|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 15. vaiśyavargaḥ (Über Vaiśyas). -- 5. Vers 34c - 44c (Kochen II: Gemüse, Gewürze). -- Fassung vom 2012-07-13. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa7/amara215e.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-07-13

Überarbeitungen:

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

Bei der Identifikation der lateinischen Pflanzennamen folge ich, wenn immer es möglich ist:

Bhāvamiśra <16. Jhdt.>: Bhāvaprakāśa of Bhāvamiśra : (text, English translation, notes, appendences and index) / translated by K. R. (Kalale Rangaswamaiah) Srikantha Murthy. -- Chowkhamba Varanasi : Krishnadas Academy, 1998 - 2000. -- (Krishnadas ayurveda series ; 45). -- 2 Bde. -- Enthält in Bd. 1 das SEHR nützliche Lexikon (nigaṇṭhu) Bhāvamiśras.

Pandey, Gyanendra: Dravyaguṇa vijñāna : materia medica-vegetable drugs : English-Sanskrit. -- 3. ed. -- Varanasi : Chowkhamba Krishnadas Academy, 2005. -- 3 Bde. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN: 81-218-0088-9 (set)

Wo möglich, erfolgt die aktuelle Benennung von Pflanzen nach:

Zander, Robert <1892 - 1969> [Begründer]: Der große Zander : Enzyklopädie der Pflanzennamen / Walter Erhardt ... -- Stuttgart : Ulmer, ©2008. -- 2 Bde ; 2103 S. -- ISBN 978-3-8001-5406-7.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Pflanzen wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut

ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

WARNUNG: dies

ist der Versuch einer Übersetzung und Interpretation eines altindischen

Textes. Es ist keine medizinische Anleitung. Vor dem Gebrauch aller hier

genannten Pflanzen wird darum ausdrücklich gewarnt. Nur ein erfahrener, gut

ausgebildeter ayurvedischer Arzt kann Verschreibungen und Behandlungen

machen! Die Bestimmung der Pflanzennamen beruht weitgehend auf Vermutungen

kompetenter Āyurvedaspezialisten.

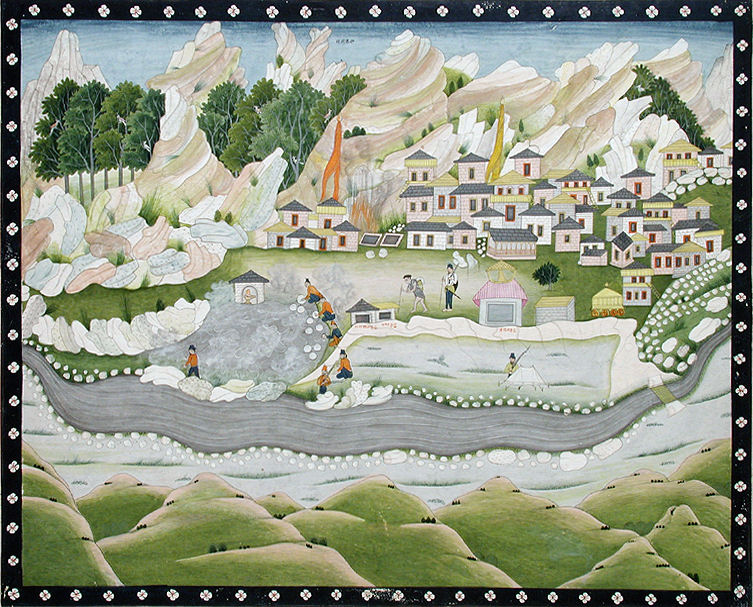

Abb.: Zubereitung von Chapatis (चपाती)

an den heißen Quellen von Manikarna, Mandi - मंडी, Himachal Pradesh

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of

Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4837863117/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-24. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

| 34c./d. astrī śākaṃ haritakaṃ śigrur asya tu nāḍikā अस्त्री शाकं हरितकं शिग्रुर् अस्य तु नाडिका ।३४ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Gemüse:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A potherb."

Der Bhāvaprakāśa (I, 6) nennt folgende śāka:

patra-śāka n. -

Blätter-Gemüse

vāstuka n.: Chenopodium album L. 1753 - Gewöhnlicher Weißer Gänsefuß

potakī f.: Basella alba L. 1753 - Indischer Spinat - Malabar Nightshade

māriṣa m.: Amaranthus blitum L. 1753 - Fuchsschwanz - Amaranth

taṇḍulīyaka m.: Amaranthus spinosus L. - Dorniger Fuchsschwanz - Thorny Amaranth

pālakyā f.: Spinacia oleracea L. 1753 - Spinat - Spinach

kāla-śāka n.: Corchorus capsularis L. 1753 - Rundkapsel-Jute - White Jute

paṭṭa-śāka m.: Corchorus olitorius L. 1753 - Langkapsel-Jute - Nalta Jute

kalambī f.: Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. 1775 - Wasserspinat - Water Spinach

loṇī f.: Portulaca quadrifida L. 1767 - Chickenweed

ghoṭikā f.: Portulaca oleracea L. 1753 - Portulak - Garden Purslane

cāṅgerī f.: Oxalis corniculata L. 1753 - Hornfrüchtiger Sauerklee - Yellow Sorrel

cukrikā f.: Rumex vesicarius L. 1753 - Indischer Sauerampfer - Bladder Dock

cañcukī f.: Corchorus fascicularis Lam. 1786 - Grubweed

hilamocikā f.: Enhydra fluctuans Lour. - Water Cress

śitivāra m.: Marsilea minuta L. - Dwarf Waterclover

mūlaka-patra n.: Blätter von Raphanus sativus L. 1753 - Rettich - Radish

droṇapuṣpī f.: Leucas cephalotes (Roth) Spreng. 1825

yavāni-śāka n.: Blätter von Trachyspermum ammi (L.) Sprague 1929 - Indischer Kümmel - Kummel

dadrughna-patra n.: Blätter von Cassia tora L. 1753

sehuṇḍa-dala n.: Blätter von Euphorbia sp. - Wolfsmilch - Spurge

parpaṭa m.: Fumaria indica (Hausskn.) Pugsley 1919

gojihvā f.: Onosma bracteatum Wall. 1824

paṭola-patra n.: Blätter von Trichosanthes dioica Roxb. 1832

guḍūcī-patra n.: Blätter von Tinospora malabarica Miers 1851

kāsamarda m.: Cassia occidentalis L. 1753 - Negro Coffee

caṇaka-śāka n.: Blätter von Cicer arietinum L. 1753 - Kichererbse - Chick Pea

kalāya-śāka n.: Blätter von Lathyrus sativus L. 1840 - Saat-Platterbse - Chickling Pea

sārṣapa-śāka n.:

Blätter von Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L. -

Stoppel-Rübe - Turnip

puṣpa-śāka n.:

Blüten-Gemüse

agasti-puṣpa n.: Blüten von Sesbania grandiflora (L.) Pers. 1807 - Großblütige Sesbanie - Wisteria Tree

kadalī-puṣpa n.: Blüten von Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 - Ess-Banane - Plantain

śigru-puṣpa n.: Blüten von Moringa oleifera Lam. 1783 - Meerrettichbaum - Horseradish Tree

śālmalī-puṣpa n.:

Blüten von Bombax ceiba L. 1753 - Roter Seidenwollbaum -

Bombax

phala-śāka n.:

Frucht-Gemüse

kūṣmāṇḍa n.: Benincasa hispida (Thunb. ex Murray) Cogn. 1881 - Wachs-Kürbis - Wax Gourd

kūṣmāṇḍī f.: Cucurbita pepo L. 1753 - Zucchini

alābū f.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis - Calabash Gourd

kaṭutumbī f.: Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl. 1930 - Flaschenkürbis - Bitter Gourd

karkaṭī f.: Cucumis melo L. 1753 Conomon Grp. - Gemüse-Melone - Oriental Pickling Melon

ciciṇḍā f.: Trichosanthes cucumerina var. anguina (L.) Haines 1922 - Weiße Schlangenhaargurke - Snake Gourd

kāravella n.: Momordica charantia L. 1753 - Balsambirne - Bitter Melon

mahākośātakī f.: Luffa aegyptiaca Mill. 1768 - Schwammgurke - Loofah

rājakośātakī f.: Luffa acutangula (L.) Roxb. 1832 - Gerippte Schwammgurke - Angled Loofah

paṭola m.: Trichosanthes dioica Roxb. 1832

bimbī f.: Coccinia grandis (L.) Voigt 1845 - Große Scharlachranke - Ivy Gourd

pustaśimbī f., śimbī f.: Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet 1826 - Faselbohne - Lablab

kolaśimbī f.: ?

śobhāñjana-phala n.: Früchte von Moringa oleifera Lam. 1783 - Meerrettichbaum - Horseradish Tree

vṛntāka n.: Solanum melongena L. 1753 - Aubergine - Eggplant

ḍiṇḍiśa m.: Praecitrullus fistulosus (Stocks) Pangalo 1944

piṇḍāra n.: Tamilnadia uliginosa (Retz.) Tirveng. & Sastre 1979

karkoṭī f.: Momordica dioica Roxb. 1805

ḍoḍikā f.: "not correctly identified"

kaṇakārī-phala n.:

Früchte von Solanum surattense Burm. 1768

nāla-śāka n.:

Stängel-Gemüse

sārṣapa-nāla n.:

Stängel von Blätter von Brassica rapa subsp. rapa L. -

Stoppel-Rübe - Turnip

kanda-śāka n.:

Wurzel-Gemüse

sūraṇa n.: Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson 1977 - Elefantenkartoffel - Telingo Potato

āluka n.: Dioscorea sp. L. 1753 - Yamswurzel - Yam

mūlaka n.: Raphanus sativus L. 1753 - Rettich - Radish

gṛñjana n.: Daucus carota subsp. sativus (Hoffm.) Schübl. et G. Martens - Karotte - Carrot

kadalī-kanda m.: Wurzeln von Musa x paradisiaca L. 1753 - Ess-Banane - Plantain

māna-kanda m.: Alocasia macrorrhizos (L.) G. Don 1839 - Riesenblättriges Pfeilblatt - Giant Taro

vārāhī-kanda m.: Dioscorea bulbifera L. 1753 - Yamswurzel - Air Potato

hastikarṇā f.: Leea macrophylla Roxb. ex Hornem. 1813

kemuka n.: Costus speciosus (J. König) Sm. 1791 - Prächtige Kostwurz - Malay Ginger

kaseru n.: Actinoscirpus grossus (L. f.) Goetgh. & D. A. Simpson var. kysoor (Roxb.) Noltie 1994

śāluka n.:

Wurzeln von Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. 1788 - Indischer Lotus -

Lotus

saṃsvedaja-śāka n.: aus

(Boden-)Schweiß entstandenes Gemüse = Pilze

bhūmicchatra n. / śikīndhraka n.: Agaricus campestris L. 1753 - Wiesenchampignon - Field Mushroom

शाक - śāka m., n.: Gemüse

Abb.: शाकाः । Kolkata - কলকাতা,

West Bengal

[Bildquelle: Donna Winton. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dwinton/396094294/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-10. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

हरितक - haritaka n.: Grünzeug, Gras, Gemüse

Abb.: हरितकम् । Gemüsefelder, Raithal - रैथल, Uttarakhand

[Bildquelle: Trees for the Future. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/plant-trees/4478895427/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-10. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

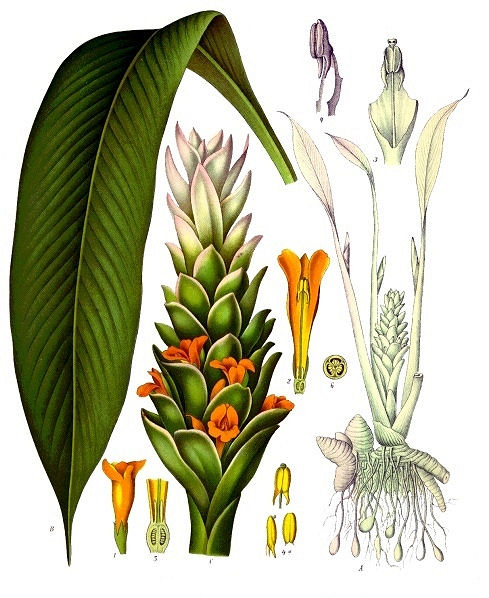

शिग्रु - śigru m.:

Moringa oleifera Lam. 1783 - Meerrettichbaum - Horse radish Tree (Blätter und Blüten davon dienen als Gemüse), GemüseMoringa: Moringaceae - Bennussgewächse

Abb.: शिग्रुः । Moringa oleifera Lam. 1783 - Meerrettichbaum -

Horseradish Tree

[Bildquelle: Icones plantarum rariorum / editae Nicolao Josepho Jacquin. --

Vol. 3. -- 1786 - 1793. -- Tab. 461]

Abb.: शिग्रवः । Gaṇeśa-Statue aus Gemüse, Gaṇeśa Caturthī - गणेशचतुर्थी -

விநாயக சதுர்த்தி, Chennai - சென்னை,

Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: McKay Savage. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mckaysavage/3058676351/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-10. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

| 34c./d. astrī śākaṃ haritakaṃ śigrur asya tu nāḍikā 35a./b. kalambaś ca kaḍambaś ca veṣavāra upaskaraḥ

अस्त्री शाकं हरितकं शिग्रुर् अस्य तु नाडिका

।३४ ख। Der Stängel (nāḍikā f.: Röhre) von Gemüse heißt:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Its stalk."

कलम्ब - kalamba m.: Stängel einer Gemüsepflanze

Abb.: कलम्बाः । Chennai - சென்னை,

Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: McKay Savage. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mckaysavage/3986989108/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-10. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

कडम्ब - kaḍamba m.: Stängel einer Gemüsepflanze

Abb.: कडम्बाः । Guwahati -

গুৱাহাটী, Assam

[Bildquelle: nalin a. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/nalinandworld/2602469146/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-10. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

| 35a./b. kalambaś ca kaḍambaś ca veṣavāra upaskaraḥ कलम्बश् च कडम्बश् च वेषवार उपस्करः ।३५ क। [Bezeichnungen für Zutat, Gewürz:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A condiment."

उपस्कर - upaskara m.: Zutat, Zubehör, Gerät, Gewürz

Abb.: उपस्कराः । Orcha - ओरछा, Madhya Pradesh

[Bildquelle: krebsmaus07. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/koadla/5105341568/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: उपस्कराः । Diu - दीव, Daman & Diu

[Bildquelle: Gerardo Diego

Ontiveros. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/germeister/297636465/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

Tamarindus: Caesalpiniaceae - Johannisbrotgewächse

Garcinia: Clusiaceae

| 35c./d. tintiḍīkaṃ ca cukraṃ ca vṛkṣāmlam atha vellajam तिन्तिडीकं च चुक्रं च वृक्षाम्लम् अथ वेल्लजम् ।३५ ख। [Bezeichnungen für eine saure Brühe, insbes. Brühe von Tamarindus indica L. 1753 - Tamarinde - Tamarind bzw. von Garcinia indica (Thouars) Choisy 1824 - Mangostane - Mangosteen:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Acid seasoning."

तिन्तिडीक - tintiḍīka n.: Frucht von Tamarindus indica L. 1753 - Tamarinde - Tamarind, eine saure Brühe, insbes. von Tamarindenfrucht

चुक्र - cukra n.: Fruchtessig, eine saure Brühe, insbes. aus der Frucht von Tamarindus indica L. 1753 - Tamarinde - Tamarind

Abb.: तिन्तिडीकम् । Frucht

von Tamarindus indica L. 1753 - Tamarinde - Tamarind

[Bildquelle: dinesh_valke. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dinesh_valke/2174726661/. -- Zugriff am

2010-10-13. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: तिन्तिडीकम् । Mus von

Tamarindus indica L. 1753 - Tamarinde - Tamarind, Indien

[Bildquelle: Rick Bradley. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/rickbradley/4271306325/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: चुक्रम् । Tamarinden-Konzentrat, Cuttack - କଟକ, Orissa

[Bildquelle: Emily Barney. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ebarney/5502513817/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

"Tamarindus Indica (Linn.) N. O. Leguminosae. Tamarind or Indian Date

Description.--Tree, 80 feet; [...]

Fl. May-June.

W. & A. Prod. i. 285.--Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii. 215. -- Rheede i. 23.

Peninsula. Bengal.

Medical Uses.—The pulp of the pods is used both in food and in medicine. It has a pleasant juice, which contains a larger proportion of acid with the saccharine matter than is usually found in acid fruit. Tamarinds are preserved in two ways : first, by throwing hot sugar from the boiler on the ripe pulp; but a better way is to put alternate layers of tamarinds and powdered sugar into a stone jar. By this means they preserve their colour, and taste better. They contain sugar, mucilage, citric acid, tartaric and malic acids. In medicine, the pulp taken in quantity of half an ounce or more proves gently laxative and stomachic, and at the same time quenches the thirst. It increases the action of the sweet purgatives cassia and manna, and weakens that of resinous cathartics. The seed is sometimes given by the Yytians in cases of dysentery, and also as a tonic, and in the form of an electuary. In times of scarcity the poor eat the tamarind-stones. After being roasted and soaked for a few hours in water, the dark outer skin comes off, and they are thon boiled or fried. In Ceylon, a confection prepared with the flowers is supposed to have virtues in obstructions of the liver and spleen. A decoction of the acid leaves of the tree is employed externally in cases requiring repellent fomentation. They are also used for preparing collyria, and taken internally are supposed a remedy in jaundice. The natives have a prejudice against sleeping under the tree, and the acid damp does certainly affect the cloth of tents if they are pitched under them for any length of time. Many plants do not grow under its shade, but it is a mistake to suppose that this applies to all herbs and shrubs. In sore-throat the pulp has been found beneficial as a powerful cleanser. The gum reduced to fine powder is applied to ulcers; the leaves in infusion to country sore eyes and foul ulcers. The stones, pulverised and made into thick paste with water, have the property when applied to the skin of promoting suppuration in indolent boils.—A indie. Thornton. Don,

Economic Uses.—The timber is heavy, firm, and hard, and is converted to many useful purposes in building. An infusion of the leaves is used in Bengal in preparing a fine fixed yellow dye, to give those silks a green colour which have been previously dyed with indigo. Used also simply as a red dye for woolen stuffs. In S. India a strong infusion of the fruit mixed with sea-salt is used by silversmiths in preparing a mixture for cleaning and brightening silver. The pulverised seeds boiled into a paste with thin glue form one of the strongest wood-cements. The tree is one of those preferred for making charcoal for gunpowder—(Lindley. Roxb.). The tree is of slow growth, but is longer-lived than most trees. The timber is used for mills and the teeth of wheels, and whenever very hard timber is requisite. It is much prized as fuel for bricks. Its seeds should be sown where it is to remain, and it may be planted in avenues alternately with short-lived trees of quicker growth. From the liability of this tree to become hollow in the centre, it is extremely difficult to get a tamarind-plank of any width.—(Best's Report to Bomb. Govt., 1863.) There is a considerable export trade of tamarinds from Bombay and Madras. In 1869-70 were exported from the latter Presidency 10,071 cwt., valued at Es. 33,009 ; and from the former 6232 cwt., valued at Rs. 26,209.—Trade Reports."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"TAMARINDUS INDICA, Linn. [...]

History, Uses, &C—There would appear to be little doubt that the Tamarind tree is a native of some part of India, probably the South. It is found in a cultivated or semi-cultivated state almost everywhere, and the fruit, besides being an important article of diet, is valued by the Hindus as a refrigerant, digestive, carminative and laxative, useful in febrile states of the system, costiveness, &c. The ashes of the burnt suber are used as an alkaline medicine in acidity of the urine and gonorrhoea, the pulp and also the leaves (puliyam-gali, Tam.), are applied externally in the form of a poultice to inflammatory swellings.

The Sanskrit names of the Tamarind are Tintidi and Amlika. The word 'Tamarind' appears to be derived from the Arabic Tamar-Hindi (Indian date), and it was doubtless through the Arabians that a knowledge of the fruit passed during the Middle Ages into Europe, where, until correctly described by Garcia d'Orta, it was supposed to be produced by a kind of Indian palm.

The author of the Makhzan-el-Adwiya describes two kinds, viz., the red, small-seeded Guzerat variety, and the common reddish brown. The first is by far the best. Mahometan physicians consider the pulp to be cardiacal, astringent and aperient, useful for checking bilious vomiting, and for purging the system of bile and adust humours; when used as an aperient it should be given with a very small quantity of fluid. A gargle of Tamarind water is recommended in sore throat. The seeds are said to be a good astringent, boiled they are used as a poultice to boils, pounded with water they are applied to the crown of the head in cough and relaxation of the uvula. The leaves crushed with water and expressed yield an acid fluid, which is said to be useful in bilious fever, and scalding of the urine; made into a poultice they are applied to reduce inflammatory swellings and to relieve pain. A poultice of the flowers is used in inflammatory affections of the conjunctiva; their juice is given internally for bleeding piles. The bark is considered to have astringent and tonic properties. (Makhzan-el-Adwiya.)

