Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis

1858

14. Quellen auf Arabisch, Persisch und in Turksprachen

8. Zum Beispiel: ʻAbd

al-Qādir ibn Mulūk

Shāh, Badāʾūnī

<1540 - >: Muntaḵhab ut-tawāriḵh

<Auszüge>

hrsg. von Alois Payer

mailto:payer@payer.de

Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur

indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 14. Quellen auf Arabisch, Persisch und in Turksprachen.

-- 8. Zum Beispiel: ʻAbd al-Qādir ibn

Mulūk

Shāh, Badāʾūnī

<1540 - >: Muntaḵhab ut-tawāriḵh

<Auszüge>. -- Fassung

vom 2008-05-17. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen148.htm

Erstmals publiziert als:

Abū

'l-Faz̤l

ibn

Mubārak <1551-1602>:

The Ā'īn- Akbarī / [by] Abū 'l-Faẓl 'Allāmī; translated

into English

by H. Blochmann [1838 - 1878]. --

2nd ed. / revidsed and ed. by D. C. Phillott. -- Calcutta : Asiatic

Society of Bengal, 1927-1949. -- 3 Bde : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Bibliotheca

Indica ; work no. 61,270,271). -- Vol. 2-3: translated into English

by H. S. Jarrett [1839 - 1919]; corrected by Jadu-Nath Sarkar. --

Bd. 1. -- S. 176 - 218. -- Online:

http://persian.packhum.org/persian/main. -- Zugriff am

2008-05-15

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2008-05-17

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Public domain.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Sanskrit von

Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht

dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B.

Tahoma.

NOTE BY THE TRANSLATOR ON THE RELIGIOUS VIEWS OF THE EMPEROR AKBAR.

In connection with the preceding A'īn, it may be of interest for the general

reader, and of some value for the future historian of Akbar's reign, to collect,

in form of a note, the information which we possess regarding the religious

views of the Emperor Akbar. The sources from which this information are derived,

are, besides Abū'l-Fazl's Ā'īn, the Muntakhabu't-Tawārīkh by 'Abdu'l-Qādir

ibn-i Mulūk Shāh of Badāon —regarding whom I would refer the reader to p. 104,

and to a longer article in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal for

1869—and the Dabistānu'l-Mazāhib

a work written about sixty years after Akbar's death by an unknown Muhammadan

writer of strong Pārsī tendencies. Nor must we forget the valuable testimony of

some of the Portuguese Missionaries whom Akbar called from Goa, as Rodolpho

Aquaviva, Antonio de Monserrato, Francisco Enriques, &c., of whom the first

is

mentioned by Abū'l-Fazl under the name of Pādrī Radalf.

There exist also two articles on Akbar's religious views, one by Captain Vans

Kennedy, published in the second volume of the Transactions of the Bombay

Literary Society, and another by the late Horace Hayman Wilson, which had

originally appeared in the Calcutta Quarterly Oriental Magazine, Vol. I., 1824,

and has been reprinted in the second volume of Wilson's works, London, 1862.

Besides, a few extracts from Badāonī, bearing on this subject, will be found

in

Sir H. Elliott's Bibliographical Index to the Historians of Muhammadan India, p.

243 ff. The Proceedings of the Portuguese Missionaries at Akbar's Court are

described in Murray's [S. 177] Historical Account of Discoveries and Travels in Asia,

Edinburgh, 1820, Vol. II.

I shall commence with extracts from Badāonī.

The translation is literal, which is of great importance in a difficult writer

like Badāonī.

As in the following extracts the years of the Hijrah

are given, the reader may convert them according to this table :—

The year

980 A.H. commenced 14th May, 1572 [Old Style].

981—3rd May, 1573

982—23rd April, 1574

983—12th April, 1575

984—31st March, 1576

985—21st March, 1577

986—10th March, 1578

987—28th February, 1579

988—17th February, 1580

989—5th February, 1581

990—26th January, 1582

991—15th January, 1583

992—4th January, 1584

993—24th December, 1584

994—13th December, 1585

995—2nd December, 1586

996—22nd November, 1587

997—10th November, 1588

998—31th October, 1589

999—20th October, 1590

1000—9th October, 1591

1001—28th September, 1592

1002—17th September. 1593

1003—6th September, 1594

1004—27th August, 1595

Abū'l-Fazl's second introduction to Akbar. His pride.

[Badāonī, edited by Mawlawī Āghā

Aḥmad 'Alī,

in the Bibliotheca Indica, Vol.

II, p. 198.]

"It was during these days [end of 982 A. H.] that Abū'l-Fazl, son of Shaykh

Mubārak of Nāgor, came the second time to court. He is now styled 'Allāmī.

He is the man that set the world in flames. He lighted up the lamp of the

Ṣabāḥīs, illustrating thereby the story of the man who, because he did not

know what to do, took up a lamp in broad daylight, and representing himself as

opposed to all sects, tied the girdle of infallibility round his waist,

according to the saying, 'He who forms an opposition, gains power.' He laid

before the Emperor a commentary on the Āyatu'l-kursī,

which contained all subtleties of the Qur'ān; and though people said that it had

been written by his father, Abū'l-Fazl was much praised. The numerical value of

the letters in the words Tafsīr-i Akbarī (Akbar's commentary) gives the

date of composition [983]. But the emperor praised it, chiefly because he

expected to find in Abū'l-Fazl a man capable of teaching the Mullās a lesson,

whose pride certainly resembles that of Pharaoh, though this expectation was

opposed to the confidence which His Majesty had placed in me.

The reason of Abū'l-Fazl's opinionativeness and pretensions to

infallibility

was this. At the time when it was customary to get hold of, and kill, such as

tried to introduce innovations in religious matters (as had been the case with

Mīr Ḥabshī and others), Shaykh 'Abdu'n-Nabī and Makhdūmu'l-mulk, and other learned

men at court, unanimously [S. 178] represented to the emperor that Shaykh

Mubārak also,

in as far as he pretended to be Mahdī,

belonged to the class of innovators, and was not only himself damned, but led

others into damnation. Having obtained a sort of permission to remove him, they

despatched police officers, to bring him before the emperor. But when they found

that the Shaykh, with his two sons, had concealed himself, they demolished the

pulpit in his prayer-room. The Shaykh, at first, took refuge with Salīm-i

Chishtī at Fatḥpūr, who then was in the height of his glory, and requested him

to intercede for him. Shaykh Salīm, however, sent him money by some of his

disciples, and told him, it would be better for him to go away to Gujrāt. Seeing

that Salīm took no interest in him, Shaykh Mubārak applied to Mīrzā 'Azīz Kokah

[Akbar's foster-brother], who took occasion to praise to the emperor the Shaykh's learning and voluntary poverty, and the superior talents of his two

sons, adding that Mubārak was a most trustworthy man, that he had never received

lands as a present, and that he ['Azīz] could really not see why the Shaykh was

so much persecuted. The emperor at last gave up all thoughts of killing the

Shaykh. In a short time matters took a more favourable turn; and Abū'l-Fazl, when

once in favour with the emperor, (officious as he was, and time-serving, openly

faithless, continually studying His Majesty's whims, a flatterer beyond all

bounds) took every opportunity of reviling in the most shameful way that sect

whose labours and motives have been so little appreciated,

and became the cause not only of the extirpation of these experienced people,

but also of the ruin of all servants of God, especially of Shaykhs, pious men,

of the helpless, and the orphans, whose livings and grants he cut down.

He used to say, openly and implicitly,—

O Lord, send down a proof

for the people of the world!

Send these Nimrods

a gnat as big as an elephant!

These Pharaoh-like fellows have lifted up their heads;

Send them a Moses with

a staff, and a Nile!

[S. 1799 And when in consequence of his harsh proceedings, miseries and misfortunes

broke in upon the 'Ulamās (who had persecuted him and his father), he applied

the following Rubā'ī to them:—

I have set fire to my barn with my own hands,

As I am the incendiary, how can

I complain of my enemy?

No one is my enemy but myself,

Woe

is me! I have torn my garment with my own

hands.

And when during disputations people quoted against him the edict of any

Mujtahid, he used to say, "Oh don't bring

me the arguments of this sweetmeat-seller, and that cobbler, or that tanner!" He

thought himself capable of giving the lie to all Shaykhs and 'Ulamās."

Commencement of the Disputations.

[Badāonī II, p. 200.]

