|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 12. manuṣyavargaḥ III. (Über Menschen). -- 2. Vers 12 - 22b. (Textilien). -- Fassung vom 2011-03-06. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa4/amara212b.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-03-01

Überarbeitungen: 2011-03-06 [Ergänzungen] ; 2011-03-05 [Ergänzungen]

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

Siehe auch:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 6. Bewegliche Hinterlassenschaften. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen06.htm

Watson, J. Forbes (John Forbes) <1827-1892>: The textile manufactures and the costumes of the people of India <Auszüge> / by John Forbes Watson (1866). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 6. Bewegliche Hinterlassenschaften, 1.). --http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen061.htm

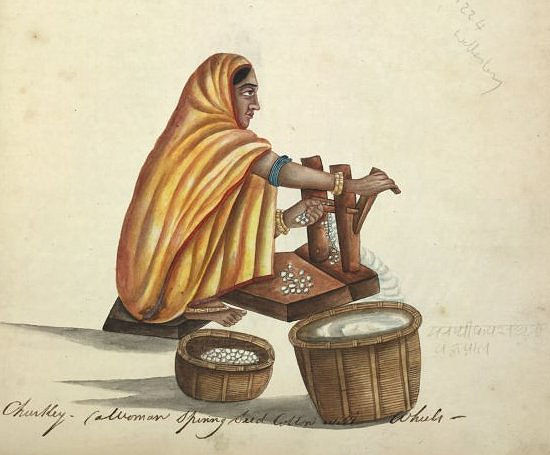

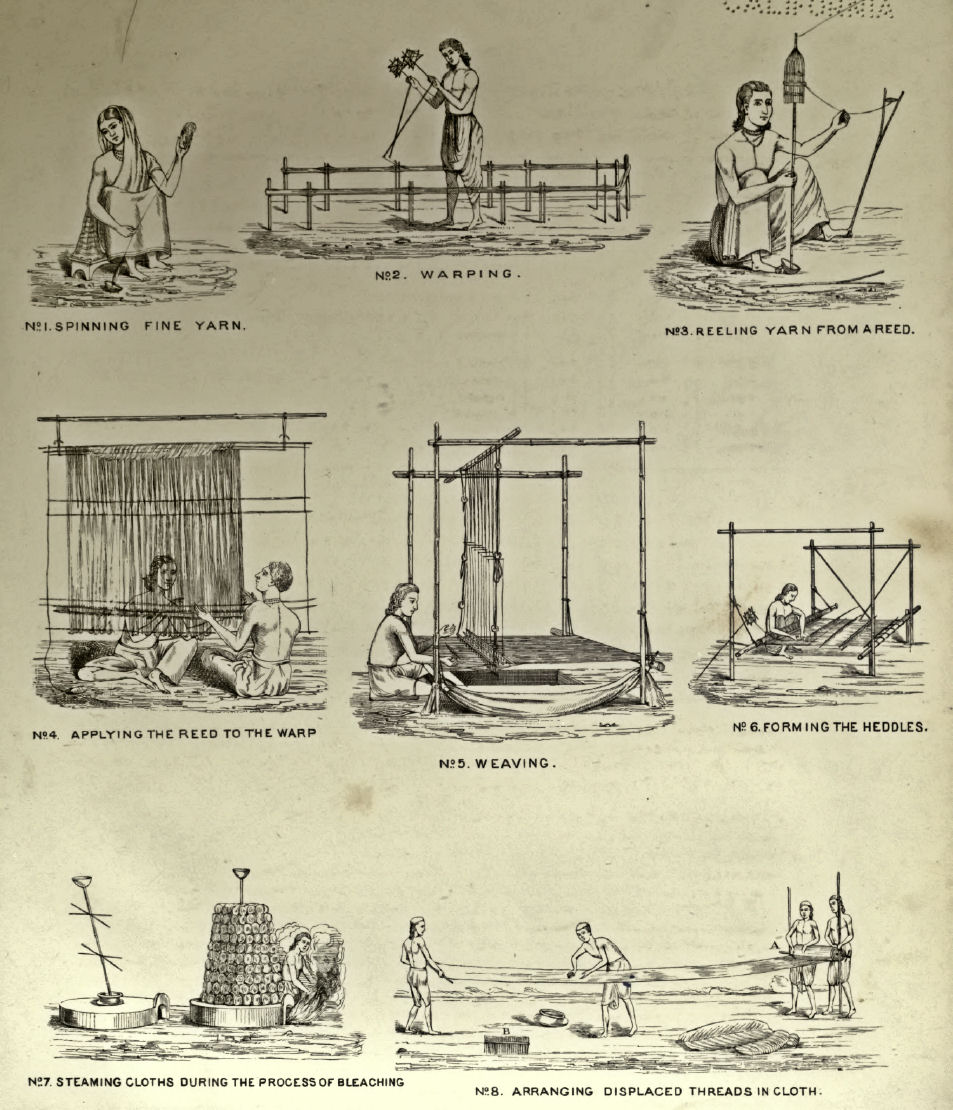

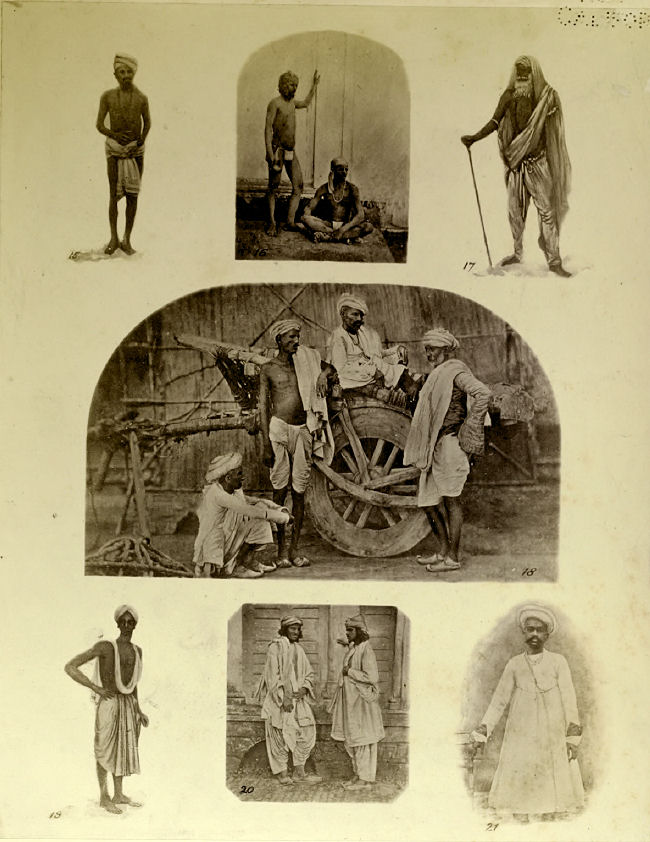

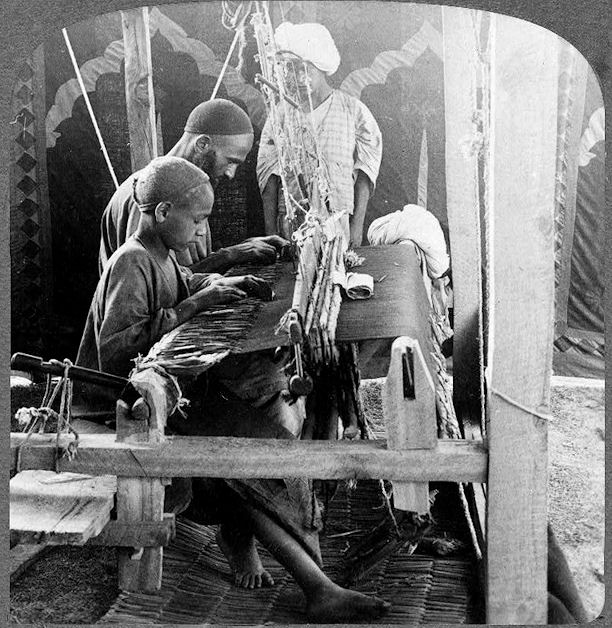

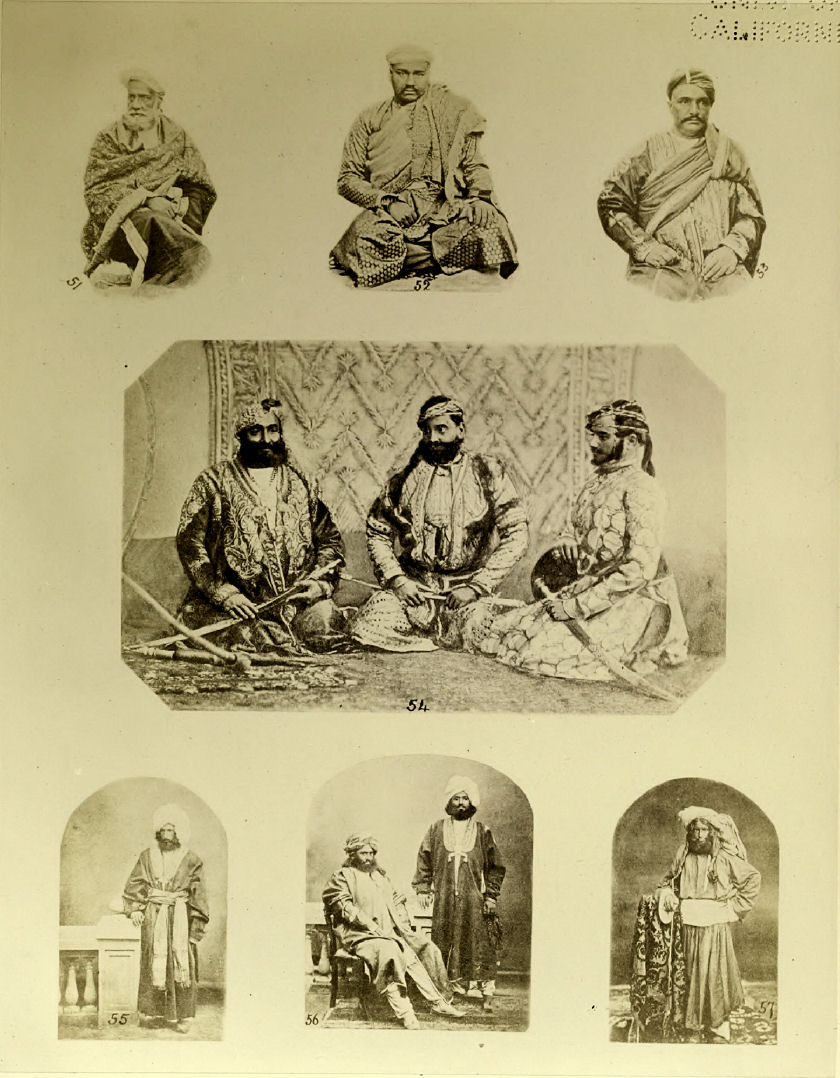

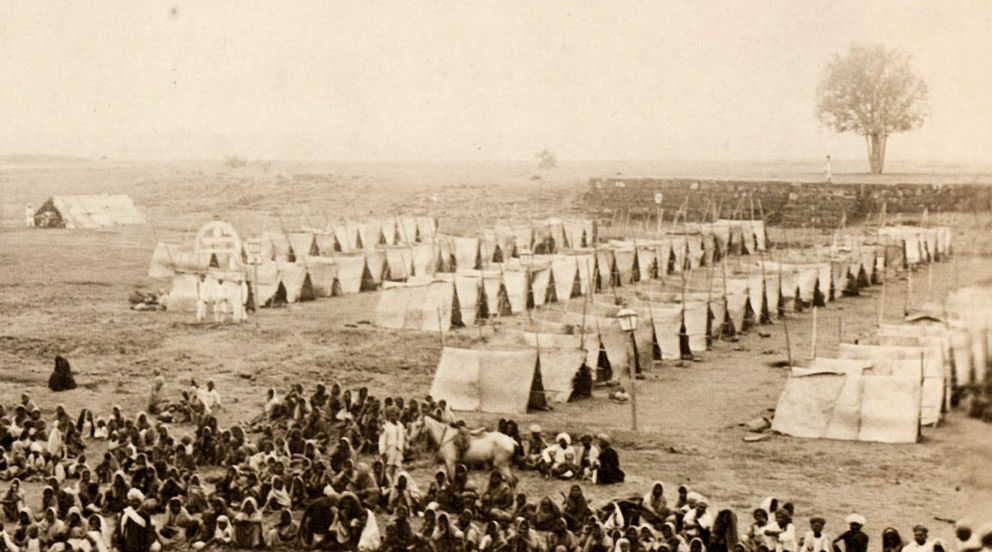

Abb.: Spinnerin und Weber, ca. 1850

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4838539938/. -- Zugriff am

2011-03-05. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

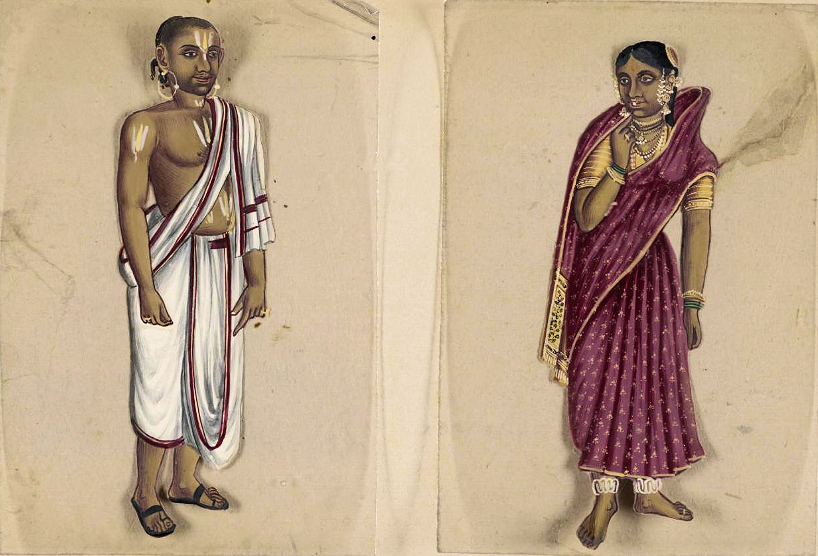

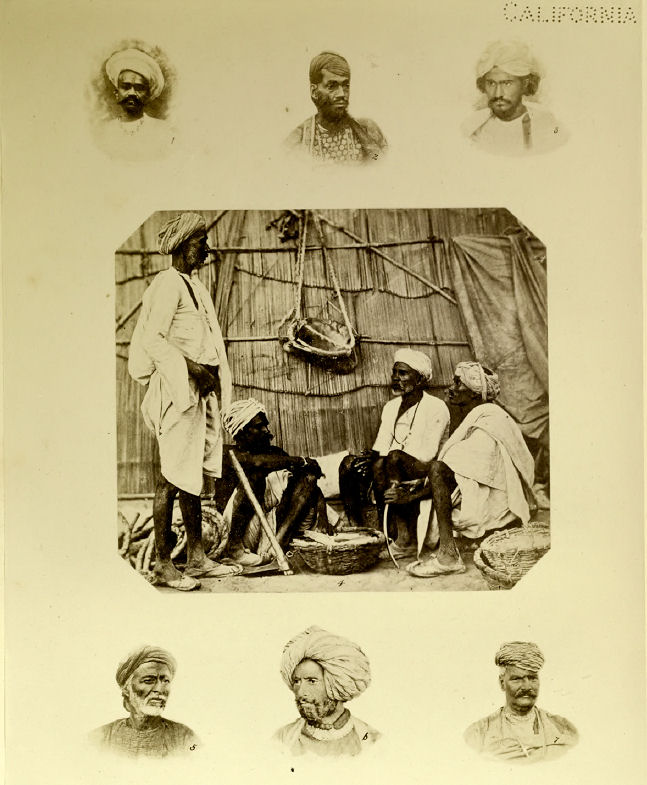

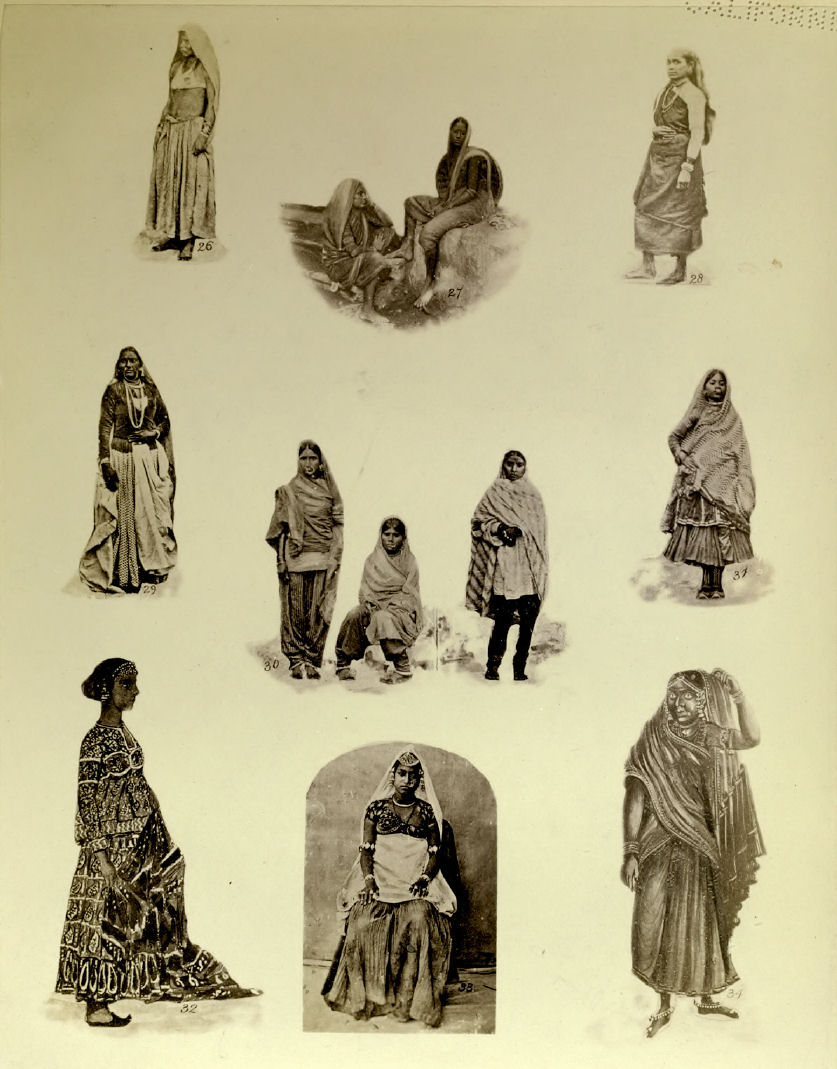

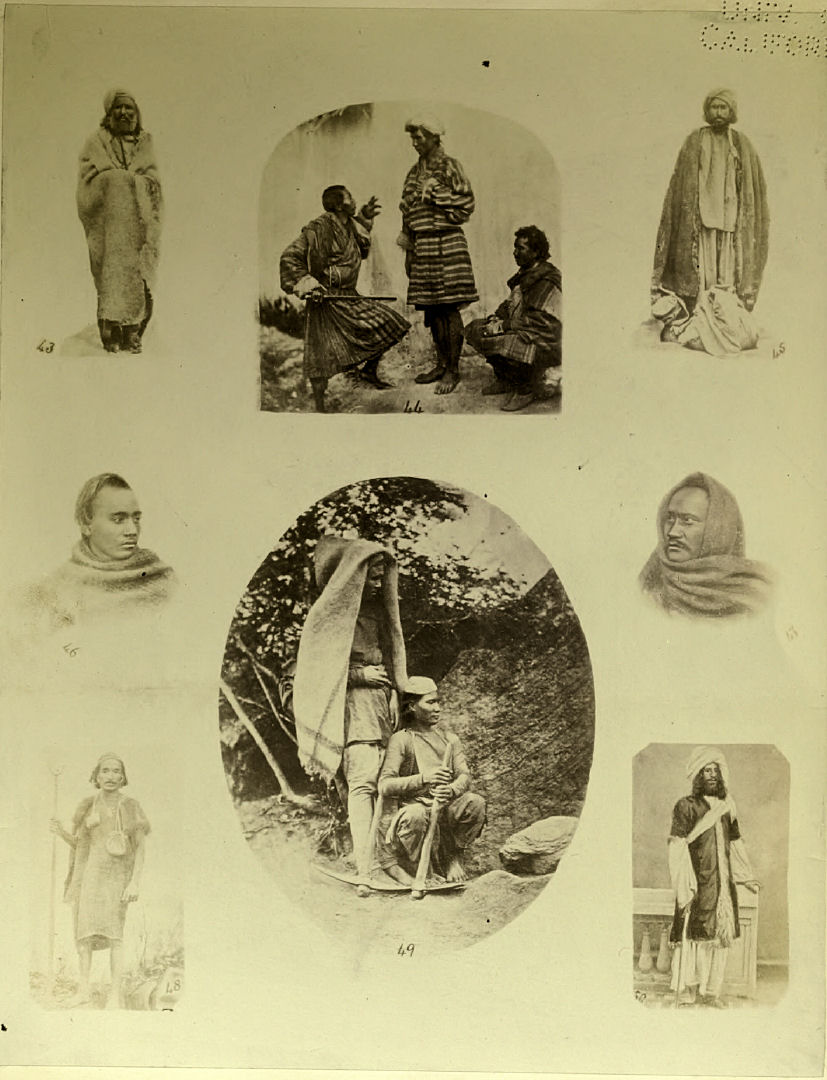

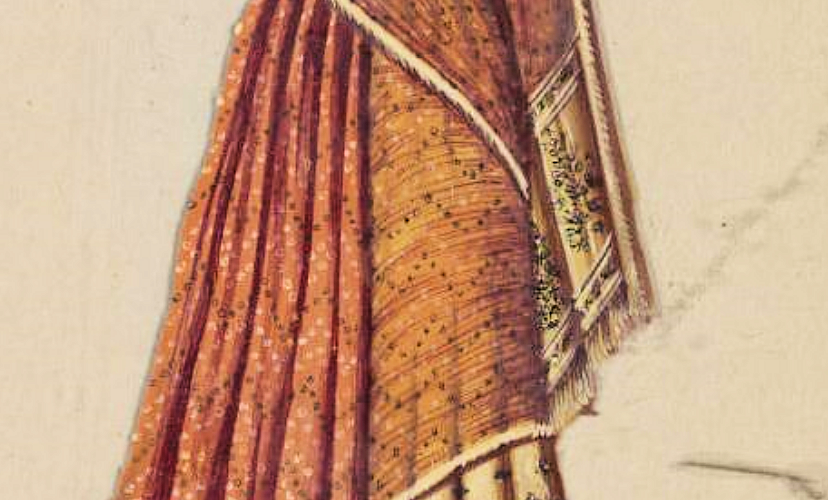

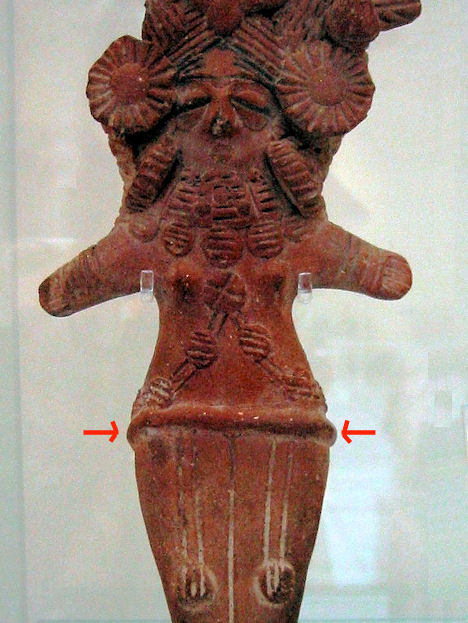

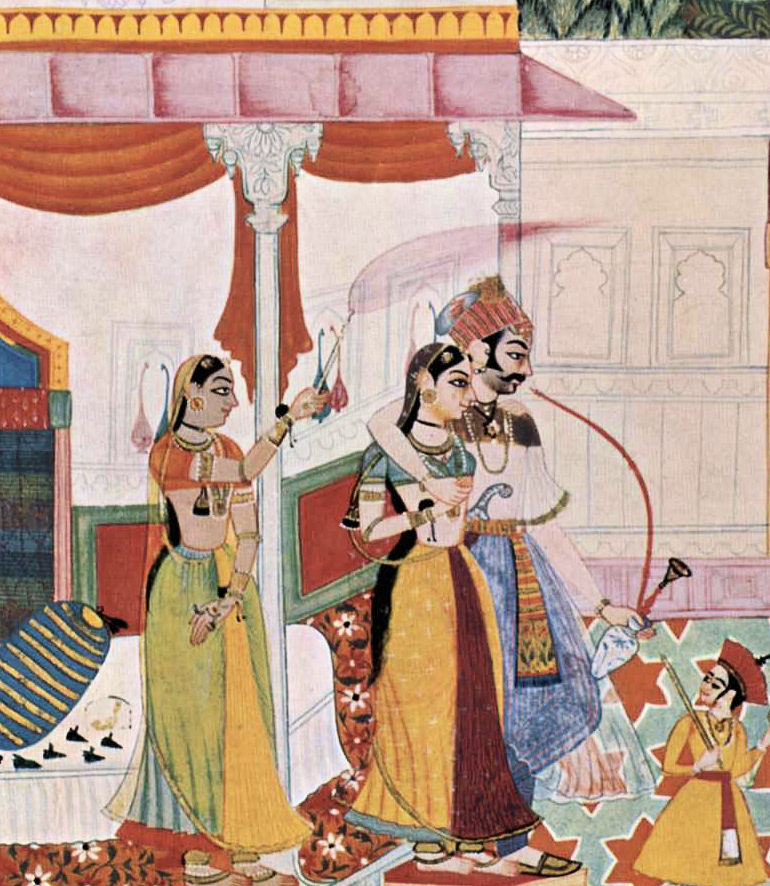

Abb.: Brahmane mit Frau, Shringeri -

ಶೃಂಗೇರಿ,

Karnataka

[Bildquelle: Vardapillai, 1837]

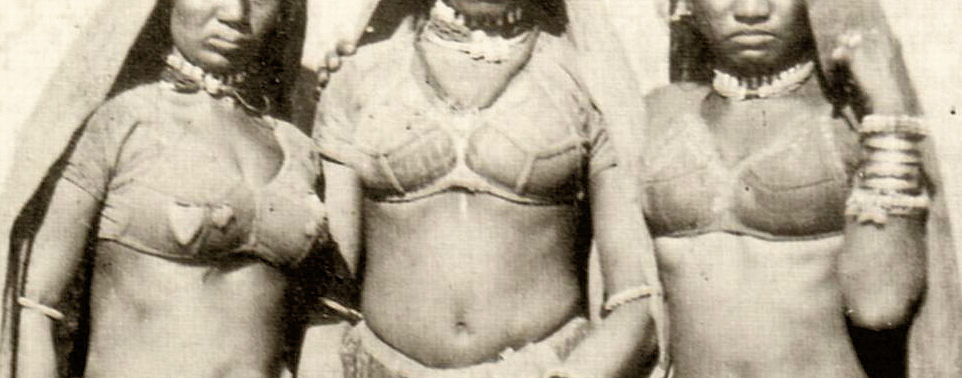

"CLOTHING. The materials used for clothing, and the forms of dress of the peoples of the south and east of Asia, differ according to the climate, the pursuits, and the customs of the races. Through a thousand years, seemingly, the south-eastern races continue to wear clothing similar to what their forefathers put on; but Andamanese live wholly without apparel, and Chinese dress in a very elaborate manner. Hindu men and women, until the middle of the 19th century, wore only cloths without seams ; and even yet their women's bodice (choli) and the men's jacket (angrika) alone are sewed, the lower garment of both sexes being cloths which are wrapped round the limbs, and often as neatly so as sewn trousers. In