Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Materialien zum Buddha des Glaubens. -- 3. Bodhisattadhammatā - Gesetzmäßigkeiten eines Bodhisatta. -- Fassung vom 2007-10-18. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/glaubensbuddha/buddhglaub03.htm

Erstmals publiziert: 2007-10-18

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung HS 2007

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Buddhismus von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Im Mahāpadānasutta1 des Dīghanikāya werden anhand des früheren Buddha Vipassī die Gesetzmäßigkeiten eines Bodhisatta dargestellt:

1 Mahāpadānasutta = "Große Lehrrede von der Verbindung [des Buddha Gotama] mit der Vergangenheit", apadāna = nidāna = "Band, Bindung, Ursprung, Grundursache" (H. Zimmer, 1925)

Zum Mahāpadānasutta siehe:

Das Mahāpadānasūtra : ein kanonischer Text über die sieben letzten Buddhas. Sanskrit, verglichen mit dem Pāli nebst einer Analyse der in chinesischer Überstzung überlieferten Parallelversionen / auf Grund von Turfan-Handschriften herausgegeben von Ernst Waldschmidt. -- Berlin : Akademie-Verlag.

Teil I: Einführung und Sanskrittext im handschriftlichen Befund. -- 1953.

Teil II: Die Textbearbeitung. -- 1956.

(Abhandlungen der deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Klasse für Sprachen, Literatur und Kunst ; Jg. 1952 Nr. 8 ; Jg. 1954 Nr. 3)

(PTS II, S.8ff.):

| Iccheyyātha no tumhe, bhikkhave, bhiyyosomattāya

pubbenivāsapaṭisaṃyuttaṃ dhammiṃ kathaṃ sotun ti?

Etassa, bhagavā, kālo; etassa, sugata, kālo; yaṃ bhagavā bhiyyosomattāya pubbenivāsapaṭisaṃyuttaṃ dhammiṃ kathaṃ kareyya, bhagavato sutvā bhikkhū dhāressantī ti. Tena hi, bhikkhave , suṇātha, sādhukaṃ manasi karotha, bhāsissāmī ti. Evaṃ, bhante ti kho te bhikkhū bhagavato paccassosuṃ. Bhagavā etad avoca – |

"Möchtet ihr, Mönche, ausführlich eine

Lehrrede über vergangenes Dasein hören?" "Dafür ist es, Ehrwürdige, nun der rechte Zeitpunkt, dafür ist es, Ehrwürdiger, nun der rechte Zeitpunkt, dass der Ehrwürdige ausführlich eine Lehrrede hält über vergangenes Dasein. Wenn sie es vom Ehrwürdigen gehört haben, werden es die Mönche behalten." "Hört also, Mönche, seid aufmerksam, ich spreche." Die Mönche gaben ihre Zustimmung. Der Ehrwürdige sprach: |

16. Ito so, bhikkhave,

ekanavutikappe yaṃ vipassī bhagavā arahaṃ sammāsambuddho loke udapādi.

|

Im 91. Weltzeitalter vor diesem ist der

Ehrwürdige Vipassī1 als vollkommen zur Erlösung Gelangter, vollkommen

richtig von selbst zur Wahrheit Erwachter in der Welt aufgetreten. Der Ehrwürdige Vipassī

|

Erläuterung:

1 Vipassī: im Mahāpadānasutta werden sechs frühere Buddhas genannt. Die (mit Gotama) sieben Buddhas scheinen den sieben Ṛṣi's der Brahmanen nachgebildet zu sein oder den sieben Manu's

"Vipassī The nineteenth of the twenty four Buddhas. He was born in the Khema park in Bandhumatī, his father being Bandhumā and his mother Bandhumatī. He belonged to the Kondañña gotta. For eight thousand years he lived as a householder in three palaces: Nanda, Sunanda and Sirimā. His body was eighty cubits in height. His wife was Sutanā (v.l. Sudassanā) and his son Samavattakkhandha. He left the household in a chariot and practised austerities for eight months. Just before his enlightenment, the daughter of Sudassana setthi gave him milk rice, while a yavapālaka named Sujāta gave grass for his seat. His bodhi was a pātali tree. He preached his first sermon in Khemamigadāya to his step brother Khandha and his purohita's son Tissa; these two later became his chief disciples. His constant attendant was Asoka; Candā and Candamittā were his chief women disciples. His chief lay patrons were Punabbasummitta and Nāga among men, and Sirimā and Uttarā among women. He died in Sumittārāma at the age of eighty thousand, and his relics were enshrined in a thūpa seven leagues in height. The Bodhisatta was a Nāga king named Atula. (Bu.xx.1ff.; BuA.195f.; D.ii.2ff).

Three reasons are given for the name of this Buddha (BuA.195; cf. DA.ii.454; SA.ii.15): (1) Because he could see as well by night as by day; (2) because he had broad eyes; (3) because he could see clearly after investigation. Vipassī held the uposatha only once in seven years (DhA.iii.236), but on such occasions the whole Sangha was present (Sp.i.186). The construction of a Gandhakuti for Vipassī brought Mendaka great glory in the present age. Mendaka's name at the time was Avaroja (DhA.iii.364f). Aññākondañña was then known as Cūlakāla, and nine times he gave Vipassī Buddha the first fruits of his fields. DhA.i.81f."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

Personaldaten der im Mahāpadānasutta genannten Buddhas:

| Vipassī | Sikhī | Vessabhū | Kukusandho | Koṇāgamo | Kassapo | Gotamo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kappa (Weltzeitalter) |

91. | 31. | 31. | jetziger | jetziger | jetziger | jetziger |

| jāti (Stand) |

khattiya (Adel) |

khattiya (Adel) |

khattiya (Adel) |

brāhmaṇa (Geistlicher) |

brāhmaṇa (Geistlicher) |

brāhmaṇa (Geistlicher) |

khattiya (Adel) |

| gotta (Clan) |

Koṇḍañña | Koṇḍañña | Koṇḍañña | Kassapa | Kassapa | Kassapa | Gotama |

| āyuppamāṇa (Lebensalter) |

80.000 | 70.000 | 60.000 | 40.000 | 30.000 | 20.000 | höchstens 100 (80) |

| bodhirukkha (Baum bei erlösender Einsicht) |

pāṭali (Stereospermum suaveolens DC.) (Trompetenblumenbaum) |

puṇḍarīka (Artemisia indica - Willd.) (Beifuß) |

sāla (Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.) (Salbaum) |

sirīsa (Acacia sirissa Buch.-Ham.) |

udumbara (Ficus racemosa L.) (Doldenfeige) |

nigroḍha (Ficus benghalensis L.) (Banyanfeige, Luftwurzelfeige) |

assattha (Ficus religiosa L.) (Bobaum) |

| sāvakayuga (die beiden Hauptjünger) |

Khaṇḍo, Tisso | Abhibhū, Sambhavo | Soṇo, Uttaro | Vidhuro, Sañjīvo | Bhiyyoso, Uttaro | Tisso, Bhāradvājo | Sāriputto, Moggalāno |

| sāvakasannipātā (Versammlungsgröße) |

6.800.000 100.000 80.000 |

100.000 80.000 70.000 |

80.000 70.000 60.000 |

40.000 | 30.000 | 20.000 | 1.250 (Bei Pāṭimokkha-Verkündigung) |

| aggupaṭṭhāka (Sekretär) |

Asoko | Khemkkuro (od. Khemiṅkaro) |

Upasanto (od. Upasannako) |

Buddhijo (od. Vaḍḍhijo) |

Sotthijo | Sabbamitto | Ānando |

| mātāpitā (Eltern) |

Bandhumā rājā + Bandhumatī | Aruṇo rājā + Pabhāvatī | Suppatito (Suppatīto) rājā + Vassavatī (Yasavatī) | Aggidatto + Visākhā | Yaññadatto + Uttarā | Brahmadatto + Dhanavatī | Suddhodano rāja + Māyā |

| rājadhāni (Hauptstadt) |

Bandhumatī | Aruṇavatī | Anomaṃ (Anopamaṃ) | König: Khemo Stadt: Khemavatī |

König: Sobho Stadt: Sobhavatī |

König: Kikī (Kiṅkī) Stadt: Bārāṇasī |

Kapilavatthu |

2 Stand (varṇa): siehe

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Dharmashastra : Einführung und Überblick. -- 4. Sitte und Recht der Stände (varnadharma). -- URL: http://www.payer.de/dharmashastra/dharmash04.htm

3 Clan (gotra): siehe

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Dharmashastra : Einführung und Überblick. -- 7. Eheschließung. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/dharmashastra/dharmash07.htm

4 Kondañña

"Kondañña. The name of a gotta. It was evidently common to both brahmans and khattiyas, for we find the brahman Aññāta-Kondañña belonging to it, and elsewhere (E.g., VibbA.464) it is mentioned as a khattiyagotta.

Among those mentioned as belonging to the Kondañña-gotta are:

- Buddha Kondañña (brahmin),

- Candakumāra (J.vi.137, 138) (khattiya),

- Sarabhanga (J.v.140,141, 142) (brahmin),

- the three Buddhas Vipassī, Sikhī and Vessabhū, all khattiyas (D.ii.3ff, see table in Dial.16).

In the Kacchapa Jātaka (J.ii.360f) it is said that tortoises are of the Kassapa-gotta and monkeys of the Kondañña-gotta, and that between these two classes there is intermarriage."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

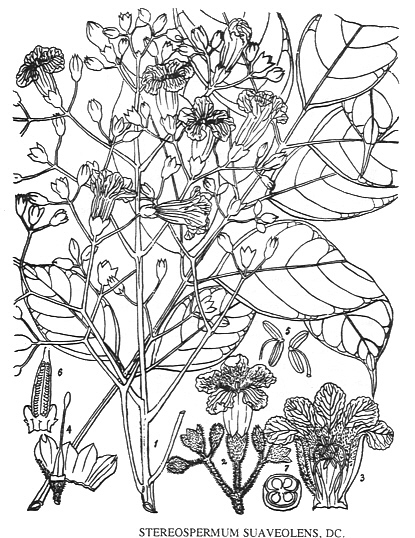

4 Stereospermum suaveolens DC.

- Stereospermum suaveolens DC. = Bignonia suaveolens Roxb.

