mailto: payer@payer.de

Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois: Materialien zur buddhistischen Psychologie. -- 3. Die Beobachtungsmethode: Satipaṭṭhāna. -- Fassung vom 2006-12-10. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/buddhpsych/psych03.htm

Erstmals publiziert: In Bearbeitung!

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung Wintersemester 2006/2007

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Übersetzers. Das Copyright für zitierte Texte lieget bei den jeweiligen Rechtsinhabern.

Diese Inhalt ist unter einer

Creative Commons-Lizenz lizenziert.

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Buddhismus von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Text siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944-- >: Materialien zu einigen Lehrreden des Dīghanikāya. -- D II, 9: Mahāsatipaṭṭhānasutta. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/dighanikaya/digha209.htm

Siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Einführung in den Theravâdabuddhismus der Gegenwart. -- Teil 4: Der Mönchsweg: 4.5. Meditation. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/theravgegenw/therav07.htm

"Obwohl die Charakteristischen Züge der Satipatthāna-Methode so einfach und klar erscheinen, nachdem man sie einmal kennen gelernt hat, so waren doch die Vorstellungen von dem in der Lehrrede dargelegten Übungsweg für lange Zeit undeutlich geblieben. Soweit des Verfassers Kenntnis geht, war es erst zu Beginn dieses Jahrhunderts, daß ein burmesischer Mönch, U Narada, nur auf einen knappen Hinweis gestützt, sich die Eigenart des Übungsweges Rechter Achtsamkeit erarbeitete und anderen lehrte. Schon in jungen Jahren war er auf der Suche nach einer Meditationsmethode, die einen direkten Zugang zum Hohen Ziel der Buddha-Lehre bot. Auf seinen Wanderungen durch Burma fragte er danach bei solchen, von denen er Belehrung erhoffte, doch konnte er keine ihn befriedigende Unterweisung erhalten. Als er zu den Meditationshöhlen in den Sagaing-Bergen kam, wies man ihn zu einem Mönch, der im Rufe stand, jene hohen, zum Heiligkeitsziel führenden Pfade (ariya-magga) erreicht zu haben, die mit dem «Stromeintritt» (sotāpatti) beginnen. Von U Narada befragt, antwortete jener, warum denn der Frager außerhalb des Butdhawortes suche, das ja alles Nötige enthalte. Sei denn nicht darin der Einzige Weg, Satipatthāna, verkündet worden? Diesen Hinweis nahm Narada auf und studierte zunächst nochmals sorgfältig die Lehrrede und deren alten Kommentar, über Sinn und Anwendungsweise tief nachdenkend. Darauf und auf eigene ernste Übung gestützt, entwickelte er die Grundsätze und die Praxis jener Übung in Rechter Achtsamkeit, die in diesem Buche dargestellt ist. Hiermit begann eine neue Tradition in der Übung dieses alten, doch nie veraltenden Weges gründlicher Geistesschulung. Für diese hat sich die Bezeichnung «Burmesische Satipatthāna-Schule» eingebürgert, denn es war in Burma, daß dieser alte Übungsweg in seiner Eigenart wieder belebt, ernstlich geübt und weit verbreitet wurde. Viele Schüler des Ehrw. U Narada verbreiteten durch Abhaltung von Meditationskursen die Kenntnis dieses neu entdeckten Übungsweges. Für die hier betonte Anwendbarkeit dieser Methode auch im weltlichen Leben ist es bezeichnend, daß zu des Ehrw. Naradas besten Schülers-Schülern ein burmesischer Laie, Maung Tin, gehörte, der seinerseits nicht nur Laien, sondert auch Mönche unterwies und auch in Klöster eingeladen wurde um Meditationskurse abzuhalten. An einem solchen Kurs nahmen auch zwei singhalesische Mönche teil, denen der Verfasser die erste Kunde von dieser Methode verdankt, soweit sie in der ersten Auflage dieses Buches dargestellt wurde. Die ausführlicheren Übungsanweisungen in der vorliegenden Auflage stützen sich auf Belehrungen und Erfahrungen während des Verfassers eigenen Aufenthaltes in Burma im Jahre 1952.

Der Ehrw. U Narada, in Burma weit bekannt als Jetavan- oder Mingun-Sayado, starb am 18. März 1957, im Alter von 87 Jahren. Viele sind davon überzeugt, daß er das Höchste Ziel der Heiligkeit (arahatta) erreicht hatte. Neben seinen meditativen Errungenschaften war er auch ein bedeutender Gelehrter. In der Pāli-Sprache verfasste er Kommentare zu den «Fragen des Milinda» und zum Petakopadesa, in burmesisch ein Handbuch der Klarblicksmeditation.

Seit den Tagen des Ehrw. Narada hat sich die Satipatthāna Methode mit Hilfe vieler befähigter Meditationslehrer in Burma weit verbreitet. Besonders bedeutend und erfolgreich unter diesen Lehrern ist der Ehrw. Mahasi Sayado (U Sobhana Mahathera), der selber unter dem Ehrw. Narada meditiert hatte. Nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg, im Jahre 1949, wurde er vom damalige Ministerpräsidenten, U Nu, eingeladen, aus seinem Heimatkloster nach Rangun zu kommen und dort als Meditationslehrer zu wirken. In einem Außenbezirk Ranguns wurde ein Meditationszentrum gegründet, genannt «Thathana Yeiktha», wo bis zum heutigen Tage Kurse strikter Meditation für Mönche und Laien abgehalten werden. Dort allein haben, bis 1966, 15000 Personen an den strikten Kursen teilgenommen, und im gesamten Lande 200000. Diese letzte Ziffer schließt diejenigen ein, die in den über 100 Zweig-Meditationsstätten Burmas nach der gleichen Methode übten: selbst unter den einfachen Bergstämmen der Schanstaaten Nordburmas bestehen solche Stätten. Alle diese Meditationszentren (und viele andere mit unterschiedlichen Methoden) wurden von der damaligen burmesischen Regierung unter U Nu mit einer Subvention unterstützt, die auch von der gegenwärtigen Regierung des Landes fortgesetzt wird. Diese Förderung meditativen Lebens seitens einer Regierung war offenbar auch von der Überzeugung geleitet, daß Menschen, die durch solch ernste geistige Schulung gegangen sind, auch im Gemeinschaftsleben ein positiver Faktor sein werden.

Mönche und Laien, Männer und Frauen, jung, und alt, reich und arm, Hochgebildete und Gelehrte, sowie auch einfache Bauern haben sich dieser Geistesschulung mit tiefem Ernst und großer Begeisterung unterzogen. Und an guten inneren Ergebnissen hat es nicht gefehlt. Obwohl es in Burma auch viele und bedeutende Meditationsstätten anderer Methoden gibt, so haben doch an der gegenwärtigen, bemerkenswert starken Welle meditativen Lebens der Ehrw. Mahasi Sayado und seine Schüler den Hauptanteil. Durch ihre Bemühungen hat sich diese Methode auch in Ceylon und Thailand verbreitet, und eine englische Fassung des vorliegenden Buches hat die Kenntnis davon in viele andere Länder getragen.

Ebenso wie der Ehrw. Narada, so vereint auch der Ehrw. Mahasi meditative Reife mit einer umfassenden und tiefschürfenden Kenntnis des buddhistischen Lehrgutes und Schrifttums. Während des 6. buddhistischen Mönchskonzils (Chattha Sangāyanā), das 1954-1956 in Rangun stattfand, hatte daher der Ehrw. Mahasi das ehrenvolle Amt, vor jeder feierlichen Rezitationssitzung des Konzils die auf den betreffenden kanonischen Text bezüglichen Fragen zu stellen, wie es auf dem 1. Konzil nach dem Hinscheiden des Buddha der Ehrw. Arahat Mahā-Kassapa getan hatte. Die literarischen Arbeiten des Ehrw. Mahasi sind in burmesischer und Pāli-Sprache verfaßt. Von englischen Übersetzungen liegen vor: eine Einführung in die Satipatthāna-Praxis; zwei längere Aufsätze über das «Mahā-Satipatthāna-Sutta» und die 40 Meditationsobjekte («Buddhist Meditation and its Forty Subjects»); sowie eine hauptsächlich für fortgeschrittene Meditierende bestimmte Abhandlung, die vom Verfasser dieses Buches vom Pāli ins Englische übersetzt wurde. "

[Quelle: Nyanaponika <1901 - 1994>: Geistestraining durch Achtsamkeit : die buddhistische Satipaṭṭhāna-Methode. -- Konstanz : Christiani, 1975. -- 198 S. ; 20 cm. -- Online: http://www.palikanon.com/diverses/satipatthana/satipattana.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

Im folgenden werden einige Persönlichkeiten vorgestellt, deren Rekonstruktionsversuche von Satipaṭṭhāna einflussreich geworden sind.

Abb.: Ledi Sayadaw

[Bildquelle:

http://www.vri.dhamma.org/general/10dayhill.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

"Ledi Sayadaw This article or section is not written in the formal tone expected of an encyclopedia article.

Please improve it or discuss changes on the talk page. See Wikipedia's guide to writing better articles for suggestions.

Abb.: Ledi SayadawLedi Sayādaw (1846 - 1923) was a famous Theravadin Buddhist monk in Burma. He revived the practice of vipassana meditation and wrote many manuals or expositions (Dipani) on Vipassana. His leading disciple was Saya Thetgyi, a layman. He wrote many books on Dhamma in Burmese in such a way that even a lay person can understand, hence he made Dhamma accessible to all levels of society.This scholarly, saintly monk was instrumental in reviving the traditional practice of Vipassana, making it more available for renunciates and lay people alike.

