|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

नामलिङ्गानुशासनम्

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 7. vanauṣadhivargaḥ IV. -- Fassung vom 2011-01-22. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa/amara207.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-01-08

Überarbeitungen: 2011-01-22 [Verbesserungen]

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

"Those who have never considered the subject are little aware how much the appearance and habit of a plant become altered by the influence of its position. It requires much observation to speak authoritatively on the distinction in point of stature between many trees and shrubs. Shrubs in the low country, small and stunted in growth, become handsome and goodly trees on higher lands, and to an inexperienced eye they appear to be different plants. The Jatropha curcas grows to a tree some 15 or 20 feet on the Neilgherries, while the Datura alba is three or four times the size in>n the hills that it is on the plains. It is therefore with much diffidence that I have occasionally presumed to insert the height of a tree or shrub. The same remark may be applied to flowers and the flowering seasons, especially the latter. I have seen the Lagerstroemia Reginae, whose proper time of flowering is March and April, previous to the commencement of the rains, in blossom more or less all the year in gardens in Travancore. I have endeavoured to give the real or natural flowering seasons, in contradistinction to the chance ones, but, I am afraid, with little success; and it should be recollected that to aim at precision in such a part of the description of plants is almost hopeless, without that prolonged study of their local habits for which a lifetime would scarcely suffice."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- S. VIII f.]

Bei der Identifikation der lateinischen Pflanzennamen folge ich, wenn immer es möglich ist:

Bhāvamiśra <16. Jhdt.>: Bhāvaprakāśa of Bhāvamiśra : (text, English translation, notes, appendences and index) / translated by K. R. (Kalale Rangaswamaiah) Srikantha Murthy. -- Chowkhamba Varanasi : Krishnadas Academy, 1998 - 2000. -- (Krishnadas ayurveda series ; 45). -- 2 Bde. -- Enthält in Bd. 1 das SEHR nützliche Lexikon (nigaṇṭhu) Bhāvamiśras.

Pandey, Gyanendra: Dravyaguṇa vijñāna : materia medica-vegetable drugs : English-Sanskrit. -- 3. ed. -- Varanasi : Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy, 2005. -- 3 Bde. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN: 81-218-0088-9 (set)

Wo möglich, erfolgt die aktuelle Benennung von Pflanzen nach:

Zander, Robert <1892 - 1969> [Begründer]: Der große Zander : Enzyklopädie der Pflanzennamen / Walter Erhardt ... -- Stuttgart : Ulmer, ©2008. -- 2 Bde ; 2103 S. -- ISBN 978-3-8001-5406-7.

WARNUNG: dies ist

der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen Textes. Es

ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier genannten

Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut

ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen machen!

Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen kompetenter

Āyurvedaspezialisten.

WARNUNG: dies ist

der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen Textes. Es

ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier genannten

Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut

ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen machen!

Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen kompetenter

Āyurvedaspezialisten.

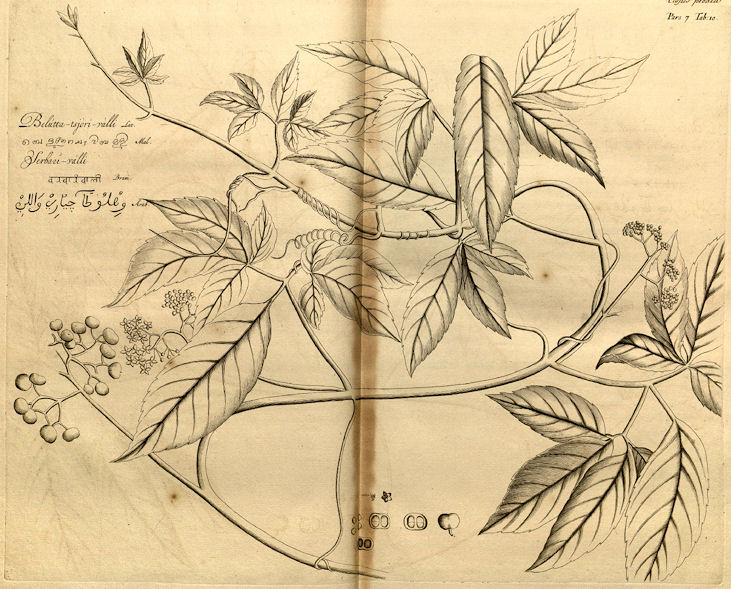

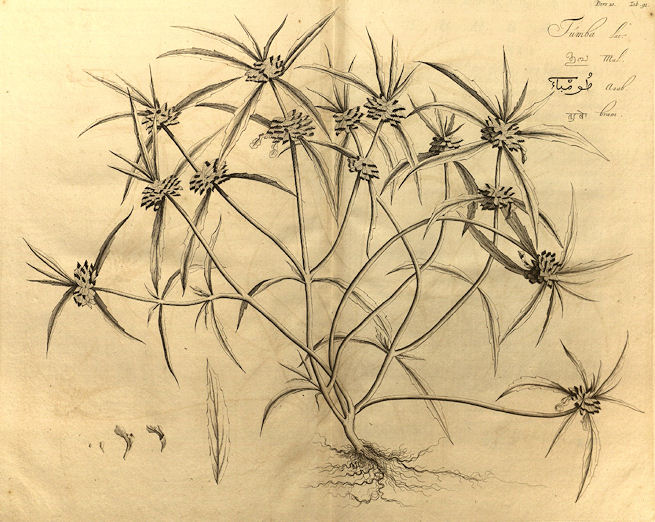

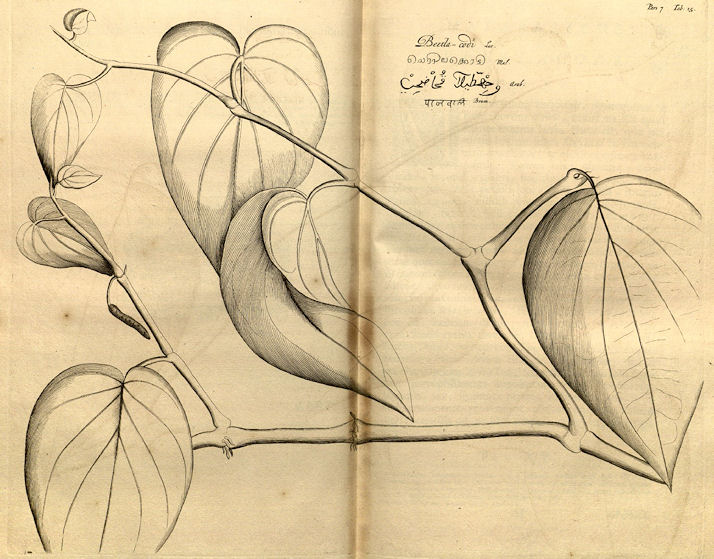

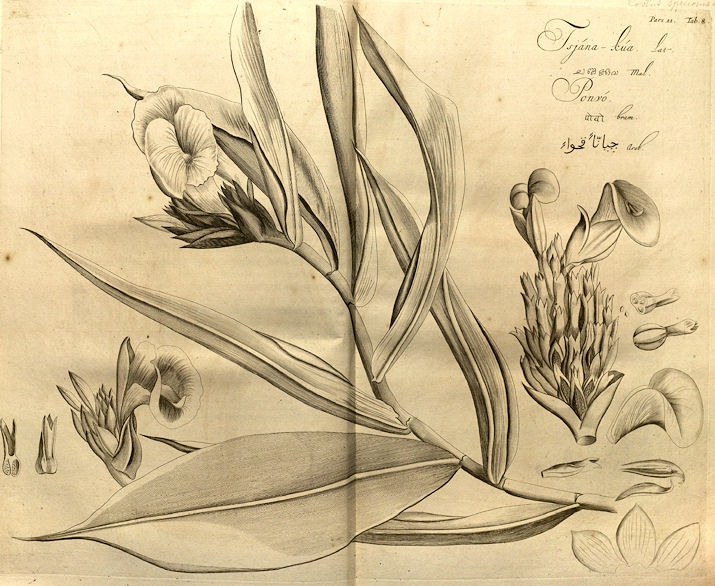

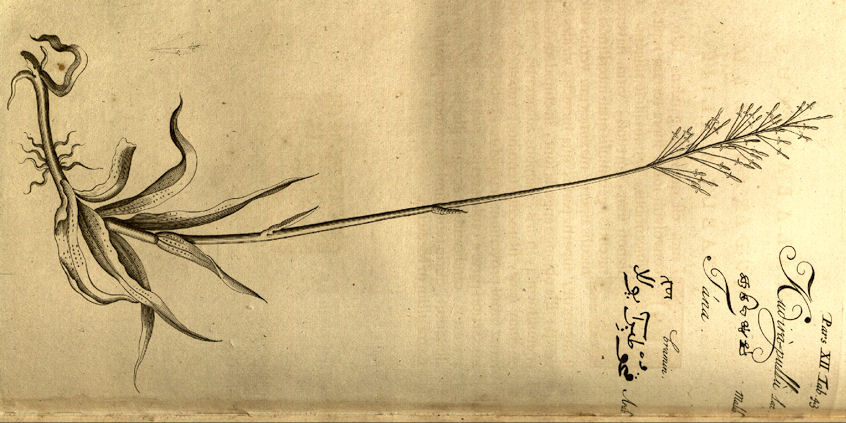

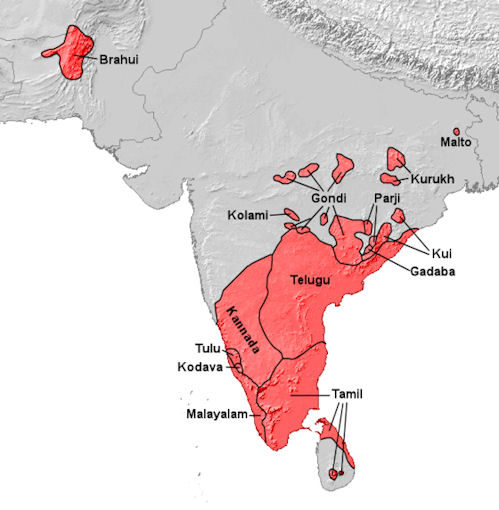

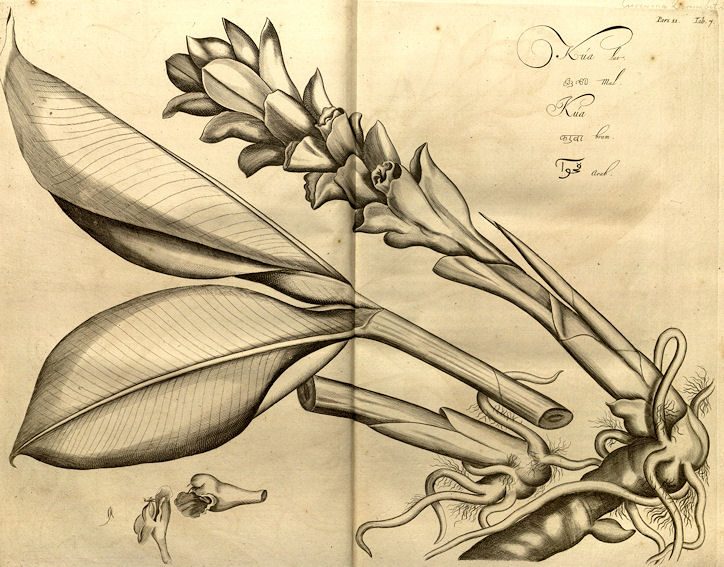

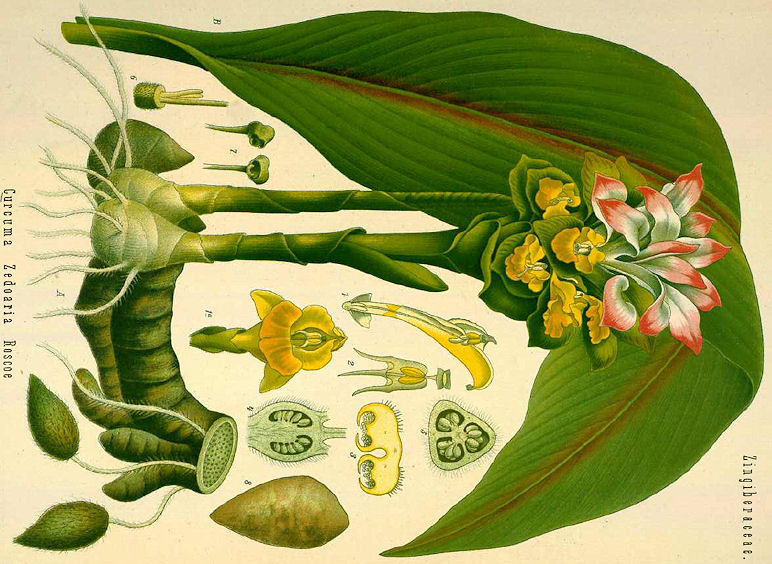

Hortus malabaricus

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus : continens regni Malabarici apud Indos cereberrimi onmis generis plantas rariores, Latinas, Malabaricis, Arabicis, Brachmanum charactareibus hominibusque expressas ... / adornatus per Henricum van Rheede, van Draakenstein, ... et Johannem Casearium ... ; notis adauxit, & commentariis illustravit Arnoldus Syen ... -- 11 Bde. -- Amstelaedami : sumptibus Johannis van Someren, et Joannis van Dyck, 1678-1703. -- Online: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/b11939795. -- Zugriff am 2010-01-01

Zu den Identifikationen siehe:

Dillwyn, L. W. (Lewis Weston) <1778-1855>: A review of the references to the Hortus malabaricus of Henry Van Rheede Van Draakenstein [sic]. -- Swansea : Printed at the Cambrian-Office, by Murray and Rees, 1839.

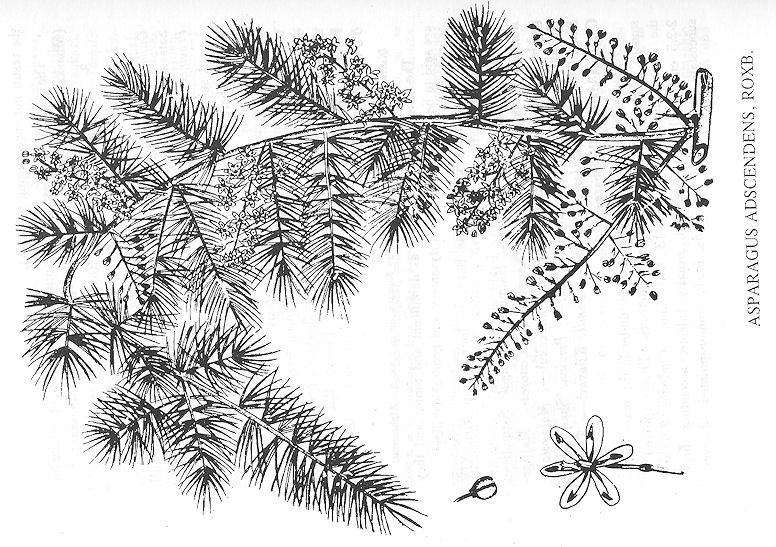

Roxburgh

Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Plants of the coast of Coromandel, selected from drawings and descriptions presented to the hon. court of directors of the East India company / by William Roxburgh. Published by their order under the direction of Sir Joseph Banks <1743 - 1820> ... -- London : Printed by W. Bulmer for G. Nicol, 1795-1819. -- 3 Bde. : 300 kolorierte Tafeln ; 59 cm. -- Online: http://www.botanicus.org/title/b12006488 usw. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-19

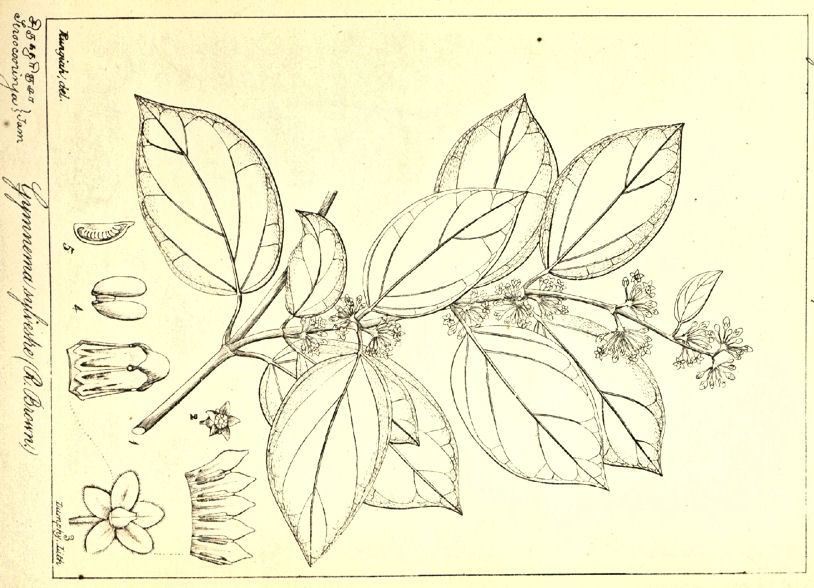

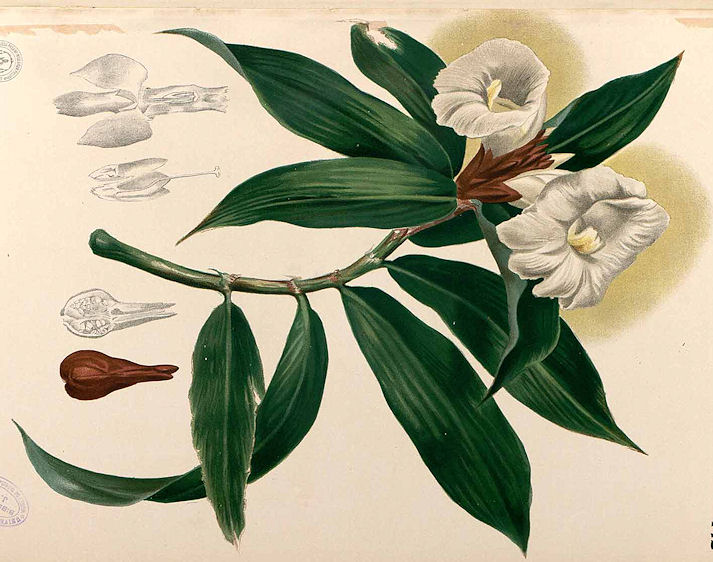

Wight Icones

Wight, Robert <1796 - 1872>: Icones plantarum Indiae Orientalis :or figures of Indian plants. -- 6 Bde. -- Madras : published by J.B. Pharoah for the author, 1840-1853. -- Online: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/92. -- Zugriff am 2010-01-01

