mailto: payer@hdm-stuttgart.de

Zitierweise / cite as:

Mahanama <6. Jhdt n. Chr.>: Mahavamsa : die große Chronik Sri Lankas / übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer. -- 30. Kapitel 30: Einrichtung der Reliquienkammer. -- Fassung vom 2006-07-23. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/mahavamsa/chronik30.htm. -- [Stichwort].

Erstmals publiziert: 2006-07-23

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltungen, Sommersemester 2001, 2006

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Übersetzers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Buddhismus von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Zahlreichen Zitate aus Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. sind ein Tribut an dieses großartige Werk. Das Gesamtwerk ist online zugänglich unter: http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/dic_idx.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-05-08.

Tiṃsatimo paricchedo

Dhātugabbharacano

Alle Verse mit Ausnahme des Schlussverses sind im Versmaß vatta = siloka = Śloka abgefasst.

Das metrische Schema ist:

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ˉ

Ausführlich zu Vatta im Pāli siehe:

Warder, A. K. (Anthony Kennedy) <1924 - >: Pali metre : a contribution to the history of Indian literature. -- London : Luzac, 1967. -- XIII, 252 S. -- S. 172 - 201.

1 Vanditvāna mahāraja sabbaṃ saṅghaṃ

nimantayi

Yāva cetiyaniṭṭhānā bhikkhaṃ gaṇhatha me iti.

1.

Der Großkönig begrüße die ganze Ordensgemeinschaft und lud sie ein, bis zu Vollendung des Stūpa Almosnespeise von ihm anzunehmen.

2 Saṅgho taṃ nādhivāsesi; anupubbena

so pana

Yācanto yāva sattāhaṃ sattāham adhivasanaṃ

3 Alatthopaḍḍhabhikkhūhi te laddhā sumano ca so

Aṭṭhārasasu ṭhānesu thupaṭṭhānasamantato

4 Maṇḍapaṃ kārayitvāna mahādānaṃ pavattayi

Sattāhaṃ tattha saṅghassa; tato saṅghaṃ visajjayi.

2.

Die Mönchsgemeinde stimmte zu. Dann ging er mit seinen Bitten immer mehr hinunter bis er für eine Woche bat. Für eine Woche erhielt er die Zustimmung der Hälfte der Mönche. Als er diese gewonnen hatte, war er froh und ließ an achtzehn1 Stellen um den Platz des Stūpa herum Pavillions erbauen. Dann ließ er dort während einer Woche ein großes Almosenfest für die Mönchsgemeinde abhalten. Dann entließ er die Mönchsgemeinde.

Kommentar:

1 18 ist eine "besondere" Zahl: 21x32; außerdem ist die Quersumme (wie bei allen Vielfachen von Neun) = 9. 1 + 8 = 9.

5 Tato bheriñ carāpetvā

iṭṭhakāvaḍḍhakī lahuṃ

Sannipātesi; te āsuṃ pañcamattasatāni hi.

5.

Dann ließ er die Trommel1 herumgehen und ließ die Baumeister schnell zusammenkommen. Es waren fünfhundert.

Kommentar:

1 Trommel (bheri)

Abb.: Bheri, Ceylon, um 1850[Quelle der Abb.: Tennent, James Emerson <1804-1869>: Ceylon: an account of the island. -- 2nd ed. -- London : Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1859. -- 2 Bde. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Bd. 1, S. 471.]

6 Kathaṃ karissasi t' eko pucchito āha

bhūpatiṃ:

Pessiyānaṃ sataṃ laddhā paṃsūnaṃ sakaṭaṃ ahaṃ

7a Khepayissāmi ekāhaṃ; taṃ rāja paṭibāhayi.

6. - 7a.

Auf die Frage, wie er es machen würde, antwortete einer dem König: "Mit hundert Arbeitern werde ich an einem Tag eine Wagenladung Sand verbrauchen." Der König wies ihn ab.1

Kommentar:

1 denn: je mehr Sand verbraucht wird, desto unbeständiger und anfälliger für Pflanzenbewuchs wäre der Stūpa.

Abb.: Bewuchs: Abhayagiri-Stūpa in Anurādhapura vor der Ausgrabung, vor 1930

[Bildquelle: Archaeological Survey of Ceylon]

7b Tato upaḍḍhupaḍḍhañ ca paṃsū dve

ammaṇāni ca

8a Āhaṃsu, rājā paṭibāhi caturo te pi vaḍḍhakī.

7b. - 8a.

Dann nannten vier andere Baumeister jeweils die Hälfte1 der Sandmenge bis hinunter zu zwei Scheffel (ammaṇa)2. Auch diese vier wies der König zurück.

Kommentar:

1 d.h.

- der erste: ½ Wagenladung

- der zweite: ¼ Wagenladung

- der dritte. 1/8 Wagenladung

- der vierte 1/16 Wagenladung = 2 Scheffel (ammaṇa)

2 1 ammaṇa (Scheffel) = 11 doṇa (1 doṇa = 64 pasāta (Handvoll)) = 704 Handvoll

8b Atheko paṇḍito byatto vaḍḍhaki āha

bhūpatiṃ;

9 Udukkhale koṭṭayitvā ahaṃ suppehi vaṭṭitaṃ

Piṃsāpayitvā nisade ekaṃ paṃsūnam ammaṇaṃ

8b. - 9.

Da sprach ein weiser und erfahrener Baumeister zum König: "Ich werden den Sand in einem Mörser zerstampfen, dann werde ich ihn worfeln, auf einem Mahlstein mahlen und davon ein Scheffel (ammaṇa) Sand nehmen."

10 Iti vutto anuññāsi tiṇādīn' ettha

no siyuṃ

Cetiyamhīti bhūmindo Indatulyaparakkamo.

10.

Da so auf dem Cetiya keine Gras und ähnliches wachsen würden, stimmte der König dem zu, an Entschlusskraft Indra gleich.

11 Kiṃsaṇṭhānaṃ cetiyaṃ taṃ karissasi

tuvaṃ iti

Pucchi taṃ; taṃkhaṇaṃ yeva Vissakammo tam āvisi.

11.

Er fragte den Baumeister, welche Form er dem Cetiya geben werde. In diesem Augenblick trat Vissakamma1 in den Baumeister.

Kommentar:

1 Vissakamma

"Vissakamma, Vissukamma A deva, inhabitant of Tāvatimsa. He is the chief architect, designer and decorator among the devas, and Sakka asks for his services whenever necessary. Thus he was ordered to build the palace called Dhamma for Mahāsudassana (D.ii.180) and another for Mahāpanāda (J.iv.323; DA.iii.856).

He also built the hermitages for the Bodhisatta in various births - e.g., as

- Sumedha (J.i.7)

- Kuddālapandita (J.i.314)

- Hatthipāla (J.iv.489)

- Ayoghara (J.iv.499)

- Jotipāla (J.v.132)

- Sutasoma (J.v.190)

- Temiya (J.vi.21, 29)

- Vessantara (J.vi.519f)

Vissakamma also built the hermitage for Dukūlaka and Pārikā (J.vi.72).

On the day that the Buddha renounced the world, Sakka sent Vissakamma in the guise of a shampooer to bathe him and clothe him in his royal ornaments (J.i.60; DhA.i.70; BuA.232; he also constructed ponds in which the prince might bathe, AA.i.379); he also sent him to adorn Temiya on the day he left the kingdom (J.vi.12).

Vissakamma erected the jewelled pavilion, twelve leagues in compass, under the Gandamba, where the Buddha performed the Twin Miracle and built the three stairways of jewels, silver and gold, used by the Buddha in his descent from Tāvatimsa to Sankassa (J.iv.265f). He built, the pavilions in which the Buddha and five hundred arahants travelled to Uggapura, at the invitation of Culla Subhaddā. (DhA.iii.470; and again for the journey to Sunāpuranta, MA.ii.1017).

When Ajātasattu deposited his share of the Buddha's relics in a thūpa, Sakka ordered Vissakamma to construct around the thūpa a vālasanghātayanta (revolving wheel?) to prevent anyone from approaching the relics. Later, when Dhammāsoka (Piyadassī) wished to obtain these relics for his vihāra, Vissakamma appeared before him in the guise of a village youth and, by shooting an arrow at the controlling screw of the machine, stopped its revolutions (DA.ii.613, 614).

He constructed the jewelled pavilion in which Sonuttara placed the relies he brought from the Nāga world till the time came for them to be deposited in the Mahā Thūpa, (Mhv.xxxi.76) and on the day of their enshrinement, Vissakamma, acting on Sakka's orders, decorated the whole of Ceylon (Mhv.xxxi.34). He also provided the bricks used in the construction of the Mahā Thūpa (Mhv.xxviii.8). Sometimes he would enter into a workman's body and inspire him with ideas - e.g., in designing the form of the Mahā Thūpa (Mhv.xxx.11). He was also responsible for the construction of the golden vase in which the branch of the Bodhi tree was conveyed to Ceylon (Mhv.xviii.24).

As in the case of Mātalī and Sakka, Vissakamma is evidently the name of an office and not a personal name. Thus, in the Suruci Jātaka (J.iv. 325), Vissakamma is mentioned as a previous birth of Ananda, while, according to the Dhammapada Commentary, the architect who helped Magha and his companions in their good works, was reborn as Vissakamma. DhA.i.272. The story given regarding Vissakamma in SNA.i.233, evidently refers to the Mahākanha Jātaka. The deva who accompanied Sakka in the guise of a dog in that Jātaka was Mātali and not Vissakamma.

See Viśvakarma in Hopkins' Epic Mythology."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

12 Sovaṇṇapātiṃ toyassa purāpetvāna

vaḍḍhaki

Pāṇinā vārim ādāya vāripiṭṭhiyam āhani;

12.

Der Baumeister füllte ein goldenes Gefäß mit Wasser, dann nahm er mit der Hand Wasser und schlug es auf die Wassseroberfläche.

13 Phalikāgolasadisaṃ mahābubbuḷam

uṭṭhahi.

Āh' īdisaṃ karissan ti; tussitvā tassa bhūpati

14 Sahassagghaṃ vatthayugaṃ tathālaṅkārapādukā

Kahapaṇāni dvādasa sahassāni ca dāpayi.

13. - 14.

Es erhob sich eine große Wasserblase1, die einer Bergkristallkugel glich. Der Baumeister sagte, dass er den Stūpa so bauen werde. Der König war zufrieden und ließ ihm ein Paar Kleider im Wert von 1000 Kahāpanā, Schmuckschuhe und 12.000 Kāhāpaṇa geben.

Kommentar:

1 Wasserblase

Abb.: Modell für den Mahāthūpa: Auftreffen eines Wassertropfens auf der Wasseroberfläche

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia]

Abb.: "die einer Bergkristallkugel glich": Wassertropfen, auf Wasseroberfläche zurückprallend

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia]2 Kahāpaṇa: Sanskrit: Karṣāpaṇa: Silbermünze mit ca. 3,3 g reinem Silber. 12.000 Kahāpana = ca. 39,5 kg Silber

15 Iṭṭhakā aharāpessaṃ apīḷento kathaṃ

nare

Iti rājā vicintesi rattiṃ; ñatvāna taṃ marū

16 Cetiyassa catuvāre āharitvāna iṭṭhakā

Rattīṃ rattīṃ ṭhapayiṃsu ekekāhapahonakā.

