mailto: payer@hdm-stuttgart.de

Zitierweise / cite as:

Mahanama <6. Jhdt n. Chr.>: Mahavamsa : die große Chronik Sri Lankas / übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer. -- 31. Kapitel 31: Das Einsetzen der Reliquien. -- Fassung vom 2006-09-04. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/mahavamsa/chronik31.htm. -- [Stichwort].

Erstmals publiziert: 2006-07-26

Überarbeitungen: 2006-09-04 [Ergänzungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltungen, Sommersemester 2001, 2006

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Übersetzers.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Buddhismus von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Zahlreichen Zitate aus Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. sind ein Tribut an dieses großartige Werk. Das Gesamtwerk ist online zugänglich unter: http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/dic_idx.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-05-08.

Ekatiṃsatimo paricchedo

Dhātunidhānaṃ nāma

Alle Verse mit Ausnahme des Schlussverses sind im Versmaß vatta = siloka = Śloka abgefasst.

Das metrische Schema ist:

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉˉ

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ˉ

Ausführlich zu Vatta im Pāli siehe:

Warder, A. K. (Anthony Kennedy) <1924 - >: Pali metre : a contribution to the history of Indian literature. -- London : Luzac, 1967. -- XIII, 252 S. -- S. 172 - 201.

1 Dhātugabbhamhi kammāni niṭṭhāpetvā arindamo

Sannipātaṃ kārayitvā saṅghassa idam abravī.

1.

Als der Feindebezwinger1 die Arbeiten an der Reliquienkammer2 zu Ende gebracht hatte ließ er die Mönchsgemeinde zsuammenkommen und sprach zu ihre:

Kommentar:

1 Feindebezwinger: König Duṭṭhagamaṇī: 101 - 77 v. Chr. König von Laṃkā. Siehe Mahāvaṃsa, Kapitel 22ff.

2 Arbeiten an der Reliquienkammer: des Mahāthūpa (großen Stūpa) in Anurādhapura: siehe Mahāvaṃsa, Kapitel 30: "Einrichtung der Reliquienkammer"

2 Dhātugabbhamhi kammāni mayā niṭṭhāpitāni hi;

Suve dhātuṃ nidhessāmi; bhante jānātha dhātuyo

2.

"Ich habe die Arbeiten an der Reliquienkammer zu Ende gebracht. Morgen werde ich die Reliquie niederlegen. Ehrwürdige, ihr kennt die Reliquien."

3 Idaṃ vatvā mahārājā nagaraṃ pāvisī; tato

Dhātuāharakaṃ bhikkhuṃ bhikkhusaṅgho vicintayi

3.

So sprach der Großkönig und zog in die Stadt. Dann beriet die Mönchsgemeinde über einen Mönch, der Reliquien holen sollte.

4 Soṇuttaraṃ nāma yatiṃ Pūjāpariveṇavāsikaṃ

Dhātāharaṇakammamhi chalabhiññaṃ niyojayi.

4.

Sie beauftragte den im Pūjāpariveṇa wohnenden Asketen Soṇuttara1, der die sechs höheren Geisteskräfte2 besaß, Reliquien zu holen.

Kommentar:

1 Soṇuttara

"Soṇuttara Thera. An arahant. He lived in the Pūjā-parivena in the Mahāvihāra and was entrusted by Dutthagāmanī with the task of finding relics for the Mahā Thūpa. In the time of the Buddha he had been the brahmin Nanduttara, and had entertained the Buddha on the occasion on which, at Payāgatittha, Bhaddaji Thera had raised, from the bed of the Ganges, the palace he had occupied as Mahāpanāda. Filled with marvel, Nanduttara wished that he might have the power of procuring relics possessed by others. Sonuttara visited the Mañjerika-nāga-bhavana and asked the Nāga king, Mahākāla, to give him the relics which he had there and which had once been enshrined in Rāmagāma. But Mahākāla, unwilling to part with them, told his nephew, Vāsuladatta, to hide them. Sonuttara knew this, and when Mahākāla told him he might take the relics if he could find them, Sonuttara, by his magic power, took the relic casket from Vāsuladatta, unknown to him, and brought it to Anurādhapura, where the relics were deposited in the Mahā Thūpa. Mhv.xxxi.4-74."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

2 sechs höhere Geisteskräfte: abhiññā f.

- lokiyā abhiññā f. -- weltliche höhere Geisteskräfte:

1. iddhi-vidhā f. -- die verschiedenen Fähigkeiten außergewöhnlicher Macht (iddhi):

- einer seiend wird er vielfach und vielfach geworden wird er wieder einer

- er macht sich sichtbar und unsichtbar

- ungehindert schwebt er durch Wände, Mauern und Berge hindurch

- auf dem Wasser schreitet er dahin ohne unterzusinken

- in der Erde taucht er auf und unter

- mit gekreuzten Beinen schwebt er durch die Luft

- Sonne und Mond berührt er mit seiner Hand

- bis hinauf zur Brahmawelt hat er über seinen Körper Gewalt

(z.B. auch Sāmaññaphalasutta : Dīghanikāya I, 77)

2. dibba-sota -- das himmlische Ohr: Fähigkeit himmlische und menschliche Töne zu hören, ferne und nahe3. parassa ceto-pariyañāṇa n. -- das Durchschauen der Herzen anderer: Erkennen des Bewusstseins anderer, ob gierbehaftet usw.

4. pubbe-nivāsānussati f. -- Erinnerung an frühere eigene Daseinsformen5. dibba-cakkhu n. -- das himmlische Auge: man sieht wie andere Wesen vergehen und wiederentstehen

- lokuttarā abhiññā : überweltliche höhere Geisteskraft (durch Vipassanā erreichbar):

6. āsava-kkhaya-ñāṇa n. -- Wissen um die eigene Triebversiegung

(Dutiya-āhuneyyasutta : Aṅguttaranikāya III, 280 - 281; Nal III; 3, 16 - 5, 7; Th 22, 312 - 314)

s. Nāgārjuna: La traité de la grande vertu de sagesse (Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra) / [Trad. par] Étienne Lamotte. -- Tome IV. -- p. 1809 - 1827.

5 Cārikaṃ caramānamhi nāthe lokahitāya hi

Nanduttaro ti nāmena Gaṅgātīramhi māṇavo

6 Nimantetvābhisambuddhaṃ sahasaṅghaṃ abhojayi.

Satthā Payāgapaṭṭane sasaṅgho nāvam āruhi.

5. - 6.

Als der Schutzherr (Buddha) zu ihrem Heil auf der Welt wandelte, hat am Ufer des Ganges Nanduttaro, ein junger Brahmane, den Sambuddha zusammen mit der Mönchsgemeinde eingeladen und gespeist. Der Lehrer (Buddha) bestieg im Hafen von Payāga1 ein Schiff.

Kommentar:

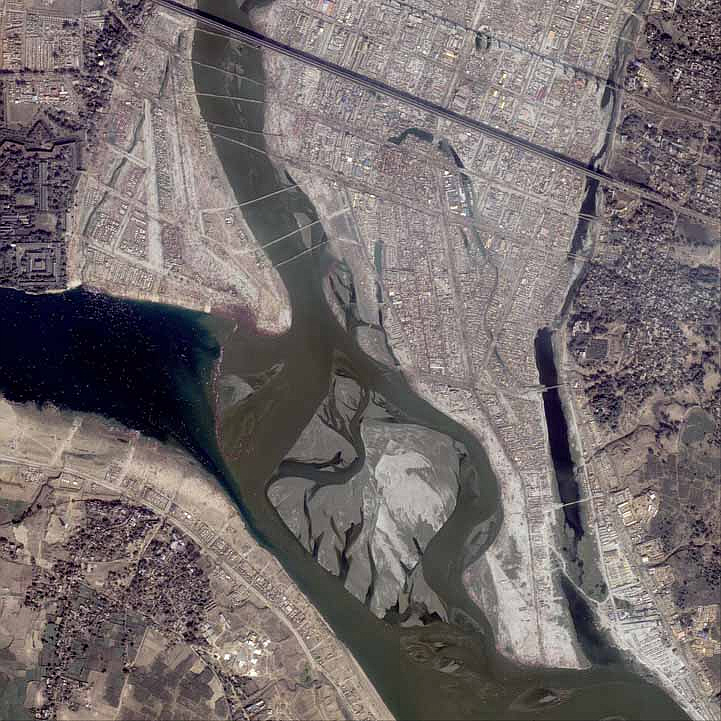

1 Payāga: Sanskrit Prayāga, heutiges Allahabad (Hindi: इलाहाबाद; Urdu: الاهاباد Ilāhābād)

Abb.: Lage von Payāga/Prayāga/Allahabad

(©MS Encarta)

Abb.: Satellitenbild der Kumbh Mela in Prayāga

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"Payāga, Payāgatittha, Payāgapatiṭṭhāna A ford on the Ganges, on the direct route from Verañjā to Benares, the road passing through Soreyya, Sankassa and Kannakujja, and crossing the Ganges at Payāga (Vin.iii.11).

It was one of the river ghats where people did ceremonial bathing to wash away their sins (M.i.39; J.vi.198). It was here that the palace occupied by Mahāpanāda was submerged. The Buddha passed it when visiting the brahmin Nanduttara, and Bhaddaji, who was with him, raised the palace once more above the water. Bhaddaji had once been Mahāpanāda (Mhv.xxxi.6ff).

Buddhaghosa says (MA.i.145; DA.iii.856) the bathing place was on the spot where the palace stairs had stood. Reference is made to Payāga even in the time of Padumuttara Buddha (AA.i.126).

It is identified with the modern Allahabad, at the confluence of the Gangā and the Yamunā."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

"Allahabad (Hindi: इलाहाबाद; Urdu: الاهاباد Ilāhābād) is a city in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. The name was given to the city by the Mughal Emperor Akbar (Persian: جلال الدین محمد اکبر) in 1583. The "Allah" in the name does not come from Allah as God's name in Islam but from the Din-Ilahi (Arabic: دين إلهي ), which was the religion founded by Akbar. In Indian alphabets it is spelt "Ilāhābād": "ilāh" is Arabic for "a god" (but in this context from Din-Ilahi), and "-ābād" is Persian for "place of".

The modern city is on the site of the ancient holy city of Prayāga (Sanskrit for "place of sacrifice" and is the spot where Brahma offered his first sacrifice after creating the world). It is one of four sites of the Kumbha Mela (Hindi, m., कुंभ मेला), the others being Haridwar, Ujjain and Nasik. It has a position of importance in the Hindu religion and mythology since it is situated at the confluence of the rivers Ganga and Yamuna (यमुना), and Hindu belief says that the invisible Sarasvati River joins here also. This belief may have arisen because the real ancient Sarasvati River dried up because its main headwater was diverted eastwards into the upper Yamuna and thus its water reached Allahabad along with the Yamuna.

