|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Zitierweise | cite as: Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 14. kṣatriyavargaḥ (Über Kṣatriyas). -- 2. Zweiter Abschnitt (Über Kriegsführung). -- 6. Vers 50c - 61 (Waffen). -- Fassung vom 2011-06-16. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa6/amara2142f.htm

Erstmals hier publiziert: 2011-06-16

Überarbeitungen:

©opyright: Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

|

Meinem Lehrer und Freund Prof. Dr. Heinrich von Stietencron ist die gesamte Amarakośa-Übersetzung in Dankbarkeit gewidmet. |

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Die Devanāgarī-Zeichen sind in Unicode kodiert. Sie benötigen also eine Unicode-Devanāgarī-Schrift.

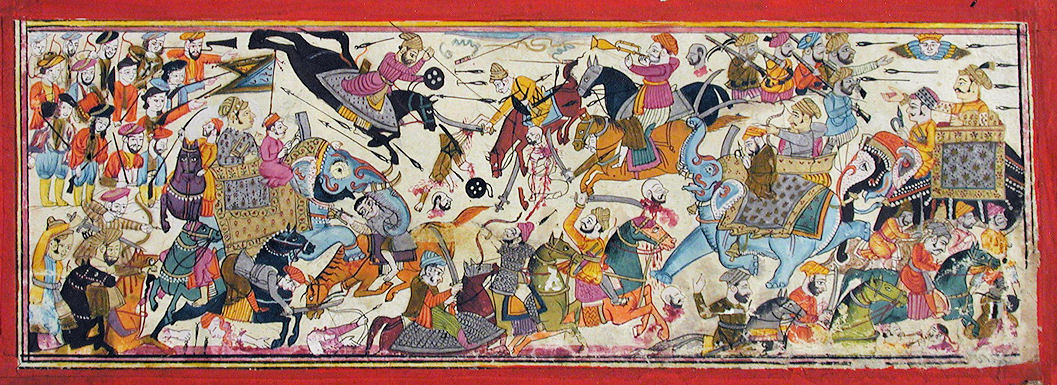

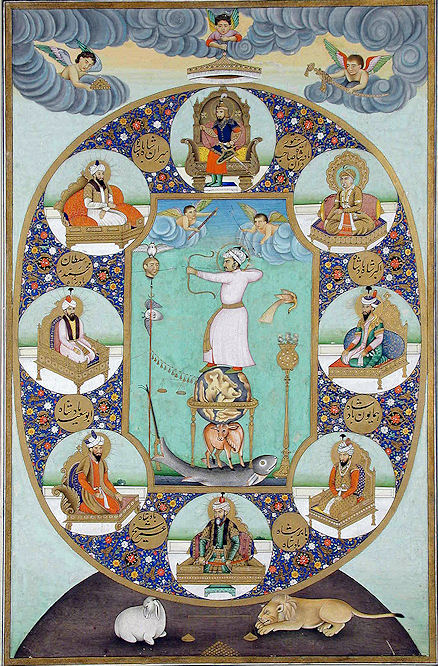

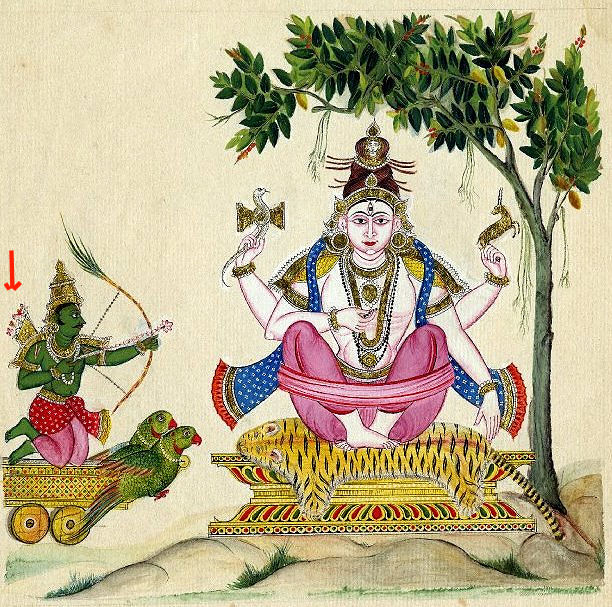

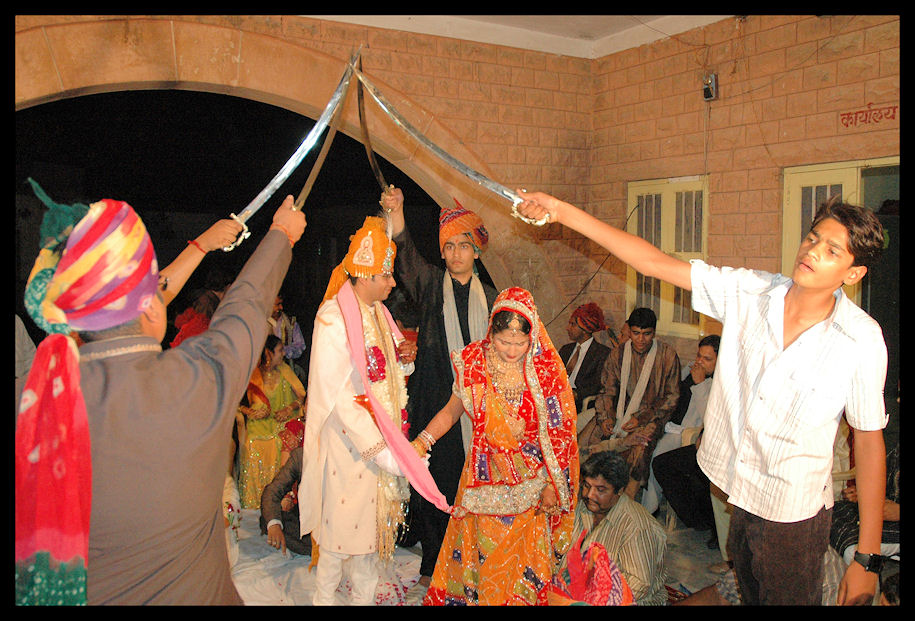

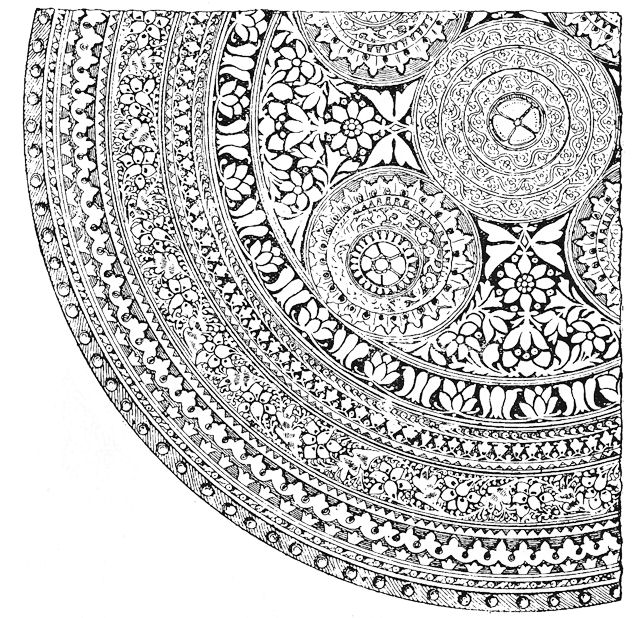

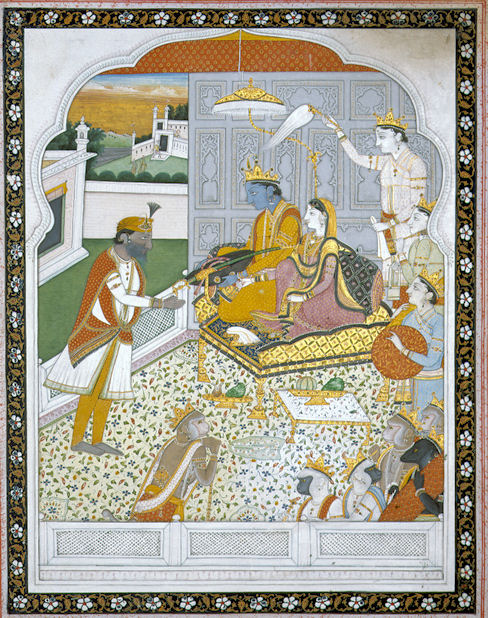

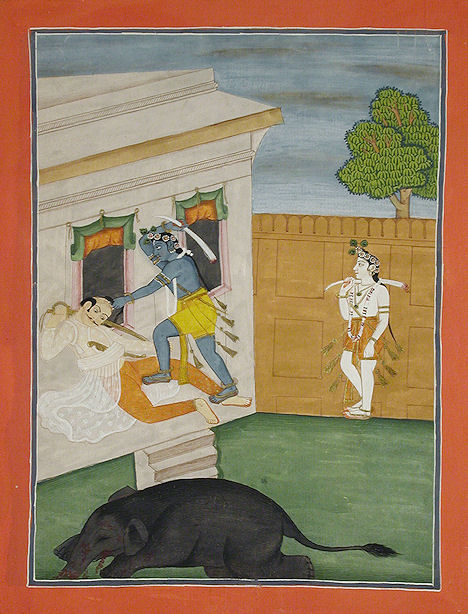

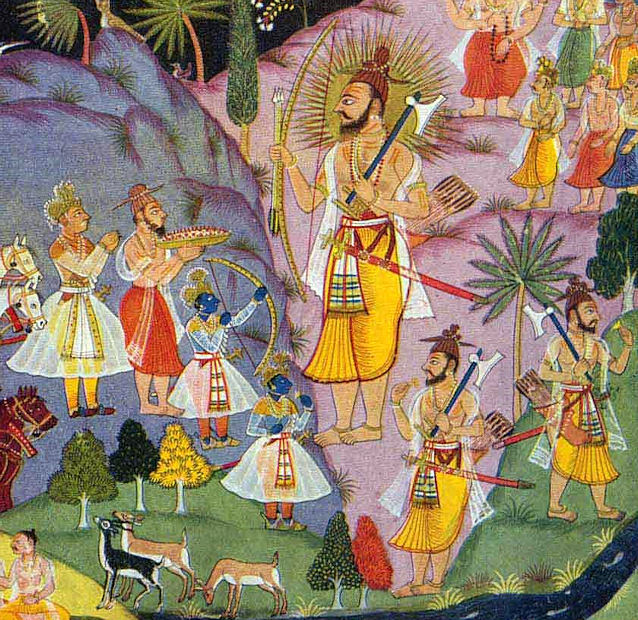

Abb.: Kampfszene, Bhāgavata-Purāṇa-Handschrift, Uttar Pradesh,

ca. 1780

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4838434662/. -- Zugriff am

2011-04-10. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

|

50c./d. āyudhaṃ tu praharaṇaṃ śastram astram athāstriyau आयुधं तु प्रहरणं शस्त्रम् अस्त्रम् अथास्त्रियौ ॥५० ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Waffe:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A weapon. Some restrict the last term to a missile weapon ; and the preceding term to a weapon retained in the hand."

आयुध - āyudha n.: Kampfgerät, Waffe

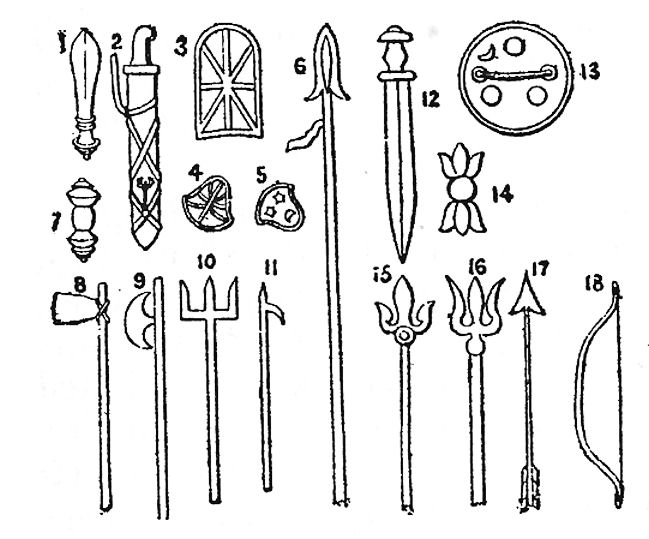

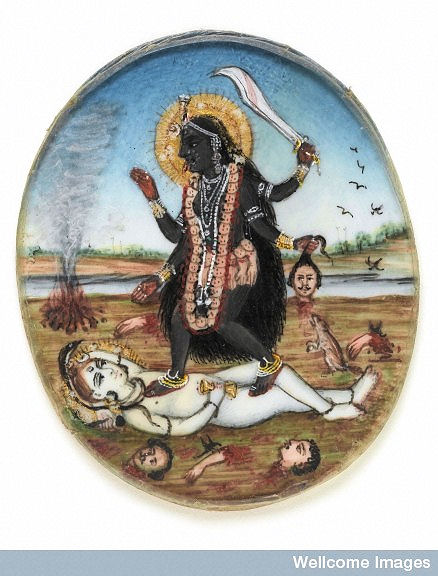

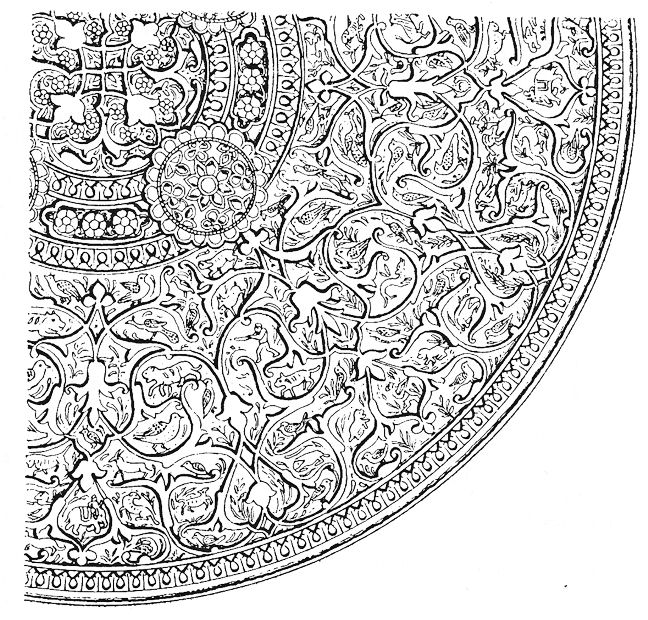

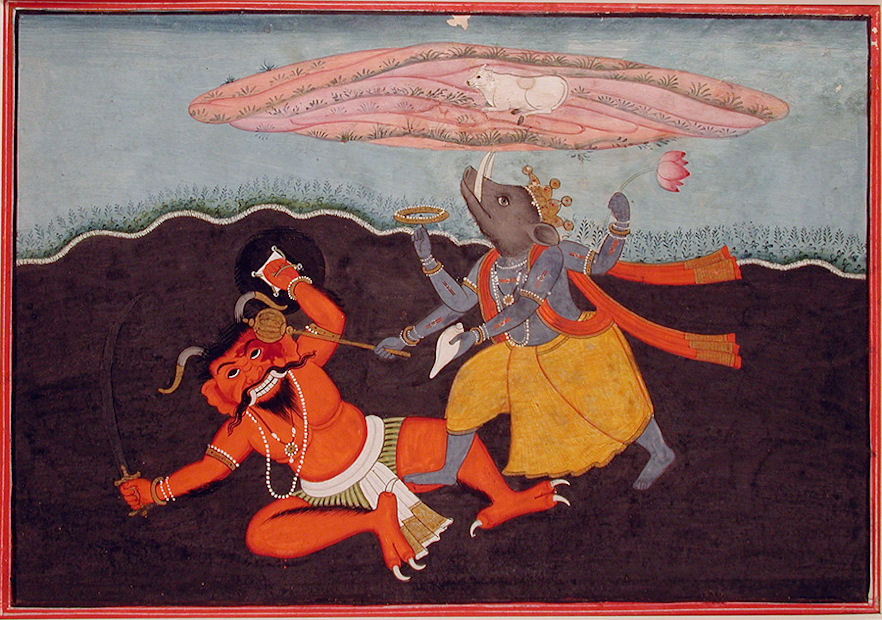

Abb.: आयुधानि । Varāhī mit den Waffen verschiedener Götter, Himachal Pradesh, 1660/70

