|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 15. vaiśyavargaḥ (Über Vaiśyas). -- 3. Vers 15c - 27a (Ackerbau II, Nutzpflanzen). -- Fassung vom 2011-07-06. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa7/amara215c.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-07-06

Überarbeitungen:

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

Bei der Identifikation der lateinischen Pflanzennamen folge ich, wenn immer es möglich ist:

Bhāvamiśra <16. Jhdt.>: Bhāvaprakāśa of Bhāvamiśra : (text, English translation, notes, appendences and index) / translated by K. R. (Kalale Rangaswamaiah) Srikantha Murthy. -- Chowkhamba Varanasi : Krishnadas Academy, 1998 - 2000. -- (Krishnadas ayurveda series ; 45). -- 2 Bde. -- Enthält in Bd. 1 das SEHR nützliche Lexikon (nigaṇṭhu) Bhāvamiśras.

Pandey, Gyanendra: Dravyaguṇa vijñāna : materia medica-vegetable drugs : English-Sanskrit. -- 3. ed. -- Varanasi : Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy, 2005. -- 3 Bde. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN: 81-218-0088-9 (set)

Wo möglich, erfolgt die aktuelle Benennung von Pflanzen nach:

Zander, Robert <1892 - 1969> [Begründer]: Der große Zander : Enzyklopädie der Pflanzennamen / Walter Erhardt ... -- Stuttgart : Ulmer, ©2008. -- 2 Bde ; 2103 S. -- ISBN 978-3-8001-5406-7.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Pflanzen wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut

ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Pflanzen wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut

ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

Poaceae - Süßgräser

| 15c./d. āśu vrīhiḥ pāṭalaḥ syāt sitaśūka-yavau samau आशु व्रीहिः पाटलः स्यात् सितशूक-यवौ समौ ।१५ ख। [Bezeichnungen für (Varietäten des) Regenzeiten-Reis:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Rice ripening in the rains."

Siehe auch:

Payer, Margarete <1942 - >: HBI weltweit. -- 4. Philippinen. -- 4.1. Das International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). -- URL: http://www.payer.de/reislink.htm

Der Bhāvaprakāśa nennt als Beispiele folgende Sorten von vrīhi:

वीहि - vrīhi m.: Reis, der in der Regenzeit geerntet wird

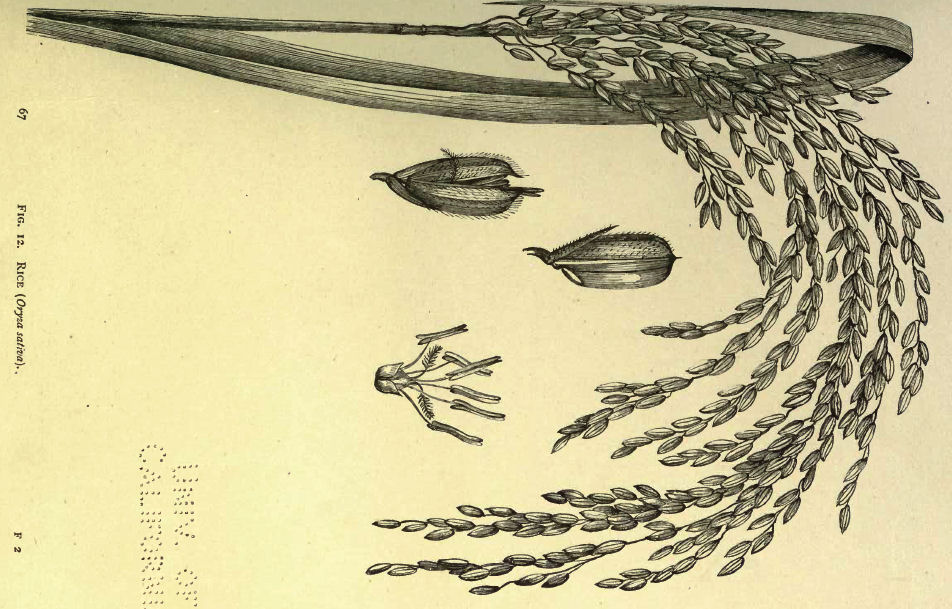

Abb.: व्रीहिः । Oryza sativa L. 1753 - Reis - Rice, Ähre von

Basmati-Reis 370

[Bildquelle: IRRI. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ricephotos/2198723243/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-28. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: व्रीहिः । Oryza sativa L. 1753 - Reis - Rice

[Bildquelle: Church, A. H. (Arthur Herbert) <1834-1915>: Food-grains of

India. -- London, 1886.]

Abb.: व्रीहिः । Oryza sativa L. 1753 - Reis - Rice

[Bildquelle: Church, A. H. (Arthur Herbert) <1834-1915>: Food-grains of

India. -- London, 1886.]

Abb.: व्रीहिः । Körner von Oryza sativa L. 1753 - Reis - Rice

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

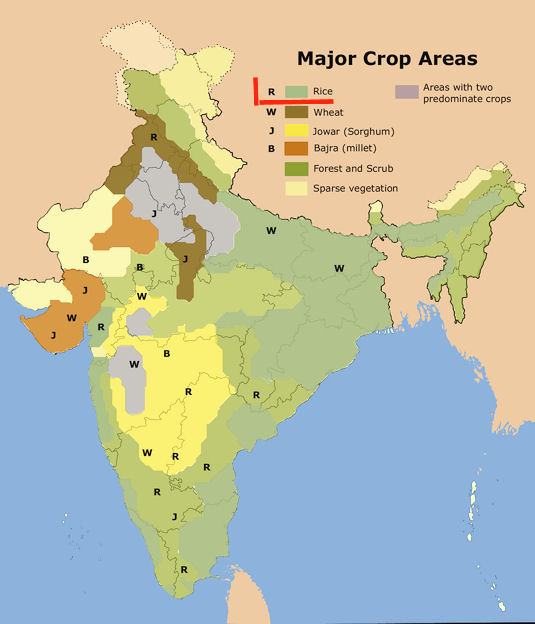

Abb.: व्रीहिः । Reisanbaugebiete Indiens

[Bildquelle: Amog / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: व्रीहिः । Vielfalt der Reissorten: Blick in einen Raum der

International Rice Genebank, wo ca. 110.000 (!) Reissorten keimfähig

erhalten werden, IRRI (International Rice Research Institute), Los Baños,

Philippinen

[Bildquelle: IRRI. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ricephotos/367810367/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-28. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle

Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: व्रीहिः । Vielfalt der Reissorten: Kolaba (कुलाबा)

Markt in Mumbai - मुंबई, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: ૐ Dey Alexander ૐ. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dey/3136417/. -- Zugriff am 2011-06-28. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

पाटल - pāṭala m.: Reis mit der Farbe von पाटला - pāṭalā f.:

Stereospermum chelonoides (L. f.) DC. 18381, d. h. gelber Reis

Abb.: पाटलः । Ausschnitt aus den farblichen Varietäten verschiedener

Reissorten / Artwork conceptualized by K. McNally

[Bildquelle: Chrisanto Quintana of IRRI. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ricephotos/3742368354/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-28. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

1

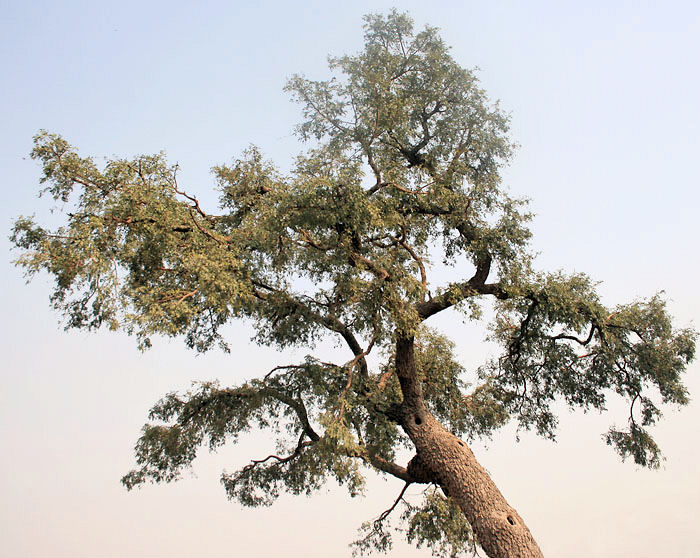

पाटला - pāṭalā f.: Stereospermum chelonoides (L. f.) DC. 1838Bignoniaceae - Trompetenbaumgewächse

Abb.: पाटला - pāṭalā f.:

"RICE.

Oryza sativa, L.

Hind. - Beng. - Dhan (cleaned rice is Chauwal, Chawal, Chaol, in Hind.). Tamil

- Arisi. Telugu Ūri, Cheni, Matta-Karulu. Sind - Sari. Sinhalese - Goyang.

Sanskrit - Vrihi, Arunya, Dhanya.

Rice is an annual grass belonging to the tribe Oryzeae of the natural order Gramineae. It grows from 2 to 10 or more feet in height ; the panicles vary from 8 inches to a foot or even more in length, and become drooping; the fruit or grain is enclosed in but does not adhere to the pales.

The several rice-crops of India may be termed spring, summer, autumn, and winter-rice, from the seasons in which the different varieties are harvested. Winter-rice is the most important, constituting as it does about three-fourths of the entire amount. Only in Purī, Maldah, Rājshāhi, and Sylhet does spring-rice attain even so high a percentage of the entire crop as 12 to 25 ; in other localities it is not grown at all or its amount is quite insignificant. The autumn or intermediate crop of rice is likewise of little or no importance, save in about a dozen localities out of 63 concerning which we possess statistics. However, in Patnā, Hazāribāgh, Purī, and Cuttack, it may reach one-third -of the total out-turn, while it amounts to about one-fourth or one-fifth in Santāl Parganās, Bānkurā, and Midnapur. Summer-rice is a very general crop throughout India. In one locality, Nuddea, it yields two-thirds of the total amount grown ; in Champāran, Bīrbhūm, Dacca, and Faridpur, about one-third ; and in many other localities, about one-fourth.

The several rice-crops bear different names in different parts of India ; in the present section we have generally employed the terms used in Bengal, Boro for spring-rice, Aus for summer-rice, Kartika for autumn or intermediate rice, and Āman for winter-rice.

Spring-rice is sown, according to locality, from September to February, and reaped from March to June. Summer-rice is sown from May to July, and reaped from September to October. Autumn-rice is sown in Bengal from April to July, and reaped from August to November ; in Jessur it is sown in October and November, and reaped eleven months after. Winter-rice is sown from March to August, and reaped from November to January. Where one crop only of rice is grown in the year it is usually sown from May to August, and reaped from September to January. Where two crops are raised the yield of grain from both crops is little larger than that from one, but the straw of the crop gathered in the dry season, though a wretched fodder, is used for cattle-food. The two chief varieties of rice, winter and summer, are occasionally sown mixed together ; sometimes with Panicum miliaceum and Phaseolus Mungo. Peas, oil-seeds, barley, etc., are also largely sown over the nearly ripe crop, which, however, is cut before they appear above ground.

With regard to the several rice-crops, Mr. G. Watt says : "A proprietor of an estate, with a fairly mixed soil, might have three, if not four, or even five, harvests of rice every twelve months, thus :

- Aus harvest, from July to August.

- Chotan āman, from October to November.

- Boran āman, from December to January.

- Boro, from April to May.

- Raida, from September to October.

"Two harvests are all but universal in Bengal, with an occasional third but smaller one ; two crops are frequently taken off the same field."

"The long, thin chotan āman rices are eaten by the richer natives."

Rice grows well in stiff clays, especially in drainage-beds and basins. Manure is not often used. It is sown in a moist soil, or even in an actual mud, either broadcast or transplanted from a nursery when the plants are something less than a foot high ; the distance between the plants is about 6 inches. The yield of transplanted rice is 16 maunds of paddy per acre ; when sown broadcast it yields from 10 to 12 maunds. Mr. Duthie states that there are at least 100 cultivated varieties of rice in the North-West Provinces and Oudh ; a distinct -indigenous species of another genus, Hygrorhiza aristata (Nees), growing wild round lakes and marshes, is gathered and eaten by the poorer classes. The more important varieties of rice are semi-aquatic, and need copious and repeated irrigations. In some districts of Bengal a long-stemmed variety of rice is grown which will keep its head above 12 feet of water. On the other hand, there are varieties of rice which develop in temperate climates, even ascending the hills to an altitude of at least 8,000 feet, and requiring no irrigation.

The analyses which have been made of a large number of samples of "cleaned" rice, give figures which are wonderfully accordant, considering the great differences in the appearance of the specimens and the very diverse conditions under which they have been grown. The fibre and adventitious earth are sometimes rather high from imperfect cleaning of the grain, but the nitrogenous constituents or albuminoids oscillate within narrow limits probably nine samples out of ten will be found to contain not less than 7 per cent., and not more than 8. [...]

There are many districts in India where rice forms not merely the chief food-stuff but ¾ths or even 4/5ths of its total amount. In some places it even rises to 7/8ths or to 15/16ths of the whole quantity, as in Bardwān, Dinajpur, Maldah, Kuch Behar, Mānbhūm, and Darrang ; other districts might be named in which it constitutes the only food staple.

