Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 3. Inschriften. -- Fassung vom 2008-07-09. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen03.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2008-03-10

Überarbeitungen: 2008-07-09 [Ergänzungen]; 2008-03-20 [Ergänzungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Der weitaus überwiegende Teil unseres Wissens über die Geschichte Indiens vor ca. 1000 n. Chr. hat als Quelle Inschriften.

Richard Salomon schreibt zurecht:

"It is mainly for these reasons that epigraphy is a primary rather than a secondary subfield within Indology. Whereas in classical studies or Sinology, for example, epigraphy serves mainly as a corroborative and supplementary source to historical studies based mainly on textual sources, in India the situation is precisely the opposite. There, history is built upon a skeleton reconstructed principally from inscriptions, while literary and other sources usually serve only to add some scraps of flesh here and there to the bare bones. There are, of course, some exceptions to the rule, most notably in Kashmir, where unlike nearly everywhere else in India a sophisticated tradition of historical writing flourished, best exemplified by Kalhaṇa's Rājataraṅgiṇī. Nonetheless, the general pattern remains essentially valid for political, and to a lesser extent for cultural, history." [Quelle: Salomon, Richard <1948 - >: Indian epigraphy : a guide to the study of inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan languages -- New York : Oxford University Press, ©1998. -- 378 S. : Ill. ; 24 cm. -- ISBN: 0195099842. -- S. 4.]

Man schätzt, dass allein in Indien (ohne Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal und Sri Lanka) bisher ca. 90.000 Inschriften gefunden wurden, davon sind ca. 58.000 veröffentlicht. Hinzu kommen noch Inschriften in Zentralasien, Südostasien, China, Ägypten.

Man kennt entzifferte Inschriften ab dem 4.(?)/3. Jhdt v. Chr. Häufig werden Inschriften ab ca. dem 8. Jhdt. n. Chr. Die meisten dieser späteren Inschriften befinden sich in Südindien:

Zu den Schreibmaterialien und Schreibmethoden für Manuskripte siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Einführung in die Exegese von Sanskrittexten : Skript. -- Kap. 3: Textkritik und Textgeschichte. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/exegese/exeg03.htm

Beispiele:

Abb.: Aśoka-Säule in Lumbini

[Bildquelle: Prince Roy. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/princeroy/97931135/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-01.

--

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

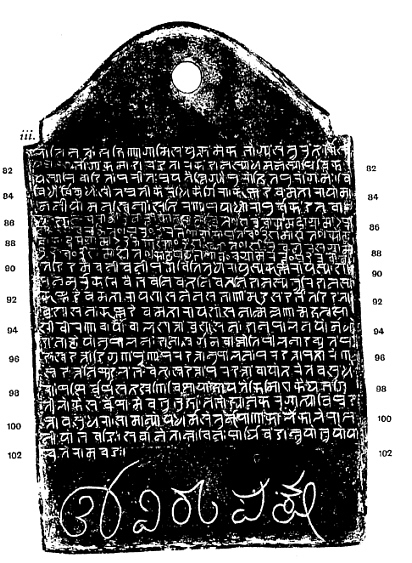

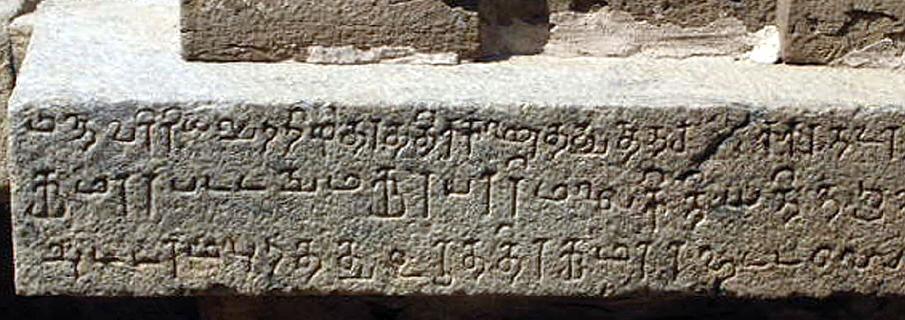

Abb.: Tamil-Inschrift in Vaṭṭeṛuttu-Schrift auf Steinstele,

Peruneyil bei Changanachery (ചങ്ങനാശ്ശേരി), Kerala, ca. 11.12.Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 18 (1925/26). -- Nach S. 344]

Abb.: Satī-Gedenkstätte, Junagarh Fort, Bikaner (बीकानेर), Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: abrinsky. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/abrinsky/433361258/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-10.

--

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Inschrift auf Fragment eines Reliefs, Mathurā, Kushaṇa-Jahr 14

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 19 (1927/28). -- Nach S. 96]

Abb.: Inschrift auf steinernem buddhistischem Reliquienbehälter, Bīmarān,

Afghanistan

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 16 (1921/22). -- Nach S. 98]

Abb.: Inschriften auf Höhlenwänden, Khandagiri/Udayagiri, Orissa

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 13 (1915/16). -- Nach S. 166]

Inschriften auf Objekten aus gebranntem oder ungebranntem Lehm. Bei gebranntem Lehm wurden die Inschriften normalerweise vor dem Brennen angebracht.

Inschriften auf Balken, Pfeilern, Brettern. Wohl infolge der klimatischen Verhältnisse selten.

Beispiel:

Abb.: Holzpfeiler mit Brāhmī-Inschrift, Kirārī, Chhattisgarh (छत्तीसगढ़)

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 18 (1925/26). -- Nach S. 154]

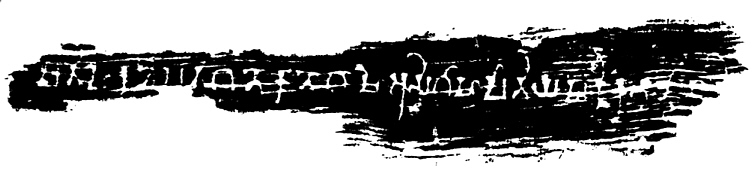

Abb.: Inschrift auf obigem Holzpfeiler

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 18 (1925/26). -- Nach S. 155]

Einige Votivinschriften auf Schneckengehäusen (conch-shell) sind erhalten.

Siegel und Inschriften auf Elfenbeinplatten.

Das wichtigste metallische Beschreibmaterial. Kauf-, Stiftungs- und Schenkungsurkunden auf Kupfer äußerst häufig. In Nordinden bevorzugte man einzelne Kupferplatten, die man beidseitig beschrieb und mit einem Metall-Siegel (meist aus Bronze) versah; in Südindien bevorzugte man viele Kupferplatten, in die man ein Loch machte, durch das man einen Metallring mit Siegel zog und so die Platten zusammenhielt. In Westindien verband man oft zwei Platten, die man mit der beschriebenen Seite nach Innen mit zwei Ringen durch zwei Löcher zusammenhielt.

Kupferplatten mit Besitzurkunden wurden sehr sorgfältig an sicher erscheinenden Orten aufbewahrt (vergraben, eingemauert etc.):

"Sehr eigentümlich scheint die Aufbewahrung der Kupferplatten bei privaten gewesen zu sein. Wie die Umstände bei vielen Funden z.B. in Valā (Valabhī) zeigen, wurden sie häufig in die Wände oder selbst in die Fundamente der Häuser der Besitzer eingemauert. Ebenso häufig wurden sie in kleine Behälter aus Ziegelsteinen mitten in den Feldern, deren Schenkung sie beurkundeten, niedergelegt. Die Finder oder auch arme Besitzer verkauften sie oft an Händler (Vāṇiā) oder verpfändeten sie denselben. Durch diese Sitte sind die oft bedeutend weiten Wanderungen der Platten und Siegel zu erklären. Die Originale, nach denen die Kupferplatten angefertigt sind, wurden wahrscheinlich in den königlichen Kanzleien aufbewahrt, deren Archivare (akṣapaṭalika, ākṣaśālika, akṣaśālin) oft erwähnt werden." [Quelle: Bühler, Georg <1837-1898>: Indische Palaeographie : von circa 350 A. Chr. - circa 1300 P. Chr.. -- Strassburg : Trübner, 1896. -- 96, IV S. ; 26 cm. + Siebzehn Tafeln zur Indischen Palaeographie (in Mappe). -- (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 1. Bd., 11. Heft). -- S. 93f.]

Neben Urkunden gravierte man in Kupferplatten auch Yantras, auch umfangreiche Bücher.

Neben Kupferplatten findet man Inschriften auf:

Beispiele:

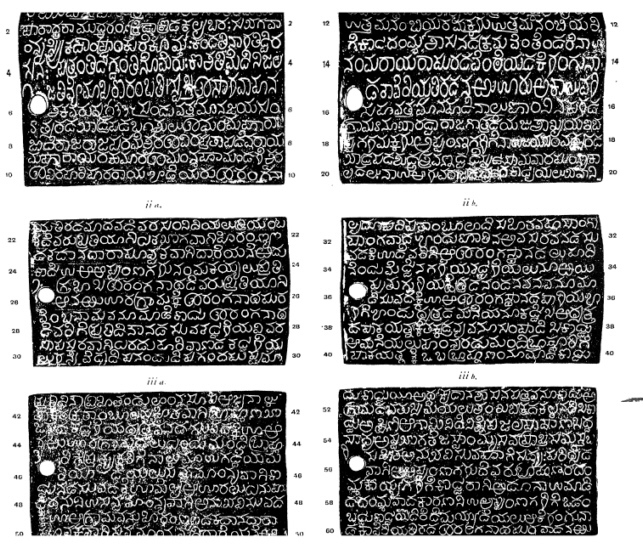

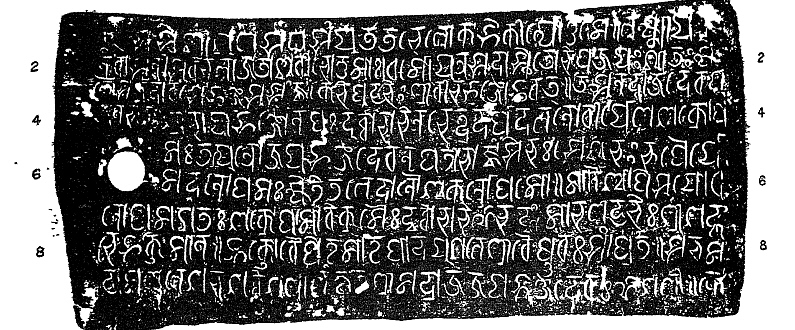

Abb.: Landschenkungsurkunde aus 7 Kupferplatten, 664 n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Kesavan, B. S. (Bellary Shamanna): Das Buch in Indien

: eine Zusammenstellung. -- New Delhi : National Book Trust, 1986. -- 80 S. :

Ill. -- S. 54.]

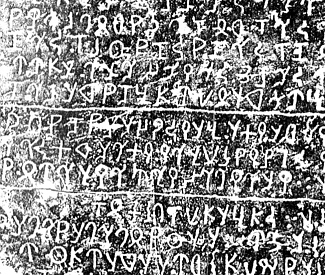

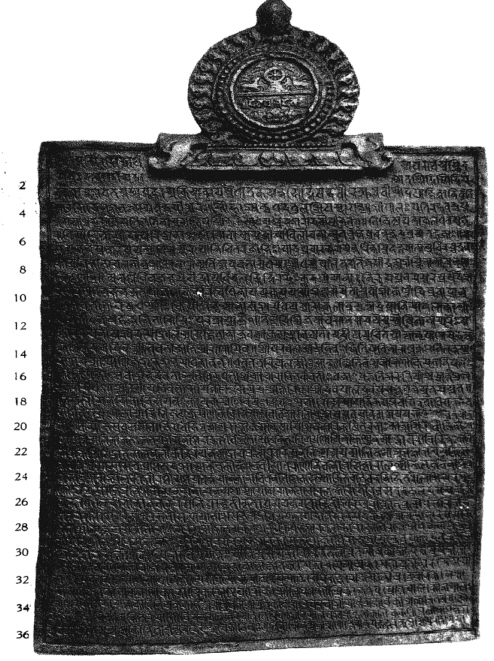

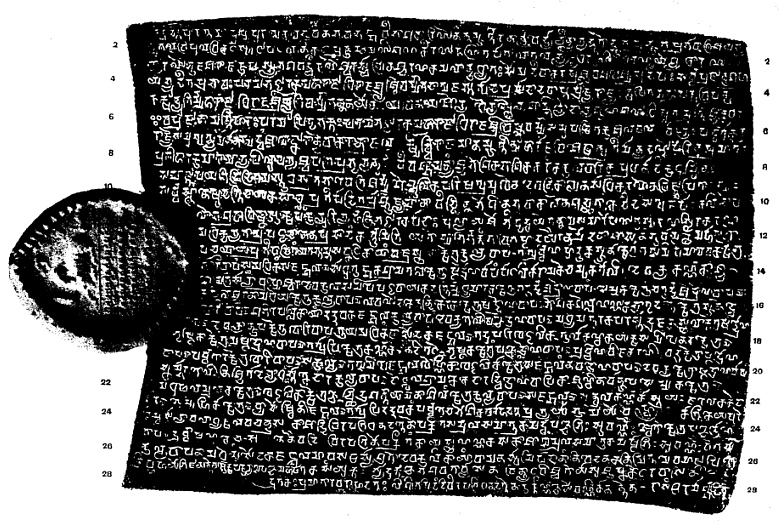

Abb.: Kupferplatten, beidseitig beschrieben, Schenkung eines Dorfes an den

Raṅganātha-Tempel in Śrīraṅgam (ஸ்ரீரங்கம்), Tamil Nadu, Śaka 1336

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 16 (1921/22). -- Nach S. 224]

Abb.: Siegel einer Schenkungsurkunde auf Kupferplatten, Nimarru, Guntur Distrikt

(గుంటూరు), Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 18 (1925/26). -- Nach S. 56.]