Because solar events in Allahabad occur exactly 5 hours and 30 minutes ahead of Greenwich, the city is the reference point for Indian Standard Time, maintained by the city's observatory.The city has Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology one of the renowned technical institutes in India.

HistoryAllahabad is a historian's paradise. History lies embedded everywhere, in its fields, forests and settlements. Forty-eight kilometres, towards the southwest, on the placid banks of the Jamuna, the ruins of Kaushambi, capital of the Vatsa kingdom and a thriving center of Buddhism, bear silent testimony to a forgotten and bygone era. On the eastern side, across the river Ganga and connected to the city by the Shastri Bridge is Jhusi, identified with the ancient city of Pratisthanpur, capital of the Chandra dynasty. About 58 kilometres northwest is the medieval site of Kara with its impressive wreckage of Jayachand's fort. Sringverpur, another ancient site discovered relatively recently, has become a major attraction for tourists and antiquarians alike.

Allahabad is an extremely important and integral part of the Ganga Yamuna Doab, and its history is inherently tied with that of the Doab region, right from the inception of the town.

The city was known earlier as Prayāga - a name that is still commonly used.

When the Aryans first settled in what they termed the Aryavarta, or Madhydesha, Prayag or Kaushambi was an important part of their territory. The Vatsa (a branch of the early Indo-Aryans) were rulers of Hastinapur, and they established the town of Kaushambi near present day Allahabad. They shifted their capital to Kaushambi when Hastinapur was destroyed by floods.

In the times of the Ramayana, Allahabad was made up of a few rishis' huts at the confluence of the rivers, and much of what is now central/ southern Uttar Pradesh was continuous jungle. Lord Rama, the main protagonist in the Ramayana, spent some time here, at the Ashram of Sage Bharadwaj, before proceeding to nearby Chitrakoot.

The Doaba region, including Allahabad was controlled by several empires and dynasties in the ages to come. It became a part of the Mauryan and Gupta empires of the east and the Kushan empire of the west before becoming part of the local Kannauj empire which became very powerful.

In the beginning of the Muslim rule, Allahabad was a part of the Delhi Sultanate. Then the Mughals took over from the slave rulers of Delhi and under them Allahabad rose to prominence once again.

Acknowledging the strategic position of Allahabad in the Doaba or the "Hindostan" region at the confluence of its defining rivers which had immense navigational potentials, Akbar built a magnificent fort on the banks of the holy Sangam and re-christened the town as Illahabad in 1575. The Akbar fort has an Ashokan pillar and some temples, and is largely a military barracks. On the southwestern extremity of Allahabad lies Khusrobagh that antedates the fort and has three mausoleums, including that of Jehangir's first wife – Shah Begum. Before colonial rule was imposed over Allahabad, the city was rocked by Maratha incursions. But the Marathas also left behind two beautiful eighteenth century temples with intricate architecture.

In 1765, the combined forces of the Nawab of Awadh and the Mughal emperor Shah Alam lost the war of Buxar to the British. Although, the British did not take over their states, they established a garrison at the Allahabad fort. Governor General Warren Hastings later took Allahabad from Shah Alam and gave it to Awadh alleging that he had placed himself in the power of the Marathas.

In 1801 the Nawab (Urdu: نواب ) of Awadh ceded the city to the British East India Company. Gradually the other parts of Doaba and adjoining region in its west (including Delhi and Ajmer-Mewara regions) were won by the British. When these north western areas were made into a new Presidency called the "North Western Provinces of Agra", its capital was Agra. Allahabad remained an important part of this state.

In 1834, Allahabad became the seat of the Government of the Agra Province and a High Court was established. But a year later both were relocated to Agra.

In 1857, Allahabad was active in the Indian Mutiny. After the mutiny, the British truncated the Delhi region of the state, merging it with Punjab and transferred the capital of North west Provinces to Allahabad, which remained so for the next 20 years.

In 1877 the two provinces of Agra (NWPA) and Awadh were merged to form a new state which was called the United Provinces. Allahabad was the capital of this new state till the 1920s.

An ancient seat of learningIt was a well-known centre of education (dating from the time of the Buddha), and in the first few decades of the 20th century. In the 19th century, the Allahabad University earned the epithet of 'Oxford of the East'. It is also a major literary centre for Hindi. It holds the world record for the world's first letter delivered by airmail (from Allahabad to Naini, just a few km. across the river Yamuna) (1911).

Allahabad's role in the freedom struggleDuring the 1857 rebellion there was an insignificant presence of European troops in Allahabad. Taking advantage of this, the rebels brought Allahabad under their control. It was around this time that Maulvi Liaquat Ali Khan unfurled the banner of revolt. Long after the mutiny had been quelled, the establishment of the High Court, the Police Headquarters and the Public Service Commission, transformed the city into an administrative center, a status that it enjoys even today.

The fourth session of the Indian National Congress was held in the city in 1888. At the turn of the century Allahabad also became a nodal point for the revolutionaries. The Karmyogi office of Sundar Lal in Chowk sparked patriotism in the hearts of many young men. Nityanand Chatterji became a household name when he hurled the first bomb at the European club. During the movement for independence, Allahabad was at the forefront of all political activities. Alfred Park in Allahabad was the site where, in 1931, the revolutionary Chandrashekhar Azad killed himself when surrounded by the British Police. Anand Bhavan, and an adjacent Nehru family home, Swaraj Bhavan, were the center of the political activities of the Indian National Congress. In the climactic years of the freedom struggle, thousands of satyagrahis, led, inter alia, by Purshottam Das Tandon, Bishambhar Nath Pande and Narayan Dutt Tewari, went to jail. And when freedom finally came, the first Prime Minister of free India, Jawahar Lal Nehru, and Union ministers like Mangla Prasad, Muzaffar Hasan, K. N. Katju, Lal Bahadur Shastri, all were from Allahabad.

Allahabad was the birthplace of Jawaharlal Nehru (Hindi: जवाहरलाल नहरू), and the Nehru family estate, called the Anand Bhavan, is now a museum. It was also the birthplace of his daughter Indira Gandhi (Hindi: इन्दिरा प्रियदर्शिनी गान्धी), and the home of Lal Bahadur Shastri (Hindi लालबहादुर शास्त्री), both later Prime Ministers of India. In addition Vishwanath Pratap Singh (विश्वनाथ प्रताप सिंह) and Chandra Shekhar were also associated with Allahabad. Thus Allahabad has the distinction of being the home of several Prime Ministers in India's post-independence history.

The first seeds of the idea of Pakistan were also sown in Allahabad. On 29 December 1930, Allama Muhammad Iqbal's (Urdu: محمد اقبال, Hindi: मुहम्मद इकबाल) presidential address to the All-India Muslim League (Urdu: مسلم لیگ) proposed a separate Muslim state for the Muslim majority regions of India.

GeographyIt is located in the southern part of the state, at , and stands at the confluence of the Ganga (Ganges), and Yamuna rivers. To its west and south is the Bundelkhand region, and to its east is the Baghelkhand region.

Allahabad stands at a strategic point both geographically and culturally. An important part of the Ganga-Yamuna Doaba region, it is the last point of the Yamuna river and is the last frontier of the west Indian culture.

The land between the Doaba is just like the rest of Doaba --- fertile but not too moist, which is especially suitable for the production of wheat. The southern and eastern part of the district are somewhat similar to those of adjoining Budelkhand and Baghelkhand regions, viz. dry and rocky.

IST is measured by the local time of the observatory in Allahabad.

DemographyAllahabad City has a population of 1,050,000 as per the 2001 census with about 580,000 males and 470,000 females. It lists as the 32nd most populous city in India. Allahabad has an area of about 65 kmī and is 98 m above sea level. Languages spoken in and around Allahabad include Hindi, English, Urdu, and some Bengali, and Punjabi. There is also a small population of Kashmiris in the city.

The dialect of Hindi spoken in Allahabad is Awadhi, although khari boli is most commonly used in the city area. All major religions are practised in Allahabad.

ClimateAllahabad experiences all four seasons. The summer season is from April to June with the maximum temperatures ranging between 40 to 45 °C. Monsoon begins in early July and lasts till September. The winter season falls in the months of December, January and February. Temperatures in the cold weather could drop to freezing with maximum at almost 12 to 14 °C. Allahabad also witnesses severe fog in January resulting in massive traffic and travel delays. It does not snow in Allahabad.

Lowest temperature recorded −2 °C; highest, 48 °C.

Kumbha (Hindi, m., कुंभ मेला) and Magh Mela (Hindi: माघ मेला)The word 'Mela' is fair in Hindi. Except in the years of the Kumbha Mela and the Ardha Kumbha Mela (Ardha is half in Hindi, hence the Ardha Kumbha Mela is held every 6th year), the Magh Mela takes place every year in the month of Magh (Jan - Feb) of the Hindu calendar. Kumbh Mela (the Urn Festival) occurs four times every twelve years and rotates between four locations: Prayag (Allahabad), Haridwar, Ujjain and Nashik.

In Allahabad, these religious fairs take place at the Sangam (confluence) of the Yamuna and the Ganges River which is holy in Hinduism. In the Kumbha Mela of 2001, which was called the Maha (great) Kumbha Mela because of an alignment of the Sun, Moon, and Jupiter that occurred only every 144 years, almost 75 million people visited the banks of the river to take part in the festivals. During the Melas, an entire township is built on the river's banks, with functioning hospitals, fire stations, police stations, restaurants and other facilities.

Literary PastPerhaps Allahabad is most famous for the literary geniuses it has produced. Most of the famous writers in Hindi literature had a connection with the city. Notable amongst them were Mahadevi Varma (महादेवी वर्मा), Sumitranandan Pant (सुमित्रानन्दन पंत), Suryakant Tripathi 'Nirala' (सूर्यकांत त्रिपाठी 'निराला'), Upendra Nath 'Ashk' and Harivansh Rai Bachchan. Another noteworthy poet was Raghupati Sahay who was more famous by the name of Firaq Gorakhpuri. Firaq was an outstanding literary critic and one of major Urdu poets of the last century. Both Firaq and Bachchan were professors of English at Allahabad University. Firaq Gorakhpuri and Mahadevi Varma were awarded the Jnanpith Award, the highest literary honour conferred in the Republic of India in 1969 an 1982 respectively.

The famous English author and Nobel Laureate (1907) Rudyard Kipling also spent time at Allahabad working for The Pioneer as an assistant editor and overseas correspondent.

