Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlassenschaften ("Ökofakte"). -- Fassung vom 2008-04-05. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen05.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2008-04-05

Überarbeitungen: 2008-07-16 [Ergänzungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Vorbemerkung:

In diesem Kapitel werden Texte zitiert bzw. wird auf Texte verwiesen, die Zustände nach 1858 wiedergeben. Dies geschieht nicht in der Annahme, dass die Zustände in Indien statisch waren; der "Fortschritt" in den Dörfern war aber gewiss so langsam, dass man von den geschilderten Zuständen vorsichtig auf Zustände früherer Zeiten extrapolieren darf. Die Texte sollen also vor allem einen Rahmen von Fragestellungen und möglichen Vorstellungen geben, in dem materielle unbewegliche Hinterlassenschaften als historische Quellen betrachtet werden können (vorsichtige Anwendung des ethnographischen Zugangs).

Die Auswahl der Bilder gibt keinen repräsentativen Querschnitt durch diese Art historischer Quellen, sondern ist in ihrer Einseitigkeit bedingt durch das Vorhandensein von Bildmaterial, das urheberrechtlich genutzt werden kann.

| "Als die »durchs Auge aufnehmbaren Reste«

der Vergangenheit hat der bedeutende deutsche Archäologe Ernst

Buschor den Gegenstand archäologischer Forschung bezeichnet. In der

Tat sind hier Zeugnisse geschichtlichen Lebens unserer Anschauung

unmittelbar zugänglich - Gräber und Festungsmauern, Tempel und

Hausruinen, Wasserleitungen und Töpferöfen genauso wie Waffen und

Gefäße, Arbeitsgeräte, Münzen und Kleidung." [Quelle: Maier, Franz Georg <1926 - >: Neue Wege in die alte Welt : Methoden d. modernen Archäologie. -- Hamburg : Hoffmann und Campe, 1977. -- 359 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- (Bausteine für ein modernes Weltbild). -- ISBN 3-455-08954-2. -- S. 13.] |

Ökofakten sind ein Teilgebiet von Sachzeugnissen (gegenständlichen Quellen) der Vergangenheit. Mit Thorsten Heese definiere ich diese so:

"Definition: Das Sachzeugnis als Quelle Gegenständliche Quellen sind materielle Überreste gelebter geschichtlicher Wirklichkeit. Als authentische, da unmittelbar überlieferte Materialisierungen vergangenen menschlichen Handelns zeugen sie von den Lebensumständen derjenigen Menschen, die sie geschaffen, benutzt und bewahrt haben. Sie bedürfen der Quellenkritik und -Interpretation."

"Definition: Das Sachzeugnis als Medium Gegenständliche Quellen sind materielle Medien für historisches Lernen, die Menschen früherer Zeiten selbst gewollt oder zufällig produziert haben. Sie besitzen einen monumentalen oder einen dokumentarischen Charakter."

[Quelle beider Zitate: Heese, Thorsten <1965 - >: Vergangenheit "begreifen" : die gegenständliche Quelle im Geschichtsunterricht. --Schwalbach/Ts. : Wochenschau-Verl. , 2007. -- 223 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- (Methoden historischen Lernens). -- ISBN 978-3-89974-331-9. -- S. 33, 35.]

Verschiedene Möglichkeiten diese gegenständlichen Quellen zu klassifizieren siehe in:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 6. Bewegliche Hinterlassenschaften. -- Fassung vom 2008-03-31. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen06.htm

Unter "Ökofakten" verstehe ich alle unbeweglichen Hinterlassenschaften von Einwirkungen des Menschen auf seine Umwelt. Dieses Kapitel ist auf die historische Zeit bis 1858 beschränkt, da die Quellen zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte schon behandelt wurden (http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen02.htm).

Solche Ökofakten sind u.a.

Die Untersuchung solcher "Ökofaktoren" ist Gegenstand vieler Fächer wie

Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon fasst 1905 "Archäologie" noch unter dem sehr engen Blickwinkel der Kunst und des Kunstgewerbes des klassischen (griechischen und römischen) Altertums:

""Archäologie (griech.), im allgemeinen soviel wie Altertumskunde; im engern Sinne nach modernem Sprachgebrauch die Wissenschaft, die sich mit der bildenden Kunst und dem Kunstgewerbe des klassischen Altertums beschäftigt. Als solche bildet sie einen Teil der Altertumswissenschaft, anderseits auch einen Teil der allgemeinen Kunstwissenschaft, ist neben dieser aber als besondere Wissenschaft berechtigt, weil sie ein im wesentlichen abgeschlossenes und abgegrenztes Gebiet bearbeitet. Die literarischen Quellen geben ihr die erste Richtschnur; weit mehr aber als alle verwandten Wissenschaften richtet sie ihre Studien auf die aus dem Altertum erhaltenen Denkmäler selbst, die sie in ihrem ganzen Umfange heranzieht." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

Demgegenüber fasst die 11. Auflage der Encyclopaedia Britannica "Archaeology" in einem weiten, noch heute gültigen, Sinn:

"ARCHAEOLOGY (from Gr. αρχαια, ancient things, and λογος, theory or science), a general term for the study of antiquities. The precise application of the term has varied from time to time with the progress of knowledge, according to the character of the subjects investigated and the purpose for which they were studied. At one time it was thought improper to use it in relation to any but the artistic remains of Greece and Rome, i. e. the so-called classical archaeology (now dealt with in this encyclopaedia under the headings of GREEK ART and ROMAN ART); but of late years it has commonly been accepted as including the whole range of ancient human activity, from the first traceable appearance of man on the earth to the middle ages. It may thus be conceived how vast a field archaeology embraces, and how intimately it is connected with the sciences of geology (q.v.) and anthropology (q.v.), while it naturally includes within its borders the consideration of all the civilizations of ancient times. In dealing with so vast a subject, it becomes necessary to distinguish. The archaeology of zoological species constitutes the sphere of palaeontology (q.v.), while that of botanical species is dealt with as palaeobotany (q.v.) ; and every different science thus has its archaeological side. For practical purposes it is now convenient to separate the sphere of archaeology in its relation to the study of the purely artistic character of ancient remains, from that of the investigation of these remains as an instrument for arriving at conclusions as to the political and social history of the nations of antiquity; and in this work the former is regarded primarily as "art" and dealt with in the articles devoted to the history of art or the separate arts, while "archaeology" is particularly regarded as the study of the evidences for the history of mankind, whether or not the remains are themselves artistically and aesthetically valuable. In this sense a knowledge of the archaeology is part of the materials from which every historical article in this encyclopaedia is constructed, and in recent years no subject has been more fertile in yielding information than "archaeology," as representing the work of trained excavators and students of antiquity in all parts of the world, but notably in the countries round the Mediterranean.

It is for its services in illuminating the days before those of documentary history and for checking and reinforcing the evidence of the raw material (the "unwritten history" of architecture, tombs, art-products, &c.), that recent archaeological work has been so notable. The work of the literary critic and historian has been amplified by the spade-work of the expert excavator and explorer to an extent undreamt of by former generations; and ancient remains, instead of being treated merely as interesting objects of art, have been forced to give up their secret to the historian, as evidence for the period, character and affiliations of the peoples who produced and used them.

The increase of precise knowledge of the past, due to greater opportunities of topographical research, more care and observation in dealing with ancient remains and improved methods of studying them in museums (q.v.) and collections, has led to more accurate reading of results by a comparison of views, under the auspices of learned societies and institutions, thus raising archaeology from among the more empirical branches of learning into the region of the more exact sciences. This change has improved not only the status of archaeology but also its material, for the higher standard of work now demanded necessarily acts as a deterrent on the poorly equipped worker, and the tendency is for the general result to be of a higher quality."

[Quelle: Charles Hercules Read <1857 - 1929>: Archaeology. -- In: Encyclopaedia Britannica. -- 11th ed. -- 1910. -- Vol. 2. -- S. 344]

Ich verstehe hier Archäologie als das Studium der physischen Überreste menschlicher Vergangenheit (bis in die jüngste Vergangenheit). Ich kann die Definition der englischsprachigen Wikipedia übernehmen:

"Archaeology, archeology, or archæology (from Greek: αρχαιολογία - archaiologia, from αρχαίος - archaios, "primal, ancient, old" and λόγος - logos, "study") is the science that studies human cultures through the recovery, documentation, analysis and interpretation of material remains and environmental data, including architecture, artefacts, features, biofacts, and landscapes. Because archaeology's aim is to understand mankind, it is a humanistic endeavour." [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaeology. -- ZUgriff am 2008-03-21]

Archäologische Quellen in diesem Sinne sind also physische/materielle Überreste und Hinterlassenschaften menschlicher Tätigkeit.

1784-01-15

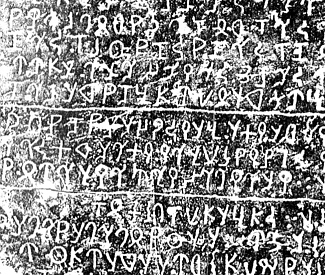

Abb.: Sir William Jones

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia, Public domain]

Sir William Jones (1746 – 1794) gründet in Calcutta The Asiatic Society (Webpräsenz: http://www.asiaticsocietycal.com/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-20). Obwohl W. Jones selbst kein Archäologe war, hatte er durch die Gründung der Asiatic Society einen unüberschätzbaren Einfluss auf das antiquarisch-archäologische Interesse in Indien.

"JONES, SIR WILLIAM (1746-1794), British Orientalist and jurist, was born in London on the 28th of September 1746. He distinguished himself at Harrow, and during his last three years there applied himself to the study of Oriental languages, teaching himself the rudiments of Arabic, and reading Hebrew with tolerable ease. In his vacations he improved his acquaintance with French and Italian. In 1764 Jones entered University College, Oxford, where he continued to study Oriental literature, and perfected himself in Persian and Arabic by the aid of a Syrian Mirza, whom he had discovered and brought from London. He added to his knowledge of Hebrew and made considerable progress in Italian, Spanish and Portuguese. He began the study of Chinese, and made himself master of the radical characters of that language. During five years he partly supported himself by acting as tutor to Lord Althorpe, afterwards the second Earl Spencer, and in 1766 he obtained a fellowship. Though but twenty-two years of age, he was already becoming famous as an Orientalist, and when Christian VII. of Denmark visited England in 1768, bringing with him a life of Nadir Shah in Persian, Jones was requested to translate the MS. into French. The translation appeared in 1770, with an introduction containing a description of Asia and a short history of Persia. This was followed in the same year by a Traité sur la poesie orientale, and by a French metrical translation of the odes of Hafiz. In 1771 he published a Dissertation sur la litterature orientale, defending Oxford scholars against the criticisms made by Anquetil Du Perron in the introduction to his translation of the Zend-Avesta. In the same year appeared his Grammar of the Persian Language. In 1772 Jones published a volume of Poems, Chiefly Translations from Asiatick Languages, together with Two Essays on the Poetry of Eastern Nations and on the Arts commonly called Imitative, and in 1774 a treatise entitled Poeseos Asiaticae commentatorium libri sex, which definitely confirmed his authority as an Oriental scholar. Finding that some more financially profitable occupation was necessary, Jones devoted himself with his customary energy to the study of the law, and was called to the bar at the Middle Temple in 1774. He studied not merely the technicalities, but the philosophy, of law, and within two years had acquired so considerable a reputation that he was in 1776 appointed commissioner in bankruptcy. Besides writing an Essay on the Law of Bailments, which enjoyed a high reputation both in England and America, Jones translated, in 1778, the speeches of Isaeus on the Athenian right of inheritance. In 1780 he was a parliamentary candidate for the university of Oxford, but withdrew from the contest before the day of election, as he found he had no chance of success owing to his Liberal opinions, especially on the questions of the American War and of the slave trade.