"During the year 983 A. H., many places of worship were built at the command

of His Majesty. The cause was this. For many years previous to 983, the emperor

had gained in succession remarkable and decisive victories. The empire had grown

in extent from day to day; everything turned out well, and no opponent was left

in the whole world. His Majesty had thus leisure to come into nearer contact

with ascetics and the disciples of the Mu'īniyyah sect, and passed much of his

time in discussing the word of God (Qur'ān), and the word of the prophet (the

Ḥadīs, or Tradition). Questions of Ṣūfism, scientific discussions, enquiries

into Philosophy and Law, were the order of the day. His Majesty passed whole

nights in thoughts of God; he continually occupied himself with pronouncing the

names Yā hū and Yā hādī, which had been

mentioned to him, and his heart was full of reverence for Him who is the true

Giver. From a feeling of thankfulness for his past successes, he would sit many

a morning alone in prayer and melancholy, on a large flat stone of an old

building which lay near the palace in a lonely spot, with his head bent over his

chest, and gathering the bliss of early hours."

In his religious habits the emperor was confirmed by a story which he had

heard of Sulaymān,

ruler of Bengal, who, in company with 150 [S. 180] Shaykhs and 'Ulamās, held every

morning a devotional meeting, after which he used to transact state business; as

also by the news that Mīrzā Sulaymān, a prince of Ṣūfī tendencies, and a

Ṣāhib-i ḥāl

was coming to him from Badakhshān.

Among the religious buildings was a meeting place near a tank called

Anūptalāo, where Akbar, accompanied by a few courtiers, met the 'Ulamās and

lawyers of the realm. The pride of the 'Ulamās, and the heretical (Shī'itic)

subjects discussed in this building, caused Mullā Sherī, a poet of Akbar's

reign, to compose a poem in which the place was called a temple of Pharaoh and a

building of Shaddād (vide Qur. Sūr. 89). The result to which the

discussions led, will be seen from the following extract.

[Bad. II, p. 202.]

"For these discussions, which were held every Thursday

night, His Majesty invited the Sayyids, Shaykhs, 'Ulamās, and grandees, by turn.

But as the guests generally commenced to quarrel about their places, and the

order of precedence, His Majesty ordered that the grandees should sit on the

east side; the Sayyids on the west side; the 'Ulamās, to the south; and the

Shaykhs, to the north. The emperor then used to go from one side to the other,

and make his enquiries……, when all at once, one night, 'the vein of the neck of

the 'Ulamās of the age swelled up,' and a horrid noise and confusion ensued. His

Majesty got very angry at their rude behaviour, and said to me [Badāonī],

"In

future report any of the 'Ulamās that cannot behave and talks nonsense, and I

shall make him leave the hall." I gently said to Āṣaf Khān, "If I were to carry

out this order, most of the 'Ulamās would have to leave," when His Majesty

suddenly asked what I had said. On hearing my answer, he was highly pleased, and

mentioned my remark to those sitting near him."

Soon after, another row occurred in the presence of the Emperor.

[Bad. II, p. 210.]

"Some people mentioned that Hājī

Ibrāhīm of Sarhind had given a decree, by which he made it legal to wear red and

yellow clothes, quoting at the same time a Tradition as his proof. On hearing

this, the Chief Justice, in the meeting hall, called him an accursed wretch,

abused him, and lifted up his stick, in order to strike him, when the Hājī by

some subterfuges managed to get rid of him." [S. 1819

Akbar was now fairly disgusted with the 'Ulamās and lawyers; he never

pardoned pride and conceit in a man, and of all kinds of conceit, the conceit of

learning was most hateful to him. From now he resolved to vex the principal

'Ulamās; and no sooner had his courtiers discovered this, than they brought all

sorts of charges against them.

[Bad. II, p. 203.]

"His Majesty therefore ordered Mawlānā 'Abdu'l-lah of Sulṭānpūr, who had

received the title of Makhdūmu'l- Mulk, to come to a meeting, as he

wished to annoy him, and appointed Ḥājī Ibrāhīm, Shaykh Abū'l-Fazl (who had lately come

to court, and is at present the infallible authority in all religious matters,

and also for the New Religion of His Majesty, and the guide of men to truth, and

their leader in general), and several other newcomers, to oppose him. During the

discussion, His Majesty took every occasion to interrupt the Mawlānā, when he

explained anything. When the quibbling and wrangling had reached the highest

point, some courtiers, according to an order previously given by His Majesty,

commenced to tell rather queer stories of the Mawlānā, to whose position one

might apply the verse of the Qur'ān (Sūr. XVI, 72), 'And some one of you shall

have his life prolonged to a miserable age, &c.' Among other stories, Khān Jahān

said that he had heard that Makhdūmu'l-Mulk

had given a fatwa, that the ordinance of pilgrimage was no longer

binding, but even hurtful. When people had asked him the reason of his extraordinary

fatwa, he had said, that the two roads to Makkah, through Persia and over

Gujrāt, were impracticable, because people, in going by land (Persia), had to

suffer injuries at the hand of the Qizilbāshes (i. e., the Shī'ah

inhabitants of Persia), and in going by sea, they had to put up with indignities

from the Portuguese, whose ship-tickets had pictures of Mary and Jesus stamped

on them. To make use, therefore, of the latter alternative would mean to

countenance idolatry; hence both roads were closed up.

"Khān Jahān also related that the

Mawlānā had invented a

clever trick by which he escaped paying the legal alms upon the wealth which he

amassed every year. Towards the end of each year, he used to make over all his

stores to his wife, but he took them back before the year had actually run out.

[S. 182]

"Other tricks also, in comparison with which the tricks of the children of

Moses are nothing, and rumours of his meanness and shabbiness, his open cheating

and worldliness, and his cruelties said to have been practised on the Shaykhs

and the poor of the whole country, but especially on the Aimadārs and other

deserving people of the Panjāb,—all came up, one story after the other. His

motives, 'which shall be revealed on the day of resurrection' (Qur. LXXXVI, 9),

were disclosed; all sorts of stories, calculated to ruin his character and to

vilify him, were got up, till it was resolved to force him to go to Makkah.

"But when people asked him whether pilgrimage was a duty for a man

in his

circumstances, he said No; for Shaykh 'Abdu'n-Nabī had risen to power,

whilst the star of the Mawlānā was fast sinking."

But a heavier blow was to fall on the 'Ulamās. [Bad. II, p. 207.]

"At one of the above-mentioned meetings, His Majesty asked how many

freeborn women a man was legally allowed to marry (by nikāḥ). The

lawyers answered that four was the limit fixed by the prophet. The emperor

thereupon remarked that from the time he had come of age, he had not restricted

himself to that number, and in justice to his wives, of whom he had a large

number, both freeborn and slaves, he now wanted to know what remedy the law

provided for his case. Most expressed their opinions, when the emperor remarked

that Shaykh 'Abdu'n-Nabī had once told him that one of the Mujtahids had had as

many as nine wives. Some of the 'Ulamās present replied that the Mujtahid

alluded to was Ibn Abī Laila; and that some had even allowed eighteen from a too

literal translation of the Qur'ān verse (Qur. Sūr. IV, 3), "Marry whatever women

ye like, two and two,

and three and three, and four and four;" but this was improper. His Majesty then

sent a message to Shaykh 'Abdu'n-Nabī, who replied that he had merely wished to

point out to Akbar that a difference of opinion existed on this point among

lawyers, but that he had not given a fatwa, in order to legalize

irregular marriage proceedings. This annoyed His Majesty very much. "The Shaykh," he said,

"told me at that time a very different thing from what he now

tells me." He never forgot this.

"After much discussion on this point, the 'Ulamās, having collected

[S. 183] every

tradition on the subject, decreed, first, that by Mut'ah [not

by nikāh] a man might marry any number of wives he pleased; and

secondly, that Mut'ah marriages were allowed by Imām Mālik.

The Shī'ahs, as was well known, loved children born in Mut'ah

wedlock more than those born by nikāh wives, contrary to the Sunnīs and

the Ahl-i Jamā'at.

"On the latter point also the discussion got rather lively, and I would refer

the reader to my work entitled Najātu'r-rashīd [Vide note 2, p.

104], in which the subject is briefly discussed. But to make things worse, Naqīb

Khān fetched a copy of the Muwaṭṭa of Imām Mālik, and pointed to a

Tradition in the book, which the Imām had cited as a proof against the legality

of Mut'ah marriages.

"Another night, Qāzī Ya'qūb, Shaykh Abū'l-Fazl, Hājī Ibrāhīm, and a few others

were invited to meet His Majesty in the house near the Anūptalāo

tank. Shaykh Abū'l-Fazl had been selected as the opponent, and laid before the emperor

several traditions regarding Mut'ah marriages, which his father (Shaykh

Mubārak) had collected, and the discussion commenced. His Majesty then asked me,

what my opinion was on this subject. I said, "The conclusion which must be drawn

from so many contradictory traditions and sectarian customs, is this:—Imām Mālik

and the Shī'ahs are unanimous in looking upon Mut'ah marriages as

legal; Imām Shāfi'ī and the Great Imām (Ḥanīfah) look upon Mut'ah

marriages as illegal. But, should at any time a Qāzī of the Mālikī sect decide

that Mut'ah is legal, it is legal, according to the common belief,

even for Shāfi'īs and Ḥanafīs. Every other opinion on this subject

is idle talk." This pleased His Majesty very much."

