Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Chronik Thailands = กาลานุกรมสยามประเทศไทย. -- Chronik 1854 (Rama IV.). -- Fassung vom 2016-11-28. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/chronik1854.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2013-07-10

Überarbeitungen: 2016-11-28 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-09-02 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-04-22 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-02-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-06-18 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-04 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-10-21 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-11-06 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-10-06 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-07-12 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Herausgebers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Thailand von

Tüpfli's Global Village Library

ช้างตายทั้งตัวเอาใบบัวปิดไม่มิด

|

Gewidmet meiner lieben Frau Margarete Payer die seit unserem ersten Besuch in Thailand 1974 mit mir die Liebe zu den und die Sorge um die Bewohner Thailands teilt. |

|

Bei thailändischen Statistiken muss man mit allen Fehlerquellen rechnen, die in folgendem Werk beschrieben sind:

Die Statistikdiagramme geben also meistens eher qualitative als korrekte quantitative Beziehungen wieder.

|

1854 - 1879

Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin Mukarram Shah ist Sultan (سلطان) von Kedah (قدح). Zuvor gibt es Thronstreitigkeiten und beinahe einen Bürgerkrieg, da der Schwiegersohn des verstorbenen Sultans die Macht übernehmen wollte. Mit der Unterstützung einflussreicher Fürsten wird der Sohn des verstorbenen Sultans als Sultan eingesetzt. Siam entscheidet sich für ihn. Sultan Ahmad Tajjudin hält gute Beziehungen zu Großbritannien und Siam und bringt Kedah innere Stabilität. Da die Anzahl der chinesischen Händler in Kedah zunimmt, ernennt Sultan Ahmad den Händler Ah Seng (阿成) zum Kapitan China (華人甲必丹). Der Sultan lässt von Bauern in Fronarbeit eine 110 km lange Straße aus Zentral-Kedah zur Grenze Siams bauen.

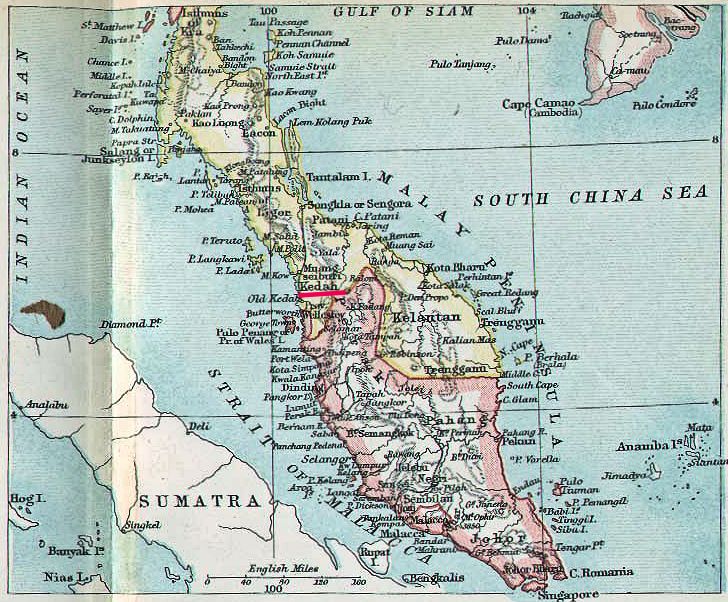

Abb.: Lage von Kedah (قدح)

[Bildquelle: Constables Hand Atlas of India, 1893. -- Pl. 59]

1854

Der König gibt den Haremsdamen, die keine Kinder haben, das Recht, das Harem zu verlassen und zu heiraten:

"His Majesty King Phra Chom Klao is graciously pleased to pledge His Royal Permit, bound in truth and veracity, to all Lady Consorts serving in the Inner Palace, Middle Palace and Outer Palace, excepting Mother Consorts of the royal children, as well as to Forbidden Ladies of all ranks, Ladies Chaperon and Chaperons and all Palace Dancers and Concubines as follows: Whereas it is no longer the desire of His Majesty to possess, by means of threat or detention, any of the ladies above referred to, and, having regards to the honour of their families and their own merits, it has been His Majesty’s pleasure to support them and to bestow on them annuities, annual gifts of raiment and various marks of honour and title befitting their station.

Should any of the ladies, having long served His Majesty, suffer discomfort, and desire to resign from the Service in order to reside with a prince or to return home to live with her parents, or to dispel such discomfort by the company of a private husband and children, let her suffer no qualms. For if a resignation be directly submitted to His Majesty by the lady accompanied by the surrender of decorations, her wishes will be graciously granted, provided always that whilst still in the Service and before submitting such a resignation, the lady shall refrain from the act of associating herself with love agents, secret lovers or clandestine husbands by any means or artifice whatsoever. . . .

The Mother Consorts of the Royal Children can in no case be permitted to resign in favour of matrimony because such an action will prejudice the dignity of the royal children. In this case resignation is only permissible if the purpose is restricted to residence with the royal children unaccompanied by matrimony.

The said royal intention, in spite of repeated declarations to the same effect as above stated, seems to make little progress with popular credence, it being mistaken as a joke or a sarcastic remark. Since in truth and veracity His Majesty bears such an intention in all earnestness, His Pledge is hereby doubly reattested by being declared and published for public perusal. Such a course of action has been taken in order that all manner of men and women will be completely reassured that His Majesty harbours no possessive desire in regards to the ladies, nor does he intend to detain them by any means whatsoever, and that previous declarations do represent His true and sincere purpose."

[Zitiert in: Moffat, Abbot Low <1901 - 1996>: Mongkut, the king of Siam. -- Ithaca N.Y. : Cornell UP, 1961. -- S. 150f.]

1854

Brief des Königs an die Haremsdame Lady Phung:

"My own Turtle," he wrote, "this is to show how much and truly I am thinking of you. I left the Water Palace last Sunday before dawn and arrived at Wat Khema [วัดเขมาภิรตารามราชวรวิหาร] in Talat Kwan [ตลาดขวัญ, heute: Mueang Nonthaburi - เมืองนนทบุรี] at about 7 o’clock in the morning.

Abb.: Lage von Wat Khema [วัดเขมาภิรตารามราชวรวิหาร]

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]There, we noticed a very fast boat which was being paddled at full speed towards the Royal Barge. At that moment it had already passed the boats carrying the guards and all the other boats in the retinue. It gained upon us, and finally it caught up with the Royal Barge and was actually running parallel to it. At first I thought that Ramphoey’s (Princess Ramperi Bhamarabhirama [รำเพยภมราภิรมย์], who became Queen Debserin [เทพศิรินทรา]) little girl was in the boat, possibly crying to be put in the Royal Barge so as to be with me, and that they were trying to do so to please her. I shouted at them to inquire whose boat it was, but there was no answer. The cabin of the boat was heavily curtained and many women were to be seen in the stern. The guards told me later that they thought the boat had come in the retinue and therefore they had not stopped it at the beginning. My Chamberlain, Sarapeth, challenged it many times; I myself repeated my question again and again, but instead of any reply, the women in the boat all laughed merrily and with the utmost abandon, so that the people in my barge were getting quite annoyed for being laughed at.

I thought of ordering my men to open fire according to the Law; but on second thought I was afraid someone might be shot dead. It would then be said that I was a cruel and irresponsible Monarch, to have caused death to people so easily.

By now the boat was having a race with the Royal Barge itself. This went on for some time until I thought it was really out of the ordinary and had to be stopped. Only then did I order the guards to give chase and stop the boat. They had to chase it for quite a distance before they could bring it back. It was found that the boat belonged to Prince Mahesavara’s mother [Prince Mahesavara was the King’s eldest son, born before he entered the priesthood] and she herself was in it. She appeared to be in a brazenly playful mood and had a most unseemly desire to tease me in public. I ordered Phra Indaradeb to take the boat down to Bangkok. I have also ordered the owner of the boat to be held within the Inner Palace, while all her servants who were with her were to be kept in custody. I have written to inform her son of the incident, and have given my instructions to the Ladies Sri Sachcha and Sobhanives accordingly.