In 1783 was published his translation of the seven ancient Arabic poems called Moallakāt. In the same year he was appointed judge of the supreme court of judicature at Calcutta, then "Fort William," and was knighted. Shortly after his arrival in India he founded, in January 1784, the Bengal Asiatic Society, of which he remained president till his death. Convinced as he was of the great importance of consulting the Hindu legal authorities in the original, he at once began the study of Sanskrit, and undertook, in 1788, the colossal task of compiling a digest of Hindu and Mahommedan law. This he did not live to complete, but he published the admirable beginnings of it in his Institutes of Hindu Law, or the Ordinances of Manu (1794); his Mohammedan Law of Succession to Property of Intestates; and his Mohammedan Law of Inheritance (1792). In 1789 Jones had completed his translation of Kālidāsa's most famous drama, Śakuntalā. He also translated the collection of fables entitled the Hitopadeśa, the Gītagovinda, and considerable portions of the Vedas, besides editing the text of Kālidāsa's poem Ritusaṃhara. He was a large contributor also to his society's volumes of Asiatic Researches.

His unremitting literary labours, together with his heavy judicial work, told on his health after a ten years' residence in Bengal; and he died at Calcutta on the 27th of April 1794. An extraordinary linguist, knowing thirteen languages well, and having a moderate acquaintance with twenty-eight others, his range of knowledge was enormous. As a pioneer in Sanskrit learning and as founder of the Asiatic Society he rendered the language and literature of the ancient Hindus accessible to European scholars, and thus became the indirect cause of later achievements in the field of Sanskrit and comparative philology. A monument to his memory was erected by the East India Company in St Paul's, London, and a statue in Calcutta.

See the Memoir (1804) by Lord Teignmouth, published in the collected edition of Sir W. Jones's works."

[Quelle: The Encyclopaedia Britannica. -- 11th. ed. -- Vol. 15. -- 1911. -- S. 501.]

1788

Es erscheinen erstmals die von der Asiatic Society herausgegeben

Asiatic researches or transactions of the Society instituted in Bengal, for inquiring into the history and antiquities, the arts, sciences, and literature, of Asia. -- Calcutta. -- 1.1788 - 20.1836/39 [geht dann auf in: Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. -- Calcutta : Soc. -- 1.1832 - 33.1864(1865)

1807 - 1814

Der Botaniker und Zoologe Francis Buchanan-Hamilton (1762 - 1829) macht im Auftrag der East India Company eine große Bestandsaufnahme (Survey) der von der Company kontrollierten Gebiete, neben vielem anderen gehört dazu auch eine Bestandsaufnahme der Altertümer.

1814

Der dänische Botaniker Dr. Nathaniel Wallich (1786 - 1854) gründet in Calcutta das Indian Museum (Webpräsenz: http://www.indianmuseumkolkata.org/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-20)

1833

James Prinsep (1799 - 1840) wird Sekretär des Asiatic Society. Er wird bahnbrechend in Numismatik und Epigraphie.

1841

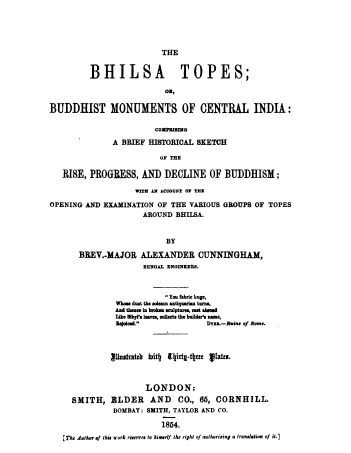

Abb.: TitelblattWilson, H. H. (Horace Hayman) <1786-1860>: Ariana antiqua : a descriptive account of the antiquities and coins of Afghanistan / by H. H. Wilson. With a memoir on the building called topes, by C. Masson. -- London : East India Company, 1841. -- XVI, 452 S, XXII Bl. : Ill.

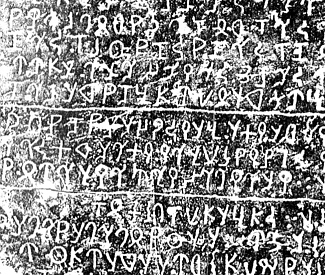

Abb.: Tafel aus diesem Werk

"WILSON, HORACE HAYMAN (1786-1860), English orientalist, was born in London on the 26th of September 1786. He studied medicine at St Thomas's Hospital, and went out to India in 1808 as assistant-surgeon on the Bengal establishment of the East India Company. His knowledge of metallurgy caused him to be attached to the mint at Calcutta, where he was for a time associated with John Leyden. He became deeply interested in the ancient language and literature of India, and by the recommendation of Henry T. Colebrooke, he was in 1811 appointed secretary to the Asiatic Society of Bengal. In 1813 he published the Sanskrit text with a graceful, if somewhat free, translation in English rhymed verse of Kālidāsa's charming lyrical poem, the Meghadūta, or Cloud-Messenger. He prepared the first Sanskrit-English Dictionary (1819) from materials compiled by native scholars, supplemented by his own researches. This work was only superseded by the Sanskritwörterbuch (1853-1876) of R. von Roth and Otto Böhtlingk, who expressed their obligations to Wilson in the preface to their great work. Wilson published in 1827 Select Specimens of the Theatre of the Hindus, which contained a very full survey of the Indian drama, translations of six complete plays and short accounts of twenty-three others. His Mackenzie Collection (1828) is a descriptive catalogue of the extensive collection of Oriental, especially South Indian, MSS. and antiquities made by Colonel Colin Mackenzie, now deposited partly in the India Office, London, and partly at Madras. He also wrote a Historical Sketch of the First Burmese War, with Documents, Political and Geographical (1827), a Review of the External Commerce of Bengal from 1813 to 1828 (1830) and a History of British India from 1805 to 1833, in continuation of Mill's History (1844-1848). He acted for many years as secretary to the committee of public instruction, and superintended the studies of the Sanskrit College in Calcutta. He was one of the staunchest opponents of the proposal that English should be made the sole medium of instruction in native schools, and became for a time the object of bitter attacks. In 1832 the university of Oxford selected Dr Wilson to be the first occupant of the newly founded Boden chair of Sanskrit, and in 1836 he was appointed librarian to the East India Company. He was an original member of the Royal Asiatic Society, of which he was director from 1837 up to the time of his death, which took place in London on the 8th of May 1860. A full list of Wilson's works may be found in an Annual Report of the Royal Asiatic Society for 1860. A considerable number of Sanskrit MSS. (540 vols.) collected by Wilson in India are now in the Bodleian Library."

[Quelle: Encyclopaedia Britannica. -- 11th edition. -- 1911. -- Vol. 28. -- S. 692f.]

1854

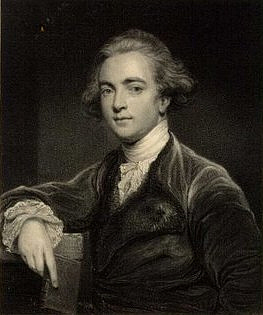

Abb.: Titelblatt

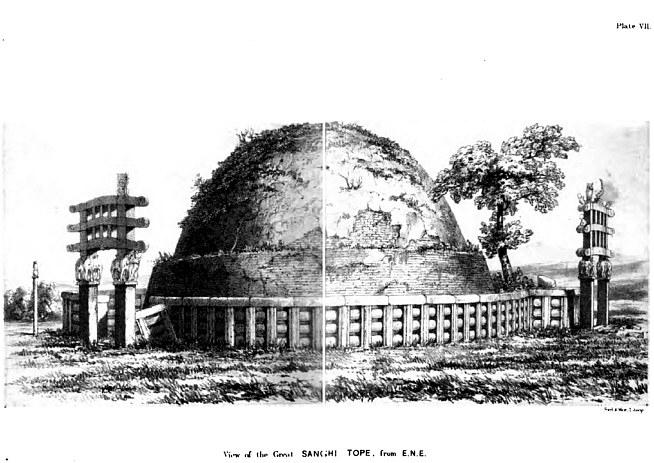

Abb.: Darstellung des Stūpa von Sanchi (साँची) in diesem Werk (Pl. VII.)

Cunningham, Alexander <1814-1893>: The Bhilsa topes; or, Buddhist monuments of central India: comprising a brief historical sketch of the rise, progress, and decline of Buddhism; with an account of the opening and examination of the various groups of topes around Bhilsa. -- London, Smith, Elder, 1854. -- xxxvi, 368 S. : Ill ; 23 cm.

"Cunningham (spr. könning-äm), Alexander, namhafter Indianist und Archäolog, geb. 23. Jan. 1814 in London, gest. daselbst 28. Nov. 1893, ward auf dem Christ's Hospital und dem Military College zu Addiscombe gebildet und 1834 zum Adjutanten des Generalgouverneurs von Indien ernannt. Nachdem er 1839 in spezieller Mission in Kaschmir gewesen, wurde er 1840 Ingenieur des Königs von Audh, erhielt 1846 eine Mission nach Tibet und ward 1858 zum Oberingenieur der Nordwestprovinzen sowie 1870 zum archäologischen Generalinspektor von Indien ernannt, legte aber 1885 diese Stelle nieder. um nach England zurückzukehren. Außer antiquarischen Abhandlungen in Zeitschriften und den umfangreichen offiziellen Berichten über die Altertümer von Nordhindostan, die u. d. T.: »Archaeological survey of India« (1871ff., 23 Bde.; Index dazu von V. Smith, Kalkutta 1887) erschienen, hat Cunningham noch verfasst: »Essay on the Arian order of architecture« (1846); »Ladak, physical, statistical and historical« (1854); »The Bhilsa topes« (1854); »Ancient geography of India« (Bd. 1: »The Buddhist period«, 1871); »Corpus inscriptionum indicarum« (Lond. 1878, Bd. 1) u. a." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

1861

Alexander Cunningham (1814-1893) wird erster Archaeological Surveyor im auf seine Anregung gegründeten Archaeological Survey of India (Webpräsenz: http://asi.nic.in/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-20)

1866

Der Archaeological Survey of India wird aufgehoben.

1871

Der Archaeological Survey wird wieder institutionalisiert. Alexander Cunningham wird sein Director General.