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4838446338/. -- Zugriff am

2011-04-14. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

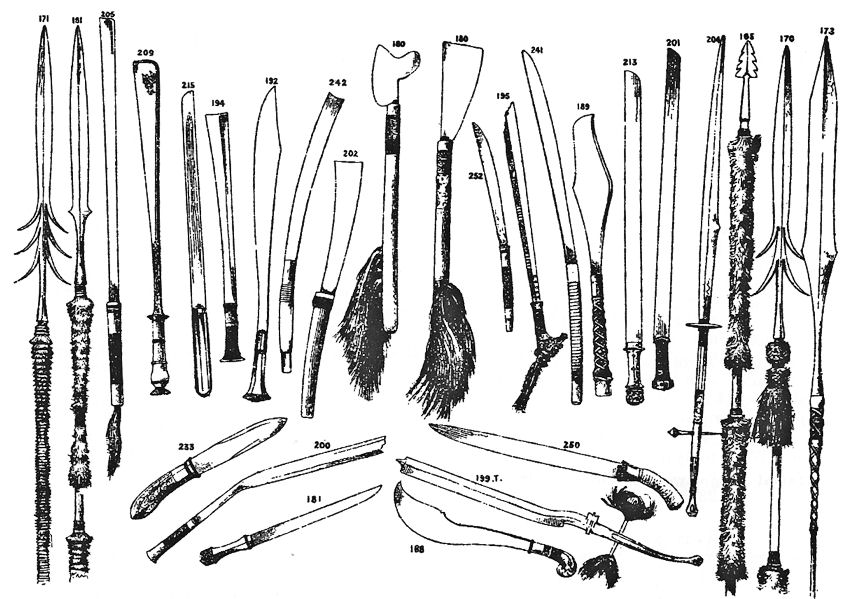

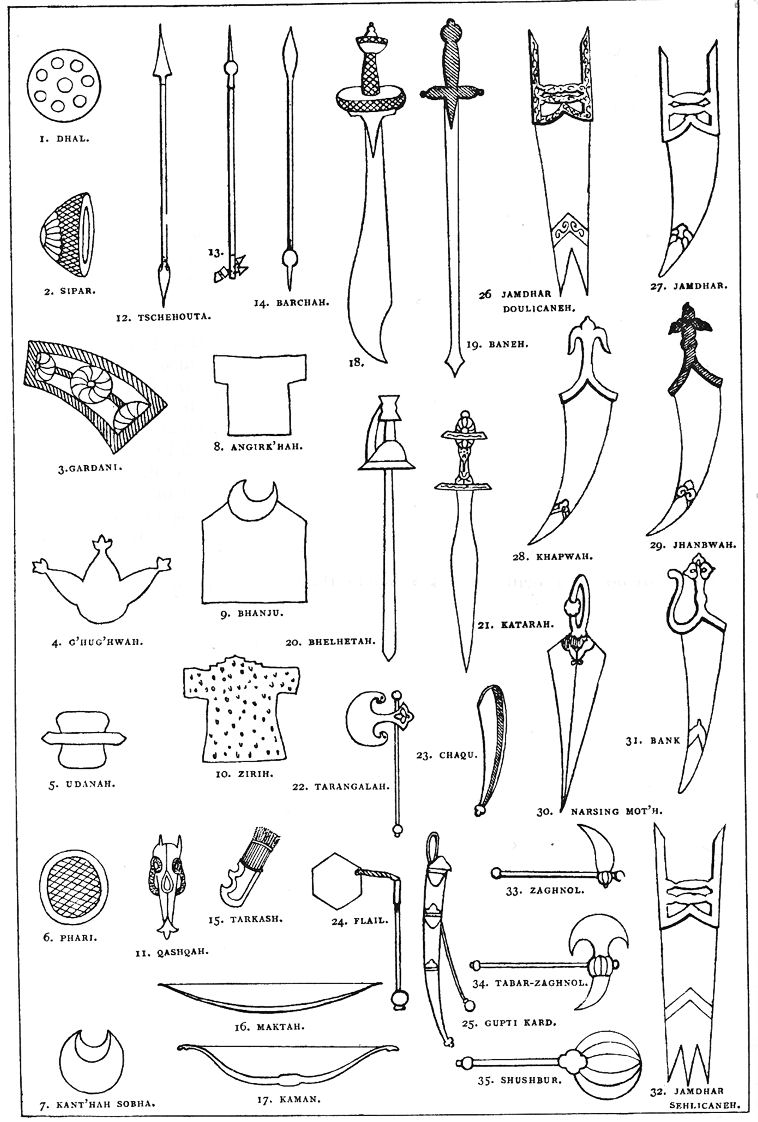

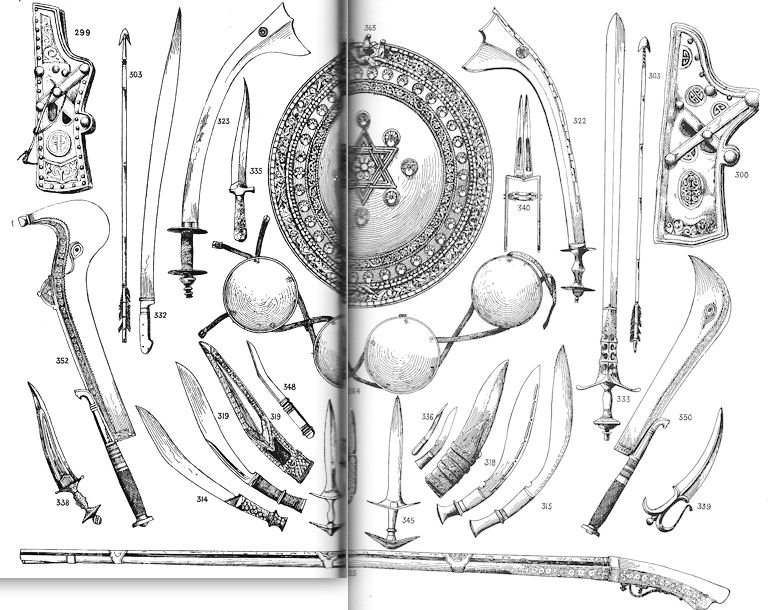

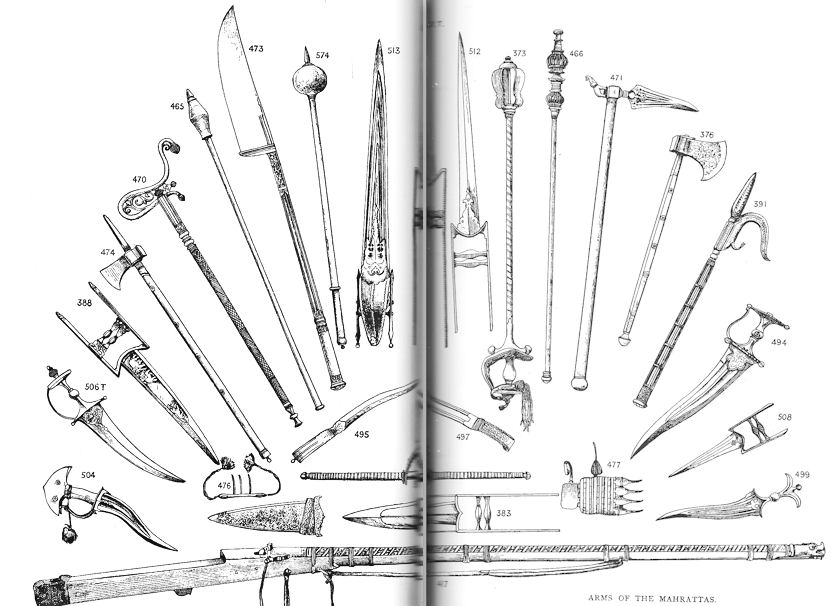

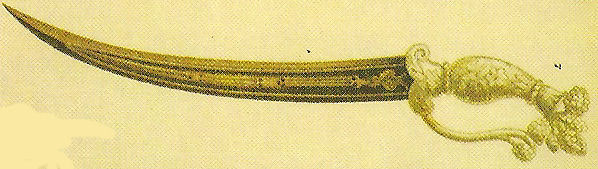

Abb.:

Abb.:

Abb.:

Abb.:

Abb.:

प्रहरण - praharaṇa n.: Angriff, Waffe

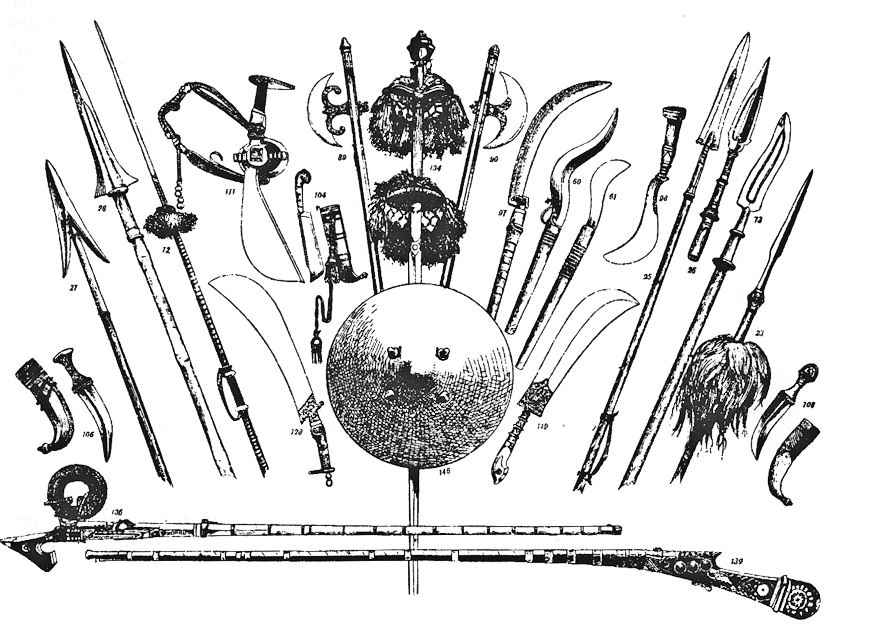

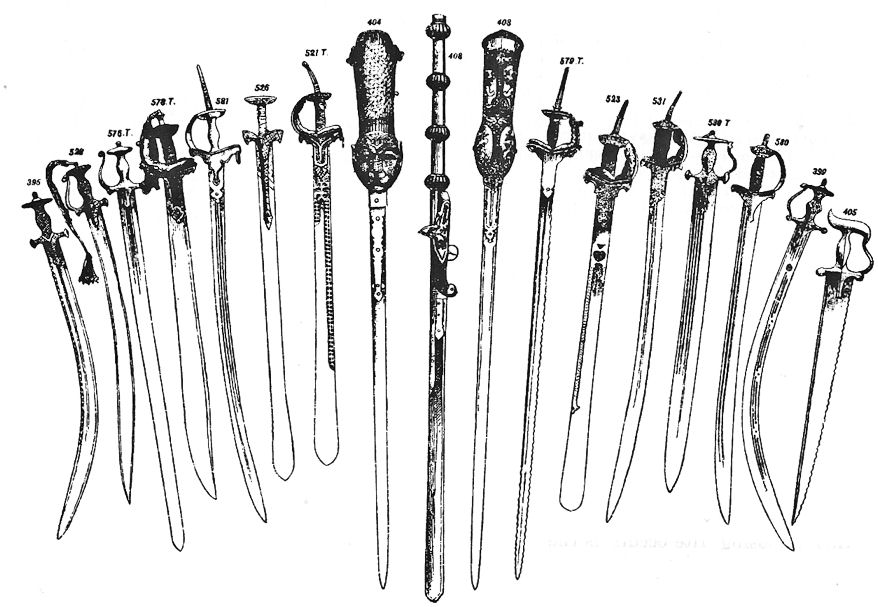

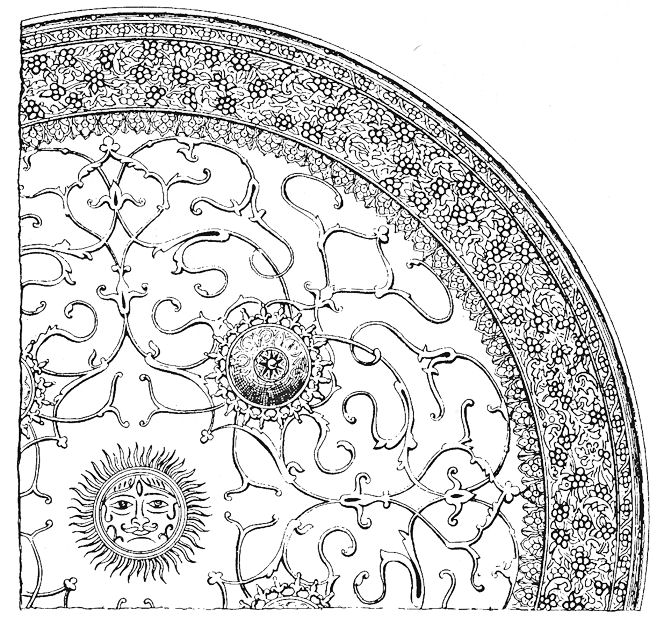

Abb.: प्रहरणानि । Waffen und Rüstungen aus der Zeit Akbars

Abb.:

Abb.:

Abb.:

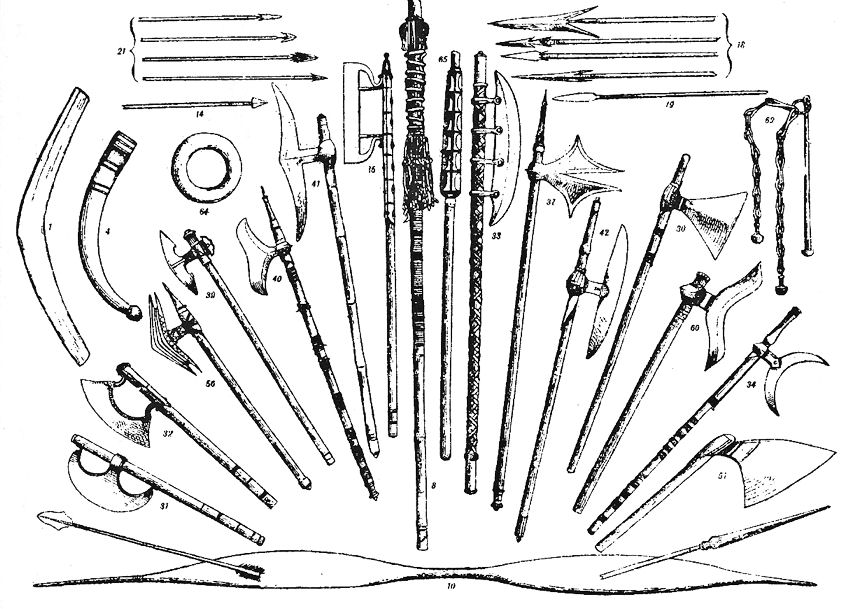

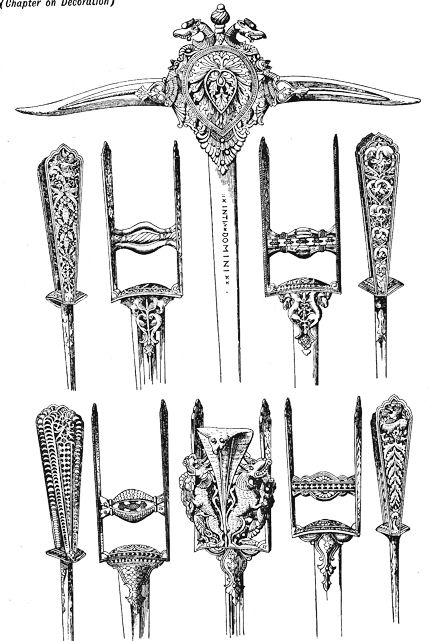

"Achtzehntes Kapitel (36. Gegenstand). Der Aufseher der Waffenkammer.