He went on to learn the technique of Vipassana still being taught in the caves of the Sagaing Hills; and after mastering the technique, he began to teach it to others. His vihara (monastery) was in Ledi village near the town of Monywa. There he meditated most of the time and taught the other bhikkhus.

At other times he traveled throughout Myanmar. Because of his mastery of pariyatti, he was able to write many books on Dhamma in both Pali and Burmese languages such as, Paramattha-dipani (Manual of Ultimate Truth), Nirutta-dipani, a book on Pali grammar and The Manuals of Dhamma..

Thus he strengthened pariyatti, and at the same time he kept alive the pure tradition of patipatti by teaching the technique of Vipassana to a few people.

He realized that besides bhikkhus, good lay teachers would need to be developed for the spread of Dhamma. Therefore he made the technique, which had previously been restricted to bhikkhus, accessible to lay people as well. Although he trained some bhikkhus to teach, he also established a lay farmer named Saya Thetgyi as a teacher.

Ledi Sayadaw was perhaps the most outstanding Buddhist figure of his age. He was instrumental in reviving the traditional practice of Vipassana, making it more available for renunciates and lay people alike. In addition to this most important aspect of his teaching, his concise, clear and extensive scholarly work served to clarify the experiential aspect of Dhamma

WritingsExternal links

- Manual of Insight (Vipassanā Dīpanī)

- Manual of Conditional Relations (Patthanuddesa Dīpanī)

- Manual of Right Views (Vipassanā Dīpanī)

- Manual of the Four Noble Truths (Catusacca Dīpanī)

- Manual of the Factors of Enlightenment (Bodhipakkhiya Dīpanī)

- Manual of the Constituents of the Path (Magganga Dīpanī)

- Five Kinds of Light (Alin Kyan)

- 5 Questions on Kamma; Anattanisamsā

- On-line Collection of Writings of Ven. Ledi Sayadaw: http://www.aimwell.org/Books/Ledi/ledi.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-09"

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ledi_Sayadaw. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-27]

Abb.: Saya Thetgyi

[Bildquelle:

http://www.vri.dhamma.org/general/10dayhill.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

"Saya Thetgyi [1873 - 1945] Saya Thetgyi was born in the farming village of Pyawbwegyi, eight miles south of Rangoon. Born in poor family, his formal education was minimal-only about six years. He took up several jobs; as a bullock cart driver transporting rice, as a sampan oarsman and then as a tally-man in the local rice mill. He married Ma Hmyin when he was about 16 years old.

He ordained as a bhikkhu (monk) for some time. At the age of 23, he learned Anapana meditation from a lay teacher, Saya Nyunt.When a cholera epidemic struck the village in 1903, many died, including U Thet's son and young teenage daughter. This calamity affected U Thet deeply, and not finding refuge anywhere he asked permission from his wife and sister-in-law, Ma Yin, to leave the village in search of "the deathless."

Accompanied in his wanderings by a devoted companion and follower, U Nyo, U Thet wandered all over Burma in a fervent search, visiting mountain retreats and forest monasteries, studying with different teachers, both monks and laymen.

Finally he went north to Monywa to learn Vipassana from the Venerable Ledi Sayadaw. He returned to his village after a few years and started teaching Anapana in 1914.

In about 1915, after teaching for a year, U Thet took his wife and her sister to pay respects to Ledi Sayadaw who was then about 70 years old. When U Thet told his teacher about his meditation experiences and the courses he had been offering, Ledi Sayadaw was very pleased

It was during this visit that Ledi Sayadaw gave his walking staff to U Thet, saying:

"Here my great pupil, take my staff and forward. Keep it well. I do not give this to you to make you live long, but as a reward, so that there will be no mishaps in your life. You have been successful. From today onwards you must teach the Dhamma of rupa and nama (mind and matter) to 6,000 people. The Dhamma known by you is inexhaustible, so propagate the sasana (era of the Buddha's teaching). Pay homage to the sasana in my stead.

The next day Ledi Sayadaw summoned all the monks of his monastery. He requested U Thet to stay on for 10 or 15 days to instruct them. The Sayadaw then told the gathering bhikkhus

"Take note, all of you. This layman is my great pupil U Po Thet, from lower Burma. He is capable of teaching meditation like me. Those of you who wish to practice meditation, follow him. Learn the technique from him and practice. You, Dayaka Thet (a lay supporter of a monk who undertakes to supply his needs such as food, robes, medicine, etc.), hoist the victory banner of Dhamma in place of me, starting at my monastery."

U Thet then taught Vipassana meditation to about 25 monks learned in the scriptures. It was at this time that he became known as Saya Thetgyyi (saya means "teacher"; gyi is a suffix denoting respect).

Saya Thetgyi was the first lay teacher of Vipassana since the time of the Buddha. For 30 years he taught meditation to all who came to him, guided by his own experience and using Ledi Sayadaw's manuals as a reference. The village was not far from Rangoon, the capital of Burma under the British, so government employees and city dwellers like Sayagyi U Ba Khin , also came. By 1945, when he was 72, he had fulfilled his mission of teaching thousands."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saya_Thetgyi. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-27]

Abb.: U Ba Khin

[Bildquelle:

http://www.vri.dhamma.org/general/subk.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

"Sayagyi U Ba Khin (March 6, 1899 – January 18, 1971) was born in Rangoon (Yangon; ရန္ကုန္မ္ရုိ့), Burma. He was a student of Saya Thetgyi and was the first Accountant General of Burma. U Ba Khin was a notable teacher of Buddhist vipassana meditation. One of his most prominent students was S. N. Goenka. About Sayagyi U Ba Khin 1899-1971: Sayagyi U Ba Khin was born in Rangoon, the capital of Burma, on 6 March 1899. In March of 1917, he passed the final high school examination, winning a gold medal as well as a college scholarship. But family pressures forced him to discontinue his formal education to start earning money. His first job was with a Burmese newspaper called The Sun, but after some time he began working as an accounts clerk in the office of the Accountant General of Burma. In 1926 he passed the Accounts Service examination, given by the provincial government of India.

In 1937, when Burma was separated from India, he was appointed the first Special Office Superintendent. He became Accountant General on 4 January 1948, the day Burma gained independence.

It was on 1 January 1937, that Sayagyi tried meditation for the first time. A student of Saya Thetgyi-a wealthy farmer and meditation teacher-was visiting U Ba Khin and explained Anapana meditation to him.

When Sayagyi tried it, he experienced good concentration, which impressed him so much that he resolved to complete a full course. Accordingly, he applied for a ten-day leave of absence and set out for Saya Thetgyi's teaching center.

Sayagyi progressed well during this first ten-day course, and continued his work during frequent visits to his teacher's center and meetings with Saya Thetgyi whenever he came to Rangoon.

In 1941, a seemingly happenstance incident occurred which was to be important in Sayagyi's life. While on government business in upper Burma, he met by chance Webu Sayadaw, a monk who had achieved high attainments in meditation. Webu Sayadaw was impressed with U Ba Khin's proficiency in meditation, and urged him to teach. He was the first person to exhort Sayagyi to start teaching.

In 1950 he founded the Vipassana Association of the Accountant General's Office where lay people, mainly employees of that office, could learn Vipassana. In 1952, the International Meditation Centre (I.M.C.) was opened in Rangoon, two miles north of the famous Shwedagon pagoda. Here many Burmese and foreign students had the good fortune to receive instruction in the Dhamma from Sayagyi. Sayagyi was active in the planning for the Sixth Buddhist Council known as Chatta Sangayana (Sixth Recitation) which was held in 1954-56 in Rangoon.

It was Sayagyi U Ba Khin's wish that the technique, long lost to India, could again return to its country of origin and from there spread around the world. For many reasons he could never come to India. He then authorized his student, S. N. Goenka, to teach Vipassana meditation. Sayagyi finally retired from his outstanding career in government service in 1967. From that time, until his death in 1971, he stayed at I.M.C., teaching Vipassana."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U_Ba_Khin. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-27]

Abb.: S. N. Goenka

[Bildquelle:

http://www.events.dhamma.org/images/Gji-sittingBW.jpg. -- Zugriff am

2006-12-09]

"Sri Satya Narayan Goenka (born 1924) is a leading lay teacher of Vipassana meditation and a student of Sayagyi U Ba Khin. Born in Mandalay, Burma to Indian parents, Goenka was raised a Hindu and, as an adult, became an industrialist and leader of the Burmese Indian community. After developing an interest in meditation in an effort to overcome chronic migraines, he began studying with U Ba Khin, a senior civil servant in the newly independent Burmese government. U Ba Khin was a renowned meditation teacher who had played an important role in the Sixth Buddhist Council of 1954-1956 and was one of the leaders of a Vipassana-centered reform movement that had exerted a positive influence on standards in public life. Goenka became U Ba Khin's most prominent successor and went on to found an international network of teaching centers, based at Dhammagiri in India. Goenka emphasizes in his courses and lectures on Vipassana meditation as offering a scientific investigation of the mind-matter phenomenon, and relates that through Vipassana meditation one can observe eight fundamental particles (which he refers to as "kalapas") at the experiential level of one's own mind, not to be confused with the standard model in physics.

It is believed by some that Gautama Buddha stated that, as he taught everything is impermanent -- even his teachings, that they too would someday disappear from the land of their origin, India, and then return to its shores twenty-five centuries after his death. Goenka’s teaching centers in India is heralded by some as the fulfillment of that prediction.