Dhan is rice in the husk, or paddy. Chaol is rice husked by pounding in a wooden mortar; in some districts it is, if new, parboiled and then dried before being pounded. Eight pounds of dhan produce 5 pounds of chaol; the separated pericarp is burned, the perisperm is given to fowls and pigs. The operation of pounding is attended with considerable loss, because many grains are broken and then afterwards winnowed away when tossing the rice in the air from the woven straw scoop. Bhat is boiled rice. In Tirhūt and Sāran the chaol is first washed and then boiled at night, for the evening meal, in much water. It is strained when hot, one-half or one-third being set aside under water (to save the cost of more fuel) for the morning meal— it has then become slightly acidulous. This preparation is eaten with curds, chillies, or one-fourth of dhal (pulse husked and split). Two pounds of cleaned rice weigh 5 pounds after boiling. The liquor is either thrown away or is drunk as a beverage after the addition of a little common salt, or is given to stall-fed milch cows.

Where rice constitutes the almost entire food of the population, the throwing away of the water in which it has been boiled involves the loss of some of the mineral matter in which rice is notoriously deficient, and is to be deprecated ; no more water should be used in cooking this grain than can be absorbed by it. Rice is sometimes boiled in milk. The parching of rice is often done by stirring it in hot sand and then sifting out the grains. They burst, and are eaten dry, or else are ground, mixed with water, and consumed at midday meals by travellers and labourers. In Maldah the Hindustani-speaking population use rice and wheat, the pure Bengali confines himself to rice. In Benares rice is not much used, being replaced, amongst the poor, by wheat, barley, jowari, bājra, and maize. The industrial and labouring classes of Mirzāpur consume but little rice, living chiefly on barley and the various millets.According to the "Report of the Famine Commission" the percentages of the rice-eating population in 7 provinces, etc.,were :

Madras 32 Central Provinces 31 Mysore 20 Bombay 12 North-West Provinces and Oudh 19 Punjab 5 Berar 2 The exports of rice and paddy from India amounted in 1882-83 to 31¼ million cwts. Sixty-eight percent. of this came from Burma, 26 per cent. from Bengal, and 4 per cent. from Madras. Of the total exports, 61 per cent. were sent to England or the Continent (including Egypt).

Rice is eaten in many forms and prepared in many ways besides those already described. The five following preparations may be selected for notice :

Churwa, Chura, or Chira. Some dhan is boiled, dried, and pounded to separate the husks ; the chaol thus obtained is then heated in a wide-mouthed earthen pot, and while still hot is flattened by beating. This preparation may be eaten alone, but it is often made into balls with gūr or molasses, or taken with curdled milk (doyi) with milk and tamarinds, or with sweetmeats.

Alochira is made by steeping the rough dhan for a night in cold water ; it is then parched and afterwards flattened by beating.

Khoyi is made by parching rice which has been exposed to the dew. It is eaten with molasses, constituting murki, or with milk.

Muri or Murhi is prepared by first heating chaol with salt for about half-an-hour in a shallow earthen vessel kept agitated, and finally parching it. It is eaten by the poor, generally by itself but sometimes with oil.

Chaol-ka-atta is rice-meal made by slow grinding in heavy hand-mills. It is kneaded with water into balls or cakes (bhaka), which are boiled like a pudding, or used as bread."

[Quelle: Church, A. H. (Arthur Herbert) <1834-1915>: Food-grains of India. -- London, 1886. -- S. 66 - 75]

"ORYZA SATIVA, Linn. Fig.—Bentl. and Trim., t. 291; Rheede, Hort. Mal. v., 196—201.

Rice (Eng.)

Hab.—Throughout India, wild and cultivated. The grain, spirit, and vinegar.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—Wild rice was probably used by the aboriginal tribes of India in prehistoric times; it is still carefully collected by the peasantry, who consider it to have special virtues, and call it "god's rice," "hermit's rice," &c. Rice (व्रीहि is not mentioned in the Rig-Veda, but in the Atharva-Veda it is noticed along with barley, māsha (Phaseolus Roxburghii), and sesamum. Rice cultivation in India appears to have been subsequent to that of China and Burma. Girard de Rialle, in his Mythologie comparée, states that the Karens of Burma believe that every plant has its lā or kelah (spirit). The rice has its spirit, and when the crop is bad, they pray to it in the following terms: "Come, O spirit of the rice, come back ! come to the rice-field, come to the rice ! come from the East, come from the West, come from the beak of the bird, from the mouth of the monkey, from the throat of the elephant, come from the grain stores! O kelah of the rice, return to the rice!" In Siam they offer rice and cakes to trees before cutting them down. In Bengal sacrifices of rice are made to the Bael tree, probably a survival of an ancient fetish worship which the Brahmins have sanctioned by deifying the tree.

Rice plays an important part in the marriage ceremonies of the Hindus. According to the Grihya-sutra of Asvalāyana, the bride must walk three times round the altar, and at the completion of each turn make an offering of rice. This ceremony resembles an ancient form of marrying among the Romans, in which an offering of a cake made of fār (spelt) was made in the presence of the Pontifex Maximus or Flamen Dialis and ten witnesses.

Parched rice, Lājā also called Syāla (Sya "a winnowing fan," and lā for lājā), is scattered by the bride's brother at marriages. Rice is poured over the head of the bride and bridegroom as an emblem of life, regeneration and plenty. On the fourth day of the marriage ceremonies the young couple eat rice together for the first and only time in their lives, and on the last day they both celebrate together the Soma sacrifice, when they throw lājā into the fire. At the birth of a child the father places the red Akshata rice on its forehead to avert evil, and when the child is named it is placed on a cloth covered with rice. Rice is also used in some parts of India to detect witches: a small bag of rice, bearing the name of each of the suspected parties, is placed in a white-ants' nest, and the one they first eat is considered to belong to the guilty party. When several persons are suspected of a crime, rice is sometimes used to detect the guilty one— For this purpose the persons are required to chew rice, the criminal being discovered by his inability to properly masticate it, owing probably to fear checking the free flow of saliva. Vincenzo Maria da Santa Caterina mentions in his travels that rice and turmeric are offered in India to the gods to obtain children and the cure of female diseases, and that young girls make a vow to offer rice, should they obtain a good husband. In the consecration of the Brahmachari, the father of the youth carries in his hands a cupful of rice, and the assistants after the bath cover the candidate with rice. Asvalāyana says that the disciple asks alms to learn the Vedas; he obtains the rice as alms and must cook it before sunset. His commentator, Narayana, adds that when the rice has been cooked, the disciple should say to his master, "the food of the pot is ready." In sacrifices to Rudra, according to Asvalāyana, the husk of rice was thrown into the fire along with the smallest grains, and the tail, skin, head, and feet of the animal, and that the latter before being killed was sprinkled with rice and barley-water.

In times of fasting and penitence, grains of rice and barley are watered and blessed and offered to the gods. In funeral ceremonies rice and other food is offered to crows. According to Manu, the twice-born are directed to offer five great sacrifices, viz., with wild rice (Nivāra), with various pure substances, or with herbs, roots, and fruits.

The practice of worshipping the new rice at the time of the harvest is common throughout India. In Bengal, on a Thursday, in the month of Pansha (December-January), after the crop has been reaped, a rattan-made grain measure called rek, filled with the grain upon which are placed gold, silver and copper coins and some cowrie shells, is worshipped as the representative of the goddess of fortune. This worship is repeated in the months of Chaitra, Sravana, and Kārtika. In Western India the new rice is worshipped at the Dasara and Devali festivals, and in Madras the same event is celebrated by the Pongol ceremony, when the new rice is boiled for the first time and eaten with great rejoicings. Among the Native Catholics the same ceremony is perpetuated in the "blessing of the new rice," which is done by the priest in the field before the crop is cut.

That the cultivation of rice had widely spread in the time of Alexander (400 B.C.) we learn from Strabo, who says,"according to Aristobulus, rice grows in Bactriana, Babylonia, Susida," and he adds, "we may also say in Lower Syria." Further on he notes that the Indians use it for food, and extract a spirit from it. The Greek names for rice are derived from the Sanskrit Vrihi; the earliest form occurs in a fragment of Sophocles, where rice-bread is called

ορινδης αρτος; in later writers we meet with the form ορυζα. The Arabic names have the same derivation, the oldest form being Runz, occurring in the local dialect of the Abd-el-Kais, near Bahrain, and the more modern forms Aruzz and Ruzz. In Persian the form of Birinj is current, as well as the Sanskrit name Shāli, for unhusked rice. Dioscorides briefly mentions rice as being of little nutritive value and apt to cause costiveness. Celsus (ii., 20) classes it along with wheat and spelt as "res boni succi." According to Sanskrit writers, the best class of grains includes wheat, rice, and barley only, other kinds being relegated to the class Kshudra dhānya or inferior grains. The preparations of rice used in the diet of sick people, and described in Sanskrit medical works, are:—यवागु (yavāgu) or powdered rice boiled with water. It is made of three strengths, namely, with nine, eleven, and nineteen parts of water, called, respectively, Vilepi, Peyā, and Manda. Instead of water, a light decoction of some aromatic and carminative drug, such as ginger or pepper, may be used in preparing yavāgu.

लाजा (lājā) or unhusked rice parched in hot sand. It is used as light and digestible diet for the sick.

भृष्टतण्डुल (brishta tandula) or husked rice parched in hot sand. It is used for the same purposes as lājā.

पृथूका (prithukā) or unhusked rice moistened, parched, and afterwards flattened and the husk removed. It is soaked in water or boiled and given with curdled milk as an astringent diet in diarrhoea or dysentery.

पायस (pāyasa) or rice-inilk. A well-known preparation.

तण्डुलाम्बु (tandulāmbu) or water in which unboiled rice has been steeped. This is often used as a vehicle for powders, &c., and as a diet drink.

Rice is the staple-food of the inhabitants in Bengal, many parts of Madras, Burma, and the Western Coast of India, but not of the central and northern parts of the country, where wheat and millet are the staples and rice only a luxury.

Fermented and distilled rice liquors are largely used in many parts of India. For an account of the economic uses of the grain, its cultivation, and the numerous varieties of the plant met with in different parts of the country, we must refer the reader to a diffuse but interesting article by Dr. G. Watt in the Dictionary of the Econ. Prod, of India."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 601 - 605.]

Poaceae - Süßgräser

| 15c./d. āśu vrīhiḥ pāṭalaḥ syāt sitaśūka-yavau samau आशु व्रीहिः पाटलः स्यात् सितशूक-यवौ समौ ।१५ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Gerste - Hordeum vulgare L. 1753:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Barley."

सितशूक - sitaśūka m.: "weißgrannig", Gerste (Hordeum vulgare L. 1753)

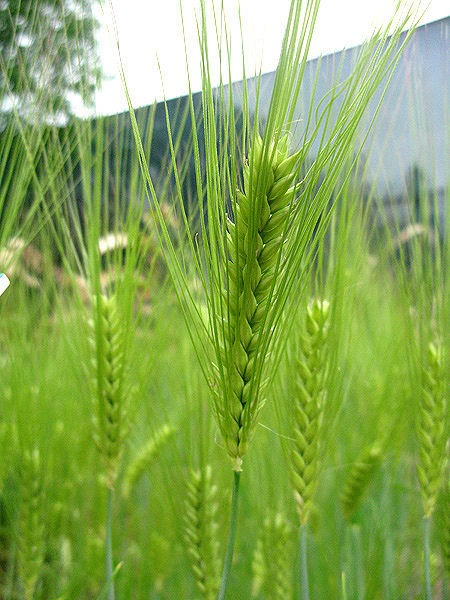

Abb.: सितशूकः । Gerste - Hordeum

vulgare L. 1753 (man beachte die weißen Grannen = "Borsten")

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

यव - yava m.: Gerste (Hordeum vulgare L. 1753)

Abb.: यवः । Gerste - Hordeum

vulgare L. 1753

[Bildquelle: Thomé, 1885]

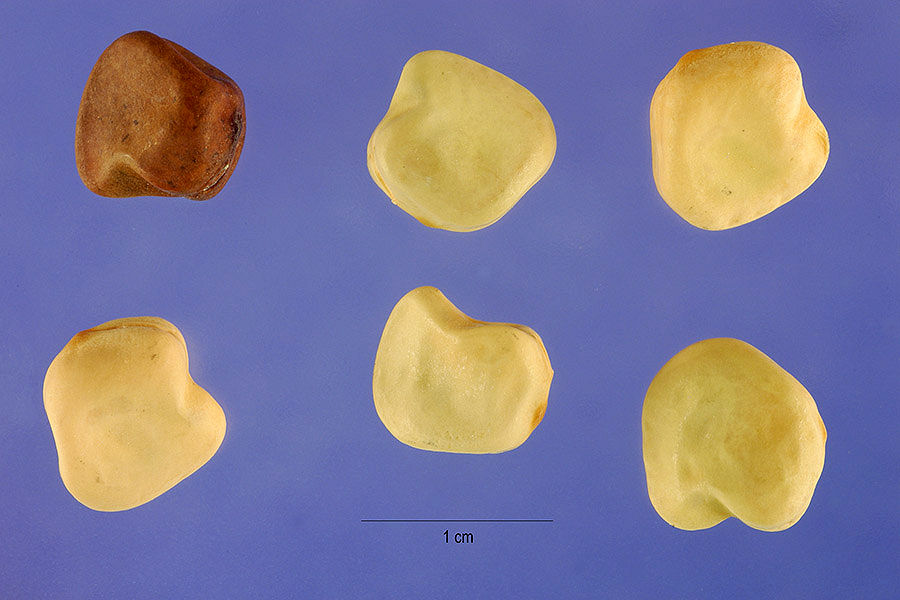

Abb.: यवः । Gerstenkörner - Hordeum

vulgare L. 1753

[Bildquelle: Rasbak / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: यवः । Gerstenkörner - Hordeum

vulgare L. 1753

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public

domain]

"HORDEUM HEXASTICHUM, Linn. Fig.—Duthie, Fodder Grasses of N. India, PL F, f. 32.

Barley

Hab.—Western temperate Asia. Cultivated in the N.-W. Provinces of India,

[...]