Der Aufseher der Waffenkammer (āyudhāgārādhyakṣa) soll die für den Kampf, das Verteidigungswerk der eigenen Burgen und den Angriff auf die festen Städte des Feindes nötigen Rädermaschinen, Waffen, Schutzmittel (āvaraṇa) und das Zubehör durch Grob- und Kunsthandwerker des betreffenden Faches anfertigen lassen, denen Umfang der Arbeit, Zeit und Lohn festgesetzt ist, sowie auch wie ihr Erzeugnis ausfallen muss.1

Und er soll sie (diese Erzeugnisse) an den für sie geeigneten Orten unterbringen.2 Er soll dafür sorgen, dass oft ihr Aufbewahrungsort geändert und ihnen Sonne und Lüftung gegeben wird.3 Was von Hitze, eindringender Feuchtigkeit oder Insekten und Würmern beschädigt wird, soll er anders unterbringen. Er soll Kenntnis von ihnen haben nach ihrer Gattung und ihrem Aussehen, ihren bezeichnenden Merkmalen und ihrer Menge, ihrer Herkunft, ihren Preisen und ihrer Aufbewahrungsstelle.

Sarvatobhadra (»Allglücklich, Allherrlich«),4 jāmadagnya,5 bahumukha (»Vielmund, Vielspeier«),6 viśvāsaghātin (»Töter der Ahnungslosen«),7 samghātī (»Zusammensetzung«),8 yānaka (»Wägelchen«),9 parjanyaka (»Regengöttchen, Regelchen«),10 bāhu (»Arm«),11 ūrdhvabāhu (»aufgereckter Arm«)12 und ardhabāhu (»Halbarm«)13 – dies sind die aufgestellten Kriegsgeräte.

Pañcālikā (»die Pañcalerin«),14 devadaṇḍa (»Götterknittel, Götterstrafe«),15 sūkarikā (»Mutterschweinchen«),16 musalayaṣṭi (»Mörserkolbenstange, Keulenstange«),17 hastivāraka (»Elefantenwehrer«),18 tālavṛnta (»Fächer«),19 mudgara (»Hammer«), gadā (»Keule«) spṛktalā (»Fühldiefläche«?),20 kuddāla (»Spaten«), āsphāṭima (etwa »Anklatsch«),21 udghāṭima (»Emporriss«),22 śataghnī (»Hunderttöterin«),23 triśūla (»Dreizack«) und cakra (Wurfscheibe) sind die beweglichen Kriegsgeräte.

Śakti (Lanze),24 prāsa (Wurfspeer),25 kunta (Holzspeer),26 hātaka,27 bhindipāla (Art Speer),28 śūla (Spieß),29 tomara (Wurfspieß),30 varahākarṇaA1 (»Eberohr«),31 kaṇaya,32 karpaṇa,33 und trāsikā (»Erschreckerin«)34 – das sind die Waffen mit messerartiger Spitze (hulamukha).35

Aus Weinpalmenholz, aus »Bogenrohr« (cāpa oder cāpaveṇu), aus Hartholz und aus Horn gemacht, sind die Bogen und heißen dann (nach der Reihenfolge des Materials) kārmuka, kodaṇḍa, druṇa und dhanus.36

Die Bogenschnüre sind aus mūrvā-Hanf (Sanseviera Roxburghiana), den Fasern des arka (Calotropis gigantea), Hanf, gavedhu (Coix barbata),37 Bambusrindenfasern und Tiersehnen.

Bambus (veṇu), śara (Art Rohr, Saccharum Sara, von dem der gewöhnlichste Name des Pfeiles stammt), śalākā (»Splitter, spitzes Holz«), daṇḍāsana (»Stab-Wurfgeschoß«) und nārāca (ganz aus Eisen wie die Kommentatoren gewöhnlich sagen) – das sind die Pfeile.

Ihre Spitzen sind da zum Durchschneiden, Durchreißen, Durchbohren und aus Eisen, Knochen oder Holz gemacht.

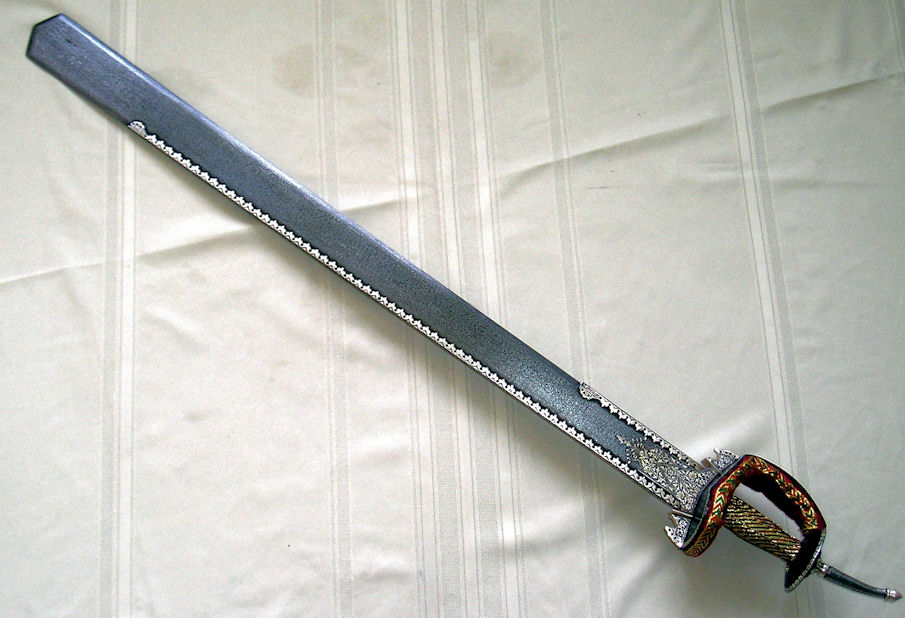

Nisṭṛṃśa (»Erbarmungslos«, nach dem Komm. Schwert mit krummer oder geschwungener Schneide), maṇḍalāgra (»Rundschneide«, also Krummsäbel) und Langschwert38 – das die Schwerter.

Die Schwertgriffe sind gemacht aus dem Horn des Rhinozeros oder dem des Büffels, aus dem Zahn des Elefanten, aus Holz und aus der Wurzel des Bambus.

Beil, Axt, paṭṭiśa, Schaufel, Spaten, Säge und kāṇḍacchedana39 sind rasiermesserartige Werkzeuge.

Mit einer Maschine, mit einer Schleuderstange40 und mit der Hand geschleuderte Steine und Mühlsteine sind (ebenfalls) Waffen.

Eisennetz (lohojāla), Eisennetzchen (lohajālikā), Eisenplattenkleid (lohapaṭṭa), Eisenpanzer, (lohakavaca), Fadenharnisch und Gefüge aus Haut, Huf und Horn von Delphinus gangeticus, Rhinozeros, dhenuka (nach Sham. Büffel, nach Gaṇ. Gayal), Elefant und Rind sind Schutzbekleidungen (vārmāṇi), (ebenso) Helm, Halsberge, Kürass (kūrpāsa), Panzerhemd, »Pfeilabwehrer« (vārabāṇa, »geht bis auf die Knöchel«), Panzerweste und Fingerhandschuhe.41

Schilde sind: Korbgeflecht (peṭī) Lederschild, »Elefantenohr (wegen seiner Form)«, tālamūla),42 »Blasebalg« (dhamanikā), »Torflügel« (kavāṭa), kiṭikā (Leichtschild, »Art Schild aus Rohr und Leder«), der »Unwiderstehliche« und der »Wolkenrandige«.43

Kriegszubehör (upakaraṇāni) sind auch: Gerät, das dazu dient, Elefanten, Schlachtwagen und Pferde zu schirren, sowie Sachen, die zu deren Schmuck, und solche, die zur Herrichtung ihrer Ausrüstung für die Schlacht dienen.

(Dazu komen:) Mittel, den Feind durch Gaukeltrug zu täuschen und ihn mit Geheimmitteln zu verderben,44 sowie die Arbeit der Fabriken.

Der Waffenherr (d.h. der Zeughausaufseher) muss auch Kenntnis haben von dem, was gewünscht wird, vom Ausfall der Unternehmungen,45 vom Gebrauch (der Kampfwerkzeuge), von Trug und Stempelwesen,46 sowie von Verlust und Verbrauch der Rohmaterialien.

Fußnoten

1 Vgl. 112, 16 f.; 114, 7, sowie karmaphala »Ergebnis der Arbeit« 115, 17.

2 Svabhūmi der eigene Ort, der für einen günstige Ort, bes. das günstige Gelände im Krieg ist bei Kauṭ. sehr häufig. Siehe z.B. 355, 6; 364, 1 ff.; 367, 3, 11, 19; 388, 15.

3 Parivartayati wird auch vom Untersuchen (»Umwenden«) gebraucht (41, 18), an jener Stelle aber von Kleidern und Schmucksachen. Ob nun sthānaparivartana auch »Untersuchung ihres Aufbewahrungsortes« heißen kann, was hier gut passen würde, weiß ich nicht. Gaṇ. und Jolly haben nach ātapa noch pravāta »Lüftung«.

4 »Hat die Größe eines Karrenrads ... Wirft, wenn umhergewirbelt, Steine nach allen Richtungen«. So Bhaṭṭ., von dem auch die Erklärungen der folgenden Kriegswerkzeuge stammen.

5 Jamadagni ist ein wegen seiner Bogenkunst und Kenntnis aller Waffen bekannter Heiliger der Vorzeit (ṛṣi), Vgl. Weib im altind. Epos 265; MBh. III, 114, 45. Es wäre also wohl die von Jamadagni stammende Waffe »eine große Pfeilschleudermaschine, die man an die Öffnungen der oberen Stockwerke stellt.«

6 »Ist ein Turm, der oben auf die Stadtmauer gestellt wird, mit Leder geschützt ist, drei oder vier Stockwerke hat und Standorte für Bogenschützen. Bogenbewehrte Männer stehen dort und schießen Pfeile nach allen Richtungen.« Bhaṭṭ. Nach ihm auch die folgenden Erklärungen.

7 »Ein wagerechter Balken (parigha), draußen vor der Stadtmauer, der durch eine mechanische Vorrichtung losgelassen wird und tötet.«

8 »Eine Zusammensetzung aus langen Hölzern, eine Feuermaschine, zu dem Zweck, Türme usw. beim Feinde anzuzünden«.

9 Oder yānika. Vielleicht ist saṃghātī- (bei Gaṇ. und Jolly saṃghāṭi-) yānaka ein Wort, so dass also diese Feuermaschine auf Rädern fortzubewegen wäre.

10 »Eine Wassermaschine, Feuer auszulöschen. Andere aber: eine 50 hasta lange Vorrichtung, die über die Stadtmauer hinausgestreckt ist und, wenn sie mittels einer Maschinerie losgelassen wird, tötet, was in der Nähe ist«.

11 »Zwei Pfosten, halb so groß wie der parjanyaka, einander gegenüberstehend; töten, durch eine mechanische Vorrichtung losgelassen.«

12 »Ein aufrecht stehender Pfosten von der Größe des parjanyaka; tötet, mittels einer Maschine losgelassen, alles was in seiner Nähe ist.« – Der »Halbarm« ist dann nur halb so lang.

13 »Ein aufrecht stehender Pfosten von der Größe des parjanyaka; tötet, mittels einer Maschine losgelassen, alles was in seiner Nähe ist.« – Der »Halbarm« ist dann nur halb so lang.

14 Die Pañcāla waren ein Kriegervolk im nördlichen Indien. Diese Waffe scheint von ihnen gekommen zu sein. Nach Bhaṭṭ. ein mit Spikernägeln besetztes Brett, das draußen vor der Stadtmauer ins Wasser gelegt wird, den Feind aufzuhalten.

15 »Ein großer Pfosten, der mit Keilen befestigt ist. Wird oben auf die Mauer gestellt« (und jedenfalls auf den Feind hinabgestürzt).

16 »Ein großer Sack, der aus genähtem Leder gemacht und innen mit Baumwolle, Wolle usw. angefüllt ist. Dient dazu, die Torbauten (gopura), die Türme, den, ›Götterweg‹ (devapatha) usw. zu decken und von außen kommende Steine abzuwehren«. Andere sagen, er sei aus Rohr gemacht und mit Leder überzogen, habe die Gestalt eines Schweins und sei dazu da, zu verhindern, dass der Feind an der Mauer einen Halt bekomme (oder: die Mauer einnehmen könne).

17 »Ein Spieß aus Khadiraholz.« Dies Holz ist sehr hart.

18 »Eine große Stange mit zwei oder drei Spitzen.«

19 »Eine fächerähnliche Scheibe.« Gaṇ. hat noch drughaṇa »Holzkeule«. Er sagt, der drughaṇa sei hammerförmig.

20 »Eine Stange, die mit Stacheln besetzt ist«.

21 Dasselbe wäre āsphālima. Bhaṭṭ. und Gaṇ. lesen āsphoṭima, Vgl. das im Epos häufige āsphoṭayati aufschlagen, klatschen (z.B. Rām. V, 42, 31 f.; MBh. III, 146, 81, cf. 61 f., 63; VII, 180. 4; X, 8, 149, cf. 157; XII, 261, 41) und āsphoṭa in den Wörterbüchern. Nach Bhaṭṭ. ist es eine mit Leder überzogene, mit einer Katapultenstange versehene Maschine, Erde und Steine zu schleudern.

22 C., Bhaṭṭ. und Gaṇ. haben dazu noch utpāṭima. »Utpāṭima ist dazu da, Pfosten und was sonst in die Erde eingegraben ist, herauszureißen, udghāṭima, Türme und Mauern einzureißen.« All diese Wörter auf ima aber sind ihrer Bildung nach passivisch (vgl. z.B. prāvartima 60, 15 f.; 117, 1 ff.). Danach wäre eher an das Abgeschossene selber zu denken, an »das, was man aufschlagen macht«, das »was aufgerissen wird« oder »aufbirst, in Stücke springt«. Wir sind leider auf Bhaṭṭ. angewiesen, obwohl er sicherlich nicht immer zuverlässig ist, ja öfters greifbar Verkehrtes sagt.