Sports and RecreationAllahabad is well known for its sporting activities in the fields of Cricket, Badminton, Tennis and Gymnastics. There are several sports complexes that can be used by both amateurs and professionals. These include the Madan Mohan Malaviya Cricket stadium, Mayo Hall Sports Complex and the Boys' High School & College Gymnasium. There are several swimming facilities throughout the city as well.

Allahabad has a prominent place in Indian Gymnastics. It is the leading team in SAARC and Asian countries.

Mohammed Kaif member of Indian Cricket team hails from this city.

Passenger transportationAir

Allahabad is served by the Bamrauli airport (IXD) and is linked to Delhi (Hindi: दिल्ली, Urdu: دہلی or دلّی, Punjabi: ਦਿੱਲੀ) and Kolkata (Bangla: কলকাতা) by Air Sahara. Other airports in the vicinity are Varanasi (Hindi: वाराणसी) (147 km) and Lucknow (Hindi: लखनऊ; Urdu: لکھنو; Lakʰnau) (210 km).Road

National Highway 2 runs through the center of the city. Allahabad is located in between Delhi and Kolkata on this highway. Another highway that links Allahabad is National Highway 27 that is 93 km long and starts at Allahabad and ends at Mangawan in Madhya Pradesh connecting to National Highway 7. There are other highways that link Allahabad to all parts of the country. Allahabad also has three bus stations catering to different routes - at Zero Road, Leader Road and Civil Lines.Tourist taxis, auto-rickshaws and tempos are available for local transport. There is also a local bus service that connects various parts of the city. But the most covenient method of local transport is the cycle rickshaw. Rates are not fixed and one needs to bargain.

TrainServed by Indian Railway. Allahabad is the headquarters of the North Central Railways Zone, and is well connected by trains with all major cities, namely, Kolkata, Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Lucknow and Jaipur. Allahabad has four railway stations - Prayag Station, City Station (Rambagh), Daraganj Station and Allahabad Junction (the main station).

Government, Civic Amentites and Important OfficesAllahabad is governed by a number of bodies, the prime being the Allahabad Nagar Nigam (Municipal Corporation) and Allahabad development Authority, which is responsible for the master planning of the city. Other facilities are provided by various other government utilities. For example, water supply and sewage system is maintained by Jal Nigam, a subsidiary of Nagar Nigam. Power supply is by the Uttar Pradesh Power Corporation Limited. Nagar Nigam also runs a bus service in the city and suburban areas.

Phone services in Allahabad are by BSNL, Airtel, Hutch, Reliance India Mobile and Tata Indicom. Internet services are provided by BSNL, Sify iWay and Reliance.

Allahabad is home to a large number of important government offices. Some of them are the Public Service Commission, Board of Revenue, Education Directorate, State board of Education, Police Head Quarters(UP), Income Tax and Excise Tribunal, AG of UP, numerous railway offices and a number of Defence establishments. There are as many as five defence establishments in and around the city. They are

- City Cantonment

- Chatham Lines Cantonment

- Bamrauli and Manauri air fields

- Allahabad Fort

- Ordnance depot in Naini.

Bamrauli air field is the head quarters of the Central Air Command of India.

Allahabad is the seat of the Allahabad High Court, the High Court of the state of Uttar Pradesh (along with a bench at Lucknow). It is one of the largest courts in the world in terms of the number of judges.

Entertainment and MarketsAllahabd lacks in terms of entertainment avenues. However, the city is undergoing rapid transformation with opening of a number of shopping malls, multiplexes and restaurants. Still the city has very sedate pace of life compared to other large cities.

Traditionally, the main market areas of the city are Civil Lines, Chowk and Katra. However, newer market places have developed in recent years, Allahpur being the prime example.

Famous personalities

- Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, founder of the Banaras Hindu University (काशी हिन्दू विश्वविद्यालय)

- Jawahar Lal Nehru (जवाहरलाल नहरू)

- Pandit R.S. Malviya

- Indira Gandhi (इन्दिरा प्रियदर्शिनी गान्धी)

- Rajiv Gandhi (राजीव गान्धी)

Lal Bahadur Shastri (लालबहादुर शास्त्री)

- V P Singh (वी. पी. सिंह)

- Harivansh Rai Bachchan

- Dhyan Chand

- Amitabh Bachchan (अमिताभ बच्चन, اَمِتابھ بچّن)

- Firaq Gorakhpuri

- Mahadevi Varma (महादेवी वर्मा)

- Akbar Allahabadi

- Munshi Premchand (प्रेमचंद)

- Suryakant Tripathi Nirala (सूर्यकांत त्रिपाठी 'निराला')

- Upendranath Ashk

- Ram Chandra Shukla

- Meghnad Saha (মেঘনাদ সাহা; मेघनाद साहा)

- Harish Chandra

- Hariprasad Chaurasia

- Nargis (नरगिस) -late Indian actress.

- Purushottam Das Tandon (पुरूषोत्तम दास टंडन)

- Mohammed Kaif, Member of Indian cricket team"

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohammed_Kaif. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-23]

7 Tattha Bhaddajithero tu chaḷabhiñño mahiddhiko

Jalapakkhalitaṭṭhānaṃ disvā bhikkhū idaṃ vadi:

7.

Als dort der Thera wundermächtige Bhaddajji1, der die sechs höheren Geisteskräfte2 besaß, einen Strudel sah, sprach er zu den den Mönchen Folgendes:

Kommentar:

1 Bhaddaji

"Bhaddaji Thera The son of a setthi in Bhaddiya. He was worth eighty crores, and was brought up in luxury like that of the Bodhisatta in his last birth. When Bhaddaji was grown up, the Buddha came to Bhaddiya to seek him out, and stayed at the Jātiyāvana with a large number of monks. Thither Bhaddaji went to hear him preach. He became an arahant, and, with his father's consent, was ordained by the Buddha. Seven weeks later he accompanied the Buddha to Kotigāma, and, while the Buddha was returning thanks to a pious donor on the way, Bhaddaji retired to the bank of the Ganges outside the village, where he stood wrapt in jhāna, emerging only when the Buddha came by, not having heeded the preceding chief theras. He was blamed for this; but, in order to demonstrate the attainments of Bhaddaji, the Buddha invited him to his own ferry boat and bade him work a wonder. Bhaddaji thereupon raised from the river bed, fifteen leagues into the air, a golden palace twenty leagues high, in which he had lived as Mahāpanāda. On this occasion the Mahāpanāda or Suruci Jātaka was preached.

The Mahāvamsa account (xxxi.37ff) says that, before raising Mahāpanada's palace, Bhaddaji rose into the air to the height of seven palmyra trees, holding the Dussa Thūpa from the Brahma world in his hand. He then dived into the Ganges and returned with the palace. The brahmin Nanduttara, whose hospitality the Buddha and his monks had accepted, saw this miracle of Bhaddaji, and himself wished for similar power by which he might procure relics in the possession of others. He was reborn as the novice Sonuttara, who obtained the relics for the thūpas of Ceylon.

In the time of Padumuttara Buddha, Bhaddaji was a brahmin ascetic who, seeing the Buddha travelling through the air, offered him honey, lotus stalks, etc. Soon after he was struck by lightning and reborn in Tusita. In the time of Vipassī Buddha he was a very rich setthi and fed sixty eight thousand monks, to each of whom he gave three robes. Later, he ministered to five hundred Pacceka Buddhas. In a subsequent birth his son was a Pacceka Buddha, and he looked after him and built a cetiya over his remains after his death. Thag.vs.163f.; ThagA.i.285ff.; also J.ii.331ff., where the details vary slightly; J.iv.325; also MT.560f

Bhaddaji is identified with Sumana of the Mahānārada Kassapa Jātaka (J.vi.255).

He is probably identical with Bhisadāyaka of the Apadāna (Ap.ii.420f). Bhaddaji is mentioned among those who handed down the Abhidhamma to the Third Council (DhSA.32).

See also Bhaddaji Sutta."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

2 sechs höhere Geisteskräfte: siehe oben zu Vers 4.

8 Mahāpanādabhūtena mayā vuttho suvaṇṇayo

Pāsādo patito ettha pañcavīsatiyojano;

8.

Der goldene, 25 Yojana1 große Palast, den ich bewohnte, als ich Mahāpanāda2 war, ist hier versunken.

Kommentar:

1 Yojana: 1 Yojana = ca. 11 km, 25 Yojana = ca. 275 km.

2 Mahāpanāda

"Mahāpanāda. Son of Suruci and king of Mithilā. He owned a palace one hundred storeys high, all of emerald; it was one thousand bow-shots (twenty five leagues) high and sixteen broad and held six thousand musicians.

Mahāpanāda was a previous birth of Bhaddaji. See the Mahāpanāda Jātaka (264) and also Kosalā. See also Sankha (3)."[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

Mahāpanādajātakavaṇṇanā Panādo nāma so rājā ti idaṃ satthā gaṅgātīre nisinno bhaddajittherassānubhāvaṃ ārabbha kathesi. Ekasmiñhi samaye satthā sāvatthiyaṃ vassaṃ vasitvā “bhaddajikumārassa saṅgahaṃ karissāmī”ti bhikkhusaṅghaparivuto cārikaṃ caramāno bhaddiyanagaraṃ patvā jātiyāvane tayo māse vasi kumārassa ñāṇaparipākaṃ āgamayamāno. Bhaddajikumāro mahāyaso asītikoñivibhavassa bhaddiyaseññhino ekaputtako. Tassa tiṇṇaṃ utūnaṃ anucchavikā tayo pāsādā ahesuṃ. Ekekasmiṃ cattāro cattāro māse vasati. Ekasmiṃ vasitvā nāñakaparivuto mahantena yasena aññaṃ pāsādaṃ gacchati. Tasmiṃ khaṇe “kumārassa yasaṃ passissāmā”ti sakalanagaraṃ saṅkhubhi, pāsādantare cakkāticakkāni mañcātimañcāni bandhanti.