1871

Abb.: TitelblattCunningham, Alexander <1814-1893>: Main Title: The ancient geography of India. London : Trübner. -- I. The Buddhist period including the campaigns of Alexander, and the travels of Hwen-Thsang. -- 1871. 501 S. : Ill. -- Pionierwerk der historischen Geographie

1872

Indian antiquary : a journal of oriental research in archaeology, history, literature, languages, folklore etc. -- 1.1872 - 62.1933. 3.Ser. 1.1964 - 5.1971 [damit Erscheinen eingestell] ; 14 - 62 auch gezählt als 2.Ser; 1938 - 1947: The new Indian antiquary : a monthly joournal of oriental research in archaeology ... and all subjects connected with indology. -- 1.1938/39 - 9.1947

Beilage: Epigraphia Indica

1878

Treasure Trove Act

1885

Retirement von Cunningham.

Neue Zuständigkeiten:

- James Burgess (1832 - 1916) für Madras, Bombay und Hyderabad wird zuständig, für dortige Epigraphie John Faithful Fleet (1847-1917)

- J. D. Beglar für Bengalen

- J. B. Keith mit Alois Führer (1853 - ) als Assistent für die Northwestern Provinces

- Charles James Rodgers (1838-1898) für den Panjab

1886

Eugen Hultzsch (1857 - 1927) wird Epigraphist to the Governement of Madras

1886

James Burgess (1832 - 1916) wird Director General des Archaeological Survey of India

1901/1902

John Hubert Marshall (1876 - 1958) wird Director General des Archaeological Survey of India.

Marshalls Prinzipien der archäologischen Konservierung:

"Hypothetical restorations were unwarranted, unless they were essential to the stability of a building;

Every original member of a building should be preserved in tact, and demolition and reconstruction should be undertaken only if the structure could not be otherwise maintained;

Restoration of carved stone, carved wood or plaster-moulding should be undertaken only if artisans were able to attain the excellence of the old; and

In no case should mythological or other scenes be re-carved."

[Quelle: http://asi.nic.in/asi_aboutus_history.asp. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-21]

1928

Harold Hargreaves (1876 - ) wird Director General des Archaeological Survey of India.

1931

Rai Bahadur Daya Ram Sahni (1879-1939) wird Director General des Archaeological Survey of India.

1935

J. F. Blakiston wird Director General des Archaeological Survey of India.

1937

Rao Bahadur K. N. (Kashinath Narayan) Dikshit (1889 - ) wird Director General des Archaeological Survey of India.

1944

Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler (1890 - 1976) wird Director General des Archaeological Survey of India. Er führt moderne stratigraphische Grabungsmethoden ein und beendet die Zeit des archäologischen Dilettantismus.

1948

N. P. Chakravarti wird Director General des Archaeological Survey of India.

Unbewegliche und bewegliche materielle Hinterlassenschaften sind vor allem auch Gegenstand der historischen Volkskunde sowie der Völkerkunde. Die historische Volkskunde erhielt in Europa und den USA einen großen -- auch methodischen -- Impuls durch die Konservierungsbemühungen in Freilichtmuseen (in der Schweiz vor allem das Freilichtmuseum Ballenberg).

Siehe:

Burgess, James <1832 - 1916>: Indian Architecture (1910). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlasenschaften, 2.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-21. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen052.htm

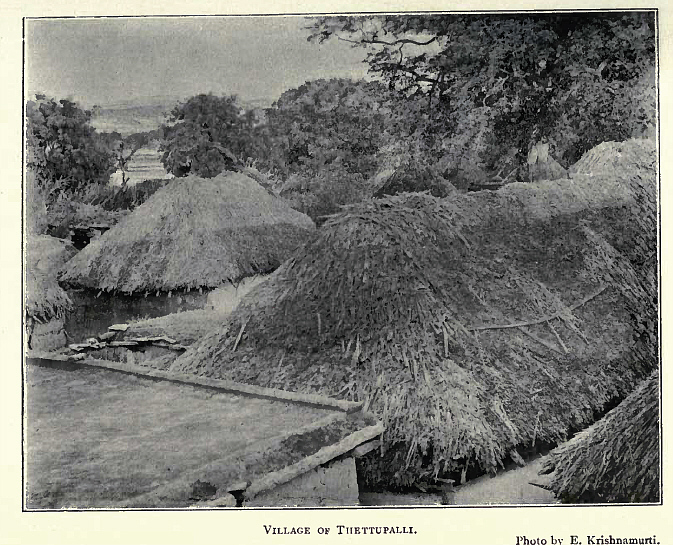

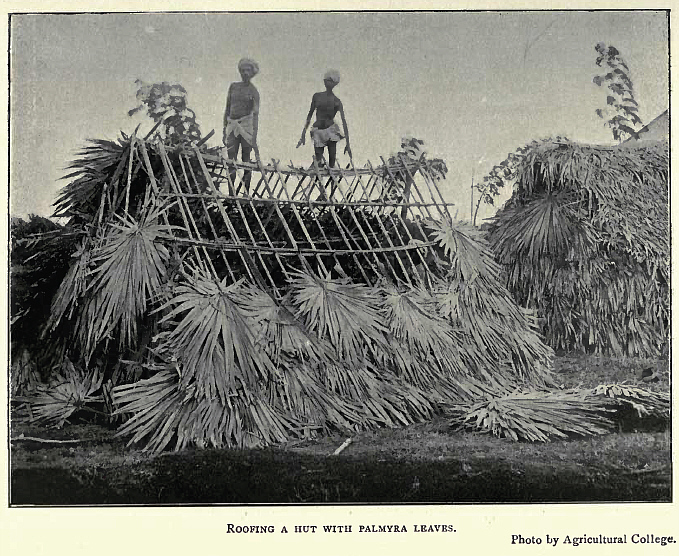

"Of the various sorts of houses in use, brick or stone and tiles, mud walls and thatch, bamboos and palm leaves, the last is still the commonest; but the brick and tile dwellings are increasing very rapidly." [Quelle: Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- S. 232. -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"]

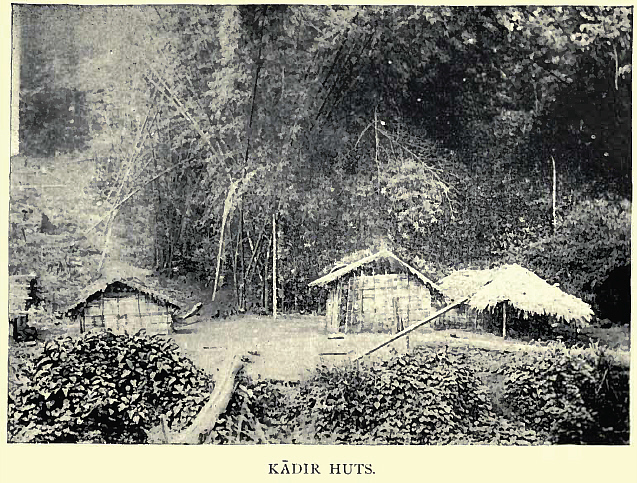

Abb.: Häuser von Kādirs, Anaimalai Hills (ஆனைமலை),

um 1909

[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 3. -- Nach S. 8.]

Abb.: Haus der Toda, Nīlgiri (நீலகிரி), um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 7. -- Nach S. 128.]

Abb.: Häuser in Thettupalli, Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- Nach S. 102. -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"]

Abb.: Dachdecken mit Blättern der Palmyrapalme (Borassus flabellifer),

Südindien, um 1918

[Bildquelle: Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- Nach S. 116. -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"]

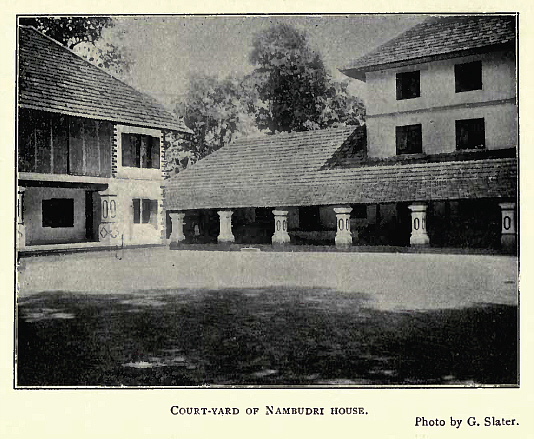

Abb.: Hof eines Hauses von Nambudiri-Brahmanen (നമ്പൂതിരി), Kerala, um 1918

[Bildquelle: Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- Nach S. 124. -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"]

Abb.: Eingang zum Haus eines Brahmanen mit Handabdrücken zur Abwehr des Bösen Blicks, Südindien, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 1. -- Nach S. 280s.]

Abb.: Haus eines Nambūtiri-Brahmanen, Kerala, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 5. -- Nach S. 176.]

Abb.: Nāyar-Haus (നായര്), Krerala, um 1901

[Bildquelle: Fawcett, F.: Nāyars of Malabar. -- Madras : Government Press, 1915. -- (Bulletin / Madras Government Museum ; Vol. III, No.3. -- Pl. XIV.]

F. Fawcett über Nāyar-Häuser:

"HABITATIONS. A house may face east or west ; never north or south. As a rule the Nāyar's house faces the east. Every garden is enclosed by a bank, a hedge, or a fencing of some kind, and entrance is to be made at one point only, the east, where there is a gate-house, or, as in the case of of the poorest houses a small portico, or open doorway roofed over. One never walks straight through this; there is always a kind of stile to surmount. It is the same everywhere in Malabar, and not only amongst the Nāyars. The following is a plan of a nālupura or foursided house, which may be taken as representative of the houses of the rich:

Numbers 6 and 7 are rooms which are used generally for storing grain.

At A is a staircase leading to the room of the upper story occupied by the female members of the family.

At B is a staircase to the rooms of the upper story [S. 304] occupied by the male members. There is no connection between the portions allotted to the men and that of the women. No, 8 is for the family gods. The Kārnavans and old women of the family are perpetuated in images of gold or silver, or, more commonly, brass. Poor people, who cannot afford to make these images, substitute simply a stone. Offerings are made to these images (or to the stones) at every full moon. The throat of a fowl will be cut outside, and the bird is then taken inside and offered.

The entrance is at C.

E. Rooms occupied by women and children.

It may be noticed that the apartment, where the men sleep, has no windows on the side of the house which is occupied by the women. The latter are relatively free from control by the men as to who may visit them. We saw, when speaking of funeral ceremonies, that a house was supposed to have a central courtyard; and of course it has this only when there are four sides to the house. The nālupura, or four-sided house, is the proper one for in this alone can all ceremonial be observed in orthodox fashion. But it is not the ordinary Nāyar's house that one sees all over Malabar. The ordinary house is, roughly, of the shape here indicated.

Invariably there is an upper story. There are no doors but only a few tiny windows opening to the west. Men sleep in one end, women in the other, each having their own staircase. Around the house there is always shade from many trees and palms. Every house is in its own seclusion."

[Bildquelle: Fawcett, F.: Nāyars of Malabar. -- Madras : Government Press, 1915. -- (Bulletin / Madras Government Museum ; Vol. III, No.3. -- S.303ff.]