- griech. stereos = starr, hart, griech sperma = Same; lat. suaveolens: süßriechend

- Bignoniaceae - Trompetenbaumgewächs

- "S. suaveolens, DC. Prodr. ix. 211 ; leaflets broadly elliptic acuminate or acute entire or serrulate young hairy, panicle very compound manyfld. viscous hairy, corolla 1-l¼ in., capsule linear terete woody, seeds subtrigonous embedded in notches of the septum. Wight Ic. t. 1342 ; Bedd. For.Man. 169 ; Brand. For. Fl. 351 ; Kurz For. Fl. ii. 231. Bignonia suaveolens, Roxb. Fl. Ind. iii. 104; Wall. Cat. 6499. Tecoma suaveolens, G. Don Gen. Syst. iv. 244. Heterophragma suaveolens, Dalz. & Gibs. Bomb.Fl. 161.

Throughout moister INDIA from the Himalayan Terai to Travancore and Tenasserim. CEYLON (Thwaites thinks only planted in).

A tree, 30-60 ft. ; innovations viscous-hairy. Leaves 12-18 in. ; leaflets 7-9 5½ by 3 in. ; petiolule hardly 1/10 in. Calyx 1 in., hairy ; lobes 3-5, very short,broad. Corolla pale or dark purple, puberulous without, hairy in the throat ; lobes rounded, crisped-crenate. Capsule 18 by 2/3 in., slightly rough with tubercles, obscurely 4-ribbed, glabrous. Seeds 1¼ by ¼ in., deeply notched at the middle." (Hooker, J. D. (Joseph Dalton) <1817 - 1911>: Flora of British-India. -- Vol. 4. -- 1885. -- S. 382f.)

- sanskrit:

- pāṭalā

- Bhāvaprakāśa:

- pāṭala

- pāṭalā

- amoghā

- madhudūta

- phaleruhā

- kṛṣṇavṛntā

- kuberākṣī

- kālasthā

- ali

- alivallabhā

- tāmrapuṣpī

- Bhāvaprakāśa: I, S. 230

- Pandey: III, 75ff.

- Kirtikar-Basu: Bd. 8, 2546ff.

- ausführlich: http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/pflanzen/stereospermum_suaveolens.htm

Abb.: Stereospermum suaveolens DC.

[Bildquelle: Kirtikar-Basu, ©1918]

Abb.: Der Pāṭali-Baum Buddha Vipassī's, Bharhut, 2. Jhdt. v. Chr.

| Bodhisattadhammatā | |

| 17. [1.] Atha kho, bhikkhave, vipassī bodhisatto tusitā kāyā cavitvā sato sampajāno mātukucchiṃ okkami. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [1.] Da ist der Bodhisatta Vipassī im

Tusitahimmel1 dahingeschieden und achtsam und wissensklar2 in den Schoß

seiner Mutter herabgestiegen. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit.

|

Erläuterung:

1 Tusita: die vierthöchste der sechs Götterwelten:

kāma-bhava m. -- Existenzebene der Begierden,grobkörperliche Existenzebene = Kāma-loka m. -- Welt der Begierden, Sinnenwelt:

- 2. Sugati f. -- gute Orte der Wiedergeburt:

- 2. Deva-loka m. -- Götterwelten:

- 6. Para-nimittavasavatti

- 5. Nimmāṇa-rati

- 4. Tusita

- 3. Yāma

- 2. Tavatiṃsa

- 1. Cātum-mahārājika

- 1. Manussa-loka m. -- Menschen

- 1. Duggati f. -- schlechte Orte der Wiedergeburt:

- 4. Asura-yoni f. -- als Dämon

- 3. Peta-yoni f. -- als Gespenst

- 2. Tiracchāna-yoni f. -- als Tier

- 1. Niraya m. -- Höllen

"Tusita. The fourth of the six deva worlds (A.i.210, etc.).

Four hundred years of human life are equal to one day of the Tusita world and four thousand years, so reckoned, is the term of life of a deva born in Tusita (A.i.214; iv.261, etc.).

Sometimes Sakadāgāmins (e.g., Purāna and Isidatta) are born there (A.iii.348; v.138; also DhA.i.129; UdA.149, 277).

It is the rule for all Bodhisattas to be born in Tusita in their last life but one; then, when the time comes for the appearance of a Buddha in the world, the devas of the ten thousand world systems assemble and request the Bodhisatta to be born among men. Great rejoicings attend the acceptance of this request (A.ii.130; iv.312; DhA.i.69f; J.i.47f).

Gotama's name, while in Tusita, was Setaketu (Sp.i.161), and the Bodhisatta Metteyya, the future Buddha, is now living in Tusita under the name of Nathadeva.

The Tusita world is considered the most beautiful of the celestial worlds, and the pious love to be born there because of the presence of the Bodhisatta (Mhv.xxxii.72f).

Tusita is also the abode of each Bodhisatta's parents (DhA.i.110).

The king of the Tusita world is Santusita; he excels his fellows in ten respects - beauty, span of life, etc. (A.iv.243; but see Cv.lii.47, where the Bodhisatta Metteyya is called the chief of Tusita).

Among those reborn in Tusita are also mentioned Dhammika, Anāthapindika, Mallikā, the thera Tissa (Tissa 10), Mahādhana and Dutthagāmani.

The Tusita devas are so-called because they are full of joy (tuttha-hatthāti Tusitā) (VibhA.519; NidA.109).

The inhabitants of Tusita are called Tusitā. They were present at the Mahāsamaya (D.ii.161)."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

2 sato sampajāno = achtsam und wissensklar: siehe dazu das Mahāsatipaṭṭhānasutta: Payer, Alois <1944-- >: Materialien zu einigen Lehrreden des Dīghanikāya. -- D II, 9: Mahāsatipatthānasutta. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/dighanikaya/digha209.htm

| 18. [2.] Dhammatā, esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto tusitā kāyā cavitvā mātukucchiṃ okkamati. Atha sadevake loke samārake sabrahmake sassamaṇabrāhmaṇiyā pajāya sadevamanussāya appamāṇo uḷāro obhāso pātubhavati atikkamm' eva devānaṃ devānubhāvaṃ. Yā pi tā lokantarikā aghā asaṃvutā andhakārā andhakāratimisā , yattha p' ime candimasūriyā evaṃmahiddhikā evaṃmahānubhāvā ābhāya nānubhonti, tattha pi appamāṇo uḷāro obhāso pātubhavati atikkamm eva devānaṃ devānubhāvaṃ. Ye pi tattha sattā upapannā, te pi ten' obhāsena aññamaññaṃ sañjānanti – aññepi kira, bho, santi sattā idhūpapannā ti. Ayañ ca dasasahassī lokadhātu saṅkampati sampakampati sampavedhati. Appamāṇo ca uḷāro obhāso loke pātubhavati atikkamm eva devānaṃ devānubhāvaṃ. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [2.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn ein Bodhisatta aus dem Tusitahimmel in den Schoß seiner Mutter herabsteigt, dann entsteht in der Welt mit ihren Māra's1, Brahmā's2, den Asketen und Brahmanen, den Göttern und Menschen ein unermesslich großes Licht, das die Pracht der Götter übertrifft. Sogar in der ungehinderten Dunkelheit zwischen den Welten, die die so mächtigen Mond und Sonne mit ihrem Licht nicht bezwingen können; sogar dort entsteht ein unermesslich großes Licht, das die Pracht der Götter übertrifft. Die Wesen, die dort entstanden sind, erkennen sich in diesem Licht gegenseitig. "Es gibt auch andere Wesen, die hier entstanden sind!" So erzittert und erbebt das 10.000fache Weltall. Und es entsteht in der Welt ein unermesslich großes Licht, das sogar die Pracht der Götter übertrifft. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 Māra

"Māra Generally regarded as the personification of Death, the Evil One, the Tempter (the Buddhist counterpart of the Devil or Principle of Destruction). The legends concerning Māra are, in the books, very involved and defy any attempts at unravelling them. In the latest accounts, mention is made of five Māras

- Khandha Māra,

- Kilesa Māra,

- Abhisankhāra Māra,

- Maccu Māra and

- Devaputta Māra

as shown in the following quotations: pañcannam pi Mārānam vijayato jino (ThagA.ii.16); sabbāmittehi khandha-kilesā-bhisankhāramaccudeva-puttasankhāte, sabbapaccatthike (ThagA.ii.46); sankhepato vā pañcakilesa-khandhābhi-sankhāra-devaputta-maccumāre abhañji, tasmā . . . bhagavā ti vuccati (Vsm.211).

Elsewhere, however, Māra is spoken of as one, three, or four. Where Māra is one, the reference is generally either to the kilesas or to Death. Thus:

- Mārenāti kilesamārena (ItvA.197);

- Mārassa visaye ti kilesamārassa visaye (ThagA.ii.70);

- jetvāna maccuno senam vimokkhena anāvaran ti lokattayābhibyāpanato diyaddhasahassādi vibhāgato ca vipulattā aññehi avāritum patisedhetum asakkuneyyattā ca maccuno, Mārassa, senam vimokkhena ariyamaggena jetvā (ItvA.198);

- Mārāsenā ti ettha satte anatthe niyojento māretīti Māro (UdA.325);

- nihato Māro bodhimūle ti vihato samucchinno kilesamāro bodhirukkhamūle (Netti Cty. 235);

- vasam Mārassa gacchatīti kilesamārassa ca sattamārassa (?) ca vasam gacchi (Netti, p. 86);

- tato sukhmnataram Mārabandhanan ti kilesabandhanam pan' etam tato sukhumataram (SA.iii.82);

- Māro māro ti maranam pucchati, māradhammo ti maranadhammo (SA.ii.246).

It is evidently with this same significance that the term Māra, in the older books, is applied to the whole of the worldly existence, the five khandhas, or the realm of rebirth, as opposed to Nibbāna.

Thus Māra is defined:

- at CNid. (No. 506) as kammābhisankhāravasena patisandhiko kandhamāro dhātumāro, āyatanamāro.

- And again: Māro Māro ti bhante vuccati katamo nu kho bhante Māro ti? Rūpam kho, Rādha, Māro, vedanāmāro, saññāmāro, sankhāramāro viññānam Māro (S.iii.195);

- yo kho Rādha Māro tatra chando pahātabbo. Ko ca Rādha Māro? Rūpam kho Rādha Māro . . . pe . . . vedanāmāro. Tatra kho Rādha chando pahātabbo (S.iii.198);

- sa upādiyamāno kho bhikku baddho Mārassa, anupadiyamāno mutto pāpimāto (S.iii.74);

- evam sukhumam kho bhikkhave, Vepacittibandhanam; tato sukhumataram mārabandhanam; maññamāno kho bhikkhave baddho Mārassa, amaññamāno mutto pāpimato (S.iv.202);

- labhati Māro otāram, labhati Māro ārammanam (S.iv.85);

- santi bhikkhave cakkhuviññeyyarūpā ... pe . . . tañ ce bhikkhu abhinandati . . . pe . . . ayam vuccati bhikkhave bhikkhu āvāsagato Mārassa, Mārassa vasam, gato (S.iv.91);

- dhunātha maccuno senam nalāgāram va kuñjaro ti paññindriyassa padathānam (Netti, p. 40);

- rūpe kho Rādha sati Māro vā assa māretā vā yo vā pana mīyati. Tasmā he tvam Rādha rūpam māro ti passa māretā ti passa mīyatīti passa ... ye nam evam passanti te sammā passanti (S.iii.189);

- Mārasamyogan ti tebhūmakavattam (SNA.ii.506).