Satthā tayo māse vasitvā “mayaṃ gacchāmā”ti nagaravāsīnaṃ ārocesi. Nāgarā “bhante, sve gamissathā”ti satthāraṃ nimantetvā dutiyadivase buddhappamukhassa bhikkhusaṅghassa mahādānaṃ sajjetvā nagaramajjhe maṇḍapaṃ katvā alaṅkaritvā āsanāni paññapetvā kālaṃ ārocesuṃ. Satthā bhikkhusaṅghaparivuto tattha gantvā nisīdi, manussā mahādānaṃ adaṃsu. Satthā niññhitabhattakicco madhurassarena anumodanaṃ ārabhi. Tasmiṃ khaṇe bhaddajikumāropi pāsādato pāsādaṃ gacchati tassa sampattidassanatthāya taṃ divasaṃ na koci agamāsi, attano manussāva parivāresuṃ. So manusse pucchi– “aññasmiṃ kāle mayi pāsādato pāsādaṃ gacchante sakalanagaraṃ saṅkhubhati, cakkāticakkāni mañcātimañcāni bandhanti, ajja pana ñhapetvā mayhaṃ manusse añño koci natthi, kiṃ nu kho kāraṇan”ti. “Sāmi, sammāsambuddho imaṃ bhaddiyanagaraṃ upanissāya tayo māse vasitvā ajjeva gamissati, so bhattakiccaṃ niññhāpetvā mahājanassa dhammaṃ deseti, sakalanagaravāsinopi tassa dhammakathaṃ suṇantī”ti. So “tena hi etha, mayampi suṇissāmā”ti sabbābharaṇapañimaṇḍitova mahantena parivārena upasaṅkamitvā parisapariyante ñhito dhammaṃ suṇanto ñhitova sabbakilese khepetvā aggaphalaṃ arahattaṃ pāpuṇi.Satthā bhaddiyaseññhiṃ āmantetvā “mahāseññhi, putto te alaṅkatapañiyattova dhammakathaṃ suṇanto arahatte patiññhito, tenassa ajjeva pabbajituṃ vā vaññati parinibbāyituṃ vā”ti āha. “Bhante, mayhaṃ puttassa parinibbānena kiccaṃ natthi, pabbājetha naṃ, pabbājetvā ca pana naṃ gahetvā sve amhākaṃ gehaṃ upasaṅkamathā”ti. Bhagavā nimantanaṃ adhivāsetvā kulaputtaṃ ādāya vihāraṃ gantvā pabbājetvā upasampadaṃ dāpesi. Tassa mātāpitaro sattāhaṃ mahāsakkāraṃ kariṃsu. Satthā sattāhaṃ vasitvā kulaputtamādāya cārikaṃ caranto koñigāmaṃ pāpuṇi. Koñigāmavāsino manussā buddhappamukhassa bhikkhusaṅghassa mahādānaṃ adaṃsu. Satthā bhattakiccāvasāne anumodanaṃ ārabhi. Kulaputto anumodanakaraṇakāle bahigāmaṃ gantvā “satthu āgatakāleyeva uññhahissāmī”ti gaṅgātitthasamīpe ekasmiṃ rukkhamūle jhānaṃ samāpajjitvā nisīdi Mahallakattheresu āgacchantesupi anuññhahitvā satthu āgatakāleyeva uññhahi. Puthujjanā bhikkhū “ayaṃ pure viya pabbajitvā mahāthere āgacchantepi disvā na uññhahatī”ti kujjhiṃsu.

Koñigāmavāsino manussā nāvāsaṅghāte bandhiṃsu. Satthā nāvāsaṅghāte ñhatvā “kahaṃ bhaddajī”ti pucchi. “Esa, bhante, idhevā”ti. “Ehi, bhaddaji, amhehi saddhiṃ ekanāvaṃ abhiruhā”ti. Theropi uppatitvā ekanāvāya aññhāsi. Atha naṃ gaṅgāya majjhaṃ gatakāle satthā āha– “bhaddaji, tayā mahāpanādarājakāle ajjhāvutthapāsādo kahan”ti. Imasmiṃ ñhāne nimuggo, bhanteti. Puthujjanā bhikkhū “bhaddajitthero aññaṃ byākarotī”ti āhaṃsu. Satthā “tena hi, bhaddaji, sabrahmacārīnaṃ kaṅkhaṃ chindā”ti āha. Tasmiṃ khaṇe thero satthāraṃ vanditvā iddhibalena gantvā pāsādathūpikaṃ pādaṅguliyā gahetvā pañcavīsatiyojanaṃ pāsādaṃ gahetvā ākāse uppati. Uppatito ca pana heññhāpāsāde ñhitānaṃ pāsādaṃ bhinditvā paññāyi. So ekayojanaṃ dviyojanaṃ tiyojananti yāva vīsatiyojanā udakato pāsādaṃ ukkhipi. Athassa purimabhave ñātakā pāsādalobhena macchakacchapanāgamaṇḍūkā hutvā tasmiṃyeva pāsāde nibbattā pāsāde uññhahante parivattitvā parivattitvā udakeyeva patiṃsu. Satthā te patante disvā “ñātakā te, bhaddaji, kilamantī”ti āha. Thero satthu vacanaṃ sutvā pāsādaṃ vissajjesi, pāsādo yathāñhāneyeva patiññhahi, satthā pāragaṅgaṃ gato. Athassa gaṅgātīreyeva āsanaṃ paññāpayiṃsu, so paññatte varabuddhāsane taruṇasūriyo viya rasmiyo muñcanto nisīdi. Atha naṃ bhikkhū “kasmiṃ kāle, bhante, ayaṃ pāsādo bhaddajittherena ajjhāvuttho”ti pucchiṃsu. Satthā “mahāpanādarājakāle”ti vatvā atītaṃ āhari.Atīte videharaññhe mithilāyaṃ suruci nāma rājā ahosi, puttopi tassa suruciyeva, tassa pana putto mahāpanādo nāma ahosi, te imaṃ pāsādaṃ pañilabhiṃsu. Pañilābhatthāya panassa idaṃ pubbakammaṃ– dve pitāputtā naḷehi ca udumbaradārūhi ca paccekabuddhassa vasanapaṇṇasālaṃ kariṃsu. Imasmiṃ jātake sabbaṃ atītavatthu pakiṇṇakanipāte surucijātake (jā. 1.14.102 ādayo) āvibhavissati.

Satthā imaṃ atītaṃ āharitvā sammāsambuddho hutvā imā gāthā avoca– 40. “Panādo nāma so rājā, yassa yūpo suvaṇṇayo;tiriyaṃ soḷasubbedho, uddhamāhu sahassadhā. 41. “Sahassakaṇḍo satageṇḍu, dhajālu haritāmayo;anaccuṃ tattha gandhabbā, cha sahassāni sattadhā. 42. “Evametaṃ tadā āsi, yathā bhāsasi bhaddaji;sakko ahaṃ tadā āsiṃ, veyyāvaccakaro tavā”ti. Tattha yūpoti pāsādo. Tiriyaṃ soḷasubbedhoti vitthārato soḷasakaṇḍapātavitthāro ahosi. Uddhamāhu sahassadhāti ubbedhena sahassakaṇḍagamanamattaṃ ucco ahu, sahassakaṇḍagamanagaṇanāya pañcavīsatiyojanappamāṇaṃ hoti. Vitthāro panassa aññhayojanamatto. Sahassakaṇḍo satageṇḍūti so panesa sahassakaṇḍubbedho pāsādo satabhūmiko ahosi. Dhajālūti dhajasampanno. Haritāmayoti haritamaṇiparikkhitto. Aññhakathāyaṃ pana “samāluharitāmayo”ti pāñho, haritamaṇimayehi dvārakavāñavātapānehi samannāgatoti attho. Samālūti kira dvārakavāñavātapānānaṃ nāmaṃ. Gandhabbāti nañā, cha sahassāni sattadhāti cha gandhabbasahassāni sattadhā hutvā tassa pāsādassa sattasu ñhānesu rañño ratijananatthāya nacciṃsūti attho. Te evaṃ naccantāpi rājānaṃ hāsetuṃ nāsakkhiṃsu, atha sakko devarājā devanañaṃ pesetvā samajjaṃ kāresi, tadā mahāpanādo hasi. Yathā bhāsasi, bhaddajīti bhaddajittherena hi “bhaddaji, tayā mahāpanādarājakāle ajjhāvutthapāsādo kahan”ti vutte “imasmiṃ ñhāne nimuggo, bhante”ti vadantena tasmiṃ kāle attano atthāya tassa pāsādassa nibbattabhāvo ca mahāpanādarājabhāvo ca bhāsito hoti. Taṃ gahetvā satthā “yathā tvaṃ, bhaddaji, bhāsasi, tadā etaṃ tatheva ahosi, ahaṃ tadā tava kāyaveyyāvaccakaro sakko devānamindo ahosin”ti āha. Tasmiṃ khaṇe puthujjanabhikkhū nikkaṅkhā ahesuṃ. Satthā imaṃ dhammadesanaṃ āharitvā jātakaṃ samodhānesi– “tadā mahāpanādo rājā bhaddaji ahosi, sakko pana ahameva ahosin”ti.Mahāpanādajātakavaṇṇanā catutthā.

"264. Die Erzählung von Mahāpanāda (Mahāpanāda-Jātaka) „Panāda, so hieß dieser König“

§A. Dies erzählte der Meister, da er am Ufer des Ganges saß, mit Beziehung auf die Wunderkraft des Thera Bhaddaji. — Nachdem nämlich zu einer Zeit der Meister zu Sāvatthi die Regenzeit verbracht hatte, dachte er: „Ich will dem Prinzen Bhaddaji eine Gunst erweisen“; und umgeben von der Mönchsgemeinde gelangte er auf seiner Wanderung nach der Stadt Bhaddiya, wo er drei Monate im Jatiya-Walde verweilte und auf das völlige Reifen der Einsicht bei dem Prinzen wartete.

Der Prinz Bhaddaji war der Hochgeehrte einzige Sohn des Großkaufmanns von Bhaddiya, der achthundert Millionen besaß. Er hatte für die drei Jahreszeiten drei Paläste und wohnte in jedem vier Monate. Wenn er in einem geweilt hatte, so zog er, von Tänzern umgeben, mit großer Pracht in einen andern Palast. Dann lief erregt die ganze Stadt zusammen, um die Pracht des Prinzen zu sehen; im Innern des Palastes stellte man Reihen an Reihen, Bank an Bank auf.

Nachdem aber der Meister drei Monate dort verweilt hatte, ließ er den Stadtbewohnern mitteilen, er wolle wegziehen. Die Städter sagten: „Gehet morgen, Herr!“ Sie luden den Meister ein, richteten am zweiten Tage für die Gemeinde mit Buddha, ihrem Haupte, ein großes Almosen her, errichteten inmitten der Stadt einen Pavillon, zierten ihn, ließen Sitze herrichten und verkündeten dann, es sei Zeit zum Mahle. Der Meister begab sich, umgeben von der Gemeinde der Mönche, dorthin und setzte sich nieder. Die Leute spendeten ein großes Almosen. Nach Beendigung des Mahles begann der Meister mit süßer Stimme die Danksagung.

