mailto: payer@hdm-stuttgart.de

Zitierweise / cite as:

Mahanama <6. Jhdt n. Chr.>: Mahavamsa : die große Chronik Sri Lankas / übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer. -- 27. Kapitel 27: Einweihung des Lohapasada. -- Fassung vom 2006-07-23. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/mahavamsa/chronik27.htm. -- [Stichwort].

Erstmals publiziert: 2006-07-11

Überarbeitungen: 2006-07-23 [Ergänzungen]; 2006-07-16 [Ergänzungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltungen, Sommersemester 2001, 2006

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Übersetzers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Buddhismus von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Zahlreichen Zitate aus Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. sind ein Tribut an dieses großartige Werk. Das Gesamtwerk ist online zugänglich unter: http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/dic_idx.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-05-08.

Sattavīsatamo paricchedo.

Lohapāsādamaho

Alle Verse mit Ausnahme des Schlussverses sind im Versmaß vatta = siloka = Śloka abgefasst.

Das metrische Schema ist:

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ˉ

Ausführlich zu Vatta im Pāli siehe:

Warder, A. K. (Anthony Kennedy) <1924 - >: Pali metre : a contribution to the history of Indian literature. -- London : Luzac, 1967. -- XIII, 252 S. -- S. 172 - 201.

1 Tato rājā vicintesi vissutaṃ sussutaṃ sutaṃ

Mahāpuñño sadāpuñño paññāya katanicchayo

2 Dīppapasādako thero rājino ayyakassa

me

Evaṃ kirāha: nattā te Duṭṭhagāmaṇi bhūpati

3 Mahāpuñño mahāthūpaṃ Soṇṇamāliṃ

manoramaṃ

Vīsaṃ hatthasataṃ uccaṃ kāressati anāgate

1. - 3.

Da überdachte der König die weithin und wohl bekannte Tradition: "Der verdienstreiche, immer verdienstvolle, seine Beschlüsse in Weisheit fassende, die Insel zum Glauben bringende Thera1 hat zum König2, meinem Vorfahren, so gesprochen3: "König, ein Nachkomme von Dir, der verdienstreiche Duṭṭhagāmaṇī, wird in der Zukunft den großen, schönen Stūpa Soṇṇamāli4 erbauen lassen, der 120 Ellen5 hoch sein wird.

Kommentar:

1 nämlich Mahinda

2 nämlich Devānampiya Tissa

3 siehe Mahāvaṃsa, Kapitel 15, Vers 166ff.

4 Soṇṇamāli = Mahāthūpa (heute: Ruwanawæli-Dagoba) in Anurādhapūra

5 Elle (hattha): die Länge vom Ellbogen bis zur Spitze des Mittelfingers, oft = 24 aṅgula, d.h. ca. 45 cm. 120 hattha ist also ca. 54 m.

4 Puna uposathāgāraṃ

nānāratanamaṇḍitaṃ

Navabhūmiṃ karitvāna Lohapāsādam eva ca

4.

Ebenso wird errichten lassen ein Uposatha-Gebäude1, den neunstöckigen Lohapāsāda2, geschmückt mit vielerlei Juwelen.

Kommentar:

1 Uposatha-Gebäude

Uposatha -- Pāṭimokkharezitation am Vollmondtag und am Neumondtag.

"Uposathāgāra or Uposathagga

A building for the purpose of holding Uposatha is known as Uposathāgāra. It may be a Vihāra, or an Addhayoga, or a Pāsāda, or a Hammiya, or a Guhā. Only one Uposathāgāra is allowed within one Sīmā; and if there are more than one, the offence of Dukkata is committed. To select a. building as an Uposathāgāra the Sangha holds a Ñattidutiyakamma for the purpose. (Mv. pp. 109-110). In case more than one buildings have already been selected as the Uposathāgāra, only one should be retained and the others should be cancelled by holding a Ñattidutiyakamma, (Ibid.)."[Quelle: Upasak C. S. (Chandrika Singh): Dictionary of early Buddhist Monastic terms : (based on Pali literature). -- Varanasi : Bharati Prakashan, 1975. -- III, 245 S. ; 25 cm. -- s.v.]

2 Lohapāsāda: "Kupfer-Palast"

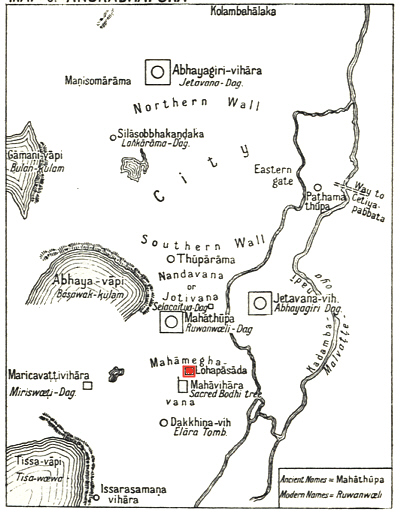

Abb.: Lage des Lohapāsāda in Anurādhapura

[Bildquelle: Mahānāma <5. Jhd. n. Chr.>: The Mahavamsa or, The great chronicle of Ceylon / translated into English by Wilhelm Geiger ... assisted by Mabel Haynes Bode...under the patronage of the government of Ceylon. -- London : Published for the Pali Text Society by H. Frowde, 1912. -- 300 S. -- (Pali Text Society, London. Translation series ; no. 3). -- Vor S. 137.]

Abb.: Lohapāsāda um 1850

[Quelle der Abb.: Tennent, James Emerson <1804-1869>: Ceylon: an account of the island. -- 2nd ed. -- London : Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1859. -- 2 Bde. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Bd. 1, S. 357.]

"Lohapāsāda A building at Anurādhapura, forming the uposatha hall of the Mahāvihāra. It was originally built by Devānampiyatissa (see Mhv.xv.205), but it was then a small building erected only to round off the form of Mahā vihāra (vihāraparipunnamattasādhakam) (MT. 364). Later, Dutthagāmani pulled it down and erected on its site a nine storey building, one hundred cubits square and high, with one hundred rooms on each storey. The building was planned according to a sketch of the Ambalatthikapāsāda (the actual Ambalatthikā (q.v.) of the Lohapāsāda was to the east of the building, DA.ii.635) in Bīranī's palace which eight arahants obtained from the deva world. The building was roofed with copper plates, hence its name. The nine storeys were occupied by monks, according to their various attainments, the last four storeys being reserved for arahants. In the centre of the hall was a seat made in the shape of Vessavana’s Nārīvāhana chariot (for details see Mhv.xxvii.1ff). The building was visible out at sea to a distance of one league (MT. 505). Once Dutthagāmani attempted to preach in the assembly hall of the Lohapāsāda, but he was too nervous to proceed. Realizing then how difficult was the task of preachers, he endowed largesse for them in every vihāra (Mhv.xxxii.42ff). Dutthagāmani had always a great fondness for the Lohapāsāda, and as he lay dying he managed to have a last view of it (Mhv.xxxii.9). Thirty crores were spent on its construction; in Saddhātissa's day it caught fire from a lamp, and he rebuilt it in seven storeys at a cost of nine millions.

Khallātanāga built thirty two other pāsādas round the Lohapāsāda for its ornamentation (Mhv.xxxiii.6), while Bhātikābhaya carried out various repairs to the building (Mhv.xxxiv.39), and Amandagāmanī added an inner courtyard and a verandah (ājira) (Mhv.xxxv.3). Sirināga I. rebuilt it in five storeys (Mhv.xxxvi.25,52), Abhayanāga built a pavilion in the courtyard and Gothābhaya had the pillars renewed (Mhv.xxxvi.102).

He evidently started to rebuild the structure, because we are told (Mhv.xxxvi.124) that, after his death, his son Jetthatissa completecd up to seven storeys the Lohapāsāda which had been left unfinished (vippakata) by his father.

The building was worth one crore, and Jetthatissa offered to it a jewel worth sixty thousand, after which he renamed it Manipāsāda. Afterwards Sona, a minister of his brother, the renegade king Mahānāma, acting on the advice of heretical monks led by Sanghamitta, destroyed the pāsāda and carried away its wealth to enrich Abhayagiri vihāra (Mhv.xxxvii.10f,59).

Mahānāma's son, Sirimeghavanna, had the pāsāda restored to its original form (Mhv.xxxvii.62), and, later, Dhātusena renovated it (Mhv.xxxviii.54), as did Aggabodhi I., who distributed the three garments to thirty six thousand monks at the festival of dedication and assigned a village to provide for its protection (Mhv.xlii.20). His successor, Aggabodhi II., deposited in the pāsāda the Buddha's right collar bone, which relic was later transferred to the Thūpārāma (Mhv.xlii.53,59). In the reign of Aggabodhi IV., the ruler of Malaya repaired the central pinnacle (Mhv.xlvi.30), while Mānavamma provided a new roof (Mhv.xlvii.65). Sena II. completely restored the pāsāda and placed in it an image of the Buddha in gold mosaic. The building was evidently not in use at the time, but he provided for its upkeep and assigned villages for its protection, and decreed that thirty two monks should be in constant residence (Mhv.li.69f). Sena IV. was in the habit of preaching in the Lohapāsāda periodical sermons to the monks (Mhv.liv.4) which were based on the suttas, but, after his death, the place again fell into disrepair and was destroyed by the Colas. Parakkamabāhu I. restored it once again (Mhv.lxxviii.102), but it was soon after pillaged again and fell into ruin, in which state it remains to this day. There are now sixteen hundred monolithic stone columns (the same number as in the time of Parakkamabāhu I.), which evidently formed the framework of the lowest storey.

