Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 6. Bewegliche Hinterlassenschaften. -- Fassung vom 2008-03-31. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen06.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2008-03-31

Überarbeitungen: 2008-07-16 [Ergänzungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

4. Holzarbeiten

Vorbemerkung:

In diesem Kapitel werden Texte zitiert bzw. wird auf Texte verwiesen, die Zustände nach 1858 wiedergeben. Dies geschieht nicht in der Annahme, dass die Zustände in Indien statisch waren; der "Fortschritt" zumindest in den Dörfern war aber gewiss so langsam, dass man von den geschilderten Zuständen vorsichtig auf Zustände früherer Zeiten extrapolieren darf. Die Texte sollen also vor allem einen Rahmen von Fragestellungen und möglichen Vorstellungen geben, in dem materielle unbewegliche Hinterlassenschaften als historische Quellen betrachtet werden können (vorsichtige Anwendung des ethnographischen Zugangs).

Die Auswahl der Bilder gibt keinen repräsentativen Querschnitt durch diese Art historischer Quellen, sondern ist in ihrer Einseitigkeit bedingt durch das Vorhandensein von Bildmaterial, das urheberrechtlich genutzt werden kann.

Unter "beweglichen Hinterlassenschaften" des Menschen verstehe ich hier alle beweglichen Relikte des Menschen in Indien bis 1858 mit Ausnahme derer, denen ich eigene Kapitel gewidmet habe, d.h. mit Ausnahme von

"Beweglichen Hinterlassenschaften" sind ein Teilgebiet von Sachzeugnissen (gegenständlichen Quellen) der Vergangenheit. Mit Thorsten Heese definiere ich diese so:

"Definition: Das Sachzeugnis als Quelle Gegenständliche Quellen sind materielle Überreste gelebter geschichtlicher Wirklichkeit. Als authentische, da unmittelbar überlieferte Materialisierungen vergangenen menschlichen Handelns zeugen sie von den Lebensumständen derjenigen Menschen, die sie geschaffen, benutzt und bewahrt haben. Sie bedürfen der Quellenkritik und -Interpretation."

"Definition: Das Sachzeugnis als Medium Gegenständliche Quellen sind materielle Medien für historisches Lernen, die Menschen früherer Zeiten selbst gewollt oder zufällig produziert haben. Sie besitzen einen monumentalen oder einen dokumentarischen Charakter."

[Quelle beider Zitate: Heese, Thorsten <1965 - >: Vergangenheit "begreifen" : die gegenständliche Quelle im Geschichtsunterricht. --Schwalbach/Ts. : Wochenschau-Verl. , 2007. -- 223 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- (Methoden historischen Lernens). -- ISBN 978-3-89974-331-9. -- S. 33, 35.]

Bewegliche Hinterlassenschaften sind also in unserem Zusammenhang u.a.

Thorsten Heese (a.a.O., S. 41 - 50) nennt folgende Kategorien gegenständlicher Quellen:

Folgende von Thorsten Heese für Schülerarbeiten genannten Arbeitsschritte gelten entsprechend für jedes historisches Arbeiten mit gegenständlichen Quellen:

"Übersicht: Arbeiten mit gegenständlichen Quellen

- Wahrnehmen: In einer ersten Begegnung werden die Schülerinnen und Schüler mit dem Gegenstand konfrontiert. Sie betrachten, beobachten, messen, wiegen, untersuchen, beschreiben, benennen, zeichnen die vorgestellte Quelle.

Leitfrage: Wie sieht der Gegenstand aus?

- Erschließen: Im zweiten Schritt wird die Quelle näher erschlossen. Herstellung, Entstehung und Funktionszusammenhang werden geklärt, indem z.B. mit dem Gegenstand (oder einer Nachbildung) hantiert und die ursprüngliche Funktionsweise ausprobiert wird. Es bietet sich dazu an, Vergleiche mit anderen Quellen oder Materialien anzustellen, zu recherchieren oder Experten zu befragen.

Leitfrage: Wie funktioniert der Gegenstand?

- Erkennen: In dieser Phase werden die Gegenstände historisch eingeordnet, politische, kulturelle, soziale Bezüge werden analysiert und daraus neue Erkenntnisse abgeleitet.

Leitfrage: Welche Bedeutung hat der Gegenstand?

- Ergebnisse dokumentieren: Die Ergebnisse können z.B. in Form einer Ausstellung, Broschüre oder Wandzeitung produktorientiert veröffentlicht und gesichert werden. Dies fördert die narrative Kompetenz der Schülerinnen und Schüler, ohne die historisches Bewusstsein nicht ausgebildet werden kann; und das Produkt ihrer Arbeit wird sichtbar. Leitfrage: Was lernen wir durch die Beschäftigung mit dem Gegenstand?"

[Quelle: Heese, Thorsten <1965 - >: Vergangenheit "begreifen" : die gegenständliche Quelle im Geschichtsunterricht. --Schwalbach/Ts. : Wochenschau-Verl. , 2007. -- 223 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- (Methoden historischen Lernens). -- ISBN 978-3-89974-331-9. -- S. 93.]

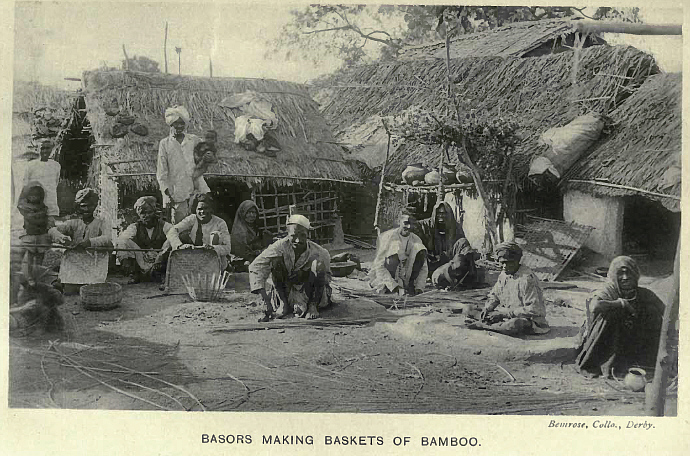

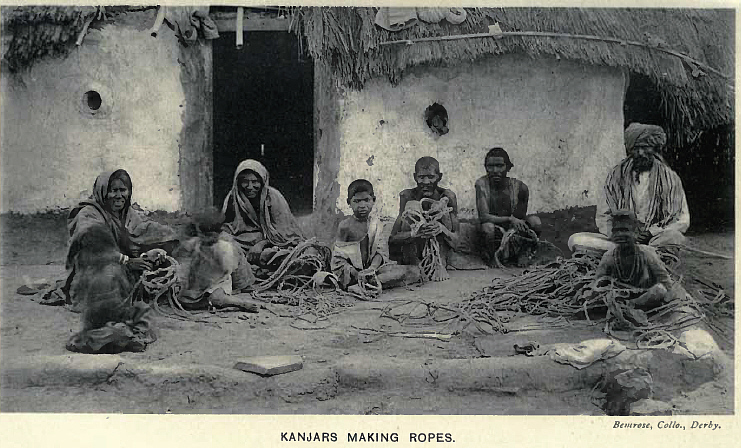

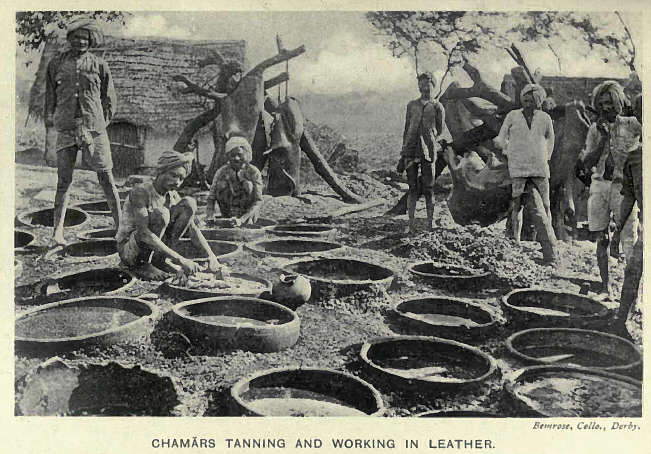

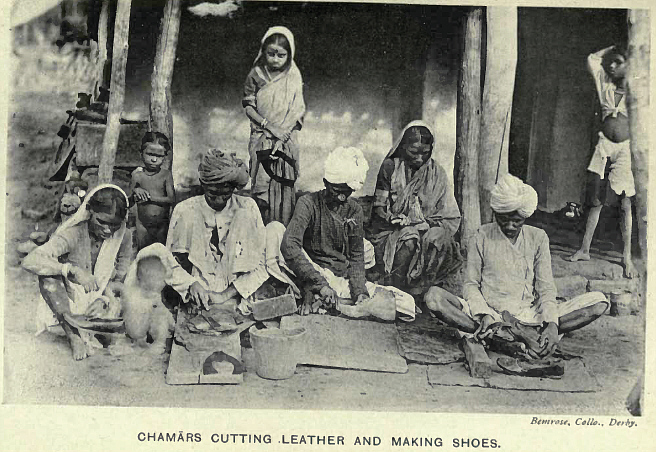

Da Handwerker in Indien meist zu den niederen Kasten (Stand der Śūdra) gehören, sind sie in den schriftlichen Quellen völlig unterrepräsentiert. Deshalb sind Handwerksprodukte oft die wichtigste Quelle für eine "Geschichte von unten", da sie Bruchtückchen zu einer solchen Geschichte beitragen und die Welt eines Teils der kleinen Leute lebendig werden lassen.

Indische Handwerker gehörten zu den besten der ganzen Welt; ihre Produkte waren begehrt:

"ARTS and MANUFACTURES. In several parts of the East Indies, as in British India, Ceylon, Burma, Siam, China, and Japan, the arts, in many of the branches and applications, attained a high position in very early ages ; and they have been fostered by generations of diligent men, who from father to son have dedicated their hearts and minds thereto, completing their work with tasteful and fitting details; their colouring, sombre but rich, with blended tints, softened hues, and modulated effect, is relieved with just enough of chastened and harmonious brightness as wins the admiration of all who appreciate the application of true principles to human industry. The great Exhibition of 1851 gave Europe the first opportunity for ascertaining the value of many of the products of India, and numerous articles were then selected for the schools of art of Europe to imitate ; and the subsequent exhibitions held in India and in the chief capitals of Europe have still further diffused the knowledge of the arts of those eastern countries.