The unfortunate Shaykh Ya'qūb, however, went on talking about the extent of

the authority of a Qāzī. He tried to shift the ground; but when he saw that he

was discomfited, he said, "Very well, I have nothing else to say,—just as His

Majesty pleases."

"The emperor then said, "I herewith appoint the Mālikī Qāzī Hasan 'Arab as

the Qāzī before whom I lay this case concerning my wives, and you, Ya'qūb, are

from to-day suspended." This was immediately obeyed, and Qāzī Hasan, on the

spot, gave a decree which made Mut'ah marriages legal.

"The veteran lawyers, as Makhdūmu'l-Mulk, Qāzī Ya'qūb, and others, made very

long faces at these proceedings.

"This was the commencement of

'their sere and yellow leaf.'

"The result was that, a few days later,

Mawlānā Jalālu'd-Dīn of Multān a

profound and learned man, whose grant had been transferred, [S. 184] was ordered from

Āgra (to Fatḥpūr Sīkṛī,) and appointed Qāzī of the realm. Qāzī Ya'qūb was sent

to Gaur as District Qāzī.

"From this day henceforth, 'the road of opposition and difference

in opinion'

lay open, and remained so till His Majesty was appointed Mujtahid of the

empire." [Here follows the extract regarding the formula 'Allāhu Akbar,

given on p. 166, note 3.]

[Badāonī II, p. 211.]

"During this year [983], there arrived Hakīm Abū'l-Fatḥ, Hakīm Humāyūn (who

subsequently changed his name to Humāyūn Qulī, and lastly to Hakīm Humām,) and

Nūru'd-Dīn, who as poet is known under the name of Qarārī. They were

brothers, and came from Gīlān, near the Caspian Sea. The eldest brother, whose

manners and address were exceedingly winning, obtained in a short time great

ascendancy over the Emperor; he flattered him openly, adapted himself to every

change in the religious ideas of His Majesty, or even went in advance of them,

and thus became in a short time, a most intimate friend of Akbar.

"Soon after there came from Persia Mullā Muḥammad of Yazd, who got the

nickname of Yazīdī, and attaching himself to the emperor, commenced openly to

revile the Ṣaḥābah (persons who knew Muḥammad, except the twelve Imāms), told queer stories about them, and tried hard to make the emperor a

Shī'ah. But he was soon left behind by Bīr Baṛ—that bastard!—and by Shaykh

Abū'l-Fazl, and

Hakīm Abu'l-Fath, who successfully turned the emperor from the Islām, and led him

to reject inspiration, prophetship, the miracles of the prophet and of the

saints, and even the whole law, so that I could no longer bear their company.

"At the same time, His Majesty ordered Qāzī

Jalālu'd-Dīn and several 'Ulamās to

write a commentary on the Qur'ān; but this led to great rows among them.

"Deb Chand Rājah Manjholah—that fool—once set the whole court

in laughter by

saying that Allah after all had great respect for cows, else the cow would not

have been mentioned in the first chapter (Sūratu'l-baqarah) of the

Qur'ān.

"His Majesty had also the early history of the Islām read out to him, and soon

commenced to think less of the Ṣaḥābah. Soon after, the observance

of the five prayers and the fasts, and the belief in every thing connected with

the prophet, were put down as taqlīdī, or religious blindness,

and man's reason was acknowledged to be the basis of all religion. Portuguese

priests also came frequently; and His Majesty enquired into the articles of

their belief which are based upon reason." [S. 185]

[Badāonī II, p. 245.]

"In the beginning of the next year [984], when His Majesty was at Dīpālpūr

in

Mālwah, Sharīf of Āmul arrived. This apostate had run from country to country,

like a dog that has burnt its foot, and turning from one sect to the other, he

went on wrangling till he became a perfect heretic. For some time he had studied

Ṣūfic nonsense in the school of Mawlānā Muḥammad Zāhid of Balkh, nephew of the

great Shaykh Ḥusain of Khwārazm, and had lived with derwishes. But as he had

little of a derwish in himself, he talked slander, and was so full of conceit,

that they hunted him away. The Mawlānā also wrote a poem against him,

in which

the following verse occurs:

There was a heretic, Sharīf by name,

Who talked very big, though of doubtful

fame.

"In his wanderings he had come to the

Dakhin, where he made himself so

notorious, that the king of the Dakhin wanted to kill him. But he was only put

on a donkey and shewn about in the city. Hindustān, however, is a nice large

place, where anything is allowed, and no one cares for another, and people go on

as they may. He therefore made for Mālwah, and settled at a place five kos

distant from the Imperial camp. Every frivolous and absurd word he spoke, was

full of venom, and became the general talk. Many fools, especially Persian

heretics, (whom the Islām casts out as people cast out hairs which they find

in

dough—such heretics are called Nuqṭawīs, and are destined to be the

foremost worshippers of Antichrist) gathered round him, and spread, at his

order, the rumour that he was the restorer of the Millenium. The sensation was

immense. As soon as His Majesty heard of him, he invited him one night to a

private audience in a long prayer room, which had been made of cloth, and in

which the emperor with his suite used to say the five daily prayers. Ridiculous

in his exterior, ugly in shape, with his neck stooping forward, he performed his

obeisance, and stood still with his arms crossed, and you could scarcely see how

his blue eye (which colour is a sign of hostility to our prophet) shed lies, falsehood, and hypocrisy.

There he stood for a long time, and when he got the order to sit down, he

prostrated himself in worship, and sat down duzānū (vide p. 160,

note 2), like an Indian camel. He talked privately to His Majesty; no one dared

to draw near them, but I sometimes heard from a distance the word 'ilm

(knowledge) because he spoke pretty loud. He called his silly views 'the truth

of truths,' or 'the groundwork of things.' [S. 186]

A fellow ignorant of things external and internal,

From silliness indulging

idle talk.

He is immersed in heresies infernal,

And prattles—God forbid!—of truth eternal.

"The whole talk of the man was a mere repetition of the ideas of Mahmūd of

Basakhwān (a village in Gīlān), who lived at the time of Tīmūr. Mahmūd had

written thirteen treatises of dirty filth, full of such hypocrisy, as no

religion or sect would suffer, and containing nothing but tītāl, which

name he had given to the 'science of expressed and implied language.' The chief

work of this miserable wretch is entitled Baḥr o Kūza (the Ocean and the

Jug), and contains such loathsome nonsense, that on listening to it one's ear

vomits. How the devil would have laughed into his face, if he had heard it, and

how he would have jumped for joy! And this Sharīf— that dirty thief—had also

written a collection of nonsense, which he styled Tarashshuḥ-i Zuhūr,

in

which he blindly follows Mīr 'Abdu'l-Awwal. This book is written in loose,

deceptive aphorisms, each commencing with the words mīfarmūdand

(the master said), a queer thing to look at, and a mass of ridiculous, silly

nonsense. But notwithstanding his ignorance, according to the proverb, 'Worthies

will meet,' he has exerted such an influence on the spirit of the age, and on

the people, that he is now [in 1004] a commander of One Thousand, and His

Majesty's apostle for Bengal, possessing the four degrees of faith, and calling,

as the Lieutenant of the emperor, the faithful to these degrees."

The discussions on Thursday evenings were continued for the next year. In

986, they became more violent, in as far as the elementary principles of the

Islām were chosen as subject, whilst formerly the disputations had turned on

single points. The 'Ulamās even in the presence of the emperor, often lost their

temper, and called each other Kāfirs or accursed.

[Bad. II. p. 225.]

"Makhdūm also wrote a pamphlet against Shaykh

'Abdu'n-Nabī,

in which he accused

him of the murder of Khizr Khān of Shirwān, who was suspected to have reviled

the prophet, and of Mīr Habshī, whom he had ordered to be killed for heresy. But

he also said in the pamphlet that it was wrong to say prayers with 'Abdu'n-Nabī,

because he had been undutiful towards his father, and was, besides, afflicted

with piles. Upon this, Shaykh 'Abdu'n-Nabī called Makhdūm a fool, and cursed him.

The 'Ulamās now broke up into two parties, like the Sibṭīs and Qibṭīs, gathering

either round the Shaykh, or round Makhdūmu'l-Mulk; and the heretic innovators

used this opportunity, to mislead the emperor [S. 187] by their wicked opinions and

aspersions, and turned truth into falsehood, and represented lies as truth.