History Uses, &C.—Indra in the Rig-Veda is called durah yavasya, "the giver of the barley." At many Hindu ceremonies, such as the birth of a child, marriages, funerals, and in various sacrifices, barley is used. In the Atharva-Veda the rice and barley offered to the dead are prayed to to be propitious to them, and in the same Veda rice and barley are invoked for the cure of disease and deliverance from other evils: "Etau yakshmain vi bādhete; etan muñchato anhasas." Barley is symbolic of wealth and plenty; it is also a phallic emblem; Asvalāyana, in the first book of the Grihyasutra, says that in Vedic times, the wife when three months gone with child fasted; after her fast, her husband came to her with a pot of sour milk into which he threw two beans and a grain of barley, and whilst she was drinking it, he asked, "What drinkest thou ?" She, having drunk three times, replied, "I drink to the birth of a son." Nārāyana, in his Commentary on Asvalāyana, states that the two beans and the grain of barley represent the organs of generation. (De Gubernatis.)

At the Yava-chaturthi, on the fourth day of the light half of the month Vaisākh, a sort of game is played in which people throw barley-meal over each other. Yava-sura, an intoxicating drink, is made from barley in Northern India. According to Bretschneider, barley is included among the five cereals, which, it is related in Chinese history, were sowed by the Emperor Shen-nung, who reigned about 2700 B.C. ; but it is not one of the five sorts of grain which are used at the ceremony of ploughing and sowing as now annually performed by the emperors of China.

Theophrastus was acquainted with several sorts of barley (

κριθη), and, among them, with the six-rowed kind or hexastichon, which is the species that is represented on the coins struck at Metapontum in Lucania between the 6th and 2nd centuries B.C.Barley is mentioned in the Bible as a plant of cultivation in Egypt and Syria, and must have been, among the ancient Hebrews, an important article of food, judging from the quantity allowed by Solomon to the servant of Hiram, king of Tyre (B.C. 1015). The tribute of barley paid to King Jotham by the Ammonites (B.C. 741) is also exactly recorded. The ancients were frequently in the practice of removing the hard integuments of barley by roasting it, and using the torrified grain as food. (Pharmacographia.)

The Hindus employ barley in the dietary of the sick. It is chiefly used in the form of saktu or powder of the parched grain. Gruel prepared from saktu is said to be easily digested and to be useful in painful dyspepsia. In Europe, for use in medicine and as food for the sick, pearl-barley is always employed; this is the grain deprived of its husk by passing it between horizontal mill-stones, placed so far apart as to rub off the integuments without crushing it. Pearl-barley imported from Europe is obtainable in most Indian bazars. For an account of the economic uses of barley, we would refer the reader to an article by Dr. J. Murray in the Dict. Econ. Prod. of India (iv., p. 273).

[...]

Commerce.—The total yield of barley in British India does not exceed 50,000,000 cwts. In 1887-88 the total exports were 29,575 cwts., valued at Rs. 89,776, of which Bombay shipped 18,688 cwts., Bengal 6,873 cwts., and Sind 4,014 cwts., valued at Rs. 58,632, Rs. 20,556, and Rs. 10,588, respectively. The country which imported most largely was Persia, with 10,358 cwts.; following on which were, Arabia with 7,675 cwts , Ceylon with 7,539 cwts., and Aden, the United Kingdom, Zanzibar, and "other countries'' with insignificant quantities. (Diet. Econ. Prod. India, iv., p. 281.)"

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 615 - 618.]

| 16a./b. tokmas tu tatra harite kalāyas tu satīnakaḥ तोक्मस् तु तत्र हरिते कलायस् ति सतीनकः ।१६ ख। Grüne Gerste heißt तोक्म - tokma m.: "ein junger, grüner Halm von Getreidepflanzen, namentlich Gerste" (PW) |

Colebrooke (1807): "Green or unripe barley."

तोक्म - tokma m.: "ein junger, grüner Halm von Getreidepflanzen, namentlich Gerste" (PW)

Abb.: तोक्मः । Gerste - Hordeum

vulgare L. 1753

[Bildquelle: Muséum de Toulouse. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/museumdetoulouse/4656255862/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-28. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

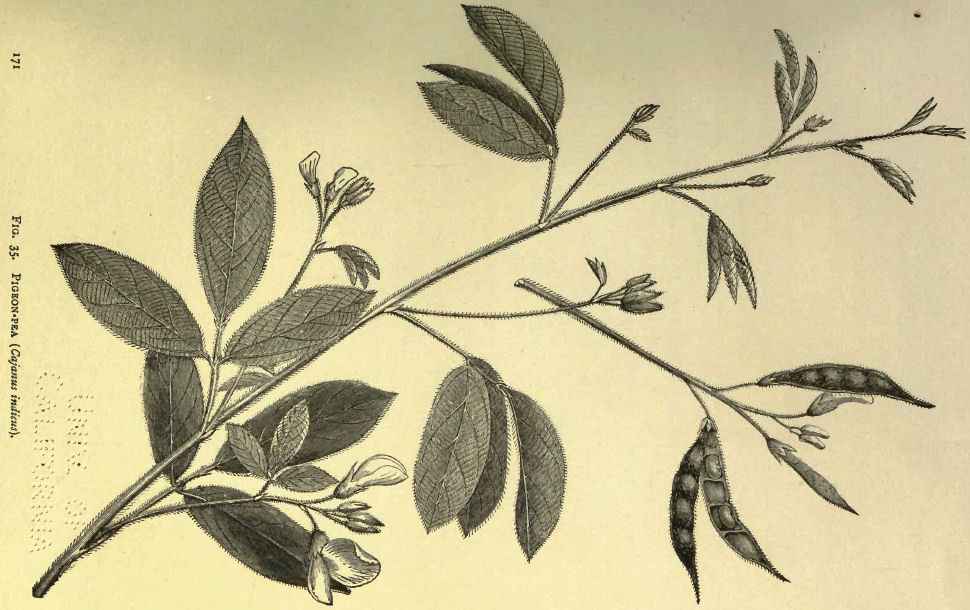

Fabaceae - Hülsenfrüchtler

| 16a./b. tokmas tu tatra harite kalāyas tu satīnakaḥ 16c./d. hareṇu-khaṇḍikau cāsmin koradūṣas tu kodravaḥ

तोक्मस् तु तत्र हरिते कलायस् ति सतीनकः ।१६

ख। [Bezeichnungen für Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 - Saat-Platterbse - Chickling Pea:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Peas. Some writers distinguish the three first terms as names of three kinds of pulse."

Hindi: लतरी

कलाय - kalāya m.: Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 - Saat-Platterbse - Chickling Pea

Abb.: कलायः । Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 - Saat-Platterbse -

Chickling Pea

[Bildquelle: Botanical Magazine. -- Vol. 3-4 (1790/91). -- Pl. 114.]

सतीनक - satīnaka m.: Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 - Saat-Platterbse - Chickling Pea

Abb.: सतीनकः । Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 - Saat-Platterbse -

Chickling Pea

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

हरेणु - hareṇu m.: Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 - Saat-Platterbse - Chickling Pea

Abb.:

हरेणुः । Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 -

Saat-Platterbse - Chickling Pea

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

खन्डिक - khaṇḍika m.: Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 - Saat-Platterbse - Chickling Pea

Abb.: खन्डिकाः । Lathyrus sativus L.

1840 - Saat-Platterbse - Chickling Pea

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

"THE VETCHLING. Lathyrus sativus, L.

[...]

A much-branched annual herb, having equally pinnate leaves ; leaflets 2, linear or lanceolate. The pods are 1½ inch long, 4 to 5-seeded. It is spread through the Northern Provinces, ascending from the plains of Bengal to 4,000 feet in Kumaun.

The genus Lathyrus belongs to the tribe Vicieae of the suborder Papilionaceae. There is another species, not an Indian plant (L. tingitanus), which like L. sativus is extensively cultivated.

This is a cold-weather or rabi crop, and is grown on land unfitted for most other pulse. It is sown in October and November and reaped in March and April.

[...]

There is reason to suspect the occasional presence, in injurious proportion, of a poisonous bitter principle in this vetchling. It has a bad reputation, and is almost universally regarded in Bengal as unwholesome, deranging digestion, and producing dysentery, diarrhoea, and various skin diseases. But some allowance must be made for the prejudice of the Bengalese. It is most used by the poorer classes, being

the cheapest and most abundant pulse. Many cases of sudden and incurable paralysis have been undoubtedly traced to the large and continuous use of this seed. It formed, by a series of accidents, the chief food, during the years 1829-33, of some of the eastern villages of Oudh. Many cases of sudden paralysis of the lower extremities occurred during that period, the persons attacked being generally under thirty years of age.This is a coarse kind of pulse, hard and difficult to cook. It is used in Behar and Patna in curries. It is also made into paste-balls which are fried in ghi and eaten with boiled rice ; it is also eaten as dal."

[Quelle: Church, A. H. (Arthur Herbert) <1834-1915>: Food-grains of India. -- London, 1886. -- S. 132 - 135.]