In diesem Augenblicke zog gerade der Prinz Bhaddaji aus einem seiner Paläste in einen andern. An diesem Tage aber kam niemand, um sich seine Pracht anzusehen, sondern es umgaben ihn nur seine eigenen Leute. Da fragte er die Leute: „Zu einer andern Zeit läuft, wenn ich von einem Palast in den andern ziehe, erregt die ganze Stadt zusammen; man bildet Reihen auf Reihen und stellt Bank an Bank auf. Heute aber ist außer meinen eigenen Leuten niemand da; was ist schuld daran?“ Man antwortete ihm: „Gebieter, der völlig Erleuchtete, der drei Monate lang bei dieser Stadt geweilt hat, wird heute weggehen. Nachdem er sein Mahl beendigt, erklärt er der Volksmenge die Lehre; alle Bewohner der Stadt hören seiner Predigt zu.“ Darauf sagte der Jüngling: „Geht also, wir wollen ihn auch hören“; und mit all seinem Schmuck angetan ging er mit großem Gefolge hin und stellte sich an das Ende der Versammelten. Während er aber die Lehre hörte, warf er alle Befleckung von sich ab und gelangte zur höchsten Frucht, zur Heiligkeit.

Darauf sprach der Meister zu dem Großkaufmann von Benares: „O Großkaufmann, während dein Sohn in vollem Schmuck meine Predigt hörte, ist er zur Heiligkeit gelangt. Soll ich ihn zum Mönch machen und mit mir nehmen oder soll er zum völligen Nirvana eingehen?“ Der Großkaufmann erwiderte: „Herr, mein Sohn braucht noch nicht zum völligen Nirvana einzugehen. Macht ihn zum Mönch! Wenn er aber Mönch geworden, so nehmt ihn mit Euch und kommt morgen in unser Haus!“

Der Erhabene nahm die Einladung an, begab sich mit dem edlen Jüngling in das Kloster, machte ihn zum Mönch und ließ ihm die Weihe erteilen. Seine Eltern erwiesen ihm sieben Tage lang große Ehrung. Nachdem aber der Meister noch sieben Tage geblieben war, nahm er den edlen Jüngling mit sich und gelangte auf seiner Wanderung nach Kotigāma.

Die Bewohner von Kotigāma spendeten der Mönchsgemeinde mit Buddha, ihrem Haupte, ein großes Almosen. Nachdem das Mahl beendet war, begann der Meister seine Danksagung. Während aber die Danksagung verrichtet wurde, ging der edle Jüngling zum Dorfe hinaus; und indem er dachte: „Wenn der Meister kommt, will ich ihm aufwarten“, setzte er sich in der Nähe des Gangesufer an den Fuß eines Baumes und versank in Ekstase. Auch als alte Theras herbeikamen, stand er nicht auf; sondern er erhob sich erst, als der Meister kam. Die unbekehrten Mönche dachten: „Dieser sieht die alten Theras herankommen und steht nicht vor ihnen auf, als wenn er schon länger Mönch wäre als sie“; und sie wurden böse auf ihn.

Die Bewohner von Kotigama banden darauf Flöße zusammen. Nachdem dies geschehen, fragte der Meister: „Wo ist Bhaddaji?“ „Hier ist er, Herr.“ Der Meister sprach zu ihm: „Komm, Bhaddaji, besteige mit uns zusammen ein Schiff!“ Der Thera sprang auf und stellte sich auf ein Schiff. Als sie sich nun mitten auf dem Ganges befanden, fragte der Meister: „Bhaddaji, wo ist der Palast, den du zu der Zeit bewohntest, da du der große König Panāda warest?“ Er antwortete: „Er ist an dieser Stelle versunken, Herr.“ Nun sagten die unbekehrten Mönche: „Der Thera Bhaddaji zeigt seine Wunderkraft.“ — Darauf sagte der Meister: „Bhaddaji, löse also den Zweifel derer, die mit dir heiligen Wandel führen.“

In diesem Augenblick grüßte der Thera den Meister, ging vermöge seiner Wunderkraft hin, fasste den Stützpfeiler des Palastes mit dem Finger, nahm den fünfundzwanzig Yojanas messenden Palast und flog damit in die Luft empor. Als er aber in die Höhe geflogen war, zeigte er sich den unter dem Palaste Befindlichen, indem er eine Öffnung in den Palast machte. Ein, zwei und drei Yojanas hob er den Palast aus dem Wasser. Es hausten aber seine Verwandten aus dieser frühern Existenz aus Gier nach dem Palaste als Fische, Schildkröten, Schlangen und Frösche in diesem Palaste. Als nun der Palast in die Höhe stieg, drehten sie sich um und um und fielen ins Wasser. Da der Meister sie fallen sah, sagte er: „Bhaddaji, deine Verwandten sind in Not.“ Der Thera, der die Worte des Meisters gehört, ließ den Palast los und dieser sank wieder auf seinen frühern Platz.

Der Meister aber gelangte an das jenseitige Ufer des Ganges. Man richtete ihm am Gangesufer einen Sitz her und er ließ sich auf dem hergerichteten herrlichen Buddhasitze nieder, indem er Strahlen von sich entsandte wie die junge Sonne. Darauf fragten ihn die Mönche: „Zu welcher Zeit, Herr, war dieser Palast vom Thera Bhaddaji bewohnt?“ Der Meister erwiderte: „Zur Zeit des großen Königs Panāda“, und erzählte folgende Begebenheit aus der Vergangenheit.

§B. Ehedem war im Reiche Videha zu Mithila ein König namens Suruci. Dessen Sohn hieß auch Suruci; dieser aber hatte einen Sohn, der große Panāda [2a] mit Namen. Diese erhielten diesen Palast; um ihn aber zu erhalten, hatten sie früher einmal folgende Werke getan: Die beiden, Vater und Sohn, erbauten aus Rohr und Udumbara-Holz einem Paccekabuddha eine Laubhütte zum Wohnen usw.

§D. Die ganze Begebenheit aus der Vergangenheit in diesem Jataka wird im vierzehnten Buche im Suruci-Jataka erzählt werden.

§A2. Nachdem der Meister diese Begebenheit aus der Vergangenheit erzählt hatte, sprach er, der völlig Erleuchtete, folgende Strophen:

§1. „Panāda, so hieß jener König. Von reinem Gold war sein Palast; breit war er sechzehn Bogenschüsse, doch tausend seine Höh' betrug. §2. Aus hundert Stockwerken bestand er, fahnengeschmückt, smaragderstrahlend. Es tanzten dort von Musikanten sechstausend, siebenfach geteilt. §3. So schön war damals der Palast, von dem du redest, Bhaddaji. Ich selbst war damals der Gott Sakka und diente dir als Untergebner.“

In diesem Augenblicke wurden die unbekehrten Mönche von ihrem Zweifel befreit.

§C. Nachdem der Meister so die Lehre erklärt hatte, verband er das Jataka mit folgenden Worten: „Damals war der große Panāda Bhaddaji, Sakka aber war ich.“

Ende der Erzählung von Mahāpanāda"

[Quelle der Übersetzung: Jātakam : Das Buch der Erzählungen aus früheren Existenzen Buddhas / Aus dem Pali zum ersten Male vollständig ins Deutsche übers. von Julius Dutoit. -- Leipzig : Radellik Hille (Früher im Lotus-Verl., Leipzig), 1908 - 1921. -- 7 Bände. -- Online: http://www.palikanon.com/khuddaka/jataka/j264.htm. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-24]

9 Taṃ pāpuṇitvā Gaṅgāya jalaṃ pakkhalitaṃ idha

Bhikkhū asaddahantā naṃ satthuno naṃ nivedayuṃ.

9.

Wenn das Wasser des Ganges auf diesen Palst trifft, bildet es hier einen Strudel. Die Mönche, die ihm nicht glaubten, berichteten das dem Lehrer (Buddha).

10 Satthāha kaṅkhaṃ bhikkhūnaṃ vinodehī ti, so tato

Ñāpetuṃ brahmaloke pi vasavattisamatthataṃ

11 Iddhiyā nabham uggantvā sattatālasame ṭhito

Dussathūpaṃ Brahmaloke ṭhapetvā vaḍḍhite kare

12 Idhānetvā dassayitvā janassa puna taṃ tahiṃ

Ṭhapayitvā yathāṭhāne iddhiyā Gaṅgam ogato

13 Pādaṅguṭṭhena pāsādaṃ gahetvā thūpikāya so

Ussāpetvāna dassetvā janassa khipi taṃ tahiṃ

10. - 13.

Der Lehrer (Buddha) sagte ihm, er solle die Zweifel der Mönche zerstreuen. Um zu zeigen, dass er selbst in der Brahmawelt1 Macht hatte, ist er durch seine Wundermacht in die Luft aufgestiegen und blieb in der Höhe von sechs Palmyrapalmlängen2 stehen, nahm den Dussa-Stūpa3 in der Brahmawelt in seine angewachsene Hand, brachte diesen Stūpa her, zeigte ihn den Leuten und stellte ihn wieder an seinen Platz. Dann tauchte er mit seiner Wundermacht in den Ganges, ergriff seinen Palast mit seiner großen Zehe an der Turmspitze, hob ihn aus dem Wasser heraus, zeigte ihn den Leuten und warf ihn wieder ins Wasser.

Kommentar:

1 Brahmawelt

"Brahmloka The highest of the celestial worlds, the abode of the Brahmas. It consists of twenty heavens:

- the nine ordinary Brahma-worlds,

- the five Suddhāvāsā,

- the four Arūpa worlds (see loka),

- the Asaññasatta and

- the Vehapphala (e.g., VibhA.521).

All except the four Arūpa worlds are classed among the Rūpa worlds (the inhabitants of which are corporeal). The inhabitants of the Brahma worlds are free from sensual desires (but see the Mātanga Jātaka, (J.497), where Ditthamangalikā is spoken of as Mahābrahmabhariyā, showing that some, at least, considered that Mahābrahmas had wives).

The Brahma world is the only world devoid of women (DhA.i.270); women who develop the jhānas in this world can be born among the Brahmapārisajjā (see below), but not among the Mahābrahmas (VibhA.437f). Rebirth in the Brahma world is the result of great virtue accompanied by meditation (Vsm.415). The Brahmas, like the other celestials, are not necessarily sotāpanna or on the way to complete knowledge (sambodhi-parāyanā); their attainments depend on the degree of their faith in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha. See, e.g., A.iv.76f.; it is not necessary to be a follower of the Buddha for one to be born in the Brahma world; the names of six teachers are given whose followers were born in that world as a result of listening to their teaching (A.iii.371ff.; iv.135ff.).The Jātakas contain numerous accounts of ascetics who practised meditation, being born after death in the Brahma world (e.g., J.ii.43, 69, 90; v.98, etc.). Some of the Brahmas - e.g., Baka - held false views regarding their world, which, like all other worlds, is subject to change and destruction (M.i.327). When the rest of the world is destroyed at the end of a kappa, the Brahma world is saved (Vsm.415; KhpA.121), and the first beings to be born on earth come from the Ābhassara Brahma world (Vsm.417). Buddhas and their more eminent disciples often visit the Brahma worlds and preach to the inhabitants. E.g., M.i.326 f.; ThagA.ii.184ff.; Sikhī Buddha and Abhibhū are also said to have visited the Brahma world (A.i.227f.). The Buddha could visit it both in his mind made body and his physical body (S.v.282f.).