15. - 16.

In der Nacht grübelte der König, wie der die Ziegel heranbringen lassen könnte ohne das Volk zu bedrücken. Als die Maruts1 das bemerkten, brachten sie Nacht für Nacht Ziegel zu den vier Toren des Cetiya und stapelten sie dort, genauso viel wie für jeweils einen Tag reichten.

Kommentar:

1 Marut: als Sturmgottheiten sind sie für Ziegeltransport besonders geeignet. Ich denke darum, dass Geigers Übersetzung "gods" für Marū hier nicht zutrifft.

"In Hinduism the Maruts, also known as the Marutgana and the Rudras, are storm deities and sons of Rudra and Diti and attendants of Indra. The number of Maruts varies from two to sixty (three times sixty in RV 8.96.8. They are very violent and aggressive, described as armed with golden weapons i.e. lightnings and thunderbolts, as having iron teeth and roaring like lions, as residing in the north, as riding in golden chariots drawn by ruddy horses. According to the Ramayana the Maruts' mother, Diti, either seven or seven times seven in number, hoped to give birth to a son who would be more powerful than Indra. She remained pregnant for one hundred years in hopes of doing so; Indra prevented it by throwing a [[|Vajra|thunderbolt]] at her and splintering the fetus into the many less powerful deities."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maruts. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-17]

Nebenbei bemerkt:

Abb.: Auch ein Marut: indischer Jagdbomber HAL HF-24 Marut

"Die HAL HF-24 Marut ist ein einsitziger Jagdbomber der indischen Luftwaffe. Die Entwicklung der HF-24 begann 1956. Im Auftrag der Regierung leitete Kurt Tank, unterstützt von einer kleinen Gruppe deutscher Fachleute, die Arbeiten an der HF-24. Der Erstflug fand am 17. Juni 1961 statt. Bis 1977 wurden 129 Serienflugzeuge gebaut. Der Typ war bis 1986 im Dienst und wurde 1971 im Krieg gegen Pakistan eingesetzt.

Da Indien kein Triebwerk mit der notwendigen Leistung beschaffen konnte, wurden die Serienmaschinen mit einer Lizenzversion des Strahltriebwerks Rolls-Royce Bristol Orpheus 703, die Hindustan herstellte, ausgerüstet. Deshalb konnte die angestrebte doppelte Schallgeschwindigkeit trotz der guten Konstruktion nie erreicht werden.

Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindustan_Aeronautics_HF_24. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-17]

17 Taṃ sutvā sumano rājā cetiye kammam

ārabhi.

Amūlam ettha kammañ ca na kātabban ti ñāpayi.

17.

Als der König davon hörte begann er wohlgemut die Arbeit am Cetiya. Er ließ verkünden, dass dort nicht ohne Lohn gearbeitet werden darf.1

Kommentar:

1 denn sonst hätte der König nicht das alleinige Verdienst am Bau.

18 Ekekasmiṃ duvārasmiṃ ṭhapāpesi

kahāpaṇe

Soḷasasatasahassāni vatthāni subahūni ca

19 Vividhañ ca alaṅkāraṃ khajjabhojjaṃ sapānakaṃ

Gandhamālaguḷadī ca mukhavāsakapañcakaṃ.

18. - 19.

Bei jedem Tor ließ er 16.000 Kahpaṇa1, sehr viele Kleidungsstücke, verschiedenerlei Schmuck, harte und weiche Speise und Getränke, duftende Blumenkränze, Molassebällchen2 und ähnliches sowie Betelblätter3 mit den fünf atemerfrischenden Zutaten4.

Kommentar:

1 Kahāpaṇa: Sanskrit: Karṣāpaṇa: Silbermünze mit ca. 3,3 g reinem Silber. 16.000 Kahāpana = ca. 53 kg. Silber (an allen vier Toren zusammen: ca. 210 kg. Silber)

2 guḷa = "jaggery" von der Kitulpalme/Toddypalme/Jaggery-Palme (Caryota urens) oder der Palmyrapalme (Borassus flabellifer )

Abb.: guḷa (jaggery)

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia]3 Betelblätter: Piper betel

Abb.: Piper betel

[Bildquelle:s Wikipedia]

Abb.: In Sri Lanka empfängt man Gäste traditionellerweise mit einem Betelblatt

[Bildquelle: sarvodaya.org. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/sarvodaya/6322606/. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung). -- Zugriff am 2006-07-18]

"The Betel (Piper betle) is a spice whose leaves have medicinal properties. The plant is evergreen and perennial, with glossy heart-shaped leaves and white catkins, and grows to a height of about 1 metre. The Betel plant originated in Malaysia and now grows in India, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. The best Betel leaf is the "Magahi" variety (literally from the Magadha region) grown near Patna in Bihar, India. Ingredients

The active ingredients of betel oil, which is obtained from the leaves, are betel-phenol (or chavibetol or 3-hydroxy-4-methoxyalkylbenzene, which gives a smoky aroma), chavicol and cadinene.

ChewingIn India and parts of Southeast Asia, the leaves are chewed together with mineral lime (calcium oxide) and the areca nut [Areca catechu] which, by association, is sometimes inaccurately called the "betel nut". The lime acts to keep the active ingredient in its freebase or alkaline form, thus enabling it to enter the bloodstream via sublingual absorption. The areca nut contains the alkaloid arecoline, which promotes salivation (the saliva is stained red), and is itself a stimulant. This combination, known as a "betel quid", has been used for several thousand years. Tobacco is sometimes added.

Betel leaves are used as a stimulant, an antiseptic and a breath-freshener. In Ayurvedic medicine, they are used as an aphrodisiac. In Malaysia they are used to treat headaches, arthritis and joint pain. In Thailand and China they are used to relieve toothache. In Indonesia they are drunk as an infusion and used as an antibiotic. They are also used in an infusion to cure indigestion, as an ointment or inhalant to cure headache, as a topical cure for constipation, as a decongestant and as an aid to lactation.

In India, they use betel to cast out (cure) worms.

In India, the betel and areca play an important role in Indian culture especially among Hindus. All the traditional ceremonies governing the lives of Hindus use betel and areca. For example to pay money to the priest, they keep money in the betel leaves and place it beside the priest.

The betel and areca also play an important role in Vietnamese culture. In Vietnamese there is a saying that "the betel begins the conversation", referring to the practice of people chewing betel in formal occasions or "to break the ice" in awkward situational conversations. The betel leaves and areca nuts are used ceremonially in traditional Vietnamese weddings. Based on a folk tale about the origins of these plants, the groom traditionally offer the bride's parents betel leaves and areca nuts (among other things) in exchange for the bride. The betel and areca are such important symbols of love and marriage such that in Vietnamese the phrase "matters of betel and areca" (chuyện trầu cau) is synonymous with marriage.

A related plant P. sarmentosum, which is used in cooking, is sometimes called "wild betel leaf"."[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Betel. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-18]

"Their great delight in Betel. But above all things Betel leaves they are most fond of, and greatly delighted in: when they are going to Bed, they first fill their mouths with it, and keep it there until they wake, and then rise and spit it out, and take in more. So that their months are no longer clear of it, than they are eating their Victuals. This is the general practice both of Men and Women, insomuch that they had rather want Victuals or Cloths than be without it; and my long practice in eating it brought me to the same condition. And the Reasons why they thus eat it are, First, Because it is wholsom. Secondly, To keep their mouths perfumed: for being chewed it casts a brave scent. And Thirdly, To make their Teeth black. For they abhor white Teeth, saying, That is like a Dog."

[Quelle: Knox, Robert <1606 - 1681>: An historical relation of the island Ceylon in the East-Indies : together with an account of the detaining in captivity the author and divers other Englishmen now living there, and of the author's miraculous escape. -- London : Richard Chiswell, 1681. -- S. 100. -- Online: http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/14346. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-20]

4 mukhavāsakapañcaka: Vaṃsatthappakāsinī: mukhsodhanatthāya takkolakappūrādikehi pañcahi saṃyuttaṃ tambūlañ ca dāpayi ti attho "Er ließ zur Mundreinigung Betelblätter zusammen mit den fünf (Zutaten) Öl von Luvunga sp., Campher usw. reichen"

"Campher [1,7,7-Trimethyl-bicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-on; C10H16O] ist ein farbloser Feststoff. Es ist ein bicyclisches-Monoterpen-Keton und leitet sich formal vom Camphan ab. Es gibt zwei Enantiomere des Camphers, (+)-Campher und (-)-Campher beziehungsweise d- und l-Campher. Die Struktur wurde von Julius Bredt aufgeklärt. Der Name stammt von dem arabischen Namen Kamfur für die Verbindung ab. Vorkommen

Campher findet sich hauptsächlich in den ätherischen Ölen von Lorbeergewächsen, Korbblütengewächsen und Lippenblütlern. Besonders in der Rinde beziehungsweise im Harz des Campherbaums [Cinnamomum camphora], eines immergrünen Baums, der hauptsächlich in Asien wächst, ist es zu finden. Es kann synthetisch hergestellt werden, aber auch durch Wasserdampfdestillation und Kristallisation aus zerkleinerten Pflanzenteilen gewonnen werden. Natürliche extrahiertes Campher ist immer rechtsdrehend ((+)-Campher). Der natürlich gewonnene Campher wurde früher auch als Japankampfer bezeichnet.EigenschaftenCampher ist ein farbloses oder weißes, meist krümeliges und brockig zähes Pulver aus wachsweichen Kristallen. Mit Ethanol können rhomboedrische Kristalle erzeugt werden. Beim Abschrecken geschmolzenen Camphers bilden sich kubische Kristalle. Es hat einen charakteristischen, starken, wohlriechenden, aromatisch-holzigen, eukalyptusartigen Geruch. Der Geschmack ist scharf und bitter, auch leicht kühlend wie beim Menthol. Es schmilzt bei 177 °C und siedet bei 207 °C. In Wasser ist das Pulver kaum löslich (1,2 g pro Liter Wasser); in Ethanol hingegen löst es sich gut. Außerdem ist es sehr leicht löslich in Petrolether, leicht löslich in Ether, Aceton, Chloroform und in fetten Ölen und sehr schwer löslich in Glycerol. Es bildet mit Ethanol farblose Lösungen, aus denen sich, wenn Wasser hinzugegeben wird, das Campher wieder abscheidet. Die Dichte beträgt 0,96 g/cm³. Campher ist leicht flüchtig und sublimiert schon bei Zimmertemperatur. Campher verbrennt mit rußender Flamme. Der Flammpunkt liegt bei 74 °C, die Zündtemperatur bei 466 °C. Zwischen einem Luftvolumenanteil von 0,6 und 3,5 Prozent bildet es explosive Gemische. Beim Campher tritt das Phänomen der molaren Schmelzpunkterniedrigung auf: Die Gefrierpunkterniedrigung beträgt 39,7 °C·(kg/mol). So verflüssigt sich Campher bereits, wenn es in Kontakt mit Menthol, Naphthol oder Chloralhydrat kommt. Der spezifische Drehwinkel beträgt + 44°.

