नामलिङ्गानुशासनम्

2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam

9. siṃhādivargaḥ

(Über Tiere)

2. Vers 4c - 12b

(Säugetiere II und Warane)

Übersetzt von Alois Payer

mailto:payer@payer.de

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>:

Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2.

Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 9. siṃhādivargaḥ. --

2. Vers 4c - 12b (Säugetiere II und Warane). -- Fassung vom 2011-03-06. --

URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa2/amara209b.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-01-16

Überarbeitungen:

2011-03-06 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright:

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share

alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung

Sanskrit

von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund

Prof. Dr. Heinrich von

Stietencron

ist die gesamte

Amarakośa-Übersetzung

in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

|

Meiner lieben Frau

Margarete Payer

die all meine Interessen teilt und fördert

ist das Tierkapitel in

Dankbarkeit besonders gewidmet |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie

eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

|

"Those who have never considered the subject are

little aware how much the appearance and habit of a plant become

altered by the influence of its position. It requires much

observation to speak authoritatively on the distinction in point of

stature between many trees and shrubs. Shrubs in the low country,

small and stunted in growth, become handsome and goodly trees on

higher lands, and to an inexperienced eye they appear to be

different plants. The Jatropha curcas grows to a tree some 15

or 20 feet on the Neilgherries, while the Datura alba is

three or four times the size in>n the hills that it is on the

plains. It is therefore with much diffidence that I have

occasionally presumed to insert the height of a tree or shrub. The

same remark may be applied to flowers and the flowering seasons,

especially the latter. I have seen the Lagerstroemia Reginae,

whose proper time of flowering is March and April, previous to the

commencement of the rains, in blossom more or less all the year in

gardens in Travancore. I have endeavoured to give the real or

natural flowering seasons, in contradistinction to the chance ones,

but, I am afraid, with little success; and it should be recollected

that to aim at precision in such a part of the description of plants

is almost hopeless, without that prolonged study of their local

habits for which a lifetime would scarcely suffice."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful

plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and

the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi,

512 p. ; 22 cm. -- S. VIII f.] |

2. dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam - Zweiter

Teil

2.9. siṃhādivargaḥ - Abschnitt über

Löwen und andere Tiere

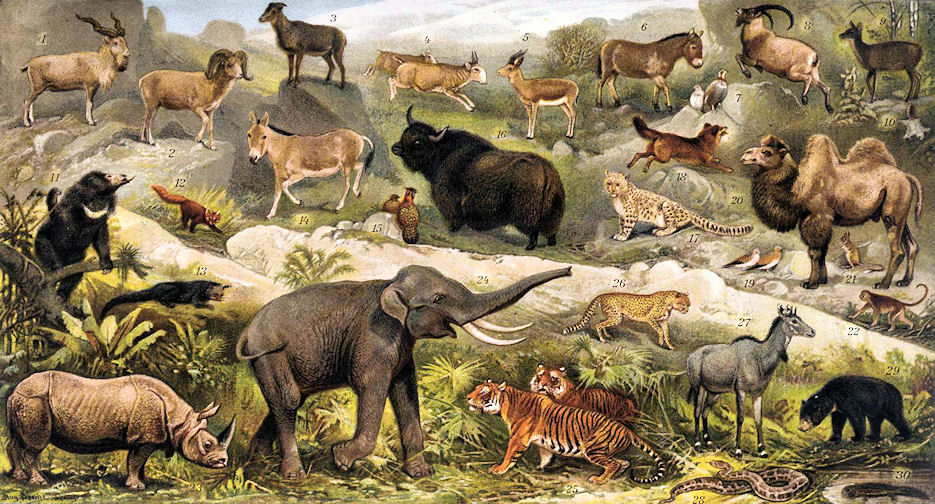

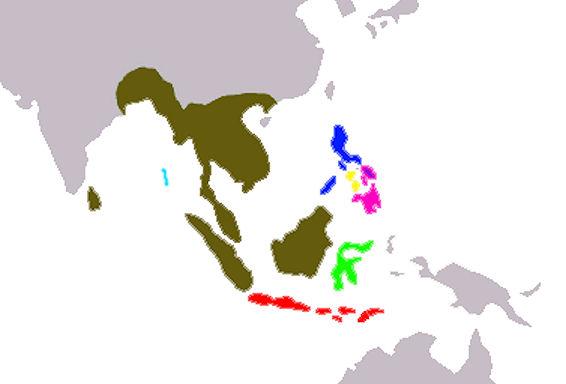

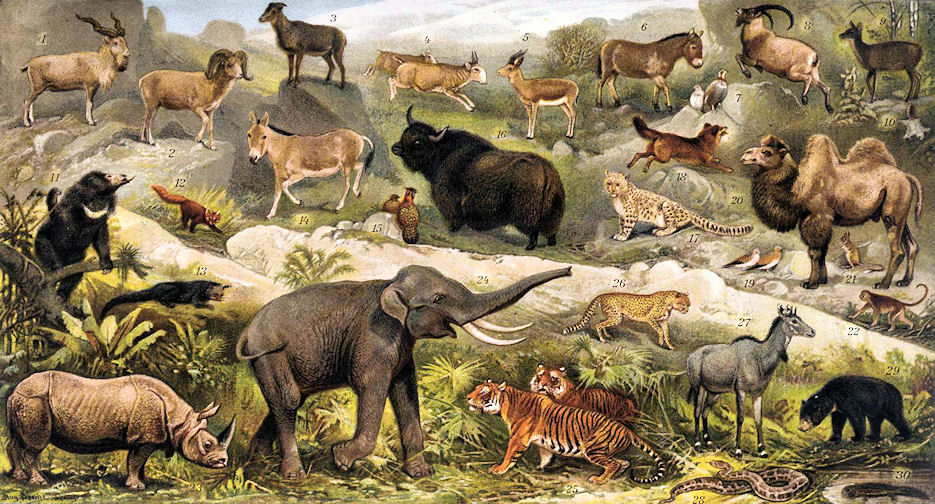

Abb.: Asiatische Tierwelt

[Bildquelle: Brockhaus' Kleines Konversationslexikon, 1906]

Referenzwerke:

Mammal species of the world : a taxonomic and

geographic reference / ed. by Don E. Wilson and DeeAnn M. Reeder. -- 3. ed.

-- Baltimore : John Hopkins Univ. Pr., 2005. -- 2 Bde. : 2142 S. -- ISBN

0-8o18-8221-4 [Normierend für lateinische und englische Säugetiernamen]

Menon, Vivek:

Mammals of India. -- New Jersey : Princeton UP, ©2009. -- 201 S. : Ill. --

ISBN 978-0-691-14067-4 [Sehr gute Übersicht über die wichtigsten Säugetiere

Indiens]

Walker's mammals of the world

/ Ronald M. Nowak; John L. Paradiso. - Baltimore, Md. [u.a.] : Johns Hopkins

Univ. Pr., 1999. -- 2 Bde. -- ISBN 0-8018-3970-X [Referenzwerk für

Säugetiere]

Übersicht

- 2.9.9. Bubalus bubalis arnee Kerr, 1792. - Wilder

Wasserbüffel -

Wild Water Buffalo

- 2.9.9.1. Domestizierter Wasserbüffel

- 2.9.9.2. Mahiṣāsuramardinī

- 2.9.10. Canis aureus indicus Hodgson, 1833 -

Indischer Goldschakal - Indian Golden Jackal

- 2.9.11. Wildkatzen und Hauskatze

- 2.9.12. Varanus sp. - Warane - Monitor lizards

- 2.9.13. Stachelschweine

- 2.9.13.1. Stachelschweinborsten

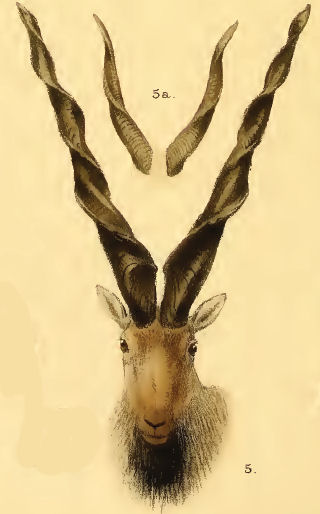

- 2.9.14. Eine schnelle Antilopenart

- 2.9.15. Canis lupus pallipes

Sykes, 1831 -

Indischer Wolf - Indian Wolf

- 2.9.16. Antilopen und Gazellen

- 2.9.17. Adjektivbildung zur Eṇa-Antilope

- 2.9.18. Fell-Lieferanten

- 2.9.19. Verschiedenerlei Wild

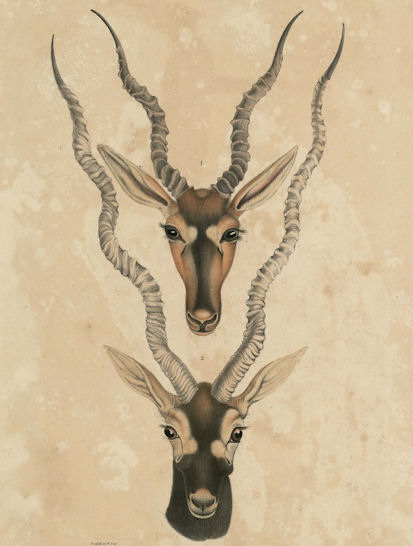

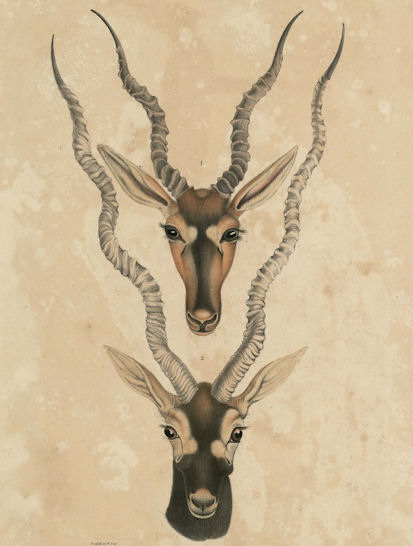

- 2.9.19.1. कृष्णसार - kṛṣṇasāra m.: Schwarzscheckiger, schwarzscheckige

Antilope (Moschiola indica Gray, 1843 - Indian Spotted Chevrotain +

Moschiola meminna Erxleben,

1777 ?)

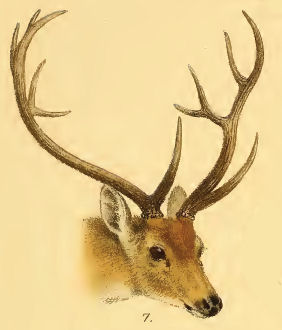

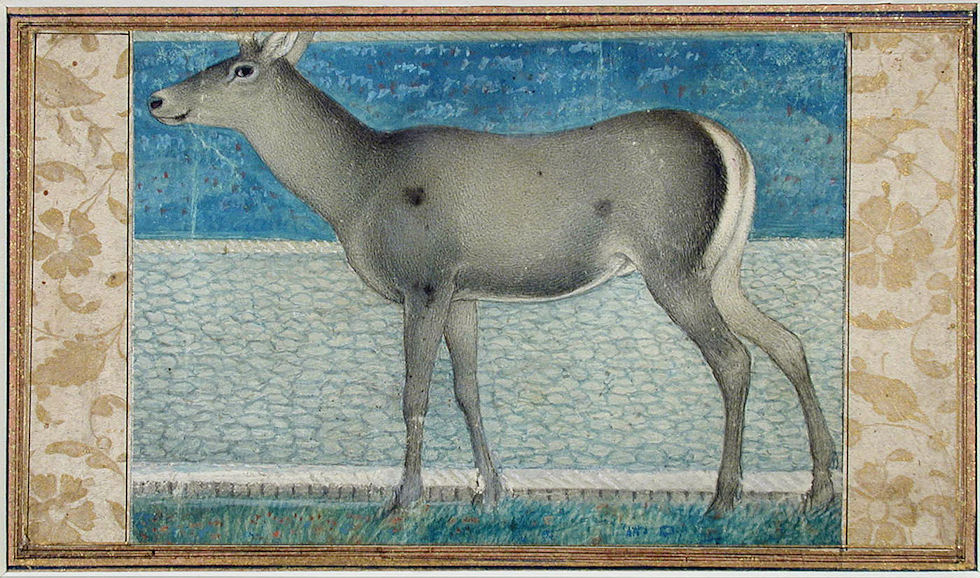

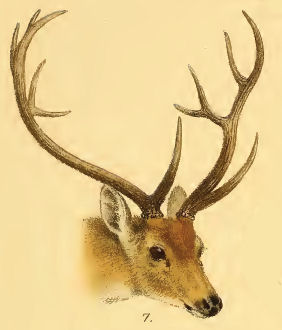

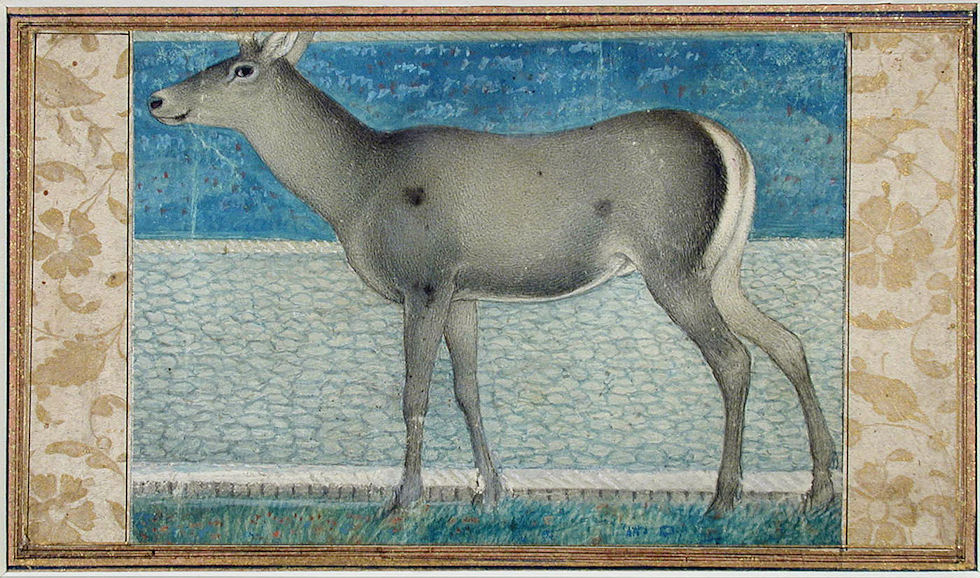

- 2.9.19.2. रुरु - ruru m.:

Rucervus duvaucelii G.

