Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858

14. Quellen auf Arabisch, Persisch und in Turksprachen

2. Zum Beispiel: Kūfī, ʻAlī ibn Ḥāmid <13. Jhdt. A.D:>: The Chachnamah <Auszug>

hrsg. von Alois Payer

Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. 14. Quellen auf Arabisch, Persisch und in Turksprachen. 2. Zum Beispiel: Kūfī, ʻAlī ibn Ḥāmid <13. Jhdt. A.D:>: The Chachnamah <Auszug>. Fassung vom 2008-05-15. http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen142.htm

Erstmals publiziert als:

Kūfī, ʻAlī ibn Ḥāmid <13. Jhdt. A.D:>: The Chachnamah, an ancient history of Sind giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. / ranslated from the Persian by Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg [1853 - 1929]. Karachi : The Commissioner’s Press, 1900. S. Online: http://persian.packhum.org/persian/main. Zugriff am 2008-05-15.

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2008-05-15

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Public domain.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

"Chach (632-671) is the name of the Brahmin Chamberlain and Secretary to Rai Sahasi the Second, of the Rai Dynasty who succeeded him to the throne of Sindh. The history of Chach is related in the Chach Nama as part of the history of Sind. Rise to Power

Chach was a Brahmin who rose to a position of influence under the Rai Sahasi of the Rai Dynasty of Sindh as both Chamberlain and Secretary. Rana Maharath, the King of Chittor, who was the brother Rai Sahasi then claimed the throne and attacked Chach but the Rana was killed by strategem, in the war in 622.

Later he expanded his rule subduing neighbouring Buddhist regions across the Indus River culminating in a battle at Brahmanabad [= Mansura منصورہ]. He stayed there for a year cementing his control by various means such as:

- Marrying the widow of the local king Agham

- Marrying his niece to Agham's son Sarhand

- Taking hostages

- Prohibiting the Jats and Luhanahs tribes from carrying weapons.

He further place upon the Jats and Luhanah restrictions such as:

- Forbidding them riding horses with saddles

- Forbidding them from wearing silk or velvet

- Forbidding them from wearing headgear or footwear

- Forcing them to wear black or red scarves

From there he then marched into Sassanid territory the town of Armanbelah, and through Turan to Kandahar from where he exacted tribute before returning.

In the 35th year of the reign of the Rai Chach, the Chach Nama reports the repulsion of a solitary Arab incursion. The force that arrived was ont that had pressed on from its campaign of the conquest of Bahrain launched in 632 AD under Mughaira bin A's, who died in this battle at Debal.

[...]

References

- Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg: The Chachnamah, An Ancient History of Sind, Giving the Hindu period down to the Arab Conquest. Translated by from the Persian by, Commissioners Press 1900[1]

- Thakur Deshraj: Jat Itihas, Delhi, 1934

- Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 90-04-09249-8

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chach_of_Alor. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-15]

Chach comes to the town of Brahmanabad and fights with Agham Luhanah.

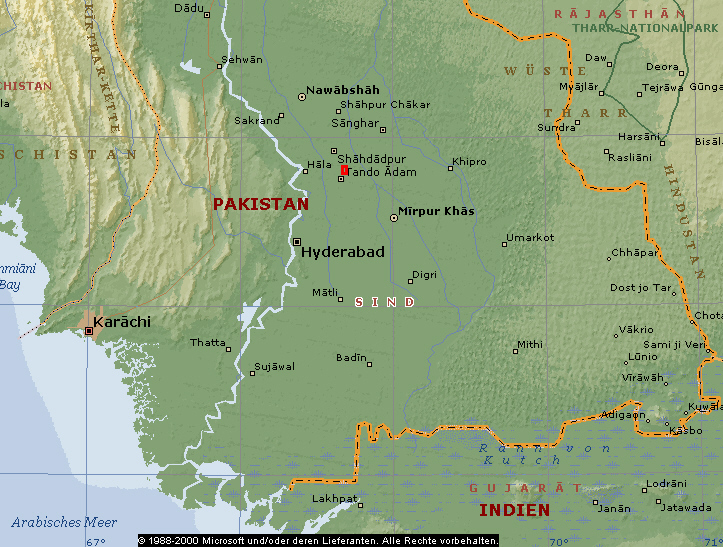

Abb.: Ungefähre Lage von Brahmanabad (19 km südöstlich von Shādādpur)

(©MS Encarta)

Then Rai Chach marched against Agham Lūhānah. Agham had gone from Brahmanabad on a tour in his territories. When he heard of Chach's coming, he returned to Brahmanabad, and began to collect soldiers and arms. When Rāi Chach arrived at Brahmanabad, Agham, ready for battle, came forth to meet him. After several renowned warriors were killed on both sides, Agham's army was put to flight, and he betook himself to the fort. Chach laid siege to it. For a period of one year this warfare went on between them. During that period the king of Hindustān, that is, Kanūj, was Sayār (or Satbār) son of Rāil Rāi (or Rāsal Rāi). Agham sent letters to him, applying for assistance. But before the reply came, Agham died, and his son succeeded him. Agham had a monkish friend, whose name was Samanī Budhgui (or Budh Rakhū), that is, one protected by Budha. He was supposed to bear a charmed life. He owned an idolhouse or temple, which was called Budh Nawwihār. It contained several idols. He was the chief monk of the place, and was well known for his devotion and piety, and all the people of that part of the country obeyed him. Agham professed his faith, and had taken him as his spiritual guide.