The natives consider the acid exhalations of the Tamarind tree to be injurious to health, and it is stated that the cloth of tents allowed to remain long under the trees becomes rotten. Plants also are said not to grow under them, but this is not universally the case, as we have often seen fine crops of Andrographis paniculata and other shade loving plants growing under Tamarind trees. Mr. J. G. Prebble has brought to our notice a peculiar exudation from an old tamarind tree. It consists almost entirely of oxalate of calcium, and flows from the tree in a liquid or syrupy state, but afterwards dries into white crystalline masses."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 532f.]

वृक्षाम्ल - vṛkṣāmla n.: Frucht von Garcinia indica (Thouars) Choisy 1824 - Mangostane - Mangosteen

Abb.: वृक्षामानि । Garcinia indica (Thouars) Choisy 1824 - Mangostane

- Mangosteen

[Bildquelle: Subray Hegde / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: वृक्षाम्लम् । Garcinia indica (Thouars) Choisy 1824 -

Mangostane - Mangosteen

[Bildquelle: Subray Hegde / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

"GARCINIA INDICA, Chois.

Fig.—Bent, and Trim., t. 32; Wight Ill. I, 125, Red Mango (Eng.), Garcinia a fruit acide (Fr.).

Hab.—Western Peninsula, Amboyna.

The fruit, seeds, and bark.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—The tree is common on the Western coast between Damaun and Goa ; it grows wild upon the hills of the Concan, but is often to be seen in gardens close to the sea. It flowers about Christmas, and ripens its fruit in April and May. The fruit is largely used all along the Western coast as an acid ingredient in curries, and is an article of commerce in the dry state. It is generally prepared by removing the seeds and drying the pulp in the sun: the latter is then slightly salted and is ready for the market. It is known as Amsul or Kokam, and was in use in the Bombay Army as an antiscorbutic in 1799. (Dr. White. ) In Goa the pulp is sometimes made into large globular or elongated masses. The seeds are pounded and boiled to extract the oil, which, on cooling, becomes gradually solid and is roughly moulded by hand into egg-shaped balls or concave-convex cakes. This is the substance known to Europeans as Kokam butter. The natives occasionally use it for cooking, but it is mostly valued on account of its soothing properties when used medicinally. The juice of the fruit is sometimes used as a mordant in dyeing, and the apothecaries of Goa prepare a very fine red syrup from it, which is used in bilious affections. Nothing seems to be known of the history of the Kokam fruit before the time of Garcia d'Orta (1568), who found it in use at Goa, under the name of Brindao (A corruption of the Marathi name भिरंड Bhirand), when he visited that city; the same name is still used by the native Christians. As it was an article of export in Garcia's time, there can be little doubt that it was used in Western India long before the Portuguese visited the country, just in the same manner as it is at the present day. The tree was known to Rumphius, who calls it Folium acidum majus or Groot Saurblad. He says the young leaves are acid like sorrel, and are used in cooking fish in Amboyna. Kokam butter appears to have first attracted the notice of Europeans about 1880 as a remedy for excoriations and chaps of the skin; in order to apply it, a piece is partially melted and rubbed upon the affected part. It is also of great value for the preparation of Nitrate of Mercury ointment, which if made in the usual manner is too fluid for hot climates ; Indian lard being very fluid, equal parts of it and Kokam oil will be found to make an ointment of good consistence and colour which keeps well. The bark is astringent, and the young leaves after having been tied up in a plantain leaf and stewed in hot ashes, are rubbed in cold milk and given as a remedy for dysentery."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 163ff.]

Piperaceae - Pfeffergewächse

| 35c./d. tintiḍīkaṃ ca cukraṃ ca vṛkṣāmlam atha vellajam 36a./b. marīcaṃ kolakaṃ kṛṣṇam ūṣaṇaṃ dharmapattanam [Bezeichnungen für Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper:] तिन्तिडीकं च चुक्रं च वृक्षाम्लम् अथ

वेल्लजम् ।३५ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper bzw. Piper cubeba L. f. 1782 - Kubebenpfeffer - Tailed Pepper:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Pepper."

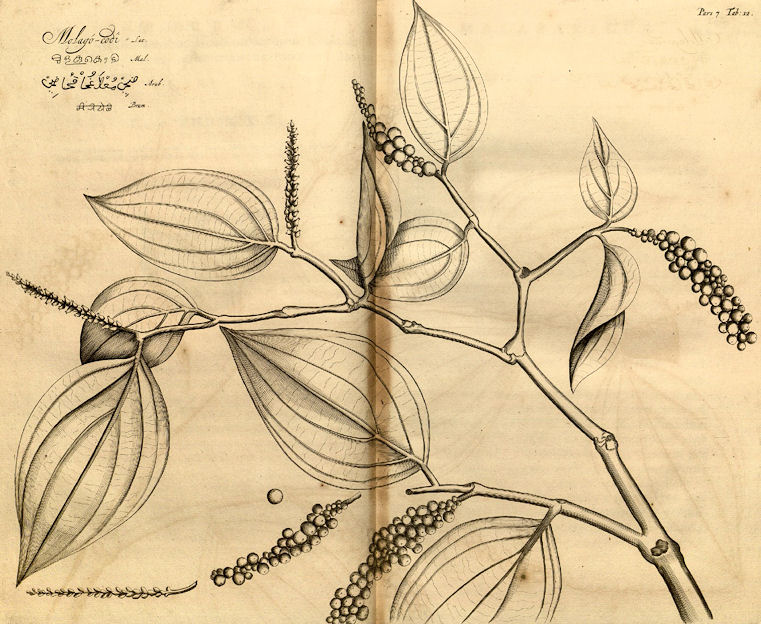

वेल्लज - vellaja n.: "aus einer Woge geboren" (wohl für valli-ja: "von einer Ranke entstanden"), Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper

Abb.: वेल्लजम् । Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper

[Bildquelle: Hortus malabaricus VII. Fig. 12,

1686]

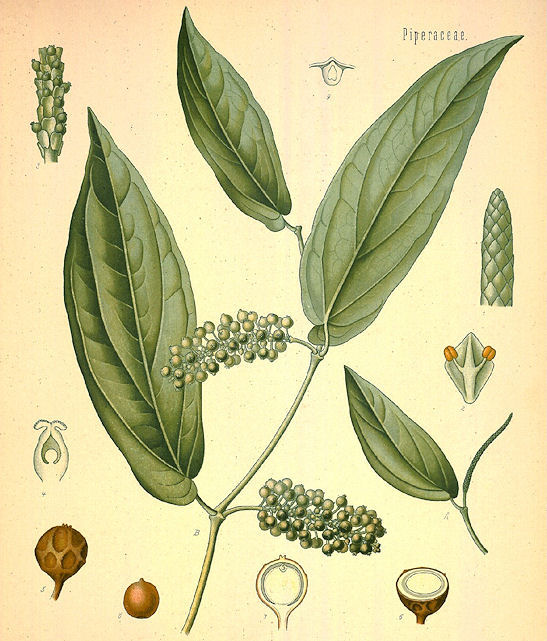

मरीच - marīca n.: "Lichtstrahl", Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper

Abb.: मरीचम् । Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper

[Bildquelle: Curtis's Botanical Magazine, v. 59 (1832), Tab. 3139]

कृष्ण - kṛṣṇa n.: Schwarzes, Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper

Abb.: कृष्णम् । Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper

[Bildquelle: Rainer Zenz / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

ऊषण - ūṣaṇa n.: Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper

Abb.: ऊषणम् । Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper,

Kerala

[Bildquelle: Aruna / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

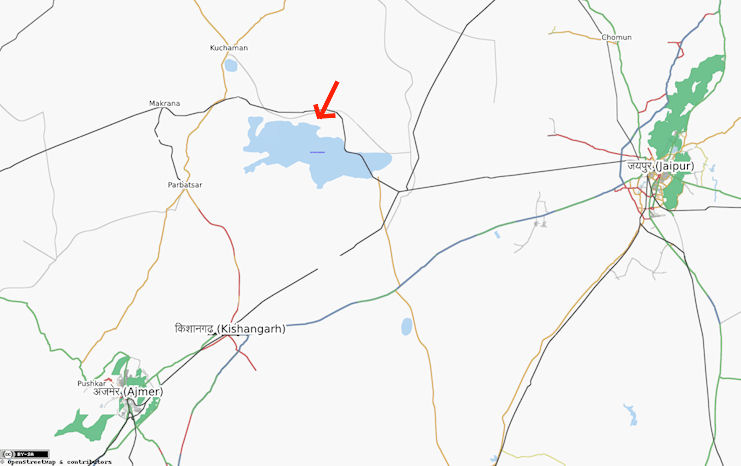

धर्मपत्तन - dharmapattana n.: "Stadt der buddhistischen Lehre" (= Śrāvastī) ; Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer - Black Pepper

Abb.: धर्मपत्तनम् ।

Lage von Śrāvasti

[Bildquelle: JIJITH NR / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: धर्मपत्तनम् ।

Teeplantage mit Pfeffer (Piper nigrum L. 1753 - Echter Pfeffer -

Black Pepper) auf die Bäume rankend, Cardamom Hills - കാര്ടമോം ഹില്ല്സ്,

Kerala

[Bildquelle: mutaminx. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mutaminx/3219984319/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

"Piper nigrum (Linn.) N. O. Piperaceae. Black-pepper vine

Description.—Stem shrubby, climbing, rooting, round; [...9

Wight Icon. 1934.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. I, 150.—Rheede, VII, t. 12.

Malabar forests. N. Circars.

Medical Uses.—Pepper contains an acrid soft resin, volatile oil, piperin, gum, bassorine, malic and tartaric acids, &c. ; the odour being probably due to the volatile oil, and the pungent taste to the resin. The berries medicinally used are given as stimulant and stomachic, and when toasted have been employed successfully in stopping vomiting in cases of cholera. The root is used as a tonic, stimulant, and cordial. A liniment is also prepared with them of use in chronic rheumatism. The watery infusion has been of use as a gargle in relaxation of the uvula. As a seasoner of food, pepper is well known for its excellent stomachic qualities. An infusion of the seeds is given as an antidote to arsenic, and the juice of the leaves boiled in oil externally in scabies. Pepper in over-doses acts as a poison, by over-exerting the inflammation of the stomach, and its acting powerfully on the nervous system. It is known to be a poison to hogs. The distilled oil has very little acrimony. A tincture made in rectified spirit is extremely hot and fiery. Pepper has been successfully used in vertigo, and paralytic and arthritic disorders.—Lindley. Ainslie.