SicherheitshinweiseEs wirkt auf das Zentrale Nervensystem und die Niere, in höheren Dosen auch auf das Atemzentrum. Campher ist durchblutungsfördernd und schleimlösend. Es führt aber auch zu Übelkeit, Angst, Atemnot und Aufgeregtheit. In Überdosis oral eingenommen kommt es zu Verwirrtheits- und Dämmerzuständen, Depersonalisation, extremen Déjà-vu-Erlebnissen, Panik und akuten tiefgreifenden Störungen des Kurzzeitgedächtnisses bis hin zu Amnesie und epileptischen Anfällen. Die tödliche Dosis für einen Erwachsenen liegt bei circa 20 g. Der Metabolismus geht zunächst über vom Campher abgeleiteten Alkoholen wie dem 2- beziehungsweise 3-Borneol, welche in der Leber zu der Glucosiduronsäure des Borneols, die Metaboliten werden schließlich über den Harn ausgeschieden. Campher ist schwach wassergefährdend (WGK 1).

VerwendungCampher wird in Feuerwerkskörpern und Mottenabwehrmitteln verwendet. In der chemischen Industrie wird es zur Herstellung des Cymols verwendet. Außerdem wird es für die Celluloidproduktion und als Weichmacher für Celluloseester verwendet. In geringen Mengen wird es in Kosmetik- und Medizinpräparaten benutzt, zum Beispiel bei Muskelzerrungen, Rheuma oder Neuralgien, in der Zahnmedizin zur Desinfektion von infizierten Wurzelkanälen; früher wurde es auch als Analeptikum verwendet, heute jedoch seltener wegen der Wirkungen auf das Herz und den Kreislauf. Seltene Fälle der Verwendung von Campher als Rauschmittel sind bekannt. Die Wirkungen beim Inhalieren von Campher zeigen sich in Lachanfällen, trotz Schmerzen in den Atemwegen. Campher findet noch Verwendung in Schnupftabak aus England, wobei aber in Deutschland laut deutschen Lebensmittelgesetz Campher zu den in Tabak verbotenen Stoffen zählt und nicht hinzugefügt werden darf. Auch in Sturmglasbarometern findet es Verwendung.

Gewinnung und DarstellungCampher kann synthetisch hergestellt werden, aber auch durch Wasserdampfdestillation und Kristallisation aus zerkleinerten Pflanzenteilen gewonnen werden. Natürliche extrahiertes Campher ist immer rechtsdrehend ((+)-Campher). Der natürlich gewonnene Campher wurde früher auch als Japankampfer bezeichnet. Heutzutage wird Campher technisch von α-Pinen aus synthetisiert. Hierbei kann je nach Wunsch (+)-Campher oder (-)-Campher gewonnen werden, je nachdem, ob man bei der Synthese (+)-α-Pinen oder (-)-α-Pinen einsetzt, während bei der Destillation aus dem Campherbaum nur (+)-Campher gewonnen werden kann.

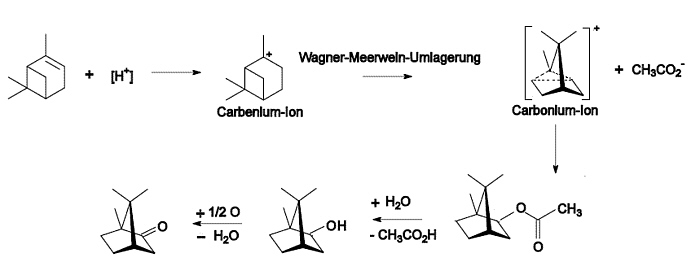

α-Pinen wird protoniert, durch Wagner-Meerwein-Umlagerung wird es zum Carboniumion umgelagert. Dieses reagiert mit Natriumacetat zu Isobornylacetat, dieses wird zum Isoborneol umgewandelt, dies wird mit Oxidationsmittel zum Campher oxidiert."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Campher. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-18]

20 Yathāruci taṃ gaṇhantu kammaṃ katvā

yathāruci

Te tatheva apekkhitvā adaṃsu rājakammikā.

20.

"Wenn sie soviel gearbeitet haben, wie sie wollen, sollen sie davon soviel nehmen, wie sie wollen."1 Gemäß diesem Befehl gaben die königlichen Aufseher aus.

Kommentar:

1 Vgl. "jeder nach seinen Fähigkeiten, jedem nach seinen Bedürfnissen!" (Karl Marx <1818 - 1883>: Kritik des Gothaer Programms, 1875. -- MEW Bd. 19, S. 21)

21 Thūpakamme sahāyattaṃ eko bhikkhu

nikāmayaṃ

Mattikāpiṇḍam ādāya attanā abhisaṅkhataṃ.

22 Gantvāna cetiyaṭṭhānaṃ vañcetvā rājakammike

Adasi taṃ vaḍḍhakissa; gaṇhanto yeva jāni so

23 Tassākāraṃ viditvāna tatthāhosi kutūhalaṃ.

Kamena rājā sutvāna āgato pucchi vaḍḍhakiṃ:

21. -23.

Ein Mönch, der am Bau des Stūpa Anteil haben wollte, nahm ein Klümpchen Lehm, das er selbst zubereitet hatte, ging zum Bauplatz des Cetiya, täuschte die königlichen Aufseher und gab es einem Maurer.1 Kaum hatte dieser das Klümpchen angenommen erkannte er, um was es sich handelte, da er die Art der Herstellung durch den Mönch bemerkte. Es entstand ein Tumult. Als der König nach einiger Zeit davon hörte, kam er und befragte den Maurer.

Kommentar:

1 der Mönch wollte so Mit-Verdienst am Bau des Mahāthūpa erwerben.

24 Deva, ekena hatthena pupphān' ādāya

bhikkhavo

Ekena mattikāpiṇḍaṃ denti mayhaṃ; aham pana

25 Ayaṃ āgantuko bhikkhu ayaṃ nevāsiko iti

Jānāmi devā ti vaco sutvā rājā samappayi

26 Ekaṃ balatthaṃ dassetuṃ mattikādāyakaṃ yatiṃ.

So balatthassa dassesi; so taṃ rañño nivedayi.

24. - 26.

"König, die Mönche halten Blumen in der einen Hand geben mir ein Klümpchen Lehm mit der anderen. Ich weiß nur, ob es ein auswärtiger oder hiesiger Mönch ist, König." Der König ordnete ihm einen Wachsoldaten zu, dem er den Asketen, der den Lehm gegeben hatte, zeigen sollte. Der Maurer zeigte ihn dem Wachsoldaten, dieser meldete es dem König.

27 Jātimakulakumbhe so mahābodhaṅgaṇe

tayo

Ṭhapāpetvā balatthena rājā dāpesi bhikkhuno.

27.

Der König ließ drei Töpfe voll Jasminblüten im Hof des Mahābodhibaums aufstellen und ließ den Aufseher diese dem Mönch zu geben.1

Kommentar:

1 damit hat der Mönch seinen Lohn und nimmt dem König nichts vom Verdienst am Stūpabau weg.

28 Ajānitvā pūjayitvā ṭhitassetassa

bhikkhuno

Balattho taṃ nivedesi; tadā taṃ jāni so yati.

28.

Der Mönch bemerkte nichts und brachte die Jasmintöpfe dar. Da klärte ihn der Wachsoldat auf. Da begriff der Asket.

29 Koṭṭhivāle janapade

Piyaṅgallanivāsiko

Thero cetiyakammasmiṃ sahāyattaṃ nikāmayaṃ

29.

Ein Thera, der in Piyaṅgalla im Koṭṭhivāla-Land wohnte, wollte Anteil am Bau des Cetiya haben.

30 Tass' iṭṭhikāvaḍḍhakissa ñātako

idha āgato

Tatth' iṭṭhikāya mattena ñātvā katvāna iṭṭhakaṃ

31 Kammike vañcayitvāna vaḍḍhakissa adāsi taṃ

So taṃ tattha niyojesi kolāhalam ahosi ca.

30. -31.

Er war ein Verwandter des Baumeisters. Er brachte die Maße der verwendeten Ziegel in Erfahrung und machte einen solchen Ziegel. Er täuschte die Aufseher und gab ihn einem Maurer. Dieser fügte ihn ein. Dann entstand ein Tumult.

32 Rājā sutvā va taṃ āha ñātuṃ sakkā

tam iṭṭhikaṃ,

Jānanto pi na sakkā ti rājānaṃ āha vaḍḍhaki.

32.

Als der König davon erfuhr, fragte er, ob es möglich sei diesen Ziegel zu erkennen. Obwohl er wusste, wo er war, sagte der Maurer dem König, dass es nicht möglich sei.

33 Jānāsi taṃ tvaṃ theraṃ ti vutto amā

ti bhāsi so.

Taṃ ñapanatthaṃ appesi balatthaṃ tassa bhūpati.

33.

Auf die Frage, ob er den Thera kenne, antwortete er mit Ja. Der König ordnete ihm einen Wachsoldaten zu, damit er diesem den Mönch nenne.

34 Balattho tena taṃ ñatvā rājānuññāy'

upāgato

Kaṭṭhahālapariveṇe theraṃ passiya mantiya

34.

Der Wachsoldat erfuhr von ihm, wer der Mönch ist, und ging mit königlicher Erlaubnis zum Thera im Kaṭṭhahāla-Pariveṇa, traf ihn und sprach mit ihm.

35 Therassa gamanāhañ ca gatāṭṭhānañ

ca jāniya

Tumhehi saha gacchāmi sakaṃ gāman ti bhāsiya

35.

Er erfuhr den Tag der Abreise des Thera und sein Reiseziel. Dann sagte er ihm, dass er mit ihm in sein Dorf gehen wolle.

36 Rañño sabbaṃ nivedesi; rājā tassa

adāpayi

Vatthayugaṃ sahassagghaṃ mahagghaṃ rattakambalaṃ

37 Sāmaṇake parikkhāre bahuke sakkharam pi ca

Sugandhatelanāḷiñ ca dāpetvā anusāsi taṃ.

36.

Er meldete dem König alles. Der König ließ ihm ein Paar Kleidung im Wert von 1000 Kahāpaṇa1, ein sehr wertvolles rotes Wolltuch, viele Gebrauchsgegenstände für Asketen, Kristallzucker2, und ein Nāḷi3 Duftöl geben und gab ihm Anweisungen.

Kommentar:

1 Kahāpaṇa: Sanskrit: Karṣāpaṇa: Silbermünze mit ca. 3,3 g reinem Silber. 1000 Kahāpaṇa = ca. 3,3 kg. Silber

2 Kristallzucker: sakkhara, von Zuckerrohr (Saccharum officinarum)

3 Nāḷi: Hohlmaß, 1 Nāḷī = ca. 1,5 Liter

38 Therena saha gantvā so dissante

Piyagallake

Theraṃ sītāya chāyāya sodakāya nisīdiya

39 Sakkharapānakaṃ datvā pāde telena makkhiya

Upāhanāhi yojetvā parikkhāre upānayi;

38. - 39.

