|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

नामलिङ्गानुशासनम्

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 8. vanauṣadhivargaḥ V. -- 2. Vers 19 - 35. -- Fassung vom 2011-01-15. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa/amara208b.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-01-15

Überarbeitungen:

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

"Those who have never considered the subject are little aware how much the appearance and habit of a plant become altered by the influence of its position. It requires much observation to speak authoritatively on the distinction in point of stature between many trees and shrubs. Shrubs in the low country, small and stunted in growth, become handsome and goodly trees on higher lands, and to an inexperienced eye they appear to be different plants. The Jatropha curcas grows to a tree some 15 or 20 feet on the Neilgherries, while the Datura alba is three or four times the size in>n the hills that it is on the plains. It is therefore with much diffidence that I have occasionally presumed to insert the height of a tree or shrub. The same remark may be applied to flowers and the flowering seasons, especially the latter. I have seen the Lagerstroemia Reginae, whose proper time of flowering is March and April, previous to the commencement of the rains, in blossom more or less all the year in gardens in Travancore. I have endeavoured to give the real or natural flowering seasons, in contradistinction to the chance ones, but, I am afraid, with little success; and it should be recollected that to aim at precision in such a part of the description of plants is almost hopeless, without that prolonged study of their local habits for which a lifetime would scarcely suffice."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- S. VIII f.]

Bei der Identifikation der lateinischen Pflanzennamen folge ich, wenn immer es möglich ist:

Bhāvamiśra <16. Jhdt.>: Bhāvaprakāśa of Bhāvamiśra : (text, English translation, notes, appendences and index) / translated by K. R. (Kalale Rangaswamaiah) Srikantha Murthy. -- Chowkhamba Varanasi : Krishnadas Academy, 1998 - 2000. -- (Krishnadas ayurveda series ; 45). -- 2 Bde. -- Enthält in Bd. 1 das SEHR nützliche Lexikon (nigaṇṭhu) Bhāvamiśras.

Pandey, Gyanendra: Dravyaguṇa vijñāna : materia medica-vegetable drugs : English-Sanskrit. -- 3. ed. -- Varanasi : Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy, 2005. -- 3 Bde. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN: 81-218-0088-9 (set)

Wo möglich, erfolgt die aktuelle Benennung von Pflanzen nach:

Zander, Robert <1892 - 1969> [Begründer]: Der große Zander : Enzyklopädie der Pflanzennamen / Walter Erhardt ... -- Stuttgart : Ulmer, ©2008. -- 2 Bde ; 2103 S. -- ISBN 978-3-8001-5406-7.

WARNUNG: dies ist

der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen Textes. Es

ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier genannten

Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut

ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen machen!

Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen kompetenter

Āyurvedaspezialisten.

WARNUNG: dies ist

der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen Textes. Es

ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier genannten

Heilmittel wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut

ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen machen!

Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen kompetenter

Āyurvedaspezialisten.

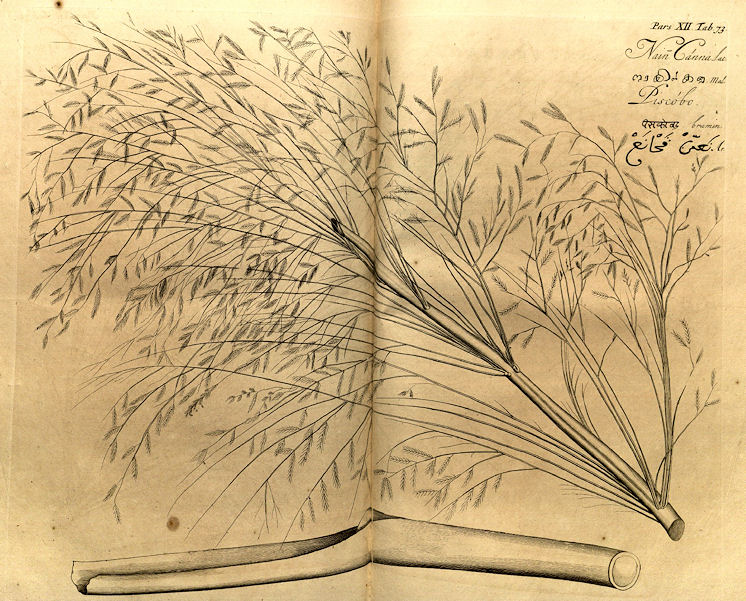

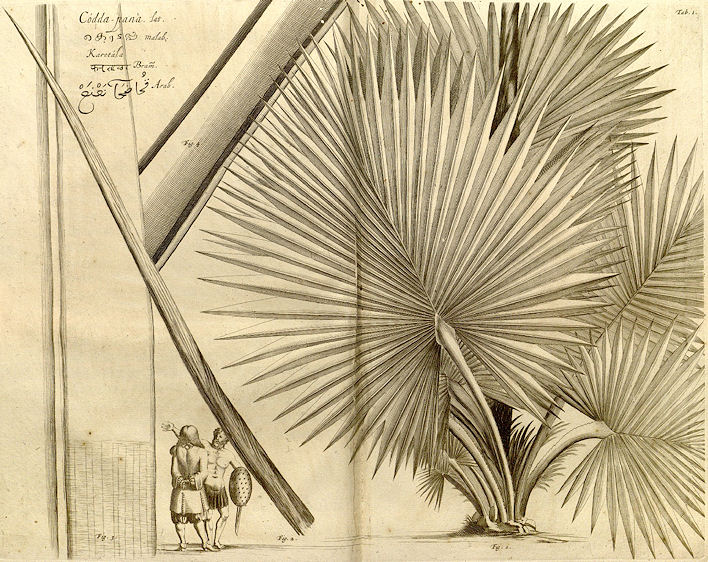

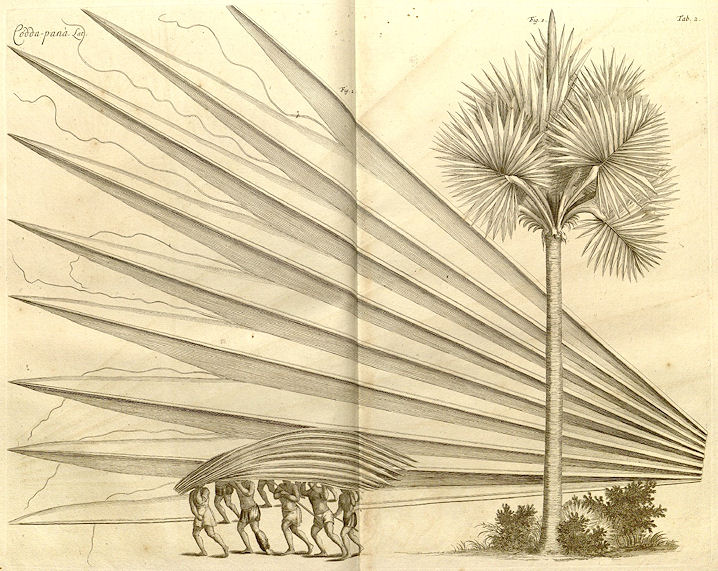

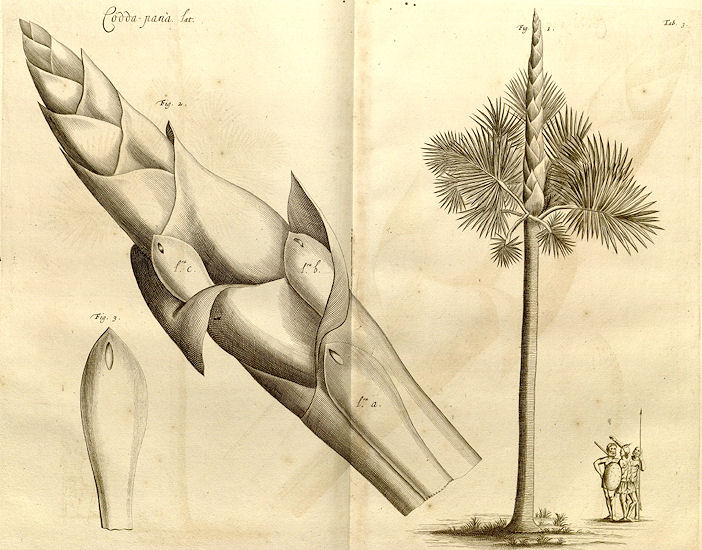

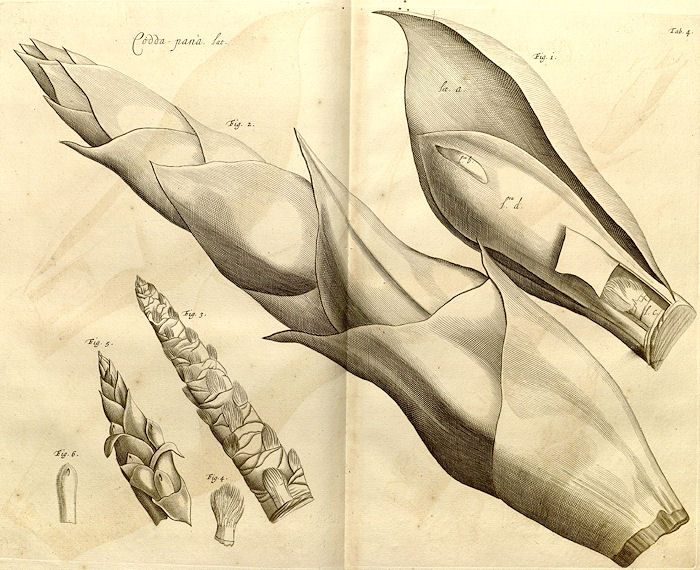

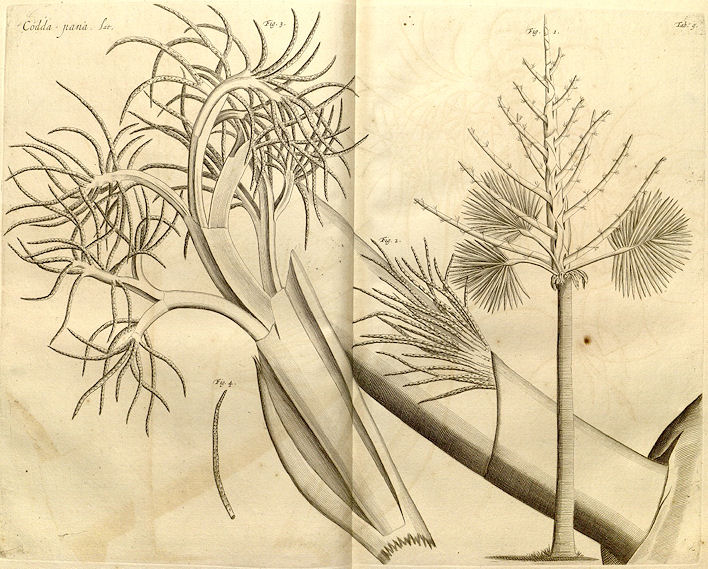

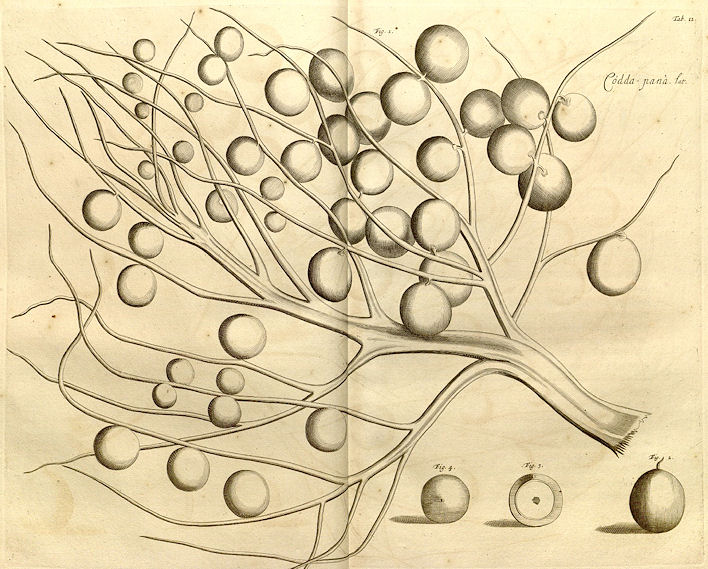

Hortus malabaricus

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus : continens regni Malabarici apud Indos cereberrimi onmis generis plantas rariores, Latinas, Malabaricis, Arabicis, Brachmanum charactareibus hominibusque expressas ... / adornatus per Henricum van Rheede, van Draakenstein, ... et Johannem Casearium ... ; notis adauxit, & commentariis illustravit Arnoldus Syen ... -- 11 Bde. -- Amstelaedami : sumptibus Johannis van Someren, et Joannis van Dyck, 1678-1703. -- Online: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/b11939795. -- Zugriff am 2010-01-01

Zu den Identifikationen siehe:

Dillwyn, L. W. (Lewis Weston) <1778-1855>: A review of the references to the Hortus malabaricus of Henry Van Rheede Van Draakenstein [sic]. -- Swansea : Printed at the Cambrian-Office, by Murray and Rees, 1839.

Roxburgh

Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Plants of the coast of Coromandel, selected from drawings and descriptions presented to the hon. court of directors of the East India company / by William Roxburgh. Published by their order under the direction of Sir Joseph Banks <1743 - 1820> ... -- London : Printed by W. Bulmer for G. Nicol, 1795-1819. -- 3 Bde. : 300 kolorierte Tafeln ; 59 cm. -- Online: http://www.botanicus.org/title/b12006488 usw. -- Zugriff am 2009-09-19

Wight Icones

Wight, Robert <1796 - 1872>: Icones plantarum Indiae Orientalis :or figures of Indian plants. -- 6 Bde. -- Madras : published by J.B. Pharoah for the author, 1840-1853. -- Online: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/92. -- Zugriff am 2010-01-01

Wight Illustrations

Wight, Robert <1796 - 1872>: Illustrations of Indian botany :or figures illustrative of each of the natural orders of Indian plants, described in the author's prodromus florae peninsulae Indiae orientalis. -- 2 Bde. + Suppl. -- Madras : published by J. B. Pharoah for the author, 1840-1850. -- Online: http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/9603. -- Zugriff am 2010-01-01

Kirtikar-Basu

Kirtikar, K. R. ; Basu, B. D.: Indian medical plants with illustrations. Ed., revised, enlarged and mostly rewritten by E. Blatter, J. F. Caius and K. S. Mhaskar. -- 2. ed. -- Dehra Dun : Oriental Enterprises. -- 2003. -- 11 Bde : 3846 S. : Ill. ; 26 cm. -- Unentbehrlich! -- Reprint der Ausgabe von 1933, die Abbildungen stammen aus der Ausgabe von 1918

Lamiaceae (Lippenblütler)

|

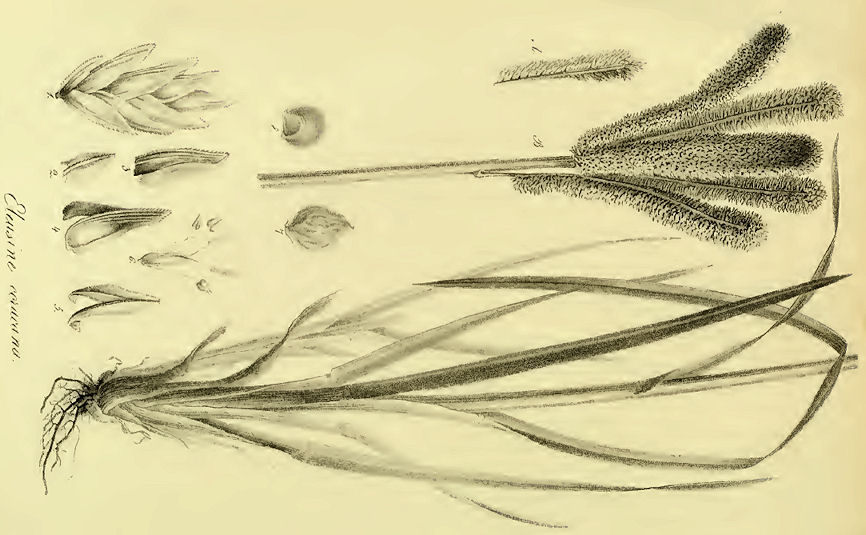

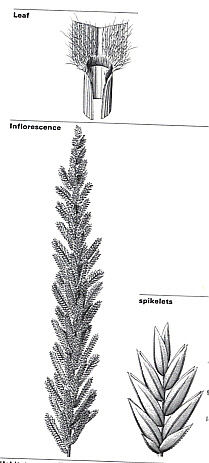

19. janī jatūkā rajanī jatukṛc cakravartinī saṃsparśātha śaṭī gandhamūlī ṣaḍgranthikety api जनी जतूका रजनी जतुकृच्

चक्रवर्तिनी । [Bezeichnungen für Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth. 1848 - Patschuli - Patchouly:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Chacawat. A fragrant plant."

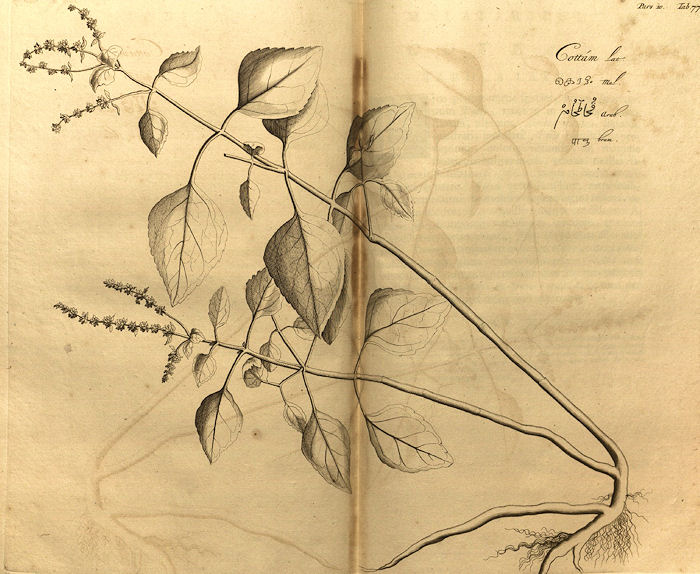

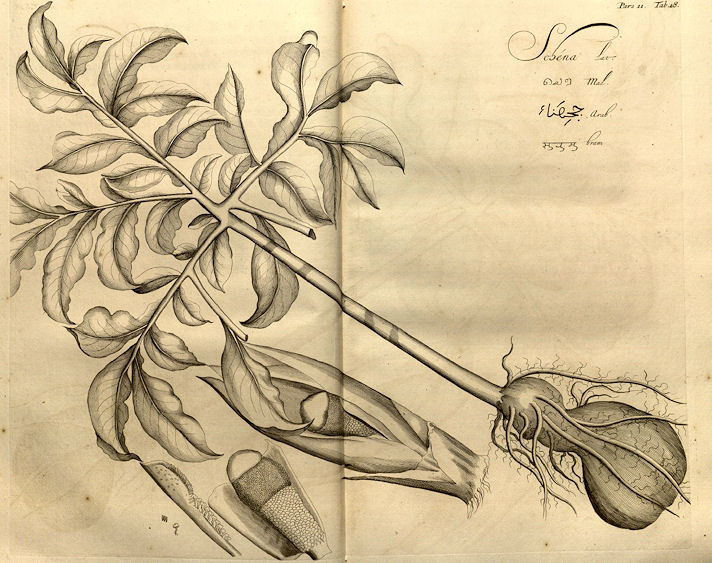

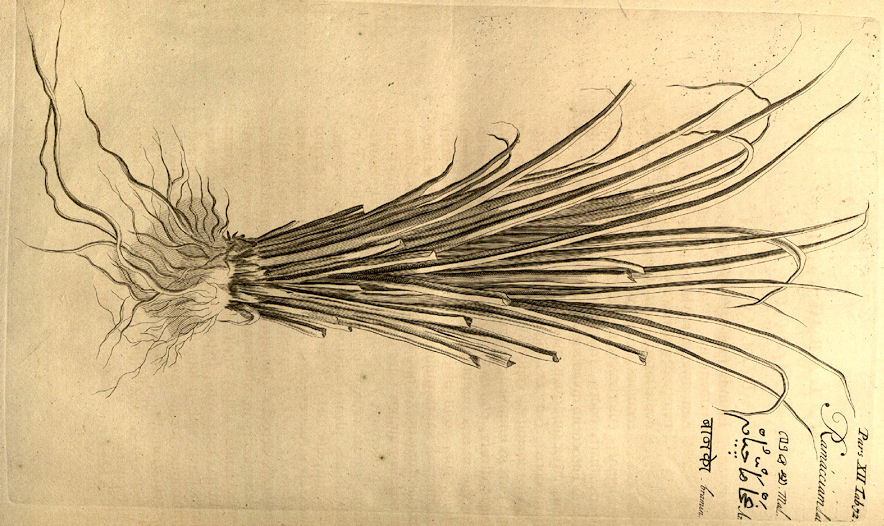

Abb.: जनी । Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth. 1848 - Patschuli - Patchouly

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus X. Fig. 77, 1690]

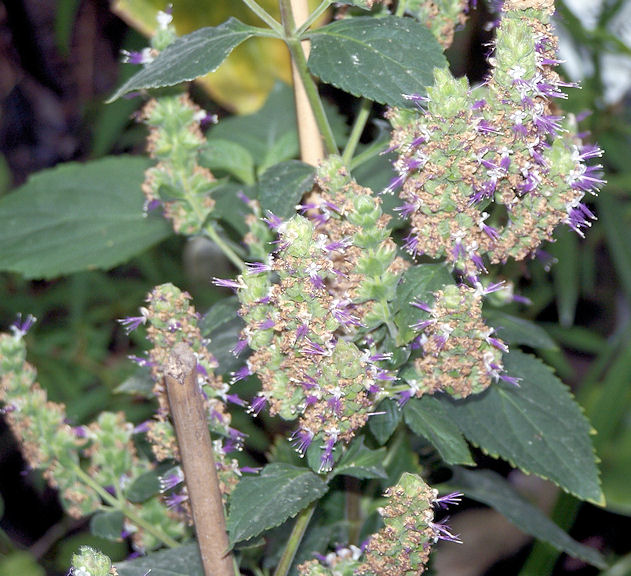

Abb.: रजनी । Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth. 1848 - Patschuli - Patchouly

[Bildquelle: Hooker's journal of botany and Kew Garden miscellany. -- London. --

Vol 1 (1849), Pl. 11.]