The Commentaries also speak of three Māras:

- bodhipallanke tinnam Mārānam matthakam bhinditvā (DA.ii.659);

- aparājitasanghan ti ajj' eva tayo Māre madditvā vijitasangānam matthakam madditvā anuttaram sammāsambodhim abhisambuddho (CNidA. p. 47).

In some cases the three Māras are specified:

- yathayidam bhikkhave mārabalan ti yathā idam devaputtamāra maccumāra kilesamārānam balam appasaham durabhisambhavam (DA.iii.858);

- maccuhāyino ti maranamaccu kilesamccu devaputtamaccu hāyino, tividham pi tam maccum hitvā gāmino ti vuttam hoti (SNA.ii.508; cp. MA.ii.619);

- na lacchati Māro otāram, Māro ti devaputtmāro pi maccumāro pi kilesamāro pi (DA.iii.846);

but elsewhere five are mentioned e.g.,

- ariyamaggakkhane kilesamāro abhisahkhāramāro, devaputtamāro ca carimaka cittakkhane khandhamāro maccumāro ti pañcavidhamāro abhibhūto parājito (UdA.216).

Very occasionally four Māras are mentioned:

- catunnam Mārānam matthakam madditvā anuttaram sammāsambodhim abhisamabuddho (MNid. 129);

- indakhīlopamo catubbidhamāraparavādiganehi akampiyatthena (SNA.i.201);

- Mārasenam sasenam abhibhuyyāti kilesasenāya anantasenāya ca sasenam anavasittham, catubbidham pi māram abhibhavitvā devaputtamārassā pi hi gunamārane sahāyabhāvūpagamanato kilesā senā ti vuccanti (ItvA.136).

The last quotation seems to indicate that the four Māras are the five Māras less Devaputta Māra.

A few particulars are available about Devaputta Māra:

- Māro ti Vasavattibhūmiyam aññataro dāmarikadevaputto. So hi tam thānam atikkamitukāmam janam yam na sakkoti tam māreti, yam na sakkoti tassa pi maranam icchati, tenā Māro ti vuccati (SNA.i.44);

- Māro yeva pana sattasankhātāya pajāya adhipatibhāvena idha Pajāpatīti adhippeto. So hi kuhim vasatīti? Paranimmittavasavattidevaloke. Tatra hi Vasavattirājā rajjam kāreti. Māro ekasmim padese attano parisāya issariyam pavattento rajjapaccante dāmarikarājapittto viya vasatī ti vadanti (MA.i.28);

- so hi Māro opapātiko kāmāvacarissaro, kadāci brahmapārisajjānampi kāye adhimuccitum samattho (Jinālankāra Tīkā, p.217).

In view of the many studies of Māra by various scholars, already existing, it might be worth while here, too, to attempt a theory of Māra in Buddhism, based chiefly on the above data. The commonest use of the word was evidently in the sense of Death. From this it was extended to mean "the world under the sway of death" (also called Māradheyya - e.g., A.iv.228) and the beings therein. Thence, the kilesas also came to be called Māra in that they were instruments of Death, the causes enabling Death to hold sway over the world. All Temptations brought about by the kilesas were likewise regarded as the work of Death. There was also evidently a legend of a devaputta of the Vasavatti world, called Māra, who considered himself the head of the Kāmāvacara world and who recognized any attempt to curb the enjoyment of sensual pleasures, as a direct challenge to himself and to his authority. As time went on these different conceptions of the word became confused one with the other, but this confusion is not always difficult to unravel.

Various statements are found in the Pitakas connected with Māra, which have, obviously, reference to Death, the kilesas, and the world over which Death and the kilesas hold sway. Thus:

- Those who can restrain the mind and check its propensities can escape the snares of Māra (Dhp. Yamaka, vs. 7).

- He who delights in objects cognizant to the eye, etc., has gone under Māra's sway (S.iv.91).

- He who has attachment is entangled by Māra (S.iii.73).

- Māra will overthrow him who is unrestrained in his senses, immoderate in his food, idle and weak (Dhp. Yamaka, vs. 8).

- By attaining the Noble Eightfold Path one can be free from Māra (Dhp. vs. 40).

- The Samyutta (i. 135) records a conversation between Māra and Vajirā. She has attained arahantship, and tells Māra: "There is no satta here who can come under your control; there is no being but a mere heap of sankhāras (suddhasankhārarapuñja).

The later books, especially the Nidānakathā of the Jātaka Commentary (J.i.71ff.; cp. MA.i.384) and the Buddhavamsa Commentary (p. 239f), contain a very lively and detailed description of the temptation of the Buddha by Māra, as the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree immediately before his Enlightenment. These accounts describe how Māra, the devaputta, seeing the Bodhisatta seated, with the firm resolve, of becoming a Buddha, summoned all his forces and advanced against him. These forces extended to a distance of twelve yojanas to the front of the Bodhisatta, twelve to the back, and nine each to the right and to the left. Māra himself, thousand armed, rode on his elephant, Girimekhala, one hundred and fifty leagues in height. His followers assumed various fearsome shapes and were armed with dreadful weapons. At Māra's approach, all the various Devas, Nāgas and others, who were gathered round the Bodhisatta singing his praises and paying him homage, disappeared in headlong flight. The Bodhisatta was left alone, and he called to his assistance the ten pārami which he had practiced to perfection.

Māra's army is described as being tenfold, and each division of the army is described, in very late accounts (especially in Singhalese books), with great wealth of detail. Each division was faced by the Buddha with one pāramī and was put to flight. Māra's last weapon was the Cakkāvudha (??). But when he hurled it at the Buddha it stood over him like a canopy of flowers. Still undaunted, Māra challenged the Buddha to show that the seat on which he sat was his by right. Māra's followers all shouted their evidence that the seat was Māra's. The Buddha, having no other witness, asked the Earth to bear testimony on his behalf, and the Earth roared in response. Māra and his followers fled in utter rout, and the Devas and others gathered round the Buddha to celebrate his victory. The sun set on the defeat of Māra. This, in brief, is the account of the Buddha's conquest of Māra, greatly elaborated in later chronicler, and illustrated in countless Buddhist shrines and temples with all the wealth of riotous colour and fanciful imagery that gifted artists could command.

That this account of the Buddha's struggle with Māra is literally true, none but the most ignorant of the Buddhists believe, even at the present day. The Buddhist point of view has been well expressed by Rhys Davids (Article on Buddha in the Ency. Brit.). We are to understand by the attack of Māra's forces, that all the Buddha's

"old temptations came back upon him with renewed force. For years he had looked at all earthly good through the medium of a philosophy which had taught him that it, without exception, carried within itself the seeds of bitterness and was altogether worthless and impermanent; but now, to his wavering faith, the sweet delights of home and love, the charms of wealth and power, began to show themselves in a different light and glow again with attractive colours. He doubted and agonized in his doubt, but as the sun set, the religious side of his nature had won the victory and seems to have come out even purified from the struggle."

There is no need to ask, as does Thomas, with apparently great suspicion (Thomas, op. cit., 230), whether we can assume that the elaborators of the Māra story were recording "a subjective experience under the form of an objective reality," and did they know or think that this was the real psychological experience which the Buddha went through? The living traditions of the Buddhist countries supply the adequate answer, without the aid of the rationalists. The epic nature of the subject gave ample scope for the elaboration so dear to the hearts of the Pāli rhapsodists.

The similar story among Jains, as recorded in their commentarial works - e.g., in the Uttarādhyayana Sūtra (ZDMG. vol. 49 (1915), 321ff ) - bears no close parallelism to the Buddhist account, but only a faint resemblance.

There is no doubt that the Māra legend had its origin in the Padhāna Sutta. There Māra is represented as visiting Gotama on the banks of the Nerañjarā, where he is practicing austerities and tempting him to abandon his striving and devote himself to good works. Gotama refers to Māra's army as being tenfold. The divisions are as follows:

- the first consists of the Lusts;

- the second is Aversion;

- the third Hunger and Thirst;

- the fourth Craving;

- the fifth Sloth and Indolence;

- the sixth Cowardice;

- the seventh Doubt;

- the eighth Hypocrisy and Stupidity;

- Gains, Fame, Honour and Glory falsely obtained form the ninth; and

- the tenth is the Lauding of oneself and the Contemning of others.

"Seeing this army on all sides," says the Buddha, "I go forth to meet Māra with his equipage (savāhanam). He shall not make me yield ground. That army of thine, which the world of devas and men conquers not, even that, with my wisdom, will I smite, as an unbaked earthen bowl with a stone." Here we have practically all the elements found in the later elaborated versions.

The second part of the Padhāna Sutta (SN. vs. 446f.; cf. S.i.122) is obviously concerned with later events in the life of Gotama, and this the Commentary (SNA.ii.391) definitely tells us. After Māra had retired discomfited, he followed the Buddha for seven years, watching for any transgression on his part. But the quest was in vain, and, "like a crow attacking a rock," he left Gotama in disgust. "The lute of Māra, who was so overcome with grief, slipped from his arm. Then, in dejection, the Yakkha disappeared thence." This lute, according to the Commentary (SNA.ii.394), was picked up by Sakka and given to Pañcasikha. Of this part of the Sutta, more anon.

The Samyutta Nikāya (S.i.124f.; given also at Lal. 490 (378); cp. A.v.46; see also DhA.iii.195f ) also contains a sutta ("Dhītaro" Sutta) in which three daughters of Māra are represented as tempting the Buddha after his Enlightenment. Their names are Tanhā, Arati and Ragā, and they are evidently personifications of three of the ten forces in Māra's army, as given in the Padhāna Sutta. They assume numerous forms of varying age and charm, full of blandishment, but their attempt is vain, and they are obliged to admit defeat.

Once Māra came to be regarded as the Spirit of Evil all temptations of lust, fear, greed, etc., were regarded as his activities, and Māra was represented as assuming various disguises in order to carry out his nefarious plans. Thus the books mention various occasions on which Māra appeared before the Buddha himself and his disciples, men and women, to lure them away from their chosen path.

