Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Chronik Thailands = กาลานุกรมสยามประเทศไทย. -- Chronik 1877 (Rama V.). -- Fassung vom 2016-11-25. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/chronik1877.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2013-09-11

Überarbeitungen: 2016-11-25 [Ergänzungen] ; 2016-03-26 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-09-15 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-06-18 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-04-17 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-03-20 [Ergänzungen] ; 2015-02-28 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-12-18 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-11-11 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-03-05 [Ergänzungen] ; 2014-01-14 [Ergänzungen] ; 2013-09-23 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Herausgebers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Thailand von

Tüpfli's Global Village Library

ช้างตายทั้งตัวเอาใบบัวปิดไม่มิด

|

Gewidmet meiner lieben Frau Margarete Payer die seit unserem ersten Besuch in Thailand 1974 mit mir die Liebe zu den und die Sorge um die Bewohner Thailands teilt. |

|

Bei thailändischen Statistiken muss man mit allen Fehlerquellen rechnen, die in folgendem Werk beschrieben sind:

Die Statistikdiagramme geben also meistens eher qualitative als korrekte quantitative Beziehungen wieder.

|

1877 - 1890

Sultan Ahmad Ibni Tengku Muhammad Ibni Sultan Mansur of Terengganu (ترڠڬانو) ist Sultan (سلطان) Kelantan (كلنتن)

Abb.: Lage von Kelantan (كلنتن)

[Bildquelle: Constables Hand Atlas of India, 1893. -- Pl. 59]

"Sultan Ahmad Ibni Tengku Muhammad Ibni Sultan Mansur of Terengganu (Marhum Besar).

- Appointed as regent of Kelantan but installed as Yang Di-Pertuan of Kelantan by Siam in 30 October 1886 after his father-in-law Sultan Muhammad II died.

- Before that, appointed as Siamese Governor over Kelantan,

- prom. to the title of Phraya Rajadipati Putrapurutravisesa Pradisvara Rajanarubadindra Surindra Ravivamsa (Phraya Ratsathibodi Butburutphiset Prathetsaratchanarubodin Surintharawiwangsa) and presented with a Sword of Honour, 14 June 1869 by King Rama IV"

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sultan_of_Kelantan. -- Zugriff am 2015-02-28]

1877

Abb.: Siamesin, 1877

1877

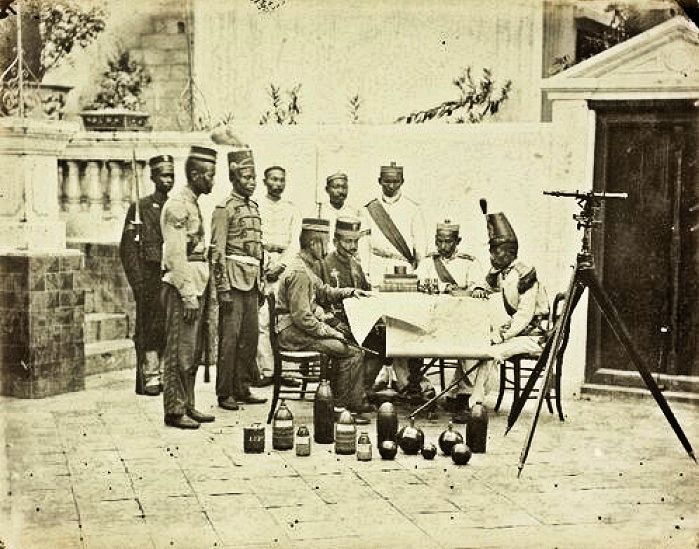

Abb.: Siamesisches Militär mit zur Schau gestellten Geschoßen, 1877

vor 1877

Abb.: Siamesischer Kriegselefant, vor 1977

1877

Edikt über Rückzahlung von Krediten in Form von Getreide:

"Außerdem war es früher üblich, dass die Landwirte Kapital und Zinsen in Getreide zurückbezahlten. Diese Getreidepreise waren aber dann niedriger als auf den Märkten geschätzt; daher mussten die Bauern nicht nur die Zinsen bezahlen, sondern auch das Getreide billiger abgeben. Um dem zu steuern wurde das Edikt von 1877 erlassen; dieses bestimmt, dass zwar die Rückzahlung des geliehenen Kapitals in Getreide und Rohprodukten weiter bestehen darf, dass aber in diesem Falle das Getreide und die anderen Produkte ebenso berechnet werden müssen, wie auf dem Markte."

