Zitierweise / cite as:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. -- Fassung vom 2008-07-01s. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen15.htm

Erstmals publiziert:

Überarbeitungen:

Anlass: Lehrveranstaltung FS 2008

©opyright: Dieser Text steht der Allgemeinheit zur Verfügung. Eine Verwertung in Publikationen, die über übliche Zitate hinausgeht, bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Verfassers

Dieser Text ist Teil der Abteilung Sanskrit von Tüpfli's Global Village Library

Falls Sie die diakritischen Zeichen nicht dargestellt bekommen, installieren Sie eine Schrift mit Diakritika wie z.B. Tahoma.

Mottos

Frontispiz zu Johann Jacob Saar: Ostindianische fünfzehnjährige Kriegsdienste,

1672

Auf den Banderolen steht:

Wir sehen und suchen weit

Durch viel Gefährlichkeit

Nicht ohne Krieg und Streit

Die abgelegne Leut

Und ihre reiche Beut

[Bildquelle: a.u.a.O., S. 79]

| Dass dir nach Batavia mit zu fahren nicht gegrauet, Dass du Siam, Indostan, und auch Sina selbst beschauet, Und gesund bist wieder kommen, dies ist gleichwohl eine Tat, Welche bei uns Oberdeutschen billig Preis und Ehre hat: Du erzählest Wunderding' aus Japan und Coromandel, Von der Indianer Pracht, Glauben, Kleidung, Tun und Handel: Doch eines so von allen uns füraus verwundert macht, Nämlich, dass du einen Affen nur heraus gebracht. J. Grob1 |

1 Grob, Johann: Epigramme, nebst e.

Auswahl aus seinen übrigen Gedichten / hrsg. u. eingel. v. Axel Lindquist.

-- Leipzig : Hiersemann, 1929. -- 270 S. -- (Bibliothek des Litterarischen

Vereins in Stuttgart ; 273). -- S. 190. -- Zitiert in: Gelder, Roelof

van: Das ostindische Abenteuer : Deutsche in Diensten der Vereinigten

Ostindischen Kompanie der Niederlande (VOC), 1600 - 1800. -- Hamburg :

Convent, 2004. -- 271 S. : Ill. ; 27 cm. -- (Schriften des Deutschen

Schiffahrtsmuseums ; Bd. 61). -- Originaltitel: Het Oost-Indisch avontuur :

Duitsers in dienst van de VOC (1997). -- Zugleich. Amsterdam, Univ., Diss.,

1997. -- ISBN 3-934613-57-8. -- S. 185

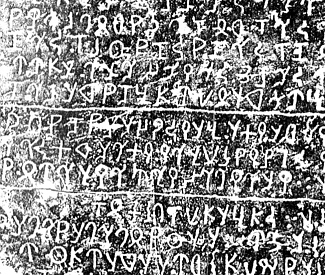

Abb.: Karte von Indien, 16. Jhdt.

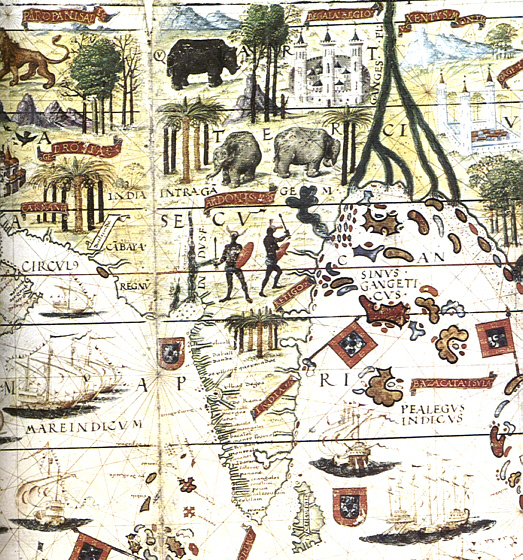

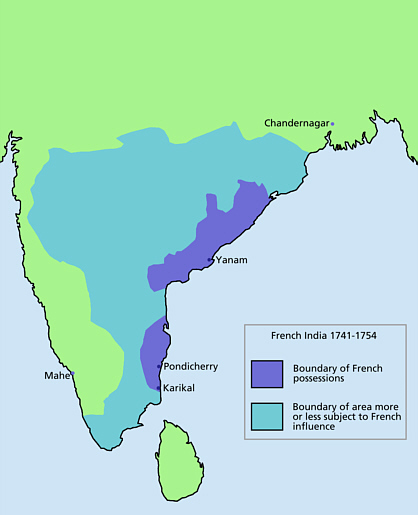

Abb.: Europäische Stützpunkte in Indien 1501 - 1739

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Creative Commons Lizenz:

Attribution ShareAlike 2.5, kein Autor angegeben]

Die Quellen aus dieser Zeit sind unübersehbar. Wichtige Gattungen sind

Sehr vieles ruht in den Nachfolge-Institutionen der Archive der betreffenden Companies und Nationen.