23 »Ein mit Keilen beschlagener großer Pfosten, oben auf die Mauer gestellt.« Etwas ähnlich Rāma zu Rām. I, 5, 11: »Eine aus einer Eisenlast gemachte, zur Verteidigung der Stadtmauer dienende, oben auf diese hingestellte Art Waffe«. Befestigt ist sie mit Stricken (Rām. VI, 60, 54). Als auf den Toren postiert und schwer zu handhaben finden wir sie MBh. XII, 69, 45. Geschleudert wird sie z.B. auch Rām. VII, 23, 49; 28, 14 und öfters im MBh. Sogar ein Einzelner schleudert sie da, so dass man mehrere Male an eine einfache Wurfwaffe denkt (z.B. MBh. VI, 113, 39 ff.). Oft hören wir, dass sie sacakrā, cakrayuktā, catuścakrā und dvicakrā sei, also mit Rädern versehen (z.B. VII, 199, 19; VII, 27, 32; 179, 36 ff.). An der letztgenannten Stelle ist sie dick, mit Eisenplatten beschlagen und zerschmettert vier Pferde auf einmal Einige weitere Stellen aus dem MBh. wären: I, 207, 34; V, 87, 30; VII, 97, 29; 114, 82; VIII, 14, 37; 27, 32; 59, 42; IX, 26, 31. Mir ist aber Hopkins, Ruling Caste nicht zur Hand, wo gewiss noch mehr zu holen wäre, als aus den paar Notizen, über die ich im Augenblick verfüge.A2

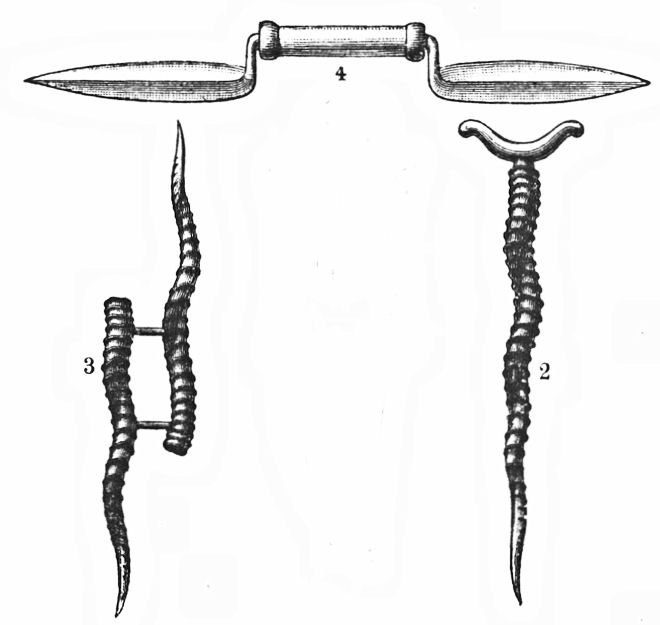

24 »Ist ganz aus Metall gemacht, 4 hasta lang, hat eine Spitze gleich dem Blatt des Karavīrabaumes und ist hinten (wo man sie anfasst), wie eine Kuhzitze.«

25 »Auch diese ganz aus Metall oder auch mit Holz innen drin, 24 aṅgula lang, mit 2 pīṭha (Rücken, Sham. handle) versehen.« Das gäbe nur anderthalb Fuß.

26 Nach einem von Gaṇ. mitgeteilten Śloka sind die besten kunta 7 hasta lang, die mittleren 6, die kleinsten 5. Ein hasta beträgt anderthalb Fuß. Bhaṭṭ. sagt, der kunta sei von Holz.

27 »Mit drei Spitzen, an Länge gleich dem kunta.«

28 »Gleich dem kunta, aber mit breiter Schneide.«

29 »Śūla ist eine Stange ohne festgesetzte Länge mit nur einer Spitze.« Tomara »eine Lanze mit pfeilförmiger Spitze, 4, 41/2 und 5 hasta lang«.

31 »Ist ein prāsa (Wurfspeer) mit eberohrförmiger Spitze.«

32 »Ganz aus Metall gemacht; hat an beiden Enden eine dreieckförmige Schneide und den Griff in der Mitte. Ist 20, 22 und 24 aṅgula lang.«

33 »Dies ist ein mit der Hand geworfener Pfeil, gleich einem tomara.« Ein von Gaṇ. mitgeteilter Śloka sagt, er wiege 7 karṣa, 2 pala und 9 karṣa, je nach seinen drei Arten. Er erscheint z.B. auch MBh. K VIII, 85, 12.

34 »Von der Größe eines prāsa und ganz aus Metall.«

35 Gaṇ. hat die von Sham. vorgeschlagene Lesart halamukhāni, also »mit pflugscharähnlicher Spitze«. Wir müssen eben im Gedächtnis behalten, dass die urtümliche Pflugschar nur eine Art Spitze ist (der Pflug ist ein »Holz mit eiserner Spitze« [kāṣṭham ayomukham] Manu X, 84; MBh. XII. 262, 46).A3

36 Gaṇ. hat denselben Text wie Sham. Wunderlich aber ist da zunächst, dass so eine gewöhnliche Bogenart wie śārṅga nicht erscheint, dagegen aber die allgemeine Bezeichnung dhanus als einzelne Bogenart. Sodann müsste nach dem sonst streng durchgeführten Schema der Gattungsname am Ende kommen. Der ist nun dhanūṃṣi. Endlich deutet das lange ā von druṇa auf einen Verlust; denn nur das Neutrum hat die Bedeutung Bogen. Folglich wird zu lesen sein: kārmukakodaṇḍadruṇacārṅgāni dhanūṃṣi: »Die Bogen sind gemacht aus Weinpalmenholz ... und heißen dann (nach der Reihenfolge des Materials): kārmuka, kodaṇḍa, druṇa und śārṅga.« Druṇa, von derselben Wurzel wie dāru, heißt also »das Hölzerne«. Dārava aus dāru gemacht, könnte auf Pinus deodara bezogen werden. Doch heißt es gewöhnlich allgemein: »von Holz«. Dass Hartholz dazu verwendet wird, ist selbstverständlich.

37 Hier hat auch Gaṇ. gavedhu. Aber auch an unserer Stelle wird Sida retusa, nicht Coix barbata, gemeint sein.

38 Asiyaṣṭi »Schwertgerte«, ein gewöhnlicher Ausdruck für Schwertklinge. Bhaṭṭ. sagt, diese Waffe sei breitklingig, dünn und lang.

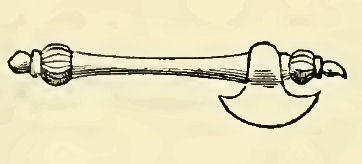

39 »Stammzerschneider, Stammfäller,« Art große Axt nach dem Komm. Natürlicher schiene mir »Stammzerspalter«, (eiserner) Keil. Vom Beil (paraśu) heißt es bei Bhaṭṭ., es sei ganz aus Metall gefertigt, 24 aṅgula lang und habe ein halbmondförmiges Blatt. Paṭṭiśa (oder wie Sham., Jolly und Gaṇ. drucken, pattasa, was nur eine Dialektform sein wird) ist nach Bhaṭṭ. eine Art dreispitziges Beil. Seine andere Erklärung: »Metallstange mit Dreispitz an beiden Enden« ist wenigstens hier ein Unsinn. Das wäre ein sauberes Werkzeug für sterbliche Menschen. Die gleichnamige Waffe wird von Nīl. im MBh. (z.B. I, 19, 14 f.) als eine Art zweischneidiges, scharfes Schwert erklärt. Die drei Spitzen aber erscheinen auch sonst. Hier wäre am ehesten eine Art Karst, hackenartig unten, zinkig oben, zu vermuten, oder vielleicht eine zweischneidige Axt. Allem Anschein nach wurde dies Werkzeug zum Kampf und zur Arbeit gebraucht.

40 Goṣpaṇa bedeutet nach Sorabji »Katapult«. Bhaṭṭ. aber sagt: goṣpaṇākhyayaṣṭiviśeṣaḥ, und bei der Deutung von āsphoṭa 101, 18 heißt es bei ihm: sagoṣpaṇayaṣṭyupeta. Katapult scheint hier etwas ungeschickt, weil dieser ja eine Art yantra oder Maschine ist, was freilich auch von goṣpaṇayaṣṭi gilt. Eine katapultähnliche Vorrichtung haben wir auf jeden Fall.

41 Wörtlich wohl »Schlangenbäuchlein«. Der Vergleich der menschlichen Finger mit Schlangen ist aus dem Nalalied bekannt. Das »Eisennetz« bedeckt nach Bhaṭṭ. den ganzen Leib mit Einschluss des Kopfes, das »Eisennetzchen« lässt den Kopf frei, beim »Eisenplattenkleid« (oder »Eisenzeugkleid«) sind die Arme (und natürlich auch der Kopf) unbedeckt, während der »Eisenpanzer« Brust und Rücken schützt. Wahrscheinlich aber sollte statt »Eisen« »Metall« (loha unedles Metall) stehen. Es ist mit Gaṇ. zu lesen: lohajālajālikāpaṭṭakavacasūtrakaṃkata-. So allem Anschein nach auch Bhaṭṭ.

42 »Weinpalmenwurzel«? »Cymbelboden«? Bhaṭṭ. sagt: »Ein Schild aus Holz.«

43 Dasselbe wie der »Unwiderstehliche, aber die Ränder von Eisenstreifen umschlungen«. Was aber der Unwiderstehliche selber ist, erklärt auch Gaṇ. nicht näher. Jedenfalls ist es ein Schild aus Holz und besonders stark.

44 Als Beispiele des Gaukeltrugs (aindrajālika) erwähnt Bhaṭṭ.: ein kleines Heer als groß und ein Feuer vorzutäuschen. Genaueres gibt Kām. XVIII, 60–61: »Durch Gaukeltrug zeigen sie dem Feinde: Wolken, Finsternis, Regen, Feuer, Berge und Heere in der Ferne mit ihren Bannern, Verstümmelte, Zerfetzte, Blutüberströmte, um die Feinde in Angst zu setzen.« Im Verlauf des Werkes und besonders im vorletzten oder 14. Buch werden wir eine ganze Blütenlese der Mittel, die auf der Geheimlehre beruhen (aupaniṣadika), kennen lernen.

45 Also wohl: alle möglichen Unternehmungen, die ausgeführt werden. Oder: wie man Unternommenes zustande bringt? Gaṇ. zieht kārmāntānaṃ ca zum Schlussvers, so dass also in ihm durchweg von Dingen die Rede wäre, die mit den Fabriken zusammenhängen. Das lässt sich nicht halten.

46 Also alles, was auf Siegelung, Stempelung, Marken Bezug hat, hier wohl vor allem die Pässe (mudrā). Ich lese vyājamudriyaṃ oder -mudrikaṃ. Dies könnte auch heißen: »alles dessen, was mit falschen Stempeln und Pässen zusammenhängt«. Dass diese Dinge für einen Mann im Kriegsfach wichtig sind, liegt auf der Hand. Ob aber meine Besserung das Richtige trifft, steht auf einem anderen Blatt. Vyājim wird, abgesehen von der Ungehörigkeit der vyājī an unserer Stelle, dadurch ausgeschlossen, dess Kauṭ. nur die Form vyājī kennt. Uddeyam und unneyam (Bhaṭṭ. und Gaṇ.) = lābham scheint weder sprachlich annehmbar, noch fügt es sich in den Vers. Verswidrig ist auch vyājam ubhayam, wie C. zu verbessern wäre. Möglich schiene vyājamad dvayam (die trugvolle Zweiheit) oder vyājam adbhutam: »Trug und Wunderbares«. Beides entspräche dem aindrajālikam aupaniṣadikaṃ ca. Vgl. das adbhutotpādāna im 14. Buch (Kap. 2).

A1 Lies varāhakarṇa.

A2 Außer dem Epos, über dessen Waffen man bekanntlich viel bei Hopkins, Ruling Caste findet, bringt auch Agnipur. Kap. CCXLVff. eine reiche Sammlung, ganz zu schweigen von Śukran. IV, 7, 381ff., wo uns sogar Kanonen mit und ohne Granatkugeln vorgefahren werden!

A3 Nach Śukran. IV, 7, 429 ist der kunta 10 hasta lang und hat eine Pflugscharspitze."

[Quelle: Kauṭilya: Das altindische Buch vom Welt- und Staatsleben : das Arthaśāstra des Kauṭilya / [aus dem Sanskrit übersetzt und mit Einleitung und Anmerkungen versehen von] Johann Jakob Meyer [1870-1939]. -- Leipzig, 1926. -- Digitale Ausgabe in: Asiatische Philosophie. -- 1 CD-ROM. -- Berlin: Directmedia, 2003. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 94). -- S. 153 - 157.]

"The classification [of arms] adopted by the Hindus differs considerably in different works. The most common arrangement is a twofold one, including under one head all missiles (astra) and under another, all non-missiles (śastra).

The former is then subdivided into four orders, viz:—

1st, missiles cast by machines, yantramukta ;

2nd, ditto hurled with the hand, pāṇimukta ;

3rd, ditto hurled by force of spells, mantramukta ;

and 4th, arms that can be hurled and then retracted, muktasandhārita.

The second class included two orders.

In Wilson's Essay " On the Art of War as known to the Hindus," the classes and orders are reckoned together. This is based closely on the Agni Purāṇa which gives a fivefold division, thus:

missiles cast by machines, such as bows;

cast by the hand, such as javelins;

retractive missiles, such as the lasso and the boomerang;

non-missiles, such as spears, &c.;

natural weapons, as the fist."

[Quelle: Mitra, Rājendralāla <1824-1891>: Indo-Aryans: contributions towards the elucidation of their ancient and mediaeval history. -- London : Stanford, 1881. -- 2 Bde. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Bd. 1, S. 296]

"A typical sea of weapons is casually presented in the following passage (vii. 178.23 ff.): 'they rained upon each other with a stream of weapons—iron clubs, spits, swords, knives, darts, arrows, wheels, axes, iron balls, staves, cow-horns, mortars,' etc., with a last resort to trees torn up, and other native resources of half-demoniac beings such as here engaged. In this passage, under 'clubs,' we have four kinds mentioned, (gadā, parigha, pināka, musala); lances and darts are trebly named (prāsa, tomara, kampana); arrows are of three names (bhalla, śara, nārāca); and there remains the cow-horn and bhindipāla (the former doubtful), and the mortar (ulūkhala); with iron balls that are probably slung or dropped heated on the foe.

But perhaps the best example may be drawn from the opening of the battle-scenes, already referred to for many special kinds of arms. Here we read how the great mass of soldiers drew out in array, and what the arms were: of the common soldier first, and then specially of the knights (v. 155.1 ff.). 'Now the king drew out his forces and divided his eleven armies according to their highest work, their medium ability, and their worthlessness. Then they advanced, armed and provided with the chariot-planks,' with large quivers, with the 'leather protectors of the war-car,' 'with javelins,' and 'quivers for horse and elephant,' with the foot-soldiers' quivers, with metal spears, with heavier wooden-handled spears, with flags and banners, 'with heavy arrows,' with cords and nooses, 'with blankets, with hair-seizers ;' with jars of oil, molasses, or melted butter, sand, and snakes ; with lighted (?) powder of pitch, with bell-hung spears or swords, with 'water heated by iron balls,' and stones, with spits and spears, with 'missiles of wax melted,' and hammers, with trident or spiked staves, with ploughshares and darts (javelins) that are poisoned, with 'baskets with which to fling hot balls, and the box containing these balls resting in the baskets,' with hooked-lances, with wooden breast-plates, with weapons concealed in wood, with 'blocks of wood with iron spikes,' with tiger and leopard skins 'for man and war-car,' with dart and horn, with crooked javelins, with axes, spades, and oil of sesame and flax, and gilded nets. Such was the array of the Kurus, excluding the chariot-description following, where we also find javelins, bows, etc.