Frequent mention is made in the books of sermons preached in the lowest storey of the Lohapāsāda, at which very large numbers were present. Once, when Ambapāsānavāsī Cittagutta preached the Rathavinīta Sutta, there were twelve thousand monks and one thousand nuns (MT.552f). On another occasion, Bhātikābhaya described the contents of the Relic chamber of the Mahā Thūpa to all the monks of the Mahāvihāra assembled in the Lohapāsāda (MT.555).

Buddhaghosa says (DA.ii.581) that, up to his day, it was customary for all the monks of Ceylon, who lived to the north of the Mahāvālukanadī, to assemble in the Lohapāsāda twice a year, on the first and last days of the vassa, while those to the south of the river assembled at the Tissamahāvihāra. When disputes arose as to the interpretation of various rules or teachings, the decision was often announced by a teacher of repute from the lowest storey of the Lohapāsāda (DA.ii.442, 514).

The hood of the Nāga king Mucalinda was of the same size as the storehouse (bhandāgāragabbha) of the Lohapāsāda (UdA.101). A mass of rock, as big as the seventh storey of the Lohapāsāda, if dropped from the Brahmaworld, would take four months to reach the earth. DA.ii.678."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

5 Iti cintīya bhūmindo likhitvevaṃ

ṭhapāpitaṃ

Pekkhāpento rājagehe ṭhitaṃ eva karaṇḍake

6 Sovaṇṇapaṭṭaṃ laddhāna lekhaṃ tattha

avācayi:

Cattiṃsasatavassāni atikkamma anāgate

7 Kākavaṇṇasuto Duṭṭhagāmaṇī

manujādhipo

Idañ c' idañ ca evañ ca kāressatī ti vācitaṃ

8 Sutvā haṭṭho udānetvā apphoṭesi

mahīpati;

Tato pāto va gantvāna Mahāmeghavanaṃ subhaṃ

5. - 8.

So dachte der König und ließ nach einer beschriebenen Goldplatte nachschauen, die in einem Korb im Königspalast aufbewahrt wurde. Als er sie erhalten hatte ließ er die Schrift darauf vorlesen: "Nach 136 Jahren wird König Duṭṭhagāmaṇī, der Sohn Kākavaṇṇa's, das und das so und so machen lassen." Als er das hörte, war der König froh, machte einen Freudenschrei und schnalzte mit den Fingern. Dann ging er am Morgen zum schönen Mahāmeghavana1.

Kommentar:

1 Mahāmeghavana:

"Mahāmeghavana A park to the south of Anurādhapura. Between the park and the city lay Nandana or Jotivana. The park was laid out by Mutasīva, and was so called because at the time the spot was chosen for a garden, a great cloud, gathering at an unusual time, poured forth rain (Mhv.xi.2f). Devānampiyatissa gave the park to Mahinda for the use of the Order (Mhv.xv.8, 24; Dpv.xviii.18; Sp.i.81) and within its boundaries there came into being later the Mahā-Vihāra and its surrounding buildings. The fifteenth chapter of the Mahāvamsa (Mhv.xv.27ff) gives a list of the chief spots associated with the religion, which came into existence there. Chief among these are the sites of the Bodhi tree, the thirty two mālakas, the Catussālā, the Mahā Thūpa, the Thūpārāma, the Lohapāsāda, and various parivenas connected with Mahinda: Sunhāta, Dīghacankamana, Phalagga, Therāpassaya, Marugana and Dīghasandasenāpati. Later, the Abhayagīri vihāra and the Jetavanārāma were also erected there.

The Mahāmeghavana was visited by Gotama Buddha (Mhv.i.80; Dpv.ii.61, 64), and also by the three Buddhas previous to him. In the time of Kakusandha it was known as Mahātittha, in that of Konagamana as Mahānoma, and in that of Kassapa as Mahāsāgara (Mhv.xv.58, 92, 126).

The Mahāmeghavana was also called the Tissārāma, and on the day it was gifted to the Sangha, Mahinda scattered flowers on eight spots contained in it, destined for future buildings, and the earth quaked eight times (Mhv.xv.174). This was on the day of Mahinda's arrival in Anurādhapura. The first building to be erected in the Mahāmeghavana was the Kālapāsāda parivena (q.v.) for the use of Mahinda. In order to hurry on the work, bricks used in the building were dried with torches (Mhv.xv.203). The boundary of the Mahāmeghavana probably coincided with the sīmā of the Mahāvihāra, but it was later altered by Kanitthatissa, when he built the Dakkhina vihāra. Mhv.xxxvi.12. For a deposition of the various spots of the Mahāmeghavana see Mbv.137."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

9 Sannipātaṃ kārayitvā

bhikkhusaṅghassa abravi:

Vimānatulyaṃ pāsādaṃ kārayissāmi vo ahaṃ;

9.

Er ließ die Mönchsgemeinde zusammenkommen und sprach zu ihr: "Ich werde für euch einen Palast bauen lassen, der einem Götterpalast gleich ist.

10 Dibbavimānaṃ pesetvā tadālekhaṃ

dadātha me.

Bhikkhusaṅgho visajjesi aṭṭha khīṇāsave tahiṃ.

10.

Schickt nach einem himmlischen Palast und gebt mir eine Zeichnung davon!" Die Mönchsgemeinde sandte acht Arhants dorthin.

11 Kassapamunino kāle Asoko nāma

brāhmaṇo

Aṭṭha salākabhattāni saṅghassa pariṇāmiya

12 Bīraṇiṃ nāma dāsiṃ so niccaṃ dehī

ti appayi

Datvā sā tāni sakkaccaṃ yāvajīvaṃ tato cutā

13 Ākāsaṭṭhāvimānamhi nibbatti rucire

subhā,

Accharānaṃ sahassena sadāsi parivāritā.

11. - 13.

Zur Zeit des Weisen Kassapa1 hatte ein Brahmane namens Asoka der Ordensgemeinde acht Los-Essen2 zugewiesen und einer Dienerin namens Bīraṇī3 aufgetragen, diese täglich zu geben. Sie gab diese ehrfurchtsvoll so lange sie lebte. Als sie starb, wurde sie als Schönheit in einem prächtigen in der Luft schwebenden4 himmlischen Palast wiedergeboren. Sie wurde ständig von 1000 himmlischen Nymphen (Apsaras)5 bedient.

Kommentar:

1 Kassapa

"Kassapa Buddha. Also called Kassapa Dasabala to distinguish him from other Kassapas.

The twenty-fourth Buddha, the third of the present neon (the Bhaddakappa) and one of the seven Buddhas mentioned in the Canon (D.ii.7).

- He was born in Benares, in the Deer Park at Isipatana,

- of brahmin parents, Brahmadatta and Dhanavatī, belonging to the Kassapagotta.

- For two thousand years he lived in the household, in three different palaces, Hamsa, Yasa and Sirinanda. (The BuA.217 calls the first two palaces Hamsavā and Yasavā).

- He had as chief wife Sunandā, by whom he begot a son, Vijitasena.

- Kassapa left the world, traveling in his palace (pāsāda), and practiced austerities for only seven days.

- Just before his Enlightenment his wife gave him a meal of milk-rice, and a yavapāla named Soma gave him grass for his seat.

- His bodhi was a banyan-tree, and

- he preached his first sermon at Isipatana to a crore of monks who had renounced the world in his company.

- He performed the Twin-Miracle at the foot of an asana-tree outside Sundaranagara.

- He held only one assembly of his disciples; among his most famous conversions was that of a yakkha, Naradeva (q.v.).

- His chief disciples were Tissa and Bhāradvāja among monks, and Anulā and Uruvelā among nuns, his constant attendant being Sabbamitta.

- Among his patrons, the most eminent were Sumangala and Ghattīkāra, Vijitasenā and Bhaddā.

- His body was twenty cubits high, and,

- after having lived for twenty thousand years, he died in the Setavya pleasance at Setavyā in Kāsī.

- Over his relics was raised a thūpa one league in height, each brick of which was worth one crore.

It is said (MA.i.336ff ) that there was a great difference of opinion as to what should be the size of the thūpa and of what material it should be constructed; when these points were finally settled and the work of building had started, the citizens found they had not enough money to complete it. Then an anāgāmī devotee, named Sorata, went all over Jambudīpa, enlisting the help of the people for the building of the thūpa. He sent the money as he received it, and on hearing that the work was completed, he set out to go and worship the thūpa; but he was seized by robbers and killed in the forest, which later came to be known as the Andhavana.

Upavāna, in a previous birth, became the guardian deity of the cetiya, hence his great majesty in his last life (DA.ii.580; for another story of the building of the shrine see DhA.iii.29).

Among the thirty-seven goddesses noticed by Guttila, when he visited heaven, was one who had offered a scented five-spray at the cetiya (J.ii.256). So did Alāta offer āneja-flowers and obtain a happy rebirth (J.vi.227).

The cause of Mahā-Kaccāna's golden complexion was his gift of a golden brick to the building of Kassapa's shrine (AA.i.116).

At the same cetiya, Anuruddha, who was then a householder in Benares, offered butter and molasses in bowls of brass, which were placed without any interval around the cetiya (AA.i.105).

Among those who attained arahantship under Kassapa is mentioned Gavesī, who, with his five hundred followers, strove always to excel themselves until they attained their goal (A.iii.214ff).

Mahākappina, then a clansman, built, for Kassapa's monks, a parivena with one thousand cells (AA.i.175).

Bakkula's admirable health and great longevity were due to the fact that he had given the first fruits of his harvest to Kassapa's monks (MA.iii.932).