Abb.:

चक्रवर्तिनी

। Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth. 1848 - Patschuli - Patchouly,

Göttingen

[Bildquelle: Valérie75 / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Pogostemon Patchouli (Pellet). N. O. Lamiaceae. [...]

Description. — Suffruticose, 2-3 feet, pubesccnt; [...] flowers white, with red stamens and yellow anthers.

Hooker's Journ. of Bot. i. 329.—Benth. in Dec. Prod. xii. 153.—Rheede, x. t. 77.

Silhet.

Economic Uses.—The true identification of this plant was long a matter of discussion among botanists, but the subject has been set at rest by Sir W. Hooker, who managed to raise the plant in the Botanic Gardens at Kew, and which flowered there in 1849. It appears to be a native of Silhet, Penang, and the Malay Peninsula; but the dried flowering-spikes and leaves of the plant, which are used, are sold in every bazaar in Hindostan. From the few scattered notices of this celebrated perfume, it would appear that it is exported in great quantities to Europe, and sold in all perfumers' shops. The odour is most powerful, more so perhaps than that derived from any other plant. In its pure state it has a kind of musty odour analogous to Lycopodium, or, as some say, smelling of "old coats." Chinese or Indian ink is scented by some admixture of it. Its introduction into Europe as a perfume was singular enough, accounted for in the following manner:—

A few years ago, real Indian shawls bore an extravagant price, and, purchasers distinguished them by their odour—in fact, they were perfumed with Patchouly. The French manufacturers had for some time successfully imitated the Indian fabric, but could not impart the odour. At length they discovered the secret, and began to import this plant to perfume articles of their make, and thus palm off home-spun shawls as real Indian ones. From this origin the perfumers have brought it into use. The leaves powdered and put into muslin bags prevent cloths from being attacked by moths.

Dr Wallich states that a native friend of his told him that the leaf is largely imported by Mogul merchants ; that it is used as an ingredient in tobacco for smoking, and for scenting the hair of women; and that the essential oil is in common use among the superior classes of the natives, for imparting the peculiar fragrance of the leaf to clothes. It is exported in great quantities from Penang. The Arab merchants buy it chiefly, employing it for stuffing mattresses and pillows, asserting that it is very efficacious in preventing contagion and prolonging life. For these purposes no other preparation is required, save simply drying the plant in the sun, taking care not to dry it too much, lest the leaves become too brittle for packing. In Bengal it has cost Rs. 11-8 per maund, but the price varies. It has been sold as low as Rs. 6. The drug has been exported from China to New York, and from thence to England. The volatile oil is procured by distillation. The Sachets de Patchouli, which are sold in the shops, consist of the herb, coarsely powdered, mixed with cotton root and folded in paper. These are placed in drawers and cupboards to drive away moth and insects. The P. Heyneanum (Benth.) is probably merely a variety, with larger spikes and more drooping in habit. This plant is figured in Wallich, Pl. As. Res. i. t. 31. J. Graham states that it is found wild in the Concans. Rheede's synonym probably is the P. Heyneanum, which the natives use for perfuming purposes.—Hooker's Journ. of Bot. Pharm. Journ. viii 574, and ix. 282. Wallich in Med. Phys. Soc. Trans. Plant As. Rar. Simmonds."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

Zingiberaceae (Ingwergewächse)

|

19. c./d.

saṃsparśātha śaṭī gandhamūlī

ṣaḍgranthikety api 20. a./b. karcūro 'pi palāśo 'tha kāravellaḥ kaṭhillakaḥ

संस्पर्शाथ शटी गन्धमूली

षड्ग्रन्थिकेत्य् अपि ॥१९ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe 1810 - Zitwer - Zedgary:]

|

Siehe auch 2.IV.23!

Colebrooke (1807): "Ambahaldi. The Hindi name, here taken from medical writings, appertains to a new species of Curcuma."

1 कर्चूर - karcūra m.: Auripignment

Abb.: Auripigment (gelb) mit einem Restanteil Realgar (rot)

[Bildquelle: Parent Géry / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

"Auripigment (lat., Operment, gelbe Arsenblende, Rauschgelb), Mineral, findet sich in kleinen, rhombischen Kristallen, häufiger derb, eingesprengt, in Trümmern, knollig, traubig, nierenförmig, ist wenig durchscheinend, zitronen- oder pomeranzengelb, mit schwachem Fettglanz, Härte 1,5–2, spez. Gew. 3,4–3,5, besteht aus Schwefelarsen As2S3 und findet sich vornehmlich in Ungarn und Siebenbürgen, mit Realgar, Quarz und Kalkspat in Mergeln und tonigen Sandsteinen, mit Bleiglanz, Schwefelkies etc. auf Erzgängen, auch auf Gängen im Tonschiefer, zu Andreasberg, in der Walachei, China, Mexiko, in Kraterspalten am Ätna und Vesuv. Über künstliches A. s. ð Arsensulfide." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

2 पलाश - palāśa m.: Palāśa

palāśa m. = Butea monosperma (Lam.) Kurtz - Malabar-Lackbaum - Flame of the Forest

Abb.: पलाशः । Butea monosperma (Lam.)

Kurtz - Malabar-Lackbaum - Flame of the Forest, Bangalore,

Karnataka

[Bildquelle: SumaTagadur / Wikimedia. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