Wight Illustrations

Wight, Robert <1796 - 1872>: Illustrations of Indian botany :or figures illustrative of each of the natural orders of Indian plants, described in the author's prodromus florae peninsulae Indiae orientalis. -- 2 Bde. + Suppl. -- Madras : published by J. B. Pharoah for the author, 1840-1850. -- Online: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/9603. -- Zugriff am 2010-01-01

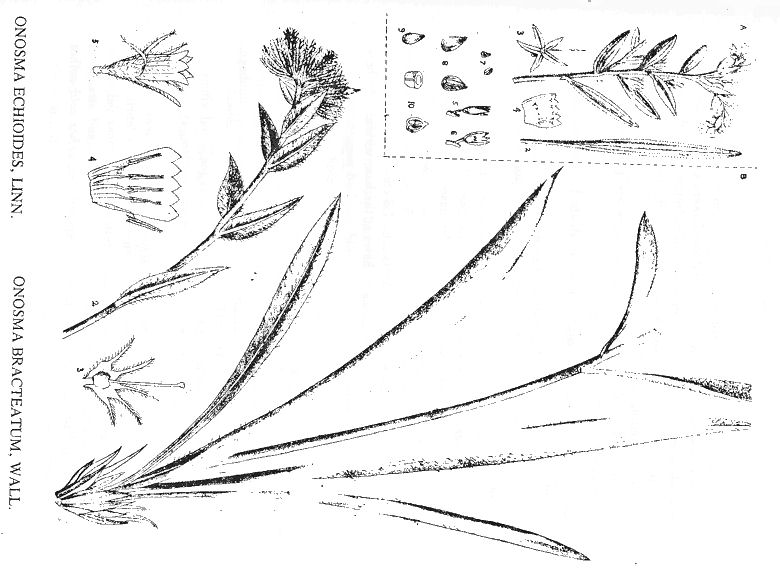

Kirtikar-Basu

Kirtikar, K. R. ; Basu, B. D.: Indian medical plants with illustrations. Ed., revised, enlarged and mostly rewritten by E. Blatter, J. F. Caius and K. S. Mhaskar. -- 2. ed. -- Dehra Dun : Oriental Enterprises. -- 2003. -- 11 Bde : 3846 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- Unentbehrlich! -- Reprint der Ausgabe von 1933, die Abbildungen stammen aus der Ausgabe von 1918

Musaceae (Bananengewächse)

| 1. kadalī vāraṇabusā rambhā

mocāṃśumatphalā kāṣṭhīlā mudgaparṇī tu kākamudgā sahety api कदली वारणबुसा रम्भा

मोचांशुमत्फला । [Bezeichnungen für Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 - Ess-Banane - Edible Banana:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A banana. Musa sapientum [L. = Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753."

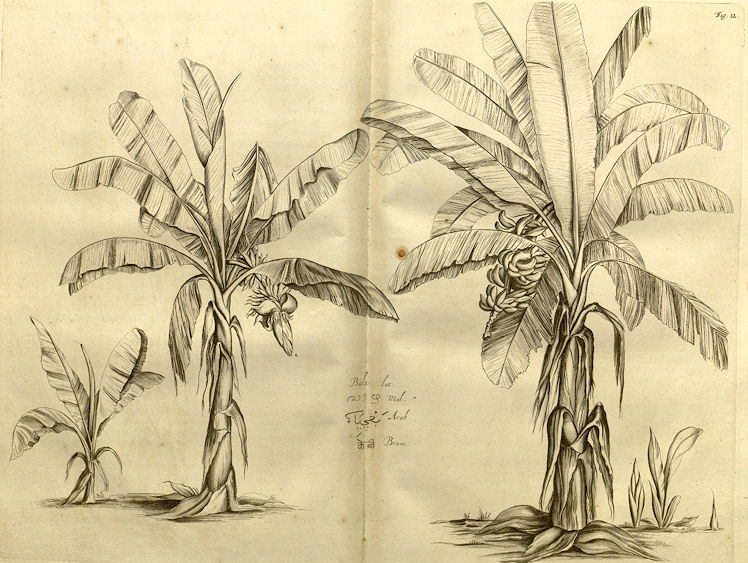

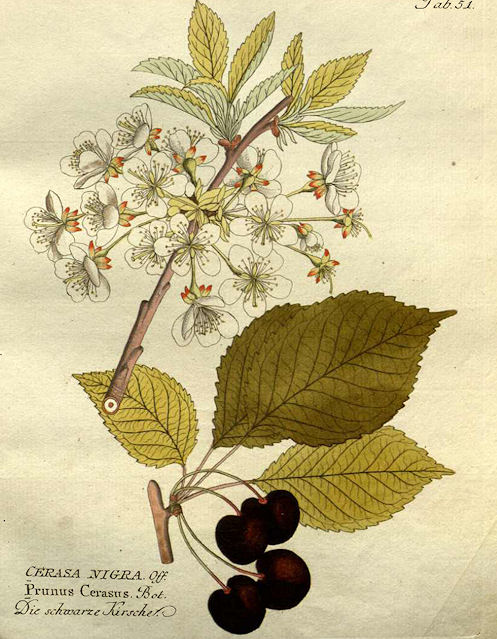

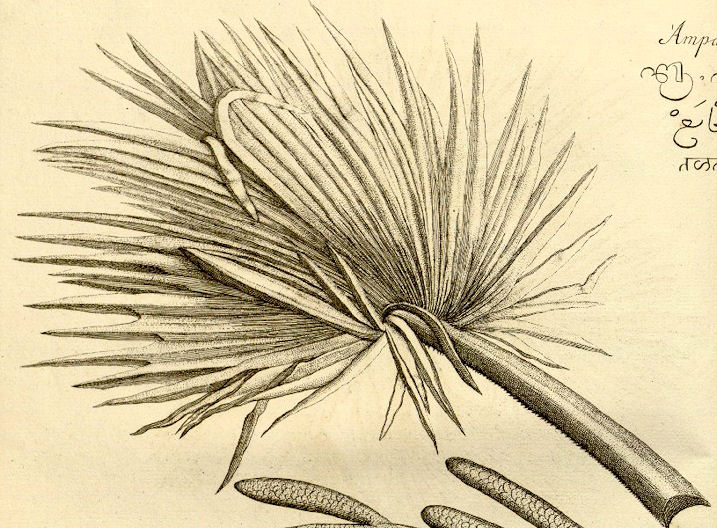

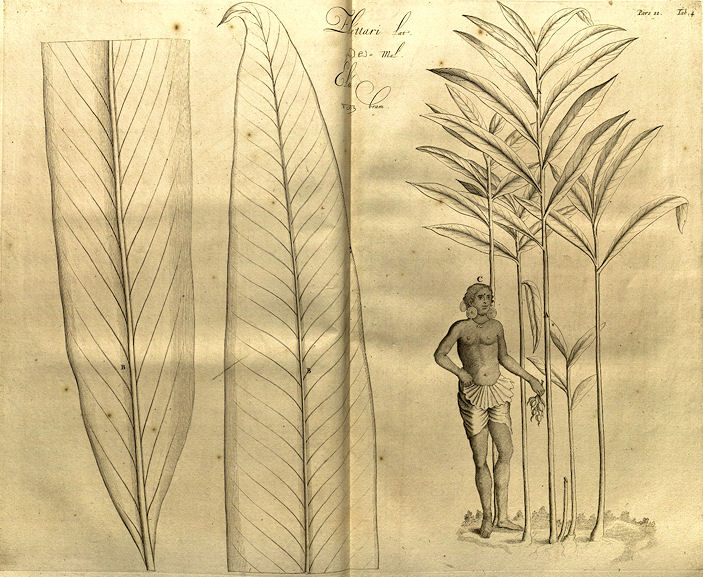

Abb.: वारणबुसा । Musa x paradisiaca L.

1753 - Ess-Banane - Edible Banana

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus I. Fig. 12, 1678]

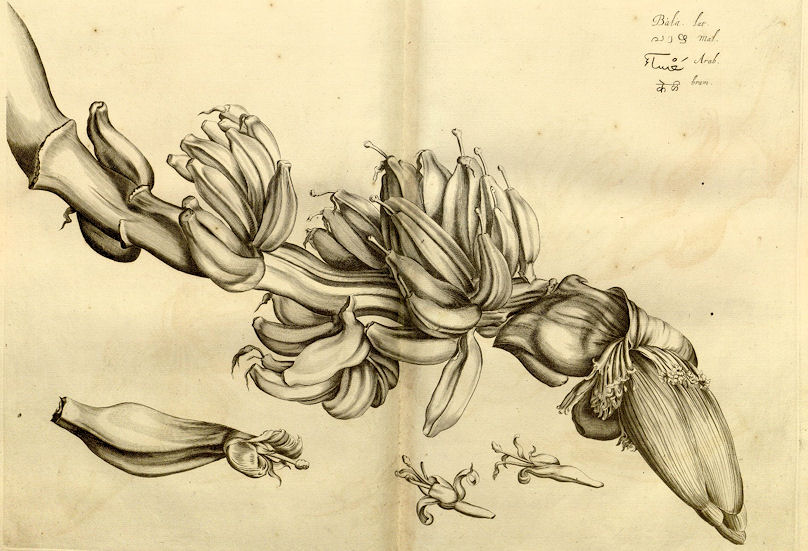

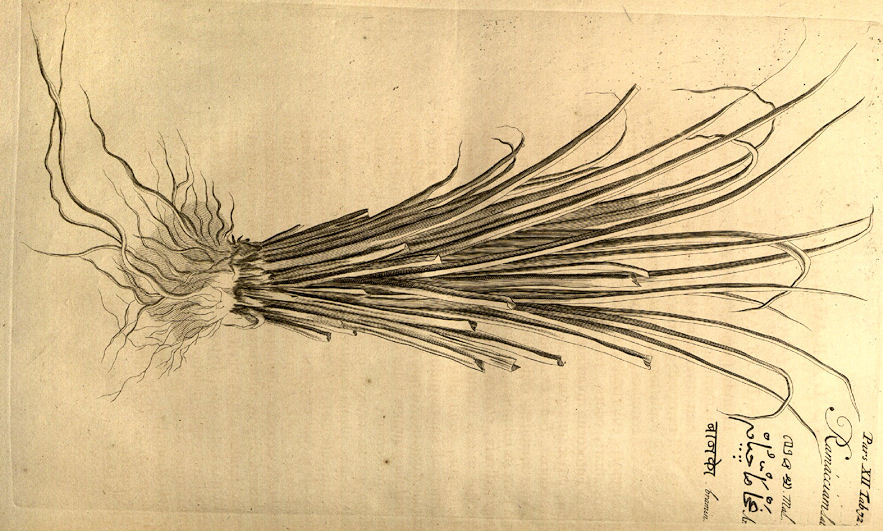

Abb.: रम्भा । Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 -

Ess-Banane - Edible Banana

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus I. Fig. 13, 1678]

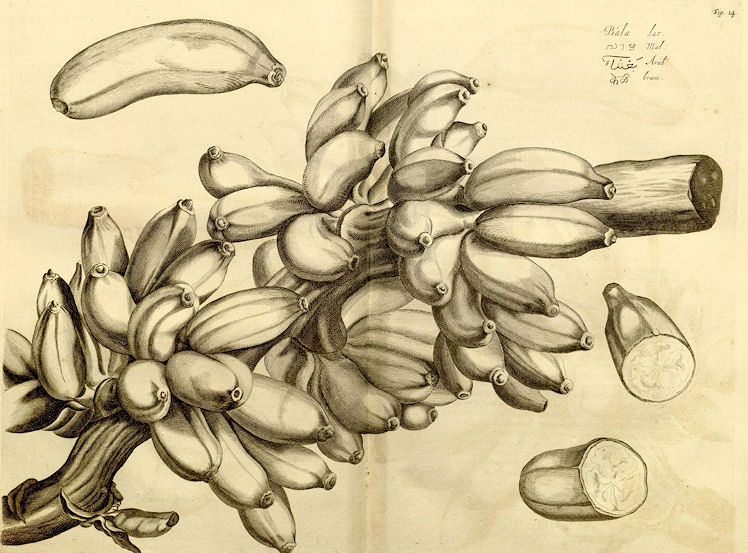

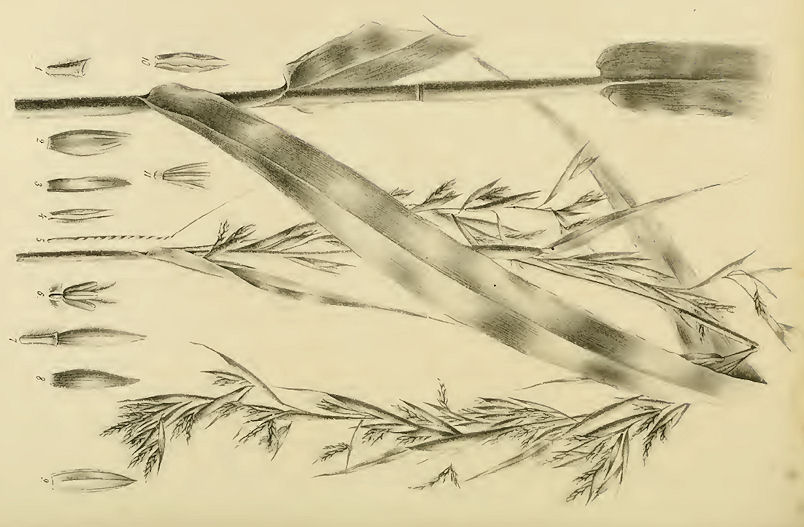

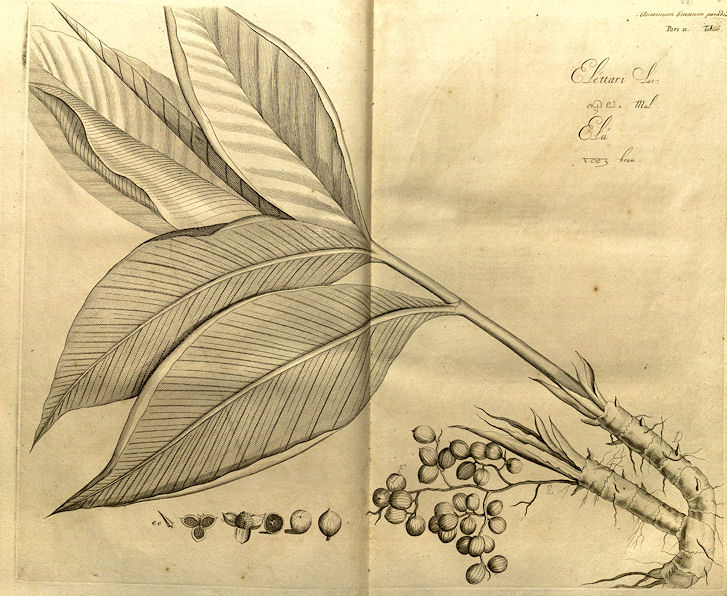

Abb.: कदली । Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 -

Ess-Banane - Edible Banana

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus I. Fig. 14, 1678]

Abb.: Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 - Ess-Banane - Edible

Banana

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas, 1880

/ Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 -

Ess-Banane - Edible Banana

[Bildquelle: Roxburgh. -- Vol III. -- 1819. -- Image courtesy Missouri Botanical

Garden. http://www.botanicus.org. --

Creative Commons Lizenz

(Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: अंशुमत्फला ।

Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 - Ess-Banane - Edible Banana, Trivandrum -

തിരുവനന്തപുരം,

Kerala

[Bildquelle:

Adam

Jones. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/adam_jones/3773748783/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-19. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Blüte von

Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 - Ess-Banane - Edible Banana

[Bildquelle: Muhammad Mahdi Karim / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: काष्ठीला ।

Wildbanane

[Bildquelle: Warut Roonguthai / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Bananenblatt als Essteller, Karnataka

[Bildquelle: Pamri / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Bananen als Opfergabe an den Fluss Kaveri (காவிரி)

in Tiruchirappalli -

திருச்சிராப்பள்ளி,

Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: P.Periyannan / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

"Musa sapientum. Willd. spec. iv. p. 894.