I have heard that some women with connections to Princess Talap and Princess Haw were in that boat. These two women are related to your aunt. Do not go and see them or say anything to them, for they would only be rude to you and make you ashamed. The chief culprit does not acknowledge her own wantonness. She still regards herself as my favorite and would follow me just to ridicule me in front of my new young wives. She claims to be a great lady, for when she was arrested she cried out that she intended to accompany me to Ayuthia [อยุธยา].

I have sent you five hives of honey. You may call for them at Lady Num’s. Should honey disagree with you in your present state, so soon after child-birth, do not eat it but give it to your mother or to your aunt. Will you all take good care of my child? I am worried about his health and do not want him to be ill. I have asked Prince Sarpasilp to keep an eye on him also.

The water level is very high this year. Beyond the Royal Pavilion there is a great expanse of water. It is full of lotus, water lilies and water chestnuts. Those who have accompanied me here cannot contain themselves for the desire to go out boating. This they can already do at the back of the pavillion within camp. Everything is as it should be at present. Princess Pook, by being absent, is not able to make a nuisance of herself as usual. There has been only one accident so far; a golden receptacle is lost. It has probably fallen into the water when one of the boats carrying my servants was sunk to-day in a collision with another boat. They are diving for it now, but I am not so sure whether it will be found.

I have told Lady Num to give you also some pressed new rice, but as I have sent this present to a number of other people as well, you may have to take your share of it only."

[Zitiert in: Moffat, Abbot Low <1901 - 1996>: Mongkut, the king of Siam. -- Ithaca N.Y. : Cornell UP, 1961. -- S. 145ff.]

1854

Khaw Soo Cheang (Kaw Sujiang / Xu Sizhang / 许泗章 / คอซูเจียง, 1797-1882) wird Gouverneur von Ranong (ระนอง). Khaw hatte in Ranong Zinnvorkommen entdeckt und hatte von Rama den Titel Phraya Ratanasetthi (พระยารัตนเศรษฐี) und das Monopol für Zinnabbau in Ranong erhalten.

Abb.: Lage von Ranong (ระนอง)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"The Khaw (許 / คอ) family The Khaw (許 / คอ) family is very important in the history of Ranong (ระนอง).

Khaw Soo Cheang (许泗章 / คอซูเจียง, 1797-1882) was a Chinese immigrant from Zhangzhou (漳州), Fujian Province (福建). He was an officer of the "Small Knives Secret Society", which was fighting to restore the Ming Dynasty (大明). His other name was Khaw Teng Hai, and his alias was Khaw Soo Cheang. In 1810 he arrived in Penang, staying in Sungai Tiram about 1 kilometer from the present Bayan Lepas International Airport, where he was a small-scale vegetable farmer. Once a week Khaw Soo Cheang took his produce to Jelutong to sell.

Khaw Soo Cheang eventually started a small sundries shop under the name of Koe Guan. He started trading along the coast of southern Thailand.

Khaw Soo Cheang had six sons:

- Khaw Sim Cheng (คอซิมเจ่ง),

- Khaw Sim Kong (คอซิมก๊อง),

- Khaw Sim Chua (คอซิมจั๊ว),

- Khaw Sim Khim (คอซิมขิม),

- Khaw Sim Teik (คอซิมเต๊ก), and

- Khaw Sim Bee (許心美 / คอซิมบี้, 1857 - 1913).

Sim Cheng is believed to have been born to his China wife. Sim Kong, Sim Chua, Sim Khim and Sim teik were sons of second wife Sit Kim (กิม) Lean, who is buried in Ranong. The youngest was born one of his numerous Thai minor wives.

Khaw Soo Cheang diversified into tin mining, shipping and hiring immigrant labourers. In 1844, he was appointed the Royal Collector of tin royalties in the Ranong, and receiving the royal title Luang Ratanasethi (หลวงรัตนเศรษฐี). In 1854 King Rama IV Mongkut made him governor of Ranong and elevated him to the higher noble rank of Phra (พระ). Ranong was then subordinate to Chumphon province (ชุมพร), but in 1864 it was elevated to full provincial status. Khaw Soo Cheang thus was raised to be a Phraya (พระยา). He successfully defended the new province against invasion by Burma, whhich sought to annex it for its tin deposits. The Khaw family became close to the Thai royal court, especially with Prince Damrong Rajanubhab (สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ พระองค์เจ้าดิศวรกุมาร กรมพระยาดำรงราชานุภาพ, 1862 - 1943), who stayed at the family's home in Penang, named Chakrabong (จักรพงศ์ ) in honour of the Thai royal family. in 1872, Khaw Soo Cheang, then 81 years old, returned to China where he married an 18-year-old wife. Prior to the voyage he made his will. However, he lived another 10 years.

The eldest son, Khaw Sim Cheng (คอซิมเจ่ง), died before his father.

The second son, Khaw Sim Kong (คอซิมก๊อง), succeeded him as governor of Ranong in 1874. In 1896 Sim Kong became commissioner of the Monthon of Chumphon (มณฑลชุมพร).

His fourth son, Sim Khim (คอซิมขิม), became governor of Kraburi (กระบุรี),

and the fifth son, Sim Teik (คอซิมเต๊ก), became governor of Lang Suan (หลังสวน).

Khaw Sim Bee (許心美 / คอซิมบี้, 1857 - 1913), the youngest son, Ratsadanupradit Mahison Phakdi (พระยารัษฎานุประดิษฐ์มหิศรภักดี) became governor of Trang (ตรัง), and in 1900 was commissioner of Monthon Phuket (มณฑลภูเก็ต).

The Khaw family founded a steamship company known as the Eastern Shipping Company. They also formed the Eastern Trading Company which they tried unsuccessfully to list on the stock exchange. Their business empire also included Tongkah Harbour, the first Asian company involved in dredging the harbor floor for tin (a publicly listed company). The Penang branch of the family were also one of the founders of an insurance company known as Khean Guan Insurance .

In his will dated 1872 Khaw Soo Cheang divided his estate into 16 parts, of which 15 parts were distributed to his descendants. One-sixteenth was used to set up Koe Guan Kong Lun, the family trust, which came into existence in 1905. Under the terms of the Trust Deed, 21 years after the death of the last person whose name appeared in the deed the would be inherit it. The last person was his great-grandson Khaw Bian Ho, who died on October 21, 1972. Twenty-one years later, on October 21, 1993, the Trust was vested, and the Trustees began the process of ending Koe Guan Kong Lun. Khaw Soo Cheang, who gave up his position as Governor of Ranong in 1874, arranged for his second son Khaw Sim Kong to lead the family enterprise in Thailand. His fourth son Khaw Sim Khim took managed and led the family interests in Penang until his death in 1903.

After the death of Khaw Sim Bee in 1913, a commissioner from outside the area was appointed to by the government end the traditionally inherited administrative power of the family. The family essentially divided into the Malaysian and Thai branches. In 1932 all Chinese immigrants and their descendants had to adopt a Thai family name after the military coup ended the absolute monarchy. The Thai monarch had already bestowed the name Na Ranong (ณ ระนอง - "from Ranong") on Khaw Soo Cheang's descendants in Thailand. In Malaysia and elsewhere they are still known as the Khaw family.

Khaw Soo Cheang, Khaw Sim Kong. Khaw Sim Teik and Khaw Sim Bee's tombs are today located in Ranong. The tombs of Khaw Sim Khim is located in Batu Lanchang Chinese cemetery in Penang while Khaw Sim Chua, who had no sons, is purportedly buried off Kampar Road in Penang. Today the male lines of the eldest son Sim Cheng and the third son Sim Chua are extinct.

Today the only vestige of his presence in Penang is the Penang state hall known as Dewan Sri Pinang which sits on the land known as Ranong grounds which was given by the Khaw family to the then government of the day in gratitude for the opportunities. The houses where the Khaw family resided on the famous millionaires' road Northam Road such as Asdang, Chakrabong and the house owned by Khaw Sim Khim opposite the old Shih Chung school besides No 32, have all been sold and demolished and no longer remain in the hands of the family."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ranong_Province. -- Zugriff am 2015-02-23]

1854

Der US-Baptistenmissionar Dan Beach Bradley (1804 - 1873) schenkt Rama IV. ein Set künstlicher Zähne. Der König hatte schon während seiner Mönchszeit alle Zähne verloren. Die Zähne des Unterkiefers waren durch Zähne aus Sapan-Holz (Caesalpinia sappan) ersetzt worden. Die von Bradley geschenkten Zähne scheinen keinen Erfolg zu haben.