"His Majesty till now [986] had shewn every sincerity, and

was diligently searching for truth. But his education had been much neglected;

and surrounded as he was by men of low and heretic principles, he had

been forced to doubt the truth of the Islām. Falling from one perplexity into

the other, he lost sight of his real object, the search of truth;

and when the strong embankment of our clear law and our excellent faith had once

been broken through, His Majesty grew colder and colder, till

after the short space of five or six years not a trace of Muhammadan feeling was

left in his heart. Matters then became very different."

[Bad. II, p. 239.]

"In 984, the news arrived that Shāh

Ṭahmāsp of Persia had died, and Shāh Ismā'īl II. had succeeded him. The Tārīkh

of his accession is given in the first letters of the three words

Shāh Ismā'īl gave the order that any

one who wished to go to Makkah could have his travelling expenses paid from the

royal exchequer. Thus thousands of people partook of the spiritual blessing of

pilgrimage, whilst here you dare not now [1004] mention that word, and you would

expose yourself to capital punishment, if you were to ask leave from court for

this purpose."

[Bad. II, p. 241.]

"In 985, the news arrived that Shāh Ismā'īl, son of Shāh Ṭahmāsp had been

murdered, with the consent of the grandees, by his sister Parī Jān Khānum.

Mīr Ḥaidar, the riddle writer, found the Tārīkh of his accession

in the words

Shahinshāh-i rūi zamīn [984] 'a king of the face of the earth,' and the Tārīkh of his death in Shahinshāh-i zer-i zamīn [985]

'a king below the

face of the earth.'

At that time also there appeared in Persia the great comet which had been

visible in India (p. 240), and the consternation was awful, especially as at the

same time the Turks conquered Tabrīz, Shirwān, and Māzandarān. Sulṭān

Muḥammad

Khudābandah, son of Shāh Ṭahmāsp, but by another mother, succeeded; and with him

ended the time of reviling and cursing the Ṣaḥābah.

"But the heretical ideas had certainly entered Hindustān from Persia."

[S. 188]

BADĀONĪ'S SUMMARY OF THE REASONS WHICH LED AKBAR TO RENOUNCE THE ISLĀM.

[Bad. II, p. 256.]

The following are the principal reasons which led His Majesty from the right

path. I shall not give all, but only some, according to the proverb, "That which

is small, guides to that which is great, and a sign of fear in a man points him

out as the culprit."

The principal reason is the large number of learned men of all denominations

and sects that came from various countries to court, and received personal

interviews. Night and day people did nothing but enquire and investigate;

profound points of science, the subtleties of revelation, the curiosities of

history, the wonders of nature, of which large volumes could only give a summary

abstract, were ever spoken of. His Majesty collected the opinions of every one,

especially of such as were not Muhammadans, retaining whatever he approved of,

and rejecting everything which was against his disposition, and ran counter to

his wishes. From his earliest childhood to his manhood, and from his manhood to

old age, His Majesty has passed through the most various phases, and through all

sorts of religious practices and sectarian beliefs, and has collected every

thing which people can find in books, with a talent of selection peculiar to

him, and a spirit of enquiry opposed to every [Islāmitic] principle. Thus a

faith based on some elementary principles traced itself on the mirror of his

heart, and as the result of all the influences which were brought to bear on His

Majesty, there grew, gradually as the outline on a stone, the conviction in his

heart that there were sensible men in all religions, and abstemious thinkers,

and men endowed with miraculous powers, among all nations. If some true

knowledge was thus everywhere to be found, why should truth be confined to one

religion, or to a creed like the Islām, which was comparatively new, and

scarcely a thousand years old; why should one sect assert what another denies,

and why should one claim a preference without having superiority conferred on

itself.

Moreover Sumanīs

and Brahmins managed to get frequent private interviews with His Majesty. As

they surpass other learned men in their treatises on morals, and on physical and

religious sciences, and reach a high degree in their knowledge of the future, in

spiritual power and human perfection, they brought proofs, based on reason and

testimony, [S. 189] for the truth of their own, and the fallacies of other religions, and

inculcated their doctrines so firmly, and so skilfully represented things as

quite self-evident which require consideration, that no man, by expressing his

doubts, could now raise a doubt in His Majesty, even if mountains were to

crumble to dust, or the heavens were to tear asunder.

Hence His Majesty cast aside the Islāmitic revelations regarding resurrection,

the day of judgment, and the details connected with it, as also all ordinances

based on the tradition of our prophet. He listened to every abuse which the

courtiers heaped on our glorious and pure faith, which can be so easily followed;

and eagerly seizing such opportunities, he shewed in words and gestures, his

satisfaction at the treatment which his original religion received at their

hands.

How wise was the advice which the guardian gave a lovely being,

"Do not smile at every face, as the rose does at every

zephyr."

When it was too late to profit by the lesson,

She could but frown, and hang

down the head.

For some time His Majesty called a Brahmin, whose name was Purukhotam author

of a commentary on the ..,

whom he asked to invent particular Sanscrit names for all things in existence.

At other times, a Brahmin of the name of Debī was pulled up the wall of the

castle,

sitting on a chārpāi, till he arrived near a balcony where the emperor

used to sleep. Whilst thus suspended, he instructed His Majesty in the secrets

and legends of Hinduism, in the manner of worshipping idols, the fire, the sun

and stars, and of revering the chief gods of these unbelievers, as Brahma,

Mahādev, Bishn, Kishn, Rām, and Mahāmāī, who are supposed to have been men, but

very likely never existed, though some, in their idle belief, look upon them as

gods, and others as angels. His Majesty, on hearing further how much the people

of the country prized their institutions, commenced to look upon them with

affection. The doctrine of the transmigration of souls especially took a deep

root in his heart, and he approved of the saying, —"There is no religion in

which the doctrine of transmigration has not taken firm root." Insincere

flatterers composed treatises, in order to fix the evidence for this doctrine;

and as His Majesty relished enquiries into the sects of these infidels (who

cannot be counted, so numerous they are, and who have no end of [S. 190] revealed books,

but nevertheless, do not belong to the Ahl-i Kitāb (Jews, Christians, and

Muhammadans), not a day passed, but a new fruit of this loathsome tree ripened

into existence.

Sometimes again, it was Shaykh

Tāju'd-Dīn of Dihlī, who had to attend

the emperor. This Shaykh is the son of Shaykh Zakariyā of Ajodhan. The principal

'Ulamās of the age call him Tāju'l-'Ārifīn, or crown of the

Ṣūfīs.

He had learned under Shaykh Zamān of Pānīpat, author of a commentary on the

Lawā'iḥ, and of other very excellent works, was in Ṣūfism and pantheism second

only to Shaykh Ibn 'Arabī, and had written a comprehensive commentary on the

Nuzhatu'l-ArwāH. Like the preceding he was drawn up the wall of the castle.

His Majesty listened whole nights to his Ṣūfic trifles. As the Shaykh was not

overstrict in acting according to our religious law, he spoke a great deal of

the pantheistic presence, which idle Ṣūfīs will talk about, and which generally

leads them to denial of the law and open heresy. He also introduced polemic

matters, as the ultimate salvation by faith of Pharaoh—God's curse be upon him!—

which is mentioned in the Fuṣūṣu'l-Ḥikam,

or the excellence of hope over fear,

and many other things to which men incline from weakness of disposition,

unmindful of cogent reasons, or distinct religious commands, to the contrary.

The Shaykh is therefore one of the principal culprits, who weakened His

Majesty's faith in the orders of our religion. He also said that infidels would,

of course, be kept for ever in hell, but it was not likely, nor could it be

proved, that the punishment in hell was eternal. His explanations of some verses

of the Qur'ān, or of the Tradition of our prophet, were often far-fetched.

Besides, he mentioned that the phrase 'Insān-i Kāmil (perfect man)

referred to the ruler of the age, from which he inferred that the nature of a

king was holy. In this way, he said many agreeable things to the emperor, rarely

expressing the proper meaning, but rather the opposite of what he knew to be

correct. Even the sijdah (prostration), which people mildly call

zamīnbos (kissing the ground,) he allowed to be due to the Insān-i Kāmil; he

looked upon the respect due to the king as a religious command, and called the

face of the king Ka'ba-yi Murādāt, the sanctum of desires,

[S. 191] and

Qibla-yi ḥājāt, the cynosure of necessities. Such blasphemies

other people supported by quoting stories of no credit, and by referring to the

practice followed by disciples of some heads of Indian sects. And after this,

when.…

Other great philosophical writers of the age also expressed opinions, for

which there is no authority. Thus Shaykh Ya'qūb of Kashmīr, a well known writer,

and at present the greatest authority in religious matters, mentioned some

opinions held by 'Ainu'l-Quzāt of Hamadān, that our prophet Muḥammad was a

personification of the divine name of Al-hādī (the guide), and the devil

was the personification of God's name of Al-muzill (the tempter),

that both names, thus personified, had appeared in this world, and that both

personifications were therefore necessary.