[...]

Bata. Rheed. Mal. i. 17. t. 12, 13, and 14.

Musa. Rumph. Amb. v. 130. t. 894.

[...]

The varieties of the banana, cultivated over India, are very numerous, but fewer of the plantain, as I have hither to obtained knowledge of only three ; whereas, I may safely say, not less than ten times that number of the former have come under my inspection.

Their duration, culture, habit, and natural character are already well known; I shall therefore confine myself to (what I think,) the original wild Musa, from which I conclude all the cultivated varieties of both plantain and banana proceed, and which I consider as varieties of that one species.

In the course of two years, from the seed received from Chittagong, these attained to the usual height of the cultivated sorts which is about ten or twelve feet. They blossom at all seasons, though generally during the rains ; and ripen their seed in five or six months afterwards ; the plant then perishes down to the root, which long before this time has produced other shoots; these continue to grow up, blossom, &c. in succession for several years. Their leaves are exactly as in the cultivated sorts.

[...]

Berry oblong, tapering to each end ; of a soft fleshy consistence, smooth and yellow, marked longitudinally with five ribs, three-celled ; the partitions distinct, but soft and pulpy, and no doubt disappear when dry, and long kept. Seeds numerous, the size of a small pea, round, turbinate, tubercled ; the exterior half dark-chesnut or blackish toward the umbilicus, which is a large circular cavity ; light brown."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 1, S. 663ff.]

"Musa paradisiaca (Linn.) N. O. Musaceae. Common Plantain

Description.—Herbaceous; [...] flowers yellowish whitish.

Fl. All the year.

M. sapientum, Roxb. Fl. Ind. i. 663.—Cor. iii. 275.—Rheede, i. t. 12-14.

Cultivated everywhere. Chittagong.

Medical Uses.—The tender leaves are in common use for dressing blistered surfaces. For this purpose a piece of the leaf, of the required size, smeared with any bland vegetable oil, is applied to the denuded surface, and kept on the place by means of a bandage. The blistered surface is generally found to heal after four or five days. For the first two days the upper smooth surface of the leaf is placed next the skin, and subsequently the under side, until the healing process is complete. This is considered better than the usual mode of treatment with spermacetti ointment. Dr Van Someren occasionally employed the plantain leaf as a substitute for gutta-percha tissue in the water-dressing of wounds and ulcers, and found it answer very well. A piece of fresh plantain leaf forms a cool and pleasant shade for the eyes in the various forms of ophthalmic so common in the East. The preserved fruit, which resembles dried figs, is a nourishing and antiscorbutic article of diet for long voyages. In this state they will keep for a long time.—(Pharm. of India.) Long, in his History of Jamaica, says that on thrusting a knife into the body of the plant the astringent lumped water that issues out is given with great success to persons subject to spitting blood, and in fluxes.

Economic Uses.—This extensively cultivated plant is common to both Indies. The ancients were acquainted with the fruit; and the name of Pala, which is used in Pliny's description of it, is identical with the word Vala, which is the Malayalum name to the present day. Probably all the cultivated varieties in this country have sprung from a single species, of which the original, according to Dr Roxburgh, was grown from seeds procured from Chittagong. A wild variety, probably the M. superba, which is found in the Dindigul valleys, I have often met with on the mountains in Travancore, at high elevations.

In the Himalaya it is cultivated at 5000 feet, and may be found wild on the Neilgherries at 7000 feet. It is cultivated in Syria as far as latitude 34°, but, Humboldt says, ceases to bear fruit at a height of 3000 feet, where the mean annual temperature is 68°, and where, probably, the heat of summer is deficient. Lindley enumerates ten species of Musa, some of which grow to the height of 25 or 30 feet, but the Chinese species (M. Chinensis or Cavendishii) does not exceed 4 or 5 feet in height. The specific name of the plant under consideration was given by botanists in allusion to an old notion that it was the forbidden fruit of Scripture. It has also been supposed to be what was intended by the grapes, one branch of which was borne upon a pole between two men that the spies of Moses brought out of the Promised Land. The plantain is considered very nutritious and wholesome, either dressed or raw; and no fruit is so easily cultivated in tropical countries. There is hardly a cottage in India that has not its grove of plantains. The natives live almost upon them; and the stems of the plantain, laden with their branches of fruit, are invariably placed at the entrance of their houses during their marriage or other festivals, appropriate emblems of plenty and fertility. Its succulent roots and large leaves are well adapted for keeping the ground moist, even in the hottest months. The best soil for its cultivation is newly-cleared forest-land where there is much decayed vegetation. Additional manure will greatly affect the increase and flavour of the fruit. Some of the varieties are far inferior to the rest; the Guindy plantains are the best known in Madras, which, though small, are of delicious flavour. The plant must be cut down immediately after the fruit is gathered; new shoots spring up from the old stems; and in this way it will grow on springing up and bearing for twenty years or more. In America and the Society Isles the fruit is preserved as an article of trade. A meal is prepared from the fruit, by stripping off the skins, slicing the core, and, when thoroughly dried in the sun, powdering and sifting it. It is much used in the West Indies for infants and invalids, and is said to be especially nourishing. Regarding its nutritive qualities, Professor Johnston published the following information in the ' Journal of the Agricultural Society of Scotland:' " We find the plantain fruit to approach most nearly in composition and nutritive value to the potato, and the plantain meal to those of rice. Thus, the fruit of the plantain gives 37 per cent, and the raw potato 25 per cent of dry matter. In regard to its value as a food for man in our northern climates, there in no reason to believe that it is unfit to sustain life and health; and as to warmer or tropical climates, this conclusion is of more weight. The only chemical writer who has previously made personal observations upon this point (M. Boussingault) says, ' I have not sufficient data to determine the nutritive value of the banana, but I have reason to believe that it is superior to that of potato. I have given as rations to employed at hard labour about 6 1/2 lb. of half-ripe bananas and 2 ounces of salt meat.' Of these green bananas he elsewhere states that 38 per cent consisted of husk, and that the internal eatable part lost 56 per cent of water by drying in the sun. The composition of the ash of the plantain also bears a close resemblance to that of potato. Both contain much alkaline matter, potash, and soda salts; and in both there is nearly the same percentage of phosphoric acid and magnesia. In so far, therefore, as the supply of those mineral ingredients is concerned, by which the body is supported as necessarily as by the organic food, there is no reason to doubt the banana, equally with the potato, is fitted to sustain the strength of the animal body."

Dried plantains form an article of commerce at Bombay and other parts of the Peninsula. They are merely cut in slices and dried in the sun, and being full of saccharine matter, make a good preserve for the table. Exports from the former place to the extent of 267 cwt., valued at rupees 1456, were shipped in 1850-51. The juice of the unripe fruit and lymph of the stamens are slightly astringent In the West Indies the latter has been used as a kind of marking ink.

All the species of Musa are remarkable for the number of the spiral vessels they contain, and one species (M. textilis) yields a fine kind of flax, with which a very delicate kind of cloth is fabricated. The plantain fibre is an excellent substitute for hemp in linen thread. The fine grass cloth, ship's cordage and ropes, which are made and used in the South Sea fisheries, are made from it. The outer layers of the sheathing foot-stalks yield the thickest and strongest fibres. It is considered that there would be no difficulty in obtaining from this plant alone any required quantity of fibre, of admitted valuable quality, which might be exported to Europe. It can be used with no less facility and advantage in the manufacture of paper. A profitable export made of plantain and aloe fibre has been established on the western coast. The best mode of preparing the fibre is thus given by Dr Hunter :—

"Take the upright stem and the central stalk of the leaves; if the outer ones are old, stained, or withered, reject them; strip off the different layers, and proceed to clean them, in shade if possible, soon after the tree has been cut down. Lay a leaf-stalk on a long flat board with the inner surface uppermost, scrape the pulp off with a blunt piece of hoop-iron fixed in a grove in a long piece of wood. (An old iron spoon makes a very good scraper.) When the inner side, which has the thickest layer of pulp, has been cleaned, turn over the leaf and scrape the back of it. When a good bundle of fibres has been thus partially cleaned and piled up, wash it briskly. in a large quantity of water, rubbing it all well and shaking it about in the water, so as to get rid of all the pulp and sap as quick as possible. Boiling the fibres in an alkaline ley (potash or soda dissolved in water), or washing with Europe soap, gets rid of the sap quickly. The common country soap, which is made with quicklime, is too corrosive to be depended upon. After washing the fibres thoroughly, spread them out in very thin layers, or hang them up in the wind to dry. Do not expose the fibres to the sun when damp, as this communicates a brownish-yellow tinge to them, which cannot be easily removed by bleaching. Leaving the fibres out at night in the dew bleaches them, but it is at the expense of part of their strength. All vegetable substances are apt to rot if kept long in a damp state."

In the Jury Reports of the Madras Exhibition it is stated : "It yields a fine white silky fibre of considerable length, especially lighter than hemp, flax, and aloe fibre, by one-fourth or one-fifth, and possessing considerable strength. There are numerous varieties of the plantain, which yield fibres of different qualities, viz.:—

- Rustaley, superior table plantain.

- Poovaley, or small Guindy variety.

- Payvaley, a pale ash-coloured sweet fruit.

- Monden, 3-sided coarse fruit.

- Shevaley, large red fruit.

- Putchay Laden, or long curved green fruit

"These varieties, as might be expected, yield fibres of very different quality. This plant has a particular tendency to rot, and to become stiff, brittle, and discoloured, by steeping in the green state; and it has been ascertained by trial that the strength is in proportion to the cleanness of the fibre. If it has been well cleaned, and all the sap quickly removed, it bears immersion in water as well as most other fibres, and is about the same strength as Russian hemp. The coarse large-fruited plantains yield the strongest and thickest fibres; the smaller kinds yield fine fibres, suited for weaving, and if carefully prepared, these have a glossy appearance like silk. This gloss, however, can only be got by cleaning rapidly, and before the sap has time to stain the fibre; it is soon lost if the plant be steeped in water."

In Dr Royle's experiments on its strength, some prepared at Madras broke at 190 lb., that from Singapore at 390 lb., a 12- thread rope broke at 864 lb.; proving that it is of great strength, and applicable to cordage and rough canvas. Perhaps its value in the European markets might be £50, or at any rate £35 a-ton the coarser fibres, if sent in sufficient quantity and in a proper state. Respecting the manufacture of paper from the plantain fibres, the subjoined information is selected from Dr Royle's memorandum :—

"Among cultivated plants there is probably nothing so well calculated to yield a large supply of material, fit for making paper of almost every quality, as the plantain, so extensively cultivated in all tropical countries on account of its fruit, and of which the fibre- yielding stems are applied to no useful purpose. As the fruit already pays the expenses of the culture, this fibre could be afforded at a cheap rate, as from the nature of the plant consisting almost only of water and fibre, the latter might easily be separated. One planter calculates that it could be afforded for £9, 13s. 4d. per ton. Some very useful and tough kinds of paper have been made in India from the fibres of the plantain, and some of finer quality from the same material both in France and in the country."

Plantains and bananas are mere varieties of the same plant.— Roxb. Royle, Fib. Plants. Simmonds. Indian Journal of Arts and Sciences."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"MUSA PARADISIACA, Linn.

Fig.—Roxb. Cor. Pl. iii., t. 275; Rheecle, Hort. Mal. i. tt. 12—14.

Plantain

Hab.—Cultivated throughout India.

[...]

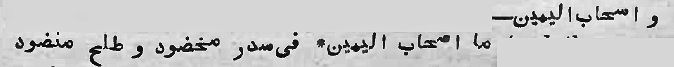

History, Uses, &c.—The cultivated plantains are called Kadali in Sanskrit, and the wild plantains, which, we believe, to be their progenitors, such as Bhānuphala or Ansumatphala "having luminous fruit," Chāruphala "having delicious fruit," Rājeshtha "liked by kings," Vana-lakshmi "beauty of the woods," &c. We think there can be little doubt that the plantain has been under cultivation in India from prehistoric times. The Greeks under Alexander must have become acquainted with it; Theophrastus and Pliny describe a tree called Pala, with leaves like the wing of a bird, three cubits in length, which puts forth its fruit from the bark, a fruit remarkable for the sweetness of its juice, a single one (bunch?) containing sufficient to satisfy four persons; this tree is supposed to have been the plantain. The word pāla signifies "leaves," but we are not aware of its ever having been applied to the plantain. The Arabs call it Mauz and Talk, and under the latter name it is mentioned in the Koran

(and the companions of the right hand, happy companions of the right hand among Lotus trees free from thorns, and plantains with their lapping clusters of fruit).

Under the name of Mauz, Mosne describes the fruit as useful in soreness of the throat and chest with dry cough, and in irritability of the bladder; he considers it to be aphrodisiac, diuretic and aperient, and recommends it to be cooked with sugar and honey. Eaten in excess it gives rise to indigestion. Abu Hanifeh in the 9th century described very accurately the manner of growth of the plantain, and quotes a saying of Ash'ab, to his son, as related by As, "Wherefore dost thou not become like me?" to which he answered, "Such as I is like the Mauzah, which does not attain to a good state until its parent dies." (Madd-el-kamus.) The early Italian travellers called the plant Fico d' Adamo, and thought they saw in the transverse section of the fruit a cross or even a crucifix. Mandeville calls it the Apple of Paradise. The varieties of the plantain are very numerous; Rumphius describes sixteen (Herb. Amb., viii., 2). Some of these, like the large yellow Manyel, are only used after they have been cooked; others, as the Iclāhi, are small and delicate in flavour. The abortive flowers at the end of the spike are removed and used as a vegetable by the Hindus, and the unripe fruit, called Mochaka in Sanskrit, is used medicinally on account of its astringent properties in diabetes; it is made into a ghrita with the three myrobalans and aromatics. Young plantain leaves are universally used as a cool dressing for blisters and to retain the moisture of water dressings; they serve also as a green shade for the eyes. Emerson notices the use of the sap to allay thirst in cholera. Mīr Muhammad Husain in the Makhzan tells us that the centre of the stem, Kanjiyāl, is eaten with fish as a vegetable in Bengal, that the kind called Mālbhok is used as a poultice to burns, and that called Bolkad is boiled and used as an ointment to the syphilitic eruptions of children; he also notices the use of the ashes on account of their alkaline properties, and of the root as an anthelmintic. MM. Corre and Lejanne state that the fruit stems sliced and macerated in water all night, yield a sudorific drink; and that the charcoal of the skin of the fruit is recommended by Chevalier as an application to the cracks in the sole of the foot from which Negroes suffer. Pereira (Mat. Med., ii., p. 222) has drawn attention to the nutritive properties of the meal prepared from the fruit. In India the lower portion of the stem of the wild plantain is a valuable resource in famine seasons on account of the large quantity of starch it contains. Starch prepared from the unripe fruit is used in the treatment of bowel complaints in Bengal. A specimen we examined consisted almost wholly of pure starch, with a trace of astringent extractive. In America syrup of bananas is said to be singularly effective in relieving chronic bronchitis. The preparation is simple, requiring only that the fruit shall be cut in small pieces and with an equal weight of sugar be placed in a closed jar, which is set in cold water and slowly heated to the boiling point, when it is to be removed from the fire and allowed to pool. The dose mentioned is a teaspoonful every hour.

Commerce.- Dried plantains are an article of commerce in India, and are excellent when stewed with sugar or fried in butter. Bombay exports annually from 300 to 400 cwts."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 443ff.]

Fabaceae (Hülsenfrüchtler)

| 1. c./d.

kāṣṭhīlā mudgaparṇī tu kākamudgā

sahety api काष्ठीला मुद्गपर्णी तु काकमुद्गा सहेत्य् अपि ॥१ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Vigna aconitifolia (Jacq.) Maréchal 1969 - Mattenbohne - Mat Bean / Moth Bean:]

|

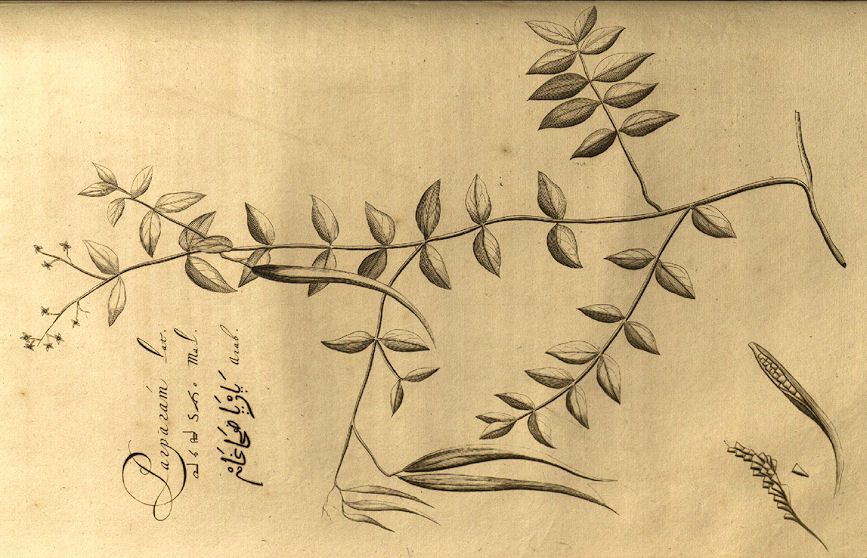

Colebrooke (1807): "Mugani"

"Phaseolus aconitfolius. Willd, iii. 1034.