this form Hindu clothing is not called clothes, but cloths. Most Hindus wear trousers when on horseback; but the prevailing Hindu custom illustrates Mark x. 50, where mention is made of the blind man throwing off his upper garment, which was doubtless a piece of cloth. It is not considered at all indelicate among the Hindu people for a man to appear naked from the head to the waist, and servants thus attired serve at the tables of poor Europeans. In Arabia, a coarse cloak of camel or goat's hair is generally worn, often as the sole attire. It is called an aba, and its material is cameline. Amongst men of the very humblest classes of Southern India, at work, the simple loin-cloth is the sole body clothing; but almost all have a sheet, or a cumbli, or coarse blanket of wool or hair, as a covering for warmth. The Nair women move about with the body uncovered down to the waist, as an indication of the correctness of their conduct. The women of the Patuah or Juanga, in the Denkenāl district of Orissa, also called Patra-Sauri or Leaf-Sauri, till 1871 wore a covering of a bunch of leaves, hanging from the waist, both in front and behind. Forest races in Travancore also wear leaves as covering. Hindu children, both boys and girls, up to three or four years of age, have no clothing ; the Abor young women have a string of shell-shaped embossed bell-metal plates, and Miri women wear a small loin kilt made of cane. Throughout British India, however, almost every Hindu and Mahomedan woman, however humble in circumstances, is wholly covered, from the neck to the ankles, with choli and gown or trousers, or cloths of kinds. This seems to have been the practice from remote antiquity.

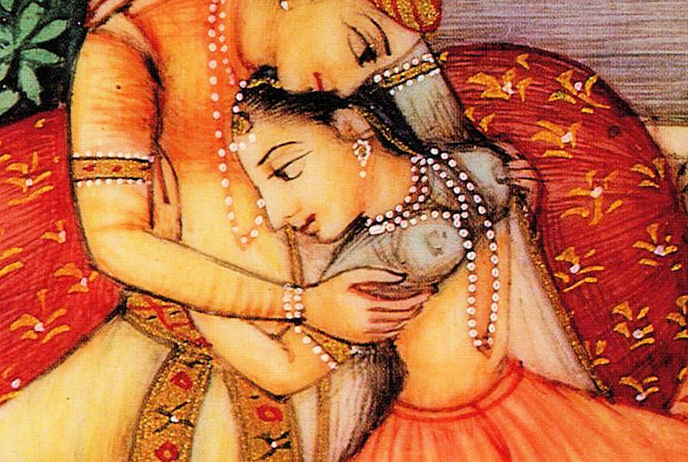

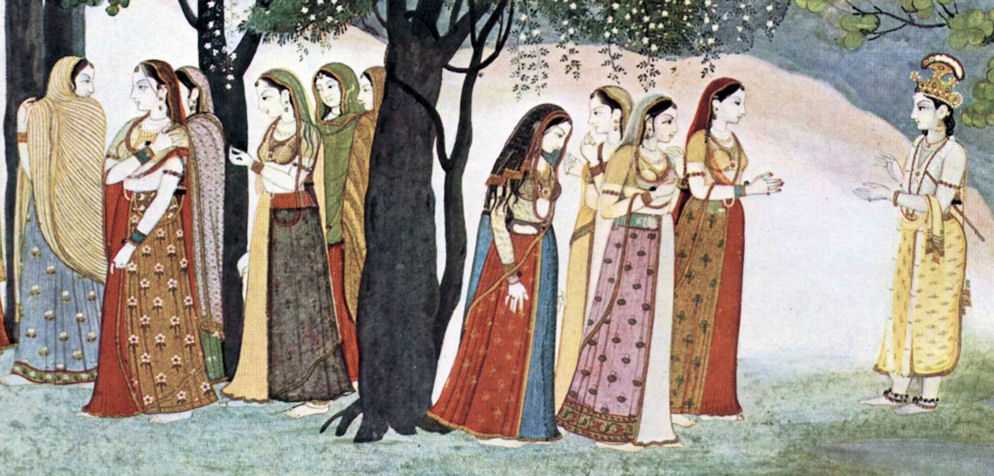

In Vedic times the women seem to have dressed much like the present Rajputni. They had a gogra or petticoat, a kanchali or corset, and a do-patta or scarf. In the Rig Veda there is an allusion to Indrani's headdress as being of all forms, and several passages are indicative of considerable attention having been paid to personal decoration (Calcutta Review, No. 109, p. 30). Weaving is frequently alluded to in the Vedas. The Yajur Veda mentions gold cloth or brocade as in use for a counterpane. In the Ramayana are mentioned the wedding presents to Sita as consisting of woollen stuffs, fine silken vestments of different colours, princely ornaments, and sumptuous carriages.