When Agham betook himself to the fort, the Samanī cooperated with him, but did not join in the fight. He was busy reading his books in his temple. When Prince Agham died, and his son was established in the government of the country, the Samanī became anxious and afraid lest the principalities, property and estates should pass away from his (the Samanī's) hands. In that perplexity, he consulted his books in order to ascertain the decree of fate, and he learnt that the kingdom was destined to fall into the hands of Chach, whether he himself was favourably inclined towards Chach or not. Agham's son (eventually) was sore pressed, and his army withdrew from the fight, and the fort fell into the bands of Chach, who kept a strong hold on it.

When Chach had come to know that Agham and his son had a compact with the Samanī, and that it was owing to his sorcery, enchantments, magic and counsels, that the war had been prolonged for a year, he had sworn: "If I succeed in taking this fort, I shall seize the Samanī, take off his skin, give it to lowcaste people to cover drums with it and to beat them till it was torn to pieces." When the Samanī had received information of this oath, he had laughed and said: "It will never be within the power of Chach to destroy me" When, after a time, the garrison in the fort of Brahmanabad, after battling hard and losing a large number of men, stopped fighting, sued for peace and asked for quarter, peace was made through the intervention of chiefs and heads of tribes between the two parties, and the fort was given up to Chach. Chach entered it and told them: "If you wish to go away, no living creature will oppose or prevent you; but if you make up your minds to stay here, then stay by all means." When Agham's son and dependents found him favourably inclined towards them, they preferred dwelling there. Chach remained in the town for some time in order to ascertain their disposition.

(During his stay at Brahmanabad), Chach sent for the mother of Sarhand (Agham's widow). He made her his own wife, and gave the hand of the daughter of his nephew Dahiyah (or Dharsiah) to Agham's son, and bestowed many-coloured robes on him. He remained there for one year, and appointed officers to collect Government dues, and brought the chiefs of those parts into complete subjection to himself. He then enquired where that sorcerer Samanī was, in order to see him. He was informed that he was a monk and lived with other monks. "He is," it was said, "one of the philosophers of Hind, and is the keeper of the Nawwihar temple. He is considered by the Samanīs as having attained sublimity and perfection. In magic and enchantments, he is so clever that he has subdued a world of men and made them submit to his will. By means of his talismans, he can provide himself with all he wants. He has for many days cooperated with Sarhand, owing to his friendship with his father; and it was by his encouragement and support that the forces of Brahmanabad carried on such an obstinate and protracted war."

Chach then called all his armed men, and gave them the following instructions:—"I shall converse with him (the Samanī). (But) when I have done speaking and look towards you, you should draw your swords and sever his head from his body." He then came to Budh Kanwibar and repaired to him. He found him sitting on a chair busily engaged in prayers, and with some hard clay in his hands with which he was making idols. He fixed a sort of seal on the idol, and the image of Budh appeared on it. The idol being now complete, he placed it on one side. Chach stood above him, but the Samanī paid him no attention. After some time, when he finished all his idols, he turned up his head and said: "The son of the ascetic Selāij is come!" "Even so, O priestly Samanī," answered Chach. "What business has brought you here?" asked the Samanī. "I came to know of your fidelity," replied Chach, "and so I came to see you." "Come down," said the monk. Chach came down. The Samanī spread a handful of straw and made Chach sit on it. Then he asked him, "O Chach, what do you want?" Chach answered, "I want you to become my friend and to come back to the fort of Brahmanabad, so that I may put you in charge of a high office, and entrust you with important affairs and responsible duties. You will be there with Sarhand, and you may cooperate with him by giving him (the benefit of) your counsels and your judgment." The monk said "I have no need of your kingdom. I do not feel inclined to have any civil employment, and I do not wish to have anything to do with worldly affairs." "Why did you leave the fort of Brahmanabad?" asked Chach. "When Agham Lūhānah died," said the monk, "and this boy, his son, gave way to grief, owing to the loss of his father, I admonished him to have patience, and I have been praying to God most sincerely that he may bring about peace and friendship between both the parties." "For me," continued the Samanī, "the service of Budh and the seeking of salvation in the next world are better than all worldly employments. As, however, you are the sovereign of this kingdom, I will at your supreme command shift to the vicinity of the fort, although I fear that the people dwelling in the fort would cause injury and mischief to the sown fields of Budh. Today, Chach is a great and wealthy personage." Chach said: "The worship of Budh is an excellent thing, and it is right to hold it in honour. But if you want anything, or if you have any request to make, speak that I may at once grant it and thereby secure (for myself) happiness and honour." The monk (nāsik) said: "I do not want any worldly thing, nor have I any worldly request to make. May God graciously incline you to the affairs of the next world." Chach said: "That is exactly my request, and I wish to do a deed which should have spiritual advancement and salvation as its reward. Tell me of it, and I will render my assistance and be your helpmate." The Samanī said: "As you are determined to do some charitable act and add (to your) good deeds, (know that) the temple of Budh Nawwhār have is an ancient religious institution. For some time past, owing to the vicissitudes of time, some parts of the structure have suffered injury. It should, therefore, be built anew, and you should spend your own funds in laying a fresh foundation. In this matter alone can I implore your help." Chach said: "I am highly obliged to you."