Annual, diffuse.

[...]

This plant I have reared from seed sent me by Dr. Hunter from the province of Oude where it is much cultivated, as it also is over the adjoining- provinces to the westward, and used for feeding cattle ; seed-time there, June and July ; harvest in November.

Root annual, [...]

The uncommon luxuriance of this plant gives reason to think it will yield a much larger crop of fodder than any other I am acquainted with."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 299f.]

Solanaceae (Nachtschattengewächse)

| 2. a./b. vārtākī hiṅgulī siṃhī bhaṇṭākī

duṣpradharṣiṇī वार्ताकी हिङ्गुली सिंही भण्टाकी दुष्प्रधर्षिणी ।२ क। [Bezeichnungen für Solanum violaceum Ortega 1798:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Egg plant. Solanum melongena [L. 1753 - Aubergine]."

Solanum violaceum Ortega 1798

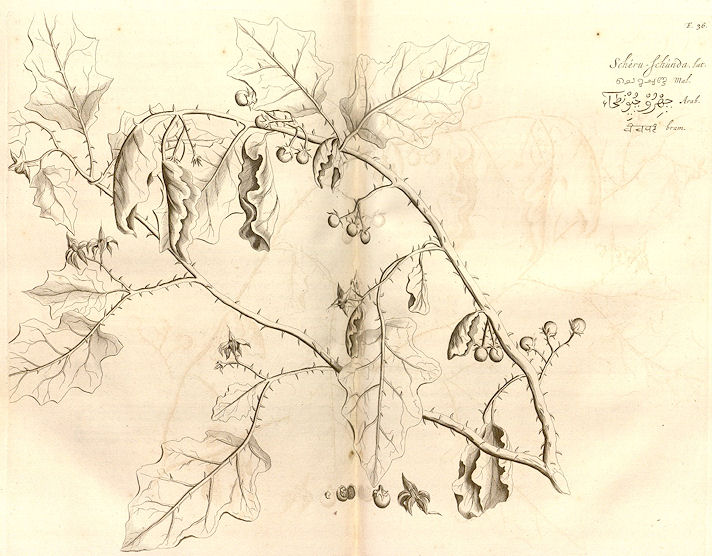

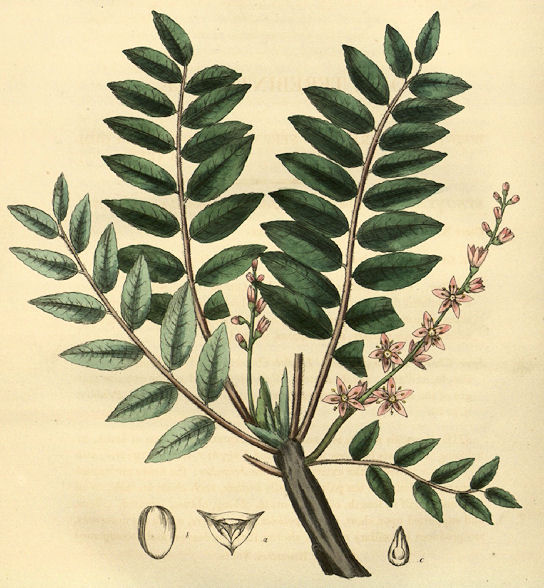

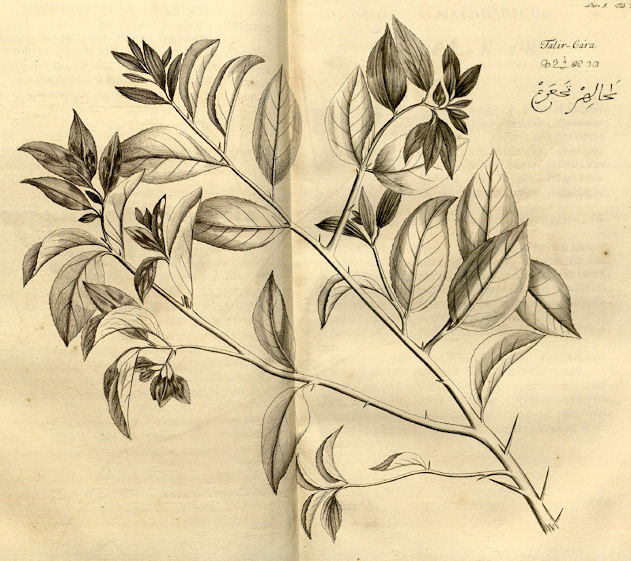

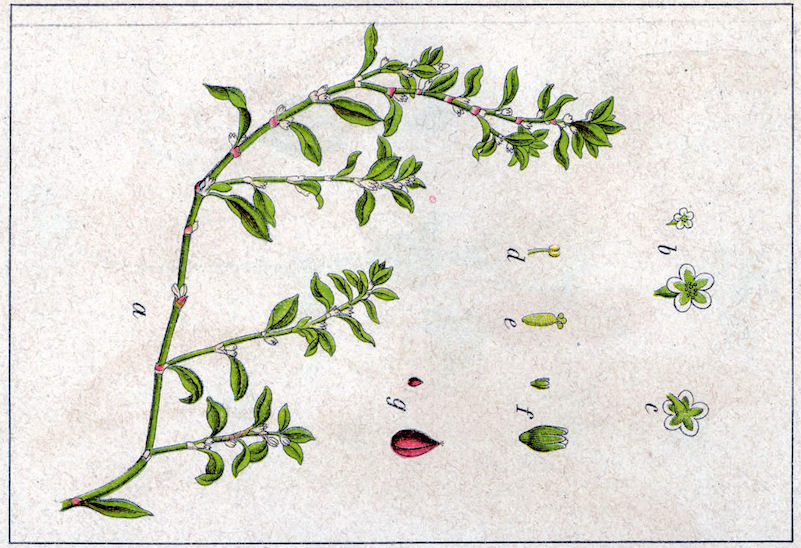

Abb.: दुष्प्रधर्षिणी ।

Solanum

violaceum Ortega 1798

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus II.

Fig. 36, 1679]

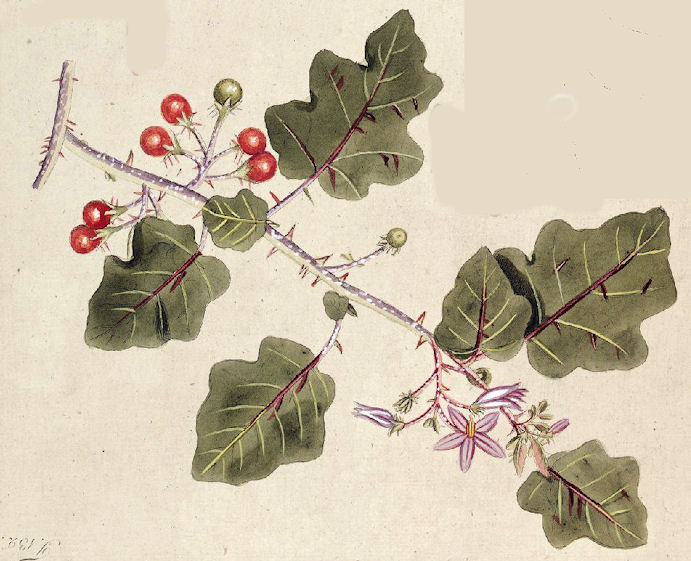

Abb.: हिङ्गुली ।

Solanum

violaceum Ortega 1798

[Bildquelle: Fragmenta botanica, figuris coloratis illustrata : ab anno 1800 ad

annum 1809 per sex fasciculos edita / opera et sumptibus Nicolai Josephi Jacquin.

-- Wien, 1809. -- Tafel 132.]

"Solanum indicum. Willd. sp. i. 1042.

Shrubby, armed, very ramous.

[...]

Cheru-chunda. Rheed. Mal. ii. t. 36.

Solanum fructescens, &c. Burm. Zeyl. p. 220. t. 102, is a pretty good representation of this plant, but I think Dillenius's S. indicum spinosum flore boragineo, t. 270. f. 349. must have been taken from a very different species, the flowers being much too large, and the leaves too deeply divided for our East Indian plant."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 1, S. 570.]

"Solanum indicum (Linn.) N. O. Solanaceae

Indian Nightshade. [...]

Description. -- Shrub, armed; [...] berries orange yellow.

Fl. Nearly all the year.— Wight Icon. t. 346—Roxb. Fl. Ind. i. 570.—Rheede, ii. t. 36.

All over India.

Medical Uses.—The root is used by Indian doctors in cases of dysuria and ischuria, in the form of decoction. It is said to possess strong exciting qualities, if taken internally, and is employed in difficult parturition. It is also used in toothache. There are varieties of the plant, differing chiefly in the shape of the leaves. —Ainslie."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"Solanum indicum

Hab.—Throughout India.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—This plant is of importance in Hindu medicine as the source of one of the drugs required for the preparation of the Dasamula Kvatha. In the Nighantas it bears the Sanskrit names of Bhantaki, Vrihati, Mahati, "large egg plant," Vārtāki, Mahotika, &c; and is described as cardiacal, aphrodisiacal, astringent, carminative and resolvent; useful in asthma, cough, chronic febrile affections, worms, &c The author of the Makhza-el-adwiya notices it under the name of Birhatta, and repeats what the Hindu writers say about it. Chakradatta gives the following prescription as useful in bronchitis with fever: Take of the roots of S. indicum, S. xanthocarpum, Sida cordifolia, and Justicia adhatoda, raisins one part, and prepare a decoction in the usual manner. Rheede notices its use in Malabar, and Ainslie (ii., 207) remarks that the root has little sensible taste or smell, but is amongst the medicines which are prescribed in cases of dysuria and ischuria in decoction to the quantity of half a teacupful twice daily. He also notices that Horsfield in his account of Java medicinal plants says, that the root taken internally, possesses strongly exciting qualities, and that Rumphius states tha it is employed in difficult parturition. The berries, which are bitter, are sometimes cooked and eaten by the natives of India as a vegetable."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 555f.]

Solanum melongena L. 1753 - Aubergine

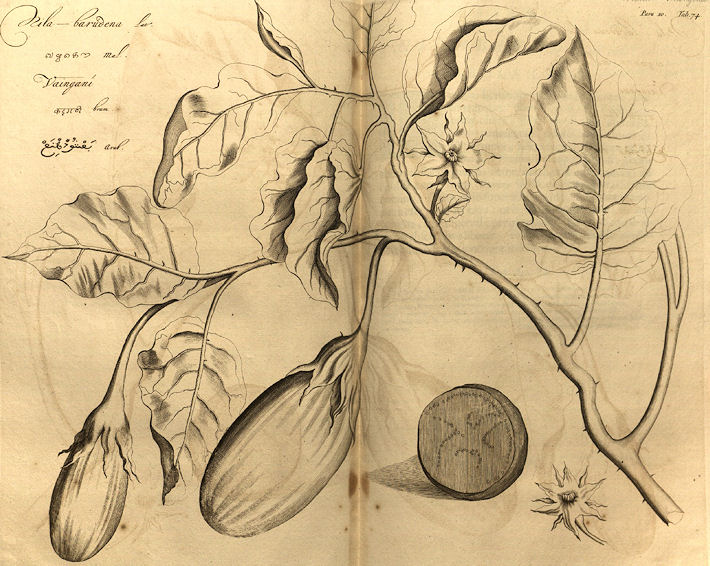

Abb.: Solanum melongena L. 1753 - Aubergine

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus X. Fig. 74, 1690]

Abb.: Solanum

melongena L. 1753 - Aubergine

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas, 1880 / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Solanum

melongena L. 1753 - Aubergine

[Bildquelle: Noumenon / Wikimedia commons. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Solanum

melongena L. 1753 - Aubergine

[Bildquelle: laminfo / Wikimedia commons. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Solanum

melongena L. 1753 - Aubergine, Thailand

[Bildquelle: Mattes / Wikipedia commons. -- Public domain]

"Solanum Melongena. Willd. sp. i. 1036.

Perennial. [...]

Nila-Barudena. Rheed. Mal. x. 147. t. 74.

Trongum hortense. Rumph. Amb. v. 238. t. 85.

Of this very universally useful, esculent species, there are many varieties cultivated in India. The plants are annually renewed from seed, though all the varieties are perennial; but like the Capsicums not so productive after the first year. They continue to blossom and bear fruit the whole year, but chiefly during the cold season. In Bengal, in a rich soil, they have very few prickles, but in a poor one many.

"Solanum longum. R.

Perennial.

[...]

Sans. Koolee.

Long Brinjal of Europeans.

I consider this to be a species clearly distinct from melongena, for the fruit is always cylindrical, never changing by culture into any other form. The plant is biennial, and in every respect like Melongena, the fruit excepted. I have only met with it in gardens, where it is cultivated for the table, and have had it nine years in mine without producing any change in it. The cold season is the proper time for rearing it.

The plants will exist several years, but are either dug up or neglected after the first."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 1, S. 566f.]

"Solanum melongena (Linn.) The Brinjal or Egg-plant [...]

Description.—Perennial; [...]

Fl. Nearly all the year.

The varieties are—

- Stem, leaves, and calyxes unarmed or nearly so. Solanum ovigerum, Dun. Rom. and Sch.—S. Melongena, Linn. Willd. Roxb. Fl. Ind. i. 566, Egg-plant [...] Tel. All over India. Fl. largish, violet.

- Stem, leaves, and calyxes more or less aculeate. Solanum esculentum, Dun. — S. Melongena, Linn, suppl.— S. insanum, Linn. Willd. (not Roxb.)—S. longum, Roxb. Fl. Ind. i. 567.—Neelavaloothana, Rheede, x. t. 74.—Long Brinjal. Fl. largish, bright bluish purple.

The fruit of each of these varieties is either ovate-oblong or oblong, violet or white; or globular (larger and smaller), violet; or more and less globular, white, or white-striped on a violet ground.

Economic Uses.—The Brinjal is universally cultivated in India as an esculent vegetable, belonging to an order of plants remarkable for their poisonous as well as harmless qualities. On this subject Dr Lindley has well remarked : "The leaves of all are narcotic and exciting, but in different degrees,—from the Atropa Belladonna, which causes vertigo, convulsions, and vomiting—the well-known Tobacco, which will frequently produce the first and last of these symptoms—the Henbane, and Stramonium, down to some of the Solanum tribe, the leaves of which are used as kitchen herbs. It is in the fruit that the greatest diversity of character exists. Atropa Belladonna, Solanum nigrum, and others, are highly dangerous poisons; Stramonium, Henbane, and Physalis are narcotic; the fruit of Physalis Alkekengi is diuretic, that of Capsicum is pungent, and even acrid; some species of Physalis are sub-acid, and so wholesome as to be eaten with impunity {e. g.} the well-known Tepariga) ; and finally, the Egg-plant (Solatium Melongena, Brinjal), and all the Tomato tribe of Solanum, yield fruits which are common articles of cookery. It is stated that the poisonous species derive their properties from the presence of a pulpy matter which surrounds the seeds; and that the wholesome kinds are destitute of this, the pulp consisting only of what botanists call the sarcocarp—that is to say, the centre of the rind, in a more or less succulent state. It must also be remembered that if the fruit of the Egg-plant is eatable, it only becomes so after undergoing a peculiar process, by which all its bitter acrid matter is removed, and that the Tomato is always exposed to heat before it is eaten.""

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

Apocynaceae (Hundsgiftgewächse)

| 2. c./d. nākulī surasā rāsnā sugandhā

gandhanākulī 3. a./b. nakuleṣṭā bhujaṃgākṣī chatrākī suvahā ca sā

नाकुली सुरसा रास्ना सुगन्धा गन्धनाकुली ॥२ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz 1877 - Java-Teufelspfeffer - Java Devil Pepper:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Rasan. Uncertain. See As. Res. vol. iv. p. 309."

1 Mungo:

Abb.: Herpestes edwardsii E.

Geoffroy, 1818 - Indian Gray Mongoose - Indischer Mungo, Hyderabad -

హైదరాబాద్, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia.

-- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Herpestes javanicus E.