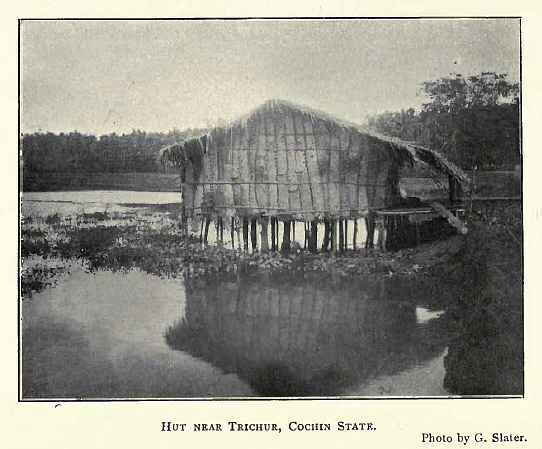

Abb.: Hütte bei Thrissur/Trichur (തൃശ്ശൂര്), Kerala, um 1918

[Bildquelle: Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- Nach S. 132. -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"]

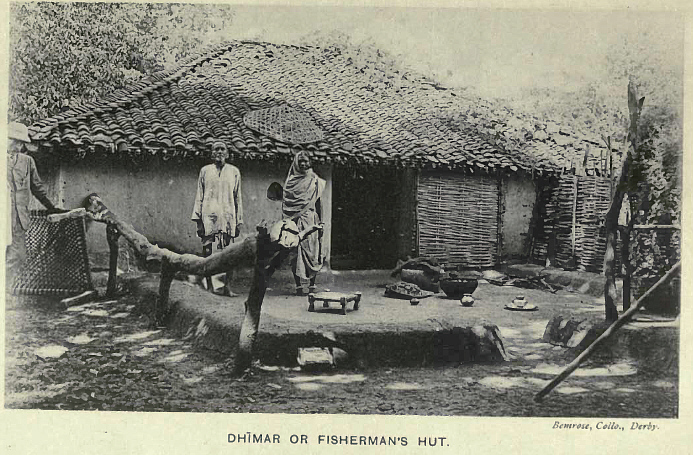

Abb. Haus eines Dhīmar (Fischers), Zentralindien, um 1916

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 2. -- Nach S. 502.]

Abb.: Haveli (Patrizierhaus) (حویلی, हवेली), Jaisalmer (जैसालमेर), Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: Dey. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/dey/7001570/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01. --Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

"HOUSE. In the granitic country of Telingana, the houses are usually built of adhesive earth or clay, of a square or rectangular form, smeared often with red earth, and picked out with perpendicular bands of slaked lime, with a pyramidal roof of palmyra leaves or grass. Houses in the Karnatic are of mud walls, with roofs thatched with grass or palm leaves. Houses on the banks of the Kistna, near its debouchure, have circular walls of adhesive earth.

In the Tamil and Telugu country, the walls are usually of mud, with thatch or tiles for the roof. The humbler races have circular houses ; their houses in Telingana are detached from each other, outside the gharri or fort. In the Canarese tract about Hurryhur, the back of the house is formed by raising a very high wall, on which a long sloping roof rests.

In Arabia and Mahomedan countries of Persia and India, houses have a common courtyard, with numerous rooms leading from it.

[...]

The cottage of Bengal, with its trim, curved, thatched roof, and cane or bamboo walls, is the best looking in India.

The houses of Hindustan are built of clay or unburnt bricks, and tiled.

In the greenstone tract of the Dekhan, Berar, and the Mahratta country, where wood is scarce and of high price, the walls are mostly of mud, with flat roofs. The houses are huddled close together, surrounded by a wall, often with a central gharri or fort.

Houses with a flat roof have a parapet to prevent any one falling into the street. Acts x. 9 tells us that 'Peter went upon the housetop to pray.' All the flat-roofed houses of India would admit of this ; but some of the rich Hindus have a room on the top of the house, in which they perform worship daily.

2 Samuel xi. 2 says, 'And it came to pass in an evening-tide, that David arose from off his bed, and walked upon the roof of the king's house.' It is common in India with Mahomedans and Hindus to sleep in the afternoon. The roofs of houses are flat, and it is a pleasing recreation in an evening to walk on the flat roofs.

Houses in many eastern countries are built as a quadrangle, the four outer walls being dead, or pierced with loopholes ; in one of the halls is the entrance to an open unroofed courtyard, surrounded by chambers or open verandahs."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 2. -- 1885. -- S. 115f.]

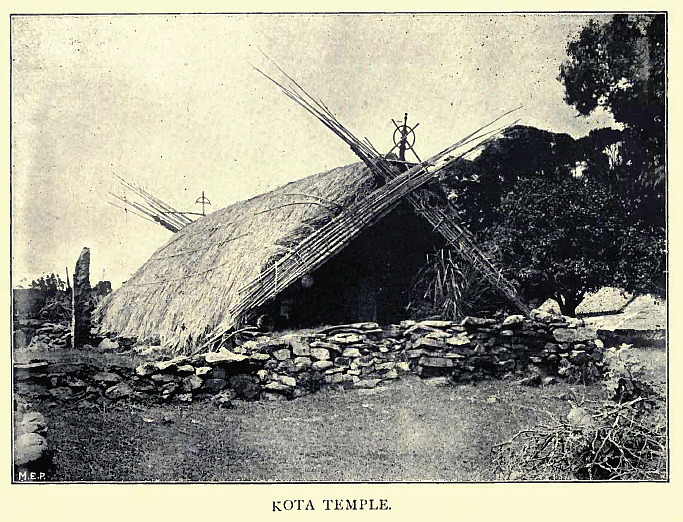

Abb.: Tempel der Kota, Nīlgiri (நீலகிரி), um 1909

[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 4. -- Nach S. 12.]

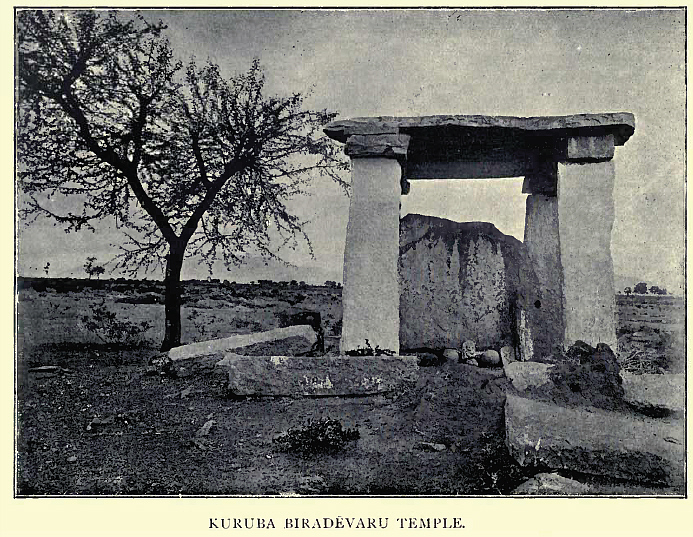

Abb.: Biradevaru-Tempel der Kuruba, Karnataka, um 1909

[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 4. -- Nach S. 152.]

Abb.: Māle (Ahnenkultstätte) der Tottiyan, Andhra Pradesh, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 7. -- Nach S. 196.]

Abb.: Schreineder Vāda (eine Fischerkaste), Andhra Pradesh, um 1909

[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 7. -- Nach S. 264.]

Abb.: Schlangensteine, Tamil Nadu, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 7. -- Nach S. .]

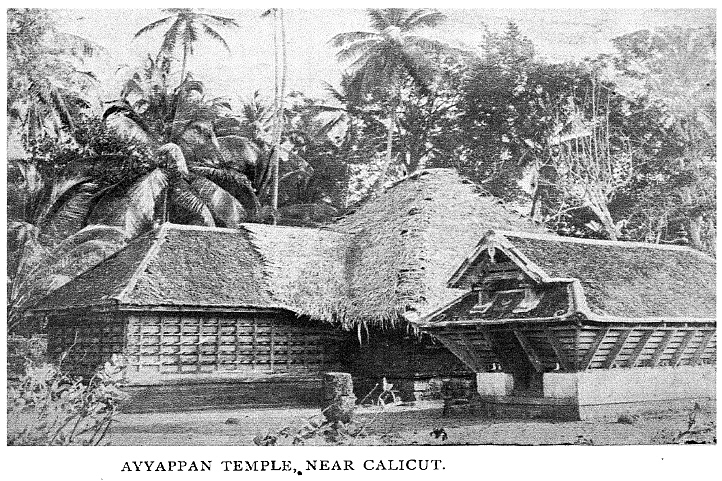

Abb.: Ayyappan-Tempel (അയ്യപ്പന്), in der Nähe von Kozhikode/Calucut (കോഴിക്കോട്),

Kerala, um 1901

[Bildquelle: Fawcett, F.: Nāyars of Malabar. -- Madras : Government Press, 1915. -- (Bulletin / Madras Government Museum ; Vol. III, No.3. -- Pl. XV.]

Abb.: Ayyanar-Tempel (ஐயனார் oder அய்யனார்), Tamil Nadu, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 4. -- Nach S. 192.]

Abb.: Moschee der Māppilla (Moplah) (മാപ്പിള), Kerala, um 1909[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 4. -- Nach S. 472.]

Abb.: Armenische Kirche, Dhaka (ঢাকা), Bangladesh, erbaut 1781

[Bildquelle: noprayer4dying. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/noprayer4dying/2172025331/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01. --Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Siehe:

Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Burial customs (1885). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlasenschaften, 6.). -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen056.htm

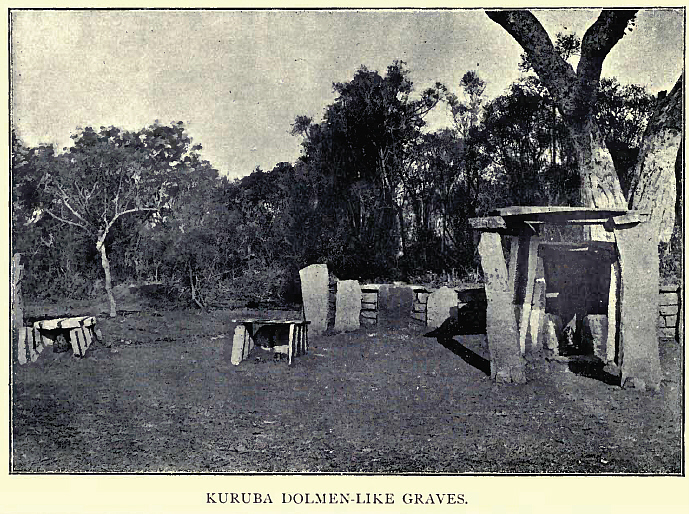

Abb.: Megalith-Gräber der Kuruba, Karnataka, um 1909

[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 4. -- Nach S. 154.]

Abb.: Humayuns ( نصيرالدين همايون) Mausoleum, Delhi, Inneres (erbaut ab 1562 n.

Chr.)

[Bildquelle: Stuck in Customs. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/stuckincustoms/1940187826/. -- Zugriff am

2008-03-31. --

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Abb.: Kenotaphe der Maharawals von Jaisalmer, Bara Bagh bei Jaisalmer

[Bildquelle: El Toñio. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/tonyyoung/371867021/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-31.

--

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Abb.: Stadtmauern, Rajgir (राजगीर) (= Rājagṛha), Bihar

[Bildquelle: Hyougushi. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/hyougushi/36792792/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01.