Er ging mit dem Thera. Als Piyagallaka in Sicht kam ließ er den Thera an einem kühlen schattigen Platz, wo es Wasser gab, niedersetzen, gab ihm Zuckerwasser, rieb seine Füße mit dem Öl ein, zog ihm die die Sandalen an, und überreichte ihm die Gebrauchsgegenstände.

40 Kulūpakassa therassa gahitā me ime

mayā,

Vatthayugaṃ tu puttassa, sabbaṃ tāni dadāmi vo

40.

"Dies habe ich für den Thera mitgenommen, der regelmäßig meine Familie besucht, die beiden Kleidungsstücke sind für meinen Sohn. Ich übergebe euch alles."

41 Iti vatvāna datvā te gahetvā

gacchato puna

Vanditvā rājavacasā rañño sandesam āha so.

41.

So sprach er und übergab ihm die Sachen. Als der Mönch wieder aufbrach, verabschiedete er sich und berichtete ihm mit den Worten des Königs die Botschaft des Königs.1

Kommentar:

1 dadurch, dass dieser Mönch diese Sachen angenommen hat, hat er das Verdienst für seine Tat und keinen Anteil mehr am Verdienst des Stūpabaus.

42 Mahāthūpe kayiramāne bhatiyā

kammakārakā

Anekasaṅkhā hi janā pasannā sugatiṃ gatā.

42.

Während des Baus des Mahāthūpa sind viele gläubige Lohnarbeiter in einer guten Existenzform wiedergeboren worde.

43 Cittappasādamattena sugate gati

uttamā

Labbhatīti viditvāna thūpapūjaṃ kare budho.

43.

Ein weiser Mensch verehrt den Stūpa, da er weiß, dass nur durch ein an den Buddha gläubiges Herz die höchste Existenzform bei der Wiedergeburt erreicht wird.

44 Ettheva bhatiyā kammaṃ karitvā

itthiyo duve

Tāvatiṃsamhi nibbattā ṃahathūpamhi niṭṭhite

45 Āvajjitvā pubbakammaṃ diṭṭhakammaphalā ubho

Gandhamālādiyitvāna thūpaṃ pūjetum āgatā;

44.

Zwei Frauen, die dort für Lohn gearbeitet hatten, sind in Tāvatiṃsa1 wiedergeboren worden. Als der Mahāthūpa fertig war, dachten sie über ihre früheren Taten nach und sahen die Frucht dieser Taten. Da kamen sie mit duftenden Blumenkränzen, um der Stūpa zu verehren.

Kommentar:

1 Tāvatiṃsa

Abb.: Tāvatiṃsa. -- Leporello, Myanmar, 18. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/world/world-object.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]

"Tāvatiṃsa The second of the six deva-worlds, the first being the Cātummahārājika world. Tāvatimsa stands at the top of Mount Sineru (or Sudassana). Sakka is king of both worlds, but lives in Tāvatimsa. Originally it was the abode of the Asuras; but when Māgha was born as Sakka and dwelt with his companions in Tāvatimsa he disliked the idea of sharing his realm with the Asuras, and, having made them intoxicated, he hurled them down to the foot of Sineru, where the Asurabhavana was later established.

The chief difference between these two worlds seems to have been that the Pāricchattaka tree grew in Tāvatimsa, and the Cittapātali tree in Asurabhavana. In order that the Asuras should not enter Tāvatimsa, Sakka had five walls built around it, and these were guarded by Nāgas, Supannas, Kumbhandas, Yakkhas and Cātummahārājika devas (J.i.201ff; also DhA.i.272f). The entrance to Tāvatimsa was by way of the Cittakūtadvārakotthaka, on either side of which statues of Indra (Indapatimā) kept guard (J.vi.97). The whole kingdom was ten thousand leagues in extent (DhA.i.273), and contained more than one thousand pāsādas (J.vi.279). The chief features of Tāvatimsa were its parks - the Phārusaka, Cittalatā, Missaka and Nandana - the Vejayantapāsāda, the Pāricchatta tree, the elephant-king Erāvana and the Assembly-hall Sudhammā (J.vi.278; MA.i.183; cp. Mtu.i.32). Mention is also made of a park called Nandā (J.i.204). Besides the Pāricchataka (or Pārijāta) flower, which is described as a Kovilāra (A.iv.117), the divine Kakkāru flower also grew in Tāvatimsa (J.iii.87). In the Cittalatāvana grows the āsāvatī creeper, which blossoms once in a thousand years (J.iii.250f).

It is the custom of all Buddhas to spend the vassa following the performance of the Yamakapātihāriya, in Tāvatimsa. Gotama Buddha went there to preach the Abhidhamma to his mother, born there as a devaputta. The distance of sixty-eight thousand leagues from the earth to Tāvatimsa he covered in three strides, placing his foot once on Yugandhara and again on Sineru.

The Buddha spent three months in Tāvatimsa, preaching all the time, seated on Sakka's throne, the Pandukambalasilāsana, at the foot of the Pāricchattaka tree. Eighty crores of devas attained to a knowledge of the truth. This was in the seventh year after his Enlightenment (J.iv.265; DhA.iii.216f; BuA. p.3). It seems to have been the frequent custom of ascetics, possessed of iddhi-power, to spend the afternoon in Tāvatimsa (E.g., Nārada, J.vi.392; and Kāladevala, J.i.54).

Moggallāna paid numerous visits to Tāvatimsa, where he learnt from those dwelling there stories of their past deeds, that he might repeat them to men on earth for their edification (VvA. p.4).

The Jātaka Commentary mentions several human beings who were invited by Sakka, and who were conveyed to Tāvatimsa - e.g. Nimi, Guttila, Mandhātā and the queen Sīlavatī. Mandhātā reigned as co-ruler of Tāvatimsa during the life period of thirty-six Sakkas, sixty thousand years (J.ii.312). The inhabitants of Tāvatimsa are thirty-three in number, and they regularly meet in the Sudhammā Hall. (See Sudhammā for details). A description of such an assembly is found in the Janavasabha Sutta. The Cātummahārājika Devas (q.v.) are present to act as guards. Inhabitants of other deva- and brahma-worlds seemed sometimes to have been present as guests - e.g. the Brahmā Sanankumāra, who came in the guise of Pañcasikha. From the description given in the sutta, all the inhabitants of Tāvatimsa seem to have been followers of the Buddha, deeply devoted to his teachings (D.ii.207ff). Their chief place of offering was the Cūlāmanicetiya, in which Sakka deposited the hair of Prince Siddhattha, cut off by him when he renounced the world and put on the garments of a recluse on the banks of the Nerañjarā (J.i.65). Later, Sakka deposited here also the eye-tooth of the Buddha, which Doha hid in his turban, hoping to keep it for himself (DA.ii.609; Bu.xxviii.6, 10).

The gods of Tāvatimsa sometimes come to earth to take part in human festivities (J.iii.87). Thus Sakka, Vissakamma and Mātali are mentioned as having visited the earth on various occasions. Mention is also made of goddesses from Tāvatimsa coming to bathe in the Anotatta and then spending the rest of the day on the Manosilātala (J.v.392).

The capital city of Tāvatimsa was Masakkasāra (Ibid., p.400). The average age of an inhabitant of Tāvatimsa is thirty million years, reckoned by human computation. Each day in Tāvatimsa is equal in time to one hundred years on earth (DhA.i.364). The gods of Tāvatimsa are most handsome; the Licchavis, among earth-dwellers, are compared to them (DhA.iii.280). The stature of some of the Tāvatimsa dwellers is three-quarters of a league; their undergarment is a robe of twelve leagues and their upper garment also a robe of twelve leagues. They live in mansions of gold, thirty leagues in extent (Ibid., p.8). The Commentaries (E.g., SA.i.23; AA.i.377) say that Tāvatimsa was named after Magha and his thirty-two companions, who were born there as a result of their good deeds in Macalagāma. Whether the number of the chief inhabitants of this world always remained at thirty-three, it is impossible to say, though some passages, e.g. in the Janavasabha Sutta, lead us to suppose so.

Sometimes, as in the case of Nandiya, who built the great monastery at Isipatana, a mansion would appear in Tāvatimsa, when an earth-dweller did a good deed capable of obtaining for him birth in this deva-world; but this mansion would remain unoccupied till his human life came to an end (DhA.iii.291). There were evidently no female devas among the Thirty-three. Both Māyā and Gopikā (q.v.) became devaputtas when born in Tāvatimsa. The women there were probably the attendants of the devas. (But see, e.g., Jālini and the various stories of VvA).

There were many others besides the Thirty-three who had their abode in Tāvatimsa. Each deva had numerous retinues of attendants, and the dove-footed (kaktgapādiniyo) nymphs (accharā) of Tāvatimsa are famous in literature for their delicate beauty. The sight of these made Nanda, when escorted by the Buddha to Tāvatimsa, renounce his love for Janapadakalyānī Nandā (J.ii.92; Ud.iii.2).

The people of Jambudīpa excelled the devas of Tāvatimsa in courage, mindfulness and piety (A.iv.396). Among the great achievements of Asadisakumāra was the shooting of an arrow as far as Tāvatimsa (J.ii.89).

Tāvatimsa was also known as Tidasa and Tidiva (q.v.)."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

46 Gandhamālāhi pūjetvā cetiyaṃ

abhivandisuṃ

Tasmiṃ khaṇe Bhātivaṅkavāsi thero Mahāsivo

47a Rattibhage Mahāthūpaṃ vandissāmīti āgato

46. - 47a.

Sie brachten die duftenden Blumenkränze dar und verehrten das Cetiya. In diesem Augenblick kam der Thera Mahāsiva, der in Bhātivaṅka wohnte, um in der Nacht den Mahāthūpa zu verehren.

47b Tā disvāna mahāsattapaṇṇarukkham

upassito

48 Adassayitvā attānaṃ passaṃ sampattim abbhutaṃ

Ṭhatvā tāsaṃ vandanāya pariyosāne apucchi tā:

47b. -48.

Er stand unter einem großen indischen Devil-Baum1 und sah die beiden Frauen, ohne sich selbst ihnen zu zeigen. Er stand da und betrachtete ihre wunderbare Vollkommenheit. Als sie mit ihrer Verehrung fertig waren, fragte er sie:

Kommentar:

1 indischer Devil-Baum: Alstonia scholaris

Abb.: sattapaṇṇa = Siebenblatt = Alstonia scholaris

[Bildquelle: http://www.nparks.gov.sg/nursery/spe_by_search_details.asp?specode=6887&searchdetail=detail. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]

Abb.: Alstonia scholaris

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"Alstonia is a widespread genus of evergreen trees and shrubs from the dogbane family (Apocynaceae). It was named by Robert Brown in 1811, after Charles Alston (1685-1760), Professor of botany at Edinburgh from 1716-1760. The type species Alstonia scholaris (L.) R.Br. was originally named Echites scholaris by Linnaeus in 1767.

DescriptionAlstonia (devil tree) consists of about 40-60 species (according to different authors), native to tropical and subtropical Africa, Central America, southeast Asia, Polynesia and New South Wales, Queensland and North Australia, with most species in the Malesian region.