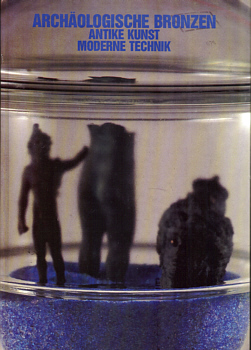

The artisans of India excel in anything requiring patience or accuracy of detail ; their patterns are [S. 171] tasteful and original. They are expert in executing tasteful designs in stucco or chunam, as solid ornaments for gateways, in alto-relievo for cornices, in perforated tracery for mosques and minarets, in floriated ornament or in the drawing of bold scroll patterns for interior decoration on a flat wall, with a broad continuous line of uniform thickness. This is a branch of art in which the natives of India far surpass European plasterers or decorators ; it is confined to a few localities in Southern India, and, like the celebrated old stone sculptures of the Ceded Districts, Mysore, Canara, and the Southern Mahratta country, it is an important branch of the fine arts of which very little is known, and the practice of which is gradually dying out from the want of proper encouragement. In the carving of wood, the chasing of metals, filagree work, weaving and embroidery, theyy excel ; and specimens of these in the Exhibition of 1851 were deemed of sufficient importance to be purchased as models of taste in design, care in execution, skill in the manipulation, and knowledge in the arrangement and harmony of colours. Their drawings on talc are characteristic, though out of proportion. There is considerable talent displayed in their modelling of toy figures of the different castes, and they have long been celebrated for their dexterity in founding bronze images. In the spinning and in the weaving and dyeing of cotton and silk stuffs, of such kinds as are suitable for the clothing that they wear and to their habits, the weavers and dyers of S.E. Asia are not approached by any European race. Though machinery makes cheaper articles, the labour of the hand is much more durable ; and their muslins, checks, and ginghams are not only greatly more lasting, but the colours are far more permanent. In field and garden cultivation, in the economy of water, and the utilisation of manures, there are several races skilled in varied degrees, though none excel the Chinese in their acquaintance with these subjects, to their acquisition of which they are stimulated by the example of the imperial family, the emperor annually ploughing the first field, and the empress and her attendants watching the silk-worms and their produce. Every European artificer and artist alike might well take the handicraftsmen of India for an example in the patience, perseverance, and thoroughness which are the ground of their excellency, and by which the inspirations of art are wrought into reality and life. The welfare of the arts is important both to India and to Europe, and the loss of them would be a serious blow to civilisation, and an injury to the pleasure and dignity of life. Reference to the articles on architecture, carpet-weaving, embroidery, enamelling, filagree work, ivory-carving, lacquer ware, pottery, Beder-ware, koft-gari, lapidary work, Bombay work, shawls, and sculpture, will show that the arts of S.E. Asia are indissolubly bound up with the popular institutions of the country ; and the patient Hindu handicraftsman's dexterity is a second nature, developed from father to son, working for generations at the same processes and manipulations. The 19th century has seen changes in British India which have greatly affected some branches of its arts and manufactures. While wars were unceasing, the armourer's trade occupied numbers of artisans, and as an art it was carried to a high degree of beauty, but with British supremacy the manufacture of arms has gradually ceased ; also the finer cotton goods from America and Great Britain have displaced the fancy muslins of Dacca and Arnee, which, however, only the few wealthy people purchased. Their workmen have taken to the workshops of railways; and although the looms of the villages hold their own, it is the strong, coarse cottons which the labouring classes prefer. Similarly, the introduction of printing, with supplies of cheap paper and the spread of education, have displaced numbers who earned a livelihood by the scriptory work of copying books ; while the iron and steel of Europe have shut up many of the smaller furnaces and forges. But other industries have been introduced or extended ; and tea, coffee, cotton, indigo, jute, coal and gold mining give employment to thousands. Agriculture is the greatest of all the Indian arts. Other large trades, employing thousands, are those of the tanner, salt maker, the makers of oils from the poppy-seed, sesamum, til, cocoa-nut, and seeds of the palma christi plant ; oils of kinds, valued at half a million sterling, are annually exported; and the rose and all other sweet-smelling flowers are made to produce the attar perfumes by distillation or enflowering.

The houses of the people are humble ; but the constructive capabilities of the races find opportunities for display in the erection of religious edifices and tombs, wells and tanks, for which woods, limestones, marble, sandstones, and greenstones are utilized. The polished chunam walls of the Madras houses are the admiration of all travellers.

The presents received in India by the Prince of Wales were exhibited in London in 1876. Skilled artistic labour was worthily represented by the gold and silver wares of Trichinopoly and Cuttack, the gold and silver lace of every large town, the brass, copper, tin, and zinc work ; their chasings and carvings, their trappings and caparisons ; the mother-of-pearl work of Ahmadabad ; the inlaid work of Agra, Multan, Sind, and Bombay; the horn and ivory work of Vizagapatam, Ceylon, China, and Japan ; the carved horn and tortoiseshell work of these countries ; the carpets, pottery, porcelain, and enamels, all bear comparison with the work of former times.

[...]

The art of enamelling is in the first rank of the handicrafts of the world, and at Jeypore is pursued to the highest degree of perfection yet known. The art there is exclusively Hindu, and the specimens presented to the Prince of Wales were the master art of the enameller.

The lacquer work of Burma, China, and Japan ; the marble work of Burma ; the lac work of Karnul ; the tutanague work of Beder ; the wood work of Nirmul and of Hyderabad in Sind ; the [S. 172] shawl and woollen work of Kashmir and the N.W. of India ; and the paintings on ivory in Dehli and the Peninsula.

The shawls of Kashmir have for ages been esteemed for their matchless colouring, due in part to the peculiar qualities of the air and water of that wondrous valley, but also to the appropriateness of the peculiar elaboration in the designs. Their art urgently needs encouragement, for European agents have interfered with the Kashmir workmen's designs, only to lose their characteristic loveliness.

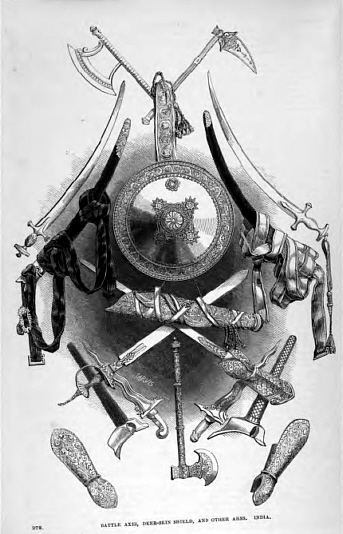

Koftgari work, or steel inlaid with gold, was in former days carried on to a considerable extent in various parts of Northern India. It was chiefly used for decorating armour ; and among the collections at the 1851 Exhibition, were some very fine specimens of guns, coats of mail, helmets, swords, and sword handles, to which the process of koftgari had been successfully applied. Since the revolt in India of 1857, the manufacture of arms has been generally discouraged, and koftgari work is consequently now chiefly applied to ornamenting a variety of fancy articles, such as jewel-caskets, pen and card trays, paper weights, paper knives, inkstands, etc. The process is exactly the same as that pursued in Europe, and the workman can copy any particular pattern required. The work is of high finish, and remarkable for its cheapness. Koftgari is chiefly carried on in Gujerat and Kotli, in the Sealkote district.

The tutanague work of Beder finds a ready sale, and admirable specimens of inlaid metal work by the native artisans of Bhooj are found in collections of arms.

The inlaid work of ivory, white and dyed, the ebony or coloured woods known as Multan or Bombay work, have become familiar to all Europe by the several exhibitions ; and the carved blackwood or rosewood furniture of Bombay is to be seen in many parts of India.

The splendour of Indian jewellers' work, in jewellery proper, and as seen on arms and armour, is due to the free use they make in it of diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and other gems. Their art permits them to use flat gems, mere scales, so light that they will float on water, and rubies and emeralds full of flaws, stones, in fact, which could only be used for the artistic effect that they produce when combined.

The inferior gems-- garnets, chalcedonies, and other silicious minerals -- are in extensive use ; and lapidaries find work in polishing and engraving them, and in forming potstone, figure-stone, and jades into useful and ornamental articles.

[...]

In 1880, Mr. C. P. Clarke was sent to India by the Art and Science Department to make purchases of the metal work of Madras and Kashmir, the wood carving of Ahmadabad and Canara, the pottery of. Madura and Multan, and the textile fabrics of Masulipatam, Jeypore, Dacca, Lucknow, Dehli, Ahmadabad, Sind, Bangalore, Malabar, and Central India. --

Morrison's Compendious Description ; Fortune's Chinese Books ; Sir R. Temple's India in 1880 ; Sir George Birdwood's Report on the Paris Exhibition."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 170ff.]

Gute Darstellungen der verschiedenen Handwerkerkasten und Handwerke betreibenden Volksgruppen findet man in:

Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde.

Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : Ill. ; 24 cm.

Abb.: Mädchen in vollem Ornat, Zentralindien, um 1916

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 3. -- Nach S. 378]

Siehe:

Watson, J. Forbes (John Forbes) <1827-1892>: The textile manufactures and the costumes of the people of India <Auszüge> / by John Forbes Watson (1866). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 6. Bewegliche Hinterlassenschaften, 1.). --Fassung vom 2008-03-27. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen06.htm

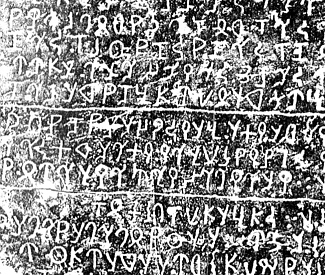

Abb.: Herstellung von Dacca-Musselin

[Bildquelle: Watson, J. Forbes (John Forbes) <1827-1892>: The textile manufactures and the costumes of the people of India. -- London : India Office, 1866. -- xxi, 173 S. : Ill. ; 39 cm. -- Pl. A. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/textilemanufactu00watsrich. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-36. -- "Not in copyright"]

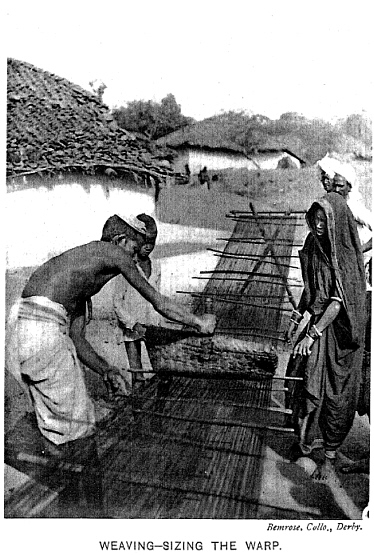

Folgende Ausführungen in Balfours Cyclopaedia (1885) geben eine gute Vorstellung von dem herausragenden Können indischer Textilhandwerker:

"TEXTILE ARTS. The east has, from the earliest times of which we have any record, been famous for its textile fabrics ; and India, notwithstanding the great mechanical inventions of the western world, is still able to produce her webs of woven air, which a manufacturer of the 18th century attempted to depreciate by calling them the shadow of a commodity, at the same time that his townsmen were doing all they could to imitate the reality, and which they have not yet been able to excel. Though the invention and completion of a loom for weaving would indicate a high degree of ingenuity as well as a considerable advance in some other arts, the Hindus were acquainted with it at a very early period, for in the hymns of the Rig Veda, composed about 1200 years B.C., weavers' threads are alluded to; and in the Institutes of Menu it is directed, 'Let a weaver who has received ten bales of cotton thread, give them back increased to eleven by the rice-water and the like used in weaving.' That cotton was employed at very early periods, is also evident from the Indian name of cotton, Karpas, occurring in the Book of Esther, i.6, in the account of the hangings in the court of the Persian palace at Shushan, on the occasion of the great feast given by Ahasuerus, -- white, green, and blue hangings ; the word corresponding to green is Karpas in the Hebrew. It seems to mean cotton cloth made into curtains, which were striped white and blue. Such may be seen throughout India in the present day, in the form of what are called purdahs. (Vide Essay on Antiquity of Hindu Medicine, p. 145.) The mode in which these are used, and the employment of the same colours in stripes, is still known as Shatranji, or cotton carpets. That the Hindus were in the habit of spinning threads of different materials, appears from another part of [S. 854] the Institutes of the same lawgiver, where it is directed that the sacrificial threads of a Brahman must be made of cotton, that of a Kshatriya (second caste) of sana (Crotalaria juncea), and that of a Vaisya of woollen thread. The natives of India prepare fabrics not only of cotton, but also of hemp and of jute and other substitutes for flax ; also of a variety of silks, and the wool of the sheep, goat, and camel, as well as mixed fabrics of different kinds. But it is for the delicacy of the muslins, especially of those woven at Dacca, that India was so long famous. From a careful examination of the cottons grown in different parts of India, as well as of those of other parts of the world, we find that it is not owing to any excellence in the raw material that the superiority in the manufacture was due, for English spinners say that the Indian cotton is little fit for their purposes, being not only short but coarse in staple. It is owing, therefore, to the infinite care bestowed by the native spinners and weavers on every part of their work, that the beauty of the fabric is due, aided as they are by that matchless delicacy of touch for which the Hindus have long been famous. According to one of their authors, 'the first, the beat, and most perfect of instruments is the human hand.' The Hindu weaver has been described as hanging his loom to a tree, and sitting with his feet on the ground. But this is the case only with the coarser fabrics ; and a late resident of Dacca has given a minute account of the cotton manufacture of that district, and has shown that great care is bestowed on every part of the process. The spinning-wheel is usually considered to be an improvement upon the distaff and spindle, as modern machinery is upon the inexpensive spinning-wheel. In facilitating work and diminishing expense, the spinning-wheel was no doubt a great improvement, and is still employed throughout India for the ordinary and coarser fabrics. But the spindle still holds its place in the hands of the Hindu women, when employed in spinning thread for the fine and delicate muslins to which the names of Shabnam or Dew of Night, Ab-i-Rawan or Running-water, etc., are applied by natives, and which no doubt formed the Tela vcntosa of the ancients ; and those called Gangitika in the time of Arrian were probably produced in the same locality. Mr. James Taylor, of the Bengal Medical Service, in a report which was sent by the Court of Directors to India, gave much interesting information respecting the cotton manufacture of Dacca. He showed that the Hindu woman first cards her cotton with the jaw-bone of the boalee fish, which is a species of Silurus ; she then separates the seeds by means of a small iron roller worked backwards and forwards upon a flat board. A small bow is used for bringing it to the state of a downy fleece, which is made up into small rolls to be held in the hand during the process of spinning. The apparatus required for this consists of a delicate iron spindle, having a small ball of clay attached to it, in order to give it sufficient weight in turning ; and imbedded in a little clay there is a piece of hard shell, on which the spindle turns with the least degree of friction. A moist air and a temperature of 80° is found best suited to this fine spinning, and it is therefore practised early in the mornings and in the evening, sometimes over a shallow vessel of water, the evaporation from which imparts the necessary degree of moisture. The spinners of yarn for the Chundeyree muslins in the dry climate of North- Western India are described as working in underground workshops, on account of the greater uniformity in the uniformity of the atmosphere. The Indian spinning-wheel is looked upon with contempt by those who look to the polish rather than to the fitness of a tool. Professor Cowper, than whom none was a better judge, observing that the wood-work of some of these spinning-wheels was richly carved, inferred that the strings with which the circumference was formed might have some use, and not have been adopted from poverty or from idleness. In making working models of these instruments, he has found that in no other way could he produce such satisfactory results as by closely imitating the models before him, the strings giving both tension and elasticity to the instrument. The spindles, moreover, being slightly bent or the hand held obliquely, the yarn at every turn of the spindle slips off the end and becomes twisted. The common dimensions of a piece of Dacca muslin are twenty yards in length by one in breadth. There are more threads in the warp than in the woof, the latter being to the former in a piece of muslin weighing twenty tolas or siccas, in the proportion of 9 to 11 ; one end of the warp is generally fringed, sometimes both. The value of a piece of plain muslin is estimated by its length and the number of threads in the warp, compared with its weight. The greater the length and number of threads, and the less the weight of the piece, the higher is its price. It is seldom, however, that a web is formed entirely of the finest thread which it is possible to spin. The local committee of Dacca having given notice that they would award prizes for the best piece of muslin which could be woven in time for the 1851 Exhibition, the prize of 25 rupees was awarded to Hubeeb Oollah, weaver of Golconda, near Dacca. The piece was ten yards long and one wide, weighed only 3 oz. 2 dwts., and might be passed through a very small ring. Though the cotton manufactures of India seem to have greatly fallen off, from the cheapness of English manufactured goods, the report of the Revenue Board, Madras, shows that up to the year 1871 weavers continued to increase in numbers. In the year 1850, it was stated by Dr. Taylor that, as the finest muslins formed but a small portion of goods formerly exported to England, the decay of the Dacca trade has had comparatively little influence on this manufacture, as these delicate manufactures still maintain their celebrity in the country, and are still considered worthy of being included among the most acceptable gifts that can be offered to her native princes ; and he believes that the muslin being then made was superior to the manufacture of 1790, and fully equal to that of the reign of Aurangzeb. Fine muslins have been sent to the Exhibitions in Europe, from Dacca, from Kishengarh in Bengal, from Collar, in the raja of Travanoore's dominions, as well as from Chundeyree in the Gwalior territories. Specimens of almost every variety of the cotton manufacture, such as the coarse garrha and guzzee for packing, clothing, and for covering corpses, with dosootee, etc., for tents, canvas for sails, towels, and table-cloths, and every variety of calico, were sent from Nepal and Assam, as well as from along the valley of the Ganges, from [S. 856] Bengal up to the Jullundhur Doab, in the Sikh territories ; also from Cutch, Ahmadabad, Surat, and Dharwar on the western side of India ; from the central territories of the Nizam, from Nagpur, and from the islands of the Indian Ocean. Fine pieces of calico and punjum longcloth were sent from Juggiapettah, in the Northern Circars, which was formerly the great seat of this manufacture. Some of the places noted for their manufactures did not grow their own cotton. Dacca no doubt grew most of what it required for its muslins, because the thread did not swell in bleaching, but it also imported cotton formerly from Surat, as well as from Central India. Azimgarh imports its cotton chiefly from the same source to which the Northern Circars was also formerly indebted, while Chundeyree imports its cotton from the distant valley of Nimar. The natives are acquainted with every kind of weaving, from guzzee and gauze, to striped, checkered, and flowered muslins. The last are a branch of art which has been long known in the east, and the mode of making which often puzzled weavers in Great Britain. In manufacturing figured (jamdanee) fabrics, Mr. Taylor informs us, they place the pattern, drawn upon paper, below the warp, and range along the track of the woof a number of cut threads, equal to the flowers or parts of the design intended to be made ; and then, with two small, fine-pointed bamboo sticks, they draw each of these threads between as many threads of the warp as may be equal to the width of the figure which is to be formed. When all the threads have been brought between the warp, they are drawn close by a stroke of the ley. The shuttle is then passed, by one of the weavers, through the shed, and the weft having been driven home, it is returned by the other weavers. Most of these flowered muslins are uniform in colour, but some are in two colours, and chiefly woven in Bengal. Specimens of double weaving in cotton, and showing considerable skill, with a pleasing arrangement of pattern and colours, were sent from Khyrpur, in Sind. These kinds are also woven in Ganjam. -- Royle on the Arts and manufactures of India, p. 487."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 3. -- 1885. -- S. 854 - 856]

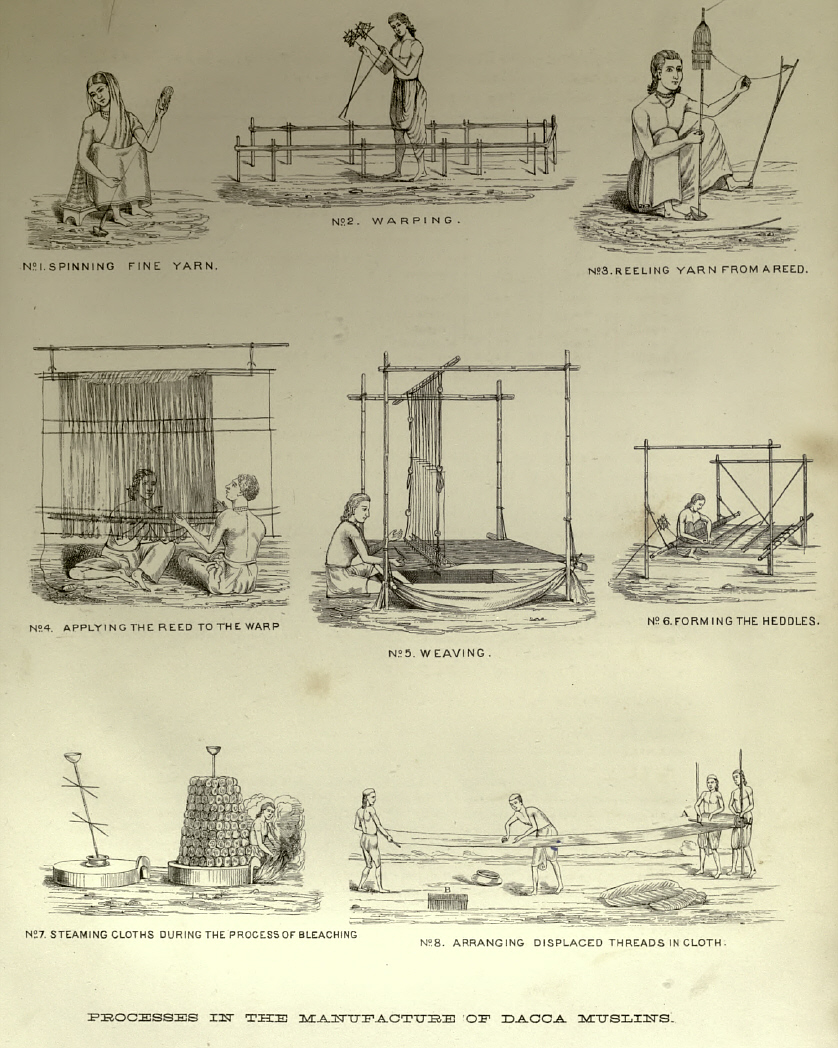

Abb.: Chhīpa (Stoffdrucker)

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 2. -- Nach S. 430.]