1854

In Paris erscheint das erste (polyglotte: siamesich - lateinisch - französisch - englisch) Thai-Wörterbuch:

Pallegoix, Jean-Baptiste, <1805-1862>: สัพะ พะจะนะ พาสาไท [sic!] = Dictionarium linguae thai sive siamensis interpretatione latina, gallica et anglica -- Paris: Typographeum imperatorium, 1854. -- 897 S. ; 27 cm.

Abb.: Titelblatt

Abb.: Bischof Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix (1805 - 1862)

1854

In Paris erscheint:

Pallegoix, Jean-Baptiste <1805 - 1862>: Description du Royaume Thai ou Siam : comprenant la topographie, histoire naturelle, moeurs et coutumes, legislation, commerce, industrie, langue, littérature, religion, annales des Thai et précis historique de la mission : avec cartes et gravures. -- Paris : Au profit de la mission de Siam, 1854. -- 2 Bde : Ill. ; 19 cm.

Abb.: Titelblatt

Abb.: Karte Siams von Bischof Pallegoix

[a.a.O., Bd. I, Anlage]

Abb.: Stadtplan Bangkoks auf Karte Siams von Bischof Pallegoix

1854

Es erscheint:

Rufus Hill : The missionary child in Siam / a memoir written by his mother, now in America. -- Philadelphia : American Sunday School Union, 1854. -- 72 S. -- Eine sehr lesenswerte Sonntagsschul-Geschichte voll von missionarischem Selbsmitleid.

Abb.: Titelblatt und Frontispiece

1854

Ein US-Mormonen-Missionar weilt vier Monate in Bangkok. Da die Siamesen aber schon Vielweiberei haben, findet er wenig Anklang.

1854/1855

Von Siam segeln 11 Handelsschiffe mit Rahsegeln nach China.

1854 - 1873

Miao Rebellion: Rebellion der Meo / Hmong (แม้ว / ม้ง / Mèo / H'Mông / 苗族) und anderer in der chinesischen Provinz Guizhou (贵州省). Die Rebellion wird niedergeschlagen. Flucht vieler Meo / Hmong nach Laos.

Abb.: Lage von Guizhou (贵州省)

[Bildquelle: CIA. -- Public domain]

"The Miao Rebellion of 1854 - 1873 was an uprising of ethnic Miao (แม้ว / ม้ง / Mèo / H'Mông / 苗族) in Guizhou (贵州省) province during the reign of the Qing dynasty (大清). The uprising was preceded by Miao rebellions in 1735-36 and 1795-1806, and was one of many ethnic uprisings sweeping China in the 19th century. The rebellion spanned the Xianfeng (咸豐帝) and Tongzhi (同治帝) periods of the Qing dynasty, and was eventually suppressed with military force. Estimates place the number of casualties as high as 4.9 million out of a total population of 7 millions, though these figures are likely overstated.[1] The rebellion stemmed from a variety of grievances, including long-standing ethnic tensions with Han Chinese, poor administration, grinding poverty and growing competition for arable land.[1] The eruption of the Taiping Rebellion (太平天国) led the Qing government to increase taxation, and to simultaneously withdraw troops from the already restive region, thus allowing a rebellion to unfold.

The term "Miao" does not mean only the antecedents of today's Miao national minority; it is much more general term, which had been used by the Chinese to describe various aboriginal, mountain tribes of Guizhou and other southwestern provinces of China, which shared some cultural traits.[2] They consisted of 40-60% population of the province."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miao_Rebellion_%281854%E2%80%9373%29. -- Zugriff am 2013-11-04]

1854

Stapellauf des japanischen Kriegsschiffs Shouhei-Maru ( 昇平丸). Sie ist ein japanischer Nachbau nach niederländischen Zeichnungen.

Abb.: Shouhei-Maru ( 昇平丸), ca. 1855

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

1854

Der englische Arzt John Snow (1813 - 1858) erkennt, dass sich Cholera durch verschmutztes Trinkwasser ausbreitet. Seine bahnbrechende Erkenntnis bleibt zunächst unbeachtet.

Abb.: Karte, mit der John Snow zeigt, dass die Cholera in London 1854 von bestimmten Brunnen ausgeht

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

1854

Die Niederlande beginnen auf Java (Nederlands-Indië / Hindia-Belanda) mit dem Anbau von Chinarindenbäume (Cinchona). Die Samen waren aus Südamerika geschmuggelt wiorden. Chinariindenbäume sin die Liferanten von Chinin, dem damaligen besten Mittel gegen Malaria. 1918 werden die Niederlande weltweit der Hauptproduzent von Chinin sein. Malaria ist eine der Hauptkrankheiten Siams.

Abb.: Chinarinde

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1854

Es erscheint:

Gorrie, John <1803 - 1855>: Dr. John Gorrie's apparatus for the artificial production of ice, in tropical climates : patented, 1851. -- New York : Maigne & Wood, 1854. -- 15 S. : 1 Ill. -- Die Maschine ist der Vorläufer aller Kühlmaschinen und Kühlschränke.

Abb.: Dr. John Gorrie's ice machine (a.a.O.)

1854

Es erscheint das rassentheoretische Werk:

Nott, Josiah Clark <1804-1873> ; Gliddon, George R. (George Robins) <1809 - 1857>: Types of mankind : or, Ethnological researches : based upon the ancient monuments, paintings, sculptures, and crania of races, and upon their natural, geographical, philological and biblical history, illustrated by selections from the inedited papers of Samuel George Morton [1799-1851] and by additional contributions from L. Agassiz [1807 - 1873], W. Usher, and H.S. Patterson [1815 - 1854]. -- Philadelphia : Lippincott, Grambo, 1854. -- 738 S. : Ill. ; 28 cm

Abb.: Titelblatt

Abb.: a.a.O., S. 458

1854

Der Amerikaner Elisha Graves Otis (1811 - 1861) erfindet den "safety elevator", den ersten sicheren Personenaufzug.

Abb.: Otis-Aufzug, Glasgow, 1856

[Bildquelle: Zeddy / Wikipedia. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1854-01 - 1854-05

Dritter Kengtung-Krieg (ၵဵင်းတုင် - เชียงตุง)

Abb.: Lage von Kentung (ၵဵင်းတုင် - เชียงตุง)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]Die Kämpfe dauern 24 Tage, dann sind Munition und Versorgung der siamesischen Truppen aufgebraucht. Rama IV. beschließt die Kengtung-Kriege zu beenden.

Bericht Ramas IV. an Sir John Bowring (1792 - 1872) über diesen Kengtung-Krieg:

"Account of the attack upon Chiangtoong: The city of Chiangtoong [เชียงตุง / ၵဵင်းတုင်] being still unsubdued at the end of the campaign of last year, the army went into quarters for the rainy season at Muang Nan [เมืองน่าน], a Laos great town, situated in latitude 18°20' North. Here they remained some eight months, when, the rains being fairly over, on the 15th of January last (1854), his Royal Highness Krom Hluang Wongsa Dhiraj Snidh [กรมหลวงวงษาธิราชสนิท, 1808-1871], the Commander-in-chief , with all his forces, left Muang Nan, and, after a twenty days’ march, arrived at Chiangrai [เชียงราย], a town on the extreme northern frontiers of the Siamese territories. Here he remained one month, awaiting the coming up of the troops, collecting, in the mean time, stores of provisions, supplies &c.