These trees can grow very large, such as the Alstonia pneumatophora, recorded with a height of 60 m and a diameter of more than 2 m. Alstonia longifolia is the only species growing in Central America (mainly shrubs, but also trees 20 m high).

The leathery, sessile, simple leaves are elliptical, ovate, linear or lanceolate and wedge-shaped at the base. The leaf blade is dorsiventral, medium-sized to large and disposed oppositely or in a whorl and with entire margin. The leaf venation is pinnate, with numerous veins ending in a marginal vein.

The inflorescence is terminal or axillary, consisting of thyrsiform cymes or compound umbels. The small, more or less fragrant flowers are white, yellow, pink or green and funnel-shaped, growing on a pedicel and subtended by bracts. They consist of 5 petals and 5 sepals, arranged in four whorls. The fertile flowers are hermaphrodite. The gamosepalous green sepals consist of ovate lobes, and are distributed in one whorl. The annular disk is hypogynous. The five gamesepalous petals have oblong or ovate lobes and are disposed in one whorl. The corolla lobes overlapping to the left (such as A. rostrata) or to the right (such as A. macrophylla) in the bud. The ovary has 2 separate follicles with glabrous or ciliate, oblong seeds that develop into deep blue podlike, schizocarp fruit, between 7-40 cm long. The plants contain a milky sap, rich in poisonous alkaloids. The Alstonia macrophylla is commonly known in Sri Lanka as 'Havari nuga' or the 'wig banyan' because of its distinct flower that looks like a woman's long wig.Alstonia trees are used in traditional medicine. The bark of the Alstonia constricta and the Alstonia scholaris is a source of a remedy against malaria, toothache, rheumatism and snake bites. The latex is used in treating coughs, throat sores and fever.

Many Alstonia species are commercial timbers, called pule or pulai in Indonesia and Malaysia. Trees from the section Alstonia produce light timber, while those from the sections Monuraspermum and Dissuraspermum produce heavy timber.

Alstonia trees are widespread and mostly not endangered. However a few species are very rare, such as A. annamensis, A. beatricis, A. breviloba, A. stenophylla and A. guangxiensis."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alstonia. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]

49 Bhāsate sakalo dīpo dehobhāsena vo

idha,

Kin nu kammaṃ karitvana devalokaṃ ito gatā

49.

"Die ganze Welt erstrahlt vom Glanz eurer Körper. Welche Tat habt ihr vollbracht, dass ihr von hier in die Welt der Götter gekomen seid?"

50 Mahāthūpe kataṃ kammaṃ tassa āhaṃsu

devatā.

Evaṃ tathāgate yeva pasādo hi mahapphalo.

50.

Die Gottheiten erzählten ihm von ihrer Arbeit am Mahāthūpa. So trägt der Glaube an den Wahrheitsfinder große Frucht.

51 Pupphadhānattayaṃ thūpe iṭṭhikāhi

citaṃ citaṃ

Samaṃ paṭhaviyā katvā iddhimanto 'vasādayuṃ.

51.

Wundermächtige ließen die drei Terrassen1 für Blumen versinken, sobald sie mit Ziegeln ausgelegt waren, und machten sie dem Erdboden gleich.

Kommentar:

1 vermutlich der so genannte pāsāda (a,b,c im Bild unten)

Abb.: Die drei Terrassen für Blumen[Bildquelle: Geiger, Wilhelm <1856 - 1943>: Culture of Ceylon in mediaeval times / Ed. by Heinz Bechert. -- Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 1960. -- XIX, 286 S. ; 25 cm. -- S. 220]

52 Navavāre citaṃ evaṃ evaṃ osādayiṃsu

te.

Atha rājā bhikkhusaṅghasannipatam akārayi;

52.

Neunmal ließen sie so das eben Aufgeschichtete versinken. Da ließ der König die Mönchsgemeinde zusammenkommen,

53 Tatthāsīti sahassānī sannipātamhi

bhikkhavo;

Rājā saṅgham upāgamma pūjetvā abhivandiya

54a Iṭṭhakosīdane hetuṃ pucchi; saṅgho viyākari:

53. - 54a.

80.000 Mönche waren bei der Zusammenkunft. Der König kam zur Mönchsgemeinde, begrüßte sie und fragte nach dem Grund der Senkung der Ziegel. Die Mönchsgemeinde erklärte ihm:

54b Nosīdanatthaṃ thūpassa

iddhimantehi bhikkhuhi

55 Kataṃ etaṃ mahārāja, na idāni karissare;

Aññathattam akatvā tvaṃ mahāthūpaṃ samāpaya.

54b - 55.

"Großkönig!, Wundermächtige Mönche haben das getan, damit der Stūpa sich nicht senkt. Jetzt ewerden sie es nicht mehr tun. Ändere nichts und vollenden den Mahāthūpa!"

56 Taṃ sutvā sumano rājā thūpe kammam

akārayi.

Pupphādhānesu dasasu iṭṭhakā dasakoṭiyo.

56.

Als der König das hörte, war er froh und ließ die Arbeit am Stūpa fortführen. Für die zehn1 (Dreierreihen von) Blumenterassen brauchte man 100.000.0002 Ziegel.

Kommentar:

1 nämlich die neun versunkenen und die eine oberirdische

2 10 Koṭi = 10x107 = 100 Millionen

57 Bhikkhusaṅgho sāmaṇere Uttaraṃ

Sumanam pi ca

Cetiyadhātugabbhatthaṃ pāsāṇe medavaṇṇake

58 Āharathā ti yojesuṃ, te gantvā Uttaraṃ Kuruṃ

Asītiratanāyāmavitthāre ravibhāsure

59 Aṭṭhaṅgulāni bahule gaṇṭhipupphanibhe subhe

Cha medavaṇṇapāsāṇe āhariṃsu ghaṇe tato.

57. - 59.

Die Mönchsgemeinde beauftragte die Novizen Uttara und Sumana, für die Reliquienkammer des Cetiya Specksteine1 zu holen. Sie gingen zu den nördlichen Kuru2 und brachten von dort sechs massive Specksteine. Diese waren 80 Ellen3 lang und breit, acht Fingerbreit dick, glänzten wie die Sonne und waren schön wie Pentapetes phoenicea-Blumen4.

Kommentar:

1 Specksteine

"Speckstein (Talkschiefer, Steatit) ist ein Magnesium-Silikat (Mg3Si4O10(OH)2), das fast weltweit abgebaut wird. Die Steine unterscheiden sich regional in ihrer Härte und Brüchigkeit. Mit dem Begriff Speckstein bezeichnet man eine Gruppe von Natursteinen, die je nach ihrer geographischen Herkunft sehr verschiedenartig zusammengesetzt sein können. Hauptbestandteile sind im allgemeinen die Mineralien Talk, Chlorit, Magnesit und Serpentin.

VorkommenÄgypten, Brasilien, China, Frankreich, Finnland, Indien, Italien, Kanada, Norwegen, Österreich (größte Talk-Lagerstätte Mitteleuropas), Russland, Ukraine, Südafrika. In Deutschland wurde Speckstein bis vor wenigen Jahren in der Johanneszeche (bei Wunsiedel in Oberfranken) abgebaut.

Wird auch Lavez (ital.: pietra ollare; franz.: pierre ollaire; engl.: soapstone) genannt, vor allem in der Schweiz und im Veltlin.

Die mittelalterliche Bezeichnung lautete für diesen Stein Talcus.

VerwendungIndustrie

In der Industrie als Talkum, Verwendung in der Glas-, Farben- und Papierindustrie, Schmiermittel, Grundstoff für Kosmetika, Babypuder, Körperpuder, Lebensmittelindustrie sowie in der Kunststoff-, Keramik-, Porzellan- und Autoindustrie.Kunst

In der Bildhauerei sowie für die Herstellung von Skulpturen werden die kompakten, farbigen Steine bevorzugt. Sie sind leicht bearbeitbar und gut polierbar.Handwerk

Aus finnischem Speckstein werden bevorzugt so genannten Specksteinöfen gefertigt, die sich durch eine außerordentlich lange Wärmespeicherfähigkeit auszeichnen. Diese Specksteine sind aber viel härter und nicht zum plastischen Gestalten geeignet. Wegen der Wärmebeständigkeit wird Speckstein seit der Antike auch für Kochgeschirr verwendet. Die Hethiter verwendeten Speckstein für die Herstellung von Rollsiegeln.Eigenschaften

Physikalische EigenschaftenHärtegrad: 1 (nach der Mohs´schen Härteskala)

Dichte: 2,75 kg/dm³

Farbenweiß, violett, rosa, grün, grau, schwarz, braun

ZusammensetzungReiner Speckstein besteht bis zu 100 % aus Talk und ist einfach mit dem Fingernagel ritzbar. Varietäten haben Talk 40–50 %, Magnesit 40–50 %, Penninit 5–8 % (finnischer Speckstein) und ist nicht mehr mit dem Fingernagel ritzbar.

GefahrenIn Speckstein sollen Asbestfasern enthalten sein. Im allgemeinen sind Talklagerstätten karbonatischer Herkunft asbestfrei. Serpentinitische Lagerstätten könnten Asbest beinhalten, diese werden aber weltweit nicht mehr abgebaut. Im finnischen Ofenspeckstein, im Speckstein zum plastischen Gestalten und in den Produkten für die Industrie sind deshalb nachgewiesenermaßen keine Asbestfasern enthalten."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speckstein. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]

2 Elle (hattha): die Länge vom Ellbogen bis zur Spitze des Mittelfingers, oft = 24 aṅgula, d.h. ca. 45 cm. Die Steine hätten also eine Größe von ca. 36 m x 36 m x 15 cm.

3 nördlichen Kuru

"Uttarakuru A country often mentioned in the Nikāyas and in later literature as a mythical region. A detailed description of it is given in the Ātānātiya Sutta. (D.iii.199ff; here Uttarakuru is spoken of as a city, pura; see also Uttarakuru in Hopkins: Epic Mythology, especially p.186). The men who live there own no property nor have they wives of their own; they do not have to work for their living. The corn ripens by itself and sweet-scented rice is found boiling on hot oven-stoves. The inhabitants go about riding on cows, on men and women, on maids and youths. Their king rides on an elephant, on a horse, on celestial cars and in state palanquins. Their cities are built in the air, and among those mentioned are ātānātā, Kusinātā, Nātapuriyā, Parakusinātā, Kapīvanta, Janogha, Navanavatiya, Ambara-Ambaravatiya and Ālakamandā, the last being the chief city.

The king of Uttarakuru is Kuvera, also called Vessavana, because the name of his citadel (? rājadhāni) is Visāna. His proclamations are made known by Tatolā, Tattalā, Tatotalā, Ojasi, Tejasi, Tetojasi, Sūra, Rāja, Arittha and Nemi. Mention is also made of a lake named Dharanī and a hall named Bhagalavati where the Yakkhas, as the inhabitants of Uttarakuru are called, hold their assemblies.