During the time of Kassapa Buddha, the Bodhisatta was a brahmin youth named Jotipāla who, afterwards, coming under the influence of Ghatīkāra, became a monk. (Bu.xxv.; BuA.217ff; D.ii.7; J.i.43, 94; D.iii.196; Mtu.i.303ff, 319). This Ghatīkāra was later born in the Brahma-world and visited Gotama, after his Enlightenment. Gotama then reminded him of this past friendship, which Ghatīkāra seemed too modest to mention (S.i.34f).

The Majjhima Nikāya (M.ii.45f ) gives details of the earnestness with which Ghatīkāra worked for Jotipāla's conversion when Kassapa was living at Vehalinga. The same sutta bears evidence of the great regard Kassapa had for Ghatīkāra.

The king of Benares at the time of Kassapa was Kikī, and the four gateways of Kassapa's cetiya were built, one by Kikī, one by his son Pathavindhara, one by his ministers led by his general, and the last by his subjects with the treasurer at their head (SnA.i.194).

It is said that the Buddha's chief disciple, Tissa, was born on the same day as Kassapa and that they were friends from birth. Tissa left the world earlier and became an ascetic. When he visited the Buddha after his Enlightenment, he was greatly grieved to learn that the Buddha ate meat (āmagandha), and the Buddha preached to him the Āmagandha Sutta, by which he was converted (SnA.i.280ff).

The Ceylon Chronicles (Mhv.xv.128ff; Sp.i.87; Dpv.xv.55ff; Mbv.129) mention a visit paid by Kassapa to Ceylon in order to stop a war between King Jayanta and his younger brother. The island was then known as Mandadīpa, with Visāla as capital. The Buddha came with twenty thousand disciples and stood on Subhakūta, and the armies seeing him stopped the fight. In gratitude, Jayanta presented to the Buddha the Mahāsāgara garden, in which was afterwards planted a branch of the Bodhi-tree brought over by Sudhammā, in accordance with the Buddha's wish. The Buddha preached at the Asokamālaka, the Sudassanamālaka and the Somanassamālaka, and gave his rain-cloak as a relic to the new converts, for whose spiritual guidance he left behind his disciples Sabbananda and Sudhammā and their followers. In Kassapa's time Mt. Vepulla at Rājagaha was known as Supassa and its inhabitants as the Suppiyas (S.ii.192).

But many other places had the same names in the time of Kassapa as they had in the present age - e.g., Videha (J.vi.122), Sāvatthi (J.vi.123), Kimbila (J.vi.121) and Bārānasī. (J.vi.120).

Besides the āmagandha Sutta mentioned above, various other teachings are mentioned as having been first promulgated by Kassapa and handed on down to the time of Gotama and re-taught by him. Such, for instance, are the questions (pucchā) of Ālavaka and Sabhiya and the stanzas taught to Sutasoma by the brahmin Nanda of Takkasilā (J.v.476f; 453). The Mittavinda Jātaka (No.104) is mentioned as belonging to the days of Kassapa Buddha (J.i.413).

Mention is also made of doctrines which had been taught by Kassapa but forgotten later, and Gotama is asked by those who had heard faint echoes of them to revive them (E.g., MA, i.107, 528; AA.i.423). A sermon attributed to Kassapa, when he once visited Benares with twenty thousand monks, is included in the story of Pandita-Sāmanera (DhA.ii.127ff). It was on this occasion that Kassapa accepted alms from the beggar Mahāduggata in preference to those offered by the king and the nobles.

Kassapa held the uposatha only once in six months (DhA.iii.236).

Between the times of Kassapa and Gotama the surface of the earth grew enough to cover Sūkarakata-lena (MA.ii.677).

The records of Chinese pilgrims contain numerous references to places connected with Kassapa. Hiouien Thsang speaks of a stūpa containing the relics of the whole body of the Buddha, to the north of the town, near Srāvasti, where, according to him, Kassapa was born (Beal, op. cit., ii.13). Mention is also made of a footprint of Kassapa (Ibid.i., Introd. ciii). Stories of Kassapa are also found in the Divyāvadāna (E.g., pp.22f; 344f; 346f; see also Mtu., e.g., i.59, 303f).

The Dhammapada Commentary (iii.250f ) contains a story, which seems to indicate that, near the village of Todeyya, there was a shrine thought to be that of Kassapa and held in high honour by the inhabitants of the village. After the disappearance of Kassapa's Sāsana, a class of monks called Setavattha-samanavamsa ("white-robed recluses") tried to resuscitate it, but without success (VibhA.432)."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

2 Los-Essen (salākabhatta) (行籌食)

"Salākā-Bhatta

A meal allotted by the Saṅgha by the method of tickets (Salākā) or lot is known as Salākā-bhatta,

This method is followed when there are too many invitations; or when there is a possibility of getting a rich Dāna; or when the number of invitation is less than the number of the monks. For the purpose of assigning such meals, the Saṅgha selects a competent monk who is known as Bhattudesaka. (Cv. p. 272; Cf. SP. Vol. Ill, pp. 1347-1353).

The Buddha allowed this method for the monks. (Cv. p. 55)."[Quelle: Upasak C. S. (Chandrika Singh): Dictionary of early Buddhist Monastic terms : (based on Pali literature). -- Varanasi : Bharati Prakashan, 1975. -- III, 245 S. ; 25 cm. -- s.v.]

3 Bīraṇī

"Bīrāṇī A goddess (devadhītā).

She had a palace in the Cātummahārājika world which Nimi saw on his visit to heaven when he learnt her story from Mātali. In the time of Kassapa Buddha she had been a slave in a brahmin's house. The brahmin, whose name was Asoka, invited eight monks to feed daily at his house and asked his wife to arrange to feed them at a cost of one kahāpana each. This she refused to do as did also his daughters; but their slave agreed to carry out this work, and she did it most conscientiously and with great devotion. As a result she was reborn in heaven (J.vi.117f). Her palace was twelve leagues in height and one in extent; it possessed nine storeys and one thousand rooms. When Dutthagāmanī wished to erect the Lohapāsāda, he asked the monks for a plan, and eight arahants went to the deva world and returned with a plan of Bīranī's palace. Mhv.xxvii.9ff."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

4 in der Luft schwebenden: da vimāna's als in der Luft schwebend oder fliegend beschrieben werden, dienen sie einerseits dazu, die vedische Kultur als supermodern zu beschreiben, als auch als Beleg für die Prä-Astronautik (Däniken u.a.)

"A vimāna is a mythical flying machine, described in the ancient literature of India. References to flying machines are commonplace in ancient Indian texts, which even describe their use in warfare. Apart from being able to fly within the Earth's atmosphere, vimānas were also said to be able to travel into space and travel submerged under water. Descriptions in the Vedas and later Indian literature detail vimānas of various shapes and sizes:

- In the Vedas: the sun and several other vedic deities are transported in their peregrinations by flying, wheeled chariots pulled by animals, usually horses (the Vedic god Pūsan's chariot is however pulled by goats).

- The "agnihotra-vimāna" with two engines. (Agni means fire in Sanskrit.)

- The "gaja-vimāna" with more engines. (Gaja means elephant in Sanskrit.)

- Other types named after the kingfisher, the ibis, and other animals.

Some modern UFO enthusiasts have pointed to the Vimana as evidence for advanced technological civilizations in the distant past, or as support for the ancient astronaut theory. Others have linked the flying machines to the legend of the Nine Unknown Men."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vimana. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-11]

5 Apsaras

"Apsaras (Sanskrit, f., अप्सरस, apsarāḥ, plural: apsarasaḥ, Wortstamm: apsaras-; Pali Accharā, jap. Tennin [伝説の生物], chin. Tiannu) sind in der hinduistischen und Teilen der buddhistischen Mythologie halb menschliche, halb göttliche Frauen, die im Palast des Gottes Indra leben. Apsaras gelten auch als „Geister“ der Wolken und Gewässer und sind in dieser Hinsicht den Nymphen der griechischen und römischen Mythologie vergleichbar. Apsaras im Hinduismus

Im Rigveda, dem ab etwa 1200 v.Chr. entstandenen und damit ältesten Veda, wird eine Apsara als Gefährtin des Gandharva genannt, der eine Personifizierung des Lichts der Sonne ist und den Soma, den Trank der Götter, zubereitet.In späteren Schriften nimmt die Zahl der Apsaras zu. Geschaffen von Brahma sind sie „Hofdamen“ im himmlischen Palast des Gottes Indra. Als himmlische Tänzerinnen sind sie die Gefährtinnen der nun ebenfalls in größerer Zahl erwähnten Gandharvas, die als himmlische Musiker beschrieben werden. Hauptaufgabe der Apsaras und Gandharvas ist es, die Götter und Göttinnen zu unterhalten. Manche Mythen erzählen auch davon, dass Apsaras nach dem Tod besonders verdienstvoller Helden oder Könige zu deren Gefährtinnen wurden.

Unter allen Apsaras, gemäß der Überlieferung bewohnen insgesamt 26 den Himmelspalast, nehmen Rambha, Urvashi, Menaka und Tilottama eine besondere Stellung ein. Diese vier werden von Indra wiederholt zu den Menschen auf der Erde ausgesandt, um Weise, die mit ihrer Enthaltsamkeit und ihrem Streben nach spiritueller Perfektion eine Gefahr für Indras oder anderer Götter Vormachtstellung zu werden drohen, zu verführen und von ihrem Weg abzubringen. Beispielsweise wird im Ramayana die Geschichte erzählt, wie Indra die Apsara Menaka zum Brahmanen Vishvamitra sendet, um diesen von seiner Meditation abzulenken, was ihr auch gelingt.