Hier kann nur ein oberflächlicher Einblick gegeben werden.

Abb.: Der Seefahrer war vielen Versuchungen ausgesetzt: Seefahrer zwischen Gott

und Teufel, um 1490

Abb.: Schiffbrüchige: Die Seefahrt nach Indien war äußerst riskant

Abb.: Mit den Räubern und Händlern kamen die Missionare: Jesuit in Südindien

[Bildquelle: The Jesuit in India : adressed to all who are interested in the foreign missions. -- London : Burns & Lambert, 1852. -- Frontispiece]

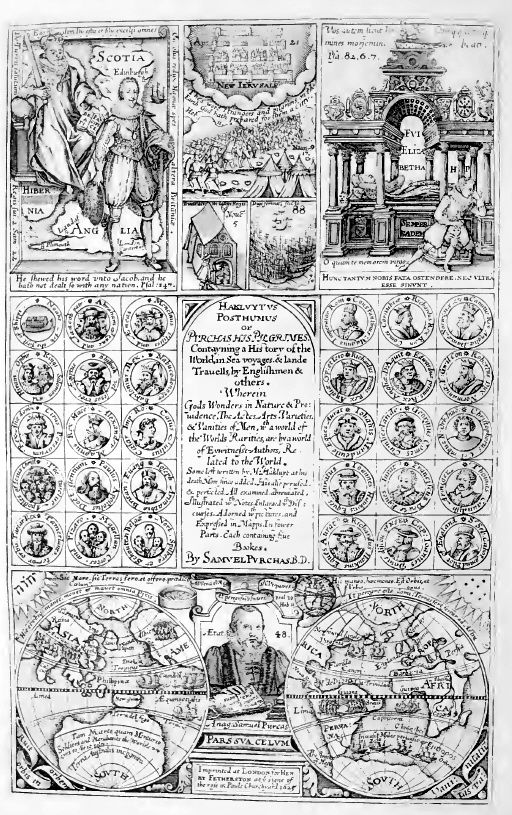

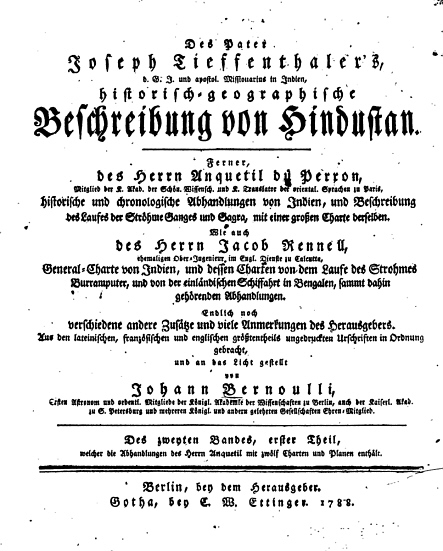

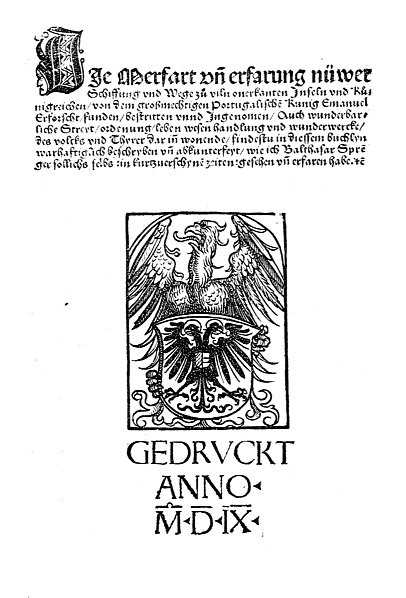

Abb.: Titelblatt

Eine der frühesten (und besten!) Quellensammlungen zur Geschichte der europäischen Exploration und Expansion ist:

Haklvytvs posthumus, or, Pvrchas his Pilgrimes : contayning a history of the world, in sea voyages, & lande-trauells / by Englishmen and others, wherein Gods wonders in nature & prouidence, the actes, arts, varieties & vanities of men, w[i]th a world of the worlds rarities are by a world of eyewitnesse-authors related to the world, some left written by Mr. Hakluyt at his death, more since added, his also perused, & perfected, all examined, abreuiated, illustrated w[i]th notes, enlarged w[i]th discourses, adorned w[i]th pictures, and expressed in mapps, in fower parts, each containing fiue bookes / [compiled] by Samvel Pvrchas, B.D. -- [London] : Imprinted at London for Henry Fetherston at y[e]e signe of the rose in Pauls Churchyard, 1625.. -- 4 Bde. ; 35 cm.