Economic Uses.—The black-pepper vine is indigenous to the forests of Malabar and Travancore. For centuries pepper has been an article of exportation to European countries from the western coast of India. It was an article of the greatest luxury to the Romans during the Empire, and is frequently alluded to by historians. Pliny states its price in the Roman market as being 4s. 9d. a-lb. in English money. Persius gives it the epithet sacrum, as it were a thing to set a store by, so much was it esteemed. Even in later ages, so valuable an article of commerce was it considered, that when Attila was besieging Rome in the fifth century, he particularly named among other things in the ransom for the city about 3000 lb. of pepper. Although a product of many countries in the East, that which comes from Malabar is acknowledged to be the best.

Its cultivation is very simple, and is effected by cuttings or suckers put down before the commencement of the rains in June. The soil should be rich, but if too much moisture be allowed to accumulate near the roots, the young plants are apt to rot. In three years the vine begins to bear. They are planted chiefly in hilly districts, but thrive well enough in the low country in the moist climate of Malabar. They are usually planted at the base of trees which have rough or prickly bark, such as the jack, the erythrina, cashewnut, mango-tree, and others of similar description. They will climb about 20 or 30 feet, but are purposely kept lower than that. During their growth it is requisite to remove all suckers, and the vine should be pruned, thinned, and kept clean of weeds. After the berries have been gathered they are dried on mats in the sun, turning from red to black. They must be plucked before they are quite ripe, and if too early they will spoil. White-pepper is the same fruit freed from its outer skin, the ripe berries being macerated in water for the purpose. In this latter state they are smaller, of greyish-white colour, and have a less aromatic or pungent taste. The pepper-vine is very common in the hilly districts of Travancore, especially in the Cottayam, Meenachel, and Chenganacherry districts, where at an average calculation about 5000 candies are produced annually. It is one of the Sircar monopolies.

The greatest quantity of pepper comes from Sumatra. The duty on pepper in England is 6d. per lb., the wholesale price being 4d. per lb. White-pepper varies from ninepence to one shilling per lb. It may not be irrelevant here to notice the P. trioicum (Roxb.) which both Dr Wight and Miquel consider to be the original type of the P. nigrum, and from which it is scarcely distinct as a species. The question will be set at rest by future botanists. The species in question was first discovered by Dr. Roxburgh growing wild in the hills north of Samulcottah, where it is called in Teloogoo the Murial-tiga. It was growing plentifully about every valley among the hills, delighting in a moist rich soil, and well shaded by trees; the flowers appearing in September and October, and the berries ripening in March. Dr. R. commenced a large plantation, and in 1789 it contained about 40,000 or 50,000 pepper-vines, occupying about 50 acres of land. The produce was great, about 1000 vines yielding from 500 to 1000 lb. of berries. He discovered that the pepper of the female vines did not ripen properly, but dropped while green, and that when dried it had not the pungency of the common pepper; whereas the pepper of those plants which had the hermaphrodite and female flowers mixed on the same ament was exceedingly pungent, and was reckoned by the merchants equal to the best Malabar pepper.—Roxb. Simmonds. Wight Ainslie."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

PIPER NIGRUM, Linn. Fig.—Miq. Ill. Pip. 50, t. 50; Bot. Mag., t. 3139; Bentl. and. Trim., t. 245;

Black Pepper

Hab.—Travancore and Malabar. Cultivated elsewhere. The fruit.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—The earliest travellers from the West who visited India, found the pepper vine in cultivation on the Malabar Coast. Theophrastus (H. P. ix., 22) mentions two kinds of pepper (πιπερι or πεπερι) in the fourth century B. C., and Dioscorides (ii., 148) mentions λεθκον πεπερι, white pepper, μακρον πεπερι, long pepper, and μελαν πεπερι, black pepper. Pliny says:— "It is quite surprising that the use of pepper has come so much into fashion, seeing that in other substances which we use, it is sometimes their sweetness, and sometimes their appearance, that has attracted our notice; whereas, pepper has nothing in it that can plead as a recommendation to either fruit or berry, its only desirable quality being a certain pungency; and yet it is for this that we import it all the way from India! Who was the first to make trial of it as an article of food ? and who, I wonder, was the man that was not content to prepare himself, by hunger only, for the satisfying of a greedy appetite ?'' (12, 14.)

In the Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, written about A.D. 64, it is stated that pepper is exported from Baraké, the shipping place of Nelkunda. in which region, and there only, it grows in great quantity. These have been identified with places on the Malabar Coast between Mangalore and Calicut.

Long pepper and Black pepper are among the Indian spices on which the Romans levied duty at Alexandria about A.D.176.

Cosmas Indicopleustes, a merchant, and in later life a monk, who wrote about A.D. 540, appears to have visited the Malabar Coast, or at all events had some information about the pepper-plant from an eye-witness. It is he who furnishes the first particulars about it, stating that it is a climbing plant, sticking close to high trees like a vine. Its native country he calls Male. The Arabian authors of the Middle Ages, as Ibn Khurdadbah (circa A.D. 869-885), Edrisi in the middle of the 12th, and Ibn Batuta in the 14th century, furnished nearly similar accounts.

Among Europeans who described the pepper-plant with some exactness, one of the first was Benjamin of Tudela, who visited the Malabar Coast in A.D. 1166. Another was the Catalan friar, Jordanus, about 1330 ; he described the plant as something like ivy, climbing trees and forming fruit, like that of the wild vine. "This fruit," he says, "is at first green, then, when it comes to maturity, black." Nearly the same statements are repeated by Nicolo Conti, a Venetian, who, at the beginning of the 15th century, spent twenty-five years in the East. He observed the plant in Sumatra, and also described it as resembling ivy. (Pharmacographia.)

The high cost of pepper contributed to incite the Portuguese to seek for a sea passage to India, and the trade in this spice continued to be a monopoly of the Crown of Portugal as late as the 18th century.

In January 1793, an agreement was made between the Rajah of Travancore and the English, by which he was to supply a large quantity of pepper to the Bombay Government in return for arms, ammunition and European goods; this was known as the "Pepper Contract."

It is worthy of remark that all the foreign names for black pepper are derived from Pippali, the Sanskrit name for long pepper, which leads one to suppose that the latter spice was the first kind of pepper known to the ancient Persians and Arabs, through whose hands it first reached Europe. Their earlier writers describe the plant as a shrub like the Pomegranate (P. chaba ?). The moderns apply the name Filfil (Pilpil, Pers.) to all kinds of pepper. Black pepper is called in Sanskrit Maricha, which means a "pungent berry." The word is derived from Marichi, "a particle of light or fire," and appears to have been first applied to the aromatic berries known as Kakkola; it now signifies black and red pepper, and in the vernacular forms of Mirach or Mirchai, is a household word in India.

Maricha is described in the Nighantas as bitter, pungent, digestive, hot and dry; synonyms for it are Valli-ja "creeper grown," Ushana, Tikshna "pungent,'' Malina, Syama "black," &c. It is said to be useful in intermittent fever, haemorrhoids, dyspepsia, cough, gonorrhoea and flatulence, and to promote the secretion of bile. Together with long pepper and ginger it forms the much-used compound known as Trikatu, "the three acrids," or " Ushana-chatu-rushana." Externally, pepper is used as a rubefacient and stimulant of the skin. In obstinate intermittent fever and flatulent dyspepsia, the Hindus administer white or black pepper in the following manner:—A tablespoon-ful is boiled overnight in one seer of' water, until the water is reduced to one-fourth of its bulk, the decoction is allowed to cool during the night, and is taken in the morning. The pepper is then again boiled in the same manner and the decoction taken at night. This treatment is continued for seven successive days. A compound confection of pepper (Pranada gudikd) is given as a remedy for piles ; it is made in the following manner :—Take of black pepper 32 tolas, ginger 24 tolas, long pepper 16 tolas, Piper chaba (chavya) 8 tolas, leaves of Taxus baccata (tālisa) 8 tolas, flowers of Mesua ferrea (nāgkesar) 4 tolas, long pepper root 16 tolas, cinnamon leaves and cinnamon one tola each, cardamoms and the root of Andropogon muricatum (usira) 2 tolas each, old treacle 240 tolas; rub them together. Dose about 2 drachms. When there is costiveness, chebulic myrobalans are substituted for ginger in the above prescription. (Chakradatta.)

The use of pepper for the cure of intermittents is strongly recommended by Stephanus in his commentary on Galen, and recently some cases of refractory intermittent fever, in which, after the failure of quinine, piperine has been administered with advantage, are reported by Dr. C. S. Taylor (Brit. Med. Journ., Sept., 1886). In one case, immediately on the accession of an attack, three grains of piperine were given every hour, until eighteen grains had been taken, and on the following day, when the intermission was complete, the same dose was given every three hours.

Mahometan physicians describe black pepper as deobstruent, resolvent, and alexipharmic; as a nervine tonic it is given internally, and applied externally in paralytic affections; in toothache it is used as a mouth-wash. As a tonic and digestive, it is given in dyspepsia. With vinegar it forms a good stimulating poultice. With honey it is useful in coughs and colds. Moreover, it is diuretic and emmenagogue, and a good stimulant in cases of bites by venomous reptiles. Strong friction with pepper, onions, and salt is said to make the hair grow again upon the bald patches left by ringworm of the scalp. They notice the use of the unripe fruit, preserved in salt and water as a pickle, by the natives of Malabar.

De Gubernatis draws attention to the following passage from the travels of Vincenzo Maria da Santa Caterina (iv., 3) with reference to white pepper being offered by the Hindus to their gods in Malabar:—"Da Malavari è tenuto in stima grandissima, eli Gentili d'ordinario l'offrono a loro Dei, si per la rarità come per la virtù salutifera e medicinale, che da quello sperimentano, riportandolo poi alli infermi." For the early history of pepper in Europe, the Pharmacographia may be consulted.

Cultivation.—Its cultivation is very simple, and is effected by cuttings or suckers put down before the commencement of the rains in June. The soil should be rich, but if too much moisture be allowed to accumulate near the roots, the young plants are apt to rot. In three years the vine begins to bear. They are planted chiefly in hilly districts, but thrive well enough in the low country in the moist climate of Malabar. They are usually planted at the base of trees which have rough or prickly bark, such as the jack, the erythrina, cashewnut, mango-tree, and others of similar description. They will climb about 20 or 30 feet, but are purposely kept lower than that. During their growth it is requisite to remove all suckers, and the vine should be pruned, thinned, and kept clean of weeds. After the berries have been gathered, they are dried on mats in the sun, turning from red to black. They must be plucked before they are quite ripe, and if too early they will spoil. White pepper is the same fruit freed from its outer skin, the ripe berries being macerated in water for the purpose. In this latter state they are smaller, of greyish-white colour, and have a less aromatic or pungent taste. The pepper-vine is very common in the hilly districts of Travancore, especially in the Cottayam, Meenachel, and Chenganacherry districts, where, at an average calculation, about 5,000 candies are produced annually. It is a Government monopoly. (Drury.)"