Die Namen vieler aus den großen indischen Epen Mahabharata und Ramayana bekannter Apsaras sind in Indien beliebte Frauennamen; darunter beispielsweise Urvashi (die Schönste der Apsaras), Menaka, Rambha, Parnika, Parnita, Subhuja, Vishala, Vasumati (Apsara „von unvergleichlichem Glanz“) und Surotama.

Apsaras in Angkor

Drei der etwa 1850 Apsaras im Angkor Wat, Kambodscha)Einen besonderen Stellenwert erhielten Apsaras in der Mythologie der Khmer zur Zeit des historischen Konigreiches Kambuja, mit der heute als Angkor bekannten Hauptstadt (9. bis 15. Jahrhundert, Kambodscha). Eine Legende erzählt davon, dass König Jayavarman II., der als Gründer des Reiches Kambuja gilt, das Reich von Indra, dem König der Götter, zugewiesen bekam. Zugleich präsentierten die Apsaras den Menschen von Kambuja die Kunst des Tanzes.

Darstellungen der himmlischen, halb göttlichen, Tänzerinnen wurden in Angkor an vielen Tempelwänden in den Stein gehauen. Alleine im Angkor Wat finden sich insgesamt etwa 1850 Abbildungen, von denen keine einer anderen gleicht.

Die Tradition des höfischen Tanzes in Kambodscha, manchmal Apsara-Tanz genannt, geht auf den Königshof in Angkor zurück. Dieser kunstvolle Tanz hatte auch großen Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der, im Westen bekannteren, thailändischen Tanzkunst.

Apsaras im Buddhismus

Kambodschanische Apsaratänzerin[...]

Apsaras finden sich beispielsweise in einer Erzählung der Jatakas ("Geburtsgeschichten") in denen von den Taten des Buddha in seinen früheren Leben erzählt wird. Die Catudvara-Jataka berichtet vom habgierigen und den weltlichen Genüssen anhängenden Mittavinda, der auf seinen Reisen neben anderen auch einigen Apsaras begegnet. Am Ende wird er von Buddha - in einer seiner früheren Inkarnationen als Bodhisattva - belehrt, dass alle weltlichen Genüsse vergänglich sind.

Insbesondere in Ost- und Südostasien wurden Apsaras im Zuge des Synkretismus auch in die buddhistische Ikonographie aufgenommen. So finden sich Darstellungen auch in buddhistischen Tempelanlagen unter anderem in der heutigen Volksrepublik China, Kambodscha, Thailand und Indonesien."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apsara. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-07]

14 Tassā ratanapāsādo

dvādasayojanuggato

Yojanānaṃ parikkhepo cattāḷīsañ ca aṭṭha ca,

14.

Ihr Juwelenpalast war 12 Yojana1 hoch. Sein Umfang war 48 Yojana.

Kommentar:

1 1 Yojana: ca. 11 km. Der Palst war also ca. 130 km. hoch und hatte einen Umfang von ca. 530 km.

15 Kūṭāgārasahassena maṇḍito

navabhūmiko,

Sahassagabbhasampanno rañjamāno catummukho

15.

Er war mit tausend Erkern geschmückt, hatte neun Stockwerke, 1000 Zimmer, glänzende Farben und vier Fassaden.

16 Sahassasaṅkhasaṃyutti

sīhapañjaranettavā,

Sakiṅkiṇikajālāya sajjito vedikāya ca,

16.

Er hatte tausend Muschelketten, hatte Löwenkäfig-Fenster1, und einen Balustrade (vedikā)2 mit einem Netz mit Glöckchen.

Kommentar:

1 Löwenkäfig-Fenster: d.h. wohl vergitterte Fenster

17 Ambalaṭṭhikapāsādo tassa majjhe

subho ahū.

Samantato dissamāno paggahītadhajākulo.

17.

In der Mitte des Gebäudes war der schöne Ambalaṭṭhika-Palast, von allen Seiten sichtbar, bedeckt mit gehissten Fahnen.

18 Tāvatiṃsaṃ ca gacchantā disvā therā

tam eva te

Hiṅgulinā tadālekhaṃ lekhayitvā paṭe tato.

18.

Die Theras gingen in den Tāvatiṃsa-Himmel1, sahen diesen Palast und machten mit Zinober2 eine Zeichnung davon auf ein Stück Stoff.

Kommentar:

1 Tāvatiṃsa

"Tāvatiṃsa The second of the six deva-worlds, the first being the Cātummahārājika world. Tāvatimsa stands at the top of Mount Sineru (or Sudassana). Sakka is king of both worlds, but lives in Tāvatimsa. Originally it was the abode of the Asuras; but when Māgha was born as Sakka and dwelt with his companions in Tāvatimsa he disliked the idea of sharing his realm with the Asuras, and, having made them intoxicated, he hurled them down to the foot of Sineru, where the Asurabhavana was later established.

The chief difference between these two worlds seems to have been that the Pāricchattaka tree grew in Tāvatimsa, and the Cittapātali tree in Asurabhavana. In order that the Asuras should not enter Tāvatimsa, Sakka had five walls built around it, and these were guarded by Nāgas, Supannas, Kumbhandas, Yakkhas and Cātummahārājika devas (J.i.201ff; also DhA.i.272f). The entrance to Tāvatimsa was by way of the Cittakūtadvārakotthaka, on either side of which statues of Indra (Indapatimā) kept guard (J.vi.97). The whole kingdom was ten thousand leagues in extent (DhA.i.273), and contained more than one thousand pāsādas (J.vi.279). The chief features of Tāvatimsa were its parks - the Phārusaka, Cittalatā, Missaka and Nandana - the Vejayantapāsāda, the Pāricchatta tree, the elephant-king Erāvana and the Assembly-hall Sudhammā (J.vi.278; MA.i.183; cp. Mtu.i.32). Mention is also made of a park called Nandā (J.i.204). Besides the Pāricchataka (or Pārijāta) flower, which is described as a Kovilāra (A.iv.117), the divine Kakkāru flower also grew in Tāvatimsa (J.iii.87). In the Cittalatāvana grows the āsāvatī creeper, which blossoms once in a thousand years (J.iii.250f).

It is the custom of all Buddhas to spend the vassa following the performance of the Yamakapātihāriya, in Tāvatimsa. Gotama Buddha went there to preach the Abhidhamma to his mother, born there as a devaputta. The distance of sixty-eight thousand leagues from the earth to Tāvatimsa he covered in three strides, placing his foot once on Yugandhara and again on Sineru.

The Buddha spent three months in Tāvatimsa, preaching all the time, seated on Sakka's throne, the Pandukambalasilāsana, at the foot of the Pāricchattaka tree. Eighty crores of devas attained to a knowledge of the truth. This was in the seventh year after his Enlightenment (J.iv.265; DhA.iii.216f; BuA. p.3). It seems to have been the frequent custom of ascetics, possessed of iddhi-power, to spend the afternoon in Tāvatimsa (E.g., Nārada, J.vi.392; and Kāladevala, J.i.54).

Moggallāna paid numerous visits to Tāvatimsa, where he learnt from those dwelling there stories of their past deeds, that he might repeat them to men on earth for their edification (VvA. p.4).

The Jātaka Commentary mentions several human beings who were invited by Sakka, and who were conveyed to Tāvatimsa - e.g. Nimi, Guttila, Mandhātā and the queen Sīlavatī. Mandhātā reigned as co-ruler of Tāvatimsa during the life period of thirty-six Sakkas, sixty thousand years (J.ii.312). The inhabitants of Tāvatimsa are thirty-three in number, and they regularly meet in the Sudhammā Hall. (See Sudhammā for details). A description of such an assembly is found in the Janavasabha Sutta. The Cātummahārājika Devas (q.v.) are present to act as guards. Inhabitants of other deva- and brahma-worlds seemed sometimes to have been present as guests - e.g. the Brahmā Sanankumāra, who came in the guise of Pañcasikha. From the description given in the sutta, all the inhabitants of Tāvatimsa seem to have been followers of the Buddha, deeply devoted to his teachings (D.ii.207ff). Their chief place of offering was the Cūlāmanicetiya, in which Sakka deposited the hair of Prince Siddhattha, cut off by him when he renounced the world and put on the garments of a recluse on the banks of the Nerañjarā (J.i.65). Later, Sakka deposited here also the eye-tooth of the Buddha, which Doha hid in his turban, hoping to keep it for himself (DA.ii.609; Bu.xxviii.6, 10).

The gods of Tāvatimsa sometimes come to earth to take part in human festivities (J.iii.87). Thus Sakka, Vissakamma and Mātali are mentioned as having visited the earth on various occasions. Mention is also made of goddesses from Tāvatimsa coming to bathe in the Anotatta and then spending the rest of the day on the Manosilātala (J.v.392).

The capital city of Tāvatimsa was Masakkasāra (Ibid., p.400). The average age of an inhabitant of Tāvatimsa is thirty million years, reckoned by human computation. Each day in Tāvatimsa is equal in time to one hundred years on earth (DhA.i.364). The gods of Tāvatimsa are most handsome; the Licchavis, among earth-dwellers, are compared to them (DhA.iii.280). The stature of some of the Tāvatimsa dwellers is three-quarters of a league; their undergarment is a robe of twelve leagues and their upper garment also a robe of twelve leagues. They live in mansions of gold, thirty leagues in extent (Ibid., p.8). The Commentaries (E.g., SA.i.23; AA.i.377) say that Tāvatimsa was named after Magha and his thirty-two companions, who were born there as a result of their good deeds in Macalagāma. Whether the number of the chief inhabitants of this world always remained at thirty-three, it is impossible to say, though some passages, e.g. in the Janavasabha Sutta, lead us to suppose so.