Geoffroy, 1818 - Small Asian Mongoose - Kleiner Mungo, Hawaii, USA

[Bildquelle:

Carla

Kishinami. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kishlc/3480814568/. -- Zugriff am 2011-01-04.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine bearbeitung)]

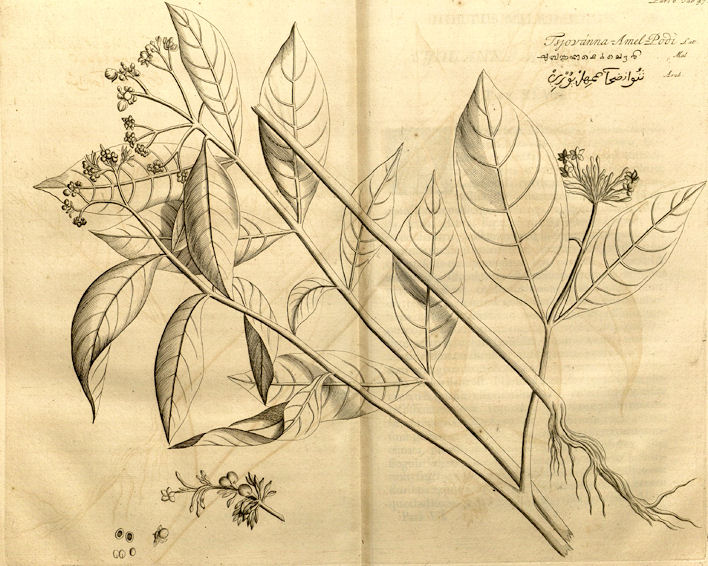

Abb.: Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex

Kurz 1877 - Java-Teufelspfeffer - Java Devil Pepper

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VI. Fig. 47, 1686]

Abb.: छत्राकी । Rauvolfia serpentina (L.)

Benth. ex Kurz 1877 - Java-Teufelspfeffer - Java Devil Pepper

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine, v. 20 (1804), Tab. 784]

Abb.: सुगन्धा ।

Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz 1877 - Java-Teufelspfeffer - Java

Devil Pepper, Mangalore -

ಮಂಗಳೂರು,

Karnataka

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/505526733/s. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-20. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: गन्धनाकुली ।

Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz 1877 - Java-Teufelspfeffer - Java

Devil Pepper, Karlsruhe, Deutschland

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: भुजंगाक्षी ।

Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz 1877 - Java-Teufelspfeffer - Java

Devil Pepper, Karlsruhe, Deutschland

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: सुरसा ।

Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz 1877 - Java-Teufelspfeffer - Java

Devil Pepper, Samen

[Bildquelle: Tracey Slotta @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

"Ophioxylon serpentinum. Willd. iv. 979.

Tsiovanna-Amel-Podi. Rheed. Mal. vi. 81. I. 47.

Radix Mustela. Rumph. Amb. vii. 29. t. 16.

Sans. Chundrika, Churmuhuntree, Pushoomehunukarika, Nundunee, Karuvee, Bhudra, Vasoopooshpa, Vasura, Chundrushoora.

[...]

This, in a rich soil, is a large climbing or twining shrub : in a poor soil, small and erect. It is a native of the Circar mountains. In my garden it flowers all the year round.

[...]

The root of this plant is employed for the cure of various disorders by the Telinga physicians. First, in substance, inwardly, as a febrifuge. Secondly, in the same manner, after the bite of poisonous animals. The juice is also expressed, and dropt into the eye, for the same purpose. And thirdly, it is administered, in substance, to promote delivery in tedious cases."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 1, S. 694f.]

"Ophioxylon serpentinum (Linn.) N. O. Apocynaceae.

[...]

Description. — Twining ; [...] flowers white, with the tube pale rose-lilac. Fl. All the year.

Roxb. Fl. Ind. i. 694.— Wight Icon. t. 849,—Rheede, vi. t 47.

Peninsula. Bengal. Malabar.

Medical Uses.—Few shrubs, says Sir W. Jones, in the world are more elegant, especially when the vivid carmine of the perianth is contrasted, not only with the milk-white corolla, but with the rich green berries, which at the same time embellish the fascicles. Rheede says it is always bearing, the berries and flowers appearing together at all times. The root is used internally in various disorders both as a febrifuge and for the bites of poisonous animals, such as snakes and scorpions, the dose being a pint of the decoction every twenty-four hours; the powder being also applied to the parts. The juice is also expressed and dropped into the eye for the same purpose. It is also administered to promote delivery in tedious cases, acting upon the uterine system in the same manner as ergot of rye.—Roxb. Wight."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"RAUWOLFIA SERPENTINA, Benth.

Fig.—Wight Ic. t. 849; Bot. Mag. t. 784 ; Burm. Fl. Zeyl. t. 64.

Syn. Ophioxylon serpentinum.

Hab.—Throughout India.

[...]

History, Uses, &c. This shrub is mentioned in Sanskrit works under the names of Sarpagandhi and Chandrika. The Hindus use the root as a febrifuge, and as an antidote to the bites of poisonous reptiles, also in dysentery and other painful affections of the intestinal canal. By some it is supposed to cause uterine contraction and promote the expulsion of the foetus. Ainslie gives the following account of it:—"Tsjovanna amelpodi is the name given, on the Malabar Coast (Rheede, Mai. vi. 81, t. 47), to a plant, the bitter root of which is supposed to have sovereign virtues in cases of snake-bites and scorpion-stings ; it is ordered in decoction, to the extent of a pint in twenty-four hours, and the powder is applied, externally, to the injured part. The plant is the Radix mustela of Rumphius. (Amb. vii. 29, t. 16.) The Javanese class it among their anthelmintics, and give it the name of pulipandak. It may be found noticed both by Burman in his Thesaur. Zeylan. (t. 64) and Garcia ab Horto; the latter recommends it as stomachic; Rumphius speaks of it as an antidote to poisons ; and Bontius, in his Hist. Mat. Med. Ind. tell us that it cures fever." (Mat. Ind. II. 441.) It will be seen that Ainslie confounds it with the Radix mustela or ichneumon root (Ophiorhiza Mungos), and the natives of some other parts of India Appear to make the same mistake. Sir W. Jones (Asiat. Research. iv., p. 308,) thinks it possible that this plant may perhaps be the true ichneumon plant. In the Pharmacopoeia of India its use in labours to increase uterine contractions is noticed upon the authority of Dr. Pulney Andy, but we have no other evidence of its efficacy in such cases. In Bombay most of the labourers who come from the Concan keep a small supply of the root, which they value as a remedy in painful affections of the bowels. In the Concan the root with Aristolochia indica (Sapsan) is given in cholera; in colic 1 part of the root with 2 parts of Holarrhena root and 3 parts of Jatropha Curcas root is given in milk; in fever the root with Andrographix paniculata, ginger and black salt is used. The dose of the combined drugs in each case is from 3 to 4 tola's."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 414f.]

Fabaceae (Hülsenfrüchtler)

| 3. c./d. vidārigandhāṃśumatī sālaparṇī

sthirā dhruvā विदारीगन्धांशुमती सालपर्णी स्थिरा ध्रुवा ॥३ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Desmodium gangeticum DC.:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Satparni. Hedysarum Gangeticum [Roxb. = Desmodium gangeticum DC.]"

1 sāla - Salbaum: Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.

Abb.: Altes Blatt von Shorea robusta Gaertn. f. - Salbaum,

Buxa Tiger Reserve -

বক্সা জাতীয় উদ্যান, West Bengal

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia.

-- GNU FDLicense]

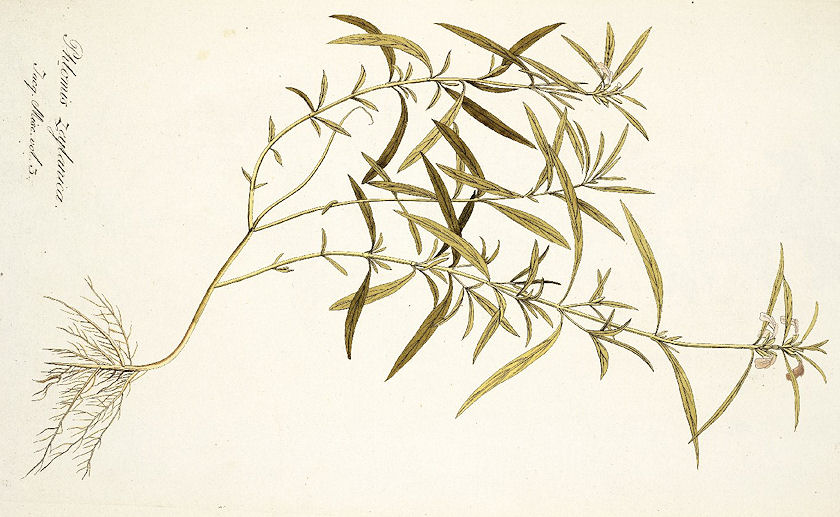

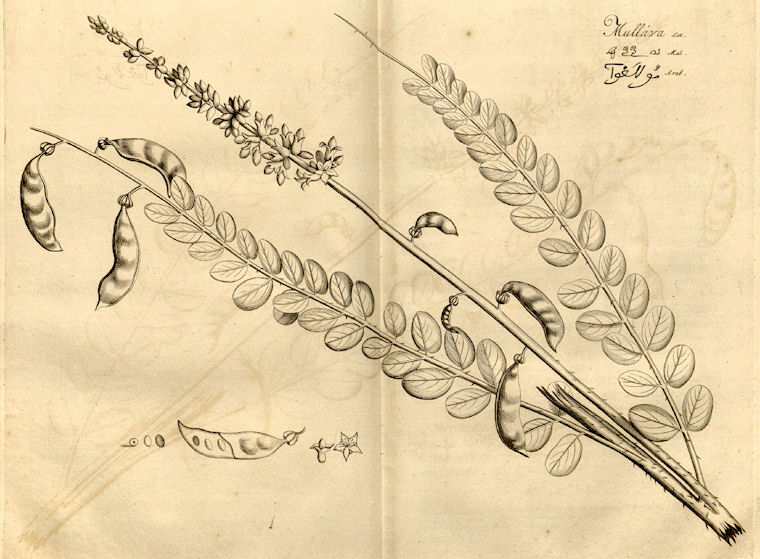

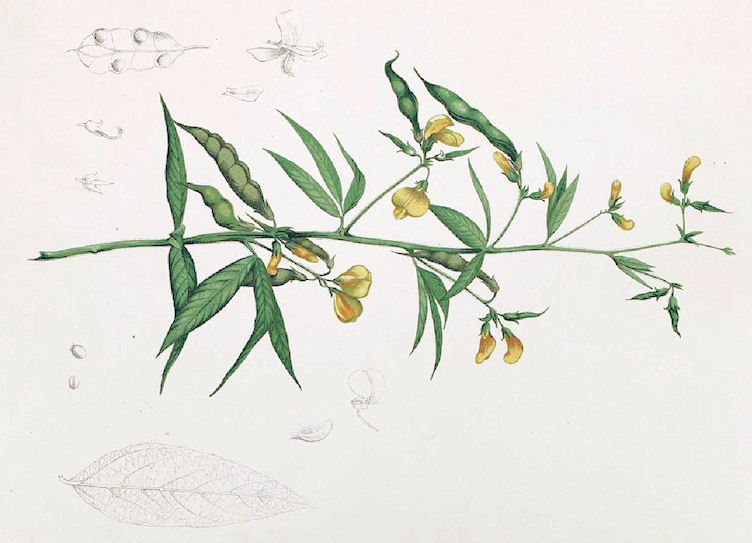

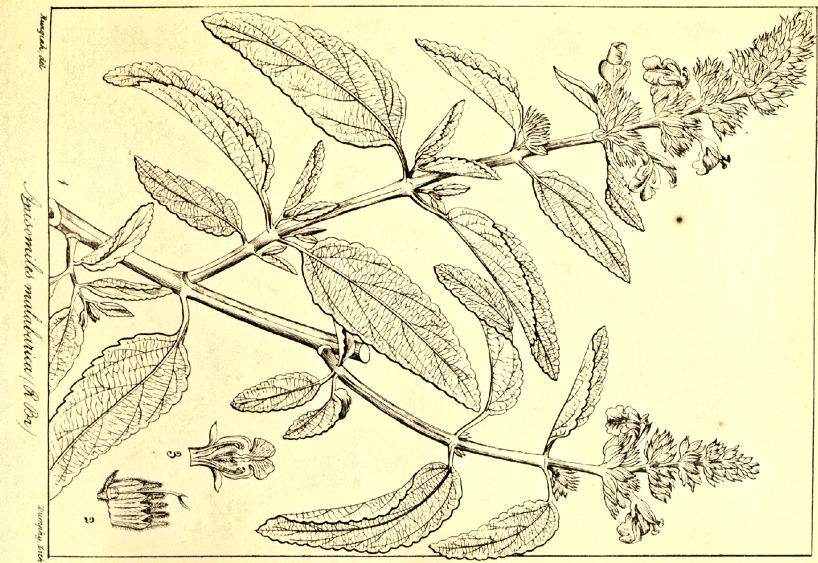

Abb.: Desmodium

gangeticum DC.

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas, 1880 / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Desmodium gangeticum DC, Tungareshwar

Wildlife Sanctuary, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/2891693549/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-20. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Desmodium

gangeticum DC., Ananthagiri Hills, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Desmodium

gangeticum DC., Ananthagiri Hills, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Desmodium

gangeticum DC., Ananthagiri Hills, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"DESMODIUM GANGETICUM, DC.

Fig.—Wight Ic. t. 271.

Hab.—The Himalayas to Pegu and Ceylon.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—This plant is of interest as being an ingredient of the Dasamula Kvatha so often mentioned in Sanskrit works; it is considered to be febrifuge and anti-catarrhal. In the Dasamula it is placed among the five minor plants (see Tribulus terrestris), a decoction of these is directed to be used in catarrhal fever, cough and other diseases supposed to be caused by deranged phlegm. The five major plants are prescribed in fever and other diseases supposed to be caused by deranged air. The ten together are used in remittent fever, puerperal fever, inflammatory affections within the chest, affections of the brain, and many other diseases supposed to be caused by derangement of all the humours. (For further information upon these points, consult Chakradatta.) The Sanskrit name is Shalaparni, "having leaves like the Shal" (Shorea robusta). In the Nighantas the root is described as alterative and tonic, and a remedy for vomiting, fever, asthma and dysentery."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 428.]

Malvaceae (Malvengewächse)

| 4. a./b. tuṇḍikerī samudrāntā kārpāsī

badareti ca तुण्डिकेरी समुद्रान्ता कर्पसी बदरेति च ।४ क। [Bezeichnungen für Gossypium arboreum L. 1753 - Baumförmige Baumwolle - Tree Cotton:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Cotton."