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 166 - 171.]

कोलक - kolaka n.: Piper cubeba L. f. 1782 - Kubebenpfeffer - Tailed Pepper

Abb.: कोलकम् । Piper cubeba L. f. 1782 - Kubeben-Pfeffer - Tailed

Pepper

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883]

Abb.: कोलकम् । Piper cubeba L. f. 1782 - Kubeben-Pfeffer - Tailed

Pepper

[Bildquelle: Miansari66 / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

"PIPER CUBEBA, Linn. f. Fig — Bentl. and Trim., t. 243.

Cubebs

Hab.—Java.

[...]

History, Uses, &C.—Cubebs were introduced into medicine by the Arabian physicians of the Middle Ages. Masudi in the 10th century stated them to be a production of Java. The author of the Sihah, who died in 1006, describes Kababeh as a certain medicine of China. Ibn Sina, about the same time, notices it as having the properties of madder, but a more agreeable taste, and states that it is said to possess hot and cold properties, but is really hot and dry in the third degree, a good deobstruent, and useful as an application to putrid sores and pustules in the mouth ; it is also good for the voice and for hepatic obstructions ; a valuable diuretic, expelling gravel and stone from the kidneys and bladder. He concludes by stating that the application of the saliva, after chewing it, increases the sexual orgasm. Later Mahometan writers have similar accounts of Kababeh, and say that it is called Hab-el-arus, "bridegroom's berry," and that Greek names for it are Mahilyun and Karfiyun, evidently a corruption of καρπεσιον, the name of an aromatic wood mentioned by Paulus Aegineta. It appears that cubebs were at one time known as Fructus carpesiorum in Europe. In the Raja Nirghanta, which was written about 600 years ago, cubebs appear under the name of Kankola, and the same name appears in the Hindi and Marathi Nighantas. Madanpal gives Katuka-kola, "pungent pepper," as a synonym for it. All the Sanskrit names appear to be of comparatively recent origin. The authors of the Pharmacographia draw attention to the fact that the action of cubebs upon the urino-genital organs, though known to the old Arabian physicians, was unknown to modern European writers on Materia Medica at the commencement of the present century. According to Crawfurd, its importation into Europe, which had long been discontinued, recommenced in 1815, in consequence of its medicinal virtues having been brought to the knowledge of the English medical officers serving in Java, by their Hindu servants. (Op. cit., 2nd Ed., p. 585.) In earlier times cubeb pepper was used in Europe as a spice, as it still is, to some extent, in the East."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 180f.]

Apiaceae - Doldenblütler

| 36c./d. jīrako jaraṇo 'jājī kaṇāḥ kṛṣṇe tu jīrake जीरको जरणो ऽजाजी कणाः कृष्णे तु जीरके ।३६ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Cuminum cyminum L. 1753 - Kreuzkümmel - Cumin:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Cumin."

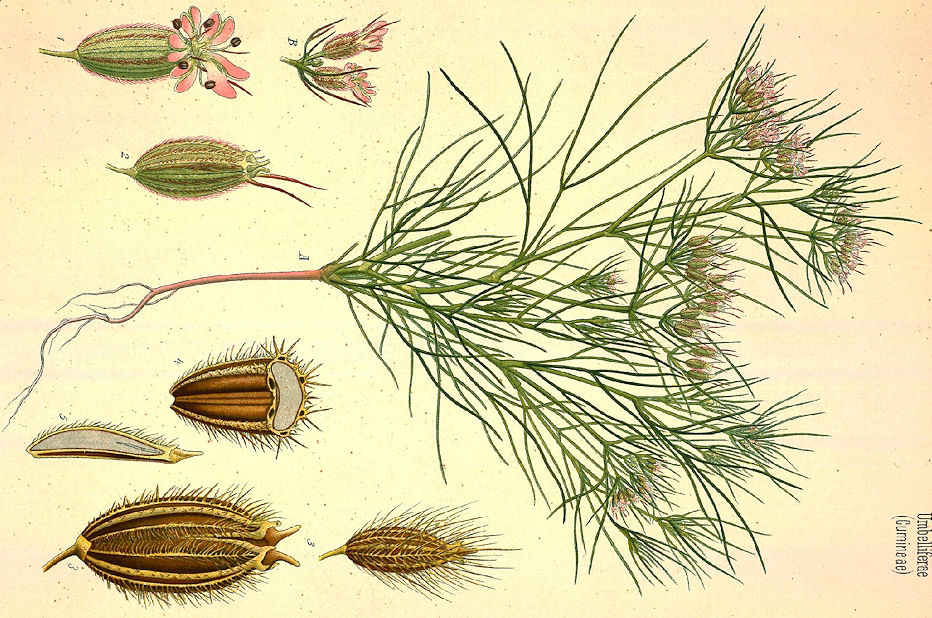

जीरक - jīraṇa m.: verdauend, Cuminum cyminum L. 1753 - Kreuzkümmel - Cumin

Abb.: जीरणः । Cuminum cyminum L. 1753 - Kreuzkümmel - Cumin

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883-1914]

जरण - jaraṇa m.: verdauend, Cuminum cyminum L. 1753 - Kreuzkümmel - Cumin

Abb.: जरणः । Cuminum cyminum L. 1753 - Kreuzkümmel - Cumin

[Bildquelle: Sanjay Acharya / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

अजाजी - ajājī f.: "Ziegen herantreibend", Cuminum cyminum L. 1753 - Kreuzkümmel - Cumin

Abb.: अजाजी । Namkeen Chach (नमकीन) mit Kümmel und anderen Gewürzen, Delhi

[Bildquelle: Scott Dexter. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ampersandyslexia/3245069577/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

कणा - kaṇā f.: Cuminum cyminum L. 1753 - Kreuzkümmel - Cumin

Abb.: कणाः । Cuminum cyminum L. 1753 - Kreuzkümmel - Cumin

[Bildquelle: Henna / Wikimedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"Cuminum Cyminum (Linn.) N. O. Umbelliferae. Cummin

Description.—Herbaceous; [...] flowers white.

W. & A. Prod, i. 373.—Dec. Prod. iv. 201.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. ii. 92.

Cultivated

Medical Uses.—The seeds are met with in the bazaars throughout India, being much in use as a condiment. Their warm bitterish taste and aromatic odour reside in a volatile oil. Both seeds and oil possess carminative properties analogous to Coriander and Dill, and on this account are much valued by the natives.—Pharm of India."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"CUMINUM CYMINUM, Linn. Fig.—Bentl. and Trim., t. 134.

Cumin (Eng., Fr.).

Hab.—Africa. Cultivated in India. The fruit.

[...9

History, Uses, &e.—The use of cumin as a spice and medicine is of the highest antiquity, and appears to have spread from the cradle of civilization in Egypt to Arabia, Persia, India and China. Cumin is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, it is the

κυμινον of the Greeks, and Theophrastus (H. P. IX.) tells us that it was the custom to utter curses when sowing it (probably to avert the evil eye). Dioscorides (iii., 61,) calls it κυμινον ημερον, and notices its medicinal properties; in the same chapter he mentions another kind of cumin, "the king's cumin of Hippocrates," which the Arabians identify with ajowan, and in the next chapter two kinds of wild cumin. Popular allusions to cumin are common in the writings of the Greeks and Romans, cumin and salt was a symbol of friendship (Plut. Symp. 5, 10, 1). Pliny tells us that students eat it to make themselves look pale and interesting. Greek writers mention a κυμινο-δοκον or cumin-box which was placed on the table like a salt-cellar. Flückiger and Hanbury trace its use during the Middle Ages, when it appears to have been much valued in Europe. Mannhardt (Baumkultus der Germanen) says that bread was spiced with cumin to protect it from the demons, and De Gubernatis (Myth. des Plant.) states that it is used for the same purpose in Italy, and on account of its supposed retentive powers is given to domestic animals to keep them from straying, and by girls to their sweethearts for the same reason.Jira and Jirana, the Sanskrit names for cumin, as well as the Persian Zhireh or Zireh, and all the Indian vernacular names appear to be derived from the root Jri, and to allude to the digestive properties of the seeds; other Sanskrit names are Ajāji " that overcomes goats, "ajamoda "goat's delight" and Kunchicka. The Arabic name Kamūn is doubtless derived from the Greek. Ibn Sina and the Eastern Arabs, and also the Persians follow Dioscorides in describing four kinds of cumin, which they name Kirmāni or black, Farsi or yellow, Shāmī (Syrian) and Nabti (Egyptian). They also mention along with them Karawya or caraway as a seed like anise. In the absence of accurate descriptions it is impossible to say what these four kinds were, but it seems probable that the Kirmāni or black cumin is correctly identified by the Indian Mahometans with the seeds known in India as Siyah-Jira, a species of caraway peculiar to Central Asia. The Nabti or Egyptian kind is probably true cumin.

Cumin is much used as a condiment in India, and is an essential ingredient in all the mixed spices and curry powders of the natives. Medicinally they regard it as stomachic, carminative and astringent, and prescribe it in chronic diarrhoea and dyspepsia. A medicinal oil is expressed from the seeds. Cumin is applied in the form of a plaster to allay pain and irritation. It is thought to be very cooling, and on this account it is an ingredient in moat antaphrodisiac prescriptions, and is administered in gonorrhoea."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 113ff.]

Ranunculaceae - Hahnenfußgewächse

| 36c./d. jīrako jaraṇo 'jājī kaṇāḥ kṛṣṇe tu jīrake 37a./b. suṣavī kāravī pṛthvī pṛthuḥ kālopakuñcikā

जीरको जरणो

ऽजाजी कणाः कृष्णे तु जीरके

।३६ ख। Der Schwarze Kümmel (jīraka m.) heißt:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Kalonjī. Nigella Indica, Roxb."

सुषवी - suṣavī f.: Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

Abb.: सुषवी । Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883-1914]

कारवी - karavī f.: "Krähin", Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

Abb.: कारवी । Früchte von Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel -

Black Cumin

[Bildquelle: badthings. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/badthings/529989544/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

पृथ्वी - pṛthvī f.: weit, Erde, Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

Abb.: पृथ्वी । Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

पृथु - pṛthu f.: weit, Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

Abb.: पृथुः । Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin,

Wien, Österreich

[Bildquelle: AndreHolz / Wikipedia. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

काला - kālā f.: schwarz, Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

Abb.: कालाः । Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

[Bildquelle: TheGoblin / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

उपकुञ्चिका - upakuñcikā f.: "sich darauf krümmend", Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black Cumin

Abb.: उपकुञ्चिका । Nigella sativa L. 1753 - Schwarzkümmel - Black

Cumin, Deutschland

[Bildquelle: ༺Stadtkatze༻. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/stadtkatze/3842787530/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

"NIGELLA SATIVA, Sibthorp. Fig.—Zorn. Ic. 119.