"PRINTED CLOTHS. The art of calico-printing is one which was common to the ancient Egyptians and Indians, and is still largely practised by the latter, and with a skill which produces much to be admired, even in the midst of the productions of the world, and after many attempts have been made to improve an art certainly imported from the east. Pliny was acquainted with the art by which cloths, though immersed in a heated dyeing liquor of one uniform colour, came out tinged with different colours, and afterwards could not be discharged by washing. The people of India were found practising the art when first visited by Europeans, and Calicut on the Malabar coast has given its name to calico.

The large cotton chintz counterpanes, called pallampoors (palangposh), which from an early period have been made in the East Indies, are prepared by placing on the cloth a pattern of wax, and dyeing the parts not so protected.

The colours used in calico-printing are derived from all the three kingdoms of nature, but it seldom happens that solutions, infusions, or decoctions of these colours admit of being applied at once to the cloth without some previous preparation, either of the cloth itself, or of the colouring [S. 293] material. It is often necessary to apply some substance to the cloth which shall act us a bond of union between it and the colouring matter. The substance is usually a metallic salt, which has an affinity for the tissue of the cloth as well as for the colouring matter when in a state of solution, and forms with the latter an insoluble compound. Such a substance is called a mordant (from the Latin Mordere, to bite), a term given by the French dyers, under the idea that it exerted a corrosive action on the fibre, expanding the pores, and allowing the colour to be absorbed. The usual mordants are common alum and several salts of alumina, peroxide of tin, protoxide of tin, and oxide of chrome. These have an affinity for colouring matters, but many of their salts have also a considerable attraction for the tissue of the cloth, which withdraws them to a certain extent from their solutions. Mordants are useful for all those vegetable and animal colouring matters which are soluble in water, but have not a strong affinity for tissues. The action of the mordant is to withdraw them from solution, and to form with them, upon the cloth itself, certain compounds which are insoluble in water. In European cloth-printing, although the methods employed are numerous, and the combinations of colours and shades of colour almost infinite, yet each colour in a pattern must, in the present state of the art, be applied by one of six different styles of work. These are termed

the madder style ;

printing by steam ;

the paddling style ;

the resist style ;

the discharge style ; and

the China-blue style.

By the proper combination of two or more of these styles, any pattern, however complicated, is produced. The processes actually required for finishing a piece of cloth are numerous, as, for example, in producing a red stripe upon a white ground, the bleached cloth is submitted to nineteen operations, as follows :

Printing on mordant of red liquor (a preparation of alumina) thickened with flour, and dyeing ;

ageing for three days ;

dunging ;

wincing in cold water ;

wasting at the dash-wheel

wincing in dung-substitute and size ;

wincing in cold water ;

dyeing in madder ;

wincing in cold water ;

washing at the dash-wheel ;

wincing in soap-water containing a salt of tin ;

washing at the dash-wheel ;

wincing in soap-water ;

wincing in a solution of bleaching-powder ;

washing at the dash-wheel ;

drying by the water extractor ;

folding;

starching;

drying by steam.

Indian dyers apply the mordants both by pencils and by engraved blocks. Blocks are used throughout India, but silk handkerchiefs had the parts where the round spots were to be, tied up with thread, so as not to be affected by the dye-liquors, and it was from this process of tying (bandhna) that they received the name of bandana. The cloth-printers at Dacca stamp the figures on cloth which is to be embroidered. The stamps are formed of small blocks of kautul (Artocarpus) wood, with the figures carved in relief. The colouring matter is a red earth imported from Bombay, probably the so-called Indian earth from the Persian Gulf. Though the art is now practised to much perfection in Europe, the Indian patterns still retain their own particular beauties, and command a crowd of admirers. This is no doubt due in a great measure to the knowledge which they have of the effects of colours, and the proportion which they preserve between the ground AIM! toe pattern, by which a good effect is procured both at distance and on a near inspection. Printed cloths are worn occasionally, as in Berar and Bundelkhand, for sarees ; and the ends and borders have peculiar local patterns. There is also a class of prints on coarse cloth, used for the skirte or petticoats of women of some of the lower classes in Upper India ; but the greatest demand for printed cloths is for palempores, or single quilts. In the costlier garments of India, the borders and ends are entirely of gold thread and silk, the former predominating. Printing in gold and in silver is a branch of the art which has been carried to great perfection in India, as well upon thick calico as upon fine muslin. The size which is used is not mentioned, but in the Burmese territory the juice of a plant is used, which no doubt contains caoutchouc in a state of solution.

There is a branch of cotton-printing carried on at Sholapur. The patterns of various kinds are printed upon coarse cloth, and are used for floor-coverings, bed-coverlets, etc. etc., the latter by the poorer classes. The colours are very permanent, and will bear any amount of washing, but are confined to madder reds, and browns, black, dull greens, and yellows. See Dyes.

The object of calico-printing is to apply one or more colours to particular parts of cloth, so as to represent a distinct pattern, and the beauty of a print depends on the elegance of the pattern and the brilliancy and contrast of the colours. The processes employed are applicable to linen, silk, worsted, and mixed fabrics, although they are usually referred to cotton cloth or calico. There are various methods of calico-printing, the simplest of which is block-printing by hand, in which the pattern or a portion thereof is engraved in relief upon the face of a block of sycamore, holly, or pear-tree wood, backed with deal, and furnished with a strong handle of boxwood. A machine, called the perrotine, in honour of its inventor, M. Perrot of Rouen, is in use in France and Belgium as a substitute for hand-block printing. Copperplate printing similar to that used in the production of engravings, has also been applied to calico-printing. The invention of cylinder or roller printing is the greatest achievement that has been made in the art, producing results which are truly extraordinary : a length of calico equal to one mile can by this method be printed off with four different colours in one hour, and more accurately and with better effect than block-printing by hand. By another method of calico-printing, namely, press-printing, several colours can be printed at once. The cloth to be printed is wound upon a roller at one end of the machine, and the design, which is formed in a block of mixed metal about 2½ feet square, is supported with its face downwards in an iron rame, and can be raised or lowered at pleasure. The face of the block is divided into as many stripes, ranging crossways with the table, as there are colours to be printed. -- Royle's Arts of India."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 3. -- 1885. -- S. 292f.]

Abb.: Schreiner, Madhogarh (माधोगढ), Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: von Dan.be. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/70534225@N00/383125840/. -- Zugriff am

2008-04-01. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Holzschnitzereien, Palast von Padmanabhapuram (பத்மனாபபுரம்), Tamil Nadu,

16-18. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: deepsan. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/deepsan/71720163/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Holzarbeit, Ahmedabad (અમદાવાદ),

Gujarat

[Bildquelle: Meanest Indian. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/meanestindian/403220887/. -- Zugriff am

2008-04-01. --

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

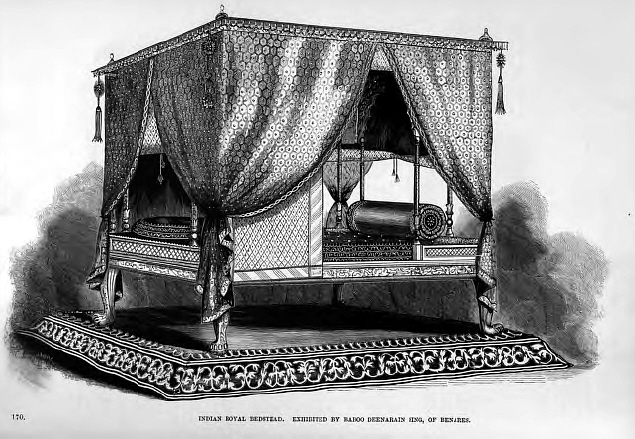

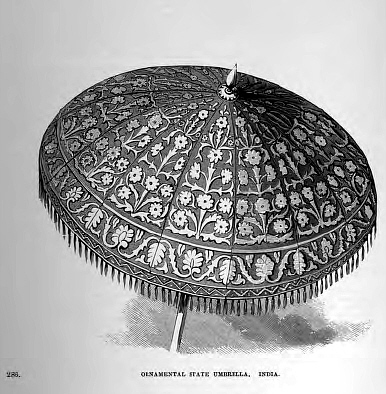

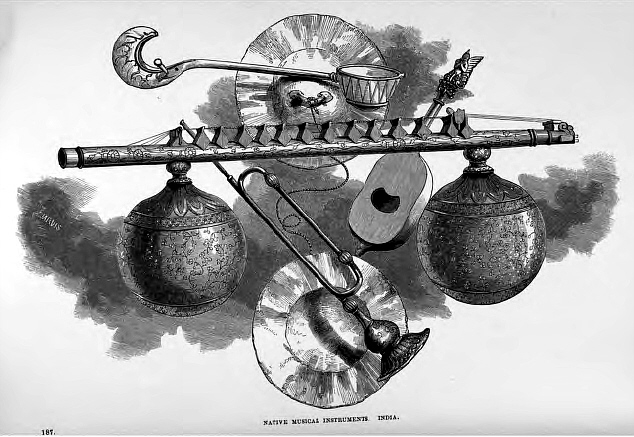

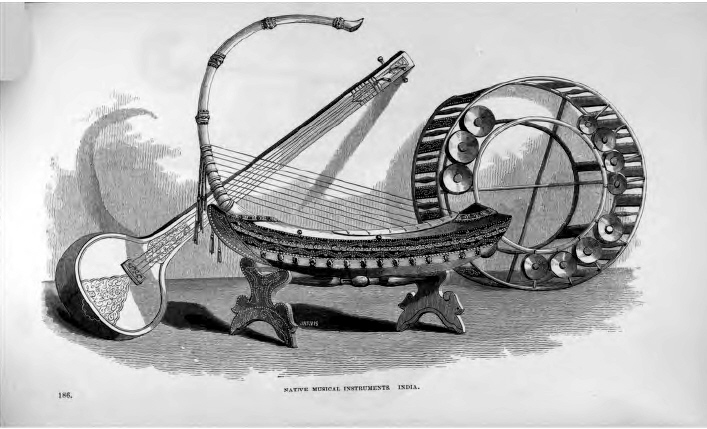

Abb.: Holzarbeit aus Indien, ausgestellt bei der Great Exhibition of the Works

of Industry of all Nations, London 1851

Abb.: Holzarbeit aus Indien, ausgestellt bei der Great Exhibition of the Works

of Industry of all Nations, London 1851

[Quelle der 2 Abb.: Official descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the Great exhibition of the works of industry of all nations, 1851 ... -- London : Spicer, 1851. -- Vol IV: Colonies - foreign states. Division I.]