The country is always spoken of as being to the north of Jambudīpa. It is eight thousand leagues in extent and is surrounded by the sea (DA.ii.623; BuA.113). Sometimes it is spoken of (E.g., A.i.227; v.59; SnA.ii.443) as one of the four Mahādīpā - the others being Aparagoyāna, Pubbavideha and Jambudīpa - each being surrounded by five hundred minor islands. These four make up a Cakkavāla, with Mount Meru in their midst, a flat-world system. A cakkavattī's rule extends over all these four continents (D.ii.173; DA.ii.623) and his chief queen comes either from the race of King Madda or from Uttarakuru; in the latter case she appears before him of her own accord, urged on by her good fortune (DA.ii.626; KhA.173).

The trees in Uttarakuru bear perpetual fruit and foliage, and it also possesses a Kapparukkha which lasts for a whole kappa (A.i.264; MA.ii.948). There are no houses in Uttarakuru, the inhabitants sleep on the earth and are called, therefore, bhūmisayā (ThagA.ii.187-8).

The men of Uttarakuru surpass even the gods of Tāvatimsa in four things:

- they have no greed (amamā) (the people of Uttarakuru are acchandikā, VibhA.461),

- no private property (apariggahā),

- they have a definite term of life (niyatāyukā) (one thousand years, after which they are born in heaven, says Buddhaghosa, AA.ii.806)

- and they possess great elegance (visesabhuno).

They are, however, inferior to the men of Jambudīpa in courage, mindfulness and in the religious life (A.iv.396; Kvu.99).

Several instances are given of the Buddha having gone to Uttarakuru for alms. Having obtained his food there, he would go to the Anotatta lake, bathe in its waters and, after the meal, spend the afternoon on its banks (See, e.g., Vin.i.27-8; DhsA.16; DhA.iii.222). The power of going to Uttarakuru for alms is not restricted to the Buddha; Pacceka Buddhas and various ascetics are mentioned as having visited Uttarakuru on their begging rounds (See, e.g., J.v.316; vi.100; MA.i.340; SnA.ii.420). It is considered a mark of great iddhi-power to be able to do this (E.g., Rohita, SA.i.93; also Mil.84).

Jotika's wife was a woman of Uttarakuru; she was brought to Jotika by the gods. She brought with her a single pint pot of rice and three crystals. The rice-pot was never exhausted; whenever a meal was desired, the rice was put in a boiler and the boiler set over the crystals; the heat of the crystals went out as soon as the rice was cooked. The same thing happened with curries (DhA.iv.209ff). Food never ran short in Uttarakuru; once when there was a famine in Verañjā and the Buddha and his monks were finding it difficult to get alms, we find Moggallāna suggesting that they should go to Uttarakuru for alms (Vin.iii.7). The clothes worn by the inhabitants resembled divine robes (See, e.g., PvA.76).

It was natural for the men of Uttarakuru not to transgress virtue, they had pakati-sīla (Vsm.i.15).

Uttarakuru is probably identical with the Kuru country mentioned in the Rg-Veda (See Vedic Index)."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

"Geographical Location of Uttarakuru Though the later texts mix up the facts with the fancies on Uttarakurus, yet in the earlier, and some of the later texts, Uttarakurus indeed appear to be historical people. Hence scholars have attempted to identfy the actual location of Uttarakuru.

Puranic accounts always locate the Uttarakuru varsa in the northern parts of Jambudvipa.

The Uttarakuru is taken by some as identical with the Kuru country mentioned in the Rg-Veda The Kurus and Krivis (Panchala) are said to form the Vaikarana of Rigveda and the Vaikarana is often identified with Kashmir. Therefore, Dr Zimmer [Heinrich Zimmer, 1841 - 1910] likes to identify the Vaikarana Kurus with the Uttarakurus and place them in Kashmir [कश्मीर, کشمیر].

Dr Macdonnel and Dr Keith accept the above location by Zimmer.

Dr Michael Witzel locates his Uttarakuru in Uttaranchal Pradesh [उत्तरांचल].

According to some scholars, the above locations however do not seem to be correct since they go against Aitareya Brahmana evidence which clearly states that Uttarakuru and Uttaramadra lied beyond Himalaya (pren himvantam janapada Uttarakurva Uttaramadra).

Moreover, no notice of the Uttaramadras (Bahlika, Bactria) has been taken of while fixing up the above location of Uttarakuru. Uttarakurus and Uttaramadras are stated to be immediate neighbors in the Trans-Himalaya region per Aitareya Brahmana evidence (VIII/14).

Dr M. R. Singh's views

Ramayana testifies that the original home of the Kurus was in Bahli country. Ila, son of Parajapati Karddama was a king of Bahli, where Bahli represents Sanskrit Bahlika (Bactria). Also the kings from Aila lineage have been called Karddameyas. The Aila is also stated to be the lineage of the Kurus themselves (Ramayana , Uttarakanda, 89.3-23). The Karddamas obtained their name from river Karddama in Persia/ancient Iran. Moreover, Sathapatha Brahmana attests a king named Bahlika Pratipeya as of the Kauravya lineage. Bahlika Pratipeya, as the name implies, was a prince of Bahlika (Bactria). Thus, the Bahli, Bahlika was the original home of the Kurus.Thus Bahlika or Bactria may have constituted the Uttarakuru.

Mahabharata and Sumangalavilasini also note that the people of Kuru had originally migrated from Uttarakutru.

Bactria is evidently beyond the Hindukush i.e Himalaya. In ancient literature, Himalaya is said to be extending from eastern occean to western occean and even today is not separated from it (Kumarasambhavam, I, 1).

The above identifiaction of Uttarakuru comes from Dr M. R. Singh (Geographiacl Data in Early Puranas, 1972, pp 63-65).

Dr K. P. Jayswal's views

Dr K. P. Jayswal identifies Mt Meru of the Puranas with Hindukush ranges and locates the Uttakuru in the Pamirs itself (Hindu Polity, 1978, p 124, 138-39).

Dr Aggarwal's and Dr Kamboj's viewsDr Aggarwala thinks that the Uttarakuru was located to north of Pamirs in Central Asia and was also famous for its horses of Tittirakalamasha variety. (India as Known to Panini, p 61). Thus it probably comprised parts of Kirgizstan [Кыргызстан] and Tian-Shan [天山9. Incidentally, the reference to horses from Uttarakuru rules out any possibility of locating Uttarakurus in Kashmir and Uttaranchal Pradesh since these regions have never been noted for their horses.

Bhishamaparava of Mahabharata attests that the country of Uttarakuru lied to the north of Mt Meru and to the south of Nila Parvata.

- dakshinena tu nilasya meroh parshve tathottare. /

- uttarah Kuravo rajanpunyah siddhanishevitah. //2

- — (MBH 6/7/2)

The Mt Meru of Hindu traditions is identified with the knot of Pamirs. Mountain Nila may have been the Altai-Mt.

The Mahabharata refers to the Kichaka bamboos growing on the banks of river Shailoda (MBH, II, 48-2).

Mahabharata further attests that the Kichaka bamboo region was situated between Mountain Meru (Pamirs) and Mountain Mandara (Alta Tag).

The river valleys between these two mountains are still overgrown with forests of Kichaka Bamboos.

Ramayana also attests that the valleys of river Shailoda were overgrown with Kichhaka bamboos and the country of Uttarakuru lied beyond river Shailoda as well as the valleys of Kichaka bamboos.River Shailoda of Ramayana (4.43.37-38) and Mahabharata (MBH II.48.2-4) has been variously identified with river Khotan, Yarkand, and Syr (Jaxartes) by different scholars.

Raghuvamsa (4.73) also refers to the Kichaka bamboos of Central Asia in the eastern regions of the Pamirs or Meru mountains which were known as Dirghavenu in Sanskrit.The above discussion shows that the land of Uttarakurus was located north of river Shailoda as well as of Kichaka bamboo valleys.

Rajatrangini places Uttarkuru land in the neighborhood of Strirajya. Based on Yuan Chwang's [玄奘] evidence (I, p 330), Strirajya is identified as a country lying north of Kashmir, south of Khotan and west of Tibet.Thus, the Uttarakuru which finds reference in the Ramayana, Mahabharata and Rajatrangini probably can not be identified with the Bahlika or Bactria as Dr M. R. Singh has concluded.

Uttarakuru probably comprised north-west of Sinkiang [شىنجاڭ ; 新疆] province of China and parts of the Tian-Shan .One line of scholars locate Uttarakuru in the Tarim Basin.

Dr Christian Lassen [1800 - 1876] suggests that the Ottorokoroi of Ptolemy should be located in the east of Kashgar [ قەشقەر喀什] i.e in Tarim Basin (Quoted in Original Sanskrit Texts, by J Muir).Some writers assert that Uttarakuru was the name for the vast area lying north of Himalaya and extending as far as Arctic circle.

MiscellaneousSome scholars tend to identify the Uttarakurus and the Uttaramadras with the Tocharian (Uttarakuru = Tokhri) branch of Indo-Europeans located to the north of the Himalayas

Tokhari or Tukharas, the later Yucchis, are the same as the Rishikas of Mahabharata. The epic attests the Rishikas and the Parama-Kambojas as very close neighbors (II.27.25-26). In eighth century war compaign of king Lalitaditya of Kashmir (Rajatrangini: 4/164-165), the Tukharas (Tusharas) and the Kambojas are again attested as very close neighbors located almost in the same epic location in Central Asia. At another place in Mahabharata, the Rishikas are stated to be a sub-section of the Kambojas (Prof Ishwa Misra):

- Shakanam Pahlavana.n cha Daradanam cha ye nripah./

- Kamboja RishikA ye cha pashchim.anupakashcha ye 15.//

- — (MBH 5/4/15)

- Translation (by Prof Ishwa Mishra)

These kings of the Shakas, Pahlavas and Daradas, these are Kaamboja Rshikas and these are in the western riverine area.

It is possible that the Tocharians and Parama Kambojans formed parts of Uttarakuru."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uttarakuru. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]

4 Pentapetes phoenicea

Abb.: Pentapetes phoenicea

[Bildquelle: Alex Robinson. -- http://www.csdl.tamu.edu/FLORA/cgi/gallery_query?q=tamu+campus. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]Pentapetes phoenicea ist in Süd- und Südostasien von Indien bis zu den Philippinen und der Nordküste Australiens heimisch.

60 Pupphādhānassa upari majjhe ekaṃ

nipātiya

Catupassamhi caturo mañjusaṃ viya yojiya

61 Ekaṃ pidahanatthāya disābhāge puratthime

Adassanaṃ karitvā te ṭhapayiṃsu mahiddhikā.

60.

Die Wundermächtigen legten einen auf die Mitte der Blumenterrasse, vier stellten sie an seine vier Seiten wie eine Kiste miteinander verbunden1; einen, der als Deckel dienen sollte, stellten sie in den Osten, nachdem sie ihn unsichtbar gemacht hatten.

Kommentar:

1 Die Anordnung hat man sich so vorzustellen (Zeichnung nicht maßstabgetreu!):

Abb.: Vermutliche Anordnung der Steine der Reliquienkammer (nicht Maßstabgetreu!)

62 Majjhamhi dhātugabbhassa tassa rājā

akārayi

Ratanamayaṃ bodhirukkhaṃ sabbākāramanoramaṃ.

62.