These weapons are all retained or discharged by the hand. No mention of the nivartana, or property of (discharging, prayoga, and) recovering missiles, would lead us to suspect a specially adept band of lassoists or boomerangists, though the exercise of this art gave rise to the nivartana superstition, and the latter is elsewhere in the Epic one of the forms of magic power gained by religious meditation. The nooses rarely come prominently into action. They were cast from the raised hand. The iron balls do not appear to be more than one of the beloved missiles mentioned as stone, sand, pitch, potted snakes, etc., etc.—crude and brutal roughness all.

The barbarians are not worse than the natives as to their arms, but are occasionally spoken of in an angry way as using un-Aryan methods. What could be more Aryan, however, than the arms poured out upon Arjuna by the barbarians in general (mlecchas) ? 'They cast upon him the eared reed arrows and iron arrows, the javelins, darts, spears, clubs, and bhindipālas' that the Aryans themselves used. But we learn that the Kirātas use poison (and appear to be blamed for it!); that the Kāmbojas are particularly 'hard to fight with'; that the barbarians generally are 'evil-minded'; that the Śakas are 'strong as Indra' (vii. 112.38 if.); that the barbarians generally use 'various weapons'; that the Kāmbojas, again, are 'cruel and bald'; that the Yavanas carry especially arrows and darts; and that the mountaineers, Parvatīyas, are proficient in throwing stones, an art the Kurus are asserted to be unfamiliar with."

[Quelle: Hopkins, Edward W. (Washburn) <1857 - 1932>: The social and military position of the ruling caste in ancient India; as represented by the Sanskrit epic; with an appendix on the status of woman. -- Reprint from the 13th volume of the Journal of the American Oriental Society (1888). -- New Haven, Conn. : Tuttle, 1889 -- S. 293ff.]

|

50c./d. āyudhaṃ tu praharaṇaṃ śastram astram

athāstriyau 51a./b. dhanuś-cāpau dhanva-śarāsana-kodaṇḍa-kārmukam 51c./d. iṣvāso 'py atha karṇasya kālapṛṣṭhaṃ śarāsanam

आयुधं तु प्रहरणं शस्त्रम् अस्त्रम् अथास्त्रियौ ॥५० ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Bogen:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A bow."

Siehe auch Vers 37a/b.

1 kṛmuka-Holz: von mir nicht identifiziert.

धनुस् - dhanus m., n.: Bogen

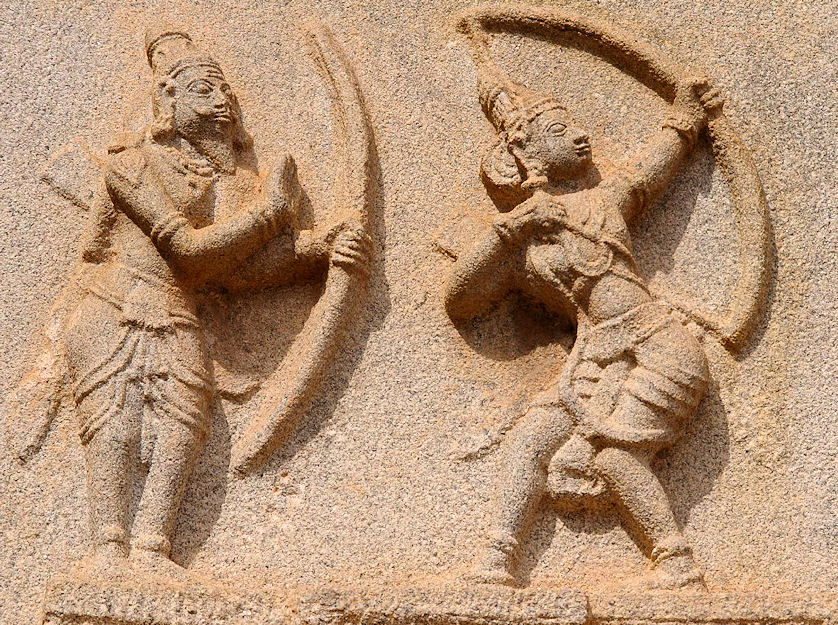

Abb.: धनुषी । Bogenschützen, Hampi - ಹಂಪೆ,

Karnataka

[Bildquelle: Andrea Kirkby. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/andreakirkby/5427449429/. -- Zugriff am

2011-04-16. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

चाप - cāpa m., n.: Bogen

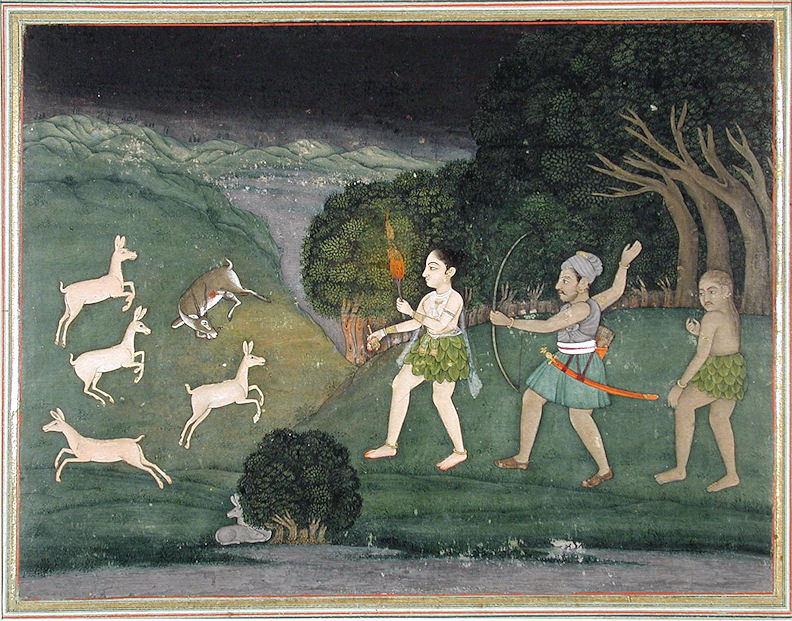

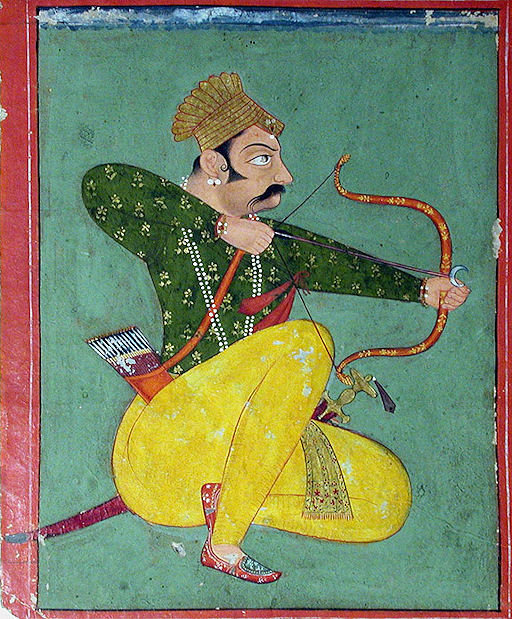

Abb.: चापः । Bhil (भील) Jäger, Uttar Pradesh, ca. 1770

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4835704133/. -- Zugriff am

2011-04-15. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.:

धन्व - dhanva n.: Bogen

Abb.: धन्वम् । Bishan Singh mit Pfeil und Bogen, Himachal Pradesh, ca. 1780

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4838494632/. -- Zugriff am

2011-04-15. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

शरासन - śarāsana n.: "Pfeilschleuderer", Bogen

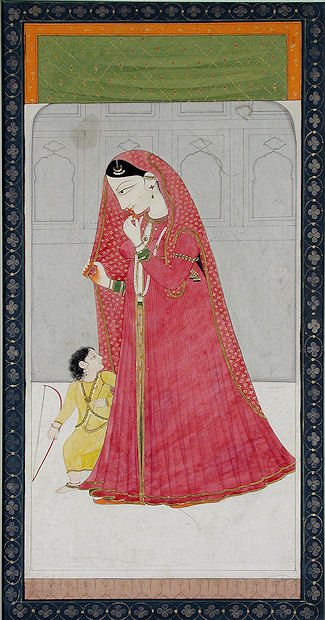

Abb.: शरासनम् । Kind mit Bogen, Himachal Pradesh, ca. 1820

[Bildquelle: Asian Curator at The San Diego Museum of Art. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/asianartsandiego/4837872801/. -- Zugriff am

2011-04-15. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

कोदण्ड - kodaṇḍa n.: Bogen

Abb.: कोदण्डम् । Pfeilfischen, Kerala

[Bildquelel: Matthew Stevens. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/matthewstevens/5407096624/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-14. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung,

keine Bearbeitung)]

कार्मुक - kārmuka n.: wirksam, aus kṛmuka-Holz, Bogen

Abb.: कार्मुकम् । Nur-ud-din Salim Jahangir (نورالدین

سلیم جهانگیر) (1627 - 1569), Delhi, 19. Jhdt.

इष्वास - iṣvāsa m.: "Pfeilschleuderer", Bogen, Pfeilschütze

Abb.: इष्वासौ । Kāma und Rati, Lithographie, Mysore -

ಮೈಸೂರು, heute Karnataka, ca. 1845

"Bogen, eine Waffe zum Schießen von Pfeilen oder Kugeln.

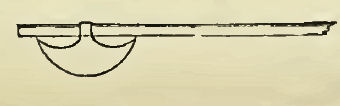

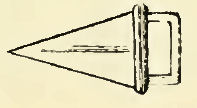

Fig. 1. Einfacher Bogen.Der einfache Pfeilbogen (Fig. 1) ist ein elastischer, fester, in der Regel aus Holz oder Bambus, sehr selten aus Horn bestehender, 0,8–3 m langer Bügel, dessen beide Enden mittels einer aus tierischer Sehne, Pflanzenfaser, Rottang etc. gefertigten Sehne straff miteinander verbunden sind. Er ist der ursprünglichste und auch heute noch am weitesten verbreitete Bogen; er war die einzige in Europa gebräuchliche Form, herrschte ursprünglich, mit je einer Ausnahme, in Afrika und Ozeanien und kam auch für den bei weitem größten Teil Amerikas allein in Betracht.

Fig. 2. Andamanenbogen.In der Regel aus vollem Holze derart hergestellt, dass beide Bogenhälften von gleicher Stärke sind, gibt es in Afrika, Neuguinea, auf den Andamanen und den Neuen Hebriden Bogen, die einfach aus einem Baumzweige bestehen, so dass das obere, dünnere Ende schwächer und biegsamer ist als das andre. Der Bogen der südlichen Andamanen (Fig. 2) besitzt die Gestalt eines zweiblätterigen Ruders. Ähnliche Formen kommen bei den Oregonindianern, am Schirefluß und am Nyassasee vor. Der zusammengesetzte Bogen (Fig. 3) ist ursprünglich auf Asien beschränkt; von Vorderasien ist er dann auch nach den Mittelmeerländern und Nordafrika übertragen worden.

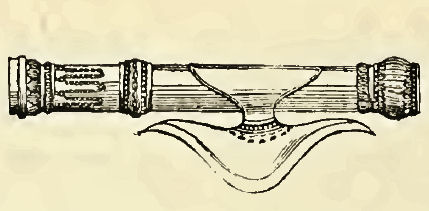

Fig. 3. Zusammengesetzter Bogen.Seinem Bau nach besteht er in jedem Fall aus einem Holzkern, der in der Gegend des Griffes rund, sehr dick und nahezu vollig starr ist, aber sich nach der Seite rasch abflacht und sehr dünn wird. An diesen Holzkern legen sich dann als andre, durch geeignete Manipulationen mit jenem innig verbundene Bestandteile: Sehnenfasern, Hornplatten oder -Stäbe, Holzplatten andrer Art, Bambus etc. Das Ganze wird mit Leder, bei den arktischen Völkern mit Birkenrinde umwickelt; die Japaner überziehen ihren zusammengesetzten Bogen aus drei Holzlängenstreifen, von denen der innerste hartes Holz, die beiden andern, äußern, Bambus sind, außerdem noch mit einem vortrefflichen Lacküberzug.

Fig. 4. Kugelbogen, Hinterindien.Bemerkenswert ist, dass die Größe des zusammengesetzten Bogens in Asien von Westen nach Osten zunimmt; am kleinsten ist der türkische, gleichzeitig ist er auch der wirksamste.

Der größte ist der mächtige Bogen der Chinesen. Von den einfachen Bogen hat die geringste, nur etwa 80 cm betragende Länge der Bogen der Waldvölker des zentralafrikanischen Iturigebietes; dagegen erreichen die Bogen der Indianer am Rio Negro eine Länge von 3 m. Eine Ab- oder Unterart des zusammengesetzten Bogens ist der verstärkte Bogen In der Hauptsache aus einem langen Stabe bestehend, wird er durch Anfügen von dünnen Holzleisten, durch Anwickeln von Sehnen, Ausziehen von Ringen, Umwickeln mit Sehnen etc. elastischer und kräftiger gemacht. Solche verstärkte Bogen gibt es in Alaska, in Westpolynesien, auf Neuguinea und bei den Pygmäen am Kivusee in Afrika.

Eine in Hinsicht auf das Geschoß merkwürdige Abart des Bogens ist der Kugelbogen (Fig. 4). Statt der Pfeile schleudert er taubeneigroße Tonkugeln nach dem Ziele (Vögeln und andern kleinen Tieren). Er kommt in Hinterindien und dem nordöstlichen Südamerika vor und besteht entweder aus zwei, durch Stege verbundene Einzelbogen, zwischen denen das Geschoß dann durchfliegt (Fig. 4), oder einem einfachen Bogen, dessen Enden so gebogen sind, dass die Geschoßebene seitlich zu der Handhabe vorbeiführt.

Verschieden wie die Gestalt, der Bau und das Material der Bogen ist ihre Spannweise. Meist ist sie so straff, dass beim Schuss die vorschnellende Sehne die linke Hand nicht berührt; in andern Fällen würde sie diese indes empfindlich treffen, wenn nicht Schutzmaßregeln getroffen würden. Derartige Hand- und Armschutzapparate haben die Form von Platten, Riegeln, Ringspiralen, Kissen, Binden etc. Platten aus Stein, Knochen oder gebranntem Ton sind schon aus vorgeschichtlicher Zeit bekannt; von heutigen Naturvölkern führen derartige Schutzapparate verschiedene Völker Afrikas (Warundi, Obernilvölker, Waldvölker am Ituri, die Wute in Kamerun, die Salomoninsulaner u. a.).

Fast alle alten Völker, Assyrer, Indier, Kreter, Numidier, Skythen, führten den Bogen In den Heeren der Perser und Karthager gab es viele Bogenschützen.

Bei den Griechen, die kunstvoll gearbeitete Bogen aus Antilopengehörn besaßen, waren, wie bei den Römern, die Schützen nicht besonders geachtet, sondern man überließ diese Kampfweise gern geworbenen Hilfsvölkern. Später machte Mohammed den Gebrauch des Bogens zur Religionspflicht, und Türken, Perser, Araber stellten vorzügliche Schützen; auch Hunnen und Mongolen (russisch-tscherkessische Truppen noch 1813) führten den Bogen, dagegen benutzten die Germanen ihn fast nur zur Jagd und ungern im Kriege, wo sie lieber das Wurfbeil und den Wurfspieß brauchten. Erst im Mittelalter kommt er hier mehr in Gebrauch, besonders die englischen »Bogner«, die Flanderer, Burgunder etc. (vgl. Archers) waren sehr berühmt. Der englische Bogen war 1,8, der deutsche 1,2, der italienische 1,5 m lang, erstere beiden meist von Eibenholz, letzterer von Stahl gefertigt. Zur Aufnahme der bis 1 m langen Pfeile (vgl. Pfeil und Pfeilgift) diente der an der rechten Schulter oder am Gürtel getragene Köcher (Fig. 8 u. 9, S. 139). Als Sport wird das Bogenschießen heute noch in England, Frankreich, Belgien und besonders in der Schweiz betrieben. Als höchste Schussweite werden für den Bogen angegeben aus dem Altertum 500 m, aus Sportkreisen der Neuzeit 800 m.