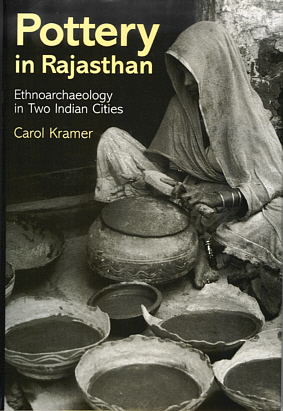

Abb.: Töpfer beim Lehmkneten, Jodhpur (जोधपुर), Rajasthan, 2006

Abb.: Töpfer beim Anwerfen des Rades, 2007

[Bildquelle: liketearsintherain. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/liketearsintherain/2099356535/. -- Zugriff am

2008-04-01. --

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons lizenz (Namensnennung)]

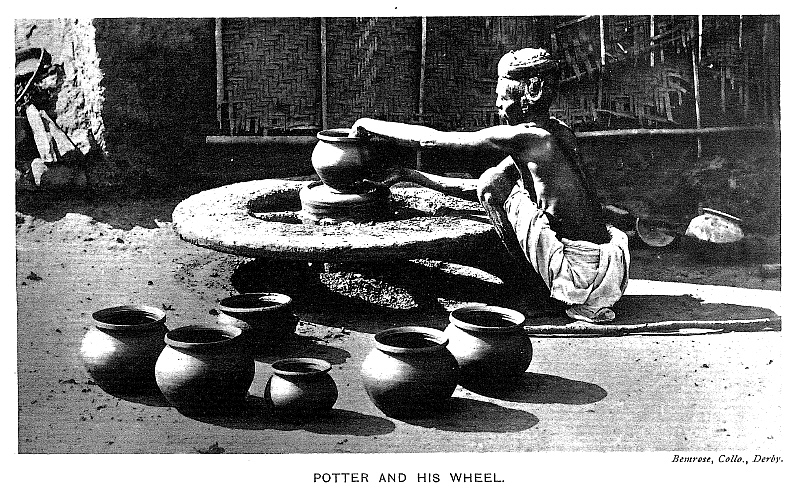

Abb.: Töpfer am Töpferrad, Zentralindien, um 1916

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 4. -- Nach S. 4.]

Abb.: Kusavan (Töpfer), Tamil Nadu, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 4. -- Nach S. 190.]

Abb.: Töpfer beim Ausklopfen eines Topfes, Tiruchchirappalli (திருச்சிராப்பள்ளி), Tamil Nadu, 2007

[Bildquelle: von Dilip Muralidaran. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/dilipm/364714358/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01. --Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Töpfer beim Schlagen von Schüsseln auf Matrize, Rajasthan, 2004

[Bildquelle: Dey. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/dey/1193026371/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01. --Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Hochzeitstöpfe, Tamil Nadu, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 6. -- Nach S. 18.]

Abb.: Topf-Trommel, Südindien, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 6. -- Nach S. 232.]

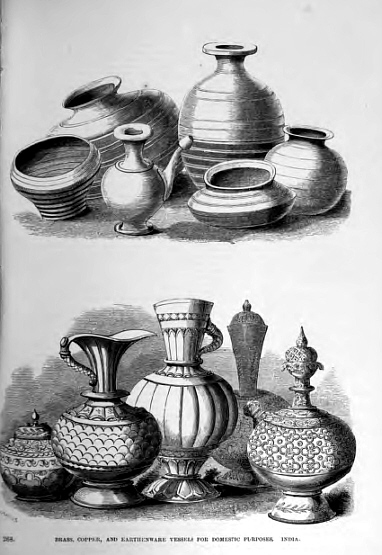

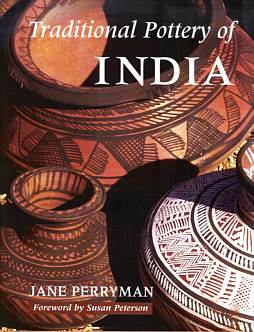

"POTTERY. TRUEST to nature, in the directness and simplicity of its forms, and their adaptation to use, and purest in art, of all its homely and sumptuary handicrafts is the pottery of India; the unglazed rude earthenware, red, brown, yellow, or grey, made in every village, and the historical glazed earthenware of Madura, Sindh, and the Panjab.

Unglazed pottery is made everywhere in India, and has been from before the time of Manu : and the forms of it shewn on ancient Buddhist and Hindu sculptures, and the ancient Buddhist paintings of Ajanta, are identical with those still everywhere thrown from the village hand-wheels. In the sculptures of Bhuvaneswar the form of the kalasa, or water jug, is treated with great taste as an architectural decoration, especially in its use as an elegant finial to the temple towers. In the same sculptures is seen the form of another water vessel, identical with the amriti, or "nectar" bottle, sold in the bazaars of Bengal.

It is impossible to attempt any enumeration of the places where unglazed pottery is made, for its manufacture is literally universal, and extended over the whole and to every part of India. Mr. Baden Powell, however, cites the following places in the Panjab as worthy of special mention for their unglazed earthenware: Amritsar, Cashmere, Dera Ghazi Khan, Dera Ismail Khan, Gugranwalla, Hazara, Hushiarpur, Jhelam, Kangra, Kohat, Lahore, Ludhiana, Montgomery, Rawalpindi, and Shahpur. I Bengal the village pottery of Sawan in Patna, of Bardwan, of Ferozepur in Dacca, and Dinajpur in Rajshahye are noted : and in [S. 388] Bombay that of Ahmedabad in Gujarat, and of Khanpur in the collectorate of Belgaum.

The principal varieties of Indian fancy pottery made purposely for exportation are the red earthenware pottery of Travancore and Hyderabad in the Deccan, the red glazed pottery of Dinapur, the black and silvery pottery of Azimghar in the North-Western Provinces, and Surrujgurrah in Bengal (Bhagalpur), and imitation bidri of Patna and Surat in Gujarat, the painted pottery of Kota in Rajputana, the gilt pottery of Amroha also in Rajputana, the glazed and unglazed pierced pottery of Madura, and the glazed pottery of Sindh and the Panjab. In all these varieties of Indian pottery an artistic effect is consciously sought to be produced.

The Azimghar pottery, like most of the art-work of the Benares district, and eastward, is generally feeble and rickety in form and insipid and meretricious in decoration, defects to which its fine black color, obtained by baking it with mustard oilseed cake, gives the greater prominence. The only tolerable example of it I have ever seen is the water-jug in the India Museum, which attracts, and in a way pleases, because of the strangeness of look given to it by the pair of horn-like handles. The silvery ornamentation is done by etching the pattern, after baking, on the surface, and rubbing into it an amalgam of mercury and tin ; thus producing the characteristic mawkish and forbidding effect, which, however, the unsophisticated potter of Azimghar does not attempt to mystify by calling it by any of those artful, advertising "cries" wherewith so much ado about nothing is sometimes made in English high art galleries. Very different is the glazed pottery of Sindh and the Panjab. The charms of this pottery are the simplicity of its shapes, the spontaneity, directness, and propriety of its ornamentation, and the beauty of its coloring. The first thing to be desired in pottery is beauty of form, that perfect symmetry and purity of form which is

"When unadorn'd, adorn'd the most."

[S. 389]

[...]

Also, never more than two or three colors are used, and when three colors are used, as a rule, two of them are [S. 390] merely lighter and darker shades of the same color.

[...]

The potter's art is of the highest antiquity in India, and the unglazed water vessels, made in every Hindu village, are still thrown from the wheel in the same antique forms represented on the ancient Buddhistic sculptures and paintings.

[...]

The only exception is the glazed pottery of Madura, and of Sindh and the Panjab, which alone of the fancy varieties can be classed as art pottery, and as such is of the highest excellence.

Plate 76 (b)The Madura pottery [Plate 76] is in the form generally of water bottles, with a globular bowl and long upright neck; the bowl being generally pierced so as to circulate the air round an inner porous bowl. The outer bowl and neck are rudely fretted all over by notches in the clay, and are glazed either daik green or a rich golden brown.

Plate 70.

Plate 71.

Plate 73.

Plate 74.

Plate 75.The glazed pottery of Sindh [Plates 70-75] is made principally at Hala, Hyderabad, Tatta, and Jerruck, and that of the Panjab at Lahore, Multan, Jang, Delhi, and elsewhere.1 The chief places for the manufacture of encaustic tiles are at Bulri and Saidpur in[S. 399] Sindh.

1 The master potters known to me by name are Jumu, son of Osman the Potter. Karachi ; Mahommed Azim, the Pathan, Karachi ; Messrs. Nur; Mahommecl, and Kadmil, Hyderabad ; Ruttu Wuleed Minghu, Hyderabad ; and Peranu, son of Jumu, Tatta. Mr. Kipling sends me the name of Mahommed Hashim at Multan.

[...]

It is found in the shape of drinking cups, and water bottles, jars, bowls, plates, and dishes of all shapes and sizes, and of tiles, pinnacles for the tops of domes, pierced windows, and other architectural accessories. In form, the bowls, and jars, and vases may be classified as egg-shaped, turband, melon, and onion-shaped, in the latter the point rising and widening out gracefully into the neck of the vase. They are glazed in turquoise, of the most perfect transparency, or in a [S. 400] rich dark purple, or dark green, or golden brown. Sometimes they are diapered all over by the pâte-sur-pâte method, with a conventional flower, the seventy or lotus, of a lighter color than the ground. Generally they are ornamented with the universal knop and flower pattern, in compartments formed all round the bowl, by spaces alternately left uncolored and glazed in color. Sometimes a wreath of the knop and flower pattern is simply painted round the bowl on a white ground [Plate 72].

Plate 72.[...]

It is a rare pleasure to the eye to see in the polished corner of a native room one of these large turquoise blue sweetmeat jars on a fine Kirman rug of minimum red ground, splashed with dark blue and yellow. But the sight of wonder is, when travelling over the plains of Persia or India, suddenly to come upon an encaustic-tiled mosque. It is colored all over in yellow, [S. 401]green, blue, and other hues; and as a distant view of it is caught at sunrise, its stately domes and glittering minarets seem made of purest gold, like glass, enamelled in azure and green, a fairy-like apparition of inexpressible grace and the most enchanting splendor.