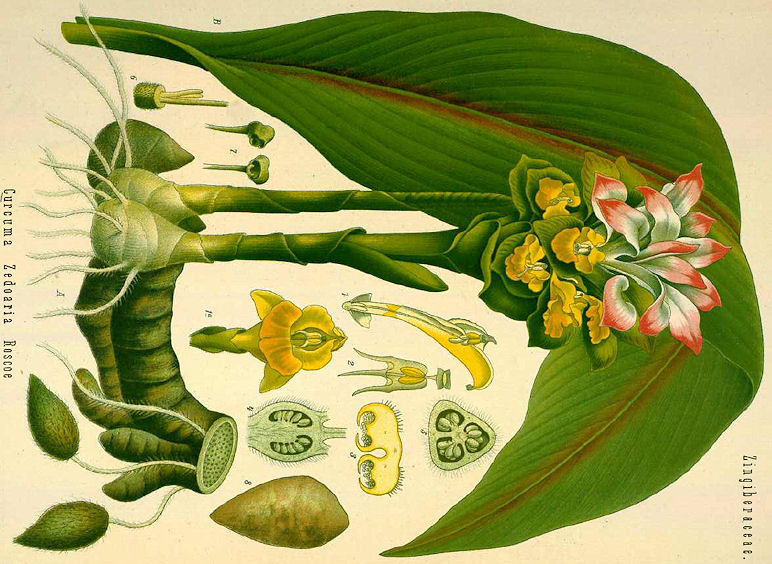

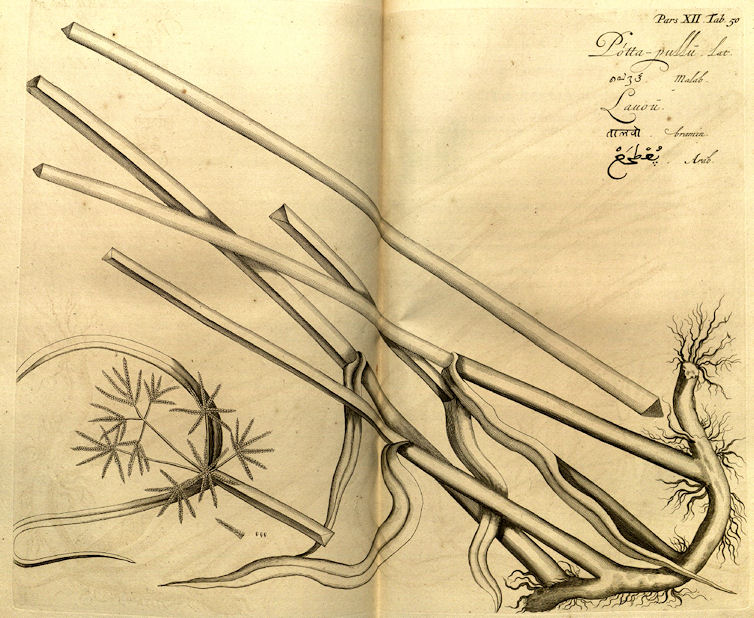

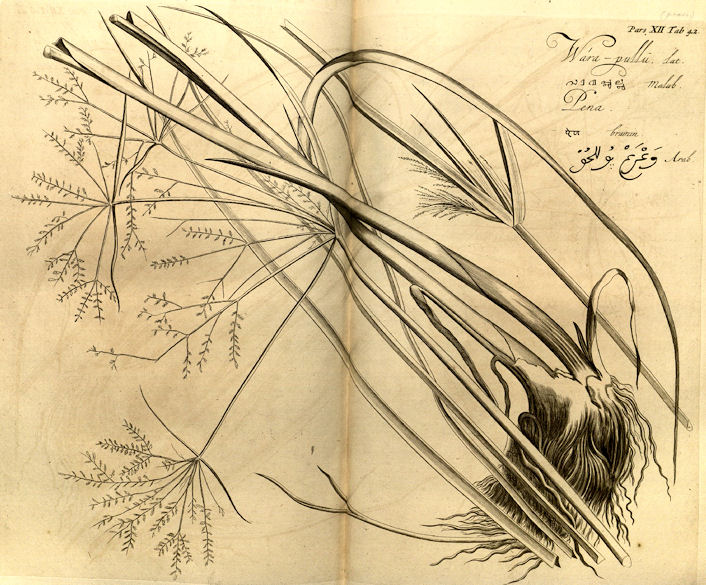

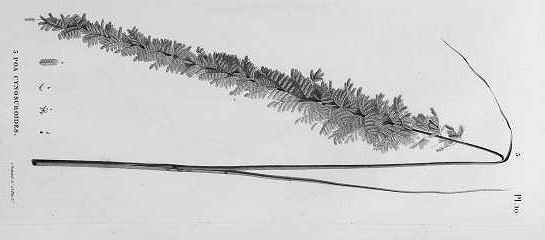

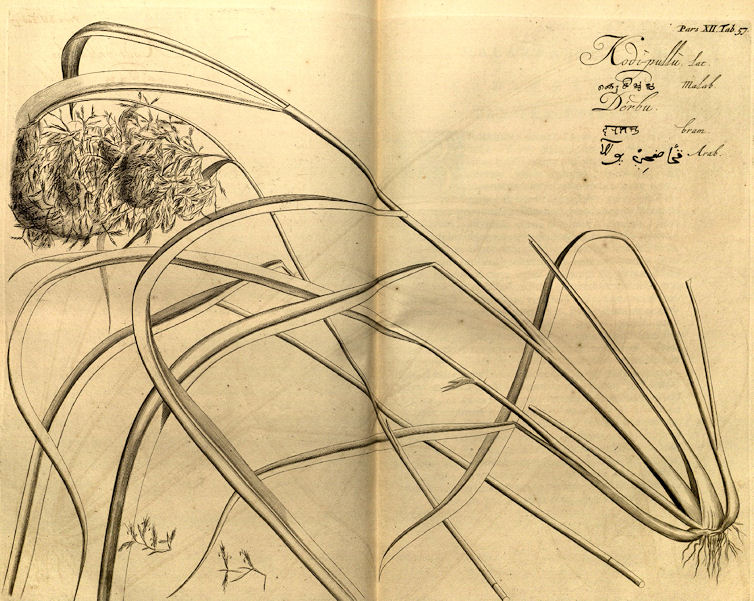

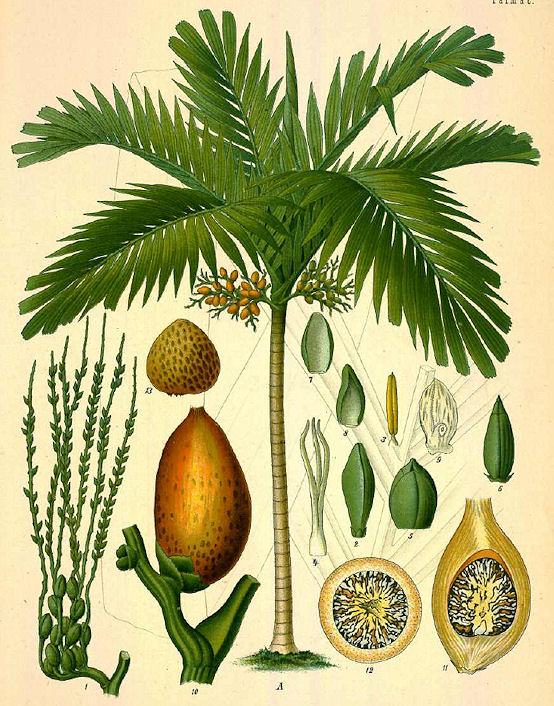

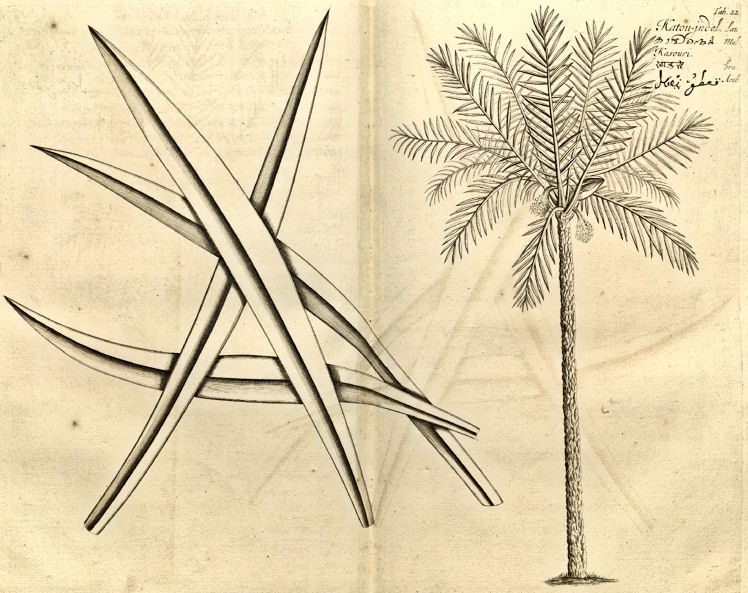

Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe 1810 - Zitwer - Zedgary

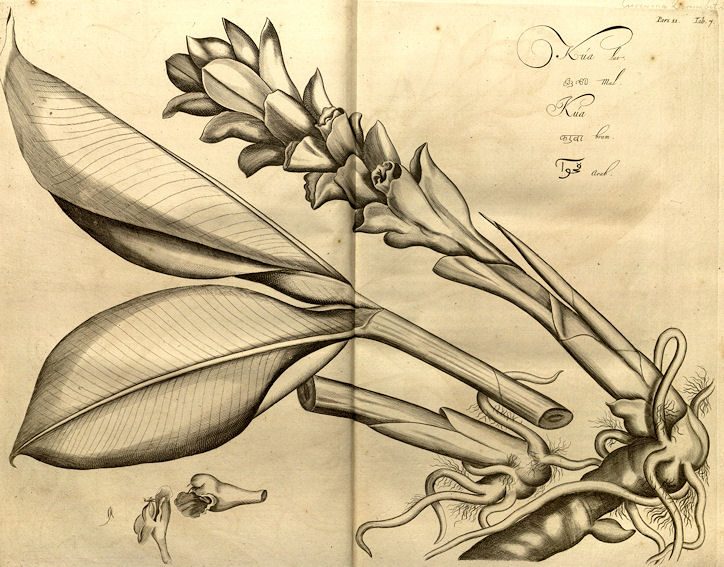

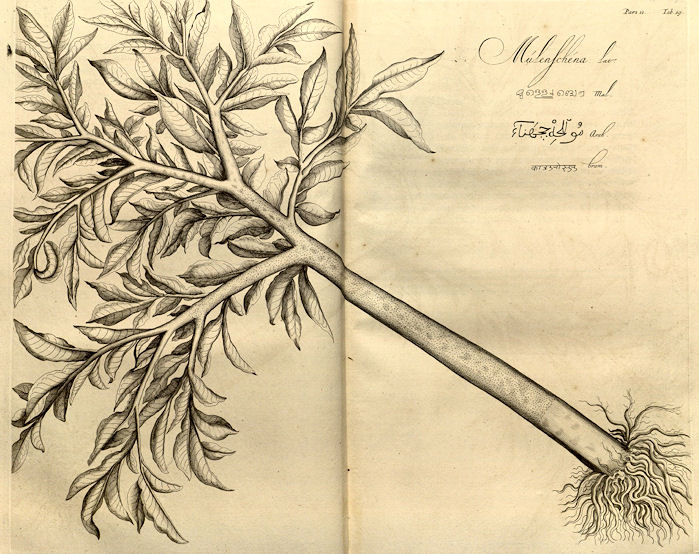

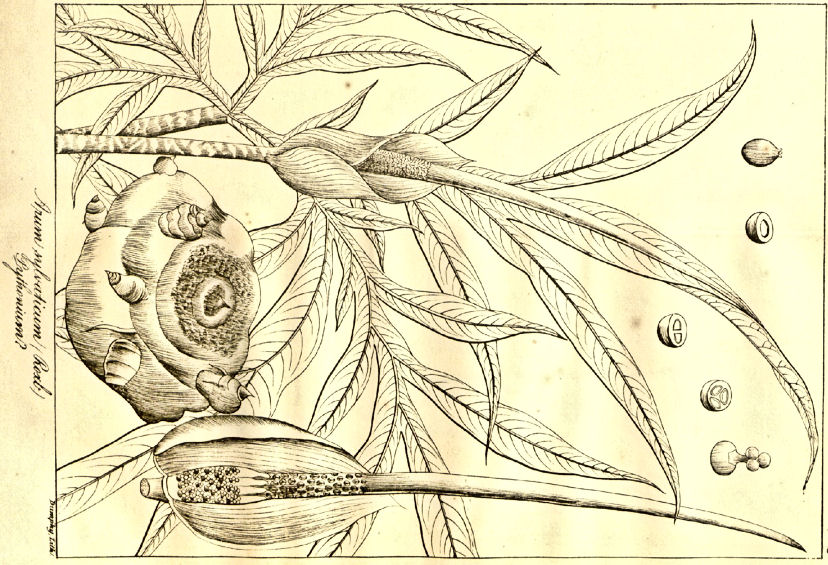

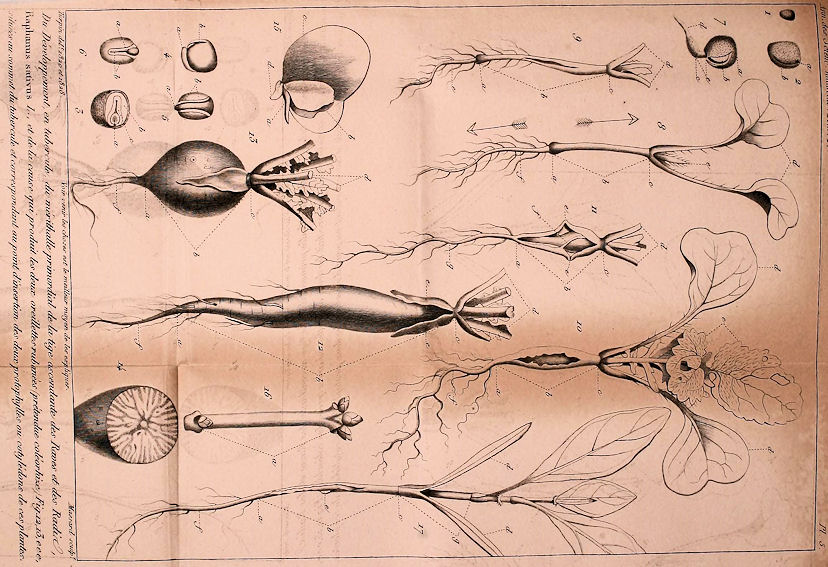

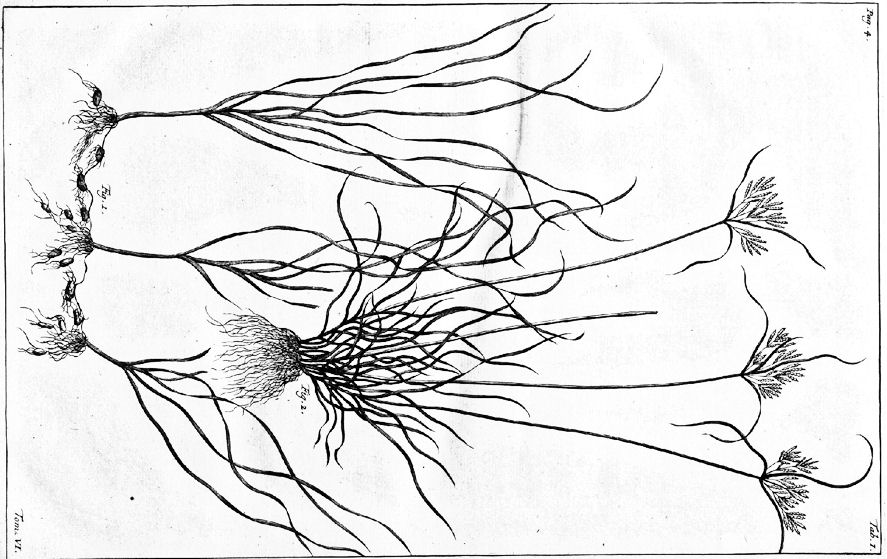

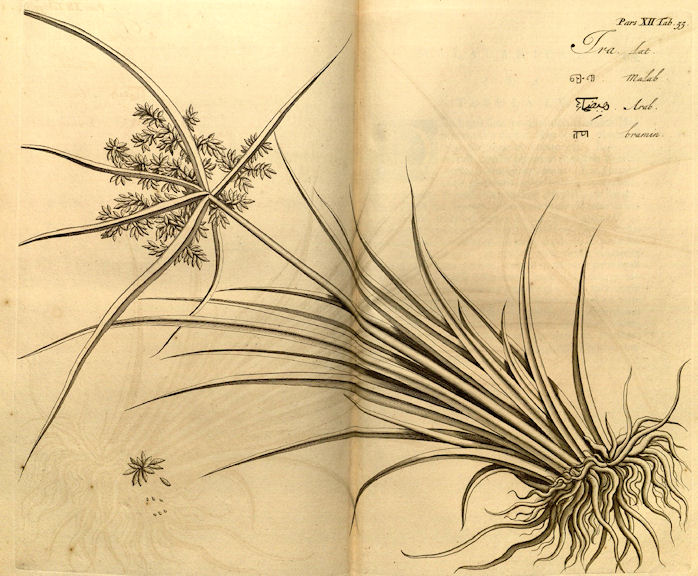

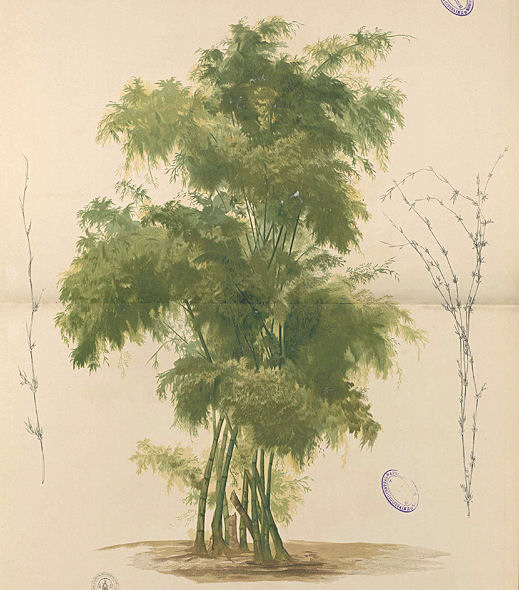

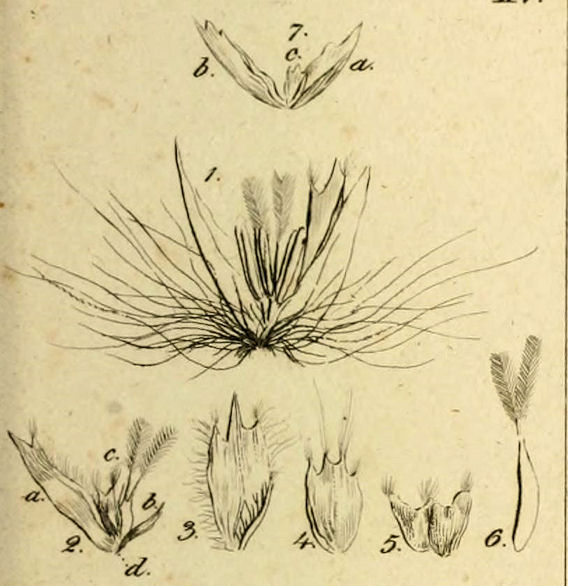

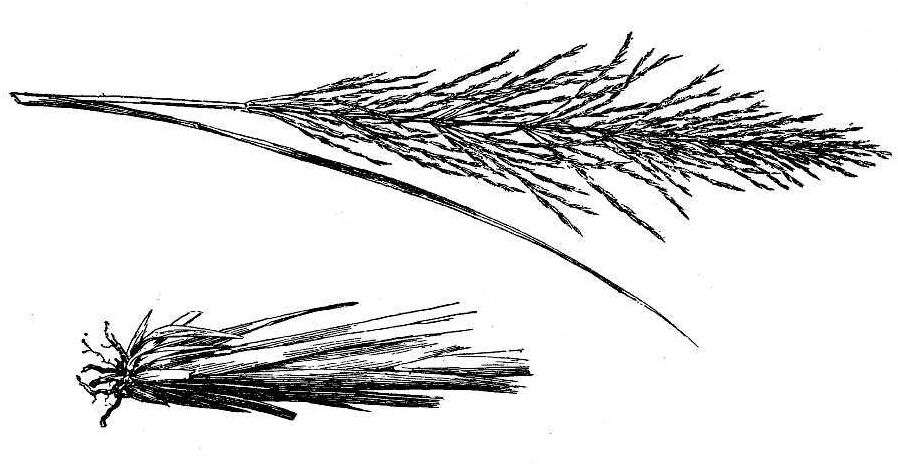

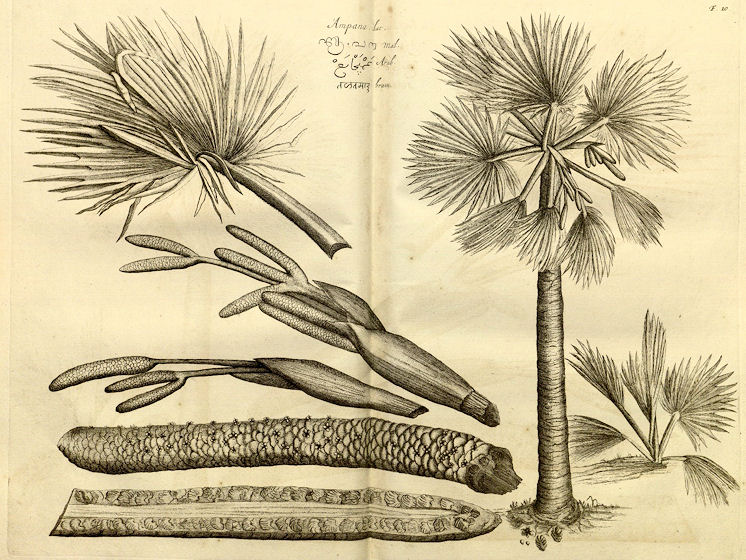

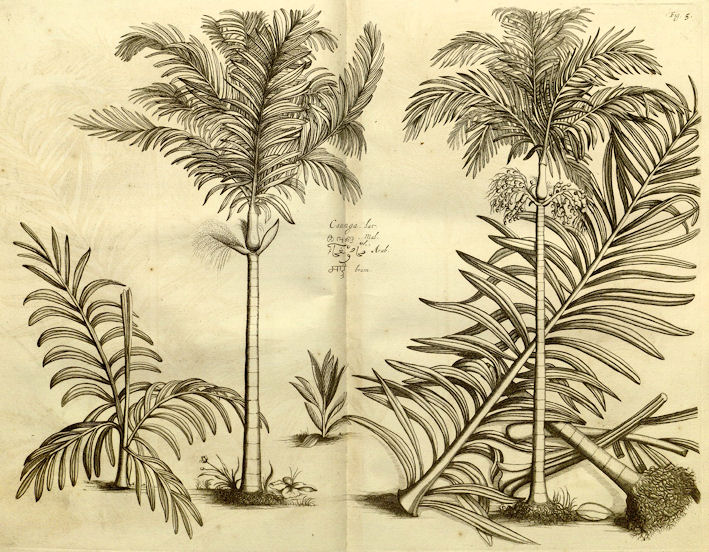

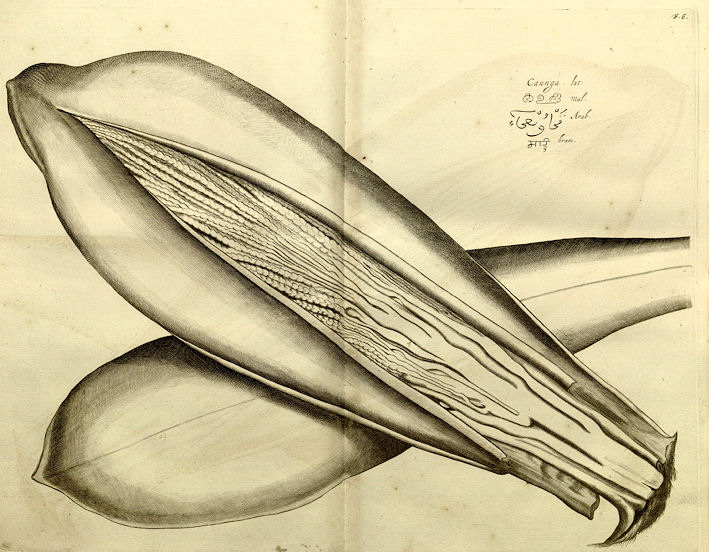

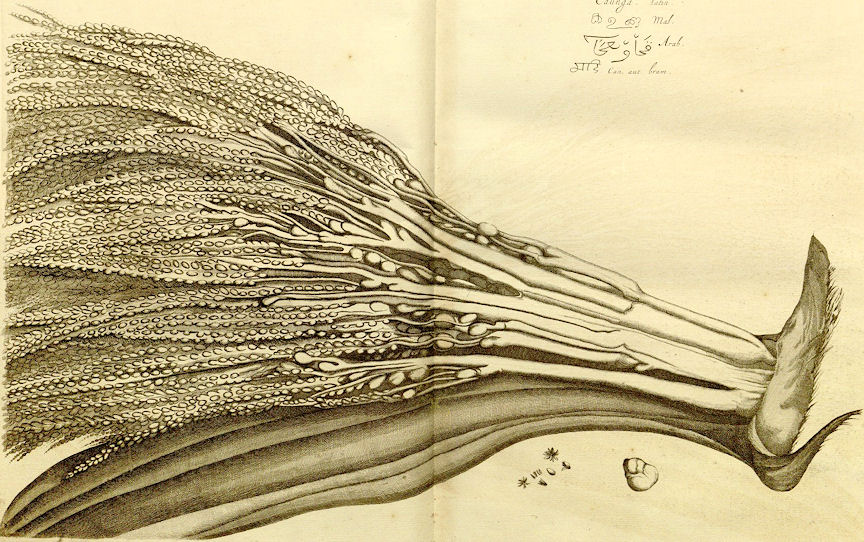

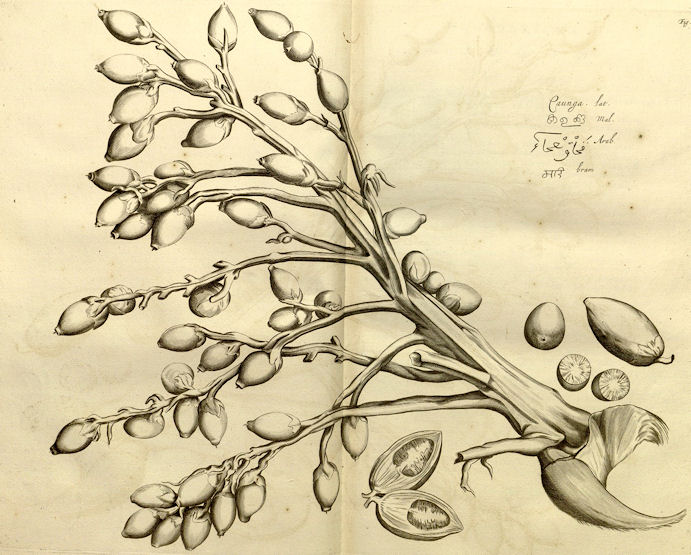

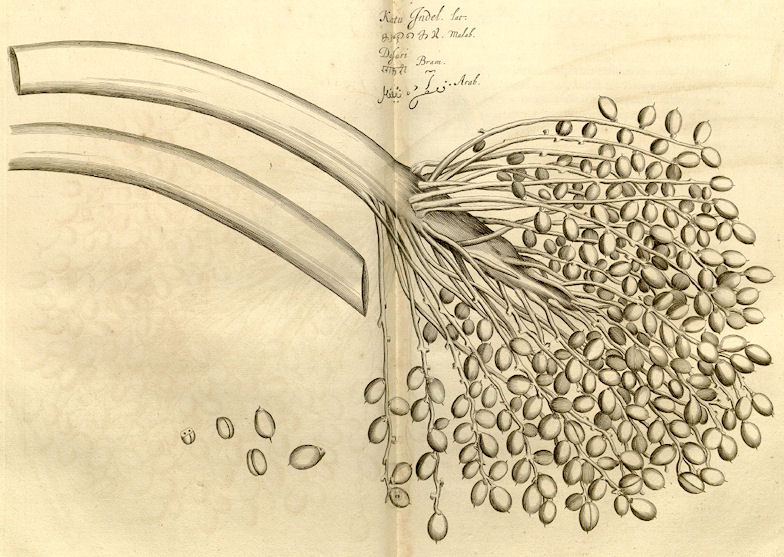

Abb.: Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe 1810 - Zitwer - Zedgary

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus XI. Fig. 7, 1692]

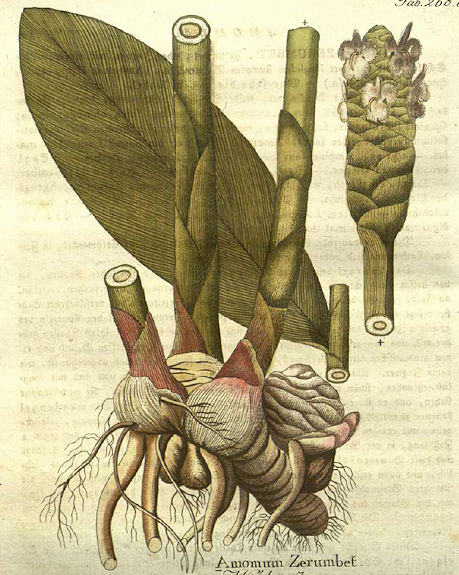

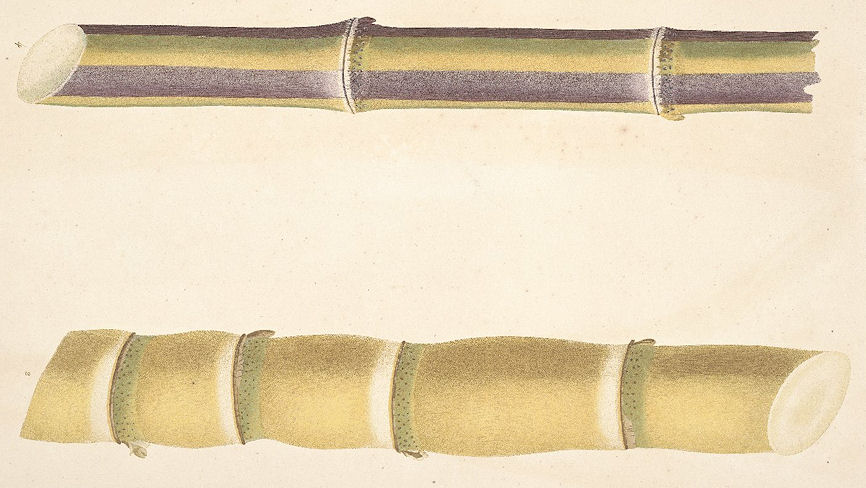

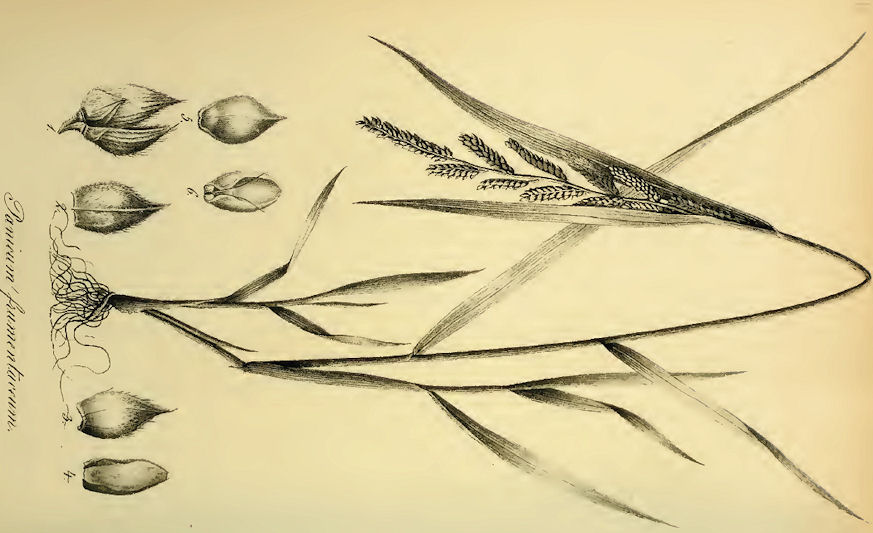

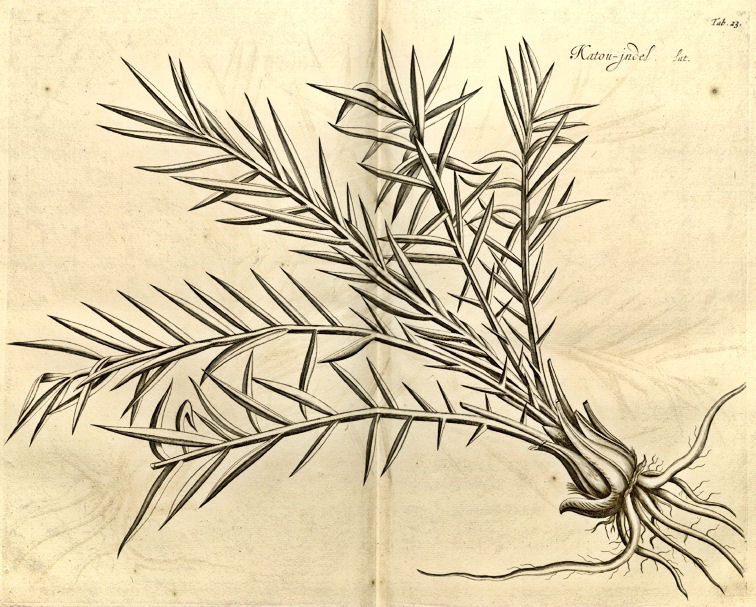

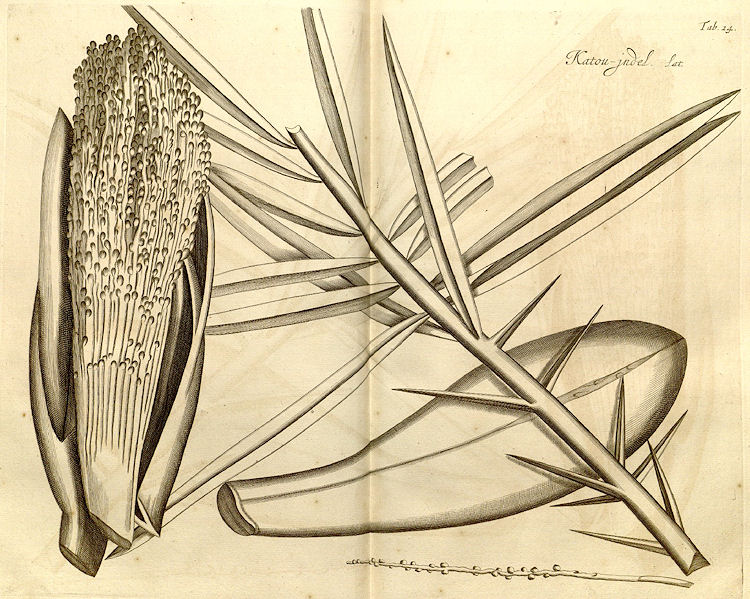

Abb.:

षड्ग्रन्थिका

। Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe 1810 - Zitwer - Zedgary

[Bildquelle: Icones plantarum medico-oeconomico-technologicarum cum earum

fructus ususque descriptione =Abbildungen aller

medizinisch-ökonomisch-technologischen Gewächse mit der Beschreibung ihres

Gebrauches und Nutzens. -- Wien, 1800 - 1822. -- Bd. 3, Tab. 268b]

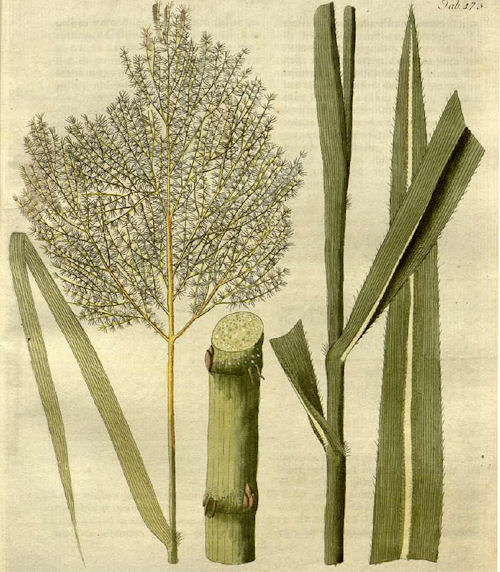

Abb.:

कर्चूरः । Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe 1810 - Zitwer -

Zedgary

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883-1914]

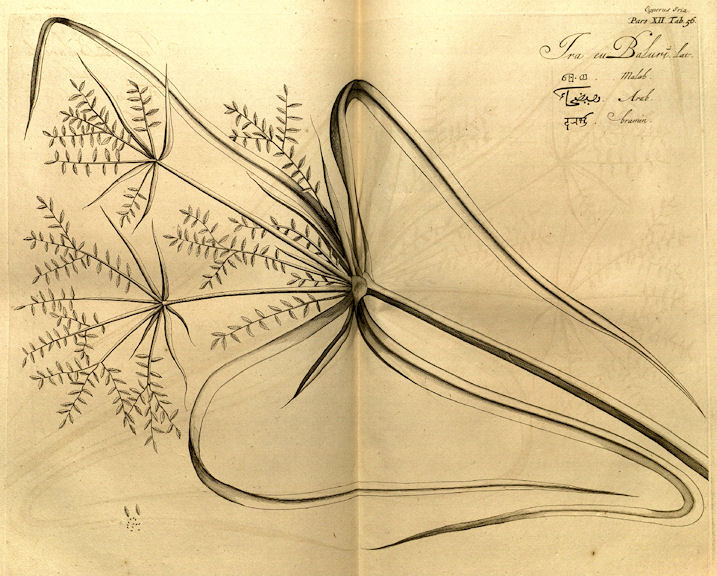

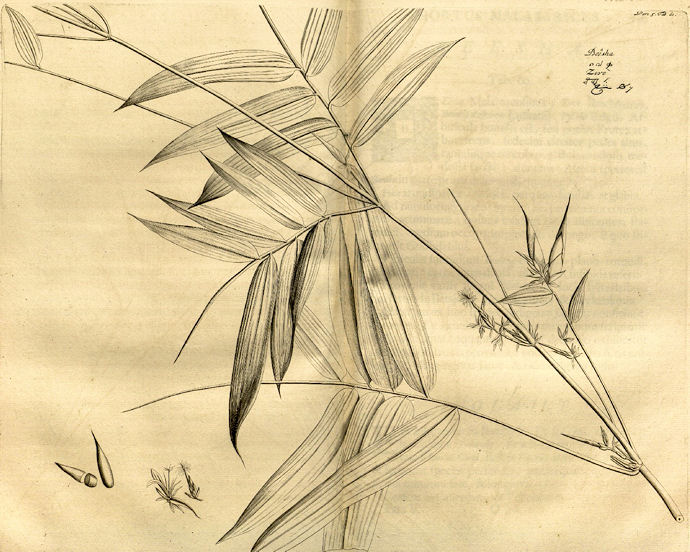

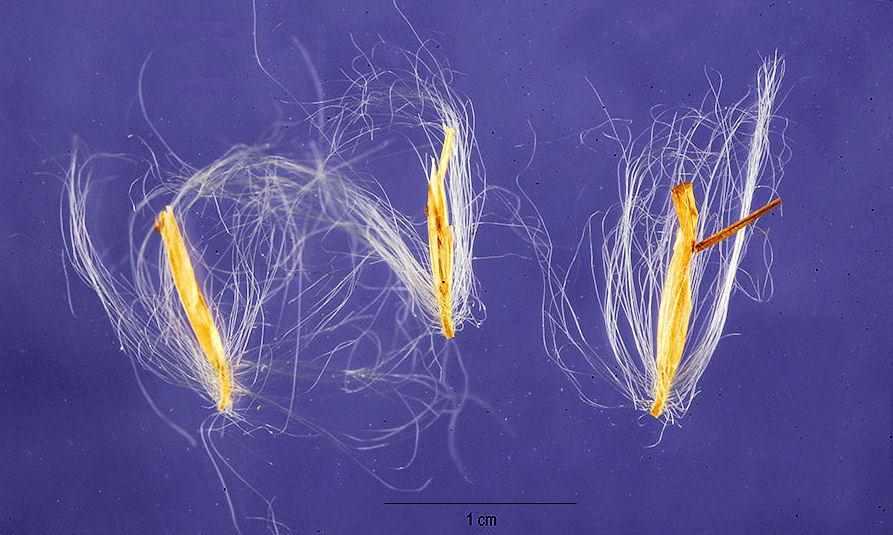

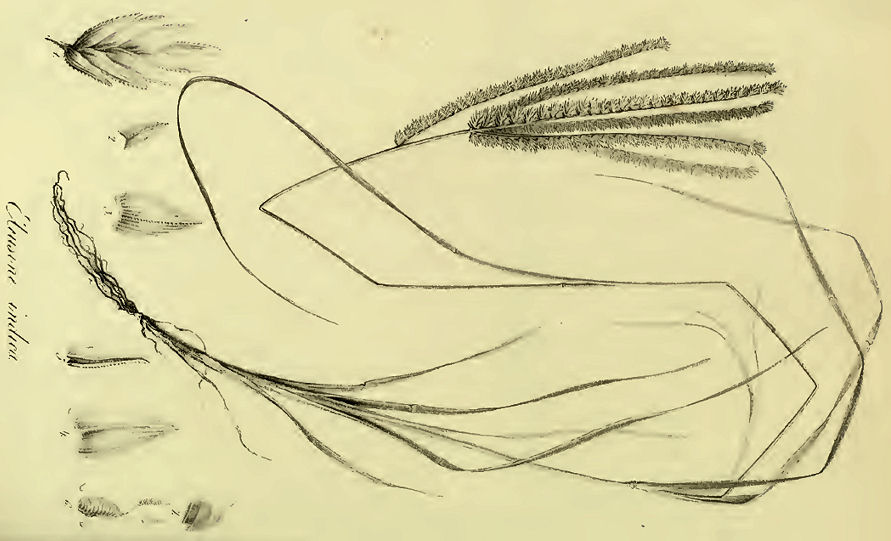

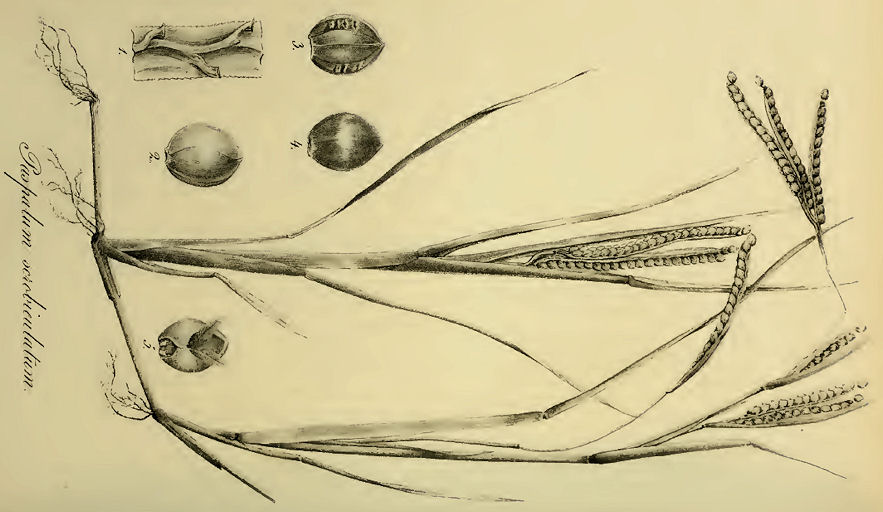

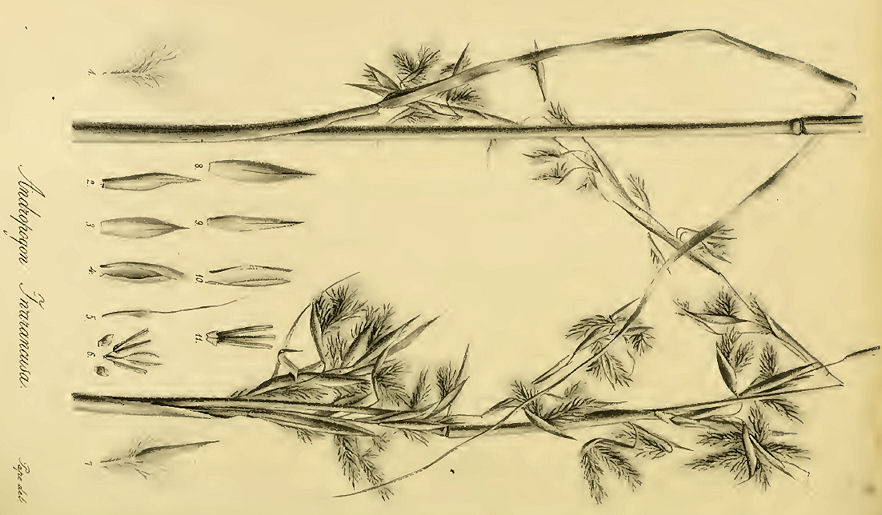

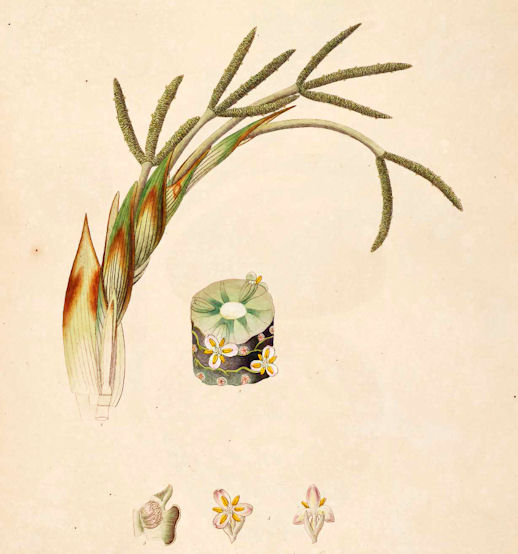

Abb.:

षड्ग्रन्थिका

। Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe 1810 - Zitwer - Zedgary (Roxb.:

Curcuma zerumbet)

[Bildquelle: Roxburgh. -- Vol III. -- 1819. -- Image courtesy Missouri Botanical

Garden. http://www.botanicus.org. --

Creative Commons Lizenz

(Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: पलाशः । Curcuma zedoaria (Christm.) Roscoe 1810 - Zitwer - Zedgary,

Hongkong - 香港

[Bildquelle:

Kai Yan, Joseph Wong. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/33623636@N08/5000127263/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

"Curcuma Zerumbet. Roxb. Ind. pl. 3. N. 201

[...]

Sans. Shutee, Gundha-moolee, Shud-grunthhika, Kurvoora, Kurchoora, and Pulasha.

Kua. Rheed. Mal. vol. II. p. 13. t. 7.

Zerumbed. Rumph. Amb. 5. p. 168. t. 68.

Amomum Zerumbeth. Kon. in Retz. Obs. 3. 55.

Zerumbet, or Cachora of Garcias.

The plants from which the following description was taken, were sent by Dr. F. Buchanan, from Chittagong, where they are indigenous, to the Botanic garden at Calcutta, in 1798, where they grow freely, and blossom in the month of April. Others have since been procured from thence under the Bengalee name Kuchoora. From that place the native druggists in Calcutta, are chiefly supplied with the root or drug.

[...]

Obs. The dry root powdered and mixed with the powdered wood of the Caesalpinia Sappan makes the red powder called Abeer by the Hindoos, and Phag by the Bengalees. It is copiously thrown about by the natives during the Hooli, or Hindoo holidays in the month of March. The root is also used medicinally amongst the natives.

In 1805, I gave some of the sliced and dried bulbous, and palmate tuberous roots of this plant to Sir Joseph Banks, which he gave to Dr. Comb, who found that it was the real Zedoaria of our Materia Medica, and by the same means ascertained that the root of my Curcuma Zedoaria, is Zedoaria rotunda of the shops."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 1, S. 20ff.]

"Curcuma zedoaria (Roscoe). Long Zedoary [...]

Description.—Height 3-4 feet; [...] flowers deep yellow and bright crimson tuft.

Fl. April.

Wight Icon. t. 2005.

Curcuma zerumbet, Roxb. Fl. Ind. i. ed. Car. 20. — Corom. iii t. 201.—Rheede, xi. t. 7.

Chittagong. Malabar.

Medical Uses.—According to Roxburgh this plant yields the long Zedoary of the shops, though Pereira states that the plant has not been well ascertained. The root is used medicinally by the natives. It is cut into small round pieces, about the third of an inch thick and two in circumference. The best comes from Ceylon, where it is considered tonic and carminative. According to Rheede it has virtues in nephritic complaints. The pulverised root is one of the ingredients in the red powder (Abeer) which the Hindoos use during the Hooly festival.—Roxb. Pereira."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"CURCUMA ZEDOARIA, Rosc.

Fig.—Rosc. Scit., t. 109; Roxb. Cor. Pl., t. 101; Rheede, Hort. Mal. xi., t. 7.

Zedoary

Hab.—Eastern Himalaya, cultivated throughout India.

[...]

History, Uses, &C—This plant is the Sati and Krachura of Sanskrit writers, and the Zerumbād aud Urūk-el-kāfūr, "camphor root," of the Arabians. It is noticed by the later Greek physicians under the name ζοθρομβεδ corruption of the Arabic name, which in the Middle Ages, was variously written as Zeruban, Zerumber, and Zerumbet. It is not the ζεδοαρ of Aetius (A. D. 540-550) or the τζετουαριον of Myrepsus, or the Zedoar of MacerFloridus (A. D. 1140). Barbosa (1510) speaks of Zedoaria and Zeruban as distinct articles of trade at Cannanore, so that it must have been some time after this date that Zerumbet came into use in Europe as a cheap substitute for the Zedoar of the earlier physicians, which, we have no doubt, was the same drug as the Jadwar of the Arabians. This name, correctly written by Aetius, is the Zhedwar of the ancient Persians, and is described in the Burhān (A. D. 1040) as a drug used as an antidote to poisons, the same as the Jadwār of the Arabians, and also called Mahparvin. Ibn Sina of Bokhara, who lived about the same time (980—1037), describes Jadwār shortly in the following words:—

"it has the form of the root of Aristolochia, but is smaller." Haji-Zein-cl-attār, the well-known Persian physician and apothecary, and the author of the "Ikhtiarāt" (A. D. 1308), describes Jadwār as a root about the size and shape of the Indian Cyperus root, but harder and heavier, and the same as the Indian drug Nirbisi, the best internally of a purplish tint. He states that there are, as far as his experience goes, four drugs sold as Jadwār, viz., a white kind, a purplish, a black and a yellow ; the people of Cathay call the yellow kind Kurti and the purplish Burbi, the other two kinds come from India. As to the locality in which the drug is collected, he states that there is a mountain called Farājal between India and Cathay, where the plant grows along with the aconite, and that the latter, whenever it grows near the Jadwār, loses its poisonous properties and is eaten with impunity by the inhabitants. Where the Jadwār does not grow, the aconite (Bish) is a deadly poison, and is called Halālal by the natives (Halahala, Sanskrit). In the Dict. Econ. Prod. of India (ii., p. 656), the following account of certain drugs collected in Nepal by Dr. Gimlette, the Residency Surgeon, substantially confirms Haji-Zein's description of Jadwār or Nirbisi:—According to Dr. Gimlette, "the Kala bikh of the Nepalese (the Dulingi of the Bhoteas) is a very poisonous form of Aconitum ferox, so poisonous, indeed, that the Katmandu druggist will not admit they possess any. Pahlo (yellow) bikh is a less poisonous form of the same plant, known to the Bhoteas as Holngi, while Setho (white) bikh (the Nirbisi sen of the Bhoteas) is A. Napellus, and Atis is Aconitum heterophyllum. The aconite adulterants or plants used for similar purposes are, Cynanthus lobatus, the true Nirbisi of Nepal, the root of which is boiled in oil, thus forming -a liniment which is employed in chronic rheumatism, Delphinium denudatum, the Nilo (blue or purplish) bikh of the Nepalese and the Nirbisi of the Bhoteas, Dr. Gimlette says, is used by the Baids of Nepal for the same purposes as the Setho and Pahlo bikh. Geranium collinum (var. Dunianum) is the Ratho (red) bikh of the Nepalese, and the Nirbisi-num of the Bhoteas, and, like the Setho bikh, is given as a tonic in dyspepsia, fevers, and asthma. Lastly, a plant never before recorded as used medicinally, namely, Caragana crassicaulis, is known as the Artiras of the Nepalese, and the Kurti of the Bhoteas; it affords a root which is employed as a febrifuge."

The Jadwār or Nirbisi myth appears to have been invented in the East to account for the curious occurrence on the Himalayas of poisonous and non-poisonous aconites growing side by side (see Vol. I., pp. 1, 15, 18, 20).

It would appear also that the Curcumas have no claim to the name of zedoary, which was probably first given to them about the middle of the 16th century, as Clusius's figure of Gedwar is certainly meant for the pendulous tuber of a Curcuma. The on of the cheaper for the more expensive article is rendered highly pvobable by the fact that Zerumbet was considered by the Arabians to be very little inferior to Jadwār as an antidote to poisons. Ibn Sina, Ibn Baitar, and Ibn Jazla in the Minhāj use almost the same word-in speaking of these drugs ; of Jadwār they say :

"it is an antidote for all poisons, even those of aconite and the viper"; and of Zerumbet —

"it is most useful against the bites of venomous annuals, and is almost equal to Jadwār."