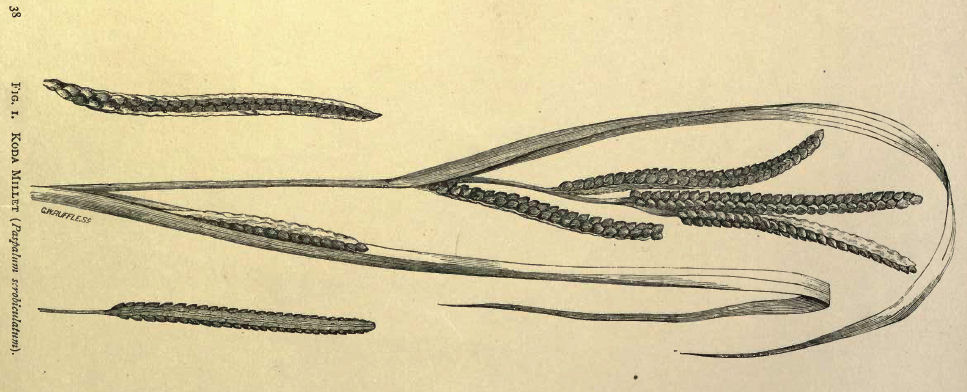

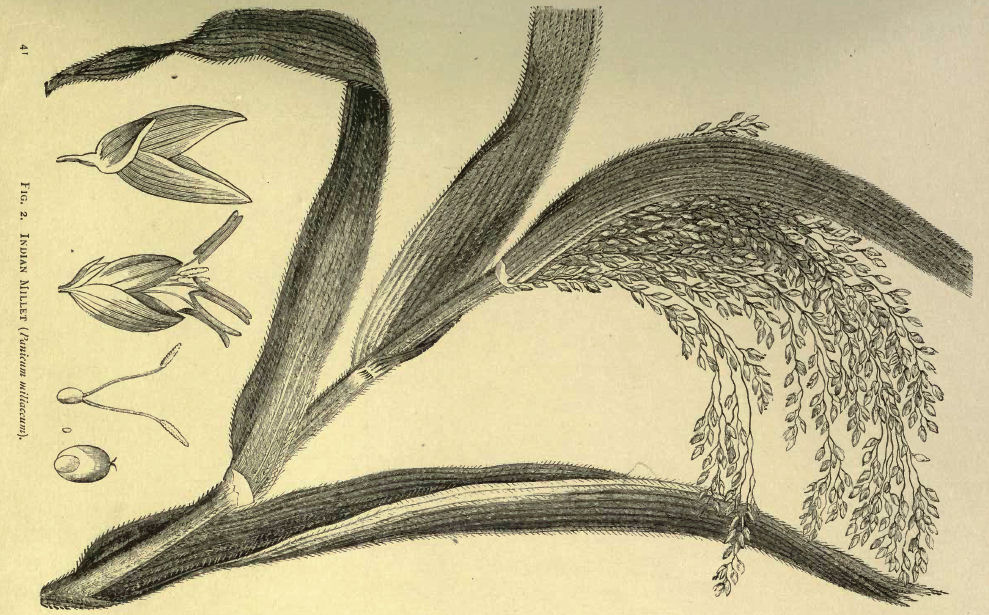

Poaceae - Süßgräser

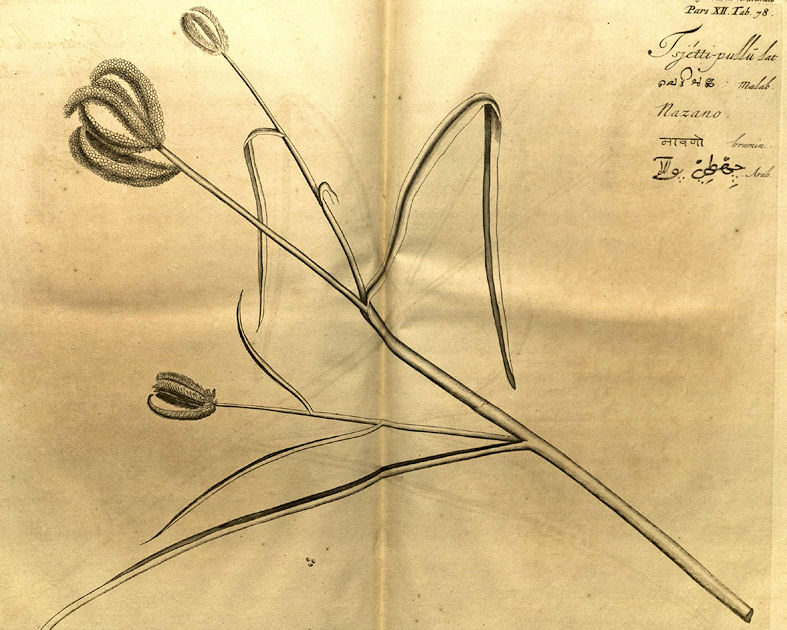

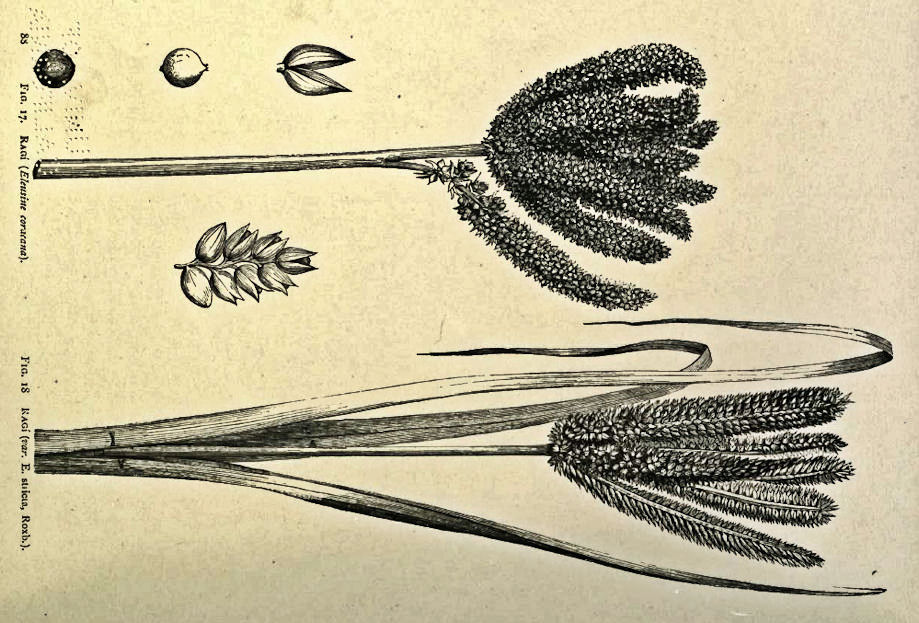

| 16c./d. hareṇu-khaṇḍikau cāsmin koradūṣas tu kodravaḥ हरेणु-खन्डिकौ चास्मिन् कोरदूषस् तु कोद्रवः ।१६ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Paspalum scrobiculatum L. 1767 - Kodo-Hirse - Kodo Millet:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Sort of grain. Paspalum frumentaceum, Koen. or P. Kora, Willd."

कोरदूष - koradūṣa m.: "Gelenkverderber", Paspalum scrobiculatum L. 1767 - Kodo-Hirse - Kodo Millet

Abb.: कोरदूषः । Paspalum scrobiculatum L. 1767 - Kodo-Hirse -

Kodo Millet

[Bildquelle: Church, A. H. (Arthur Herbert) <1834-1915>: Food-grains of

India. -- London, 1886.]

कोद्रव - kodrava m.: Paspalum scrobiculatum L. 1767 - Kodo-Hirse - Kodo Millet

Abb.: क्रोद्रवः । Paspalum scrobiculatum L. 1767 - Kodo-Hirse -

Kodo Millet

[Bildquelle: Forest & Kim Starr. --

http://www.hear.org/starr/images/image/?q=100218-2166&o=plants. -- Zugriff

am 2011-06-29. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: क्रोद्रवः । Paspalum scrobiculatum L. 1767 - Kodo-Hirse -

Kodo Millet

[Bildquelle: Forest & Kim Starr. --

http://www.hear.org/starr/images/image/?q=030405-0428&o=plants. -- Zugriff

am 2011-06-29. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: क्रोद्रवः । Paspalum scrobiculatum L. 1767 - Kodo-Hirse -

Kodo Millet

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. --

http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=PASC6. -- Zugriff am

2007-07-10. -- Public Domain]

"Kodo millet was domesticated in India almost 3000 years ago. It is found across the old world in humid habitats of tropics and subtropics. It is a minor grain crop in India, and an important crop in the Deccan plateau. The fibre content of the whole grain is very high. Kodo millet has around 11% protein, and the nutritional value of the protein has been found to be slightly better than that of foxtail millet but comparable to that of other small millets. As with other food grains, the nutritive value of Kodo millet protein could be improved by supplementation with legume protein."

[Quelle: http://test1.icrisat.org/SmallMillets/Kodo_Millet.htm. -- Zugriff am 2011-06-29]

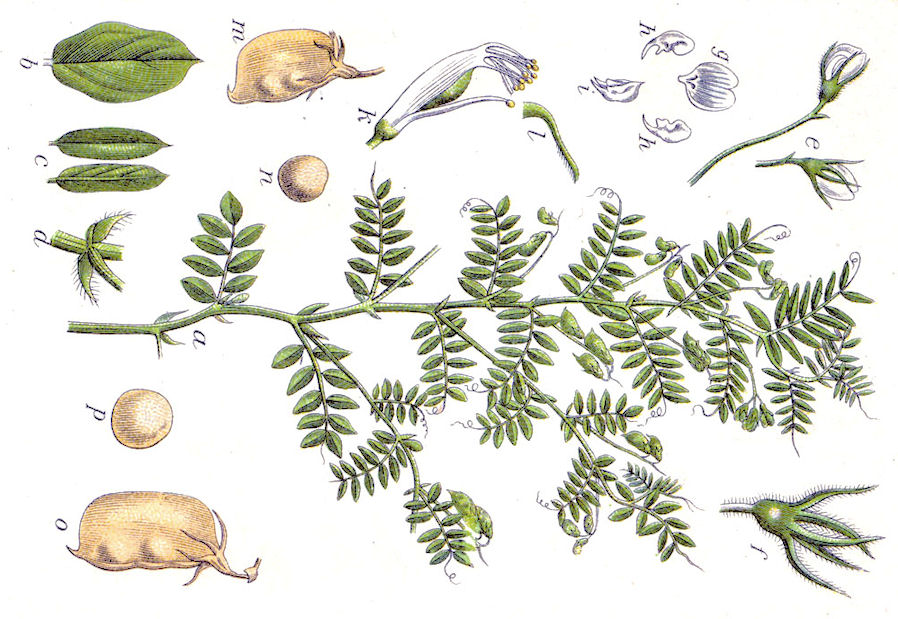

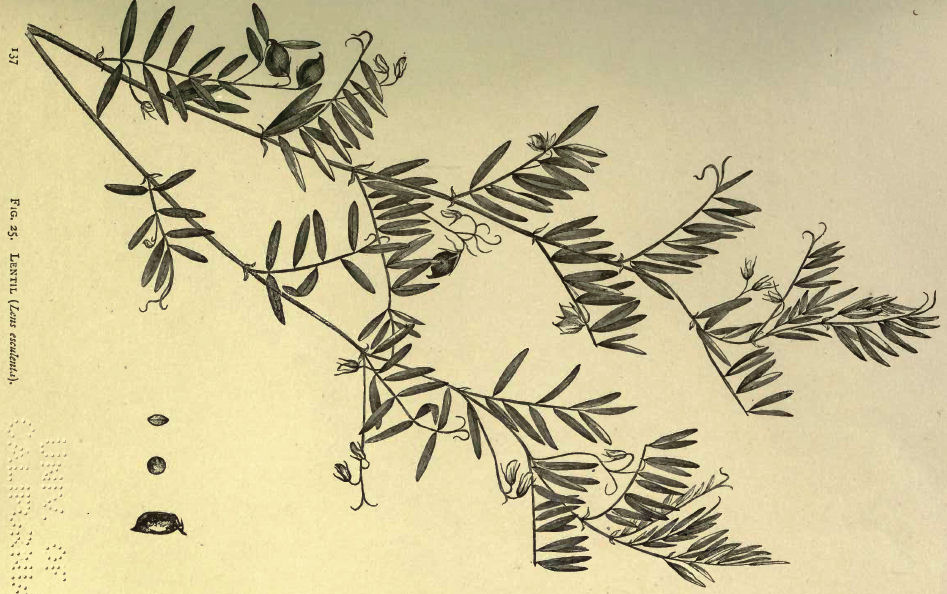

Fabaceae - Hülsenfrüchtler

| 17a./b. maṅgalyako masūro 'tha makuṣṭhaka-mapaṣṭhakau मङ्गल्यको मसूरो ऽथ मकुष्ठक-मपष्ठकौ ।१७ क। [Bezeichnungen für Lens culinaris Medik. 1787 - Gemüse-Linse - Lentil:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Lentil. Ervum lens or Cicer lens."

मङ्गल्यक - maṅgalyaka m.: "Glückbringer", Lens culinaris Medik. 1787 - Gemüse-Linse - Lentil

Abb.: मङ्गल्यकः । Lens culinaris Medik. 1787 - Gemüse-Linse -

Lentil

[Bildquelle: Jacob Sturm, 1796]

Abb.: मङ्गल्यकः । Lens culinaris Medik. 1787 - Gemüse-Linse -

Lentil

[Bildquelle: Church, A. H. (Arthur Herbert) <1834-1915>: Food-grains of

India. -- London, 1886.]

Abb.: मङ्गल्यकाः। Lens culinaris Medik. 1787 - Gemüse-Linse -

Lentil

[Bildquelle: Hohum / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

Abb.: मङ्गल्यकः । Linsen-Geschäft, Nashik -

नाशिक, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Dominic Rivard. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rivard/3261395925/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-29. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung)]

मसूर - masūra m.: Lens culinaris Medik. 1787 - Gemüse-Linse - Lentil

Abb.: मसूरः । Lens culinaris Medik. 1787 - Gemüse-Linse - Lentil,

Mallorca, Spanien

[Bildquelle: Marga Frontera. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ninapetita/4831235376/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-29. -- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: मसूरः । Worfeln von Linsen, Uttar Pradesh

[Bildquelle: Gates Foundation. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/gatesfoundation/5076532362/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-29. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

"THE LENTIL. Lens esculenta, Moench.

[...]

This plant belongs to the tribe Vicieae ; the botanical name by which it is best known is Ervum lens, but the genus Ervum has now been sunk, partly in Lens. The lentil is a branched annual with oblong leaflets, usually 8 in number. The pod is broad and short, and contains 2 seeds, weighing from 1 to 1½ grain apiece in the large seeded variety. The seeds are compressed, and have the form of a bi-convex lens. This plant has been largely cultivated from very ancient times ; its native country is unknown.

The lentil may be grown on almost all soils ; it flourishes upon those which, while light, lie low. It is grown like peas as a cold-weather crop, being sown in September and October, and reaped in March and April. It is commonly cultivated, especially in the North-West Provinces and Madras. It yields from 6½ to 8 maunds per acre, or, if irrigated, 10 to 12 maunds. The yield might be increased if more pains were taken in the selection of seed for sowing, as there are some varieties of the lentil which produce seeds weighing twice as much as the small common sort, and which yet do not make a proportionately increased demand upon the resources of the soil.

[...]

The lentil is generally regarded as a pulse of the second class, inferior to mūng (Phaseolus Mungo), but equal to urhur, the pigeon-pea. It is highly nutritious but somewhat heating; it should be carefully freed from the husk or coat. The bitter substance which occurs in lentils may be removed to some extent by soaking them for a short time in water in which a little carbonate of soda (common washing soda) has been dissolved. The meal of lentils, deprived of their coat, is of great richness, containing generally more albuminoid or flesh-forming matter than bean or pea-flour. The preparations advertised under the names of "Revalenta," "Ervalenta," etc., consist mainly of lentil meal, mixed with the flour of barley or some other cereal, and common salt."

[Quelle: Church, A. H. (Arthur Herbert) <1834-1915>: Food-grains of India. -- London, 1886. -- S. 136 - 139.]

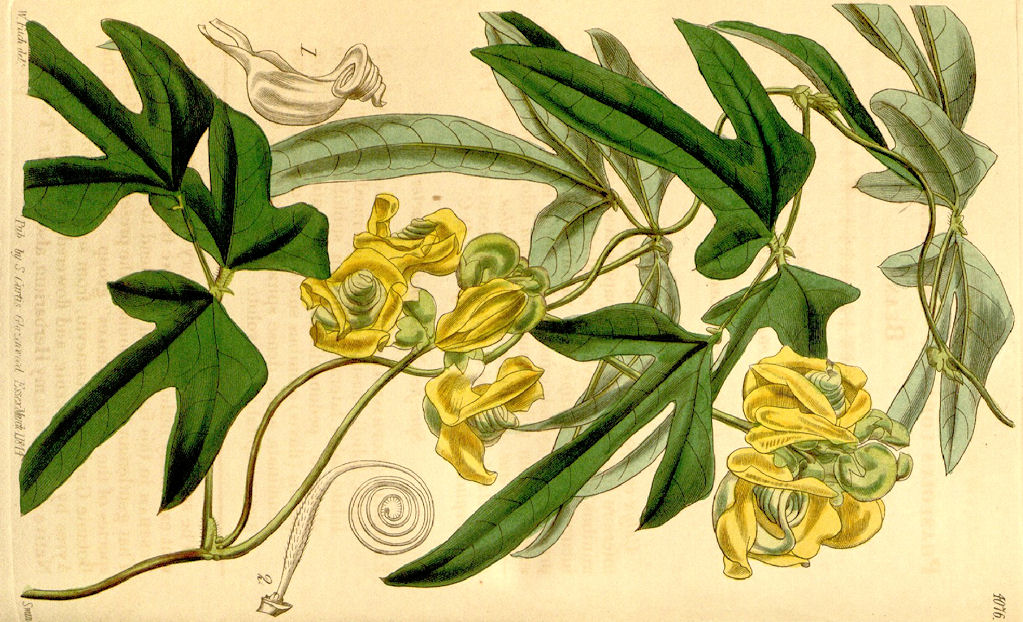

Fabaceae - Hülsenfrüchtler

| 17a./b. maṅgalyako masūro 'tha mayuṣṭhaka-mapaṣṭhakau 17c./d. vanamudgaḥ sarṣape tu dvau tantubha-kadambakau मङ्गल्यको मसूरो

ऽथ मयुष्ठक-मपष्ठकौ ।१७ क।

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Sort of kidney bean. Phaseolus lobatus [= Vigna hookeri ."