The Mahabharata mentions furs from the Hindu Kush, woollen shawls of the Abhira of Gujerat, cloths of the wool of sheep and goats, etc. ; and weaving and dyeing are repeatedly mentioned in the Institutes of Menu.

The best representations of ancient costumes in India are the celebrated fresco paintings in the caves of Ajunta, some of which are still very perfect, and in the Buddhist caves of Ellora some paintings in a similar style had been executed. It is difficult to decide the date of these paintings, which represent scenes in Buddhist history ; and the series may extend from the 1st or 2d century before Christ, to the 4th and 6th century of this era. In either case they are upwards of a thousand years old, and as such are of much interest.

One very large picture, covered with figures, represents the coronation of Sinhala, a Buddhist, king. He is seated on a stool or chair, crowned with a tiara of the usual conventional form. Corn, as an emblem of plenty and fertility, is being poured over his shoulder by girls. He is naked from the throat to the waist. All the women are naked to the waist; some of them have the end of the cloth or sari thrown across the bosom, and passing over the left shoulder. Spearmen on foot and on horseback have short waist-cloths only.

In another large picture, full of figures, representing the introduction of Buddhism to Ceylon, and its establishment there, all the figures, male and female, are naked to the waist. Some have waist-cloths or kilts only, others have scarfs, or probably the ends of the dhoti, thrown over their shoulders. Female figures, in different attitudes around, are all naked, but have necklaces, ear-rings, and bracelets, and one a girdle of jewels round her loins.

Some writers have maintained that the ancient Hindus were ignorant of the art of preparing needle-made dresses. It has even been said that there is no word for tailor in the language of the Hindus ; but there are two one, tunnavaya, which applies to darning, and the sauchika, which applies to tailoring in general. The Rig Veda mentions needles and sewing, and the Ramayana and Mahabharata allude to dresses which could not have been made otherwise than with the aid of needles. In the ancient sculptures at Sanchi, Amraoti, and Orissa, several figures are dressed in tunics which required needles. Amongst these garments are discoverable what may be called the ancestors of the modern chapkan and jama. The dress differs so entirely from the chiton, the chlamys, the himation, and such other vestments as the soldiers of Alexander brought to India that they cannot be accepted as Indian modifications of the Grecian dress. In ninny ancient sculptures of Buddhist times, queens, princes, and ladies of the highest rank are represented without any garments ; and it has been suggested that there prevailed either a conventional rule of art, such as has made the sculptors of Europe prefer the nude to the draped figure, or a prevailing desire to display the female contour in all its attractiveness, or the unskilfulness of early art, or the difficulty of chiselling drapery on such coarse materials as were ordinarily accessible in this country, or that a combination of some or all of those causes exercised a more potent influence on the action of the Indian artist than ethnic or social peculiarities in developing the human form in stone.

Allusion is made to 'saffron-tinted robes' and to 'red-dyed garments' in occasional passages of the early writings, but even these are comparatively rare as regards men, and there is little more in respect to women. In the drama of Vikram and Urvasi, written probably in the reign of Vikramaditya, B.C. 56, Puraravas, one of the characters, says of Urvasi, a nymph who has fainted,

'Soft as the flower, the timid heart not soon

Foregoes its fears. The scarf that veils her bosom

Hides not its flutterings, and the panting breast

Seems as it felt the wreath of heavenly blossoms

Weigh too oppressively.'Act i. Sc. 1.

Again,

'In truth she pleases me : thus chastely robed

In modest white, her clustering tresses decked

With sacred flowers alone, her haughty mien

Exchanged for meek devotion. Thus arrayed,

She moves with heightened charms.'Act iii. Sc. 2.

In the drama Mrichchakati, attributed to king Sudraka of Ujjain, who reigned, according to the traditional chronology, in the first century before the Christian era, and is certainly not later than the 2d century after Christ, Act iv. Sc. 2 says,

'Maitrena. Pray who is that gentleman, dressed insilk raiment, glittering with rich ornaments, and rolling about as if his limbs were out of joint ?

'Attendant. That is my lady's brother.

'Maitrena. And pray who is that lady dressed in flowered muslin ? a goodly person, truly,' etc.The following passage, taken from the Uttara Rama Charitra, by the same author, affords an idea of the costume of a warrior race. Janaka, the father of Sita, the heroine, in describing the hero Rama, says,

' You have rightly judged

His birth ; for see, on either shoulder hangs

The martial quiver, and the feathery shafts

Blend with his curling locks. Below his breast,

Slight tinctured with the sacrificial ashes,

The deer-skin wraps his body, with the zone

Of Murva bound ; the madder-tinted garb

Descending vests his limbs ; the sacred rosary

Begirts his wrists ; and in one hand he bears

The pipal staff, the other grasps the bow.

Arundati, whence comes he?'The clothing of the Mahomedan races, who came from the north-west, has been of wool and of cotton, to suit the changing seasons, and the articles of dress were cut out and sewed in forms to fit the body. The Rajput and other martial races have always dressed similarly.

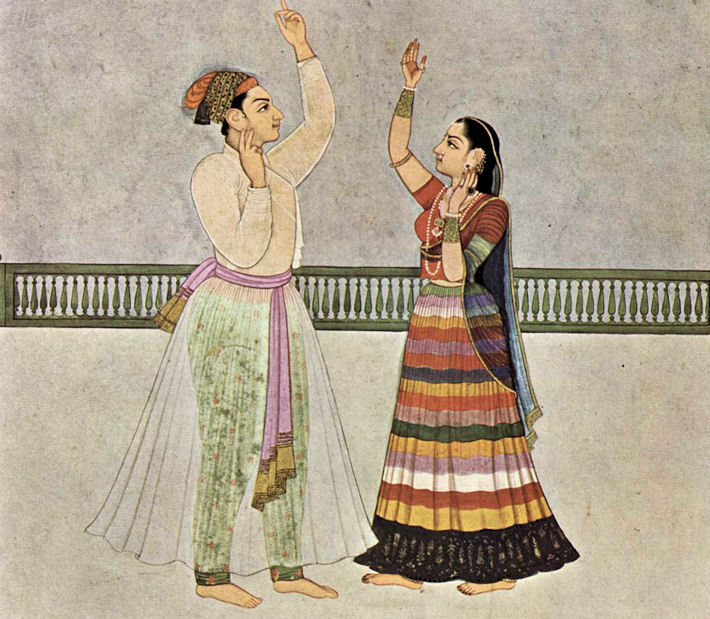

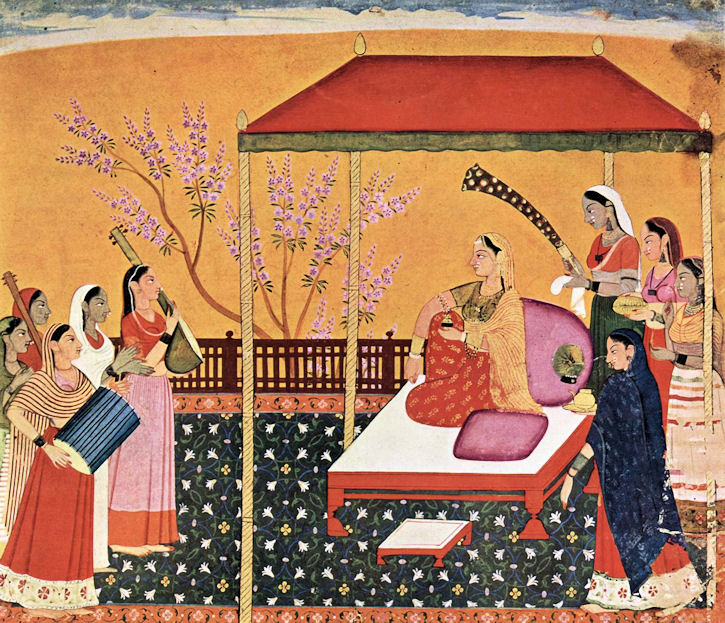

Most of the Hindu women of the present day appear in public, and at their numerous religious festivals opportunities for seeing their holiday clothing are numerous. On such occasions the wealth of the mercantile classes admits of much display. In Bombay, a brilliant and picturesque array of women drifts along the streets and ways. The large and almost bovine Banyan and Bhattia, women roll heavily along, each plump foot and ankle loaded with several pounds' weight of silver. The slender, gold-tinted Purbhu women, with their hair tightly twisted, and a coronal of mogra flowers, have a shrinking grace and delicacy that is very attractive ; and, barring the red Kashmir chadar, their costume is precisely that in which an artist would dress Sakuntala and her playfellows. The Marwari females, with skirts full of plaits, tinkling with hawk-bells, their eyes set in deep black paint, and the sari dragged over the brow so as to hang in front, are very curious figures, seldom pretty. Surati girls, with their drapery so tightly kilted as to show great sweeps of the round, brown limbs, smooth and shapely, that characterize those Venuses of the stable and kitchen, stride merrily along, frequently with a child on their rounded hips. There is a quaint expression of good-humour on their features, which have a comely ugliness unlike that of any other race. Then the trim little Malwen girls, who are already growing fairer and lighter in colour from their confinement in the cotton factories, sling quickly along with a saucy swing of their oscillant hips ; and the longer-robed Ghati, scarcely to be distinguished from women of the Marathi caste, go more demurely. The Brahman woman is best seen at Poona, Wye, and at Nasik. In Bombay she is scarcely distinguishable from Sonar, Sontar, and others. Those odd, gipsy-like wenches, the Wagri beggar women, each provided with a plump baby, carried in a tiny hammock slung on a stick, and handed to the spectator as if it were something to buy or to taste, are to be seen in numbers, sometimes twanging on a one-stringed sitar, but more often playing the tom-tom on their plump forms, with that frank simplicity of pantomime which is the supreme effort of Hindu eloquence, and the art of suiting the action to the word. Gosains, with their little stalls of shells, brass spoons, bells, and images. Everybody very happy, and all differently clad.

In the present day, before a Hindu puts on a new garment, he plucks a few threads out of it and offers them to different deities, and smears a corner with turmeric to avert the evil eye. The cloth of a married Hindu woman has always a border of blue or red, or other colour. The dress of a Hindu widow is white.

Arab (men's) dress has remained almost the same during the lapse of centuries. Over the shirt, in winter or in cool weather, most persons wear sudeyri, a short vest of cloth without sleeves; kaftan, or kuftan of striped silk, of cotton or silk, descending to the ankles, with long sleeves extending a few inches beyond the finger-ends, but divided from a point a little above the wrist or about the middle of the forearm. The ordinary outer robe is a long cloth coat of any colour, called by the Egyptians gibbeh, but by the Turks jubbeh, the sleeves of which reach not quite to the wrist. Some persons also wear a beneesh or benish robe of cloth, with long sleeves, like those of the kuftan, but more ample. It is properly a robe of ceremony, and should be worn over the other cloth coat, but many persons wear it instead of the gibbeh. The Farageeyeh robe nearly resembles the beneesh ; it has very long sleeves, but these are not slit, and it is chiefly worn by men of the learned professions. In cold weather, a kind of black woollen cloak, called abayeh, is commonly worn. Sometimes this is drawn over the head. The abayeh is often of the brown and white striped kind.

In British India the ordinary articles of clothing of Hindu and Mahomedan women comprise the bodice, called choli, angia, kachuri, koortee, and kupissa; the petticoat, called lahunga, luhinga, ghagra, and peshgir; and the sari, or wrapping loin-cloth.

Men's clothing consists of

Loin-cloth, dhoti or loongi ;

Trousers, called paijama, izar, turwar, gurgi, and shalwar ;

Jacket, coat, and vest, called anga, angarka, chapkan, dagla, jora, koorta, kuba, kufcha, mina, mirzai, jama, labada ;

Skull-cap, topi, taj ;

Head-dress, pagri, turban (sir-band), sbumla or shawl turban, rumal or kerchief, dastar;

Kamrband or waist-belt, sash.The women of Burma wear a neat cloth bodice, and, as an under garment, a cloth wrapped tightly round from the waist downwards ; but so narrow that it opens at every step, and all the inner left thigh is seen.

Fabrics used for the clothing of the masses of the people of India are plain and striped dooria, mulmul, aghabani, and other figured fabrics have established themselves ; the finest qualities of muslins must necessarily be confined to very rich purchasers.

Long cloths or panjams of various qualities were formerly manufactured to a great extent in the Northern Circars, as well as in other parts ; the great proportion consisted of 14 panjam or cloths containing fourteen times 12 threads in the breadth, which varied according to local custom from 38 to 44 inches. 14 Ibs. was considered the proper weight of such cloths, the length 36 cubits, half-lengths being exported under the denomination of salampores. The manufacture of the finer cloths, which went up to and even exceeded 50 panjam, has long been discontinued.

Other articles of dress of women of Bombay are the bungur-kuddee, chikhee, choli or khun, choonee or head-cloth, doorungu-pytanee, guj (covering for breast), guzzee or long robe, izarband, kempchunder (widows), kurch-chunderkulee, peshgir, paijama, saris of kinds, silaree.

In Cutch, the khombee, sadlo, for women ; for men, pairahan, paijama, izarband.

Other articles of dress of the men of Bombay, angarka, chaga, dhoti, izarband, koortah, labada (in Baluchistan), pairahan, paijama, turban, ujruk or coloured sheet (in Sind).

Men's Cloths are manufactured all over British India, and those of the Madura district have lace borders ; they are sold as high as 70 rupees for a suit of two pieces. Conjeveram is noted for its silk-bordered cloths, which are sold for not more than 15 rupees a pair.

Women's Cloths of cotton form an article of manufacture in every district. Madras manufactures a nicely coloured women's cloth called oolloor sailay, sold for 7 rupees and upwards. Arnee is noted for its manufacture of a superior quality of white cotton cloths of various patterns. Those of Sydapet, in the outskirts of Madras, are of ordinary quality, and of different colours. Ganjam also fabricates a common sort, with a few of more value worked with lace borders, but not sold for more than 50 rupees.