Both drugs were considered to have properties similar to Darunaj (see Vol. II., p. 292). Ainslie (Mat Ind., i, 492) remarks that C. Zedoaria is the Lampooyang of the Javanese, and the Lampuium of Rumphius (Herb. Amb. V., p. 148), and that it is a native of the East Indies, Cochin-China, and Otaheite. He quotes Geoffrey's description of the drug, which leaves no doubt as to it- identity with the modern Kachora—"Foris cinerea, intus candida; sapore acri-amaricante aromatico; odore tenui fragrante, ac valde aromaticum suavtatem, cum tunditur aut manducatur, spirante et ad camphoram aliquatenus accedente." Guibourt states that C. Zedoaria is the Zerumbet of Serapion, Pomet, and Lemery. The following is his description of it :—"The round zedoary is greyish-white externally heavy, compact, grey and often horny internally, laving a bitter and strongly camphoraceous taste, like that of the long zedoary, which it also resembles in odour. The odour of both drugs is analogous with that of ginger, but weaker unless the rhizome be powdered, when it developes a powerful aromatic odour, similar to that of cardamoms." (Hist. Nat. 6me Ed., Vol. II., p. 213.) In our opinion there is no doubt that C. Zedoaria is the source of the round and long zedoary of commerce. The plant is common in Bombay gardens, and was probably introduced by the Portuguese, whose descendants and converts at the present day use the leaves in cookery, especially with fish. From Dr. Hove's account of Bombay in 1787 it appears that Kachura and Turmeric were cultivated at that time in the cocoanut woods at Mahim. The natives chew the root to correct a sticky taste in the mouth ; it is also an ingredient in some of the strengthening conserves which are taken by women to remove weakness after child-birth. In colds it is given in decoction with long-pepper, cinnamon and honey, and the pounded root is applied as a paste to the body. Rheede says that the starch of the zedoary is much esteemed, and that the fresh root is considered to be cooling and diuretic, it checks leucorrhoeal and gonorrhoeal discharges and purifies the blood. The juice of the leaves is given in dropsy. One of us has had the plant in cultivation for some years ; it blossoms in the hot weather just before the rains, when the first leaves begin to appear."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 399ff.]

Cucurbitaceae (Kürbisgewächse)

|

20.

karcūro 'pi palāśo

'tha kāravellaḥ kaṭillakaḥ suṣavī cātha kulakaṃ patolas tiktakaḥ paṭuḥ

कर्चूरो

ऽपि

पलाशो

ऽथ कारवेल्लः कटिल्लकः । [Bezeichnungen für Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter Melon:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Momordica charantia."

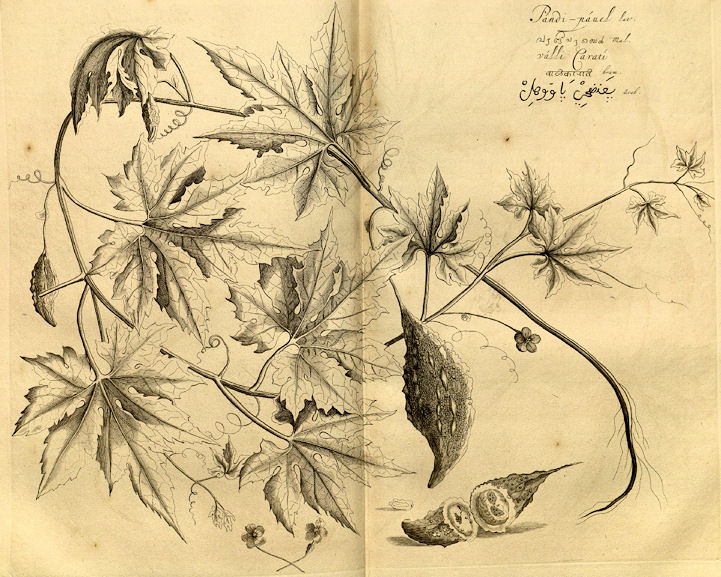

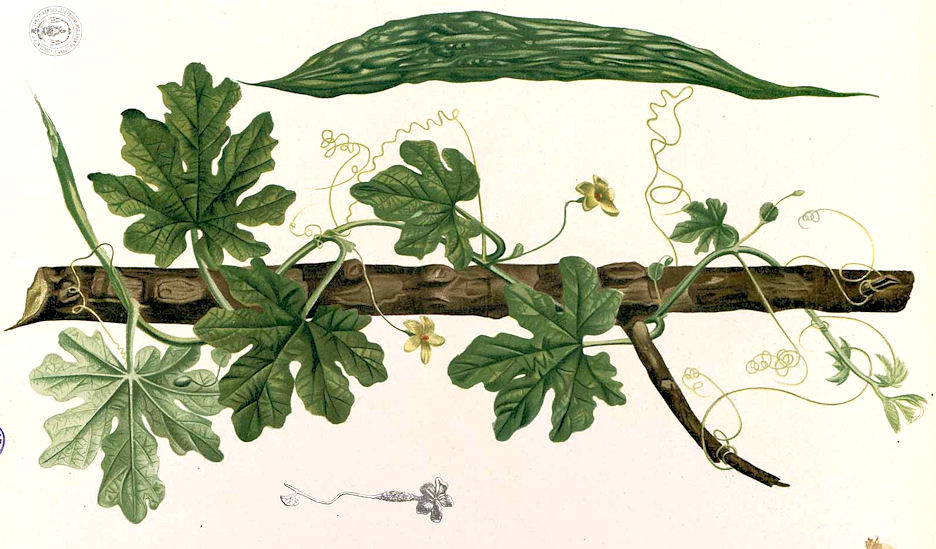

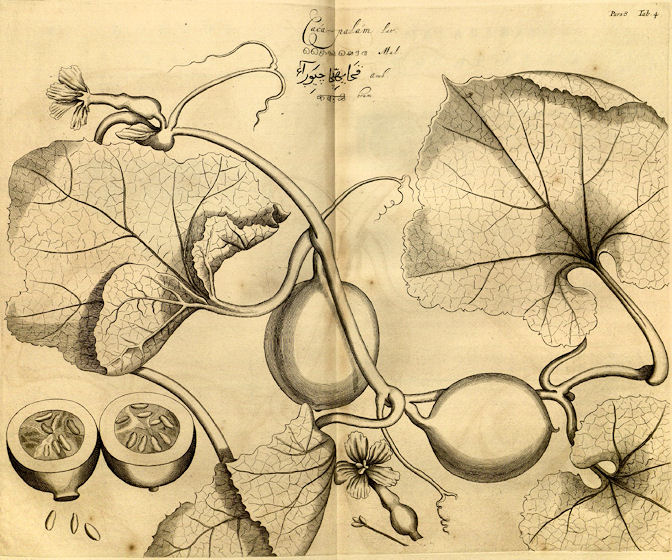

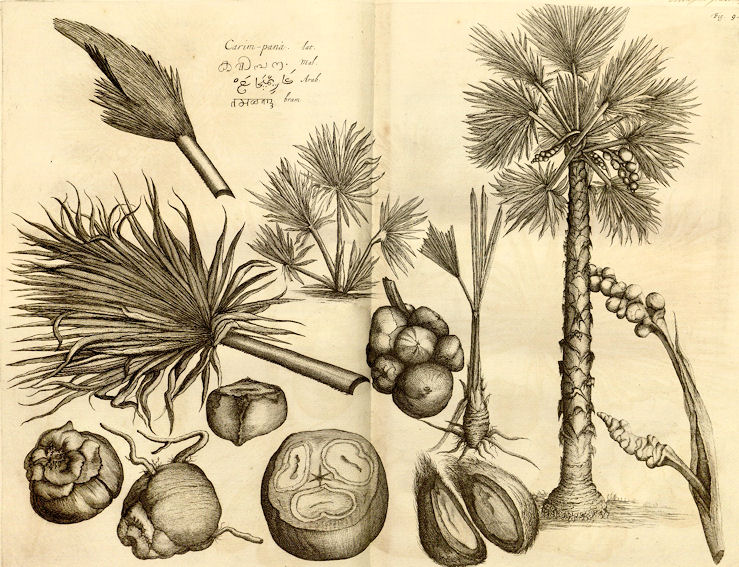

Abb.: कारवेल्लः । Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter

Melon

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VIII. Fig. 9, 1688]

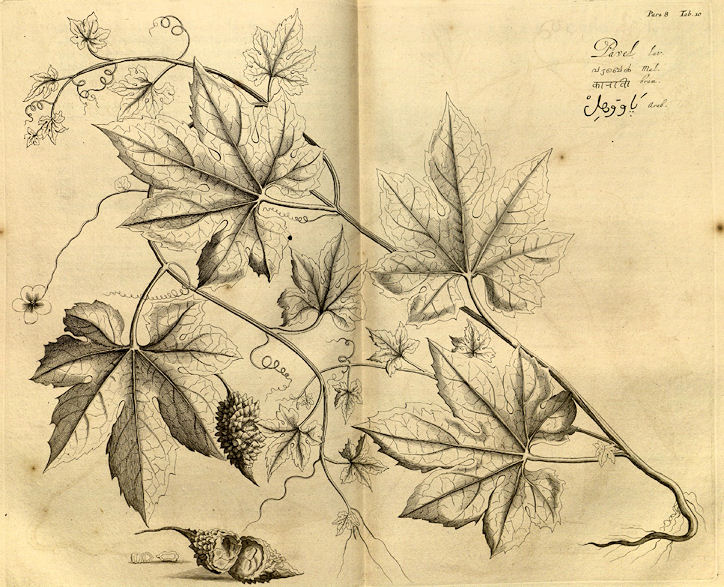

Abb.: Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter

Melon

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VIII. Fig. 10, 1688]

Abb.: Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter

Melon

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine, v. 51 (1824), Tab. 2455]

Abb.: Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter

Melon

[Bildquelle: Wight Icones II, Tab. 504, 1843]

Abb.: Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter

Melon

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas, 1880 / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter

Melon

[Bildquelle: Aruna / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter

Melon

[Bildquelle: Aruna / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Bittergurke - Balsam Pear / Bitter

Melon

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Momordica Charantia. Willd. iv. 602.

[...]

Pandi-pavel. Rheed. Mal. viii. t. 9.

Amara-indica. Rumph. Amb. v. t. 151.

Cultivated in all the warmer parts of Asia for the fruit, which the natives eat, while unripe, in their curries. The fruits are bitter and reckoned wholesome."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 707.]

"Momordica Charantia (Linn.) N. O. Cucurbitaceae.

[...]

Description.—Climbing; stems more or less hairy; [...] flowers middle-sized, pale yellow.

Fl. Aug.—Oct.

W. & A. Prod. i. 348.—Roxb. Fl Ind. iii. 707.— Wight Icon. ii. t. 504.

M. muricata, Willd.—Rheede Mal. viii. t. 9, 10.

Cultivated everywhere in the Peninsula.

Medical Uses.—There are two chief varieties differing in the forms of the fruit, the one having the fruit longer and more oblong, the other with the fruit smaller, more ovate, muricated, and tubercled. There are besides these many intermediate gradations. The fruit is bitter but wholesome, and is eaten in curries by the natives. It requires, however, to be steeped in salt water before being cooked. That of the smaller variety is most esteemed. The whole plant mixed with cinnamon, long-pepper, rice, and marothy oil (Hydnocarpus inebrians), is administered in the form of an ointment in psora, scabies, and other cutaneous diseases. The juice of the leaves mixed with warm water is reckoned anthelmintic. The whole plant pulverised is a good specific externally applied in leprosy and malignant ulcers.—Rheede. Dr Gibson. Wight."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"MOMORDICA CHARANTIA, Linn.

Fig.—Bot Mag., t. 2455; Wight Ic., t. 504; Bot. Reg., t. 980.

Hab Throughout India.

[...]

Description, Uses, &C.—There are two chief varieties differing in the form of the fruit, the one being longer and more oblong, and the other smaller, more ovate, muricated and tubercled. There are besides many intermediate gradations. The fruit is bitter but wholesome, and is eaten by the natives. It requires, however, to be steeped in salt water before being cooked ; the smaller variety is most esteemed. (Drury.) From Rheede, Wight and Gibson we learn that the Hindus use the whole plant combined with cinnamon, long pepper, rice and the oil of Hydnocarpus Wightiana, as an external application in scabies and other cutaneous diseases. The fruit and leaves are administered as an anthelmintic, and are applied externally in leprosy. One-eighth of a seer of the juice of the leaves is given in bilious affections, as an emetic and purgative, alone or combined with aromatics ; the juice is rubbed in, in burning of the soles of the feet, and with black pepper is rubbed round the orbit as a cure for night blindness. The Sanskrit name is Kāravella, the muricated variety is called Sushavi, and bears the synonym Kāndira or " armed with arrows." The author of the Makhzan-el-Adwiya describes the fruit as tonic and stomachic, and says that it is useful in rheumatism and gout, and in diseases of the spleen and liver ; he also mentions its anthelmintic properties. He points out that some have erroneously supposed it to be identical with the Katha-el-himār of the Arabs, which is a violent purgative. [...]

In the rainy season the plant may be seen in almost every garden in India. The fruit is also offered for sale in the market, and when well cultivated attains the size of a cucumber."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 78f.]

Cucurbitaceae (Kürbisgewächse)

|

20. c./d.

suṣavī cātha

kulakaṃ paṭolas tiktakaḥ paṭuḥ सुषवी चाथ कुलकं पटोलस् तिक्तकः पटुः ॥२० ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Trichosanthes dioica Roxb. - Pointed Gourd:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Trichosanthes. Trichosanthes dioeca, Roxb."

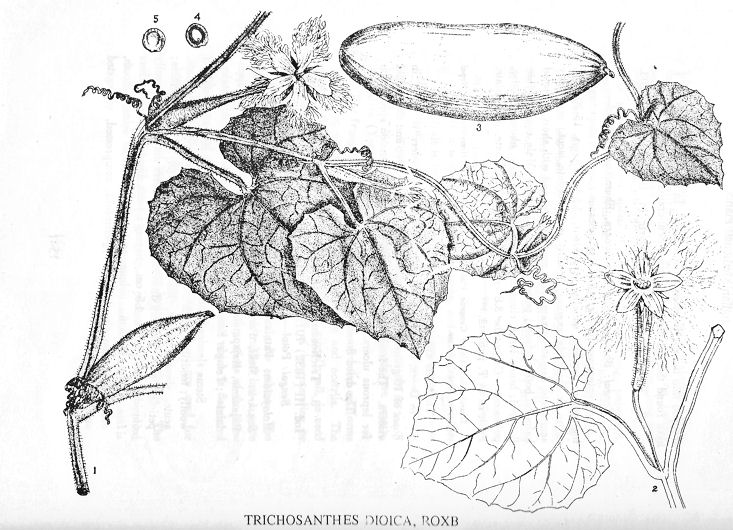

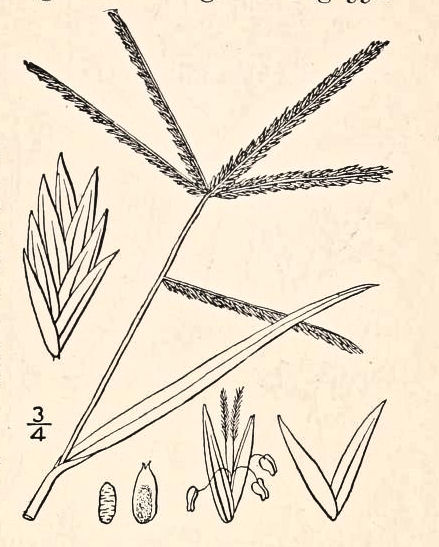

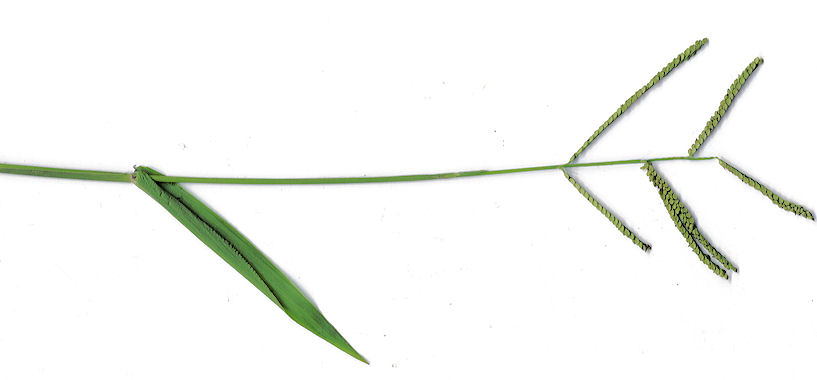

Abb.: पटोलः । Trichosanthes dioica Roxb. - Pointed Gourd

[Bildquelle: Kirtikar-Basu, ©1918]

"Trichosanthes dioeca. Roxb.

[...]

Sans. Putulika.

This is by far the most useful species of Trichosanthes I am yet acquainted with. It is much cultivated by the natives about Calcutta, during the rains. It is unknown on the coast of Coromandel.

[...]

The unripe fruit and tender tops are much eaten both by Europeans and natives in their curries, and are reckoned exceedingly wholesome.

Trichosanthes cucumerina. Willd. iv. 600.

[...]

Pada valam. Rheed. Mal. viii. t. 15.

A pretty extensive, climbing annual, a native of hedges,

&c. where it has shelter. It flowers during the cold season.

[...]

The unripe fruit is eaten in stews, by the natives, it is exceedingly bitter, for which it is reckoned the more wholesome, and is said to be anthelmintic."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 702f.]

"Trichosanthes cucumerina (Linn.) N. O. Cucurbitaceae. [...]

Description.—Annual, climbing; [...] flowers small, white.

Fl. Aug.—Dec.

W.& A. Prod. i. 350.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii. 702.—Rheede, Mal. viii. t. 15.

Peninsula. Bengal

Medical Uses.—The seeds are reputed good in disorders of the stomach on the Malabar coast. The unripe fruit is very bitter, but is eaten by the natives in their curries. The tender shoots and dried capsules are very bitter and aperient, and are reckoned among the laxative medicines by the Hindoos. They are used in infusion. In decoction with sugar they are given to assist digestion. The seeds are anti-febrile and anthelmintic. The juice of the leaves expressed is emetic, and that of the root drank in the quantity of 2 oz. for a dose is very purgative. The stalk in decoction is expectorant.

One species, the T. cordata (Roxb.), is found on the banks of the Megna, where the inhabitants use the root as a substitute for Columba- root It has been sent to England as the real Columba of Mozambique.—(Ainslie. Rheede. Roxb.) The T. dioica (Roxb.) is cultivated as an article of food. An alcoholic extract of the unripe fruit is described as a powerful and safe cathartic, in doses of from 3 to 5 grains, repeated every third hour as long as may be necessary. —(Beng. Disp.) The plant is a wholesome bitter, which imparts a tone to the system after protracted illness. It has also been employed as a febrifuge and tonic. The old Hindoo physicians used it in leprosy.—Pharm. of India."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

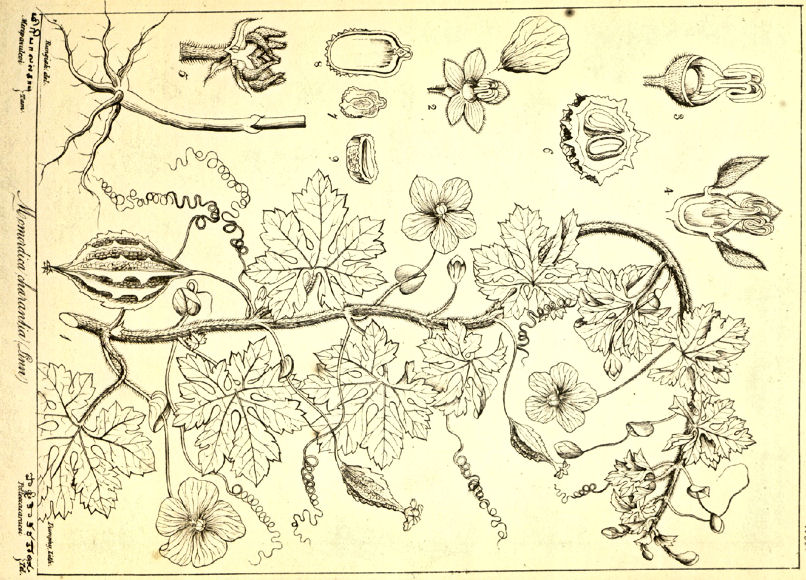

"TRICHOSANTHES DIOICA, Roxb.

Hab.—Throughout the plain of North India, Guzerat to Assam, Bengal.

TRICHOSANTHES CUCUMERINA, Linn.

Fig.—Rheede Hort. Mal. viii., t. 15.

Hab.—Throughout India and Ceylon.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—In Northern India, Bengal and Guzerat the fruit of T. diolca is considered to be the Patola of Sanskrit writers, and in Western and Southern India, where T. dioica is not found, T. cucumerina is used as Patola.