[Quelle: Dilock <Prinz von Siam> [Diloknobbarath, Prince of Sarnga - พระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ พระองค์เจ้าดิลกนพรัฐ กรมหมื่นสรรควิสัยนรบดี] <1884 - 1912>: Die Landwirtschaft in Siam : ein Beitrag zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte des Königreichs Siam. -- Leipzig : Hirschfeld, 1908. -- 215 S. -- Zugleich: Univ. Tübingen, Diss. 1907. -- S. 200]

1877

Bau des Wihan (วิหาร) von Wat Pa Daet (วัดป่าแดด) in Mae Chaem (แม่แจ่ม).

Abb.: Lage von Mae Chaem (แม่แจ่ม)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Wihan (วิหาร), Wat Pa Daet (วัดป่าแดด), Mae Chaem (แม่แจ่ม), 2013

[Bildquelle: Takeaway / Wikimedia. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1877

71 Vorschriften für die königliche Leibgarde (พระราชบัญญัติข้อบังคับสำหรับกรมทหารมหาดเล็ก)

1877

Es erscheint

Pallegoix, Jean-Baptiste <1805 - 1862>: English Siamese vocabulary enlarged with an introduction to the Siamese language and a supplement. -- Bangkok : For sale at the catholic mission Press, 1877

1877

In Bangkok und Umgebung leben ca. 2000 Kantonesen (廣府人).

Abb.: Lage von Kanton

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1877

Es erscheint

Bowring, John <1792-1872>: Autobiographical recollections of Sir John Bowring. With a brief memoir by Lewin B. Bowring [1924 - 1910]. -- London : King, 1877. -- 404 S. ; 23 cm. -- Die postum herausgegebenen Erinnerungen stammen meist aus dem Jahr 1861.

Abb.: Frontispize

"SIAM. One of the most interesting parts of my public life was my visit to Siam in 1855, of which I published an account in two volumes, called "Siam and the Siamese." There had been many attempts on the part of the United States of America, of the Governor General of British India, and of the English government, to establish diplomatic and commercial relations, but they had utterly failed. Sir James Brooke [1803 - 1868], the Rajah of Saráwak, had visited the Meinam [Maenam - แม่น้ำเจ้าพระยา], and endeavoured to open a correspondence with the Siamese authorities, but his reception was so unfriendly that he was compelled to break off all negotiations.

The country was crushed by monopolies, almost every article of produce was made an exclusive property, and there were only two vessels engaged in the foreign trade. An obstinate and ignorant illegitimate son had succeeded to the throne ; but on his death the nobility clamoured for the recognition of the legitimate descendant, a remarkable man, who had retired from public life, and made his person sacred by becoming a Buddhist priest, and withdrawing to a convent, where for eleven years he devoted himself to the study of Sanskrit, Pali, and other Oriental tongues. He learned Latin from the French Catholic Missionaries, at whose head was Bishop Pallegoix [1805 - 1862], the author of the Thai dictionary and grammar, and of one of the best accounts of Siam ; and English from the American Missionaries, who for many years had a Protestant Propaganda in Siam, where, if truth be told, they laboured with little success.

The new King, who was a most enlightened, sagacious, and enquiring man, had been a correspondent of mine, and received in an amiable spirit the overtures I made him. I informed him—which indeed he knew well, for he had a pretty accurate knowledge of Oriental and European politics—that I had a large fleet at my disposal, but that I would rather visit him as a friend than as the bearer of a menacing message. He wrote to me to request that, in order not to alarm his subjects, I would come with a small naval escort, so I steamed to the Meinam, with two vessels of war, one of which, the “ Rattler,” conveyed me and my suite to Siam.

Abb.: HMS Rattler, ca. 1845

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]We were advised by the American Missionaries that I must expect to fail as other envoys had failed, that the Siamese were preparing barricades on the river, and giving other evidence of an unfriendly spirit, that the Court was hostile to strangers, and that our conquests in India had awakened and seemed to justify their apprehensions.