With the ever-growing number of people learning Vipassana from these centers, Goenka tries to ensure that the whole network does not become a sectarian religion or cult. He recommends the expansion should be for the benefit of others, not mere expansion for the sake of expansion due to any blind belief -- but with the intention may more people benefit, rather than for the sake of your own organization's growth. Some homosexual individuals have been told that Goenka's Vipassana courses are not open to them unless they agree that their condition is an illness, and agree to use separate washroom facilities. It's possible even some meditators are still prejudiced, but another website says "A gay meditator has to follow the same rules as a straight meditator in order to be accepted to long courses (20, 30, 45, or 60-days) in this tradition". In fact, all participants of the meditation courses must agree to abstain from all sexual activity.[1] It might be nice to get a more official stance than merely speculating (and slandering). Some people with no previous history of mental illness have suffered severe neurological difficulties and periodic anxiety attacks as a result of attending Vipassana retreats. Through the application process, however, much effort is made to prepare potential students for the rigorous and serious nature of the intensive 10-day meditation.

From the Intro to the Technique: People with serious mental disorders have occasionally come to Vipassana courses with the unrealistic expectation that the technique will cure or alleviate their mental problems. Unstable interpersonal relationships and a history of various treatments can be additional factors which make it difficult for such people to benefit from, or even complete, a ten-day course. Our capacity as a nonprofessional volunteer organization makes it impossible for us to properly care for people with these backgrounds. Although Vipassana meditation is beneficial for most people, it is not a substitute for medical or psychiatric treatment and we do not recommend it for people with serious psychiatric disorders.

The organization of the centers are de-centralized and self-sufficient, and may be run by volunteers of varying experience, which may account for differences in attitudes and experiences. In an effort to provide a more uniform experience in all of the centers, all public instruction during the retreat is given by audio and video tapes of Goenka. When asked about problems related to growth and expansion, Goenka is quoted as:

The cause of the problem is included in the question. When these organizations work for their own expansion, they have already started rotting. The aim should be to increase other people’s benefits. Then there is a pure Dhamma volition and there is no chance of decay. When there is a Dhamma volition, "May more and more people benefit," there is no attachment. But if you want your organization to grow, there is attachment and that pollutes Dhamma.

Goenka argues, "The Buddha never taught a sectarian religion; he taught Dhamma - the way to liberation - which is universal."[2] Therefore, he views his own teachings as non-sectarian and open to people of all faiths or no faith. Goenka calls Vipassana meditation an experiential "scientific" practice. Students are encouraged to examine and test their own experience as evidence at the experiential level by observing oneself with equanimity, then see what the results are. The technique involves adherence to a moral code and the observation of breath. To quiet the mind, students are asked to have no contact with the outside world or other students, though may talk to an assistant teacher about questions concerning the technique or student manager for any material problems. Mere observation of breath allows the mind to become naturally concentrated. This concentration prepares one for the main part of the practice -- non-attached observation of the reality of the present moment as it manifests in one's own mind and body. After watching the breath for several days, a practice called Anapana, the course goes on to the Vipassana practice which involves carefully "scanning" the surface of the body with one's attention and observing the sensations with equanimity.

Goenka is a prolific orator, writer and a poet. He writes in English, Hindi and Rajasthani languages. He has traveled widely and lectured to audiences worldwide including at the World Economic Forum, Davos, in the year 2000 and at the “Millennium World Peace Summit” at the United Nations in August, 2000. For four months in 2002, he undertook the Meditation Now Tour of North America.

He believes that theory and practice should go hand-in-hand and accordingly has also established a Vipassana Research Institute to investigate and publish literature on vipassana and its effects.

Goenka has envisioned a magnificent, nearly 100-m tall, Global Pagoda to serve as an inspiration for spreading vipassana meditation around the world. The construction is still in progress.

The Vipassana Meditation Centers that he has helped to establish throughout the world offer 10-day courses that provide a thorough and guided introduction to the practice of Vipassana meditation. These courses are supported by voluntary donations of people who want to contribute for future courses. There are no charges for either the course or for the lodging and boarding during the course, but those who benefit and feel that this ball should keep rolling for the good of others tend to make a donation. For more information on attending such a course, visit http://www.dhamma.org."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S.N._Goenka. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-27]

Abb.: Einbandtitel

"Mahāsi Sayādaw (1904-1982) was a famous Burmese Buddhist monk and meditation master who had a significant impact on the teaching of Vipassana (Insight) meditation in the West and throughout Asia. In his style of practice, the meditator anchors the attention with the sensations of the rising and falling of the abdomen during breathing, observing carefully any other sensations or thoughts that call the attention. Brief Biography

The Mahāsi Sayādaw was born in 1904 in Seikkhun village in Upper Burma. He became a novice at age twelve, and ordained at age twenty with the name U Sobhana. Over the course decades of study, he passed the rigorous series of government examinations in the Theravāda Buddhist texts, gaining the newly-introduced Dhammācariya (dhamma teacher) degree in 1941.

In 1931, U Sobhana took leave from teaching scriptural studies in Moulmein (Mawlamyine; ေမာ္လမ္ရုိင္မ္ရုိ့), South Burma, and went to nearby Thaton to practice intensive Vipassana meditation under the Mingun Jetawun Sayādaw. This teacher had done his practice in the remote Sagaing Hills of Upper Burma, under the guidance of the Aletawya Sayādaw, a student of the renowned forest meditation master Thelon Sayādaw. U Sobhāna first taught Vipassana meditation in his home village in 1938, at a monastery named for its massive drum 'Mahāsi'. He became well-known in the region as the Mahāsi Sayādaw. In 1947, the then-Prime Minister of Burma, U Nu (Burmese: ဦးနု), invited the Mahāsi Sayādaw to be resident teacher at a newly established medition center in Yangon, which came to be called the Mahāsi Sāsana Yeiktha.

The Mahāsi Sayādaw was a questioner and final editor at the Sixth Buddhist Council on May 17, 1954. He helped establish meditation centers all over Burma as well as in Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand, and by 1972 the centers under his guidance had trained more than 700,000 meditators. In 1979, the Mahāsi Sayadaw travelled to the West, holding retreats in Vipassana meditation, at newly founded centers such as the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Barre, Massachusetts, U.S. In addition, meditators came from all over the world to practice at his center in Yangon. When the Mahāsi Sayādaw died on the 14th on August, 1982 following a massive stroke, thousands of devotees braved the torrential monsoon rains to pay their last respects.

PublicationsThe Mahāsi Sayādaw published nearly seventy volumes of Buddhist literature in Burmese, many of these transcribed from talks. He completed a Burmese translation of the Visuddhimagga, ("The Path of Purification") a lengthy treatise on meditation by the 5th century Indian Theravadin Buddhist commentator and scholar Buddhaghosa. He also wrote a monumental original volume entitled Manual of Vipassana Meditation. His English works include:

- Practical Vipassana Exercises

- Satipatthana Vipassana Meditation

- The Progress of Insight--an advanced talk on Vipassana

Publikationen online: http://www.aimwell.org/Books/Mahasi/mahasi.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-09]

Famous students

- Sayādaw U Paṇḍita (Panditārāma)

- Sayadaw U Jānaka (Chamyay)

- Sayadaw U Kuṇḍala (Saddhammaraṃsi)

- Sayadaw U Sīlānanda

- Anagarika Munindra

- Joseph Goldstein

- Rodney Smith

- Sharon Salzberg

- Rear Admiral E.H. Shattock

- Robert Duvo"

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahasi_Sayadaw. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-27]

Abb.: Nyanaponika, April 1991

[Bildquelle:

http://www.buddhistisches-haus.de/en/picturebook/mixed/mixed-old.html. --

Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

Siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Materialien zum Neobuddhismus. -- 2. International. -- 3. Die ersten europäischen Mönche und Versuche der Gründung eines Vihâra auf dem europäischen Festland. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/neobuddhismus/neobud0203.htm

"Nyanaponika Mahathera (* 21. Juli 1901 in Hanau; † 19. Oktober 1994 in Forest Hermitage, Kandy) wurde als Siegmund Feniger in Hanau geboren und war 57 Jahre lang buddhistischer Mönch in der Theravada-Tradition. Sein Wirken als buddhistischer Lehrer und Gelehrter, als Übersetzer und Autor buddhistischer Schriften und als Herausgeber und Vortragender haben ihn zu einer inspirierenden Gestalt für die Erneuerung des Buddhismus in Asien, insbesondere Sri Lanka gemacht. Seine Teilnahme am 6. Konzil in Rangun ist Beleg für die große Wertschätzung, die ihm in Asien entgegengebracht wurde. Darüber hinaus ist sein Wirken insbesondere für den Buddhismus in Deutschland und der Schweiz von großer Bedeutung. Leben

Siegmund Feniger wurde am 21. Juli 1901 als einziges Kind eines Ladenbesitzers in Hanau bei Frankfurt geboren. Siegmund genoss eine traditionelle jüdische Erziehung und war sehr an religiösen Dingen interessiert. Er begann im Buchhandel zu arbeiten und stieß dabei auf den Buddhismus. Nach der Übersiedlung der Familie nach Berlin 1922 kam er auch in Kontakt mit Buddhisten. So erfuhr er auch vom Ehrwürdigen Nyanatiloka, dem deutschen Mönch, der in Ceylon die „Island Hermitage“ gegründet hatte, eine Einsiedelei, die auch westlichen Mönchen offen stand. Angesichts des zunehmenden Rassenwahns in seiner Heimat emigrierte er 1935 nach Österreich, um 1936 schließlich seinen Plan, sich dem Ew. Nyanatiloka in Sri Lanka anzuschließen, zu verwirklichen. Noch im gleichen Jahr erhielt er die Novizenordination und im Jahr darauf wurde er zum vollordinierten Bhikkhu mit dem Namen Nyanaponika („zur Erkenntnis geneigt“).