Patola or Patolaka, "shaped like a muscle shell," is a medicine in great repute amongst the Hindus as a febrifuge and laxative in bilious fevers, the decoction of the whole plant being administered in combination with other bitters. It is also considered to purify the blood and remove boils and skin eruptions; aromatics may be added to the decoction. The following prescription from Chakradatta may be taken as an example:—Take of Patola, Tinospora, Cyperus, Chiretta, Neembark, Catechu, Oldenlandia, Root bark of Adhatoda, equal parts, in all two tolas (360 grains), and prepare a decoction which is afterwards to be boiled down to one-fourth, and taken in divided doses during 24 hours. The drug is also administered in combination with Turbith as a drastic purgative in jaundice and dropsy ; the Patoladya churna is a compound purgative powder of this kind. Both of these plants are found in a wild and in a cultivated condition; for medicinal purposes, the wild plants are used, the cultivated fruits, though still bitter, are favourite vegetables with the Hindus and exert a mild aperient action when freely eaten.

Mahometan writers describe the plant as cardiacal, tonic, alterative and antifebrile, and say that it is a useful medicine for boils and intestinal worms. The author of the Makhzan remarks that the Hindus in obstinate cases of fever infuse 180 grains of the plant with an equal quantity of Coriander for a night, and in the morning add honey to it and strain the liquor; this quantity makes two doses, one of which is taken in the morning and one at night. ln the Concan the leaf juice is rubbed over the liver or even the whole body in remittent fevers. In Guzerat the fruit of the cultivated T. dioica is steamed, stuffed with spices, fried in melted butter, and eaten with wheaten bread as a remedy for spermatorrhoea. Ainslie, under the name of T. laciniosa, notices the use of T. cucumerina as a stomachic and laxative medicine among the Tamools, and says it is the Patola of Southern India. Rheede gives the following account of its medicinal properties :—" Decoctum cum saccharo sumptum, digestioni confert, tormina intestinorum, ac alios ventris dolores sedat, phlegmata expectorat, pectoris angustiam tollit; febres minuit, humores attemperat, vermes enecat. Succus expressus idem praestat et vomitum provocat. Radicis succus ad quantitatem duarum unciarum epotus, valde purgativns est, in ipsa accessione februm quotidianarum ac quartanarum ex pituita provenientium, frigus vel diminuit vel in totum tollit, per vomitum scilicet: stipes in decocto datus phlegmati expectorando conducit: fructus quaquo modo sumpti tumores expellunt."

From our observation of the action of these plants we cannot find that they differ in any way from colocynth ; like that drug they require to be combined with aromatics to prevent griping. Their febrifuge action appears to depend upon their purgative properties."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 72ff.]

Trichosanthes cucumerina L. 1753 - Schlangenhaargurke

Abb.: Trichosanthes cucumerina L. 1753 - Schlangenhaargurke

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VIII. Fig. 15, 1688]

Abb.: Trichosanthes cucumerina L. 1753 var. anguina

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine, v. 19 (1803), Tab. 722]

Abb.: Trichosanthes cucumerina L. 1753 - Schlangenhaargurke, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/2897859567/. -- Zugriff am

2010-12-06. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Trichosanthes cucumerina L. 1753 - Schlangenhaargurke, Kerala

[Bildquelle: Sangfroid / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Cucurbitaceae (Kürbisgewächse)

|

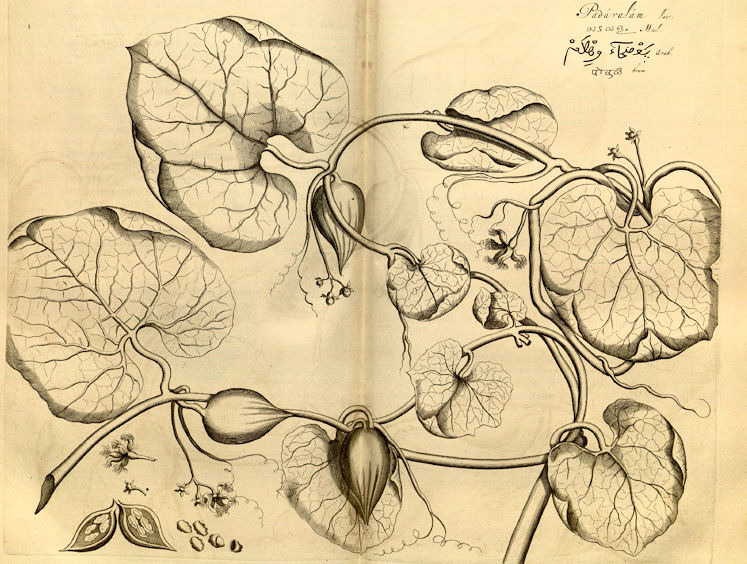

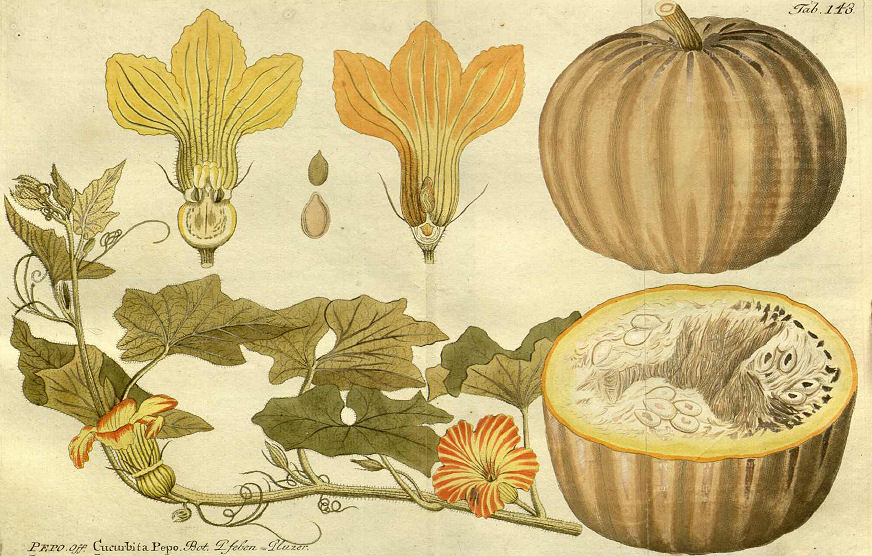

21. a./b. kūṣmāṇḍakas tu karkārur

irvāruḥ karkaṭī striyau कुष्माण्डकस् तु कर्कारुर् इर्वारुः कर्कटी स्त्रियौ ।२१ क। [Bezeichnungen für Cucurbita pepo L. 1753 - Gartenkürbis:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A pumpkin gourd. Cucurbita pepo."

1 कुष्माण्डक - kuṣmāṇḍaka m.: Kuṣmāṇḍaka

"KUSHMĀṆḌAS. 'Gourds'. A class of demigods or demons in the service of Śiva." [Quelle: Dowson, John <1820-1881>: A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history, and literature. -- London, Trübner, 1879. -- s.v. ]

Abb.:

कुष्माण्डकः

। Cucurbita pepo L. 1753 - Gartenkürbis

[Bildquelle: Icones plantarum medico-oeconomico-technologicarum

cum earum fructus ususque descriptione =Abbildungen aller

medizinisch-ökonomisch-technologischen Gewächse mit der Beschreibung ihres

Gebrauches und Nutzens. -- Wien, 1800 - 1822. -- Bd. 2, Tab. 148]

"Cucurbita Pepo. Willd. iv. 609.

[...]

Cumbulam. Rheed. Mal. viii. t. 3.

Sans. Kurkaroo.

This plant I have only found in a cultivated state.

[...]

The young unripe pomes are universally eaten by the natives in their stews, and curries."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 718f.]

"Two other plants of this natural order may be mentioned here—the Cucurbita pepo, the well-known Pumpkin, which is reputed to possess anthelmintic properties in its seeds useful in cases of Taenia. The fruit is very common in India, in which case the remedy, if really effectual, might be readily available." [Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v. Cucumis utilissimus]

Cucurbitaceae (Kürbisgewächse)

|

21. a./b.

kūṣmāṇḍakas tu karkārur

irvāruḥ karkaṭī striyau कुष्माण्डकस् तु कर्कारुर् इर्वारुः कर्कटी स्त्रियौ ।२१ क। [Bezeichnungen für Cucumis melo L. 1753 - Melone - Melon:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A sort of cucumber. Cucumis Utilatissimus [= utilissimus], Roxb. [= Cucumis melo L. 1753 - Melone - Melon]"

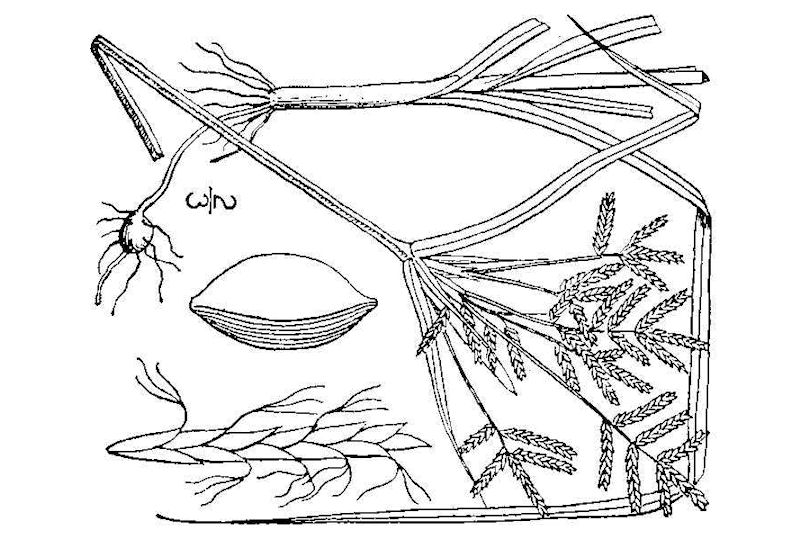

Abb.:

इर्वारुः

। Cucumis melo L. 1753 - Melone - Melon

[Bildquelle: Icones plantarum medico-oeconomico-technologicarum

cum earum fructus ususque descriptione =Abbildungen aller

medizinisch-ökonomisch-technologischen Gewächse mit der Beschreibung ihres

Gebrauches und Nutzens. -- Wien, 1800 - 1822. -- Bd. 2, Tab. 129]

Abb.: Melonenverkäufer, Chennai -

சென்னை, Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: McKay Savage. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mckaysavage/3984998318/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

"Cucumis melo. Willd. iv. C13.

[...]

Found in a cultivated state only."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 720.]

"Cucumis utilissimus. Roxb.

[...]

Fruit short-oval, smooth, variegated, of the size of a small

melon.

An annual, a native of the higher cultivated lands, but generally found in a cultivated state; the cold season is the most favourable.

[...]

This appears to me to be by far the most useful species of Cucumis that I know ; when little more than one half grown, they are oblong, and a little downy, in this state they are pickled ; when ripe they are about as large as an ostrich's egg, smooth and yellow ; when cut they have much the flavor of the melon and will keep good for several months, if carefully gathered without being bruised and hung up ; they are also in this stage eaten raw and much used in curries, by the natives.

The seeds like those ofthe other Cucurbitaceous fruits contain much farinaceous matter blended with a large portion of mild oil ; the natives dry and grind them into a meal, which they employ, as an article of diet ; they also express a mild oil from them, which they use in food and to burn in their lamps. Experience as well as analogy prove these seeds to be highly nourishing and well deserving of a more extensive culture than is bestowed on them at present. The powder of the toasted seeds mixed with sugar is said to be a powerful diuretic, and serviceable in promoting the passage of sand or gravel.

As far as my observation and information goes, this agriculture is chiefly confined to the Guntoor Circar, where these seeds form a considerable branch of commerce; they are mixed with those of Holcus Sorgum or some other of the large culmiferous tribe and sown together ; these plants run on the surface of the earth, and help to shade them from the sun, so that they mutually help each other.

The fruit I observed above keeps well for several months if carefully gathered and suspended. This circumstance will render them a very excellent article to carry to sea during long voyages."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 721f.]

"Cucumis utilissimus (Roxb.) N. O. Cucurbitaceae. Field Cucumber [...]

Description.—Trailing; [...] flowers yellow. Fl. Nearly all the year.

W. & A. Prod. i. 342.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii. 721.

Cultivated.

Economic Uses.—The fruit is pickled when half grown, and when ripe and hung up it will keep good for several months. The seeds contain much farinaceous matter mixed with a large proportion of mild oil. The meal is an article of diet with the natives, and the oil is used for lamps. Roxburgh has the following remarks upon this plant: "This appears to me to be by far the most useful species of Cucumis that I know : when little more than half grown, the fruits are oblong and a little downy—in this state they are pickled; when ripe, they are about as large as an ostrich's egg, smooth and yellow. When cut they have much the flavour of the Melon, and will keep for several months, if carefully gathered without being bruised, and hung up. They are also in this state eaten raw, and much used in curries by the natives. The seeds, like those of other Cucurbitaceous fruits, are nutritious; the natives dry and grind them into a meal, which they employ as an article of diet; they also express a bland oil from them, which they use in food and burn in their lamps. Experience as well as analogy proves these seeds to be highly nourishing, and well deserving of a more extensive culture than is bestowed on them at present. The powder of the toasted seeds mixed with sugar is said to be a powerful diuretic, and serviceable in promoting the passage of sand or gravel. As far as my observation and information go, this agriculture is chiefly confined to the Guntoor Circar, where the seeds form a considerable branch of commerce. They are mixed with those of Holcus sorghum, or some others of the large culmiferous tribe, and sown together: these plants run on the surface of the earth and help to shade them from the sun, so that they mutually help each other. The fruit, as I observed above, keeps well for several months if carefully gathered and suspended. This circumstance renders it an excellent article to carry to sea during long voyages."—(Roxb.)

The C. pseudocolocynthis found on the slopes of the Western Himalaya is a good cathartic. It is called the Himalayan Colocynth.—(Royle.)

The C. momordica is an article of diet, and a good substitute for the common Cucumber, which is also cultivated to a great extent in India.—(Roxb.)

Two other plants of this natural order may be mentioned here—the Cucurbita pepo, the well-known Pumpkin, which is reputed to possess anthelmintic properties in its seeds useful in cases of Taenia. The fruit is very common in India, in which case the remedy, if really effectual, might be readily available.

The other is the C. maxima, which would appear to possess similar properties, and to have been successfully applied in cases on record.—Pharm. of India."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

Cucurbitaceae (Kürbisgewächse)

|

21. c./d. ikṣvākuḥ kaṭutumbī syāt tumby alābūr

ubhe same इक्ष्चाकुः कटुतुम्बी स्यात् तुम्ब्य् अलाबूर् उभे समे ॥२१ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für die beiden Varietäten von Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis - Calabash:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): [21.c:] "A bittergourd. It is a variety of the next species." [21.d:] "A long gourd. Cucurbita lagenaris [= lagenaria L. 1753 = Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930]."

1 इक्ष्चाकु - ikṣvāku f.: Ikṣvāku

"IKSHWĀKU. Son of the Manu Vaivaśwat, who was son of Vivaśwat, the sun. "He was born from the nostril of the Manu as he happened to sneeze." Ikshwāku was founder of the Solar race of kings and reigned in Ayodhyā at the beginning of the second Yuga or age. He had a hundred sons, of whom the eldest was Vikukshi. Another son, named Nimi, founded the Mithilā dynasty. According to Max Müller the name is mentioned once, and only once, in the Rig-veda. Respecting this he adds : "I take it, not as the name of a king, but as the name of a people, probably the people who inhabited Bhājeratha, the country washed by the northern Gangā or Bhāgīrathī" Others place the Ikshwākus in the north-west." [Quelle: Dowson, John <1820-1881>: A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history, and literature. -- London, Trübner, 1879. -- s.v. ]

Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis - Calabash

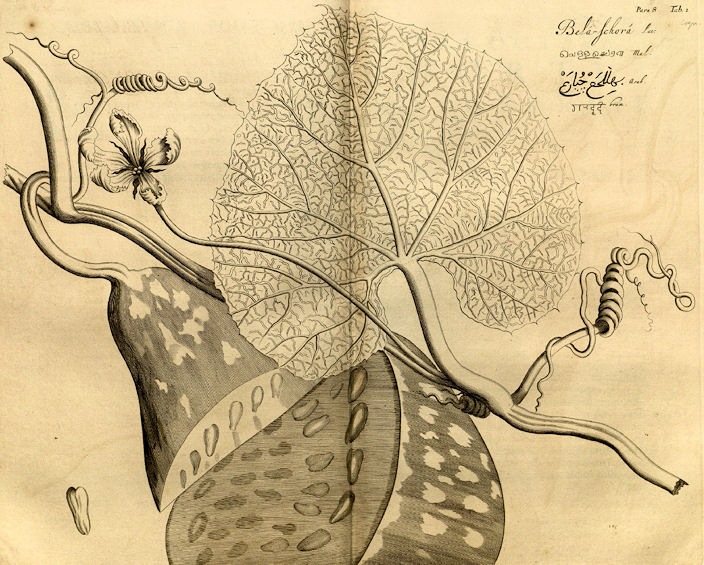

Abb.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis -

Calabash

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VIII. Fig. 1, 1688]

Abb.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis -

Calabash

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VIII. Fig. 4, 1688]

S

S

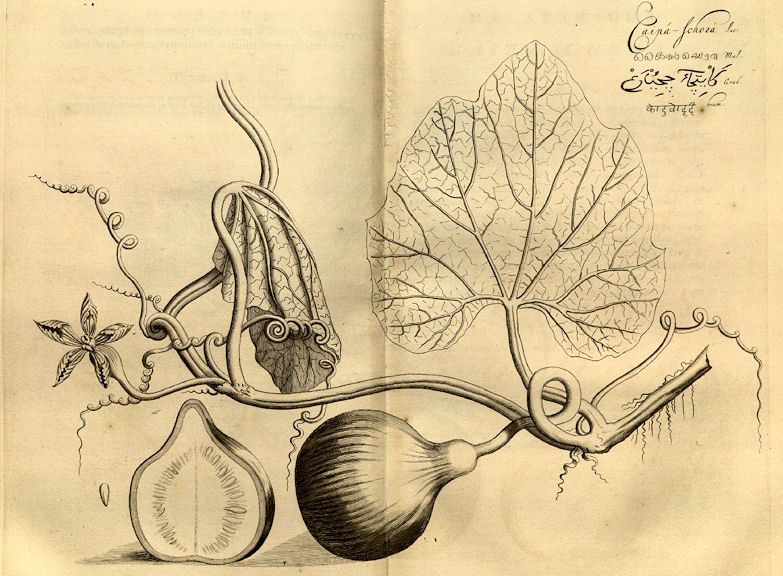

Abb.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis -

Calabash

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VIII. Fig. 5, 1688]

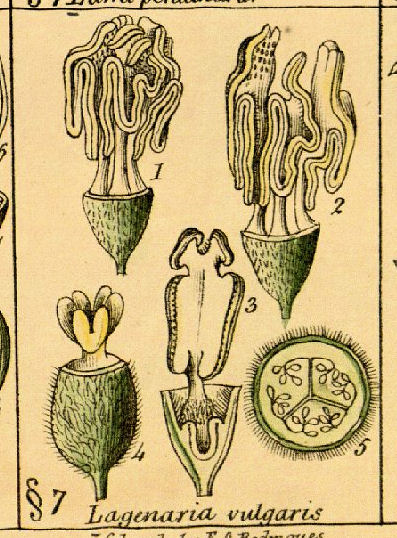

Abb.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis -

Calabash

[Bildquelle: Wight: Illustrations II, Tab. 105, 1850]

Abb.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis -

Calabash, Kyoto - 京都市,

Japan

[Bildquelle: Joel Abroad. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/40295335@N00/3795233605/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis -

Calabash

[Bildquelle: Shizhao / Wikimedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis -

Calabash, New Delhi - नई दिल्ली

[Bildquelle: Roger McLassus / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Cucurbita lagenaria. [= Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930] Willd. iv. 60G.

[...]

Bela-schora. Rheed. Mal. viii. t, 1.

Cucurbita Lagenaria. Rumph. Amb. v. t, 144. bad.

Sans. Ulava.

A wild bitter variety is called Tita Laoo, by the Bengalees and Hindoos ; and Kutoo toombee in Sanscrit.

The shape of the fruit varies much, from that of a flask to round, and cylindric."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 718.]

"Lagenaria vulgaris (Ser.) [= Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930] N. O. Cucurbitaceae. White Pumpkin. Bottle-gourd.

[...]

Descr.--Stem climbing [...] fruit bottle-shaped, yellow when ripe.

Fl. July—Sept.

W.&A. Prod. i. 341.

Cucurbita lagenaria, Linn. sp.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii. 718.—Rheede, viii t. i. 4, 5.

Cultivated.

Medical Uses.—The pulp of the fruit is often used in poultices ; it is bitter and slightly purgative, and may be used as a substitute for colocynth. A decoction of the leaves mixed with sugar is given in jaundice.