Women's Silk Cloths. The principal places for the manufacture of native female silk cloths are the towns of Benares, Berhampore, and Tanjore. Those of Benares are generally of superior quality, with rich lace borders, and they are sold at from 50 to 350 rupees or upwards. Berhampore cloths are wholly silk, but nicely finished. Tanjore cloths are also neatly finished, with nicely-worked borders, both of lace and silk, of various colours ; they are sold at from 15 to 150 rupees.

Silk Cloths, called pethambaram, are chiefly brought from Benares and Nagpur ; they are also made at the town of Combaconum. The Benares cloths are highly prized for their superior quality ; they measure 12 by 2 cubits a-piece ; two pieces make one suit of an upper and under garment. Hindus wear these cloths during their devotions and holiday time. They are sold from 50 to 350 rupees, or even more. The silk fabrics of Combaconum are good, although not equal to those of Benares.

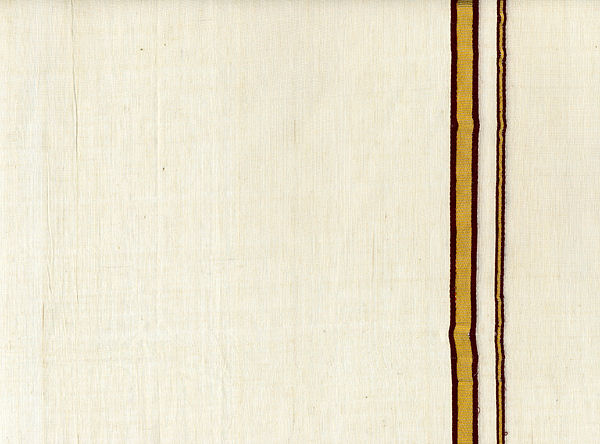

White Cloths were manufactured all over Southern India, but those of Manamadu, in the district of Trichinopoly, were very superior in quality, and used by the more respectable of the inhabitants as clothing, under the name of Manamadu sullah. That at Arnee, in the district of Chingleput, known as Arnee sullah, is of different quality.

Women's coloured cotton Cloths. These coloured cotton cloths are largely made in the Madura district. They are of various sizes, with or without lace-worked borders. Those with lace vary in price from 15 to 200 rupees each ; they are generally purchased by the wealthier natives, by whom they are highly prized. These fabrics are known in the market as vaukey, thomboo, joonnady, and ambooresa, all of them lace-bordered.

Women's silk Cloths are made chiefly in Benares and Nagpur ; but they are fabricated also at Berhampore, Tanjore, Combaconum, and Conjeveram, in the Madras Presidency. Those of Benares and of the Mahratta countries are celebrated for their superiority, and are highly prized for their lace borders ; their size is 16 by 2 cubits, and they are sold at 50 to 300 rupees and upwards ; those made at Berhampore, Tanjore, and Combaconum are not equal to the Benares cloths, but are well made, and sold at from 15 to 70 rupees each. The women's cloths of Tanjore and Madura manufacture, and men's head-cloths, also from Madura, will compete with the production of any other loom in the world.

Printed Cloths are worn occasionally, as in Berar and Bundelkhand, for sarees ; and the ends and borders have peculiar local patterns. There is also a class of prints on coarse cloth, used for the skirts or petticoats of women of some of the humbler classes in Upper India ; but the greatest demand for printed cloths is for palempores, or single quilts.

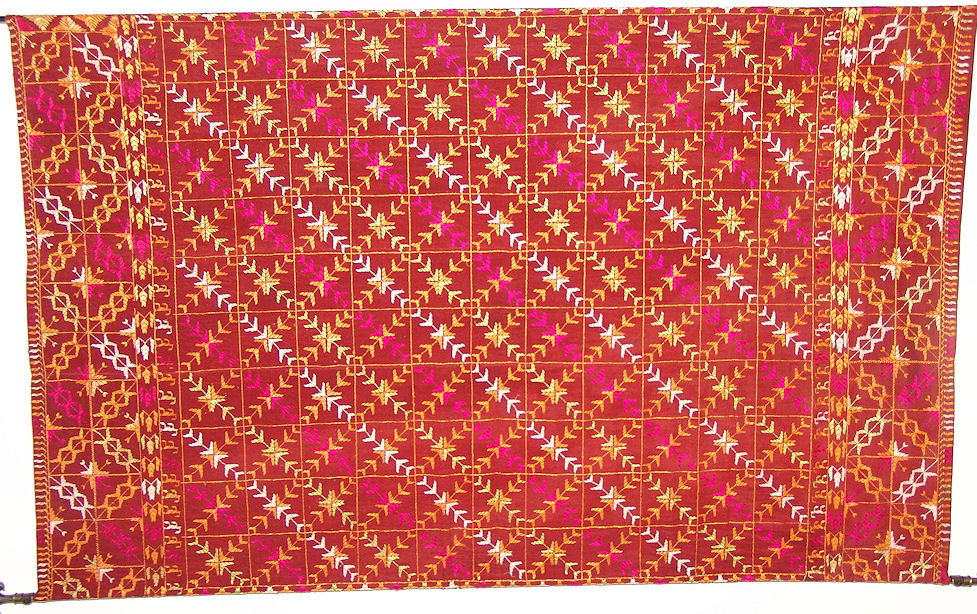

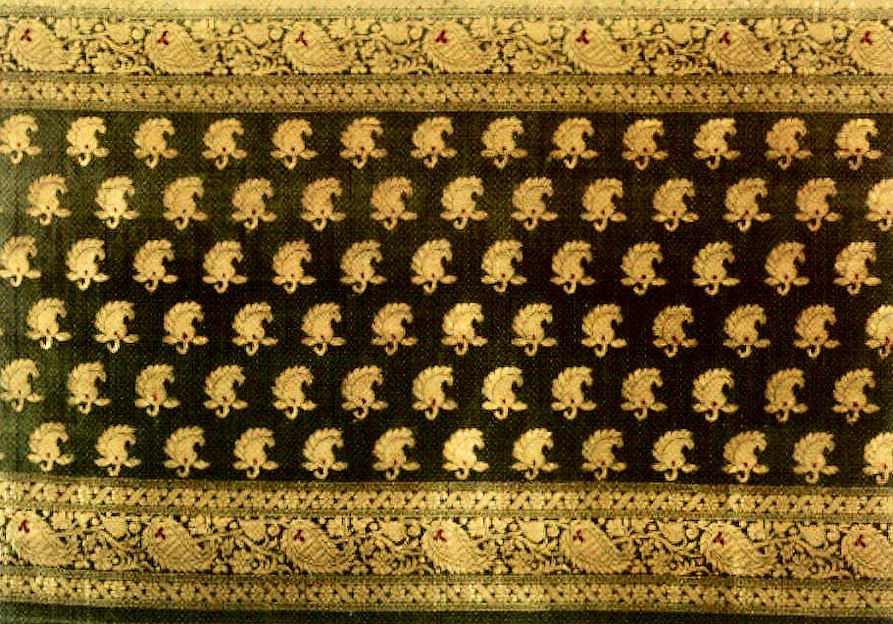

In the costlier Garment Cloths woven in India, the borders and ends are entirely of gold thread and silk, the former predominating. Many of the saree or women's cloths, those made at Benares, Pytun, and Burhanpur, in Gujerat, at Narrainpet and D,hbanwarum, in the territory of His Highness the Nizam, at Yeokla in Kandesh, and in other localities, have gold thread in broad and narrow stripes alternating with silk or muslin. Gold flowers, checks, or zigzag patterns are used, the colours of the grounds being green, black, violet, crimson, purple, and grey; and in silk, black shot with crimson or yellow, crimson with green, blue, or white, yellow with deep crimson and blue, all producing rich, harmonious, and even gorgeous effects, but without the least appearance of, or approach to, glaring colour, or offence to the most critical taste. They are colours and effects which suit the dark or fair complexions of the people of the country ; for an Indian lady who can afford to be choice in the selection of her wardrobe, is as particular as to what will suit her especial colour dark or comparatively fair as any lady of Britain or France.

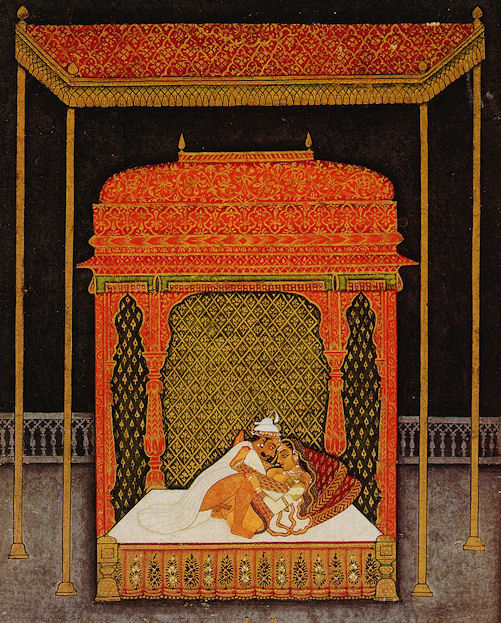

Another exquisitely beautiful article of Indian costume for men and women, is the do-patta scarf, worn more frequently by Mahomedan women than Hindu, and by the latter only when they have adopted the Mahomedan lunga or petticoat ; but invariably by men in dress costume. By women this is generally passed once round the waist over the petticoat or trousers, thence across the bosom and over the left shoulder and head ; by men, across the chest only. Do-pattas, especially those of Benares, are perhaps the most exquisitely beautiful and prized of all the ornamental fabrics of India ; and it is quite impossible to describe the effects of gold and silver thread, of the most delicate and ductile description imaginable, woven in broad, rich borders, and profusion of gold and silver flowers, or the elegance and intricacy of most of the arabesque patterns, of the ribbon borders, or broad stripes. How such articles are woven with their exquisite finish and strength, fine as their quality is, in the rude handlooms of the country, it is hard to understand. All these fabrics are of the most delicate and delightful colours, the creamy white, and shades of pink, yellow, green, mauve, violet, and blue, are clear yet subdued, and always accord with the thread used, and the style of ornamentation, whether in gold or silver, or both combined. Many are of more decided colours, black, scarlet, and crimson, chocolate, dark green, and madder ; but whatever the colour may be, the ornamentation is chaste and suitable. For the most part, the fabrics of Benares are not intended for ordinary washing ; but the dyers and scourers of India have a process by which the former colour can be discharged from the fabric, and it can then be re-dyed. The gold or silver work is also carefully pressed and ironed, and the piece is restored, if not to its original beauty, at least to a very wearable condition. The do-pattas of Pytun, and indeed most others except Benares, are of a stronger fabric. Many of them are woven in fast colours, and the gold thread silver is rarely used in them is more substantial than that of Benares. On this account they are preferred in Central India and the Dekhan, not only because they are ordinarily more durable, but because they bear washing or cleaning better. In point of delicate beauty, however, if not of richness, they are not comparable with the fabrics of Benares.

Scarfs are in use by every one, plain muslins, or muslins with figured fields and borders without colour, plain fields of muslin with narrow edging of coloured silk or cotton (avoiding gold thread), and narrow ends. Such articles, called sehla in India, are in everyday use among millions of Hindus and Mahomedans, men and women. They are always open-textured muslins, and the quality ranges from very ordinary yarn to that of the finest Dacca fibres.

The texture of the dhotees, sarees, and loongees manufactured in Britain and sent to India, is not that required by the people, nor what they are accustomed to. It is in general too close, too much like calico, in fact, which of course makes the garment hot, heavy in wear, and difficult to wash. Again, the surface becomes rough, and, as it is generally called, fuzzy in use, while the native fabric remains free.

Few native women of any class or degree wear white ; if they do wear it, the dress has broad borders and ends. But all classes wear coloured cloths, black, red, blue, occasionally orange and green, violet and grey. All through Western, Central, and Southern India, sarees are striped and checked in an infinite variety of patterns. Narrainpet, Dhanwar, and Muktul, in the Nizam's territories ; Gudduk and Bettigerry in Dharwar ; Kolhapur, Nasik, Yeokla, and many other manufacturing towns in the Dekhan ; Arnee in the south, and elsewhere, send out articles of excellent texture, with beautifully-arranged colours and patterns, both in stripes and checks. For the costly and superb fabrics of cloths of gold and silver (kimkhab), and the classes of washing satins (mushroo and hemroo), even if European skill could imitate them by the bandloom, it would be impossible to obtain the gold and silver thread unless it were imported from India. The native mode of making this thread is known, but the result achieved by the Indian workman is simply the effect of skilful delicate manipulation. The gold and silver cloths (kimkhab) are used for state dresses and trousers, the latter by men and women ; and ladies of rank usually possess petticoats or skirts of these gorgeous fabrics. Mushroo and hemroo are not used for tunics, but for men's and women's trousers, and women's skirts ; as also for covering bedding and pillows. They are very strong and durable fabrics, wash well, and preserve their colour, however long worn or roughly used ; but they can hardly be compared with English satins, which, however, if more delicate in colour and texture, are unfitted for the purposes to which the Indian fabrics are applied. For example, a labada or dressing gown made of scarlet mushroo in 1842, had been washed over and over again, and subjected to all kinds of rough usage, yet the satin remained still unfrayed, and the colour and gloss as bright as ever.

Many of the borders of loongees, dhotees, and sarees are like plain silk ribbons, in some instances corded or ribbed, in others flat. The saree, boonee, bafta, jore, ekpatta, gomcha, etc. of Dacca, have latterly been made of imported British yarn. Fabrics of a mixed texture of cotton and silk, are in Dacca designated by various names, as nowbuttee, kutan, roomee, apjoola, and lucka ; and when embroidered with the needle, as many of them frequently are, they are called kusheeda.

The silk used in their manufacture is the indigenous muga silk of Assam and Sylhet, but the cotton thread employed was lately almost entirely British yarn, of qualities varying from Nos. 30 to 80. These cloths are made exclusively for the Jedda and Bussora markets, and a considerable stock is yearly imported in the Arab vessels that trade between Calcutta and these ports. Pilgrims, too, from the vicinity of Dacca, not unfrequently take an investment of them, which they dispose of at the great annual fair held at Meena, near Mecca. They are used by the Arabs chiefly for turbans and gowns. The golden colour of the muga silk gives to some of these cloths a rich lustrous appearance ; pieces made of native-spun cotton threads and of the best kind of muga silk, are admired.

The export trade of the Madras Presidency in madapollams and long cloths has been annihilated by the goods laid down by the British manufacturers in all the bazars of India.

The dress of Hindu men is of white muslin or cotton cloth, and their upper coat is now generally sewed. The under garment for the lower part of the body, the do-wati or dhoti, is a loose unsewed wrapper or Cloth. Hindu women of all classes mostly wear unsewed Cloths of green, red, or yellow-coloured cotton, edged with silk or gold embroidery, and a bodice of cotton or silk.

The dress of the Bhattia men consists of a jama or tunic of white cloth or chintz, reaching to the knee ; the kamrband or cincture, tied so high as to present no appearance of waist ; trousers very loose, and in many folds, drawn tight at the ankle ; and a turban, generally of a scarlet colour, rising conically full a foot from the head. A dagger, shield, and sword complete the dress. The Bhattiani wears a fine woollen brilliant red gogra or petticoat, and scarf thirty feet in width. They also wear the chaori, or rings of ivory or deer-horn, which cover their arms from the shoulder to the wrist, of value from sixteen to thirty-five rupees a set ; and silver kurri (massive rings or anklets) are worn by all classes, who deny themselves the necessaries of life until they attain this ornament.