Sometimes, as in the case of Nandiya, who built the great monastery at Isipatana, a mansion would appear in Tāvatimsa, when an earth-dweller did a good deed capable of obtaining for him birth in this deva-world; but this mansion would remain unoccupied till his human life came to an end (DhA.iii.291). There were evidently no female devas among the Thirty-three. Both Māyā and Gopikā (q.v.) became devaputtas when born in Tāvatimsa. The women there were probably the attendants of the devas. (But see, e.g., Jālini and the various stories of VvA).

There were many others besides the Thirty-three who had their abode in Tāvatimsa. Each deva had numerous retinues of attendants, and the dove-footed (kaktgapādiniyo) nymphs (accharā) of Tāvatimsa are famous in literature for their delicate beauty. The sight of these made Nanda, when escorted by the Buddha to Tāvatimsa, renounce his love for Janapadakalyānī Nandā (J.ii.92; Ud.iii.2).

The people of Jambudīpa excelled the devas of Tāvatimsa in courage, mindfulness and piety (A.iv.396). Among the great achievements of Asadisakumāra was the shooting of an arrow as far as Tāvatimsa (J.ii.89).

Tāvatimsa was also known as Tidasa and Tidiva (q.v.)."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

2 Zinnober

Abb.: Zinnober auf Dolomit, aus Guizhou Provinz (贵州省), China

[Bildquelle: Orbital Joe. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/orbitaljoe/45943253/. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung). -- Zugriff am 2006-07-11]

"Vermilion, also spelled vermillion, when found naturally-occurring, is an opaque reddish orange pigment, used since antiquity, originally derived from the powdered mineral cinnabar. Chemically the pigment is mercuric sulfide, HgS. Like all mercury compounds it is toxic. Today vermilion is most commonly artificially produced by reacting mercury with molten sulfur. Most naturally produced vermilion comes from cinnabar mined in China, giving rise to its alternative name of China red.

As pure sources of cinnabar are rare, natural vermilion has always been extremely expensive. In the middle ages, vermilion was often as expensive as gilding. As of 2006 a 225ml tube of genuine Chinese Vermilion oil paint can cost £200 (US $300).

In painting, vermilion has largely been replaced by the pigment cadmium red, a pigment that is less reactive due to the replacement of mercury with cadmium, especially in certain applications such as watercolors. The last mainstream commercial source in watercolors was from the Belgian artist's materials company Blockx, although the pigment can still be obtained in oils, where it is considered more stable. Unlike mercuric sulfide, cadmium sulfide is available in a large range of warm hues, including hues obtained by the addition of selenium or zinc. The range is from lemon yellow to a dull deep red, sometimes referred to as "cadmium purple".

Vermilion is also the name of the typical color of the natural ground pigment, which is a bright red tinged with orange. It is somewhat similar to the color scarlet. As with cadmium sulfide, mercuric sulfide can be found in a range from a bright orange-toned red to a duller slightly bluish red. The differences in hue are due to the range in the size of the ground particles. The larger the average crystal is, the duller and less orange-toned it appears. It has been theorized that the more coarsely ground "Chinese" form of vermilion is more permanent than the more orange "French" variety. It is also theorized that purification leads to increased stability, as with many other pigments.

HistoryThere is evidence of the use of cinnabar pigment in India and China since prehistory; It was known to the Romans; Pliny the Elder records that it became so expensive that the price had to be fixed by the Roman government. The synthesis of vermilion from mercury and sulfur may have been invented by the Chinese; the earliest known description of the process dates from the 8th century.

The synthetically-produced pigment was used throughout Europe from the 12th century, mostly for illuminated manuscripts, although it remained prohibitively expensive until the 14th century when the technique for synthesizing vermilion was widely known in Europe. Synthetic vermilion was regarded early on as superior to the pigment derived from natural cinnabar. Cennino Cennini mentions that vermilion is

"made by alchemy, prepared in a retort. I am leaving out the system for this, because it would be too tedious to set forth in my discussion all the methods and receipts. Because, if you want to take the trouble, you will find plenty of receipts for it, and especially by asking of the friars. But I advise you rather to get some of that which you find at the druggists' for your money, so as not to lose time in the many variations of procedure. And I will teach you how to buy it, and to recognize the good vermilion. Always buy vermilion unbroken, and not pounded or ground. The reason? Because it is generally adulterated, either with red lead or with pounded brick."

Another red mercury pigment, mercuric iodide, briefly sold in the 19th century to artists as "Scarlet Lake" and "Iodide Scarlet", was more vivid than either vermilion or cadmium red, but it is very light sensitive and few artists used it. One who did was J.W. Turner, an artist infamous for his use of even the most fugitive paints. His response to criticism from a paint dealer was to point out that he was not the one who produced the paints.

Vermilion was frequently adulterated due to its high price, usually with red lead, an inexpensive bright lead oxide pigment that was too reactive to be trustworthy enough for use in art.

"American Vermilion" is the name for a historical vermilion imitation. The Portuguese word for the color red (vermelho) derives from this term.

China red"China red" is another name for the pigment vermilion, which is the traditional red pigment of Chinese art. Chinese name chops are printed with a red cinnabar paste, and vermilion (or cinnabar) is the pigment used in Chinese red lacquer. Cinnabar also has significance in Taoist culture, and was regarded as the color of life and eternity."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vermilion. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-11]

19 Nivattitvāna āgantvā paṭaṃ

saṅghassa dassayuṃ;

Saṅgho paṭaṃ gahetvā taṃ pāhesi rājasantikaṃ

19.

Nach ihrer Rückkehr zeigten sie der Ordensgemeinde das Bild. Die Ordensgemeinde schickte das Bild dem König.

20 Taṃ disvā sumano rājā āgammārāmam

uttamaṃ

Ālekhatulyaṃ kāresi Lohapāsādam uttamaṃ.

20.

Frohen Herzens sah der König das Bild, ging zum hervorragenden Hain1 und ließ den hervorragenden Lohāpasāda gleich wie auf dem Bild bauen.

21 Kammārambhanakāle va catudvāramhi

cāgavā

Aṭṭhaṭṭha satasahassāni hiraññāni ṭhapāpiya

21.

Zu Beginn der Arbeiten ließ der freigebige König je achttausend Goldstücke an jedem der vier Tore hinlegen.

22 Puṭasahassavatthāni dvāre dvāre

ṭhapāpiya

Guḷatelasakkharamadhupūrā ca 'nekacāṭiyo.

22.

Bei jedem Tor ließ er 1000 Körbe voll Kleidern aufstellen und viele Töpfe voll Melassebällchen1, Öl, Kristallzucker2 und Honig.

Kommentar:

1 guḷa = "jaggery" von der Kitulpalme/Toddypalme/Jaggery-Palme (Caryota urens) oder der Palmyrapalme (Borassus flabellifer )

Abb.: guḷa (jaggery)

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia]

Abb.: jaggery-Herstellung, Indien

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"Jaggery [গুড] is the traditional unrefined sugar of India. Although the word is used for the products of both sugarcane and the date palm tree, technically, jaggery refers solely to sugarcane sugar. The sugar made from the sap of the date palm is called gur, and is both more prized and less available outside of the districts where it is made. Hence, outside of these areas, sugarcane jaggery is sometimes called gur to increase its market value. The sago palm and coconut palm are also now tapped for producing jaggery in southern India. In Mexico and South America, similar sugarcane products are known as panela, or piloncillo. All types of the sugar come in blocks or pastes of solidified concentrated sugar syrup heated up to 200°C. Traditionally, the syrup is made by boiling raw sugarcane juice or palm sap in a large shallow round-bottom vessel as shown here.

Jaggery is considered by some to be a particularly wholesome sugar and, unlike refined sugar, retains more mineral salts. Moreover, the process does not involve chemical agents. Indian Ayurvedic medicine considers jaggery to be beneficial in treating throat and lung infections; Sahu and Saxena found that in rats jaggery can prevent lung damage from particulate matter such as coal and silica dust (1994).Jaggery is used as an ingredient in both sweet and savory dishes across India and Sri Lanka. It is also a delicacy in its own right. The great Indian chef and cookbook author Madhur Jaffrey writes about a jaggery board, like a cheese board, as a type of dessert course in a Bengali dinner, with varieties of palm and sugar cane jaggeries offered, differing in taste, color, and solidity. Jaggery is also molded into novelty shapes as a type of candy. Other uses of jaggery include jaggery toffees and jaggery cake made with pumpkin preserve, cashew nuts and spices.

Jaggery is also considered auspicious in many parts of India, and is eaten raw before commencement of good work or any important new venture."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jaggery. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-16]

Abb.: Kitulpalme/Toddypalme/Jaggery-Palme (Caryota urens)

[Bildquelle: http://www.illustratedgarden.org/mobot/rarebooks/page.asp?relation=QK98J311809&identifier=0121. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-23]

© 1995-2005 Missouri Botanical Garden

http://www.illustratedgarden.org2 Kristallzucker: sakkhara, von Zuckerrohr (Saccharum officinarum)

Abb.: Zuckerrohr (Saccharum officinarum)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"The English word "sugar" ultimately originates from the Sanskrit word sharkara (शर्करा) which means "sugar" or "pebble". It probably came to English by way of the French, Spanish and/or Italians who derived their word for sugar from the Arabic al sukkar (whence the Spanish word azúcar, the Old Italian word zucchero, the Old French word zuchre). The Arabs in turn derived their word from the Persian shakar, derived from the original Sanskrit." [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sugar. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-11]

"Kulturgeschichte des Zuckers

- 8.000 v. Chr. - älteste Zuckerrohr-Funde in Melanesien, Polynesien

- 6.000 v. Chr. - Zuckerrohr gelangt von Ostasien nach Indien und Persien

- 600 v. Chr. - Zuckergewinnung in Persien: heißer Zuckerrohrsaft wird in Holz- oder Tonkegel gefüllt, in der Spitze kristallisiert der Zucker, es entsteht der Zuckerhut.