Arrived at the mouth of the river, I sent my secretaries to the capital, where they had little reason to be pleased with their reception, as they were kept in a sort of imprisonment, and not allowed communications beyond their abode. The King, however, determined to send down one of his steamers to Paknam [ปากน้ำ; heute: Samut Prakan - สมุทรปราการ], to ask more specifically the purposes of my mission, and to beg that they might be put in writing for his information. A similar request had been made to Sir James Brooke, who had complied with it, and was soon involved in an irregular and entangled controversy. My answer was a refusal to enter upon such correspondence, as it might involve me in making demands which it might be inexpedient or impossible for them to grant, and exclude topics which it might be important for both parties to introduce. I said I should prefer some preliminary conversation, in which they could explain to me their position and objects, and hear from me what I thought we might reasonably expect from them.

The negotiations were thus opened, but many difficulties arose which had to be vanquished. They wished the ships of war to remain at the mouth of the river, to which I could not consent, as, independently of their being necessary to my comfort, they and their officers were requisite appendages to my mission. Then the Siamese requested that the guns might be left in their keeping, while the ships ascended the river, a condition equally inadmissible. Next the King sent down a number of royal barges, magnificently adorned, in the shape of dragons and peacocks, with gold and crimson silk drapery, to escort me to the city in all dignity, as if we were Siamese of the highest rank. I accepted the proffered courtesy, but requested that the “ Rattler ” should follow in our wake. After a day’s delay, this point was conceded, but they wished to impose another condition, namely, that no salutes should be fired, as this might frighten the people. I urged, however, that it was out of the question for us to see the flag of the White Elephant (the Siamese ensign) flying on the palace without saluting it, and that I expected a return salute of seventeen guns, but I suggested that the King should announce by proclamation our intended arrival as friends, and that the salutation of his flag was a respect paid to him by the Queen of England. I added that it would be wise to send some of his State Officers on board the “Rattler,” to witness the ceremonies, and then matters were comfortably and peacefully arranged.

On arriving at the court, however, a new perplexity awaited us, as no man was allowed to approach the king’s person with any weapon, but I informed them that we always wore swords when received by our sovereign, and I was able to show that M. Chaumont [Alexandre II de Chaumont, 1640 - 1710], who had been the ambassador of Louis XIV. [1638 - 1715], had worn his sword in the presence of the then king, and that I was the representative of a monarch certainly as great as the sovereign of France. The king sent for me at night, and conducted me secretly to the audience-hall, where I settled with him all the terms of precedence, respecting which he was glad to be instructed, as he would know how to arrange matters for other ambassadors who might follow me. I said that I could not ask the officers of Her Majesty’s naval service to divest themselves of an ornament which was a part of their official costume, in which they were bound to show their respect for a foreign power.

The King’s throne was an elevated recess, regally adorned. He wore a high, splendid crown, with many precious stones, and held his sceptre in his hand, while near him were the members of the royal family, which comprised then forty or fifty sons. We passed to the centre of the hall, all the nobles being on their faces in the presence of their monarch.A cushion had been provided for me to sit on, while my suite stood around me. I made my address to the King, but though His Majesty understood English, it was translated into Siamese for the benefit of the audience, while the king’s answer was translated from Siamese into English, that all the replies might be intelligible to our party. The following day similar ceremonies were performed in the presence of the second King. There was an interchange of presents, and I was sorry to see that the telescope which was among the gifts sent by the Queen, was far inferior to those which the King had, already in his observatory. Among other presents which His Majesty handed to me was one which he said was of greater value than all the rest. It was a golden box, locked with a golden key, in which were some hairs of the tail of the sacred white elephant tied with floss silk. The possession of a white elephant is considered a high privilege, it being believed to be one of those incarnations in which Buddha loves to dwell, an emblem of purity, though the skin is not white but of a coffee colour. The elephant is kept in a beautifully ornamented stable, is fed upon sugar-cane, is waited on by Siamese dignitaries, and, whenever it goes forth to bathe, is covered with splendid drapery, preceded by music, and accompanied by reverential crowds.

After the reception, the King sent for me to visit him privately in his apartments, and said he had understood perfectly every word in my address except one, of which he desired an explanation. He had no garment on but his shirt, and held a child on his knee, utterly naked, but wearing a wreath of fragrant white flowers. He was fond of his children, and wrote me a letter five months after my visit, which began, “Plenty of Royalty! five children have been born to me since you left.”