Gemeinsam mit seinem Lehrer Nyanatiloka wurde er beim Ausbruch des Krieges von den Briten als „feindlicher Deutscher“ im Lager Diyatalawa interniert und später nach Nordindien ins Lager Dehra Dun [देहरादून] verlegt, wo er u. a. mit Heinrich Harrer und Lama Anagarika Govinda zusammentraf. Nyanaponika nutzte diese Zeit für Übersetzungen aus dem Pali-Kanon ins Deutsche. Nach Ende des Krieges konnte er 1946 in die Island Hermitage zurückkehren. Nachdem Ceylon 1948 von Großbritannien unabhängig geworden war, nahm Nyanaponika 1951 die Staatsbürgerschaft seiner Wahlheimat an. Gemeinsam mit seinem Lehrer übersiedelte er in das neue Meditationszentrum „Forest Hermitage“ in Kandy im Hochland von Sri Lanka.

Die Vorbereitungen auf das 6. Konzil in Burma brachten ihm die Gelegenheit, den Meditationsmeister Mahasi Sayadaw kennen zu lernen. Sein wohl bekanntestes Buch „Geistestraining durch Achtsamkeit“ spiegelt teilweise diese Erfahrungen wider.

1958 konnte Nyanaponika die Erfahrungen seines Ursprungsberufes nutzen, als er gebeten wurde, Leiter und Herausgeber der neu gegründeten BPS (Buddhist Publication Society) zu werden. Die BPS, die er bis 1984 leitete, wurde zu einem weltweit anerkannten Verlag für die Verbreitung der Theravada-Lehre.

Bei Reisen von den späten 60er bis in die frühen 80er Jahre, vornehmlich in die Schweiz, traf Nyanaponika mit vielen Persönlichkeiten des europäischen Buddhismus zusammen und wurde von ihnen auch in seiner Waldeinsiedelei besucht.

In den letzten Lebensjahren wurden ihm zahlreiche Ehrungen zuteil.

WerkÜbersetzungen von Nyanaponika

Schriften von Nyanaponika

- Gruppierte Sammlung (Samyutta Nikaya) Buch II (17-21) und das ganze Buch III (22-34). ISBN 3-931095-16-9

- Angereihte Sammlung (Anguttara Nikaya) Herausgabe und Überarbeitung der Übersetzung von Nyanatiloka. ISBN 3-59108218-X

- Der einzige Weg. Buddhistische Texte zur Geistesschulung in rechter Achtsamkeit. Aus dem Pâli und Sanskrit übersetzt und erläutert von Nyânaponika. ISBN 3-931095-04-5

Literatur über Nyanaponika

- Nyanaponika Mahathera: Geistestraining durch Achtsamkeit. 1970 (Besonders wertgeschätzt von Erich Fromm) ISBN 3-931095-02-9

- Nyanaponika Mahathera: Geistestraining durch Achtsamkeit. Freie Version im Internet

- Nyanaponika Mahathera: Im Lichte des Dhamma. 1989. Hrsg. Kurt Onken. ISBN 3-931095-01-0.

- Onken, Kurt (Hrsg.): Des Geistes Gleichmaß. Gedenkschrift zum 75. Geburtstag. Christiani 1976. ISBN 3-931095-48-7

- Onken, Kurt (Hrsg.): Zur Erkenntnis geneigt. Gedenkschrift zum 85. Geburtstag. Christiani 1986. ISBN 3-931095-07-X

- Scharlipp, Matthias Nyanacitta (Hrsg.): Ein edler Freund der Welt. Nyanaponika Mahathera (1901-1994) Gedenkschrift zum 100. Geburtstag. Jhana 2002. ISBN 3-931274-21-7."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nyanaponika. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-20]

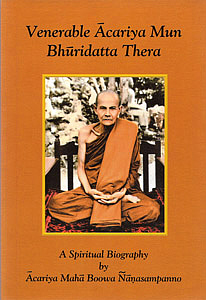

Abb.: Einbandtitel

"Ajaan Mun Bhuridatta Thera (Thai: มั่น ภูริทตฺโต), 1870-1949, was a Thai Buddhist monk who is credited with establishing the Kammatthana tradition of forest monks. Biography

Early yearsAjahn Mun was born on Thursday, January 20, 1870, in a farming village named Baan Kham Bong, Khong Jiam [โขงเจียม], on the western bank of the Mekong River, in present day Si Mueang Mai District [ศรีเมืองใหม่], Ubon Ratchathani Province [อุบลราชธาน] of northeastern Thailand (Isan). Khong Jiam is located in a triangle of land where the Mun River [แม่น้ำมูล] flows into the Mekong River, as the Mekong turns east and flows into Laos. He was born into the Lao-speaking family of Kanhaew with Nai Kamduang as his father and Nang Jan as his mother. He was the eldest of nine children: eight boys and one girl.

Mun was first ordained as a novice monk at age 16, in the local village monastery of Khambong. As a youth, he studied Buddhist teachings, history and folk legends in Khom, Khmer and Tham scripts from fragile palm leaf texts stored in the monastery library. He remained a novice for two years, until 1888, when it was necessary for him to leave the monastery, at his father's request.

Entering monkhoodAjahn Mun was fully ordained as a monk at age 22, on June 12, 1893, at Wat Liap monastery in the provincial city of Ubon Ratchatani. Venerable Phra Ariyakavi was his preceptor. His announcing teacher was Venerable Phra Kru Prajak Ubolguna. Mun was given the Buddhist name "Bhuridatta" (meaning "blessed with wisdom") at his ordination.

After ordination, Mun went to practice meditation with Phra Ajahn Sao Kantasilo of Wat Liap in Ubon, where he learned to practice the monastic traditions of Laos. Ajahn Sao taught Mun a mantra meditation method to calm the mind, the mental repetition of the word, "Buddho." Ajahn Sao often took Ajahn Mun wandering and camping in the dense forests along the Mekong River, where they would practice meditation together. This is known as "dhutanga" ("thudong" in Thai). One of the first long distance thudong was a pilgrimage to Wat Aranyawaksi in Thabor district, Nong Khai Province [หนองคาย]. At the time, Wat Aranyawaksi was a ruin, an abandoned, overgrown temple in the jungle. Ajahn Mun spent a year in "illumination" in the teak forest around the temple at this early part of his monastic life.

In 1899, Ajahn Mun was reordained in the Thammayut Nikaya, a reformed Thai sect which emphasized monastic disciple and scripture study. Having practiced under the guidance of his teacher for several years, and with his teachers blessings, Ajahn Mun went out on his own to search for advanced meditation teachers. During the next several years, he wandered extensively throughout Laos, Thailand and Burma, practicing meditaiton in secluded forests. Ajahn Mun and Ajahn Sao went on pilgrimage together in 1905 and venerated the Phra That Phanom shrine, a center of Theravada Buddhism for centuries, most sacred to the Lao people.

Thudong aloneAjahn Mun then wandered alone, onward to the north, to Sakhon Nakhon Province [สกลนคร] on the highlands of the northeastern plateau, inland from the Mekong River, into the Phu Phan Mountain Range [เทือกเขาภูพาน]. Today, a museum to Ajahn Mun is located here in the temple residence of Wat Pa Sutthavat, in the city of Nong Han Luang.

He then wandered on toward Udon Thani [อุดรธานี], into a region that was a wild forest filled with prehistoric caves. He continued his wandering pilgrimage deeper into the wildernesses of Loei [เลย], a land dreaded and feared by the Thai people, who describe it as "beyond" and "to the furthest extreme" of the world. This rugged wilderness along the Mekong consists of mountains, and extremes of weather, both cold and hot.

To BurmaIn 1911, Ajahn Mun decided to walk to Burma in search of a highly attained meditation teacher who could help him in his struggle for enlightenment. He walked by stages from northeast Thailand down to Bangkok [กรุงเทพฯ], through the wilderness mountain ranges.

He made his way into Burma and visited the Shwedagon Pagoda among other sites. During his stay in Burma, he did indeed make contact with meditation teachers who were capable of giving him the guidance he was seeking in order to develop the correct meditation practices that would lead to higher attainments. Unfortunately, the names of these meditation teachers were never recorded. Ajahn Mun spent the Rain Retreat of 1911 at Moulmein [ေမာ္လမ္ရုိင္မ္ရုိ့] in lower Burma, in the Mon states [မ္ဝန္ပ္ရည္နယ္]. He was deeply affected by the morality and generosity, and strong monastic discipline of the Mon [မ္ဝန္လူမ္ယုိး] and Shan [ရ္ဟမ္းလူမ္ယုိး] people he met in Burma.

Back to Central Thailand and IsanIn 1912, Ajahn Mun spent the Rains Retreat at Wat Sapathum (now known as Wat Pathum Wanaram) in Bangkok, where he received instructions and advice from His Eminence Phra Upali of Wat Boromnivasin [วัดบวรนิเวศวิหารราชวรวิหาร]. After Rains Retreat, he journeyed up to the town of Lopburi [ลพบุรี] and stayed in various caves such as Phaikwang Cave, Mount Khao Phra Ngarm, and Singho Cave, where he practiced intensive meditation.

In 1913, Ajahn Mun stayed in Sarika Cave at Great Mountain (Khao Yai [เขาใหญ่]) in Nakhon Nayok [นครนายก]. It was during this time, at age 43, when he attained anagami, according to the biography written by his disciple Luang Ta Maha Bua [หลวงตามหาบัว]. Ajahn Mun spent the next two or three years living at this location in the Khao Yai Mountains. He struggle with a mortal life-threatening illness during these years. A chapel shrine to Ajahn Mun is located at this cave today and is a major pilgrimage site.

In 1915, Ajahn Mun spent the Rain Retreat at Wat Sapathum in Bangkok, and frequently walked to a nearby temple to hear sermons by Ajahn Jan, an important high-ranking monk.