- Spätantike: Saccharum genannter Zucker ist in Rom als Luxusgut der Superreichen nachgewiesen und wird aus Indien bzw. Persien importiert.

- 1100 n. Chr. - Mit den Kreuzfahrern gelangt Zucker erstmalig nach Europa

- Ab ca. 1500 - Zuckerrohr wird weltweit auf Plantagen angebaut, Zucker bleibt ein begehrtes Luxusgut für die Reichen. Es wird als Weißes Gold bezeichnet. Das gemeine Volk süßt nach wie vor mit Honig aus der Zeidlerei.

- 1747 - Andreas Sigismund Marggraf entdeckt den Zuckergehalt der Zuckerrübe.

- 1801 - Der Chemiker Franz Carl Achard schafft die Grundlagen der industriellen Zuckerproduktion. Die erste Rübenzuckerfabrik der Welt entsteht in Cunern/Schlesien.

- 1841 - Erster Würfelzucker der Welt, erfunden von Jakob Christian Rad (Direktor der Datschitzer Zuckerraffinerie in Böhmen) war mit roter Lebensmittelfarbe eingefärbt, weil Juliane Rad (seine Frau) sich beim Herausbrechen aus den vorher üblichen Zuckerhüten den Finger verletzt hatte und ihren Mann daraufhin bat, gleich kleinere Zucker-Portionen herzustellen. Er erfand die Zuckerwürfelpresse, stellte die ersten Würfelzucker her und schenkte die ersten, rot gefärbt, seiner Frau zur Erinnerung an den Vorfall. Frau Rad hatte die blutbespritzten Zuckerstücke dennoch ihren Gästen angeboten, da Zucker damals sehr wertvoll war.

- Ab ca. 1850 - Der Zuckerpreis fällt durch die beginnende industrielle Herstellung. Damit entwickelt sich Zucker zum Gegenstand des täglichen Bedarfs, siehe hierzu auch Abschnitt: Beginn der industriellen Herstellung von Zucker aus Rüben."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zucker. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-11]s

23 Amūlakaṃ kammam ettha na kātabban

ti bhāsiya;

Agghāpetvā kataṃ kammaṃ tesaṃ mūlam adāpayi.

23.

"Kein Werk darf hier ohne Lohn getan werden"1, sprach er, bewertete das getane Werk und entlohnte entsprechend.

Kommentar:

1 damit dem König das Verdienst am Werk zukommt, entlohnt er die Arbeit und fordert keine Fron- oder Zwangsarbeit.

24 Hatthasataṃ hatthasataṃ āsi

ekekapassato

Uccato tattako yeva pāsādo hi catummukho

24.

Der Palast hatte vier Frontseiten und war auf jeder Seite 100 Ellen1 breit und ebenso hoch.

Kommentar:

1 Elle (hattha): die Länge vom Ellbogen bis zur Spitze des Mittelfingers, oft = 24 aṅgula, d.h. ca. 45 cm. 100 hattha ist also ca. 45 m.

25 Tasmiṃ pāsādaseṭṭhasmiṃ ahesuṃ nava

bhūmiyo;

Ekekissā bhūmiyā ca kūṭāgārasatāni ca

25.

In diesem besten aller Paläste gab es neun Stockwerke. In jedem Stockwerk gab es hundert Erker.

26 Kūṭāgārāni sabbāni sajjhunā

khacitān' ahuṃ

Pavālavedikā tesaṃ nānāratanabhūsitā.

26.

Alle Erker waren mit Silber belegt. Ihre Korallenbalustraden waren mit verschiedenerlei Edelsteinen geschmückt.

27 Nānāratanacittāni tāsaṃ padumakāni

pi

Sajjhukiṅkiṅkāpantiparikkhittā ca tā ahuṃ.

27.

Die Lotusornamente auf den Balustraden glitzerten in den Farben verschiedener Edelsteine. Rundherum waren auf ihnen Reihen von Silberglöckchen angebracht.

28 Sahassaṃ tattha pāsāde gabbhā āsuṃ

susaṃkhatā,

Nānāratanakhacitā sīhapañjarabhūsitā

28.

In dem Palast gab es 1000 schön eingerichtete Zimmer, belegt mit allerlei Edelsteinen, geschmückt mit Löwenkäfig-Fenstern.

29 Nārivāhanayānan tu sutvā

Vessavaṇassa so

Tadākāram akāresi majjhe ratanamaṇḍapaṃ.

29.

Als er von Vessavaṇa's Wagen zur Beförderung von Frauen hörte, ließ er nach dessen Muster n der Mitte des Palasts einen Juwelenpavillon erbauen.

Kommentar:

1 Vessavaṇa

"Vessavaṇa One of the names of Kuvera, given to him because his kingdom is called Visānā (D.iii.201; SNA.i.369, etc.). He is one of the Cātummahārājāno and rules over the Yakkhas, his kingdom being in the north (E.g., D.ii.207). In the Ātānātiya Sutta he is the spokesman, and he recited the ātānātiya-rune for the protection of the Buddha and his followers from the Yakkhas who had no faith in the Buddha. D.iii.194; he was spokesman because "he was intimate with the Buddha, expert in conversation, well trained" (DA.iii.962).

He rides in the Nārīvāhana, which is twelve yojanas long, its seat being of coral. His retinue is composed of ten thousand crores of Yakkhas. (SNA.i.379; the preacher’s seat in the Lohapāsāda at Anurādhapura was made in the design of the Nārīvāhana, Mhv.xxvii.29). He is a sotāpanna and his life span is ninety thousand years (AA.ii.718).

The books record a conversation between him and Velukantakī Nandamāta, when he heard her sing the Parāyana Vagga and stayed to listen. When Cūlasubhaddā wished to invite the Buddha and his monks to her house in Sāketa, and felt doubtful about it, Vessavana appeared before her and said that the Buddha would come at her invitation (AA.ii.483).

On another occasion (A.iv.162; on his way to see the Buddha) he heard Uttara Thera preaching to the monks in Dhavajālikā on the Sankheyya Mountain, near Mahisavatthu, and went and told Sakka, who visited Uttara and had a discussion with him.

Once when Vessavana was travelling through the air, he saw Sambhūta Thera wrapt in samādhi. Vessavana descended from his chariot, worshipped the Thera, and left behind two Yakkhas with orders to wait until the Elder should emerge from his trance. The Yakkhas then greeted the Thera in the name of Vessavana and told him they had been left to protect him. The Elder sent thanks to Vessavana, but informed him, through the Yakkhas, that the Buddha had taught his disciples to protect themselves through mindfulness, and so further protection was not needed. Vessavana visited Sambhūta on his return, and finding that the Elder had become an arahant, went to Sāvatthi and carried the news to the Buddha. ThagA.i.46f. Just as he encouraged the good, so he showed his resentment against the wicked; see, e.g., Revatī.

Mention is made of Vessavana's Gadāvudha* and his mango tree, the Atulamba**. Alavaka's abode was near that of Vessavana (SNA.i.240).

* SNA.i.225; the books (e,g., SA.i.249; Sp.ii.440) are careful to mention that he used his Gadāvudha only while he was yet a puthujjana.

** J.iv.324, also called Abbhantaramba (see the Abbharantara Jātaka).

Bimbisāra, after death, was born seven times as one of the ministers (paricaraka) of Vessavana, and, while on his way with a message from Vessavana to Virūlhaka, visited the Buddha and gave him an account of a meeting of the devas which Vessavana had attended and during which Sanankumāra had spoken in praise of the Buddha and his teachings (D.ii.206f). Vessavana seems to have been worshipped by those desiring children. See, e.g., the story of Rājadatta (ThagA.i.403). There was in Anurādhapura a banyan tree dedicated as a shrine to Vessavana in the time of Pandukābhaya (Mhv.x.89). Vessavana is mentioned as having been alive in the time of Vipassī Buddha. When Vipassī died, there was a great earthquake which terrified the people, but Vessavana appeared and quieted their fears (ThagA.i.149). Vessavana accompanied Sakka when he showed Moggallāna round Vejayanta pāsāda. M.i.253; because he was Sakka's very intimate friend (MA.i.476).

As lord of the Yakkhas, it was in the power of Vessavana to grant to any of them special privileges, such as the right of devouring anyone entering a particular pond, etc. See, e.g., DhA.iii.74; J.i.128; iii.325 (Makhādeva). Sometimes, e.g., in the case of Avaruddhaka (DhA.ii.237), a Yakkha had to serve Vessavana for twelve years in order to obtain a particular boon (cf. J.ii.16,17). (Three years at J.iii.502.) Vessavana some times employs the services of uncivilized human beings (paccantamilakkhavāsika) DA.iii.865f. The Yakkhas fear him greatly. If he is angry and looks but once, one thousand Yakkhas are broken up and scattered "like parched peas hopping about on a hot plate" (J.ii.399). This was probably before he became a sotāpanna.