मयुष्ठक - mayuṣṭhaka m.: Vigna hookeri

Abb.: मयुष्ठकः ।

Vigna hookeri

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine, v. 70 (1844), Tab. 4076]

Fabaceae - Hülsenfrüchtler

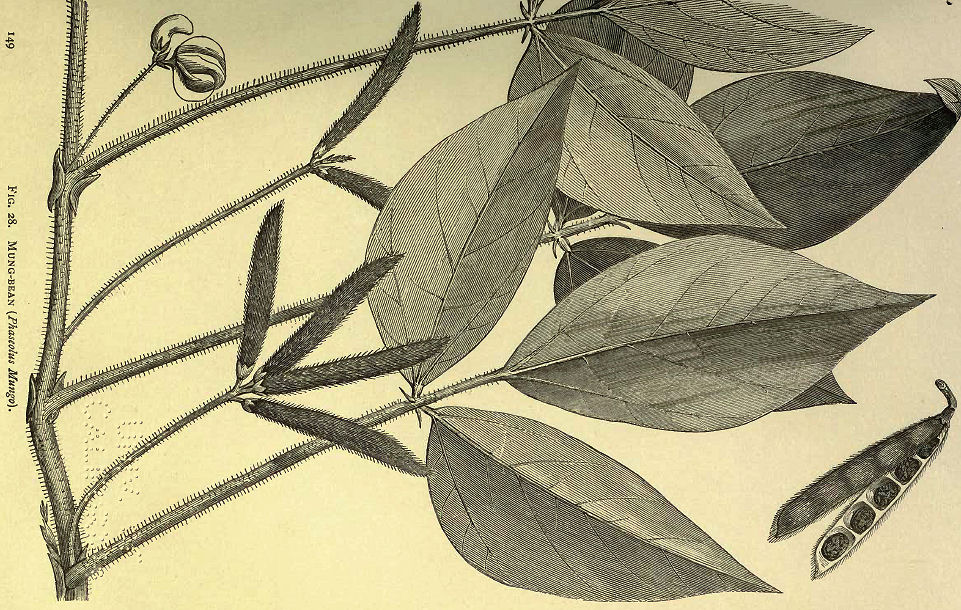

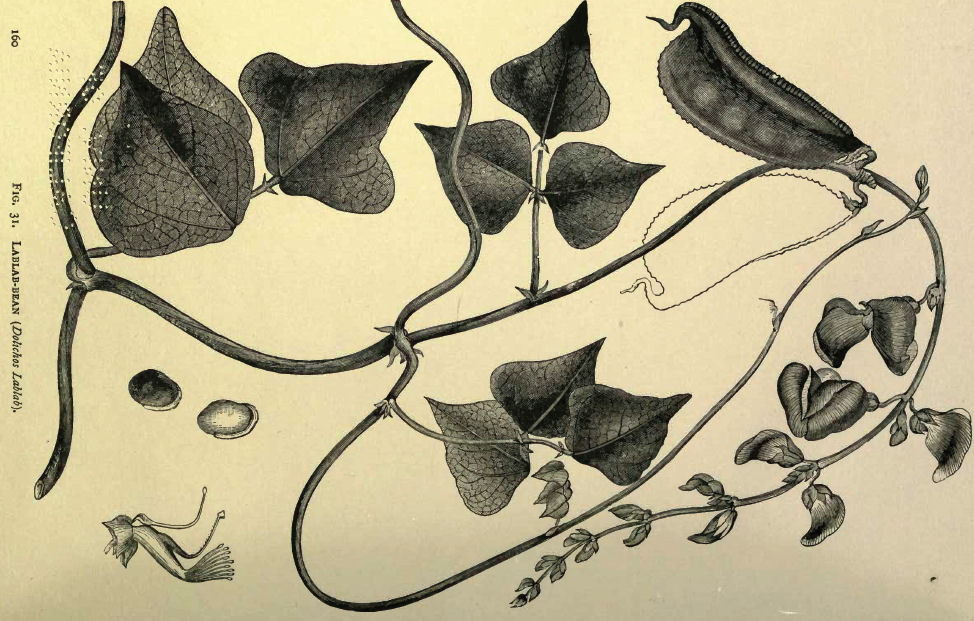

| 17c./d.

vanamudgaḥ sarṣape

tu dvau tantubha-kadambakau वनमुद्गः सर्षपे तु द्वौ तन्तुभ-कदम्बकौ ।१७ ख। [Bezeichnungen für die Wildform von Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek 1954 - Mungbohne - Mungbean:] वनमुद्ग - vanamudga m.: Wald-Mudga = Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek 1954 - Mungbohne - Mungbean |

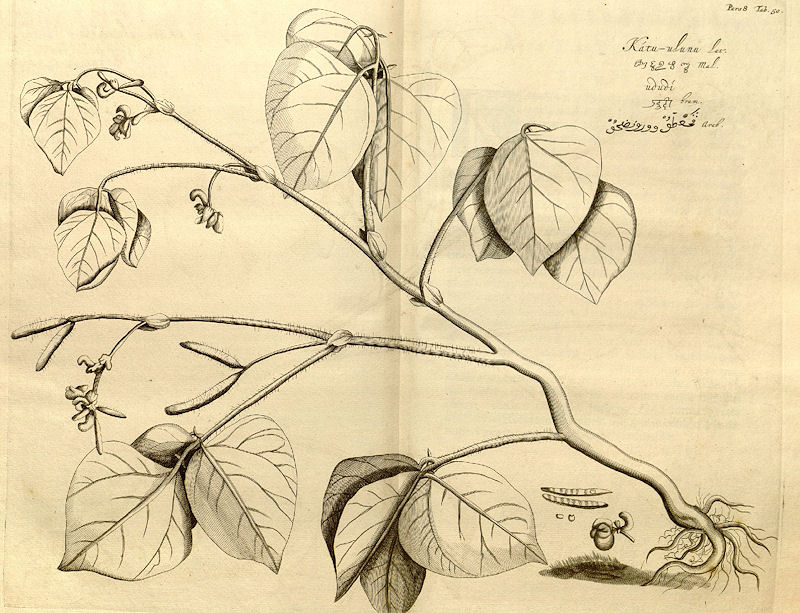

वनमुद्ग - vanamudga m.: Wald-Mudga = Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek 1954 - Mungbohne - Mungbean

Abb.: वनमुग्दः । Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek 1954 - Mungbohne -

Mungbean, Wildform

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1390901887/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-28. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: वनमुग्दः । Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek 1954 - Mungbohne -

Mungbean, Wildform

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1427320564/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-28. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

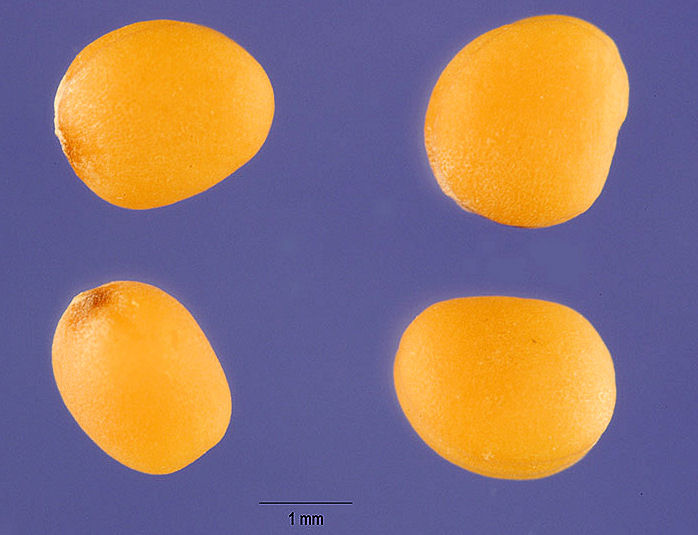

Abb.: वनमुग्दः । Samen

von Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek 1954 - Mungbohne -

Mungbean

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

Abb.: वनमुग्दः । Samen

von Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek 1954 var. radiata - Mungbohne -

Mungbean

[Bildquelle: Tracey Slotta @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

Brassicaceae - Kreuzblütengewächse

|

17c./d.

vanamudgaḥ sarṣape

tu dvau tantubha-kadambakau वनमुद्गः सर्षपे तु द्वौ तन्तुभ-कदम्बकौ ।१७ ख। Bezeichnungen für Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. - Brauner Senf - Indian Mustard (सर्षप - sarṣapa m.):

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Mustard seed. Sinapis dichotoma, Roxb."

Tamil: கடுகு

Andere: Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L. - Stoppelrübe - Field Mustard

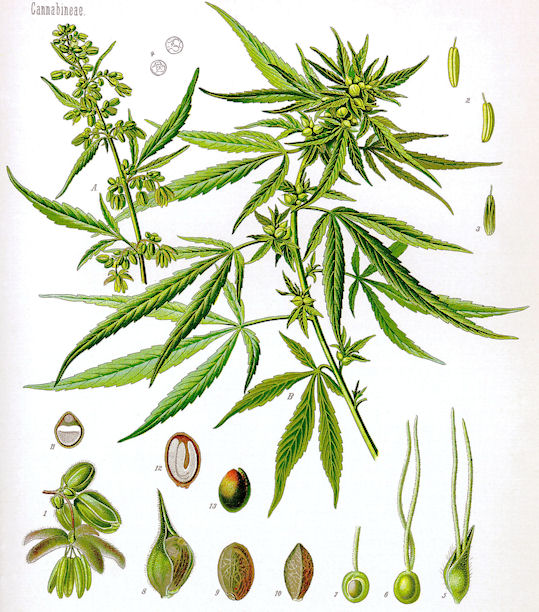

सर्षप - sarṣapa m.: Senf, Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. - Brauner Senf - Indian Mustard

Abb.: सर्षपः । Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. - Brauner Senf - Indian

Mustard

[Bildquelle: Hortus botanicus Vindobonensis / Nicolaus

Josephus Jacquin, 1772]

Abb.: सर्षपः । Samen von Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. - Brauner Senf -

Indian Mustard

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

तन्तुभ - tantubha m.: "Wie Gewebefäden aussehend", Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. - Brauner Senf - Indian Mustard

Abb.: तन्तुभः । Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. - Brauner Senf - Indian

Mustard

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/3393911783/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-29. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

कदम्बक - kadambaka m.: Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. - Brauner Senf - Indian Mustard

Abb.: कदम्बकः । Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. - Brauner Senf - Indian

Mustard, Vagbhil

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1259698272/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-29. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

"BRASSICA JUNCEA, H.f. and T. Fig.—Jacq. Vind. t. 171.

Indian mustard

Hab.—Cultivated universally.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—One of the Sanskrit names for mustard is Āsuri or "the sorceress," because witches are detected by means of mustard oil. By lamplight several cups are filled with water and the oil dropped in, each cup bears the name of one of the suspected women, in the village, and if during the ceremony they observe that the oil takes the form of a woman in any of the cups, they conclude that the person whose name is on that cup is a witch. Mustard is also symbolic of fecundity; in the story of Gul-i-Bakawli, the nymph Bakawli is born again of a peasant woman who had eaten mustard oil extracted from seed grown upon the site of her disappearance. Mustard is mentioned by Greek writers as

ναπυ and σινηπι, and appears to have been used by them as a medicine. There is reason to suppose that the Romans used it as a condiment and medicine. Cf. Pliny 19, 54 and 20, 87, who mentions three varieties. Fée identifies the slender-stemmed mustard of that writer with the Sinapis alba of Linnaeus, the mustard mentioned as having the leaves of rape he considers to be the Sinapis nigra, and that with the leaf of the rocket, the Sinapis erucoides of Linnaeus. Sanskrit writers call mustard seeds Sarshapa and notice two kinds, sidhartha or white mustard (B. campestris), and rajika or brown mustard (probably B. juncea). The first kind is almost exclusively used for the production of the expressed oil, while the brown or black mustards are preferred on account of their greater pungency as rubefacients and for internal administration. The expressed oil of mustard is largely used as an article of diet, and when applied to the skin is considered to keep it soft, cool, and clean, and to promote the growth of hair. In Bengal it is much used by males for rubbing over the body before bathing, females always using cocoanut oil, either plain or perfumed, for the same purpose. Internally the Hindus use mustard combined with other stimulants in dyspepsia and as an emetic; externally they use it in much the same way as we do in Europe, but with the addition of other drugs, most of them of doubtful efficacy. In the Concan the whole seeds, moistened in warm water and sprinkled with lime, are given as a remedy for dyspepsia. In the Makhzan-el-Adwiya three kinds of mustard are noticed. Wild mustard, with small round reddish brown seeds, and two sorts of cultivated mustard, the white and the red. The seeds of the latter are directed to be used for medicinal purposes ; they are described as large and not round. The Mahometans consider mustard to be hot and dry, and to have detergent and digestive properties; they prescribe it internally in many diseases in which they think such remedies are indicated; externally they apply it in a variety of ways as a stimulant and counter-irritant. The list of diseases in which it is recommended, and the method of application or administration in each is too long to reproduce here. (Cf. Makhzan, article Khardal.) Modern research has shown that essential oil of mustard has antiseptic properties and is destructive of bacteria; it is intensely irritant, and if taken internally would act as a powerful irritant poison. The seeds share its properties, and when powdered and mixed with water act upon the skin and mucous membranes as a stimulant of the circulation, causing heat, redness and pain if the application is short, but vesication and much irritation if too prolonged. It is therefore a most valuable counter-irritant in neuralgic pains and internal congestions. Applied as a hip bath it acts as an indirect emmenagogue by stimulating the circulation. Given internally to the extent of a heaped dessert spoonful in a pint of warm water or gruel, mustard flour acts rapidly as an emetic through its irritant action on the mucous membrane of the stomach, and is therefore useful when narcotics have been taken in poisonous doses. In small doses mustard flour is carminative and sialagogue, and promotes digestion by increasing the flow of saliva and gastric juice. The seeds act in the same way, but owing to their mucilaginous coating the action is more prolonged and milder. During excretion mustard irritates the kidneys and causes diuresis.Description.—Four kinds of mustard are generally to be found in the Indian market, namely,

1st, Karachi mustard, B. nigra, var (?)—Globular, of a dark brown colour, surface rough, generally covered with a white pellicle, giving the seeds a grey colour; size about 1/16 of an inch in diameter.