Vgl. Hansard, The book of archery (Lond. 1845); Longman und Walrond, Archery (das. 1894); v. Luschan, Über den antiken Bogen (Benndorf-Festschrift 1898); Derselbe, Zusammengesetzte und verstärkte Bögen (»Zeitschrift für Ethnologie«, 1899); Boeheim, Bogen und Armbrust (»Zeitschrift für historische Waffenkunde«, Bd. 1, 1898); Ratzel, Die afrikanischen Bogen, ihre Verbreitung und Verwandtschaft (»Abhandlungen der Königlich Sächsischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften«, Leipz. 1891); Herrm. Meyer, Bogen und Pfeil in Zentralbrasilien (das. 1895); B. Adler, Die Bogen Nordasiens (»Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie«, Bd. 15, 1902); Demmin, Die Kriegswaffen in ihrer geschichtlichen Entwickelung (Leipz. 1893); Mason, North American bows (»Reports Smithsonian Institution«, 1894); Jähns, Entwickelungsgeschichte der alten Trutzwaffen (Berl. 1899)."

[Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

"The bow: This is the weapon

κατ' εξοχην for, as in the Veda, āyudha is both the general word for weapon and, without limitation, for the bow. More specific names for this weapon are the commonly used words dhanus, cāpa, śarāsana, and (from their material) kārmuka, śārṅga.The 'bowman' is often synonymous with 'charioteer,' but may be used of footmen in the field. The end of the bent bow was the place whence, as the descriptions show, the arrow was shot; and I take it this means that the bow was bent into a circle, so that the arrow head seemed to lie back of the two bow-ends.

The favorite material for making this weapon is the kṛmuka wood, and this word used alone as adjective indicates the bow. The horn-bow appears, however, to nave been the best, for it was this that Viṣṇu used. The Greeks report at an early date the use of cane bows by the Hindus, as well as of iron-tipped cane arrows. The length of the bow is several times spoken of as tāla-mātra, a 'palm' long, which, when compared with the numerical qualification employed in ṣaḍaratni, may probably be interpreted as six cubits in length. But we hear of the bow of a demon being a cubit broad and twelve cubits long, and the shooting-strifes for a wife in the Epic and in the Rāmāyaṇa alike would indicate an (unusual) use of very heavy bows : the scene in the Epic representing far-distant shooting; that in the Rāmāyaṇa, expressly a weighty bow. According to Egerton, five feet is the ordinary length of the Hindu bow (generally of bamboo). As in the Vedic age, the knight held the bow as high as possible: that is, with the shaft level to the eye, and well forward, pulling the arrow back to his ear; and he must therefore have raised the bow perpendicularly, not horizontally, and not have pulled, as did Homer's heroes, to the breast. The great bow so pulled looked like a crescent, or, in view of its terrible appearance, is likened to the weapon of Indra.

Arjuna alone is 'left-handed' (savyasācin), or, more truly, ambidexter, and uses either hand to draw the string.

The string (jyā) of the bow should be made of mūrva-grass. It is a mistake to suppose that (as the Nītip. teaches) the bow was strung with two cords at once. The cord is noosed at each end, and consists of different strands, but bound together into one string. The sound of the bow-string twanging on the hand-guard of leather is often alluded to as one of the common noises of battle.

As to the decorations of the bow, it is generally described first as being 'pure,' that is spotless, and then as 'of gold' or 'golden-backed:' by which we may understand some kind of gliding or gold ornamentation; and this is probably meant when 'gold bows' are spoken of by later works, although among metallic arms. Not only was the bow painted many colors (i. 225.8,9), but it was ornamented with all sorts of gold figures, 'drops of gold,' insects, elephants, etc., distributed (vibhaktāḥ) upon its surface; representations also of the heavenly bodies are to be found upon it; and even gems of value were set in the wood. The range of the bow (bāṇagocara ; dhanu-antara is a technical measurement) is not described as very great, but the force of the shot is represented as terrific. It is difficult to say whether the many stories of heroes slaying elephants and horses with an arrow apiece, overturning chariots, and transfixing armed knights, are all due to poetic exaggeration, or may be based upon relatively good shooting power. Reading as from the point of view of the later writers' knowledge, we should not be inclined to acknowledge any great dexterity in the use of the weapon. The knights are portrayed as wonderful in the strength and rapidity of their shots; but their shooting except for this is rather ineffectual. Their aim was apparently less good than their quickness in reshooting, although a few cases of good shots are mentioned, and the practice of amusing one's self by shooting into the foe's open wounds is largely indulged in by the heroes, and argues well for their skill. But had they really had any great expertness, they would not have wasted so many arrows before killing each other, in the single duels; for, in spite of 'all-protecting armor,' several vital points were exposed, and we often read of one knight wounding another with several successive arrows, yet doing no serious damage.

This brings us to the point of regarding the skill most praised in handling the bow. We find it is the 'quickness and lightness' that the great heroes of the bow are famous for (not sureness), and that the quickness consists in the ability to discharge several arrows at once, as the Hindu says: that is, perhaps, an apparently unintermitted discharge, owing to the quickness of stringing. Thus, for instance, the Hindu conception of the last quotation would be a simultaneous shooting of three arrows. The fiction is carried further. Five hundred arrows are sometimes shot 'in a twinkling,' or expressly 'with one movement.' Thence the common formula describing a fierce fight: 'the sky became clouded with the arrows' of two contestants. A technical term, hastavāpa, 'hand-throw,' was used to characterize this art. The weakness of the special shot was doubtless due to practicing this general discharge of arrows. Wonderful marksmanship, as we understand it, seems to belong to the accretionary legends of the Pāṇḍus, as in the tournament, the description of the svayaṃvara, the unlucky rival of DroṇA, etc. (see below, on Science of the Bow.)

The noise of the bow and twang of the string are objects of the poet's attention; and a favorite scene in the story is the motionless admiration of a whole army gazing upon two heroes engaged in a bow-duel. We notice in such duels that, though the bow is beloved and has a pet name, yet it is often rejected in mid-fight; so that we must suppose the war-car furnished with many bows. The bow itself is often chopped in two with arrows. A single arrow may be driven with force enough to go through a man's head and come out, falling to earth behind him.

The 'law' of the warrior commands that the archer shall attack only the archer. This law is a fiction. Nothing is more common than for a knight first to slay his foe's helpless charioteer and then his proper antagonist. With the fall of the driver the horses usually become unmanageable and flee. 'With arrows drawn to the ear the knight slew the charioteer,' after which the horses galloped away with the empty car."

[Quelle: Hopkins, Edward W. (Washburn) <1857 - 1932>: The social and military position of the ruling caste in ancient India; as represented by the Sanskrit epic; with an appendix on the status of woman. -- Reprint from the 13th volume of the Journal of the American Oriental Society (1888). -- New Haven, Conn. : Tuttle, 1889. -- S. 269 - 274]

|

51c./d. iṣvāso 'py atha karṇasya kālapṛṣṭhaṃ śarāsanam इष्वासो ऽप्य् अथ कर्णस्य कालपृष्ठं शरासनम् ॥५१ ख॥Der Bogen Karṇas heißt कालपृष्ठ - kālapṛṣṭha n.: schwarzrückig |

Colebrooke (1807): "The bow of Karṇa."

"KARṆA. Son of Pṛthā or Kuntī by Sūrya, the sun, before her marriage to Pāṇḍu. Karṇa was thus half-brother of the Pāṇḍavas, but this relationship was not known to them till after his death. Kuntī, on one occasion, paid such attention to the sage Durvasas, that he gave her a charm by virtue of which she might have a child by any god she preferred to invoke. She chose the sun, and the result was Karṇa, who was born equipped with arms and armour. Afraid of censure and disgrace, Kuntī exposed the child on the banks of the Yamun, where it was found by Nandana or Adhiratha, the sūta or charioteer of Dhṛta-rāṣṭra. The charioteer and his wife, Rādhā, brought him up as their own, and the child passed as such. When he grew up, Indra disguised himself as a Brahman, and cajoled him out of his divine cuirass. He gave him in return great strength and a javelin charged with certain death to whomsoever it was hurled against. Karṇa became king of Aṅga or Bengal Some authorities represent his foster-father as having been ruler of that country, but others say that Karṇa was made king of Aṅga by Duryodhana, in order to qualify him to fight in the passage of arms at the svayaṃ-vara of Draupadī. This princess haughtily rejected him, saying, "I wed not with the base-born." Karṇa knew that he was half-brother of the Pāṇḍavas, but he took the side of their cousins, the Kauravas, and he had especial rivalry and animosity against Arjuna, whom he vowed to kill. In the great battle he killed Ghaṭotkacha, the son of Bhīma, with Indra's javelin. Afterwards there was a terrific combat between him and Arjuna, in which the latter was nearly overpowered, but he killed Karṇa with a crescent-shaped arrow. After Karṇa s death his relationship to the Pāṇḍavas became known to them, and they showed their regret for his loss by great kindness to his widows, children, and dependants.

From his father, Vikarttana (the sun), Karṇa was called Vaikartta ; from his foster-parents, Vāsu-sena ; from his foster-father's profession, Ādhirathi and Sūta; and from his foster-mother, Rādheya. He was also called Aṅga-rāja, 'king of Anga' ; Champādhipa, king of Champā; and Kānīna, 'the bastard.'"

[Quelle: Dowson, John <1820-1881>: A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history, and literature. -- London, Trübner, 1879. -- s.v. ]

Abb.:

|

52a./b. kapidhvajasya gāṇḍīva-gāṇḍivau

puṃnapuṃsakau कपिध्वजस्य गाण्डीव-गाण्डिवौ पुंनपुंसकौ ।५२ क। Der Bogen dessen, der einen Affen in der Standarte hat (= Arjuna), heißt:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "That of Arjuna."

"GĀṆḌĪVA. The bow of Arjuna, said to have been given by Soma to Varuṇa, by Varuṇa to Agni, and by Agni to Arjuna."

[Quelle: Dowson, John <1820-1881>: A classical dictionary of Hindu mythology and religion, geography, history, and literature. -- London, Trübner, 1879. -- s.v. ]

|

52c./d. koṭir asyāṭanī godhā-tale jyāghātavāraṇe कोटिर् अस्याटनी गोधा-तले ज्याघातवारणे ॥५२ ख॥ Die Spitze des Bogens heißt अटनी aṭanī f.: Bogenende |

Colebrooke (1807): "Notched extremity of a bow."

अटनी aṭanī f.: Bogenende

Abb.:

| 52c./d. koṭir asyāṭanī godhā-tale jyāghātavāraṇe कोटिर् अस्याटनी गोधा-तले ज्याघातवारणे ॥५२ ख॥ Bezeichnungen für den Schutz gegen den Schlag der Bogensehne:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Leathern fence for the arm."

1 vermutlich war der Bogenschutz aus Waranleder (Varanus bengalensis Daudin, 1802 - Bengalenwaran - Bengal monitor / Common Indian monitor) gemacht. Zu indischen Waranen siehe:

Amarasiṃha <6./8. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Nāmaliṅgānuśāsana (Amarakośa) / übersetzt von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- 2. Dvitīyaṃ kāṇḍam. -- 9. siṃhādivargaḥ. -- 2. Vers 4c - 12b (Säugetiere II und Warane). -- URL: http://www.payer.de/amarakosa2/amara209b.htm

गोधा - godhā f.: Waran1, Bogenschutz, Bogensehne

Abb.: गोधा । Varanus bengalensis Daudin, 1802 -

Bengalenwaran - Bengal monitor / Common Indian monitor, Jim Corbett National

Park (जिम कार्बेट राष्ट्रीय अभ्यारण्य), Uttarakhand

[Bildquelle: Deepak Bhatia. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/zeepack/2913746611/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-14. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

"To protect the left forearm from the abrasion of the bow-string, it was in Vedic times, wrapped in folds of leather, but the sculptures do not anywhere show a trace of this gauntlet. The Egyptians used a slip of leather for the same purpose, but instead of folding it round the forearm, wore it only on the inner side, tied at the wrist and the elbow. In later times, the Indians used metal gauntlets, but I have seen no sculpture of them of an early date."

[Quelle: Mitra, Rājendralāla <1824-1891>: Indo-Aryans: contributions towards the elucidation of their ancient and mediaeval history. -- London : Stanford, 1881. -- 2 Bde. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Bd. 1, S. 304]

"The hand-protectors (aṅguliveṣṭaka, etc.) are of minor importance. They appear to be of constant use, and, properly, are a defense not so much against the foe as against the kinight's own weapons. For their purpose was to protect arm (godhā) and finger from the bow-string. They are called hand-guards and finger-guards, and are made of iguana-skin. All the bowmen are represented as wearing them. Signs that this armor, common as it is, is not present in all cases, and that the bow-string marks were a common feature, remain in the epithets applied to warriors, implying that their arms were scarred from the bow-string. Nevertheless, the bow-string-guard is very old. Probably, therefore, it was confined to the fingers. The noise made by this part of the armor struck by the bow-string is often brought forward."

[Quelle: Hopkins, Edward W. (Washburn) <1857 - 1932>: The social and military position of the ruling caste in ancient India; as represented by the Sanskrit epic; with an appendix on the status of woman. -- Reprint from the 13th volume of the Journal of the American Oriental Society (1888). -- New Haven, Conn. : Tuttle, 1889 -- S. 307f.]

|

53a./b. lastakas tu dhanurmadhyaṃ morvī jyā śiñjinī guṇaḥ लस्तकस् तु धनुर्मध्यं मोर्वी ज्या शिञ्जिनी गुणः ।५३ क। Das Mittelstück des Bogens heißt लस्तक - lastaka m.: Mittelstück des Bogens |

Colebrooke (1807): "Middle of the bow."

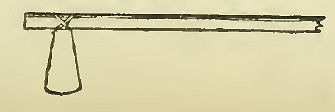

"Der Bogen selbst kann in fünf Abschnitte gegliedert werden: einem meist starren Mittelstück, das als Griff für den Bogenschützen dient, zwei daran anschließende flexible Wurfarme und den beiden abschließenden Bogenenden, an denen die Bogensehne befestigt wird." [Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bogen_%28Waffe%29. -- Zugriff am 2011-06-14]

Abb.: लस्तकः । Leh -

|

53a./b. lastakas tu dhanurmadhyaṃ

maurvī jyā śiñjinī guṇaḥ लस्तकस् तु धनुर्मध्यं मौर्वी ज्या शिञ्जिनी गुणः ।५३ क। [Bezeichnungen für Bogensehne:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "The bowstring."

मौर्वी - maurvī f.: aus mūrvā-Gras (Marsdenia tenacissima (Roxb.) W. & A. 1824) gemacht, Gürtel, Sehne

"Marsdenia tenacissima (R. W.) N. O. Asclepiaceae.

Description.—Twining; [...] flowers greenish yellow.

Fl. April.

Wight Contrib. p. 41.—Icon. t. 590.

Asclepias tenacissima, Roxb. Fl. Ind. ii. 51.—Cor. iii t. 240.

RajmahaL Chittagong. Mysore.