Mullā Muḥammad of Yazd, too, was drawn up the wall of the castle, and uttered

unworthy, loathsome abuse against the first three Khalīfahs, called the whole

Ṣahābah, their followers and next followers, and the saints of past ages,

infidels and adulterers, slandered the Sunnīs and the Ahl i Jamā'at,

and represented every sect, except the Shī'ah, as damned and leading men into

damnation.

The differences among the 'Ulamās, of whom one called lawful what the other

called unlawful, furnished His Majesty with another reason for apostacy. The

emperor also believed that the 'Ulamās of his time were superior in dignity and

rank to Imām-i Ghazzālī and Imām-i Rāzī,

and knowing from experience the flimsiness of his 'Ulamās, he judged those great

men of the past by his contemporaries, and threw them aside.

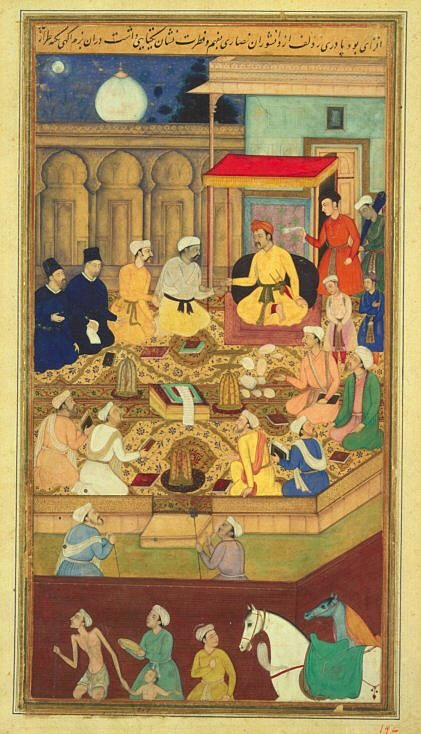

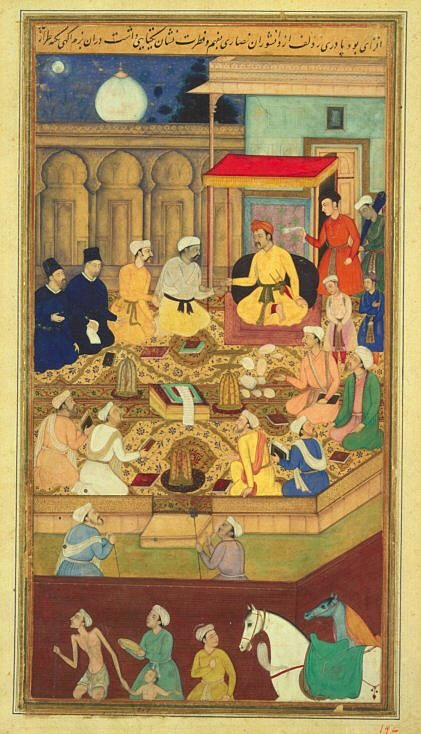

Abb.: Akbar mit Jesuiten / von Nar Singh, 1605

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Üublic domain]

Learned monks also came from Europe, who go by the name of Pādre.

They have an infallible head, called Pāpā. He can change any religious

ordinances as he may think advisable, and kings have to submit to his authority.

These monks brought the gospel, and mentioned to the emperor their proofs for

the Trinity. His Majesty firmly believed in the truth of the Christian religion,

and wishing to spread the doctrines of [S. 192] Jesus, ordered Prince Murād

to take a few lessons in Christianity by way of auspiciousness, and charged

Abū'l-Fazl to translate the Gospel. Instead of the usual

Bismi'llāhi'r-rahmāni'r-rahīmi,

the following lines were used—

Ay nām-i tu Jesus o Kiristū

(O thou whose names are Jesus and Christ)

which means, 'O thou whose name is gracious and blessed;'

and Shaykh Faizī added another half, in order to complete the verse

Subhāna-ka lā siwā-ka Yā hū.

(We praise Thee, there is no one besides Thee, O God!)

These accursed monks applied the description of cursed Satan, and of his

qualities, to Muḥammad, the best of all prophets—God's blessings rest on him and

his whole house!—a thing which even devils would not do.

Bīr Baṛ also impressed upon the emperor that the sun was the primary origin

of every thing. The ripening of the grain on the fields, of fruits and

vegetables, the illumination of the universe, and the lives of men, depended

upon the Sun. Hence it was but proper to worship and reverence this luminary;

and people in praying should face towards the place where he rises, instead of

turning to the quarter where he sets. For similar reasons, said Bīr Baṛ, should

men pay regard to fire and water, stones, trees, and other forms of existence,

even to cows and their dung, to the mark on the forehead and the Brahminical

thread.

Philosophers and learned men who had been at Court, but were

in disgrace,

made themselves busy in bringing proofs. They said, the sun was 'the greatest

light,' the source of benefit for the whole world, the nourisher of kings, and

the origin of royal power.

This was also the cause why the Nawrūz-i Jalālī

was observed, on which day, since His Majesty's accession, a great feast was

given. His Majesty also adopted different suits of clothes of seven different

colours, [S. 193] each of which was worn on a particular day of the week in

honour of the

seven colours of the seven planets.

The emperor also learned from some Hindus

formulae, to reduce the

influence of

the sun to his subjection, and commenced to read them mornings and evenings as a

religious exercise. He also believed that it was wrong to kill cows, which the

Hindus worship; he looked upon cow-dung as pure, interdicted the use of beef,

and killed beautiful men (?) instead of cows. The doctors confirmed the emperor

in his opinion, and told him, it was written in their books that beef was

productive of all sorts of diseases, and was very indigestible.

Fire-worshippers also had come from Nausārī in Gujrāt, and proved to His

Majesty the truth of Zoroaster's doctrines. They called fire-worship 'the great

worship,' and impressed the emperor so favourably, that he learned from them the

religious terms and rites of the old Pārsīs, and ordered Abū'l-Fazl to make

arrangements, that sacred fire should be kept burning at court by day and by

night, according to the custom of the ancient Persian kings, in whose

fire-temples it had been continually burning; for fire was one of the

manifestations of God, and 'a ray of His rays.'

His Majesty, from his youth, had also been accustomed to celebrate the Hom

(a kind of fire-worship), from his affection towards the Hindu princesses of his

Harem.

From the New Year's day of the twenty-fifth year of his reign [988], His

Majesty openly worshipped the sun and the fire by prostrations; and the

courtiers were ordered to rise, when the candles and lamps were lighted in the

palace. On the festival of the eighth day of Virgo, he put on the mark on the

forehead, like a Hindu, and appeared in the Audience Hall, when several Brahmins

tied, by way of auspiciousness, a string with jewels on it round his hands,

whilst the grandees countenanced these proceedings by bringing, according to

their circumstances, pearls and jewels as presents. The custom of Rāk'hī (or

tying pieces of clothes round the wrists as amulets) became quite common.

When orders, in opposition to the Islām, were quoted by people of other

religions, they were looked upon by His Majesty as convincing, whilst Hinduism

is in reality a religion, in which every order is nonsense. The Originator of

our belief, the Arabian Saints, all were said to be adulterers, and highway

robbers, and all the Muhammadans were declared worthy of reproof, till at length

His Majesty belonged to those of whom the Qur'ān says (Sūr. 61, 8:) "They seek to

extinguish God's light with their mouths: but God will perfect his light, though

the infidels be averse [S. 194] thereto." In fact matters went so far, that proofs were

no longer required when anything connected with the Islām was to be abolished."

Akbar publicly assumes the spiritual leadership of the nation.

[Bad. II, p. 268.]

In this year [987], His Majesty was anxious to unite in his person the powers

of the state and those of the Church; for he could not bear to be subordinate to

any one. As he had heard that the prophet, his lawful successors, and some of

the most powerful kings, as Amīr Tīmūr Ṣāhib-qirān, and Mīrzā Ulugh Beg-i Gurgān,

and several others, had themselves read the Khuṭbah (the Friday prayer),

he resolved to do the same, apparently in order to imitate their example, but in

reality to appear in public as the Mujtahid of the age. Accordingly, on Friday,

the first Jumāda'l-awwal 987, in the Jāmi' Masjid of Fatḥpūr, which he had built

near the palace, His Majesty commenced to read the Khuṭbah. But all at once he

stammered and trembled, and though assisted by others, he could scarcely read

three verses of a poem, which Shaykh Faizī had composed, came quickly down from

the pulpit, and handed over the duties of the Imām (leader of the prayer) to

Hāfiz Muḥammad Amīn, the Court Khaṭīb. These are the verses—

The Lord has given me the empire,

And a wise heart, and a strong arm,

He has guided me in righteousness and justice,

And has removed from my

thoughts everything but justice.