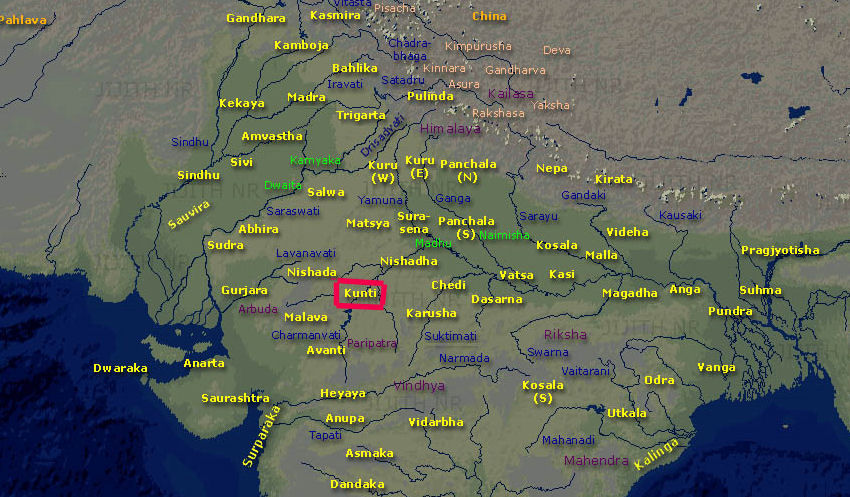

1 Tuṇḍikererin: Tuṇḍikera: ein Volksstamm (s. z.B. Mahābhārata VIII.4.47)

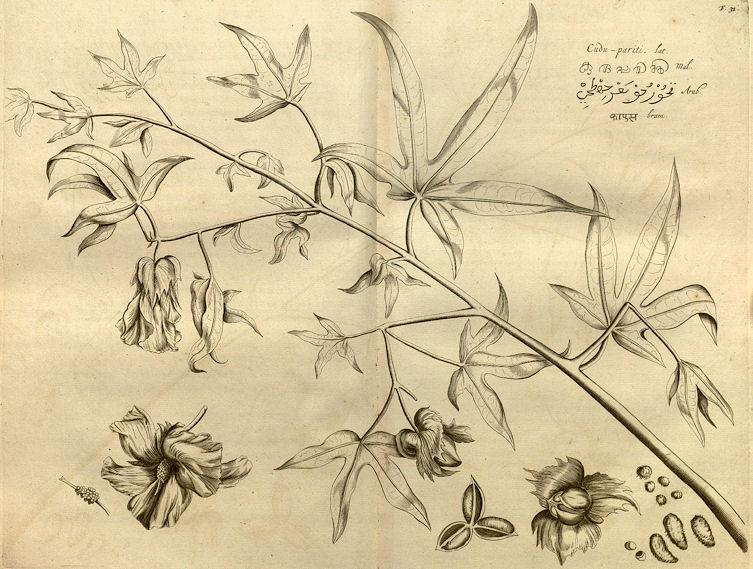

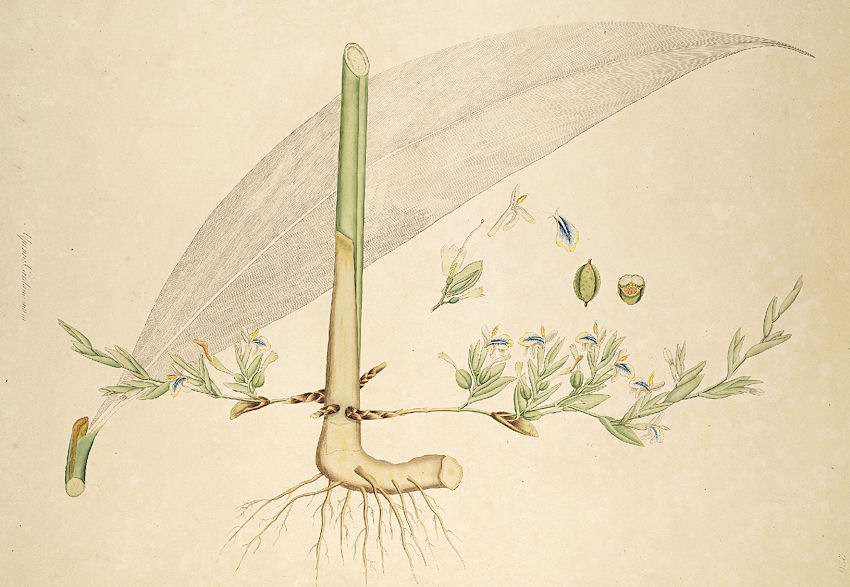

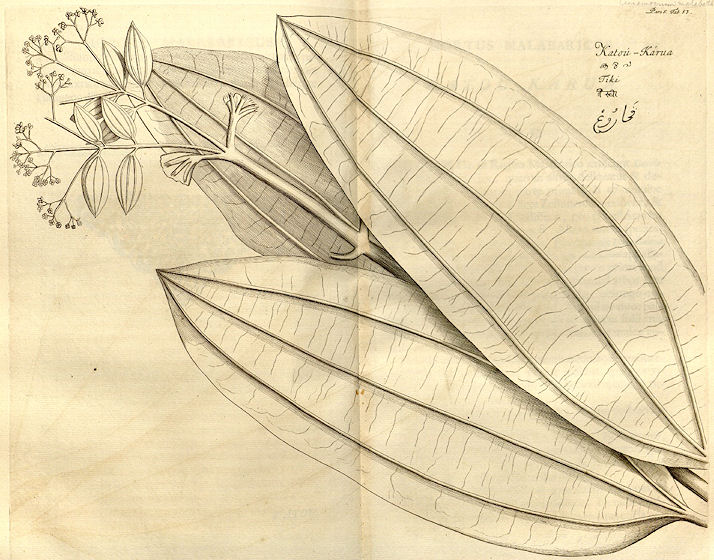

Abb.: कर्पसी । Gossypium arboreum L. 1753 - Baumförmige Baumwolle - Tree

Cotton

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus I. Fig. 31, 1678]

Abb.: Gossypium herbaceum L. 1753 und

Gossypium arboreum L. 1753 - Baumförmige Baumwolle - Tree Cotton

[Bildquelle: Royle, J. Forbes <1799-1858>: Illustrations of the botany and other

branches of the natural history of the Himalayan Mountains :and of the flora of

Cashmere. -- Vol 2: Plates. -- London : Allen, 1839. -- Pl. 23.]

Abb.:

कर्पसी । Gossypium arboreum L. 1753 - Baumförmige Baumwolle - Tree Cotton

[Bildquelle: KENPEI / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Samen von

Gossypium arboreum L. 1753 - Baumförmige Baumwolle - Tree Cotton

[Bildquelle: USDA / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

"Gossypium herbaceum. Willd. iii. 803.

Bi-triennial ; [...] Seeds free, clothed with firmly adhering, white down, under the long- white wool.

Gossypium. Capas. Rumph. Amb, iv. p. 33. t. 12.

Sans. Karpassee.

G. herhaceum. Cavan. Diss. vi. p. 310. t. 164. f. 2.

[...]

This and its varieties are by far the most universally cultivated by the natives of India. The most conspicuous of these varieties are the Dacca, Berar, and China cottons. Dacca Cotton may be reckoned the first variety, or deviation, from the last mentioned common sort.

G. herbaceum is in general cultivation all over Bengal and Coromandel.

It is reared about Dacca, and furnishes that exceedingly fine cotton wool employed in manufacturing the very delicate, beautiful muslins of that place. The Dacca variety differs from the common G. herbaceum in the following respects.

In the plant being more erect, with fewer branches, and the lobes of the leaves more pointed.

In the whole plant being tinged of a reddish colour, even the petioles, and nerves of the leaves, and being less pubescent.

In having the peduncles which support the flowers longer, and the exterior margins of the petals tinged with red.

In the staple of the cotton being longer, much finer, and softer.

These are the most obvious disagreements, but whether they will prove permanent I cannot say at present. The most intelligent people of that country (Dacca) think the great difference lies in the spinning, and allow little for the influence of soil.

Berar Cotton, I call the second variety. It is in cultivation over the Berar country ; and is from thence imported into the Circars, or Northern Provinces, by Sada, Balawansa, &c. to Yourma-goodum, in the Musulipfttam district. With this cotton the fine Madras, more properly, Northern Circar long cloth is made.

It differs from the above-mentioned two sorts in the following respects.

In growing to a greater size ; in being more permanent, or living longer; and in having smooth and straight branches.

In having the leaflets of the exterior calyx more deeply divided, and the wool of a finer quality, than in the first variety.

China Cotton, I call the third variety. It has lately been introduced into Bengal, from China; where it is cultivated, and its wool reckoned 25 per cent, better than that of Surat. It differs from the former sorts,

In being much smaller, with but very few, short, weak branches.

In being, so far as my experience yet goes, annual.

In having the leaflets of the exterior calyx entire, or nearly so.

Lamarck's G. Indicum, (Encyl. ii. p. 134,) is no doubt one of these varieties, and from him Willdenow has given it a place in his Ed. of the Sp. Pl. vol. iii. p. 803."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 1, S. 184ff.]

"Gossypium Indicum (Linn.) N. O. Malvaceae. Indian Cotton plant [...]

Description.--Herbaceous ; [...]

Royle.

G. herbaceum, Linn.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii 184.—Royle. Ill. Him. Bot. t. 23, fig. 1.

Cultivated.

Economic Uses. — As flax is characteristic of Egypt, and the hemp of Europe, so cotton may truly be designated as belonging to India. Long before history can furnish any authentic account of this invaluable product, its uses must have been known to the inhabitants of this country, and their wants supplied from time immemorial, by the growth of a fleecy-like substance, covering the seeds of a plant, raised more perhaps by the bounty of Providence than the labour of mankind.

In Sanscrit, cotton is called kurpas, from whence is derived the Latin name carbasus, mentioned occasionally in Roman authors. This word subsequently came to mean sails for ships and tents. Herodotus says, talking of the products of India,—" And certain wild trees bear wool instead of fruit, that in beauty and quality exceeds that of sheep: and the Indians make their clothing from these trees" (iii. 106). And in the book of Esther (i. 6) the word green corresponds to the Hebrew kurpas, and is in the Vulgate translated carbasinu8. The above shows from how early a period cotton was cultivated in this country. "The natives," says Royle (alluding to its manufacture in India), " of that country early attained excellence in the arts of spinning and weaving, employing only their Angers and the spinning-wheel for the former; but they seem to have exhausted their ingenuity when they invented the hand- loom for weaving, as they have for ages remained in a stationary condition."

It has sometimes been considered a subject of doubt whether the cotton was indigenous to America as well as Asia, but without sufficient reason, as it is mentioned by very early voyagers as forming the only clothing of the natives of Mexico; and, as stated by Humboldt, it is one of the plants whose cultivation among the Aztec tribes was as ancient as that of the Agave, the Maize, and the Quinoa (Chenopodium). If more evidence be required, it may be mentioned that Mr Brown has in his possession cotton not separated from the seeds, as well as cloth manufactured from it brought from the Peruvian tombs; and it may be added that the species now recognised as American differ in character from all known Indian species (Royle).

Cotton is not less valuable to the inhabitants of India than it is to European nations. It forms the clothing of the immense population of that country, besides being used by them in a thousand different ways for carpets, tents, screens, pillows, curtains, &c. The great demand for cotton in Europe has led of late years to the most important consideration of improvements in its cultivation. The labours and outlay which Government has expended in obtaining so important an object have happily been attended with the best results. The introduction of American seeds and experimental cultivation in various parts of India have been of the greatest benefit. They have been the means of producing a better article for the market, simplifying its mode of culture, and proving to the Ryots how, with a little care and attention, the article may be made to yield tenfold, and greatly increase its former value. To neither the soil nor the climate can the failure of Indian cotton be traced: the want of easy transit, however, from the interior to the coast, the ruinous effect of absurd fiscal regulations, and other influences, were at work to account for its failure. In 1834, Professor Boyle drew attention to two circumstances : " I have no doubt that by the importation of foreign, and the selection of native seed—attention to the peculiarities not only of soil but also of climate, as regards the course of the seasons, and the temperature, dryness, and moisture of the atmosphere, as well as attention to the mode of cultivation, such as preparing the soil, sowing in lines so as to facilitate the circulation of air, weeding, ascertaining whether the mixture of other crops with the cotton be injurious or otherwise, pruning, picking the cotton as it ripens, and keeping it clean—great improvement must take place in the quality of the cotton. Experiments may at first be more expensive than the ordinary culture; the natives of India, when taught by example, would adopt the improved processes as regularly and as easily as the other; and as labour is nowhere cheaper, any extra outlay would be repaid fully as profitably as in countries where the best cottons are at present produced."

The experiments urged by so distinguished an authority were put in force in many parts of the country, and notwithstanding the great prejudice which existed to the introduction of novelty and other obstacles, the results have proved eminently successful. It has been urged that Indian cotton is valuable for qualities of its own, and especially that of wearing well. It is used for the same purposes as hemp and flax, hair and wool, are in England. There are, of course, a great many varieties in the market, whose value depends on the length, strength, and fineness as well as softness of the material, the chief distinction being the long stapled and the short stapled. Cotton was first imported into England from India in 1783, when about 114,133 lb. were received. In 1846, it has been calculated that the consumption of cotton for the last 30 years has increased at the compound ratio of 6 per cent, thereby doubling itself every twelve years. The chief parts of India where the cotton plant is cultivated are in Guzerat, especially in Surat and Broach, the principal cotton districts in the country; the southern Mahratta countries, including Dharwar, which is about a hundred miles from the seaport; the Concans, Canara, and Malabar. There has never been any great quantity exported from the Madras side, though it is cultivated in the Salem, Coimbatore, and Tinnevelly districts, having the port of Tuticorin on one coast, and of late years that of Cochin on the other, both increasing in importance as places of export In the Bengal Presidency, Behar and Benares, and the Saugor and Nerbudda territories, are the districts where it is chiefly cultivated.

The present species and its varieties are by far the most generally cultivated in India. Dacca cotton is a variety chiefly found in Bengal, furnishing that exceedingly fine cotton, and employed in manufacturing the very delicate and beautiful muslins of that place, the chief difference being in the mode of spinning, not in any inherent virtue in the cotton or soil where it grows. The Berar cotton is another variety with which the N. Circar long-cloth is made. This district, since it has come under British rule, promises to be one of the most fertile and valuable cotton districts in the whole country.

Much diversity of opinion exists as to the best soil and climate adapted for the growth of the cotton plant; and considering that it grows at altitudes of 9000 feet, where Humboldt found it in the Andes, as well as at the level of the sea, in rich black soil and also on the sandy tracts of the sea-shore, it is superfluous to attempt specifying the particular amount of dryness or moisture absolutely requisite to insure perfection in the crop. It seems to be a favourite idea, however, that the neighbourhood of the sea-coast and islands are more favourable for the cultivation of the plant than places far inland, where the saline moisture of the sea-air cannot reach. But such is certainly not the case in Mexico and parts of Brazil, where the best districts for cotton-growing are far inland, removed from the influence of sea-air. Perhaps the different species of the plant may require different climates. However that may be, it is certain that they are found growing in every diversity of climate and soil, even on the Indian continent; while it is well known that the best and largest crops have invariably been obtained from island plantations, or those in the vicinity of the sea on the mainland.

A fine sort of cotton is grown in the eastern districts of Bengal for the most delicate manufactures; and a coarse kind is gathered in every part of the province from plants thinly interspersed in fields of pulse or grain. Captain Jenkins describes the cotton in Cachar as gathered from the Jaum cultivation : this consists in the jungle being burnt down after periods of from four to six years, the ground roughly hoed, and the seeds sown without further culture. Dr Buchanan Hamilton, in his statistical account of Dinagepore, gives a full account of the mode of cultivation in that district, where he says some cotton of bad quality is grown along with turmeric, and some by itself, which is sown in the beginning of May, and the produce collected from the middle of August to the middle of October, but the cultivation is miserable. A much better method, however, he adds, is practised in the south-east parts of the district, the cotton of which is finer than that imported from the west of India: The land is of the first quality, and the cotton is made to succeed rice, which is cut between August and the middle of September. The field is immediately ploughed until well broken, for which purpose it may require six double ploughings. After one-half of these has been given, it is manured with dung, or mud from ditches. Between the middle of October and the same time in November, the seed is sown broadcast; twenty measures of cotton and one of mustard. That of the cotton, before it is sown, is put into water for one-third of an hour, after which it is rubbed with a little dry earth to facilitate the sowing. About the beginning of February the mustard is ripe, when it is plucked and the field weeded. Between the 12th of April and 12th of June the cotton is collected as it ripens. The produce of a single acre is about 300 lb. of cotton, worth ten rupees; and as much mustard-seed, worth three rupees. A still greater quantity of cotton, - Dr Hamilton continues, is reared on stiff clay-land, where the ground is also high and tanks numerous. If the soil is rich it gives a summer crop of rice in the same year, or at least produces the seedling rice that is to be transplanted. In the beginning of October the field is ploughed, and in the end of the month the cotton-seed is sown, mingled with Sorisha or Lara (species of Sinapis and Eruca); and some rows of flax and safflower are generally intermixed. About the end of January, or later, the oil-seeds are plucked, the field is hoed and manured with cow-dung and ashes, mud from tanks, and oil-cake; it is then watered once in from eight to twelve days. The cotton is gathered between the middle of April and the middle of June, and its produce may be from 360 to 500 lb. an acre.

In the most northern provinces of India the greatest care is bestowed on the cultivation. The seasons for sowing are about the middle of March and April, after the winter crops have been gathered in, and again about the commencement of the rainy season. The crops are commenced being gathered about the conclusion of the rains, and during October and November, after which the cold becomes considerable, and the rains again severe. About the beginning of February the cotton plants shoot forth new leaves, produce fresh flowers, and a second crop of cotton is produced, which is gathered during March and beginning of April. The same occurs with the cottons of Central India, one crop being collected after the rains and the other in February, and what is late in the beginning of March.

I venture to insert here the following interesting particulars about cotton manufacture : " The shrub Perutti, which produces the finer kind of cotton, requires in India little cultivation or care. When the cotton has been gathered it is thrown upon a floor and threshed, in order that it may be separated from the black seeds and husks which serve it as a covering. It is then put into bags or tied up in bales containing from 300 to 320 lb. of 16 oz. each. After it has been carded it is spun out into such delicate threads that a piece of cotton cloth 20 yards in length may almost be concealed in the hollows of both hands. Most of these pieces of cloth are twice washed; others remain as they come from the loom, and are dipped in cocoa-nut oil in order that they may be longer preserved. It is customary also to draw them through conjee or rice-water, that they may acquire more smoothness and body. This conjee is sometimes applied to cotton articles in so ingenious a manner that purchasers are often deceived, and imagine the cloth to be much stronger than it really is; for as soon as washed the conjee vanishes, and the cloth appears quite slight and thin.

"There are reckoned to be no less than 22 different kinds of cotton articles manufactured in India, without including muslin or coloured stuffs. The latter are not, as in Europe, printed by means of wooden blocks, but painted with a brush made of coir, which approaches near to horse-hair, becomes very elastic, and can be formed into any shape the painter chooses. The colours employed are indigo (Indigofera tinctoria), the stem and leaves of which plant yield that beautiful dark blue with which the Indian chintzes, coverlets, and other articles are painted, and which never loses the smallest shade of its beauty. Also curcuma or Indian saffron, a plant which dyes yellow; and lastly, gum-lac, together with some flowers, roots, and fruits which are used to dye red. With these few pigments, which are applied sometimes singly, sometimes mixed, the natives produce on their cotton cloths that admirable and beautiful painting which exceeds anything of the kind exhibited in Europe.

" No person in Turkey, Persia, or Europe has yet imitated the Betilla, a certain kind of white East Indian chintz made at Masulipatam, and known under the name of Organdi. The manufacture of this cloth, which was known in the time of Job, the painting of it, and the preparation of the colours, give employment in India to male and female, young and old. A great deal of cotton is brought from Arabia and Persia and mixed with that of India."—Bart. Voy. to East Indies.