The Siamese laws about etiquette are so rigid that no man is allowed to cross a bridge if a noble be passing on the water below, and if an individual of inferior rank is found in an upper apartment when visited by a superior, he must either descend, or the superior, instead of ascending the staircase, makes his entrance through the window, in order to maintain a more elevated position. A curious exhibition of this feeling occurred on board the “Rattler,” when a member of the royal family visited her. He saw in the cabin several images of Buddha, over which the sailors were accustomed to walk upon deck. He showed great distress at what he deemed a profanation, and offered a large sum of money for the idols, as it would have been a merit recognised in a future state of existence to have released the emanation from the godhead from a state of ignominy. I was not able to comply with his request, and informed him that, with the feelings of Christian people, it was quite impossible to give any security that the images of Buddha would not frequently be placed in a similar position. It is remarkable, however, that the King repudiated all the teachings of the Bonzes, which are inconsistent with the discovered truths of natural philosophy, particularly those of a geographical and astronomical character, to the study of which he had specially devoted himself. He had a large collection of telescopes, quadrants, and other instruments, was able to calculate an eclipse, and had himself published an almanack for the use of his people. He insisted that the vulgar errors which are prevalent in Siam now, as they were formerly in Europe, are not warranted by the earlier revelations of Gautama, who lived about the time of Confucius and Herodotus, and is deemed the last incarnation of Buddha manifested to the world. It is remarkable that a similar philosophical spirit distinguishes the reformed Brahmins of India, who repudiate the corruptions found in the Shastras, and aver that there is no authority for such adulterations in the more ancient and far more sacred books, the Vedas. Among the Reformed Hebrews, there is a similar determination to reject the teachings of the Talmud, as haying no divine authority, while even in the Christian Church, many are bringing into the field of discussion opinions which, a few centuries ago, would undoubtedly have been deemed heterodox and heretical. In China, the learned Confucians treat with utter contempt the hundreds of volumes of legendary rubbish which have been introduced by the Buddhist and Taoist priests. In fact, a new spirit of religious investigation pervades the whole eastern and western world, and, in the course of a few centuries, will no doubt modify opinions now deeply rooted and widely spread.

The king of Siam used to express an opinion that what he called the Superior Intelligence had given different religions, each specially adapted to the locality and people to whom his will had been conveyed. He put no impediment in the way of the teachings of either Catholic or Protestant missionaries, saying, what was most true, that they had made few, if any, converts among his people. There are at Bangkok a considerable number of professing Catholic Christians, but they mostly belong to the mixed races, the descendants of the Portuguese, while the few converts whom the Protestant missionaries claim are to be found principally among the Chinese settlers. There is probably no nation, with the exception of the Singhalese, so attached to Buddhist rites and doctrines as are the inhabitants of Siam. Every Siamese passes three months of his life in a convent, where the priests instruct him in the creed of Buddha, and it must be acknowledged that as a race, the Siamese Bonzes are incomparably more intelligent than those found in China, or any of the remoter regions of Eastern Asia. Time has produced great changes in the action of different sects, for, though Christians only are now to be found sending forth teachers to carry on the work of conversion, there was a period when the missionaries of Buddhism covered the face of China, made their way to the court, and persuaded millions of men to embrace their faith. Though the Mahommedans, after the death of the prophet, despatched their priests to the Flowery Land, they were less successful than the advocates of Buddhism and Brahminism, who came from India.

[...]

On one occasion the King of Siam delivered over a great number of Anamite prisoners to Pallegoix, the Catholic Bishop, telling him that he might convert them to Christianity if he could.

I may add in conclusion that the Anglo-Siamese Treaty has brought most beneficial fruits. The number of vessels engaged in foreign trade has been centupled, the sides of the Meinam are crowded with docks, the productive powers of the land have increased, and with them the natural augmentation of property, and the rise of wages. The number of Chinese who are settled in Siam have greatly aided the natural developement, and intercourse with Europeans has not introduced, as in many parts of the world, the deteriorating effects of intemperance. Siam is a country of progress, and is sending forth her youth to be educated in the best schools and colleges of Europe. The Siamese, like the Japanese, are more aware of the advantages of Christian civilization than are the proud Chinese, but even upon China that civilization is not without its beneficent influence."

[a.a.O., S. 242 - 250]

1877

König Norodom I ( ព្រះបាទនរោត្តម) (1834 – 1904) von Kambodscha schließt einen Geheimvertrag mit dem spanischen Konsul in Saigon auf. Die Einzelheiten sind im Dunkeln. Spanien anerkennt den Vertrag nicht. Frankreich ist beunruhigt.