--

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung)]

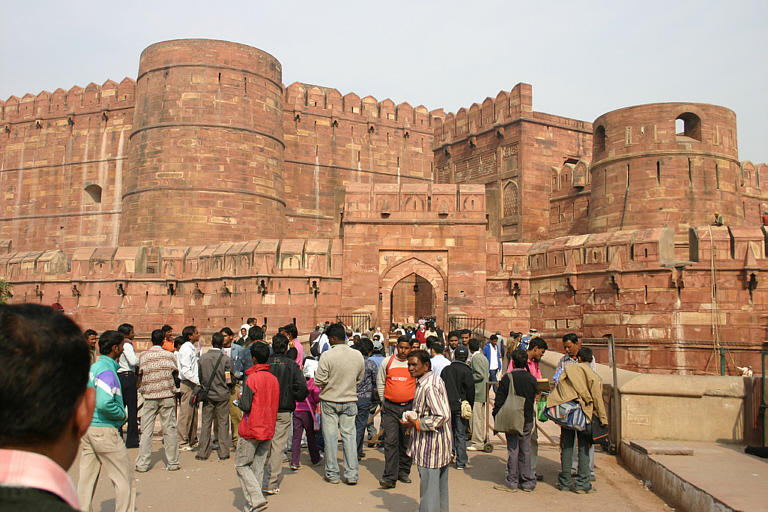

Abb.: Fort, Agra (आगरा), UP, erbaut 1565 - 1573 unter Akbar

[Bildquelle: bodhithaj. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/bodhithaj/372286783/. -- Zugriff am 2008-04-01.

--

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

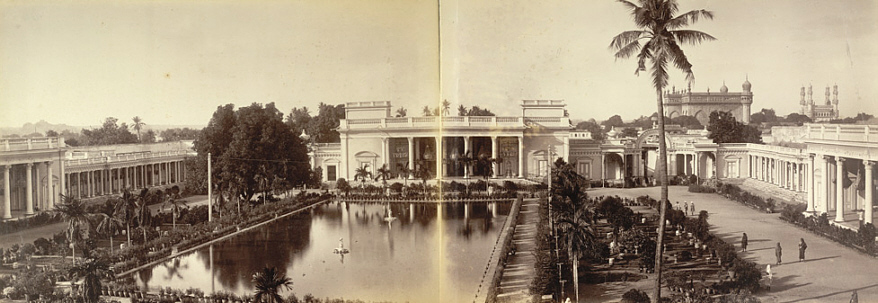

Abb.: Chowmahalla Palace (چَو محلات) des Nizam (نظام الملك) von Hyderabad

(హైదరాబాదు ; حیدر آباد), erbaut 1750 - 1869, Fotografie um 1880

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

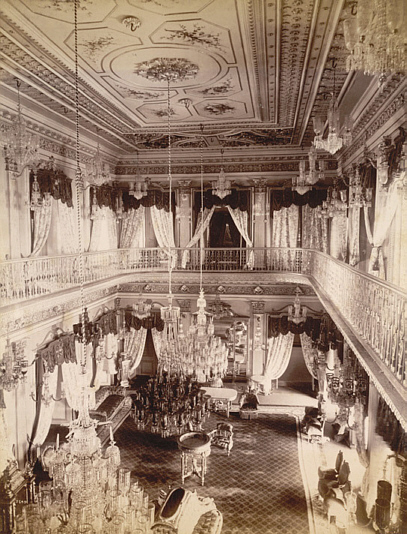

Abb.: Gesellschaftsraum, Chowmahalla Palace (چَو محلات) des Nizam (نظام

الملك) von Hyderabad (హైదరాబాదు ; حیدر آباد), erbaut 1750 - 1869, Fotografie um

1890

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

"GARDENS and Gardeners. Alike amongst Mahomedans and Hindus, the formation of a garden as a place of retreat is a great object of desire. In Wilson's specimens of the Hindu drama, which he translated from the Sanskrit, the Necklace and the Toy Cart contain beautiful allusions to gardens. [...]

And the Mahomedans in India also give them loving names, as Lai Bagh, Farkh Bagh, Roushan [S. 1177] Bagh, Ruby Garden, Garden of Delight, and Ornamental Garden. In this they resemble the Dutch.

Gardeners of British India are all Hindus, and constitute distinct castes. The largest number of them are the Malli, who give their name to the bulk of the gardening tribes. The Koeri gardeners of Hindustan in Behar grow the poppy. The Totakara of the Tamil people and the Teling Totavadu are good gardeners. The Malli are supposed by Mr. Campbell to be a considerable and widespread people. Between Ambala and Dehli are a good many Malli villages, and the race are scattered about the N.W. Provinces as gardeners. They are common about Ajmir, and on the southern frontier of Hindustan. South of Jubbulpur there are many, and are mixed with the Kurmi. All through the Mahratta country they are mixed with the Kunbi ; and most of the potails are either Kunbi or Malli, and extending with the Kurmi far to the east, the Malli into Orissa, and the Kurmi into Manbhum and other districts of Chutia Nagpur.

The formation of a garden with Hindus assumes a religious character, and their Banotsarg ceremony consists in their marrying a newly-planted orchard to the neighbouring well, without which it would be held improper to partake of the fruit.

The British have formed several agri-horticultural societies, each of which has its garden, with economic and ornamental plants. That best known is on the banks of the Hoogly, at Garden Reach, Calcutta, over which Dr. Wallich long presided. The Government garden, Saharunpur, was under the care of Drs. Royle and Jameson. The Madras Agri-Horticultural Garden in 1853 had 996 species of plants. There is one at Dapooli, near Poona. The Government Botanical and Horticultural Gardens at Ootacamund has a valuable collection of plants. The Mysore Government Garden at Bangalore, in the old Lai Bagh, was well known ; and the garden at Peridenia, in Ceylon, under Mr. Thwaites' care, attained great perfection. A botanical garden is kept up at Batavia in Java, at a considerable expense, defrayed by the Netherlands Government. The Indian Government gardens, as also those of the agri-horticultural societies, are for the object of encouraging the cultivation of useful and ornamental plants.

European and native soldiers form kitchen gardens."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 1. -- 1885. -- S. 1177f.]

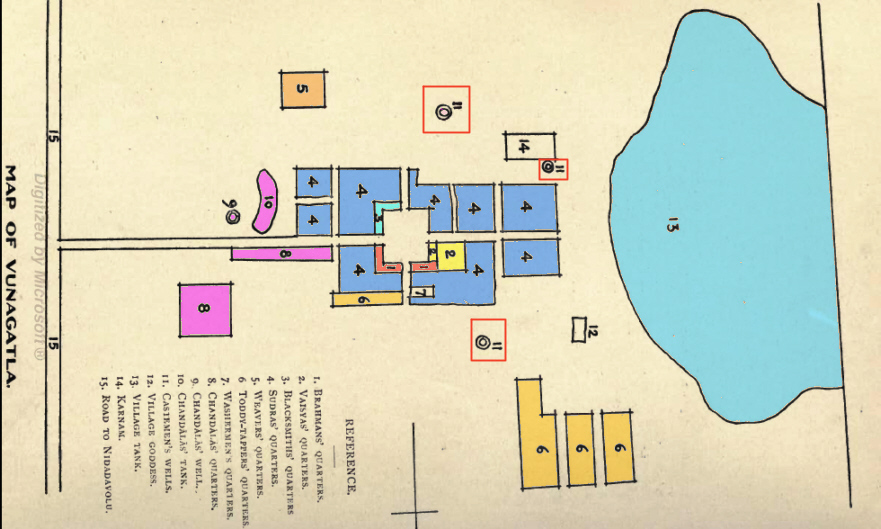

Abb.: Plan des Dorfes Vunagatla, Andhra Pradesh

[Bildquelle: Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- Nach S. 110. -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"]

Eine gute Einführung in eine ökonomische Betrachtungsweise südindischer Dörfer ist:

Slater, Gilbert <1864 - 1938>: Some south Indian villages (1918). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlasenschaften, 4.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-29. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen0534.htm

Lohnenswert ist die Lektüre des ganzen Buchs, dem obiger Text entnommen ist:

Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"

Ein Versuch der Schilderung eines nordindischen Dorfes durch einen Mitarbeiter des Indian Medical Service:

Thomson, S. J. (Samuel John) <1853-1936>: An Indian village. -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlasenschaften, 5.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-29. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen0534.htm

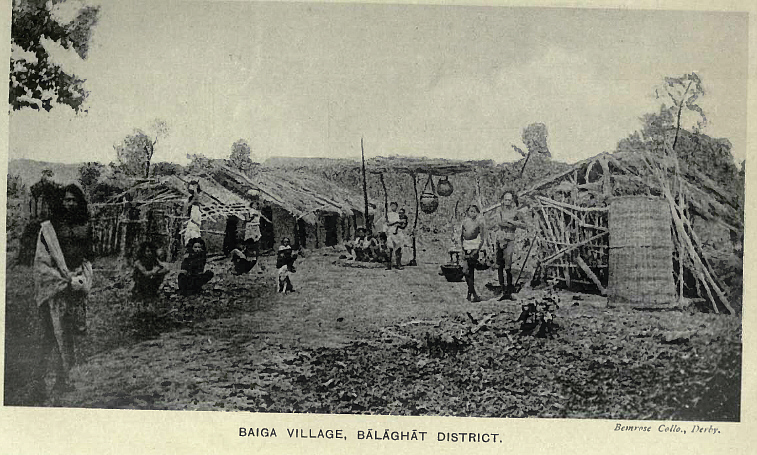

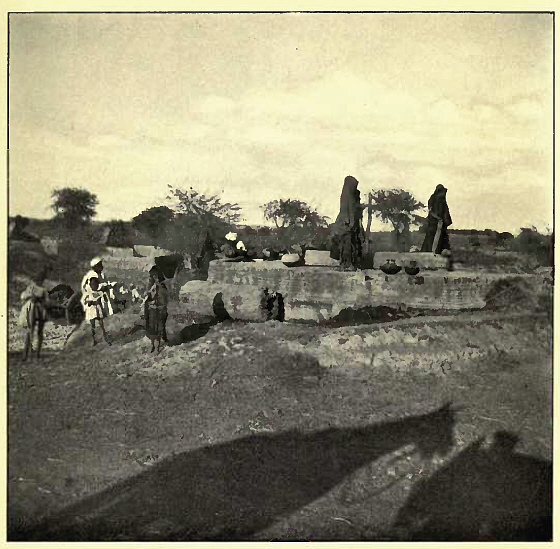

Abb.: Baiga-Dorf, Balaghat-District (बालघाट), Madhya Pradesh, um 1916

[Bildquelle: Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde. -- Bd. 2. -- Nach S. 88]

Siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlassenschaften. -- 1. Zum Beispiel: Taxila (ٹیکسلا, तक्षशिला, Takkasilā). -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen051.htm

Ein anderes Beispiel:

Abb.: Einbandtitel

Härtel, Herbert <1921 - > ; Paech, Hans-Jürgen ; Weber, Rolf: Excavations at Sonkh : 2500 years of a town in Mathura District / Herbert Härtel. With contributions by Hans-Jürgen Paech and Rolf Weber. -- Berlin : Reimer, 1993. -- 478 S. : Ill. -- (Monographien zur indischen Archäologie, Kunst und Philologie ; 9). -- ISBN 3-496-02503-4