Abb.: Lage von Muang Nan [เมืองน่าน] und Chiang Rai [เชียงราย]

[Bildquelle: CIA. -- Public domain]On the 25th of February, the army resumed their march, proceeding in two divisions and by different roads; his Excellency Chau Phaya Yomerat [เจ้าพระยายมราช], with one division, advancing by way of Sisapong, and his Royal Highness Krom Hluang Wongsa Dhiraj Snidh by way of Muang Yong, Palao, Chiangrai [เชียงราย], and Chiangkaung [Chiang Khong - เชียงของ], fighting with the Chiangtoong defending forces in all these places as they proceeded. Calculating upon receiving supplies of provisions from the towns they were to pass on their route, and failing to do so, their stock fell short: the elephants and bullocks that transported the stores of the army failed, too, to come up in time to furnish what was required for the daily rations. Hence the necessity of delaying in each place —sometimes for several days — to wait the coming up of the provisions; and also in making conciliations and arrangements so as to enable the Lao Lu [ลาวลื้อ = ไตลื้อ], or people of Chiangroong [เชียงรุ้ง], to convey stores and provisions to Muang Luc, within the boundaries of the province of Chiangroong, many days and nights were lost. After entering the province of Chiangtoong, they found the Mhakanan [Sao Maha Hkanan, 1781 - 1857] or chief of Chiangtoong, being aware that a Siamese army was coming to march into and attack his country, had compelled the inhabitants to remove their families from all the villages and towns that lay in the route of the invading army, and burn up all the rice and food of every description in them, leaving only the able-bodied men in the towns to defend them. And then, again, the roads proved very difficult. There being very many mountains to climb, and very little level ground, it was impossible for baggage-carts to be used — so the only means of transportation were elephants and bullocks: consequently, but a small quantity or portion of the mortars, howitzers, field-pieces, shot, shell, and powder could be taken along with the army. By the time the army had arrived at Muang Gnuum, Muang Ping [Mong Ping], and Muang Samtan, they had fought with, driven back, and put to rout the Chiangtoong troops — so that the van of the Siamese army were enabled to advance quite up to the very walls of Chiangtoong itself by the 26th of April. The main body, however, under his Royal Highness Krom Hluang Wongsa Dhiraj Snidh, established themselves at Muang Lek, a village about three miles’ distance from the city wall.

The city of Chiangtoong is accessible only by defiles through the mountains that surround it; but at all of these they had built up walls wherever the natural mountain barriers were deficient. An area of about twelve miles in circumference was enclosed by these walls. The town was garrisoned by about three thousand Burmese troops, besides the soldiers of Chiangtoong itself, who numbered about seven thousand men; Ngiaos people, about six thousand more; making the whole number about sixteen thousand fighting men.

The Chiangtoong men came out from the city frequently to attack the Siamese forces, when the Siamese would open on them a fire of shells from their mortars, by which very many of the enemy would be killed. Upon this, the enemy would retreat within their walls, soon to come out again to resume the contest; and thus an incessant conflict was kept up with the Siamese army for twenty-one days. On the side of the Chiangtoong forces, many hundreds were slain; on the part of the Siamese, about fifty or sixty men.

While the Siamese were designing to carry on the war yet more, the rains set in heavily, and the supplies began to grow short: disease, too, broke out among the soldiers a dysentery carrying off several hundreds of them. Among the elephants also (of which there were with the army over a thousand) a distemper appeared with the coming on of the rainy season, in consequence of which near about five hundred of them died. The elephants and bullocks that were conveying the provisions and military stores did not arrive in time. Moreover, the division of the army under Chau Phaya Yomerat, which was to have advanced upon Chiangtoong by way of Sisapong in the Muang-rai country, became greatly destitute of provisions, and was unable to get through, as the route they took abounded with difficult mountain-passes, declivities, precipices, &c., so that the troops and elephants were obliged to proceed in single file: and besides, a fatal disease broke out among the people and elephants, of which many died. For these reasons, it became necessary, by the 17th of May, to withdraw the army from the city of Chiangtoong, and fall back to Chiangsen [Chiang Saen - เชียงแสน] and Chiangrai.

Abb.: Lage von Muang Nan (เมืองน่าน), Chiang Rai (เชียงราย), Chiang Saen (เชียงแสน), Chiang Khong (เชียงของ) und Kengtung (ၵဵင်းတုင် - เชียงตุง), ca. 1940

[Bildquelle: http://research.humancomp.org/wadict/maps/burma_old_map_shan_states.jpg. -- Zugriff am 2015-03-26. -- Fair use]The army could again, in the succeeding year, return to take satisfaction from the people of Chiangtoong; but since both the troops and their horses, elephants and bullocks, were worn out with fatigue, there is now a necessity to cease awhile from hostilities, in order to give the soldiers an opportunity to rest, also to arrange for and lay in abundant stores for the subsistence of the troops. Perhaps at some future time an army will be marched to chastise these Chiangtoong people, and finish up this affair."

[Zitiert in: Manich Jumsai [มานิจ ชุมสาย] <1908 - 2009> ; Monkut <König, Siam> [พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรเมนทรมหามงกุฎ พระจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว] <1804 - 1868> ; Bowring, John <1792 - 1872>: King Mongkut and Sir John Bowring (from Sir John Bowring's personal files, kept at the Royal Thai Embassy in London). -- Bangkok, Chalermnit, 1970. -- 240 S. : Ill. ; 27 cm. -- S. 231ff.]

1854-03

Bildung des Colonial Office in London. Es ist zuständig für die britischen Kolonien, nicht aber für Indien (India Office). Seit 1801 war das War and Colonial Department für die Kolonien zuständig gewesen.

1854-03-31

Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794 - 1858) erzwingt den Vertrag von Kanagawa (神奈川条約): danach muss Japan den USA die beiden Häfen Shimoda (下田市) und Hakodate (函館市) für den Handel öffnen.

Abb.: Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (Mitte)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Lage von Kanagawa (神奈川条約), Shimoda (下田市) und Hakodate (函館市)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Kanagawa, March 31, 1854.

Treaty between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan. THE UNITED STATES of America and the Empire of Japan, desiring to establish firm, lasting, and sincere friendship between the two nations, have resolved to fix, in a manner clear and positive, by means of a treaty or general convention of peace and amity, the rules which shall in future be mutually observed in the intercourse of their respective countries; for which most desirable object the President of the United States has conferred full powers on his Commissioner, Matthew Calbraith Perry, Special Ambassador of the United States to Japan, and the August Sovereign of Japan has given similar full powers to his Commissioners . . . . . . And the said Commissioners, after having exchanged their said full powers, and duly considered the premises, have agreed to the following articles:

ARTICLE 1. There shall be a perfect, permanent, and universal peace, and a sincere and cordial amity between the United States of America on the one part, and the Empire of Japan on the other part, and between their people respectively, without exception of persons or places.

ARTICLE II. The port of Simoda [in Yedo harbor], in the principality of Idzu, and the port of Hakodade, in the principality of Matsmai [Hokkaido], are granted by the Japanese as ports for the reception of American ships, where they can be supplied with wood, water, provisions, and coal, and other articles their necessities may require, as far as the Japanese have them. The time for opening the first-named port is immediately on signing this treaty; the last- named port is to be opened immediately after the same day in the ensuing Japanese year.

NOTE. A tariff of prices shall be given by the Japanese officers of the things which they can furnish, payment for which shall be made in gold and silver coin.ARTICLE Ill. Whenever ships of the United States are thrown or wrecked on the coast of Japan, the Japanese vessels will assist them, and carry their crews to Simoda, or Hakodade, and hand them over to their countrymen, appointed to receive them; whatever articles the shipwrecked men may have preserved shall likewise be restored, and the expenses incurred in the rescue and support of Americans and Japanese who may thus be thrown upon the shores of either nation are not to be refunded.

ARTICLE IV. Those shipwrecked persons and other citizens of the United States shall be free as in other countries, and not subjected to confinement, but shall be amenable to just laws.

ARTICLE V. Shipwrecked men and other citizens of the United States, temporarily living at Simoda and Hakodade, shall not be subject to such restrictions and confinement as the Dutch and Chinese are at Nagasaki, but shall be free at Simoda to go where they please within the limits of seven Japanese miles . . . from a small island in the harbor of Simoda marked on the accompanying chart hereto appended; and in shall like manner be free to go where they please at Hakodade, within limits to be defined after the visit of the United States squadron to that place.

ARTICLE VI. If there be any other sort of goods wanted, or any business which shall require to be arranged, there shall be careful deliberation between the parties in order to settle such matters.