Economic Uses.—The fruit is known as the bottle-gourd. The poorer classes eat it, boiled, with vinegar, or fill the shells with rice and meat, thus making a kind of pudding of it. In Jamaica, and many other places within the tropics, the shells are used for holding water or palm-wine, and so serve as bottles. The hard shell, when dry, is used for faqueers' bottles, and a variety of it is employed in making the stringed instrument known as the Sitar, as well as buoys for swimming across rivers and transporting baggage. There is one kind, the fleshy part of which is poisonous.—Royle. Don."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"LAGENARIA VULGARIS, Seringe. [= Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930]

Fig.—Rheede Hort. Mal. viii., L 5; Wight Ill., t. 105.

The bottle gourd

Hab.—Cultivated throughout India.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—The shell of this gourd when dried is much used in the East as a vessel for holding fluids of all kinds, and for making the native guitar or Tambura. The fruit often attains an enormous size, and is used as a buoy for crossing rivers and transporting baggage. Amongst the Hindus as amongst the Greeks gourds are considered to be emblematic of fecundity, prosperity, and good health. There are two varieties of the bottle gourd, a sweet one, called in Sanskrit Alābu, and a bitter one known as Katutumbi. The fruit varies much in shape. The outer rind is hard and ligneous, and encloses a spongy white flesh, very bitter, and powerfully emetic and purgative. The seeds are grey, flat, and elliptical, surrounded by a border which is inflated at the sides but notched at the apex; their kernels are white, oily, and sweet. In India the pulp in combination with other drugs is used in native practice as a purgative; it is also applied externally as a poultice. The seeds were originally one of the four cold cucurbitaceous seeds of the ancients, but pumpkin seeds are now usually substituted for them.

The Hindus administer a decoction of the leaves in jaundice; it has a purgative action.

Toxicology.—Dr. Burton Brown notices the poisonous properties of the bitter variety of this gourd, the symptoms observed being similar to those after poisoning by elaterium or colocynth."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 67f.]

Cucurbitaceae (Kürbisgewächse)

|

22. a./b. citrā gavākṣī goḍumbā

viśālā tv indravāruṇī चित्रा गवाक्षी गोडुम्बा विशाला त्व् इन्द्रवारुणी ।२२ क। [Bezeichnungen für Cucumis maderaspatanus L. 1753:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Another sort of cucumber. Cucumis Maderaspatanus."

1 गवाक्षी - gavākṣī f.: Kuhäugige

Abb.: Rindsauge (Zebuauge), Pushkar -

पुष्कर,

Rajasthan

[Bildquelle:

Shreyans

Bhansali. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/thebigdurian/4174892287/.

-- Zugriff am 2011-01-13. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung,

keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Cucumis maderaspatanus L. 1753

Abb.: Cucumis maderaspatanus L. 1753, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1125887449/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: गवाक्षी । चित्रा

। Cucumis maderaspatanus L. 1753, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/2953317375/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: गवाक्षी । चित्रा

। Cucumis maderaspatanus L. 1753, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/2953317375/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

"Cucumis madraspatanus. Willd. iv. 615.

[...]

Till I saw Plukenet's figure of C. madraspatanus, I considered this to be the plant he meant, but now I hesitate not to say, that his is Bryonia scabrella ; however I have continued Linnaeus's specific name, although at the same time, I am in doubt whether or not this is the plant he so named. It is much like the two last described species [C. trigonis Roxb., C. turbinatus Roxb., grows in similar places, is about the same size, and in perfection at the same season, the leaves are more like those of the common cucumber, the fruit about the size of a partridge's egg, oval, downy, maculated, without any tending to be three-sided.

Note. The form of tlie fruit must be attended to, to distinguish these three last described species.

The fruit of this sort is used in food by the natives and much esteemed, yet they never take the trouble to cultivate the plant."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 723f.]

Cucurbitaceae (Kürbisgewächse)

|

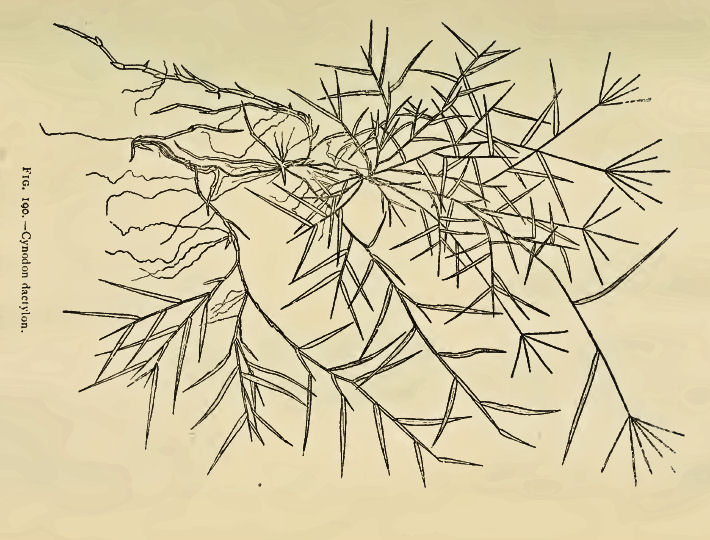

22. a./b.

citrā gavākṣī goḍumbā

viśālā tv indravāruṇī चित्रा गवाक्षी गोडुम्बा विशाला त्व् इन्द्रवारुणी ।२२ क। [Bezeichnungen für Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. 1838 - Bitter-Melone - Bitter Apple:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Coloquintida. Cucumis Colocynthis [L. 1753 = Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. 1838]."

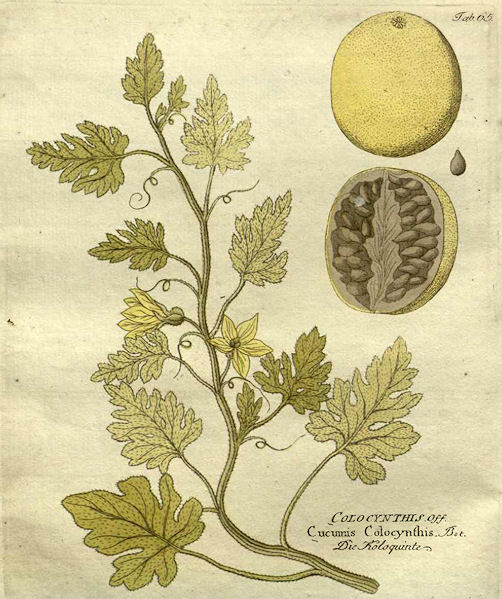

Abb.: Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. 1838 - Bitter-Melone - Bitter

Apple

[Bildquelle: Icones plantarum medico-oeconomico-technologicarum

cum earum fructus ususque descriptione =Abbildungen aller

medizinisch-ökonomisch-technologischen Gewächse mit der Beschreibung ihres

Gebrauches und Nutzens. -- Wien, 1800 - 1822. -- Bd. 1, Tab. 65]

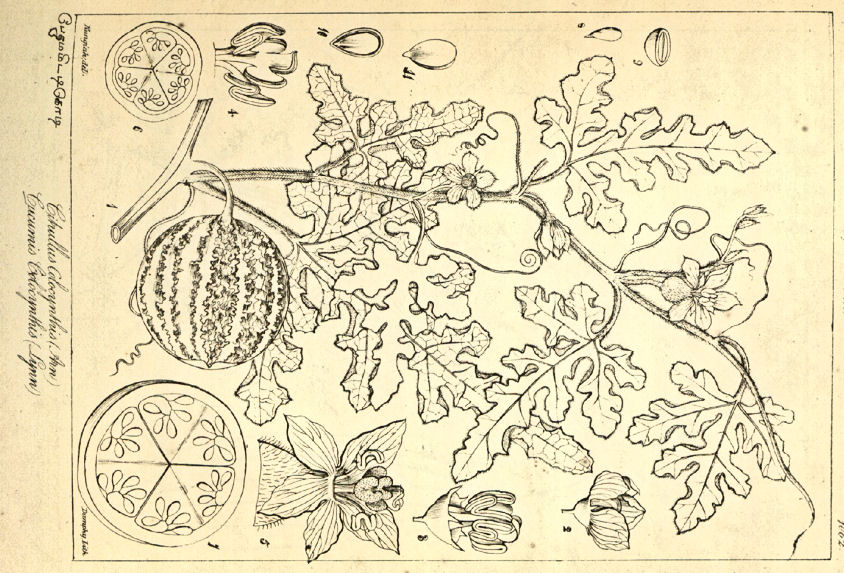

Abb.: Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. 1838 - Bitter-Melone - Bitter

Apple

[Bildquelle: Wight Icones II, Tab. 498, 1843]

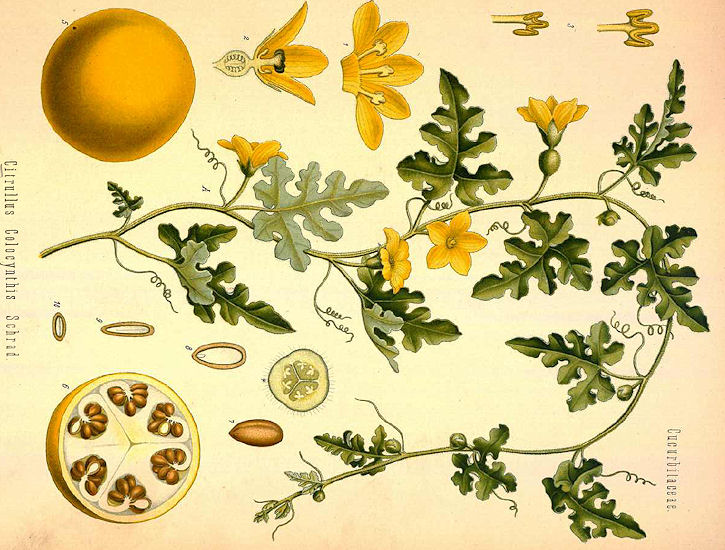

Abb.: विशाला । Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. 1838 - Bitter-Melone - Bitter

Apple

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883-1914]

Abb.: विशाला । Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. 1838 - Bitter-Melone - Bitter

Apple, Karlsruhe

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. 1838 - Bitter-Melone - Bitter

Apple, Karlsruhe

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.:

इन्द्रवारुणी

। Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad. 1838 - Bitter-Melone - Bitter

Apple, Karlsruhe

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Cucumis Colocynthis. Willd. iv. 61.

[...]

Common on the sandy lands of Coromandel."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 719f.]

"Citrullus Colocynthis (Schrad.) N. O. Cucurbitaceae.

Colocynth or Bitter Apple [...]

Description.—Annual; [...] flowers yellow.

Fl. July—September.

Cucumis colocynthis, Linn,—W. & A. Prod. i. 342.—Roxb. Fl Ind. iii. 719.— Wight Icon. t. 498.

Peninsula. Lower India in sandy plantations.

Medical Uses.—The Colocynth plant is properly a native of Turkey, but has long been naturalised in India. The medullary part of the fruit, freed from the rinds and seeds, is alone made use of in medicine. It is very bitter to the taste. The seeds are perfectly bland and highly nutritious, and constitute an important article of food in Africa, especially at the Cape of Good Hope. The extract of Colocynth is one of the most powerful and useful of cathartics. The juice of the fruit when fresh, mixed with sugar, is given in dropsy, and is externally applied to discoloration of the skin. A bitter and poisonous principle called Colocynthine resides in the fruit, the incautious use of which has frequently proved fatal. An oil is extracted from the seeds, used in lamps. Before exportation to Europe, the rind is generally removed from the fruit. In medicine its chief uses are for constipation and the removal of visceral obstructions at the commencement of fevers and other inflammatory complaints.—Ainslie. Lindley, Flor. Med.

Sheep, goats, jackals, and rats eat Colocynth apples readily, and with no bad effects. They are often used as food for horses in Scinde, cut in pieces, boiled, and exposed to the cold winter nights. They are made into preserves with sugar, having previously been pierced all over with knives, and then boiled in six or seven waters, until all the bitterness disappears. The low Gypsy castes eat the kernel of the seed, freed from the seed-skin by a slight roasting.— Stocks in Lond. Journ. Bot. iii 76."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

CITRULLUS COLOCYNTHIS, Schrad. Fig.—Wight Ic. t. 498 ; Bentl. and Trim., 114.

Bitter apple

Hab.—India, Asia, Africa. ).

History, Uses, &c.—Wild colocynth is common in waste tracts of North-West, Central and South India, and ripens in the cold season. Aitchison observes that it is very common all over the desert country of Beluchistan, where it is called Khar-kuskta. The fresh fruit is brought for sale by the herbalists; it is grown in the North-West Provinces for the use of the Government Sanitary Establishments.Sanskrit writers describe the fruit as bitter, acrid, cathartic and useful in biliousness, constipation, fever and worms. They also mention the root as a useful cathartic in jaundice, ascites, enlargements of the abdominal viscera, urinary diseases, rheumatism, &c. Sarangadhara gives a receipt for a compound pill, which contains Mercury 1 part, Colocynth pulp, Sulphur, Cardamoms, Long Pepper, Chebulic myrobalans, and Pellitory root, of each 4 parts. The Sanskrit names for colocynth are Indravāruni and Vishālā. In India the fruit or root, with or without nux vomica, is rubbed into a paste with water and applied to boils and pimples. In rheumatism equal parts of the root and long pepper are given in pills. A paste of the root is applied to the enlarged abdomen of children. (Compare with Scrib. Comp. 80, and Pliny 20, 8.)

Mahometan writers call the colocynth plant Hanzal, and discuss its properties at great length. They consider it to be a very drastic purgative, removing phlegm from all parts of the system, and direct the fruit, leaves and root to be used. The drug is prescribed as with us, when the bowels are obstinately costive from disease or lesion of the nervous centres, also in dropsy, jaundice, colic, worms, elephantiasis, &c. Its irritant action upon the uterus is noticed, and fumigation with it is said to be of use for bringing on the menstrual flow. (Compare Hippocrates de morb. mulier. ii., 50.) The author of the Makhzan describes a curious method of administration. A small hole is made at one end of the fruit and pepper-corns are introduced, the hole is then closed, the fruit enveloped in a coating of clay and buried in the hot ashes near the fire-place for some days; the pepper is then removed and used as a carminative aperient. A similar preparation is made with rhubarb root instead of pepper. The same author tells us that the seeds are purgative, and mentions their use for preserving the hair from taming grey, a purpose for which "bitter apples" are apparently employed in England in the present day. As regards the purgative properties of the seeds he is incorrect, for when thoroughly washed they are eaten by the Arabs in time of famine. Colocynth was familiar to the Greeks and Romans. (

κολοκυνθις, Theophr. H. P. i., 19, 22. vii., 1, 3, 6; Dios. iv., 171; Colocynthis, Plin. 20,8)Description.—The Indian fruit is nearly globular, of the size of an orange, smooth, marbled with green and yellow when fresh, yellowish-brown when dry, and contains a scanty greyish-white pulp in which a number of brown seeds are embedded. This pulp in the fresh fruit is spongy and juicy, and occupies the whole of the interior of the fruit. Peeled colocynth is unknown in the Indian market except as an import from Europe. [...] All parts of the plant are very bitter, and the dust when dry very irritating to the eyes and nostrils."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 59ff.]

Araceae (Aronstabgewächse)

|

22. c./d. arśoghnaḥ śūraṇaḥ kando

gaṇḍīras tu samaṣṭhilā अर्शोघ्नः सूरणः कन्दो गण्डीरस् तु समष्ठिला ॥२२ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 - Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "An esculent root. Arum campanulatum, Roxb. [= Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977]

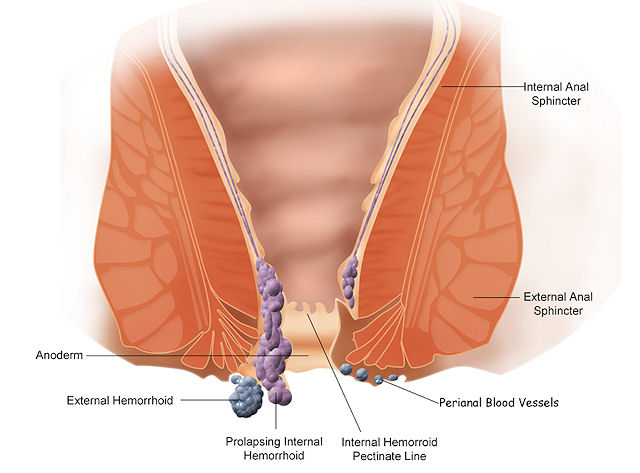

1 अर्शोघ्न - arśogna m.: Vernichter von Hämorrhoiden

Abb.: अर्शः । Hämorrhoiden

[Bildquelle: WikipedianProlific /

Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 - Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam

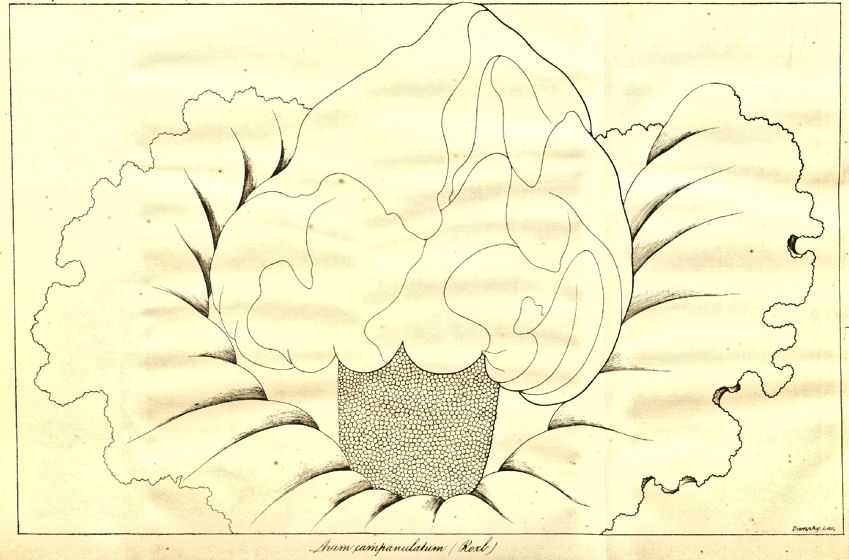

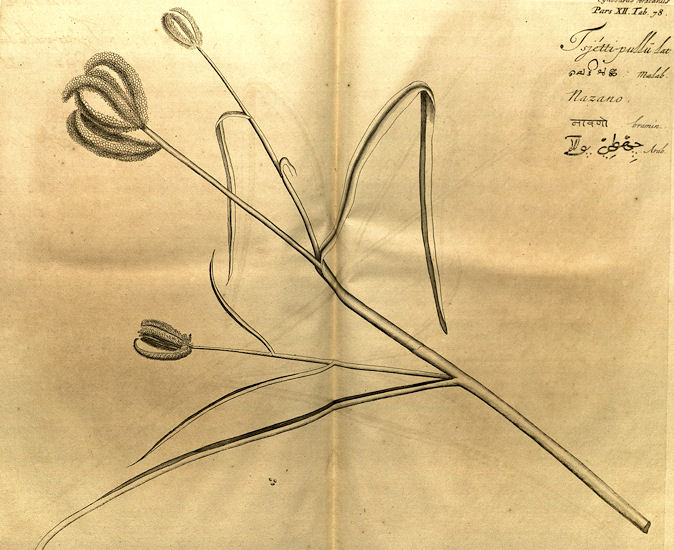

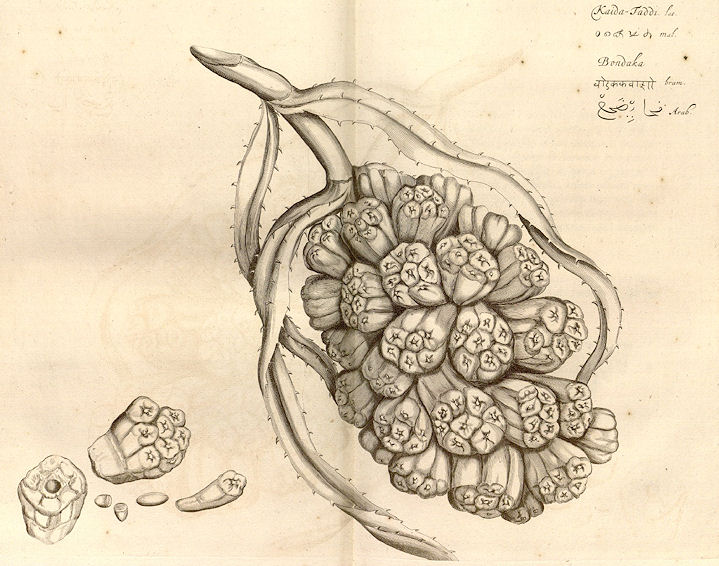

Abb.: कन्दः । Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 -

Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus XI. Fig. 18, 1692]

Abb.: Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 -

Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus XI. Fig. 19, 1692]

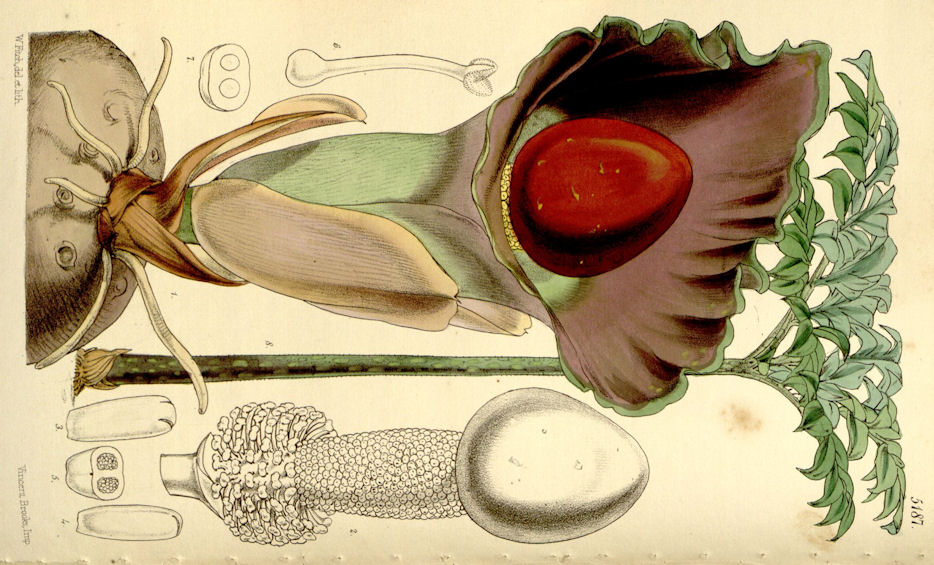

Abb.: Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 -

Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam

[Bildquelle: Wight Icones III, Tab. 782, 1846]

Abb.: Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 -

Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam

[Bildquelle: Roxburgh. -- Vol III. -- 1819. -- Tab. 272. -- Image courtesy

Missouri Botanical Garden.

http://www.botanicus.org. --

Creative Commons Lizenz

(Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 -

Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine 1860 / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 -

Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam

[Bildquelle: Kurt Stueber / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: शूरणः । Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 -

Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam, Singapur

[Bildquelle: Ria Tan. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/wildsingapore/3015632246/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 -

Elefantenkartoffel - Elephant Yam

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1355525323/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

"Arum campanulatum. Roxb. [= Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977]

Stemless. [...]