Abb.: Einzelkupferplatte (beidseitig beschrieben) mit Siegel, Monghyr/Munger (मुन्गेर), Bihar,

Saṃvat 33

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 18 (1925/26). -- Nach S. 304.]

Abb.: Kupferplatte mit vermutlich gefälschtem Siegel, Bestätigung einer früheren

Stiftung, Taleśvara, Almora District, Uttarakhand

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 13 (1915/16). -- Nach S. 114]

Abb.: Kupferplatte mit Unterschrift, Stiftungsurkunde, Conjeeveram = Kanchipuram

(காஞ்சிபுரம), Śaka 1444

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 13 (1915/16). -- Nach S. 126]

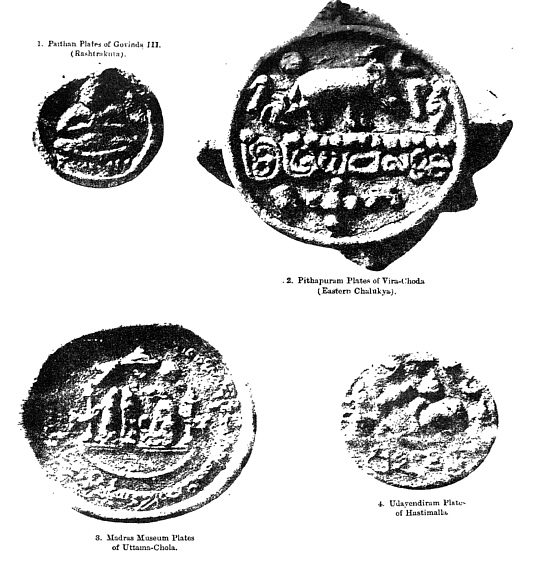

Abb.: Siegel von Stiftungsurkunden auf Kupferplatten

Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 3 (1894/95). -- Nach S. 104]

Abb.: Inschrift auf einem Kupferkessel, Widmung an eine buddhistische

Mönchsgemeinde, Shorkot, Punjab, Pakistan, 83 n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 16 (1921/22). -- Nach S. 14]

Häufig wird der Name des Besitzers in Silberobjekte eingraviert. Es gibt auch einige Inschriften auf Gold- und Silbertafeln. Jainas schreiben manch Yantras auf Silberplatten.

Beispiel:

Abb.: Vertrag zwischen den Zamorins/Saamoothirippādu (സാമൂതിരി) von

Kalikut/Kozhikode (കോഴിക്കോട്) und der Niederländischen Ostindiengesellschaft

(Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie) auf einem 2 m langen Goldstreifen, 1691

[Bildquelle: Kesavan, B. S. (Bellary Shamanna): Das Buch in Indien

: eine Zusammenstellung. -- New Delhi : National Book Trust, 1986. -- 80 S. :

Ill. -- S. 56.]

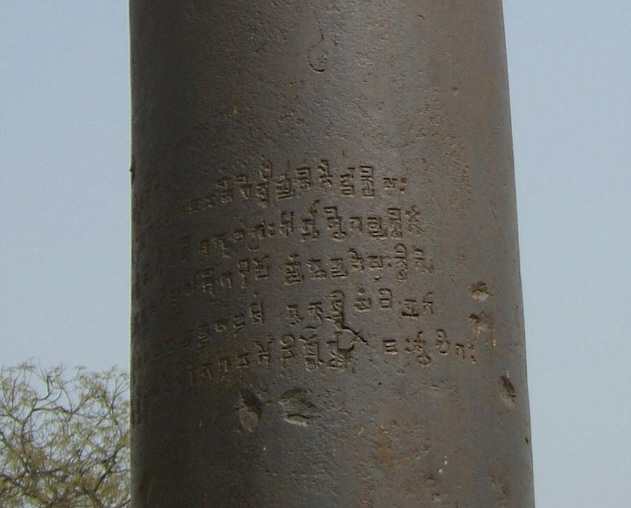

Abb.: Inschrift auf der Eisensäule, Qutb-Komplex (क़ुतुब; قطب ), Delhi

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Im Folgenden soll und kann keine Einführung in die äußerst vielfältige indische Paläographie geboten werden. Die Abbildungen sollen nur einen ersten Eindruck von der Vielfalt der Schriften und den Schwierigkeiten ihrer Entzifferung geben.

Die wichtigsten Inschriften-Schriften sind:

Bis jetzt noch nicht entziffert. Es ist weder klar, um was für eine Art von Schrift es sich handelt, noch um welche Sprache.

Im Gegensatz zu den anderen indischen -- nicht arabisch-persischen -- Schriften von rechts nach links laufend.

Name "Khāroṣṭhī" nach der zweiten der 64 Schriften, die im 10. Kapitel des buddhistischen Lalitavistara genannt werden (und die der Bodhisatta als Kind beherrscht haben soll).

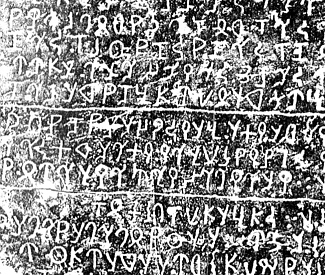

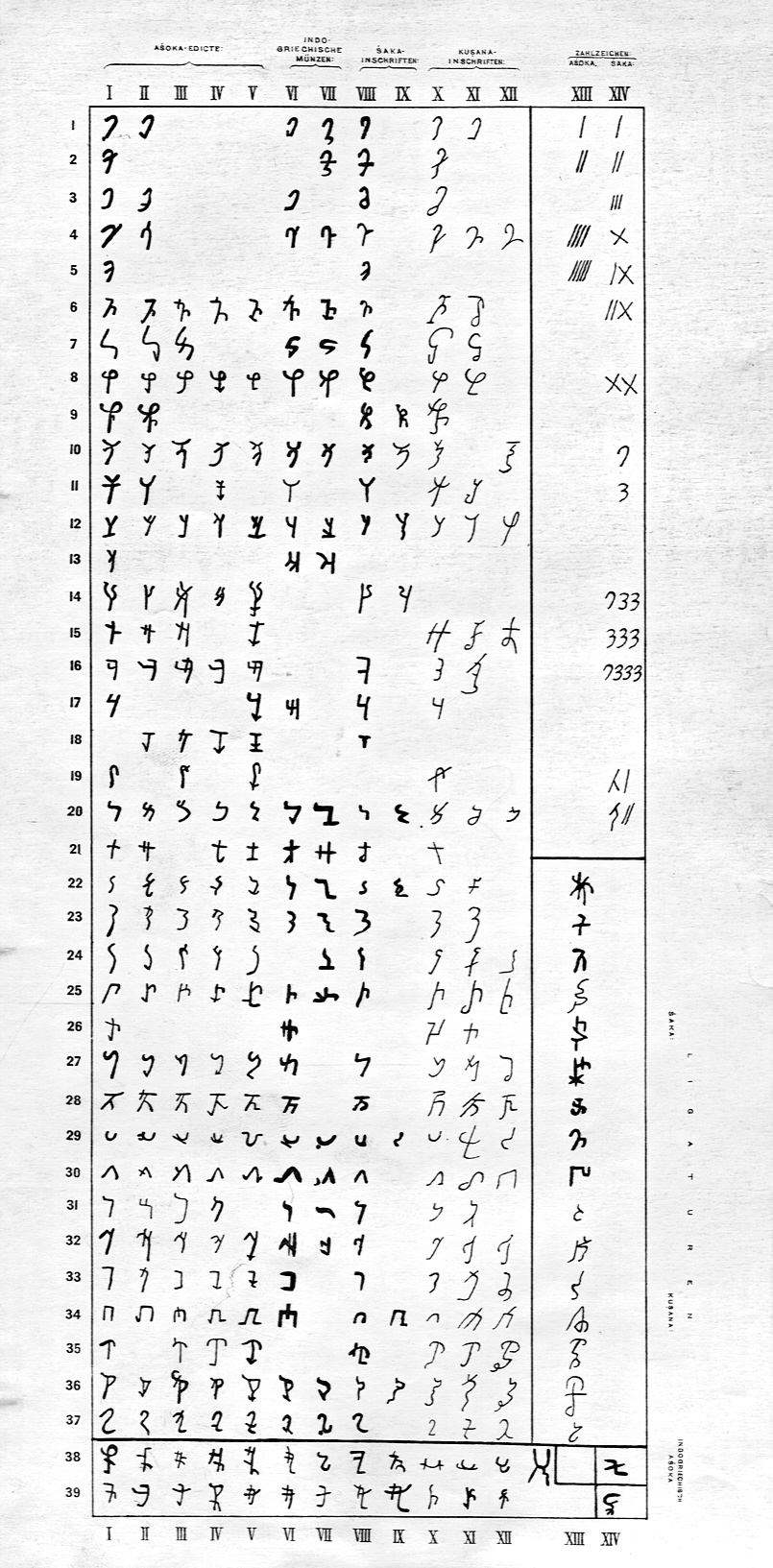

Abb.: Kharoṣṭhī-Schrift von ca. 350 v. Chr. bis ca. 200 n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Bühler, Georg <1837-1898>: Indische Palaeographie : von circa 350 A. Chr. - circa 1300 P. Chr.. -- Strassburg : Trübner, 1896. -- 96, IV S. ; 26 cm. + Siebzehn Tafeln zur Indischen Palaeographie (in Mappe). -- (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 1. Bd., 11. Heft). -- Tafelmappe]

Abb.: Silber-Tetradrachme des Indo-griechischen Königs Philoxenus (100-95 v.

Chr.), Inschrift Vorderseite: griechische Schrift, Rückseite. Khārōṣṭhī-Schrift

Abb.: Coin of Gurgamoya the King of Khotan, Khotan 1st Century CE. Obv:

Kharoshthi legend "Of the great king of kings, king of Khotan, Gurgamoya. Rev:

Chinese legend: "Twenty-four grain copper coin", British Museum

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia Commons, GNU FDLicense]

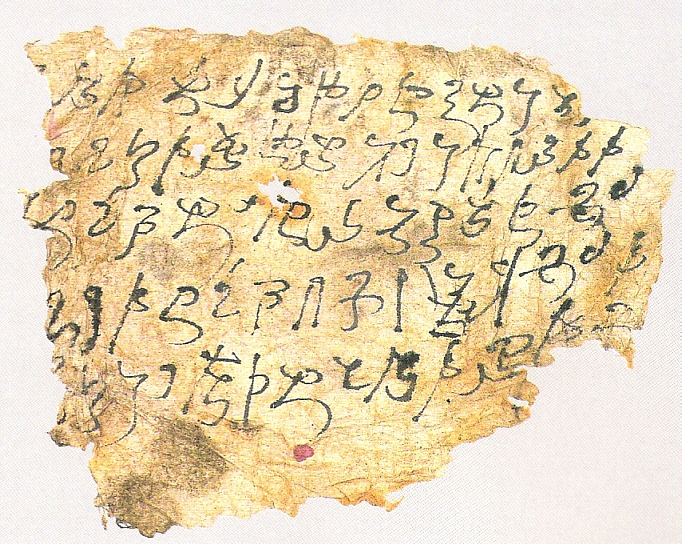

Abb.: Khāroṣṭhī-Schrift, Yingpan, Östliches Tarim-Becken, Xinjiang Museum.

Name "Brāhmī" nach der ersten der 64 Schriften, die im 10. Kapitel des buddhistischen Lalitavistara genannt werden (und die der Bodhisatta als Kind beherrscht haben soll).

Die Schrift wird von links nach rechts geschrieben.

Bisher älteste Zeugnisse vermutlich in Anurādhapura, Sri Lanka auf Tonscherben ausgegraben. Die Schichten, in denen sie gefunden wurden, werdern zwischen 6. bis 4. Jahrhundert v. Chr. datiert. Es ist allerdings auch möglich, dass die Scherben aus jüngeren Schichten in die älteren gesunken sind.