1877-01-15

Auf Druck der Franzosen verkündet König Norodom I ( ព្រះបាទនរោត្តម) (1834 – 1904) von Kambodscha einige Reformen. Als Gegenleistung beginnen die Franzosen mit der Niederschlagung der Revolution von Si Votha (សិរីវត្ថា) gegen seinen Halbbruder Norodom.

1877-01-29 - 1877-09-24

Japan: Satsuma-Rebellion (西南戦争): Revolte der Samurai der Provinz Satsuma (薩摩国) gegen die Meiji-Regierung (明治天皇). Wird in der Schlacht von Shiroyama (城山の戦い), 1877-09-24, unter General Aritomo Yamagata (山縣 有朋, 1838 - 1922) niedergeschlagen. Der General gilt als Vater des modernen japanischen Militärs.

Abb.: Lage der Provinz Satsuma (薩摩国)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Schlacht von Shiroyama (城山の戦い), 1877-09-24

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

1877-02

Französische, kambodschanische und vietnamesische Truppen schlagen in Ba Phnom (ស្រុកបាភ្) die Rebellion von Prinz Si Wâtha [Siwotha] nieder.

Abb.: Lage von Ba Phnom (ស្រុកបាភ្)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1877-02/03

Alexander Graham Bell (1847 - 1922) überträgt Vorträge per Telefon von Salem nach Boston (ca. 25 km).

Abb.: Vortrag in Salem

Abb.: Zuhörer in Boston

1877-03-04 - 1881-03-04

Rutherford B. Hayes (1822 - 1893) ist Präsident der USA.

Abb.: Wahlplakat 1876

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

1877-03-11

Emile Knecht, chancelier am französischen Konsulat in Bangkok, über den britischen Konsul:

"Le soir, à cinq heures nous allons faire notre visite au 3ième Roi du Siam, ainsi que beaucoup ont surnommé, et non sans raison, le Consul d'Angleterre." [Zitiert in: Tuck, Patrick J. N.: The French wolf and the Siamese lamb : the French threat to Siamese independence, 1858-1907. -- Bangkok : White Lotus, 1995. -- 434 S. : Ill. ; 22 cm. -- ISBN 974-8496-28-7. -- S. 344, Anm. 31]

1877-04/05

in Ba Phnom (ស្រុកបាភ្, Kambodscha) finden vom kambodschanischen König gesponserte Menschenopfer für die Hindugöttin महिशासुरमर्दिनी (mahiṣāsuramardinī).

Abb.: Lage von Ba Phnom (ស្រុកបាភ្)

[Bildquelle: OpenStreetMap. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

1877-04-05

Geheimabkommen von Konter-Admiral Victor Auguste Duperré (1825 – 1900), Gouverneur von Indochina, und König Norodom I ( ព្រះបាទនរោត្តម) (1834 – 1904) von Kambodscha. Danach kann der französische Repräsentanta in Kambodscha an allen Sitzungen des Ministerrats mit beratender Stimme teilnehmen. Seine Teilnahme ist obligatorisch bei Fragen der Finanzen, des Rechtssystems, des Außenhandels und innerer Unruhen.

1877-05-11

Großbrand in Bangkok.

1877-06-24

In einer Rede im Londoner Kristallpalast formuliert Premierminister, Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS, (1804 – 1881), den britischen Imperialismus:

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS, 1878-07-22 / von Cornelius Jabez Hughes (1819 - 1884,