In giving the following receipts of the different preparations used in enamelling Sindh and Panjab pottery, it is as well to say that they are of little practical value out of those countries. It will be noted that a great deal is thought, by the native manufacturers, to depend on the particular wood, or other fuel used, in the baking, which, if it really influences the result, makes all attempts at imitating local varieties of Indian pottery futile.

In the glazing and coloring two preparations are of essential importance, namely kanch, literally glass, and sikka, oxides of lead. In the Panjab the two kinds of kanch used are distinguished as Angrezi kanchi, "English glaze," and desi-kanchi, "country glaze."

Angrezi kanchi is made of sang-i-safed, a white quartzose rock 25 parts; sajji, or pure soda, 6 parts; sohaga telia, or pure borax, 3 parts ; and nausadar or sal ammoniac, 1 part. Each ingredient is finely powdered and sifted, mixed with a little water, and made up into white balls of the size of an orange. These are red-heated, and after cooling again, ground down and sifted. Then the material is put into a furnace until it melts, when clean-picked shora kalmi, or saltpetre, is stirred in. A foam appears on the surface, which is skimmed off and set aside for use. The desi-kanchi is similarly made, of quartzose rock and soda, or quartzose rock and borax, or siliceous sand and soda. A point is made of firing the furnace in which the kanch is melted with kikar, karir, or Capparis wood.

Four sikka, or oxides of lead, are known, namely, sikka safed, white oxide, the basis of most of the blues, greens, and greys used ; sikka zard, the basis of the yellows ; sikka sharbati, litharge ; and sikka lal, red oxide.

[S. 402] Sikka safed is made by reducing the lead with half its weight of tin ; sikka zard by reducing the lead with a quarter of its weight of tin ; sikka sharbati by reducing with zinc instead of tin ; and sikka lal in the same way, oxidising the lead until red. The furnace is always heated in preparing these oxides with jhand, or Prosopis wood. The white glaze is made with one part of kanch and one part sikka safed (white oxide) well ground, sifted, and mixed, put into the kanch furnace, and stirred with a ladle. When melted, borax in the proportion of two chittaks to the ser (1 chittak = 1/16 ser ; 1 ser = 2 2/5 lbs. avoirdupois) is added. If the mixture blackens, a small quantity of shora kalmi, or saltpetre, is thrown in. When all is ready, the mixture is thrown into cold water, which splits it into splinters, which are collected and kept for use. All the blues are prepared by mixing either copper or manganese, or cobalt, in various proportions with the above white glaze. The glaze and coloring matter are ground together to an impalpable powder ready for application to the vessel.

The following are the blue colors used :

Firoza, turquoise blue: 1 ser of glaze, and 1 chittak of chhiltamba, or calcined copper.

Firozi-abi, pale turquoise: 1 ser of glaze, and 1/24 of calcined copper.

Nila, indigo blue: 1 ser of glaze, and 4 chittaks of reta, or zaffre (cobalt).

Asmani, sky blue: 1 ser of glaze, and 1½ chittak of zaffre.

Halka-abi, pale sky blue: 1 ser of glaze, and 1 chittak of zaffre.

Kasni, pink or lilac: 1 ser of glaze, and 1 chittak of anjani, or oxide of manganese.

Sosni, violet: 1 ser of glaze, and 1 chittak of mixed manganese and zaffre.

Uda, purple or puce: 1 ser of glaze, and 2 chittak of manganese.

Khaki, grey: 1 ser of glaze, and 1½ chittak of mixed manganese and zaffre.

The rita or zafifre is the black oxide of cobalt found all over Central and Southern India, which has been roasted and powdered, [S. 403] mixed with a little powdered flint. Another mode of preparing the nila, or indigo blue glaze, for use by itself, is to take:

Powdered flint: 4 parts.

Borax: 24

Red oxide of lead: 12

White quartzose rock: 7

Soda: 5

Zinc: 5

Zaffre: 5

All are burnt together in the kanch furnace as before described.

The yellow glaze used as the basis of the greens is made of sikka zard, white oxide 1 ser, and sang safed, a white quartzose rock, or millstone, or burnt and powdered flint, 4 chittaks, to which, when fused, 1 chittak of borax is added.

The green colors produced are :

Zamrudi, deep green: 1 ser of glaze, and 3 chittaks of chhil tamba, or calcined copper.

Sabz, full green: 1 ser of glaze, and 1 chittak of copper.

Pistaki, or Pistachio (bright) green: 1 ser of glaze, and 1½ chittak of copper.

Dhani, or Paddy (young shoots of rice), green: 1 ser of glaze, and 1/125 chittak of copper.

Another green is produced by burning one ser of copper filings with nimak shor, or sulphate of soda.

The colors, after being reduced to powder, are painted on with gum, or gluten. The vessel to receive them is first carefully smoothed over and cleaned, and, as the pottery clay is red when burnt, it is next painted all over with a soapy, whitish engobe prepared with white clay and borax and Acacia and Conocarpus gums called kharya mutti. The powdered colors are ground up with a mixture or nishasta, or gluten and water, called mawa until the proper consistence is obtained, when they are [S. 404] painted on with a brush. The vessels are then carefully dried and baked in a furnace heated with ber, or Zizyphus, or, in some cases, Capparis wood. The ornamental designs are either painted on off-hand, or a pattern is pricked out on paper, which is laid on the vessel and dusted with the powdered color along the prickings, thus giving a dotted outline of the design, which enables the potter to paint it in with all the greater freedom and dash. It is the vigorous drawing, and free, impulsive painting of this pottery which are among its attractions. The rapidity and accuracy of the whole operation is a constant temptation to the inexperienced bystander to try a hand at it himself. You feel the same temptation in looking on at any native artificer at his work. His artifice appears to be so easy, and his tools are so simple, that you think you could do all he is doing quite as well yourself. You sit down and try. You fail, but will not be beaten, arid practise at it for days with all your English energy, and then at last comprehend that the patient Hindu handicraftsman's dexterity is a second nature, developed from father to son, working for generations at the same processes and manipulations.

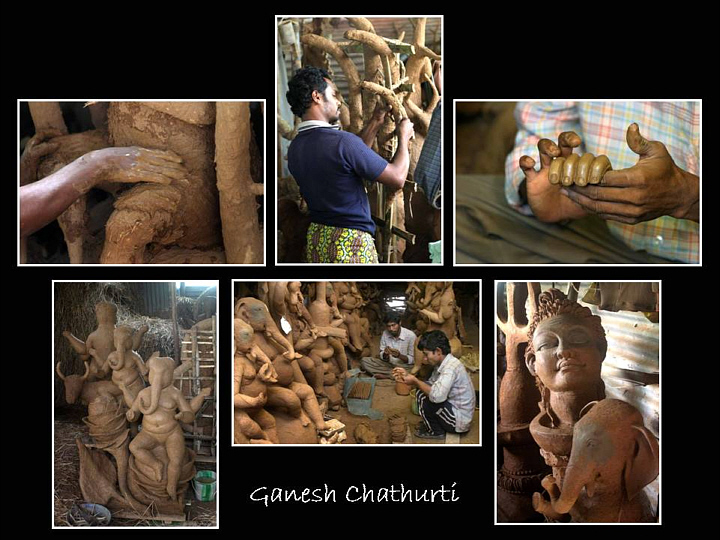

The great skill of the Indian village potter may be judged also from the size of the vessels he sometimes throws from his wheel, and afterwards succeeds in baking. At Ahmedabad and Baroda, and throughout the fertile pulse and cereal-growing plains of Gujarat, earthen jars, for storing grain, are baked, often five feet high ; and on the banks of the Dol Samudra, in the Dacca division of the Bengal Presidency, immense earthen jars are made of nearly a ton in cubic capacity. The clay figures of Karttikeya, the Indian Mars, made for his annual festival by the potters of Bengal, are often twenty-seven feet in height.

The Indian potter's wheel is of the simplest and rudest kind. It is a horizontal fly-wheel, two or three feet in diameter, loaded heavily with clay around the rim, and put in motion by the hand ; and once set spinning, it revolves for five or seven minutes with a perfectly steady and true motion. The clay to be moulded is [S. 405] heaped on the centre of the wheel, and the potter squats down on the ground before it. A few vigorous turns and away spins the wheel, round and round, and still and silent as a "sleeping" top, while at once the shapeless heap of clay begins to grow under the potter's hand into all sorts of faultless forms of archaic fictile art, which are carried off to be dried and baked as fast as they are thrown from the wheel. Any polishing is done by rubbing the baked jars and pots with a pebble. There is an immense demand for these water-jars, cooking-pots, and earthen frying-pans and dishes. The Hindus have a religious prejudice against using an earthen vessel twice, and generally it is broken after the first pollution, and hence the demand for common earthenware in all Hindu families. There is an immense demand also for painted clay idols, which also are thrown away every day after being worshipped ; and thus the potter, in virtue of his calling, is an hereditary officer in every Indian village. In the Dakhan, the potter's field is just outside the village. Near the wheel is a heap of clay, and before it rise two or three stacks of pots and pans, while the verandah of his hut is filled with the smaller wares and painted images of the gods and epic heroes of the Rayamana and Mahabharata. He has to supply the entire village community with pitchers and cooking pans, and jars for storing grain and spices and salt, and to furnish travellers with any of these vessels they may require. Also, when the new corn begins to sprout, he has to take a water-jar to each field for the use of those engaged in watching the crop. But he is allowed to make bricks and tiles also, and for these he is paid, exclusively of his fees, which amount to between 4 l. and 5 l. a year. Altogether he earns between 10 l. and 12 l. a year, and is passing rich with it. He enjoys, beside, the dignity of certain ceremonial and honorific offices. He bangs the big drum, and chants the hymns in honour of Jami, an incarnation of the great goddess Bhavani, at marriages ; and at the dowra, or village harvest home festivals, he prepares the barbat [S. 406] or mutton stew. He is, in truth, one of the most useful and respected members of the community, and in the happy religious organisation of Hindu village life there is no man happier than the hereditary potter, or kumbar.

We cannot overlook this serenity and dignity of his life if we would rightly understand the Indian handicraftsman's work. He knows nothing of the desperate struggle for existence which oppresses the life and crushes the very soul out of the English working man. He has his assured place, inherited from father to son for a hundred generations, in the national church and state organisation ; while nature provides him with everything to his hand, but the little food and less clothing he needs, and the simple tools of the trade.

[...]