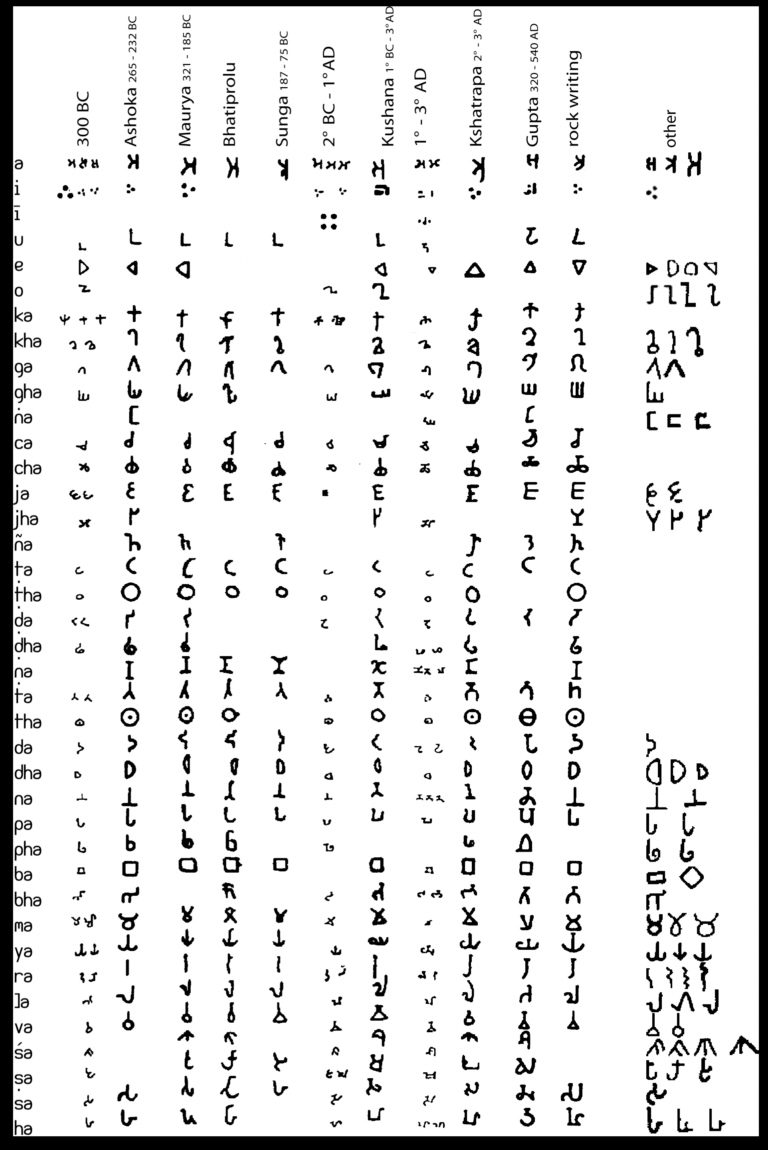

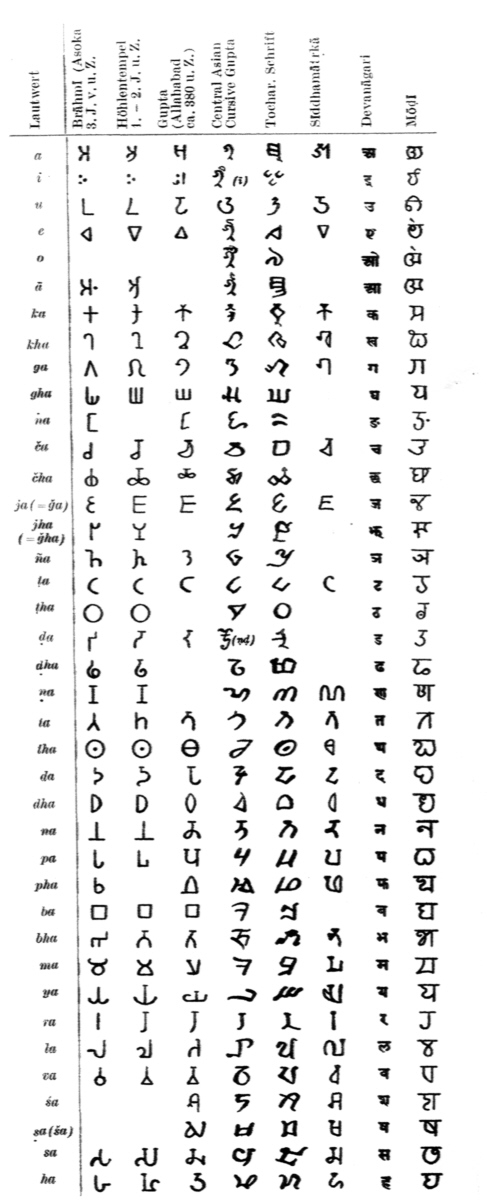

Abb.: Beispiele zu Brāhmī

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

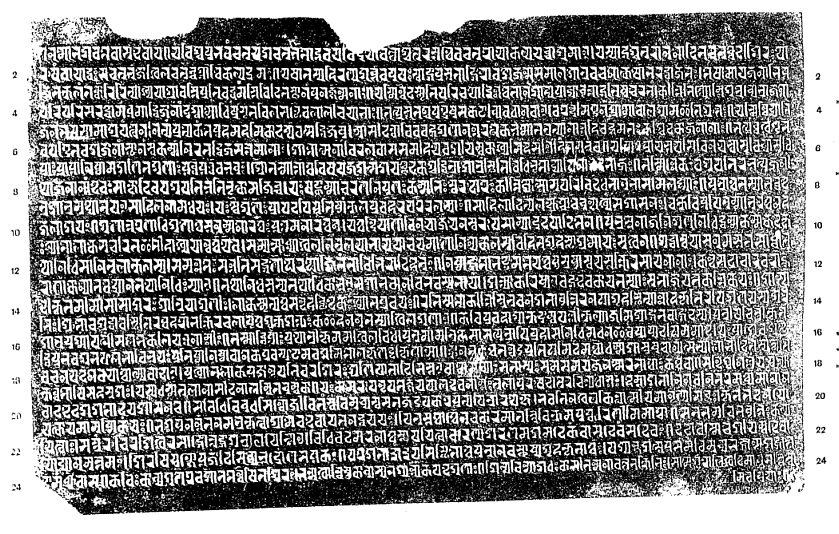

Abb.: Brāhmī-Inschrift, Fragment des 6. Säulenedikts von Aśoka, von der Säule

von Meerut (मेरठ, میرٹھ), British Museum

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

Einen wichtigen Einfluss auf die Entwicklung der nordindischen Schriften hatte die Siddhamātṛkā (Siddham). Aus ihr entwickelte sich die Devanāgarī, die manchmal auch außerhalb Nordindiens als Standardschrift für Sanskrit verwendet wurde. (Siddham wurde 806 vom buddhistischen Mönch Kūkai (空海) in Japan eingeführt, wo diese Schrift (als 悉曇 bzw. 梵字) von manchen buddhistischen Schulen zum Schreiben von Sūtras und Mantras verwendet wird.)

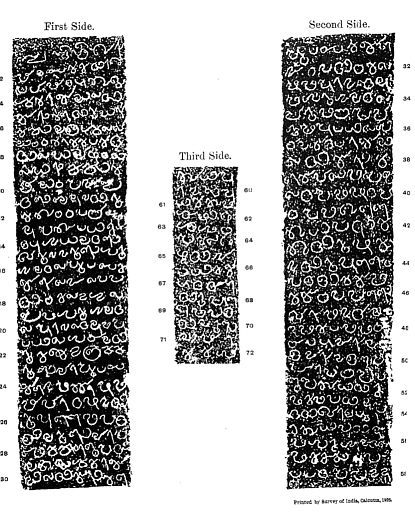

Abb.: Inschrift auf Steintafel, nördliche Schrift, Mauzā Silimpur, Bogra (বগুড়া)

District, Bangladesh, nicht datiert

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 13 (1915/16). -- Nach S. 290]

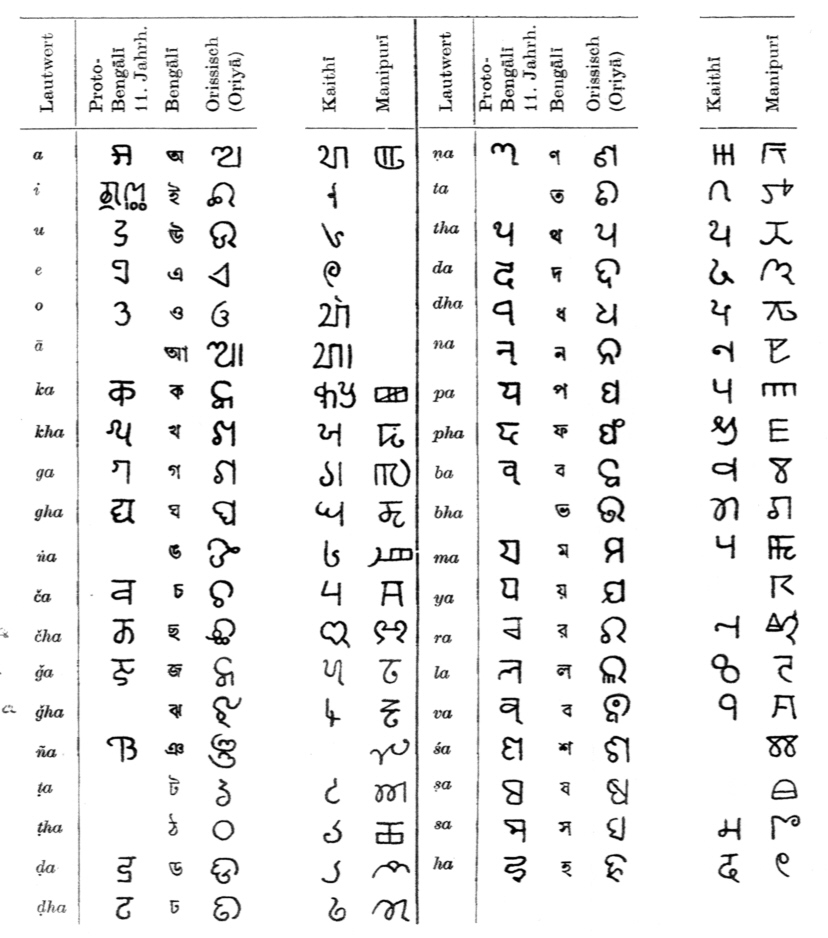

Abb.: Nördliche Schriften

[Bildquelle: Jensen, Hans <1884 - 1973>: Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. -- 3., neubearb. und erw. Aufl. -- Berlin <Ost> : Deutscher Verl. der Wissenschaften, 1969. -- Abb. 346.]

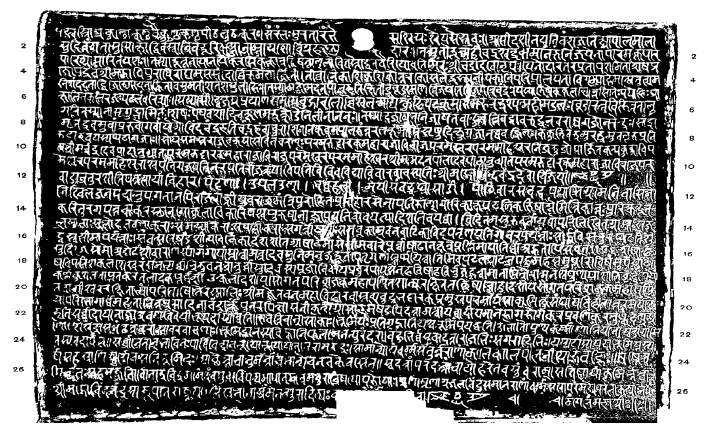

Abb.: Devanāgarī-Inschrift auf Kupferplatte, Saheth Maheth, Vikrama-Samvat 1186

(= 1128/29 n. Chr.)

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 11 (1911/12). -- Nach S. 24.]

Abb.: Nāgarī-Inschrift auf Kupferplatte, Orissa, 11./12. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 3 (1894/95). -- Nach S. 314.]

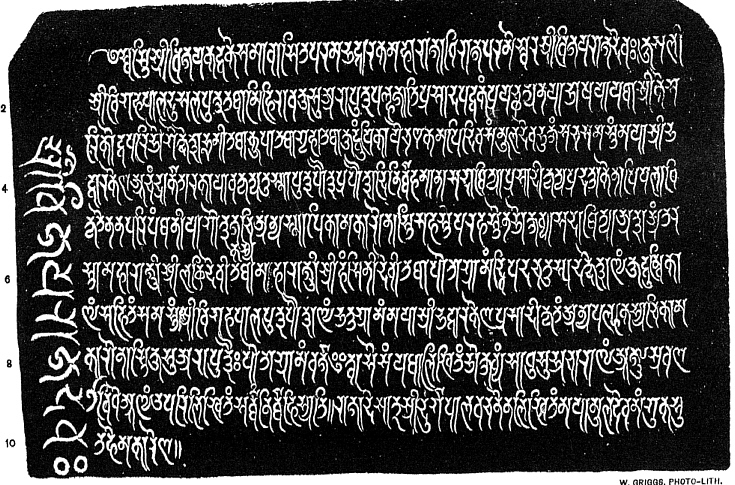

Im Nordosten entwickelte sich aus Siddhamātṛkā Proto-Bengali (Gauḍī)

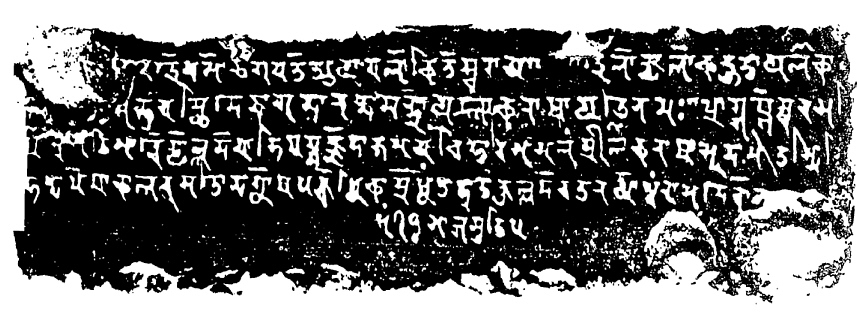

Abb.: Nordwestliche Schriften

[Bildquelle: Jensen, Hans <1884 - 1973>: Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. -- 3., neubearb. und erw. Aufl. -- Berlin <Ost> : Deutscher Verl. der Wissenschaften, 1969. -- Abb. 358.]

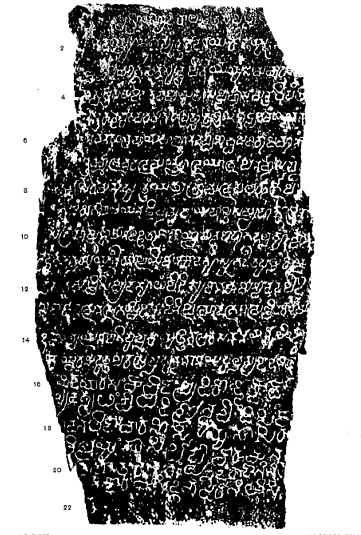

Abb.: Vorläufer der Oriya-Schrift auf Kupferplatte, Antirigām, Ganjam District,

Orissa, 12. Jhdt n. Chr. (?)

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 19 (1927/28). -- Nach S. 44.]

Im Nordwesten entstand zu Beginn des 7. Jhdts. n. Chr. Proto-Śāradā, die Vorläuferin der Śāradā und anderer nordwestlicher Schriften.

