Zitierweise / cite as:

Somadeva <11. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Kathāsaritsāgara : der Ozean der Erzählungsströme : ausgewählte Erzählungen / übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer. -- 4. Buch I, Welle 3. -- 1. Vers 1 - 26: Die Geschichte von der Gründung der Stadt Pāṭaliputra (I). -- Fassung vom 2008-10-30. -- http://www.payer.de/somadeva/soma041.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2006-11-16

Überarbeitungen: 2008-10-30 [Verbesserungen]; 2008-10-15 [Verbesserungen]; 2008-09-18 [Verbesserungen und Ergänzungen]; 2007-01-09 [Verbesserungen]; 2006-12-21 [Verbesserungen und Ergänzungen]; 2006-11-19 [Ergänzungen]

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung WS 2006/07; HS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Der Sanskrit-Text folgt im Wesentlichen folgender Ausgabe:

Somadevabhaṭṭa <11. Jhdt.>: Kathāsaritsāra / ed. by Durgāprasād and Kāśīnāth Pāṇḍurāṅg Parab. -- 4. ed. / revised by Wāsudev Laxman Śāstrī Paṇśikar. -- Bombay : Nirnaya-Sagar Press, 1930, -- 597 S. -- [in Devanāgarī]

Die Verse sind, wenn nichts anderes vermerkt ist, im Versmaß Śloka abgefasst.

Definition des Śloka in einem Śloka:

śloke ṣaṣṭhaṃ guru jñeyaṃ

sarvatra laghu pañcamam

dvicatuṣpādayor hrasvaṃ

saptamaṃ dīrgham anyayoḥ

"Im Śloka ist die sechste Silbe eines Pāda schwer, die fünfte in allen Pādas leicht

Die siebte Silbe ist im zweiten und vierten Pāda kurz, lang in den beiden anderen."

Das metrische Schema ist also:

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉ ̽

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ ̽

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉˉ ̽

̽ ̽ ̽ ̽ ˘ˉ˘ ̽

Zur Metrik siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Einführung in die Exegese von Sanskrittexten : Skript. -- Kap. 8: Die eigentliche Exegese, Teil II: Zu einzelnen Fragestellungen synchronen Verstehens. -- Anhang B: Zur Metrik von Sanskrittexten. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/exegese/exeg08b.htm

Der von großen Dichter, dem Ehrwürdigen Gelehrten Somadeva verfasste Ozean der Erzählungsströme

Kommentar:

Zu Autor und Werk siehe:

Somadeva <11. Jhdt. n. Chr.>: Kathāsaritsāgara : der Ozean der Erzählungsströme : ausgewählte Erzählungen / übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer. -- 1. Einleitung. -- http://www.payer.de/somadeva/soma01.htm

evam uktvā vararuciḥ

śṛṇvaty ekāgramānase |

kāṇabhūtau vane tatra

punar evedam abravīt |1|

1. So sprach Vararuci, während Kāṇabhūti aufmerksam zuhörte. Da erzählte Vararuci dort im Wald weiters dies:

Erläuterung:

Beachten Sie die Vipulāform in a: ˉ˘ˉˉ ˘˘˘ˉ. Der Autor bezweckt mit dieser Unregelmäßigkeit vermutlich, die Aufmerksamkeit des Hörers für die folgende Geschichte zu wecken.

kadācid yāti kāle 'tha

kṛte svādhyāyakarmaṇi |

iti varṣa upādhyāyaḥ

pṛṣṭo 'smābhiḥ kṛtāhnikaḥ |2|

2. Die Zeit verging. Als wir einstmals unsere Aufgabe im Vedastudium1 beendet hatten und unser Lehrer Varṣa seine täglichen Pflichten2 erfüllt hatte, fragten wir ihn:

Kommentar:

1 Aufgabe im Vedastudium

"§ 27. Adhyayana. Studium (s. Weber, ISt. 10, 131 ff.). — Über den Umfang des Studiums findet sich eine Vorschrift bei Pāraskara 2, 6, 5 ff, der vidhi, vidheya und tarka unterscheidet; d. h. nach dem Komm. Vorschrift (Aussprüche des Brāhmaṇa über die Handlungen), Anwendung (Sprüche und Verse), Erörterung (der Bedeutung der Riten und Texte). Nach »einigen« soll der Veda mit seinen Anhängen (aṅga's) studiret werden (6); jedenfalls aber nicht nur der Kalpa (Ritual) (7). Vaikhānasa 2, 12 nennt vedān, vedau vedam vā sūtrasahitam.

Art des Studiums. — Das Studium, beginnt täglich nach Sonnenaufgang (Śaṅkhāyana 2, 9. 10, 1; Khādira 3, 2, 22 prātar); Śaṅkhāyana gibt in einem (nach Speyer) eingeschobenen Kap., 2, 7 ff. nähere Auskunft über die Art des Studiums. Unter Angabe des Ṛṣi, von welchem jeder Mantra herstammt, der Gottheit und des Metrums soll er auf jedesmaliges Ansuchen des Schülers hin jeden Spruch vortragen (2, 7, 18). Sie lassen nördlich vom Feuer sich nieder; der Lehrer mit dem Gesicht nach O., der Schüler nach W. (cf. noch Śaṅkhāyana 4, 8, 2 und Āśvalāyana 3, 5, n). Unter bestimmt vorgeschriebenen Zeremonien spricht dieser: »die Sāvitrī trage vor, Herr!« Lehrer: »die Sāvitrī trage ich dir vor« (Śaṅkhāyana 54). Schüler: »die Gāyatrī trage vor«, »die Viśvāmitrastrophe trage vor«; er wiederholt seine Bitte mit Bezug auf »die Ṛṣi's«, »Gottheiten«, »Metra«, »Śruti«, »Smṛti«, »Sraddhāmedhe«. Wenn der Lehrer selbst Ṛṣi, Gottheit, Metrum nicht weiß, so sagt er die Sāvitrī her.

In dieser Weise lehrt er

- jeden einzelnen Ṛṣi oder

- jeden der (85) Anuvāka's, bei den Kṣudrasūkta's (ṚV. 10, 129—131) gleich den ganzen Anuvāka oder

- soviel dem Guru beliebt,

- oder nach Belieben die erste und letzte Hymne jedes Ṛṣi

- oder Anuvāka, oder

- je einen Vers vom Anfang einer Hymne. »Am Anfang einer Hymne sagt der Lehrer, wenn er will: das ist der Beginn!«

Śaṅkhāyana's Vorschrift bezieht sich auf den ṚV.; bei den andern Veden ändert sich natürlich der Unterrichtsstoff. Pāraskara 2, 10, 18 ff. spricht von den Anfängen »der Ṛṣi's« für die Bahvṛca's, den Parvan's für die Chandoga's und den Sūkta's für die Atharvan's, während er mit den »Adhyāyaanfängen« (18) wahrscheinlich die Śākhā seiner Schule meint.

Aus Hiraṇyakeśin 1, 8, 16 wäre noch zu verzeichnen, dass bei Beginn und Beendigung der Kāṇḍa's resp. des Kāṇḍavrata (cf. Komm.) eine Spende Sadasaspati, eine dem Ṛṣi des Kāṇḍa gebracht wird, worauf andere, an Varuṇa u. s. w. folgen (cf. noch Āpastamba 8, 1). Nach Śaṅkhāyana 2, 7, 28 nimmt (der Lehrer) am Ende der Lektion Kuśaschösslinge, macht aus Kuhdünger an deren Wurzel eine Grube und gießt für jedes Lied Wasser auf die Kuśahalme. Pāraskara 3, 16 finden wir Sprüche, die jedesmal nach dem Studium (nach der Kārikā Tag für Tag) um das Vergessen abzuwenden, herzusagen sind: »Geschickt sei mein Mund, meine Zunge sei süße Rede u. s. w.«

§ 28. Verhalten des Schülers beim Lernen. — Nach Śaṅkhāyana 4, 8, 5 ff. soll er in der Nähe des Guru nicht auf einem erhöhten, nicht auf demselben Sitze sitzen, seine Füße nicht ausstrecken u. s. w. Der Schüler sagt »adhīhi bho!«; »om!« heißt ihn dann der Lehrer sagen und es folgt das Studium, an dessen Ende der Schüler die Füße des Lehrers umfasst und sagt »wir sind zu Ende Herr!« oder (nach einigen) »Entlassung« oder »Jetzt Pause.« Darauf geht er seinen Bedürfnissen nach. Während des Lernens darf niemand dazwischen treten; begeht er einen Fehler, so muss er drei Tage und Nächte oder 24 Stunden fasten, die Sāvitrī solange er kann wiederholen, den Brahmanen etwas schenken, und nach einer eintägigen Pause geht das Studium weiter.

§ 29. Vrata's. — Einzelne Gṛhyasūtren erwähnen verschiedene Gelübde, die das Studium der verschiedenen Teile des Veda einleiten (Śaṅkhāyana 2, 11. 12; Gobhila 3, 2; Oldenberg, Ind. Stud. 15, 139. 140. SBE. 29, 78. 79). Jedem von ihnen geht, wie bei der Sāvitrī ein Upanayana, voraus und folgt eine Uddīkṣaṇikā, das Aufgeben der Dīkṣā, wobei der Lehrer an den Schüler verschiedene Fragen hinsichtlich der Observanz richtet. Außer dem die Sāvitrī einleitenden Sāvitra-vrata (s. oben S. 53) bei dem die Observanz ein Jahr, oder drei Tage dauern kann, kennt Śaṅkhāyana vier weitere (cf. Komm. zu ,2, 4, 2 ff.), das Sukriyavrata, das das Studium des Ṛgveda einleitet, die Śākvara-, Vrātika-, und Aupaniṣadavrata's, die dem Studium der Mahānāmnī, des Mahāvrata resp. der Upaniṣad vorausgehen. Das Śukriya dauert drei oder zwölf Tage oder ein Jahr oder solange als der Guru für gut hält, die andern drei je ein Jahr.