Aus dem Vorwort:

"The present report on the excavations at the mound of Sonkh, District Mathura, incorporates a detailed account of the material remains unearthed in eight seasons (1966—74) by a team of German archaeologists sent out by the Museum of Indian Art, Berlin, under the direction of the author. It replaces the more than 20 campaign and preliminary articles in journals published through the years. The main objective of the excavation was to collect material informations on the early history of the once-flourishing State of Mathura, one of the most important cultural centres of ancient India. Explorations led to the decision that a thorough excavation of a less disturbed mound outside of Mathura would be more promising than a place in the city itself. The choice fell on the mound of Sonkh which, in spite of visible damages in the upper part of the citadel elevation, showed signs of presumably intact strata of habitation in its base. These expectations came true. The excavations resulted in a terrace-like exposition of not less than 40 habitation levels covering the span from the 8th century BC up to the 19th century AD. The colonization began in the time of the Painted Grey Ware which in Sonkh, according to radiocarbon dates, lasted from about 800 to 400 BC. The excavated structural remains reach in uninterrupted sequence from the PGW period via the mud wall and mud-brick settlements of the period of the Mauryas and the Śuṅga Cultural Phase up to the beginning of baked brick constructions about the end of the 2nd century BC, i. e. the time of the Mitras of Mathura. On top of the Mitra levels (27-25) followed the remains of the Kṣatrapas (Levels 24-23) and Kuṣāṇas (Levels 22-16). From Level 27 to 16 the unearthed structures represented each time a part of a densely built-up area of habitation. With Level 45 the situation changed considerably. Although the structural remains of Level 15 were, in their layout, clearly connected with those of Level 16, it became evident that now the lowest level of the disturbed part of the citadel was in sight or, seen the other way round, that in Level 16 for the first time a closely built-up area of habitation was found preserved. Consequently, the richer lower levels with all their wealth of remains and finds occupy much more space in this report. Nevertheless, the upper Levels 15 to 1 could, though with difficulties, be assigned to distinct periods, as Gupta and Post-Gupta Levels, Medieval Levels, and Late Fortress Levels.

The results of the work in the just portrayed main excavation area form Part I of this report, consisting firstly of a technical section dealing with the architectural details of the different levels, and secondly, of a descriptive study of the finds. Part II records the surprising discovery of a temple area, situated ca 400 metres north of the main excavation zone, where the foundation walls of an apsidal sanctuary have been excavated, its first phase dating from the beginning of the first century BC, the second one, being erected partly upon the walls of the first, belonged to the early Kuṣāṇa period about two centuries later. This second temple served as a sanctuary for the Naga cult the existence of which was known for Mathura from inscriptions only. Remains of a carved stone railing and of its southern gate, preserving a number of magnificent sculptures, were the most conspicuous finds in the temple area."

[a.a.O., S. 9]

Siehe:

Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Agriculture (1885). -- (Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858 / Alois Payer ; 5. Unbewegliche Hinterlasenschaften, 3.). -- Fassung vom 2008-03-28. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen053.htm

Gute Darstellungen der verschiedenen Landwirtschaft oder Viehzucht betreibenden Kasten und Volksgruppen findet man in:

Russell, R. V. (Robert Vane) <1873-1915> ; Hira Lal, Rai Bahadur <1867-1934>: The tribes and castes of the Central Provinces of India. -- London : Macmillan, 1916. -- 4 Bde.

Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : Ill. ; 24 cm.

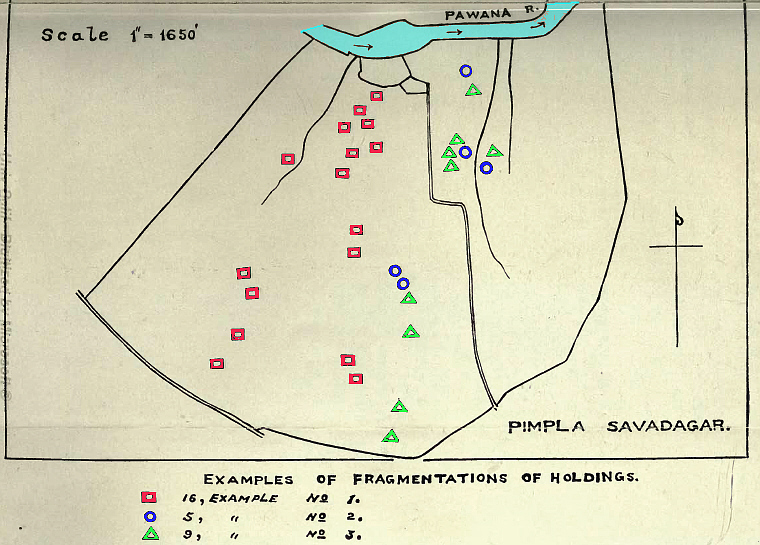

Landzerstückelung kann z.B. eine historische Quelle für Erbteilungen sein.

Abb.: Beispiele für Zerstückelung des Landbesitzes im Dorf Pimpla Soudagar,

nordwestlich von Pune (पुणे), Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: : Mann, Harold H. (Harold Hart) <1872 - > ; Sahasrabuddhe, Dattatraya Lakshman <1881- > ; Kanitkar, Narayan Vinayak <1887 - > ; Tamhane, Vinayak Atmaram <1884 - >: Land and labour in a Deccan village. By Harold H. Mann, in collaboration with D. L. Sahasrabuddhe, N. V. Kanitkar, V. A. Tamhane and others. -- London, Bombay : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1917. -- v, 184 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Pl. VII.]

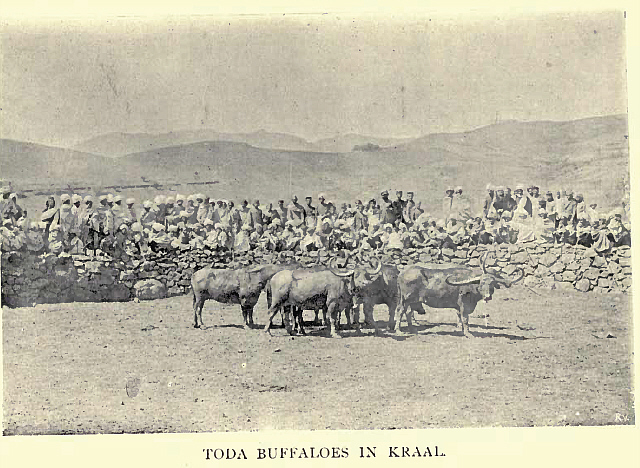

Abb.: Büffel-Kraal, Toda, Nīlgiri (நீலகிர), um 1909

[Bildquelle: Thurston, Edgar <1855 - 1935> ; Rangachari, K.: Castes and tribes of southern India. -- Madras : Govt. Press, 1909. -- 7 Bde. : ill. ; 24 cm. -- Bd. 7. -- Nach S. 116.]

Landwirtschaft setzt meist Landrodung voraus. Deshalb sind Bäume bzw. unbewaldetes Land oft Hinterlassenschaften menschlicher Tätigkeit und damit historische Quellen.

Vgl. folgende Ausführungen über Bäume im Dorf Jategaon Budruk, 25 Meilen nordöstlich von Pune (पुणे), Maharashtra:

"THE TREES OF THE VILLAGE

Bare treeless rocky hills or undulations are the characteristic of all the black cotton soil areas of India, and as a result there is no part of India on the whole more uninviting to the passing stranger. And this village being composed of what is on the whole a poorer soil than is usual in the trap area, is certainly no exception to this general condition, but is rather worse than most of the country in the point of treelessness. Almost the only tree which seems to flourish naturally is the babul (Acacia arabica), and this forms by far the greater part of the tree vegetation of the village.

Abb.: Zweig eines Babul (Acacia nilotica), Haryana

[Bildquelle: J.M. Garg. -- Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]The total number of trees is 1761 or only 0.71 per acre. Of these 1515 are babul trees or 86 per cent of the total. This tree is generally found on the banks of the river or of the nalas. Except in two cases where there are 160 trees and 200 trees respectively in two survey numbers, these babul trees are distributed over all the suitable places in the village. They are all natural, for few people ever plant a babul tree. They may be carefully preserved when they grow, but the seeds either fall directly on the ground and germinate, or else they are carried by goats who eat the green pods of the trees and void the seeds in the dung.

Though there are such a large number of babul trees, only 110 of these are of large size fit for cutting for timber or 7.2 per cent, 639 are of medium size (or 42.1 per cent) while the rest are small and at present useless trees. Small bushes have not been included. The reason why large trees are not more common is that in a treeless country like that round Jategaon the babul is too valuable to be allowed to grow to full size, and before they reach this stage are generally cut to make implements, [S. 53] to repair carts, to make fences, or to serve some other village purpose.

Abb.: Mangobaum in Blüte, Kanpur

[Bildquelle: Amar. -- Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]Next to the babul the most frequent tree is the mango, and of this there are 86 examples in the village, or about 5 per cent of the total number of trees. All are old. There has been no attempt to plant new mango trees for many years. Mango trees are valuable. The fruit is always in demand even when inferior, and a tree is worth at least Rs. 2-8-0 per annum to its owner. When old the wood is valuable, and a good mango tree is worth money at every stage.

Abb.: Neem-Baum (Melia azadirachta)

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia, GNU FDLicense]The only other tree occurring in any numbers is the nim (Melia azadirachta) of which there are 71 specimens or about 4 per cent of the total number. This is again one of the few trees that seem naturally to flourish on trap soils in the Deccan. The remaining species of tree are very few in number, and are shown in the following list:

[S. 54] These trees are almost exclusively on the village site and along the lines of nalas and the pat, with the exception of the bor (Zizyphus jujuba). This last seems to spring up anywhere and is never planted. The other trees are those usually found in the Deccan, and it will be noted that the list is very similar to, though shorter than, that given for Pimpla Soudagar. We are treating the orange orchards separately, but apart from these there are few fruit trees of value. The tamarind and mango are the most important. With the value of the mango we have already dealt. The produce of each tamarind tree will not be overvalued at Rs. 2-0-0 per annum. Thus we get an annual value of Rs. 259 to the village on account of the produce of these two species of tree. The other fruit trees cannot be considered as of any appreciable value. The bor (as it occurs here), the jambul and the kavat are all poor fruit of little importance. Of the good fruits there are none, no figs, no pomegranates, no guavas, no plantains. All the existing trees are old, and (except for the orange gardens to be described later) there has been no energy directed to planting trees, either for fruit or anything else, for many years."

[Quelle: Mann, Harold H. (Harold Hart) <1872 - > ; Kanitkar, Narayan Vinayak <1887 - >: Land and labour in a Deccan village, study no. 2. -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University press, 1921. -- vii, 182 S. : Ill. ; 22 cm. -- S. 52 -54]

Wegen der Reinheitsvorschriften vieler traditioneller Hindus, durften (dürfen) Unberührbare nicht vom selben Brunnen Wasser nehmen wie Angehöriger "reiner" Kasten. Auch aus diesem Grund sind Brunnen auch eine Quelle der Sozialgeschichte.