From here, Ajahn Mun returned to the rural districts of northeast Thailand. In 1918, he spent Rains Retreat in Wat Burapha, on the outskirts of Ubon city. He remained at the same monastery for the Rain Retreat of 1920. For the next five years he wandered throughout the northern districts of upper Isan [อีสาน] region: Sakhon Nakhon, Udon Thani, Nong Khai and Loei.

Ajahn Mun was increasily recognized as a highly gifted teacher during these years, and attracted growing numbers of disciples among both monks and laypeople. In 1926 he was accompanied by a group of 70 monks in a "thudong" south to Daeng Kokchang Village, Tha Uthen District, heading toward Ubon.

A controversy engulfed Ajahn Mun and his disciples at this time. The monastic authorities in Bangkok were in the process of imposing reforms intended to standardize and centralize the sangha, and were pressuring the wandering forest monks to settle down in temples and become "productive" members of society. Monastic administrators were suspicious of these apparently "vagrant" monks who lived in wild forests and jungles, beyond the realm of civilization. Ajahn Jan, the monastic administrator of the province, ordered the people to withhold support from the wandering monks. Several of Ajahn Mun's disciples were taken into custody by civil authorities under suspicion of vagrancy.

Ajahn Mun became increasingly concerned by the encroachments of modern ways that threatened the traditional monastic customs he had been trained in. He began to think of leaving his homeland in order to seek more remote regions beyond the reach of modernizing influences of Bangkok authorities.

In 1927, Mun was in Ubon teaching monks and laypeople in Wat Suthat, Wat Liap, and Wat Burapha. He made arrangements for his aging mother, and then took leave of his family to go wandering into the direction of the Central Plains region of Thailand, not certain of his destination. He wandered by stages across the barren lands and sparsely populated lands of central Isan, sleeping under the occasional shade tree, receiving alms food from the poor rice farmers along the way. When he reached the rugged, wild mountains and jungles of Dong Phaya Yen Forest [ดงพญาเย็น] between Sara Buri [สระบุรี] and Nakhon Ratchasima [นครราชสีมา] provinces, he rejoiced at the flora and fauna of nature.To Northern Thailand

In 1928 he spent Rains Retreat at Wat Burapha in Ubon. After Rains Retreat this year, he left northeast Thailand and didn't return again until the final years of his life. He went first to Bangkok, and then traveled north to Chiang Mai [เชียงใหม่] and Chiang Rai [เชียงราย] provinces, where he remained in meditation retreat for the next 12 years of his life.

He was acting abbot of Wat Chedi Luang [วัดเจดีย์หลวง] in Chang Mai during 1929, appointed under the direction of Bangkok authorities. When his superior, Phra Upali died this year, Ajahn Mun fled his temple without notifying either his dependent monks or the monastic authorities in Bangkok

The following years, Ajahn Mun established a meditation retreat on the eastern slope of Chiang Dao Mountain, and frequently spent time meditating in the sacred, remote Chiang Dao caves. Initially, he wandered through the Mae Rim district of Chiang Dao mountain range, staying in the forested mountains there through both the dry and the monsoon seasons that year.

Ajahn Mun was again in Wat Chedi Luang in Chiang Mai in 1933. From here he went wandering into Burma throughout the Karen and Shan states.

From 1932-1938, Ajahn Mun practiced meditation in a variety of locations throughout the forests and mountains, in solitude with little contact with people. These years of solitary retreat into the rugged, inaccessible wilderness are very significant in the biography of Ajahn Mun. According to his disciples, he is said to have attained enlightenment or "become an Arahant" during his time in retreat here among the hill tribes, in mountains that hold a unique position in the shamanistic traditions of Thailand.

He spent Rains Retreat of 1935 in Makkhao Field Village in Mae Pong District. In 1936 he spent the retreat near Puphaya Village among the hill tribes. Then the following year, he was in Mae Suai District, Chiang Rai, among the Laui tribes.

Back to IsanIn 1940, at age 70, Ajahn Mun began the return journey to his homeland of Isan in northeast Thailand, in response to the persistent urging of his senior disciples. He first traveled down to Bangkok, then northward to Korat. He lingered in vast mountain jungles of Nakhon Ratchasima, staying at Wat Pa Salawan.

When he arrived in Udon Thani late in the year of 1940, he stayed at the temple Wat Boghisamphon where his disciple Chao Khun Dhammachedi was presiding abbot. From there he went to Wat Non Niwet for Rains Retreat.

After the rains retreat of 1940 he went wandering in the countryside in the vicinity of Ban Nong Nam Khem village, revisiting the fimiliar landscapes of his youth. Even at the age of 70, he was still able to take care of himself and get around in the wild environments.

In 1941 he spent the Rains Retreat at Wat Nan Niwet monastery in Udon Thani. After rains he traveled to Sakhon Nakhon and first resided at Wat Suddhawat Monastery. He then moved to a small forest monastery named Pheu Pond Hermitage near the village of Ban Na Mon. Pheu Pond Hermitage was in a very remote forest, far into the wilderness, three or four hours walk from the nearest village. (It is today named Wat Pa Bhuridatta in honor of Ajahn Mun.)

Ajahn Sao, Mun's first teacher as a new monk, died in 1942. Ajahn Mun moved to reside even deeper into the forest. At age 75, Ajahn Mun decided to settle permanently at his Pheu Pond Hermitage in the deep forest, at the head of the Phu Phan Mountains [เทือกเขาภูพาน], near Sakhon Nakhon. Due to his failing strenth, he was unable to wander into the forests. Ajahn Mun passed away in 1948 at Wat Suddhavasa in Sakhon Nakhon Province. He attracted an enormous following of students and, together with his teacher Ajahn Sao, established the Thai Forest Tradition (the Kammatthana tradition) that subsequently spread throughout Thailand and to several countries abroad.

Forest meditationAjaan Mun's mode of practice was solitary and strict. He followed the Vinaya (monastic discipline) faithfully, and also observed many of what are known as the 13 classic dhutanga (ascetic) practices, such as living off almsfood, wearing robes made of cast-off rags, dwelling in the forest and eating only one meal a day. Searching out secluded places in the wilds of Thailand and Laos, he avoided the responsibilities of settled monastic life and spent long hours of the day and night in meditation. In spite of his reclusive nature, he attracted a large following of students willing to endure the hardships of forest life in order to study with him.

Further reading

- The Customs of the Noble Ones by Thanissaro Bhikkhu describes the Thai forest tradition started by Ajaan Mun. -- http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/thanissaro/customs.html. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

- Tiyavanich, Kamala, Forest Recollections

- Maha Boowa, Patipada: The Mode of Practice of Venerable Acariya Mun

- Acariya Maha Boowa: Venerable Acariya Mun Bhuridatta Thera, a Spiritual Biography. Wat Pa Baan Taad 2003, Baan Taad, Amphoe Muang, Udon Thani, 41000 Thailand (no ISBN, available at this address, or 4MB pdf-download here: http://www.forestdhammabooks.com/index.php?page=Books. -- Zugrif am 2006-12-10])"

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajahn_Mun_Bhuridatta. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

Abb.: Ajahn Chah

[Bildquelle:

http://www.dhammapala.ch/Dhp-Mitte.htm. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

"Ajahn Chah (* 17. Juni 1918 nahe Ubon Ratchathani [อุบลราชธานี], Thailand; † 16. Januar 1992) war ein theravada-buddhistischer Mönch der Kamatthana-Waldmönchs-Tradition. Ab den siebziger Jahren wuchs sein Ruf, ein ausgezeichneter Lehrer auch für westliche Theravada-Mönche zu sein, stetig an. Dies führte zu einer Reihe Gründungen von Klöstern in Europa, den USA, Australien und Neuseeland, die sich auf ihn berufen. Leben

Nach Abschluss der grundlegenden Schulbildung lebte er in den darauffolgenden drei Jahren als Novize, bevor er an den Bauernhof seiner Eltern zurückkehrte, um dort bei den anfallenden Arbeiten zu helfen. Im Alter von zwanzig Jahren entschied er sich dazu, das monastische Leben wieder aufzunehmen, und am 26. April 1939 empfing er Upasampada (die Bhikkhu-Ordination). Das frühe mönchische Leben Ajahn Chahs folgte einem traditionellen Muster des Studierens des buddhistischen Unterrichts und der Schriften-Sprache Pali. In seinem fünften Mönchs-Jahr wurde sein Vater ernsthaft krank und starb bald darauf - ein Ereignis, dass ihm die Vergänglichkeit und den Wert des menschlichen Lebens heftig vor Augen führte. Dies veranlasste ihn, über den wirklichen Sinn des Lebens tiefergehend zu kontemplieren. Obgleich er studiert hatte und eine gewisse Fähigkeit im Pali erworben hatte, schien er dem wirklichen Verständnis vom Ende des Leidens nicht nähergekommen zu sein. Ein tiefliegendes Gefühl der "Entzauberung" allgemeiner Zielsetzungen im Leben führte dazu, dass er seine traditionellen Studien abbrach und schließlich im Jahre 1946 eine Pilgerreise als wandernder Mönch antrat.

Zu Fuß wanderte er ca. 400 Kilometer nach Zentralthailand, schlief in den Wäldern auf seinem Weg und aß die Almosenspeise, die er in den naheliegenden Dörfern beim morgendlichen Pindabat (Almosengang) von den buddhistischen Bewohnern erhielt. In einem Kloster, dass den Vinaya (buddhistische Ordensregel) besonders sorgfältig übte, wurde ihm vom ehrwürdigen Ajahn Mun Bhuridatta berichtet, einem äußerst respektierten Meditationsmeister seiner Zeit. Voller Eifer, einen solch verwirklichten Lehrer zu treffen, kehrte Ajahn Chah in den Nordosten zurück, um Ajahn Mun aufzusuchen.