Cuvier, 1823 - Barasingha / Zackenhirsch - Barasingha (Swamp Deer)

- 2.9.19.3. न्यङ्कु - nyaṅku m.:

Axis porcinus Zimmermann, 1780 - Schweinshirsch - Hog Deer

- 2.9.19.4. रङ्कु - raṅku m.: Raṅku

- 2.9.19.5. शम्बर - śambara m.:

Rusa unicolor Kerr, 1792 - Sambar

- 2.9.19.6. रौहिष - rauhiṣa m.: Rauhiṣa

- 2.9.19.7. गोकर्ण - gokarṇa m.: "Kuhohr"

- 2.9.19.8. पृषत - pṛṣata m.: Gesprenkelter =

Axis axis Erxleben, 1777 - Axishirsch - Chital

- 2.9.19.9. एण - eṇa m.:

vielleicht = Moschiola indica Gray, 1843 - Indian Spotted Chevrotain (Mouse Deer)

- 2.9.19.10. ऋश्य - ṛśya m.:

Moschus leucogaster Hodgson, 1839 - Himalaya-Moschushirsch -

Himalayan Musk Deer

- 2.9.19.11. रोहित - rohita m.: Roter

- 2.9.19.12. चमर - camara m.:

Bos grunniens Przewalski, 1883 - Yak - གཡག་ (männl.) / འབྲི (weibl.)

- 2.9.19.13. Wild, für das ich keine eindeutige Zuordnung zu

obigen Sanskritbezeichnungen machen konnte

- 2.9.19.13.1. Hirsche, Moschushirsche, Hirschferkel

- 2.9.19.13.2. Wildziegen, Wildschafe, Ziegenantilopen

- 2.9.20 Gandharva

- 2.9.21. Śarabha

- 2.9.22. राम - rāma m.: Boselaphus tragocamelus Pallas, 1766 - Nilgauantilope - Nilgai

- 2.9.23. सृमर - sṛmara m.: Ein großes Wildschwein (Sus scrofa

var.)

- 2.9.24. Bos frontalis Lambert, 1804 - Gaur

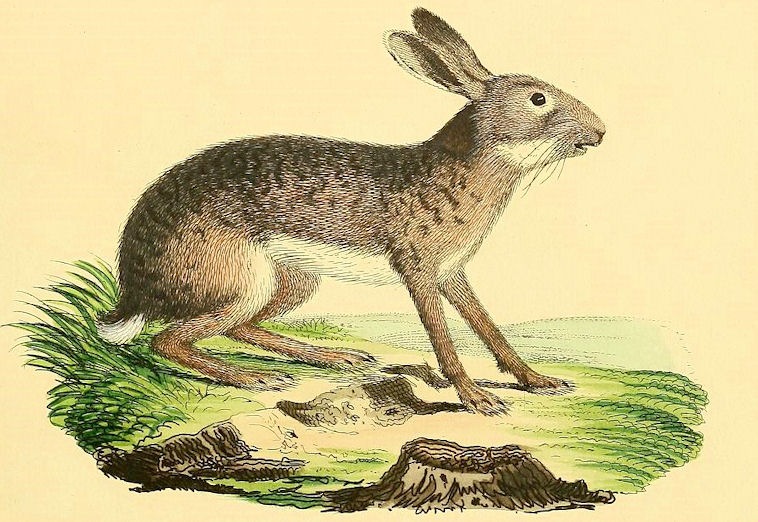

- 2.9.25. Hasen und Kaninchen

- 2.9.25.1. Der Hase im Mond

- 2.9.26. Vieh

- 2.9.26.1. Paśupati, der Herr der Tiere

- 2.9.27. Ratten und Mäuse

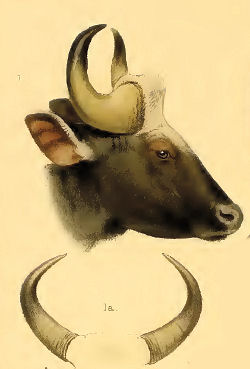

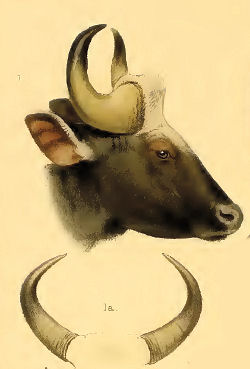

2.9.9. Bubalus bubalis arnee Kerr, 1792. - Wilder Wasserbüffel -

Wild Water Buffalo

|

4.c./d. lulāyo mahiṣo vāhādviṣat-kāsara-sairibhāḥ

लुलायो महिषो वाहाद्विषत्-कासर-सैरिभाः ॥४ ख॥

[Bezeichnungen für Bubalus bubalis arnee Kerr, 1792. - Wilder Wasserbüffel -

Wild Water Buffalo:]

-

लुलाय -

lulāya m.: Wasserbüffel

- महिष -

mahiṣa m.: Gewaltiger, Wasserbüffel

- वाहाद्विषत्

- vāhādviṣat m.: der kein Feind des Zugtier(seins) ist, der

kein Feind des Wagens ist

- कासर -

kāsara m.: Kāsara

- सैरिभ

- sairibha m.: Pflug-Elefant

|

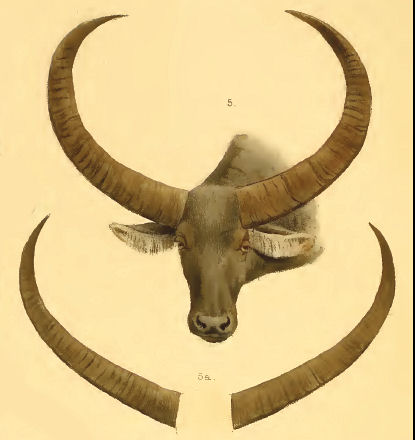

Colebrooke (1807): "A buffalo."

Eines der für den Menschen gefährlichsten Tiere. Paart sich mit

domestizierten Wasserbüffeln.

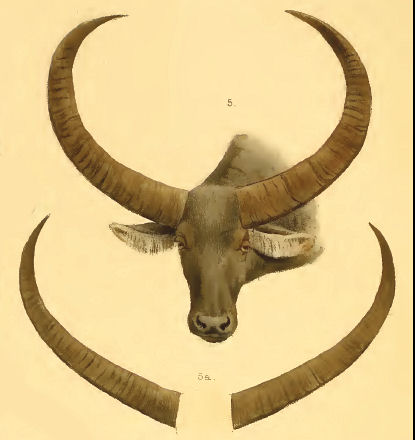

Kommt mit zwei verschiedenen Hornformen vor (siehe Abb.)

Schulterhöhe: 155 - 180 cm

Gewicht: 800 - 1200 kg

Lebensraum: früher ganz Indien, heute in der Wildform nur noch Assam und

Zentralindien

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: über 1200

Lebt als Einzelgänger oder in Herden von bis zu 20 Tieren

Abb.: महिषः ।

Bubalus bubalis Kerr 1792. -

Wasserbüffel - Water Buffalo

[Bildquelle: Lydekker, Richard <1849 - 1915>: The great and small

game of India, Burma, & Tibet. -- London, 1900. -- Pl. 2]

Abb.: महिषः ।

Bubalus bubalis Kerr 1792. -

Wasserbüffel - Water Buffalo

[Bildquelle: Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit

Beschreibungen von Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber ... Fortgesetzt von d.

August Goldfuss ..., 1797 - 1861. -- Tafel CCC.A]

Abb.: महिषः ।

Bubalus bubalis arnee Kerr 1792. - Wilde Wasserbüffel -

Wild Water Buffalos, Kaziranga National Park -

কাজিৰঙা ৰাষ্ট্ৰীয় উদ্যান, Assam

[Bildquelle: Janani. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jannysooria/4211604792/. -- Zugriff am

2010-12-15. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

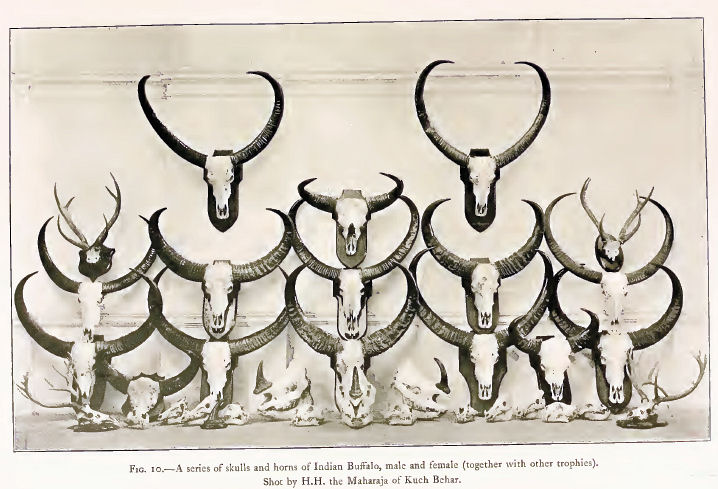

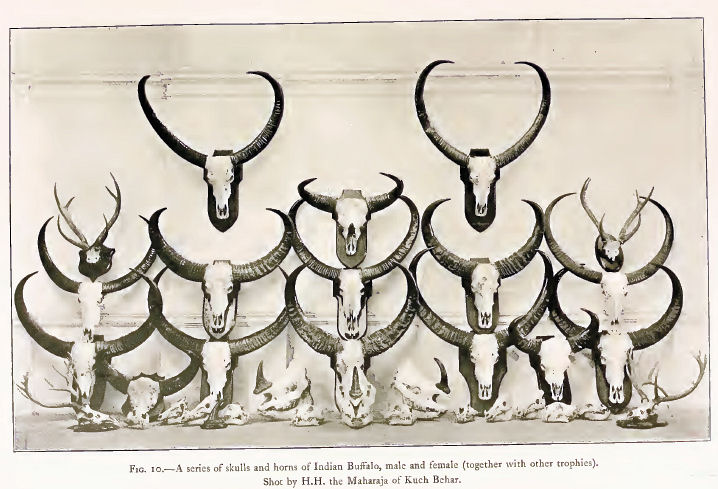

Abb.: Sammlung von Hörnern von Wilden Wasserbüffeln, die Seine Königliche Hoheit, der Maharaja von Kuch Behar (কোচবিহার)

ermordet hat

[Bildquelle: Lydekker, Richard <1849 - 1915>:

The great and small game of India, Burma, & Tibet. --

London, 1900. -- Fig. 10]

|

"The wild buffalo is found in the swampy Terai

at the foot of the hills, from Bhotan to Oude ; also, in the plains of

lower Bengal as far west as Tirhoot, but increasing in numbers to the

eastwards, on the Burrampooter, and in the Bengal Sunderbuns. It also occurs

here and there through the eastern portion of the table-land of Central

India, from Midnapore to Raepore, and thence extending south nearly to

the Godavery. South and west of this it does not, to my knowledge,

occur in India, but a few are found in the north and north-east of Ceylon.

"The Arna," says Mr. Hodgson, "inhabits the margin rather than the interior of primaeval forests. They never

ascend the mountains, and adhere, like the Rhinoceros, to the most swampy sites

of the districts they inhabit. It ruts in autumn, the female

gestating 10 months, and produces one or two young in summer. It lives in large

herds, but in the season of love, the most lusty males lead off and

appropriate several females, with which they form small herds for the time. The

bull is of such power and vigour as by his charge frequently to

prostrate a good-sized elephant. They are uniformly in high condition, so

unlike the leanness and angularity of the domestic buffalo, even at its best."

Mr. Blyth states it as his opinion that,

except in the valley of the Ganges and Burrampooter, it has been introduced and

become feral. With this view I cannot agree, and had Mr. Blyth seen

the huge buffaloes I saw on the Indrawutty river (in 1857), he would,

I think, have changed his opinion. They have hitherto not been recorded

south of Raepore, but where I saw them is nearly 200 miles south. I

doubt if they cross the Godavery river.

I have seen them repeatedly, and killed

several in the Purneah district. Here they frequent the immense tracts of long

grass abounding in dense, swampy thickets, bristling with canes and

wild roses; and in these spots, or in the long elephant-grass on the bank of jheels, the buffaloes lie during the heat of the day. They feed chiefly at

night or early in the morning, often making sad havoc in the fields, and

retire in general before the sun is high. They are by no means shy (unless

they have been much hunted), and even on an elephant, without which they

could not be successfully hunted, may often be approached within good

shooting distance. A wounded one will occasionally charge the elephant,

and as I have heard from many sportsmen will sometimes overthrow the

elephant. I have been charged by a small herd, but a shot or two as

they are advancing will usually scatter them.