Small Fennel-flower

Hab .—The Mediterranean countries. Cultivated in India.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—According to Birdwood, it is the Black Cummin of the Bible, the Melanthion of Hippocrates and Dioscorides, and the Gith of Pliny. Ainslie mentions its' use as a carminative, also as an external application mixed with sesamum oil in skin eruptions, as a seasoning for food, and as a protection for linen against insects. Forskahl, in his Medicine Kaharina, says that it is a native of Egypt, where it is called Hab-es-souda. Roxburgh believes it to be a native of Hindostan. Anyhow, it must have been long known in India, as it has a Sanskrit name, Krishnajiraka. Nigella seed is extensively used as a spice, and as a medicine; it is prescribed by the Hindus with other aromatics and plumbago root in dyspepsia. The Hakeems describe it as heating, attenuant, suppurative, detergent and diuretic, and consider that it increases the menstrual flow and the secretion of milk ; also that it stimulates uterine action. They give it, too, as a stimulant in a variety of disorders which are ascribed to cold humours, and credit it with anthelmintic properties. It is sprinkled over the surface of the bread made by Mahometan bakers along with Sesamum seed. (See Cuminum Cyminum.) M. Canolle has recently published (De I'avortement criminel a Karikal. Thèse de Paris, 1881,) the results of clinical investigations undertaken in the hospital at Karikal with black cummin seed. He has observed that after doses of 10 to 40 grams of the powdered seed the temperature of the body is raised, the pulse accelerated, and all the secretions stimulated, especially those of the kidneys and skin; in doses of 10 to 20 grams, they possess a well marked emmenagogue action in dysmenorrhea, and in larger doses cause abortion."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 1. -- London, 1890. -- S. 28f.]

Zingiberaceae - Ingwergewächse

| 37c./d. ārdrakaṃ śṛṅgaveraṃ syād atha chatrā vitunnakam आर्द्रकं शृङ्गवेरं स्याद् अथ छत्रा वितुन्नकम् ।३७ ख। [Bezeichnungen für frischen Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Ginger."

आर्द्रक - ārdraka n.: frisch, feucht, frischer Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger

Abb.: आर्द्रकम् । Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher

Ingwer - Ginger

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883-1914]

शृङ्गवेर - śṛṅgavera n.: "mit einem Horn als Körper", frischer Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger

Abb.: शृङ्गवेरम् । Frisches Rhizom von Zingiber officinale Roscoe

1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger

[Bildquelle: Maja Dumat. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/blumenbiene/4801304738/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-11. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

"Zingiber officinale (Roscoe.) N. O. Zingiberaceae. Common Ginger, Eng. Ingie, Tam. Inchi, Mal. Ullum, Tel. Sonth, Hind. Udruck, Ada, Beng.

Description.—Rhizome tuberous, biennial; stems erect and oblique, invested by the smooth sheaths of the leaves, generally 3 or 4 feet high, and annual; leaves sub-sessile on their long sheaths, bifarious, linear-lanceolate, very smooth above and nearly so underneath; sheaths smooth, crowned with a bifid ligula; scapes radical, solitary, a little removed from the stems, 6-12 inches high, enveloped in a few obtuse sheaths, the uppermost of which sometimes end in tolerably long leaves; spikes oblong, the size of a man's thumb; exterior bracts imbricated, 1-flowered, obovate, smooth, membranous at the edge, faintly striated lengthwise; interior enveloping the ovary, calyx, and the greater part of the tube of the corolla; flowers small; calyx tubular opening on one side, 3-toothed; corolla with a double limb; outer of 3, nearly equal, oblong segments, inner a 8-lobed lip, of a dark-purple colour; ovary oval, 3-celled, with many ovules in each; style filiform. Fl. Aug.—Oct.—Roxb. Fl. Ind. i. 47.—

Amomum Zingiber, Linn.—Rheede, xi. t. 12.------Cultivated over all the warmer parts of Asia.

Medical Uses.—The Ginger plant is extensively cultivated in India from the Himalaya to Cape Comorin. In the former mountains it is successfully reared at elevations of 4000 or 6000 feet, requiring a moist soil. The seeds are seldom perfected, on account of the great increase of the roots. These roots or rhizomes have a pleasant aromatic odour. When old they are scalded, scraped, and dried, and are then the white ginger of the shops; if scalded without being scraped, the black ginger. It is not exactly known to what country the ginger plant is indigenous, though Ainslie states it to be a native of China, while Joebel asserts that it is a native of Guinea.

It is still considered doubtful whether the black and white ginger are not produced by different varieties of the plant. Rumphius asserts positively that there are two distinct plants, the white and the red ; and Dr Wright has stated in the London Medical Journal, that two. sorts—namely, the white and black—are Cultivated in Jamaica. The following account of its cultivation is given in Simmond's Commercial Products: The Malabar ginger exported from Calicut is the produce of the district of Shernaad, situated to the south of Calicut; a place chiefly inhabited by Moplas, who look upon the ginger cultivation as a most valuable and profitable trade, which in fact it is. The soil of Shernaad is so very luxuriant, and so well suited for the cultivation of ginger, that it is reckoned the best, and in fact the only place in Malabar where ginger grows and thrives to perfection. Gravelly grounds are considered unfit; the same may be said of swampy ones ; and whilst the former check the growth of the ginger, the latter tend in a great measure to rot the root. Thus the only suitable kind of soil- is that which, being red earth, is yet free from gravel, and the soil good and heavy. The cultivation generally commences about the middle of May, after the ground has undergone a thorough process of ploughing and harrowing.

At the commencement of the monsoon, beds of 10 or 12 feet long by 3 or 4 feet wide are formed, and in these beds small holes are dug at 3/4 to 1 foot apart, which are filled with manure. The roots, hitherto carefully buried under sheds, are dug out, the good ones picked from those which are affected by the moisture, or any other concomitant of a half-year's exclusion from the atmosphere, and the process of clipping them into suitable sizes for planting performed by cutting the ginger into pieces of 1 1/2 to 2 inches long. These are then buried in the holes, which have been previously manured, and the whole of the beds are then covered with a good thick layer of green leaves, which whilst they serve as manure, also contribute to Keep the beds from unnecessary dampness, which might otherwise be occasioned by the heavy falls of rain during the months of June and July. Rain is essentially requisite for the growth of the ginger; it is also, however, necessary that the beds be constantly kept from inundation, which, if not carefully attended to, the crop is entirely ruined; great precaution is therefore taken in forming drains between, the beds, letting water out, thus preventing a superfluity. On account of the great tendency some kinds of leaves have to breed worms and insects, strict care is observed in the choosing of them, and none But the particular kinds used in manuring ginger are taken in, lest the wrong ones might fetch in worms, which, if once in the beds, no remedy can be resorted to successfully to destroy them; thus they in a very short time ruin the crop. Worms bred from the leaves laid on the soil, though highly destructive, are not So pernicious to ginger cultivation as those which proceed from the effect of the soil. The former kind, whilst they destroy the beds in which they once appear, do not spread themselves to the other beds, be they ever so close; but the latter kind must of course be found in almost all the beds, as they do not proceed from accidental causes, but from the nature of the soil. In cases like these, the whole crop is oftentimes ruined, and the cultivators are thereby subjected to heavy losses.

The rhizomes when first dug up are red internally, and when procured fresh and young are preserved in sugar, constituting the preserved ginger of the shops. Essence of ginger is made by steeping ginger in alcohol. With regard to its medical uses, ginger, from its stimulant and carminative properties, is used in toothaches, gout, rheumatism of the jaws, and relaxed uvula, with good effect, and the essence of ginger is said to promote digestion. Ginger is said to act powerfully on the mucous membrane, though its effects are not always so decided on the remoter organs as on those which it comes into immediate contact with. Beneficial results hove been arrived at when it has been administered in pulmonary and catarrhal affections. Headaches have also been frequently relieved by the application of ginger - poultices to the forehead. The native doctors recommend it in a variety of ways externally in paralysis and rheumatism, and internally with other ingredients in intermittent fevers. Dry or white ginger is called Sookhoo in Tamil, and South in Dukhanie ; and the green ginger is Injee in Tamil, and Udruck in Dukhanie. The ginger from Malabar is reckoned superior to any other.—Ainslie, Simmonds."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

"ZINGIBER OFFICINALE, Rosc. Fig.—Bentl. and Trim., t. 270; Rosc. Monand. Pl., 83 ; Woodville, t. 250; Steph. and Ch., t. 96.

Hab.— Cultivated throughout the East.

The rhizome.

[...]

History, Uses, &c.—Ginger has been cultivated in India from prehistoric times ; it is a native of the East, but is not now known in a wild state. In Sanskrit it bears many names, such as Mahaushadha " great remedy," Visva "pervader," Visva-bheshaja "panacea," Sringavera "antlered," Katu badra "the good acrid," &c. When dried it is known as Sunthi and Nagara in distinction from Ardraka "fresh ginger." In the Nighantas it is described as acrid and digestive, useful for the removal of cold humors, costiveness, nausea, asthma, cough, colic, palpitation of the heart, tympanitis, swellings, piles, &c. Ginger is one of the three acrids (trikatu) of the Hindu physicians, the other two being black pepper and long pepper; combined with other spices and sugar, as in the preparations known as Samasarkara churna and Saubhagya sunthi, it is given in dyspepsia and loss of appetite. In rheumatism preparations of ginger and other spices with butter are given internally, and it is an ingredient in oils used for external application. The juice of the fresh tubers, with or without the juice of garlic, mixed with honey, is a favourite domestic remedy for cough and asthma, with lime juice it is used in bilious dyspepsia, and a paste of dry ginger and warm water is applied to the forehead to relieve headache. In Western India, ginger juice, with a little honey and a pinch of burnt peacock's feathers, is the popular remedy for vomiting. In old Persian we find the names Shingabir or Shangabir and Adrak applied to ginger, and it was probably through the Persians that the Greeks first became acquainted with it, as their

ζιγγιβερι is evidently derived from the Sanskrit Sringavera through the Persian form of the word. The Arabic name Zanjabil is of similar origin, the chief difference being the substitution of the letter J for G, which is not in the Arabian alphabet.Ginger is described by Dioscorides as hot, digestive, gently laxative, stomachic and having all the properties of pepper; it was an ingredient in collyria and antidotes to poison. Pliny notices it in his chapter on peppers, but very briefly, and it does not appear to have been regarded as an article of much importance in his time.