ARTICLE VII. It is agreed that ships of the United States resorting to the ports open to them shall be permitted to exchange gold and silver coin and articles of goods for other articles of goods, under such regulations as shall be temporarily established by the Japanese Government for that purpose. It is stipulated, however, that the ships of the United States shall be permitted to carry away whatever articles they are unwilling to exchange.

ARTICLE VIII. Wood, water, provisions, coal, and goods required, shall only be procured through the agency of Japanese officers appointed for that purpose, and in no other manner.

ARTICLE IX. It is agreed that if at any future day the Government of Japan shall grant to any other nation or nations privileges and advantages which are not herein granted to the United States and the citizens thereof, that these same privileges and advantages shall be granted likewise to the United States and to the citizens thereof, without any consultation or delay.

ARTICLE X. Ships of the United States shall be permitted to resort to no other ports in Japan but Simoda and Hakodade, unless in distress or forced by stress of weather.

ARTICLE XI. There shall be appointed, by the Government of the United States, Consuls or Agents to reside in Simoda, at any time after the expiration of eighteen months from the date of the signing of this treaty, provided that either of the two Governments deem such arrangement necessary.

ARTICLE XII. The present convention having been concluded and duly signed, shall be obligatory and faithfully observed by the United States of America and Japan, and by the citizens and subjects of each respective Power; and it is to be ratified and approved by the President of the United States, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate thereof, and by the August Sovereign of Japan, and the ratification shall be exchanged within eighteen months from the date of the signature thereof, or sooner if practicable.

In faith whereof we, the respective Plenipotentiaries of the United States of America and the Empire of Japan aforesaid, have signed and sealed these presents.

Done at Kanagawa, this thirty-first day of March, in the year of our Lord Jesus Christ one thousand eight hundred and fifty-four . . . . .

M. C. PERRY. (HERE FOLLOW THE SIGNATURES OF THE JAPANESE PLENIPOTENTIARIES)亞米利加合衆國ト帝國日本兩國の人民誠實不朽の親睦を取り結ひ兩國人民の交親を旨とし向後可守箇條相立候ため合衆國より全權マッゼウ、カルブレズ、ペルリ(人名)を日本に差越し日本君主よりは全權林大學頭井戶對馬守伊澤美作守鵜殿民部少輔を差遣し勅諭を信して雙方左の通取極候 第一條 日本と合衆國とは其人民永世不朽の和親を取結ひ場所人柄の差別無之事

第二條 伊豆下田松前箱館の兩港は日本政府に於て亞墨利加船薪水食料石炭欠乏の品を日本人にて調候丈は給し候爲め渡來の儀差免し候尤下田港は約條書面調印の上卽時開き箱館は來年三月より相始候事

第三條 合衆國の船日本海濱漂着の時扶助致し其漂民を下田又は箱館に護送致し本國の者受取可申所持の品物も同樣に可致候尤漂民諸雜費は兩國互に同樣の事故不及償候事

第四條 漂着或は渡來の人民取扱の儀は他國同樣緩優に有之閉籠候儀致間敷乍併正直の法度には伏從致し候事

第五條 合衆國の漂民其他の者共當分下田箱館逗留中長崎に於て唐和蘭人同樣閉籠窮屈の取扱無之下田港內の小島周り凡七里の內は勝手に徘徊いたし箱館港の儀は追て取極候事

第六條 必用の品物其外可相叶事は雙方談判の上取極候事

第七條 合衆國の船右兩港に渡來の時金銀錢並品物を以て入用の品相調候を差免し候尤日本政府の規定に相從可申且合衆國の船より差出候品物を日本人不好して差返候時は受取可申事

第八條 薪水食料石炭並缺乏の品求る時には其地の役人にて取扱すへく私に取引すへからさる事

第九條 日本政府外國人へ當節亞墨利加人へ不差許候廉相許し候節は亞墨利加人へも同樣差許可申右に付談判猶豫不致候事

第十條 合衆國の船若し難風に逢さる時は下田箱館兩港の外猥に渡來不致候事

第十一條 兩國政府に於て無據儀有之候時は模樣に寄り合衆國官吏の者下田に差置候儀も可有之尤約定調印より十八箇月後に無之候ては不及其儀候事

第十二條 今般の約定相定候上は兩國の者堅く相守可申尤合衆國主に於て長公會大臣と評議一定の後書を日本大君に致し此事今より後十八箇月を過きすして君主許容の約定取扱せ候事

右の條日本亞墨利加兩國の全權調印せしむる者也

嘉 永 七 年 三 月 三 日千八百五十四年三月三十日

Quelle: http://web.jjay.cuny.edu/~jobrien/reference/ob25.html. -- Zugriff am 2015-03-24 Quelle: http://ja.wikisource.org/wiki/日本國米利堅合衆國和親條約. -- Zugriff am 2015-03-24

1854-05-03

Sénatus-consulte du 3 mai 1854 qui règle la constitution des colonies de la Martinique, de la Guadeloupe et de la Réunion

"TITRE PREMIER. — Disposition applicable à toutes les colonies. Article premier

L'esclavage ne peut jamais être rétabli dans les colonies françaises."

[Quelle: https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/S%C3%A9natus-consulte_du_3_mai_1854_qui_r%C3%A8gle_la_constitution_des_colonies_de_la_Martinique,_de_la_Guadeloupe_et_de_la_R%C3%A9union. -- Zugriff am 2016-02-26]

1854-07-18

Rama IV. an Sir John Bowring (1792 - 1872):

“The most lawful and exalted Sovereign of the Kingdom of Siam and its adjacent tributary countries, viz. of the Laos Shiangs [Shans - တႆး / ลาวฉาน] on the N. Western, Laos Kaos [ลาวขาว] on the Northern and N. Eastern, Khars Chongs on the Eastern, Cambodia or Camboja on the S. Eastern, and most parts of the Malay Peninsula on the S. Western, and Karriangs [Karen - ကညီကလုာ် /กะเหรี่ยง] in the Western direction. To

His Excellency

Sir John Bowring, K. C. B.

Her Britannic Majesty’s plenipotentiary and Superintendent of Trade & Commerce in China, and Supreme Governor of Victoria Island, Hong Kong, and its dependencies, -

etc etc etcDated Rajruty House, Grand Palace. Bangkok, Siam, 18th July 1854.

My much respected Friend,

I have great honor in acknowledging receipt of your Excellency’s two letters under date 5th April last, written from Singapore, one of which letters was enclosed in that of my intimate friend, Colonel Butterworth K. C., [William John Butterworth, 1801 – 1856, Governor of the Straits Settlements] the other came separately and was accompanied by a parcel containing the Illustrated London Newspaper [1854-02-18], in one of which was your Excellency’s portrait or likeness together with an account of Your Excellency’s life from your infancy until the time your Excellency was knighted by Her Gracious Majesty, the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. On perusal of those papers, I was much pleased & interested. After the receipt of Your Excellency’s letters on the 25th May inst. I wished to write you an answer immediately, but was prevented from doing so on account of my manifold affairs and also from being indisposed in body, and thereby several opportunities were lost, but I trust your Excellency will pardon this delay.

Abb.: Illustrated London News, 1854-02-18, über John BowringI was very glad to learn that your Excellency and family were pleased with trifling present of a silver box of Siamese manufacture and black bags containing some pieces of gold and silver mementos of my late dearest Royal Consort, I am also happy to learn that your Excellency, being my correspondent and respected friend, has been just knighted and appointed to be Plenipotentiary and Chief Superintendent of trade in China and Governor of Hong Kong [香港] and its dependencies, and that your Excellency is also accredited to me with full power from Her Gracious Majesty the Queen of Great Britain & Ireland to enter into treaties and to discuss all subjects of interest between the Kingdoms of Great Britain & its dependencies, and the Kingdom of Siam and its adjacent tributary countries; and that it is also Your Excellency’s intention to visit Siam for the said purpose, I shall therefore have the honor of meeting Your Excellency personally and have an opportunity of making the friendship that existed between Great Britain & our country more firm and greater than it ever has been before.

To forward Your Excellency’s purpose I would beg to suggest that proper and suitable arrangements must be made before Your Excellency’s arrival here.