Hodgson remarks that "there is no animal

upon which ages of domestication have made so small an impression as upon the

Buffalo, the tame species being still most clearly referrible

to the wild ones." He also states that the tame buffaloes when driven to the

forests to be depastured have intercourse with the wild bulls, and the

breed is thus improved. In Purneah I was informed, however, that the

wild buffalo dislike the presence of tame ones exceedingly, and will even

retire from the spot where the tame ones are feeding.

The domestic buffalo is extensively used in

India both for draught and as milch cattle, and its milk is richer than

that of the cow of India. Some of the hill races, such as those on the

Neelgherries, are very fine animals resembling the wild buffalo ; and many along

the crests of the Western Ghats, and elsewhere, are seen with white

legs like the Gaur."

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

308f.] |

2.9.9.1. Domestizierter Wasserbüffel

Abb.:

महिषः ।

Bubalus bubalis Kerr 1792. - Domestizierte

Wasserbüffel - Water Buffalo, Indien

[Bildquelle:

Brian Gratwicke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/briangratwicke/3596848274/. -- Zugriff am

2010-12-09. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: सैरिभः ।

Domestizierte Wasserbüffel als Pfluggespann, Punjab

[Bildquelle: Northampton Museum. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/northampton_museum/5043373393/. -- Zugriff am

2010-12-09. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.:

सैरिभः ।

Domestizierte Wasserbüffel als Pfluggespann, Sri Lanka

[Bildquelle:

James Manners. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jmanners/1013173792/. -- Zugriff am 2010-12-09.

-- Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: वाहाद्विषन्तौ

। Domestizierte Wasserbüffel, Vietnam

[Bildquelle:

Mark

Robertson. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/riverdaleto/111056662/. -- Zugriff am

2011-01-16. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Verbreitung der Domestizierten Wasserbüffel nach Ländern 2004 (Indien = 100% = t (India -

97.700.000)

[Bildquelle: Anwar saadat / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Siehe

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā

/ übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. --

Bubalus bubalis. -- URL:

http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/bubalus_bubalis.htm

2.9.9.2. Mahiṣāsuramardinī

Abb.: महिषासुरमर्दिनी - Mahiṣāsuramardinī: Durgā als Vernichterin

des Dämons Mahiṣāsura, 19. Jhdt

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

| "According to a narrative in the Devi Mahatmya story of the

Markandeya Purana text, Durga was created as a warrior goddess to fight an asura

(an inhuman force/demon) named Mahishasura. He had unleashed a reign of terror

on earth, heaven and the nether worlds, and he could not be defeated by any man

or god, anywhere. The gods went to Brahma, who had given Mahishasura the power

not to be defeated by a man. Brahma could do nothing. They made Brahma their

leader and went to Vaikuntha — the place where Vishnu lay on Ananta Naag. They

found both Vishnu and Shiva, and Brahma eloquently related the reign of terror

Mahishasur had unleashed on the three worlds. Hearing this Vishnu, Shiva and all

of the gods became very angry and beams of fierce light emerged from their

bodies. The blinding sea of light met at the Ashram of a priest named Katyan.

The goddess Durga took the name Katyaayani from the priest and emerged from the

sea of light. She introduced herself in the language of the Rig-Veda, saying she

was the form of the supreme Brahman who had created all the gods. Now she had

come to fight the demon to save the gods. They did not create her; it was her

lila that she emerged from their combined energy. The gods were blessed with

her compassion. It is said that upon initially encountering Durga,

Mahishasura underestimated her, thinking: "How can a woman kill me, Mahishasur —

the one who has defeated the trinity of gods?" However, Durga roared with laughter, which caused an

earthquake which made Mahishasur aware of her powers.

And the terrible Mahishasur rampaged against her, changing

forms many times. First he was a buffalo demon, and she defeated him with her

sword. Then he changed forms and became an elephant that tied up the goddess's

lion and began to pull it towards him. The goddess cut off his trunk with her

sword. The demon Mahishasur continued his terrorizing, taking the form of a lion,

and then the form of a man, but both of them were gracefully slain by Durga.

Then Mahishasur began attacking once more, starting to

take the form of a buffalo again. The patient goddess became very angry, and as

she sipped divine wine from a cup she smiled and proclaimed to Mahishasur in a

colorful tone — "Roar with delight while you still can, O illiterate demon,

because when I will kill you after drinking this, the gods themselves will roar

with delight". When Mahishasur had half emerged into his buffalo form, he

was paralyzed by the extreme light emitting from the goddess's body. The goddess

then resounded with laughter before cutting Mahishasur's head down with her

sword.

Thus Durga slew Mahishasur, thus is the power of the

fierce compassion of Durga. Hence, Mata Durga is also known as

Mahishasurmardhini — the slayer of Mahishasur. According to one legend, the

goddess Durga created an army to fight against the forces of the demon-king

Mahishasur, who was terrorizing Heaven and Earth. After ten days of fighting,

Durga and her army defeated Mahishasur and killed him. As a reward for their

service, Durga bestowed upon her army the knowledge of jewelry-making. Ever

since, the Sonara community has been involved in the jewelry profession.

The goddess, as Mahisasuramardhini, appears quite early in

Indian art. The Archaeological Museum in Matura has several statues on display

including a 6-armed Kushana period Mahisasuramardhini that depicts her pressing

down the buffalo with her lower hands.

A Nagar plaque from the first century BC - first century AD depicts a 4-armed

Mahisamardhini accompanied by a lion. But it is in the Gupta period that we see

the finest representations of Mahisasuramardhini (2-, 4-, 6-, and at Udayagiri,

12-armed). The spear and trident are her most common weapons. A Mamallapuram

relief shows the goddess with 8 arms riding her lion subduing a buffalo-faced

demon (as contrasted with a buffalo demon); a variation also seen at Ellora. In

later sculptures (post-seventh Century), sculptures show the goddess having

decapitated the buffalo demon."

[Quelle:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahishasuramardini. --

Zugriff am 2011-01-16] |

2.9.10. Canis aureus indicus Hodgson, 1833 -

Indischer Goldschakal - Indian Golden Jackal

5. striyāṃ śivā bhūrimāya-gomāyu-mṛgadhūrtakāḥ

śṛgāla-vañcaka-kroṣṭu-pheru-pherava-jambukāḥ

स्त्रियां शिवा भूरिमाय-गोमायु-मृगधूर्तकाः ।

शृगाल-वञ्चक-क्रोष्टु-फेरु-फेरव-जम्बुकाः ॥५॥

[Bezeichnungen für Canis aureus indicus Hodgson, 1833 -

Indischer Goldschakal - Indian Golden Jackal:]

-

शिवा - śivā f.: die

Gnädige, Gattin Śivas (fem. auch für Männchen!)

- भूरिमाय

- bhūrimāya m.: Täuschung auf der Erde1

- गोमायु

- gomāyu m.: wie ein Rind Brüllender

- मृगधूर्तक

- mṛgadhūrtaka m.: Wild-Betrüger

- शृगाल

- śṛgāla m.: Schakal

- वञ्चक

- vañcaka m.: Betrüger

- क्रोष्टु

- kroṣṭu m.: Schreier

- फेरु -

pheru m.: Schakal

- फेरव -

pherava m.: Schakal

- जम्बुक

- jambuka m.: Jambuka (zu jambu f.: Syzygium jambos (L.)

Alston 1931 - Rosenapfel - Malabar Plum / Rose Apple)2

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A shakal."

1 भूरिमाय

- bhūrimāya m.: Täuschung auf der Erde

|

"MĀYĀ. 'Illusion, deception.' Illusion

personified as a female form of celestial origin, created for

the purpose of beguiling some individual Sometimes identified with

Durgā as the source of spells, or as a personification of

the unreality of worldly things. In this character she is called Māyā-devī or

Mahāmāyā."

[Quelle: Dowson, John

<1820-1881>: A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and

religion, geography, history, and literature. -- London, Trübner,

1879. -- s.v. ] |

2 जम्बुक

- jambuka m.: Jambuka (zu jambu f.: Syzygium jambos (L.) Alston 1931 - Rosenapfel - Malabar Plum /

Rose Apple)

Vielleicht wegen seiner Farbe

Abb.: जम्बुः । Syzygium

jambos (L.) Alston 1931 - Rosenapfel

- Malabar Plum / Rose Apple

[Bildquelle: mauroguanandi. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mauroguanandi/3320773767/. --

Zugriff am 2011-01-16. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: जम्बुः । Syzygium

jambos (L.) Alston 1931 - Rosenapfel

- Malabar Plum / Rose Apple

[Bildquelle: mauroguanandi. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mauroguanandi/3321640922/ . --

Zugriff am 2011-01-16. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Canis aureus indicus Hodgson, 1833 - Indischer Goldschakal -

Indian Golden Jackal

Sein Geheul ist typisch für den indischen Dschungel.

Körperlänge: 60 - 75 cm

Gewicht: 7 - 15 kg

Lebensraum: ganz Indien, bis 3000 m ü. M., Städte und Siedlungen

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt als Einzelgänger, oder paarweise oder in Rudeln

Abb.: शृगालः

।

Canis aureus indicus Hodgson, 1833 - Indischer Goldschakal -

Indian Golden Jackal, Sariska Tiger Reserve - सरिस्का राष्ट्रीय उद्यान, Rajasthan

[Bildquelle:

Digital.Knave. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/digitalknave/344220065/. -- Zugriff am

2007-07-15. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: भूरिमायः

। मृगधूर्तकः । वञ्चकः । Canis aureus indicus Hodgson,

1833 - Indischer Goldschakal - Indian Golden Jackal, Seoni, Madhya Pradesh

[Bildquelle:

Tarique Sani. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/tariquesani/3716555124/. -- Zugriff am

2011-01-16. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

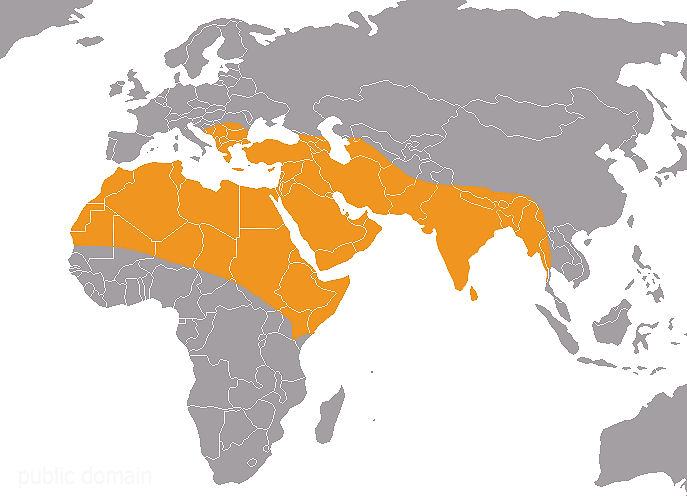

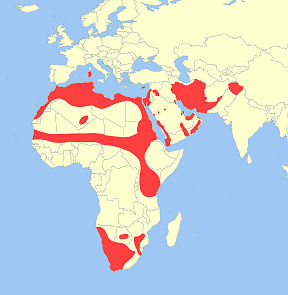

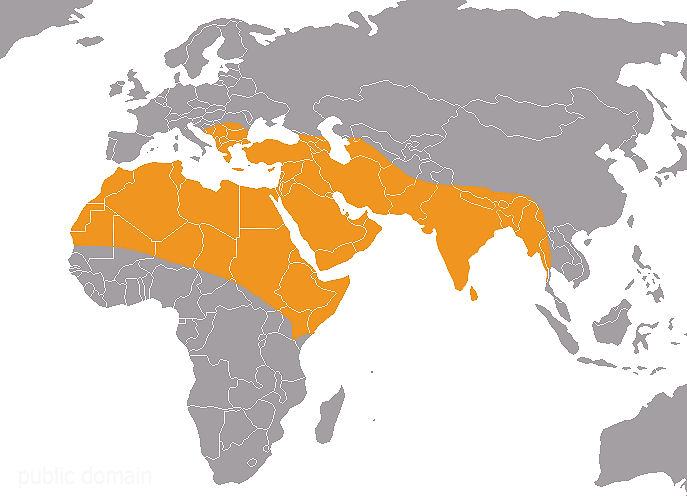

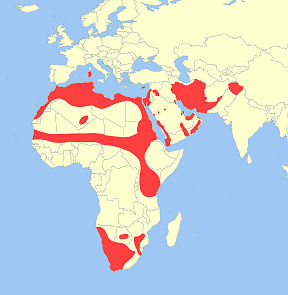

Abb.: Ungefährer Lebensraum des Canis aureus

Linnaeus, 1758 - Goldschakal - Golden Jackal

[Bildquelle: Jonathan Hornung / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Siehe:

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā

/ übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. --

Canis aureus. -- URL:

http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/canis_aureus.htm

|

"The Jackal varies considerably in the colour

of its fur according to season and locality. A black variety is by no

means rare in Bengal ; but I never saw or heard of it in the south

of India.

This well-known animal abounds throughout all

India, and its habits are too well known to require much notice. It

occurs also in Ceylon, but is rare in lower Burmah, and said to be

only of recent introduction there. It is a very useful scavenger,

clearing away all garbage and carrion from the neighbourhood of large towns,

but occasionally committing depredations among poultry and other domestic

animals. Sickly sheep and goats usually fall a prey to him ;

and a wounded antelope is pretty certain to be tracked and hunted to

death by jackals. They will however partake freely of vegetable food.