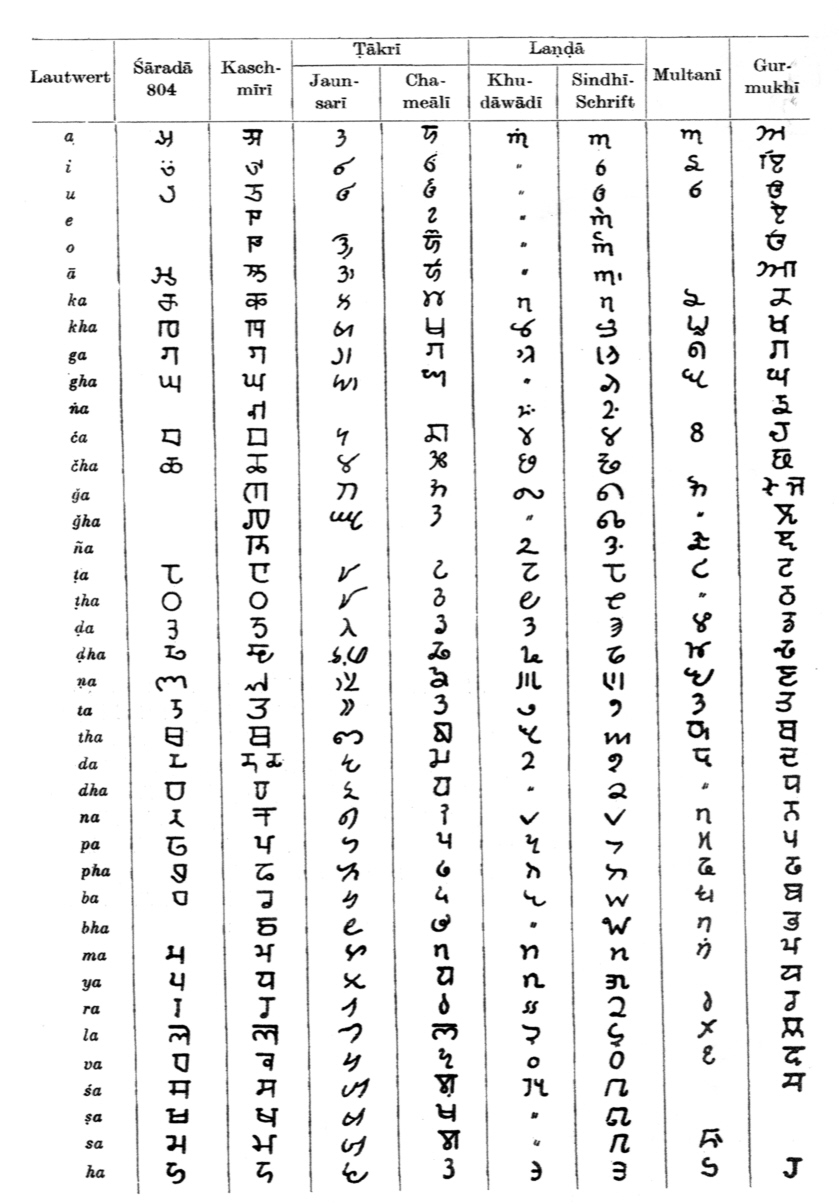

Abb.: Śāradā-Schrift, Steininschrift, Arigom, südlich von Śrinagar ( سرینگر),

Kashmir, 16. Nov. 1197

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 9 (1907/08). -- Nach S. 300.]

Abb.: Nordwestliche Schriften (nicht alle auf Inschriften gebräuchlich)

[Bildquelle: Jensen, Hans <1884 - 1973>: Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. -- 3., neubearb. und erw. Aufl. -- Berlin <Ost> : Deutscher Verl. der Wissenschaften, 1969. -- Abb. 351.]

Abb.: Steininschrift, Altkannada, Devageri, Dhārwār (ಧಾರವಾಡ) District, Karnataka

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 11 (1911/12). -- Nach S. 8.]

Hier gibt es folgende Schriftgruppen:

Sowie die weiteren Entwicklungen zu den modernen Südindischen Schriften.

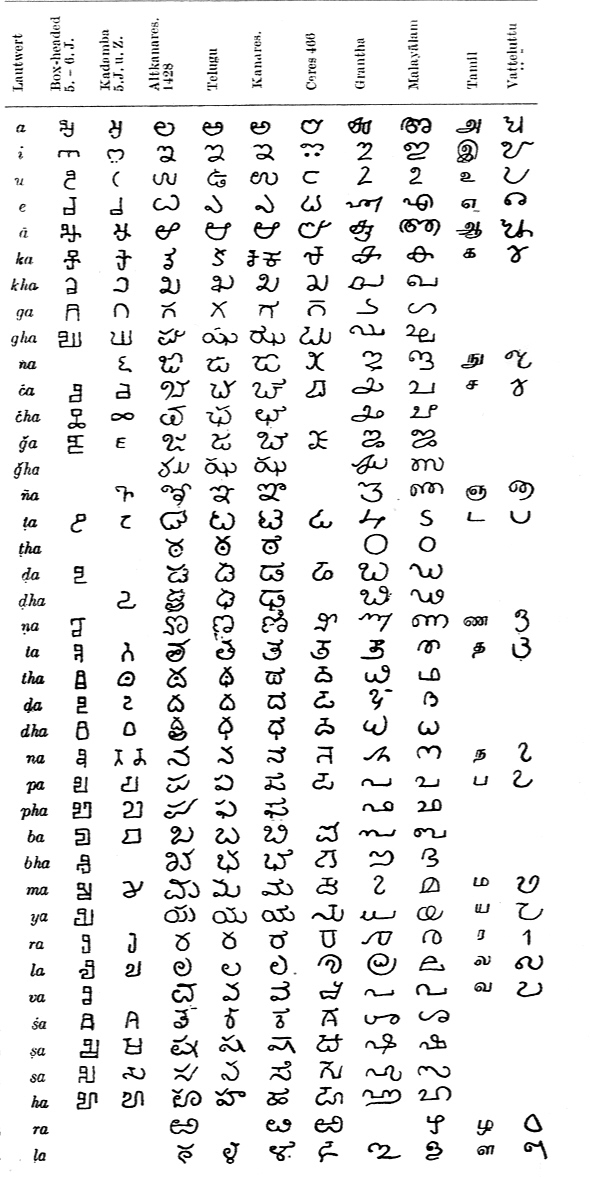

Abb.: Südindische Schriften

[Bildquelle: Jensen, Hans <1884 - 1973>: Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. -- 3., neubearb. und erw. Aufl. -- Berlin <Ost> : Deutscher Verl. der Wissenschaften, 1969. -- Abb. 394.]

Abb.: Inschrift, Kanchipuram (காஞ்சிபுரம), Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: Ravages. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ravages/174383615/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-04.

--

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)

Beispiel siehe unter aramäische Schrift

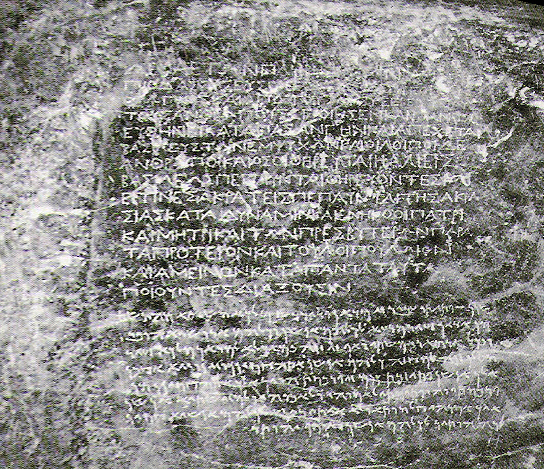

Abb.: Asoka-Inschrift griechisch (oben) und aramäisch, Kandahar (کندهار),

Afghanistan

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia, Public domain]

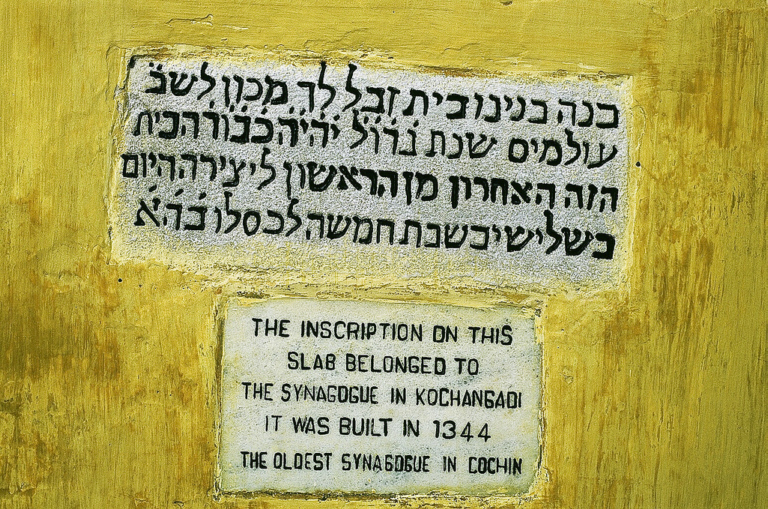

Abb.: Inschrift der alten Synagoge on Kochangadi, Kochi (കൊച്ചി),

Kerala

[Bildquelle: thaths. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/thaths/1607898905/. -- Zugriff am 2008-02-28.

--

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

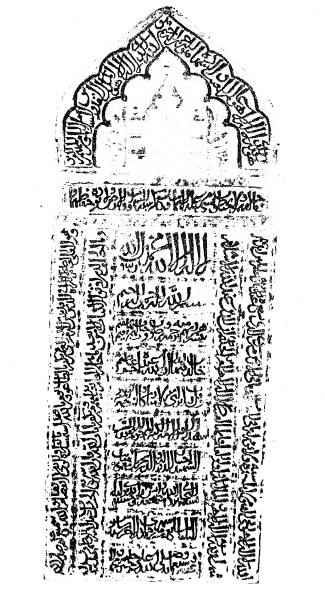

Abb.: Inschrift auf dem Grabstein Ikhtiyaru-d-Daulah's, Cambay (heute: Khambhāṭ,

Gujarat)

[Quelle der Abb.: Epigraphia Indo-Moslemica. -- 1917/18. -- Pl. III(c)]

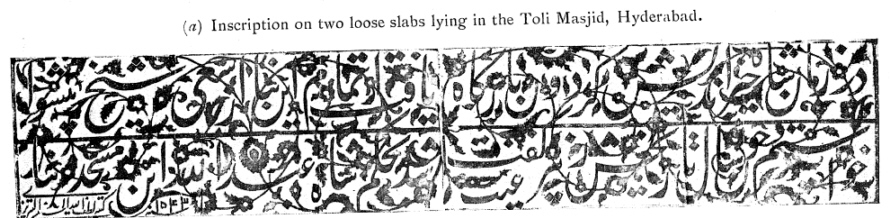

Abb.: Inschrift, Toli Masjid, Hyderabad (హైదరాబాద, حیدر آباد, हैदराबाद)

[Quelle der Abb.: Epigraphia Indo-Moslemica. -- 1917/18. -- Pl. XIX]

Abb.: Brückenstiftung des Armeniers Coja Petrus Uscan in Persisch,

Lateinisch und Armenisch, 1726, Chennai (சென்னை), Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: Ravages. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ravages/340587374/. -- Zugriff am 2008-02-18.

--

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Grabinschrift, Park Street Old Cemetery, Kalkutta (কলকাতা),

1804

[Bildquelle: scottsforum. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/scottzuke/857192916/. -- Zugriff am 2008-02-28.

--

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

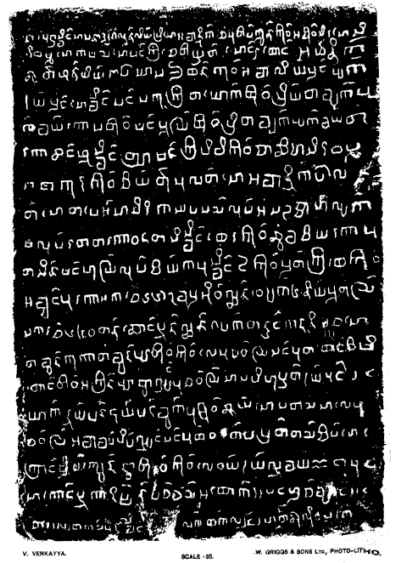

Abb.: Birmanische Inschrift, Bodh Gaya, Bihar

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 11 (1911/12). -- Nach S. 118.]