Während des nördlichen Laufes der Sonne in der lichten Monatshälfte mit Ausnahme des vierzehnten oder achten Tages, nach einigen auch des ersten und letzten Tages, oder an einem andern von den Sternen gebotenen Tage, soll der Lehrer, nachdem er selbst durch 24 Stunden Enthaltsamkeit geübt hat, den Schüler zum Brahmacarya für das Śukriyagelübde auffordern. Sāmbavyagṛhya gibt Rede und Gegenrede an: »Sei ein Śukriyabrahmacārin«, »ich will ein Śukriyabrahmacārin sein.« Wenn die Zeit vorüber, das Gelübde erfüllt und der Ṛgveda zu Ende studiert ist, folgen die Rahasya's (Śākvara, Mahāvrata, Upaniṣad.). Bei Śaṅkhāyana stehen (2, 12) hierfür einige Vorschriften, die nach den Kommentaren auch für das Śukriya gelten, von Oldenberg im Anschluss an den Komm. zum Śāmbavyagrhya nur auf die Vrata's für die Geheimlehren bezogen werden. Der Lehrer fragt am Ende des Vrata (Uddīkṣaṇikā) den Schüler: »Bist du vor Agni, Indra, Āditya und den Visve devāḥ (denen er beim Upanayana, cf. p. 53, übergeben wurde) in Enthaltsamkeit gewandelt?« »Ja, Herr!« Darauf umhüllt er den Kopf des Schülers dreimal mit einem frischen Gewande, ordnet dabei den Saum so, dass es nicht herabfallen kann und heißt ihn drei Tage lang schweigend, aufmerksam, in einem Walde, einem Tempel oder Agnihotraplatz fasten, ohne seine Holzscheite anzulegen, zu betteln, auf der Erde zu schlafen, dem Lehrer Gehorsam zu leisten. Einige schreiben diese Beschränkungen nur für eine Nacht vor. Der Lehrer enthält sich des Fleischgenusses und Geschlechtsverkehrs. Nach Verlauf der Zeit geht der Schüler aus dem Dorf und muss vermeiden, gewisse Dinge, die sein Studium verhindern (z. B. rohes Fleisch, eine Wöchnerin, Verstümmelte u. s. w.) anzusehen. Der Lehrer geht nach NO. hinaus, lässt sich an einer reinen Stätte nieder und nach Sonnenaufgang trägt er dem Schüler, der mit einem Turban bekleidet schweigend dasitzt, nach der für das Studium vorgeschriebenen Weise (s. oben) die Geheimlehren vor. Das gilt für die Mahānāmnīverse (Ait. Ar. IV), während bei den andern Texten der Schüler nur zuhört, wenn der Lehrer die Lesung für sich selbst vornimmt. Der Lohn dafür sind die Kopfbinde, ein Gefäß, eine Kuh. Genauere Angaben in Bezug auf das Studium des Āraṇyaka (unter teilweiser Wiederholung des 2, 12 schon gesagten) enthält Śaṅkhāyana Buch VI, das wahrscheinlich ein späterer Zusatz ist. Ausführlich über die Vrata's handelt auch Gobhila III, 1—2 (und Khādira 2, 5, 17 ff.). Gobhila nennt das godānika, vrātika, ādityavrata (das einige nicht begehen) aupaniṣada-, jyaiṣṭhasāmika- und maḥānāmnīgelübde, über deren Zusammenhang mit den Vedatexten man den Komm, zu 3, 1, 28 vergleiche. Diese Gelübde unterscheiden sich teilweise in ihren Observanzen. Diejenigen z. B., welche das Ādityavrata begehen, suchen vor der Sonne nur unter Bäumen und Hütten Schutz, nirgend sonst, und steigen (außer, wenn sie vom Guru angewiesen werden) nicht übers Knie ins Wasser. Jyeṣṭhasāman- und Mahānāmnīgelübde sind z. T. gleich, doch ist der Anhänger des ersteren gezwungen, Śūdrafrauen zu meiden, kein Vogelfleisch zu essen u. s. w. Am ausführlichsten charakterisiert Gobhila das Mahānāmnīgelübde. Während jene je ein Jahr beanspruchen, dauert dieses 12, 9, 6, 3 Jahre, doch genügt nach einigen auch nur eins; das Gelübde ist dann strenger und nur dann in dieser Kürze erlaubt, wenn die Mahānāmnī's schon von Vorfahren studiert wurden. Das Mahānāmnī- oder auch Śākvaravrata scheint sehr populär gewesen zu sein; das beweist ein Zitat aus dem Raurukibrāhmaṇa bei Gobhila (3, 2, 7): »zu ihren Knaben sprechen die Mütter beim Säugen: das Śakvarīgelübde, o Söhnchen, möget ihr einst erfüllen!« Das Gelübde hat deutliche Beziehung auf Wasser und Regenzeit; wie die einzelnen Sprüche und interessanten Zeremonien Gobhila 3, 2, 10 ff. zeigen. Ist das erste Drittel dieses Gelübdes erfüllt, so lässt er für ihn den ersten Stotravers nachsingen, beim zweiten und letzten Drittel den zweiten resp. dritten Vers oder alle am Schluss des Ganzen. Der Schüler soll dazu gefastet und seine Augen geschlossen haben. Vaikhānasa widmet den pārāyaṇavratāni die Kapitel 2, 9—11, in denen er die sāvitīJ-, prājāpatya-, saumya-, āgneyavrata u. s. w. erwähnt. Keśava zu Kauś. 42, 12 ff. spricht von »veda-, kalpa-, mrgāra-, viṣāsahi-, yama-, śiro-, aṅgirovrata u. s. w.«; die Atharvapaddhati hat ein Kapitel über vedavrata's (cf. Bloomfield zu 57, 32 und JAOS. 11, 376). Eine allgemeine Vorschrift über den caritavrata, den Schüler, der sein Gelübde erfüllt hat, gibt Āśvalāyana 1, 22, 20. Hiernach ist damit eine »Einsichtserzeugung« verbunden. In einer nicht verbotenen Himmelsgegend geht sie vor sich. Der Schüler nimmt einen Palāśazweig mit einer Wurzel oder ein Kuśabüschel in die Hand und gießt dreimal Wasser von links nach rechts, mit einem auf seine Befähigung bezüglichen Spruch: (»wie du der Götter und des Opfers Schatzhüter bist, so möge ich der Menschen und des Veda Schatzhüter werden«) herum."[Quelle: Hillebrandt, Alfred <1853 - 1927>: Ritual-Litteratur, vedische Opfer und Zauber. -- Strassburg : Trübner, 1897. - 199 S. -- (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; III. Band, 2. Heft). -- S. 55 - 58]

§ 26. Die Pflichten des Schülers gehen aus der eben erwähnten Einweisungsformel hervor. Śaṅkhāyana. sagt 2, 6, 8, dass die ständigen Pflichten des Schülers im

- täglichen Anlegen von Brennholz (a),

- Bettelgang (b),

- Schlafen auf dem Boden (c) und

- Gehorsam gegen den Lehrer (d)

bestünden. Gobhila 3, 1, 27 bezeichnet Gürteltragen, Bettelgang, Tragen des Stockes, Holzanlegen, Wasserberühren (d. h. Morgen- und Abendwaschung) und die morgendlichen Begrüßungen als »nityadharma's«, cf. auch Pāraskara 2, 5, 11.

- Zu a) finden wir Śaṅkhāyana 2, 10, 1; Pāraskara 2, 4, 1 ff.; Āpastamba II, 23 (vgl. Āśvalāyana 1, 22, 5) genauere Vorschriften. Das Holz wird stets aus einem Walde geholt (Āpastamba II, 24) und zwar zuerst für das Upanayana-, später auch für das andere Feuer (Āpastamba 11, 22. 23). Es soll geschehen nach Pāraskara 2, 5, 9 »ohne Bäume zu schädigen«, also nur abgefallenes Holz sein. Anlegen und Verehrung des Feuers, Umfegen und Umsprengen geschieht früh und abends, Tag für Tag mit einer Anzahl von Versen (siehe besonders Śaṅkhāyana und Pāraskara). In einem, wie es scheint, erst später eingeschalteten Sūtra bei Śaṅkhāyana wird noch hinzugefügt, dass »nach alter Überlieferung« auf Grund eines beim Sauparṇavrata vorgeschriebenen Brauches an fünf Stellen (Stirn, Herz, Schultern und Rücken) mit Asche drei Striche gemacht werden.

Über die Verehrung der Morgen- und Abenddämmerung finden sich bei Śaṅkhāyana. 2, 9. Āśvalāyana 3, 7, 3 ff. Vorschriften. Er soll sie schweigend im Walde vollziehen, Brennholz in der Hand, abends und morgens, bis zum Erscheinen der Sterne resp. der Sonne, abends nach NW., früh nach O. gewendet. Āśvalāyana schreibt das leise Hersagen der Sāvitrī, Śaṅkhāyana ausserdem die Mahāvyāhṛti's und Segenssprüche vor. Ferner muss er, wie Āśvalāyana hervorhebt, die Opferschnur tragen und die obligatorischen Waschungen und andere Wassergebräuche vollzogen haben. Wenn die Sonne untergeht, während er ohne krank zu sein schläft, sind gewisse Bußen zu vollziehen und ebenso früh (Āśvalāyana 3, 7, I. 2).

- Bettelgang. Bhikṣācaraṇa. Auch er geschieht früh und abends (Āśvalāyana 1, 22, 4). Der Brāhmaṇa soll betteln, indem er bhavat voranstellt, der Rājanya und Vaiśya, indem er es in die Mitte, resp. ans Ende stellt (Pāraskara 2, 5, 2 ff. Vaikhānasa. 2, 7. Kauśika 57, 16 ff.). Āśvalāyana bestimmt als Formel: bhavān bhikṣāṃm dadātu oder anupravacanīyam«. (»etwas zum Studium«!) (1, 22, 8. 9 und Stenzler's Anm. dazu). Zuerst soll er bei einem Mann oder einer Frau betteln, die ihn nicht zurückweist (Āśvalāyana I, 22, 6. 7)» nach Pāraskara 2, 5, 4 ff. bei drei, sechs oder mehr Frauen, die ihn nicht zurückweisen. Pāraskara 2, 5, 7 sagt, dass er »nach einigen« zuerst zu seiner Mutter gehe. Diese Vorschrift geben Gobhila 2, 10, 43; Śaṅkhāyana 2, 6, 5; Hiraṇyakeśin I, 7, 13. Gobhila setzt an zweite Stelle »noch zwei andere Freundinnen oder wieviel da sind« u. s. w. Der Schüler kündigt den Ertrag seiner Sammlung dem Lehrer an; nach Hiraṇyakeśin 1, 7, 15 mit dem Wort »bhaikṣa«, worauf dieser mit »tat subhaikṣa« erwidert. Hierauf soll er mit Erlaubnis des Lehrers essen (Śaṅkhāyana 2, 6, 7) und den Rest des Tages stehen (Āśvalāyana I, 22, 11) und schweigen. Pāraskara 2, 5, 8 nennt das die Meinung »einiger«. Wenn die Sonne untergegangen ist, kocht er den Mus für die Brāhmaṇa's von seinem anupravacanīya und meldet es dem Lehrer (Āśvalāyana 1, 22, II ff.). Der Lehrer opfert mit einem Verse an Sadasaspati, zum zweitenmal mit der Sāvitrī oder dem Text, der sonst studiert ist (s. Stenzler und Oldenberg zur Stelle) 3. den Ṛsi's und 4. Agni Sviṣṭakṛt. Er speist die Brahmanen und lässt sie das Ende des Vedastudiums aussprechen (siehe auch Śaṅkhāyana 2, 8; Hiraṇyakeśin 1, 7, 18.).