The remaining uses of this valuable plant must now claim our attention. The seeds are bruised for their oil, which is very pure, and is largely manufactured at Marseilles from seeds brought from Egypt. These seeds are given as a fattening food to cattle. Cottonseed cake is imported from the West Indies into England, being used as a valuable food for cattle. The produce of oil-cake and oil from cotton-seeds is, 2 gallons of oil to 1 cwt. of seeds, and 96 lb. of cake. A great quantity is shipped from China, chiefly from Shanghai, for the English market. It forms an invaluable manure for the farmer.—Royle on Cotton Cultivation. Simmonds. Lindley. Roxb."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"GOSSYPIUM STOCKSII, Mast., var.herbaceum, Linn.

Fig.—Wight Ic, t. 9,11 ; Royle Ill. t. 23.

Cotton plant

Hab.--Sindh. Cultivated in most hot coutries.

[...]

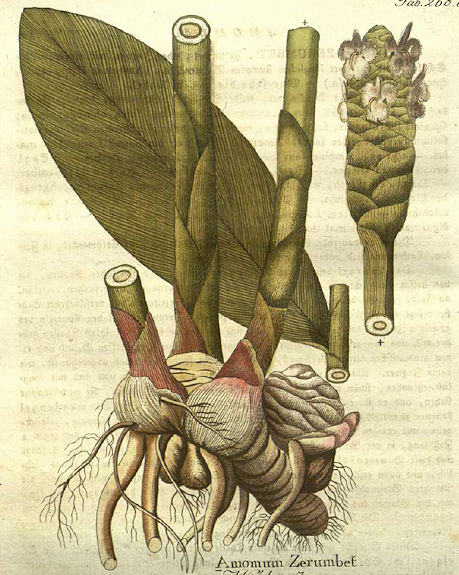

History, Uses, &c.—Cotton, the Karpasi of Sanskrit writers, was doubtless first known and made use of by the Hindus; it is the βυσσος of the later Greek writers, such as Philostratus and Pausanias, but not of the earlier Greeks, who applied this term to a fine kind of flax used for making mummy cloths. Theophrastus calls it Eriophora, Pliny Gossympinus, Gossypion, and Xylinum. In Arabic cotton is kuttun and kurfuss, the latter term being evidently derived from the Sanskrit. Eastern physicians consider all parts of the cotton plant to be hot and moist; a syrup of the flowers is prescribed in hypochondriasis on account of its stimulating and exhilarant effect; a poultice of them is applied to burns and scalds. Cotton cloth or mixed fabrics of cotton with wool or silk are recommended as the most healthy for wear. Burnt cotton is applied to sores and wounds to promote healthy granulation ; dropsical or paralysed limbs are wrapped in cotton after the application of a ginger or zedoary lep (plaster); pounded cotton seed, mixed with ginger and water, is applied in orchitis. Cotton is also used as a moxa, and the seeds as a laxative, expectorant, and aphrodisiac. -The juice of the leaves is considered a good remedy in dysentery, and the leaves with oil are applied as a plaster to gouty joints ; a hip bath of the young leaves and roots is recommended in uterine colic. In the Concan the root of the Deokapas (fairy or sacred cotton bush) rubbed to a paste with the juice of patchouli leaves, has a reputation as a promoter of granulation in wounds, and the juice of the leaves made into a Paste with the seeds of Vernonia anthelmintica is applied to eruptions of the skin following fever. In Pudukota the leaves ground and mixed with milk are given for strangury.

Cotton root bark is official in the United States Pharmacopoeia, also a fluid extract of the bark ; it appears to have first attracted attention from being used by the female negroes to produce abortion. There appears to be little doubt that it acts like ergot upon the uterus, and is useful in dysmenorrhea and suppression of the menses when produced by cold; a decoction of 4 ounces of the bark in two pints of water boiled down to one pint may be used in doses of two ounces every 20 or 30 minutes, or the fluid extract may be prescribed in doses of from 30 to 60 minims. Cotton seed tea is given in dysentery in America; the seeds are also reputed to be galactagogue. (Stillé and Maisch., Nat. Disp., p. 678.) By treating cotton first with a dilute alkali, then with a 5 per cent, solution of chloride of lime, and lastly with water acidulated with hydrochloric acid, and afterwards well washing it with water, it loses its greasiness and becomes absorbent and a valuable dressing for wounds; this absorbent cotton may be medicated by sprinkling it with solutions of carbolic acid, salicylic acid, boracic acid, &c. Pyroxylin or Gun Cotton is made by dipping cotton into a mixture of equal parts of nitric and sulphuric acids, washing freely with water, and drying."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 224ff.]

Malvaceae (Malvengewächse)

| 4. c./d. bhāradvājī tu sā vanyā

śṛṅgī tu ṛṣabho vṛśaḥ भारद्वजी तु सा वन्या शृङ्गी तु ऋषभो वृशः ॥४ ख॥ Die Waldform davon [Baumförmiger Baumwolle] heißt भारद्वजी - bhāradvajī f.: von Bharadvāja1 Stammende, zu Bharadvāja Gehörige, Bharadvāja-Pflanze |

Colebrooke (1807): "Wild cotton. In Bengal, Hibiscus vitifolius [L. 1753 = Fioria vitifolia (L.) Mattei 1916] is called wild cotton, वनकार्पसः"

1 Bharadvāja

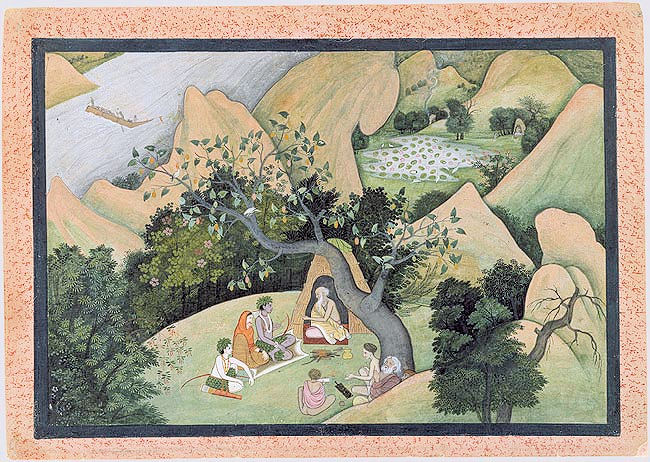

Abb.: Rāma, Sīta und Lakṣmaṇa bei Bharadvāja, Kangra - काँगड़ा,

Himachal Pradesh, ca. 1780

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

"BHARADVĀJA. A Ṛṣi to whom many Vedic hymns are attributed. He was the son of Bṛhaspati and father of Droṇa, the preceptor of the Pāṇḍavas. The Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa says that "he lived through three lives" (probably meaning a life of great length), and that "he became immortal and ascended to the heavenly world, to union with the sun." In the Mahābhārata he is represented as living at Hardwār ; in the Rāmāyaṇa he received Rāma and Sītā in his hermitage at Prayāga, which was then and afterwards much celebrated. According to some of the Purāṇas and the Hari-vaṃśa, he became by gift or adoption the son of King Bharata, and an absurd story is told about his birth to account for his name : His mother, the wife of Utathya, was pregnant by her husband and by Bṛhaspati. Dīrgha-tamas, the son by her husband, kicked his half-brother out of the womb before his time, when Bṛhaspati said to his mother, Bhara-dvā-jam, Cherish this child of two fathers.

BHĀRADVĀJA. 1. Droṇa. 2. Any descendant of Bharadvāja or follower of his teaching. 3. Name of a grammarian and author of Sūtras."

[Quelle: Dowson, John <1820-1881>: A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history, and literature. -- London, Trübner, 1879. -- s.v. ]

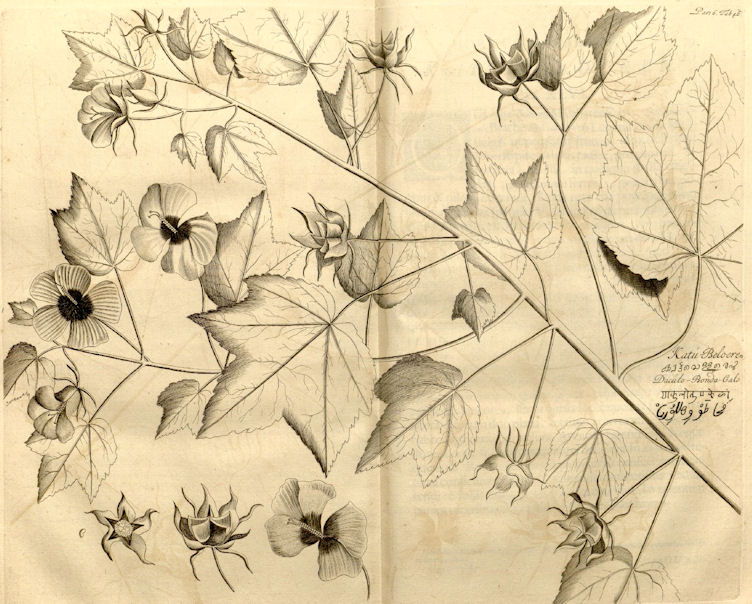

Abb.: भारद्वजी ।

Fioria vitifolia

(L.) Mattei 1916

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VI. Fig. 46, 1686]

Abb.: भारद्वजी ।

Fioria vitifolia

(L.) Mattei 1916, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1843262323/. -- Zugriff am

2010-11-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: भारद्वजी ।

Fioria vitifolia

(L.) Mattei 1916, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1843245075/. -- Zugriff am

2010-11-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

"Hibiscus vitifolius. Willd. iii. 829.

Annual, or biennial, bushy and villous. [...]

Bharadwaja, the Sanscrit name.

Katu beloeren. Rheed. Mal. vi. t. 46.

A native of rubbish, gardens, &c. all over India ; in flower during the rainy and cold seasons."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 200.]

| 4. c./d.

bhāradvājī tu sā vanyā śṛṅgī tu

vṛṣabho vṛśaḥ भारद्वजी तु सा वन्या शृङ्गी तु वृषभो वृषः ॥४ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Withania somnifera (Linn.) Dunal 1852 ???:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Rishabha. A medicinal drug."

Alles sind Bezeichnungen für Stier. Als Vṛṣa kennt die Pharmacographia indica nur Withania somnifera (Linn.) Dunal 1852, eine Solanacea (Nachtschattengewächs), die aber üblicherweise aśvagandhā heißt.

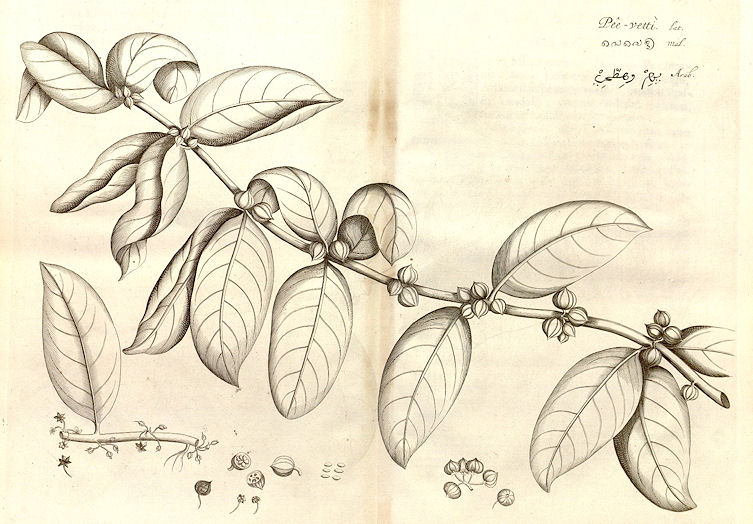

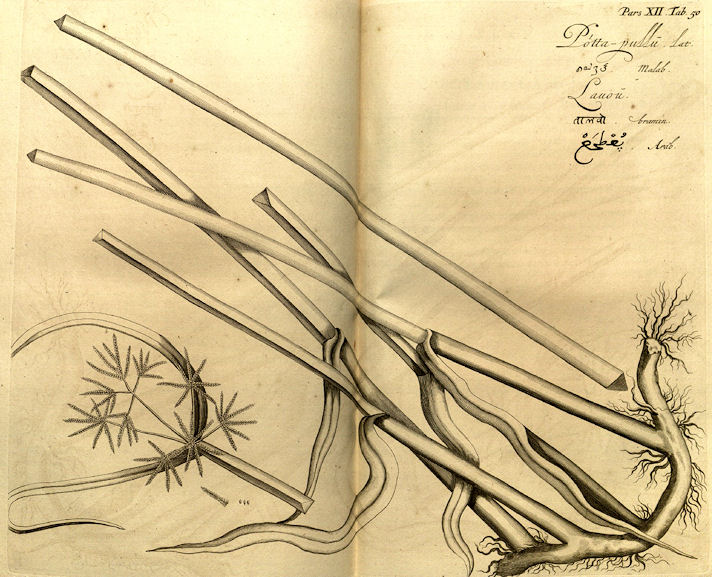

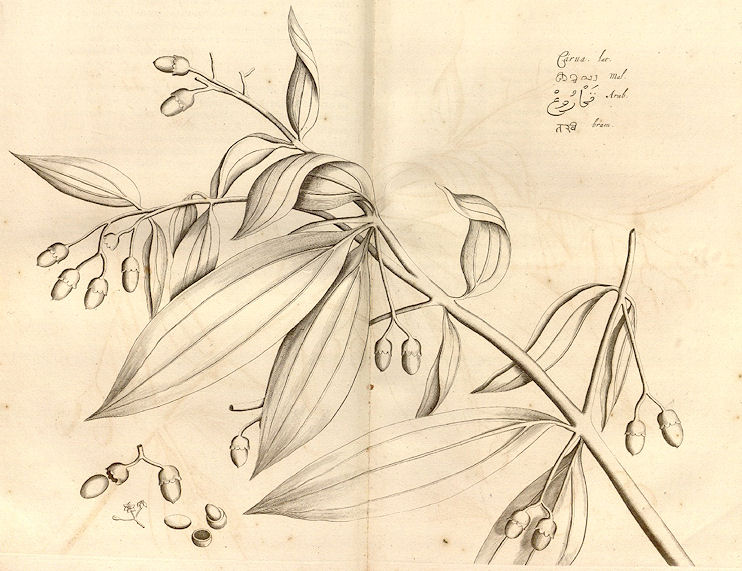

Abb.: Withania

somnifera (Linn.) Dunal 1852

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus IV. Fig. 55, 1683]

Abb.: Withania

somnifera (Linn.) Dunal 1852

[Bildquelle: Wight Icones III, Tab. 853, 1846]

Abb.: Withania

somnifera (Linn.) Dunal 1852

[Bildquelle: Satheesan.vn / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Withania somnifera (Dunal.) Winter Cherry

Description.—Perennial, 2-3 feet; [...]

Fl. Nearly all the year.— Wight Icon, t. 853.

Physalis flexuosa, Linn.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. i. 561.— Rheede, iv. t. 55.

Coromandel. Concans. Travancore. Bengal

Medical Uses. — The root is said to have deobstruent and diuretic properties. The leaves moistened with warm castor-oil are useful, externally applied in cases of carbuncle. They are very- bitter, and are given in infusion in fevers. The seeds are employed in the coagulation of milk in making butter. The fruit is diuretic. The root and leaves are powerfully narcotic, and the latter is applied to inflamed tumours, and the former in obstinate ulcers and rheumatic swellings of the joints, being mixed with dried ginger and so applied. The Telinga physicians reckon the roots alexipharmic.— Roxb. Ainslie."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"WITHANIA SOMNIFERA, Dunal.

Fig.—Jacq. Ecl. tt. 22,23 ; Sibth, Fl. Graec, t. 233 ; Wight I., t. 853; Bheede, Hod. Mai. iv., t. 55.

Hab.—Dry sub-tropical India, West Coast. Southern Europe.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—This plant bears the Sanskrit names of Asvagandha, Turagi or Turangi, and Turagi-gandha, "smelling like a horse or mare"; Varāha-karni, "boar-eared"; Vrisha, "amorous," &c. It is described in the Nighantas as tonic, alterative, pungent, astringent, hot and aphrodisiac, and is recommended in rheumatism, cough, dropsy, consumption and senile debility. Chakradatta recommends it in decoction with long pepper, butter and honey in consumption and scrofula. A ghrita or medicinal butter prepared by boiling together one part of the root with one part of clarified butter and ten of milk may be used in such cases. As an aphrodisiac and as a remedy for rheumatism the drug is usually combined with a number of aromatics, each dose contains about 30 grains of the root. It is also made into a paste with aromatics for local application in rheumatism. Indian Mahometan writers merely repeat what the Hindus say about this drug, and do not recognise in it the Kaknaj-el-manoum of the Arabs, which is supposed to represent the

στρυχνος υπνοτικοσ of the Greeks, the description of which by Theophrastus agrees tolerably well with W. somnifera. Rheede calls it Pevetti, and states that a vulnerary ointment is prepared from the leaves. Prosper Alpinus (i., cap. 33) describes and figures it under the name of Solanum somniferum antiquorum. Roxburgh states that the Telinga physicians reckon the roots alexipharmic. Ainslie (ii. 14) says:—"The root as found in the medicine bazars, is of a pale colour, and in external appearance not unlike our gentian ; but it has little sensible taste or smell, though the Tamool Vytians suppose it to have deobstruent and diuretic qualities, given in decoction to the quantity of about half a teacupful twice daily ; the leaves moistened with a little warm castor oil, are a useful external application in cases of carbuncle." The authors of the Bombay Flora say that the seeds are employed to coagulate milk like those of W. coagulans. We have tried the experiment and find them to have some coagulating power.The plant is very common along the shores of the Mediterranean, where it has always been reputed to be hypnotic. The properties of W. somnifera have recently been investigated by Br. Trebut with regard to its reputation for hypnotic properties ; he states that he has obtained an alkaloid from it which has hypnotic action and does not produce mydriasis. P. L. Simmonds (Amer. Journ. Pharm., Feb., 1891) states that the plant is employed at the Civil Hospital, Alger, as a sedative and hypnotic."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 566ff.]