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

"If you look to the history of this country since the advent of Liberalism forty years ago you will find that there has been no effort so continuous, so subtle, supported by so much energy, and carried on with so much ability and acumen, as the attempts of Liberalism to effect the disintegration of the Empire of England. And, gentlemen, of all its efforts, this is the one which has been the nearest to success. Statesmen of the highest character, writers of the most distinguished ability, the most organised and efficient means, have been employed in this endeavour. It has been proved to all of us that we have lost money by our Colonies. It has been shown with precise, with mathematical demonstration, that there never was a jewel in the Crown of England that was so truly costly as the possession of India. How often has it been suggested that we should at once emancipate ourselves from this incubus ! Well, that result was nearly accomplished. When those subtle views were adopted by the country under the plausible plea of granting self-government to the Colonies, I confess that I myself thought that the tie was broken. Not that I for one object to self-government; I cannot conceive how our distant Colonies can have their affairs administered except by self-government. But self-government, in my opinion, when it was conceded, ought to have been conceded as part of a great policy of Imperial consolidation. It ought to have been accompanied by an Imperial tariff, by securities for the people of England for the enjoyment of the unappropriated lands which belonged to the Sovereign as their trustee, and by a military code which should have precisely defined the means and the responsibilities by which the Colonies should be defended, and by which, if necessary, this country should call for aid from the Colonies themselves. It ought, further, to have been accompanied by the institution of some representative council in the metropolis, which would have brought the Colonies into constant and continuous relations with the Home Government. All this, however, was omitted because those who advised that policy and I believe their convictions were sincere looked upon the Colonies of England, looked even upon our connection with India, as a burden upon this country; viewing everything in a financial aspect, and totally passing by those moral and political considerations which make nations great, and by the influence of which alone men are distinguished from animals.

Well, what has been the result of this attempt during the reign of Liberalism for the disintegration of the Empire? It has entirely failed. But how has it failed? Through the sympathy of the Colonies for the Mother Country. They have decided that the Empire shall not be destroyed; and in my opinion no Minister in this country will do his duty who neglects any opportunity of reconstructing as much as possible our Colonial Empire, and of responding to those distant sympathies which may become the source of incalculable strength, and happiness to this land.

[...]

The issue is not a mean one. It is whether you will be content to be a comfortable England, modelled and moulded upon Continental principles and meeting in due course an inevitable fate, or whether you will be a great country, an Imperial country, a country where your sons, when they rise, rise to paramount positions, and obtain not merely the esteem of their countrymen, but command the respect of the world."

[Zitiert in: Monypenny, William Flavelle <1866-1912>: The life of Benjamin Disraeli. -- New York : MacMillan. -- Vol. 5. 1868-1876 / by Georg Earl Buckle <1854 - 1935>. -- 1920. -- S. 194 -196]

1877-07

Ein Londoner Gericht entscheidet, dass "the booklet was calculated to deprave but there was no intent to corrupt" über die von Annie Besant (1847 - 1933) und Charles Bradlaugh (1833 - 1891) herausgegebene Neuauflage von:

[Knowlton, Charles <1800 - 1850>:] The Fruits of Philosophy, or the Private Companion of Young Married People. -- 1832

Im Buch werden Methoden der Empfängnisverhütung dargestellt.

Abb.: Einbandtitel der Auflage von 1891

1877-07-09

Erstes Tennisturnier in Wimbledon (London).

Abb.: Tennisturnier Wimbledon 1877

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

1877-08-04

Die Gasmotoren-Fabrik Deutz erhält das Patent auf den von Nicolaus August Otto (1832 - 1891) erfundenen Gasmotor (Viertaktmotor). Am 1886-01-30 wird das Reichsgericht die entscheidenden Ansprüche dieses Patents für nichtig erklären.

Abb.: Früher Ottomotor

[Bildquelle: Meyers Großes Konversations Lexikon 1905]

Abb.: Prinzip eines Ottomotors

[Bildquelle: UtzOnBike / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

1877-08-10

Rama V. an Sir Andrew Clarke (1824 - 1902), Governor of Singapore:

"As for your suggestion that I should bring the Laos States [d. h. Nordsiam] under my immediate control, I doubt if even you know how great are the difficulties. There are difficulties among us Siamese and Laos and other difficulties caused by foreigners. "I can give any order I please to those states, I can bring the Chiefs down to Bangkok and detain them so long as I please. Both my father and I have ordered the Chief of Chiangmai [เชียงใหม่] to Bangkok and have detained him until the charges against him have been settled...

"I would doubtless change the customs of Chiangmai and make it a province of the inner circle. But that would be considered by all even by my own people an act of oppression and would excite much disaffection. In Bangkok there is a party consisting of members of Government and persons of education acquainted with foreign customs which believes there may be sometimes better than old custom but generally in Siam people seem to prefer old custom and oppression to new custom and no oppression.

"To make a change as you suggest, the Government must be very strong and the leading foreign representatives must be entirely free of all feeling in favour of those persons who would be looked up to as leader in case of disaffection. However truly a foreign representative might support me in certain changes, his support would not be enough if I could depend on his support throughout, or if others believed that he would not support me throughout. This is a reason I am obliged to proceed with the utmost caution in respect of those reforms which I once hoped would form a glory to my reign, but which now I fear would be only causes of intrigues, of disturbance and possibly of danger.