Sans, Kunda or Kulla.

Tacca sativa, Rumph. Amb. v. p. 324. t. 112, the root and leaf, and Tacca phallifera, t. 113. f. 2. the flower, at which period not a leaf is to be found.

Schena and Mulen-Schena. Rheed. Mal. p. 11 .t. 18, and 19.

Found wild in damp places in the woods near Calcutta;

flowering time the beoinnino- of the rains.

Root perennial, tuberous, roundish, covered with a dark

brown skin, frequently, when in a good soil, as large as a

child's head ; from various parts of the chief root, there issue

small tuberosities, which are employed as offsets, to cultivate

the plant by.

[...] openings at the apex, at which to discharge the disk or pollen ; the immense quantity thereof that spews out from these openings and drops down in the pistils, is really inconceivable.

[...]

This species is much cultivated in the Northern Circars, and highly esteemed for the wholesomeness, and nourishing quality of the roots. It deserves to be called the Telinga potato. The usual time of cultivation is immediately after the first rains, in June. A very rich loose soil suits it best ; where the swelling of the root meets with little obstruction, and where they draw the greatest nourishment, for which reason it requires to be very well, and repeatedly ploughed. The small tuberosities that are found in the larger roots, are what they employ for sets, and are planted in the manner potatoes are in England, and about the same distance from one another. In twelve months they are reckoned fit to be taken up for use. The larger roots will then weigh, if the soil has been good, and the season favourable, from four to eight or more pounds each, they keep well if they are kept dry, and are by the natives employed as food, in the same manner as the common yam."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 3, S. 509f.]

"Amorphophallus campanulatus (Blume). N. O. Araceae.

[...]

Description.—Stemless; [...]

Fl. June.

Wight Icon. t. 782.

Arum campanulatum, Roxb.—Rheede, Mal. xi. t. 18,19.

BengaL Peninsula.

Medical Uses.—The acrid roots are used medicinally in boils and ophthalmia. They are very caustic and abound in starch, and are employed as external stimulants, and are also emmenagogue.—(Lindley.) The fresh roots act as an acrid stimulant and expectorant, and are used in acute rheumatism.—Powell, Punj. Prod.

Economic Uses. —The roots are very nutritious, on which account they are much cultivated for the purpose of diet They are planted in May, and will yield from 100 to 250 maunds per beegah, selling at the rate of a rupee a maund. The roots are also used for pickling. Wight says that "when in flower the fetor it exhales is most overpowering, and so perfectly resembles that of carrion as to induce flies to cover the club of the spadix with their eggs." A very rich soil, repeatedly ploughed, suits it best. The small tuberosities found in the large roots are employed for sets, and planted in the manner of potatoes. In twelve months they are reckoned fit to be taken up for use; the larger roots will then weigh from 4-8 or more pounds, and keep well if preserved dry. The natives employ them for food in the manner of the common yam. The plant is the Chaneh or Mullum chanek of Rheede.—Jury Rep. M. E. Roxb."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"AMORPHOPHALLUS CAMPANULATUS, Blume

Fig.—Roxb. Cor. Pl. iii., t. 272 ; Bot. Mag,, t. 2812 ; Wight Ic., 785.

Hab.—India. Much cultivated.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—This arum occurs as a wild plant on the banks of streams and also in several cultivated forms. It is the Surana and Olla of Sanskrit writers, and among other synonyms bears that of Arsoghna or "destroyer of piles." For medicinal use, Sarangadhara directs the tuber to be covered with a layer of earth, roasted in hot ashes, and administered with the addition of oil and salt. Several confections are also used, such as the Laghuouramamodaka, Vrihat surana modaka, &c.; these are made of the tubers of the plant with the addition of treacle, aromatics (ginger and pepper) and Plumbago root, and are given in doses of about 200 grains once a day in piles and dyspepsia.

The dried tubers of the wild plant, peeled and cut into segments, are sold in the shops under the name of Madam-mast. The segments are usually threaded upon a string, and are about as large as those of an orange, of a reddish-brown colour, shrunken and wrinkled, brittle and hard in dry weather; the surface is mammillated. When soaked in water they swell up and become very soft and friable, developing a sickly smell. A microscopic examination shows that the root is almost entirely composed of starch. Madan-mast has a mucilaginous taste, and is faintly bitter and acrid; it is supposed to have restorative powers, and is in much request; it is fried in ghi with spices and sugar. It is interesting to note that the tubers of the greater Dracontia (Diosc, ii., 155) were preserved by the Greeks in the same manner for medicinal use. The cultivated plant is largely used as a vegetable ; under cultivation it loses much of its acridity and grows to an enormous size.

Synantheria sylvatica, Schott, is regarded by the Hindus as a kind of wild Surana, and, with the wild form of Amorphophallus campanulatus bears the Sanskrit name of Vajra-kanda "thunder-bolt." The country-people use the crushed seed to cure toothache; a small quantity is placed in the hollow tooth and covered with cotton; it rapidly benumbs the nerve; they also use it as an external application to bruises on account of its benumbing effect. In the Concan the seeds rubbed into a paste with water are applied repeatedly to remove glandular enlargements. The fruit is yellow, about the shape and size of a grain of maize, closely set round the upper part of the spike, which is several feet in height, and as large as that of the plantain. [...] The taste is intensely acrid, after a few seconds it causes a most painful burning of the tongue and lips, which lasts for a long time, causing much salivation and subsequent numbness. [...]

The tubers of Sanromatum pedatum, Schott., are very acrid, and are used externally under the names of Bhasamkand and Lot as a stimulating poultice. The plant is extremely common, and its pedate leaves appear with the first rain in June. The flower, which is produced just before the rains, seldom attracts notice, being more or less buried in the soil. The tubers are about as large as small potatoes, and of the same shape as those of the Surana."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 546f.]

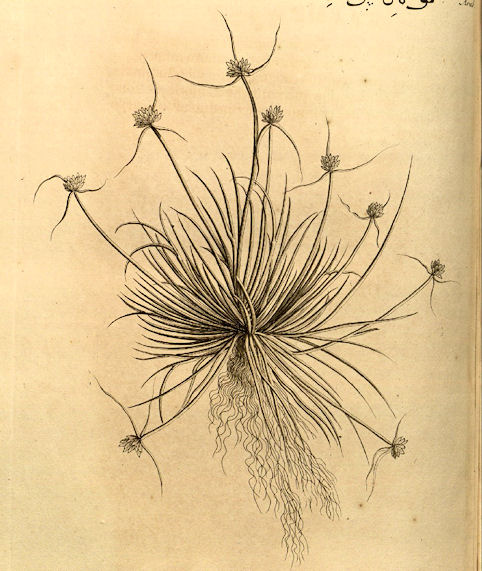

Synantherias sylvatica (Roxb.) Schott 1858

Abb.: Synantherias sylvatica (Roxb.) Schott 1858

[Bildquelle: Wight Icones III, Tab. 802, 1846]

|

22. c./d.

arśoghnaḥ sūraṇaḥ kando

gaṇḍīras tu samaṣṭhilā अर्शोघ्नः सूरणः कन्दो गण्डीरस् तु समष्ठिला ॥२२ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für ???:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A potherb. Described as growing on watery ground."

Convolvulaceae (Windengewächse)

|

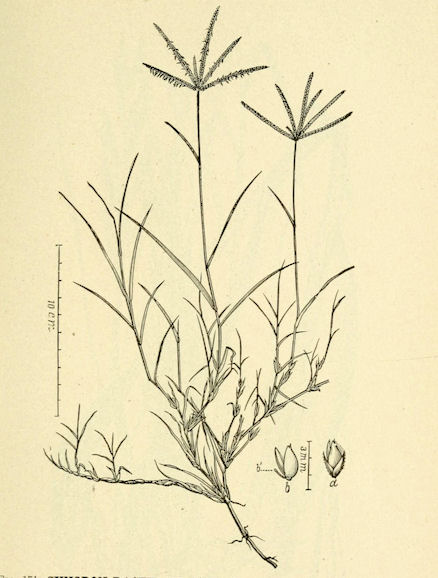

23. a./b. kalamby

upodikāstrī tu mūlakaṃ

hilamocikā कलम्ब्य् उपोदिकास्त्री तु मूलकं हिलमोचिका ।२३ क। कलम्बी - kalambī f.: Kalambī = Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. 1775 - Wasserspinat - Water Spinach |

Colebrooke (1807): [23.a-c:] "Various sorts of potherbs. Severally named in the text."

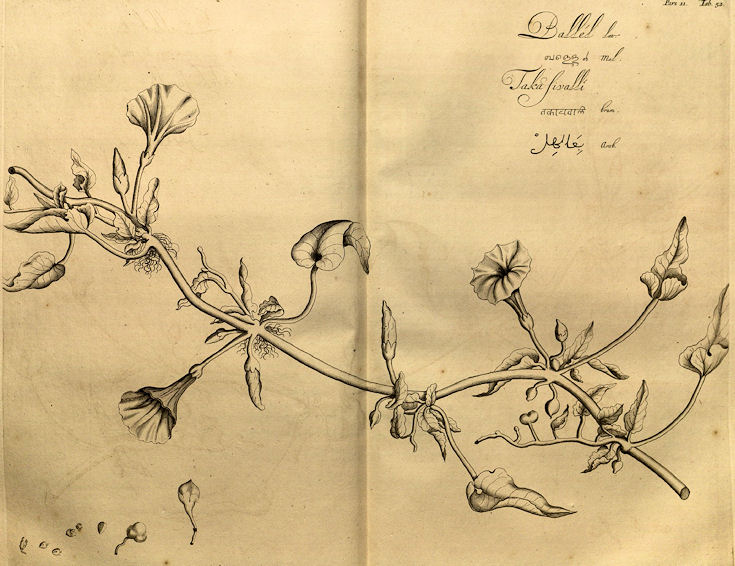

Abb.: कलम्बी । Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. 1775 - Wasserspinat - Water Spinach

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus XI. Fig. 52, 1692]

Abb.: कलम्बी । Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. 1775 - Wasserspinat - Water Spinach

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas, 1880 / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: कलम्बी । Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. 1775 - Wasserspinat - Water Spinach,

Hyderabad -

హైదరాబాద్ -

حیدرآباد, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: कलम्बी । Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. 1775 - Wasserspinat - Water Spinach,

Hyderabad -

హైదరాబాద్ -

حیدرآباد, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: J. M. Garg / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: कलम्बी । Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. 1775 - Wasserspinat - Water Spinach, Markt

in Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia

[Bildquelle: Eric in SF / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Ipomoea aquatica, Forsk., Rheede, Hort. Mal. xi., t. 52, is commonly used as a vegetable. It is called Kalambi m Sanskrit." [Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 540.]

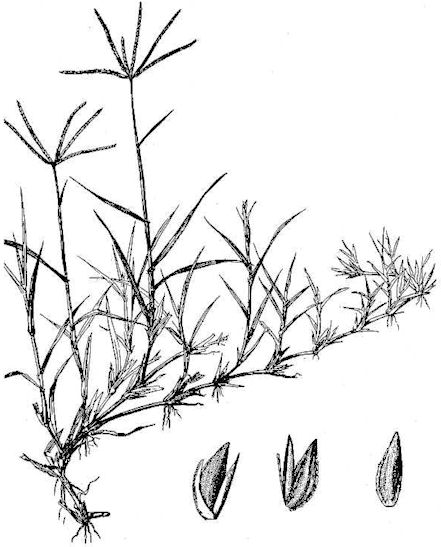

Basellaceae (Basellgewächse)

|

23. a./b.

kalamby

upodikāstrī tu mūlakaṃ hilamocikā कलम्ब्य् उपोदिकास्त्री तु मूलकं हिलमोचिका ।२३ क। उपोदिका - upodikā f.: Upodikā = Basella alba L. 1753 - Indischer Spinat - Indian Spinach |

Colebrooke (1807): siehe zum Vorherigen.

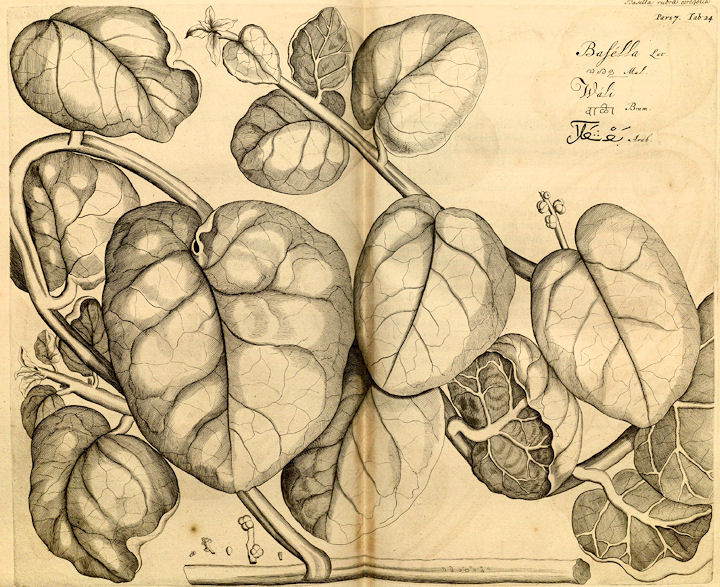

Abb.:

उपोदिका । Basella alba L. 1753 - Indischer Spinat - Indian Spinach

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VII. Fig. 24, 1686]

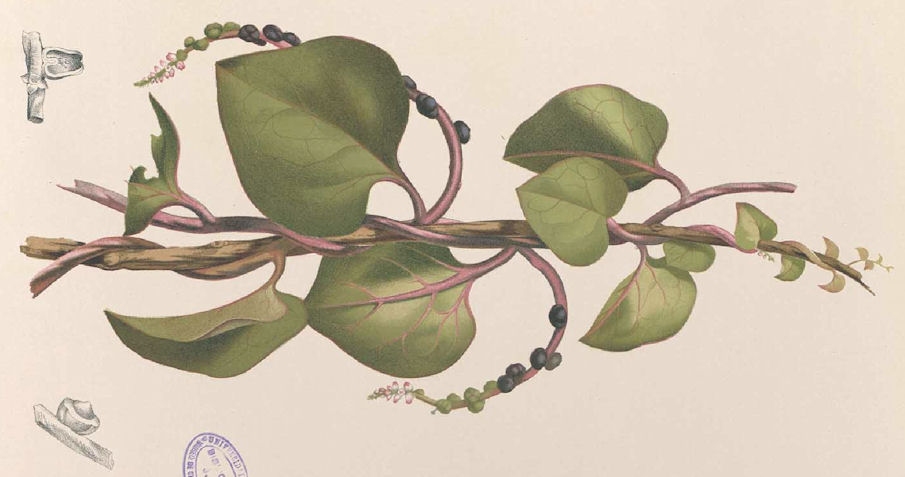

Abb.:

उपोदिका । Basella alba L. 1753 - Indischer Spinat - Indian Spinach

[Bildquelle: Flora de Filipinas, 1880 / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.:

उपोदिका । Basella alba L. 1753 - Indischer Spinat - Indian Spinach,

Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/3126360851/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-24. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.:

उपोदिका । Basella alba L. 1753 - Indischer Spinat - Indian Spinach

[Bildquelle: Shizhao / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.:

उपोदिका । Basella alba L. 1753 - Indischer Spinat - Indian Spinach

[Bildquelle: Shizhao / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Basella alba. Willd. 1. 1514.

Perennial, twining.

[...]

Gandola alba. Rumph. amb. 5. p. 417.

The natives of the Coromandel coast reckon five varieties of this ; three of these are cultivated, and two wild ;

the wild sorts are,

Yerra, or Poha-batsalla, the Telinga name of the red wild Batsalla. [...] Basella rubra. Willd. 1. 1513. Gandola rubra. Rumph. amb. 5. 417. t. 154. f. 2. bad. Is found wild in hedges, &c. twining round other plants to a considerable extent, the stems, and branches smooth, as thick as a quill, and deeply tinged red.

Alla-batsalla, above mentioned, grows with the last in hedges, and differs from it only in the colour of the stems, and branches ; here they are always pale green.

The cultivated sorts are ;

1st. Yerra, or red garden Batsalla. It differs from the wild red in being more luxuriant ; it is not much cultivated.

2nd. Mattoo, or white Garden Batsalla. [...] Like the last, it differs from the wild white only in being more luxuriant, according to the nature of the soil, and is much cultivated. The above two are generally raised from the seeds.

3d, Pedda, or large Batsalla of the Telingas. B. lucida, and cordifolia. Willd. 1. 1514. [...] Basella. Rheed. Mal. 7. t. 24. This is much cultivated, and always from slips taken from the old plants ; it grows to a great size running over extensive, trellises, erected for the purpose, and generally about the houses of the natives, where its numerous, large, succulent branchlets and leaves form a most agreeable shade to protect them from the heat of the sun. This variety is also more used as a pot herb by the natives, than any of the other four, though all are reckoned equally wholesome.

I think the whole may be reckoned varieties of one species, and probably Basella Japanica Burm. ind. t. 39. f. 4. is nothing more than from a stunted specimen of one of these varieties."

[Quelle: Roxburgh, William <1751-1815>: Flora indica, or, Descriptions of Indian plants / by the late William Roxburgh. -- Serampore : Printed for W. Thacker, 1832. -- Vol. 2, S. 104f.]

"Basella alba, Linn., Wight Ic, t. 896, is known as Indian spinach, or Malabar Nightshade, and the juice of the leaves, which is demulcent and cooling, is a popular application to allay the heat and itching of urticaria arising from dyspepsia, an affection which the Hindus consider to be indicative of bile in the blood. The boiled leaves are also used as a poultice. This herb is extensively cultivated as a vegetable, [...] The generic name is derived from the Tamil. The Sanskrit name is Potaki or Upodika."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 148.]

Brassicaceae (Kreuzblütengewächse)

|

23. a./b.

kalamby upodikāstrī tu mūlakaṃ

hilamocikā कलम्ब्य् उपोदिकास्त्री तु मूलकं हिलमोचिका ।२३ क। मूलक - mūlaka m. n.: Wurzeliger = Raphanus sativus L. 1753 - Rettich - Radish |

Colebrooke (1807): siehe zum Vorherigen.

Abb.: मूलकम् । Raphanus sativus L. 1753 - Rettich - Radish