- Zu der Vorschrift c) »auf der Erde zu schlafen« kommen noch einige andere auf Nahrung u. s. w. bezügliche hinzu. Pāraskara 2, 5, 10 ff. heißt es, dass er scharfe und gesalzene Speisen, Honig (cf. Stenzler z. Stelle) und Fleisch vermeiden solle, nicht auf erhöhtem Sitz sitzen, nicht zu Frauen gehen dürfe u. s. w. Siehe auch Hiraṇyakeśin 1, 8, 8 ff.; Gobhila 3, 1, 15 ff. »vermeide Zorn und Unwahrheit, Beischlaf u. s. w.«

- Über d) Betragen gegen den Lehrer finden wir bei Pāraskara Vorschriften (2, 5, 29 ff.). Wenn der Lehrer ihn ruft, soll er aufstehen und antworten, wenn er steht, soll er hinzugehen, wenn er geht, soll er hinlaufend antworten. Wenn er sich so benimmt, heißt es, dann wird nach Ablauf seines Studiums der Ruhm ihm zuteil werden, dass man von ihm sagt »heut ist er in NN., heut in NN.« Andrerseits hat der Guru den Schüler zu behüten (Vaikhānasa 2. 8)."

[Quelle: Hillebrandt, Alfred <1853 - 1927>: Ritual-Litteratur, vedische Opfer und Zauber. -- Strassburg : Trübner, 1897. - 199 S. -- (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; III. Band, 2. Heft). -- S. 74f.]

2 täglichen Pflichten: für einen Hausvater, wie es der Lehrer ist, sind das vor allem die täglichen Opfer:

"Regelmäßige Opfer.— Tägliche Opfer. Abends und morgens opfert er beständig mit seiner Hand (ohne eines Löffels sich zu bedienen] zwei Spenden aus Reis oder Gerste, nach manchen auch aus saurer Milch oder geröstetem Korn an Agni und Prajāpati (Hiraṇyakeśin I, 23, 8) oder Agni resp. Agni Sviṣṭakṛt (Āpastamba 7, 20); nach einigen gebührt die Morgenspende Sūrya (Hiraṇyakeśin i, 23, 9; Āpastamba 7, 21) oder früh Sūrya und Prajāpati, abends Agni und Prajāpati (Pāraskara 1, 9, 3. 4; S. 1, 3, 14. 15; Kauśika 73, 2); zwei für Sūrya früh, zwei für Agni abends (Gobhila 1, 3, 9. 10). Pāraskara bestimmt dazu die Zeit nach Untergang resp. vor Aufgang der Sonne (1, 9, 2). Fast ebenso Gobhila 1, 1, 27 ff.; nach Āśvalāyana 1, 9, 4; S. 1, 1, 12 sind die Zeiten dieselben wie beim Agnihotra, indes gilt für gewisse Fälle bei Gobhila die Regel, dass bis zur Abendspende die Frühspende nicht versäumt wird und umgekehrt die Abendspende nicht bis zur Frühspende. Am Schluss seiner Vorschriften bemerkt Gobhila 1, 3, 13 ff. »in dieser Weise opfere oder lasse er in ein Hausfeuer opfern bis an sein Lebens Ende.« (Weitere Zurüstungen zu diesen Spenden Gobhila 1, 1, 2 4 ff.) Regelmäßige tägliche Spenden sind ferner die früh und abends stattfindenden pañca mahāyajñāḥ, die auch dem Śatapathabrāhmaṇa 11, 5, 6, 1ff. bekannt sind. Sie bestehen aus

- Spenden für die Götter (devayajña),

- für die Wesen (bhūtayajña),

- für die Manen (pitṛyajña),

- der Vedalesung (brahmayajña) und

- dem nṛyajña, den Gaben an Menschen.

Nur Āśvalāyana schreibt die Opfer a—c so in unmittelbarem Zusammenhang mit den sāyaṃprātarhomau vor, dass (1, 2, 2) eine deutliche Scheidung zwischen beiden nicht erkennbar ist und sich nur aus den andern Sūtren ergiebt. Die drei ersten der Mahāyajña's werden bisweilen unter dem Namen Vaiśvadevaopfer zusammengefasst, doch wird, wie Stenzler zu Āśvalāyana i, 2, 1 bemerkt, der Name auch in anderer, teils engerer, teils weiterer Bedeutung gebraucht.

Von diesen Opfern wird nun

- der devayajña im Feuer, leise mit der Hand (Gobhila), dargebracht und zwar nach Gobhila früh und abends, wenn die Frau das Essen als angerichtet gemeldet hat (1, 3, 16). Zwei Spenden werden nach Gobhila Kh. für Prajāpati und Sviṣṭakṛt geopfert, nach Pāraskara 2, 9, 2 Spenden für Brahman, Prajāpati, den Göttern des Hauses, Kaśyapa, Anumati, nach Āśvalāyana 1, 2 den Göttern des Agnihotra, Soma Vanaspati, Agni-Soma, Indra-Agni, Dyāvāpṛthivī, Dhanvantari, Indra, Viśve devāḥ, Brahman; bei Vaikānasa 3, 6; Śaṅkhāyana 2, 14, 1 ist die Zahl der Namen noch größer.

- Auf diese Spenden folgt b) das baliharaṇa, Deponierungsopfer, bestehend aus Gaben von jeglicher Speise (Gobhila 1, 4, 20), die er außerhalb oder innerhalb des Hauses an verschiedenen Stellen nach sorgfältiger Reinigung der Erde niederlegt. Die erste gebührt der Erde, die zweite Vāyu, die dritte den Viśve devāḥ, die vierte Prajāpati. Drei weitere Bali's finden ihren Platz am Wasserbehälter, dem mittleren Pfosten und der Haustür für die Gottheit des Wassers, für Pflanzen und Bäume und drittens für den Äther; eine siebente an Bett oder Abort für Kāma resp. Manyu, eine achte am Kehrichthaufen für die Rakṣas — das ist der bhūtayajña nach Gobhila. Andere Sūtren geben andere Namen. Kauśika 74, 2 lässt Brahman, Vaiśravaṇa, Viśve devāḥ, Sarve devāḥ u. a., an den Türpfosten Mṛtyu, Dharma, Adharma, beim Wassergefäß Dhanvantari, Samudra, Oṣadhi's, Vanaspati's, Dyāvāpṛthivī, an den Ecken Vāsuki, Citrasena, Citraratha, Takṣa, Upatakṣa u.s.w. opfern, Pāraskara 2,9,3ff. u. a. für Parjanya, Āpas, Pṛthivī am Wasserkrug, für Dhātṛ und Vidhātṛ an den beiden Türpfosten, für Vāyu und die Himmelsrichtungen entsprechend der Himmelsrichtung, in der Mitte für Brahman, Antarikṣa, Sūrya u. s. w. (vgl. noch Āśvalāyana 1, 2, 4fr.; S. 2, 14). Wenn der Hausherr verreist, können Sohn, Bruder, Gattin, auch Schüler das baliharaṇa vollziehen (Śāṅkhāyana 2, 17, 3; Gobhila sagt, dass Mann und Frau die Balis darbringen, jener morgens, dieser abends § 39).

- Den Rest der Balispeisen besprengt er mit Wasser und schüttet ihn im Süden aus, das ist c) der pitṛyajña (über dessen Einzelheiten Caland, Totenverehrung 10),

- der vierte der »Mahāyajña's« ist d) brahmayajña (Bhandarkar, IA, 3, 132; Knauer, Gobhila II, Pāraskara 139 Taittirīya Āraṇyaka Introduct. 22), die Vedalesung. Das Śatapathabrāhmaṇa 11, 5, 6, 3 erklärt Brahmayajña als svādhyāya und der Komm. als svaśākhādhyayana. Er ist Pflicht, wenn er auch auf Hersagung eines Hymnus beschränkt wird (Śāṅkhāyana 2, 17, 2; Nārada zu Āśvalāyana 3, 1, 4). Schon hieraus folgt, dass der Umfang dieser Lesung nicht überall gleich ist. So ist auch der Inhalt, den Śāṅkhāyana 1, 4 ihr gibt (eine Anzahl von ṚV.-Versen und Hymnen) wesentlich verschieden von dem bei Āśvalāyana 3, 3, 1 ff., der sich auf Ṛc, Yajus, Sāman, Atharvaveda, Brāhmaṇas u. s. w. bis auf die Purāṇa's erstreckt. Davon liest er »so viel er für gut hält« (4). Nach Āśvalāyana soll man nach O. oder N. aus dem Dorfe gehen und dort an einem reinen Platze entweder den Blick nach dem Horizont richten oder mit geschlossenen Augen die Lesung vornehmen.

- Der letzte (fünfte) der Mahäyajña's ist e) der nṛyajña oder manuṣyayajña, der in der Speisung von Gästen nach Vorschrift der Smṛti besteht. Von den Sūtren schildert Pāraskara 2, 9, 11 die Speisung etwas ausführlicher. Der Hausherr, der entweder zuerst oder mit seiner Gattin zuletzt isst, gibt dem Brahmanen sein praecipuum zuvor, worauf Bettler und Gäste, dann die Hausgenossen, jung und alt, nach Gebühr ihre Speise erhalten. All diese Opfer zu vollziehen, wird zur besonderen Pflicht gemacht. Nach Pāraskara 2, 9, 16; Śāṅkhāyana 2, 17, 2; Śatapathabrāhmaṇa 11, 5, 6, 2 soll er in jedem Falle tagtäglich seine Svāhāspende bringen. Wenn er keine Speise hat, dann mit etwas anderem, wäre es auch nur ein Holzscheit für die Götter, ein Krug Wasser für Manen und Menschen, ein Sūkta (s. oben) oder Anuvāka als Brahmayajña. Vereinzelt werden auch andere Gaben vorgeschrieben. Z. B. Gobhila 4, 7, 42 lässt (im Anschluss an die Hauseinweihung) den Göttern des Ostens, der Höhe und der Tiefe Tag für Tag eine Spende bringen."

[Quelle: Hillebrandt, Alfred <1853 - 1927>: Ritual-Litteratur, vedische Opfer und Zauber. -- Strassburg : Trübner, 1897. - 199 S. -- (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde ; III. Band, 2. Heft). -- S. 74f.]

idam evaṃvidhaṃ kasmān

nagaraṃ kṣetratāṃ gatam |

sarasvatyāś ca lakṣmyāś ca

tad upādhyāya kathyatām |3|

3. "Lehrer, erzähle uns bitte, warum diese solche Stadt1 zum Feld der Beredsamkeit und des Reichtums und der entspechenden Göttinnen2 geworden ist."