Economic Uses.—The bark of the young shoots yields a large portion of beautiful fine silky fibres, with which the mountaineers of Rajmahal make their bowstrings, on account of their great strength and durability. These fibres are much stronger than hemp, and even than those of the Sanseveria Zeylanica. A line of this substance broke with 248 lb. when dry, and 343 lb. when wet. Wight considers this species not to be a native of the Peninsula. The specimens in the Madras herbarium are—the one from the missionary's garden; the other (A. echinata) was sent to Klein by Heyne, but is not the plant of Roxburgh. The milk exuding from wounds made in the stem thickens into an elastic substance, acting like caoutchouc on black-lead marks.—(Roxb. Wight) Another species, the M. tinctoria, is cultivated in Northern India, being a native of Silhet and Burmah. The leaves yield more and superior indigo to the Indigofera tinctoria, on which account it has been recommended for more extensive cultivation.--Roxb. Wight."

[Quelle: Drury, Heber <1819 - 1872>: The useful plants of India : with notices of their chief value in commerce, medicine, and the arts. -- 2d ed. with additions and corrections. London : Allen, 1873. -- xvi, 512 p. ; 22 cm. -- s.v.]

ज्या - jyā f.: Sehne

Abb.: ज्या । Schütze spannt Bogen, Madhya Pradesh, 11. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Mary Harrsch. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/mharrsch/4470199741/. -- Zugriff am

2011-04-16. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

शिञ्जिनी - śiñjinī f.: "die Klingende", Bogensehne

Abb.: शिञ्जिनी । Rāma kämpft

mit Hilfe Hanumāns gegen seine Zwillingssöhne Kuśa und Lava, ca. 1860

गुण - guṇa m.: Faden, Schnur, Sehne, Seite, Eigenschaft

Abb.: गुणौ । Rāma und Lakṣmaṇa, 18. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia. -- Public domain]

|

53c./d. syāt pratyālīḍham ālīḍham ityādi

sthānapañcakam स्यात् प्रत्यालीढम् आलीढम् इत्यादि स्थानपञ्चकम् ॥५३ ख॥ Die fünf Arten, beim Bogenschießen zu stehen sind:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Two attitudes of shooting. Out of five, viz. 1st. with left foot advanced, and right foot retired ; 2d. With the knee advanced, but the left foot retired ; 3rd. समपदं with both feet even ; 4th. विशाखः with feet a span apart ; 5th. मंडलं with both knees bent."

"Of the different attitudes which were assumed in using the bow, the Agni Purāṇa gives the following description :

"The sampada attitude in shooting, is the standing with the feet even, the two great toes, ankles, and heels being closely opposite each other ; and the position of standing with the feet three spans apart.

Laying the centre of gravity on the toes, and keeping the knees unbent, is the vaiśākha posture.

The attitude in which both the knees appear like a flock of geese, and in which the archer stands with the feet four spans asunder, is called maṇḍala ;

and the ālīḍha posture is said to be that, in which the right thigh and knee are kept unbent, and in which the feet are placed five spans apart, assuming the shape of a plough.

The contrary of the above is called the pratyālīḍha attitude.

The jāta attitude is that in which the left leg should be kept in a crooked position, the left heel at a distance of five fingers from the ankle of the right foot, and the knees twelve fingers apart from each other.

The daṇḍāyata posture is of this description ; the left knee straight, and the right advanced or a little bent, and firmly fixed ;

but when this attitude is such that the knees are two cubits distant from each other, it is called vikaṭa.

The Sampuṭa attitude is said to be the bending the knee double, and keeping the feet raised from the ground (except the forepart), or standing with the legs straight as sticks, and the feet sixteen fingers apart from each other."

[Quelle: Mitra, Rājendralāla <1824-1891>: Indo-Aryans: contributions towards the elucidation of their ancient and mediaeval history. -- London : Stanford, 1881. -- 2 Bde. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- Bd. 1, S. 305]

Abb.: Keine klassische Stellung des Bogenschießens: das gestörte Liebespaar,

1799

|

54a./b. lakṣyaṃ lakṣaṃ śaravyaṃ ca śarābhyāsa upāsanam लक्ष्यं लक्षं शरव्यं च शराभ्यास उपासनम् ।५४ क। [Bezeichnungen für Ziel:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "A butt or mark."

लक्ष - lakṣa n.: Zeichen, Marke, Zielpunkt, Ziel, Wettpreis, Hunderttausend

Abb.: लक्षम् । Rāma und Lakṣmaṇa zielen auf Ravaṇa, 15. Jhdt.

शरव्य - śaravya n.: Ziel (zu śara m.: Pfeil)

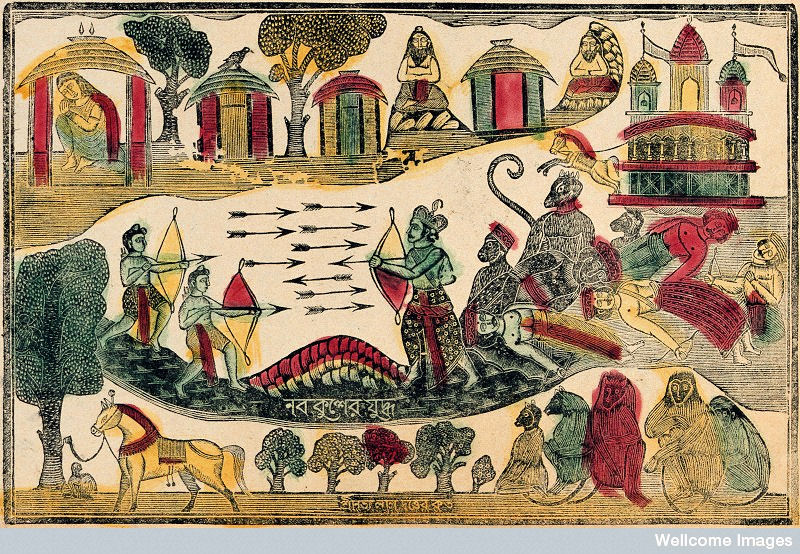

Abb.: शरव्यानि । Rāma kämpft

mit Hilfe Hanumāns gegen seine Zwillingssöhne Kuśa und Lava,

Lithographie, Bengalen

|

54a./b.

lakṣyaṃ lakṣaṃ śaravyaṃ ca śarābhyāsa

upāsanam लक्ष्यं लक्षं शरव्यं च शराभ्यास उपासनम् ।५४ क। [Bezeichnungen für Übung im Bogenschießen:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Archery."

|

54c./d. pṛṣatka-bāṇa-viśikhā

ajihmaga-khagāśugāḥ 55a./b. kalamba-mārgaṇa-śarāḥ patrī ropa iṣur dvayoḥ

पृषत्क-बाण-विशिखा अजिह्मग-खगाशुगाः ॥५४ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Pfeil:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "An arrow."

पृषत्क - pṛṣatka m.: gesprenkelter, Pfeil

Abb.: पृषत्काः । Siat Khnam-Lotterie, Shillong, Meghalaya

[Bildquelle: Joe Coyle. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/onbangladesh/2900835081/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-15. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

Bei der Siat Knam-Lotterie werden die Gewinnzahlen so gewonnen: Khasi-Männer schießen eine vorgegebene Zeit lang so viele Pfeile in einen Strohballen wie möglich. Dann werden die Pfeile im Strohballen gezählt. Die beiden letzten Ziffern der Anzahl der Pfeile im Strohballen sind die Gewinnzahl: z.B. 756 Pfeile = Gewinnzahl 56.

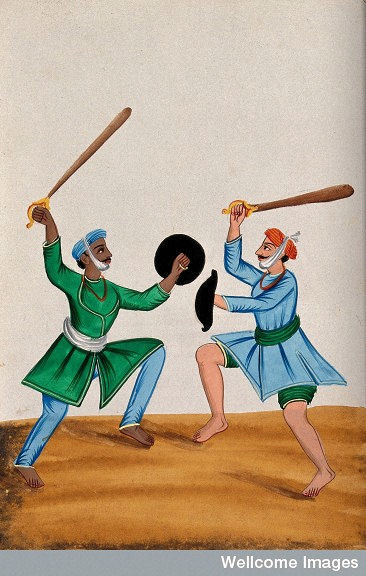

बाण - bāṇa m.: Pfeil, Ziel

Abb.: बाणाः । Mann mit Pfeil, Bogen, Köcher und Schild, 19. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: Wellcome Images. --

Creative Commons

Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

विशिख - viśikha m.: kahlköpfig, stumpfer Pfeil, unbefiederter Pfeil

Abb.: विशिखाः । Pfeile für Siat Khnam-Lotterie, Shillong, Meghalaya

[Bildquelle: Joe Coyle. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/onbangladesh/2900837331/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-15. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

अजिह्मग - ajihmaga m.: nicht krumm gehend, Pfeil

Abb.: अजिह्मगाः । Siat Khnam-Lotterie, Shillong, Meghalaya

[Bildquelle: Joe Coyle. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/onbangladesh/2900835815/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-15. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

खग - khaga m.: in der Luft gehend, fliegend, Vogel, Pfeil

Abb.: खगाः । Kampf zwischen Kṛpa und Śikhaṇḍin, ca. 1670

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

आशुग - āśuga m.: schnell gehend, Pfeil

Abb.: आशुगः । Saraha, Nepal

[Bildquelle: Yaska / Wikimedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

कलम्ब - kalamba m.: Anthocephalus cadamba Miq. - Kadam-Baum, Pfeil

"Anthocephalus Cadamba, Rubiaceae Wild Cinchona (Eng.)

This tree is sacred to Kālī or Pārvatī, the consort of Śiva; it is the Arbor Generationis of the Maratha Kunbis, and a branch of it is brought into the house at the time of their marriage ceremonies. The tree is planted near villages and temples, and is held to be sacred. In Sanskrit it is called Kadamba or Kalamba, and has also many synonyms, such as Sisu-pāla, 'protecting children'; Hali-priya, 'dear to agriculturists,' &c. The Kadamba blossoms at the end of the hot seasons, and its night-scented flowers, form a large, globular, lemon-coloured head, from which the white clubbed stigmas project. They are compared by the Indian poets to the cheek of a maiden mantling with pleasure at the approach of her lover, and are supposed to have the power to irresistibly attracting lovers to one another. This idea is expressed in the following couplet of the Saptasatika of Hāla: -"Sweet-heart, how I am bewitched by the Kadamba blossoms, all the other flowers together have not such a power. Verily Kama wields now-a-days a bow armed with the honey balls of the Kadamba." The flowers are fabled to impregnate with honey the water, which collects in holes in the trunk of the tree. Beal, in his Catena of Buddhist scriptures from the Chinese, informs us that according to the Dirghagama Sutra, to the east of mount Sumeru rises a great king of trees called Kadamba; in girth seven yoganas, height a hundred yoganas, and in spread fifty yoganas. M. Sénart (Essai sur la légende du Buddha) says: -"L'arbre de Bouddha sort spontanément d'un noyau de Kadamba déposé dans le sol; en un moment, la terre se fend, une pousse paraît, et le géant se dresse ombrageant une circonférence de trois cents coudées. Les fruits qu'il porte troublent l'esprit des adversaires du Buddha contre lesquels les Dévas déchaînent toutes les fureurs de la tempéte." (De Gubernatis.) The fruit, which is about the size of a small orange, is eaten by the natives and is considered to be tonic and febrifuge, and its fresh juice is applied to the heads of infants when the fontanelle sinks; at the same time a small quantity mixed with cumin and sugar is given internally. In inflammation of the eyes the bark-juice with equal quantities of lime-juice, opium and alum is applied round the orbit."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 2. -- London, 1891. -- S. 169f.]

मार्गण - mārgaṇa m.: nachspürend, suchend, Pfeil

Abb.: मार्गणाः ।

शर - śara m.: Saccharum bengalense Retz. 1789 - Munja-Gras - Munj Sweetcane, Pfeilschaft, Pfeil

Abb.: शरः । Saccharum bengalense Retz.

1789

[Bildquelle: LRBurdak / Wikipedia. -- GNU FDLicense]

"Saccharum sara, Roxb. [...] The seed of this grass appears to be used only in famine times, or by some of the wild tribes who use the stem for making arrows."

[Quelle: Pharmacographia indica : a history of the principal drugs of vegetable origin met with in British India / by William Dymock [1834-1892], C. J. H. Warden and David Hooper [1858-1947]. -- Bd. 3. -- London, 1893. -- S. 621]

पत्रिन् - patrin m.: befiedert, Vogel, Pfeil

Abb.: पत्री । Siat Khnam-Lotterie, Shillong, Meghalaya

[Bildquelle: Seema K K. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/kkseema/835390684/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-15. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

रोप - ropa m.: "Aufsteiger", Pfeil

Abb.: रोपाः । Tod Bhīṣmas, Punjab hills, 18. Jhdt.

[Bildquelle: Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

इषु - iṣu m., f.: "Sender", Pfeil

Abb.: इषवः । Pfeile und Gewehre, Jaipur - जयपुर, Rajasthan

[Bildquelle: David Hamill. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/auldhippo/3516645869/. -- Zugriff am

2011-06-15. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

"Pfeil, in seiner einfachsten Form ein vorn zugespitzter, hinten gerade abgeschnittener oder mit einer Kerbe versehener Stab, der vom Bogen als Geschoß geschleudert oder von der Hand direkt (Wurfpfeil) oder mittels einer Schleudervorrichtung geworfen wird. In dieser einfachsten Form ist der Pfeil heute nur noch bei ganz primitiven Urwaldstämmen Zentralafrikas anzutreffen; in allen übrigen Fällen ist er durch besondere Ausgestaltung der Spitze und des Schaftes weiter ausgestaltet und technisch oder durch Hinzufügen von Gift wirksamer gemacht worden. Alle auf steinzeitlicher Kulturstufe stehenden Völker haben die Holzspitze durch eine solche aus Stein, Horn oder Knochen ersetzt, in tropischen Ländern auch durch solche aus Bambus, Rochenstachel u.a. Von ihnen haben sich aus vorgeschichtlichen Zeiten lediglich die steinernen erhalten, von denen in Europa, Amerika und Asien (Japan) große Mengen gefunden worden sind. Die Feuerländer, Buschmänner, Mittel- und Nordamerikaner haben Steinpfeilspitzen zum Teil bis in die neueste Zeit gebraucht. In allen Erdteilen mit Metallkultur ist die Spitze späterhin aus Kupfer, Bronze oder Eisen gefertigt worden; in Afrika ist der eisenbewehrte Pfeil noch heute fast ganz allgemein verbreitet. Der Schaft erhielt sehr häufig ein sogen. Mittelstück, einen Einsatz von Holz oder Rohr, der in der Schafthöhlung locker sitzt und dadurch das Herausziehen der Spitze aus dem Körper der Getroffenen erschwert oder bei Anwesenheit von Widerhaken unmöglich macht. Bei den Pfeilen der Buschmänner, Kredsch und andrer afrikanischer Völker sind sogar mehrere Mittelstücke ineinandergefügt. Unten erhielt der Pfeil schaft zunächst eine Fiederung oder Einkerbung der Basis. Jene soll dem Pfeilflug eine größere Stabilität verleihen und das Überschlagen verhüten, diese ein sicheres Auflegen auf die Bogenschnur ermöglichen. Meist besteht die Flugsicherung aus einer bis vielen Federn, die radial oder tangential durch Ankleben, Anbinden, Anwickeln, Einstechen befestigt werden; in Zentralafrika und dem Kongobecken treten indessen auch Baumblattstücke, ja selbst Fell- und Lederstücke als »Fiederung« auf. Ohne eine solche Flugsicherung sind nur wenige Pfeilgebiete: in Afrika der gesamte Sudân, die Region am obern Nil und Buschmänner und Hottentotten, im Stillen Ozean sodann ganz Melanesien außer den Neuen Hebriden und Polynesien, soweit Bogen und Pfeil dort überhaupt noch gebraucht werden. Die Kerbe ist in der Regel dreieckig; nur bei den sehr starken Raphiaschäften des Kongobeckens sind sie rechtwinklig aus dem Schastende herausgeschnitten. Bei Rohrschäften dient häufig ein hölzernes Einsatzstück als Kerbenträger. Einseitige Kerben, d.h. solche, bei denen nur ein Kerbenarm stehen gelassen oder aber nur ein Stück fremden Holzes oder Rohres an den Schaft gebunden worden ist, kommen im Hinterlande von Deutsch-Togo vor; sie gehören zu Bogen mit Bambus- oder Rotangsehnen. Kerbenlos sind endlich alle Gebiete, wo relativ dünne Pfeile auf starke Sehnen (Bambus, Rotang) gesetzt werden müssen, wie im afrikanischen Urwaldgebiet und in vielen Teilen Melanesiens, außerdem aber anscheinend überall da, wo die Bogensehne von Daumen und Zeigefinger zurückgezogen wird, wobei beide gleichzeitig auch das Schaftende des Pfeiles zwischen sich halten." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

"The arrows. The Epic describes arrows of two chief sorts, vaiṇava, 'made of reeds,' and āyasa, 'made of iron.' Bone arrows appear rarely in late parts. The oldest and commonest names are iṣu (

ιος) and śara (reed). Like the first in meaning is astra, 'missile,' united with it in iṣvastra, the bow, and in the expression kṛtāstra, which, like dhanur-dhara, denotes a fine archer, and is an honorary title of a good knight. Like the second in meaning, but of later use, is bāṇa, a reed, but employed also of iron arrows; while the very common śalya means the arrow-point, and thence the arrow as a whole. Beside these we find bhalla and pradara. the latter rare, and meaning literally a 'splitter;' the former common. The arrow of iron was usually termed nārāca. Other less common forms are discussed below.In regard to the employment of the arrows there is little to be learned, in spite of the long descriptions in the Epic. As said above, they were used to embarrass or slay the foe more by numbers than by the skilful use of one. Nothing is more common than an incredible number of arrows flying across the field between two champions; and a 'rain of arrows' or 'flood of arrows,' forming whenever two heroes contend.