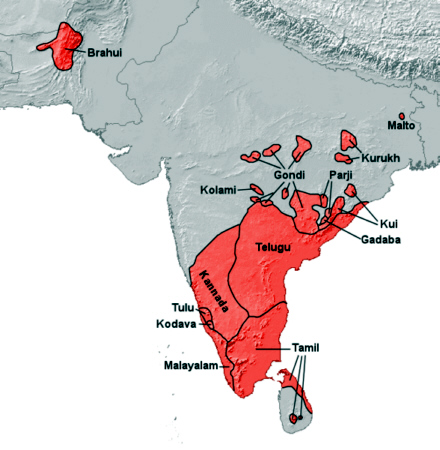

Abb.: Verbreitungsgebiet heutiger dravidischer Sprachen

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

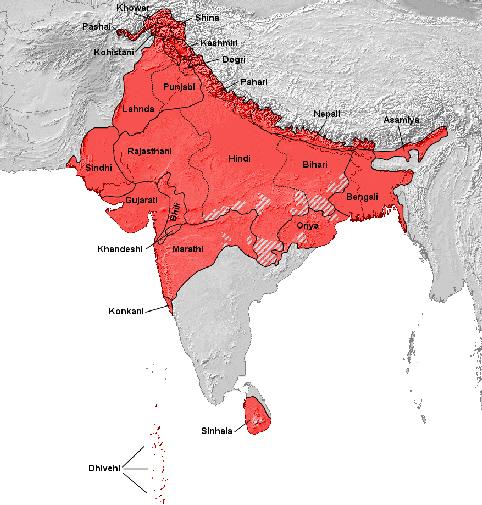

Abb.: Verbreitungsgebiet heutiger indoeuropäischer Sprachen

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]

1 Zu den Prākṛts siehe:

Grierson, George Abraham <1851-1941>: Prakrit (1911). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 3. Inschriften, 6.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-08. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen036.htm

Georg Bühler schreibt zu der Herstellung der Inschriften und den damit verbundenen Berufen:

"§ 39. Schreiber, Graveure und Steinmetzen. Obgleich das älteste indische Alphabet eine Schöpfung der brahmanischen Schulmänner ist (S. 18) und der Schreibunterricht bis auf die neueste Zeit hauptsächlich in den Händen der Brahmanen geblieben ist, so finden sich doch schon früh Anzeichen, dass es professionelle Schreiber gab, die einen eigenen Stand oder Kaste bildeten. Der älteste Namen derselben ist das schon im südbuddhistischen Kanon und im Epos gebräuchliche Wort lekhaka (S. 5). In der Sāñci-Inschrift St. I. Nr. 143 wird es deutlich zur Bezeichnung der Profession des Gebers gebraucht. Man kann jedoch zweifeln, ob es, wie ich es gefasst habe, »Abschreiber von MSS.« oder »Schreiber« überhaupt, d. h. auch »Kanzlist« bedeutet. In manchen späteren Inschriften bezeichnet es ohne Zweifel die Anfertiger der auf Kupfer oder Stein einzumeißelnden Dokumente. In der heutigen Zeit ist der lekhak stets ein Kopist von MSS. und seine Profession ist meist die letzte Zuflucht armer Brahmanen, seltener alter Kanzlisten (Kāyasth, Karkun). Bei den Jaina wurden und werden viele MSS., wie deren Praśasti beweisen, Von Mönchen, Novizen oder selbst Nonnen geschrieben, bei den Bauddha Von Nepal, von den Bhikṣu, Vajrācārya u. s. w.

Ein zweiter Namen der professionellen Schreiber, der schon im 4. Jahrh. n. Chr. üblich war (S. 5) ist das oben besprochene Wort lipikara oder libikara, das in den Kośa als Synonym von lekhaka aufgeführt und in der Vāsavadattā schlechthin für »Schreiber« gebraucht wird. Aśoka (F. Ed. XIV) bezeichnet damit seine Kanzlisten und in den Sāñci-Inschriften St. I, Nr. 49 gibt sich Subāhita Gotiputa den Titel rājalipikara »Schreiber des Königs.« Wahrscheinlich wurde dies Wort in der älteren Zeit ausschließlich in der Bedeutung »Kanzlist« verwendet. In einer Anzahl von Valabhī-Inschriften des 7.—8. Jahrh. n. Chr. erhält der Schreiber des Dokumentes, der gewöhnlich der »Minister für Allianzen und Krieg« (saṃdhivigrahādhikṛta) ist, den Titel divirapati, divīrapati. Divira-divīra ist das persische debīr »Schreiber«, welches während der Sassanidenzeit, wahrscheinlich in Folge des lebhaften Handelsverkehrs, in Kathiawar als Lehnwort heimisch geworden ist. Divira erscheint gleichfalls in der Rājataraṅginī und in andern kashmirischen Werken der späteren Zeit. In Kṣemendra's Lokaprakāśa werden sogar verschiedene Klassen gañjadivira »Basarschreiber«, grāmadivira »Dorfschreiber«, nagaradivira »Stadtschreiber« und khavāsadivira (?) erwähnt.

Die beiden genannten und andere Werke des 11. Jahrh. gebrauchen zur Bezeichnung von Schreibern auch den Ausdruck kāyastha, der zuerst bei Yājñavalkya (1. 335) vorkommt und noch jetzt im nördlichen und östlichen Indien gewöhnlich ist. Die Kāyastha sind aber eine streng abgeschlossene Kaste, welche, obwohl sie Śūdrablut in den Adern haben soll, auf eine hohe Stellung Anspruch macht und oft eine solche, sowie großen politischen Einfluss, wirklich besessen hat. In den Inschriften lässt sich das Wort vom 8. Jahrh. an nachweisen, zuerst in der Kaṇasva-Inschrift von 738/9 p. Chr. aus Rajputana. Neben Kāyastha findet sich auch häufig karaṇa und karaṇika, seltener karaṇin, śāsānika und dharmalekhin. Karaṇa ist wahrscheinlich nur ein anderer Namen der Kāyastha, da es auch eine Kaste arischen Halbbluts bezeichnet. Die anderen Termini, unter denen karaṇika von Kielhorn mit »writer of legal documents« (karaṇa) Übersetzt wird, sind wahrscheinlich offizielle Titel ohne Nebenbeziehung auf die Kaste. Die Entwickelung der Alphabete und die Erfindung neuer Schriftformen ist neben den Brahmanen, Jaina- und Bauddha-Mönchen besonders den professionellen Schreibern und den Schreiberkasten zuzuschreiben, nicht, wie mitunter geschieht, den Steinmetzen und den Graveuren der Kupfertafeln, welche ihrer Bildung und Beschäftigung nach dazu wenig geeignet waren.

Wie die Notizen am Ende verschiedener Inschriften zeigen, wurden von den auf Stein eingemeißelten poetischen Praśasti, Kāvya u. s. w., gewöhnlich durch einen Schreiber eine Reinschrift hergestellt, welche der Steinmetz (sūtradhāra, śilākūṭa, rūpakāra, śilpin) benutzte. Hiermit stimmt, was ich selbst in einem Falle gesehen habe. Der Steinmetz erhielt ein Blatt mit der Reinschrift des einzumeißelnden Dokumentes, einer Tempelinschrift, das genau die Größe des zu benutzenden Steines hatte, zeichnete die Buchstaben danach unter der Aufsicht eines Pandit auf den Stein und meißelte sie dann ein. In einigen Fällen dagegen behaupten die Autoren, dass sie selbst die Arbeit des Steinmetzen getan haben und in einigen andern sagen die Steinmetzen, dass sie die Reinschrift besorgt haben.

Die Angaben über die Herstellung der Śāsana auf Kupfertafeln sind ungenauer und spärlicher. Gewöhnlich wird nur der Schreiber genannt, der meist ein höherer Beamter, Minister, (amātya, sāṃdhivigrahika, rahasika) oder ein General (senāpati, balādhikṛta) ist. Statt solcher kommt mitunter ein sūtradhāra oder tvaṣṭā als Schreiber vor, der aber in Wirklichkeit wohl nur die Gravierung besorgt hat. Nur selten und in später Zeit wird gesagt, durch wen die Platte graviert (utkīrṇa, unmīlita) ist. Als Graveure werden meist verschiedene Handwerker genannt, ein lohakāra oder ayaskāra, womit der Kansār oder Kupferschmied der heutigen Zeit gemeint sein wird, ein sūtradhāra, »Steinmetz«, hemakāra oder sunara (wahrscheinlich für soṇāra) »Goldschmied,« ein śilpin, oder vijñānika »kunstfertiger Handwerker.«

In den Śāsana der Gaṅga von Kaliṅga wird die Gravierung häufig dem akṣaśālin. oder akṣaśālika »Archivar« zugeschrieben, womit aber nur gemeint sein dürfte, dass dieser die Gravierung überwachte. Für Kanzlisten und Schreiber gab es auch Handbücher, welche Formulare für Landschenkungen und Staatsverträge, sowie für Briefe, Schuldbriefe, Wechsel, (huṇḍī) u.s.w. enthielten. Erstere finden sich in der Lekhapañcāśikā und letztere in Kṣemendra-Vyāsadāsa's Lokaprakāśa."

[Quelle: Bühler, Georg <1837-1898>: Indische Palaeographie : von circa 350 A. Chr. - circa 1300 P. Chr.. -- Strassburg : Trübner, 1896. -- 96, IV S. ; 26 cm. + Siebzehn Tafeln zur Indischen Palaeographie (in Mappe). -- (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 1. Bd., 11. Heft). -- S. 94f.]

Siehe die ausgezeichnete Kurzdarstellung:

Fleet, J. F. (John Faithful) <1847-1917>: Hindu Chronology (1910). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 3. Inschriften, 5.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-07. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen035.htm

Einige der kontinuierlichen (historischen/pseudohistorischen) Zeitrechnungen:

| Name der Zeitrechnung (Ära) | Jahr 0 bzw. 1 |

|---|---|

| Kaliyuga |

3102 v. Chr. |

| Vikrama |

58 v. Chr. |

| alte Śaka | ??? |

| Christliche | 1 n. Chr. |

| Śaka | 78 n. Chr. |

| Kalacuri-Cedi | ca. 248 n. Chr. |

| Gupta-Valabhī | 319 n. Chr. |

| Gāṅga (Gāṅgeya) | ca. 498 n. Chr. (?) |

| Harṣa | 606 n. Chr. |

| Hijrī (muslimische) | 622 n. Chr. (reiner Mondkalender!)1 |

| Bhāṭika | 624 n. Chr. |

| Kollam (Kolamba) | 824 n. Chr. |

| Bhaumakara | 831 n. Chr. (?) |

| Nepali (Newari) | 879 n. Chr. |

| Cālukya-Vikrama | 1076 n. Chr. |

| Siṃha | 1113 n. Chr. |

| Lakṣmaṇasena | 1178 n. Chr. (?) |

1 Hijrī-Jahre kann man in christliche Jahre umrechnen nach der Näherungsformel:

Christliche Jahreszahl (n. Chr.; A.D.) ≈ [(Hijrī-Jahreszahl) x (32/33)] + 612

Einige muslimische Zeitrechnungen, die Modifikationen der Hijrī (Arabisch: التقويم الهجري; at-taqwīm al-hijrī; Persisch: تقویم هجري قمری taqwīm-e hejri-ye qamari) sind:

Zu den Einzelheiten dieser muslimischen Zeitrechnungen konsultiere man: Sircar, D. C. (Dines Chandra) <1907 – 1983>: Indian epigraphy. -- Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass, 1965. - XXI, 475, V S. : Ill. -- S. 308 - 317.

Einige der zyklischen (astronomischen) Zeitrechnungen:

| Name der Zeitrechnung (Ära) | Zyklus | Jahr 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Saptarṣi | 2700 Jahre | 3076 v. Chr. |

| Zwölfjahrezyklus des Bṛhaspati (Jupiter) | 12 Jahre | |

| Sechzigjahrezyklus des Bṛhaspati (Jupiter) | 60 Jahre |

Einige Begriffe zum Verständnis des Folgenden:

"5. The Decursus of the Hindu Solar Reckoning.—Hindu astronomers reckon the present chronology from the midnight between 17th and 18th February 3102 B.C. which is commonly called the beginning of Kaliyuga. On the morning of 18th February 3101 B.C., that is one year later, one complete Hindu solar year had run out by 6.13 a.m. i.e. at .25875 of the day. As however the Hindu day is always reckoned from sunrise, mean sunrise for the whole of India being at 6 a.m., the first year is reckoned to have been completed at 13 minutes (or exactly .00876 of a day) Indian time of the day, on 18th February 3101 B.C. At this moment the year 1 of Hindu chronology began. You probably thinking it was the year 2 which began on 18th February 3101 B.C., and not the year 1 ; but the Hindus generally reckon completed or expired years, and not current years, as the European calendar does ; and this is another point which you should thoroughly understand. The first year of the Hindu chronology, which began on 18th February 3102 B.C., is, according to Hindu reckoning, the year 0. By adding 3101 to an English calendar year A.D. you can always arrive at the corresponding (expired) year of Kaliyuga. Thus the present year 1910 A.D. is K.Y. 5011. For a B.C. year, the K.Y. equivalent is obtained by subtracting it from 3102, not 3101." [Quelle: Swamikannu Pillai, L. D. (Lewis Dominic) <1865 - 1925>: Indian chronology : (Solar, lunar and planetary). A practical guide to the interpretation andverification of tithis, nakshatras, horoscopes and other Indian time-records, B.C. 1 to A.D. 2000. -- Reprint der Ausgabe von 1911. -- New Delhi : Asian Educational Services, 1982. -- Getr. Seitenzählung. -- S. 2f.]

"Section xvii.—The Varttamāna, Pūrṇimānta, Amanta and Kārttikādi systems of citation. 148. The ordinary or normal mode of citing an Indian date is by means of

- gata or 'expired' years,

- amānta months (or months beginning with the first tithi after new moon or Amāvāsyā),

- and Chaitrādi years (or lunar years beginning with Chaitra). The lunar year can begin with Chaitra only when the solar year begins with Mesha Saṅkrānti. Therefore a reckoning by Chaitrādi lunar years is the same as reckoning by Meshādi solar years.

149. Exceptional modes of citation, used at certain epochs of history, or still used in certain parts of India, are :—

- Varttamāna, or current years, opposed to gata (expired);

- Pūrṇimānta months, beginning with the tithi after full moon;

- and Kārttikādi lunar years (or "southern" years) beginning with the lunar month Kārttika.

150. In the Pūrṇimānta system, each month beginning with a full moon is named after the next amānta month, but takes in the dark fortnight preceding each new moon. It is to this system that we owe the name paksha, lit. a wing, the dark and bright fortnights being the wings on either side of a new moon.

151. In the Kārttikādi lunar year system, the year beginning with lunar Karttika takes the number of the Meshādi solar year then running, and has in common with it the five months, Lunar Kārttika to Lunar Phālguṇa.

Canons—

- A dark fortnight in nth Amānta month is in (n + 1)th Pūrṇimānta month.

- Any month or tithi in Nth year, expired, is in (N + 1)th year current.

Any of the months named in the margin [Chaitra, Jyeshṭha, Āshāḍha, Śrāvaṇa, Bhādrapada, Āśvina] in Nth year Chaitrādi, expired, is ascribed to the

(N - 1)th year Kārttikādi, expired, or to

(b) Nth year, Kārttikādi, current.

N.B.—Conversely, any of the above months in nth year Kārttikādi, expired, is ascribed to (n + 1)th year Chaitrādi, expired.