In der Mitte dieser Reliquienkammer ließ der König einen Bodhibaum1 aus Edelsteinen bilden, der in jeder Hinsicht herzerfreuend war.

Kommentar:

1 Ficus religiosa

63 Aṭṭhārasarataniko khandho sākhāssa

pañca ca,

Pavāḷamayamūlo so indanīle patiṭṭhito.

63.

Der Stamm war 18 Ellen1 (ratana) hoch und er hatte fünf Zweige. Er hatte Wurzeln aus Koralle und stand auf einem Saphir2.

Kommentar:

1 Elle (ratana): die Länge vom Ellbogen bis zur Spitze des Mittelfingers, oft = 24 aṅgula, d.h. ca. 45 cm. 18 Ellen = ca. 8 m.

2 Saphir besteht aus monokristallinem Al2O3 sowie je nach Farbe Verunreinigungen mit Fe2+-, Fe3+-, Cr3+-, Ti4+- und/oder V4+-Ionen.

Abb.: "Star of India", der größte bekannte Saphir (563,35 Karat = 112,67 g), gefunden in Sri Lanka um 1900

[Bildquelle: Glitch010101. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/ericskiff/109777499/. -- Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung). -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]

64 Susuddharajatakkhandho maṇipattehi

sobhito,

Hemamayapaṇḍupattaphalo pavāḷaaṅkuro.

64.

Er hatte einen Stamm aus ganz reinem Silber, Blätter aus Edelsteinen, gelbliche Blätter und Früchte aus Gold und Schösslinge aus Koralle.

65 Aṭṭha maṅgalikān' assa khandhe

pupphalatā pi ca

Catuppadānaṃ pantī ca haṃsapantī ca sobhanā

65.

Auf seinem Stamm waren die acht Glücksymbole1, Blütenranken, schöne Reihen von Vierfüßlern2 und von Gänsen3.

Kommentar:

1 acht Glückssymbole:

- mṛdaṅga - Trommel

- vṛṣabha - Stier

- nāga - Kobra

- vījanī - Fächer

- keśarī - Löwe

- makara - Makara

- patāka - Flagge

- pradīpa - Lampe

Es gibt auch andere Aufzählungen.

Es könnte sich auch um das Acht-Glückssymbols-Yantra (Singhalesisch: Aṭamagala) handeln:

Abb.: Aṭa-magala[Quelle der Abb. und der Aufzählung: Coomaraswamy, Ananda K. (Kentish) <1977 - 1947>: Mediaeval Sinhalese art : being a monograph on mediaeval Sinhalese arts and crafts, mainly as surviving in the eighteenth century, with an account of the structure of society and the status of the craftsmen. -- 2d ed. [rev.] incorporating the author’s corrections. -- New York : Pantheon Books, 1956. -- XVI, 344 S. : Ill. -- 29 cm. -- S. 272]

2 Reihen von Vierfüßlern und Gänsen

Abb.: "Reihen von Vierfüßlern und Gänsen": Mondstein, Polonnaruwa, ca. 12. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: Jungle Boy. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/jungle_boy/145079598/. -- Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung). -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]

3 Gänse (haṃsa): Streifengans (Anser indicus)

Abb.: Haṃsa - Streifengans - Anser indicus

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"Die Streifengans (Anser indicus) oder Indische Gans ist eine in Zentral- und Südasien einheimische Art der Feldgänse (Anser) und gehört zu den echten Gänsen (Anserini). Sie wird gelegentlich zusammen mit ihren nächsten Verwandten, der Kaisergans (Anser canagica), der Schneegans (Anser caerulescens) und der Zwergschneegans (Anser rossii) in eine eigene Gattung mit dem wissenschaftlichen Namen Chen gestellt. Die Art wurde im Jahre 1790 durch John Latham in seinem in London erschienenen Werk Index orntihologicus erstbeschrieben. Aussehen

Die Streifengans ist mit einer Länge von ungefähr 70 bis 75 cm etwa so groß wie die in Mitteleuropa vertrautere Graugans (Anser anser); ihre Flügellänge liegt zwischen 40 und 50 cm, das Gewicht bei etwa zwei bis drei Kilogramm. Das Weibchen ist meistens etwas kleiner als das Männchen, unterscheidet sich ansonsten von diesem aber nicht. Das Erkennungsmerkmal der Streifengans sind zwei namensgebende schwarzbraune Querstreifen: Der erste läuft bogenförmig vom linken Auge über den Hinterkopf zum rechten Auge hin, der zweite befindet sich parallel laufend wenige Zentimeter tiefer im Nacken und ist etwas kürzer. Ansonsten sind der Kopf und der vordere Halsbereich hellgrau bis weiß, der Hinterhals dagegen schwarz gefärbt; letzterer besitzt zwei länggseitig verlaufende weiße Streifen. Das Körpergefieder hat außer auf der reinweißen Bauchseite im allgemeinen eine helle silbergraue Farbe, die Flanken sind meistens etwas dunkler, die Flügeldecken dagegen eher aufgehellt, während die eigentlichen Flugfedern in tiefschwarz gehalten sind. Der hell- bis orangegelbe Schnabel wird zwischen 4,5 und 6,5 Zentimeter lang, Augenfarbe ist dunkelbraun, die Füße sind orangefarben.

Neugeborene Streifengänse, die etwa 80 Gramm wiegen, tragen dagegen Tarnfarben: Sie haben einen grauen Schnabel und graue Füße, auch die Rückenseite ist grau gefärbt, während die Bauchseite dunkelgelb aussieht. Vor allem um die Augen herum und am Hinterkopf ist das Gefieder zudem mit kleinen braunen Flecken gesprenkelt. Eine von den Augen zum Hinterkopf laufende hellbraune Linie ist ein spezifisches Erkennungsmerkmal.

Verbreitung und LebensraumStreifengänse sind Zugvögel, die halbjährlich zwischen ihren Brut- und Überwinterungsgebieten hin- und herziehen. Erstere liegen vor allem in den Hochebenen Zentralasiens, in Südostrussland, Tibet, Teilen Nordindiens, der Mongolei und der Volksrepublik China, letztere dagegen hauptsächlich südlich des Himalaja im Nordwesten und zentralen Süden Indiens, in Pakistan, Bangladesch, Nepal und Burma; manche Vögel ziehen auch nur aus den Hochlagen Tibets in tiefer liegende Gebiete.

In Europa kommt die Streifengans ausschließlich als Gefangenschaftsflüchtling vor; die meisten Tiere sind wahrscheinlich aus Zoos, öffentlichen Gartenanlagen mit Ziergeflügelteichen oder privaten Zuchtstationen entflohen. Obwohl es bereits zu erfolgreichen Freibruten kam, scheint eine dauerhafte Etablierung als Neozoon unwahrscheinlich, da sie recht leicht mit Graugänsen verbastardiert und die Nachkommen fruchtbar sind, so dass die immer wieder auftretenden Einzeltiere, Paare oder kleine Trupps wohl in der Grauganspopulation aufgehen werden.Das Brutgebiet der Streifengans liegt in Seenlandschaften, Flussniederungen oder Mooren, besonders in Zentralasien auch in Steppengebieten oder Heideland. In Tibet halten sich die kälteangepassten Vögel auch auf bis zu 5600 Metern hoch gelegenen Felsabhängen auf. Im Überwinterungsgebiet bilden dagegen ruhige Seen, Flussauen und niedrig gelegene Sümpfe ihren Lebensraum.

FlugvermögenBeim Zug zwischen Winter- und Brutgebiet müssen viele Streifengänse das Himalaja-Gebirge überqueren. Dabei werden teilweise Flughöhen von über 9000 Metern erreicht: Streifgänse wurden schon beim Flug über den Mount Everest beobachtet und sind damit die höchstfliegenden Vögel der Erde. Den Sauerstoffmangel in diesen Höhen (der Sauerstoffpartialdruck liegt bei nur etwa 30 % des Wertes, der auf Meereshöhe gemessen wird) überstehen sie durch eine spezielle Anpassung: Der rote Blutfarbstoff, das Hämoglobin, ist bei ihnen anders als bei Säugetieren oder anderen Vögeln zu einer besonders schnellen Sauerstoffaufnahme bei niedrigem Druck in der Lage. Auslöser ist eine einzige Mutation, durch welche die Aminosäure Prolin in der so genannten Alpha-Kette des Hämoglobins durch Alanin ersetzt ist.

Ernährung und LebensweiseNahrungsgrundlage der Streifengans sind Teile von Wasserpflanzen sowie Gräser, Wurzeln und Sprosse, die wie beispielsweise Riedgras regelrecht abgeweidet werden. Im Winter werden auch Getreidekörner und Wurzelknollen verzehrt; auch Seetang kann in Küstennähe einen wichtigen Nahrungsbestandteil bilden. Diese Grundlage wird ergänzt durch Insekten, kleine Krebstiere, Weichtiere wie beispielsweise Schnecken und sogar kleine Fische.

Meistens fressen die Gänse nachts oder kurz nach Sonnenauf- beziehungsweise vor Sonnenuntergang. Vor allem in ihrem Überwinterungsgebiet fliegen sie meistens täglich in großen Schwärmen zwischen den räumlich getrennten Ruhe- und Weideplätzen hin und her. Sie sind wie die meisten Gänsearten sehr soziale, gesellschaftliebende Tiere und verständigen sich untereinander in den typischen "honk, honk"-Rufen.

FortpflanzungStreifengänse werden in ihrem zweiten bis dritten Lebensjahr geschlechtsreif und verpaaren sich dann auf Lebenszeit. Sie treffen bereits als Paar zwischen Ende März und Mitte April in ihrem zu diesem Zeitpunkt noch von Schnee bedeckten Brutgebiet ein und beginnen mit der Nistplatzsuche. Es entwickeln sich meistens locker organisierte Brutkolonien, in denen 10 bis 30 Paare auf engem Raum brüten; oft sind die alleine von den Weibchen gebauten flachen, aber nur selten weich ausgelegten Nester nur zwei bis drei Meter voneinander entfernt. Als Nistplatz dienen meistens kleine grasbewachsene Inseln in den Steppenseen oder Sümpfen des Brutgebiets, auch nahe am Wasser gelegene flache Schotterbänke werden gerne genutzt, in Tibet auch die Felsklippen der Hochtäler, oft in unmittelbarer Nähe von Kolkrabennestern oder Greifvogelhorsten. Aus der Mongolei wird berichtet, dass Streifengänse ehemalige in Pappeln gelegene Greifvogelhorste nutzen.