If a rock as big as the gable of a house were to be dropped from the lowest Brahma-world it would take four months to reach the earth travelling one hundred thousand leagues a day. Brahmas subsist on trance, abounding in joy (sappītikajjhāna), this being their sole food. SA.i.161; food and drinks are offered to Mahābrahmā, and he is invited to partake of these, but not of sacrifices (SA.i.158 f.). Anāgāmins, who die before attaining arahantship, are reborn in the Suddhāvāsā Brahma-worlds and there pass away entirely (see, e.g., S.i.35, 60, and Compendium v.10). The beings born in the lowest Brahma world are called Brahma-pārisajjā; their life term is one third of an asankheyya kappa; next to them come the Brahma-purohitā, who live for half an asankheyya kappa; and beyond these are the Mahā Brahmas who live for a whole asankheyya kappa (Compendium, v.6; but see VibhA.519f., where Mahā Brahmās are defined).The term Brahmakāyikā-devā seems to be used as a class-name for all the inhabitants of the Brahma-worlds (A.i.210; v.76f).

The Mahā Niddesa Commentary (p.109) says that the word includes all the five (?) kinds of Brahmā (sabbe pi pañca vokāra Brahmāno gahitā).

The BuA.p.10 thus defines the word Brahmā: brūhito tehi tehi gunavisesahī ti=Brahmā. Ayam pana Brahmasaddo Mahā-Brahma-brāhmana-Thathāgata mātāpitu-setthādisu dissati.

The Samantapāsādikā (i.131) speaks of a Mahā Brahmā who was a khināsava, living for sixteen thousand kappas. When the Buddha, immediately after his birth, looked around and took his steps northward, it was this Brahmā who seized the babe by his finger and assured him that none was greater than he.

The names of several Brahmās occur in the books - e.g.,

- Tudu

- Nārada

- Ghatikāra

- Baka

Sanankumāra- Sahampatī

To these should be added the names of seven Anāgāmīs resident in Avihā and other Brahma worlds

- Upaka

- Phalagandu

- Pukkusāti

- Bhaddiya

- Khandadeva

- Bāhuraggi

Pingiya(S.i.35, 60; SA.i.72 etc.).

Baka speaks of seventy two Brahmās, living, apparently, in his world, as his companions (S.i.142).

See also Tissa Brahmā.

These are described as Mahā Brahmās. Mention is also made of Pacceka Brahmās - e.g., Subrahmā and Suddhavāsa (S.i.146f).Tudu is also sometimes described as a Pacceka Brahmā (e.g., S.i.149). Of the Pacceka Brahmās, Subrahmā and Suddhavāsa are represented as visiting another Brahmā, who was infatuated with his own power and glory, and as challenging him to the performance of miracles, excelling him therein and converting him to the faith of the Buddha. Tudu is spoken of as exhorting Kokālika to put his trust in Sāriputta and Moggallāna (Loc. Cit.)

No explanation is given of the term Pacceka Brahmā. Does it mean Brahmās who dwelt apart, by themselves? Cp. Pacceka-Buddha.

The Brahmās are represented as visiting the earth and taking an interest in the affairs of men. Thus, Nārada descends from the Brahma-world to dispel the heresies of King Angati (J.vi.242f). When the Buddha hesitates to preach his doctrine, because of its profundity, it is Sahampati who visits him and begs him to preach it for the welfare of the world. The explanation given (e.g., at SA.i.155) is that the Buddha waited for the invitation of Sahampati that it might lend weight to his teaching. The people were followers of Brahmā, and Sahampati's acceptance of the Buddha's leadership would impress them deeply.

Sahampatī is mentioned as visiting the Buddha several times subsequently, illuminating Jetavana with the effulgence of his body. It is said that with a single finger he could illuminate a whole Cakkavāla (SA.i.158). Sanankumāra was also a follower of the Buddha. The Brahmās appear to have been in the habit of visiting the deva worlds too, for Sanankumāra is reported as being present at an assembly of the Tāvatimsa gods and as speaking there the Buddha's praises and giving an exposition of his teaching. But, in order to do this, he assumed the form of Pañcasikha (D.ii.211ff).The books refer (e.g., at D.i.18, where Brahmā is

described as vasavattī issaro kattā nimmātā, etc.) to the view held, at the Buddha's time, of Brahmā as the creator of the universe and of union with Brahmā as the highest good, only to be attained by prayers and sacrifices. But the Buddha himself did not hold this view amid does not speak of any single Brahmā as the highest being in all creation. See, however, A.v.59f., where Mahā Brahmā, is spoken of as the highest denizen of the Sahassalokadhātu (yāvatā sahassalokadhātu, Mahā-Brahmā tattha aggam akkhāyati); but he, too, is impermanent (Mahā-Brahmūno pi . . . atthi eva aññathattam, atthi viparināmo).

There are Mahā Brahmās, mighty and powerful (abhibhū anabhibhūto aññadatthudaso vasavattī), but they too, all of them, and their world are subject to the laws of Kamma. E.g., at S.v.410 (Brahmaloko pi āvuso anicco adhuvo sakkāyapariyāpanno sādhāyasmā Brahmalokā cittam vutthāpetvā sakkāyanirodhacittam upasamharāhi). See also A.iv.76f., 104f., where Sunetta, in spite of all his great powers as Mahā Brahmā, etc., had to confess himself still subject to suffering.

To the Buddha, union with Brahmā seems to have meant being associated with him in his world, and this can only be attained by cultivation of those qualities possessed by the Brahmā. But the highest good lay beyond, in the attainment of Nibbāna. Thus in the Tevijjā Sutta; see also M.ii.194f.

The word Brahma is often used in compounds meaning highest and best - e.g., Brahmacariyā, Brahmassara; for details see Brahma in the New Pāli Dictionary."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

2 Palmyrapalmlängen: Borassus flabellifer, wird bis 30 m hoch. 7 Palmyrapalmlängen = ca. 210 m.

Abb.: Palmyrapalme - Borassus flabellifer

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia]3 Dussa-Stūpa

"Dussa-thūpa A thūpa built in the Brahma-world by Ghatīkāra, enshrining the garments worn by the Buddha at the time of his Renunciation.

It was built of gems and was twelve yojanas high (Dāthāvamsa, vs.35).

Among the wonders performed by Bhaddaji one was to carry it on his outstretched palm and show it to the multitude. Mhv.xxxi.11; MT.562."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

14 Nanduttaro māṇavako disvā taṃ pāṭihāriyaṃ

Parāyattam ahaṃ dhātuṃ pahū ānayituṃ siyaṃ

15 Iti patthayi; tenetaṃ saṅgho Soṇuttaraṃ yatiṃ

Tasmiṃ kamme niyojesi soḷasavassikaṃ api.

14. - 15.

Als der junge Brahmane Nanduttara1 dieses Wunder sah, wünschte er sich, fähig zu sein, eine Reliquie, die im Besitz anderer ist, heranzubringen. Deswegen hat die Mönchsgemeinde den Asketen Soṇuttara mit dieser Aufgabe betraut, obwohl er erst sechzehn Regenzeiten2 lang Mönch war.

Kommentar:

1 Nanduttara = frühere Existenz von Soṇuttara zur Zeit Buddhas.

2 da er in Vers 16 als Thera bezeichnet wird, kann es nicht heißen "16 Jahre alt", denn dann wäre er nur Novize.

16 Āharāmi kuto dhātuṃ

iti saṅgham apucchi so.

Kathesi saṅgho therassa tassa tā dhātuyo iti:

16.

Er fragte, wo er eine Reliquie herholen solle. Die Mönchsgemeinde beschrieb dem Thera die Reliquien so:

17 Parinibbaṇamañcamhi nipanno lokanāyako

Dhātūhi pi lokahitaṃ kātuṃ devindam abravi:

17.

"Als der Führer der Welt (Buddha) auf dem Bett des Vollkommenen Erlöschens lag, sprach er zum Götterkönig1, um mit Reliquien Heil der Welt zu bewirken:

Kommentar:

1 Götterkönig: Sakka

18 Devindaṭṭhasu doṇesu mama sārīradhātusu

Ekaṃ doṇaṃ Rāmagāme Koḷiyehi ca sakkataṃ

19 Nāgalokaṃ tato nītaṃ, tattha nāgehi sakkataṃ,

Laṅkādīpe Mahathūpe nidhānāya bhavissati.

18. - 19.

"Götterkönig, von den acht Doṇa1 von meinen Körperreliquien2, wird das Doṇa, das in Rāmagāma3 bei den Koḷiyā4 verehrt wird und von dortin die Welt der Nāga5 gebracht und dort von den Nāga verehrt wird, für die Aufbewahrung im Mahāthūpa auf der Insel Laṅkā bestimmt sein."

Kommentar:

1 Doṇa: Trog = ein Hohlmaß = ca. 4 bis 5 Liter, 8 Doṇa = 30 bis 40 Liter!

2 Körperreliquien (sāriradhatu): im Unterschied zu Gebrauchsgegenstände-Reliquien (pāribhoga-dhātu) Vergleiche die katholische Klassifikation von Reliquien:

"Im Katholizismus werden drei Reliquienklassen unterschieden: Eine Sonderstellung außerhalb dieses Schemas kommt den biblischen Reliquien zu, also denjenigen Gegenständen, die mit dem neutestamentlichen Heilsgeschehen, insbesondere mit Jesus und Maria in direkte Verbindung gebracht werden. Dazu zählen vor allem die Kreuzreliquien, kleine Holzsplitter vom Kreuz Christi, von denen viele tausend über die ganze Welt verteilt in katholischen und orthodoxen Kirchen verehrt werden. Zu den Passionsreliquien, die Bezüge zur Passion, also zur Leidensgeschichte Jesu in seinen letzten Lebenstagen aufweisen, gehören daneben auch die berühmte Heilige Lanze des Longinus, Partikel der Kreuznägel zum Beispiel in der Eisernen Krone, Partikel der Dornenkrone und der anderen Marterwerkzeuge, ferner das Turiner Grabtuch, das Schweißtuch der Veronika und der Gral. In ähnlicher Weise werden Gewänder verehrt, die Maria und Jesus zu Lebzeiten getragen haben sollen, etwa der Heilige Rock in Trier, die Sandalen Jesu in Prüm, die Gewänder und der Schleier Mariae, sowie Windel und Lendenschurz Jesu in Aachen.