Sykes says he devastates the vineyards in the west of India ; in

Bhagulpore he is said to be fond of sugar-cane ; and he everywhere consumes large

quantities of the bēr fruit, Zizyphus jujuba. In Wynaad, as well as

in Ceylon, he devours considerable quantities of ripe

coffee-berries : the seeds pass through him, well pulped, and are found and picked up

by the coolies : it is asserted that the seeds so found make the

best coffee !

The female jackal brings forth about four

young in holes in the ground, occasionally in dry drains in cantonments.

The Jackal is easily pulled down by greyhounds, but gives an excellent

run with foxhounds. They are very tenacious of life, and sham dead in

a way to deceive even an experienced sportsman. I have seen one, after

being worried by a pack of hounds, and getting a good rap or two on

its head with a heavy whip, limp off some time afterwards when

unobserved, with apparently a good chance of affording another run on a future

day. I have known a jackal come to the aid of his comrade (or

mate perhaps) when seized by greyhounds, and attack them furiously, whilst

I was close by on horseback. The call of the jackal is familiar

to all residents in India, and is certainly the most unearthly and

startling music. The natives assert that they cry after every watch of the

night. Jackals not unfreqently get hydrophobia, especially in

Bengal, and I have known several fatal cases from their bite.

Connected with the old name of the "lion's

provider" are the generally credited tales about one always attending the

tiger. Mr. Elliot says, "Native sportsmen universally believe that

an old jackal, which (in the South of India) they call Bhālū is in

constant attendance on the tiger, and whenever his cry is heard, which is

peculiar and different from that of the jackal generally, the vicinity of a

tiger is confidently pronounced. I have heard the cry attributed to the Bhālū,

frequently." The " Kole bhaloo" is frequently referred to by

Lieutenant Rice, in his very interesting work on "Tiger-shooting in Rajpootana," as

having been frequently heard and seen by him in company

with the tiger. In Bengal the same jackal is called " Phēall" or

Phao, or Pheeow, or Phnew, from its call, and in some parts Ghog,

though that name is said by some to refer to some other (fabulous)

animal. "It is," says Johnson, in his Field Sports of India, as

quoted in the India Sporting Review, N.S. vol. I., "a jackal following the scent of the tiger

and making a noise very different from their

usual cry, which I imagine they do for the purpose of warning their species

of danger." Again, "Soon after the tiger passed within a few yards of

us. In a minute or two after he had passed, we plainly saw the

jackal, and heard him cry when very near us. I have often heard it said that

the Pheall (or provider, as it is sometimes called) always goes before

the tiger, but in this instance he followed him, which I have also

seen him do at other times. "Whether he is induced to follow the tiger

for the sake of coming in for part of the booty, or whether he merely

follows as small birds often follow a bird of prey, I cannot say. Evidently his

cry is different from what it is at other times, which indicates danger

being near, particularly as whenever that cry is heard the voice of no

other jackal is, nor is that particular call ever heard in any part of the

country where there are not large beasts of prey. Pheall, I believe, was

the original, and is now the usual name, from its resembling the cry they

make ; but they are better known in Ramghur by the name Phinkar, which

means crier proclaimer or warner." Mr. Blyth records that, "some time ago I heard a pariah dog, upon sniffing the collection of

live tigers, before referred to, set up the most extraordinary cry I have ever

heard uttered by a dog, and which I cannot pretend to record more

intelligibly, but it was doubtless an analogous note to the Pheall cry

of the jackal." I have often heard this peculiar cry, and seen a

jackal following a tiger in various parts of the country ; and I have

already noted my turning a jackal out of the same bush as a cheeta.

A horn is supposed by the natives in the same

parts of India to grow on the head of some jackals, which is of

great reputed virtue, ensuring prosperity to its possessor. The same idea is

prevalent in Ceylon.

The Jackal is found over a great part of

Asia, in Southern Europe, and in Northern Africa."

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

142ff.] |

2.9.11. Wildkatzen und Hauskatze

|

6.a./b. otur biḍālo mārjāro vṛṣadaṃśaka ākhubhuk

ओतुर् बिदालो मार्जारो वृषदंशक आखुभुक् ।६ क।

[Bezeichnungen für Wildkatzen und Hauskatze:]

-

ओतु - otu m.: Katze (zu

av 1: erquicken, fördern, schützen)

- बिदाल

- biḍāla m.: Katze

- मार्जार

- mārjāra m.: der Abwischer, der (sich) Waschende

- वृषदंशक

- vṛṣadaṃśaka m.: der Männer beißt; der potente Beißer

- आखुभुज्

- ākhubhuj m.: Maus-Fresser

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A cat."

Die wichtigsten Wildkatzen Indiens sind:

- Felis chaus Schreber, 1777 - Rohrkatze - Jungle Cat

- Felis silvestris ornata Gray, 1832 - Asiatische Wildkatze - Asiatic Wild Cat / Desert Cat

- Prionailurus bengalensis Kerr, 1792 - Bengalkatze - Leopard Cat

- Prionailurus rubiginosus I. Geoffroy

Saint-Hilaire, 1831- Rostkatze - Rusty-Spotted Cat

- Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 -

Fischkatze - Fishing Cat

Dazu kommt

- Felis catus Linnaeus, 1758 - Hauskatze - Domestic Cat

Felis chaus Schreber, 1777 - Rohrkatze - Jungle Cat

Körperlänge: 60 cm

Gewicht: 5 - 6 kg

Lebensraum: ganz Indien, bis 2400 m ü. M.

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt als Einzelgänger oder paarweise

Abb.: Felis chaus Schreber, 1777 - Rohrkatze - Jungle Cat

[Bildquelle: Hardwicke I, 1830. -- S. 18.]

Abb.: Felis chaus Schreber, 1777 - Rohrkatze - Jungle Cat, Munsiyari,

Uttarakhand

[Bildquelle: L. Shyamal / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Felis chaus Schreber, 1777 - Rohrkatze - Jungle Cat, Munsiyari,

Uttarakhand

[Bildquelle: L. Shyamal / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Lebensraum von Felis chaus Schreber, 1777 - Rohrkatze - Jungle Cat

[Bildquelle: Chermundi - IUCN / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

|

"This is the common wild cat over all India,

from the Himalayas to Cape Comorin, and from the level of the sea

to 7,000 or 8, 000 feet of elevation. It frequents alike jungles and the

open country, and is very partial to long grass and reeds, sugar-cane

fields, corn-fields, &c. It does much damage to game of all kinds hares,

partridges, &c., and quite recently I shot a peafowl at the edge of a

sugar-cane field, when one of these cats sprang out, seized the peafowl,

and after a short struggle (for the bird was not dead) carried it off before

my astonished eyes, and in spite of my running up, made good his escape

with his booty. It must have been stalking these very birds, so

immediately did its spring follow my shot. It is occasionally very destructive

to poultry.

It is said to breed twice a year, and to have

three or four young at a birth. I have very often had the young

brought me, but always failed in rearing them, and they always evinced a

most savage and untameable disposition. I have seen numbers of cats

about villages in various parts of the country, that must have been hybrids

between this cat and tame ones ; and Mr. Elliot, as quoted by Blyth,

says the same.

A melanoid variety is not very rare in some

parts. Dr. Scott has procured it both near Hansi and in the

neighbourhood of Umballa.

This jungle-cat appears to be found

throughout Africa, most abundant perhaps in the north."

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

112.] |

Felis silvestris ornata Gray, 1832 - Asiatische Wildkatze - Asiatic Wild Cat / Desert Cat

Wird wegen ihres Fells gejagt (für einen Pelzmantel müssen mindestens 30

Katzen sterben).

Körperlänge: 47 - 54 cm

Gewicht: 2 - 4 kg

Lebensraum: Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt als Einzelgänger

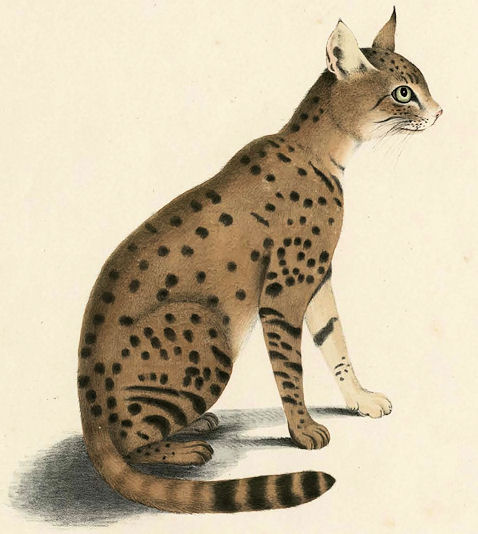

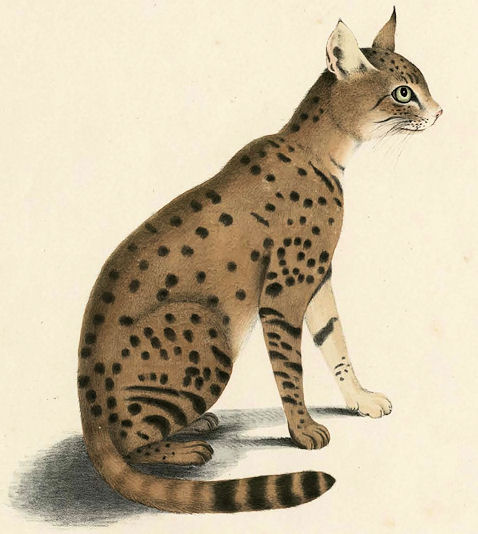

Abb.: Felis silvestris ornata Gray, 1832 - Asiatische Wildkatze - Asiatic Wild Cat / Desert Cat

[Bildquelle: Hardwicke I, 1830. -- S. 16.]

Abb.: Ermordete Felis silvestris ornata Gray, 1832 - Asiatische Wildkatze - Asiatic Wild Cat / Desert Cat, ehemalige Bundes-Pelzfachschule, Frankfurt/Main

[Bildquelle: Mickey Bohnacker / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

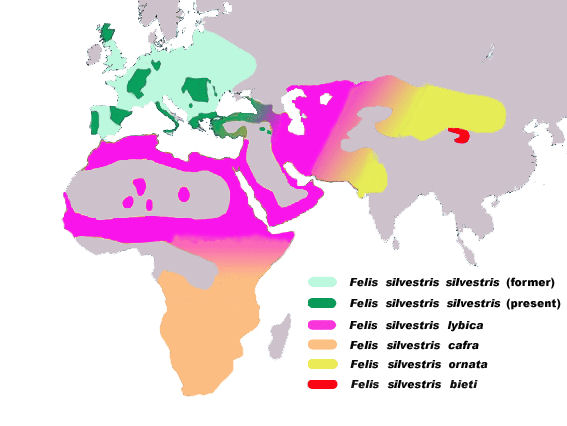

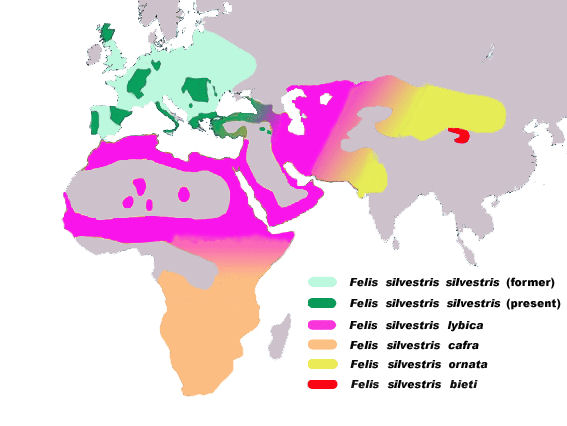

Abb.: Lebensräume der 5 Unterarten von Felis silvestris Schreber, 1775 - Wildkatze - Desert Cat

[Bildquelle: Christophe cagé / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

|

"Mr. Blyth first obtained it from the district

of Humana, near Hansi ; and Dr. Scott, who sent the specimens, stated

that "it is very common at Hansi, frequenting open sandy plains,

where the field-rat must be its principal food. I hardly ever remember

seeing it in what could be called jungle, or even in grass. One of these

spotted cats lived for a long time under my haystack, and I believe

it to have been the produce of a tame cat by a wild one. The wild

one I have seen of half a dozen shades of colour, and you also

frequently see a tendency in these cats to run into stripes, especially on

the limbs."

I have procured it at Hissar, where it is

common ; at Mhow, far from rare ; also at Saugor, and near Nagpore,

rarely; but it does not appear to extend into the Gangetic valley, and is

rare south of the Nerbudda. Those I obtained at Mhow and Saugor were

generally killed by my greyhounds in corn and stubble fields, but I

have seen it in date-groves though never in jungle. At Hissar it is

almost always found among the low sand-hills, occasionally in bare

fields, usually in the same ground as the desert fox (Vulpes leucopus).

Here it appears to feed chiefly on the jerboa-rat (Gerbillus indicus),

so abundant in the sandy tract there."