Abb.: Dorfbrunnen

[Bildquelle: Thomson, S. J. (Samuel John) <1853-1936>: The silent India, being tales and sketches of the masses. -Edinburgh, London : Blackwood, 1913. . -- ix , 365 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Nach S. 92. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/silentindiabeing00thomiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-29. -- "Not in copyright"]

Abb.: Brunnen, Maharashtra

[Bildquelle: Harshad Sharma. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/harshadsharma/40905020/. -- Zugriff am

2008-03-25. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Brunnen, Bangalore

[Bildquelle: Kaiesh. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kaiesh/36199528/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-25. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

"WELL. Drawing water has been the employment [S. 1064] of females throughout the east from a remote antiquity. Some of the wells in India are constructed with much architectural embellishment, of great depth, and of considerable breadth. The more ancient are of a square form, those of recent date are frequently round. They are surrounded for their whole depth with galleries in the rich and massy style of Hindu works, and have often a broad flight of steps which commences at some distance from the well, and passes under part of the galleries down to the water. The deep wells have the descent from the brink by long nights of steps leading far down below the surface of the ground, relieved by landing-places and covered chambers, in which travellers may rest and take refreshment during the heat of the day.

In the alluvial lands of India, and in the beds of rivers, wells are frequently sunk by means of earthenware or iron rings, which are placed one over the other, and the inside earth or sand being scooped out, the rings sink down. These are called pot-wells, and in Bangalore cost about five rupees for a well eighteen feet deep. In Madras town a pot-well can be sunk at the rate of a rupee a foot.

Near Futtehpur, in sinking a well, the people build a hollow masonry tower, of the diameter required, and 20 or 30 feet high from the surface of the ground. This is allowed to stand a year or more till it become firm and compact ; then they gradually undermine and promote its sinking into the sandy soil. When it has sunk to a level with the surface, they raise the wall higher, and go on throwing out the sand and raising the wall they obtain water. Some of the wells of India are of several hundred yards in depth. In the Rajputana desert, water is only come to at depths up to 700 feet. But in the granitic tracts of India, the depth of wells ranges from 12 to 40 feet, according to the swell of the ground.

The importance of wells in an arid tropical country cannot be exaggerated, and the fame which is acquired by sinkers of wells has an illustration in John iv. 6, where the well of Jacob, sunk three thousand years before, was still distinguished. Even yet, among the Hindu people, to sink a well, or form a water reservoir or tank, is deemed an act of merit. In the Panjab, pucka wells are usually worked by the harth or Persian wheel. A broad-edged lantern wheel, whose axis lies horizontally over the centre of the well's mouth, carries, on its broad edge, a long belt of moonj rope made like a rope ladder, the ends of which, joined in an endless band, reach below the surface of the water. To this, at every step of the rope ladder, an earthen pot called tind is fixed. As the wheel revolves, the large rope belt descends into the water with its pots, the pots become filled with water, and are drawn up. As they reach the top of the wheel, they are, by the revolution of the wheel, inverted, and their contents poured out into a trough, which is ready to receive them, and which leads to the watercourse of the fields to be irrigated. Wells are often sunk in the alluvial soils of India as foundations for architectural structures.

In the Persian method of cooling wells, the well is covered in with beams, mats, and earth, and latch is built over it to shield the water from the sun. The well, having been filled during the cold weather, may be opened in May, and the water remains as cool to the taste as ordinary ice water throughout the hot season. The water may be purified by being withdrawn into an earthen reservoir adjoining the well, and allowed to flow back. Ali Kazza Khan, a Kazzilbash, was the first to introduce these wells into the Panjab. Two may be seen at Lahore, one near the Lohari gate, the other in the Sultan Serai. There are also two in the town of Amritsar, and one at Peshawur. The people crowd to those wells during the hot season as to a fair. The ordinary mode of raising water in India is by the hand, but in the south of the Peninsula of India the pe-cottah is used. It is a lever balanced on a pole, from one end of which falls a bamboo with an iron pot, and a man walks from one end of the lever to another to raise and depress the respective ends. Powell, Handbook; Econ. Prod. Panjab, p. 207 ; Heber, ii. p. 357. See Water."

[Quelle: Balfour, Edward <1813-1889>: Cyclopædia of India and of eastern and southern Asia, commercial, industrial and scientific: products of the mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms, useful arts and manufactures / ed. by Edward Balfour. -- 3rd ed. -- London: Quaritch. -- Vol. 3. -- 1885. -- S. 1063f.]

Trockenheit und fehlende Bewässerung sind einer der Gründe für die in Indien bis in die jüngste Zeit häufigen Hungersnöte. Siehe dazu:

In Gegenden Indiens, in denen die Landwirtschaft sehr von künstlicher Bewässerung abhängt (wie z.B. dem Dekkan - दख्खन), kann man drei Arten von Dörfern unterscheiden:

solche mit nur wenig Brunnen und kaum Bewässerungsanlagen

solche mit vielen Brunnen zur Bewässerung

solche mit Bewässerungskanälen

Abb.: Feldbewässerung aus einem Brunnen, um 1913

[Bildquelle: Thomson, S. J. (Samuel John) <1853-1936>: The silent India, being tales and sketches of the masses. -Edinburgh, London : Blackwood, 1913. . -- ix , 365 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Nach S. 22. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/silentindiabeing00thomiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-29. -- "Not in copyright"]

Abb.: Bewässerungskanäle für Reisfelder, Sozhavandhan,Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: yoda02. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/88585285@N00/208639541/. -- Zugriff am

2008-03-25. --

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Persisches Wasserschöpf-Rad, bei Udaipur (उदयपुर), Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: Marc Shandro. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mshandro/34956123/. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-25.

-- Creative Commons Lizenz

![]() (Namensnennung)]

(Namensnennung)]

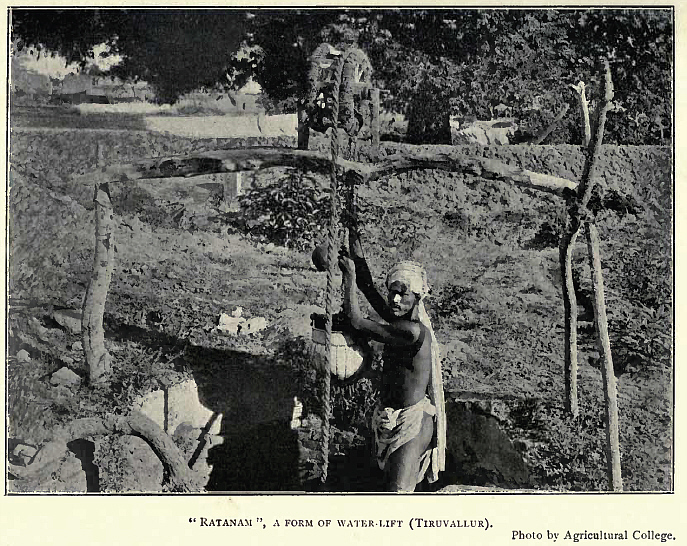

Abb.: Ratanam, Tiruvallur (திருவள்ளூர்), Tamil nadu, um 1918

[Bildquelle: Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- Nach S. 152. -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"]

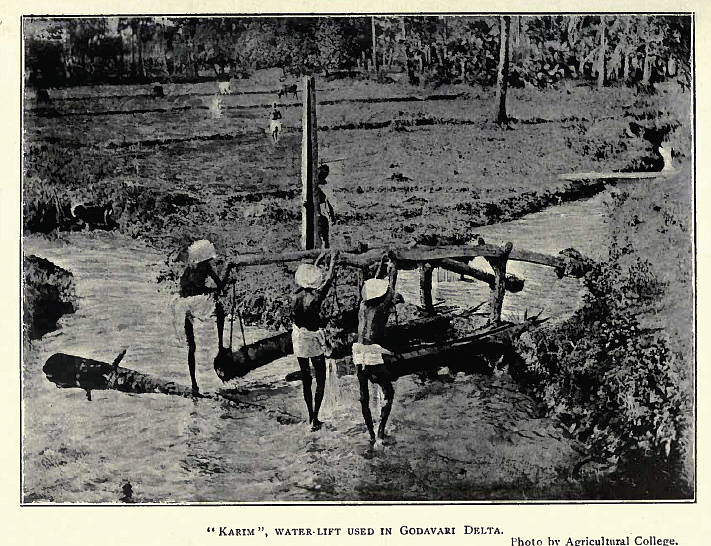

Abb.: Karim-Wasserheber, Godavari (గోదావర) Delta, Andhra Pradesh, um 1918

[Bildquelle: Some south Indian villages / ed. by Gilbert Slater. . -- London [etc.] : H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1918. -- 265 S. : Ill. ; 25 cm. -- (Economic studies ; 1). -- Nach S. 220. -- Online: http://www.openlibrary.org/details/somesouthindianv00slatiala. -- Zugriff am 2008-03-27. -- "Not in copyright"]

Obwohl folgende Ausführungen in Balfours Cyclopaedia teilweise nur für nach 1858 gelten, zeigt der Artikel doch sehr gut, wie viele Probleme (Fragestellungen) mit Bewässerungsanlagen verknüpft sind. Deswegen sind Bewässerungsanlagen unschätzbare Quellen für historische Fragestellungen.

"IRRIGATION. [S. 376] Generous as the Indian soils usually are, and favourable as are the seasons in the plains and valleys of British India, the amount of rainfall, one year with another, varies by fifty percent above and below the average. Rain is frequently absent for many weeks, and without some artificial means of supplying the soil with moisture, no crops could at those periods be taken off the ground. Something can be grown with water, nothing can be obtained without it; and throughout the south and east of Asia the efforts of the rulers and the people have been directed to obtain and hoard the water supply. Of the seven [S. 377] regions into which British India has been divided for hygrometric purposes, two only have their fill of water from natural sources. In the drier regions the rainfall is precarious as well as scanty, and wide expanses of good soil lie permanently untilled and tenantless. A good part of the Panjab and the whole of Sind would be scarcely habitable without irrigation, and in the south-eastern quarter of the Madras Presidency it is indispensable. The natives of these regions have, from unknown times, been forming tanks, digging canals, and leading off channels from rivers, some of them betokening great skill and great labour; and in the 18th and 19th centuries the labours of British engineers, especially of those of the Madras Presidency, have been conspicuously successful in irrigation. Sir Arthur Cotton, in Tanjore, reconstructed and enlarged the ancient irrigation works with such effect, that during the first sixteen years 50,000 acres of land, previously waste, were brought under tillage, the average produce per acre was increased by one-eighth, and the selling value of the land was doubled. In the delta of the Godavery, where Sir Arthur Cotton next went, notwithstanding its rich alluvial soil and fostering climate, alternate flood and drought had brought famines. The territory is now a luxuriant garden, 265,000 acres having been brought under humid cultivation, and the population is prosperous. The Ganges Canal, which diffuses irrigation over an area 320 miles long by 50 broad, is the most magnificent work of its class in the whole world, having a main channel 348 miles long, primary branches of 306 miles, and minor arms of an aggregate length of 3000 miles. In one place this canal is carried over a river 920 feet broad, and thence for nearly three miles along the top of an embankment 30 feet high.