The arrows generally used were, according to indefinite but frequent descriptions, large, long, heavy, sharp, strong, able to pierce armor, capable of slaying elephants, horses, etc. But we find, besides these long (reed) arrows and heavy (iron) arrows, an arrow 'one span long' made of reed, meant for fighting at close quarters, where it could be more quickly 'put to' and discharged.

The normal length of the arrow was that of the axle of the war car. Bound with sinews (snāyu), and well feathered, it has a 'terrible end,' whether made of reed and tipped with steel or wholly of metal. In the reed the epithet 'well-jointed' (suparvam) points to the joints of the reeds being well smoothed. Three joints are recommended. The feathers used were of various kinds; hawks, flamingos, and herons furnish the sorts most used, various birds being sometimes represented in the feathering of one arrow.

The sharpness of the arrow is naturally often alluded to, the point (mukha, vaktra, aqra) and edges (dhāraā being 'sharp as flame,' or 'sharp as a hair,' for they were ' whetted on stone.' The other end of the arrow in adorned with what is often called the 'golden' jpuṅkhai. When applied to a 'knife-arrow,' we find the puṅkha of silver. To drive the arrow up to this part was a special feat. The puṅkha, then, was a metal end attached to the main shaft, and was probably added for the purpose of making a securer notch (the notch itself being called kuḍmala), and opposed to śṛṅga, the sharp end (viii. 34.18-19): a hold alike for string and feathers. Oiled arrows are often referred to, and fire may have been applied to them thus oiled, as we find them spoken of independently as 'glowing;' but I am inclined to think that, if arrows really lighted had been used, more than this epithet would remain to prove it; for the 'glowing,' like the 'flame,' of an arrow is poetical for heat, and probably refers only to its sharpness and its fiery touch ; and the word is used where no fire is necessarily imaginable (as of a sword), and where none is certainly discoverable. Moreover, these 'glowing arrows' never kindle wood. From the effect, then, or lack of effect, I think it doubtful if fire was used; though the mention of 'ignited' arrows in Manu may induce some to interpret dīpta as really enkindled. The question whether poisoned arrows were used in war has been, I think, unsatisfactorily answered. Wilson says that (bamboo or wood) arrows were not poisoned except in the chase. This is one of those statements, based on a study of ideals, that must-be modified by facts. The last part is not wrong; in the chase poisoned arrows are alluded to in the pseudo-Epic quotation given above, where we read of hunting with 'poisoned arrows'; yet it is mentioned elswhere that hunting was done with 'pure' (i. e. unpoisoned) arrows, showing such sometimes to have been the case. But as to war, the law forbidding poisoned arrows, and the Epic's special statement that one 'honorable fight' took place where 'poison' was not used, show that lipta or poisoned arrows were generally employed. It is also possible that the common epithet 'resembling a snake' may refer to the poison, though perhaps better understood of the sharp bite, the whizzing sound, and the darting motion.

More than this in regard to the arrows used in the Epic must be confined to the special uses of the different sorts, though we are here chiefly driven to the interpretation of the name for the kind, and the special peculiarities of each mentioned. For, as a general thing, the arrows are alluded to in the mass, and only here and there do we find particular descriptions. The meagre accounts show us, however, many more names than we can interpret. Probably several of these are merely epithets applicable to different sorts: thus, the gokarṇa, 'cow-ear,' may be of any material, and the gold tips of the 'reed' may be equally applicable to the horn-arrow. I shall, then, only attempt to gather what I have noted of each, without believing that the individual description should be confined to the arrow described. Only important is the construction of the possible Hindu arrow, though I regret not finding more details.

Bhīma's favorite arrow was the 'crescent-head,' with which one can cut a head from a body, or divide a bow in two. This, the 'very sharp' ardhacandra, is frequently named with others, the 'broad,' añjalika, the vatsadanta, bhalla, etc. (vi. 92.33 ; 94.3 ; vii. 21. 21; 115. 27). The vatsadanta is named about as often as the ardhacandra. It is, from its name, a calf's-tooth-shaped arrow, and from the descriptions is particularly sharp. One wards off an onrushing foe with it (vii. 25.40). It is classed with the little known 'broad vipāṭha'' (iv.42.7; vii. 38.23), and its action is, perhaps, as well as anywhere, thus exhibited: 'He laid the tooth-shaped arrow on the string—swift as the wind it was—he drew it back until it touched his ear, and Sātyaki he pierced upon the belly. Right through the body's guard it cut, and through the body—the arrow with its feathers and it's metal butt—and dripping with blood it entered the earth.' (vii. 118. 49 ff.).

The kṣurapra in a knife shaped arrow: that is, with a blade- head ; and, like all these broad arrows, it cuts, if need be, a head from a body. It is spoken of as excessively sharp, and seems to have the legally forbidden 'ears,' or prongs bending back on the fish-hook plan. We have in Droṇa's leadership a list of arrows comprising nārāca, vatsadanta, bhalla, añjalika, kṣurapra, ardhacandra ; and again a 'half-nārāca' with nārācas of iron. The nārāca here mentioned is of iron, and is, according to another passage in the pseudo-Epic (xiii. 104.34), distinct from the nālīka (where we also find the karṇin or 'be-eared' arrow differentiated from the nālīka). The expression kṣudra-nārāca is here employed, literally 'small.' We find an antithesis between these again expressed in the battle-scenes, and in the Rāmāyaṇa the nālīka and (bahu-)nārāca are differentiated as if dissimilar.

The nārāca lias a gilded or silvered point, and is perhaps the special name for the bāṇā āyasāḥ, or iron shafts, mentioned above. It is generally defined as wholly of iron, but is described as 'feathered' (iv. 42.6). The nālīka, of reed nominally, may perhaps also have been of metal, as this is the name in modern literature of the iron musket. The sharpness of the nārāca, its smallness compared with the reed, its gold or silver point and gold puṅkha, are the main characteristics dwelt upon in this weapon.

Respecting the word sāyaka, although literally merely a projectile, it appears to be in most cases confined to the sense of arrow. But the same word is used of a sword, and the instrument is now and then spoken of as flung.

Out of the various lists of arrows which are mentioned as encumbering the ground with other arms, we may occasionally find descriptive epithets applied to names that are themselves nothing more than this. Thus mārgaṇa is defined as an arrow, and we may say that it is characterized as a 'sharp' arrow; but the information must simply be referred to the arrow in general; for mārgaṇa itself is only an epithet of the 'eager' arrow. Our knowledge, then, except in a few cases, is not increased by such descriptions. Names and names only are the pṛṣatka and añjalika, often mentioned as (epithet of) arrows, meaning apparently in one case that the arrow is speckled, in the other that it is barbed. Vipāṭha seems also to be a general term for arrows; but further than being broad, of iron, and yellow, i. e. gilded, the arrows thus named bear only universal characteristics. A further universal epithet of any arrow, often used as name, is ' the feathered one' (pattrin).

The same passage containing the description of vipāṭha speaks of 'boar-ear' arrows: that is, arrows forbidden by the law-books, with barbs at the heads, but often spoken of in the Epic.

I referred above to the poisoned arrows spoken of by the poet in one scene as discarded in honorable fight. But the list of dishonorable weapons here alluded to shows us many that must have been in use, though legally (perhaps later) forbidden. The 'ear arrows,' poisoned arrows, goat-horn arrows, needle-shaped arrows, arrows of monkey-bone, of cow-bone, and of elephant-bone; arrows so fractured as to break in the flesh; 'rotten' arrows; and crooked arrows; while the nālīka is also, strange to say, here spoken of with the implication of baseness in its use, which the commentator explains by defining nālīa as an arrow that enters breaking in the flesh, and cannot be withdrawn on account of its small size. The Rāmāyaṇa shows here, as it generally does in the battle-descriptions, thoroughly Epic usage.

We must suppose either that the barbed, poisoned, torturing arrow scorned in the law code of Manu and late Epic was a new invention of that period, or else that it was used from ancient times, and gradually began to be inveighed against by the popular law (Manu) and Epic, as too cruel for a more advanced age. The latter seems more reasonable."

[Quelle: Hopkins, Edward W. (Washburn) <1857 - 1932>: The social and military position of the ruling caste in ancient India; as represented by the Sanskrit epic; with an appendix on the status of woman. -- Reprint from the 13th volume of the Journal of the American Oriental Society (1888). -- New Haven, Conn. : Tuttle, 1889. -- S. 275 - 281]

|

55c./d. prakṣveḍanās tu nārācāḥ pakṣo vājas triṣūttare प्रक्ष्वेडनास् तु नाराचाः पक्षो वाजस् त्रिषूत्तरे ॥५५ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Eisenpfeil:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Iron arrows."

प्रक्ष्वेडन - prakṣveḍana m.: summend, Eisenpfeil

Abb.:

प्रक्ष्वेडनः

। Surajmal von Bundi (बूंदी), Rajasthan, ca. 1700

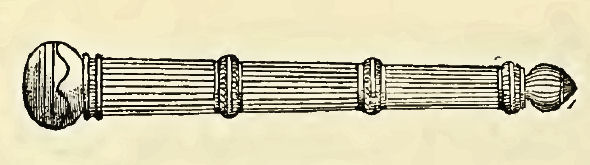

नाराच - nārāca m.: "eine Art Pfeil, angeblich ein eiserner" (PW)

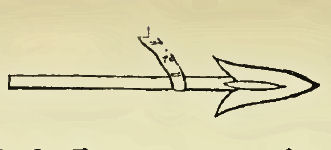

Abb.: नाराचः (?) । Bambuspfeil mit Metallspitze, Indonesien

[Bildquelle: Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) / Wikimedia.

-- Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, share alike)]

|

55c./d. prakṣveḍanās tu nārācāḥ

pakṣo vājas triṣūttare प्रक्ष्वेडनास् तु नाराचाः पक्षो वाजस् त्रिषूत्तरे ॥५५ ख॥ [Bezeichnungen für Pfeilfeder:]

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Feather of an arrow."

पक्ष - pakṣa m.: Flügel, Feder, Gefieder, Befiederung

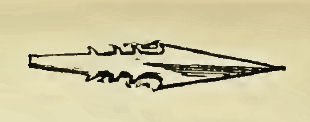

Abb.: पक्षः । Befiederung eines Pfeils

[Bildquelle: James Cram / Wikimedia. -- Public domain]

वाज - vāja m.: Raschheit, Wettlauf, Renner, Flügel, Pfeilfedern

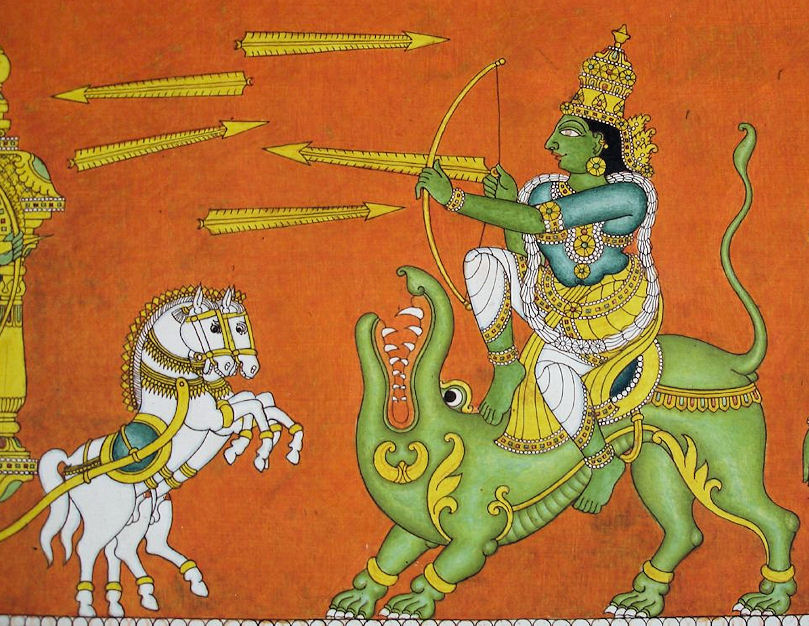

Abb.: वाजाः । Tempelgemälde, Madurai, Tamil Nadu

[Bildquelle: Ed Mitchell. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/edmittance/434035282/. -- Zugriff am

2011-04-16. --

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, share alike)]

|

55c./d.

prakṣveḍanās tu nārācāḥ pakṣo vājas

triṣūttare प्रक्षेव्डनास् तु नाराचाः पक्षो वाजस् त्रिषूत्तरे ॥५५ ख॥ Die folgenden Wörter sind Adjektive. |

Colebrooke (1807): "The following admit the thee genders."

|

56a./b. nirastaḥ prahite bāṇe viṣākte digdha-liptakau निरस्तः प्रहिते बाणे विषाक्ते दिग्ध-लिप्तकौ ।५६ क। Zu einem abgeschossenen Pfeil sagt man निरस्त - nirasta 3: hinausgeworfen, weggeworfen, geschossen |

Colebrooke (1807): "Shot, as an arrow."

|

56a./b. nirastaḥ prahite bāṇe

viṣākte digdha-liptakau निरस्तः प्रहिते बाणे विषाक्ते दिग्ध-लिप्तकौ ।५६ क। Bezeichnungen für einen giftbeschmierten (अक्त - akta 3: gesalbt, beschmiert) [Pfeil]:

|

Colebrooke (1807): "Poisoned arrow."