Soon after the Buddha's first vassa, Māra approached him and asked him not to teach the monks regarding the highest emancipation, he himself being yet bound by Māra's fetters. But the Buddha replied that he was free of all fetters, human and divine (Vin.i.22).

On another occasion Māra entered into the body of Vetambarī and made him utter heretical doctrines. (S.i.67; cp. DhA.iv.141, where Māra asks the Buddha about the further shore.

In the Brahmanimantanika Sutta (M.i.326) Māra is spoken of as entering the hearts even of the inhabitants, of the Brahma world).

The Māra Samyutta (S.4) contains several instances of Māra's temptations of the Buddha by assailing him with doubts as to his emancipation, feelings of fear and dread, appearing before him in the shape of an elephant, a cobra, in various guises beautiful and ugly, making the rocks of Gijjhakūta fall with a crash; by making him wonder whether he should ever sleep; by suggesting that, as human life was long, there was no need for haste in living the good life; by dulling the intelligence of his hearers (E.g., at Ekasalā; cf. Nigrodha and his fellow Paribbājakas, D.iii.58).

Once, when the Buddha was preaching to the monks, Māra came in the guise of a bullock and broke their bowls, which were standing in the air to dry; on another occasion he made a great din so that the minds of the listening monks were distracted. Again, when the Buddha went for alms to Pañcasālā, he entered into the brahmin householders and the Buddha had to return with empty bowl. Māra approached the Buddha on his return and tried to persuade him to try once more; this was, says the Commentary, a ruse, that he might inspire insult and injury in addition to neglect. But the Buddha refused, saying that he would live that day on pīti, like the Abhassara gods. The incident is related at length in SA.i.140f. and DhA.iii.257f.; the Commentaries (e.g., Sp.i.178f.) state that the difficulty experienced by the Buddha and his monks in obtaining food at Verañja was also due to the machinations of Māra.

Again, as the Buddha was preaching to the monks on Nibbāna, Māra came in the form of a peasant and interrupted the sermon to ask if anyone had seen his oxen. His desire was to make the cares of the present life break in on the calm and supramundane atmosphere of the discourse on Nibbāna. On another occasion he tempted the Buddha with the fascination of exercising power that he might rescue those suffering from the cruelty of rulers. Once, at the Sākyan village of Sīlavatī, he approached the monks who were bent on study, in the shape of a very old and holy brahmin, and asked them not to abandon the things of this life, in order to run after matters involving time. In the same village, he tried to frighten Samiddhi away from his meditations. Samiddhi sought the Buddha's help and went back and won arahantship. (Cp. the story of Nandiya Thera. Buddhaghosa says (DA.iii.864) that when Sūrambattha, after listening to a sermon of the Buddha, had returned home, Māra visited him there in the guise of the Buddha and told him that what he (the Buddha) had preached to him earlier was false. Sūrambattha, though surprised, could not be shaken in his faith, being a sotāpanna). Māra influenced Godhika to commit suicide and tried to frighten Rāhula in the guise of a huge elephant. (DhA.iv.69f ). In the account of Godhika's suicide (S.i.122) there is a curious statement that, after Godhika died, Māra went about looking for his (Godhika's) consciousness (patisandhicitta), and the Buddha pointed him out to the monks, "going about like a cloud of smoke." Later, Māra came to the Buddha, like a little child (khuddadārakavannī), (SA.i.145) holding a vilva lyre of golden color, and he questioned the Buddha about Godhika. (This probably refers to some dispute which arose among the monks regarding Godhika's destiny.)

The books mention many occasions on which Māra assumed various forms under which to tempt bhikkhunīs, often in lonely spots - e.g., ālavikā, Kisāgotamī, Somā, Vijayā, Uppalavantnā, Cālā, Upacālā, Sisūpacālā, Selā, Vajirā and Khemā. To the same category of temptations belongs a story found in late commentaries (J.i.63): when Gotama was leaving his palace on his journey of Renunciation, Māra, here called Vasavattī, appeared before him and promised him the kingdom and the whole world within seven days if he would but turn back. Māra's temptations were not confined to monks and nuns; he tempted also lay men and women and tried to lure them from the path of goodness - e.g., in the story of Dhaniya and his wife. (SNA.i.44; see also J.i.231f).

Mention is made, especially in the Mahā Parinibbāna Sutta, of several occasions on which Māra approached the Buddha, requesting him to die; the first of these occasions was under the Ajapala Banyan tree at Uruvelā, soon after the Enlightenment, but the Buddha refused to die until the sāsana was firmly established. Can it be that here we have the word Māra used in the sense of physical death (Maccumāra), and that the occasions referred to were those on which the Buddha felt the desire to die, to pass away utterly, to "lay down the burden"? Perhaps they were moments of physical fatigue, when he lay at death's door, for we know (see Gotama) that the six years he spent in austerities made inroads on his health and that he suffered constantly from muscular cramp, digestive disorders and headache. (It is true that in the Mahāsaccaka Sutta (M.i.240ff.), which contains an account of the events leading up to the Enlightenment, there is no mention whatsoever of any temptation by Mara, nor is there any mention of the Bodhi tree. But to argue from this, that such events did not form part of the original story, might be to draw unwarranted inferences from an argumentum e silentio.) At Beluvagāma, shortly before he finally decided to die, we are told (D.ii.99; cp. Dvy. 203) that "there fell upon him a dire sickness, and sharp pains came upon him even unto death." But the Buddha conquered the disease by a strong effort of his will because he felt it would not be right for him to die without addressing his followers and taking leave of the Order. Compare with this Māra's temptation of the Buddha at Maddakucchi (q.v.), when he laid suffering from severe pain after the wounding of his foot by a splinter. It may have been the physical weariness, above referred to, which at first made the Buddha reluctant to take upon himself the great exertions which the propagation of his Dhamma would involve (e.g., Vin.i.4f). We know of other arahants who actually committed suicide in order to escape being worried by physical ills - e.g., Godhika, Vakkali, Channa. When their suicide was reported to the Buddha, he declared them free from all blame.

Can it be, further, that with the accounts of Māra, as the personification of Evil, came to be mixed legends of an actual devaputta, named Māra, also called Vasavatti, because he was an inhabitant of the Paranimmita Vasavatti deva world? Already in the Anguttara Nikāya, Māra is described (aggo ādhipateyyānam iddhiyā yasasā jalam) as the head of those enjoying bliss in the Kāmāvacara worlds and as a dāmarika devaputta (as mentioned earlier). A.ii.17. Even after the Buddha's death Māra was regarded as wishing to obstruct good works. Thus, at the enshrinement of the Buddha's relics in the Mahā Thūpa, Indagutta Thera (by supernatural power) made a parasol of copper to cover the universe, in order that it might ward off the attentions of Māra (Mhv.xxxi.85).

Can it be that ancient legends represented him as looking on with disfavour at the activities of the Buddha? Buddhaghosa says (MA.i.533) that Māradevaputta, having dogged the Buddha's footsteps for seven years, and having found no fault in him, came to him and worshipped him. Is it, then, possible that some of the conversations, which the Buddha is reported to have had with Māra - e.g., in the second part of the Padhāna Sutta (see above) were originally ascribed to a real personage, designated as Māradevaputta, and later confused with the allegorical Māra? This suggestion gains strength from a remark found in the Māratajjaniya Sutta (M.i.333; cp. D.iii.79) uttered by Moggallāna, that he too had once been a Māra, Dūsī by name; Kālā was his sister's name, and the Māra of the present age was his nephew. In the sutta, Dūsī is spoken of as having been responsible for many acts of mischief, similar to those ascribed to the Māra of Gotama's day. According to the sutta, Māradevaputta was evidently regarded as a being of great power, with a strong bent for mischief, especially directed against holy men. This suggestion is, at all events, worthy of further investigation. See also Mārakāyikā deva.

Māra bears many names in Pāli Literature, chief of them being Kanha, Adhipati, Antaka, Namuci and Pamattabandhu. (MNid.ii.489; for their explanation see MNidA.328; another name of Māra was Pajāpati, MA.i.28). His usual standing epithet is pāpimā, but other words are also used, such as anatthakāma, ahitakāma, and ayogakkhemakāma (E.g., M.i.118).

Māra is called Namuci because none can escape him Namucī ti Māro; so hi attano visayā nikkhamitukāme devamanusse na muñcati antarāyam tesam karoti tasma Namucī ti vuccati (SNA.ii.386). In the Mahāsamaya Sutta, Namuci is mentioned among the Asuras as being present in the assembly. D.ii.259; elsewhere in the same sutta (p. 261f.) it is said that when all the devas and others had assembled to hear the Buddha preach, Mara came with his "swarthy host" and attempted to blind the assembly with thoughts of lust, etc. But the Buddha, seeing him, warned his followers against him and Māra had to depart unsuccessful. At the end of the sutta, four lines are traditionally ascribed to Māra. They express admiration of the Buddha and his followers. In this sutta Māra is described as mahāsena (having a large army).

The Commentary explains (DA.ii.689) that Namuci refers to Māradevaputta and accounts for his presence among the Asuras by the fact that he was temperamentally their companion (te pi acchandikā abhabbā, ayam pi tādiso yeva, tasmā dhātuso samsandamāno āgato). Buddhaghosa says (SA.i.133; cp. MNidA. 328) that Māra is so called because he destroys all those who seek to evade him attano visayam atikkamitum patipanne satte māreti ti Māro; he is called Vasavatti (SA.i.158) because he rules all Māro nāma vasavattī sabesam upari vasam vattati.

Kālī (Kālā) is the mother of Māra of the present age. See Kālī (4)."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

2 Brahmā

"Brahmaloka The highest of the celestial worlds, the abode of the Brahmas. It consists of twenty heavens:

- the nine ordinary Brahma-worlds,

- the five Suddhāvāsā,

- the four Arūpa worlds (see loka),

- the Asaññasatta and

- the Vehapphala (e.g., VibhA.521).

All except the four Arūpa worlds are classed among the Rūpa worlds (the inhabitants of which are corporeal). The inhabitants of the Brahma worlds are free from sensual desires (but see the Mātanga Jātaka, (J.497), where Ditthamangalikā is spoken of as Mahābrahmabhariyā, showing that some, at least, considered that Mahābrahmas had wives).