Kommentar:

1 diese Stadt = Pāṭaliputra (heutiges Patna, पटना)

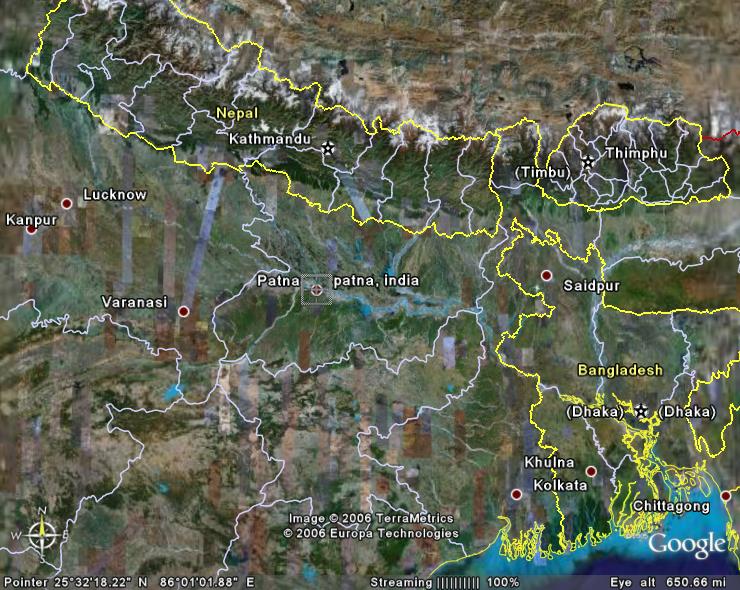

Abb.: Satellitenaufnahmen der Lage von Patna

(©Google Earth)

|

Patna |

|

|

State - District(s) |

Bihar - Patna |

| Coordinates | |

|

Area - Elevation |

3,202 km² - 53 m |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) |

|

Population (2001) - Density |

1.2 million - 375/km² |

| Mayor | Krishna Murari Yadav |

|

Codes - Postal - Telephone - Vehicle |

- 800 0xx - +0612 - BR-01-? |

Abb.: Satelliten-Detailaufnahmen von Patna

(©Google Earth)

"Patna (hindi पटना, Paṭnā) ist die Hauptstadt des Bundesstaates Bihar [बिहार], im Nordosten Indiens. Es war früher bekannt unter den Namen Kusumpura, Pushpapura, Pataliputra und bei Muslimen Asimabad. Patna liegt an den südlichen Ufern des Ganges, hat 1.458.800 Einwohner, als Agglomeration 1.808.900 (Stand jeweils 1. Januar 2004) und ist ein wichtiges Landhandelszentrum (Reis, Getreide, Zuckerrohr, Sesam). Sehenswürdigkeiten

Für die Sikhs, ist Patna eine heilige Stadt und einer ihrer Tempel wurde dort gegründet. Weiterhin wurde ihr zehnter und letzter menschlicher Guru, Guru Gobind Singh [Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਗੋਬਿੰਦ ਸਿੰਘ], in Patna geboren und der Schrein Harmandirji, der vom Punjabi-Führer Maharaja Ranjit Singh [Punjabi: ਮਹਾਰਾਜਾ ਰਣਜੀਤ ਸਿੰਘ] erbaut worden ist, markiert seinen Geburtsort.

Patna ist bekannt als die Geburtsstadt von Laloo Prasad Yadav [लालू प्रसाद यादव], dem amtierenden Eisenbahnminister von Indien, für sein Khaja (eine nordindische Delikatesse), seine Baumwollmühlen, und das Aquarium im Sanjay Gandhi Zoo, der nach dem indischen Politiker Sanjay Gandhi benannt wurde. Die Stadt hat ein bekanntes Museum, in dem Stein- und Bronzeskulpturen und Terracottafiguren ausgestellt werden, die von hinduistischen und buddhistischen Künstlern geschaffen wurden, sowie weitere archäologische Funde, wie ein riesiger fossiler Baum.

Andere Sehenswürdigkeiten sind die Orientalische Bibliothek Khuda Baksh, die eine Sammlung von historischen Werken besitzt und verschiedene Moscheen einschließlich der historischen Begu Hajjam Moschee, erbaut 1489 von Alauddin Hussani Shan, dem Herrscher von Bengul. Die Universität von Patna wurde 1917 eröffnet.

Eines der ältesten Gebäude, 1786 von Captain John Garstin während der britischen Herrschaft erbaut, ist das Gol Ghar, was Sphärisches Gebäude bedeutet und die einem Bienenkorb ähnliche Form beschreibt. Als Reaktion auf die Hungersnot von 1770 wurde es von den Engländern als Getreidespeicher genutzt. Von der Spitze des Gol Ghar hat man einen Blick über ganz Patna."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patna. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-12]

"History of Patna Patna (पटना), the capital of Bihar state, India, is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world and the History of Patna spans at least three millennia. Patna has the distinction of being associated with the two most ancient religions of the world, namely, Buddhism and Jainism, and has seen the rise and fall of might empires of the Mauryas and the Guptas. It has been a part of the Delhi Sultanate (دلی سلطنت) and the Mughal Empire [Persian: گوركانى], and has seen the rule of the Nawabs of Bengal, the East India Company and the British Raj. Patna has been one of the nerve centers of First War of Independence, participated actively in India’s Independence movement, and emerged in the post-independent India as the most populous city of East India after Kolkata [Bengali: কলকাতা].

Prelude

Patna, by its current name or any other name, finds no mention in the ancient Indian texts like the Vedas and the Puranas, or the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The first references to the place is observed about 2500 years ago in Jain and Buddhist scriptures.

Recorded history of the city begins in the year 490 BC when Ajatashatru, the king of Magadh, wanted to shift his capital from the hilly Rajagriha to a more strategically located place to combat the Lichavis of Vaishali. He chose a site on the bank of Ganges and fortified the area which developed into Patna.

From that time, the city has had a continuous history, a record claimed by few cities in the world. During its history and existence of more than two millennia, Patna has been known by different names : Pataligram, Pataliputra, Palibothra, Kusumpur, Pushpapura, Azimabad, Bankipore and the present day Patna.

Gautam Buddha passed through this place in the last year of his life, and he had prophesized a great future for this place, but at the same time, he predicted its ruin from flood, fire, and feud.

The nameEtymologically, Patna derives its name from the word Pattan, which means port in Sanskrit. It may be indicative of the location of this place on the confluence of four rivers, which functioned as a port. It is also believed that the city derived its name from Patan Devi, the presiding deity of the city, and her temple is one of the shakti peethas.

One legend ascribes the origin of Patna to a mythological king, Putraka, who created Patna by a magic stroke for his queen Patali, literally Trumpet flower, which gives it its ancient name Pataligram. It is said that in honour of the first born to the queen, the city was named Pataliputra. Gram is the Sanskrit for a village and Putra means a son.

The MauryasWith the rise of the Mauryan empire (321 BC-185 BC), Patna, then called Pataliputra became the seat of power and nerve center of the Indian subcontinent. From Pataliputra, the famed emperor Chandragupta (a contemporary of Alexander) ruled a vast empire, stretching from the Bay of Bengal to Afghanistan. Chandragupta established a strong centralized state with a complex administration under the tutelage of Kautilya.

Early Mauryan Patliputra was mostly built with wooden structures. The wooden buildings and palaces rose to several stories and were surrounded by parks and ponds. Another distinctive feature of the city was the drainage system. Water course from every street drained into a moat which functioned both as defence as well as sewage disposal. According to Megasthenes, Pataliputra of the period of Chandragupta, was "surrounded by a wooden wall pierced by 64 gates and 570 towers— (and) rivaled the splendors of contemporaneous Persian sites such as Susa and Ecbatana".

Chandragupta’s son Bindusara deepened the empire towards central and southern India. Patna under the rule of Ashoka, the grandson of Chandragupta, emerged as an effective capital of the Indian subcontinent.

Emperor Ashoka transformed the wooden capital into a stone construction around 273 BC. Chinese scholar Fa Hien [法顯], who visited India sometime around A.D. 399-414, has given vivid description of the stone structures in his travelogue.

According to Pliny the Elder in his "Natural History":

- "But the Prasii surpass in power and glory every other people, not only in this quarter, but one may say in all India, their capital Palibothra, a very large and wealthy city, after which some call the people itself the Palibothri,--nay even the whole tract along the Ganges. Their king has in his pay a standing army of 600,000 foot-soldiers, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 elephants: whence may be formed some conjecture as to the vastness of his resources." Plin. Hist. Nat. VI. 21. 8-23. 11.

Learning and scholarship received great state patronage. Patliputra produced several eminent world class scholars.

Scholars:

- Aryabhatta, the famous astronomer and mathematician who gave the approximation of Pi correct to four decimal places.

- Ashvaghosha, poet and influential Buddhist writer.

- Chanakya, or Kautilya, the master of statecraft, described by Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru as Indian Machiavelli—he was the guru of Chandragupta Maurya and author of the ancient text on statecraft, Arthashashtra.

- Panini, the ancient Hindu grammarian who formulated the 3959 rules of Sanskrit morphology. The Backus-Naur Form syntax used to describe modern programming languages have significant similarities to Panini’s grammar rules.

- Vatsyayana, the author of Kama Sutra.

It is believed that Pataliputra was the largest city in the world between 300 and 195 BC, taking that position from Alexandria [Greek: Αλεξάνδρεια, Coptic: Ⲣⲁⲕⲟⲧⲉ Rakotə, Arabic: الإسكندرية Al-ʼIskandariya,], Egypt and being succeeded by the Chinese capital Chang'an [長安] (modern Xi'an [西安]).

The GuptasBefore the Guptas

When the last of the Mauryan kings was assassinated in 184 BC, India once again became a collection of unfederated kingdoms. During this period, the most powerful kingdoms were not in the north, but in the Deccan to the south, particularly in the west. The north, however, remained culturally the most active, where Buddhism was spreading and where Hinduism was being gradually remade by the Upanishadic movements, which are discussed in more detail in the section on religious history. The dream, however, of a universal empire had not disappeared. It would be realized by a northern kingdom and would usher in one of the most creative periods in Indian history.

The Gupta Dynasty (320-550)

Under Chandragupta I (320-335), empire was revived in the north. Like Chandragupta Maurya, he first conquered Magadha, set up his capital where the Mauryan capital had stood (Patna), and from this base consolidated a kingdom over the eastern portion of northern India. In addition, Chandragupta revived many of Asoka's principles of government. It was his son, however, Samudragupta (335-376), and later his grandson, Chandragupta II (376-415), who extended the kingdom into an empire over the whole of the north and the western Deccan. Chandragupta II was the greatest of the Gupta kings; called Vikramaditya ("The Sun of Power"), he presided over the greatest cultural age in India.

This period is regarded as the golden age of Indian culture. The high points of this cultural creativity are magnificent and creative architecture, sculpture, and painting. The wall-paintings of Ajanta Cave in the central Deccan are considered among the greatest and most powerful works of Indian art. The paintings in the cave represent the various lives of the Buddha, but also are the best source we have of the daily life in India at the time. There are forty-eight caves making up Ajanta, most of which were carved out of the rock between 460 and 480, and they are filled with Buddhist sculptures. The rock temple at Elephanta (near Bombay) contains a powerful, eighteen foot statue of the three-headed Shiva, one of the principle Hindu gods. Each head represents one of Shiva's roles: that of creating, that of preserving, and that of destroying. The period also saw dynamic building of Hindu temples. All of these temples contain a hall and a tower.