It is the custom in Siam that all official letters from other countries should be received first by the Great Officer of the foreign department, entitled His Excellency Chow Phaya Phraklang [เจ้าพระยาพระคลัง] or Prime Minister for Foreign Affairs, before the King or Sovereign of this Kingdom, who has a right to learn the contents, so that, the contents or subject of the foreign letter should be well believed and respected by the whole council of our Government.

Your Excellency’s former correspondence with me, were considered as private and the contents were not made known to our Council, as it is not customary. I am desirous therefore that Your Excellency should write, and announce Your Excellency’s intention of visiting Siam, and determine a certain time for your arrival here, say at least about two or three months after the date of Your Excellency’s letter, and also express the manner of, and the number of vessels and people that will accompany your visit, please let our officers of state be aware of the time of Your Excellency’s arrival here, in order that they will know without doubt and make proper preparations of receiving Your Excellency and retinue with all suitable honors and respect, and also our officers of state knowing of Your Excellency’s intentions will be enabled to quell the fears of the people who are of various races and prevent exaggerated reports, because it is very seldom foreign vessels of war or steamers visit Siam.

His Excellency Sir James Brooke [1803 - 1868], K. C. B., announced his intended visit three months previous to his arrival, so it has become a custom which I would be desirous of Your Excellency following.

At the same time I would be glad if Your Excellency would write also to me privately, and inform me of the nature of your visit and give the substance of the treaty you would be desirous of entering into, so that I might consider with my council, and know what clauses in the proposed treaty, they would be willing to agree and what they would not, I would therefore inform you of the same for your consideration and thereby will save a good deal of time and discussions after Your Excellency’s arrival here.

I shall be delighted to receive your presents of astronomical instruments, I am also anxious to procure articles in the shape of arms such as guns and pistols of the newest inventions or good handsome swords, etc. I shall feel obliged by Your Excellency procuring some for me. Any articles of Siamese manufacture Your Excellency is desirous of having please inform me of the same, and I shall have them manufactured or procured. The most curious and best articles of Siamese manufacture as made of gold or silver.I beg to present Your Excellency a silver tea pot made in Siam in the same manner that of the fore sent box together a few pictures painted in pieces of cloth and papers descriptions of which accompanied thereby or with every one, all in hands of the bearers hereof Mssrs Nai [นาย] Bhoo and Nai Kham who are my former or old servants sent to Canton [廣州] for attention of some articles ordered to be made therein. I wish their honour of personal respects with Your Excellency and Your Excellency’s kind acceptance of my trifling presents in their hands, and hope Your Excellency will enquire them for further understanding of what your Excellency does not well understand from my letter, and what prevails herein.

In last year I have written to my ambassadors who visited China to pay their visit to Your Excellency on their return from Peking [北京]. When they were arrived here, they stated that they have visited Hong Kong and did their enquiry for personal respect with Your Excellency and have learnt that Your Excellency were absent and they have received a note of such information from hand of an English personage and shown me.

Trusting your Excellency is most phylanthropy whose all people of all nations may be amicable or beloved and will do mercy and indulgence to Siam for being well not less or lower than adjacent kingdoms of Siam namely Cochin China and Burma. I beg to remain Your Excellency’s good and faithful sincere friend.

S. P. P. M. Mongkut

the King of Siam & Sovereign of Laos."[Zitiert in: Manich Jumsai [มานิจ ชุมสาย] <1908 - 2009> ; Monkut <König, Siam> [พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรเมนทรมหามงกุฎ พระจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว] <1804 - 1868> ; Bowring, John <1792 - 1872>: King Mongkut and Sir John Bowring (from Sir John Bowring's personal files, kept at the Royal Thai Embassy in London). -- Bangkok, Chalermnit, 1970. -- 240 S. : Ill. ; 27 cm. -- S. 39 - 42]

1854-07-28

James Brooke (1803 - 1868), Raja von Sarawak, an Sir John Bowring (1792 - 1872):

Abb.: James Brooke, 1847

[Bildquelel: Francis Grant (1803 - 1878). -- Public domain]

"It would be difficult to exaggerate the commercial capabilities of Siam; it possesses a healthy climate, soil, fit for the cultivation of every tropical production, and a length and breadth of country, varied by hill and dale, with presenting enormous plains stretching from the seacoast to the Ancient Capital of Ayuthia [อยุธยา], vailed agricultural advantages. Several of our merchants long resident in Siam, possessed of every opportunity of acquiring correct information have carefully studied the country, have correctly sketched its present condition, and have furnished data by which we may judge of what its capabilities are, and what its condition might become under ordinary good Government. Among the production for which Siam is famous, I may mention rice, sugar, pepper, cotton, indigo and tobacco; red sapan [Caesalpinia sappan L.], agillawood [Agarwood] and teak; gamboge, sticklac, tin, dried fish, buffalo horns and hides, salt, cardamoms, ivory and that heterogeneous map of products known by the name of a Junk cargo. It will be necessary to mention in detail a few of the articles most interesting to British merchants. At the head I mention rice; it is one of the most important cultivations in Siam, the country being admirably adapted to its production, from the facility with which the land may be irrigated. The prohibition to its export has necessarily curtailed operations, but were it removed, sufficient might be furnished for all the neighbouring markets. Now Singapore looks principally to Arracan [ရခိုင်ပြည်နယ်], but could we draw our supplies from Siam, the returns would be in British manufactures, instead of in cash. This would give a great impetus to trade both local and general. It would occasionally employ a large amount of British shipping.

Sugar

Sugar has been heretofore the main support of the trade; it has been looked upon as the return for British imports into Bangkok. Mr. [John] Crawfurd [1783-1868] states that the cultivation of sugar for trading purposes commenced about the year 1810; in 1822 it had increased to about 3500 tons, in 1835 to 8000 tons and in 1840 to 15, 000; at the last period the government allowed their Chinese farmers to meddle with the trade, and the consequence has been that in 1851 I was informed that not more than 7500 tons, would be produced. This is a great falling off, and is solely to be ascribed to injudicious interference. The whole valley of the Menam [แม่น้ำเจ้าพระยา] appears adapted to this cultivation, the brown sugar is equal to muscavado [muscovado], while the red is of inferior quality. It is now principally exported to China, formerly much found its way to Bombay, but latterly the trade has decreased. Should the cultivation be protected by the new monarch, the export of sugar will form a very important element of our trade, and be of the utmost consequence to British shipping. Mr. Crawfurd states that in his time, the cultivators of the cane were always Siamese; if I am not misinformed, the Chinese are now the principal if not the only producers, and it was the interference with their rights which caused the rebellion among the Chinese.

Pepper

Pepper of excellent quality is also produced here, the quantity now. as in Mr. Crawfurd’s time may be rated at 60, 000 piculs: it is principally exported to China.

Cotton

Cotton is also a production of Siam. It is exported in large quantities by the Junks; land fit for its cultivation abounds in the country above the line of inundated tracks.

Indigo

Much of the indigo is exported to China and Singapore, besides large quantities held for home consumption; the Siamese have yet to be taught the art of hardening it; it is now only to be had in the liquid state.

Tobacco

In the beginning of this century Siam produced comparatively little tobacco, now it is cultivated with great success, and exported in large quantities; the demand alone limits the supply.

Woods

Red, Sapan [Caesalpinia sappan L.], Agilla wood [Agarwood] and teak are to be had in inexhaustible supplies: of sapan and red wood, the junks annually export large quantities, the high measurement duty has however curtailed European operations and also the late prohibition to the export of teak has told very disadvantageously.

Gamboge and sticklac two curious productions are also valuable to the trade: the two species of cardamum are much sought after for the China markets, where they fetch high prices.

Without entering further into particulars which would swell this sketch to an inconvenient length, I may call to mind that in one year fifty-five British vessels exported valuable cargoes even with the present heavy measurement duty, and in spite of the hindrances arising from a jealous and despotic government; but besides this British trade, junks annually arrive from China, whose tonnage moderately taken, may be estimated at above 56. 000 tons.

