer lies or allows himself to be deceived, he is condemned by the law and forbidden ever to hold another office, on the ground that he has counterfeited a man's life.

But the particulars of the youths themselves are duly learnt by inspection of them. For in many cases a man's eyes reveal the secrets of his character, and in many cases there is material for forming a judgment and appraising his value in his eyebrows and cheeks, for from these features the dispositions of people can be detected by wise and scientific men, as images are seen in a looking-glass. For seeing that philosophy is highly esteemed in this country, and it is held in honor by the Indians, it is absolutely necessary that those who take to it should be tested and subjected to a thousand modes of proof.

Well then, that we study philosophy under direction of teachers, and that admission to philosophy is by examination among us, I have clearly explained; and now I will relate to you my own history.

[§36] Apollonius then summoned Damis, and said: "'Tis a clever man with whom we are discussing and one thoroughly trained in argument."

"I see it is so, " said Damis, "and perhaps this is what is meant by the phrase 'catching a Tartar'. But the argument excites me very much, of which he has delivered himself; so it is time for you to wake up and finish it."

Apollonius then raised his head slightly and said: "Well I will prove, out of your own lips and following your own argument, how much advantage we who drink water have in that we sleep more sweetly. For you have clearly stated and admitted that the minds of drunkards are disordered and are in a condition of madness; for we see those who are under the spell of drink imagining that they see two moons at once and two suns, while those who have drunk less, even though they are quite sober, while they entertain no such delusions as these, are yet full of exultation and pleasure; and this fit of joy often falls upon them, even though they have not had any good luck, and men in such a condition will plead cases, although they never opened their lips before in a law court, and they will tell you they are rich, although they have not a farthing in their pockets.

Now these, O king, are the affections of a madman. For the mere pleasure of drinking disturbs their judgment, and I have known many of them who were so firmly convinced that they were well off, that they were unable to sleep, but leapt up in their slumbers, and this is the meaning of the saying that 'good fortune itself is a reason for being anxious.'

Men have also devised sleeping draughts, by drinking or anointing themselves with which, people at once stretch themselves out and go to sleep as if they were dead; but when they wake up from such sleep it is with a sort of forgetfulness, and they imagine that they are anywhere rather than where they are. Now these draughts are not exactly drunk, but I would rather say that they drench the soul and body; for they do not induce any sound or proper sleep, but the deep coma of a man half dead, or the light and distracted sleep of men haunted by phantoms, even though they be wholesome ones; and you will, I think, agree with me in this, unless you are disposed to quibble rather than argue seriously.

But those who drink water, as I do see things as they really are, and they do not record in fancy things that are not; and they were never found to be giddy, nor full of drowsiness, or of silliness, nor unduly elated; but they are wide awake and thoroughly rational, and always the same, whether late in the evening or early in the morning when the market is crowded; for these men never nod, even though they pursue their studies far into the night. For sleep does not drive them forth, pressing down like a stadholder upon their necks, that are bowed down by the wine; but you find them free and erect, and they go to bed with a clear, pure soul and welcome sleep, and are neither buoyed up by the bubbles of their own private luck, nor scared out of their wits by any adversity.