The greatest writer of the time was Kalidasa. Poetry in the Gupta age tended towards a few genres: religious and meditative poetry, lyric poetry, narrative histories (the most popular of the secular literatures), and drama. Kalidasa excelled at lyric poetry, but he is best known for his dramas. We have three of his plays; all of them are suffused with epic heroism, with comedy, and with erotics. The plays all involve misunderstanding and conflict, but they all end with unity, order, and resolution.

The Guptas tended to allow kings to remain as vassal kings; unlike the Mauryas, they did not consolidate every kingdom into a single administrative unit. This would be the model for later Mughal rule and British rule built off of the Mughal paradigm.

The Guptas fell prey, however, to a wave of migrations by the Huns, a people who originally lived north of China. The Hun migrations would push all the way to the doors of Rome. Beginning in the 400's, the Huns began to put pressure on the Guptas. In 480 they conquered the Guptas and took over northern India. Western India was overrun by 500, and the last of the Gupta kings, presiding over a vastly dimished kingdom, perished in 550. A strange thing happened to the Huns in India as well as in Europe. Over the decades they gradually assimilated into the indigenous population and their state weakened.Harsha, who was a descendant of the Guptas, quickly moved to reestablish an Indian empire. From 606-647, he ruled over an empire in northern India. Harsha was perhaps one of the greatest conquerors of Indian history, and unlike all of his conquering predecessors, he was a brilliant administrator. He was also a great patron of culture. His capital city, Kanauj, extended for four or five miles along the Ganges River and was filled with magnificent buildings. Only one fourth of the taxes he collected went to administration of the government. The remainder went to charity, rewards, and especially to culture: art, literature, music, and religion.

Because of extensive trade, the culture of India became the dominant culture around the Bay of Bengal, profoundly and deeply influencing the cultures of Burma, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka. In many ways, the period during and following the Gupta dynasty was the period of "Greater India," a period of cultural activity in India and surrounding countries building off of the base of Indian culture. This medieval flowering of Indian culture would radically change course in the Indian Middle Ages. From the north came Muslim conquerors out of Afghanistan, and the age of Muslim rule began in 1100.

The SultanateWith the disintegration of the Gupta empire, and continuous invasions of the Indian subcontinent by foreign armies, Patna passed through uncertain time like most of north India.

During the 12th century, Muhammad of Ghor’s [Persian:محمد شہاب الدین غوری] advancing forces captured Ghazni, Multan, Sindh, Lahore, and Delhi, and one of his generals Qutb-ud-din Aybak (Persian: قطب الدین ایبک) proclaimed himself Sultan (Arabic: سلطان) of Delhi and established the first dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate (دلی سلطنت). By the mid-12th century, Ikhtiar Uddin Muhammad bin Bakhtiar Khilji (Persian اختيار الدين محمد بن بختيار الخلجي), one of the generals of Qutb-ud-din Aybak (Persian: قطب الدین ایبک), conquered Bihar and Bengal, and Patna became a part of the Delhi Sultanate. He is said to have destroyed many ancient seats of learning, the most prominent being the Nalanda University near Rajgrih, about 120 km from Patna. Patna, which had already lost its stature as the political centre of India, lost its prestige as the educational and cultural center of India as well.

The Mughals [Persian: گوركانى,]The Mughal period was a period of unremarkable provincial administration from Delhi. The most remarkable period of these times was under Sher Shah, or Sher Shah Suri (Pashto:شیر شاه سورى). Sher Shah Suri hailed from Sasaram, about 160 km south-west of Patna and revived Patna in the middle of the 16th century. On his return from one of the expeditions, while standing by the Ganga, he visualised a fort and a town. Sher Shah's fort in Patna does not survive, but the mosque built by Sher Shah in 1545 survives. It is built in Afghan architectural style. There are numerous tombs inside.

The earliest mosque in Patna is dated 1489 and is built by Alauddin Hussani Shah, one of the Bengal rulers. Local people call it the Begu Hajjam's mosque in honour of a barber who got it repaired in 1646.

Mughal emperor Akbar (Persian: جلال الدین محمد اکبر) came to Patna in 1574 to crush the Afghan Chief Daud Khan. Akbar's Secretary of State and author of Ain-i-Akbari refers to Patna as a flourishing centre for paper, stone and glass industries. He also refers to the high quality of numerous strains of rice grown in Patna that is famous as Patna rice in Europe.

Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb (Persian: اورنگزیب) acceded to the request of his favourite grandson Prince Muhamad Azim to rename Patna as Azimabad, in 1704 while Azim was in Patna as the subedar. However, other than the name, very little changed during this period.

The Nawabs (Urdu: نواب, Hindi: नवाब)With the decline of Mughal empire, Patna moved into the hands of the Nawabs of Bengal, who levied a heavy tax on the populace but allowed it to flourish as a commercial centre. During 17th century, Patna became a centre of international trade.

The British started with a factory in Patna in 1620 for the purchase and storage of calico and silk. Soon it became a trading centre for saltpetre, urging other Europeans—French, Danes, Dutch and Portuguese—to compete in the lucrative business. Various European factories and godowns started mushrooming in Patna and it acquired a trading fame that attracted far off merchants. Peter Mundy, writing in 1632, calls this place, "the greatest mart of the eastern region".

The Company ruleAfter the Battle of Buxar [बक्सर], 1764, the Mughals as well as the Nawabs of Bengal lost effective control over the territories then constituting the province of Bengal, which currently comprises the Indian states of West Bengal (Bengali: পশ্চিমবঙ্গ), Bihar (Hindī: बिहार), Jharkhand (Hindi: झारखंड, Bengali: ঝাড়খন্ড), Orissa (Oriya: ଓଡ଼ିଶା), as also some parts of Bangladesh [বাংলাদেশ]. The East India Company was accorded the diwani rights, that is , the right to administer the collection and management of revenues of the province of Bengal, and parts of Oudh, currently comprising a large part of Uttar Pradesh (Hindi: उत्तर प्रदेश, Urdu: اتر پردیش). The diwani rights were legally granted by Shah Alam, who was then ruling sovereign Mughal emperor of Undivided India.

The Battle of Buxar, which was fought hardly 115 km from Patna, heralded the establishment of the rule of the British East India Company in East India.

During the rule of the British East India Company in Bihar, Patna emerged as one of the most important commercial and trading centers of the East India, preceded only by Kolkata.

The British RajUnder the British Raj, Patna gradually started to attain its lost glory and emerged as an important and strategic centre of learning and trade in India. When the Bengal Presidency was partitioned in 1912 to carve out a separate province, Patna was made the capital of the new province of Bihâr and Orissa. The city limits were stretched westwards to accommodate the administrative base, and the township of Bankipore took shape along the Bailey Road (originally spelt as Bayley Road, after the first Lt. Governor, Charles Stuart Bayley). This area was called the New Capital Area.

To this day, locals call the old area as the City whereas the new area is called the New Capital Area. The Patna Secretariat with its imposing clock tower and the Patna High Court are two imposing landmarks of this era of development. Credit for designing the massive and majestic buildings of colonial Patna goes to the architect, I. F. Munnings.

By 1916-1917, most of the buildings were ready for occupation. These buildings reflect either Indo-Saracenic influence (like Patna Museum and the state Assembly), or overt Renaissance influence like the Raj Bhawan and the High Court. Some buildings, like the General Post Office (GPO) and the Old Secretariat bear pseudo-Renaissance influence. Some say, the experience gained in building the new capital area of Patna proved very useful in building the imperial capital of New Delhi.

The British built several educational institutions in Patna like Patna College, Patna Science College, Bihar College of Engineering, Prince of Wales Medical College and the Patna Veterinary College. With government patronage, the Biharis quickly seized the opportunity to make these centres flourish quickly and attain renown.

After the creation of Orissa as a separate province in 1935, Patna continued as the capital of Bihar province under the British Raj.

Patna played a major role in the Indian independence struggle. Most notable are the Champaran movement against the Indigo plantation and the Quit India Movement of 1942."

[Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Patna. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-12]

"Pātaligāma, Pātaliputta The capital of Magadha and situated near the modern Patna. The Buddha visited it shortly before his death. It was then a mere village and was known as Pātaligāma. At that time Ajātasattu's ministers, Sunīdha and Vassakāra, were engaged in building fortifications there in order to repel the Vajjīs. The Buddha prophesied the future greatness of Pātaligāma, and also mentioned the danger of its destruction by fire, water, or internal discord. The gate by which the Buddha left the town was called Gotamadvāra, and the ferry at which he crossed the river, Gotamatittha (Vin.i.226 30; D.ii.86ff).

The date at which Pātaliputtta became the capital is uncertain. Hiouen Thsang [玄奘] seems to record (Beal: Records ii.85, n. 11) that it was Kālāsoka who moved the seat of government there. The Jains maintain that it was Udāyi, son of Ajātasattu (Vin. Texts ii.102, n. 1). The latter tradition is probably correct as, according to the Anguttara Nikāya (iii.57) even Munda is mentioned as residing at Pātaliputta. It was, however, in the time of Asoka that the city enjoyed its greatest glory. In the ninth year of his reign Asoka's income from the four gates of the city is said to have been four hundred thousand kahāpanas daily, with another one hundred thousand for his sabhā or Council (Sp.i.52).

The city was known to the Greeks as Pālibothra, and Megasthenes, who spent some time there, has left a vivid description of it (Buddhist India 262f). It continued to be the capital during the greater part of the Gupta dynasty, from the fourth to the sixth century A.C. Near Pātaliputta was the Kukkutārāma, where monks (e.g. Ananda, Bhadda and Nārada) stayed when they came to Pātaliputta (M.i.349; A.v.341; A.iii.57; S.v.15f., 171f). At the suggestion of Udena Thera, the brahmin Ghotamukha built an assembly hall for the monks in the city (M.ii.163).

Pātaligāma was so called because on the day of its foundation several pātali shoots sprouted forth from the ground. The officers of Ajātasattu and of the Licchavi princes would come from time to time to Pātaligāma, drive the people from their houses, and occupy them themselves. A large hall was therefore built in the middle of the village, divided into various apartments for the housing of the officers and their retainers when necessary. The Buddha arrived in the village on the day of the completion of the building, and the villagers invited him to occupy it for a night, that it might be blessed by his presence. On the next day they entertained the Buddha and his monks to a meal (Ud.viii.6; UdA.407ff).

Pātaliputta was also called Pupphapura (Mhv.iv.31, etc.; Dpv.xi.28) and Kusamapura (Mbv.p.153).

The journey from Jambukola, in Ceylon, to Pātaliputta took fourteen days, seven of which were spent on the sea voyage to Tāmalitti (E.g., Mhv.xi.24). The Asokārāma built by Asoka was near Pātaliputta (Mhv.xxix.36). The Buddha's water pot and belt were deposited in Pātaliputta after his death (Bu.xxviii.9).