His praise surpasses man's understanding,

Great is His power, Allāhu Akbar!"

[p. 269.]

"As it was quite customary in those

days to speak ill of the doctrine and orders of the Qur'ān, and as Hindu

wretches and Hinduizing Muhammadans openly reviled our prophet, irreligious

writers left out in the prefaces to their books the customary praise of the

prophet, and after saying something to the praise of God, wrote eulogies of the

emperor instead. It was impossible even to mention the name of the prophet,

because these liars (as Abū'l-Fazl, Faizī, &c.) did not like it. This wicked

innovation gave general offence, and sowed the seed of evil throughout the

country; but notwithstanding this, a lot of low and mean fellows [S. 195] put piously on

their necks the collar of the Divine Faith, and called themselves disciples,

either from fear, or hope of promotion, though they thought it impossible to say

our creed."

[p. 270 to 272.]

"In the same year [987], a document made its appearance, which bore the

signatures and seals of Makhdūmu'l-Mulk, of Shaykh 'Abdu'n-Nabī, ṣadru'ṣ-ṣudūr, of

Qāzī Jalālu'd-Dīn of Multān, Qāzīyu'l-quzāt, of

Ṣadr Jahān, the muftī of the empire,

of Shaykh Mubārak, the deepest writer of the age, and of Ghāzī Khān of

Badakhshān, who stood unrivalled in the various sciences.The object of the

document was to settle the superiority of the Imām-i 'ādil (just

leader) over the Mujtahid, which was proved by a reference to an ill-supported

authority. The whole matter is a question, regarding which people differ in

opinion; but the document was to do away with the possibility of disagreeing

about laws, whether political or religious, and was to bind the lawyers in spite

of themselves. But before the instrument was signed, a long discussion took

place as to the meaning of ijtihād, and as to whom the term Mujtahid

was applicable, and whether it really was the duty of a just Imām who, from his

acquaintance with politics, holds a higher rank than the Mujtahid, to decide,

according to the requirements of the times, and the wants of the age, all such

legal questions on which there existed a difference of opinion. At last,

however, all signed the document, some willingly, others against their

convictions.

I shall copy the document verbatim.

The Document.

'Whereas Hindūstān has now become the centre of security and peace, and the

land of justice and beneficence, a large number of people, especially

learned men and lawyers, have immigrated and chosen this country for their home.

Now we, the principal 'Ulamās, who are not only well versed in the several

departments of the law and in the principles of jurisprudence, and

well-acquainted with the edicts which rest on reason or testimony, but are also

known for our piety and honest intentions, have duly considered the deep meaning,

- first, of the verse of the Qur'ān (Sūr. IV, 62,) "Obey God,

and

obey the prophet, and those who have authority among you," and

- secondly, of the genuine tradition, "Surely,

the man who is

dearest to God on the day of judgment, is the Imām i 'Ādil:

whosoever obeys the Amīr, obeys Me; and whosoever rebels against him,

rebels against Me," and

- thirdly, of several other proofs based on

reasoning or testimony;

and we have agreed that the rank of a

Sulṭān-i 'Ādil

(a just ruler) is higher [S. 196] in the eyes of God than the rank of a Mujtahid.

Further we declare that the king of the Islām, Amīr of the Faithful, shadow of

God in the world, Abdu'l-Fatḥ Jalālu'd-Dīn Muḥammad Akbar Pādishāh-i ghāzī,

whose kingdom God perpetuate, is a most just, a most wise, and a most

God-fearing king. Should therefore, in future, a religious question come up,

regarding which the opinions of the Mujtahids are at variance, and His Majesty,

in his penetrating understanding and clear wisdom, be inclined to adopt, for the

benefit of the nation and as a political expedient, any of the conflicting

opinions which exist on that point, and issue a decree to that effect, we do

hereby agree that such a decree shall be binding on us and on the whole nation.

Further, we declare that, should His Majesty think fit to

issue a new order,

we and the nation shall likewise be bound by it, provided always that such an

order be not only in accordance with some verse of the Qur'ān, but also of real

benefit for the nation; and further, that any opposition on the part of the

subjects to such an order as passed by His Majesty, shall involve damnation in

the world to come, and loss of religion and property in this life.

This document has been written with honest intentions, for the glory of God,

and the propagation of the Islām, and is signed by us, the principal 'Ulamās and

lawyers, in the month of Rajab of the year 987 of the Hijrah.'

The draft of this document when presented to the emperor, was

in the

handwriting of Shaykh Mubārak. The others had signed it against their will, but

the Shaykh had added at the bottom that he had most willingly signed his name;

for this was a matter, which, for several years, he had been anxiously looking

forward to.

No sooner had His Majesty obtained this legal instrument, than the road of

deciding any religious question was open; the superiority of intellect of the

Imām was established, and opposition was rendered impossible. All orders

regarding things which our law allows or disallows, were abolished,

and the superiority of intellect of the Imām became law.

But the state of Shaykh Abū'l-Fazl resembled that of the poet

Ḥairatī of

Samarqand,

who after having been annoyed by the cool and sober people of Māwara'n-nahr

(Turkistān), joined the old foxes of Shī'itic Persia, and chose 'the roadless

road.' You might apply the proverb to him, 'He prefers hell to shame on earth.'

[S. 197]

On the 16th Rajab of this year, His Majesty made a pilgrimage to Ajmīr. It

is

now fourteen years that His Majesty has not returned to that place. On the 5th

Sha'bān, at the distance of five kos from the town, the emperor

alighted, and went on foot to the tomb of the saint (Mu'īnu'd-Dīn). But sensible

people smiled, and said, it was strange that His Majesty should have such a

faith in the Khwājah of Ajmīr, whilst he rejected the foundation of everything,

our prophet, from whose 'skirt' hundreds of thousands of saints of the highest

degree had sprung."

[p. 273.]

"After Makhdūmu'l-Mulk and Shaykh

'Abdu'n-Nabī had left for Makkah (987), the

emperor examined people about the creation of the Qur'ān, elicited their belief,

or otherwise, in revelation, and raised doubts in them regarding all things

connected with the prophet and the imāms. He distinctly denied the existence of

Jinns, of angels, and of all other beings of the invisible world, as well

as the miracles of the prophet and the saints; he rejected the successive

testimony of the witnesses of our faith, the proofs for the truths of the Qur'ān

as far as they agree with man's reason, the existence of the soul after the

dissolution of the body, and future rewards and punishments in as far as they

differed from metempsychosis.

Some copies of the Qur'ān, and a few old graves

Are left as witnesses for these

blind men.

The graves, unfortunately, are all silent,

And no one searches for truth in

the Qur'ān.

An 'Īd has come again, and bright days will come—like the face of the

bride.

And the cupbearer will again put wine into the jar—red like blood.

The reins of prayer and the muzzle of fasting—once more

Will fall from these asses—alas, alas!

His Majesty had now determined publicly to use the formula,

'There

is no God

but God, and Akbar is God's representative.' But as this led to commotions, he

thought better of it, and restricted the use of the formula to a few people in

the Harem. People expressed the date of this event by the words fitnahā-yi

ummat, the ruin of the Church (987). The emperor tried hard to convert

Quṭbu'd-Dīn Muḥammad Khān and Shahbāz Khān (vide List of grandees, IId

book, Nos. 28 and 80), and several others. But they staunchly objected.

Quṭbu'd-Dīn said, "What would the kings of the West, as the Sulṭān of

Constantinople, say, if he [S. 198] heard all this. Our faith is the same, whether a man

hold high or broad views." His Majesty then asked him, if he was in India on a

secret mission from Constantinople, as he shewed so much opposition; or if he

wished to keep a small place warm for himself, should he once go away from

India, and be a respectable man there: he might go at once. Shahbāz got excited,

and took a part in the conversation; and when Bīr Bar—that hellish dog— made a

sneering remark at our religion, Shahbāz abused him roundly, and said, "You

cursed infidel, do you talk in this manner? It would not take me long to settle

you." It got quite uncomfortable, when His Majesty said to Shahbāz in

particular, and to the others in general, "Would that a shoefull of excrements

were thrown into your faces."

[p. 276.]

"In this year the Tamghā (inland tolls) and the Jazya (tax on

infidels), which brought in several krors of dāms, were abolished,

and edicts to this effect were sent over the whole empire."