For clearness' sake, we will present these three rules under three aspects, one of which, when we are in doubt, every problem before us must assume.

First aspect.—If we have before us a dark fortnight or bahula tithi of the nth month in the Nth year, known to be an expired year, but do not know whether the system is amānta or pūrṇimānta, we must search for the tithi both in the nth and the (n — 1)th month in our ordinary (Amānta) tables.

Second aspect.—If we have before us a dark fortnight or bahula tithi of the nth month in the Nth year, and do not know whether the month is amānta, or pūrṇimānta, nor whether the year is expired or current, we must, in using our tables, look for the tithi—

in the nth month, Nth year, expired;

in the (n — 1)th month, Nth year, expired ;

in the nth month, (N— 1)th year, expired; and

in the (n— 1)th month, (N—1)th year, expired.

Third aspect.—If we have before us a dark fortnight or bahula tithi of the nth month (from Chaitra to Āśvina, inclusive) in the Nth year and do not know whether the month is amānta or pūrṇimānta, or whether the year is expired or current, Chaitrādi or Kārttikādi, we must, in using our tables, look for the tithi—

in the nth month, Nth year, expired ;

in the (n -1 )th month, Nth year, expired;

in the nth month, (N - 1)th year, expired;

in the (n -1)th month, (N - 1)th year, expired;

in the nth month, (N + 1)th year, expired; and

in the (n — 1)th month, (N + 1)th year, expired.

N.B. For bright fortnght or śukla dates in any month, no search need be made in any case in the (n — 1)th month ; and whether for bright or dark fortnight dates in the months of Kārttika to Phālguṇa inclusive, no search need be made in any case in (N + 1)th year, expired.

Readers who prefer Professor Kielhorn's mode of stating the same rules will find them in Indian Antiquary, Volume XIX, page 22, or at page 402 of Epigraphia Indica, Volume I. Any rules must be somewhat perplexing at first sight and should be carefully reasoned out by those interested in such investigations.

152. The lunar year beginning with lunar Chaitra of any solar year n is itself (n + 1). Thus, Chaitra 1265 may mean :—

Lunar Chaitra at the end of current solar 1264, i.e., at the end of expired solar 1263.

Lunar Chaitra at the end of expired solar 1264 and before the beginning of solar 1265 (expired).

Lunar Chaitra at the end of expired solar 1265 and before the beginning of solar 1266 (expired).

This ambiguity is independent of the difference between Chaitrādi and Kārttikādi systems, and is peculiar to the lunar month Chaitra."

[Quelle: Swamikannu Pillai, L. D. (Lewis Dominic) <1865 - 1925>: An Indian ephemeris: A.D. 700 to A.D. 1799 : showing, the daily solar and lunar reckoning according to the principal systems current in India with their English equivalents, also the ending moments of tithis and nakshatras, and the years in different eras, A.D., Hijra, Śaka, Vikrama, Kaliyuga, Kollam, etc., with a a perpetual planetary almanac and other auxiliary tables. -- Reprint der Ausgabe von 1922. -- Delhi : Agam Prakashan, 1982. -- Band 1,1: General principles and tables. - IX, 500 S. -- 1. publ. 1922. -- A rev. and enl. ed. of: Indian chronology, 1911. -- S. 52f.]

Swamikannu Pillai gibt folgende Spezifikationen zu den wichtigsten noch gebräuchlichen oder in Inschriften verwendeten Zeitrechnungen:

"Section xviii.—The eras now in use or met with in inscriptions. 153. In the following summary of Indian eras, adapted from Cunningham and other authorities, we give in each case the formula whereby a year of each era, "expired" or "current" as the case may be, may be obtained from the A.D. year, also noting where the era is or was in use, and whether it is amānta or pūrṇimānta, Chaitrādi or Kārttikādi and so forth.

- Kaliyuga (expired year=3102 minus B.C. year; A.D. year + 3101). Used all over India as a solar (Meshādi) and luni-solar (Chaitrādi) year. The years in this era, with A.D., Śaka, and Vikrama equivalents, are indicated in Eyetable k from 3102 B.C. to A.D. 2000; and they are regularly given in the Ephemeris from A.D. 700 to A.D. 1999.

- Saptaṛishi (current year = A.D. year + 76). Mostly current and mostly pūrṇimānta and Chaitrādi. At present in use in Kashmir and formerly in Multan and elsewhere. Quoted generally in cycles of 100 years. Thus A.D. 1910 = Saptarshi 1986, current, quoted only as "86 Saptarshi, current."*

* The saptaṛishis are supposed (by an astronomical fiction) to occupy each nakshatra for 100 years ; in other words they go round the circle of the nakshatras in 2,700 years. This convention is merely equivalent to our reckoning by centuries. Thus when Varāhamihira, quoting from Garga, says that the ṛishis were in Magha (nakshatra No. 10) during the reign of Yudhishṭira, he means that the epoch was removed by 7 centuries from another when the ṛishis were in Kṛittikā nakshatra; and if we suppose that the astronomical fiction of the longitudes of all heavenly bodies being 0° at 0 day in 0 year Kaliyuga, was applied to the saptaṛishis also, and that their 0 longitude was in Kṛittikā (which was an ancient reckoning), the epoch referred to by Varāhamihira would be circa 2500 B.C. to 2400 B.C., and Varāhamihira's year-date for Yudhishṭira's reign is actually A.D. 78 —2526 years=2448 B.C. See Paper (v) in the appendix " Astronomical references in the Mahābhārata."

- Vikrama era (expired year = A.D. year + 57). Extensively used at present in Guzerat and all over Northern India, except Bengal: Kārttikādi Amānta in Guzerat, hence called Southern Vikrama ; Chaitrādi and Pūrṇimānta in North India, hence called Northern Vikrama. Other names, "Malava era" ; and also simply "Saṃvat." The Vikrama years, expired, from A.D. 500 to A.D. 2000 are regularly shown in Table II, and from A.D. 700 to A.D. 1999 in the Ephemeris.

- Śaka era (expired year = A.D.. year minus 78). Extensively used in India both in the past, and at present. Meshādi (for solar year) and Chaitrādi (for luni-solar year) : generally amānta, but pūrṇimānta in Northern India. Śaka equivalents of Kaliyuga and Vikrama years, expired, from A.D. 500 to A.D. 2000, are regularly given in Table II, and from A.D. 700 to A.D. 1999 in the Ephemeris. Current śaka years are often quoted in inscriptions, in which case the formula is, current śaka = A.D. year minus 77.

- Kollam era (current year = A.D. year minus 824). Used in Malabar, Cochin, and Travancore since A.D. 825. Begins in North Malabar with solar Kanyā and in South Malabar with Chingam (Siṃha) ; always solar and current. English equivalents for all Kollam years are regularly given in the Ephemeris.

- Bengali san (or sen) (current year = A.D. year minus 593). Meshādi, current solar year. Now in use in Bengal. For A.D. 700 to A.D. 1999, B. san equivalents are regularly given in the Ephemeris, but they are given as expired years; and to find the current Bengal san, add one to the Ephemeris number.

- Chedi or Kalachuri era (current year = A.D. year minus 247), current, Āśvinādi, pūrṇimānta.

A.D. 300 = Chedi 53 current

A.D. 400 = Chedi 153 current

A.D. 500 = Chedi 253 current

A.D. 600 = Chedi 353 current

A.D. 700 = Chedi 453 current

A.D. 800 = Chedi 553 current.

A.D. 900 = Chedi 653 current

A.D. 1000 = Chedi 753 current

A.D. 1100 = Chedi 853 current

A.D. 1200 = Chedi 953

Not now in use, but was in use under the Kalachuri kings in Western and Central India.

- Gupta (current year = A.D. year minus 319).

A.D. 400 = Gupta 81 current

A.D. 500 = Gupta 181 current

A.D. 600 = Gupta 281 current

A.D. 700 = Gupta 381 current

Not now in use. Was in use in Central India and Nepal in the centuries above indicated as current, Chaitrādi, pūrṇimānta.

- Valābhi era (current year = A.D. year minus 318). Current, Kārttikādi, amānta, or pūrṇimānta.

A.D. 400 = Valabhi 82 current

A.D. 500 = Valabhi 182 current

A.D. 600 = Valabhi 282 current

A.D. 700 = Valabhi 382 current

A.D. 800 = Valabhi 482 current

A.D. 900 = Valabhi 582 current

A.D. 1000 = Valabhi 682 current

A.D. 1100 = Valabhi 782 current

A.D. 1200 = Valabhi 882 current

A.D. 1300 = Valabhi 982 current

Not now in use. Was in use in Kathiavad and neighbourhood in centuries above indicated.

- Vilāyati year (current year = A.D. year minus 592). Kanyādi, solar, current.

Now in use in Orissa. Months begin invariably on the day of saṅkrānti instead of the next or the third day after.

This era bears to the Bengali san pretty much the same relation that the Valābhi bore to the Gupta era.

- Amli year (current year = A.D. year minus 592). Luni-solar, current. Lunar year changes in Bhādrapāda śukla 12th, i.e., some days before, or some days after, Kanyā saṅkrānti. Otherwise the same as Vilāyati. Current in Orissa. Probably bears the same relation to Vilāyati that the luni-solar year in the Telugu country bears to the solar year of the Tamil country (i.e., only new year day is different in each case).

Fasli year (luni-solar) in Bengal, and N.W. India (current year = A.D. year minus 592); pūrṇimānta and lunar Āśvinādi (i.e., it begins on pūrṇimānta Āśvina, bahula pratipad) ; luni-solar year for Bengal, just as the Bengal san is the solar year for the same tract of country. Like all luni-solar years, the fasli takes the number of the next solar san. Thus, A.D. 1900 was, Bengal san 1307 current, but the luni-solar fasli beginning on Āśvina kṛishṇa pratipad of A.D. 1900 takes the number of the next Bengal san, i.e., 1308 current. Hence the formula for Bengal fasli is "current A.D. year minus 592."

Dakhan fasli (current year = A.D. year minus 593) was up to A.D. 1556 when its number was 963, a Hijra year, but from that year forward it has been kept as a solar year (identical in number with Bengal san), beginning, in parts of Bombay, when the sun enters the nakshatra Mṛigaśiras, i.e. (now) about 7th or 8th June. The months, their periods of beginning, and number of days are the same as in the Muhammadan calendar.

The Madras fasli year is an agricultural, solar, tropical year, beginning on 1st July and having no divisions of its own into months and days. Its formula is "Current fasli = A.D. year minus 590." The agricultural or revenue year from 1st July 1910 to 30th June 1911 might be expressed quite as well by the expression "Revenue year 1910-11" as by the expression "Fasli 1320." The former expression would convey better sense to most people, and the expression "Fasli year," the use of which a blind tradition has consecrated in Madras, serves no other purpose than to confuse any one who is not a village accountant or a Tahsildar. It is a chronological anomaly and will no doubt gradually drop out of use.

The Mahratta Sūr-san, shahūr-san or Arābi-san (current year = A.D. year minus 599) was extensively used under the Mahratta supremacy, and is still occasionally met with. Begins, like the Dakhan fasli, when the sun enters the nakshatra Mṛigaśiras.

Harshakāla era (current year = A.D. year minus 606). Was current in Muttra (Mathura) in Kanauj, Nepal. Harsha 94 current = A.D 700, and so on.

Nevar era (used in Nepal from A.D. 878 to A.D. 1768), expired, Kārttikādi Amānta. Formula " Nevar expired = A.D. year minus 879."

Nevar 21, expired = A.D. 900.

Nevar 821, expired = A.D. 1700.

Chalukya era (expired year = A.D. year minus 1076). This was in use only from A.D. 1079 to A.D. 1162. It followed the śaka months and pakshas. Chalukya 24 expired = A.D. 1100.

Lakshmaṇa Sena era : (expired year = A.D. year minus 1108, according to present day almanacs). Now in use in Tirhut and Mithila, but along with the śaka or Vikrama era.

Dr. Kielhorn concludes that the formula for this era was (from A.D. 1194 to A.D. 1551). "Expired Lakshmaṇa Sena year = A.D. year minus 1119." According to this formula A.D. 1200 would be equivalent to Lak. Sena 81, expired. The years of this era were expired, Kārttikādi, amānta.

Mahratta Rāja Śaka era (current year = A.D. year minus 1673) was established on the accession of Śivāji: the number of the year used to change every Jyeshṭha Śukla trayodaśī, which was the tithi or date of Śivāji's accession. Otherwise same as southern luni-solar amānta śaka years.

Tārikhi-i-Ilāhi (= mighty or divine era), dating from the accession of Akbar (14th February 1556), fell into disuse temp. Shah Jehan. Days and months were solar, without intercalations."