Zu diesem Zeitpunkt rang Ajahn Chah mit einem hartnäckigen spirituellen Problem. Er hatte die Schriften in all ihren Aspekten wie Tugend, Sammlung und Weisheit studiert (Sila, Samadhi und Panna). Aber dennoch erschien es ihm rätselhaft wie all diese Facetten wirklich in die Praxis umgesetzt werden könnten. Ajahn Mun erklärte ihm, dass - obgleich die Lehren des Buddha in der Tat umfangreich sind - sie dennoch in ihrem Herzen sich sehr einfach darstellen. „Wenn man in sich Achtsamkeit erweckt hat, und man dadurch erkannt hat, dass alles lediglich in unserem Geist entsteht und vergeht - genau dann hat man den wahren Kern der Praxis erreicht.“ Diese einleuchtende und direkte Schulung sollte ein Kernerlebnis für Ajahn Chah werden, auf das er oft in seinen eigenen Lehren immer wieder Bezug nehmen würde. Für ihn war nun klar, was er zu tun hatte.

Für die nächsten sieben Jahre übte Ajahn Chah in der Art und Weise der entsagenden Waldmönche, von hier nach dort wandernd, auf der Suche nach ruhigen und abgelegenen Orten um sich in die Meditationspraxis zu vertiefen. Er lebte in Dschungelgebieten zusammen mit Tigern und Cobras - eine ideale Umgebung um über den Tod und den grundlegenden Sinn des Lebens zu kontemplieren! Bei einer dieser Gelegenheiten meditierte er nachts an einem jener Verbrennungs-Orte, wo traditionellerweise die Thais ihre verstorbenen Angehörigen einäschern. Die aufkommende extreme Furcht vor diesem Ort bei Nacht, vor wilden Tieren und dem Tod-an-sich forderte er somit in sich heraus und überwand diese schließlich.

Gründung des Klosters Wat Pah Pong [วัดหนองป่าพง]Im Jahre 1954 wurde er zurück in sein Heimatdorf eingeladen. In einem von Malaria befallenen Wald namens „Pah Pong“ schlug er sein Lager auf. Trotz der Härten dieser schutzlosen Umgebung und der spärlichen Nahrung, sammelten sich allmählich immer mehr Schüler um ihn, die von seinem wachsenden, guten Ruf angezogen wurden. Das Waldkloster, das so um ihn herum entstand, wurde „Wat Pah Pong“ genannt. Auf dieselbe Weise sollten bald weitere Zweigklöster in ganz Thailand gegründet werden.

1967 kam ein amerikanischer Mönch nach Wat Pah Pong. Der ehrwürdige Sumedho hatte gerade sein erstes Regenzeit-Retreat (das „Vassa“ - eine dreimonatige Zeit des Rückzuges während der Regenzeit) in einem Kloster an der laotischen Grenze verbracht. Obgleich seine Bemühungen durchaus fruchtvoll gewesen waren, erkannte der ehrw. Sumedho, dass er einen Lehrer benötigte, der ihn in allen Aspekten des monastischen Lebens ausbilden konnte. Zufällig hatte einer von Ajahn Chahs Schülern das Kloster, in dem der ehrw. Sumedho zu diesem Zeitpunkt lebte, besucht - dieser konnte sogar ein wenig Englisch sprechen. Nachdem der ehrw. Sumedho also von Ajahn Chah gehört hatte, reiste er voller Interesse mit dem thailändischen Mönch nach Wat Pah Pong. Ajahn Chah nahm diesen neuen Schüler bei sich auf, aber beharrte darauf, dass dieser Westler keinerlei Sondervergütungen empfangen würde. Er aß die gleiche, einfache Almosenspeise wie die anderen thailändischen Mönche. Das Training dort war streng und äußerst fordernd. Ajahn Chah brachte seine Mönche häufig an deren Grenzen, um ihre Ausdauer zu überprüfen, damit diese Geduld und Gleichmut entwickeln würden. Manchmal veranlasste er lange und scheinbar sinnlose Arbeitsprojekte, um deren Anhaftung an Ruhe und Stille zu frustrieren. Das Hauptgewicht lag dabei immer besonders auf der genauen Befolgung des Vinaya.

Bald kamen weitere Westler nach Wat Pah Pong. Als der ehrw. Sumedho ein Bhikkhu von fünf Jahren war, erachtete Ajahn Chah ihn als kompetent genug um selbst zu unterrichten. So kam es, dass der ehrw. Sumedho und eine Handvoll westlicher Bhikkhus in der heißen Jahreszeit im Jahre 1975 in einem Wald nahe Wat Pah Pong ihre Lagerstatt aufschlugen, um auf Almosenschalen die schützende Glasierung zu brennen. Die Bewohner des nahegelegenen Dorfes Bung Wai erfuhren davon, und baten die Mönche in diesem Wald in ihrer Nähe dauerhaft zu bleiben. Ajahn Chah stimmte zu, und so wurde Wat Pah Nanachat („internationales Waldkloster“) gegründet. Der ehrw. Sumedho wurde der erste Abt dieses Waldklosters, in dem nun westliche Waldmönche auf Englisch unterrichtet werden sollten.

Gründung des Klosters Cittaviveka bei London1977 wurde Ajahn Chah zusammen mit Ajahn Sumedho nach Großbritannien von dem dortigen English Sangha Trust eingeladen - einer Laiengemeinschaft, die sich zum Zwecke der Etablierung eines Theravada-Sangha in England gebildet hatte. Ajahn Chah war von der aufrichtigen Wertschätzung der buddhistischen Lehre im Westen sehr beeindruckt. Er ließ Ajahn Sumedho mit Unterstützung von Ajahn Khemadhammo und zwei weiteren westlichen Mönche in London zurück, um dort das Dhamma zu lehren. 1979 kehrte Ajahn Chah nach Großbritannien zurück, als seine Schüler dort gerade das buddhistische Kloster in Chithurst, Sussex, begannen aufzubauen - Cittaviveka. Danach reiste er in die USA und Kanada, wohin er eingeladen worden war um zu unterrichten.

Nach dieser Reise verging Ajahn Chahs Gesundheit auf Grund der Auswirkungen seiner Diabetes Schritt für Schritt. Seinen sich verschlechternden Zustand, den geschwächten Körper nutzte er nun gegenüber seinen Schülern und der buddhistischen Bevölkerung als eine Unterrichtsmethode - er wurde nun selbst ein lebendes Beispiel für die Vergänglichkeit (Anicca) aller Dinge.

Er forderte seine Schüler beständig dazu auf, eine Zuflucht in sich selbst zu finden, da er bald nicht mehr dazu in der Lage sein würde, sie zu unterrichten. 1981 wurde er in Bangkok operiert, was jedoch wenig an seinem Zustand besserte. Innerhalb weniger Monate verlor er die Fähigkeit zu sprechen, sich zu bewegen bis er schließlich vollständig gelähmt und bettlägrig war. Von da an wurde er sorgfältig und liebevoll von seinen Schülern gepflegt, die ihm nun auf diese Weise dankbar ihre Ehrerbietung erwiesen, nachdem er über lange Jahre hinweg geduldig und mitfühlend das Dhamma gelehrt hatte. Erst zehn Jahre später, im Jahre 1992, verstarb Ajahn Chah.

Heute gibt es vier Zweigklöster Wat Pah Pongs in England, von denen Amaravati Buddhist Monastery, 50 km nördlich von London gelegen, das größte ist. Im Verlauf der letzten Jahre entstanden weitere Klöster im Westen: Dhammapala in der Schweiz, Santacittarama in Italien, Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery in Kalifornien, Aruna Ratanagiri (Harnham Buddhist Monastery) im Norden Englands, Bodhinyanarama in Neuseeland - um die wichtigsten zu nennen.

Bekannte westliche SchülerWerke

- Ehrw. Ajahn Sumedho: Abt des Amaravati Klosters in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire England

- Ehrw. Ajahn Khemadhammo: Abt des Waldklosters, Warwickshire, England

- Ehrw. Ajahn Munindo: Abt des Aruna Ratanagiri Klosters in Northumberland, England

- Ehrw. Ajahn Passano: Co-Abt des Abhayagiri Klosters in Redwood Valley, California, USA

- Ehrw. Ajahn Brahm: Spiritueller Leiter der Buddhist Society of Western Australian und Abt des Bodhinyana Klosters, Serpentine WA, Australia

- Ehrw. Ajahn Amaro: Co-Abt des Abhayagiri Klosters in Redwood Valley, California, USA

- Ehrw. Ajahn Sundara

- Joseph Kappel

- Jack Kornfield

- Paul Breiter

Weblinks

- Ein stiller Waldteich, Theseus, 1996 (Herausgeber Jack Kornfield, Paul Breiter; Vorwort Seung Sahn), ISBN 3896200798

- Food for the heart, Wisdom, 2002 (Herausgeber Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery, Einleitung Ajahn Amaro, Vorwort Jack Kornfield), ISBN 0-86171-323-0

- Being Dharma, Shambhala, 2001 (Herausgeber Paul Breiter, Vorwort Jack Kornfield

- Paul Breiter Venerable Father, A Life With Ajahn Chah. Buddhadhamma Foundation, Bangkok 1994, ISBN 974-89072-8-7 (Ein ehemaliger Mönch und Schüler von Ajahn Chah beschreibt seine Erinnerungen aus den Jahren 1971 - 1977, die er im Wat Pah Nanachat verbrachte.)