[S. 416]

The Bombay School of Art Pottery we owe chiefly to the exertions of Mr. George Terry, the enthusiastic superintendent of the school, who has a quick sympathy with native art. He has introduced some of the best potters from Sindh, and the work Mr. Terry's pupils turn out in the yellow glaze in Bombay is now with difficulty distinguishable from the indigenous pottery of Sindh. It is only to be identified by its greater finish, which is a fault. The School of Art green and blue pottery always betrays its origin by some inherent defect in the glaze or clay used. Mr. Terry has also developed two original varieties of glazed pottery at Bombay, the designs in one being adapted with great knowledge and taste from the Ajanta cave paintings, and the popular mythological paintings of the Bombay bazaars ; while in the other they are of his, or his pupils' own inspiration, and derived from leaf and flower forms. Examples of all these varieties of the [S. 417] Bombay School of Art Pottery, of the imitation Sindh and the Terry ware, have been put together in a separate case in the India Museum. The glazed pottery which comes from Bombay of Sindhian designs on Chinese and Japanese jam and pickle pots are a violation of everything like artistic and historical consistency in art, and if they are not ignorant productions of the pupils of the School of Art they are a most cruel slander on them."

[Quelle: Birdwood, George C. M. (George Christopher Molesworth) <1832-1917>: The industrial arts of India. -- London : Chapman and Hall. -- 20 cm. -- (South Kensington Museum art handbooks). -- Vol. 2. -- 1884. -- S. 387 - 417. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/industrialartsof00birduoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-24. -- "Not in copyright".]

Herstellung einer Lehmfigur Gaṇeśas für Gaṇeś Caturthī (गणेश चतुर्थी): Gerüst

aus Stroh

[Bildquelle: babasteve. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/babasteve/1395177994/. -- Zugriff am

2008-04-01. --

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Herstellung einer Lehmfigur Gaṇeśas für Gaṇeś Caturthī (गणेश चतुर्थी): Auftragen

von Lehm und Modellieren

[Bildquelle: babasteve. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/babasteve/1395904369/in/set-781175/. -- Zugriff

am 2008-04-01. --

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Herstellung einer Lehmfigur Gaṇeśas für Ganesh Chaturthi (गणेश चतुर्थी):

Bemalen der getrockneten Lehmfigur

[Bildquelle: babasteve. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/babasteve/1399838397/in/set-781175/. -- Zugriff

am 2008-04-01. --

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Gaṇeśas für Ganesh Chaturthi (गणेश चतुर्थी)

[Bildquelle: babasteve. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/babasteve/1387102756/in/set-781175/. -- Zugriff

am 2008-04-01. --

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Lehmfiguren für Holi-Fest (होली)

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 2. -- Nach S. 126.]

Abb.: Lehmfiguren, Nīlgiri (நீலகிரி), um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 7. -- Nach S. 136.]

"Clay Figures.

Figures in clay, painted and dressed up in muslins, silks, and spangles, are admirably modelled at Kishnaghur, Calcutta Lucknow, and Poona. Fruit is also modelled at Gokak, and other villages in the Belgaum Collectorate of the Bombay Presidency, and at Agra and Lucknow. The Lucknow models of fruit are so true to nature as to defy detection until handled. The clay figures of Lucknow are also most faithful and characteristic representations of the different races and tribes of Oudh ; and highly creditable to the technical knowledge and taste of the artists. They are sold on the spot at the rate of four shillings the dozen. Wall brackets, vases, clock-cases, and other articles are also manufactured out of the tenacious clay at the bottom of the tanks in Lucknow ; but they are in a very debased style, being modelled after the Italian work which is to be found all over Lucknow, the old Oudh Nawabs having largely employed Italian sculptors in the building and decoration of their gardens and palaces.

It is very surprising that a people who possess, as their ivory and stone carvings and clay figures incontestably prove, so great a facility in the appreciation and delineation of natural forms should have failed to develop the art of figure sculpture. Nowhere does their figure sculpture shew the inspiration of true art. They seem to have no feeling for it They only attempt a literal transcript of the human form, and of the forms of animals, for the purpose of making toys and curiosities, almost exclusively for sale to English people. Otherwise they use these sculptured forms only in architecture, and their tendency is to subordinate them strictly to the architecture. The treatment of them rapidly becomes decorative and conventional. Their very gods are distinguished only by their attributes and symbolical monstrosities [S. 303] of body, and never by any expression of individual and personal character."

[Quelle: Birdwood, George C. M. (George Christopher Molesworth) <1832-1917>: The industrial arts of India. -- London : Chapman and Hall. -- 20 cm. -- (South Kensington Museum art handbooks). -- Vol. 2. -- 1884. -- S. 302f. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/industrialartsof00birduoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-24. -- "Not in copyright".]

Abb.: Steinbildhauer für Kleinfiguren, Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: w3p706. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/w3p706/475394438/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Steinhauer, Tirupati (తిరుపతి, திருப்பதி), Andhra Pradesh, 2004

[Bildquelle: isado. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/isadocafe/13777732/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01.

--

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

"Carved Stone. The agate vases of Baroach and Cambay have been famous under the name of Murrhine vases from the time of Pliny. The best carnelians and agates are found at Ratanpur near Baroach, and are taken to Cambay to be worked into cups, saucers, knife-handles, paperweights, beads, bangles, and other ornaments.

Plate 63.Animals are carved in black chlorite at Gaya in the Patna division of Bengal ; and in white marble and reddish sandstone (Plate 63) at Ajmir and other places in Rajputana ; and we find the same truth of representation in these stone carvings as in the best ivory carvings of Amritsar, Benares, and Travancore.

In Rajputana also idols are largely carved in white marble, and brilliantly colored in red, green, yellow, and blue paint and gold. Jade is still carved in Cashmere. At Fattehpur Sikri models in soapstone are made of the celebrated Mahommedan ruins of that city ; and it is also carved into ornamental dishes, inkstands, and other objects. Soapstone ornaments are also made at Gohari in the North-Western Provinces. In Singbhum and Manbhum, in the Chota-Nagpur division of Bengal, there are large masses of soapstone, which the people have for ages worked into platters and cups. On the Nilgiri estate close to Balasore in Orissa, a black chlorite is obtained which is also worked into cups and dishes. Soapstone and potstone ware are manufactured at Tambulghata, and at Kanheri and Pendri, in the Central Provinces. At Nagpur, where in former times the art of stone and wood carving reached a high degree of perfection, there are still many excellent stone carvers among the masons. The art has to a certain extent fallen into disuse, but efforts are being made to revive it. The Chanda masons also are very skilful in carving stone. The stone carvers of Katch and Kathiwar are celebrated all over Western India. [S. 299]

The early Mahommedan architecture of Ahmedabad has been remarkably influenced by these clever Hindu masons. Afterwards the taste of their Mahommedan masters reacted on their own work, as is strikingly seen in the Jaina temples of Palitana and other parts of Gujarat. At Malwan and Patgaum, in the Ratnagiri Collectorate of the Bombay Presidency, a soft slatey stone is carved into cups after the schistose models imported into Western India from Persia. The masons of Sargiddapanam in Nellore (Madras) are noted for their stone sculpture on the native towers called Galegopurams ; and those of Buchereddipalem for their sculpture on the granite pillars of the local temples. The masons also of Udayagiri in this district are skilled in stone carving. The masons of Tumkur in Mysore are specially noted for the stone idols they carve. Stone jugs are largely manufactured at Kavaledurga in Mysore.

Captain Cole, R.E., who has paid special attention to the ancient stone sculptures of India, in his Catalogue to the Objects of Indian Art exhibited in the South Kensington Museum, 1874, classifies them in the two divisions :

Statues and bas-reliefs.

Decorative sculpture for architectural purposes.

Under the head of statues and bas-reliefs he enumerates :

The Buddhistic figure sculptures of the Asoka edict pillars, and of the Sanchi and Amaravati topes ; and the Graeco-Buddhistic remains in the Peshawur district.

The Jaina sculptures, of the twenty-four hierarchs of that sect in Rajputana, at Gwalior, at Benares, and Mahoba, and in Bandelkhand.

The Brahmanical bas-reliefs of Pandrethan and Marttand in Cashmere, at Bindraband, at Eran and Pathari near Bhilsa, at Khajuraho in Bandelkhand, and at Puri in Kattack.

The Mahommedan sculptures, consisting of the two carved elephants which formerly stood outside the gates of Delhi, and similar statues at Fattehpur Sikri and Ahmedabad.

[S. 300] The best examples of decorative sculptures are :

The Buddhist, of the Sarnath, Sanchi, and Amravati topes, and the caves of Ellora, Kanheri, and Ajanta.

The Jaina, of the temples of Mount Abu, at Khajuraho, the ancient capital of Bandelkhand, at Sonari, and in the fort at Gwalior.

The Brahmanical at Avantipur in Cashmere, of the temples at Benares, and at Bindraband, at the Kutub at Delhi, of Tirumulla Nayak's (Trimul Naik's) Choultri at Madura, and the Kylas at Ellora.

- The Mahommedan, namely :

The Pathan, decorative carving of Kutub-ud-din's gateway at Delhi, A.D. 1193 ; the Kutub Minar, at Delhi, A.D. 1200 ; and the palace at Ahmedabad.

The Mogol, of the palaces at Fattehpur Sikri, and the Taj Mahal at Agra."

[Quelle: Birdwood, George C. M. (George Christopher Molesworth) <1832-1917>: The industrial arts of India. -- London : Chapman and Hall. -- 20 cm. -- (South Kensington Museum art handbooks). -- Vol. 2. -- 1884. -- S. 298 - 301. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/industrialartsof00birduoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-24. -- "Not in copyright".]

Abb.: Schmiede, Gujarat, 2008

[Bildquelle: owenstache. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/owen-pics/2331791031/. -- Zugriff am

2008-04-01. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

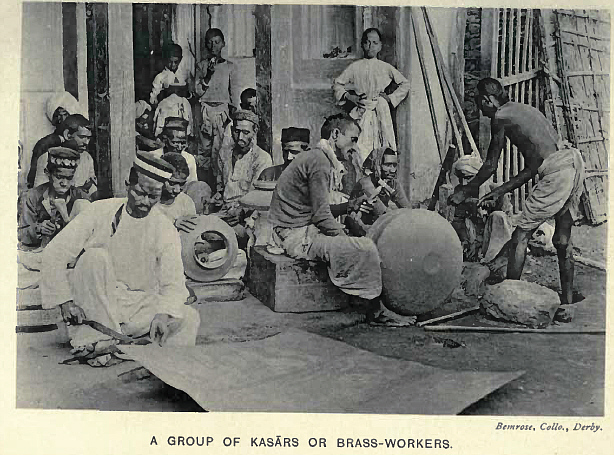

Abb.: Kasārs (Messing- und Kupferarbeiter), Zentralindien, um 1916

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 3. -- Nach S. 370.]