It has been reckoned, and it is not difficult to obtain an approximation, that the average exports in the China Junks of the principal articles amount to the following: -

Pepper 3500 tons. Red Sugar 5000 tons. Brown Sugar 3500 tons. Red Wood 6000 tons. Sapan Wood 5000 tons. Cardamums are also exported in great quantities, the best sort fetch £ 37. 10 per picul, the inferior or bastard £35. — besides sticklac, gamboge, ivory, tin, horns, hides, salt, dry fish, buffalo meat, pinag back (? ), shark’s fins, and other articles adapted to the China market. To Hainan cotton cleaned and uncleaned, varying from 3000 to 5000 tons annually, with some of the above articles, and at times a large amount of British piece goods.

To Java large quantities of dried and salt fish, buffalo meat, Chinese wares and other articles. Fish is often exported to Java in bulk. The above rough outline will give some idea of the trade that is carried on, and what it might become under a fostering and fraternal government.

Our mercantile and manufacturing countrymen should consider these markets: They are almost new, and promise a lucrative trade, or trade that affords many openings. It is satisfactory to be able to state that the Siamese are inclined to become extensive consumers of British manufactures, but the restricted trade, and their own consequent poverty checks all healthy transactions.

Impediments to British Trade

The complaints that have been made against the Siamese government are that, contrary to the treaty of 1826, they have levied duties on iron and steel, also on sticklac; that the exportation of teak has been prohibited; that merchants have been prevented chartering vessels, other than those of the (late) king, which are old, and many overrun with white ants; that monopolies have been established of sugar, oil, etc etc. The monopoly of sugar causes the price to rise forty percent, and all qualities being paid for at about the same rate, the article has greatly deteriorated (Personal injuries and losses though many I leave unnoticed).

Privileges of the Chinese

Under all these restrictions which only apply to the British merchant, he has to oppose the Chinese who trade under the following privileges. They pay no measurement duty: They export many articles free of duty; others with only slight duties; they have the privilege of junk building; they are allowed to use their own vessels, or to charter any they please, whereas Englishmen may not make use of junks; they have the permission to purchase any of the duties farmed out, and the privilege of manufacturing and selling certain articles; freedom to purchase lands and houses; freedom to grow and manufacture sugar; to grow rice or what they please; and freedom to proceed into the interior to purchase produce.

Under all these circumstances, and considering the violations of the treaty, it was thought that the following demands might be made; that the English should enjoy the same privileges as those granted to the most favoured nation; that there should be a moderated measurement duty, or a tonnage duty, or a combined measurement and tonnage duty, or a graduated measurement duty, or there should be a tariff and a consular establishment, that the merchants should be allowed to purchase of the producer direct; that every article should be allowed to be exported including teak, rice, salt and spice; that there should be a consul, and that British vessels of war might be permitted to enter the river; further that British subjects should be allowed to lay their grievances before the King without any humiliating ceremonies; the privilege of building ships in Siam, and of purchasing land there, room for a church and churchyard, that the Govt, of Siam should refund the duties, that have been levied contrary to treaty; freedom of moving about the country; ships unladen to pay no duty; partly laden to pay in proportion; no inland duties to be allowed. Such were the demands that various merchants hoped and expected would be made by the British Government during the last mission.Effects of a Fair Treaty

Had we an equitable treaty with Siam, and were it thoroughly carried out, I believe I could set no limits to the trade. All who have seen the country report equally favourably of its capabilities, and one who knew Siam better than any other man, declared that with a fair home Government and an enlightened foreign policy, the trade with Siam would be second only to that with China. The means by which this very desirable end might be brought about are those which must next engage our attention. With the internal administration of the country, we have of course nothing to do, we may hope that the present enlightened ruler will gradually ameliorate the condition of his people, repress the tyranny of the nobles, and the rapacity of the farm holders, abolish all internal duties, which do more damage to trade, than ever they can afford pecuniary assistance to a Government, and encourage the industry of his people, who are naturally quick and intelligent, and if allowed to enjoy the fruits of their labour would become a great producing community. Our present purpose is with the foreign policy, and the expectations we have from the new mission. Should the King of Siam take an enlightened view of the subject, and all our information leads us to expect he has the will, and I trust the power, a new era in the commerce of Siam will result from the expected treaty.

Stipulation necessary in a New Treaty

The Treaty will doubtless be simple, the simpler the better; tariffs are at all times troublesome, and might lead to great disputes, unless placed entirely under the control of the consul. The principle stipulations of the new Treaty should be.

- The same privileges as are granted to the most favoured nation.

- a fair tonnage duty, or a graduated measurement duty (ships arriving and returning in ballast to pay no duty).

- freedom to export all articles.

- Permission to purchase land and houses & to build ships.

- Permission to purchase directly of the producer. &

- A Resident or Consul to be established immediately at Bangkok.

These should be the six principal articles.

Considerations respecting above articles

Let us consider these articles more in detail.

The first article is obviously necessary.

The second - a tonnage duty is the best: a consul would prevent any deceit being practised on the Siamese Government; a measurement duty unless carefully graduated is always unfair, the difference between the breadth of a —ton ship and a—ton ship is comparatively small, so that the two ships pay very unequal duties. The present measurement duty is 1700 ticals or £ 212. 10 per fathom in breadth, which is much too high. I have great hopes to see it reduced to about a third if not a fourth.

Third Article - Freedom to export all articles is very essential, at present neither rice, salt, teak or spice can be exported. Siam being a rice-growing country thus deprived herself of the privilege of supplying her neighbours with this (in the East) necessity of life, under the absurd idea that she thus prevents famines. I trust that his present Majesty will have sounder views of political economy, it is so essential point, that unless included in the coming Treaty the work will be half done. Salt would itself become an extensive branch of trade, were it not encumbered with almost prohibiting duties. Teak is also of great value as an article of commerce and its export would afford to the Siamese in the interior very profitable labour. Every merchant knows the inconvenience and loss he would sustain in a half civilized country where spice was one of the forbidden exports.

Fourth Article - The permission to purchase land and houses is very essential, indeed without it no firm can carry on its business in security; under the old system, a merchant might be expelled from his house, and ordered to remove his goods from his warehouses in the course of two hours, under the threat of having them all thrown into the streets; the houses being rented of government they were under the charge of an officer, who at the least hint from his superiors, declared the house was wanted and the merchant must leave. With this uncertainty nothing can be done. The Siamese government to obviate ail disputes might grant to the British, as it has granted to the Portuguese, a certain amount of land for merchants, houses and godowns; here the consulate might be established, and all chance of unpleasant quarrels removed. The permission to construct ship building yards is another important point, teak is to be had cheap and in great quantities, and were our speculators to enter into this branch of trade, it might be of infinite service to the seamen, by giving employment to hundreds. That government need fear no disturbances among their inland population, as long as they are provided with sufficient remunerative labour.

Fifth Article - The non-fulfilment of the fifth Article gave rise to most of the unpleasant complaints that were made against the government of the late King. Any interference between the producer and the merchant must be of serious injury to both parties. What was called the sugar farm was peculiar; men bought the privilege of being the sole purchasers of sugar; they paid the grower and manufacturer what price they pleased, and sold it at their own rate to British merchants; the effect was to be expected; the cultivation of sugar decreased, the quality deteriorated, and the British merchant was compelled to pay forty percent more for an inferior article. Wherever monopolies exist, particularly in Eastern countries, heavy loss is ultimately sustained by all parties, by the government, the producer and the merchant, with the exception of the few farmers who make enormous profit.

Sixth Article will refer to a Resident or Consul. Unless some such officer be established then, all chance of amicable relations continuing even with a good treaty will be lost. There must be a disinterested channel of communication between the European traders and the Asiatic rulers. Prejudices are so easily offended, fresh comers from Europe are totally unfitted to deal either with Malays or Siamese, they despise the manners and habits of both, and without wishing it give deep offence by the want of observance of Asiatic etiquette. With all due difference to the mercantile community, they are naturally so much occupied with their own personal interests, that they are impatient of delay, and in more than one instance in Siam, gave that government many pretexts for not listening to their just remonstrances.

A treaty containing some such six articles as the above, if kept and fairly acted on, would ensure a very extensive trade to Great Britain: the present population is probably under five millions, but a portion of these are industrious Chinese, where numbers would increase according to the encouragement given to their agricultural pursuits. The junks annually bring thousands of these emigrants, the most industrious in the East, land is to be had in every direction admirably adapted for the cultivation of every tropical production. Coffee has not yet been cultivated to any great extent, but if we may judge from that grown in the Praklang’s garden, the quality is by no means inferior.