2nd, B. nigra—Seeds globular, dark reddish brown, clean and bright; size about of an inch in diameter; surface rough, but less so than that of the 1st kind.

3rd, B, juncea—Seeds oblong, light reddish brown, clean and bright; length 1/12 of an inch; surface does not appear rough unless magnified.

4tht B. campestris—Seeds very slightly oblong, yellow, or reddish brown, clean and bright; diameter 1/12 of an inch or more; surface smooth to the naked eye, but seen to be finely reticulated under a magnifying glass.

The third kind is preferred by the natives, and may be considered the officinal mustard of India; it has a very bright rich yellow colour when powdered."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 123ff.]

"INDIAN MUSTARDS (BRASSICA JUNCEA, B. CAMPESTRIS AND B. NAPUS).

The Bengal mustards have been studied closely by Major Prain, and according to him there are three distinct types of mustard, which may be distinguished thus :

Indian mustard or Rai, the Sinapis ramosa of Roxburgh and Brassica Juncea of Hooker and Thomson.

Indian Colza or Sarson, the swet-rai of Central Bengal, very tall, grown all over Bengal except Chittagong (plants resembling turnip or swede), the Sinapis glauca of Roxburgh, and Brassica campestris, sub-species genuina, variety glauca of Hooker and Thomson.

Indian Rape or Tori, the Sorshe of Central Bengal, the Sinapis dichotoma of Roxburgh, and Brassica campestris, sub-species napus, variety dichotoma of Hooker and Thomson.

356. Besides these staple varieties, there are some others also cultivated in some parts of Bengal, e.g.

Brassica trilocularis (Ulti Sarson), which is unlike ordinary sarson only in having pendent pods;

Brassica quadrivalvis which is a variety of Sarson which has four rows of seed instead of two ;

Brassica rugosa, Prain, or the Kalimpang rai ;

Brassica rugosa, var. Cuneifolia, Prain, grown by Cacharis and Rajbansis throughout Upper Bengal and Assam ;

Brassica Chinensis or China Cabbage may be also regarded as a mustard.

Indeed Turnip, Cabbage and Cauliflower are botanically closely allied to mustard, all of which are included under the genus Brassica of Linnaeus.

357. The black and white mustards (Brassica nigra and alba) of Europe are not grown in Bengal. It is from these that the mustard of European condiment and hospital poultice, are obtained. The oil of these mustards, though very useful medicinally as a very strong antiseptic, is not so suitable for food as the oil of Indian mustards, though the meal of European mustards is a better condiment.

358. First, Rai, Lahi, Li, or Raichi-rai is grown in all the Divisions of Bengal except Chhota-Nagpur, where it is practically unknown, except in Singhbhum. It is easily recognised by having none of its leaves stem-clasping, and after reaping, its seeds, which are brown, can be readily distinguished from those of Tori or Indian rape, by their small size, and their being distinctly reddish brown all over. From Sarson which has white seeds, or, as occasionally happens, brown seeds, it is easily distinguished. Sarson seeds are always considerably, often very much, larger, and even when brown, have the seed-coat smooth. There are three sub- races of Rai, a tall late kind and two shorter earlier kinds, one of these latter roughing with bristly hairs, the other smooth with darker coloured stems. The taller sub-race is quite absent from Chhota-Nagpur and from Tippera and Chittagong. The shorter sub-races are quite absent from Orissa and are absent from North Bengal, except Tippera. Rai or Rai-shorshe is called chhota-sarisha in Orissa, because the seeds are small.

359. Second, Tori, Latni (Chhota Nagpur) and Sarisha or shorshe (Indian rape) is next in importance to Rai, and it is grown in every district in Bengal except perhaps Saran and Shahabad. It is easily distinguished from Rai by its stem-clasping leaves and its small size. When reaped the seed is recognised as being larger, though of the same colour, and by having a paler spot at the base of the seed ; the seed-coat too is only slightly rough. From Sarson or Indian Colza it is easily distinguished by its smaller size and by its leaves, though stem-clasping, as in Sarson, being less lobed and having much less bloom. The seeds of Tori and ordinary Sarson are much of the same size, but as a rule the seed of Sarson in Bengal is white. When Sarson seeds are brown they are of an amber colour and they have no paler spot. The seed-coat is smooth. The seeds of Sarson are sometimes considerably larger than those of Tori. When this is the case the two are easily distinguished. There are two kinds of Tori, a taller, rather later, and a shorter, and very early kind which is the commoner variety. Both kinds however ripen well ahead of any Rai or any Sarson. The earlier kind of Tori probably does not occur in North-West Tirhut and the later kind is unknown in Eastern Bengal and Chittagong ; with these exceptions both sorts prevail throughout Bengal.

360. Third, Sarson or Indian Colza, the shweti shorshe or simply shweti of Bengal, and Ganga-toria of Orissa, occur in every district except Chittagong, where it is replaced by a different mustard. It is easily distinguished from Rai by its stem-clasping leaves, and from Tori by the greater amount of bloom on its foliage, by its taller stature, its more rigid habit and its thicker and plumper pods. When reaped the seeds are distinguished by their usually white colour; when brown the seeds are distinguished -readily from those of Rai by the larger size, and the smooth seed coat, and from those of Tori by their being of a lighter brown, and by not having a paler spot at the base of the seed. There are two races of sarson, one with erect pods, the Natwa Sarson or Sarson proper and one with pendent pods or Tero Sarson. Each race has two distinct sub-races, one with 2-valved and the other with 3 to 4-valved pods. The forms with hanging pods are not common except in northern Bengal and eastern Tirhut (Purnea), the sub-race with 2-valed pods being almost confined to this area. But the 4-valved kind extends sparingly throughout western Tirhut and crossing the Ganges spreads southwards through southwest Bihar and western Chhotanagpore. The forms with erect pods occur all over Bengal ; the 2-valved subrace, however, is not much grown in Bihar. The 4-valved subrace occupies west Tirhut and west Bihar and extends in a southwest direction to Midnapore. It is also grown in northern and north-eastern Bengal. Roughly speaking, the 2-valved erect Sarson is grown chiefly in Chhotanagpore, Orissa, and in west, central and east Bengal ; the 4-valved erect Sarson is grown chiefly in west Bihar and north Bengal ; and the pendent Sarson occurs in the area to the north of the Ganges beyond the region occupied by the 4-valved Sarson.

361. Fourth, the Chittagong mustard, which is closely allied to European colza.

362. Fifth, the Nepalese mustard, which is the same as the Cabbage-mustard of the Chinese cultivator.

363. Sixth, the China cabbage which is quite distinct from the last has been only lately introduced into Bengal jails.

364. Seventh, Eruca sativa or Taramani (Tiramira) is commonly confounded with mustard. It also belongs to the natural order, Cruciferae and tribe brassiceae. The seeds are compressed and light reddish brown in colour.

365. Tori or Sorshe and Sarson or Swet sorshe are usually sown with wheat or barley, or in gardens with carrots and Ramdana (Amaranth), while Rai is usually grown by itself. They are sown in September i.e., 6 weeks to 2 months before the regular rabi sowings. The sowing of rai is done earlier and it is harvested in February or March, while sarson and tori are sown and harvested later. There are however early and late varieties of all the three crops. When tori or sarson is sown with wheat or barley at the rate of 1½ lbs., per acre, the produce is only 1½ to 2 maunds per acre. Sown by itself, at the rate of 4 to 6 Ibs. per acre, the produce is 4 to 6 maunds. Rai is usually sown at 3 Ibs. per acre and peas are sown afterwards on the same land. Grown in this way the outturn per acre of rai is 3 to 4 maunds. Grown by itself, without peas, scarcely any higher yield is obtained. Rai seed yields less oil than sorshe and shweti-sorshe seeds. In the former case the yield is 10 seers per maund and in the latter 13 to 14 seers. All the three varieties of mustard are sometimes grown as a green manure and sometimes for green fodder only, the plants being cut and given to cattle in January and February, i.e. when they are just in flower. Sometimes a crop of mustard is ploughed in as manure, but this form of green manuring has no such special merit as the ploughing in of dhaincha, sunnhemp, indigo, or barbati."

[Quelle: Mukerji, Nitya Gopal: Handbook of Indian agriculture. -- Calcutta, 1901. -- S. 268 - 272.]

Brassicaceae - Kreuzblütengewächse

| 18a./b. siddhārthas tv eṣa dhavalo godhūmaḥ sumanaḥ samau सिद्धार्थस् त्य् एष धवलो गोधूमः सुमनः समौ ।१८ क। Die weiße Form (d.h. mit weißen Samen) davon heißt सिद्धार्थ - siddhārtha m.: "wirksam", Brassica rapa L. subsp. trilocularis (Roxb.) Hanelt 1986 - Indischer Rübsen - Indian Colza |

Colebrooke (1807): "The white sort. Sinapis glauca, Roxb."

Nach anderen: Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L. - Weiße Rübe - Turnip

Siehe den Kommentar zum Vorhergehenden.

Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L. - Weiße Rübe - Turnip

Abb.: Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L. - Weiße Rübe - Turnip

[Bildquelle: mikiya. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/pink-neko/2535416189/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-29. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

Poaceae - Süßgräser

| 18a./b. siddhārthas tv eṣa dhavalo godhūmaḥ sumanaḥ samau सिद्धार्थस् त्य् एष धवलो गोधूमः सुमनः समौ ।१८ क। [Bezeichnungen für Weizen:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Wheat."

गोधूम - godhūma m.: "Rinder-Dampf", Weizen

Abb.: गोधूमः । Triticum turgidum (Englischer Weizen) subsp.

dicoccum (Schrank ex Schubl.) Thell. or Triticum dicoccon (Emmer)

Cultivar name: KHAPLI, Madhya Pradesh, India, 1926 Maintained by the

National Small Grains Collection.

[Bildquelle: USDA Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN) /

Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

Abb.: गोधूमः । Triticum spp. - Weizen - Wheat

[Bildquelle: O. W. Thomé, 1885]

Abb.: गोधूमः । Triticum aestivum L. 1753 - Saat-Weizen -

Wheat

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1893]

Abb.: गोधूमः । Samen von Triticum aestivum L. 1753 - Saat-Weizen -

Wheat

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

सुमन - sumana m.: "wohlgesinnt", Weizen

Abb.: सुमनः । Pflugfreies Weizenfeld, Pokhar Binda, Maharajganj district,

Bihar

[Bildquelle: Petr Kosina / CIMMYT. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/cimmyt/4777719795/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-29. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: सुमनः । Frau mit Weizenähren, Jamnapur, Bihar

[Bildquelle: Photo: P. Casier@CGIAR. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/cgiarclimate/5477033611/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-29. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: सुमनः । Weizenopfer an Para, Kerala

[Bildquelle: Grande Illusion. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/grandeillusion/80861386/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-30. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielel Benutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

"TRITICUM SATIVUM, Lam. Fig.—Bentl. and Trim., t. 294.

Wheat {Eng.)