- http://www.forestsangha.org/. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10. -- Hauptportal der Forest Sangha, der Schülerschaft Ajahn Chahs und deren Klöster

- http://www.dhammapala.ch/ Dhammapala. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10. -- Deutschsprachiges Kloster der Ajahn Chah Tradition in Kandersteg, Schweiz."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajahn_Chah. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

"Buddhadasa Bhikkhu (Thai: พุทธทาสภิกขุ ausgesprochen: Put-ta-tahd Pik-ku, Geburtsname: Ngüam Panid; * 27. Mai 1906 in Phumrieng, Südthailand; † 25. Mai 1993 in Chaiya [ไชยา]) war einer der einflussreichsten buddhistischen Theravada-Mönche des 20. Jahrhunderts. Frühe Jahre

Abb.: BuddhadasaBuddhadasas ursprünglicher Name war Ngüam Panid, er wurde am 27. Mai 1906 als ältester von drei Kindern in eine kleine Kaufmanns-Familie in Phumrieng, einer kleinen Küstenstadt in der südthailändischen Provinz Surat Thani [สุราษฎร์ธาน], geboren. Sein Vater hieß Sieng Panid, er war chinesischer Abstammung. Seine thailändische Mutter hieß Kluan Panid, beide betrieben einen kleinen Krämerladen, in dem Ngüam seine Kindheit verbrachte. Seine Mutter war eine tiefgläubige Buddhistin, sie lehrte ihn Verantwortung und die Kunst der Sparsamkeit. Sie wurde später einer der Hauptsponsoren des Wat Suan Mohk. In ihrer Jugend veranstalteten Ngüam und seine Brüder in der Nachbarschaft Diskussionen über buddhistische Themen.

Im Jahre 1926 wurde er traditionsgemäß und auf Wunsch seiner Mutter im Wat Mai in Phumrieng zum Mönch ordiniert. Er bekam den Namen Inthapanyo (der Weise). Bereits nach drei Tagen begann er, sich von den althergebrachten Konventionen zu lösen: anstatt den Laien aus den alten Schriften vorzulesen, versuchte der junge Mönch das Dhamma mit alltäglichen Ereignissen zu verbinden. Seine Art zu predigen wurden bald im ganzen Land bekannt, so dass die Predigt-Halle bald nicht mehr die vielen Leute aufnehmen konnte, die kamen, um ihm zuzuhören.

Innerhalb von zwei Jahren bestand er die Prüfungen für die beiden Grundstufen des Dhamma-Studiums (Thai: Nak Tham Tri und Nak Tham Tho). Auf Anraten seines Onkels Siang aus Chumpon zog er nach Bangkok, da er nur dort das Studium der Schriften vertiefen konnte. Inthapanyo hielt Bangkok zunächst für das „Land der Erwachten“, das Zentrum der Schriften und Gurus. Aber er wurde sehr schnell desillusioniert durch den Lärm und Dreck der Stadt, die überfüllten Tempel und die desinteressierten Mönche. Schon nach zwei Monaten war er so frustriert, dass er beinahe aus dem Mönchsorden ausgetreten wäre. Er kehrte in sein Heimatdorf zurück, wo er sich alleine das Wissen für die letzte Grund-Stufe des Studiums der alten Schriften aus Büchern beibrachte. Nach einem Jahr konnte sein Onkel ihn erneut überreden, in Bangkok das Studium der Pali-Sprache aufzunehmen. Diesmal war Inthapanyo gelassener, er konnte sich in eine ruhige Ecke zurückziehen und bekam dort Privatunterricht. Bald absolvierte er die Prüfung für die dritte Grundstufe, und wurde so ein Phra Maha Parien (etwa: Pali-Gelehrter), wie er es sich gewünscht hatte.

Nach einem weiteren Jahr des Aufbau-Studiums, welches er aber nur halbherzig betrieb, fiel er durch die Prüfung, was ihn endgültig davon überzeugte, der Großstadt den Rücken zuzuwenden und nach Phumrieng zurückzukehren.

Gründung von Wat Suan MohkZu Zeiten des Buddha empfahl dieser seinen Schülern, in den Wald zu gehen und sich unter einen Baum zu setzen um die letzte Wahrheit zu suchen. Genau dies wollte Inthapanyo tun. Mit Hilfe seines Bruders und einiger befreundeter Mönche fand er einen seit 80 Jahren verlassenen Tempel im Dschungel, der Wat Trapangjik genannt wurde.

Hier ließ er sich eine kleine Hütte bauen und zog im Mai 1932 dort ein. Er nannte diesen Tempel Suan Mokkhabalarama (kurz Suan Mohk), was soviel wie „Garten der Befreiung“ bedeutet. Im gleichen Jahr, nur einen Monat später stürzten Militärs in einem gewaltlosen Putsch den König von Thailand und errichteten eine konstitutionelle Monarchie, welches Buddhadasa selbst als gutes Omen für seine Neugründung ansah.

In den ersten zwei Jahren im Suan Mohk hatte sich Inthapanyo einem Leben in völliger Abgeschiedenheit ergeben. Bis hin zu dem Punkt, dass sein Bruder seine tägliche Mahlzeit am Waldrand an einen Baum hängen musste, damit der Einsiedler keinem Menschen begegnete. Er verbrachte seine Zeit mit Meditation und dem Studium des Tipitaka, immer bestrebt, den Weg der Theravada-Waldmönche einzuhalten. Anhand der Tipitaka und eigenen praktischen Erfahrungen stellte er für die ernsthafte Meditation eine Schritt-für-Schritt-Anleitung zusammen, die er ins Thailändische übersetzte und „Folge den Fußspuren der Arahats“ nannte. Er veröffentlichte sie in dem Journal „Buddhasasana“ (Thai: Buddhismus), welches sein Bruder Dhammadasa herausgab, unter seinem neuen Namen „Buddhadasa“. Diesen Namen gab er sich in einem feierlichen Gelübde im August 1932: „Ich übergebe dieses Leben und diesen Körper dem Buddha. Ich bin ein Diener des Buddha, und der Buddha ist mein Gebieter. Daher werde ich fortan den Namen Buddhadasa (‚Diener des Buddha‘) tragen.“

In seinen späteren Jahren kamen viele ausländische Studenten in seinen Tempel, um seine Predigten zu hören und an 10-tägigen Retreats teilzunehmen. Er hielt auch viele Gespräche mit Gelehrten der christlichen Kirche und auch anderer Religionen, in denen er immer betonte, dass in den Grundaussagen eigentlich alle Religionen gleich seien. Kurz vor seinem Tod im Jahre 1993 richtete er das International Dhamma Hermitage Center in der Nähe seines Tempels ein, um Nicht-Thai-Studenten eine Möglichkeit zu geben, die Lehren Buddhas und die Vipassana-Meditation zu studieren.

Buddhadasa starb am 25. Mai 1993 nach einer Serie von Herzanfällen und Herzschlägen bei der Vorbereitung einer Rede, die er in 2 Tagen zu seinem Geburtstag halten wollte. Nachdem die Ärzte des berühmten Siriraj-Hospitals in Bangkok unter Protest seiner Freunde und Mitmönche wochenlang vergeblich versuchten, seine Gesundheit wiederherzustellen, konnten sie seinen physikalischen Tod am 8 Juli 1993 feststellen.

BibliographieBuddhadasa hat so viel geschrieben, dass damit fast ein ganzer Raum in der National-Bibliothek von Thailand gefüllt werden konnte. Zu seinen bekanntesten Büchern, die ins Deutsche übersetzt worden sind, gehören:

- Anapanasati - Die sanfte Heilung der spirituellen Krankheit, Verlag BGM, ISBN 3-8311-3271-2

- Das Kernholz des Bodhibaums, Verlag BGM, ISBN 3-8311-0028-4

Weitere wichtige Bücher, die als PDF-Dateien bei dhamma-dana.de gratis heruntergeladen werden können:

- Buddhismus verstehen und leben - ein „Handbuch für die Menschheit“ (engl. Titel „Handbook for Mankind“)

- Dhamma-Sozialismus (englischer Titel „Dhammic Socialism“)

- Der Weg zu vollkommener geistiger Gesundheit (englischer Titel: „Cure for spiritual Disease“)

- Dhamma-Prinzipien für kluge Leute (englischer Titel: „Buddha-Dhamma for Students“)

Ein weiteres wichtiges Buch ist bisher nur ins Englische übersetzt worden:

- Handbook For Mankind. Bei buddhanet.net kann dieses online gelesen werden, es kann dort aber auch als PDF heruntergeladen werden."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhadasa. -- Zugriff am 2006-12-10]

Achtsamkeit wurde inzwischen von verschiedenen Psychologen in ihre Programme eingebaut, z.B. als MBCT:

"Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) is a blend of theory. Cognitive therapy is blended with a mindfulness aspect that helps clients understand that thoughts are not permanent. The client is urged to accept undesired feelings as they come and go instead of trying to push them away. Traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) focuses on changing negative content of thoughts while MBCT changes the thoughts and emphasizes on the process of negative thoughts. Changing the patient's relationship to the suffering caused by negative thoughts is the key because there is no possible way to alleviate all suffering. No therapy or meditation will prevent unpleasant things from happening in our daily lives but the two practices combined may provide more objectivity from which to view these unpleasant things.

MBCT's main technique is based on the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) eight week program, developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn in 1979 at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center. Research shows that MBSR is enormously empowering for patients with chronic pain, hypertension, heart disease, cancer, and gastrointestinal disorders, as well as for psychological problems such as anxiety and panic. People often misunderstand the goal of therapy and especially mindfulness. Relaxation and happiness are not the aim, but rather a "freedom from the tendency to get drawn into automatic reactions to thoughts, feelings, and events" (Segal, Teasdale, Williams, 2002). Patients change the relationship to chronic pain so the pain becomes more manageable.