In the second century of our era, ginger is mentioned as liable to duty (vectigal) at Alexandria along with other Indian spices. (Vincent Com. and Nav. of the Ancients, III, 695). Galen recommends it in paralysis and all complaints arising from cold humors ; Paulus in neuralgia and gout, Ibn Sina and other Arabian and Persian physicians closely follow the Greeks, but enlarge upon its aphrodisiacal properties. In modern medicine the value of ginger as a carminative in atonic dyspepsia and flatulent colic, and as a masticatory in relaxed conditions of the throat is generally admitted.

The manufacture of ginger beer and ginger ale forms a large portion of the mineral water trade in En gland ; indeed, some makers have acquired a special reputation for their production. Besides the large number of fermented and aerated ginger beers consumed at home, a good deal of ginger ale is shipped in glass bottles from Belfast, especially to the United States. About 16,000 packages or casks are so exported annually, for it has become a fashionable beverage in America among all classes.

[...]

The number of uses to which ginger is applied besides as a spice, confection and medicine are many ; for instance, we have gingerade, ginger ale, ginger beer, ginger brandy, ginger bread, ginger champagne, ginger cordial, ginger essence, ginger lozenges and ginger wine.

On the Continent of Europe, ginger is less used and appreciated than in England.

Soluble essences of ginger are required for making good ginger beer, and Belfast and American ginger ales. There are aerated and fermented ginger beers; the best unbleached Jamaica ginger, well bruised, being used for the latter. Ginger is also used for a kind of cordial and champagne.

Lastly, young ginger is candied and preserved to a considerable extent in the East, and comes into commerce under the section of "succades." The quantity imported into England from India and China ranges from 300,000 to 600,000 pounds, of the value of £11,000 to £25,000. The mode of preserving it is to steep the rhizomes in vats of water for several days, changing the water once. When taken out it is spread on tables and well pricked or pierced with bodkins. The rhizomes are then boiled in a copper caldron, then steeped for two days and nights in a vat with a mixture of water and rice flour. After this they are washed with a solution of lime, then boiled with an equal weight of sugar and a little white of egg is added to clarify.

After the ginger has been boiled a second time it is put in glazed jars of pottery, holding 1 pound, 3 pounds or 6 pounds, and covered with syrup. The syrup is changed two or three times, and then they are shipped in cases holding six jars.

The quality called "Mandarin" is put up in barrels. (P. L. Simmonds, Amer. Jn. Pharm. 1891.)"

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 420 - 423.]

Apiaceae - Doldenblütler

| 37c./d. ārdrakaṃ śṛṅgaberaṃ syād atha chatrā vitunnakam 38a./b. kustumburu ca dhānyākam atha śuṇṭhī mahauṣadham

आर्द्रकं शृङ्गबेरं स्याद् अथ छत्रा

वितुन्नकम् ।३७ ख। [Bezeichnungen für Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Coriander."

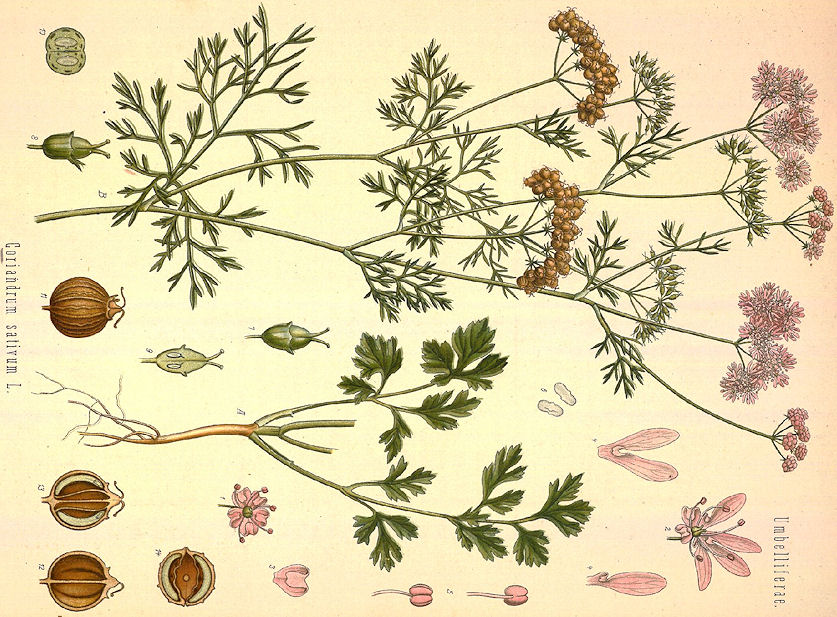

छत्रा - chatrā f.: Sonnenschirm, Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

Abb.: छत्रा । Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883-1914]

Abb.: छत्रा । Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander,

Deutschland

[Bildquelle: H. Zell / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

वितुन्नक - vitunnaka n.: zerstochen, zerstechend, Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

Abb.: वितुन्नकम् । Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

[Bildquelle: Sanjay Acharya / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: वितुन्नकम् । Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

[Bildquelle: Steve Hurst @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database. -- Public domain]

कुस्तुम्बुरु - kustumburu n.: Körner von Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

Abb.:

कुस्तुम्बुरूणि ।

Körner von Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

[Bildquelle: Ombrosoparacloucycle. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/30063276@N02/3410427890/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-12. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

धान्याक - dhānyaka n.: "Getreidchen", Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

Abb.: धान्यकम् । Coriandrum sativum L. 1753 - Koriander - Coriander

[Bildquelle: zzzeroX

Productions. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/0x/3054721148/. -- Zugriff am 2011-07-12.

--

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

share alike)]

"CORIANDRUM SATIVUM, Linn. Fig.—Bentl. and Trim., 1.133.

Coriander

Hab.—Cultivated in India. The fruit.

[...]

History, Uses, &C.-—The Coriander plant is called Kothmir, a name derived from the Sanskrit Kusthumbari; when young it is much used in preparing chutneys and sauces. The fruits are largely used by natives as a condiment; as a medicine they are considered carminative, diuretic, tonic, and aphrodisiac, and are often prescribed in dyspepsia. A cooling drink is prepared from them pounded with fennel fruit, poppy seeds, Kanchan flowers, rosebuds, cardamoms, cubebs, almonds and a little black pepper; it is sweetened with sugar. Mahometan writers describe them as sedative, pectoral and carminative; they prepare an eyewash from them which is supposed to prevent small-pox from destroying the eight, and to be useful in chronic conjunctivitis. Coriander is also thought to lessen the intoxicating effects of spirituous preparations, and with Barley meal to form a useful poultice for indolent swellings. It is the Kuzbura of the Arabs and Kishnīz of the Persians, who identify it with the Koriyun of the Greeks. The opinion that it has great cooling properties prevailed amongst Western physicians, "coriandrum siccum frangit coi tum, et erectionem virgae impedit." Apuleius says it assists women in child-birth and protects them from fever."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 129f.]

Zingiberaceae - Ingwergewächse

| 38a./b. kustumburu ca dhānyākam atha śuṇṭhī mahauṣadham 38c./d. strī-napuṃsakayor viśvaṃ nāgaraṃ viśvabheṣajam

कुस्तुम्बुरु च धान्याकम् अथ शुण्ठी महौषधम्

।३८ क। [Bezeichnungen für getrockneten Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Dry ginger."

Siehe oben zu Vers 37c./d.

शुण्ठी - śuṇṭhī f.: weiß, Getrockneter Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger

Abb.: Trocknen von Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher

Ingwer - Ginger, Kochi - കൊച്ചി,

Kerala

[Bildquelle: mutaminx. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mutaminx/3219988991/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-12. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

महौषध - mahauṣadha n., f.: große Arzneipflanze, Getrockneter Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger

Abb.: Trocknen von Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher

Ingwer - Ginger, Kochi - കൊച്ചി,

Kerala

[Bildquelle: choubb. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/choubb/5359778226/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-12. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

विश्व - viśva f., n.: alles, Getrockneter Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger

Abb.: विश्वम् । Getrockneter Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher

Ingwer - Ginger

[Bildquelle: Efraim Lev and Zohar Amar / Wellcome Images. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

नागर - nāgara n.: städtisch, Getrockneter Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger

Abb.: नागरम् । Instant-Ingwer, Thailand

[Bildquelle: A. Payer. -- Public domain]

विश्वभेषज - viśvabheṣaja n.: Allheilmittel, Getrockneter Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher Ingwer - Ginger

Abb.: विश्वभेषजम् । Getrockneter Zingiber officinale Roscoe 1807 - Gewöhnlicher

Ingwer - Ginger

[Bildquelle: A. Payer. -- Public domain]

| 39a./b. āranālaka-sauvīra-kulmāṣābhiṣutāni ca 39c./d. avantisoma-dhānyāmla-kuñjalāni ca kāñjike

आरनालक-सौवीर-कुल्माषाभिषुतानि च ।३९ क। Bezeichnungen für Sauerschleim (काञ्जिक n.1):

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Sour gruel."

Abb.: Pakhala (ପଖାଳ - पखाळ) = Panta bhat (পান্তা

ভাত), ein Gericht auf der Grundlage von leicht

fermentiertem (saurem) Reis

[Bildquelle: Nayansatya / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

1 काञ्जिक - kañjika n.: saurer Schleim

सन्धितं धान्यमण्डादि काञ्जिकं कथ्यते जनैः ।१ क। "Scum of gruel of cereals and other grains, kept undisturbed for some days and allowed to ferment (become sour) is known as kāñjika."

[Bhāvaprakāśa I, S. 479]

2 आरनालक - āranālaka n.: Āranālaka

कुल्माषधान्यमण्डादिसहितं काञ्जिकं विदुः ।७९ क। "Cooked pulses along with scum of grains (or thin gruel) mixed together is called kāñjika."

[Bhāvaprakāśa I, S. 518]

3 सौवीर - sauvīra n.: saurer Gerstenschleim

यवैस्तु निस्तुषैः पक्वैः सौवीरं साधितं भवेत् ॥७७ ख॥ "If yava (barley) is dehusked an cooked and the water fermented it becomes sauvīra."

[Bhāvaprakāśa I, S. 518]

4 कुल्माष - kulmāṣa n.: Kulmāṣa

अर्धस्विन्नास्तु गोधुमा अन्ये ऽपि चणकादयः ॥१८० ख॥

कुल्माषा इति कथ्यते शब्दशास्त्रेषु पण्डितैः ।१८१ क।"Godhuma (wheat), caṇaka etc. half cooked in steam is known as Kulmāṣa by scholars in literature."