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

110f.] |

Prionailurus bengalensis Kerr, 1792 - Bengalkatze - Leopard Cat

Körperlänge: 60 cm

Gewicht: 3 - 7 kg

Lebensraum: ganz Indien außer Deccan-Hochplateau und Trockengebiete Westindiens

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt als Einzelgänger

Abb.: Prionailurus bengalensis Kerr, 1792 - Bengalkatze - Leopard Cat, Zoo

[Bildquelle: M Kuhn. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mkuhn/3816307969/. -- Zugriff am 2010-12-15. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Prionailurus bengalensis Kerr, 1792 - Bengalkatze - Leopard Cat, Zoo

[Bildquelle: Chensiyuan / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

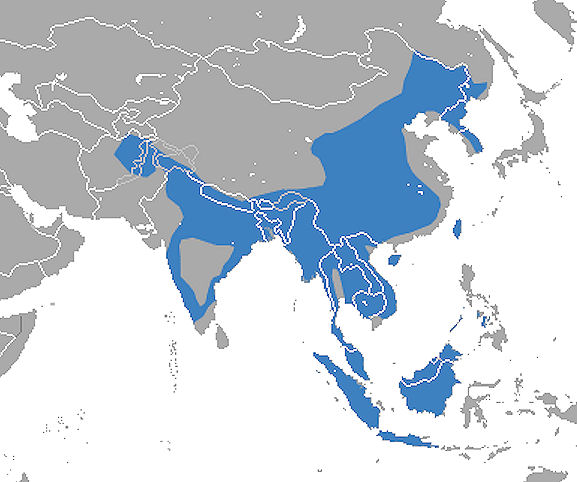

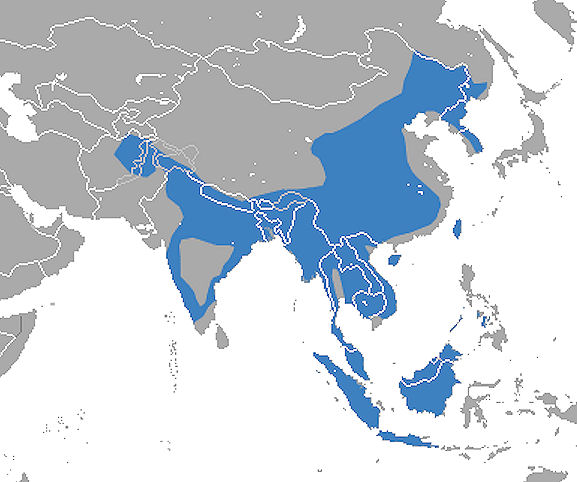

Abb.: Lebensräume von Prionailurus bengalensis Kerr, 1792 - Bengalkatze - Leopard Cat

[Bildquelle: Chermundi - IUCN / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

|

"The Leopard-cat is found throughout the hilly

regions of India, from the Himalayas to the extreme south and

Ceylon, and in richly wooded districts, at a low elevation occasionally,

or where heavy grass jungle is abundant, mixed with forest and brushwood. In

the South of India it is most abundant in Coorg, Wynaad, and the

forest tract all along the Western ghats ; but is rare on the east

coast and in Central India. It ascends the Himalayas to a considerable

elevation, and is said by Hodgson even to occur in Tibet, and is found

at the level of the sea in the Bengal Sunderbuns. It extends through

Assam, Burmah, the Malayan peninsula, to the islands of Java and

Sumatra at all events.

Mr. Elliot says of his Wagati, that "it is

very fierce, living in trees in the thick forests, and preying on birds

and small quadrupeds. A shikaree declared that it drops on larger

animals and even on deer, and eats its way into the neck ; that the

animal in vain endeavours to roll or shake it off, and at last is

destroyed." In Coorg, I was informed that it lives in hollow trees, and commits

great depredations on the poultry of the villagers. It also destroys

hares, morse deer, &c. Hutton says, "I have a beautiful specimen alive, so

savage that I dare not touch her. They breed in May, have only three or

four young, in caves or beneath masses of rock." Mr. Blyth says, "I have had many in captivity, none of which ever showed a disposition to

become tame and confiding, even though but half-grown when they came

into my possession, but I never had a small kitten to begin with. It

never paces its cage for exercise during the daytime at least, but

constantly remains crouched in a corner, though awake and vigilant." I

have seen several caged, and now possess one, all of which were quite

untameable, and I noticed the same repose during the day that Mr. Blyth observed."

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

106f. |

Prionailurus rubiginosus I. Geoffroy

Saint-Hilaire, 1831- Rostkatze - Rusty-Spotted Cat

Kleinste Katze der Welt (1/2 bis 3/4 einer Hauskatze)

Körperlänge: 35 - 48 cm

Gewicht: 1 - 1,6 kg

Lebensraum: indischer Subkontinent bis Rajasthan, vereinzelt in Jammu und

Kashmir; auch in menschlichen Siedlungen (geniert manchmal ihre Jungen auf

Hausdächern)

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt als Einzelgänger

Abb.: Prionailurus rubiginosus I. Geoffroy

Saint-Hilaire, 1831- Rostkatze - Rusty-Spotted Cat, Zoo

[Bildquelle: UrLunkwill / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Prionailurus rubiginosus I. Geoffroy

Saint-Hilaire, 1831- Rostkatze - Rusty-Spotted Cat, Anamalai Hills (ஆனைமலை,ആനമല),

Südindien

[Bildquelle: Shankar Raman / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: Lebensraum von Prionailurus rubiginosus I. Geoffroy

Saint-Hilaire, 1831- Rostkatze - Rusty-Spotted Cat

[Bildquelle: John Burkitt / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

|

"I have only procured this cat in the Carnatic,

in the vicinity of Nellore and Madras. Belanger's specimen was procured

in the same district, at Pondicherry, and I never saw or heard of it

in Central India, or on the Malabar coast. It occurs in Ceylon also, but

there, according to Kelaart, is found, not in the northern provinces,

which resemble the Carnatic, but in the south, and on the hills, even at

Newera-ellia. This distribution, and the somewhat different character of the

markings, incline me to think that this may be a different species,

and I think it possible that it may be Fells Jerdoni of Blyth, which that

gentleman recently writes me is perhaps the representative of F.

rubiginosa on the Malabar coast. In the British Museum there is a specimen

stated to be from Malacca, but Mr. Blyth is inclined to think this a

mistake.

This very pretty little cat frequents grass

in the dry beds of tanks, brushwood, and occasionally drains in the

open country and near villages, and is said not to be a denizen of the

jungles. I had a kitten brought me when very young (in 1846), and it became

quite tame, and was the delight and admiration of all who saw it. Its

activity was quite marvellous, and it was very playful and elegant in its

motions. When it was about eight months old, I introduced it into

a room where there was a small fawn of the Gazelle, and the little

creature flew at it the moment it saw it, seized it by the nape, and was

with difficulty taken off. I lost it shortly after this. It would occasionally

find its way to the rafters of bungalows and hunt for squirrels. Mr. W.

Elliot notices that he has seen several undoubted hybrids between this

and the domestic cat, and I have also observed the same."

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

108f.] |

Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 -

Fischkatze - Fishing Cat

Körperlänge: 70 cm

Gewicht: 5,5 - 8 kg

Lebensraum: Nord-, Ost und Nordost Indien bis Orissa, West-Ghats

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt als Einzelgänger

Abb.: Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 -

Fischkatze - Fishing Cat

[Bildquelle: Hardwicke II, 1833. -- S. 16.]

Abb.: Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 -

Fischkatze - Fishing Cat, Zoo

[Bildquelle: Ltshears / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 -

Fischkatze - Fishing Cat, Zoo

[Bildquelle: Josh More. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/guppiecat/3445115044/. -- Zugriff am

2010-12-15. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Prionailurus viverrinus Bennett, 1833 -

Fischkatze - Fishing Cat, Zoo

[Bildquelle: Hubert K. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/maunzy/3940029368/. -- Zugriff am 2010-12-15.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

|

"This large tiger-cat is found throughout

Bengal up to the foot of the south-eastern Himalayas, extending into

Burmah, China, and Malayana. I have not heard of its occurrence in Central

India nor in the Carnatic, but is tolerably common in Travancore and Ceylon,

extending up the Malabar coast as far as Mangalore. I have had one

killed close to my house at Tellicherry. In Bengal it inhabits low watery

situations chiefly, and I have often put it up on the edge of swampy

thickets in Purneah. It is said to be common in the Terai and marshy

region at the foot of the Himalayas, but apparently not extending

further west than Nepal. Buchanan Hamilton remarks, "In the

neighbourhood of Calcutta it would seem to be common. It frequents reeds near

water ; and besides fish, preys upon Ampullariae, Unios, and various

birds. It is a fierce untameable creature, remarkably beautiful, but which has

a very disagreeable smell." On this Mr. Blyth observes, "I have not remarked the latter, though I have had several big toms quite tame, and

ever found this to be a particularly tameable species. A newly caught

male killed a tame young leopardess of mine about double his size."

The Rev. Mr. Baker, writing of its habits in Malabar, says "that it often kills pariah dogs ; and that he has known instances of slave children (infants)

being taken from their huts by this cat ; also young calves.""

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

103f.] |

Felis catus Linnaeus, 1758 - Hauskatze - Domestic Cat

Abb.: Katze, Mahabalipuram - மகாபலிபுரம், Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle:

jrambow. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rambow/381822844/. -- Zugriff am

2007-07-15. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: ओतुः ।

गुम्पिरिति नाम सम्स्कृतमार्जारः । Gumpi, DER Sanskritkater

[Bildquelle: A. Payer, 2009]

Abb.: मार्जारः

।

[Bildquelle: A. Payer, 2009]

Abb.: वृषदंशकः

। Tüpfli-नाम पयराणामोतुः ।

[Bildquelle: A. Payer, 2004]

Siehe:

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā

/ übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. --

Felis catus. -- URL:

http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/felis_catus.htm

2.9.12. Varanus sp. - Warane - Monitor lizards

|

6.c./d. trayo gaudhera-gaudhāra-gaudheyā godhikātmaje

त्रयो गौधेर-गौधार-गौधेया गोधिकात्मजे ॥६ ख॥

Söhne der गोधिका - godhikā f.: Waran

heißen:

-

गौधेर -

gaudhera m.: Gaudhera

- गौधार

- gaudhāra m.: Gaudhāra

- गौधेय

- gaudheya m.: Gaudheya

|

Colebrooke (1807): "An iguana."

Iguanas gibt es aber nur in Zentralamerika, Südamerika und der Karibik!

PW: godhikā = "eine Art Eidechse. Lacerta

Godica." Lacerta Godica scheint seither nur in

Sanskritwörterbüchern ihr Unwesen zu treiben, scheint aber in der Natur

nicht vorzukommen.

In Indien kommen folgende Arten von Waranen vor:

- Varanus bengalensis Daudin,

1802 - Bengalenwaran - Bengal monitor / Common Indian monitor (ganzer

Subkontinent)

- Varanus salvator Laurenti, 1768 - Bindenwaran

- Water monitor (Orissa, Bengalen, Bangladesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland)

- Varanus griseus Daudin, 1803 - Wüstenwaran

- Desert Monitor (Trockengegenden Pakistans und Westindiens)

- Varanus flavescens Hardwicke & Gray, 1827 - Yellow Monitor

(Gangesebene, häufig in Bihar)

Varanus bengalensis Daudin,

1802 - Bengalenwaran - Bengal monitor / Common Indian monitor

Körperlänge: 175 cm (Schwanz 100 cm)

Gewicht: bis 7 kg

Lebensraum: weit auf dem ganzen Subkontinent und Sri Lanka

Abb.: गोधिका

।

Varanus bengalensis Daudin,

1802 - Bengalenwaran - Bengal monitor / Common Indian monitor, Kandy -

මහ නුවර, Sri Lanka

[Bildquelle: HanakoSatou (佐藤芭那) / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Varanus bengalensis Daudin,

1802 - Bengalenwaran - Bengal monitorr / Common Indian monitor, Wyanad -

വയനാട്, Kerala

[Bildquelle: L. Shyamal / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

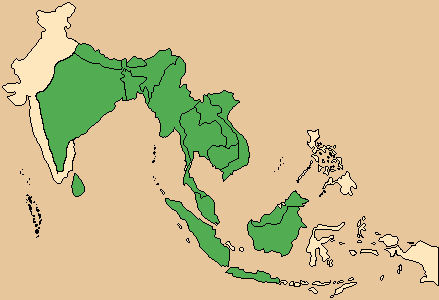

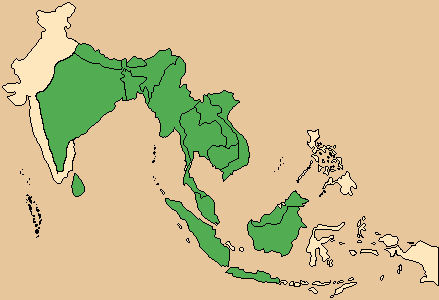

Varanus salvator Laurenti, 1768 - Bindenwaran

- Water monitor

Körperlänge: bis über 3 m

Gewicht: bis 25 kg

Lebensräume: Nordostindien, Sri Lanka

Abb.: Varanus salvator Laurenti, 1768 - Bindenwaran - Water monitor,

Bangkok - กรุงเทพฯ,

Thailand

[Bildquelle: Bing / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: Varanus salvator Laurenti, 1768 - Bindenwaran - Water monitor,