[Quelle: Swamikannu Pillai, L. D. (Lewis Dominic) <1865 - 1925>: An Indian ephemeris: A.D. 700 to A.D. 1799 : showing, the daily solar and lunar reckoning according to the principal systems current in India with their English equivalents, also the ending moments of tithis and nakshatras, and the years in different eras, A.D., Hijra, Śaka, Vikrama, Kaliyuga, Kollam, etc., with a a perpetual planetary almanac and other auxiliary tables. -- Reprint der Ausgabe von 1922. -- Delhi : Agam Prakashan, 1982. -- Band 1,1: General principles and tables. - IX, 500 S. -- 1. publ. 1922. -- A rev. and enl. ed. of: Indian chronology, 1911. -- S. 53 - 55]

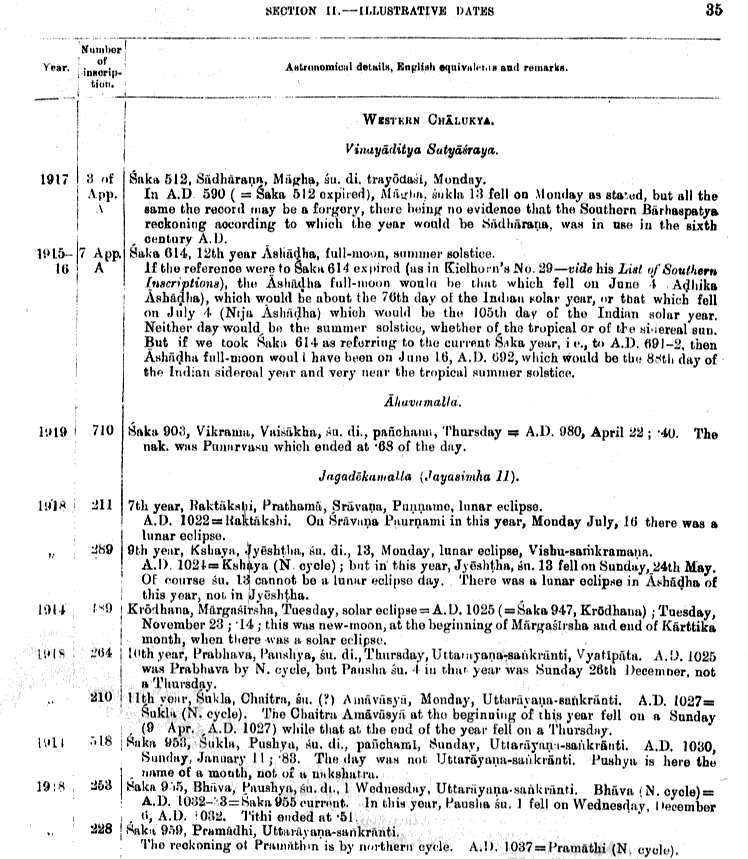

Inschriften sind oft sehr genau datiert. Mit der Hilfe von spezilisierten Chronologie-Fachleuten kann man Inschriften oft auf den Tag genau datieren. Es lohnt sich ein Blick auf die "Illustrative dates" aufgrund südindischer Inschriften in:

Swamikannu Pillai, L. D. (Lewis Dominic) <1865 - 1925>: An Indian ephemeris: A.D. 700 to A.D. 1799 : showing, the daily solar and lunar reckoning according to the principal systems current in India with their English equivalents, also the ending moments of tithis and nakshatras, and the years in different eras, A.D., Hijra, Śaka, Vikrama, Kaliyuga, Kollam, etc., with a a perpetual planetary almanac and other auxiliary tables. -- Reprint der Ausgabe von 1922. -- Delhi : Agam Prakashan, 1982. -- Band 1,2: Method of the ephemeris. Illustrations from S. Indian chronology. Ephemeris A.D. 700 - A.D. 799. -- 201 S. -- S. 34 - 139

Der folgende Anfang von Swamikannu Pillais diesbezüglichen Tabellen gibt einen ersten Eindruck davon, wie ein Kalenderfachmann arbeitet:

Die Typologie soll nur einen Eindruck von den Inhalten der Inschriften geben; die einzelnen Typen schließen sich nicht gegenseitig aus, sodass eine Inschrift mehreren Typen zugeordnet werden kann.

Richard Salomon schlägt folgende Typologie vor:

Salomon, Richard <1948 - >: Indian epigraphy : a guide to the study of inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan languages -- New York : Oxford University Press, ©1998. -- 378 S. : Ill. ; 24 cm. -- ISBN: 0195099842. -- S. 110 - 126

Stiftungsurkunden auf Kupferplatten sind sehr häufig überliefert. Sie sind eine unschätzbare Geschichtsquelle. Da die Stiftungs-Kupfertafeln sehr oft an Ort und Stelle gefunden werden, bilden Sie eine unerschöpfliche - noch kaum ausgenutzte - Quelle zur Lokalgeschichte ("Heimatgeschichte") und lokalen historischen Geographie (man kann oft sogar noch die einzelnen landwirtschaftlichen Felder identifizieren).

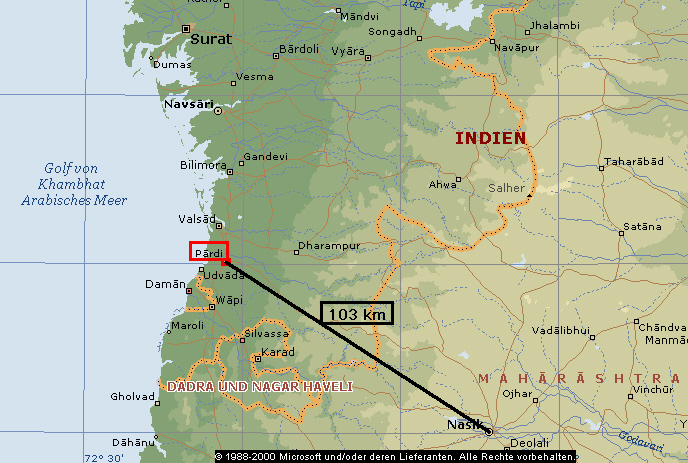

Als Beispiel weine kurze Stiftungsurkunde des Königs Dahrasena an den Brahmanen Naṇṇasvāmin, im Jahr 207 (= 4. April 456 n. Chr. (varttamāna = laufendes Jahr) oder 23. April 457 n. Chr. (gata = vergangenes Jahr). Die Kupferplatte stammt aus Pārḍī, Gujarat.

Abb.: Lage von Pardi

[©MS Encarta]

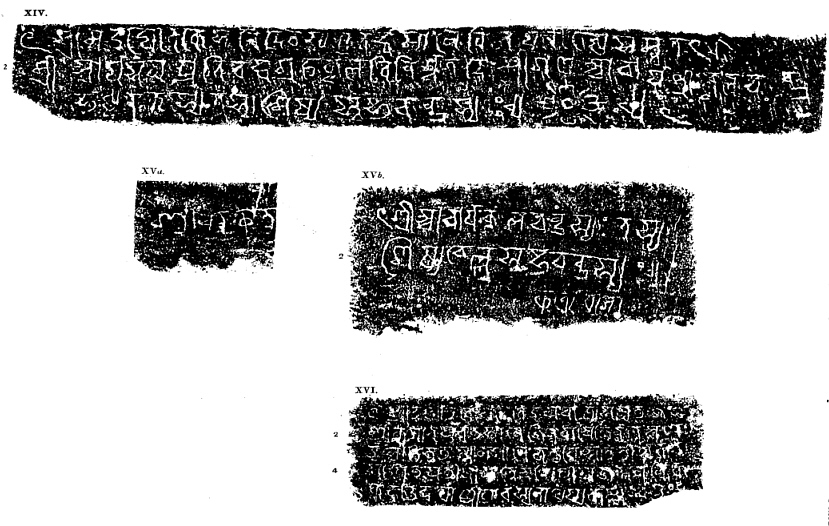

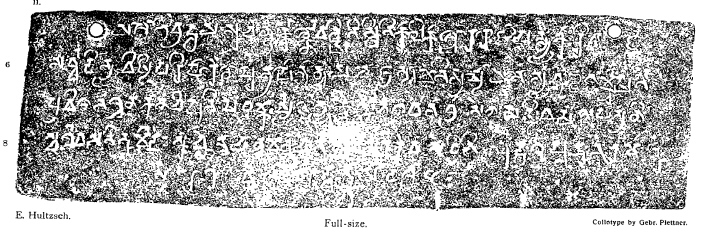

Abb.: Tintenabdruck der Kupferplatte

[Bildquelle: Epigraphia Indica. -- 10 (1909/10). -- Nach S.

52]

"(Line 1.) Hail ! From the camp of viotory pitched at Āmrakā, the glorious Mahārāja Dahrasena, (who belongs to the family) of the Traikūṭakas, who meditates on the feet of (his) mother and father, who is a servant of tbe feet of Bhagavat (Vishṇu), (and) who has performed an aśvamedha, addresses (the following) order to all Our subjects living in the Antarmaṇḍalī district (vishaya): (L.3.)"(We) have granted to the Brāhmaṇa Naṇṇasvāmin, residing in Kāpura, the village Kanīyas-Taḍākāsārikā included in this same district, for the increase of the merit and fame of (Our) mother and father and of Qurself, for as long as the moon, the sun, the ocean and the earth shall exist, to the exclusion of robbers and of those who do harm to the king, with exemption from all taxes and from forced labour, to be enjoyed by (his) sons, grandsons, (and further) descendants.

(L. 6.)"Therefore nobody shall cause obstruction to him while he enjoys, cultivates, and assigns (this land)"

(L. 7.) And the holy Vyāsa has spoken :

[Here follows one of the customary verses.]

(L. 8.) (This) order (was issued), -- Buddhagupta being the messenger (dūtaka),--in the year 207, on the thirteenth -- 13th (tithi) -- of the bright (fortnight) of Vaiśākha."

[Quelle: Hultzsch, Eugen <1857 - 1927>: Pardi plates of Dharasena; the year 207. -- In Epigraphia Indica. -- 10 (1909/10). -- S. 54.]

Hultzsch macht zu diesen Stiftungsplatten u.a. folgende Angaben:

"I re-edit this inscription from some excellent ink-impressions kindly made over to me by Dr. Fleet, who contributes the following remarks on tlie original copper-plates. " These plates were found in 1884 in the course of digging a tank at Pārḍī, the head-quarters town of the Pārḍī subdivision of the Surat District in Gujarāt, Bombay. The record on them was-bronght to notice and edited in 1885 by Pandit Bhagwanlal Indraji, without a lithograph, in the Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XVI. p. 346 ff.

" The plates are two in number, each measuring about 9 3/16" by 3". They are quite smooth ; the edges of them being neither fashioned thicker nor raised into rims : but, as may be seen from the facsimile, the inscription is in a state of perfect preservation almost throughout. They are somewhat thin, so that the letters, though not very deep, show through on the backs of them, to such an extent that some of them can be read there. The interiors of the letters show marks of the working of the engraver's tool.

" There is no ring of the ordinary kind, with a seal on it. But at each of the two ringholes the plates were held together by a long copper wire, 1/8" thick in the thickest part, which, after being passed through the ring-holes, had its ends twisted over and round and round so as to form a kind of complicated tie, without the ends being soldered together. As the ring-holes are not much larger than the wires, and as the plates appear to have been secured as soon as they were discovered, it would seem that these wires are the means by which the plates were fastened together ab initio.

"The weight of the two plates is 31 tolas, and of the two wires 1½ tolas ; total, 32½ tolas = 12¾ oz."

[Quelle: Hultzsch, Eugen <1857 - 1927>: Pardi plates of Dharasena; the year 207. -- In Epigraphia Indica. -- 10 (1909/10). -- S. 51.]

Ein Teil der Quellensammlungen und Periodika ist leicht zugänglich im Internet Archive: http://www.archive.org/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-04

Grundlegende Quellensammlungen:

Abb.: Titelblatt von Bd. II,2

|

|

Sten Konow (1867 - 1948); Professor in Kopenhagen (1910), Hamburg (1914), Oslo (1919) |

Corpus inscriptionum indicarum. -- 1877ff. -- 36 cm.

Vol. I: Inscriptions of Asoka / new ed. By E. Hultzsch. With 55 plates. -- 1925. -- cxxxi, 260 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm. -- Supersedes: Inscriptions of Asoka / Prepared by Alexander Cunningham. -- Calcutta, 1887.

Vol. II, 1: Kharoshṭhī inscriptions, with the exception of those of Aśoka / ed by Sten Konow. -- 1929. -- cxxvii, 192 S. Ill. ; 29 cm.

Vol. II, 2: Bharhut inscriptions / edited by H. Lüders ; rev. by E. Waldschmidt and M. A. Mehendale. -- 1963. -- xxxviii, 201 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm.

Vol. III: Inscriptions of the early Gupta kings / [ed. by John Faithfull Fleet] ; revised by Devadatta Ramakrishna Bhandarkar ; edited by Bahadurchand Chhabra & Govind Swamirao Gai. -- 1981. -- xiv, 399 S. : Ill. ; 33 cm.

Vol. IV,1,2: Inscriptions of the Kalachuri-Chedi era / edited by Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi. -- 1955. -- 2 Bde ; 35 cm.

Vol. V: Inscriptions of the Vākāṭakas / edited by Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi. -- 1963. -- lxxvi, 141 S. : Ill. ; 35 cm.

Vol. VI: Inscriptions of the Śilāhāras / edited by Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi. -- 1977. -- xxiii, xci, 311 S. : Ill. ; 33 cm.

Vol. VII,1,2,3: Inscriptions of the Paramāras, Chandēllas, Kachchapaghātas, and two minor dynasties / edited by Harihar Vitthal Trivedi. -- 1978-1991. -- 3 Bde. : Ill. ; 36 cm.