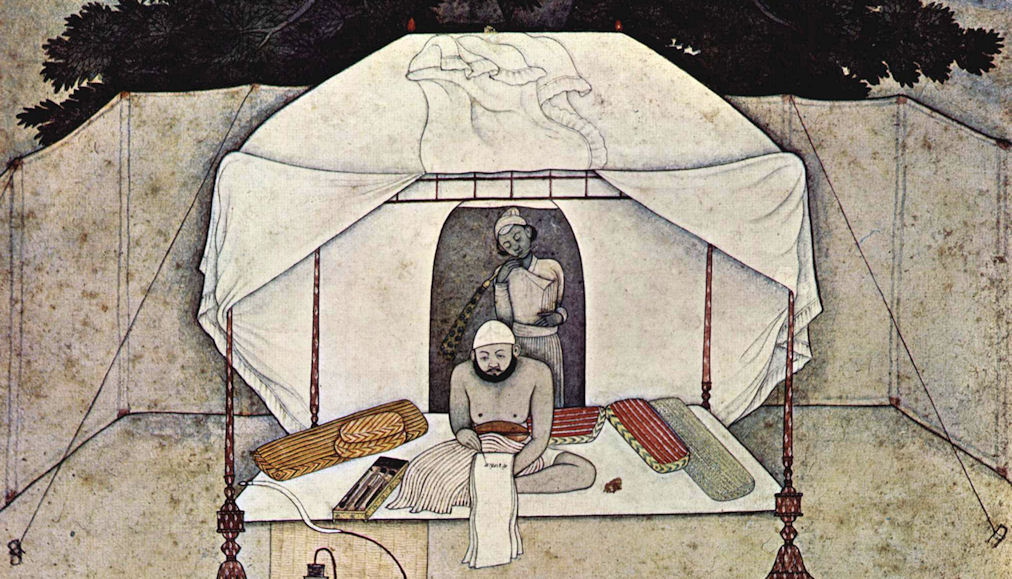

John xix. 23 says, 'Without seam, woven from the top throughout ;' and the clothes of a Hindu, who is not employed in the service of Europeans or Muhammadans, are always without a seam ; have neither buttons nor strings, being merely cloths wrapped round the upper and lower parts of the body. A Brahman, strict in his religious observances, would, not on any account put on clothes which had been in the hands of a Muhammadan tailor.

The angarkha or undress coat, and the jama or dress coat, are worn only by men.

The anga is a sleeveless vest.

Buchhanee, in Dharwar, is commonly worn as a waist-cloth by children of respectable people ; also worn by adults of the same class while sleeping. Price one rupee two annas.

Chādar is a sheet. A chādar made to the order of Kunde Rao, the Gaekwar of Baroda, for a covering of the tomb of Mahomed at Medina, cost a kror of rupees. It was composed entirely of inwrought pearls and precious stones, disposed in an arabesque pattern. The effect was highly harmonious.

Chanduse, a cotton scarf, coloured border and ends, used in Khyrpur.

The Choli or bodice of women is of silk or cotton, and is usually fastened in front. Many women of Gujerat also wear a gown. The choli is an under-jacket worn by women. The thans or choli pieces of Dharwar, of a description used by women working in the fields, cost three annas for each choli, or twelve annas the piece.

Cumbli are blankets of goats' hair or wool. Every labouring family in the Peninsula has them. They cost from one to three rupees.

Kamrbanda are sashes worn by men. They are of cotton and of silk.

The Dhotee, a flowing cloth for the body, from the waist to the feet, is worn by men, and is generally bordered with red, blue, or green, like the toga praetexta (limbo purpureo circumdata). Dhotees are usually worn so as to fall over and cover the greater portion of the lower limbs. One of a coarse cotton, commonly worn by cultivators and labourers in the field, may cost about two rupees.

Izarband is of silk or cotton, and is a tie for trousers.

Khess, a chintz scarf in use in Hyderabad (Sind).

Labada, a dressing-gown.

Loongee, or scarf of cotton, of silk, and of silk and cotton, is worn by men. Where of silk, it is usually enriched with a border of gold and silver.

Mundasa, a cloth worn by the poorer classes in Dharwar ; costs 1 1/4 rupees.

The Paijama, or trousers, is worn both by men and women.

Panchrangi of Dharwar has a warp of silk and weft of cotton, worn ordinarily by dancing women, not considered proper for respectable women; 1 than, 1 rupee 12 annas.

Panjee of Dharwar is a cloth used by well-to-do people to dry themselves after bathing, but also worn as a waist-cloth by poor people.

Patso of Burma is a cloth worn by men of all classes. In Akyab it is worn by the Mug race.

Pitambara means clothed in yellow garments. Hindu hermits, and many of the Hindu and Buddhist ascetics, are required to wear clothes dyed of an ochrey yellow.

The Rumal or kerchief, the kamrband or waistbelt, and the do-patta or sash, are men's garments.

Salendong, a silk scarf of Singapore.

Salimote, a silk scarf of Singapore.

Saree, the Hindu woman'slower cloth, costs from two rupees and upwards. Each woman generally has a new one once a year. It is often used also as an upper garment, in the form of a scarf for enveloping the person, one end being usually brought over the head as a covering. The saree, as used by women to cover the whole body, is the kalumma of Homer.

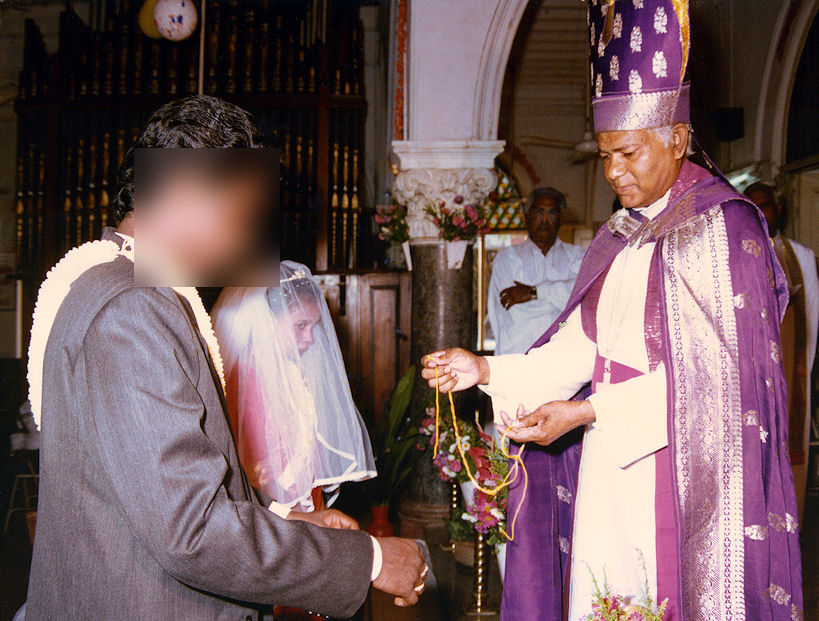

Selya, in the south of India, is a sheet or body covering in use amongst the poorer classes, cultivators, and labourers, wrapped round their shoulders and body when employed in the fields. Their usual cost is about 1 1/4 to 1 3/4 rupees. In Dharwar one is always presented to the bridegroom by the relations of the bride, together with a turban.

Turbans of all kinds are worn by Hindus and Mahomedans, and known as dastar, pagri, turban being from the Persian words, Sir-band, headbinder. The Arabs and Turks call it Imamah. The other head-dresses are the rumal, the taj, and the topi. Ward, Hindus, iii. 186 ; Drs. Taylor and Watson, Ex. of 1862; Calcutta Review ; Pioneer Newspaper.

CLOTHS manufactured in India :

Cotton fabrics of Bombay comprise the bafta, bochun, carpet, chadar, chael, chandni, choli, do-patta, dhota, dhoti, dungaree, dustoorkhana, horni, khes, khoji, khurwa a coarse red cloth, kurchar, loongee, mussoti, pagga, peshgir, phatka, pichore, quilt or razai, rumal, saree, soussee, soot, soojunee, tablecloths, table napkins, towels, turbans.

Silk fabrics of Bombay are, bochun, bulbuls, cholepun, doorungee- ytanee, gul-badan, gown pieces, hemroo, karrah, katchia, khun, khudruf, kootnee, kud, kunawaz, meenia-sari, mukhmul, petambar-zanani, petambar-mardana, paijama, rowa, rumal, senna, shalwar, tasta, uddrussa, yeolah.

Silk and cotton made fabrics of Bombay are the dariyai-sari, ghaut, khunjree, lake, lake-meenia, loongi, luppa, with silk and gold and silver embroidery, mukhtiar-khunee, meenia-ghaut, mushroo.

Bhangarah, a very coarse and strong sackcloth, made from the inner bark of trees, and much used in Nepal as grain sacks.

Bhim Poga of Nepal, a fabric, half woollen, half cotton.

Changa, a coarse cotton cloth manufactured by the natives of Newar.

Chintz (Chinti, HIND., a drop) or pintado, printed calicoes.

Dalmiyan, or net.

Dariyai, plain silk.

Deogun, a coarse cloth of silk, with gilt tissue.

Elaicha, a fabric of mixed cotton and silk.

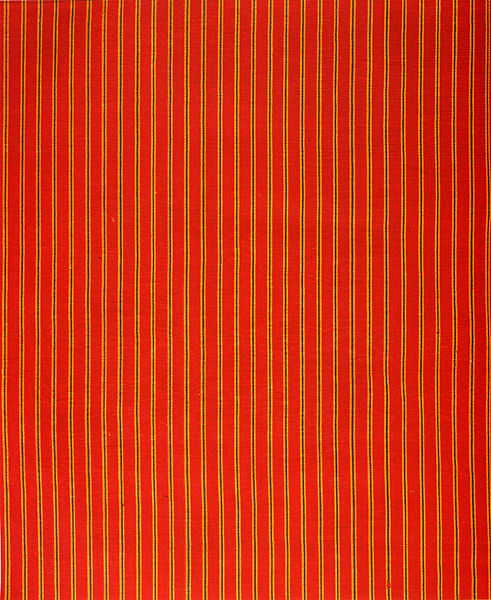

Susi and Khesi, striped calico, woven with coloured thread. The silken khesi is also edged with gold or silver.

Kashidas-tussur, embroidered muslins made at Dacca, and largely sold in India, Persia, Arabia, Egypt, and Turkey.

Kassa, a Newar imitation of the Indian malmal, used for turbans.

Khadi, a coarse cotton cloth.

Kurchar, felt for pillows.

Kimkhab, or gold and silver brocaded silk ; a silk brocade. The kimkhab brocades are distinguished as suneri or golden ; ruperi or silvery ; chand-tara, moon and starry ; dup-chan, sunshine and shade ; maz-char, ripples of silver ; palimtarakshi, pigeons' eyes; bulbul-chasm, nightingale eyes ; mohr-gala, peacock's neck ; par-i-taos, peacocks' feathers.

Malida, red woollen cloth, woven like shawl cloth.

Mushroo, a fabric of cotton mixed with silk, with a cotton warp or back, and woof of soft silk in a striped pattern, having the lustre of satin or atlas.

Muslins, the finest or malmal-i-kbas of Dacca were known as ab-rawan, running water ; baft-howa, woven air ; shabnam, evening dew. Malmal-i-khas means special (king's) muslin. Doria or striped muslin. Charkhana or chequered muslin. Jamdani or figured muslin. Chikan or embroidered muslin.

Mundel, a cloth of cotton and gold, obtainable in Kutch ; costs Rs. 8.4.11.

Nimbu, a woollen pile fabric.

Palampore (palang-posh), or bed- covers.

Panchau, white woollen cloth.

Pankhi, woollen twill.

Paranda, a silk material used as a hair ornament in Lahore.

Pashmina, or woollen fabrics.

Punika of Nepal, an imitation of the Dinapur tablecloth.

Purbi-khadi, a coarse cotton cloth manufactured by the Khassya hill tribes (Purbi, eastern).

Putasi, a blue and white check worn by Newar women.

Sianah, a woollen stuff of Nepal.

Sufi is the striped (gulbadan) silks, called also Shuja khani of Bahawulpur. They differ from mushroo in having no satiny lustre, and look like a glazed calico. They can scarcely be distinguished from sufi, and are glazed with a mucilaginous emulsion of quince seed. Mushroo and sufi are made plain, striped, and figured.

Tafta, a fabric of twisted thread.

Tappu, coarse cotton cloth of Nepal.

Tasar, Tussar, Tassah, eria and munga, are made of wild silks.

Tusa, a coarse woollen fabric."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 744 - 749]

| 12a./b. tvak-phala-kṛmi-romāṇi vastrayonir daśa triṣu त्वक्-फल-कृमि-रोमाणि वस्त्रयोनिर् दश त्रिषु ।१२ क। Rohstoffe für Kleidung (वस्त्र - vastra n.: Kleidung, Stoff) sind:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Materials of coth. Of four kinds: 1st. bark of plants, as Rushy Crotalaria, Linum, hemp, hibiscus, &c. 2d. fruit, viz. cotton ; 3d. insects, viz. silk; 4th. hair and wool."

Amara nennt keine Blattfasern.

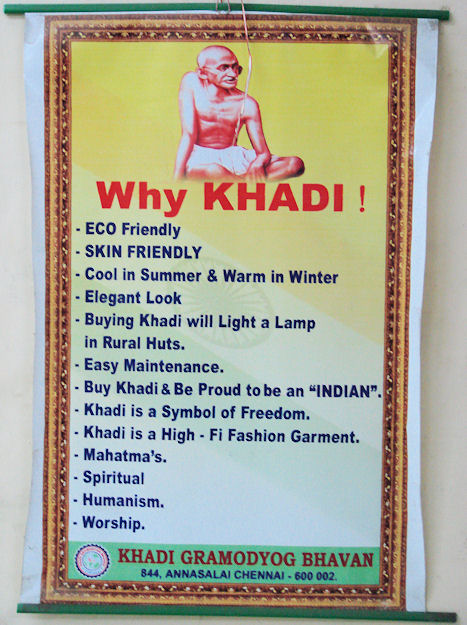

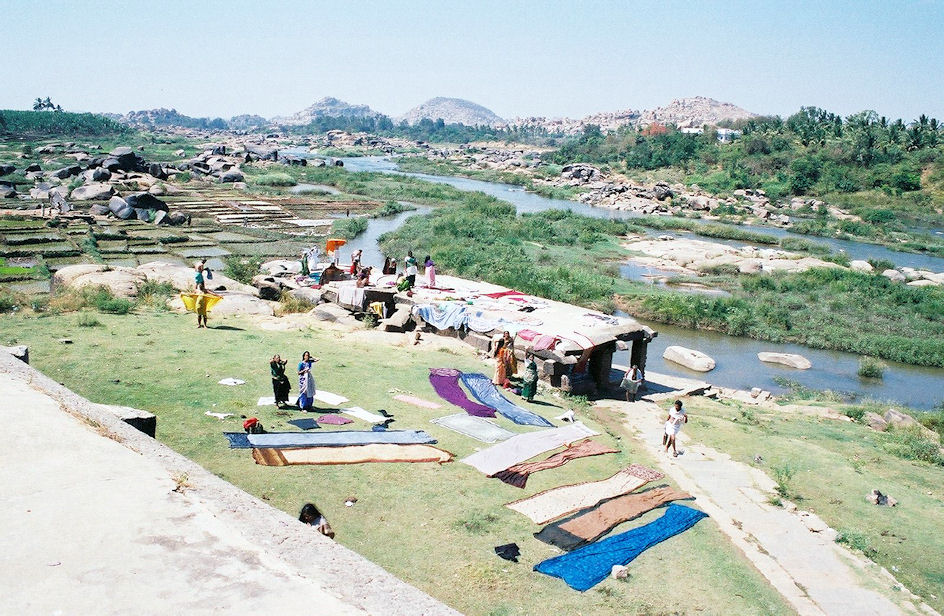

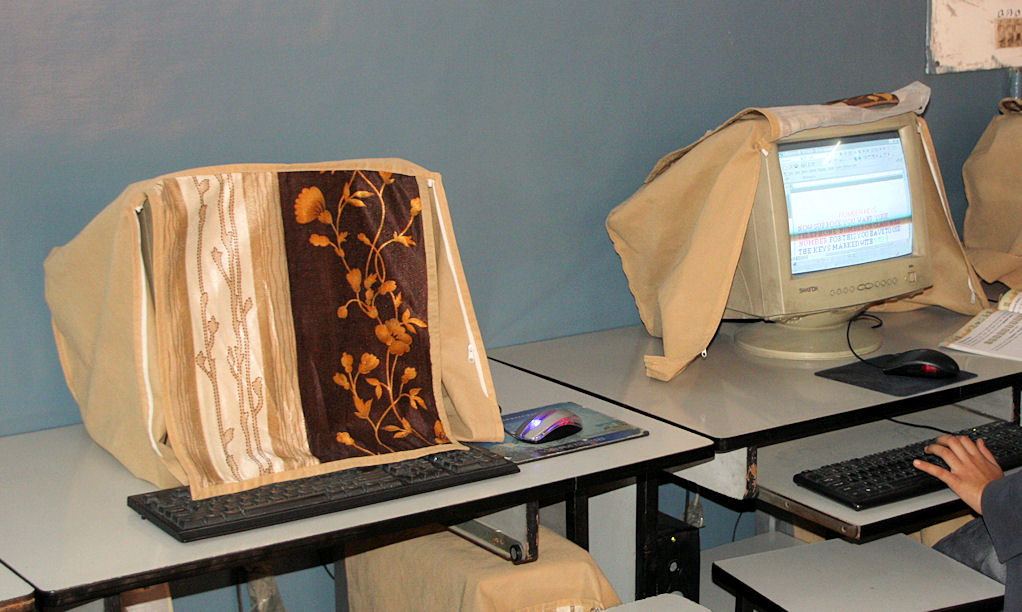

Abb.: वस्त्रयोनिः । Reklame für khadi - खादी, handgesponnenen und

handgewebte Stoffe (ursprünglich nur Baumwolle, heute auch Seide und Wolle),

Chennai - சென்னை,

Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: Erin. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/-erin/2006590366/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-24. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