Khao Yai National Park - อุทยานแห่งชาติเขาใหญ,

Thailand

[Bildquelle: Chris huh / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

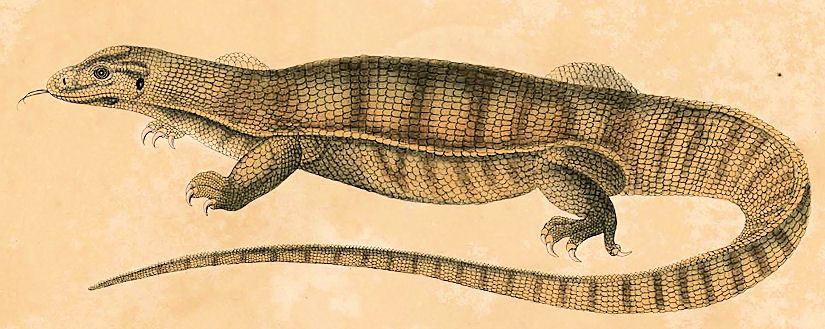

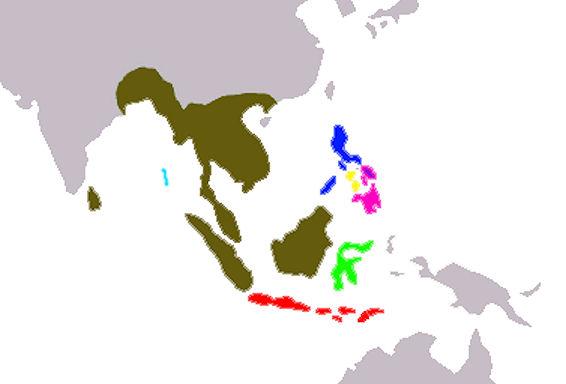

Abb.: Verbreitung des Bindenwarans (Varanus salvator Laurenti, 1768)

und seiner Unterarten

[Bildquelle: Kamikaza

Varanus griseus Daudin, 1803 - Wüstenwaran

- Desert Monitor

Körperlänge: bis 150 cm

Lebensraum: Trockengegenden Pakistans und Nordwestindiens

Varanus griseus Daudin, 1803 - Wüstenwaran - Desert Monitor,

Syrien

[Bildquelle: copepodo. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/63661371@N00/2770760869. -- Zugriff am

2010-12-09. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Varanus flavescens Hardwicke & Gray, 1827 - Yellow

Monitor

Lebensraum: Indusebene, Gangesebene, in Bihar häufig, Brahmaputraebene

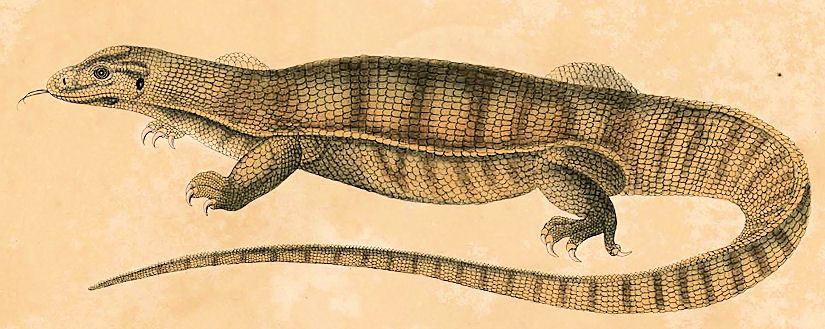

Abb.: Varanus flavescens Hardwicke & Gray, 1827 - Yellow Monitor

[Bildquelle: Hardwicke II, 1833. -- S. 174.]

Abb.: Varanus flavescens Hardwicke & Gray, 1827 - Yellow Monitor, Zoo

[Bildquelle: muzina-shanghai. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/muzina_shanghai/584481425/. -- Zugriff am

2010-12-10. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Siehe:

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā

/ übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. --

Varanus sp. -- URL:

http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/varanus.htm

| "Ein sonderbarer Irrtum deutscher Forscher hat einigen großen

Echsen, welche die erste Familie der Unterordnung bilden, zu dem

Namen Warn-Eidechsen verholfen. Die bekanntesten Arten der Familie

bewohnen Ägypten und werden dort Waran genannt; dieses Wort hat man

in Warner umgewandelt und dieselbe Bedeutung auch durch den

wissenschaftlichen Namen Monitor festgehalten: Waran und

Warner aber haben durchaus keine Beziehung zu einander; denn Waran

bedeutet einfach Eidechse. Die Warane oder Wassereidechsen (Varanidae)

unterscheiden sich von den übrigen Eidechsen, denen sie hinsichtlich

ihres langgestreckten Körpers, des breiten, ungekielten Rückens und

der vollständig ausgebildeten, vorn und hinten fünfzehigen, mit

kräftigen Nägeln bewehrten Füße ähneln, durch die Beschuppung, die

Bildung der Zunge und die Anlage und Gestaltung der Zähne. Ihr Kopf

ist verhältnismäßig länger als der anderer Eidechsen und dem der

Schlangen nicht ganz unähnlich; aber auch ihr Hals und der übrige

Leib, einschließlich des Schwanzes, übertrifft an Schlankheit die

bezüglichen Leibesteile der Verwandten. Die Zunge liegt im

zurückgezogenen Zustande gänzlich in einer Hautscheide verborgen,

kann aber sehr weit hervorgestreckt werden und zeigt dann zwei

lange, hornige Spitzen. Die Zähne, welche der Innenseite der

Kieferrinnen anliegen, stehen ziemlich weit von einander und sind

von kegelförmiger Gestalt, vorn spitzig, hinten stumpfkegelig;

Gaumenzähne sind nicht vorhanden. Die kleinen in der Fünfform oder

in Querreihen angeordneten Tafelschuppen vergrößern sich auf dem

Kopfe nicht zu wirklichen Schildern, und auch die der Bauchseite

weichen wenig von denen des Rückens ab.

Die Warane, von denen man ungefähr dreißig Arten kennt, bewohnen

die östliche Hälfte der Erde, namentlich Afrika, Südasien und

Ozeanien. Einige Arten sind vollendete Landtiere, welche eine

passende Höhlung zum Verstecke erwählen und in der Nähe derselben,

diese bei Tage, jene mehr in der Dämmerung oder selbst in der Nacht,

ihrer Jagd obliegen; andere hingegen müssen zu den Wassertieren

gezählt werden, da sie sich bloß in der Nähe der Gewässer, in

Sümpfen oder an Flussufern aufhalten und bei Gefahr stets so eilig

als möglich dem Wasser zuflüchten. Die einen wie die anderen sind

höchst bewegliche Tiere. Sie laufen mit stark schlängelnder

Bewegung, auf festem Boden so rasch dahin, dass sie kleine

Säugetiere oder selbst Vögel einzuholen im Stande sind, klettern

trotz ihrer Größe vortrefflich und schwimmen und tauchen, obgleich

sie keine Schwimmhäute besitzen, ebenso gewandt als ausdauernd. Zu

längerem Verweilen im Wasser befähigen sie zwei größere Hohlräume im

Inneren ihrer Oberschnauze, welche mit den Nasenlöchern in

Verbindung stehen, mit Luft gefüllt und durch die beweglichen Ränder

der Nasenlöcher abgeschlossen werden können. In ihrem Wesen und

Gebaren, ihren Sitten und Gewohnheiten erinnern die Warane an die

Eidechsen, nicht aber an die Krokodile; sie sind jedoch, ihrer Größe

und Stärke entsprechend, entschieden räuberischer, mutiger und

kampflustiger als die kleineren Verwandten. Vor den Menschen und

wohl auch vor anderen größeren Tieren weichen sie stets zurück, wenn

sie dies können, diejenigen, welche auf der Erde wohnen, indem sie

blitzschnell ihren Löchern, die, welche im Wasser leben, indem sie

ebenso eilfertig dem Wohngewässer zueilen; werden sie aber gestellt,

also von ihrem Zufluchtsorte abgeschnitten, so nehmen sie ohne

Bedenken den Kampf auf, schnellen sich mit Hülfe ihrer Füße und des

kräftigen Schwanzes hoch über den Boden empor und springen dem

Angreifer kühn nach Gesicht und Händen.

Ihre Nahrung besteht in Tieren der verschiedensten Art. Der

Nilwaran, ein bereits den alten Ägyptern wohlbekanntes, auf ihren

Denkmälern verewigtes Tier, galt früher als einer der gefährlichsten

Feinde des Krokodils, weil man annahm, dass er dessen Eier aufsuche

und zerstöre und die dem Eie entschlüpften jungen Krokodile verfolge

und verschlinge. Wie viel wahres an diesen Erzählungen ist, lässt

sich schwer entscheiden; wohl aber darf man glauben, dass ein Waran

wirklich ohne Umstände ein junges Krokodil verschlingt oder auch ein

Krokodilei hinabwürgt, falls er des einen und anderen habhaft werden

kann. Leschenault versichert, Zeuge gewesen zu sein, dass einige

indische Warane vereinigt ein Hirschkälbchen überfielen, es längere

Zeit verfolgten und schließlich im Wasser ertränkten, will auch

Schafknochen in dem Magen der von ihm erlegten gefunden haben; ich

meinesteils bezweifle entschieden, dass irgend eine Art der Familie

größere Tiere in der Absicht, sie zu verspeisen, angreift, bin aber

von Arabern und Afrikanern überhaupt wiederholt berichtet worden,

dass Vögel bis zur Größe eines Kiebitzes oder Säugetiere bis zur

Größe einer Ratte ihnen nicht selten zum Opfer fallen. Die auf

festem Boden lebenden Warane jagen nach Mäusen, kleinen Vögeln und

deren Eiern, kleineren Eidechsen, Schlangen, Fröschen, Kerbtieren

und Würmern; die wasserliebenden Mitglieder der Familie werden sich

wahrscheinlich hauptsächlich von Fischen ernähren, ein unvorsichtig

am Ufer hinlaufendes, schwaches Säugetier oder einen ungeschickten

Vogel, dessen sie sich bemächtigen können, aber gewiss auch nicht

verschmähen. Da, wo man sie nicht verfolgt, oder wo sie sich leicht

zu verbergen wissen, werden sie wegen ihrer Räubereien an jungen

Hühnern und Hühnereiern allgemein gefürchtet und gehasst, und dies

sicherlich nicht ohne Grund und Ursache.

An gefangenen Waranen kann man leicht beobachten, dass sie

tüchtige Räuber sind. Obwohl sie auch tote Tiere nicht verschmähen,

ziehen sie doch lebende Beute jenen entschieden vor. Ihr Gebaren

ändert sich vollständig, wenn man ihnen ein Dutzend lebende

Eidechsen oder Frösche in den Käfig wirft. Die träge Ruhe, in

welcher auch sie gerne sich gefallen, weicht der gespanntesten

Aufmerksamkeit: die kleinen Augen leuchten, und die lange Zunge

erscheint und verschwindet in ununterbrochenem Wechsel. Endlich

setzen sie sich in Bewegung, um sich eines der unglücklichen Opfer

zu bemächtigen. Die Eidechsen rennen, klettern, springen

verzweiflungsvoll im Raume hin und her oder auf und nieder; die

Frösche hüpfen angstvoll durcheinander: der sie in Todesschrecken

versetzende Feind schreitet langsam und bedächtig hinter ihnen

drein. Aber Augen und Zunge verraten, dass er nur des Augenblickes

wartet, um zuzugreifen. Urplötzlich schnellt der gestreckte Kopf

vor; mit fast unfehlbarer Sicherheit ist ein Frosch, selbst die

behendeste Eidechse gepackt, durch einen quetschenden Biss betäubt

und verschlungen. So ergeht es einem Opfer nach dem anderen, bis

alle verzehrt sind, und sollten es Dutzende von Eidechsen oder

Fröschen gewesen sein. Legt man dem Warane ein oder mehrere Eier in

den Käfig, so nähert er sich gemächlich, betastet züngelnd ein Ei,

packt es sanft mit den Kiefern, erhebt den Kopf, zerdrückt das Ei

und schlürft behaglich den Inhalt hinab, leckt auch etwa ihm am

Maule herabfließendes Eiweiß oder den Dotter sorgfältig mit der

geschmeidigen, die ganze Schnauze und einen Teil des Kopfes

beherrschenden Zunge auf. Genau ebenso wird er auch in der Freiheit

verfahren.

Mehr als sonderbar ist, dass wir über die

Fortpflanzungsgeschichte der Warane noch immer nicht genügend

unterrichtet sind. Hätte ich während meines Aufenthaltes in Afrika

diese Lücke in ihrer Naturgeschichte gekannt, so würde ich mich

ihrer Beobachtung eifriger gewidmet haben, als es geschehen; doch

will ich damit keineswegs gesagt haben, dass ich sicheres erfahren

haben würde, weil mir die Araber und Sudaner, welche sonst

unaufgefordert über jedes Tier Auskunft geben, so viel ich mich

erinnere, über die Fortpflanzung dieser Echsen niemals etwas erzählt

haben. So viel mir bekannt, gibt nur Theobald über eine indische Art

der Familie, den Gilbwaran (Varanus flavescens), kurzen

Bericht. »Die Warane«, bemerkt er, »legen ihre Eier in die Erde.

Zuweilen benutzen sie das Nest weißer Ameisen. Die gegen fünf

Zentimeter langen Eier sind walzenförmig, an beiden Enden abgerundet

und schmutzig weiß von Farbe, haben aber immer ein unreines und

widriges Ansehen.« Jedes Weibchen scheint gleichzeitig eine ziemlich

erhebliche Anzahl von ihnen zu legen. Während der Reise des seinem

Forschungsdrange zum Opfer gefallenen, hochachtbaren Klaus von der

Decken wurde eines Tages ein meterlanger Waran mit einem

Schrotschusse getötet und beim Zerlegen gefunden, dass er mit

vierundzwanzig Eiern trächtig ging.