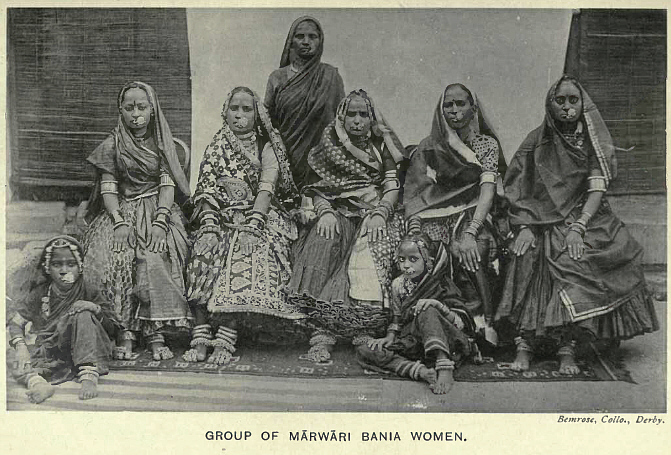

Abb.: Bania-Frauen, Mārwār (मारवाड़), Rajasthan, um 1916

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 2. -- Nach S. 112]

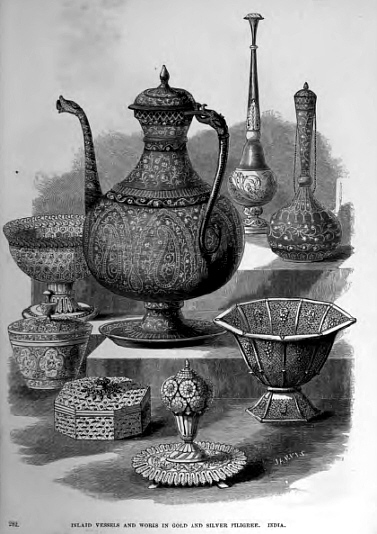

Abb.: Männerschmuck eines Palian, Tamil Nadu, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 5. -- Nach S. 468.]

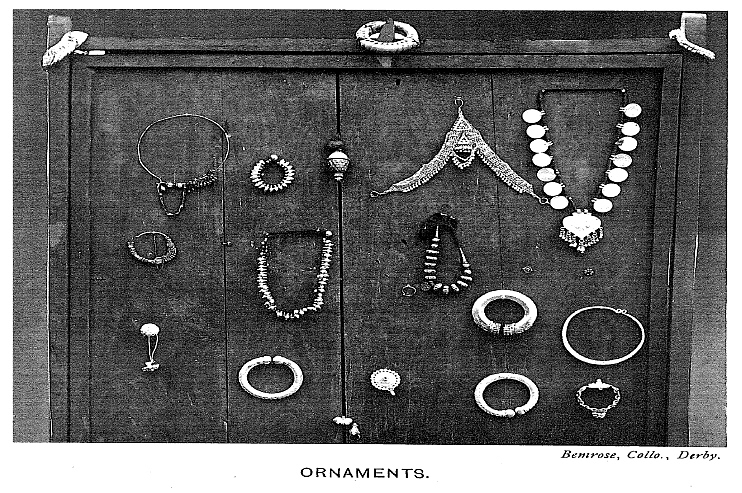

Abb.: Schmuck, Zentralindien, um 1916

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 4. -- Nach S. 524.]

Abb.: Schmuck von Nāttukottai Chettis (Geldverleiher), Tamil Nadu, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 5. -- Nach S. 264.]

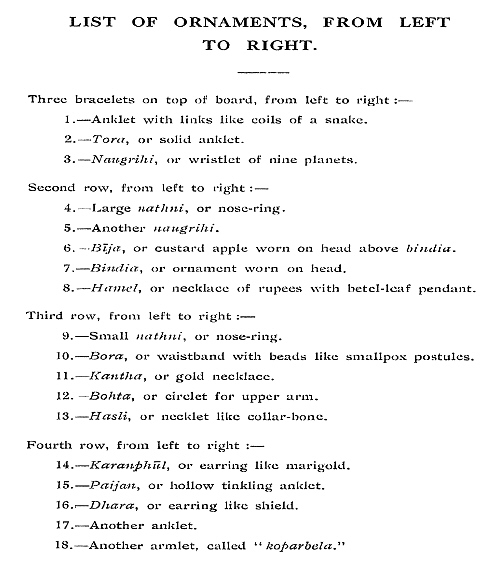

Abb.: Gold- und Silberwaren aus Indien, ausgestellt bei der Great Exhibition of

the Works of Industry of all Nations, London 1851

[Bildquelle: Official descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the Great exhibition of the works of industry of all nations, 1851 ... -- London : Spicer, 1851. -- Vol IV: Colonies - foreign states. Division I.]

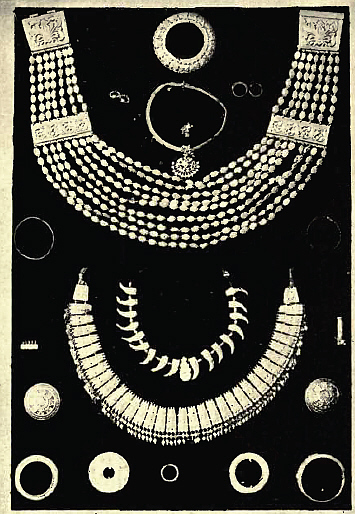

Abb.: Schmuck, wie er von Nāyar-Frauen (നായര്), Kerala, getragen wurde, um

1901

[Bildquelle: Fawcett, F.: Nāyars of Malabar. -- Madras : Government Press, 1915. -- (Bulletin / Madras Government Museum ; Vol. III, No.3. -- Pl. X.]

"JEWELRY. [S. 243] EVEN a greater variety of style is seen in Indian jewelry than in Indian arms. Mr. W. G. S. V. FitzGerald sent to the Annual International Exhibition of 1872, a collection of the grass ornaments worn by the wild Thakurs and Katharis of Matheran, and the Western Ghats of Bombay, which had been made by Dr. T. Y. Smith, the accomplished Superintendent of that Hill Station ; and by the side of these grass collars, necklaces, bracelets, anklets, and girdles, were exhibited also examples of the gold jewelry of thick gold wire, twisted into the girdles, bracelets, anklets, necklaces, and collars, worn all over India, and which are fashioned in gold exactly as the Matheran ornaments are fashioned in grass. [...] Necklaces of gold are also worn in Western India which are identical in character with the Matheran necklaces of chipped and knotted grass, which indicate the origin also of the peculiar Burmese necklaces, formed of tubular beads of ruddy gold strung together, and pendent from a chain which goes round the neck, from which [S. 244] the strings of tubular beads of gold hang down in front, like a golden veil. The details in these Burmese necklaces are often variously modified, the gold being wrought into flowers, or replaced by strings of pearl and gems, until all trace of their suggested origin is lost. By the side of Mr. FitzGerald's collection, I exhibited the "fig-leaf" worn by the women in the wilder parts of India, and which in many places is their only clothing. First was shewn the actual "fig-leaf," the leaf of the sacred fig, or pipal, Ficus religiosa ; next a literal transcript of it in silver, and then the more or less conventionalised forms of it, but all keeping the heart-shape of the leaf; the surface ornamentation in these conventionalised silver leaves being generally a representation of the pipal tree itself, or some other tree, or tree-like form, suggesting the "Tree of Life" of the Hindu Paradise on Mount Meru. These silver leaves are suspended from the waist, sometimes, like the actual leaf, by a simple thread, but generally by a girdle of twisted silver with a serpent's head where it fastens in front; [...] The forms of the champaca (Michelia Champaca) bud, and of the flowers of the babul (Acacia arabica) and seventi (Chrysanthemum species), the name of which is familiar in England through the story of "Brave Seventi Bhai," "the Daisy Lady," in Miss Frere's Old Deccan Days, are commonly used by Indian jewellers for necklaces and hairpins, as well as of the fruit of the anola or aonla (Phyllanthus emblica9 and ambgul (Elaeagnus Koluga), and mango, or amb (Mangifera indica). The bell-shaped earring, with smaller bells hanging within it, is derived from the flower of the sacred lotus : and the cone-shaped earrings of Cashmere, in ruddy gold, represent the lotus flower-bed. [...] [S. 245]

As primitive probably as the twisted gold wire forms of Indian jewelry, is the chopped gold form of jewelry worn also throughout India, the art of which is carried to the highest perfection at Ahmedabad and Surat in Western India. It is indeed worn chiefly by the people of Gujarat. It is made of chopped pieces, like jujubes, of the purest gold, flat, or in cubes, and, by removal of the angles, octahedrons, strung on red silk. It is the finest archaic jewelry in India. The nail-head earrings are identical with those represented on Assyrian sculptures. It is generally in solid gold, for people in India hoard their money in the shape of jewelry; but it is also made hollow to perfection at Surat, the flat pieces, and cubes, and octahedrons being filled with lac or dammar.

The beaten silver jewelry of the Gonds, and other wild tribes of the plains of India, and valleys of the inner Himalayas, is also very primitive in character. The singular brooch worn by the women of Ladak (v. Miss Gordon Cumming's From the Hebrides to the Himalayas, 1876, p. 219), is identical with one found among Celtic remains in Ireland and elsewhere. It is formed of a flat and hammered silver band, hooped in the centre, with the ends curled inward on the hoop ; and this is too artificial a shape to have arisen independently in India and Europe, and must have travelled westward with the Celtic emigration from the East. Its form is evidently derived from the symbols of serpent and phallic worship.

The waist-belt of gold or silver, or precious stones, which is worn in India to gird up the dhoti, or cloth worn about the legs, recalls the Roman cingulum ; [...] [S. 246] in India, at the ceremony of investiture with the sacrificial thread, an identical ornament, a hollow hemisphere of gold, hung from a yellow cotton thread or chain of gold, is taken from the boy's neck, and the sacred cord, the symbol of his manhood, is put on him.

The nava-ratna or nao-ratan, an amulet or talisman composed of "nine gems," generally the Coral, Topaz, Sapphire, Ruby, flat Diamond, cut Diamond, Emerald, Hyacinth, and Carbuncle [...]. This ancient ornament gave its name as a collective epithet to the "nine-gems" or sages of the Court of Vikramaditya, B.C. 56. In books the nine gems of the amulet are said to be pearl, ruby, topaz, diamond,, emerald, lapis- lazuli, coral-sapphire, and a stone, not identified, called gomeda. The tri-ratna, is the "triple-gemmed" "Alpha and Omega" jewel of the Buddhists, symbolical of Buddha, the Law, and the Church.

The jeweller's and goldsmith's art in India is indeed of the highest antiquity, and the forms of Indian jewelry as well as of gold and silver plate, and the chasings and embossments decorating them, have come down in an unbroken tradition from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. [...] [S. 247] But the earliest records, the national epics, and ancient sculptures and paintings, represent the Hindu forms of Indian jewelry, and gold and silver plate, and common pottery and musical instruments, and describe them, exactly as we have them now.

[...]

[249]