Hab. —The Euphrates region. Cultivated in N.-W. India, the Central Provinces, and Bombay.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—Wheat, as the most important of the cereals, has given rise to numerous myths, for an account of which we cannot do better than refer the reader to the late Dr. W. Mannhardt's learned monograph Die Komendämonen (Berlin, 1868). In the myth of Persephone-kora, daughter of Zeus, the god of the heavens, which by their warmth and rain produce fertility, and of Dimeter or Ceres, the maternal goddess of the fertile earth, we perceive that she was conceived as a divine personification of this grain, in summer appearing beside her mother in the light of the upper world, but in the autumn disappearing, and in winter passing her time, like the seed under the earth, with the god of the lower world. As a pendant to the Greek myth, we have the Indian myth of Sita or "the Furrow," husbandry personified, and apparently once worshipped as a kind of goddess. In the Rig-Veda Sita is invoked as a deity presiding over Agriculture, and appears to be associated with Indra. In the Vajananeya, Sita "the Furrow" is personified and addressed, four furrows being required to be drawn at the ceremony when certain stanzas are recited. Sita is so named because she was fabled to have sprung from a furrow made by her father Janaka while ploughing the ground to prepare it for a sacrifice instituted by him to obtain progeny, whence her epithet Ayonija "not womb-born." (Of course, these myths are more or less applicable to all food-grains.) Wheat was used in sacrifice by the Greeks and Romans, and by the Hindus in Vedic times, as an emblem of fertility; it was poured upon the bride at the marriage ceremony, and in Northern India, wheat, millet and rice are still used on such occasions. Wheat, as the most important food-grain, is frequently mentioned by Hippocrates, who calls it

πυρος and mentions three kinds; Pliny also describes several kinds of Triticum. Sanskrit medical writers also mention three kinds of wheat, namely, Mahāgodhuma or large-grained, Madhuli or small-grained, and Nihsuki or beardless; they consider it to be the most nutritive of the food-grains, but not so easily digested as rice.Many varieties of wheat are cultivated in India, and through careless cultivation there is much mixture in the samples brought to market. A number of samples purchased by one of us in the Bombay market and sent to Australia for trial, were, on careful cultivation, found to be all mixed, some of them producing five or six distinct varieties. Indian wheats may be divided roughly into two classes, soft and hard, the former being mostly used for bread-making, and the latter for making a kind of vermicelli and certain other preparations used by the natives. Amongst the Hindus, owing to caste distinctions, the whole process of grinding the corn, separating the flour and making it into cakes, is usually performed by the women of the house, consequently the demand for ready-made flour is limited to the supply of the non-Hindu population, and some of the less particular Hindu castes. In the Indian process of making flour, the wheat, after cleaning, is placed upon a table and thoroughly wetted and the water allowed to drain from it during the night. The next morning, the still moist grain is ground in hand-mills by women. It is then sifted, and as much fine flour and rawa or suji (the heart of the grain) as can be obtained are laid aside. The remainder termed "naka" is again ground in a more powerful mill and an inferior kind of rawa obtained from it. The residue after a third grinding yields a coarse flour and bran. The bazar-made bread is of two kinds, that used by the Mahometans and known as Nān, which is in thin cakes, and loaf-bread introduced by the Portuguese. The former is similar to the bread used in all Mahometan countries, the latter is made with 60 parts fine rawa, 20 second sort or naka rawa, and 20 of first sort flour. A second or inferior kind of bread is also sold. The barm or yeast in use is, where obtainable, the fermenting juice of the palm, elsewhere an artificial barm is prepared.

In some of the large towns a loaf-bread is now made by- Brahmins for the use of the Hindu population, but its use is very limited. In Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, flour and bread made as in Europe is obtainable, and is gradually taking the place of the Portuguese article. Fine flour is also imported from Europe and America, as the excessive proportion of gluten in Indian flour renders it unsuitable for use in making pastry.

Wheaten flour is often used as a dusting-powder to allay the heat and pain of local inflammations, such as burns, scalds, &c., but it is inferior for such purposes to powdered starch. In America an uncooked paste made of the flour has been used with success in diarrhoea. In India flour is much used by the natives for making poultices."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 607ff.]

| 18c./d. syād yāvakas tu kulmāṣaś caṇako harimanthakaḥ स्याद् यावकस् तु कुल्माषश् चणको हरिमन्थकः ।१८ ख। [Bezeichnungen für die saure Absonderung von Feldfrüchten und anderen Früchten:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Half ripe barley. Interpretations differ : some make this awnless barley ; others forced rice (Bor) ; others again, different species of Phaseolus (Rājamāṣa), or of Dolichs (Kulattha)."

Siehe das zur Absonderung von Cicer arietinum im Folgenden Gesagte!

Fabaceae - Hülsenfrüchtler

| 18c./d. syād yāvakas tu kulmāṣaś caṇako harimanthakaḥ स्याद् यावकस् तु कुल्माषश् चणको हरिमन्थकः ।१८ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Chich pea. Cicer arietinum. Some erroneously make these synonymous with the preceding ; others, with Cīnaka, Pnaicum pilosum, Roxb."

चणक - caṇaka m.: Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea

Abb.: चणकः । Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine, v. 49 (1821/22), Tab. 2274]

Abb.: चणकः । Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea,

Deutschland

[Bildquelle: BotBln / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: चणकाः । Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea

[Bildquelle: Sanjay Acharya / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: चणकः । चना मसाला - Chana Masala (aus Kichererbsen)

[Bildquelle: Kirti Poddar --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/feastguru_kirti/2182797448/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-30. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

हरिमन्थक - harimanthaka m.: "gelbe Quirlung, Haris Quirlung", Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea

Abb.: हरिमन्थकः । Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea,

Frankreich

[Bildquelle: Isidro Martínez. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/10770266@N04/4018057525/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-30. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: हरिमन्थकः । Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea,

Frankreich

[Bildquelle: Isidro Martínez. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/10770266@N04/4018816980/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-30. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

Abb.: हरिमन्थकः । Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea,

reife Frucht, Deutschland

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"CICER ARIETINUM, Linn. Fig .— Wight Ic. t. 20; Bot. Mag., t. 2274.

Common Chickpea

Hab.—Unknown. Cultivated in warm 'climates. The seeds and acid exudation.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—This pulse is the Cicer of the Romans. Plautus and Horace speak of 'Cicer frictum,' 'parched gram,' which would appear to have been eaten by the poorer classes just as it is in India now. The Italians call it 'Cece.' The plant is cultivated in the south of Europe and also in India, the leaves and stems are covered with glandular hairs containing oxalic acid, which exudes from them in hot weather and hangs in drops, ultimately forming crystals. In India the seeds form one of the favourite pulses of the natives, being eaten raw or cooked in a variety of ways; the flour is also much used as a cosmetic and in cookery. Cicer is the

ερεβινθος of Dioscorides. The acid liquid, which is obtained by collecting the dew from the Chanaka plant, is mentioned in Sanskrit works under the name of Chanakāmla, and is described as a kind of vinegar having acid and astringent properties, which is useful in dyspepsia, indigestion, and costiveness. Moidīfn Sheriff gives the following description of its collection:—"In a great many parts of India, where C. arietinum is cultivated, a piece of thin and clean cloth is tied to the end of a stick, and the plants are brushed with it early in the morning, so as to absorb the dew, which is then wrung out into a vessel."Dr. Hové (1787) says:—"On the road (to Dholka) we met with numerous woman who gathered the dew of the grain, called by the inhabitants chana, by spreading white calico cloths over the plant, which was about 2 feet high, and then drained it out into small hand jars. They told me that in a short period it becomes an acid, which they use instead of vinegar, and that it makes a pleasant beverage in the hot season when mixed with water." Dr. Hové states that the freshly collected fluid tasted like soft water, but that some which he preserved became after some days strongly acid.

According to Dr. Walker (Bomb. Med. Phys. Trans., 1840, p. 67), the fresh plant put into hot water is used by the Portuguese in the Deccan in the treatment of dysmenorrhea; the patient sits over the steam. He remarks this is only another way of steaming with vinegar. Notices of the acid liquid, its uses by the natives, and mode of collection, are given by Dr. Christie (Madras Lit. Sci. Journ., Vol. IV., p. 476); Dr. Heyne (Tracts, p. 28); Ainslie (Mat. Ind., Vol. II., p. 56)."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 486ff.]

Pedaliaceae - Sesamgewächse

| 19a./b. dvau tile tilapejaś ca tilapiñjaś ca niṣphale द्वौ तिले तिलपेजश् च तिलपिञ्जश् च निष्फले ।१९ क। Bezeichnungen für Sesam (तिल - tila m.: Sesamum indicum L. 1753) ohne Frucht1:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Barren sesamum. Bearing no blossom : or its seed containing no oil."

1 vermutlich = Wildsesam, der kein Öl gibt.

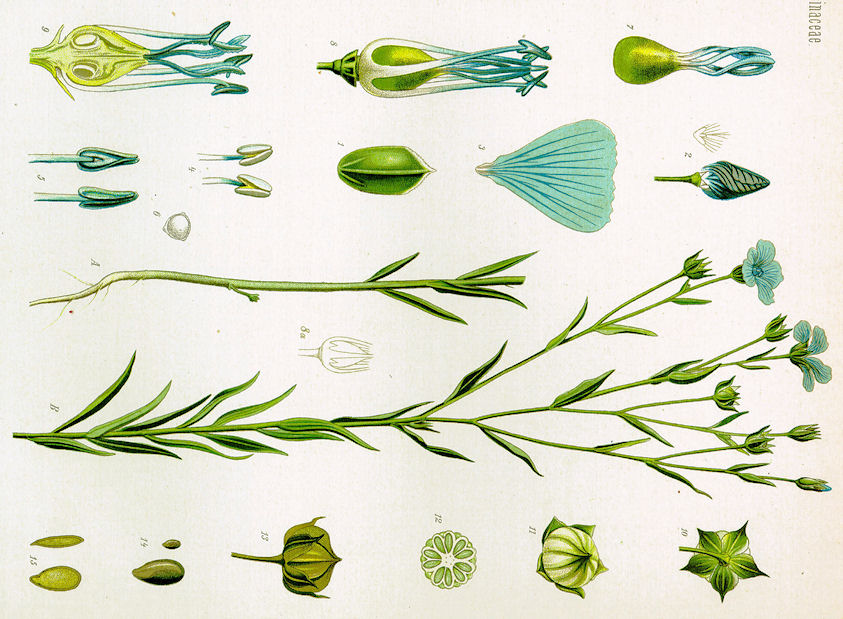

तिल - tila m.: Sesamum indicum L. 1753 - Sesam - Sesame

Abb.: तिलः । Sesamum indicum L. 1753 - Sesam - Sesame

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine, v. 41 (1814/15), Tab. 1688]

तिलपेज - tilapeja m.: unfruchtbarer Sesam

Abb.: तिलपेजः । Wilder Sesam, Indien

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1224182655/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-30. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

तिलपिञ्ज - tilapiñja m.: unfruchtbarer Sesam

Abb.: तिलपिञ्जः । Wilder Sesam, Tungareshwar Wildlife Sanctuary, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/1080592023/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-30. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

"SESAMUM INDICUM, DC. Fig .— Wight III., t. 163; Bot. Mag., t. 1688; Bentl and Trim., t. 198.

Sesame (Eng.)

Hab.—Throughout the warmer parts of India, cultivated. The leaves, seeds r and oil.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—In Hindu mythology Sesamum seed is symbolic of immortality. According to the "Brahma purana," Tila was created by Yama, the " king of death," after prolonged penance. The Grihyasutra of Āśvalāyana directs that in funeral ceremonies in honour of the dead, Sesamum seeds be placed in the three sacrificial vessels containing Kusa grass and holy water, with the following prayer : "O Tila, sacred to Soma, created by the gods during the Gosava (the cow-sacrifice, not now permitted), used by the ancients in sacrifice, gladden the dead, these worlds and us!" Sesamum seeds with rice and honey are used in preparing the funereal cakes called Pindas, which are offered to the Manes in the Sraddh ceremony by the Sapindas "or relations" of the deceased.

On certain festivals six acts are performed with Sesamum seeds, as an expiatory ceremony of great efficacy, by which the Hindus hope to obtain delivery from sin, poverty, and other evils, and secure a place in Indra's heaven. These acts are, tilodvarti, "bathing in water containing the seeds" ; tilasnayi, "anointing the body with the pounded seeds" ; tilahomi, "making a burnt offering of the seeds" ; tilaprada, "offering the seeds to the dead"; tilabhuj, "eating the seeds"; and tilavapi, "throwing out the seeds." Water and Sesamum seeds are offered to the Manes of the deceased. In the first act of Sakuntala this practice (called Til-anjli) is alluded to by the anchorite's daughter in love with King Dushyanta, when she tells her companions that if they do not give their assistance, they will soon have to offer her water and Sesamum seeds. (De Gubernatis.) In proverbial language a grain of Sesamum signifies the least quantity of anything—Til chor so bajjar chor, "who steals a grain will steal a sack" ; Til til ka hisab, "to exact the uttermost farthing."

A worthless person is compared to wild Sesamum (Jartila, Sans.) which yields no oil—In tilon men tel nahin, "there is no good in him." Dutt remarks:—"The word Taila, the Sanskrit for oil, is derived fromTila; it would therefore seem that Sesamum oil was one of the first, if not the first oil manufactured from oil-seeds by the ancient Hindus. The Bhavaprakasa describes three varieties of Til seeds, namely, black, white, and red. Of these the black is regarded as the best suited for medicinal use; it yields also the largest quantity of oil. White Til is of intermediate quality. Til of red or other colours is said to be inferior and unfit for medicinal use. Sesamum seeds are used as an article of diet, being made into confectionery with sugar or ground into meal. Sesamum oil forms the basis of most of the fragrant or scented oils used by the natives for inunction before bathing, and of the medicated oils prepared with various vegetable drugs. It is preferred for these purposes from the circumstance of its being little liable to turn rancid or thick, and from its possessing no strong taste or odour of its own. Sesamum seeds are considered emollient, nourishing, tonic, diuretic, and lactagogue. They are said to be especially serviceable in piles, by regulating the bowels and removing constipation. A poultice made of the seeds is applied to ulcers. Both the seeds and the oil are used as demulcents in dysentery and urinary diseases in combination with other medicines of their class." (Mat. Med. of the Hindus, p. 216.)

Mahometan writers describe the seed under the Arabic name of Simsim. In Africa it is called Juljulān, and in Persia Kunjad. The Mahometan bakers always sprinkle the seeds upon their bread, the sweetmeat-makers mix them with their sweets. The following Delhi street-cry indicates the properties attributed to them by the latter class of people: —

"Til, tikhur, tisi, dana,

Ghi, shakkar men sana,

Khae buddha, hoe javana.""Sesamum, tikhur, and linseed,

Butter and sugar, poppy seed,

Old men it makes quite young with speed." (Fallon.)The oil, which is called in Arabic Duhn-el-hal, is used for the same purpose as olive oil is in Europe. Sesamum is considered fattening, emollient, and laxative. In decoction it is said to be emmenagogue; the same preparation sweetened with sugar is prescribed in cough; a compound decoction with linseed is used as an aphrodisiac; a plaster made of the ground seeds is applied to burns, scalds, &c.; a lotion made from the leaves is used as a hair-wash, and is supposed to promote the growth of the hair and make it black; a decoction of the root is said to have the same properties; a powder made from the roasted and decorticated seed is called Rāhishi in Arabic and Arwah-i-Kunjad in Persian; it is used as an emollient, both externally and internally.