Abb.: Titelblatt

|

|

Eugen Hultzsch (1857 - 1927) |

South Indian inscriptions / publ. by the Director General Archaeological Survey of India. - New Delhi

Titel teilw. auch: South-Indian inscriptions. - Bde. teilw. in Madras, Govt. Pr., teilw. in Delhi, Manager of Publ., erschienen. - Bde. teilw. in der Reihe New imperial series erschienen

Band 1: Tamil and Sanskrit : from stone and copper-plate edicts at Mamallapuram, Kanchipuram, in the north Arcot district, and other parts of the Madras presidency ; chiefly collected in 1886 - 87 / ed. and transl. by E. Hultzsch. - Madras, 1890. -- ([New Imperial series ; 9]) (New series ; 3) (Southern India ; 2)

Band 2: Tamil inscriptions of Rajaraja, Rajendra-chola, and others in the Rajarajesvara Temple at Tanjavur ;

P. 1: Inscriptions on the walls of the central shrine / ed. and transl. by E. Hultzsch. - Madras, 1891. -- ([New Imperial series ; 10])([Southern India ; 5])

P. 2: Inscriptions on the walls of the enclosure / ed. and transl. by E. Hultzsch. - Madras, 1892. -- ([New Imperial series ; 10])([Southern India ; 5])

P. 3: Supplement to the first and second volumes / ed. and transl. by E. Hultzsch. - Madras, 1895. -- (New Imperial series ; 10)([Southern India ; 5])

P. 4: Other inscriptions of the

Temple / ed. and transl. by V. Venkayya. - 1913. - (New imperial series

; 10)

P. 5: Pallaya copper-plate grants from Velurpalayam and Tandantottam :

including title page, preface, table of contents, list of plates,

addenda and corrigenda, introduction and index of volume 2 / ed. and

transl. by H. Krishna Sastri. - 1916. -- (New Imperial series ; 10)

Band 3: Miscellaneous inscriptions from the Tamil country

P. 1: Inscriptions at Ukkal, Melpadi, Karuvur, Manimangalam and Tiruvallam / ed. and transl. by E. Hultzsch. -- Madras, 1899. -- (New Imperial series ; 29)(Southern India ; 10)

P. 2: Inscriptions of Virarajendra I., Kulottunga-chola I., Vikram-Chola and Kulottunga-Chola III. / ed. and transl. by E. Hultzsch. -- Madras. -- (New Imperial series ; 29)(Southern India ; 10)

P. 3: Inscriptions of Aditya I, Parantaka I, Madiraikonda, Rajakesarivarman, Parantaka II, Uttama-chola, Parthivendravarman and Aditya-karikala and the Tiruvalangadu plates of Rajendra-chola I / ed. and transl. by H. Krishna Sastri. - 1920. - S. 222 - 439. -- (New Imperial series ; 29)

Band 4: {Miscellaneous inscriptions from the Tamil, Telugu and Kannada countries and Ceylon} / ed. by H. Krishna Sastri. - 1923. - VI, 496 S. : Faks.Taf. -- (New Imperial series / Archaeological Survey of India ; 44)

Band 5: {Miscellaneous inscriptions in Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu and Kannada}.

Band 6: {Miscellaneous inscriptions in Tamil, Telugu and Kannada}.

Band 7: {Miscellaneous inscriptions in Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu and Kannada}.

Band 8: {Miscellaneous inscriptions in Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu and Kannada}.

Band 9: Miscellaneous inscriptions Kannada

P. 1

P. 2

Band 10: {Telugu inscriptions from Andhra Pradesh}.

Band 11: {Bombay-Karnataka inscriptions}.

P. 1. -- 1940

P. 2. -- 1952

Band 12: {Pallava inscriptions}.

Band 13: Chola inscriptions}. -- 1952

Band 14: The {Pandyas} / ed. by A. S. Ramanatha Ayyar. - 1962

Band 15: {Bombay-Karnatak inscriptions} : vol. 2 / ed. by P. B. Desai. - 1964

Band 16: {Telugu inscriptions of the Vijayanagara dynasty} / ed. by H. K. Narasimhaswami. - 1972

Band 17: {Inscriptions collected during the year 1903 - 04} / ed. by K. G. Krishnan. - 1964

Band 19: {Inscriptions of Parakesarivarman} / publ. by the Director General, Archaeological Survey of India.

Band 20: {Bombay-Karnatak inscriptions} : vol. 4 / ed. by G. S. Gai.

Band 22:

1. (Inscriptions collected during the year 1905-06) / Archaeological Survey of India ; General ed. G. S. Gai ; Iss. by K. V. Ramesh. -- 1983.

2. Inscriptions collected during the year 1906 / Archaeological Survey of India ; ed. by G. V. Srinivasa Rao. -- 1997.

3. (Inscriptions collected during the year 1906) / Archaeological Survey of India ; ed. by G. V. Srinivasa Rao. - 1999.

Band 24: ({Inscriptions of the Ranganathasvami Temple, Srirangam}) / gen. ed. P. R. Srinivasan ... -- 1982

Band 26: (Inscriptions collected during the year 1908-09) / publ. by the Director-General, Archaeological Survey of India. Ed. by P. R. Srinivasan. - 1990.

Band 27 / ed. by M. D. Sampath ... - 2001.

Abb.: Titelblatt

Epigraphia Carnatica. -- Bangalore. -- Neuaufl. u.d.T.: {Epigraphiya Karnataka}. -- Wechselnde Verlage u. Orte. -- In wechselnden Gesamttiteln erschienen.

Band 1: Coorg Inscriptions / publ. for Government by B. Lewis Rice. -- 1886

Band 2: Inscriptions at Śravaṇa Belgoḷa / publ. for Government by B. Lewis Rice. -- 1889

Band 3: Inscriptions in the Mysore District. -- Part 1. / publ. for Government by B. Lewis Rice. -- 1894

Band 4: Inscriptions in the Mysore District. -- Part 2. / publ. for Government by B. Lewis Rice. -- 1898

Band 5: (Inscriptions in the Hassan District / publ. for Government by B. Lewis Rice). -- 2 Bde. -- 1902

Band 6: Inscriptions in the Kadur District / publ. for government by B. Lewis Rice. -- Rev. ed.. -- 1901

Band 7: (Inscriptions in the Shimoga District / publ. for government by B. Lewis Rice). -- Band 1. --(1902)

Band 7/8: Supplementary inscriptions in the Shimoga District / publ. by M. Seshadri. -- 1970

Band 10: Inscriptions in the Kolar District / publ. for Government by B. Lewis Rice. -- 1905

Band 11: Inscriptions in the Chitaldroog District / publ. for government by B. Lewis Rice. -- 1903. -- (Mysore archaeological series)

Band 12: Inscriptions in the Tumkur District / publ. for government by B. Lewis Rice. -- 1904. -- (Mysore archaeological series

Band 13,1: General index / publ. by M. H. Krishna. -- 1934. -- (Mysore archaeological survey)

Band 14: Supplementary inscriptions in the Mysore and Mandya Districts / publ. by M. H. Krishna. -- 1943. -- (Mysore archaeological survey)

Band 15: Supplementary inscriptions in the Hassan District / publ. by M. H. Krishna. -- 1943. -- (Mysore archaeological survey)

Band 16: Supplementary inscriptions in the Tumkur District / publ. by K. A. Nilakanta Sastri. -- 1955. -- (Mysore archaeological survey). -- Suppl. zu Vol. 12

Band 17: Supplementary inscriptions in the Kolar District / publ. by M. Seshadri. -- 1965

Inscriptions of Andhra Pradesh / Gen. ed. N. Ramesan. - Hyderabad : Governm. of Andhra Pradesh. -- (Epigraphical series ; ...)

Warangal district / by N. Venkataramanayya. -- 1974. -- (Epigraphical series ; 6)

Karimnagar district / ed. by P. V. Parabrahma Sastry. -- 1974 -- (Epigraphical series ; 8)

Cuddapah district. -- Part 1 / ed. by P. V. Parabrahma Sastry. -- 1977. -- (Epigraphical series ; 12)

Cuddapah district. -- Part 2 / ed. by P. V. Parabrahma Sastry. -- 1978. -- (Epigraphical series ; 13)

Cuddapah district. -- Part 3 / ed. by P. V. Parabrahma Sastry. -- 1981. -- (Epigraphical series ; 15)

Nalgonda district. -- Vol. 1 / ed. by P. V. Parabrahma Sastry. -- 1992. -- (Epigraphical series ; 21)

Nalgonda district. -- Vol. 2 / ed. by Nelaturi Venkataramanayya. -- 1994.-- (Epigraphical series ; 23)

Medak district / ed. by N. Mukunda Rao ... -- 2001. -- (Epigraphical series ; 24)

Abb.:

Titelblatt von Bd. XIII.

Epigraphia Indica / Archaeological Survey of India. -- 1.1888/92 - 42.1977/78 (1992) [damit Erscheinen eingestellt]. -- [Titel bis 24.1937/38: Epigraphia Indica and Record of the Archaeological Survey of India]. -- Index zu vol. 1 -34 als Anhang zu vol. 34 - 36. -- War das Hauptorgan der Veröffentlichung von Inschriften sowohl in indo-arischen als auch drawidischen Sprachen.

Arabische, persische und Urdu Inschriften (auch Bilinguen Sanskrit-Arabisch, Sanskit-Persisch):

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Epigraphia Indo-Moslemica / Archaeological Survey of India. - Delhi : Manager of Publ. -- 1907/08 - 1939/40(1949)1949/50(1954)

Fortsetzung:

Epigraphia Indica / Arabic and Persian supplement / Archaeological Survey of India, Department of Archeology. -- Delhi : Manager of Publ. -- 1951/52(1956) ff.

Studies in Indian epigraphy : journal of the Epigraphical Society of India = Bharatiya purabhilekha patrika. - Mysore : Geetha Book House. -- ISSN 0970-4760. -- 1.1974 - 3.1976(1977) ; 26.2000 ff. -- [Inschriften in lateinischer Transliteration mit Übersetzung]

4.1977 - 25.1999 unter dem Titel:

Journal of the Epigraphical Society of India = Bharatiya purabhilekha patrika. - Mysore : Soc. -- 4.1977(1978) - 25.1999

Annual report on epigraphy / Department of Archaeology. -- Madras. -- 1887 - 1922/23

Fortsetzung:

Annual report on South Indian epigraphy / Department of Archaeology. -- New Delhi [u.a.] : Gov. of India Press. --1923/24 - 1943/45(1955)

Fortsetzung:

Annual report on Indian epigraphy / Archaeological Survey of India. - New Delhi : Manager of Publications. -- ISSN 0970-0617. -- 1945/46(1951) ff.

Wichtige Quelle der Information über neu aufgefundene Inschriften sowie über Fragmente, die sonst nirgends veröffentlicht werden.

Eine handliche, aber leider nicht immer zuverlässige, Sammlung von Inschriften (ohne Übersetzung):

Abb.: Titelblatt

Select inscriptions bearing on Indian history and civilization / ed. by Dines Chandra Sircar. - Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass

Abb.: Titelblatt

Sircar, D. C. (Dines Chandra) <1907 – 1983>: Indian epigraphical glossary / D. C. Sircar. - 1. ed.. - Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass, 1966. - XII, 560 S. -- ISBN 81-208-0562-3

Fleet, J. F. (John Faithful) <1847-1917>: Indian Inscriptions (1910). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 3. Inschriften, 4.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-07. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen034.htm

Abb.: Umschlagtitel

Sircar, D. C. (Dines Chandra) <1907 –

1983>: Indian epigraphy. -- Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass, 1965. - XXI, 475, V

S. : Ill. -- [Standardwerk.]

Salomon, Richard <1948 - >: Indian epigraphy : a guide to the study of inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan languages -- New York : Oxford University Press, ©1998. -- 378 S. : Ill. ; 24 cm. -- ISBN: 0195099842. -- [Sehr gute Einführung.]

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Bühler, Georg <1837-1898>: Indische Palaeographie : von circa 350 A. Chr. - circa 1300 P. Chr.. -- Strassburg : Trübner, 1896. -- 96, IV S. ; 26 cm. + Siebzehn Tafeln zur Indischen Palaeographie (in Mappe). -- (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; 1. Bd., 11. Heft). -- [Pionierwerk]

Abb.: Titelblatt

Dani, Ahmad Hasan: Indian palaeography. -- Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1963. -- xviii, 297 S. : Ill. : 23 Schrifttafeln ; 23 cm.

Eine erste Orientierung über indische Schriften in:

Abb.: Titelblatt

Jensen, Hans <1884 - 1973>: Die Schrift in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. - 3., neubearb. und erw. Aufl. - Berlin <Ost> : Deutscher Verl. der Wissenschaften, 1969. - 607 S. : Ill. ; 28 cm. -- S.351 - 394

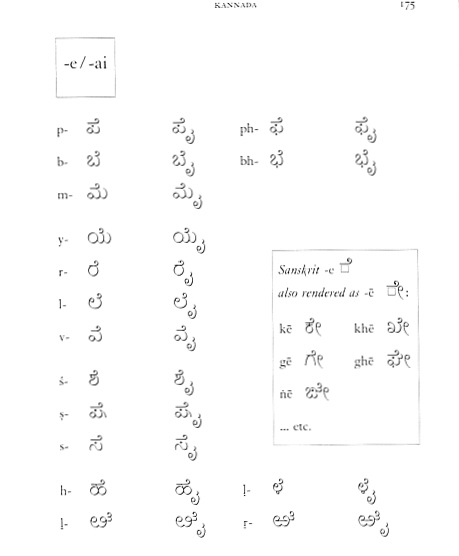

Einführung in die südindischen Schriften:

Abb.: Beispielseite

Grünendahl, Reinhold: South Indian scripts in

Sanskrit manuscripts and prints : Grantha Tamil - Malayalam - Telugu - Kannada -

Nandinagari. -- Wiesbaden : Harrassowitz, 2001. -- XXII, 224 S. ; 24 cm.

ISBN 3-447-04504-3

Schrifttafeln in elektronischer Form:

IndoSkript : eine elektronische indische Paläographie. -- Download: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~falk/index.htm. -- Zugriff am 2008-02-23

Literaturbericht:

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Falk, Harry: Schrift im alten Indien : ein Forschungsbericht mit Anmerkungen. -- Tübingen : Narr, 1993. -- 355 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- (ScriptOralia ; 56). -- ISBN 3-8233-4271-1

Fleet, J. F. (John Faithful) <1847-1917>: Hindu Chronology (1910). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 3. Inschriften, 5.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-07. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen035.htm

Abb.: Titelblatt

Swamikannu Pillai, L. D. (Lewis Dominic) <1865 - 1925>: An Indian ephemeris: A.D. 700 to A.D. 1799 : showing, the daily solar and lunar reckoning according to the principal systems current in India with their English equivalents, also the ending moments of tithis and nakshatras, and the years in different eras, A.D., Hijra, Śaka, Vikrama, Kaliyuga, Kollam, etc., with a a perpetual planetary almanac and other auxiliary tables. -- Reprint der Ausgabe von 1922. -- Delhi : Agam Prakashan, 1982. -- [Unentbehrliches Hilfsmittel]

Zu 1. Zum Beispiel: Aśoka-Inschriften