Für den Menschen haben die Warane eine nicht zu unterschätzende

Bedeutung. Durch ihre Räubereien an Haustieren und Eiern werden sie

lästig; andererseits nützen sie auch wieder durch ihr vortreffliches

Fleisch und ihre eigenen, höchst schmackhaften Eier. In vielen

Ländern ihres ausgedehnten Verbreitungsgebietes betrachtet man

allerdings Fleisch und Eier mit Abscheu, in anderen dagegen schätzt

man diese wie jenes nach Gebühr, verfolgt die Warane deshalb auch

auf das eifrigste, und zwar gewöhnlich mit Hülfe von Hunden, welche

sie im Walde aufsuchen und verbellen. Laut Theobald wird ein

Birmane, so träge er sonst ist, es nicht für eine allzu große Mühe

erachten, einen Baum, in welchem sich ein Waran verborgen hat, zu

fällen, um nur des von ihm hochgeschätzten Leckerbissens habhaft zu

werden. Der gefangenen Wasserechse bindet man die vier Füße über den

Rücken und benutzt hierzu grausamerweise die Sehnen der vorher

gebrochenen Zehen des beklagenswerten Geschöpfes. Waraneier verkauft

man auf den Märkten Birmas teuerer als Hühnereier; sie gelten auch

mit vollstem Rechte als Leckerbissen, sind jedes ekelerregenden

Geruches bar, haben einen wahrhaft köstlichen Wohlgeschmack und

unterscheiden sich nur dadurch von Vogeleiern, dass ihr Weiß beim

Kochen nicht gerinnt. Das Fleisch genießen die Inder im gebratenen

Zustande, wogegen es die Europäer meist zur Herstellung von Suppen

verwenden. Kelaart, welcher solche versuchte, bezeichnet sie als

ausgezeichnet, im Geschmacke einer Hasensuppe ähnlich. Anderweitige

Verwendung findet die schuppige Haut, mit welcher hier und da,

beispielsweise in Nordostafrika, allerlei Gerät überzogen wird. Auch

benutzt man wohl noch diese oder jene Art zu Gaukeleien oder lässt

sie bei Herstellung von Giften eine geheimkrämerische Rolle spielen.

An gefangenen Waranen erlebt man wenig Freude. Anfänglich

betragen sich die ihrer Freiheit beraubten Tiere äußerst ungestüm,

zischen und fauchen nach Schlangenart, sobald man sich ihnen nähert,

oder beißen wütend um sich, sowie sie glauben, den Pfleger erreichen

zu können. Nach und nach werden sie etwas umgänglicher, wirklich

zahm aber selten oder nie, bleiben vielmehr stets bissig und

gefährlich, da man die Kraft ihrer zahnreichen Kinnladen durchaus

nicht unterschätzen darf. Man kann sie nur in größeren Räumen

halten; aber auch hier werden sie wegen ihres sinnlosen Umherrennens

und Kletterns sowie wegen ihrer Gefräßigkeit und Unreinlichkeit

früher oder später lästig.

Man hat auch die Familie der Warane in mehrere Unterabteilungen

gefällt; doch ist diesen kaum die Bedeutung von Sippen beizulegen,

da sich die hervorgehobenen Unterschiede auf geringfügige

Eigenheiten beschränken. Ich halte es für unnötig, hierauf

einzugehen.

[...]

Auf dem Festlande von Indien und den benachbarten großen Eilanden

wird der Waran durch den Binden- oder Wasserwaran, Kabaragoya der

Singhalesen (Varanus salvator, Stellio und

Hydrosaurus salvator, Tupinambis, Varanus, Monitor und

Hydrosaurus bivittatus), vertreten, ein Tier, welches sich durch

den seitlich sehr stark zusammengedrückten Schwanz, die langen

Zehen, die an der Spitze der Schnauze stehenden Nasenlöcher und die

kleinen Schuppen von jenen unterscheidet und deshalb der Untersippe

der Wasserechsen (Hydrosaurus) zugerechnet wird. Die

Oberseite zeigt auf schwarzem Grunde in Reihen geordnete gelbe

Flecken; ein schwarzes Band verläuft längs der Weichen und eine

weiße Binde längs des Halses; die Unterseite ist weißlich.

Ausgewachsene Stücke erreichen ebenfalls zwei Meter an Länge.

Obwohl hauptsächlich auf den Malaiischen Inseln, insbesondere den

Sunda-Eilanden, den Philippinen und Molukken heimisch, kommt der

Bindenwaran doch auch auf dem ostindischen Festlande nebst Ceylon

sowie in Siam und China vor. Auf der Halbinsel von Malakka lernte

ihn Cantor als sehr häufigen Bewohner des hügeligen wie des ebenen

Landes kennen. Während des Tages sieht man ihn gewöhnlich im

Gezweige größerer Bäume, welche Flüsse und Bäche überschatten, auf

Vögel und kleinere Eidechsen lauern oder Nester plündern, gestört

aber sofort, oft aus sehr bedeutender Höhe, ins Wasser hinabspringen.

Unter ihm günstig erscheinenden Umständen siedelt er sich auch in

nächster Nähe menschlicher Wohnungen oder in diesen selbst an und

wird dann zu einem dreisten Räuber auf den Geflügelhöfen. So erfuhr

Eduard von Martens von einem europäischen Pflanzer in der Gegend von

Manila, dass ein »Krokodil« unter seinem Hause lebe und bei Nacht

hervorkomme, um Hühner zu rauben. Dass dieses »Krokodil« nur unser

Waran sein konnte, unterlag für Martens keinem Zweifel. So

unternehmend der Bindenwaran bei seinen Räubereien sich zeigt, so

ungescheut er in unmittelbarer Nachbarschaft des Menschen stiehlt

und plündert, so ängstlich sucht er jederzeit den Verfolgungen

seitens des Herrn der Erde sich zu entziehen. Wenn man ihn auf

ebenem Boden überrascht, eilt er, laut Cantor, so schnell er zu

laufen vermag, davon und womöglich ebenfalls dem Wasser zu; seine

Schnelligkeit ist jedoch nicht so bedeutend, dass er nicht von einem

gewandten Manne überholt werden sollte. Ergriffen, wehrt er sich auf

das mutigste mit Zähnen und Klauen, versetzt auch mit seinem

Schwanze kräftige Schläge.

Die Mitglieder tiefer stehender Kasten bemächtigen sich des

Wasserwaran gewöhnlich durch Aufgraben seiner Höhlen und genießen

dann das Fleisch der glücklich gewonnenen Beute mit Wohlgefallen.

Eine in den Augen der Hindus viel bedeutsamere Rolle aber spielt der

Kabaragoya bei Bereitung der tödlichen Gifte, welche die Singhalesen

noch heutigentags nur zu häufig verwenden. Nach einer Angabe, welche

Tennent gemacht wurde, verwendet man zur »Kabaratel«, der

gefürchtetsten aller Giftmischungen, Schlangen, namentlich die

Hutschlange oder Kobra de Capello (Naja tripudians), die

Tikpolonga (Vipera elegans) und die Carawilla (Trigonocephalus

hypnalis), indem man Einschnitte in ihre Köpfe macht und sie

dann über einem Gefäße aufhängt, im Glauben, das ausfließende Gift

auffangen zu können. Das so gewonnene Blut wird mit Arsenik und

anderen Kraftmitteln vermischt und das ganze mit Hülfe von

Kabaragoyas in einem Menschenschädel gekocht. Unsere Warane müssen

die Rolle der Tiere in Fausts Hexenküche übernehmen. Sie werden von

drei Seiten gegen das Feuer gesetzt, mit ihren Köpfen demselben

zugerichtet, festgebunden und mit Schlägen so lange gequält, bis sie

zischen, also gleichsam das Feuer anblasen. Aller Speichel, welchen

sie bei der Quälerei verlieren, wird sorgsam gesammelt und dem

kochenden Gebräue beigesetzt. Letzteres ist fertig, sobald sich eine

ölige Masse auf der Oberfläche zeigt. Es versteht sich ganz von

selbst, dass der Arsenik der eigentlich wirksame Bestandteil dieses

Giftes ist; die unschuldige Kabaragoya hat sich aber infolge dieses

Schwindels der Giftmischer einen so üblen Ruf erworben, dass man sie

gegenwärtig allgemein und in wahrhaft lächerlichem Grade fürchtet.

Nach Art des Waran hält sie sich auch auf Ceylon vorzugsweise in der

Nähe des Wassers auf und flüchtet diesem zu, sobald sie Gefahr

wittert; beim Austrocknen der Wohngewässer aber sieht sie sich

zuweilen genötigt, Wanderungen über Land zu unternehmen, und bei

dieser Gelegenheit geschieht es auch wohl, dass sie sich in der Nähe

eines Wohnhauses der Singhalesen erblicken lässt oder sogar durch

das Gehöfte läuft. Ein solcher Vorfall gilt als ein schlimmes

Vorzeichen; man fürchtet nun Krankheit, Tod und anderes Unglück und

sucht bei den indischen Pfaffen Schutz, um die üblen Folgen

womöglich zu vereiteln. Diese erscheinen, nachdem der wackere

Gläubige sich zu ihren Gunsten etwas von dem gleisnerischen Mammon

dieser Erde erleichtert, in der durch die Kabaragoya verunreinigten

Hütte und beginnen einen Gesang, welcher der Hauptsache nach in den

Worten:

»Kabara goyin wan dōsey,

Ada palayan e dōsey«

besteht und besagen will, dass nunmehr alles Übel, welches die

Kabaragoya verursacht habe, unschädlich gemacht sei.

Schon Herodot berichtet von einem »Landkrokodile«, welches im

Gebiete der libyschen Wanderhirten lebt und den Eidechsen ähnlich

sieht; Prosper Alpin hält dasselbe Tier für den »Scincus«

der Alten, von welchem man annahm, dass er sich von gewürzreichen

Pflanzen nähre, insbesondere den Wermut liebe und dadurch stärkende

Heilkräfte erhalte, während wir gegenwärtig mit demselben Namen eine

andere Schuppenechse bezeichnen. Gedachtes Landkrokodil ist der Erd-

oder Wüstenwaran (Varanus arenarius, Tupinambis arenarius

und griseus, Varanus scincus und terrestris,

Monitor scincus, Psammosaurus scincus und griseus),

Vertreter der Untersippe der Sandechsen (Psammosaurus), ein

Waran, welcher sich von den bisher genannten hauptsächlich durch

seinen runden, ungekielten Schwanz, die rundlichen, nicht eiförmigen

Schuppen und die kleinen, breiten Schneidezähne unterscheidet, etwas

über 1,5 Meter lang wird, oben auf hellbraunem Grunde mit

grünlichgelben, viereckigen Flecken gezeichnet, auf der Unterseite

einfach sandgelb gefärbt ist und auf seinem Schwanze mehrere

gelbliche Ringe zeigt."

[Quelle: Brehms Thierleben : Allgemeine Kunde des

Thierreichs. -- 7. Bd., 3. Abt.: Kriechthiere, Lurche und

Fische. -- 1. Bd.: Kriechthiere und Lurche. -- 2.,

umgearbeitete und vermehrte Aufl., Kolorirte Ausgabe. -- Leipzig,

1883. -- S. 149ff.] |

2.9.13. Stachelschweine

|

7. a./b. śvāvit tu śalyas tal-lomni śalalī śalalaṃ śalam

श्वावित् तु शल्यस् तल्लोम्नि शलली शललं शलम् ।७ क।

[Bezeichnungen für Stachelschwein:]

-

श्वाविध्

- śvāvidh m.: Hunde-Durchbohrer

- शल्य -

śalya m.: Stachliger, Stachelschwein

Seine Borste nennt man:

-

शलली - śalalī f.:

Stachelschwein-Borste

- शलल - śalala

n.: Stachelschwein-Borste

- शल - śala n.:

Stock, Stachelschwein-Borste

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A porcupine." [b:] "His quills."

In Indien kommen vor:

- Hystrix brachyura Linnaeus, 1758 - Malayan Porcupine (von Nepal

bis Südostchina)

- Hystrix indica Kerr, 1792 - Indisches Stachelschwein - Indian

Crested Porcupine (Indien, Sri Lanka)

- Atherurus macrourus Linnaeus, 1758 - Asiatic Brush-tailed

Porcupine (Nordostindien)

Hystrix brachyura Linnaeus, 1758 - Malayan Porcupine

Körperlänge: 45 - 75 cm

Gewicht: 8 kg

Lebensraum: Wälder und Grasland des östlichen Himalaya, besonders in und bei

landwirtschaftlich genutztem Land

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt als Einzelgänger oder in Gruppen von 2 - 4 Tieren

Abb.: शल्यः ।

Hystrix brachyura Linnaeus, 1758 - Malayan Porcupine, Pakhui Tiger

Reserve, Arunachal Pradesh

[Bildquelle: Nandini Velho / Wikipedia. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Hystrix indica Kerr, 1792 - Indisches Stachelschwein - Indian Crested Porcupine

Häufigstes Stachelschwein Indiens

Körperlänge: 60 - 90 cm

Gewicht: 11 - 18 kg

Lebensraum: ganz Indien, Sri Lanka; zerstört Anpflanzungen in der Nähe von

Waldrändern, frisst Rinde von lebenden Bäumen

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt als Einzelgänger oder in Gruppen von 2 - 4 Tieren

Abb.: शल्यः ।

Hystrix indica Kerr, 1792 - Indisches Stachelschwein - Indian

Crested Porcupine

[Bildquelle: Hardwicke II, 1833. -- S. 36.]