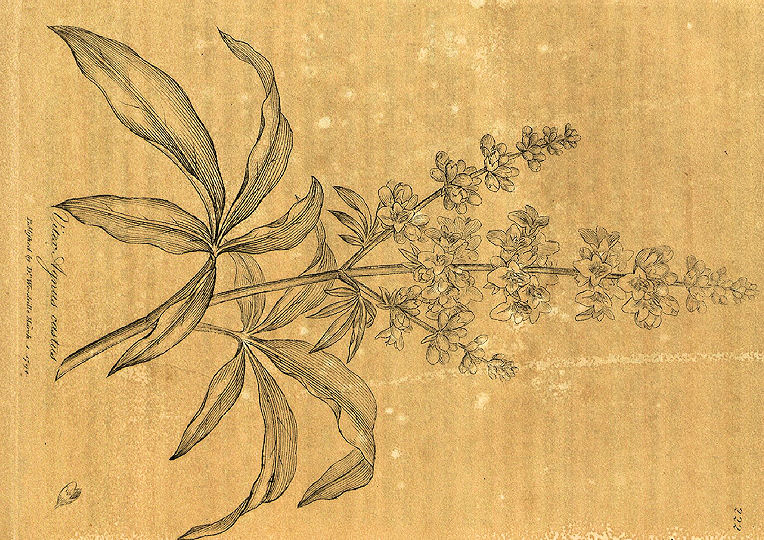

Tiliaceae (Lindengewächse)

| 5. a./b. gāṅgerukī nāgabalā jhaṣā

hrasvagavedhukā गाङ्गेरुकी नागबला झषा ह्रस्वगवेधुका ।५ क। [Bezeichnungen für Grewia hirsuta Vahl. 1790:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Gorakha. Uncertain ; many different plants being shown under this name."

1 gavedhukā f.: Coix lachryma-jobi Linn. - Hiobsträne - Job's Tears

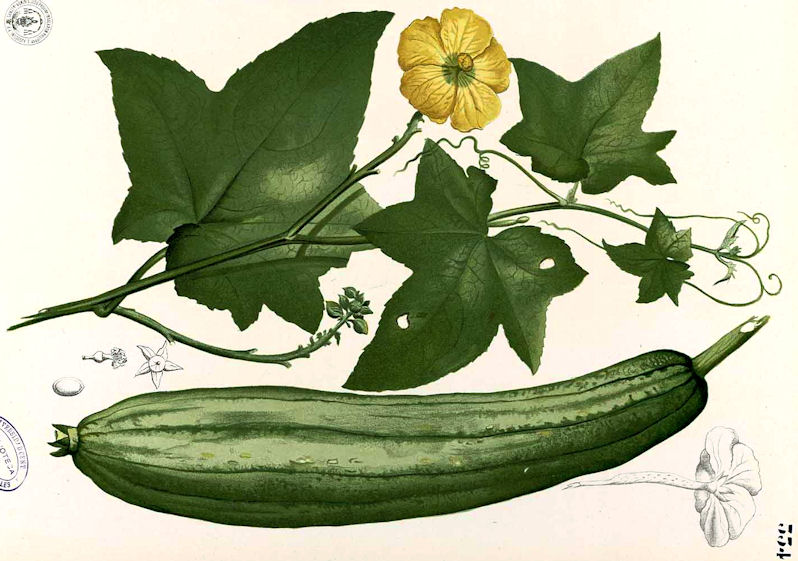

Abb.: गवेधुका । Coix lachryma-jobi Linn. - Hiobsträne -

Job's Tears

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas, 1880

/ Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

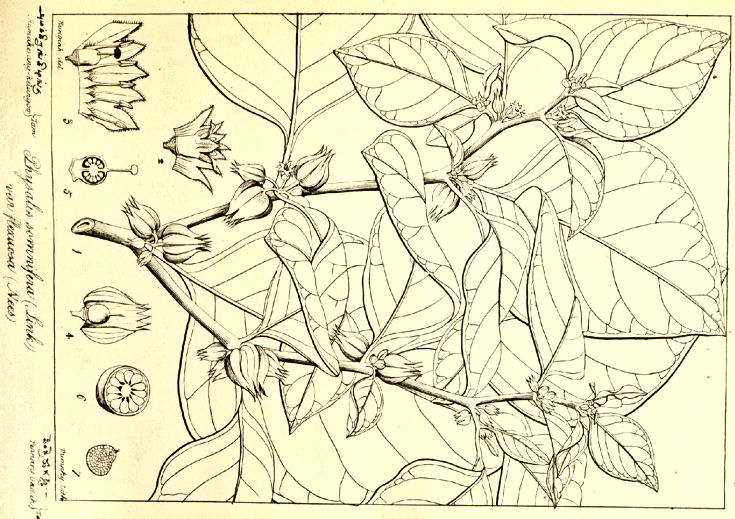

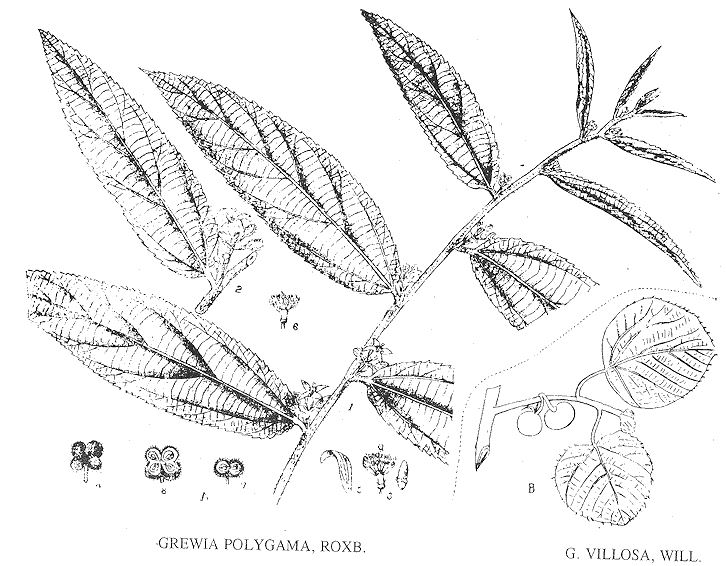

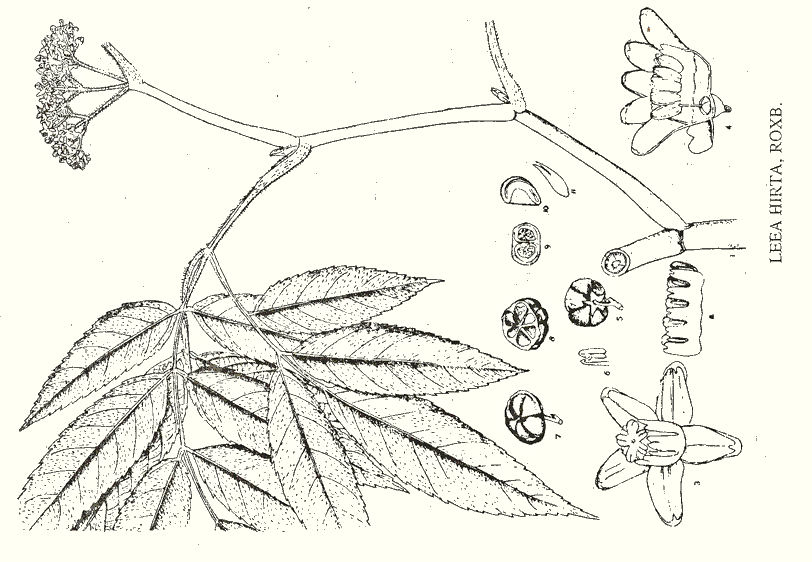

Abb.: Grewia hirsuta Vahl. 1790 (= Grewia

polygama Roxb.)

[Bildquelle: Kirtikar-Basu, ©1918]

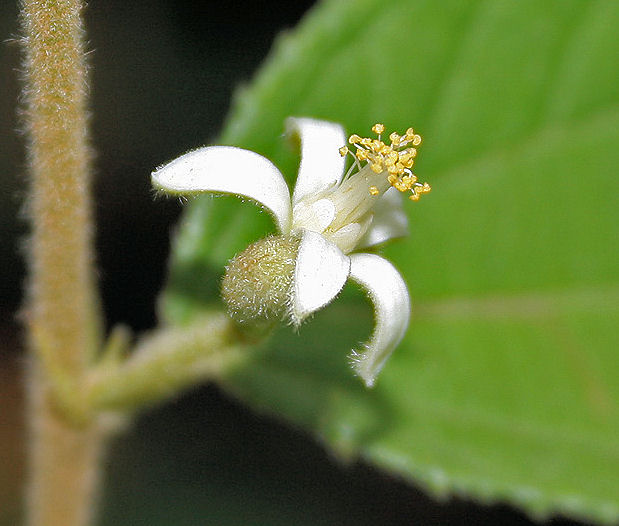

Abb.: Grewia

hirsuta Vahl. 1790, Talakona (తలకోన) Forest, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Grewia

hirsuta Vahl. 1790, Talakona (తలకోన) Forest, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Grewia hirsuta. Vahl. symb. 1. 34. Willd. 2. 1166.

Shrubby. [...]

A large shrub, a native of Coromandel; it blossoms during the hot and rainy season, and the fruit, which is very generally eaten by the natives, ripens in three or four months."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 2, S. 587.]

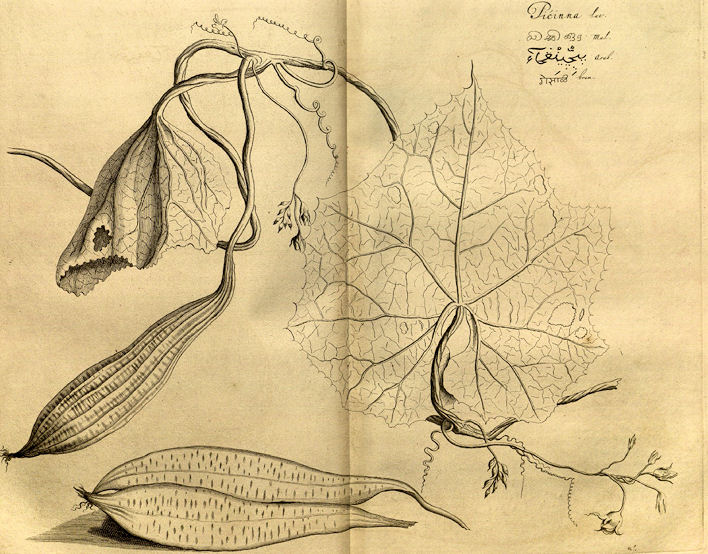

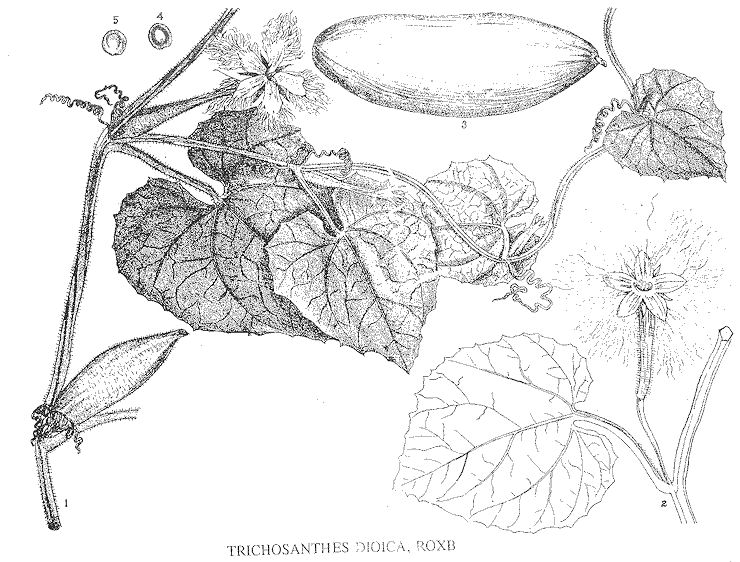

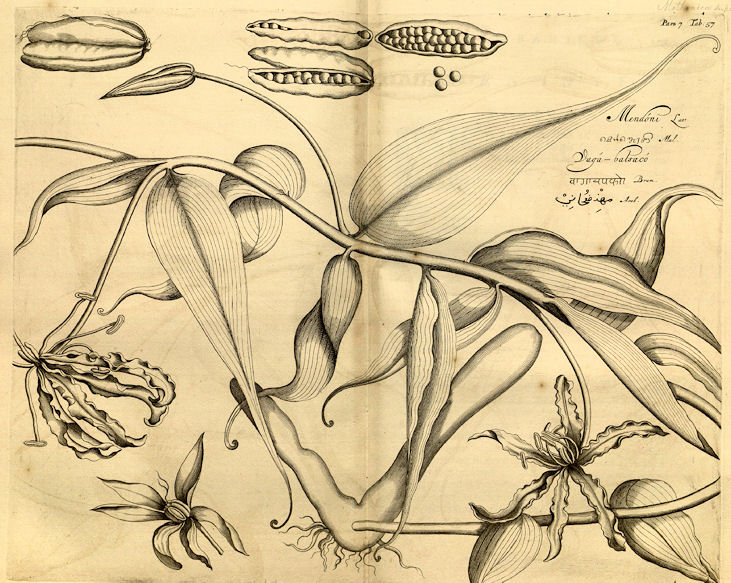

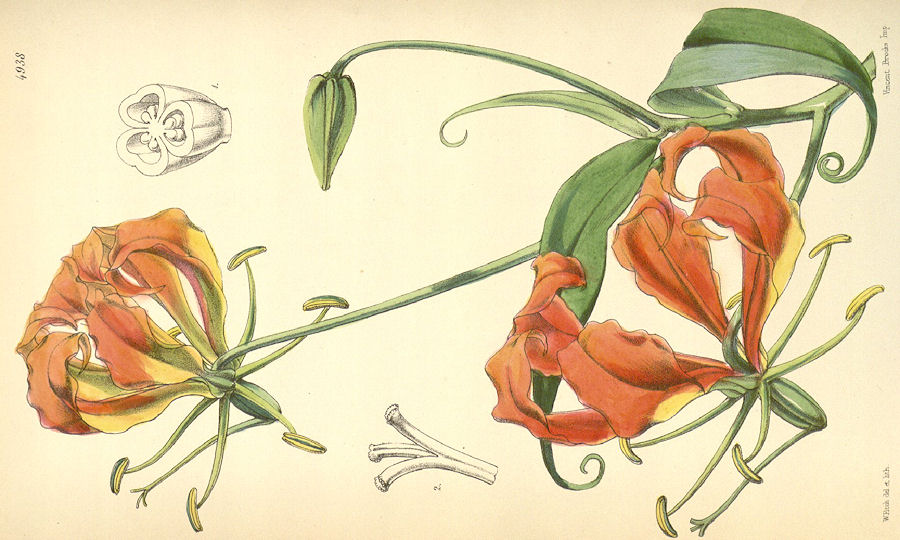

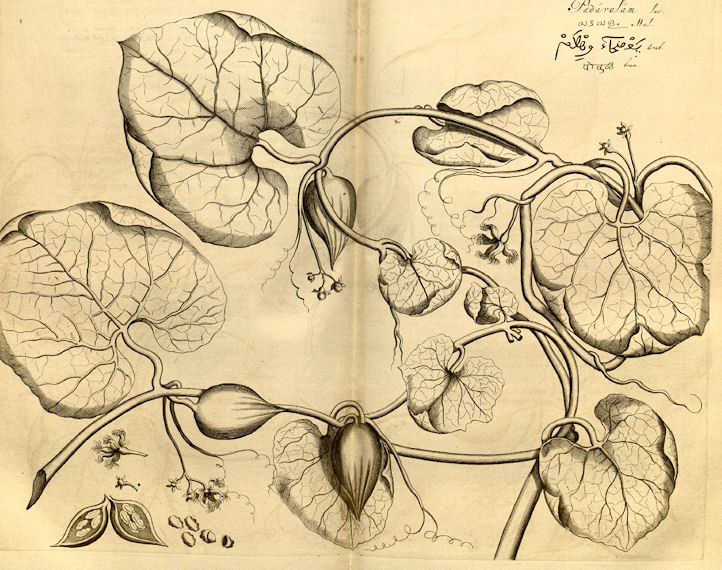

Cucurbitaceae (Kürbisgewächse)