[...]

In India, irrigation is carried on from wells and from tanks, and largely from channels led from its rivers, well irrigation being employed for garden culture, and to supplement the rainfall. The efforts made by several of the races to preserve and utilize the water from the rains and rivers, have been gigantic, as in the Cyclopean Gorbasta structures of Baluchistan, where dams of huge stones have been drawn across the valleys by a race of whose history nothing is known. In India both Hindus and Muhammadans have made great artificial lakes, with dams or bunds, often highly ornamental. One of the most beautiful is that of Kankroli or Rajnagar in the Mewar or Udaipur State. Its retaining wall is about 2 miles long, and the area is about 12 square miles. It is 376 paces in length, is covered by white marble steps, a fairy scene of architectural beauty.

The great tank at Cumbum, in the Ceded Districts, is 8 miles in circumference, and covers an area of nearly 15 squares miles ; that at Ulsoor, near Bangalore in Mysore, is of equal size. The magnificent lake constructed by Mir Alain, near Hyderabad in the Dekhan, as a famine work, has a steamer on it.

Wells or reservoirs, known as the Bai, Baori, or Baoli, have been formed in many parts of India, with flights of steps and a succession of platforms, enclosed by arches, leading down to the water.

Most of the waterworks constructed by the Muhammadans in India were undertaken to obtain water for their parks and palaces. It is to the Hindu races, Aryan and non-Aryan, and in recent times to the British, that India is indebted for the great tanks and irrigation canals which are now to be seen. The smaller tanks in the south of the Peninsula of India, all of Hindu origin, are multitudinous, and some of them are of great size. To Hindus also India is indebted for the great anicuts or dams which head back the waters of the Cauvery and the Colerun.

Some of the great irrigation works, both in Northern and Southern India, have been so constructed as to be available also for navigation. Navigation on the Orissa canals in 1877-78 yielded £ 3384 ; on the Midnapur canal, £ 10,692 ; and on the Sone canals, £ 5965, the aggregate being larger than was derived from irrigation. In Madras, boat tolls in the Godavery delta brought in £ 4496, and in the Kistna delta (Madras canals), £ 1718. The works of the Madras Irrigation Company on the Tumbudra were not made available for navigation until 1879. The canal was projected for irrigation and navigation, which should extend from Sunkesala, 17 miles above Kurnool, to the Kistnapatam estuary on the sea-coast of Nellore, and the Madras Irrigation Company undertook that part of it between Sunkesala and the Pennar river at Sumaiswaram, and subsequently to the town of Cuddapah. It was completed in 1871, but it has been financially a failure, attributable to the heavy charges for maintenance and establishment, to the unprofitable outlay on the navigation works, and the scarcity of labour.

In the Bombay Presidency, near Poona, the British have erected a masonry dam to form Lake Fife, one of the finest reservoirs in the world. The British have drawn one great canal from the Ganges at Hardwar ; they have improved and enlarged an old canal which the Muhammadans brought to Dehli from the Jumna ; a great canal has been led from the river Sutlej, in the Sirhind division of the Panjab, another from the river Ravi north of Lahore, for the Amritsar district ; with many lesser streams for Multan, and for the inundation canals of the Derajats. In Behar a great canal has been taken from the Sone river ; in Orissa the Mahanadi has been dammed farther south, as has also the Krishna river at Bezwara, and the Cauvery and Colerun river near Trichinopoly. But what is there accomplished on a very large scale by the British India Government is, throughout many parts of the country, performed by the villagers themselves. For miles the Hindu cultivator will carry his tiny stream of water along the brow of mountains, round steep declivities, and across yawning gulfs or deep valleys, his primitive aqueducts being formed of stones and clay, the scooped-out trunks of palm trees and hollow bamboos. And sometimes, in order to bring the supply of water to the necessary height, the pe-cottah or the bucket-wheel is employed, worked by men, by oxen, by buffaloes, or by elephants, [S. 378] and in the more level tracts of the south of the Peninsula every little declivity is dammed up to gather the falling rain.

And, independent of the general benefits to the people, great profits have been made by the British Government in several cases, by restoring or repairing tanks and channels which had become ruined, such net profits amounting to from 10 to 45 per cent., and in one instance to 250 per cent. And it is believed that the construction of large storage reservoirs would return a high percentage on the outlay. The smaller tanks constructed by the people themselves well repay the labour employed, though to the Government the construction of flat country tanks of the second class, or even of the third class, offer a very doubtful return.

The value of water to the cultivator is shown, first, by contrasting the yield of dry crops with that of rice and sugar-cane, from actual experiments. From these it appeared that the net profit per acre on dry crops was 8s. 2½d. ; on rice, £4, 16s. 10d. ; and on sugar-cane, £18, 6s. 6d. In the two last cases a very low rate for the water was assumed, viz. 12s. per acre for each crop of rice, and 24s. per acre for each crop of sugar-cane, as provisionally fixed by Government. A comparison was made between dry crops and rice, and dry crops occasionally flooded, based on the average price of grain extending over five years, and deducting one-fourth from the gross value of the crop in the case of dry crops, and one-sixth in the case of wet crops, to cover loss in bad years. Without deducting the water rate, the difference in the net value of the crops was as follows : Between dry crops and rice, taking the most unfavourable comparison, 25s. 7d. ; between dry crops and the same occasionally irrigated, 80s. 8d. ; and between two dry crops and sugar-cane (which occupied ten months of the year), £8, 2s. 8d. But if water be stored, so as to allow a second crop of rice to be grown, the advantages are nearly doubled. Provided a water rate proportioned to the value of the water were fixed, irrigation would benefit the cultivator to the extent of 8s. 6d., or 50 per cent., and yield a gross return on the outlay of 14s. 9d. per acre ; and if water were stored for a second crop, the gain to the cultivator would be 19s. 9d., or more than 100 per cent., and the return to the agency supplying the water 37s. 3d. per acre, the cultivator not having to expend any capital in improvements. Of the 37s. 3d. per acre profit, 22s. 6d. was about the sum due to the storage of water, supposing such storage works to be added to distribution works already constructed. The cost of large works of irrigation might be safely reckoned at £7 per acre on an average, or £8, 15s. if 5 per cent, on one-half the capital for ten years during construction were added. If the profits made by the application of the water were divided in the proportion of one-third to the cultivator and two-thirds to the agency supplying the water, works of channel irrigation would benefit the cultivator, as above stated, to the extent of 50 per cent., and yield a net return of 7.4 per cent, on the capital expended. It appears probable that, in the most favourable localities, 7000 cubic yards of water could be stored for £1, and in others 4250 cubic yards.

[...]

Only rivers of the larger class, which have a continuous flow for several months, are available for extensive irrigation projects. The smaller rivers are merely torrents, which quickly carry off heavy falls of rain, and then become dry again. The water, however, is in many cases intercepted by chains of tanks, of the second or third class, built across these torrents. The deltas of large rivers, being the most easily irrigated lands, have been so treated for ages, and the works have been much extended and improved under the British Government, by the construction of permanent weirs of great lengths at the heads of the deltas, such weirs being built on the sandy beds of wide rivers subject to heavy floods. This seemed to have been beyond the skill of the ancient native rulers. They, however, built many weirs on the large rivers in the middle part of their courses, the situations being skilfully chosen, but the construction was rude and imperfect. They were generally built on a reef of rocks, with loose rubble, faced with large blocks of granite laid dry, and sometimes fastened with iron clamps. The modern weirs in similar situations are of masonry, with a vertical or slightly battering face on the down-stream side, and with heavy copings. In rivers having sandy beds, it is usual to build the body of the weir on a foundation of brick wells, sunk to the low-water level, and filled with concrete. On the lower side there is an apron, having a slope of 1 in 12 from the crest, with a toe wall ; and if the slope be long, intermediate walls are also built on wells, and below all there is a broad layer of rough rubble of large dimensions.

The ancient irrigation channels were generally defective in design, being too small, and having much too great a fall. In consequence of these channels being so near the river, they irrigated only a narrow strip of land ; and the current being too great, excessive annual repairs were required. This system necessitated numerous off-takes from the river, involving the expense of many weirs, and a great aggregate length of unproductive channel, from the off-take to the point where the channel reached such a level as to command the surface of the country. On the other hand, a canal of large dimensions, taken off from one head, having a slower current and less fall, would soon so gain on the level of the river that it would reach districts remote from it, and [S. 378] consequently more in need of artificial supplies of water ; and it would also command a much larger extent of country than it could supply entirely with water. This was an advantage, because it would be many years before a district could be completely changed from dry to wet cultivation, as it would require to have its population trebled. It also afforded means of assisting dry crops in years of drought, and thus preventing famine. In many districts complete failure of the crops now grown occurred every few years, and a good crop was a rare occurrence. There should therefore be facilities for completely irrigating detached areas at considerable intervals, and of giving occasional irrigation to dry crops.

Distribution was effected from the second class of tanks directly, by means of sluices in the bund. From the third, and more especially from the first class, it was commonly effected indirectly ; thus the natural channel of the river or rivers, which had been dammed to form the tank, were used to carry part of the water for irrigation, weirs being built across them at suitable places, and artificial channels taken off from above them. By these means the surplus of the water, which was generally wastefully used by the ryots, was saved, being collected by drainage into the stream, and redistributed at the next weir. Distribution was most economically effected from a canal, when the latter ran along a ridge; but as this could rarely be accomplished in the case of a canal taken off from a main drainage, it was next best effected by leading the main distribution channels down the ridges crossed by the canal. Distribution could be carried out in the Ceded Districts for 5s. per acre, including sluices in the main canal, and all necessary road and water crossings, but excluding the coast of terracing the land to prepare it for wet cultivation, this being done by the occupier. The nature of the ground was occasionally such that the drainage was effected naturally, no works being required for that purpose beyond small open trenches in the rice fields.

Ordinary agricultural works in the Madras Presidency irrigate an area of about 3,365,157 acres, yielding a revenue of approximately Rs. 1,31,04,126. They consist of two kinds, viz.

rain-fed tanks or reservoirs, generally of minor individual importance, each deriving its supply directly from rainfall distributed over an area of land, which is called the catchment basin ; and

channels from rivers and streams providing direct irrigation, or supplying tanks, together with the tanks supplied.

In the first case, the rainfall is caught and retained before it reaches natural lines of any importance. In the last, it is diverted from the drainage lines while pursuing its course, and led away by artificial means. In connection with these last are the anicuts or weirs which have been constructed by former governments and under British rule. About 1876, there were in the Madras Presidency 1212 weirs across rivers or streams, 769 of which were in the three districts of Madura, Salem, and S. Arcot. There were 33,318 tanks and irrigation canals, of which the districts of Coimbatore, Vizagapatam, Kistna, Kurnool, and Nellore had only 2590. The irrigated area from all these was approximately 3,365,157 acres, and the revenue Rs. 1,31,04,126. Besides these, there were irrigation works belonging to landlords, also others belonging to the Government irrigation systems, for which capital and revenue accounts are kept. Of these last, the principal are the anicute or weire across the rivers Godavery, Kistna, Pennar, Cauvery, Vellar, Palar, and Tambrapurni, and the great reservoir of Chembrumbakam.