Abb.: शल्यः ।

Hystrix indica Kerr, 1792 - Indisches Stachelschwein - Indian

Crested Porcupine, Zoo

[Bildquelle: Bodlina / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

|

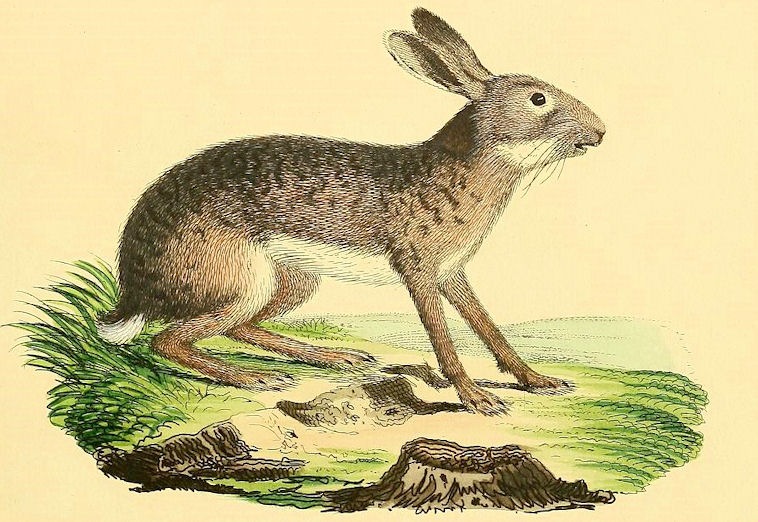

"This porcupine is found over a great part of

India, from the lower ranges of the Himalayas to the extreme south,

but does not occur in Lower Bengal, where it is replaced by the

next one. It forms extensive burrows, often in societies, in the sides of

hills, banks of rivers and nullahs, and very often in the bunds of tanks,

and in old mud walls, &c. &c. In some parts of the country they are

very destructive to various crops, potatoes, carrots, and other

vegetables. They never issue forth till after dark, but now and then one

will be found returning to his lair in daylight. Dogs take up the

scent of the porcupine very keenly, and on the Neelgherries I have killed

many by the aid of dogs, tracking them to their dens. They

charge backwards at their foes, erecting their spines at the same time,

and dogs generally get seriously injured by their strong spines,

which are sometimes driven deeply into the assailant. The porcupine is

not bad eating, the meat, which is white, tasting something between

pork and veal.

This species is common in Ceylon, whence Mr.

Blyth formerly named a young specimen as distinct. It occurs also

in Afghanistan, and probably in other parts of Asia."

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

219f.] |

Atherurus macrourus Linnaeus, 1758 - Asiatic Brush-tailed

Porcupine

Körperlänge: 36 - 57 cm

Gewicht: 1,5 - 4 kg

Lebensraum: Immergrüne Wälder Nordostindiens, besonders im Hügelland

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: unbekannt

Lebt in Gruppen von 6 - 8

Abb.: Atherurus africanus, der afrikanische Verwandte von Atherurus

macrourus Linnaeus, 1758 - Asiatic Brush-tailed Porcupine, Zoo

[Bildquelle: Eloquence / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

2.9.13.1. Stachelschweinborsten

Abb.: शललानि ।

Stachelschweinborsten

[Bildquelle: Lamiot / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Siehe:

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā

/ übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. --

Hystrix

indica. -- URL:

http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/hystrix_indica.htm

2.9.14. Eine schnelle Antilopenart

| 7. c./d. vātapramīr vātamṛgaḥ

kokas tv īhāmṛgo vṛkaḥ

वातप्रमीर् वातमृगः कोकस् त्व्

ईहामृगो वृकः ॥७ ख॥

[Bezeichnungen für eine schnelle Antilopenart:]

- वातप्रमी - vātapramī m.: den Wind

hinter sich Lassender

- वातमृग - vātamṛga m.: Wind-Wild

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A swift antelope."

Zu den in Indien vorkommenden Antilopenarten siehe unten!

2.9.15. Canis lupus pallipes Sykes, 1831 -

Indischer Wolf - Indian Wolf

| 7. c./d. vātapramīr vātamṛgaḥ

kokas tv īhāmṛgo vṛkaḥ

वातप्रमीर् वातमृगः कोकस् त्व् ईहामृगो वृकः ॥७ ख॥

[Bezeichnungen für

Canis lupus pallipes Sykes, 1831 -

Indischer Wolf - Indian Wolf:]

- कोक - koka m.: Wolf

- ईहामृगो - īhamṛga m.: der, für den

Wild sein Begehren ist (so ist das Bahuvrīhi wohl aufzulösen)

- वृक - vṛka m.: Wolf

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A wolf."

Körperlänge: 100 - 130 cm

Gewicht: 15 - 20 kg

Lebensraum: Westindien, Subkontinent, Ladakh bis Sikkim

Noch in Freiheit lebende Individuen: 2000 - 3000

Lebt in Rudeln

Abb.: वृकः ।

Canis lupus pallipes Sykes, 1831 -

Indischer Wolf - Indian Wolf

[Bildquelle: Lydekker, Richard <1849 - 1915>: The great and small

game of India, Burma, & Tibet. -- London, 1900. -- Pl. 9]

Abb.: कोकः ।

Canis lupus pallipes Sykes, 1831 -

Indischer Wolf - Indian Wolf

[Bildquelle: The living animals of the world, 1902]

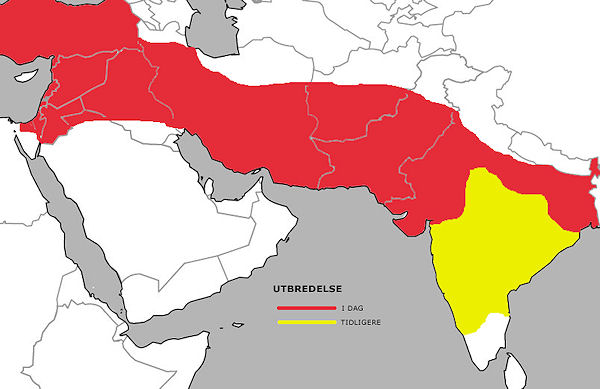

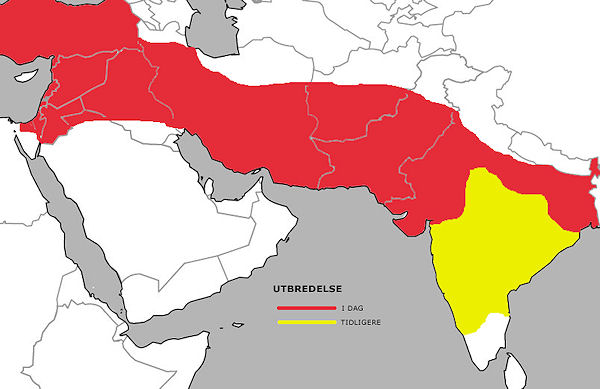

Abb.: Früherer und heutiger (rot) Lebensraum von Canis lupus pallipes Sykes, 1831

- Indischer Wolf - Indian Wolf

[Bildquelel: no.wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Siehe:

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā

/ übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. --

Canis lupus pallipes. -- URL:

http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/canis_lupus_pallipes.htm

|

"This wolf is found throughout the whole of

India, rare in wooded districts, and most abundant in open country.

"The wolves of the Southern Mahratta country," says Mr. Elliot, "generally hunt in packs, and I have seen them in full chase after the

goat antelope (Gazella Bennettii). They likewise steal round a herd

of antelope, and conceal themselves on different sides till an

opportunity offers of seizing one of them unawares, as they approach, whilst

grazing, to one or other of their hidden assailants. On one occasion three

wolves were seen to. chase a herd of gazelles across a ravine in which two

others were lying in wait. They succeeded in seizing a female gazelle,

which was taken from them. They have frequently been seen to course and

run down hares and foxes, and it is a common belief of the Ryots that

in the open plains, where there is no cover or concealment, they scrape

a hole in the earth in which one of the pack lies down, and remains

hid, while the others drive the herd of antelope over him. Their

chief prey, however, is sheep, and the shepherds say that part of the

pack attack and keep the dogs in play, while others carry off their

prey, and that if pursued they follow the same plan, part turning and

checking the dogs, whilst the rest drag away the carcass till they evade

pursuit. Instances are not uncommon of their attacking man. In 1824, upwards of

30 children were devoured by wolves in one pergunnah alone.

Sometimes a large wolf is seen to seek his prey singly. These are

called Won-tola, by the Canarese, and reckoned particularly fierce."

I have found wolves most abundant in the

Deccan and in Central India. I have often chased them for several miles,

they keeping 50 to 100 yards ahead of the horse, and the only kind of

ground on which a horse appeared to gain on them was heavy ploughed land. I

have known wolves turn on dogs that were running at their heels and

pursue them smartly till close up to my horse. A wolf once joined with my

greyhounds in pursuit of a fox, which was luckily killed almost

immediately afterwards, or the wolf might have seized one of the dogs instead of

the fox. He sat down on his haunches about 60 yards off whilst the

dogs were worrying the fox, looking on with great apparent interest, and

was with difficulty driven away. In many parts of the North-west of

India, they are very destructive to children, as about Agra, in Oude,

Rohilcund, and Rajpootana, and rewards are given by Government for their

destruction. Wolves breed in holes in the ground, or caves, having only

three or four young, it is said. The female has ten teats. They are

usually rather silent, but sometimes bark just like a pariah dog. The

howling after their prey, recorded of the European wolf, is seldom heard in India."

[Quelle: Jerdon,

Thomas Claverhill <1811-1872>: The mammals of India : a natural history of

all the animals known to inhabit continental India. -- London, 1874. -- S.

140f.] |

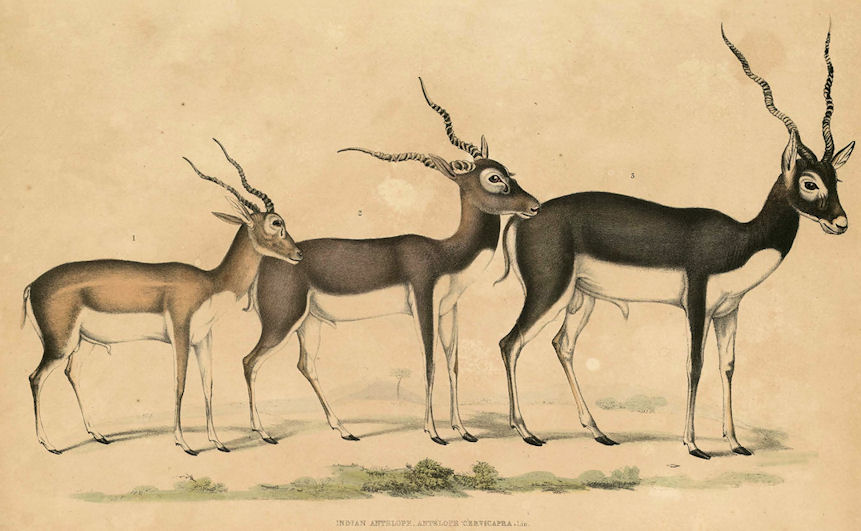

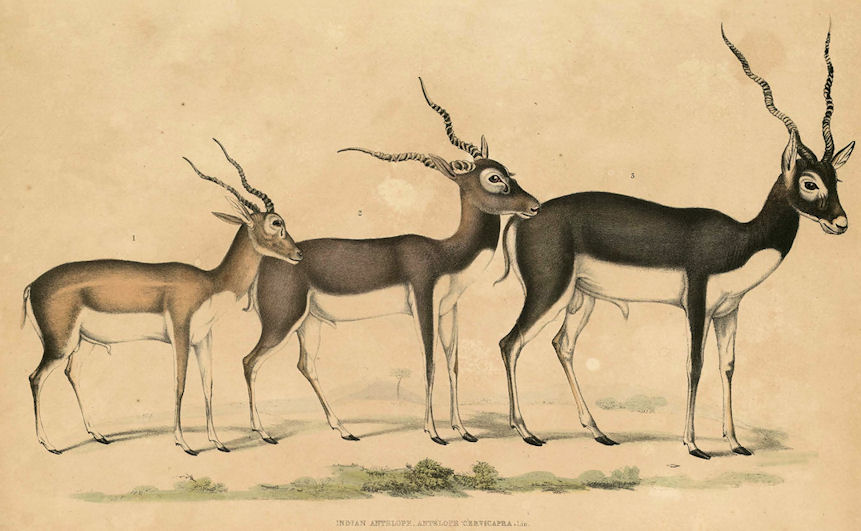

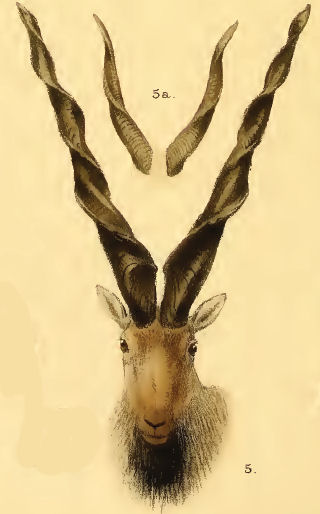

2.9.16. Antilopen und Gazellen

|

8. a./b mṛge kuraṅga-vātāyu-hariṇājinayonayaḥ

मृगे कुरङ्ग-वातायु-हरिणाजिनयोनयः ।८ क।

Bezeichnungen für मृग - mṛga m.: Wild, Hirsch,

Antilope, Gazelle, Moschustier:

- कुरङ्ग - kuraṅga m.: Kuraṅga,

eine Antilopenart oder Antilope überhaupt

- वातायु - vātāyu m.: lebendig wie

der Wind

- हरिण - hariṇa m.: Gelblicher,

Fahler1

- अजिनयोनि m.: Ursprung für Fell,

woraus man Fell bereitet, Fell-Lieferant