It is perhaps useless to speculate on the future of Siam, it possesses every advantage, noble rivers, fertile soil, a population susceptible of any expansion, varied products; and the neighbourhood of countries all anxious to share in the lucrative trade that may arise. I may observe that should the new mission succeed, and a fair treaty be formed Siam will become of the greatest commercial value to the mercantile and manufacturing interests of Great Britain.

The existing impediments to the extension of trade (& by existing I mean those that existed in the beginning of 1851) are the monopolies, the illegal duties, the heavy measurement duty, the oppressive and tyrannical conduct of the Siamese officers, and the humiliating position of the British merchant, liable by Treaty to be flogged for an imaginary offence.

But such impediments are, it is to be hoped, of the past, the present king deeply impressed with the benefits and advantages of European civilization seeks by every prudent means to remove obstructions to commerce, and to enrich his people by the consequent influx of capital to his country. The character of the two princes Chow fah Yai [เจ้าฟ้าใหญ่] & Chow fah Noi [เจ้าฟ้าน้อย], the two kings, who now jointly reign in Siam, deserves a European reputation. The Eldest with imperfect help, has studied Astronomy with great success, and reads and writes English fluently; the second has turned his attention to machinery and ordinance and has advanced far in his studies. The present Praklang [พระคลัง], or Foreign Minister, (the former Pra Nai Wai [จมื่นไวยวรนาถ], or Si Suri Wong [ศรีสุริยวงศ์, 1808 - 1883]) is an intelligent looking man, the vessels in the river Menam are an evidence of his skill in shipbuilding and he is now turning his attention to the improvement of the defences of the river by means of fortifications after the European models. The direction taken by the present Governors of Siam in their studies promises much: their deeper cultivation will strengthen their ties to England, and impress upon them our place in the scale of nations, of our power and willingness to aid them, and the futility of quarrelling with their best friends. I look forward with pleasure to the cause of these Siamese statesmen, earnestly hoping that His Majesty will be cautious in his reforms and not drive to desperation that party of the nobles who have fattened amid the riches of their country."

[Zitiert in: Manich Jumsai [มานิจ ชุมสาย] <1908 - 2009> ; Monkut <König, Siam> [พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรเมนทรมหามงกุฎ พระจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว] <1804 - 1868> ; Bowring, John <1792 - 1872>: King Mongkut and Sir John Bowring (from Sir John Bowring's personal files, kept at the Royal Thai Embassy in London). -- Bangkok, Chalermnit, 1970. -- 240 S. : Ill. ; 27 cm. -- S. 31 - 39]

1854-12-05

Berlin (Deutschland): der deutsche Drucker Ernst Theodor Amandus Litfaß (1816 - 1874) erhält die erste Genehmigung für seine „Annoncier-Säulen“ (Litfaßsäulen).

Abb.: Litfaßsäule ca. 1855

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Reklame, Bangkok, 2008

[Bildquelle: husar. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/31703507@N00/2596643387. -- Zugriff am 2013-10-11. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielel Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

1854-12-08

Papst Pius IX. verkündet mit der Bulle Ineffabilis Deus das Dogma von der Unbefleckten Empfängnis (Freiheit von Erbsünde) der Jungfrau Maria:

„Zur Ehre der Heiligen und ungeteilten Dreifaltigkeit, zur Zierde und Verherrlichung der jungfräulichen Gottesgebärerin, zur Erhöhung des katholischen Glaubens und zum Wachstum der christlichen Religion, in der Autorität unseres Herrn Jesus Christus, der seligen Apostel Petrus und Paulus und der Unseren erklären, verkünden und bestimmen Wir in Vollmacht unseres Herrn Jesus Christus, der seligen Apostel Petrus und Paulus und in Unserer eigenen: Die Lehre, dass die seligste Jungfrau Maria im ersten Augenblick ihrer Empfängnis durch einzigartiges Gnadengeschenk und Vorrecht des allmächtigen Gottes, im Hinblick auf die Verdienste Christi Jesu, des Erlösers des Menschengeschlechts, von jedem Fehl der Erbsünde rein bewahrt blieb, ist von Gott geoffenbart und deshalb von allen Gläubigen fest und standhaft zu glauben. Wenn sich deshalb jemand, was Gott verhüte, anmaßt, anders zu denken, als es von Uns bestimmt wurde, so soll er klar wissen, dass er durch eigenen Urteilsspruch verurteilt ist, dass er an seinem Glauben Schiffbruch litt und von der Einheit der Kirche abfiel, ferner, dass er sich ohne weiteres die rechtlich festgesetzten Strafen zuzieht, wenn er in Wort oder Schrift oder sonstwie seine Auffassung äußerlich kundzugeben wagt.“ Die Katholiken Siams freuen sich, haben sie doch schon 1847 die Church of Immaculate Conception in Bangkok gebaut

Abb.: Unbefleckt Empfangene, Kathedrale Chanthaburi (จันทบุรี)

[Bildquelle: http://thailand-cathedral-catholic.blogspot.de/2009/06/immaculate-conception-cathedral.html. -- Zugriff am 2013-10-31. -- Fair use]

ausführlich: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/ressourcen.htm

Moffat, Abbot Low <1901 - 1996>: Mongkut, the king of Siam. -- Ithaca N.Y. : Cornell UP, 1961. --254 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm.

Blofeld, John <1913 - 1987>: King Maha Mongkut of Siam. -- 2. ed. -- Bangkok : Siam Society, 1987. -- 97 S. : Ill. ; 22 cm.

Chula Chakrabongse [จุลจักรพงษ์] <1908 - 1963>: Lords of life : History of the Kings of Thailand. -- 2., rev. ed. -- London : Redman, 1967. -- 352 S. : Ill. ; 22 cm.

Phongpaichit, Pasuk <ผาสุก พงษ์ไพจิตร, 1946 - > ; Baker, Chris <1948 - >: Thailand : economy and politics. -- Selangor : Oxford Univ. Pr., 1995. -- 449 S. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 983-56-0024-4. -- Beste Geschichte des modernen Thailand.

Terwiel, Barend Jan <1941 - >: A history of modern Thailand 1767 - 1942. -- St. Lucia [u. a.] : Univ. of Queensland Press, 1983. -- 379 S. ; 22 cm.

Ingram, James C.: Economic change in Thailand 1850 - 1870. -- Stanford : Stanford Univ. Pr., 1971. -- 352 S. ; 23 cm. -- "A new edition of Economic change in Thailand since 1850 with two new chapters on developments since 1950". -- Grundlegend.

Akira, Suehiro [末廣昭] <1951 - >: Capital accumulation in Thailand 1855 - 1985. -- Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, ©1989. -- 427 S. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 4896561058. -- Grundlegend.

Skinner, William <1925 - 2008>: Chinese society in Thailand : an analytical history. -- Ithaca, NY : Cornell Univ. Press, 1957. -- 459 S. ; 24 cm. -- Grundlegend.

Simona Somsri Bunarunraksa [ซีมอนา สมศรี บุญอรุณรักษา]: Monseigneur Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix : ami du roi du Siam, imprimeur et écrivain (1805 - 1862). -- Paris : L'Harmattan, 2013. -- 316 S. : Ill. ; 24 cm. -- (Chemins de la mémoire ; Novelle série). -- ISBN 978-2-336-29049

Morgan, Susan <1943 - >: Bombay Anna : the real story and remarkable adventures of the King and I governess. -- Berkeley [u.a.] : Univ. of California Press, 2008. -- 274 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 978-0-520-26163-1

ศกดา ศิริพันธุ์ = Sakda Siripant: พระบาทสมเด็จพระจุลจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว พระบิดาแห่งการถ่ายภาพไทย = H.M. King Chulalongkorn : the father of Thai photography. -- กรุงเทพๆ : ด่านสุทธา, 2555 = 2012. -- 354 S. : Ill. ; 30 cm. -- ISBN 978-616-305-569-9

Lavery, Brian: Schiffe : 5000 Jahre Seefahrt. -- London [u. a.] : DK, 2005. -- S. 184. -- Originaltitel: Ship : 5000 years of marine adventure (2004)