The Brahma world is the only world devoid of women (DhA.i.270); women who develop the jhānas in this world can be born among the Brahmapārisajjā (see below), but not among the Mahābrahmas (VibhA.437f). Rebirth in the Brahma world is the result of great virtue accompanied by meditation (Vsm.415). The Brahmas, like the other celestials, are not necessarily sotāpanna or on the way to complete knowledge (sambodhi-parāyanā); their attainments depend on the degree of their faith in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha. See, e.g., A.iv.76f.; it is not necessary to be a follower of the Buddha for one to be born in the Brahma world; the names of six teachers are given whose followers were born in that world as a result of listening to their teaching (A.iii.371ff.; iv.135ff.).

The Jātakas contain numerous accounts of ascetics who practised meditation, being born after death in the Brahma world (e.g., J.ii.43, 69, 90; v.98, etc.). Some of the Brahmas - e.g., Baka - held false views regarding their world, which, like all other worlds, is subject to change and destruction (M.i.327). When the rest of the world is destroyed at the end of a kappa, the Brahma world is saved (Vsm.415; KhpA.121), and the first beings to be born on earth come from the ābhassara Brahma world (Vsm.417). Buddhas and their more eminent disciples often visit the Brahma worlds and preach to the inhabitants. E.g., M.i.326 f.; ThagA.ii.184ff.; Sikhī Buddha and Abhibhū are also said to have visited the Brahma world (A.i.227f.). The Buddha could visit it both in his mind made body and his physical body (S.v.282f.).

If a rock as big as the gable of a house were to be dropped from the lowest Brahma-world it would take four months to reach the earth travelling one hundred thousand leagues a day. Brahmas subsist on trance, abounding in joy (sappītikajjhāna), this being their sole food. SA.i.161; food and drinks are offered to Mahābrahmā, and he is invited to partake of these, but not of sacrifices (SA.i.158 f.). Anāgāmins, who die before attaining arahantship, are reborn in the Suddhāvāsā Brahma-worlds and there pass away entirely (see, e.g., S.i.35, 60, and Compendium v.10). The beings born in the lowest Brahma world are called Brahma-pārisajjā; their life term is one third of an asankheyya kappa; next to them come the Brahma-purohitā, who live for half an asankheyya kappa; and beyond these are the Mahā Brahmas who live for a whole asankheyya kappa (Compendium, v.6; but see VibhA.519f., where Mahā Brahmās are defined).

The term Brahmakāyikā-devā seems to be used as a class-name for all the inhabitants of the Brahma-worlds (A.i.210; v.76f).

The Mahā Niddesa Commentary (p.109) says that the word includes all the five (?) kinds of Brahmā (sabbe pi pañca vokāra Brahmāno gahitā).

The BuA.p.10 thus defines the word Brahmā: brūhito tehi tehi gunavisesahī ti=Brahmā. Ayam pana Brahmasaddo Mahā-Brahma-brāhmana-Thathāgata mātāpitu-setthādisu dissati.

The Samantapāsādikā (i.131) speaks of a Mahā Brahmā who was a khināsava, living for sixteen thousand kappas. When the Buddha, immediately after his birth, looked around and took his steps northward, it was this Brahmā who seized the babe by his finger and assured him that none was greater than he.

The names of several Brahmās occur in the books - e.g.,

- Tudu

- Nārada

- Ghatikāra

- Baka

- Sanankumāra

- Sahampatī

To these should be added the names of seven Anāgāmīs resident in Avihā and other Brahma worlds

- Upaka

- Phalagandu

- Pukkusāti

- Bhaddiya

- Khandadeva

- Bāhuraggi

- Pingiya

(S.i.35, 60; SA.i.72 etc.).

Baka speaks of seventy two Brahmās, living, apparently, in his world, as his companions (S.i.142).

See also Tissa Brahmā.

These are described as Mahā Brahmās. Mention is also made of Pacceka Brahmās - e.g., Subrahmā and Suddhavāsa (S.i.146f).

Tudu is also sometimes described as a Pacceka Brahmā (e.g., S.i.149). Of the Pacceka Brahmās, Subrahmā and Suddhavāsa are represented as visiting another Brahmā, who was infatuated with his own power and glory, and as challenging him to the performance of miracles, excelling him therein and converting him to the faith of the Buddha. Tudu is spoken of as exhorting Kokālika to put his trust in Sāriputta and Moggallāna (Loc. Cit.)

No explanation is given of the term Pacceka Brahmā. Does it mean Brahmās who dwelt apart, by themselves? Cp. Pacceka-Buddha.

The Brahmās are represented as visiting the earth and taking an interest in the affairs of men. Thus, Nārada descends from the Brahma-world to dispel the heresies of King Angati (J.vi.242f). When the Buddha hesitates to preach his doctrine, because of its profundity, it is Sahampati who visits him and begs him to preach it for the welfare of the world. The explanation given (e.g., at SA.i.155) is that the Buddha waited for the invitation of Sahampati that it might lend weight to his teaching. The people were followers of Brahmā, and Sahampati's acceptance of the Buddha's leadership would impress them deeply.

Sahampatī is mentioned as visiting the Buddha several times subsequently, illuminating Jetavana with the effulgence of his body. It is said that with a single finger he could illuminate a whole Cakkavāla (SA.i.158). Sanankumāra was also a follower of the Buddha. The Brahmās appear to have been in the habit of visiting the deva worlds too, for Sanankumāra is reported as being present at an assembly of the Tāvatimsa gods and as speaking there the Buddha's praises and giving an exposition of his teaching. But, in order to do this, he assumed the form of Pañcasikha (D.ii.211ff).

The books refer (e.g., at D.i.18, where Brahmā is described as vasavattī issaro kattā nimmātā, etc.) to the view held, at the Buddha's time, of Brahmā as the creator of the universe and of union with Brahmā as the highest good, only to be attained by prayers and sacrifices. But the Buddha himself did not hold this view amid does not speak of any single Brahmā as the highest being in all creation. See, however, A.v.59f., where Mahā Brahmā, is spoken of as the highest denizen of the Sahassalokadhātu (yāvatā sahassalokadhātu, Mahā-Brahmā tattha aggam akkhāyati); but he, too, is impermanent (Mahā-Brahmūno pi . . . atthi eva aññathattam, atthi viparināmo).

There are Mahā Brahmās, mighty and powerful (abhibhū anabhibhūto aññadatthudaso vasavattī), but they too, all of them, and their world are subject to the laws of Kamma. E.g., at S.v.410 (Brahmaloko pi āvuso anicco adhuvo sakkāyapariyāpanno sādhāyasmā Brahmalokā cittam vutthāpetvā sakkāyanirodhacittam upasamharāhi). See also A.iv.76f., 104f., where Sunetta, in spite of all his great powers as Mahā Brahmā, etc., had to confess himself still subject to suffering.

To the Buddha, union with Brahmā seems to have meant being associated with him in his world, and this can only be attained by cultivation of those qualities possessed by the Brahmā. But the highest good lay beyond, in the attainment of Nibbāna. Thus in the Tevijjā Sutta; see also M.ii.194f.

The word Brahma is often used in compounds meaning highest and best - e.g., Brahmacariyā, Brahmassara; for details see Brahma in the New Pāli Dictionary."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

| 19. [3.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchiṃ okkanto hoti, cattāro naṃ devaputtā catuddisaṃ [cātuddisaṃ (syā.)] rakkhāya upagacchanti – mā naṃ bodhisattaṃ vā bodhisattamātaraṃ vā manusso vā amanusso vā koci vā viheṭhesī ti. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [3.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn ein Bodhisatta in den Schoß seiner Mutter herabgestiegen ist, dann kommen Göttersöhne, um ihn in den vier Himmelsrichtungen zu schützen: "Nicht soll den Bodhisatta oder die Mutter des Bodhisatta ein Mensch oder ein nichtmenschliches Wesen angreifen." Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

20.

[4.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave,

yadā bodhisatto mātukucchiṃ okkanto hoti, pakatiyā sīlavatī bodhisattamātā hoti,

Ayam ettha dhammatā. |

[4.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine

Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn ein Bodhisatta in den Schoß seiner Mutter

herabgestiegen ist, dann ist die Mutter des Bodhisatta aus ihrer Natur

sittlich, enthält sich1

Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 D.h. sie hält natürlicherweise die fünf Trainingspunkte der Sittlichkeit (sikkhāpada):

- pāṇātipātā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ [birmanische Versionen lesen: veramaṇisikkhāpadaṃ] samādiyāmi

- adinnādānā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi

- kāmesu micchācārā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi

- musāvādā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi

- surāmerayamajjapamādaṭṭhānā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi

| 21. [5.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchiṃ okkanto hoti, na bodhisattamātu purisesu mānasaṃ uppajjati kāmaguṇūpasaṃhitaṃ, anatikkamanīyā ca bodhisattamātā hoti kenaci purisena rattacittena. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [5.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn ein Bodhisatta in den Schoß seiner Mutter herabgestiegen ist, dann entsteht in ihr kein sinnliches Verlangen nach Männern; und kein Mann kann die Mutter des Bodhisatta mit Liebesverlangen überwältigen. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

| 22. [6.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchiṃ okkanto hoti, lābhinī bodhisattamātā hoti pañcannaṃ kāmaguṇānaṃ. Sā pañcahi kāmaguṇehi samappitā samaṅgībhūtā paricāreti. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [6.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn ein Bodhisatta in den Schoß seiner Mutter herabgestiegen ist, dann erfährt die Mutter die Freuden der fünf Sinne. Ihr werden die Freuden der fünf Sinne zuteil und sie erfreut sich ihrer ganz. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