| 12. tvak-phala-kṛmi-romāṇi vastrayonir daśa triṣu vālkaṃ kṣaumādi phālaṃ tu kārpāsaṃ bādaraṃ ca tat

त्वक्-फल-कृमि-रोमाणि वस्त्रयोनिर्

दश त्रिषु । Die folgenden 10 Wörter kommen in den drei grammatischen Geschlechtern vor, d.h. sind Adjektive. वाल्क - vālka 3: von Bast stammend, aus Bastfasern bestehend, sind Flachsstoffe (क्षौम - kṣauma n.: Flachsstoff, Leinen) und Ähnliches1 |

Colebrooke (1807): "The ten following terms (Some say elevem, others say ten omitting two intermediate compound terms;) admit the three genders. Made of bark. As linen, &c."

1 "und Ähnliches": z.B.

क्सौम - kṣauma n.: Leinen; Rohstoff: क्षुमा - kṣumā f.: Linum usitatissimum L. 1753 - Saat-Lein - Common Flax

Abb.: क्षुमा । Linum usitatissimum L. 1753 - Saat-Lein - Common

Flax

[Bildquelle: Sten Porse / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

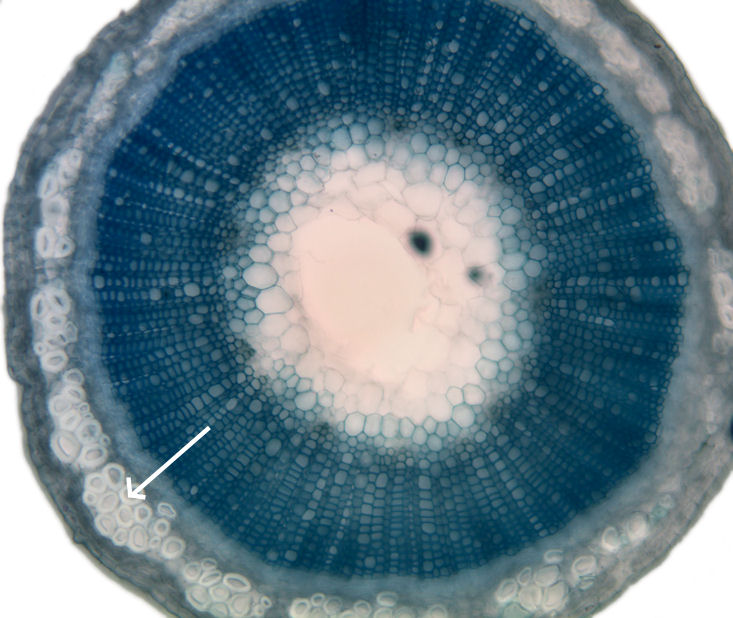

Abb.: क्षुमा । Mikroskopischer Querschnitt durch Lein-Stängel: Pfeil:

Bastfasern

[Bildquelle: Ryan R. McKenzie / Wikimedia. --- Public domain]

Abb.: क्षुमा । Flachs-Stroh

[Bildquelle: Florian Gerlach (Nawaro) / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: क्षुमा । Flachsfaser (von Linum usitatissimum L. 1753 -

Saat-Lein - Common Flax)

[Bildquelle: Elke Wetzig / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: क्सौमम् । Leinengewebe, Ägypten, 2. Jhdt. v. Chr.

[Bildquelle: feministjulie /

Julie. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/juliepics/3249948398/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

"Linum usitatissimum (Linn.) N. O. Linaceae. Common Flax [...]

Description.—Annual, erect, glabrous; [...] flowers blue.

Fl. Dec.—Feb.

W. & A. Prod. i. 134—Roxb, Fl. Ind. ii. 100.

Neilgherries. Cultivated in Northern India.

[...]

Economic Uses.—The native country of the flax-plant is unknown, though it has been considered as indigenous to Central Asia, from whence it has spread to Europe, as well as to the surrounding Oriental countries. For centuries it has been cultivated in India, though, strange to say, for its seeds alone ; whereas in Europe it is chiefly sown for the sake of its fibres. The best flax comes from Russia, Belgium, and of late years from Ireland, where it has been cultivated with the greatest success. Much attention has lately been directed to the sowing of the flax-plant in India for the sake of the fibres; and although the experiments hitherto made have not in every case met with that success which was anticipated, yet there seems little reason to doubt that when the causes of the failure are well ascertained, and the apparent difficulties overcome, that flax will be as profitably cultivated on the continent of India as it is in Europe; while European cultivators must eventually supersede the ryots, whose obstinate prejudice to the introduction of novelty is fatal to any improvement at their hands.

As their object is solely to plant for the seeds alone, they generally mix the latter with other crops, usually mustard, a system which could never be persisted in when the object is for fibres. Among those parts of India where flax has best succeeded may be mentioned the Saugor and Nerbudda territories, Burdwan and Jubbul- pore. In the former districts especially the rich soil and temperate climate are peculiarly favourable for its growth. In the Punjaub also its cultivation has been attended with the most successful results, as appears from the report of Dr Jamieson, who says: "For some years I have been cultivating flax on a small scale, from seeds procured from Russia, and its fibres have been pronounced by parties in Calcutta of a very superior description. There is nothing to prevent this country from supplying both flax and hemp on a vast scale. In the Punjaub thousands of acres are available; and from the means of producing both flax and hemp, this part of India will always be able to compete with other countries." In the Madras Presidency it has been grown with the best results on the Neil- gherries and Shevaroy Hills, near Salem ; and it would probably succeed equally well wherever the temperature is low, accompanied with considerable moisture in the atmosphere. The chief reason of the failures of the crops in Bengal and Behar was owing to the want of sufficient moisture after the cessation of the rains during the growth of the plant. In the Bombay Presidency it has been grown for the seeds alone. In India the time of sowing is the autumn. The soil should be of that character which retains its moisture, though not in an excessive degree. If not rich, manure must be amply supplied, and the plant kept free from all weeds. The best seeds procurable should be selected, of which the Dutch and American are reckoned superior for this country. Dr Roxburgh was the first who attempted the cultivation of flax in India. In the early part of this century he had an experimental farm in the neighbourhood of Calcutta. Since his day the improvements which hare taken place, resulting from extended observation and experience, have of course been very great, and specimens of flax which have been sent from Calcutta to the United Kingdom have been valued at rates varying from £30 to £60 a-ton.

The following information on the mode of the culture of flax in India is selected from a report made by Mr Denreef, a Belgian farmer, whose practical experience in this country enabled him to be a correct judge, and whose report is printed entire in the Journal of the Agri-Horticultural Society of Bengal. Such portions of land as are annually renewed by the overflowing of the Ganges, or which are fresh and rich, are the best adapted for the cultivation of flax.

After the earth has been turned up twice or thrice with the Indian plough, it must be rolled; because without the aid of the roller the large clods cannot be reduced, and the land rendered fine enough to receive the seed. The employment of the roller, both before and after sowing, hardens the surface of the earth, by which the moisture of the soil is better preserved, and more sheltered from the heat of the sun. About and near Calcutta, where manure can be obtained in great abundance for the trouble of collecting it, flax may be produced of as good a quality as in any part of Europe.

Manure is the mainspring of cultivation. It would certainly be the better, if the earth be well manured, to sow first of all either Sunn (Indian hemp), or hemp, or rice, or any other rainy-season crop; and when this has been reaped, then to sow the flax. The tillage of the land by means of the spade (mamoty) used by the natives (a method which is far preferable to the labour of the plough), with a little manure and watering at proper seasons, will yield double the produce obtainable from land tilled without manure and irrigation.

The proper time to sow the flax in India is from the beginning of October until the 20th of November, according to the state of the soiL The culture must be performed, if possible, some time before the soiL The flax which I have sown in November was generally much finer and much longer than that sown in the former month, which I attributed to the greater fall of dew during the time it was growing. The quantity of country seed required to the Bengal beega is twenty seers, but only fifteen seers of the foreign seed, because it is much smaller and produces larger stalks. The latter should be preferred; it is not only more productive in flax, but, owing to the tenderness of its stalks, it can be dressed much more easily.

The flax must be pulled up by the roots before it is ripe, and while the outer bark is in a state of fusibility. This is easily known by the lower part of the stalks becoming yellow; the fusion or disappearing of the outer bark is effected during the steeping, which may be fixed according to the temperature; say, in December at six days, in January five, in February four days, and less time during the hot season. The steeping is made a day after the pulling, when the seed is separated, and then the stalks are loosely bound in small sheaves, in the same way as the Sunn, The Indians understand this business very well, but in taking the flax out of the water it should be handled softly and with great care, on account of the tenderness of its fibres. When it is newly taken out, it should be left on the side of the steeping-pit for four hours, or until the draining of its water has ceased. It is then spread out with the root-ends even turned once, and when dry it is fit for dressing or to be stapled.

To save the seed, the capsules, after they are separated from the stalks, should be put in heaps to ferment from twenty-four to thirty hours, and then dried slowly in the sun to acquire their ripeness.

When flax is cultivated for the seed alone, the country flax should be preferred. Six seers per beega are sufficient for the sowing. It should be sown very early in October, and taken up, a little before perfect ripeness, by its roots, separately, when it is mixed with mustard seeds: the flax seed, being intended for the purpose of drying oil, is greatly injured by being mixed with mustard seed, by which mixture its drying qualities are much deteriorated.

The oil which is procured from the seeds, and known as Linseed oil, is obtained in two ways—either cold drawn, when it is of a pale colour, or by the application of heat at a temperature of not less than 200°. This latter is of a deeper yellow or brownish colour, and is disagreeable in its odour. One bushel of East Indian seeds will yield 14f lb. of oil; of English seeds, from 10 to 12 lb. Nearly 100,000 quarters of seeds are annually exported to Great Britain for the sake of the oil they contain. Great quantities are also shipped from Bombay, where the plant is cultivated for the sake of its seeds alone. The export of linseed from Bombay, says Dr Royle, is now estimated at an annual value of four lacs of rupees.—Simmonds. Ainslie. Lindley."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

Rohstoff: शणपुष्पी - śaṇapuṣpī f.: Crotalaria juncea L. 1753 - Sunhemp

Abb.: शणपुष्पी । Crotalaria juncea L. 1753 -

Sunhemp

[Bildquelle: Roxburgh. -- Vol II. -- 1798. -- Tab. 193. -- Image

courtesy Missouri Botanical Garden.

http://www.botanicus.org. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

"Crotalaria juncea (Linn.) N. O. Leguminosae. Sun-hemp plant [...]

Description.—Small plant, 4-8 feet, erect, branched, more or less clothed with shining silky pubescence or hairs; [...]

Fl. Nov.—Jan.

W. & A. Prod. i. 185.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii. 259.—Cor. ii t. 193.

C. Benghalensis, Lam.

C. tenuifolia, Roxb.

C. fenestrata, Sims. Bot. Mag.

Peninsula. Malabar. BengaL

Economic Uses.—This plant is extensively cultivated for the sake of its fibres in many parts of India, especially in Mysore and the Deccan. These are known by different names, according to the localities where they are prepared. In some places the fibre is known as the Madras hemp or Indian hemp, but this latter appellation is incorrect. It is the Wuckoo-nar of Travancore, the Sunn of Bengal, and so on. The mode of preparation differs from that of other fibres in one particular especially, the plant being pulled up by the roots, and not cut. After the seeds are beaten out, the stems are immersed in running water for five days or more, and the fibres are then separated by the fingers, which process makes it somewhat expensive to prepare. Dr Gibson asserts that the crops repay the labour bestowed on them, as the plant is suited for almost any soil. When properly prepared, the fibres are strong and much valued in the home markets. In this country they are used for fishing-nets, cordage, canvas, paper, gunny-bags, &c. &c.—the latter name being derived from the word Gfoni, the native name for the fibre on the Coromandel coast In the 'Report on the Fibres of S. India' it is stated that the fibre makes excellent twine for nets, ropes, and various other similar articles. The fibres are much stronger if left in salt water. They will take tar easily, and with careful preparation the plant yields foss and hemp of excellent quality. It is greatly cultivated in Mysore, and also in Rajahmundry. In the latter district it is a dry crop, planted in November and cut in March. The yellow flowers resemble those of Spanish broom. It requires manure, but not too much moisture. Samples of the Sunn fibre were sent to the Great Exhibition, and also to the Madras Exhibition of 1855. On those forwarded to England Mr Dickson reported that these fibres will at all times command a market (when properly prepared) at £45 to £50 a-ton, for twine or common purposes; and when prepared in England with the patent liquid, they become so soft, fine, and white, as to bear comparison with flax, and to be superior to Russian flax for fine spinning. In the latter state it is valued at £80 a-ton. In several parts of India the price varies from R. 1 to Rs. 2-8 per maund; in Calcutta, about Rs. 5 per maund—and the prices both in the latter place and Bombay are gradually increasing. By experiments made on the strength of the fibre, it broke at 407 lb. in one instance. Large quantities are shipped for the English market. What is known as Jubbulpore hemp is the produce of C. tenuifolia, which, according to Wight, is a mere variety of C. juncea. Royle, however, and other botanists, think that it is a distinct plant. It is said to yield a very strong fibre, but probably not very different from the Sunn.—Boyle. Jury Reports. Report on Fibres of S. India."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