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy grew largely from Jon Kabat-Zinn's work. Zindel V. Segal, J. Mark G. Williams and John D. Teasdale helped adapt the MBSR program so it could be used with people who had suffered repeated bouts of depression in their lives. Currently, MBCT programs usually consist of eight-weekly two and a half hour sessions in a group setting with weekly assingments to be done outside of session. The aim of this program is to enhance awareness so we are able to respond to things instead of react to them. "We can respond to situations with choice rather than reacting automatically. We do that by practicing to become more aware of where our attention is, and deliberately changing the focus of attention, over and over again" (Segal, et al., 2002, p. 122). The structure of MBCT requires strong commitment and work on the clients' part but the client's rewards can be lasting.

Effectiveness of MBCTResearch in now showing the effectiveness of mindfulness in the prevention of relapse. The UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) has recently endorsed MBCT as an effective treatment for prevention of relapse. Research has shown that people who have been clinically depressed three or more times (sometimes for twenty years or more) find that taking the program and learning these skills helps to reduce considerably their chances that depression will return. In a study conducted with 145 participants, all the patients had previously recovered from depression and then relapsed. These sufferers were split randomly into groups providing different methods of treatment. Within a year, patients who were undergoing MBCT "reduced relapse from 66% (control group) to 37% (treatment group)" Centre for Mindfulness Research. "Whereas most people might be able to ignore sad mood, in previously depressed persons a slight lowering of mood might bring about a potentially devastating change in thought patterns" (Segal, et al., 2002, p.29). The core skill of MBCT is to teach the ideas of recognizing these thought patterns in order to break away from the false constructs of our mind. Relapse is avoided because the onset of depression is recognized before it has fully developed. The vicious cycle is stopped before it even gets started.

Benefits of MBCT and mindfulness practiceMindfulness meditation is a useful tool in dealing with a couple of different scenerios. Practicing mindfulness aids patients, laypersons, and therapists. This approach to meditation focuses our attention back to the present, to what is happening right now in this exact moment. When one is mindful, the attention is focused on the present so judgment cannot be placed. Often, our pain and mental discomfort are caused by the judgment placed on the present moment and not by what is actually happening. This judgment and negative thinking is what can possibly lead to depression. MBCT prioritizes learning how to pay attention or concentrate with purpose, in each moment and most importantly, without judgment (Fulton, Germer, Siegel, 2005).

Segal and his partners found that "thoughts and feelings could interact with each other in a damaging, vicious spiral" (Segal, et al., 2002). Through the practice of mindfulness, we recognize that holding onto some of these feelings is ineffective and mentally destructive. Viewing things mindfully requires not turning away from any feeling but instead being open to the experience while trying not to engage defense mechanisms. All thoughts are welcomed into the mind equally so that one does not judge the thought or herself for thinking the thought. Gaining perspective on one's own thoughts allows us to escape the mental grooves and ruminative thinking that plagues us. Through mindfulness practice the spiral of negative thought is stopped before one finds herself at the bottom looking up.

Not only is this practice helpful to laypersons but to the actual therapist doing this type of MBCT. As a therapist, mindfulness can be implemented into therapy sessions, and used as a means of self-care in the therapist's personal life. "Meditating therapists often report feeling more 'present', relaxed, and receptive with their patients if they meditate earlier in the day" (Fulton, Germer, Siegel, 2005, p.18). Mindfulness incorporates not judging thought. By having that non-judgment, the therapist allows the patient to fully express true feelings by having that openness. "As the therapist learns to disentangle from her own conditioned patterns of thoughts that arise in the therapy relationship, the patient may discover the same emotional freedom" (Fulton, et al., 2005). The concentration development from mindfulness also helps the therapist be able to stay fully engaged with the patient. The mind naturally wanders to other things but mindfulness is the answer to being unfocused. There is a degree of perspective that also comes with mindfulness meditation. This new perspective allows a therapist to see other solutions or options to a patient's problem he or she may not have been originally aware of. "Having this [perspective] enables the therapist to have some flexibility in finding a formulation that accords with the patient's understanding" (Fulton, et al., 2005). As therapists help their patients come to these solutions and become more fully functioning, it may be easy to think they are powerful and all knowing. Maintaining perspective prevents therapists from 'buying their own press'.

As means of self-care, P. Fulton and his fellow authors would say "offering love and care to ourselves replenishes the physical and emotional reservoirs that are necessary to care for others" (p. 87). When looking at burn-out rates in the social service fields, one can see that self-care is absolutely necessary whether one thinks they need it or not. Meditating saturates these reservoirs so compassionate, sincere work can continue. Also by dealing with personal suffering through this practice, therapists develop greater empathy and become more openhearted to the needs of their clients.

Depression as the inspiration of MBCTDepression is a more serious problem than how it is presently seen. The World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a study and came up with the following projection for the year 2020: "of all diseases, depression will impose the second largest burden of ill health worldwide" (Segal, et al., 2002). Research shows that at any given time, ten percent of the United States has experienced this type of clinical depression in the last year alone (Segal, et al., 2002). Women being affected at a significantly higher rate (20-25%) than men (7-12%) (Segal, et al., 2002). The people who are affected with this comon mental disorder are also the least likely to get help or treatment.

Depression is a severe and prolonged state of mind in which normal sadness grows into a painful state of hopelessness, listlessness, lack of motivation, and fatigue. Depression can vary from mild to severe. When depression is mild, one may find himself brooding on negative aspects of himself or others. He may feel resentful, irritable or angry much of the time, feeling sorry for himself, and needing reassurance from someone. Various physical ailments could also occur that have no correlation to physical illness.

Depression is clasified as clinical when the episode inhibits a person's ability to accomplish routine daily tasks for at least two weeks. If suddenly 'normal' activities become difficult to do or the interest to do them is lost completely for a sustained amount of time, clinical depression could be a possibility. A change in basic bodily functions may also be experienced. The usual daily rhythms seem to go 'out of kilter'. One can't sleep, or one sleeps too much. One can't eat, or one eats too much. Others may notice that the sufferer may become agitated or slowed down. One may find that required energy for activities that used to be enjoyed is now gone. He or she may even feel that life is not worth living, and begin to develop thoughts that he or she would be better off dead.

Currently the most commonly used treatment for major depression is antidepressant medication. These medications are relatively cheap, and easy for family practitioners (who treat the majority of depressed people) to prescribe. However, once the episode has past, and the client has stopped taking the antidepressants, depression tends to return, and at least 50% of those experiencing their first episode of depression find that depression comes back, despite appearing to have made a full recovery. After a second or third episode, the risk of recurrence rises to between 80% and 90%. Also, those who first became depressed before 20 years of age are particularly likely to suffer a higher risk of relapse and recurrence.

The main method for preventing this recurrence is the continuation of the medication, but many people do not want to stay on medication for indefinite periods, and when the medication stops, the risk of becoming depressed again returns. People are turning to new ways of helping them stay well after depression. To see what it is most helpful to do, we need to understand why it is that we may remain at high risk, even when we've recovered. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy seems to be a complementary method to treating acute and chronic depression.

Why do we remain vulnerable to depression?New research shows that during any episode of depression, negative mood occurs alongside negative thinking (such as 'I am a failure', 'I am inadequate, 'I am worthless') and bodily sensations of sluggishness and fatigue. When the episode is past, and the mood has returned to normal, the negative thinking and fatigue tend to disappear as well. However, during the episode a connection has formed between the mood that was present at that time, and the negative thinking patterns.

This means that when negative mood happens again (for any reason) a relatively small amount of such mood can trigger or reactivate the old thinking pattern. Once again, people start to think they have failed, or are inadequate - even if it is not relevant to the current situation. People who believed they had recovered may find themselves feeling 'back to square one'. They end up inside a rumination loop that constantly asks 'what has gone wrong?', 'why is this happening to me?', 'where will it all end?' Such rumination feels as if it ought to help find an answer, but it only succeeds in prolonging and deepening the mood spiral. When this happens, the old habits of negative thinking will start up again, negative thinking gets into the same rut, and a full-blown episode of depression may be the result.

The discovery that, even when people feel well, the link between negative moods and negative thoughts remains ready to be re-activated, is of enormous importance. It means that sustaining recovery from such depression depends on learning how to keep mild states of depression from spiralling out of control.

Future of MBCTFurther research is being conducted to identify all the different uses of MBCT. Significant decreases in anxiety, depression, and well being have been found so far. Research being conducted will evaluate MBCT as a useful technique with patients who are diagnosed with cancer ore haematological illness. Mindfulness practice is being done over various cultures and demographics."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mindfulness-based_Cognitive_Therapy. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-27]

Am bekanntesten von solchen Psychologen ist Jon Kabat-Zinn.

Abb.: Audio-CD-Hülle (links: J. Kabat-Zinn)

"Jon Kabat-Zinn (born June 5, 1944) is Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. He teaches mindfulness meditation as a technique to help people cope with stress, anxiety, pain and illness. His life work has been largely dedicated to bringing mindfulness into the mainstream of medicine and society. Kabat-Zinn is the author or co-author of scientific papers on mindfulness and its clinical applications. He has written two bestselling books:

- Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness (Delta, 1991), and

- Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life (Hyperion, 1994).

He co-authored with Myla Kabat-Zinn

- Everyday Blessings: The Inner Work of Mindful Parenting (Hyperion, 1997).

His most recent book is

Coming to Our Senses (Hyperion, 2005).

Kabat-Zinn is the founder and former Executive Director of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. He is also the founder (1979) and former director of its renowned Stress Reduction Clinic and Professor of Medicine emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.