- Reliquien erster Klasse sind alle Körperteile des Heiligen, insbesondere Partikel seiner Knochen, aber auch seine Haare, Fingernägel und, soweit erhalten, sonstigen Überreste, ins selteneren Fällen auch Blut. Bei Heiligen, deren Körper verbrannt wurden, gilt gegebenenfalls die Asche als Reliquie erster Klasse.

- Reliquien zweiter Klasse, auch echte Berührungsreliquien genannt, sind Gegenstände, die der Heilige zu seinen Lebzeiten berührt hat, insbesondere Objekte von besonderer biographischer Bedeutung. Dazu gehören etwa bei heilig gesprochenen Priestern und Mönchen ihre sakralen Gewänder, bei Märtyrern beispielsweise die Foltergeräte und Waffen, durch die sie ums Leben kamen.

- Reliquien dritter Klasse oder mittelbare Berührungsreliquien sind Gegenstände, die Reliquien erster Klasse berührt haben. Solche Objekte, in der Regel kleine Papier- oder Stoffquadrate, die kurz auf die Reliquien gelegt und hinterher auf Heiligenbildchen geklebt werden, werden in vielen katholischen Wallfahrtsorten besonders in Südeuropa bis heute als Souvenirs an Pilger verkauft.

Da Jesus nach biblischer und Maria nach katholischer Ansicht in den Himmel entrückt wurden und daher von ihnen keine Leichname existieren, war die Frage, ob es von ihnen Reliquien erster Klasse geben könne, theologisch zeitweise sehr umstritten. Die in Kirchenschätzen erhaltenen angeblichen Reliquien der abgeschnittenen Haare und Fingernägel, der Milchzähne, Nabelschnur und Heilige Vorhaut Jesu werden heute überwiegend als mittelalterliche Fälschungen angesehen und von der katholischen Kirche nicht mehr in besonderer Weise verehrt.

Die Klasseneinteilung der Reliquien hat vor allem kirchenrechtliche Bedeutung: das kanonische Recht verbietet Katholiken den Handel mit biblischen Reliquien sowie Reliquien erster und zweiter Klasse. Katholiken dürfen solche Objekte zwar von nicht katholischen Dritten oder von dazu offiziell befugten kirchlichen Einrichtungen erwerben, besitzen und privat verehren, aber nicht weiterverkaufen. Zulässig sind lediglich das Verschenken von Reliquien an andere Gläubige und die Rückgabe an die Kirche. Im Mittelalter war der Reliquienhandel (ebenso wie das 'Handwerk' der Reliquienfälschung) hingegen weit verbreitet."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reliquie. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-24]

3 Rāmagāma: Nach Cunningham vermutlich heutiges Deokali, das nicht am Ganges liegt

"Rāmagāma A Koliyan village on the banks of the Ganges.

Its inhabitants claimed and obtained a share of the Buddha's relics, over which they erected a thūpa (D.ii.167; Bu.xxviii.3; Dvy.380).

This thūpa was later destroyed by floods, and the urn, with the relics, was washed into the sea. There the Nāgas, led by their king, Mahākāla, received it and took it to their abode in Mañjerika where a thūpa was built over them, with a temple attached, and great honour was paid to them.

When Dutthagāmani built the Mahā Thūpa and asked for relics to be enshrined therein, Mahinda sent Sonuttara to the Nāga world to obtain these relics, the Buddha having ordained that they should ultimately be enshrined in the Mahā Thūpa. But Mahākāla was not willing to part with them, and Sonuttara had to use his iddhi power to obtain them. A few of the relics were later returned to the Nāgas for their worship. For details see Mhv.xxxi.18ff."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

"Rāmagrāma.

From Kapila both pilgrims proceeded to Lan-mo, which has been identified with the Rāmagrāma of the Buddhist chronicles of India. Fa-Hian [法顯] makes the distance 5 yojanas, or 35 miles, to the east, and Hwen Thsang [玄奘] gives 200 li, or 33 1/3 miles, in the same direction. But in spite of their agreement I believe that the distance is in excess of the truth. Their subsequent march to the bank of the Anoma river is said to be 3 yojanas or 21 miles by Fa-Hian, and 100 li or 16 2/3 miles by Hwen Thsang, thus making the total distance from Kapila to the Anoma river 8 yojanas, or 56 miles, according to the former, and 300 li, or 50 miles, according to the latter. But in the Indian Buddhist scriptures, this distance is said to be only 6 yojanas, or 42 miles, which I believe to be correct, as the Aumi river of the present day, which is most probably the Anoma river of the Buddhist books, is just 40 miles distant from Nagar in an easterly direction. The identification of the Anoma will be discussed presently.

According to the pilgrims' statements, the position of Rāmagrāma must be looked for at about two-thirds of the distance between Nagar and the Anoma river, that is at 4 yojanas, or 28 miles. In this position I find the village of Deokali with a mound of ruins, which was used as a station for the trigonometrical survey. In the 'Mahawanso' it is stated that the stūpa of Rāmagāmo, which stood on the bank of the Ganges, was destroyed by the action of the current. Mr. Laidlay has already pointed out that this river could not be the Ganges; but might be either the Ghagra, or some other large river in the north. But I am inclined to believe that the Ganges is a simple fabrication of the Ceylonese chronicler. All the Buddhist scriptures agree in stating that the relics of Buddha were divided into eight portions, of which one fell to the lot of the Kosalas of Rāmagrāma, over which they erected a stūpa. Some years later seven portions of the relics were collected together by Ajātaśatru, king of Magadha, and enshrined in a single stūpa at Rājagriha; but the eighth portion still remained at Rāmagrāma. According to the Ceylonese chronicler, the stūpa of Ramagrama was washed away by the Ganges, and the relic casket, having been carried down the river to the ocean, was discovered by the Nāgas, or water gods, and presented to their king, who built a stūpa for its reception. During the reign of Duṭṭhagāmini of Ceylon, 3.C. 161 to 137, the casket was miraculously obtained from the Nāga king by the holy monk Soṇuttaro, and enshrined in the Mahāthūpo, or "great stūpa " in the land of Lanka.

Now this story is completely at variance wi»h the statements of the Chinese pilgrims, both of whom visited Rāmagrāma many centuries after Duṭṭha-gāmini, when they found the relic stupa intact, but no river. Fa-Hian, in the beginning of the fifth century, saw a tank beside the stupa, in which a dragon (Nāga) lived, who continually watched the tower. In the middle of the seventh century, Hwen Thsang saw the same stupa and the same tank of clear water inhabited by dragons (Nāgas), who daily transformed themselves into men and paid their devotions to the stupa. Both pilgrims mention the attempt of Asoka to remove these relics to his own capital, which was abandoned on the expostulation of the Nāaga king. "If by thy oblations," said the Nāga, "thou canst excel this, thou mayest destroy the tower, and I shall not prevent thee." Now according to the Ceylonese chronicler, this is the very same argument that was used by the Nāga king to dissuade the priest Soṇuttaro from removing the relics to Ceylon. I infer, therefore, that the original "tank" of Rāmagrāma was adroitly changed into a river by the Ceylonese author, so that the relics which were in charge of the Nāgas of the tank, might be conveyed to the ocean-palace of the Nāga king, from whence they could as readily be transferred to Ceylon as to any other place. The river was thus a necessity in the Ceylonese legend, to convey the relics away from Rāmagrāma to the ocean. But the authority of a legend can have no weight against the united testimony of the two independent pilgrims, who many centuries later found the stupa still standing, but saw no river. I therefore dismiss the Ganges as a fabrication of the Ceylonese chroniclers, and accept in its stead the Nāga tank of the Chinese pilgrims. Having thus got rid of the river, I can see no objection to the identification of Deokali with the Rāmagrāma of Buddhist history. The town was quite deserted at the time of Fa-Hian's visit, in the fifth century, who found only a small religious establishment; this was still kept up in the middle of the seventh century, but it must have been very near its dissolution, as there was only a single srāmaṇera, or monk, to conduct the affairs of the monastery."[Quelle: Cunningham, Alexander <1814 - 1893>: The ancient geography of India / ed. with introduction ande notes by Surendranath Majumdar Sastri. -- New. ed. -- Calcutta : Chuckervertty, Chatterjee & Co., 1924. -- 770 S. : Ill. -- S. 482 - .]

4 Koḷiyā

"Koḷiyā One of the republican clans in the time of the Buddha.

The Koliyā owned two chief settlements - one at Rāmagāma and the other at Devadaha. The Commentaries (DA.i.260f; SNA.i.356f; A.ii.558; ThagA.i.546; also Ap.i.94) contain accounts of the origin of the Koliyas. We are told that a king of Benares, named Rāma (the Mtu.i.353 calls him Kola and explains from this the name of the Koliyas), suffered from leprosy, and being detested by the women of the court, he left the kingdom to his eldest son and retired into the forest. There, living on woodland leaves and fruits, he soon recovered, and, while wandering about, came across Piyā, the eldest of the five daughters of Okkāka, she herself being afflicted with leprosy. Rāma, having cured her, married her, and they begot thirty-two sons. With the help of the king of Benares, they built a town in the forest, removing a big kola-tree in doing so. The city thereupon came to be called Kolanagara, and because the site was discovered on a tiger-track (vyagghapatha) it was also called Vyagghapajjā. The descendants of the king were known as Koliyā.According to the Kunālā Jātaka (J.v.413), when the Sākyans wished to abuse the Koliyans, they said that the Koliyans had once "lived like animals in a Kola-tree," as their name signified. The territories of the Sākiyans and the Koliyans were adjacent, separated by the river Rohinī. The khattiyas of both tribes intermarried, and both claimed relationship with the Buddha. (It is said that once the Koliyan youths carried away many Sākiyan maidens while they were bathing, but the Sākiyans, regarding the Koliyans as relatives, took no action; DA.i.262). A quarrel once arose between the two tribes regarding the right to the waters of the Rohinī, which irrigated the land on both sides, and a bloody feud was averted only by the intervention of the Buddha. In gratitude, each tribe dedicated some of its young men to the membership of the Order, and during the Buddha's stay in the neighbourhood, he lived alternately in Kapilavatthu and in Koliyanagara. (For details of this quarrel and its consequences see J.v.412ff; DA.ii.672ff; DhA.iii.254ff).

Attached probably to the Koliyan central authorities, was a special body of officials, presumably police, who wore a distinguishing headdress with a drooping crest (Lambacūlakābhatā). They bore a bad reputation for extortion and violence (S.iv.341).