The Peta Vatthu Commentary (p.271) mentions that trade was carried on between Pātaliputta and Suvannabhūmi."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v. ]

2 der Beredsamkeit und des Reichtums und ihrer jeweiligen Göttin = sarasvatyāś ca lakṣmyāś ca: sarasvatī (Beredsamkeit) und lakṣmī (Reichtum) sind auch die Namen der beiden Göttinnen

Abb.: Sarasvatī, Newari-Malerei, Nepal[Bildquelle: shankargallery. -- http://www.flickr.com/photos/shankargallery/148973205/. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-16. --

Creative Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine Bearbeitung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung)]

"Saraswati (Sanskrit, f., सरस्वती, Sarasvatī) ist eine indische Göttin, die die weibliche Kraft (Shakti) des Gottes Brahma ist. Sie ist die älteste Göttin des Hinduismus und wird schon im Rig Veda erwähnt. Ursprünglich war sie eine Flussgöttin und wird auch heute noch mit dem fruchtbaren und reinen Wasser und dem Soma in Verbindung gebracht. Sie gilt als Göttin der Weisheit, des Intellekts, der Musik, Gelehrsamkeit, Sprache und Poesie, die die Schrift erfunden hat. Sie gilt als Verkörperung und Beschützerin der Kultur und der Künste. Sie wird als schlanke, junge Frau gezeigt, die vier Arme hat, in denen sie ein Gefäß mit Wasser trägt, ein Saiteninstrument (die Vina), eine Mala (Rosenkranz) und die Veden. Sie gilt als Verkörperung der Reinheit und Transzendenz. So ist ihr Reittier auch der Schwan, im Hinduismus ein Symbol der spirituellen Transzendenz und Perfektion. Oft wird sie auch auf einem Lotos sitzend dargestellt.

In der hinduistischen Mythologie wird erzählt, Saraswati sei aus dem Gott Brahma geboren worden. Brahma hatte das Verlangen, die Schöpfung hervorzubringen und begab sich in Meditation, woraufhin sich sein Körper in eine männliche und eine weibliche Hälfte, Saraswati, teilte. Brahma vereinte sich mit ihr und daraus entstand der Halbgott Manu, der die Welt erschuf. Oft wird auch erzählt, Saraswati entstamme dem Mund des Brahma und sei entstanden als dieser die Welt durch seine schöpferische Rede erschuf.

In einem anderen Mythos ist es Krishna, aus dem Saraswati entsteht. Dieser teilte sich in männlich und weiblich, Geist und Materie (Purusha und Prakriti) um die Welt zu erschaffen. Die weibliche Hälfte nahm die Form von fünf dynamischen Kräften oder Shaktis an, von denen eine Saraswati war. Ihre Funktion war es die Wirklichkeit mit Innenschau, Wissen und Lernen zu verbinden.

Vasant Panchami, der wichtigste Feiertag der Göttin, auch Saraswati Puja genannt, findet im Frühjahr statt. Bilder der Göttin werden in Schulen und Universitäten aufgestellt, Bücher, Schreibzeug, Musikinstrumente und Gurus werden geehrt und es gibt kulturelle Programme und Prozessionen.

In vielen indischen Religionen wird Saraswati verehrt, nicht nur im Hinduismus, sondern auch im Jainismus und Buddhismus. In Japan ist sie unter dem Namen Benten [弁天] oder Benzaiten [弁財天] bekannt. In Südindien beginnen Konzerte mit traditioneller Musik mit einer Invokation der Göttin.

Literatur

- David Kinsley: Hindu Goddesses. University of California Press 1986 ISBN 0-520-05393-1"

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarasvati. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-16]

Abb.: Lakshmi auf der Lotosblüte"Lakshmi (Sanskrit, f., लक्ष्मी, Lakṣmī) ist die hinduistische Göttin des Glücks und der Schönheit, nicht nur Spenderin von Reichtum sondern auch von geistigem Wohlbefinden, von Harmonie, von Fülle und Überfluss, Beschützerin der Pflanzen. Sie ist die Shakti, die erhaltende Kraft des Vishnu, und dessen Gemahlin.

Schon die Veden berichten über Lakshmi, die Göttin der Schönheit. Nach der Mythologie entstieg sie dem Milchozean, als dieser durch die Devas (Götter) und Asuras (Dämonen) auf der Suche nach Amrita (Trank, der unsterblich macht, Ambrosia) aufgeschäumt wurde. Dieser Mythos berichtet weiter, wie sie, dem Wasser entstiegen, Vishnu als Gatten erwählte.

Wird sie zusammen mit ihm als Gattin dargestellt, hat sie zwei Hände. Zeigt die Darstellung sie allein, sind es meist vier. Dann trägt sie in zwei Händen Lotosblüten, während die anderen beiden die trostgebende sowie gebende Handstellung zeigen. Aus Letzterer rinnen Goldstücke, die meist als Geld interpretiert werden. Am bekanntesten ist sie als Gajalakshmi, die auf einer Lotusblüte steht oder sitzt, von zwei Elefanten flankiert, die Wasser über sie gießen. Diese Form ist in Indien oft als Glückszeichen an Wohnhäusern zu finden. Oft zeigt die Ikonographie sie auch mit Lotos, Muschel, Topf mit dem Unsterblichkeitstrank Amrita sowie einer Bilva-Frucht. Ist die Darstellung achthändig, kommen noch Pfeil und Bogen hinzu sowie Diskus und Keule. Sie ist dann Mahalakshmi (Große Lakshmi), ein Aspekt Durgas und in diesem Fall nicht Gattin. Andere ihrer Erscheinungsformen sind die Göttinnen Bhumidevi (Personifikation der Erde), Buddhi (Wissen) und Siddhi (Erfolg, Vollendung). Sie ist auch mit dem elefantenköpfigen Ganesha verbunden, als dessen Shakti sie auch erscheint. Als Anapurna, die Ernährende, trägt sie ein Ährenbündel als Symbol der Fruchtbarkeit. Manchmal, besonders in bengalischen Versionen, ist eine Eule ihr Begleittier.

Lakshmi wird auch Shri-Lakshmi genannt, und als Shri ist sie ein Attribut des Vishnu, an dessen Körper sie als Symbol z.B. in Form eines Dreieckes erscheint.

Bei jeder Inkarnation des Vishnu verkörpert auch sie sich und begleitet ihn; kam Vishnu als heldenhafter König Rama, war sie dessen Gattin Sita, inkarnierte er sich als Krishna, war sie dessen Freundin Radha. Sie erscheint auch als Maya, Göttin der Illusion des Universums.

Vom Namen her ist Lakshmi in der indogermanischen Sprachfamilie etymologisch verwandt mit der schwedischen Lichtergöttin Lucia, dem lateinischen Lux (Licht) sowie dem englischen luck (Glück). Alle Begriffe sind die Attribute der Göttin.

Ihr heiliger Tag ist der Donnerstag, an dem besonders verheiratete Frauen sie mit Gebet und Opfer ehren. Sie gilt als deren Beschützerin und jede von ihnen als ihre Manifestation."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lakshmi. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-16]

tac chrutvā so 'bravīd asmāñ

chṛnutaitat kathām imām |

tīrthaṃ kanakhalaṃ nāma

gaṅgādvāre 'sti pāvanam |4|

4. Darauf antwortete er uns: "Hört dazu diese Erzählung: Am Gangestor1 gibt es eine reinigende Pilgerfurt2 namens Kanakhala3.

Kommentar:

1 Gangestor = gaṅgādvāra = heutiges Haridwār/हरिद्वार

Abb.: Lage von Haridwār

(©MS Encarta)

"Haridwār (Hindi: हरिद्वार, Haridvār; auch Hardwar) ist eine Stadt im Bundesstaat Uttaranchal [उत्तरांचल] im Norden von Indien mit 190.000 Einwohnern in einer Höhe von 316 m über NN Im Hinduismus ist sie eine bekannte Pilgerstätte und gilt als eine der sieben heiligen Stätten am Ganges.

Alle 12 Jahre findet hier an den Ufern des für Hindus heiligen Flusses Ganges eine Kumbh Mela statt, zu der Millionen von Pilgern erwartet werden. Die nächste ist im März - April 2010. Hauptzielpunkt der Pilger ist der Hari-ki-Pauri. Im Brahmakund fließen nach Vorstellung der Gläubigen die himmlischen Wasser in den Ganges. Ein Tempel hier soll den Fußabdruck Vishnus enthalten. Der Ort ist deshalb bedeutsam, weil hier der Eintritt des Ganges in die Ebene gesehen wird.

Oberhalb Haridwārs erhebt sich der Siwalik Hügel mit dem Tempel der Manasa Devi, zu dem eine Seilbahn führt. Auf dem Leel Parbat Hügel auf der gegenüberliegenden Flussseite ist der Tempel der Chandi Devi.

Etwa 20 km von Haridwār flussaufwärts liegt der Pilgerort Rishikesh, der berühmt ist für seine Ashrams und Tempel. Bekannt wurde er als die Beatles in den sechziger Jahren mit Maharishi Mahesh Yogi meditierten.

In dieser Stadt herrscht Alkoholverbot.

Geografische Lage: Koordinaten: 29° 58' N 78° 10' O 29° 58' N 78° 10' O"

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haridwār. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-13]

"Māyāpura, or Haridwār.

Hwen Thsang [玄奘] describes the town of Mo-yu-lo, or Māyura, as situated on the north-west frontier of Madawār, and on the eastern bank of the Ganges. At a short distance from the town there was a great temple called "the gate of the Ganges," that is, Gangā-dwāra, with a tank inside, which was supplied by a canal with water from the holy river. The vicinity of Gangā-dwāra, which was the old name of Haridwāra, shows that Māyura must be the present ruined site of Māyāpura, at the head of Ganges canal. But both of these places are now on the western bank of the Ganges, instead of on the eastern bank, as stated by Hwen Thsang. His note that they were on the north-west frontier of Madawār seems also to point to the same position; for if they had been on the western bank of the Ganges, they would more properly be described as on the northeastern frontier of Srughna. I examined the locality with some care, and I was satisfied that at some former period the Ganges may have flowed to the westward of Māyāpura and Kankhal down to Jwalapur. There is, however, no present trace of any old channel between the Gangādwāra temple and the hills; but as this ground is now covered with the houses of Haridwār, it is quite possible that a channel may once have existed, which has since been gradually filled up, and built upon. There is therefore no physical difficulty which could have prevented the river from taking this westerly course, and we must either accept Hwen Thsang's statement or adopt the alternative, that he has made a mistake in placing Māyura and Gangādwāra to the east of the Ganges.