Vessavana, like Sakka, was not the name of a particular being, but of the holder of an office. When one Vessavana died, Sakka chose another as his successor. The new king, on his accession, sent word to all the Yakkhas, asking them to choose their special abodes (J.i.328). It was the duty of Yakkhinīs to fetch water from Anotatta for Vessavana's use. Each Yakkhinī served her turn, sometimes for four, sometimes for five months. But sometimes they died from exhaustion before the end of their term. (DhA.i.40; also J.iv.492; v.21).

Vessavana's wife was Bhuñjatī (q.v.), who, like himself, was a devoted follower of the Buddha (D.ii.270). They had five daughters: Latā, Sajjā, Pavarā, Acchimatī, and Sutā. For a story about them, see VvA.131f.

Punnaka was Vessavana's nephew. J.vi.265, 326.

The pleasures and luxuries enjoyed by Vessavana have become proverbial. See, e.g., Vv.iv. 3, 46 (bhuñjāmi kāmakāmī rājā Vessavano yathā); MT. 676 (Vessavanassa rājaparihārasadisam); cf. J.vi.313.

An ascetic named Kañcanapatti (J.ii.399) is mentioned as having been the favourite of Vessavana. See also Yakkha."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

"Vaiśravaṇa (Sanskrit) or Vessavaṇa (Pāli) is the name of the chief of the Four Heavenly Kings and an important figure in Buddhist mythology. Name

The name Vaiśravaṇa is derived from the Sankrit viśravaṇa "hearing distinctly".

Vaiśravaṇa is also known as Kubera (Sanskrit) or Kuvera (Pāli).

Other names include:

Characteristics

- 多聞天 (simplified characters: 多闻天): Chinese Duō Wén Tiān, Korean Damun Cheonwang (다문천왕), Japanese Tamonten. The characters mean "Much hearing god" or "Deity who hears much".

- 毘沙門天: Chinese Wèishāmén Tiān, Japanese Bishamonten. This is a representation of the sound of the Sanskrit name in Chinese (Vaiśravaṇ → Weishamen) plus the character for "heaven" or "god".

- Tibetan rnam.thos.sras (Namthöse)

The character of Vaiśravaṇa is founded upon the Hindu deity Kubera, but although the Buddhist and Hindu deities share some characteristics and epithets, each of them has different functions and associated myths. Although brought into East Asia as a Buddhist deity, Vaiśravaṇa has become a character in folk religion and has acquired an identity that is partially independent of the Buddhist tradition (cf. the similar treatment of Kuan Yin [觀音]and Yama).

Vaiśravaṇa is the guardian of the northern direction, and his home is in the northern quadrant of the topmost tier of the lower half of Mount Sumeru. He is the leader of all the yakṣas who dwell on the Sumeru's slopes.

He is often portrayed with a yellow face. He carries an umbrella or parasol (chatra) as a symbol of his sovereignty. He is also sometimes displayed with a mongoose, often shown ejecting jewels from its mouth. The mongoose is the enemy of the snake, a symbol of greed or hatred; the ejection of jewels represents generosity.

[...]Vaiśravaṇa in Japan

In Japan, Bishamonten (or just Bishamon) is thought of as an armor-clad god of warfare or warriors and a punisher of evildoers – a view that is at odds with the more pacific Buddhist king described above. Bishamon is portrayed holding a spear in one hand and a small pagoda in the other hand, the latter symbolizing the divine treasure house, whose contents he both guards and gives away. In Shintō [神道] beliefs, he is one of the Japanese Seven Gods of Fortune [七福神].

Bishamon is also called Tamonten (多聞天), meaning "listening to many teachings" because he is the guardian of the places where Buddha preaches. He lives half way down the side of Mount Sumeru.

Vaiśravaṇa in TibetIn Tibet, Vaiśravaṇa is considered a worldly dharmapāla or protector of the Dharma. As guardian of the north, he is often depicted on temple murals outside the main door. He is also thought of as a god of wealth. As such, Vaiśravaṇa is sometimes portrayed carrying a citron, the fruit of the jambhara tree, a pun on another name of his, Jambhala. He is sometimes represented as corpulent and covered with jewels. When shown seated, his right foot is generally pendant and supported by a lotus-flower on which is a conch shell.

Vaiśravaṇa in popular culture

- A character by the name of Uesugi Kenshin [上杉 謙信] from the Playstation 2 game: Samurai Warriors frequently prays to Bishamon for strength on the battlefield. He also attains the title "Bishamonten Avatar" at a certain point. This game was based on historical fact.

- In the video game series, Onimusha [鬼武者] (specifically Onimusha: Warlords) a Bishamon statue is seen in the game.

- Several artifacts in computer, video and role playing games are given the name Bishamon or Bishamonten."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vaishravana. -- Zugriff am 2006-06-16]

"Kubera (also Kuvera or Kuber) is the god of wealth and the lord of Uttaradisha in Hindu mythology. He is also known as Dhanapati, the lord of riches. He is one of the Guardians of the directions, representing the north. Kubera is also the son of Sage Vishrava (hence also called Vaisravana), and in this respect, he is also the elder brother of the Lord of Lanka, Ravana.

He is said to have performed austerities for a thousand years, in reward for which Brahma, the Creator, gave him immortality and made him god of wealth, guardian of all the treasures of the earth, which he was to give out to whom they were destined.

When Brahma appointed him God of Riches, he gave him Lanka (Ceylon) as his capital, and presented him, according to the Mahabharata, with the vehicle pushpaka, which was of immense size and ‘moved at the owner’s will at marvellous speed’. When Ravana captured Lanka, Kubera moved to his city of Alaka, in the Himalaya.

Kubera also credited money to Venkateshwara or Vishnu for his marriage with Padmavati. Thats the reason devotees / people when they go to Tirupati donate money in Venkateshwara's Hundi so that he can pay back to Kubera. According to the Vishnupuran this process will go on till the end of Kali yuga"

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kubera. -- Zugriff am 2006-06-16]

30 Sīhavyagghādirūpehi devatārūpakehi

ca

Ahū ratanamayeh' esa thambhehi ca vibhūsito.

30.

Der Pavillon war mit Säulen aus Edelsteinen geschmückt, auf denen Bilder von Löwen, Tigern, anderen Tieren sowie Gottheiten waren.

31 Muttājālaparikkhepo maṇḍapante

samantato

Pavāḷavedikā cettha pubbevuttavidhā ahu.

31.

Rundherum um den Pavillon lief ein Zaun aus Perlnetz und es gab dort eine Korallenbalustraden in der art, wie sie oben (in Vers 26) beschrieben wurde.

32 Sattaratanacittassa vemajjhe

maṇḍapassa tu

Ruciro dantapallaṅko rammo phaḷikasantharo.

32.

Im Zentrum des in den Farben der sieben Edelsteine1 glitzernden Pavillons war ein glänzender schöner Elfenbeinthron mit einem Sitz aus Bergkristall.

Kommentar:

1 sieben Edelsteine:

- suvaṇṇa - Gold

- rajata - Silber

- muttā - Perle

- maṇi - Edelstein

- veḷuriya - Beryll

- vajira - Diamant

- pavāla - Koralle

33 Dantamayāpassaye 'ttha

suvaṇṇamayasūriyo,

Sajjhumayo candimā ca tārā ca muttakāmayā.

33.

Auf der Elefenbeinrückenlehne des Throns waren eine Sonne aus Gold, ein Mond aus Silber und Sterne aus Perlen.

34 Nānāratanapadumāni tattha tattha

yathārahaṃ,

Jātakāni ca tattheva āsuṃ soṇṇalatantare.

34.

Lotusse aus verschiedenen Edelsteinen war angemessen hier und dort angebracht. Es gab Darstellungen aus den Jātaka's1 in goldenen Ranken.

Kommentar:

1 Jātaka

"Jātaka The tenth book of Khuddaka Nikāya of the Sutta Pitaka containing tales of the former births of the Buddha. The Jātaka also forms one of the nine angas or divisions of the Buddha's teachings, grouped according to the subject matter (DA.i.15, 24).

The canonical book of the Jātakas (so far unpublished) contains only the verses, but it is almost certain that from the first there must have been handed down an oral commentary giving the stories in prose. This commentary later developed into the Jātakatthakathā.

Some of the Jātakas have been included in a separate compilation, called the Cariyā Pitaka. It is not possible to say when the Jātakas in their present form came into existence nor how many of these were among the original number. In the time of the Culla Niddesa, there seem to have been five hundred Jātakas, because reference is made to pañcajātakasatāni (p.80; five hundred was the number seen by Fa Hsien in Ceylon (p.71)). Bas-reliefs of the third century have been found illustrating a number of Jātaka stories, and they presuppose the existence of a prose collection. Several Jātakas exist in the canonical books which are not included in the Jātaka collection. For a discussion on the Jātakas in all their aspects, see Rhys Davids Buddhist India, pp.189ff.

The Dīghabhānakas included the Jātaka in the Abhidhamma Pitaka. (DA.i.15; the Samantapāsādikā (i.251) contains a reference to a Jātakanikāya)."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

35 Mahagghapaccattharaṇe pallaṅke

'timanorame

Manoharāsi ṭhapitā rucirā dantavījanī.

35.

Auf dem unbeschreiblich schönen Thron, auf dem wertvolle Teppiche lagen, war ein prächtiger Edelsteinfächer aufgestellt.

36 Pavālapādukaṃ tattha phaḷikamhi

patiṭṭhitaṃ

Setacchattaṃ sajjhudaṇḍaṃ pallaṅkopari sobhatha.

36.