[Bhāvaprakāśa I, 440]

5 अभिषुत - abhiṣuta n.: ausgepresst, "saure Grütze" (PW)

???

6 अवन्तिसोम - avantisoma n.: Avanti-Soma, "saure Grütze" (PW)

???

7 धान्याम्ल - dhānyāmla n.: "Getreide-Saures"

धान्याम्लं शालिचूर्णं च कोद्रवादिकृतं भवेत् ।११ क। "dhānyāmla is prepared by fermenting the powder (flour) of rice or kodrava etc."

[Bhāvaprakāśa I, S. 480]

8 कुञ्जल - kuñjala n.: "saurer Reisschleim" (PW)

???

Apiaceae - Doldenblütler

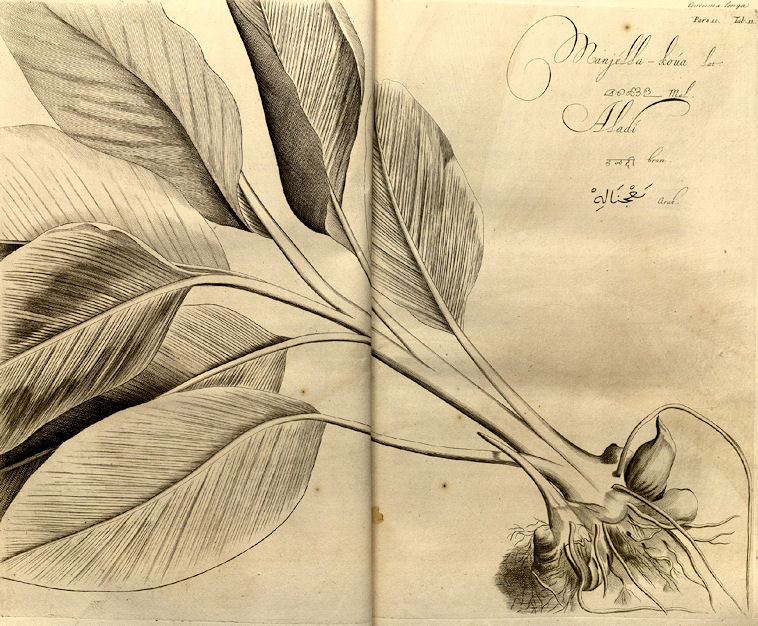

| 40a./b. sahasravedhi jatukaṃ bāhlikaṃ hiṅgu rāmaṭham सहस्रवेधि जतुकं बाह्लिकं हिङ्गु रामठम् ।४० क। [Bezeichnungen für Asafoetida (Harz von Ferula assa-foetida L. 1753):]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Assa foetida."

Abb.: Ferula assa-foetida L. 1753

[Bildquelle: Köhler, 1883-1914]

Abb.: Ferula assa-foetida L. 1753, UK

[Bildquelle: joysaphine. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/joysaphine/3200592445/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-12. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

सहस्रवेधिन् - sahasravedhin n.: "tausendfach durchbohrend, tausendfach durchbohrt", Asafoetida

Abb.: सहस्रवेधि । Asafoetida

[Bildquelle: Efraim Lev and Zohar Amar / Wellcome Images. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

जतुक - jatuka n.: Lack, Gummi, Asafoetida

Abb.: जतुकम् । Asafoetida

[Bildquelle: Miansari66 / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

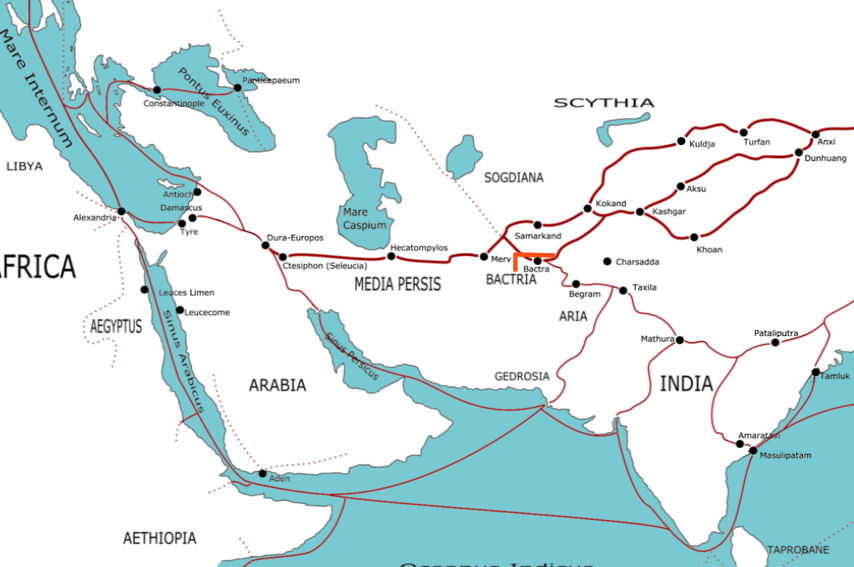

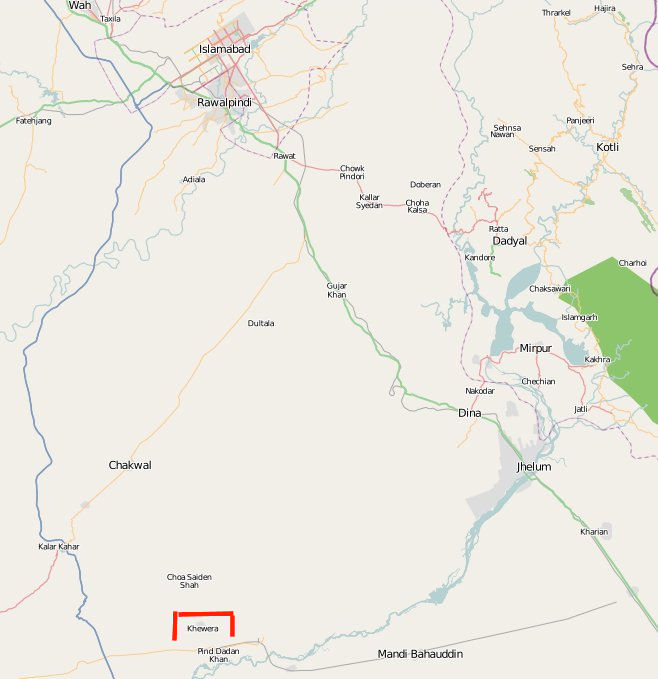

बाह्लिक - bāhlika n.: aus Balkh (

بلخ, Nordafghanistan) stammend, Asafoetida

Abb.: Lage von Balkh (Bactra) an der Seidenstraße

[Bildquelle: Shizhao / Wikipedia. - GNU FDLicense]

Abb.: बाह्लिकम् । Asafoetida

[Bildquelle: alon salant. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/alon/3230734240/. -- Zugriff am 2011-07-12.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine

Bearbeitung)]

हिङ्गु - hiṅgu n.: Teufelsdreck, Asafoetida

Abb.: हिङ्गु । Asafoetida

[Bildquelle: stumptownpanda. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/stumptownpanda/2191729502/. -- Zugriff am

2011-07-12. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

रामठ - rāmaṭha n.: aus Rāmaṭha, Asafoetida

Abb.: रामठम् । Asafoetida-Pulver

[Bildquelle: Iustinus / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Hiṅgu, commonly known as asafoetida, is the resin obtained by scratching the roots of the plant Ferula narthex Boiss., which is found in abundance in Afghanistan, Beluchisthan, Arabis, Iran, etc. In India it is seen in some parts of upper Kashmir. Resin is dried in sun and marketed. Market sample contains extraneous impurities like sticks, stones, fibres etc. Nowadays synthetic (artificially prepared) asafoetida is being used for culinary purposes to enhance the flavour of foods. It is used both in raw state as well as fried (oil or ghee)." [Quelle: Bhāvaprakāśa I, S. 174]

"FERULA FOETIDA, Regel. Fig.—Bentl. and Trim., e. 127 ; Trans. Linn. Soc. 2d. Ser. Botany, Vol. Pt. i., pl 12, 13, 14.

Hab.—Persia, Afghanistan. The gum-resin.

[...9

History, Uses, &c.--Commercial Asafoetida is collected from this plant in Western Afghanistan and Persia; in May, the mature roots begin to send up a flowering stem, which is cut off and the juice collected in the manner described by Kaempfer, who witnessed its collection in the province of Laristan in Persia. It was long supposed that commercial Asafoetida was the produce of F. Narthex, Boiss., a Tibetan plant which was discovered by Falconer in Astor, but there is no evidence of the drug ever having been collected from it. In May, 1884, Dr. Peters, of the Bombay Medical Service, when stationed at Quetta, observed the flowering stem of an Asafoetida plant which was being offered for sale in the bazar as a vegetable by the Kakar Pathans. Specimens which he kindly forwarded to one of us were identified by Mr. E. M. Holmes as F. foetida,, Kegel. Dr. Peters also found the dried root of the same plant in the drug shops, and learned that it was the plant from which Asafoetida was collected in Western Afghanistan. These facts were confirmed by Aitchison in May 1885, both as regards the source of commercial Asafoetida, and the use of the flower stalk as a vegetable. In his report upon the Botany of the Afghan Delimitation Commission, he remarks:—"In all stages of its growth, every part of the plant exudes upon abrasion a milky juice, which is collected and constitutes the drug of commerce. The stem in a young state is eaten raw or cooked." Aitchison says that a red clay called Tawah is mixed with the gum-resin at Herat, a statement which is only applicable to the kind of Asafoetida known in commerce as Kandahari Ring, to be presently noticed. Concerning the Laristan plant we are still without exact information, but we think it will prove to be F. foetida. The remarks made respecting the use of Asafoetida by the natives of India under F. alliacea are more or less applicable to the present article, which is often imposed upon the poorer classes as a substitute for the more expensive Hing. In modern European medicine, Asafoetida is used as a stimulant and antispasmodic in chronic bronchitis, hysteria and tympanitis ; it is often administered in the form of onema, as it is apt to give rise to a sense of weight and heat in the stomach when given by the mouth. Dr. Paolo Negri has reported the successful treatment of two cases of abortion with Asafoatida administered to the extent of one gram daily. In the first case the woman had aborted twice and in the second four times; both patients were free from syphilitic taint, and no cause for the abortion could be detected."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 147ff.]

"FERULA ALLIACEA, Boiss. [= Ferula gabriella Rech. f. 1987] Hab.—Persia. The gum-resin.

[...9