In the same year a rebellion broke out at Jaunpūr, headed by

Muḥammad Ma'ṣūm

of Kābul, Muḥammad Ma'ṣūm Khān, Mu'izzu'l_Mulk, 'Arab Bahādur, and other

grandees. They objected to Akbar's innovations in religious matters, in as far

as these innovations led to a withdrawal of grants of rent-free land. The rebels

had consulted Mullā Muḥammad of Yazd (vide above, pp. 175, 182), who was

Qāziyu-l-quzāt at Jaunpūr; and on obtaining his opinion that, under the

circumstances, rebellion against the king of the land was lawful, they seized

some tracts of land, and collected a large army. The course which this rebellion

took, is known from general histories; vide Elphinstone, p. 511. Mullā

Muḥammad of Yazd, and Mu'izzu'l-Mulk, in the beginning of the rebellion, were

called by the emperor to Āgra, and drowned, on the road, at the command of the

emperor, in the Jamnā.

In the same year the principal 'Ulamās, as Makhdūmu'l-Mulk,

Shaykh Munawwar,

Mullā 'Abdu'sh-Shukūr, &c., were sent as exiles to distant provinces.

[p. 278.]

"Hājī Ibrāhīm of Sarhind (vide above, p. 105) brought to court an old,

worm-eaten MS. in queer characters, which, as he pretended, was written by

Shaykh Ibn 'Arabī. In this book, it was said that the Ṣāhib-i Zamān

was to have many wives, and that he would shave his beard. Some of the

characteristics mentioned in the book as belonging to him, [S. 199] were found to agree

with the usages of His Majesty. He also brought a fabricated tradition that the

son of a Ṣahābī (one who knew Muḥammad) had once come before the prophet

with his beard cut off, when the prophet had said that the inhabitants of

Paradise looked like that young man. But as the Hājī during discussions, behaved

impudently towards Abū'l-Fazl, Hakīm Abu'l-Fatḥ, and Shāh Fatḥu'llāh, he was sent to

Rantanbhūr, where he died in 994.

Farmāns were also sent to the leading Shaykhs and 'Ulamās of the various

districts to come to Court, as His Majesty wished personally to enquire into

their grants (vide 2nd book, Ā'īn 19) and their manner of living. When

they came, the emperor examined them singly, giving them private interviews, and

assigned to them some lands, as he thought fit. But when he got hold of one who

had disciples, or held spiritual soirées, or practised similar tricks, he

confined them in forts, or exiled them to Bengal or Bhakkar. This practice

become quite common. The poor Shaykhs who were, moreover, left to

the mercies of Hindu Financial Secretaries, forgot in exile their spiritual

soirées, and had no other place where to live, except mouseholes."

[p. 288.]

"In this year (988) low and mean fellows, who pretended to be learned, but

were in reality fools, collected evidences that His Majesty was the Ṣāhib-i

Zamān, who would remove all differences of opinion among the seventy-two

sects of the Islām. Sharīf of Āmul brought proofs from the writings of Mahmūd

of Basakhwān (vide above, p. 177), who had said that, in 990, a man would

rise up who would do away with all that was wrong .

And Khwājah Mawlānā of Shīrāz, the heretical wizard, came with a pamphlet by

some of the Sharīfs of Makkah, in which a tradition was quoted that the earth

would exist for 7,000 years, and as that time was now over, the promised

appearance of Imām Mahdī would immediately take place. The Mawlānā also brought

a pamphlet written by himself on the subject. The Shī'ahs mentioned similar

nonsense connected with 'Alī, and some quoted the following Rubā'ī, which

is

said to have been composed by Nāṣir-i Khusraw,

or, according to some, by another poet:—

In 989, according to the decree of fate,

The stars from all sides shall meet

together.

In the year of Leo, the month of Leo, and on the day of Leo,

The Lion of God

will stand forth from behind the veil. [S. 200]All this made His Majesty the more

inclined to claim the dignity of a prophet, perhaps I should say, the dignity of

something else."

[p. 291.]

"At one of the meetings, the emperor asked those who were present, to mention

each the name of man who could be considered the wisest man of the age; but they

should not mention kings, as they formed an exception. Each then mentioned that

man in whom he had confidence. Thus Hakīm Humām (vide above, p.

175) mentioned himself, and Shaykh Abū'l-Fazl his own father.

"During this time, the four degrees of faith in His Majesty were defined. The

four degrees consisted in readiness to sacrifice to the Emperor property, life,

honour, and religion. Whoever had sacrificed these four things, possessed four

degrees; and whoever had sacrificed one of these four, possessed one degree.

"All the courtiers now put their names

down as faithful disciples of the throne."

[p. 299.]

"At this time (end of 989), His Majesty sent Shaykh Jamāl Bakhtyār to bring

Shaykh Quṭbu'd-Dīn of Jalesar who, though a wicked man, pretended to be

'attracted

by God.' When Quṭbu'd-Dīn came, the emperor brought him to a conference with some

Christian priests, and rationalists, and some other great authorities of the

age. After a discussion, the Shaykh exclaimed, 'Let us make a great fire, and in

the presence of His Majesty I shall pass through it. And if any one else gets

safely through, he proves by it the truth of his religion." The fire was made.

The Shaykh pulled one of the Christian priests by the coat, and said to him, "Come on, in the name of God!" But none of the priests had the courage to go.

Soon after the Shaykh was sent into exile to Bhakkar, together with other

faqīrs, as His Majesty was jealous of his triumph.

A large number of Shaykhs and Faqīrs were also sent to other places, mostly

to Qandahār, where they were exchanged for horses. About the same time, the

emperor captured a sect consisting of Shaykhs and disciples, and known under the

name of Ilāhīs. They professed all sorts of nonsense, and practised

deceits. His Majesty asked them whether they repented of their vanities. They

replied, "Repentance is our Maid." And so they had invented similar names for

the laws and religious commands of the Islām, and for the fast. At the command

of His Majesty, [S. 201] they were sent to Bhakkar and Qandahār, and were given to

merchants in exchange for Turkish colts."

[p. 301.]

"His Majesty was now (990) convinced that the Millennium of the Islāmitic

dispensation was drawing near. No obstacle, therefore, remained to promulgating

the designs which he had planned in secret. The Shaykhs and 'Ulamās who, on

account of their obstinacy and pride, had to be entirely discarded, were gone,

and His Majesty was free to disprove the orders and principles of the Islām, and

to ruin the faith of the nation by making new and absurd regulations. The first

order which was passed was, that the coinage should shew the era of the

Millennium, and that a history of the one thousand years should be written, but

commencing from the death of the prophet. Other extraordinary innovations were

devised as political expedients, and such orders were given that one's senses

got quite perplexed. Thus the sijdah, or prostration, was ordered to be

performed as being proper for kings; but instead of sijdah, the word

zamīnbos was used. Wine also was allowed, if used for strengthening the body,

as recommended by doctors; but no mischief or impropriety was to result from

the use of it, and strict punishments were laid down for drunkenness, or

gatherings, and uproars. For the sake of keeping everything within proper

limits, His Majesty established a wine-shop near the palace, and put the wife of

the porter in charge of it, as she belonged to the caste of wine-sellers. The

price of wine was fixed by regulations, and any sick persons could obtain wine

on sending his own name and the names of his father and grandfather to the clerk

of the shop. Of course, people sent in fictitious names, and got supplies of

wine; for who could strictly enquire into such a matter? It was in fact nothing

else but licensing a shop for drunkards. Some people even said that pork formed

a component part of this wine! Notwithstanding all restrictions, much mischief

was done, and though a large number of people were daily punished, there was no

sufficient check.

"Similarly, according to the proverb,

'Upset, but don't spill,' the prostitutes of the realm (who had collected at

the capital, and could scarcely be counted, so large was their number), had a

separate quarter of the town assigned to them, which was called Shaiṭānpūra,

or Devilsville. [S. 202] A Dārogah and a clerk also were appointed for it, who registered

the names of such as went to prostitutes, or wanted to take some of them to

their houses. People might indulge in such connexions, provided the toll

collectors knew of it. But without permission, no one was allowed to take

dancing girls to his house. If any well-known courtier wanted to have a virgin,

they should first apply to His Majesty, and get his permission. In the same way,

boys prostituted themselves, and drunkenness and ignorance soon led to

bloodshed. Though in some cases capital punishment was inflicted, certain

privileged courtiers walked about proudly and insolently doing what they liked.

"His Majesty himself called some of the principal prostitutes and asked them

who had deprived them of their virginity. After hearing their replies, some of

the principal and most renowned grandees were punished or censured, or confined

for a long time in fortresses. Among them, His Majesty came across one whose

name was Rājah Bīr Baṛ, a member of the Divine Faith,

who had gone beyond the four degrees, and acquired the four cardinal virtues.

At that time he happened to live in his jāgīr in the Pargana of Karah; and when

he heard of the affair, he applied for permission to turn Jogī; but His Majesty

ordered him to come to Court, assuring him that he need not be afraid.