There is a dispute between the followers of Śiva and Vishnu as to which of these deities gave birth to the Ganges. In the 'Vishnu Purāna' it is stated that the Ganges has its rise "in the nail of the great toe of Vishnu's left foot ;" and the Vaishnavas point triumphantly to the Hari-ki-charan, or Hari-ty-pairi (Vishnu's foot-prints), as indisputable evidence of the truth of their belief. On the other hand, the Śaivas argue that the proper name of the place is Hara-dwāra, or "Śiva's Gate," and not Hari-dwāra. It is admitted also, in the 'Vishnu Purāna,' that the Alakananda (or east branch of the Ganges) "was borne by Mahādeva upon his head." But in sipte of these authorities, I am inclined to believe that the present name of Haridwār or Haradwār is a modern one, and that the old town near the Gangādwāra temple was Māyāpura. Hwen Thsang, indeed, calls it Mo-yu-lo, or Māyura, but the old ruined town between Haridwār and Kankhal is still called Māyāpur, and the people point to the old temple of Māyā-Devī as the true origin of its name. It is quite possible, however, that the town may also have been called Māyura-pura, as the neighbouring woods still swarm with thousands of peacocks (Māyura), whose shrill calls I heard both morning and evening.

Hwen Thsang describes the town as about 20 li, or 31/3 miles, in circuit, and very populous. This account corresponds very closely with the extent of the old city of Māyāpura, as pointed out to me by the people. These traces extend from the bed of a torrent which enters the Ganges near the modern temple of Sarvvanāth to the old fort of Raja Ben, on the bank of the canal, a distance of 7500 feet. The breadth is irregular, but it could not have been more than 3000 feet at the south end, and, at the north end, where the Siwalik hills approach the river, it must have been contracted to 1000 feet. These dimensions give a circuit of 19,000 feet, or rather more than 31/2 miles. Within these limits there are the ruins of an old fort, 750 feet square, attributed to Raja Ben, and several lofty mounds covered with broken bricks, of which the largest and most conspicuous is immediately above the canal bridge. There are also three old temples dedicated to Nārāyana-sila, to Māyā-Devī, and to Bhairava. The celebrated ghat called the Pairi, or "Feet Ghat," is altogether outside these limits, being upwards of 2000 feet to the north-east of the Sarvvanāth temple. The antiquity of the place is undoubted, not only from the extensive foundations of large bricks which are everywhere visible, and the numerous fragments of ancient sculpture accumulated about the temples, but from the great variety of the old coins, similar to those of Sugh, which are found here every year.

The name of Haridwāra, or "Vishnu's Gate," would appear to be comparatively modern, as both Abu Rihan and Rashid-ud-din mention only Gangā-dwāra. Kālidās also, in his 'Meghadūta,' says nothing of Haridwāra, although he mentions Kankhal; but as his contemporary Amarasinha gives Vishnupadi as one of the synonyms of the Ganges, it is certain that the legend of its rise from Vishnu's foot is as old as the fifth century. I infer, however, that no temple of the Vishnupada had been erected down to the time of Abu Rihan. The first allusion to it of which I am aware is by Sharif-ud-din, the historian of Timur, who says that the Ganges issues from the hills by the pass of Cou-pele, which I take to be the same as Koh-pairi, or the "Hill of the Feet" (of Vishnu), as the great bathing ghat at the Gangādwāra temple is called Pairi Ghat, and the hill above it Pairi Pahar. In the time of Akbar, the name of Haridwār was well known, as Abul Fazl speaks of "Māyā, vulgo Haridwār, on the Ganges," as being considered holy for 18 kos in length. In the next reign the place was visited by Tom Coryat, who informed Chaplain Terry that at "Haridwāra, the capital of Siba, the Ganges flowed amongst large rocks with a pretty full current." In 1796 the town was visited by Hardwicke, who calls it a small place situated at the base of the hills. In 1808, Raper describes it as very inconsiderable, having only one street, about 15 feet in breadth, and a furlong and a half (or three-eighths of a mile) in length. It is now much larger, being fully three-quarters of a mile in length, but there is still only one street.

Hwen Thsang notes that the river was also called Fo-shui, which M. Stanislas Julien translates as l'eau qui porte bonheur, and identifies with Mahābhadra, which is one of the many well-known names of the Ganges. He mentions also that bathing in its waters was sufficient to wash away sin, and that if corpses were thrown into the river the dead would escape the punishment of being born again in an inferior state, which was due to their crimes. I should prefer reading Subhadra, which has the same meaning as Mahābhadra, as Ktesias [Κτησίας] mentions that the great Indian river was named ύπαρχος, which

he translates by φέρων πάντα τά αγαθά. Pliny quoting Ktesias calls the river Hypobarus, which he renders by "omnia in se ferre bona." A nearly similar word, Oibares, is rendered by Nicolas of Damascus as αγαθάγγελος. I infer, therefore, that the original name obtained by Ktesias was most probably Subhadrā."[Quelle: Cunningham, Alexander <1814 - 1893>: The ancient geography of India / ed. with introduction ande notes by Surendranath Majumdar Sastri. -- New. ed. -- Calcutta : Chuckervertty, Chatterjee & Co., 1924. -- 770 S. : Ill. -- S. 507 - 402 - 407.]

2 Pilgerfurt = Tīrtha

Ausführlich und kompetent zu Tīrthas siehe:

Kane, Pandurang Vaman <1880 - 1972>: History of Dharmasastra : (ancient and mediaeval, religious and civil law). -- Poona : Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. -- Vol. IV. -- 2. ed. -- 1973. -- S. 552 - 827

"Ein Tirtha (Sanskrit, n., तीर्थ, tīrtha, wörtl: "Furt, Übergang") bezeichnet im Hinduismus einen heiligen Ort, der eng mit 'Wasser' verbunden ist. Dies ist im allgemeinen ein Pilgerort. Der Begriff wurde jedoch auch ausgeweitet auf Personen (z.B. Ramatirtha), auf religiöse Texte, auf gewisse Punkte an der Hand (z. B. Brahmatirtha am Daumenballen) und auf alle möglichen Objekte, die als besonders rein und heilig betrachtet werden. Ursprünglich war ein Tirtha eigentlich nur eine Furt an einem Fluss, also eine Stelle, an der man sicher von einer Seite zur anderen übersetzen konnte. Diese Vorstellung wurde auf die metaphysische Ebene übertragen. Hier stellt ein Tirtha eine Übergangsstelle beziehungsweise einen Knotenpunkt zwischen verschiedenen Welten dar. An diesen Orten ist die Grenzlinie sehr schmal und durchlässig, deshalb ist es an einem Tirtha einerseits für den Menschen leichter Erlösung (moksha) zu erlangen, andererseits steigen gerade hier die Götter gerne von oben herab.

Aus diesen speziellen Orten hat sich in ganz Indien eine Sakralgeographie konstituiert. Bekannt sind vier panindische Tirthas, Wohnsitze der Götter, die das Land begrenzen:

- Badrinath im Norden,

- Jagannath Puri im Osten,

- Ramesvaram im Süden,

- Dvaraka im Westen

Weitere berühmte Tirthas sind

- die 12 Jyotirlingas von Shiva;

- die Shakta-Pithas der Göttin,

- die 4 Plätze der Kumbha Mela (Haridvar, Prayaga, Nasik, Ujjain) oder

- die 7 Städte der Erlösung (Ayodhya, Mathura, Haridvar, Varanasi, Kanci, Ujjain, Dvaraka).

In engem Zusammenhang mit dieser Sakralgeographie steht die Pilgerreise (tirtha-yatra) zu den verschiedenen Tirthas. Sie ist seit dem Mahabharata belegt und die Puranas preisen die daraus resultierenden religiösen Verdienste. Sie unterliegt an sich keinen kasten- und geschlechtsspezifischen Beschränkungen und sie verbindet kulturelle Elemente der alten Volkstraditionen mit dem Brahmanismus. So beobachtet man an Tirthas die Ausführung von brahmanische Riten wie den Opferguß ins Feuer (homa), Ahnenriten (sraddha), Morgen- und Abendmeditation (sandhya) und populäre Volkspraktiken wie Verehrungszeremonien (puja), gemeinsames Singen religiöser Lieder (kirtana), andächtiges Hören mythologischer Erzählungen (mahatmya sravana) oder religiöse Prozessionen (yatra). Im heutigen Hinduismus nimmt die Pilgerreise als Ausdruck der Religiosität eine zentrale Stellung ein.

Literatur

- Bhardwaj, S. M.: Hindu Places of Pilgrimage in India. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973.

- Eck, Diana L.: "India´s Tirthas: 'Crossings' in Sacred Geography". History of Religions 21.1981: 323-344.

- Kane, P. V.: History of Dharmasastra. Vol. IV, Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1953."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tirtha. -- ZUgriff am 2006-11-12]

3 Kanakhala: liegt nach Kane (a.a.O. S. 762, dort auch Stellennachweise) zirka zwei Meilen von Haridvāra entfernt am Ganges

yatra kāñcanapātena

jāhnavī devadantinā |

uśīnaragiriprasthād

bhittvā samavatāritā |5|

5. Dort hat der Götterelefant die Tochter Jahnus1 von der Hochebene des Uśīnara-Bergs2 in goldenem Fall3 herabsteigen lassen, nachdem er in diese Hochebene einen Spalt gemacht hatte.

Kommentar:

1 Tochter Jahnus = Jāhnavī = Gaṅgā

"Rishi Jahnu appears in the story of Ganga and Bhagiratha. When Ganga came to earth after being released from lord Shiva's locks, her torrential waters wreaked havoc with Jahnu's fields and penance. Angered by this, the great sage drank up all of Ganga's waters to punish her. Seeing this, the Gods prayed to the sage to release Ganga, so that she could proceed on her mission to release the souls of the ancestors of Bhagiratha. Jahnu relented and he released Ganga from his ear. For this, the Ganga river is also known as Jahnvi or Jahnavi, meaning "daughter of Jahnu"." [Quelle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jahnu. -- Zugriff am 2006-11-13]

2 Uśīnara-Berg: von mir nicht identifizierbar

3 Kāñcanapāta: "Goldfall". Tawney sieht dies als Eigennamen des Götterelefanten an. Brockhaus übersetzt ähnlich wie ich. Mehlig verbindet Tawney und Brockhaus, indem er den Ausdruck doppelt übersetzt.

dākṣiṇātyo dvijaḥ kaścit

tapasyan bhāryayā saha |

tatrāsīt tasya cātraiva

jāyante sma trayaḥ sutāḥ |6|

6. Dort war ein Brahmane aus dem Süden. Er übte zusammen mit seiner Frau Askese. Ihm wurden an jenem Ort drei Söhne geboren.

kālena svargate tasmin

sabhārye te ca tatsutāḥ |

sthānaṃ rājagṛhaṃ nāma

jagmur vidyārjanecchayā |7|

7. Nach einiger Zeit kamen er und seine Frau in den Himmel. Da sie Wissen erwerben wollten, zogen seine Söhne in den Ort Rājagṛha1.

Kommentar:

1 Rājagṛha = heutiges Rājgir in Bihār

Abb.: Lage von Rajgir

(©MS Encarta)

"Rājagaha A city, the capital of Magadha. There seem to have been two distinct towns; the older one, a hill fortress, more properly called Giribbaja, was very ancient and is said (VvA. p.82; but cp. D.ii.235, where seven cities are attributed to his foundation) to have been laid out by Mahāgovinda, a skilled architect. The later town, at the foot of the hills, was evidently built by Bimbisāra.