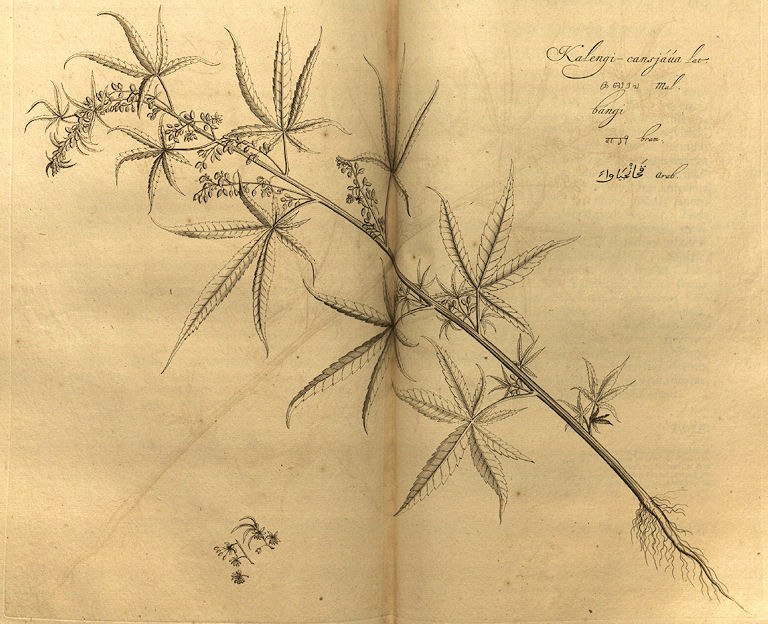

शाण - śāṇa m: Hanfstoff; Rohstoff: शण - śaṇa m.: Cannabis sativa L. 1753 - Hanf - Hemp

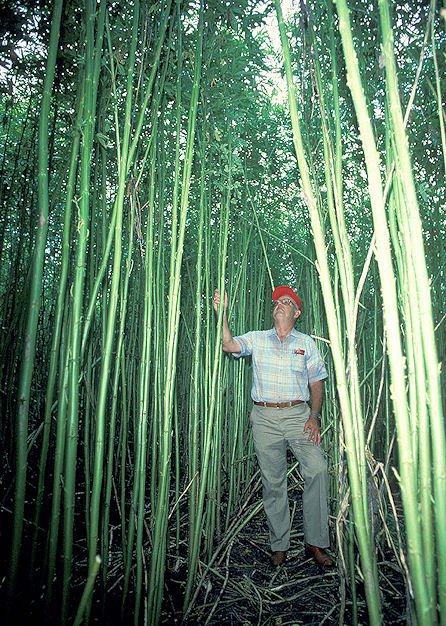

Abb.: शणः । Cannabis sativa L. 1753 - Hanf

- Hemp

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus X. Fig. 60, 1690]

Abb.: शणः । Wild wachsender Hanf, Corbett

Tiger Reserve, Uttarakhand

[Bildquelle:

Sunil Garg. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/sunilonln/2430102767/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-23. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: शणः । Hanfstängel mit Fasern und holzigem Innenbereich

[Bildquelle: Ryj / Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: शणः । Hanffasern (von Cannabis sativa L. 1753 - Hanf - Hemp)

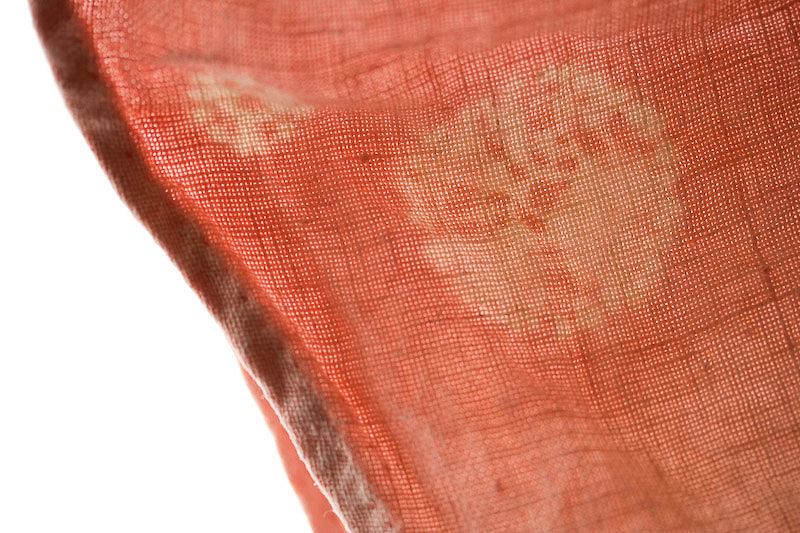

Abb.: शाणः । Hanfgewebe, Nordthailand

[Bildquelle:

Jon Anderson. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/adstream/2652382635/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: शाणः । Fundoshi -

褌,

Hanfgewebe, Japan

[Bildquelle:

yoshiyasu nishikawa. --http://www.flickr.com/photos/mitikusa/2829482393/.

-- Zugriff am 2011-02-26. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

"Cannabis sativa (Linn.) N. O. Cannabinaceae. Common hemp plant [...]

Description.—Annual, 4-6 feet, covered all over with an extremely fine rough pubescence; [...]

Fl. All the year.

Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii. 772.—Rheede, x. t 60.

Hills north of India. Cultivated in the Peninsula.

[...]

Economic Uses.—The earliest notice we have of the hemp plant is found in Herodotus (Book iv. c. 74-75), who says : " Hemp grows in Scythia; it is very like flax, only that it is a much taller and coarser plant.- Some grows wild about the country; some is produced by cultivation. The Thracians make garments of it which closely resemble linen; so much so, that if a person has never seen hemp, he is sure to think they are linen; and if he has, unless he is very experienced in such matters, he will not know of which material they are. The Scythians take some of this hemp-seed, and, creeping under felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Grecian bath can excel." —(Rawlinson's Trans., iii. 54.) The plant is here called Cannabis, the same word which we now use, and from which the English word canvas is derived. To the present day it grows in Northern Russia and Siberia, Tauria, the Caucasus, and Persia, and is found over the whole north of Europe. We next learn of it in Athenaeus, who, quoting from an ancient historian, Moschion, the description of a ship built by Hiero, King of Syracuse, and which was superintended by the famous Archimedes, says, "for ropes he provided cordage from Spain, and hemp and pitch from the river Rhone." This was Hiero II., who flourished about 270 B. C. We next hear of it in Pliny, who describes the hemp plant as being well known to the Romans, who manufactured a kind of cordage from it This author has minutely described, in the 19th book of his 'Natural History' the mode of cultivating it, and its subsequent preparation in order to obtain the fibre. He further states that in those days it had some repute in medicine, especially the root and juice of the bark, but these uses are now obsolete or of little value. It is now cultivated everywhere in India, chiefly for the intoxicating property which resides in its leaves, and which is made into the drug called Bhang. Much attention has of late years been paid to its cultivation, and several able reports upon this subject have been drawn up. According to Captain Huddleston, in the 'Transactions of the Agri. Hort Soc. of India' (viii. 260), " in the Himalaya there are two kinds; one is wild, of little or no value, but the other one is cultivated on high lands, selected for this purpose. The land is first cleared of the forest-trees : owing to the accumulation of decomposed vegetable matter, no manure is required for the first year; but after that, or in grounds which have not been cleared for the purpose, manure must be abundantly supplied to insure a good hemp crop. The plant flourishes best at elevations ranging from 4000 to 7000 feet The seeds are put down about the end of May or beginning of June ; and as soon as the young ptaits have risen up, the ground is carefully cleared of weeds and the plants thinned, with a distance between each of three or four inches. They are then left to grow, not being fit to cut before October or November."

The best hemp is procured from the male plants, and these latter are cut a month earlier than the female ones, and yield a tougher and better fibre. When the stalks are cut they are dried in the sun for several days. The seeds are then rubbed out between the hands, and this produces what is called Churrus, which is scraped off, and afterwards sold. The stalks being well dried are put up in bundles, and steeped for a fortnight in water, being kept well under by pressure, then taken out, beaten with mallets, and again dried. The fibre is now stripped off from the thickest end of the stalk, and then made up in twists for sale, and manufactured into bags and ropes.

It would appear that none of the hemp so cultivated is exported, only sufficient being grown for consumption among the inhabitants of the districts. Dr Roxburgh was the first who turned his attention to the cultivation of the plant in the plains ; and found that to insure success the ground selected should be, if possible, of a low humid description, and that the rainy season was the best in which to sow the seeds, the intense heat of the sun being prejudicial to its favourable growth. Dr Royle and others consider that with ordinary care and judicious treatment the hemp plant can be successfully cultivated in the Indian plains, though the fibres yielded may not be of such fine quality as those grown in mountainous districts. When sown for the sake of its cordage, the plant should be sown thick, in order that the stem may run up to a considerable height without branching, whereby a longer fibre is obtained, and the evaporation is less from the exclusion of air and heat, rendering the fibre of a more soft and pliable nature. The natives, on the contrary, who cultivate the Cannabis solely for the Bhang, transplant it like rice, the plants being kept about eight or ten feet apart. This has the effect of inducing them to branch, and the heat naturally stimulating the secretion, the intoxicating properties are increased. Although the cultivation of the hemp plant has considerably decreased in this country of late years, yet it would appear that plants requiring so little care might be easily reared to any extent for the sake of their fibres, should the demand require it, even were they only for use in our own dominion, without the object of exportation. It has been shown in the ' Journal of the Asiatic Society' that the cost of hemp, as prepared by the natives in Dheyra Dhoon, would be about £6 or £7 per ton in Calcutta (preparation and carriage included) ; but were the cultivation increased and improved, the extra remuneration to the cultivators, with other contingent charges, would make the total cost at the Presidency about £17 per ton. With the introduction of railways this might be still further decreased. In point of strength and durability, as evinced by the samples produced, there is no doubt that good Himalayan hemp is superior to Russian hemp. At any rate, proof exists that it can be produced of a superior quality. On a specimen of Russian hemp being shown to a native cultivator, he remarked that were he to produce such an inferior article it would never find a sale.

The hemp plant, it is said, has the singular property of destroying caterpillars and other insects which prey upon vegetables, for which reason it is often the custom in Europe to encircle the beds with borders of the plant, which effectually keeps away all insects.

It is grown in almost all parts of Europe, especially in Russia, Italy, and England. Gunja has a strong aromatic and heavy odour, abounds in resin, and is sold in the form of flowering-stalks. Bhang is in the form of dried leaves, without stalk, of a dull-green colour, not much odour, and only slightly resinous : its intoxicating properties are much less. Gunja is smoked like tobacco. Bhang is not smoked, but pounded up with water into a pulp, so as to make a drink highly conducive to health, and people accustomed to it seldom get sick. In Scinde, a stimulating infusion made from the plant is much drunk among the upper classes, who imagine that it is an improver of the appetite. Gunja is frequently mixed with tobacco to render it more intoxicating. This is especially done by the Hottentots, who chop the hemp-leaves very fine, and smoke them together in this manner. Sometimes the leaves, powdered, are mixed with aromatics and thus taken as a beverage, producing much the same effects as opium, only more agreeable.—Royle, Fib. . Plants. Müller in Hooker's Journ. of Botany."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

Jute: Rohstoffe: कालशाक - kālaśāka n.: Corchorus capsularis L. 1753 - Rundkapsel-Jute - White Jute und पट्टशाक - paṭṭaśāka m.: Corchorus olitorius L. 1753 - Langkapsel-Jute - Nalta Jute

Abb.: Jute, Naogaon -

নওগাঁ,

Bangladesh

[Bildquelle:

Arttu Manninen. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/adrenalin/167264327/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

कालशाक - kālaśāka n.: Corchorus capsularis L. 1753 - Rundkapsel-Jute - White Jute

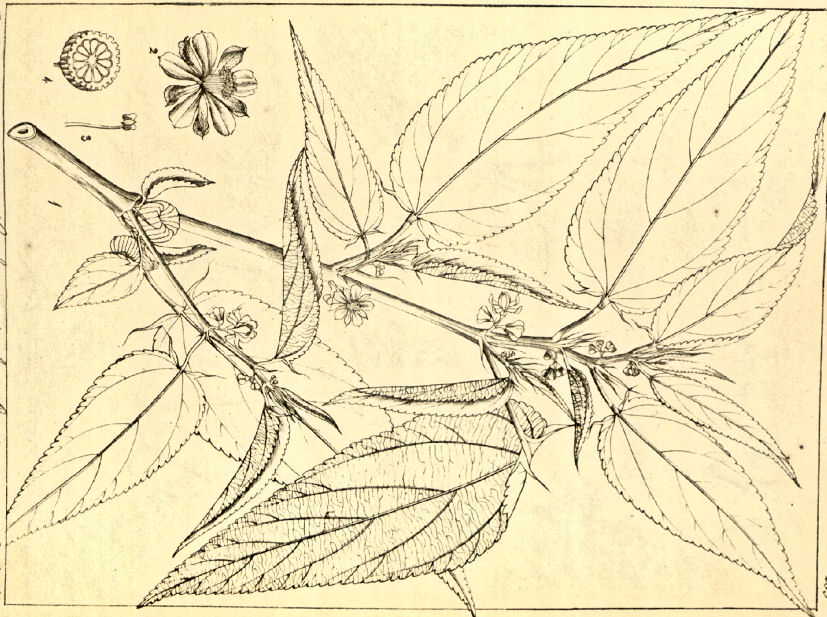

Abb.: कालशाकम् ।

Corchorus capsularis L. 1753 - Rundkapsel-Jute -

White Jute

[Bildquelle: Wight Icones I, Tab. 311, 1840]

पट्टशाक - paṭṭaśāka m.: Corchorus olitorius L. 1753 - Langkapsel-Jute - Nalta Jute

Abb.: पट्टशाकः

।

Corchorus olitorius L. 1753 - Langkapsel-Jute - Nalta Jute, Pune -

पुणे, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1459401640/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-23. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Juteverarbeitung

Abb.: Jute-Stängel, Mayapur -

মায়াপুর,

West Bengal

[Bildquelle:

Vrindavan Lila. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mayapur/4281744848/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-23. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Ablösen der Jutefasern, Naogaon -

নওগাঁ,

Bangladesh

[Bildquelle:

Arttu Manninen. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/adrenalin/167264173/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Jute-Trocknung, Mayapur -

মায়াপুর,

West Bengal

[Bildquelle:

Vrindavan Lila. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mayapur/4281744146/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-23. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Jute-Trocknung, Naogaon -

নওগাঁ,

Bangladesh

[Bildquelle:

Arttu Manninen. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/adrenalin/167264687/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

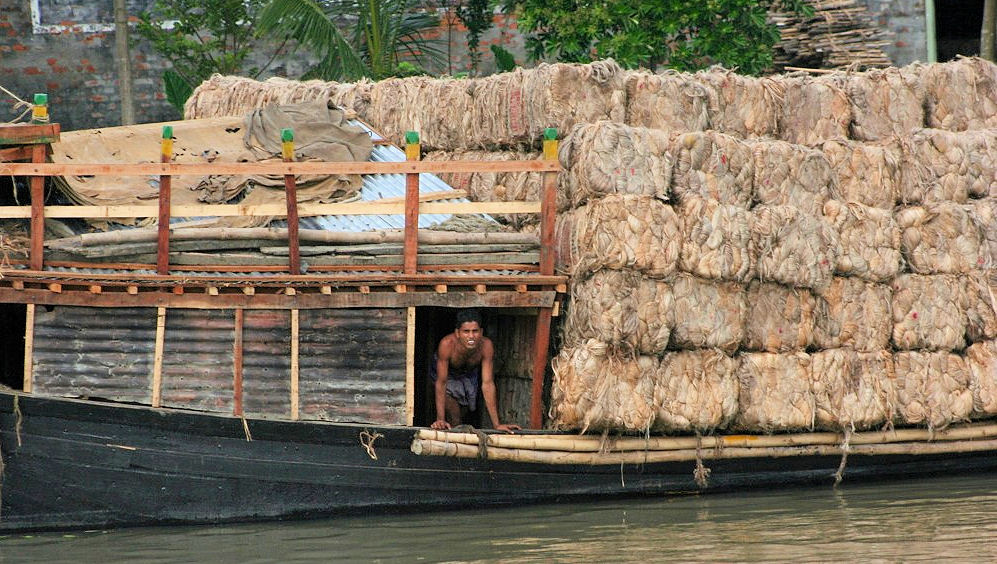

Abb.: Jute-Transport, Jamalpur - জামালপুর,

Bangladesh

[Bildquelle: Michael Foley. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/michaelfoleyphotography/392624523/. --

Zugriff am 2011-02-26. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Jute-Transport, Sundarbans -

সুন্দরবন

[Bildquelle:

Frances

Voon. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/chingfang/296232351/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Jute-Schnur

[Bildquelle: Premier Packaging /

Josh. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/retail-packaging/3501886634/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Jutegewebe

[Bildquelle: Tamorlan / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Jutesäcke

[Bildquelle: IRRI images. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ricephotos/399417291/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: Jute-Tasche von Action Bags, Saidpur - সৈয়দপুর, Bangladesh

[Bildquelle:

New Internationalist Magazine. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ni-magazine/2905884669/. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-26. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

"Corchorus capsularis (Linn.) N. O. Tiliaceae Capsular Corchorus [...]