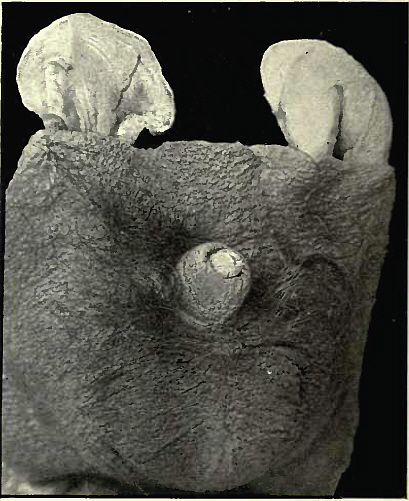

| 23. [7.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchiṃ okkanto hoti, na bodhisattamātu kocideva ābādho uppajjati. Sukhinī bodhisattamātā hoti akilantakāyā, bodhisattañca bodhisattamātā tirokucchigataṃ passati sabbaṅgapaccaṅgiṃ ahīnindriyaṃ. Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, maṇi veḷuriyo subho jātimā aṭṭhaṃso suparikammakato accho vippasanno anāvilo sabbākārasampanno. Tatrāssa [tatrassa (syā.)] suttaṃ āvutaṃ nīlaṃ vā pītaṃ vā lohitaṃ vā odātaṃ vā paṇḍusuttaṃ vā. Tam enaṃ cakkhumā puriso hatthe karitvā paccavekkheyya – ayaṃ kho maṇi veḷuriyo subho jātimā aṭṭhaṃso suparikammakato accho vippasanno anāvilo sabbākārasampanno. Tatridaṃ suttaṃ āvutaṃ nīlaṃ vā pītaṃ vā lohitaṃ vā odātaṃ vā paṇḍusuttaṃ vā’ti. Evameva kho, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchiṃ okkanto hoti, na bodhisattamātu kocideva ābādho uppajjati, sukhinī bodhisattamātā hoti akilantakāyā , bodhisattañca bodhisattamātā tirokucchigataṃ passati sabbaṅgapaccaṅgiṃ ahīnindriyaṃ. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [7.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn ein Bodhisatta in den Schoß seiner Mutter herabgestiegen ist, dann befällt keinerlei Krankheit die Mutter des Bodhisatta. Die Mutter des Bodhisatta ist glücklich, ihr Leib ist ohne Last. Die Mutter des Bodhisatta sieht den Bodhisatta durch ihren Schoß, wie er alle Glieder und alle Sinnesorgane1 besitzt. Es ist, Mönche, wie ein schöner, echter, achteckiger, gut bearbeiteter, klarer, ganz klarer, schmutzfreier, in jeder Hinsicht vollkommener Beryll2; dieser umhüllt eine blaue, gelbe, rote, weiße oder fahle Schnur; wie wenn ein sehender Mann diesen Beryll in die Hand nimmt und ihn betrachtet: "Dies ist ein schöner, echter, achteckiger, gut bearbeiteter, klarer, ganz klarer, schmutzfreier, in jeder Hinsicht vollkommener Beryll; dieser umhüllt eine blaue, gelbe, rote, weiße oder fahle Schnur", ebenso, Mönche, sieht die Mutter des Bodhisatta, wenn der Bodhisatta in ihren Schoß herabgestiegen ist, den Bodhisatta durch ihren Schoß, wie er alle Glieder und alle Sinnesorgane besitzt. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 sabbaṅgapaccaṅgiṃ ahīnindriyaṃ - wie er alle Glieder und alle Sinnesorgane besitzt

Abb.: Im Gegensatz zu einem normalen Embryo/Fetus - Abb.: in der

9. Schwangerschaftswoche - ist der Bodhisatta von Anfang an ein

vollständiges Menschlein mit voll ausgebildeten Gliedern und Sinnesorganen.

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia]

2 veḷuriya = Beryll [Bezeichnung kommt aus Indien via griechisch βήρυλλος]

Abb.: Indischer Beryll auf Schnur gezogen

[Bildquelle: Payer]

Abb.: Farbloser Beryll (Goshenite), China

[Bildquelle: Orbital Joe. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/orbitaljoe/65693144/. -- Zugriff am 2007-10-08.

--

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Abb.: Beryll (Aquamarin) auf Matrix, Gilgit, Pakistan

[Bildquelle: Orbital Joe. --

http://www.flickr.com/photos/orbitaljoe/65693144/. -- Zugriff am 2007-10-08.

--

![]()

![]()

![]() Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

Creative

Commons Lizenz (Namensnennung, keine kommerzielle Nutzung, keine Bearbeitung)]

"Beryll,, Mineral, besteht aus kieselsaurer Beryllerde mit kieselsaurer Tonerde Be3Al2Si6O18, findet sich in säulenförmigen, hexagonalen Kristallen, eingewachsen oder in Drusen aufgewachsen, sowie in stängeligen Aggregaten, ist mitunter farblos, aber meist grün, auch gelb, blau, selten rosenrot, mit Glasglanz, durchsichtig oder durchscheinend, Härte 7,5–8,0, spez. Gew. 2,7. Der edle Beryll bildet längsgestreifte Säulen von grünen, gelben, blauen Farben und ist am geschätztesten bei smaragdgrüner Färbung (ð Smaragd, s. d.) oder meergrün und blau (Aquamarin). Er findet sich in Gängen und Drusen insbes. granitischer Gesteine, auch im Glimmerschiefer, in sehr klaren Kristallen zu Mursinka im Ural und bei Jekaterinenburg, in riesigen zu Aduntschilon bei Nertschinsk und am Altai (Kristalle bis 1 m lang), ferner in den sogen. Edelsanden in Ostindien, Brasilien, Nordamerika, im Granit in Schottland und auf Elba; er dient als Schmuckstein und wird gewöhnlich mit vielen Facetten geschliffen.

Gemeiner Beryll, weniger durchscheinend, trübe weiß, grau, grün, findet sich im Granit bei Zwiesel, Bodenmais und Tirschenreuth in Bayern, Schlaggenwald in Böhmen, Limoges in Frankreich, auf Elba, in Norwegen, Schweden, am Ural, Altai, in Grafton in New Hampshire (hier 2 m lange, 30 Ztr. schwere Kristalle). Er dient zur Darstellung der Beryllerde.

Da Beryllkristalle sich beim Erwärmen in der Richtung der Hauptachse zusammenziehen und senkrecht zu dieser ausdehnen, so kann man nach einer Zwischenrichtung Stäbe aus ihnen schneiden, die ihre Länge bei Temperaturwechsel nicht verändern. Solche benutzt man zur Anfertigung von Normalmaßstäben.

Orientalischer Beryll, bez. Aquamarin, s. ð Korund.

Aus Beryll ist das Wort »Brille« entstanden."

[Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]

| 24. [8.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, sattāhajāte bodhisatte bodhisattamātā kālaṅkaroti tusitaṃ kāyaṃ upapajjati. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [8.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Sieben Tage nach der Geburt des Bodhisatta stirbt seine Mutter und wird im Tusitahimmel wiedergeboren. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

| 25. [9.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yathā aññā itthikā nava vā dasa vā māse gabbhaṃ kucchinā pariharitvā vijāyanti, na hevaṃ bodhisattaṃ bodhisattamātā vijāyati. Daseva māsāni bodhisattaṃ bodhisattamātā kucchinā pariharitvā vijāyati. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [9.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Während andere Frauen den Fetus neun oder zehn Monate1 in ihrem Leib tragen und dann gebären, gebiert die Mutter des Bodhisatta nicht so: sie trägt den Bodhisatta zehn Monate in ihrem Leib und gebiert dann. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 neun oder zehn Monate

"Die Schwangerschaft dauert von der Befruchtung bis zur Geburt durchschnittlich 267 Tage. Üblicherweise wird die Dauer der Schwangerschaft jedoch ab dem ersten Tag der letzten Menstruation gerechnet, da dies oft die sicherste Bezugsgröße darstellt. Die Berechnung erfolgt mit der Naegelschen Regel, in die außerdem die Dauer des Menstruations-Zyklus einfließt. Die Befruchtung findet nach dieser Rechenweise in der zweiten Schwangerschaftswoche (SSW) statt und geschieht üblicherweise durch Geschlechtsverkehr zwischen Mann und Frau. Die ab dem ersten Tag der letzten Menstruation gerechnete Schwangerschaft dauert durchschnittlich etwa 280 Tage oder 40 Wochen. Traditionell wird die Dauer der Schwangerschaft mit 9 Monaten angegeben. Mediziner nehmen zur Vereinfachung jedoch Monate zu jeweils vier Wochen an (Mondmonate); die Schwangerschaft dauerte demnach 10 Mond-Monate statt 9 Kalendermonate.

Exakt zum berechneten Termin kommen jedoch nur vier Prozent der Kinder zur Welt, innerhalb von einer Woche um den errechneten Geburtstermin herum 26 Prozent und innerhalb von drei Wochen um den errechneten Geburtstermin 66 Prozent. Eine Geburt vor Vollendung der 37. Schwangerschaftswoche wird als Frühgeburt bezeichnet."

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schwangerschaft. -- Zugriff am 2007-10-15]

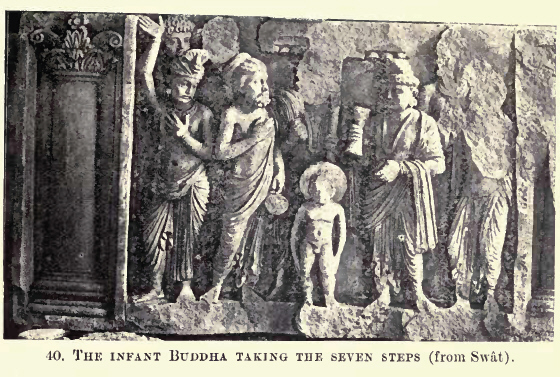

| 26. [10.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yathā aññā itthikā nisinnā vā nipannā vā vijāyanti, na hevaṃ bodhisattaṃ bodhisattamātā vijāyati. Ṭhitāva bodhisattaṃ bodhisattamātā vijāyati. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [10.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Während andere Frauen im Sitzen oder Liegen gebären, gebiert die Mutter des Bodhisatta nicht so: die Mutter des Bodhisatta gebiert den Bodhisatta im Stehen1. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 im Stehen

Abb.: Sidhatta Gotamas Geburt, Gandhara, 2./3. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

| 27. [11.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchimhā nikkhamati, devā paṭhamaṃ paṭiggaṇhanti, pacchā manussā. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [11.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn der Bodhisatta aus dem Schoß seiner Mutter tritt, dann nehmen ihn zuerst Götter1 auf, dann Menschen. Das ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 devā paṭhamaṃ paṭiggaṇhanti

Abb.: Sidhatta Gotamas Geburt, Loriyan Tangai

[Bildquelle: Grünwedel/Gibson, 1901]

| 28. [12.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchimhā nikkhamati, appatto va bodhisatto pathaviṃ hoti, cattāro naṃ devaputtā paṭiggahetvā mātu purato ṭhapenti – attamanā, devi, hohi; mahesakkho te putto uppanno ti. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [12.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn der Bodhisatta aus dem Schoß seiner Mutter tritt, dann berührt der Bodhisatta nicht den Boden. Vier Göttersöhne nehmen ihn entgegen und stellen ihn vor seine Mutter mit den Worten: "Freue dich, Königin; dir ist ein mächtiger Sohn entstanden." Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

| 29. [13.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchimhā nikkhamati, visado va nikkhamati amakkhito udena [uddena (syā.), udarena (katthaci)] amakkhito semhena amakkhito ruhirena amakkhito kenaci asucinā suddho [visuddho (syā.)] visado. Seyyathāpi, bhikkhave, maṇiratanaṃ kāsike vatthe nikkhittaṃ neva maṇiratanaṃ kāsikaṃ vatthaṃ makkheti, nāpi kāsikaṃ vatthaṃ maṇiratanaṃ makkheti. Taṃ kissa hetu? Ubhinnaṃ suddhattā. Evam eva kho, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchimhā nikkhamati, visado va nikkhamati amakkhito, udena amakkhito semhena amakkhito ruhirena amakkhito kenaci asucinā suddho visado. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [13.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn der Bodhisatta aus dem Schoß seiner Mutter tritt, dann tritt er sauber1 heraus, unbefleckt von Wasser, Schleim, Blut oder einer anderen Unreinheit, rein, klar. Es ist, Mönche, wie wenn ein Edelstein auf einem Seidentuch liegt, und weder der Edelstein das Seidentuch befleckt, noch das Seidentuch den Edelstein befleckt. Weswegen? Weil beide rein sind. Ebenso ist es, Mönche, wenn der Bodhisatta aus dem Schoß seiner Mutter tritt: dann tritt er sauber heraus, unbefleckt von Wasser, Schleim, Blut oder einer anderen Unreinheit, rein, klar. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 sauber etc.