Hiouen Thsang says (Beal, ii.145) that the old capital occupied by Bimbisāra was called Kusāgra. It was afflicted by frequent fires, and Bimbisāra, on the advice of his ministers, abandoned it and built the new city on the site of the old cemetery. The building of this city was hastened on by a threatened invasion by the king of Vesāli. The city was called Rājagaha because Bimbisāra was the first person to occupy it. Both Hiouen Thsang and Fa Hsien (Giles: 49) record another tradition which ascribed the foundation of the new city to Ajātasattu.

Pargiter (Ancient Ind. Historical Tradition, p.149) suggests that the old city was called Kusāgrapura, after Kusāgra, an early king of Magadha. In the Rāmāyana (i. 7, 32) the city is called Vasumatī. The Mahābhārata gives other names - Bārhadrathapura (ii.24, 44), Varāha, Vrsabha, Rsigiri, Caityaka (see PHAI.,p.70).

It was also called Bimbisārapurī and Magadhapura (SNA.ii.584).

But both names were used indiscriminately (E.g., S.N. vs. 405), though Giribbaja seems, as a name, to have been restricted to verse passages. The place was called Giribbaja (mountain stronghold) because it was surrounded by five hills - Pandava, Gijjhakūta, Vebhāra, Isigili and Vepulla* - and Rājagaha, because it was the seat of many kings, such as Mandhātā and Mahāgovinda (SNA.ii.413). It would appear, from the names given of the kings, that the city was a very ancient royal capital. In the Vidhurapandita Jātaka (J.vi.271), Rājagaha is called the capital of Anga. This evidently refers to a time when Anga had subjugated Magadha.

* SNA.ii.382; it is said (M.iii.68) that these hills, with the exception of Isigili, were once known by other names e.g., Vankaka for Vepulla (S.ii.191). The Samyutta (i.206) mentions another peak near Rājagaha - Indakūta. See also Kālasilā.

The Commentaries (E.g., SNA. loc. cit) explain that the city was inhabited only in the time of Buddhas and Cakkavatti kings; at other times it was the abode of Yakkhas who used it as a pleasure resort in spring. The country to the north of the hills was known as Dakkhināgiri (SA.i.188).

Rājagaha was closely associated with the Buddha's work. He visited it soon after the Renunciation, journeying there on foot from the River Anomā, a distance of thirty leagues (J.i.66). Bimbisāra saw him begging in the street, and, having discovered his identity and the purpose of his quest, obtained from him a promise of a visit to Rājagaha as soon as his aim should be achieved (See the Pabbajjā Sutta and its Commentary). During the first year after the Enlightenment therefore, the Buddha went to Rājagaha from Gayā, after the conversion of the Tebhātika Jatilas. Bimbisāra and his subjects gave the Buddha a great welcome, and the king entertained him and a large following of monks in the palace. It is said that on the day of the Buddha's entry into the royal quarters, Sakka led the procession, in the guise of a young man, singing songs of praise of the Buddha. It was during this visit that Bimbisāra gifted Veluvana to the Order and that the Buddha received Sāriputta and Moggallāna as his disciples. (Details of this visit are given in Vin.i.35ff ). Large numbers of householders joined the Order, and people blamed the Buddha for breaking up their families. But their censure lasted for only seven days. Among those ordained were the Sattarasavaggiyā with Upāli at their head.

The Buddha spent his first vassa in Rājagaha and remained there during the winter and the following summer. The people grew tired of seeing the monks everywhere, and, on coming to know of their displeasure, the Buddha went first to Dakkhināgiri and then to Kapilavatthu (Vin.i.77ff).

According to the Buddhavamsa Commentary (p.13), the Buddha spent also in Rājagaha the third, fourth, seventeenth and twentieth vassa. After the twentieth year of his teaching, he made Sāvatthi his headquarters, though he seems frequently to have visited and stayed at Rājagaha. It thus became the scene of several important suttas - e.g., the Atānātiya, Udumbarika and Kassapasīhanāda, Jīvaka, Mahāsakuladāyī, and Sakkapañha.

For other incidents in the Buddha's life connected with Rājagaha, see Gotama. The most notable of these was the taming of Nālāgiri.

Many of the Vinaya rules were enacted at Rājagaha. Just before his death, the Buddha paid a last visit there. At that time, Ajātasattu was contemplating an attack on the Vajjians, and sent his minister, Vassakāra, to the Buddha at Gijjhakūta, to find out what his chances of success were (D.ii.72).

After the Buddha's death, Rājagaha was chosen by the monks, with Mahā Kassapa at their head, as the meeting place of the First Convocation. This took place at the Sattapanniguhā, and Ajātasattu extended to the undertaking his whole hearted patronage (Vin.ii.285; Sp.i.7f.; DA.i.8f., etc.). The king also erected at Rājagaha a cairn over the relics of the Buddha, which he had obtained as his share (D.ii.166). According to the Mahā Vamsa, (Mhv.xxxi.21; MT. 564) some time later, acting on the suggestion of Mahā Kassapa, the king gathered at Rājagaha seven donas of the Buddha's relics which had been deposited in various places - excepting those deposited at Rāmagāma - and built over them a large thūpa. It was from there that Asoka obtained relics for his vihāras.

Rājagaha was one of the six chief cities of the Buddha's time, and as such, various important trade routes passed through it. The others cities were Campā, Sāvatthi, Sāketa, Kosambī and Benares (D.ii.147).

The road from Takkasilā to Rājagaha was one hundred and ninety two leagues long and passed through Sāvatthi, which was forty five leagues from Rājagaha. This road passed by the gates of Jetavana (MA.ii.987; SA.i.243). The Parāyana Vagga (SN. vss.1011-3) mentions a long and circuitous route, taken by Bāvarī's disciples in going from Patitthāna to Rājagaha, passing through Māhissati, Ujjeni, Gonaddha, Vedisā. Vanasavhaya, Kosambī, Sāketa, Sāvatthi, Setavyā, Kapilavatthu, Kusinārā, on to Rājagaha, by way of the usual places (see below).

From Kapilavatthu to Rājagaha was sixty leagues (AA.i.115; MA.i.360). From Rājagaha to Kusinārā was a distance of twenty five leagues (DA.ii.609), and the Mahā Parinibbāna Sutta (D.ii.72ff ) gives a list of the places at which the Buddha stopped during his last journey along that road - Ambalatthikā, Nālandā, Pātaligāma (where he crossed the Ganges), Kotigāma, Nādikā (??), Vesāli, Bhandagāma, Hatthigāma, Ambagāma, Jambugāma, Bhoganagara, Pāvā, and the Kakuttha River, beyond which lay the Mango grove and the Sāla grove of the Mallas.

From Rājagaha to the Ganges was a distance of five leagues, and when the Buddha visited Vesāli at the invitation of the Licchavis, the kings on either side of the river vied with each other to show him honour. DhA.iii.439f.; also Mtu.i.253ff.; according to Dvy. (p.55) the Ganges had to be crossed between Rājagaha and Sāvatthi, as well, by boat, some of the boats belonging to the king of Magadha and others to the Licchavis of Vesāli.

The distance between Rājagaha and Nālandā is given as one league, and the Buddha often walked between the two (DA.i.35).

The books mention various places besides Veluvana, with its Kalandaka-nivāpa vihāra in and around Rājagaha - e.g., Sītavana, Jīvaka's Ambavana, Pipphaliguhā, Udumbarikārāma, Moranivāpa with its Paribbājakārāma, Tapodārāma, Indasālaguhā in Vediyagiri, Sattapanniguhā, Latthivana, Maddakucchi, Supatitthacetiya, Pāsānakacetiya, Sappasondikapabbhāra and the pond Sumāgadhā.

At the time of the Buddha’s death, there were eighteen large monasteries in Rājagaha (Sp.i.9). Close to the city flowed the rivers Tapodā and Sappinī. In the city was a Potter's Hall where travelers from far distances spent the night. E.g., Pukkusāti (MA.ii.987); it had also a Town Hall (J.iv.72). The city gates were closed every evening, and after that it was impossible to enter the city. Vin.iv.116f.; the city had thirty-two main gates and sixty four smaller entrances (DA.i.150; MA.ii.795). One of the gates of Rājagaha was called Tandulapāla (M.ii.185). Round Rājagaha was a great peta world (MA.ii.960; SA.i.31).

In the Buddha's time there was constant fear of invasion by the Licchavis, and Vassakāra (q.v.) is mentioned as having strengthened its fortifications. To the north east of the city were the brahmin villages of Ambasandā (D.ii.263) and Sālindiyā (J.iii.293); other villages are mentioned in the neighborhood, such as Kītāgiri, Upatissagāma, Kolitagāma, Andhakavinda, Sakkhara and Codanāvatthu (q.v.). In the Buddha's time, Rājagaha had a population of eighteen crores, nine in the city and nine outside, and the sanitary conditions were not of the best. SA.i.241; DhA.ii.43; it was because of the city's prosperity that the Mettiya-Bhummajakas made it their headquarters (Sp.iii.614). The city was not free from plague (DhA.i.232).

The Treasurer of Rājagaha and Anāthapindika had married each other’s sisters, and it was while Anāthapindika (q.v.) was on a visit to Rājagaha that he first met the Buddha.

The people of Rājagaha, like those of most ancient cities, held regular festivals; one of the best known of these was the Giraggasamajjā (q.v.). Mention is also made of troupes of players visiting the city and giving their entertainments for a week on end. (See, e.g., the story of Uggasena).

Soon after the death of the Buddha, Rājagaha declined both in importance and prosperity. Sisunāga transferred the capital to Vesāli, and Kālāsoka removed it again to Pātaliputta, which, even in the Buddha's time, was regarded as a place of strategically importance. When Hiouen Thsang visited Rājagaha, he found it occupied by brahmins and in a very dilapidated condition (Beal, op. cit., ii.167). For a long time, however, it seems to have continued as a center of Buddhist activity, and among those mentioned as having been present at the foundation of the Mahā Thūpa were eighty thousand monks led by Indagutta. Mhv.xxix.30."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v. ]

tatra cādhītavidyās te

trayo 'py ānāthyaduḥkhitāḥ |

yayuḥ svāmikumārasya

darśane dakśiṇāpatham |8|

8. Nach dem Studium der Wissenschaften gingen die Drei nach Süden, dorthin wo sich Svāmikumāra1 zeigt2. Sie waren nämlich unglücklich über ihre Schutzlosigkeit.

Kommentar:

1 Svāmikumāra = Svāmī = Kumāra = Skanda/Kārtikeya/Murugan. Siehe oben zu Vers 44.

2 darśana

"Darshan is a Sanskrit (also used to some extent in Urdu) term meaning sight (in the sense of an instance of seeing something or somebody), vision, apparition, or a glimpse. It is most commonly used for visions of the divine; that is, of a god or a very holy person or artifact. One could receive "darshan" of the deity in the temple or from a great saintly person, such as the Spiritual Master.