Sesamum (

σησαμον) is frequently mentioned by Greek and Latin authors. Lucian (Pisc. 41) speaks of a σησαμαιος πλχους: this was probably similar to the til ka laddu of India.Sesame oil was an export from Sind to Europe, by way of the Red Sea, in the days of Pliny. In the Middle Ages the plant was known as Suseman or Sempsen, a corruption of the Arabic Simsin or Samsim. It is now called by Europeans, both in India and Europe, Jinjili, Jugeoline, Gigeri, Gengeli, or Gingelly, which appear to be corruptions of the word Juljulān. The oil is one of the most valuable of Indian vegetable oils; it keeps for a long time without becoming rancid, and is produced in large quantities in almost every part of the Peninsula. The following mode of preparation is described in the Jury reports of the Madras Exhibition:—"The method sometimes adopted is that of throwing the fresh seeds, without any cleansing process, into the common mill, and expressing in the usual way. The oil thus becomes mixed with a large portion of the colouring matter of the epidermis of the seed, and is neither so pleasant to the eye nor so agreeable to the taste as that obtained by first repeatedly washing the seeds in cold water, or by boiling them for a short time, until the whole of the reddish-brown colouring matter is removed and the seeds have become perfectly white. They are then dried in the. sun, and the oil expressed as usual. The process yields from 40 to 44 per cent, of a very pale straw-coloured sweet-smelling oil, an excellent substitute for olive oil."

Hydraulic presses are now in use in the more civilized parts of India for extracting the oil, but have as yet by no means superseded the native oil mill.

Sesamum oil may be used for plaster-making, but it takes more oxide of lead than groundnut oil, and does not make so light-coloured or so hard a plaster. After a prolonged trial at the Government Medical Store Department in Bombay, its use was abandoned in favour of the latter oil for the following reasons:—The rolls of Sesame oil plaster soften in hot weather. The plaster has a disagreeable odour. It darkens in colour when kept for any time. For liniments and ointments, except Ung. Hydr. Nitratis, it appears to be a perfectly satisfactory substitute for olive oil. F. H. Alcock (Pharm. Joum. [3], xv., 282) recommends its use in making Lin. Ammoniae B. P. Sesame or Benne leaves, preferably in the fresh state, are much used in America as a demulcent in disorders of the bowels; they yield an abundant mucilage."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 26 - 30.]

Brassicaceae - Kreuzblütengewächse

| 19c./d. kṣavaḥ kṣutābhijanano rājikā kṛṣṇikāsurī क्षवः क्षुताभिजननो राजिका कृष्णिकासुरी ।१९ ख। |

Colebrooke (1807): "Black mustard. Sinapis Ramosa, Roxb."

Siehe oben zu Vers 17c./d.!

Poaceae - Süßgräser

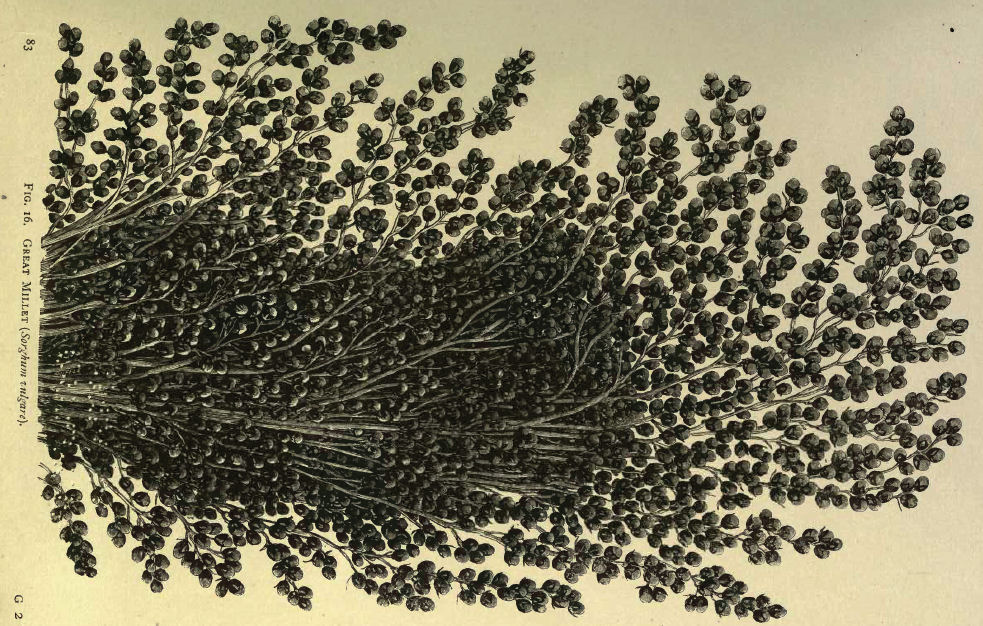

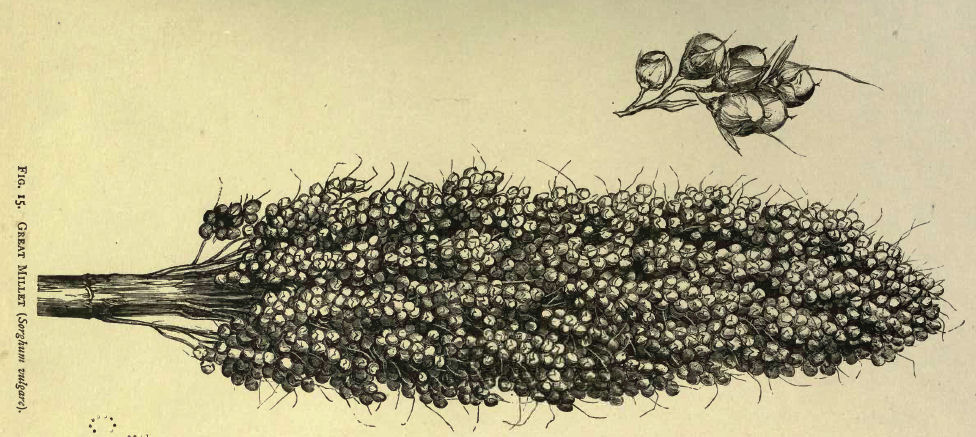

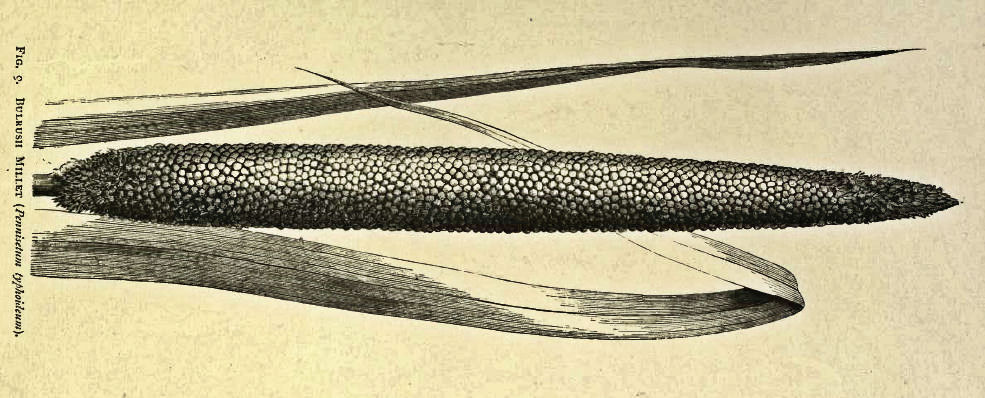

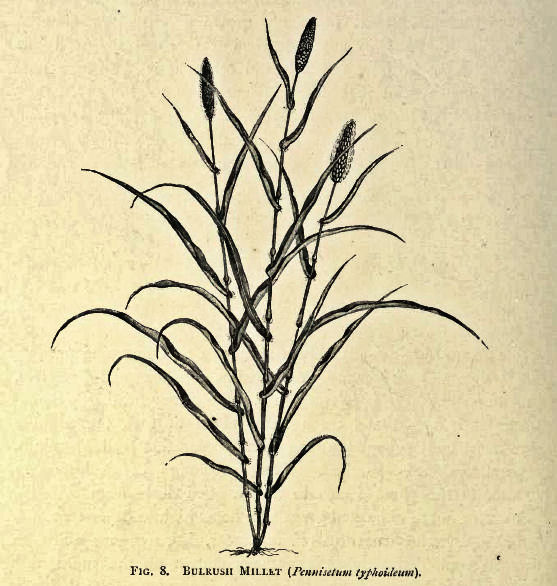

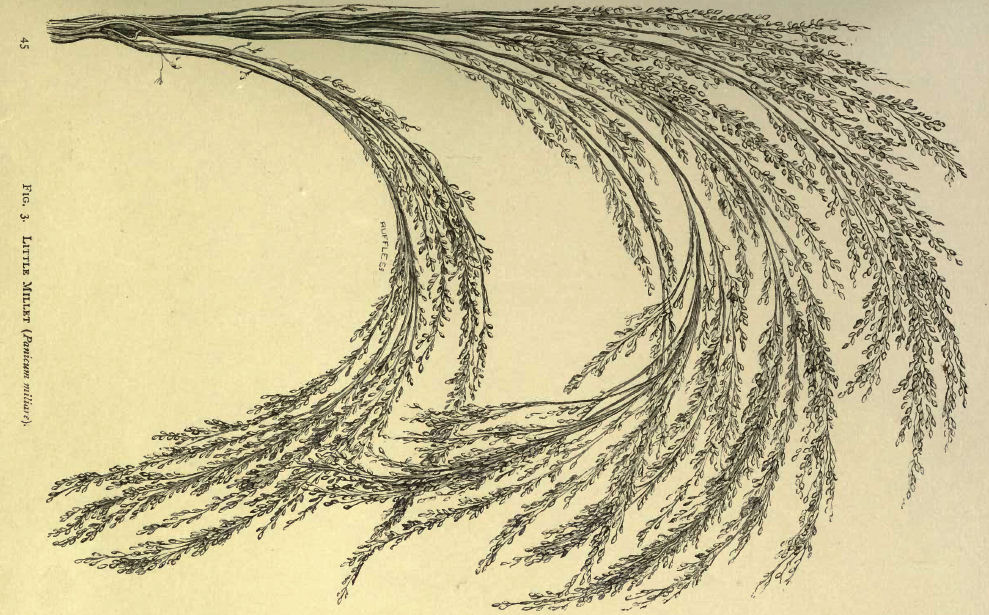

| 20a./b. striyau kaṅgu-priyaṅgū dve atasī syād umā kṣumā स्त्रियौ कङ्गु-प्रियङ्गू द्वे अतसी स्याद् उमा क्षुमा ।२० क। [Bezeichnungen für Setaria italica P. Beauv. 1812 - Kolbenhirse - Italian Millet:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Panick seed. Panicum Italicum."

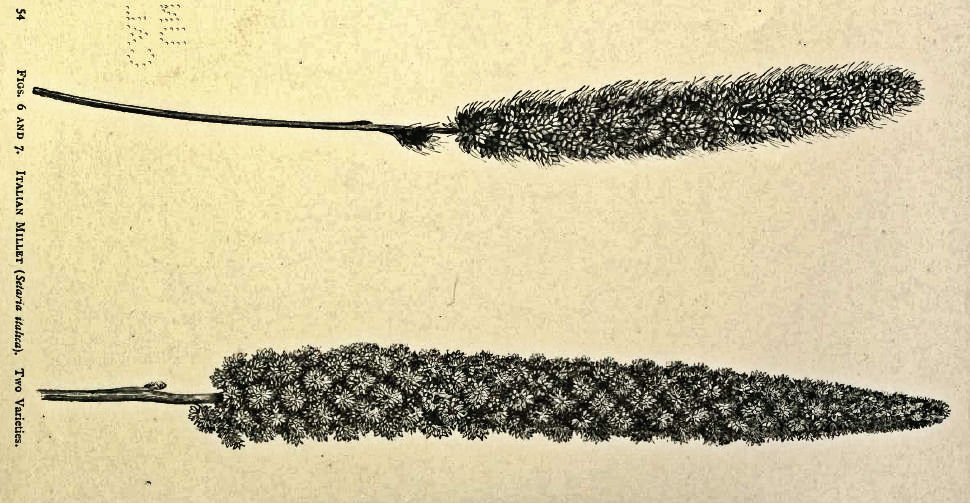

कङ्गु - kaṅgu f.: Setaria italica P. Beauv. 1812 - Kolbenhirse - Italian Millet

Abb.: कङ्गुः । Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv. 1812 -

Kolbenhirse - Italian Millet

[Bildquelle: Church, A. H. (Arthur Herbert) <1834-1915>: Food-grains of

India. -- London, 1886.]

Abb.: कङ्गुः । Samen von Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv. 1812 -

Kolbenhirse - Italian Millet

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

Abb.: Mahlen von Hirse, Bhadrajun, Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: rachel dale. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rdale/5644012071/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-30. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

प्रियङ्गु - priyaṅgu f.: Setaria italica P. Beauv. 1812 - Kolbenhirse - Italian Millet

Abb.: प्रियङ्गुः । Setaria italica P. Beauv. 1812 - Kolbenhirse -

Italian Millet, Taiwan - 臺灣

[Bildquelle: 素珍 徐.

--

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jennyhsu47/4433932547/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-30. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]