Abb.: Im Gegensatz zu normalen Menschen - im Bild: Neugeborenes -

kommt ein Bodhisatta ohne jegliche "Verschmutzung" auf die Welt.

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia]

| 30. [14.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchimhā nikkhamati, dve udakassa dhārā antalikkhā pātubhavanti – ekā sītassa ekā uṇhassa yena bodhisattassa udakakiccaṃ karonti mātu ca. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [14.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn der Bodhisatta aus dem Schoß seiner Mutter tritt, dann erscheinen in der Luft zwei Wasserträgerinnen (oder: Wolken)1, eine mit kaltem Wasser, eine mit heißem. Damit waschen sie den Bodhisatta und seine Mutter. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 udakassa dhārā - Wasserträgerinnen (oder: Wolken)

Abb.: Das Bad des neugeborenen Siddhatta, Swāt

[Bildquelle: Grünwedel/Gibson, 1901]

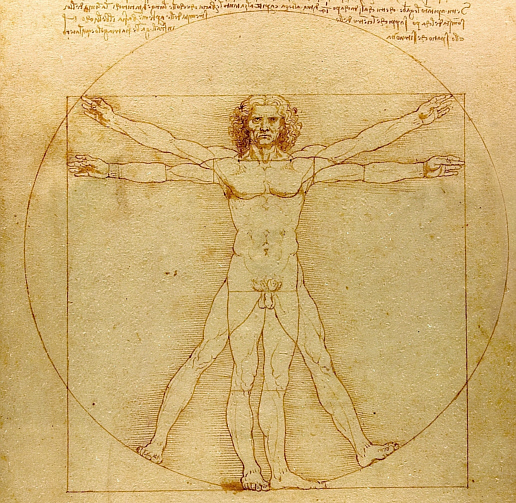

| 31. [15.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, sampati jāto bodhisatto samehi pādehi patiṭṭhahitvā uttarābhimukho [uttarenābhimukho (syā.) uttarenamukho (ka.)] sattapadavītihārena gacchati setamhi chatte anudhāriyamāne, sabbā ca disā anuviloketi, āsabhiṃ vācaṃ bhāsati aggo 'ham asmi lokassa, jeṭṭho 'ham asmi lokassa, seṭṭho 'ham asmi lokassa, ayam antimā jāti, natthidāni punabbhavo ti. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [15.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: der eben geborene Bodhisatta tritt mit den Füßen gleichmäßig auf, blickt nach Norden und macht sieben Schritte1, während ein weißer Schirm über ihn gehalten wird; und er blickt in alle Richtungen und spricht das stiergleiche Wort: "Ich bin der Gipfel der Welt, ich bin der Älteste der Welt. Dies ist meine letzte Geburt, nicht gibt es jetzt eine Wiedergeburt." Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

Erläuterung:

1 sattapadavītihārena - sieben Schritte

Abb.: Die sieben Schritte, Swāt

[Bildquelle. Grünwedel/Gibson, 1901]

Zu den sieben Schritten siehe besonders:

Nāgārjuna: Le traité de la grande vertu de sagesse (Mahāprajñāpāramitāśāstra) / [übersetzt von] Étienne Lamotte. - 5 Bde. - Louvain, 1944-1980. - Tome I, p. 6 - 10 (Anm. 3)

| 32. [16.] Dhammatā esā, bhikkhave, yadā bodhisatto mātukucchimhā nikkhamati, atha sadevake loke samārake sabrahmake sassamaṇabrāhmaṇiyā pajāya sadevamanussāya appamāṇo uḷāro obhāso pātubhavati, atikkammeva devānaṃ devānubhāvaṃ. Yāpi tā lokantarikā aghā asaṃvutā andhakārā andhakāratimisā, yattha pime candimasūriyā evaṃmahiddhikā evaṃmahānubhāvā ābhāya nānubhonti, tatthapi appamāṇo uḷāro obhāso pātubhavati atikkamm eva devānaṃ devānubhāvaṃ. Ye pi tattha sattā upapannā, te pi ten' obhāsena aññamaññaṃ sañjānanti – aññe pi kira, bho, santi sattā idhūpapannā ti. Ayañ ca dasasahassī lokadhātu saṅkampati sampakampati sampavedhati appamāṇo ca uḷāro obhāso loke pātubhavati atikkamm eva devānaṃ devānubhāvaṃ. Ayam ettha dhammatā. | [16.] Dies, Mönche, ist eine Gesetzmäßigkeit: Wenn der Bodhisatta aus dem Schoß der Mutter tritt, dann entsteht in der Welt mit ihren Māra's, Brahmā's, den Asketen und Brahmanen, den Göttern und Menschen ein unermesslich großes Licht, das die Pracht der Götter übertrifft. Sogar in der ungehinderten Dunkelheit zwischen den Welten, die die so mächtigen Mond und Sonne mit ihrem Licht nicht bezwingen können; sogar dort entsteht ein unermesslich großes Licht, das die Pracht der Götter übertrifft. Die Wesen, die dort entstanden sind, erkennen sich in diesem Licht gegenseitig. "Es gibt auch andere Wesen, die hier entstanden sind!" So erzittert und erbebt das 10.000fache Weltall. Und es entsteht in der Welt ein unermesslich großes Licht, das sogar die Pracht der Götter übertrifft. Dies ist dabei eine Gesetzmäßigkeit. |

| Dvattiṃsamahāpurisalakkhaṇā | |

|

33. Jāte kho pana, bhikkhave, vipassimhi kumāre bandhumato rañño paṭivedesuṃ – putto te, deva [deva te (ka.)], jāto, taṃ devo passatū’ti. Addasā kho, bhikkhave, bandhumā rājā vipassiṃ kumāraṃ, disvā nemitte brāhmaṇe āmantāpetvā etadavoca – passantu bhonto nemittā brāhmaṇā kumāra’nti. Addasaṃsu kho, bhikkhave, nemittā brāhmaṇā vipassiṃ kumāraṃ, disvā bandhumantaṃ rājānaṃ etadavocuṃ – attamano, deva, hohi, mahesakkho te putto uppanno, lābhā te, mahārāja, suladdhaṃ te, mahārāja, yassa te kule evarūpo putto uppanno. Ayañ hi, deva, kumāro dvattiṃsamahāpurisalakkhaṇehi samannāgato, yehi samannāgatassa mahāpurisassa dveva gatiyo bhavanti anaññā. Sace agāraṃ ajjhāvasati, rājā hoti cakkavattī dhammiko dhammarājā cāturanto vijitāvī janapadatthāvariyappatto sattaratanasamannāgato. Tassimāni sattaratanāni bhavanti. Seyyathidaṃ – cakkaratanaṃ hatthiratanaṃ assaratanaṃ maṇiratanaṃ itthiratanaṃ gahapatiratanaṃ pariṇāyakaratanam eva sattamaṃ. Parosahassaṃ kho panassa puttā bhavanti sūrā vīraṅgarūpā parasenappamaddanā. So imaṃ pathaviṃ sāgarapariyantaṃ adaṇḍena asatthena dhammena abhivijiya ajjhāvasati. Sace kho pana agārasmā anagāriyaṃ pabbajati, arahaṃ hoti sammāsambuddho loke vivaṭacchado. |

Als aber, Mönche, der

Prinz Vipassī geboren war, meldete man dem König Bandhumā: "König, dir

wurde ein Sohn geboren, der König möge ihn anschauen." Da betrachtete

König Bandhumā den Prinzen Vipassī. Dann ließ er Zeichendeuter-Brahmanen

kommen und sprach zu ihnen: "Die hochwürdigen Zeichendeuter-Brahmanen

mögen den Prinzen betrachten. Da betrachteten die

Zeichendeuter-Brahmanen den Prinzen Vipassī. Danach sprachen sie zu

König Bandhumā: "Freue dich, König, dir wurde ein mächtiger Sohn

geboren. Es ist ein Gewinn für dich, Großkönig, ein großer Gewinn,

Großkönig, dass in deiner Familie ein solcher Sohn geboren wurde; denn

dieser Sohn besitzt die zweiunddreißig Merkmale eines großen Mannes. Ein Großer Mann mit diesen Merkmalen hat zwei Lebensziele als Option, kein anderes:

|

Erläuterung:

1 Weltenherrscher (Cakravartin)

"Cakka-vatti The special name given in the books to a World ruler. The world itself means "Turner of the Wheel," the Wheel (Cakka) being the well known Indian symbol of empire. There are certain stock epithets used to describe a Cakka-vatti:

- dhammiko, dhammarājā, cāturanto (ruler of the four quarters),

- vijitāvī (conqueror),

- janapadatthavāriyappatto (guardian of the people's good), and

- sattaratanasamannāgato (possessor of the Seven Treasures).

More than one thousand sons are his; his dominions extend throughout the earth to its ocean bounds (sāgarapariyantam); and is established not by the scourge, nor by the sword, but by righteousness (adandena asatthena dhammen'eva abhivijiva). Particulars are found chiefly in the Mahāsudassana, Mahāpadāna, Cakkavattisīhanāda, Bālapandita and Ambattha Suttas. See also S.v.98.

From the Mahāpadāna Sutta it would appear that the birth of a Cakka-vatti is attended by the same miracles as that of the birth of a Buddha. A Cakka-vatti's youth is the same as that of Buddha; he, too, possesses on his body the Mahāpurisalakkhanāni, and sooth-sayers are able to predict at the child's birth only that one of two destinies await him.