Über dem Thron strahlte ein weißer Schirm mit einem Fuß aus Koralle, der auf einem Bergkristall stand, und einem silbernen Stab.

37 Sattarattanamayān' ettha

aṭṭhamaṅgalikāni ca

Catuppadānaṃ pantī ca maṇimuttantarā ahuṃ.

37.

Drauf waren die acht Glücksymbole mit den sieben Edelsteinen2 gebildet und Reihen von Vierfüßlern zwischen Edelsteinen und Perlen.

Kommentar:

1 acht Glückssymbole:

- mṛdaṅga - Trommel

- vṛṣabha - Stier

- nāga - Kobra

- vījanī - Fächer

- keśarī - Löwe

- makara - Makara

- patāka - Flagge

- pradīpa - Lampe

Es gibt auch andere Aufzählungen.

Es könnte sich auch um das Acht-Glückssymbols-Yantra (Singhalesisch: Aṭamagala) handeln:

Abb.: Aṭa-magala[Quelle der Abb. und der Aufzählung: Commaraswamy, Ananda K. (Kentish) <1977 - 1947>: Mediaeval Sinhalese art : being a monograph on mediaeval Sinhalese arts and crafts, mainly as surviving in the eighteenth century, with an account of the structure of society and the status of the craftsmen. -- 2d ed. [rev.] incorporating the author’s corrections. -- New York : Pantheon Books, 1956. -- XVI, 344 S. : Ill. -- 29 cm. -- S. 272]

2 sieben Edelsteine: siehe oben zu Vers 32

38 Rajatānañ ca ghaṇṭānaṃ pantī

chattantalambitā

Pāsādachattapallaṅkamaṇḍapāsuṃ anagghikā.

38.

Am Saum des Schirms hingen Reihen von Silberglocken. Der Palast, der Schirm, der Thron und der Pavillon waren unbezahlbar.

39 Mahagghaṃ paññapāpesi mañcapīṭhaṃ

yathārahaṃ,

Tatheva bhummattharaṇaṃ kambalañ ca mahārahaṃ.

39.

Er ließ teure Betten und Stühle entsprechend der Würde aufstellen und sehr wertvolle Bodenbeläge und Wolldecken auslegen.

40 Ācāmakumbhī sovaṇṇā uḷuṅko ca ahū

tahiṃ.

Pāsādaparibhogesu sesesu ca kathā va kā

40.

Der Waschtopf und die dazugehörige Schöpfkelle waren aus Gold. Was sollte man da über die anderen Gebrauchsgegenstände im Palast erzählen!

41 Cārupākāraparivāro so

catudvārakoṭṭhako

Pāsādo 'laṅkato sobhi Tāvatiṃsasabhā viya.

41.

Von einem schönen Wall umgeben, mit vier Wehrtoren war der geschmückte Palast herrlich wie die Versammlungshalle des Tāvatiṃsahimmels.

42 Tambalohiṭṭhakāh' eso pāsādo

chādito ahu,

Lohapāsādavohāro tena tassa ajāyatha.

42.

Der Palast war gedeckt mit Kupferziegeln. Daher kommt sein Name Kupfer-Palast (Loha-pāsāda).

43 Niṭṭhite Lohapāsāde so saṅghaṃ

sannipātayi

Rājā saṅgho sannipati Maricavaṭṭimahe viya.

43.

Als der Lohapāsāda fertiggestellt war, ließ der König die Ordensgemeinschaft zusammenkommen. Die Ordensgemeinschaft versammelte sich wie bei der Einweihung des Maricavaṭṭi-Klosters1.

Kommentar:

1 siehe Mahāvaṃsa, Kapitel 26, Vers 15ff.

44 Puthujjanā va aṭṭhaṃsu bhikkhū

pāṭhamabhūmiyaṃ;

Tepiṭakā dutiyāya sotāpannādayo pana

45 Ekeke yeva aṭṭhaṃsu tatiyādisu

bhūmisu;

Arahanto va aṭṭhaṃsu uddhaṃ catusu bhūmisu.

44.

Mönche, die die Erlösung noch nicht verwirklicht hatten1, wohnten im ersten Stock. Die Kenner des Dreikorbs2 im zweiten Stock. die Stromeingetretenen und die übrigen Erlösten2 wohnten vom dritten Stock an aufwärts. Die Arhants aber wohnten in den obersten vier Stockwerken.

Kommentar:

1 Puthujjana: gewöhnliche Menschen, im Gegensatz zu den Ariya-puggala, den Erlösten

2 Kenner des Dreikorbs: Dreikorb der kanonischen buddhistischen Texte:

- Vinaya-piṭaka n. -- Korb der Ordensdisziplin

- Sutta-piṭaka n. -- Korb der Lehrreden

- Abhidhamma-piṭaka n. -- Korb der philosophischen Darstellung der buddhistischen Lehre (abhidhamma m.)

3 Erlöste: Ariya-puggala m. -- Edle Personen

- Im dritten Stock wohnen: sotāpanna m. -- Stromeingetretener: hat die ersten drei saṃyojana n. -- Fesseln überwunden, nämlich:

- 1. sakkāya-diṭṭhi f. -- Falscher Glaube an ein Ich

- 2. vicikicchā f. -- Zweifel

- 3. sīla-bbata-parāmasa m. -- Hängen an Sittlichkeit und religiösen Gelübden

- im vierten Stock wohnen: sakad-āgāmī m. -- Einmalwiederkehrer: hat die ersten drei saṃyojana n. -- Fesseln überwunden; hat nur noch ganz schwach folgende Fesseln:

- 4. kāma-chanda m. -- Gier nach Objekten der Sinneswelt

- 5. vyāpāda m. -- Übelwollen

- im fünften Stock wohnen: an-āgāmī m. -- Nicht-Wiederkehrer hat die ersten fünf saṃyojana n. -- Fesseln d.h. alle niederen Fesseln) überwunden.

- im sechsten bis neunten Stock wohnen: arahanta m. -- Arahat hat alle zehn saṃyojana n. -- Fesseln überwunden, nämlich die genannten niedrigen und folgende höhere:

- 6. rūpa-rāga m. -- Gier nach der feinstofflichen Welt der Formen

- 7. a-rūpa-rāga m. -- Gier nach der unstofflichen Welt

- 8. māna m. -- Abhängigkeit vom sozialen Feld

- 9. uddhacca n. -- Aufgeregtheit

- 10. avijjā f. -- Nichtwissen

(z.B. Mahālisutta : Dīghanikāya I, 156; Nal I, 133, 1-19; Th 9, 199 - 120)

Damit wird angedeutet, dass im Loha-pāsāda viel mehr Erlöste als andere wohnten, unter den Erlösten wiederum übertreffen die Arhants die übrigen an Zahl (vier Stockwerke!).

46 Saṅghassa datvā pāsādaṃ

dakkhiṇambupurassaraṃ

Rājādattha mahādānaṃ sattāhaṃ pubbakaṃ viya.

46.

Der König übergab der Ordensgemeinde den Palast indem er Schenkungswasser1 goss. Dann veranstaltete der König sieben Tage lang eine große Almosenschenkung wie die vorher (in Kapitel 26, Vers 21ff.) beschriebene.

Kommentar:

1 Wasser über die Hand gießen mit den Schenkungsworten, gehört zum Schenkungsakt.

Abb.: Verdienstschenkung an Tote, Sri Lanka, 1970er-Jahre

(Photo: ©Isamu Maruyama)

47 Pāsādahetu cattāni mahācāgena

rājinā

Anagghāni ṭhapetvāna ahesuṃ tiṃsakoṭiyo.

47.

Die Ausgaben des sehr freigebigen Königs für den Palast beliefen sich auf 300 Millionen [Kahāpaṇa]1, nicht eingerechnet all das, was unbezahlbar ist.

Kommentar:

1 Kahāpaṇa: Sanskrit: Karṣāpaṇa: Silbermünze mit ca. 3,3 g reinem Silber. 30 Koṭi = 30 x 107 = 300 Millionen Kahāpaṇa entspräche 990.000 Kg Silber! Sri Lanka besitzt keine nennenswerten eigenen Silber- oder Goldvorkommen.

40 Nissāre dhananicaye visesasāraṃ

Ye dānaṃ parigaṇayanti sādhupaññā

Te dānaṃ vipulam apetacittasaṅgā

Sattānaṃ hitaparamā dadanti evaṃ

ti

40.

Wohlweise Menschen, die Freigebigkeit als besonders wertvoll halten, während das Aufhäufen von Reichtum wertlos ist, schenken großzügig Gaben, frei von Anhaftung des Herzens, vor allem auf Heil der Lebewesen bedacht.

Kommentar:

Versmaß:

Praharṣiṇī

(13 Silben: 3.10.; Schema: ma na ja ra ga: tryāśābhir manajaragāḥ Praharṣiṇīyam: "In der Praharṣiṇī ist ma na ja ra ga mit Zäsur nach drei und zehn Silben (āśā = die zehn Himmelrichtungen: vier Haupt- und vier Zwischenhimmelsrichtungen sowie unten und oben).")ˉˉˉ˘˘˘˘ˉ˘ˉ˘ˉˉ

ˉˉˉ˘˘˘˘ˉ˘ˉ˘ˉˉ

ˉˉˉ˘˘˘˘ˉ˘ˉ˘ˉˉ

ˉˉˉ˘˘˘˘ˉ˘ˉ˘ˉˉ

Sujanappasādasaṃvegatthāya kate

Mahāvaṃse

Lohapāsādamaho nāma sattavīsamo paricchedo.

Zu Kapitel 28: Beschaffung der Materialien zum Bau des Mahathupa