Besides the places already mentioned, several other townships of the Koliyans, visited by the Buddha or by his disciples, are mentioned in literature - e.g.,

- Uttara, the residence of the headman Pātaliya (S.iv.340);

Sajjanela, residence of Suppavāsā (A.ii.62);- Sāpūga, where Ananda once stayed (A.ii.194);

- Kakkarapatta, where lived Dīghajānu (A.iv.281); and

- Haliddavasana, residence of the ascetics Punna Koliyaputta and Seniya (M.i.387; see also S.v.115).

Nisabha (ThagA.i.318), Kakudha (SA.i.89) (attendant of Moggallāna), and Kankhā-Revata (Ap.ii.491) (and perhaps Sona Kolivisa, q.v.), were also Koliyans.

After the Buddha's death the Koliyans of Rāmagāma claimed and obtained one-eighth of the Buddha's relics, over which they erected a thūpa (D.ii.167; Mhv.xxi.18, 22ff). See also s.v. Suppavāsā."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

5 Nāgā (Chinesisch: 蛇精; Japanisch: ナーガ)

Abb.: Nāga-Kultstätte in Kanchipuram (tamil காஞ்சிபுரம), Tamil Nadu, Indien

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"Nāgā A class of beings classed with Garulas and Supannas and playing a prominent part in Buddhist folk lore. They are gifted with miraculous powers and great strength. Generally speaking, they are confused with snakes, chiefly the hooded Cobra, and their bodies are described as being those of snakes, though they can assume human form at will. They are broadly divided into two classes: those that live on land (thalaja) and those that live on water (jalaja). The Jalaja-nāgā live in rivers as well as in the sea, while the Thalaja-nāgā are regarded as living beneath the surface of the earth. Several Nāga dwellings are mentioned in the books: e.g.,

- Mañjerika-bhavana under Sineru,

- Daddara-bhavana at the foot of Mount Daddara in the Himālaya,

- the Dhatarattha-nāgā under the river Yamunā,

- the Nābhāsā Nāgā in Lake Nabhasa,

- and also the Nāgas of Vesāli, Tacchaka, and Payāga (D.ii.258).

The Vinaya (ii.109) contains a list of four royal families of Nāgas (Ahirājakulāni): Virūpakkhā, Erāpathā, Chabyāputtā and Kanhagotamakā. Two other Nāga tribes are generally mentioned together: the Kambalas and the Assataras. It is said (SA.iii.120) that all Nāgas have their young in the Himālaya.

Stories are given - e.g., in the Bhūridatta Jātaka - of Nāgas, both male and female, mating with humans; but the offspring of such unions are watery and delicate (J.vi.160). The Nāgas are easily angered and passionate, their breath is poisonous, and their glance can be deadly (J.vi.160, 164). They are carnivorous (J.iii.361), their diet consisting chiefly of frogs (J.vi.169), and they sleep, when in the world of men, on ant hills (ibid., 170). The enmity between the Nāgas and the Garulas is proverbial (D.ii.258). At first the Garulas did not know how to seize the Nāgas, because the latter swallowed large stones so as to be of great weight, but they learnt how in the Pandara Jātaka. The Nāgas dance when music is played, but it is said (J.vi.191) that they never dance if any Garula is near (through fear) or in the presence of human dancers (through shame).The best known of all Nāgas is Mahākāla, king of Mañjerika-bhavana. He lives for a whole kappa, and is a very pious follower of the Buddha. The Nāgas of his world had the custodianship of a part of the Buddha's relics till they were needed for the Māha Thūpa (Mhv.xxxi.27f.), and when the Bodhi tree was being brought to Ceylon they did it great honour during the voyage (Mbv. p.. 163f.). Other Nāga kings are also mentioned as ruling with great power and majesty and being converted to the Buddha's faith - e.g., Aravāla, Apalālā, Erapatta, Nandopananda, and Pannaka. (See also Ahicchatta and Ahināga.) In the Atānātiya Sutta (D.iii.198f.), speaking of dwellers of the Cātummahārajika world, the Nāgas are mentioned as occupying the Western Quarter, with Virūpokkha as their king.

The Nāgas had two chief settlements in Ceylon, in Nāgadīpa (q.v.) and at the mouth of the river Kalyānī. It was to settle a dispute between two Nāga chiefs of Nāgadīpa, Mahodara and Cūlodara, that the Buddha paid his second visit to Ceylon. During that visit he made a promise to another Nāga-king, Manjakkhika of Kalyānī, to pay him a visit, and the Buddha's third visit was in fulfilment of that undertaking (Mhv.i.48f.).

The Nāgas form one of the guards set up by Sakka in Sineru against the Asuras (J.i.204). The Nāgas were sometimes worshipped by human beings and were offered sacrifices of milk, rice, fish, meat and strong drink (J.i.497f.). The jewel of the Nāgas is famous for its beauty and its power of conferring wishes to its possessor (J.vi.179, 180).

The word Nāga is often used as an epithet of the Buddha and the Arahants, and in this connection the etymology given is āgum na karotī ti Nāgo (e.g., MNid.201). The Bodhisatta was born several times as king of the Nāgas: Atula, Campeyya, Bhūridatta, Mahādaddara, and Sankhapāla.

In the accounts given of the Nāgas, there is undoubtedly great confusion between the Nāgas as supernatural beings, as snakes, and as the name of certain non Aryan tribes, but the confusion is too difficult to unravel."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

"Nāga (नाग) is the Sanskrit and Pāli word for a minor deity taking the form of a very large snake, found in Hindu and Buddhist mythology. The use of the term nāga is often ambiguous, as the word may also refer, in similar contexts, to one of several human tribes known as or nicknamed "Nāgas"; to elephants; and to ordinary snakes, particularly the King Cobra and the Indian Cobra, the latter of which is still called nāg in Hindi and other languages of India. A female nāga is a nāgī. Nagas in Hinduism

Stories involving the nāgas are still very much a part of contemporary cultural traditions in predominantly Hindu regions of Asia (India, Nepal, and the island of Bali). In India, nāgas are considered nature spirits and the protectors of springs, wells and rivers. They bring rain, and thus fertility, but are also thought to bring disasters such as floods and drought. According to some traditions nāgas are only malevolent to humans when they have been mistreated. They are susceptible to mankind's disrespectful actions in relation to the environment. Since nāgas have an affinity with water, the entrances to their underground palaces are often said to be hidden at the bottom of wells, deep lakes and rivers. They are especially popular in southern India where some believe that they brought fertility to their venerators. Some believed that the legends of nāgas may have originated with some kind of tribal people in the past.

Varuna, the Vedic god of storms, is viewed as the King of the nāgas. nāgas live in Pātāla, the seventh of the "nether" dimensions or realms. They are children of Kashyapa and Kadru. Among the prominent nāgas of Hinduism are Manasa, Shesha or Śeṣa and Vasuki.The nāgas also carry the elixir of life and immortality. One story mentions that when the gods were rationing out the elixir of immortality, the nāgas grabbed a cup. The gods were able to retrieve the cup, but in doing so, spilled a few drops on the ground. The nāgas quickly licked up the drops, but in doing so, cut their tongues on the grass, and since then their tongues have been forked.

The name of the Indian city Nagpur (Marathi: नागपुर) is derived from Nāgapuram, literally, "city of nāgas".

Nāgas in BuddhismTraditions about nāgas are also very common in all the Buddhist countries of Asia. In many countries, the nāga concept has been merged with local traditions of large and intelligent serpents or dragons. In Tibet, the nāga was equated with the klu (pronounced lu), spirits that dwell in lakes or underground streams and guard treasure. In China, the nāga was equated with the lóng or Chinese dragon (Traditional Chinese: 龍; Simplified Chinese: 龙)

The Buddhist nāga generally has the form of a large cobra-like snake, usually with a single head but sometimes with many. At least some of the nāgas are capable of using magic powers to transform themselves into a human semblance. In Buddhist painting, the nāga is sometimes portrayed as a human being with a snake or dragon extending over his head.

Nāgas both live on Mount Sumeru, among the other minor deities, and in various parts of the human-inhabited earth. Some of them are water-dwellers, living in rivers or the ocean; others are earth-dwellers, living in underground caverns. Some of them sleep on top of anthills. Their food includes frogs.

In Buddhism, the nāgas are the enemies of the Garuḍas, minor deities resembling gigantic eagles, who eat them. They learned how to keep from being devoured by the Garuḍas by eating large stones, which made them too heavy to be carried off by the Garuḍas.The nāgas are the servants of Virūpākṣa (Pāli: Virūpakkha), one of the Four Heavenly Kings who guards the western direction. They act as a guard upon Mount Sumeru, protecting the devas of Trāyastriṃśa from attack by the Asuras.

Among the notable nāgas of Buddhist tradition is Mucalinda, protector of the Buddha.

Other Naga traditionsFor Malay sailors, nāgas are a type of dragon with many heads; in Thailand and Java, the naga is a wealthy underworld deity. In Laos they are beaked water serpents.

Abb.: Nāga, Wat Sisaket, Vientiane (ວຽງຈັນ), Laos (ລາວ)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]Nagas in Cambodia

In a Cambodian legend, the nāga were a reptilian race of beings who possessed a large empire or kingdom in the Pacific Ocean region. The Nāga King's daughter married the king of Ancient Cambodia, and thus gave rise to the Cambodian people. This is why, still, today, Cambodians say that they are "Born from the Nāga". The Seven-Headed Nāga serpents depicted as statues on Cambodian temples, such as Angkor Wat, apparently represent the 7 races within Nāga society, which has a mythological, or symbolic, association with "the seven colours of the rainbow". Furthermore, Cambodian Nāga possess numerological symbolism in the number of their heads. Odd-headed Nāga symbolise the Male Energy, Infinity, Timelessness, and Immortality. This is because, numerologically, all odd numbers come from One (1). Even-headed Nāga are said to be "Female, representing Physicality, Mortality, Temporality, and the Earth."

Nagas in NagalandThe Naga people of Nagaland are said to have believed themselves to be descendants of the mythological "Nāgas", but to have lost this belief due to Christian missionary activity."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naga_%28mythology%29. -- Zugriff am 2006-07-24]

20 Mahākassapathero pi dīghadassī mahāmati

Dhammāsokanarindena dhātuvitthārakāraṇā

21 Rājagahassa sāmante rañño Ajātasattuno

Kārāpento mahādhātunidhānaṃ sādhu saṅkhataṃ

22 Sattadoṇāni dhātūnaṃ āharitvāna kārayi;

Rāmagāmamhi doṇan tu satthucittaññu naggahi.

20. - 22.