Description.—Annual, 5-10 feet; [...]

Fl. June—July.

W. & A. Prod. i. 73. —Wight Icon. t. 311.—Roxb. Flor. Ind. ii. 581.

Peninsula. Bengal. Cultivated.

Economic Uses.—Extensively cultivated for the sake of its fibres; especially in Bengal The present species may be distinguished from all others by the capsules being globular instead of cylindrical. The cultivation and manufacture has been described in the excellent work of Dr Royle on the Fibrous Plants of India. According to his statement, the seeds are sown in April or May, when there is a probability of a small quantity of rain. In July or August the flowers have passed. When the plants are ripe, they being then from 3 to 12 feet in height, they are cut down close to the roots, when the tops are clipped off, and fifty or a hundred are tied together. Several of these bundles are placed in shallow water, with pressure above to cause them to sink. In this position they remain eight or ten days. When the bark separates, and the stalk and fibres become softened, they are taken up and untied; they are then broken off two feet from the bottom, the bark is held in both hands, and the stalks are taken off. The fibres are then exposed to the sun to be dried, and after being cleaned are considered fit for the market. These fibres are soft and silky, and may be used as a substitute for flax; but although the plant is one of rapid growth and easy culture, the fibres are very perishable, and it is owing to this circumstance that they lose much of their value. The attention of practical men has been turned to remedy so serious a defect in one of the most useful products of Bengal. Could the fibres be prepared without the lengthened immersion in water, whereby they are subsequently liable to rot and decay, the difficulty might be partially if not wholly overcome. So careful is the manufacturer obliged to be, that during the time the plants are in the water, he is forced to examine them daily in order to guard against undue decomposition; and even after they are removed from the water, the lower part of the stem nearest the root, which the hand has previously held, are so contaminated that they are cut off as useless. These fragments, however, in themselves have their use: they are shipped off to America from Calcutta for the use of paper-making, preparing bags, and suchlike purposes, and even made into whisky. The great care of watching the immersed Jute until it almost putrefies, is to preserve the fine silky character 40 ill lick valued in fibres intended for export For consumption in this country such care is not taken, therefore the article is stronger and more durable. The trade is very considerable. Besides the gunny-bags made from the fibrous part or bark, the stems of the plant themselves are used for charcoal, for gunpowder, fences, basket-work, fuel.—Royle.

Corchorus olitorius (Linn.) Do.

Jew's Mallow [...]

Description.—Annual, 5-6 feet, erect; [...] flowers small, yellow.

Fl. July—August.

W. & A. Prod, i 73.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. ii. 581.

C. decem-angularis, Roxb.

Peninsula. Bengal. Cultivated.

Economic Uses.—Rauwolf says this plant is sown in great quantities in the neighbourhood of Aleppo as a pot-herb, the Jews boiling the leaves to eat with their meat The leaves and tender shoots are also eaten by the natives. It is cultivated in Bengal for the fibres of its bark, which, like those of C. capsularis, are employed for making a coarse kind of cloth, known as gunny, as well as cordage for agricultural purposes, boats, and even paper. Roxburgh says there is a wild variety called Bun pat or Wild pat. An account of the manufacture of paper from this plant at Dinajepore, may be found in Dr Buchanan's survey of the lower provinces of the Bengal Presidency. This plant requires much longer steeping in water than hemp, a fortnight or three weeks being scarcely sufficient for its maceration. The fibre is long and fine, and might well be substituted for flax.—Roxb. Royle."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

Rohstoff: अम्बा - ambā f.: Hibiscus cannabinus L. 1759 - Dekkan-Hanf / Kenaf - Indian Hemp

Abb.: अम्बा ।

Hibiscus cannabinus L. 1759 -

Dekkan-Hanf / Kenaf - Indian Hemp

[Bildquelle: Roxburgh. -- Vol II. -- 1795. --

Tab. 190. -- Image courtesy Missouri Botanical Garden.

http://www.botanicus.org. --

Creative Commons Lizenz

(Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: अम्बा ।

Hibiscus cannabinus

L. 1759 - Dekkan-Hanf / Kenaf - Indian Hemp

[Bildquelle: David Nance / USDA. --

http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/graphics/photos/jul02/k2976-8.htm. -- Zugriff

am 2011-02-23. -- Public domain]

Abb.: अम्बा । Getrocknete Kenaf-Stängel

[Bildquelle: Scott Bauer / USDA. --

http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/graphics/photos/k7234-38.htm. -- Zugriff am

2011-02-23. -- Public domain]

Abb.: अम्बा । Kenaf-Fasern (von Hibiscus

cannabinus L. 1759 - Dekkan-Hanf / Kenaf - Indian

Hemp)

[Bildquelle: Elke Wetzig / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Hibiscus cannabinus (Linn.) N. O. Malvaceae. Deckanee Hemp [...]

Description.—Stem herbaceous, prickly; [...]

Fl. June—July.—W. & A. Prod. i. 50.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii. 208.— Cor. ii. t. 190.

Negapatam. Cultivated in Western India.

Economic Uses.—The bark of this species is full of strong fibres which the inhabitants of the Malabar coast prepare and make into cordage, and it seems as if it might be worked into strong fine thread of any size. In Coimbatore it is called Pooley-munjee, and is cultivated in the cold season, though with sufficient moisture it will thrive all the year. A rich loose soil suits it best. It requires about three months from the time it is sown before it is fit to be pulled up for watering, which operation, with the subsequent dressing, is similar to that used in the preparation of the Sunn fibre. Dr Buchanan observed that it was sown by itself in fields where nothing else grew. It goes by various names in different parts of the country. The fibres are harsh, and more remarkable for strength than fineness, but might be improved by care. It is as much cultivated for the sake of its leaves as its fibres, which former are acidulous, and are eaten by the natives. In Dr Roxburgh's experiments a line broke at 115 lb., Sunn under the same circumstances at 160 lb. But in Professor Royle's experiments this broke at 100 lb., Sunn at 150 lb. Dr Gibson states that in Bombay it is cut in November, and kept for a short time till ready for stripping the bark. The length of these fibres is usually from 5 to 10 feet.—(Royle, Roxb.) The bark of the H. furcatus yields a good strong white fibre. A line made from it broke at 89 lb. when dry, and at 92 lb. when wet. It is cut while the plant is flowering and steeped at once.—Royle."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

Rohstoff: Girardinia palmata (Forssk.) Gaudich. 1826 - Neilgherry Nettle (vermutlich = दुकूल - dukūla m.)

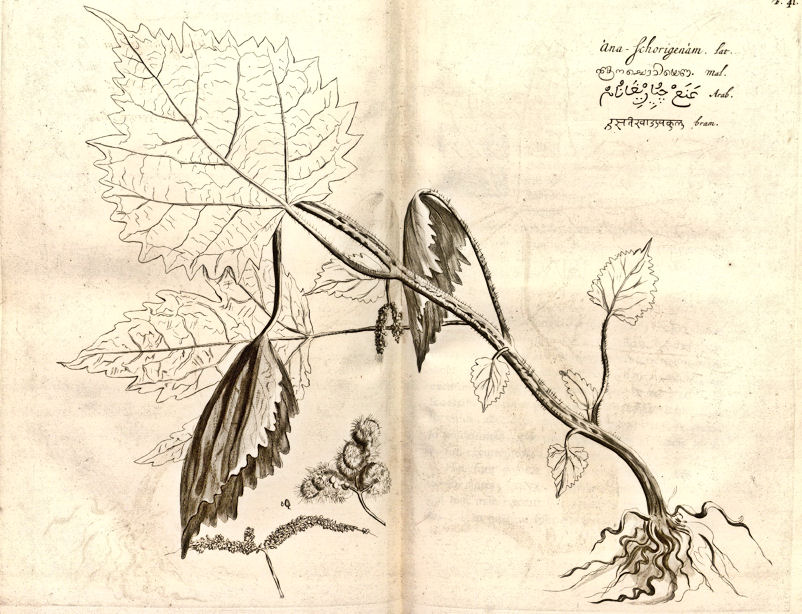

Abb.: Girardinia palmata (Forssk.) Gaudich. 1826

- Neilgherry Nettle

(vermutlich = दुकूल - dukūla m.)

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus II. Fig. 41, 1678]

"Girardinia heterophylla (Dalz.) N. O. Urticaceae. [= Girardinia palmata (Forssk.) Gaudich. 1826]

Neilgherry Nettle [...]

Description.—Annual, erect; [...] Fl. Sept.—Nov.

Dalz. Borrib. Flor., p. 238.

Urtica heterophylla, Willd.

G. Leschenaultiana, Decaisne.— Wight Icon, t 1976.—Rheede, ii. t. 41.

Common on the slopes of the Ghauts. Peninsula. NepauL

Economic Uses.—If incautiously touched, this nettle will produce temporarily a most stinging pain. The plant succeeds well by cultivation. Its bark abounds in fine, white, glossy, silk-like, strong fibres. The Todawars on the Neilgherries separate the fibres by boiling the plant, and spin it into thin coarse thread: it produces a beautifully fine and soft flax-like fibre, which they use as a thread. The Malays simply steep the stems in water for ten or twelve days, after which they are so much softened that the outer fibrous portion is easily peeled off. Dr Dickson states that the Neilgherry nettle is the most extraordinary plant; it is almost all fine fibre, and the tow is very much like the fine wool of sheep, and no doubt will be largely used by wool-spinners.—Wight. Royle.

The following report upon the cultivation and preparation of the fibre was forwarded to the Madras Government by Mr M'lvor, superintendent of the Horticultural Gardens at Ootacamund :—

Cultivation.—The Neilgherry nettle has been described as an annual plant; it has however proved, at least in cultivation, to be a perennial, continuing to throw out fresh shoots from the roots and stems with unabated vigour for a period of three or four years. The mode of cultivation, therefore, best suited to the plant, is to treat it as a perennial by sowing the seeds in rows at fifteen inches apart, and cutting down the young shoots for the fibre twice a-year—viz., in July and January. The soil best suited to the growth of this plant is found in ravines which have received for years the deposit of alluvial soils washed down from the neighbouring slopes. In cutting off the first shoots from the seedling crop, about six inches of the stem is left above the ground; this forms " stools," from which fresh shoots for the succeeding crops are produced. After each cutting the earth is dug over between the rows to the depth of about eight inches; and where manure can be applied, it is very advantageous when dug into the soil between the rows with this operation. When the shoots have once begun to grow, no farther cultivation can be applied, as it is quite impossible to go in among the plants, owing to their stinging property. The plant is indigenous or growing wild all over the Neilgherries, at elevations varying from 4000 to 8000 feet, and this indicates the temperature best suited to the perfect development of the fibre.

Produce per acre.—From the crop of July an average produce of from 450 to 500 lb. of clean fibre per acre may be expected. Of this quantity about 120 lb. will be a very superior quality; this is obtained from the young and tender shoots, which should be placed by. themselves during the operation of cutting. The crop of January will yield on an average 600 or 700 lb. per acre; but the fibre of this crop is all of a uniform and somewhat coarse quality, owing to shoots being matured by the setting in of the dry season in December. It might therefore be advantageous, where fine quality of fibre only was required, to cut the shoots more frequently—probably three or four times in the year—as only the finest quality of fibre is produced from young and tender shoots.

Preparation of the fibre.—Our experiments being limited, our treatment of the fibre has been necessarily very rude and imperfect, as in this respect only in extensive cultivation can efficient appliances be obtained.

The inner bark of the whole of the plant abounds in fibre, that of the young shoots being the finest and strongest, while that of the old stems is comparatively short and coarse, but still producing a fibre of very great strength and of a peculiar silky and woolly like appearance, and one which no doubt will prove very useful in manufactories.

For cutting down the crop fine weather is selected; and the shoots when cut are allowed to remain as they fall for two or three days, by which time they are sufficiently dry to have lost their stinging properties; they are, however, pliable enough to allow of the bark being easily peeled off the stems, and separated from the leaves. The bark thus taken from the stems is tied up in small bundles and dried in the sun, if the weather is fine; if wet, is dried in an open shed with a free circulation of air. When quite dry, the bark is slightly beaten with a wooden mallet, which causes the outer bark of that in which there is no fibre to break and fall off. The fibrous part of the bark is then wrapped up in small bundles, and boiled for about an hour in water to which a small quantity of wood-ashes has been added, in order to facilitate the separation of the woody matter from the fibre. The fibre is then removed out of the boiling water, and washed as rapidly as possible in a clear running stream, after which it is submitted to the usual bleaching process employed in the manufacture of fibre from flax or hemp.—Report, April 1862."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

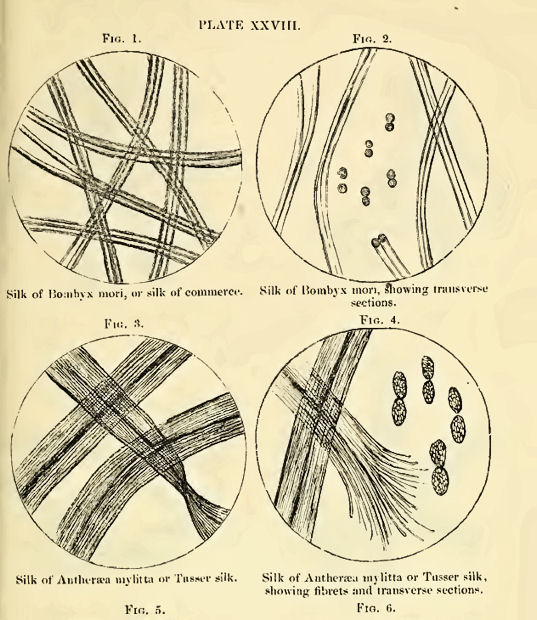

| 12c./d. vālkaṃ kṣaumādi phālaṃ tu kārpāsaṃ bādaraṃ ca tat वाल्कं क्षौमादि फालं तु कार्पासं बादरं च तत् ॥१२ ख॥ फाल - phāla 3: von Früchten stammend, ist

|