"Beef was interdicted, and to touch beef was considered defiling. The reason

of this was that, from his youth, His Majesty had been in company with Hindu

libertines, and had thus learnt to look upon a cow—which in their opinion is one

of the reasons why the world still exists—as something holy. Besides, the

Emperor was subject to the influence of the numerous Hindu princesses of the

Harem, who had gained so great an ascendancy over him, as to make him forswear

beef, garlic, onions, and the wearing of a beard,

which things His Majesty still avoids. He had also introduced, though modified

by his peculiar views, Hindu customs and heresies into the court assemblies, and

introduces them still, in order to please and win the Hindus and their castes;

he abstained from everything which they think repugnant to their nature, and

looked upon shaving the beard as the highest sign of friendship and affection

for him. Hence this custom has become very general. Pandering pimps also

expressed the opinion that the beard takes its nourishment from the testicles;

for no eunuch had a beard; and one could not exactly see of what merit or [S.

203]

importance it was to cultivate a beard. Moreover, former ascetics had looked

upon carelessness in letting the beard grow, as one way of mortifying one's

flesh, because such carelessness exposed them to the reproach

of the world; and as, at present, the silly lawyers of the Islām looked upon

cutting down the beard as reproachful, it was clear that shaving was now a way

of mortifying the flesh, and therefore praiseworthy, but not letting the beard

grow. (But if any one considers this argument calmly, he will soon detect the

fallacy.) Lying, cheating Muftīs also quoted an unknown tradition, in which

it

was stated that 'some Qāzīs' of Persia had shaved their beards. But the words

ka-mā yaf'al-ūu ba'zu'l-quzāti (as some Qāzīs have done),

which occur in this tradition, are based upon a corrupt reading, and should be

ka-mā yaf'alū ba'zu'l-uṣāt (as some wicked men

have done).

"The ringing of bells as in use with the Christians, and the showing of the

figure of the cross, and…….., and other

childish playthings of theirs, were daily in practice. The words Kufr shāyi'

shud, or 'heresy became common ', express the Tārīkh (985). Ten

or twelve years after the commencement of these doings, matters had gone so far

that wretches like Mīrzā Jānī, chief of Tattah, and other apostates, wrote their

confessions on paper as follows:—'I, such a one, son of such a one, have

willingly and cheerfully renounced and rejected the Islām in all its phases,

whether low or high, as I have witnessed it in my ancestors, and have joined the

Divine Faith of Shāh Akbar, and declare myself willing to sacrifice to him my

property and life, my honour and religion.' And these papers—there could be no

more effective letters of damnation—were handed over to the Mujtahid (Abū'l-Fazl)

of the new Creed, and were considered a source of confidence or promotion. The

Heavens might have parted asunder, and earth might have opened her abyss, and

the mountains have crumbled to dust!

"In opposition to the Islām, pigs and dogs were no longer looked upon as

unclean. A large number of these animals was kept in the Harem, and in the

vaults of the castle, and to inspect them daily, was considered a religious

exercise. The Hindus, who believe in incarnations, said that the boar belonged

to the ten forms which God Almighty had once assumed.

"'God is indeed Almighty—but not what they say.'

"The saying of some wise men

that a dog had ten virtues, and that a man, if he possess one of them, was a

saint, was also quoted as a proof. Certain courtiers and friends of His Majesty,

who were known for their [S. 204] excellence in every department, and proverbial as court

poets,

used to put dogs on a tablecloth and feed them, whilst other heretical poets,

Persians and Hindustānīs, followed this example, even taking the tongues of

dogs into their own mouths, and then boasting of it.

"Tell the Mīr that thou hast, within thy skin, a dog and a

carcass.

"A dog runs about in front of the house; don't make him a messmate.

"The ceremonial ablution after emission of semen

was no longer considered binding, and people quoted as proof that the essence

of man was the sperma genitale, which was the origin of good and bad men.

It was absurd that voiding urine and excrements should not require ceremonial

ablutions, whilst the emission of so tender a fluid should necessitate ablution;

it would be far better, if people would first bathe, and then have connexion.

"Further, it was absurd to prepare a feast in honour of a dead person; for the

corpse was mere matter, and could derive no pleasure from the feast. People

should therefore make a grand feast on their birth-days.

Such feasts were called Āsh-i ḥayāt, food of life.

"The flesh of the wild boar and the tiger was also permitted, because the

courage which these two animals possess, would be transferred to any one who fed

on such meat.

"It was also forbidden to marry one's cousins or near relations, because such

marriages are destructive of mutual love. Boys were not to marry before the age

of 16, nor girls before 14, because the offspring of early marriages was weakly.

The wearing of ornaments and silk dresses at the time of prayer was made

obligatory.

"The prayers of the Islām, the fast, nay even the

pilgrimage, were henceforth forbidden. Some bastards, as the son of Mullā

Mubārak, a worthy disciple of Shaykh Abū'l-Fazl, wrote treatises, in order to revile and ridicule our religious

practices, of course with proofs. His Majesty liked such productions, and

promoted the authors.

"The era of the Hijrah was now abolished, and a new era was

introduced, of

which the first year was the year of the emperor's accession (963). The months

had the same names as at the time of the old Persian kings, and as given in the

Niṣābu'ṣ-ṣibyān.

Fourteen festivals also were [S. 205] introduced corresponding to the feasts of the

Zoroastrians; but the feasts of the Musalmāns and their glory were

trodden down, the Friday prayer alone being retained, because some old, decrepit,

silly people

used to go to it. The new era was called Tārīkh-i Ilāhī, or

'Divine Era.'

On copper coins and gold muhurs, the era of the Millenium

was used, as indicating that the end of the religion of Muḥammad, which was to

last one thousand years, was drawing near. Reading and learning Arabic was

looked upon as a crime; and Muhammedan law, the exegesis of the Qur'ān, and the

Tradition, as also those who studied them, were considered bad and deserving of

disapproval. Astronomy, philosophy, medicine, mathematics, poetry, history, and

novels, were cultivated and thought necessary. Even the letters which are

peculiar to the Arabic language, as the ض ص ح ع ث, and

ظ, were avoided.

Thus for

"All this pleased

His Majesty. Two verses from the Shāhnāma, which Firdausī gives as part of a

story, were frequently quoted at court—

From eating the flesh of camels and lizards

The Arabs have made such progress,

That they now wish to get hold of the kingdom of Persia.

Fie upon Fate! Fie

upon Fate!

"Similarly other verses were eagerly seized, if they conveyed a calumny, as

the verses from the ……, in which the falling out of the teeth of our prophet is alluded to.

"In the same manner, every doctrine and command of the Islām, whether special

or general, as the prophetship, the harmony of the Islām with reason, the

doctrines of Ru'yat, Taklīf, and Takwīn,

the details of the day of resurrection and judgment,—all were doubted and

ridiculed. [S. 206] And if any one did object to this mode of arguing, his answer was not

accepted. But it is well known how little chance a man has who cites proofs

against one who will reject them, especially when his opponent has the power of

life and death in his hands; for equality in condition is a sine qua non

in arguing.

A man who will not listen, if you bring the Qur'ān and the Tradition,

Can only

be replied to by not replying to him.

"Many a family was ruined by these discussions. But perhaps

'discussions '

is

not the correct name; we should call them meetings for arrogance and

defamation. People who sold their religion, were busy to collect all kinds of

exploded errors, and brought them to His Majesty, as if they were so many

presents. Thus Laṭīf Khwājah, who came from a noble family in Turkistān, made a

frivolous remark on a passage in Tirmizī's Shamā'il,

and asked how in all the world the neck of the prophet could be compared to the

neck of an idol. Other remarks were passed on the straying camel.

Some again expressed their astonishment, that the prophet, in the beginning of

his career, plundered the caravans of Quraysh; that he had fourteen wives; that

any married woman was no longer to belong to her husband, if the prophet thought

her agreeable, &c. At night, when there were social assemblies, His

Majesty told forty courtiers to sit down as 'The Forty',

and every one might say or ask what he liked. If then any one brought up a

question connected with law or religion, they said, "You had better ask the Mullās about that, as we only settle things which appeal to man's reason." But

it is impossible for me to relate the blasphemous remarks which they made about

the Ṣahābah, when historical books happened to be read out, especially

such as contained the reigns of the first three Khalīfahs, and the quarrel about

Fadak, the war of Ṣiffīn,

&c.,—would that I were [S. 207] deaf! The Shī'ahs, of course, gained the day, and the

Sunnīs were defeated; the good were in fear, and the wicked were secure. Every

day a new order was given, and a new aspersion or a new doubt came up; and His

Majesty saw in the discomfiture of one party a proof for his own infallibility,

entirely forgetful of the proverb, 'Who slanders others, slanders himself.'

The ignorant vulgar had nothing on their tongues but 'Allāhu Akbar', and

they looked upon repeating this phrase, which created so much commotion, as a