Je nach lokalen Klimaverhältnissen legt das Weibchen zwischen Anfang Mai und Juni zwei bis acht, im Durchschnitt aber meistens vier oder fünf weiße Eier, die es dann für gute vier Wochen bebrütet, während das Männchen den Brutplatz bewacht. Die Jungen schlüpfen nahezu gleichzeitig nach gut vier Wochen, sie werden kurz nachher von ihren Eltern durch Zuruf zum Wasser gelockt, wo sie sicherer vor Fressfeinden sind. Sie müssen dabei aus ihren hochgelegenen Nestern oft große Distanzen überwinden: So ist aus Tibet ein 25-Meter-Sprung bezeugt, nach dem das Jungtier nach einer kurzen Phase der Besinnungslosigkeit unversehrt zu seinen rufenden Eltern lief! Flugfähigkeit erreichen sie aber erst nach sechseinhalb bis siebeneinhalb Wochen; nur ein bis drei Jungtiere pro Familie überleben gewöhnlich bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt. Wenig später, etwa acht Wochen nach dem Schlüpfen, hat sich dann schon das typische Erwachsenengefieder herausgebildet. Bei den Eltern setzt ungefähr Mitte Juli, bei nicht-nistenden Vögeln zwei Wochen zuvor, die Mauser ein, bei der sie ihre Flugfedern verlieren. Sie werden etwa zur selben Zeit wie ihr Nachwuchs wieder flugfähig und können dann gemeinsam mit diesem im September in die Winterquartiere abziehen, wo die Jungen noch bis zum nächsten Jahr im Verbund mit ihren Eltern bleiben.

Bei der Partnerwahl sind Streifengänse nicht unbedingt wählerisch: Hybride mit der Graugans (Anser anser), aber auch der in einer anderen Gattung stehenden Weißwangengans (Branta leucopsis) sind bekannt; daneben wurden sogar Paarungen mit der Brandgans (Tadorna tadorna), der Paradieskasarka (Tadorna variegata) und der Halsbandkasarka (Tadorna tadornoides) berichtet, die sogar in eine andere Unterfamilie eingeteilt werden.Gefährdung

Der Artbestand wird heute je nach Quelle auf 10.000 bis 20.000 Vögel geschätzt, Tendenz fallend. Vor allem durch Abschuss, Eiraub und Verlust des Lebensraumes gelten sie heute sowohl in Indien, als auch in Pakistan und China als gefährdet.

Streifengans und der MenschStreifengänse werden hauptsächlich in ihren Überwinterungsgebieten verfolgt und sind dort daher sehr scheu; im Brutgebiet sind sie dagegen sehr zutraulich und haben eine geringe Fluchtdistanz. Sie gelten wegen ihrer geringen Aggressivität als ideale Zuchtvögel und können leicht in Gefangenschaft gehalten werden.

Bereits in alten indischen Epen taucht die Streifengans unter den Sanskrit-Namen Hamsa beziehungsweise Hans auf - beide sind etymologisch mit dem deutschen Wort Gans und dem lateinischen Anser verwandt und gehen wie letztere auf das protoindogermanische Wort ghans zurück. Sie gilt noch heute als Symbol für den Gott Brahma, den Schöpfer des Alls; auf seinem bedeutendsten Tempel aus dem 14. Jahrhundert im indischen Pushkar ist sie über dem Eingangstor abgebildet. Daneben ist sie aber auch das Wahrzeichen der Paramahamsa, der weltabgewandten Weisen, weil sie hoch über den niedrigen und kleinlichen Beschwernissen des Alltags in vollendeter Schönheit auf das Göttliche zufliegt - ihre jährliche Wanderung über den Himalaja gilt als religiöse Pilgerfahrt. Ihre Silben ha (Ausatmen) und sa (Einatmen) werden zudem mit der im Hinduismus wichtigen Erfahrung des Atems."[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anser_indicus. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-19]

66 Uddhaṃ cāruvitānante

muttākiṃkiṇikajālakaṃ

Suvaṇṇaghaṇṭāpantī ca dāmāni ca tahiṃ tahiṃ.

66.

Über dem Bodhibaum war am Saum eines schönen Baldachins ein Netz aus Perlenglöckchen und Reihen von Goldglocken. Hier und dort waren Bänder.

67 Vitānacatukoṇamhi muttādāmakalāpako

Navasatasahassaggho ekeko āsi lambito.

67.

An den vier Ecken des Baldachins hingen Bündel von Perlbändern, jedes einzelne war 900.000 Kahāpaṇa1 wert.

Kommentar:

1 Kahāpaṇa: Sanskrit: Karṣāpaṇa: Silbermünze mit ca. 3,3 g reinem Silber. 900.000 Kahāpaṇa = ca. 3000 kg Silber.

68 Ravicandatārarūpāni nānāpadumakāni

ca

Ratanehi katān' eva vitāne appitān' ahuṃ.

68.

Am Baldachin waren aus Edelsteinen gefertigte Figuren von Sonne, Mond und Sternen sowie verschiedenerlei Lotusse angebracht.

69 Aṭṭhuttarasahassāni vatthāni

vividhāni ca

Mahagghanānāraṅgāni vitāne lambitān' ahuṃ.

69.

10081 wertvolle, verschiedenfarbige Stoffe hingen am Baldachin.

Kommentar:

1 1008 ist eine vollkommene, heilige Zahl [1008 = 7x9x(7+9)], die im Hinduismus in vielen Zusammenhängen vorkommt (z.B. 1008 Namen und Anrufungen einer Gottheit).

70 Bodhiṃ parikkhipitvāna

nānāratanavedikā,

Mahāmalakamuttāhi santhāro tu tadantare.

70.

Um den Bodhi-Baum lief eine Ballustrade aus verschiedenerlei Juwelen. Der Boden innerhalb der Ballustrade bestand aus Perlen, so groß wie große Myrobalanen1.

Kommentar:

1 Myrobalanen: Phyllanthus emblica = Emblica officinalis. Früchte haben einen Durchmesser von 2,5 bis 3 cm, besonders große Früchte können in Indien einen Durchmesser bis 5 cm haben. Vgl. Mahāvaṃsa, Kapitel 28, Vers 36.

Abb.: Emblica officinalis

[Bildquelle: http://www.rspg.thaigov.net/homklindokmai/budhabot/makampom.htm. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-13]

71 Nānāratanapupphānaṃ

catugandhūdakassa ca

Puṇṇāpuṇṇaghaṭapantī bodhimūle katā ahuṃ.

71.

Am Fuß des Bodhi-Baums waren Reihen vonTöpfen, teils leer teils gefüllt mit Blumen aus verschiedenerlei Juwelen und mit Wasser mit den vier Wohlgerüchen.

72 Bodhipācīnapaññatte pallaṅke

koṭiagghake

Sovaṇṇabuddhapaṭimaṃ nisīdāpesi bhāsuraṃ.

72.

Auf den Thron, der östlich vom Bodhibaum stand und der 10 Millionen Kahāpaṇa1 wert war, ließ der König eine strahlende goldene Buddhastatue setzen.

Kommentar:

1 Kahāpaṇa: Sanskrit: Karṣāpaṇa: Silbermünze mit ca. 3,3 g reinem Silber. 10 Millionen Kahāpaṇa = ca. 33.000 kg Silber

73 Sarīrāvayavā tassā paṭimāya

yathārahaṃ

Nānāvaṇṇehi ratanehi katā surucirā ahuṃ.

73.

Die Glieder des Körpers in dieser Statue waren sehr schön, wirklichkeitsgetreu aus verschiedenfarbigen Edelsteinen gemacht.

74 Mahābrahmā ṭhito tattha

rajatacchattadhārako;

Vijayuttarasaṅkhena Sakko ca abhisekado;

74.

Mahābrahma1 stand dort und hielt (über dem Thron) einen Schirm aus Silber und Sakka2 wie er mit dem Schneckenhorn Vijayuttara3 das Wasser der Weihe gießt.

Kommentar:

1 Mahābrahma

"Brahmalakoka The highest of the celestial worlds, the abode of the Brahmas. It consists of twenty heavens:

- the nine ordinary Brahma-worlds,

- the five Suddhāvāsā,

- the four Arūpa worlds (see loka),

- the Asaññasatta and

- the Vehapphala (e.g., VibhA.521).

All except the four Arūpa worlds are classed among the Rūpa worlds (the inhabitants of which are corporeal). The inhabitants of the Brahma worlds are free from sensual desires (but see the Mātanga Jātaka, (J.497), where Ditthamangalikā is spoken of as Mahābrahmabhariyā, showing that some, at least, considered that Mahābrahmas had wives).

The Brahma world is the only world devoid of women (DhA.i.270); women who develop the jhānas in this world can be born among the Brahmapārisajjā (see below), but not among the Mahābrahmas (VibhA.437f). Rebirth in the Brahma world is the result of great virtue accompanied by meditation (Vsm.415). The Brahmas, like the other celestials, are not necessarily sotāpanna or on the way to complete knowledge (sambodhi-parāyanā); their attainments depend on the degree of their faith in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha. See, e.g., A.iv.76f.; it is not necessary to be a follower of the Buddha for one to be born in the Brahma world; the names of six teachers are given whose followers were born in that world as a result of listening to their teaching (A.iii.371ff.; iv.135ff.).

The Jātakas contain numerous accounts of ascetics who practised meditation, being born after death in the Brahma world (e.g., J.ii.43, 69, 90; v.98, etc.). Some of the Brahmas - e.g., Baka - held false views regarding their world, which, like all other worlds, is subject to change and destruction (M.i.327). When the rest of the world is destroyed at the end of a kappa, the Brahma world is saved (Vsm.415; KhpA.121), and the first beings to be born on earth come from the ābhassara Brahma world (Vsm.417). Buddhas and their more eminent disciples often visit the Brahma worlds and preach to the inhabitants. E.g., M.i.326 f.; ThagA.ii.184ff.; Sikhī Buddha and Abhibhū are also said to have visited the Brahma world (A.i.227f.). The Buddha could visit it both in his mind made body and his physical body (S.v.282f.).

If a rock as big as the gable of a house were to be dropped from the lowest Brahma-world it would take four months to reach the earth travelling one hundred thousand leagues a day. Brahmas subsist on trance, abounding in joy (sappītikajjhāna), this being their sole food. SA.i.161; food and drinks are offered to Mahābrahmā, and he is invited to partake of these, but not of sacrifices (SA.i.158 f.). Anāgāmins, who die before attaining arahantship, are reborn in the Suddhāvāsā Brahma-worlds and there pass away entirely (see, e.g., S.i.35, 60, and Compendium v.10). The beings born in the lowest Brahma world are called Brahma-pārisajjā; their life term is one third of an asankheyya kappa; next to them come the Brahma-purohitā, who live for half an asankheyya kappa; and beyond these are the Mahā Brahmas who live for a whole asankheyya kappa (Compendium, v.6; but see VibhA.519f., where Mahā Brahmās are defined).

The term Brahmakāyikā-devā seems to be used as a class-name for all the inhabitants of the Brahma-worlds (A.i.210; v.76f).

The Mahā Niddesa Commentary (p.109) says that the word includes all the five (?) kinds of Brahmā (sabbe pi pañca vokāra Brahmāno gahitā).

The BuA.p.10 thus defines the word Brahmā: brūhito tehi tehi gunavisesahī ti=Brahmā. Ayam pana Brahmasaddo Mahā-Brahma-brāhmana-Thathāgata mātāpitu-setthādisu dissati.

The Samantapāsādikā (i.131) speaks of a Mahā Brahmā who was a khināsava, living for sixteen thousand kappas. When the Buddha, immediately after his birth, looked around and took his steps northward, it was this Brahmā who seized the babe by his finger and assured him that none was greater than he.