"There is not to be said about Chiangmai that of all the dependencies of Siam without exception, it appears to be best governed instead of being a very disorderly place. It is a very orderly one except in outlying districts. It is a thriving place where theft is rare and it might not be quite just to the Chief to make him the first to lose his present authority. Moreover probably, it would not be done without a war and great loss of lives and money.

"I believe that if the truth were known, the British Government would not be so dissatisfied."

[Zitiert in: Manich Jumsai [มานิจ ชุมสาย] <1908 - 2009>: History of Anglo-Thai relations. -- 6. ed. -- Bangkok : Chalermnit, 2000. -- 494 S. : Ill. ; 21 cm. -- S. 216ff.]

"Formerly, I proposed many reforms, now I am obliged to maintain things as they are. No improvements are possible." [Zitiert in: Battye, Noel Alfred <1935 - >: The military, government, and society in Siam, 1868-1910 : politics and military reform during the reign of King Chulalongkorn. -- 1974. -- 575 S. -- Diss., Cornell Univ. -- S. 209]

1877-08-27

Der britische Generalkonsul Thomas George Knox (1824 - 1887) an den britischen Außenminister Edward Henry Stanley, 15. Earl of Derby (1826 - 1893):

"The evils of which we have to complain in regard to the treatment of British subjects in Chiangmai [เชียงใหม่], are firstly, the numerous murders and dacoities perpetrated on them, and secondly, the absence of any judicial court before which they can lay their complaints with any prospect of a just settlement." [Zitiert in: Manich Jumsai [มานิจ ชุมสาย] <1908 - 2009>: History of Anglo-Thai relations. -- 6. ed. -- Bangkok : Chalermnit, 2000. -- 494 S. : Ill. ; 21 cm. -- S. 218]

1877-11-05

Stapellauf des französischen Kreuzers Lapérouse. Er wird in Südostasien eingesetzt werden, u.a. im Escadre de l'Extrême-Orient (184/85).

Abb.: Lapérouse in Südostasien, 1885

1877-12-24

Der US-Erfinder Thomas Alva Edison (1847 - 1931) meldet eine "Sprechmaschine" (Zinnfolien-Phonograph) als Patent an. Beginn des Zeitalters der Tonaufzeichnungen.

Abb.: Erstes Versuchmodell von Edisons Phonographen

ausführlich: http://www.payer.de/thailandchronik/ressourcen.htm

Phongpaichit, Pasuk <ผาสุก พงษ์ไพจิตร, 1946 - > ; Baker, Chris <1948 - >: Thailand : economy and politics. -- Selangor : Oxford Univ. Pr., 1995. -- 449 S. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 983-56-0024-4. -- Beste Geschichte des modernen Thailand.

Ingram, James C.: Economic change in Thailand 1850 - 1870. -- Stanford : Stanford Univ. Pr., 1971. -- 352 S. ; 23 cm. -- "A new edition of Economic change in Thailand since 1850 with two new chapters on developments since 1950". -- Grundlegend.

Akira, Suehiro [末廣昭] <1951 - >: Capital accumulation in Thailand 1855 - 1985. -- Tokyo : Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies, ©1989. -- 427 S. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 4896561058. -- Grundlegend.

Skinner, William <1925 - 2008>: Chinese society in Thailand : an analytical history. -- Ithaca, NY : Cornell Univ. Press, 1957. -- 459 S. ; 24 cm. -- Grundlegend.

Mitchell, B. R. (Brian R.): International historical statistics : Africa and Asia. -- London : Macmillan, 1982. -- 761 S. ; 28 cm. -- ISBN 0-333-3163-0

Smyth, H. Warington (Herbert Warington) <1867-1943>: Five years in Siam : from 1891 to 1896. -- London : Murray, 1898. -- 2 Bde. : Ill ; cm.

ศกดา ศิริพันธุ์ = Sakda Siripant: พระบาทสมเด็จพระจุลจอมเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว พระบิดาแห่งการถ่ายภาพไทย = H.M. King Chulalongkorn : the father of Thai photography. -- กรุงเทพๆ : ด่านสุทธา, 2555 = 2012. -- 354 S. : Ill. ; 30 cm. -- ISBN 978-616-305-569-9