Of the Seven Treasures of a Cakka-vatti, the Cakkaratana is the chief. When he has traversed the Four Continents:

- Pubbavideha

- Jambudīpa

- Aparagoyāna

- Uttarakuru

accompanied by the Cakkaratana, received the allegiance of all the inhabitants and admonished them to lead the righteous life, he returns to his own native city.

After the Wheel, other Treasures make their appearance:

- first the Elephant, Hatthiratana; it is either the youngest of the Chaddanta-kula or the oldest of the Uposatha-kula.

- Next the Horse, Assaratana, named Valāhaka, all white with crow black head, and dark mane, able to fly through the air.

- Then the Veluriya-gem from Vepullapabbata, with eight facets, the finest of its species, shedding light for a league around.

- This is followed by the Woman, belonging either to the royal family of Madda or of Uttarakuru, desirable in every way, both because of her physical beauty and her virtuous character.

- Then the Treasurer (Gahapati) possessed of marvellous vision, enabling him to discover treasures,

- and then the Adviser (Parināyaka), who is generally the Cakka-vatti's eldest son.

(For descriptions of these see D.ii.174f; DA.ii.624f; MA.ii.941f ).

Judging from the story of Mahāsudassana, who is the typical Cakka-vatti, the World emperor has also four other gifts (iddhi):

- a marvellous figure,

- a life longer than that of other men, good health,

- and popularity with all classes of his subjects.

- The perfume of sandalwood issues from his mouth, while his body is like a lily.

When the Cakka-vatti is about to die the Wheel slips down from its place and sinks down slightly. When the king sees this he leaves the household life, and retires into homelessness, to taste the joys of contemplation, having handed over the kingdom to his eldest son. At the king's death, the Elephant, the Horse and the Gem return to where they came from, the Woman loses her beauty, the Treasurer his divine vision, and the Adviser his efficiency (DA.ii.635).

Cakka-vattis are rare in the world, and are born in kappas in which Buddhas do not arise (SA.iii.131). The Cakkavattisīhanāda Sutta, however, gives the names of seven who succeeded one another. In the case of each of them the Wheel disappeared, but, when his successor practised the Ariyan duty of a Cakka-vatti, honouring the Dhamma and following it to perfection, the Wheel re-appeared. In the case of the seventh his virtues gradually disappeared through forgetfulness; crime spread, among his subjects, and the Wheel vanished for ever.

In the earlier literature the term Cakka-vatti seems to have been reserved for a World ruler; but later three sorts of Cakka-vattis are mentioned:

- cakkavāla- or cāturanta-cakkavatti (ruling over the four continents),

- dīpa-cakkavatti (ruling over one), and

- padesacakkavatti (over part of one). (DA.i.249)

No woman can become a Cakka-vatti (the reasons for this are given at AA.i.254).

A Cakka-vatti is, as worthy of a thūpa as a Buddha. D.ii.143."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

2 Radjuwel (cakkaratana)

"Cakkaratana One of the seven treasures of a Cakkavatti. When a Cakkavatti is born into the world, the Cakkaratana appears before him from the Cakkadaha, travelling through the air (J.iv.232, but see Vepulla).

The Cakkaratana is the Cakkavatti's chief symbol of office; on its appearance before him, he sprinkles it with water and asks it to travel to the various quarters of the world, winning them for him. This the Cakkaratana does, carrying with it through the air the Cakkavatti with his fourfold army. Wherever the Cakkaratana halts, all the chiefs of that quarter acclaim the Cakkavatti as their overlord and declare their allegiance to him. Having thus traversed the four quarters of the earth, it returns to the Cakkavatti's capital, and remains fixed as an ornament on the open terrace in front of his inner apartments (D.ii.173f; M.iii.173ff).

The Commentaries (E.g., DA.ii.617ff; MA.ii.942ff) contain lengthy descriptions of the Cakkaratana: it is shaped like a wheel, its nave is of sapphire, the centre of which shines like the orb of the moon, and round it is a band of silver. It has one thousand spokes, each ornamented with various decorations; its tyre is of bright coral; within every tenth spoke is a coral staff, hollow inside, which produces the sounds of the fivefold musical instruments when blown upon by the wind. On the staff is a white parasol, on either side of which are festoons of flowers. When the wheel moves, it appears like three wheels moving one within the other.

When a Cakkavatti dies or leaves the world, the Cakkaratana disappears from the sight of men for seven days; it gives warning of a Cakkavatti's impending death by slipping from its place some time before the event (D.iii.59f.; MA.ii.885). When his successor has lived righteously for seven days, it reappears (D.iii.64).

It is the most precious and the most honoured thing in the world. UdA.356."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

| 34. Katamehi cāyaṃ, deva, kumāro dvattiṃsamahāpurisalakkhaṇehi samannāgato, yehi samannāgatassa mahāpurisassa dveva gatiyo bhavanti anaññā. Sace agāraṃ ajjhāvasati, rājā hoti cakkavattī dhammiko dhammarājā cāturanto vijitāpī janapadatthāvariyappatto sattaratanasamannāgato. Tassimāni sattaratanāni bhavanti . Seyyathidaṃ – cakkaratanaṃ hatthiratanaṃ assaratanaṃ maṇiratanaṃ itthiratanaṃ gahapatiratanaṃ pariṇāyakaratanameva sattamaṃ. Parosahassaṃ kho panassa puttā bhavanti sūrā vīraṅgarūpā parasenappamaddanā. So imaṃ pathaviṃ sāgarapariyantaṃ adaṇḍena asatthena dhammena abhivijiya ajjhāvasati. Sace kho pana agārasmā anagāriyaṃ pabbajati, arahaṃ hoti sammāsambuddho loke vivaṭacchado. | Welche zweiunddreißig Merkmale eines Großen Mannes (mahāpurisa)1 besitzt dieser Prinz? |

Erläuterung:

1 Großen Mannes (mahāpurisa)

Abb.: Der Bodhisatta Siddhattha, Gandhara, 2./3. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle. Wikipedia]

Abb.: Buddha Gautama., Gandhara, 1./2. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

"Mahāpurisa The name given to a Great Being, destined to become either a Cakka-vatti or a Buddha. He carries on his person the following thirty two marks (Mahāpurisalakkhanāni) (these are given at D.ii.17f.; iii.142ff.; M.ii.136f ):

[...]

The theory of Mahāpurisa is pre Buddhistic. Several passages in the Pitakas (E.g., D.i.89, 114, 120; A.i.163; M.ii.136; SN.vs.600, 1000, etc.) mention brahmins as claiming that this theory of the Mahāpurisa and his natal marks belonged to their stock of hereditary knowledge. The Buddhists, evidently, merely adopted the brahmin tradition in this matter as in so many others. But they went further. In the Lakkhana Sutta (D.iii.142ff) they sought to explain how these marks arose, and maintained that they were due entirely to good deeds done in a former birth and could only be continued in the present life by means of goodness. Thus the marks are merely incidental; most of them are so absurd, considered as the marks of a human being, that they are probably mythological in origin, and a few of them seem to belong to solar myths, being adaptations to a man, of poetical epithets applied to the sun or even to the personification of human sacrifice. Some are characteristic of human beauty, and one or two may possibly be reminiscences of personal bodily peculiarities possessed by some great man, such as Gotama himself.

Apart from these legendary beliefs, the Buddha had his own theory of the attributes of a Mahāpurisa as explained in the Mahāpurisa Sutta (S.v.158) and the Vassakāra Sutta (A.ii.35f).

Buddhaghosa says (MA.ii.761) that when the time comes for the birth of a Buddha, the Suddhāvāsa Brahmās visit the earth in the guise of brahmins and teach men about these bodily signs as forming part of the Vedic teaching so that thereby auspicious men may recognize the Buddha. On his death this knowledge generally vanishes. He defines a Mahāpurisa as one who is great owing to his panidhi, samādāna, ñāna and karunā. A Mahāpurisa can be happy in all conditions of climate. DA.ii.794.

Bāvarī had three Mahāpurisalakkhanā; he could touch his forehead with his tongue, he had a mole between his eyebrows (unnā), and his privacies were contained within a sheath. SN.vs.1022."

[Quelle: Malalasekera, G. P. <1899 - 1973>: Dictionary of Pāli proper names. -- Nachdruck der Ausgabe 1938. -- London : Pali Text Society, 1974. -- 2 vol. -- 1163, 1370 S. -- ISBN 0860132692. -- s. v.]

|

35.

|

|

1 pādatalesu cakkāni - an den Fußsohlen hat er in jeder Hinsicht vollkommene Räder mit tausend Speichen, mit Radkranz und Nabe

Abb.: "Fußabdruck" Gotamas, Gandhara, 1. Jhdt. n. Chr.

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

2 eṇi-Antilope: "eṇa-Antilopen: Petersburger Wörterbuch: "eine Antilopenart (schwarz und mit kurzen Beinen)"

zu indischen Antilopen/Gazellen siehe:

Carakasaṃhitā: Ausgewählte Texte aus der Carakasaṃhitā / übersetzt und erläutert von Alois Payer <1944 - >. -- Anhang B: Tierbeschreibungen. -- Antilopinae. -- URL: http://www.payer.de/ayurveda/tiere/antilopinae.htm

Abb.: Antilope cervicapra - Blackbuck -

Hirschziegenantilope, Nannaj bei Solapur (सोलापूर), Maharashtra (महाराष्ट्र)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia]

3 seine Schamteile sind in einem "Schatzkästchen": d.h. er ist phänotypisch ein Zwitter (Transsexueller), wenn auch in Wirklichkeit ein zeugungsfähiger Mann

Abb.: Schamteile in einem "Schatzkästchen"?:

abnormal kleiner Penis, unvollständiger Cryptorchidismus.

[Bildquelle: Hofmann, Eduard von <1837 - 1897>: Atlas und Grundriss der gerichtlichen Medizin. -- 1908. -- Tafel 1]

4 collyrium-farbig

Collyrium (añjana): eine Antimonverbindung (vermutlich Stibnit) (u.a. zur Herstellung von Augenschminke verwendet)

"Collyrium, Augenschminke der Griechen und Römer, wahrscheinlich identisch mit dem von den Frauen im Orient noch jetzt angewendeten Kochl (Kohol), das aus Spießglanz [Stibnit = Antimonsulfid = Sb2S3] dargestellt und als schwarze Salbe auf die Augenbrauen und Wimpern aufgetragen wird." [Quelle: Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon. -- DVD-ROM-Ausg. Faksimile und Volltext der 6. Aufl. 1905-1909. -- Berlin : Directmedia Publ. --2003. -- 1 DVD-ROM. -- (Digitale Bibliothek ; 100). -- ISBN 3-89853-200-3. -- s.v.]