Abb.: Titelblatt von Bd. 1 des Neudrucks von 1905Nachdruck 1905ff. in 20 Bänden: Teilweise Online: http://www.archive.org. -- Zugriff am 2008-06-04. -- Für unsere Zeit sind besonders ergiebig:

Bd. 2, Online: http://www.archive.org/details/hakluytusposthum02purcuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-06-05

Bd. 3, Online: http://www.archive.org/details/hakluytusposthum03purcuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-06-05

Bd. 4, Online: http://www.archive.org/details/hakluytusposthum04purcuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-06-05

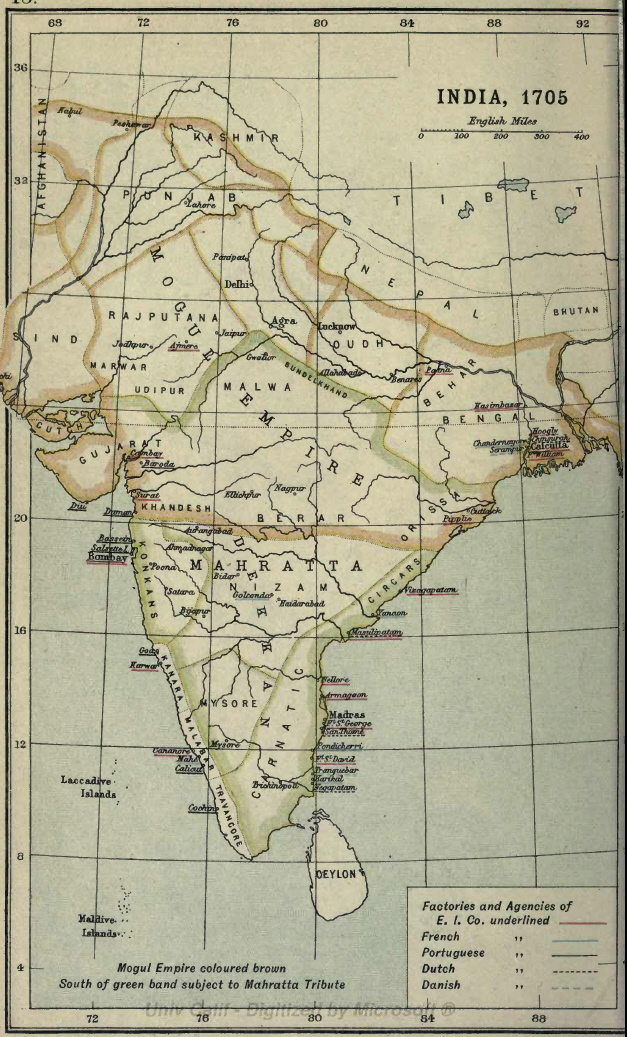

Abb.: Indien, 1705

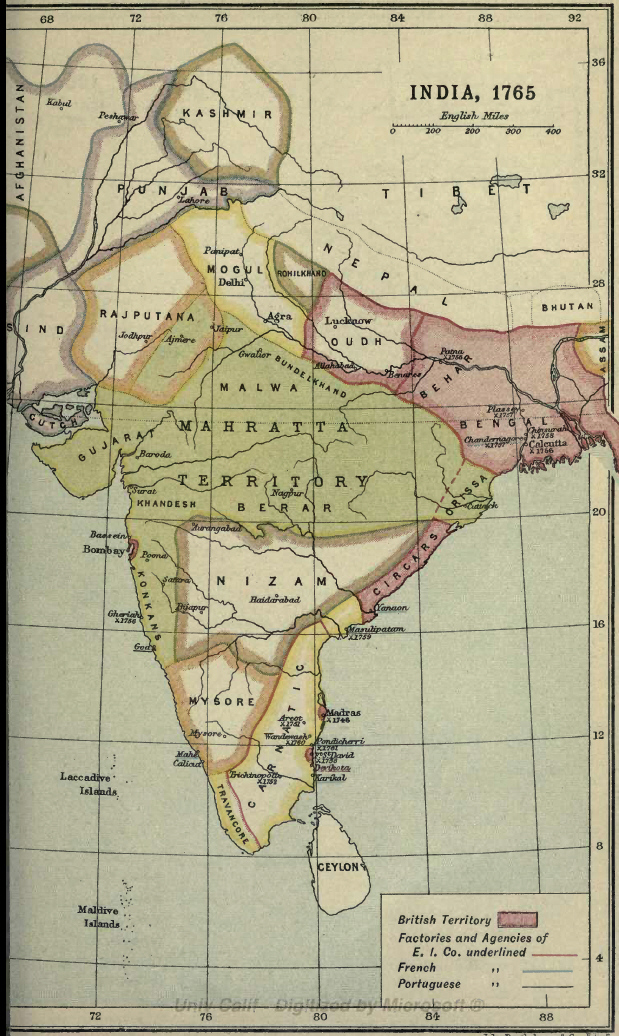

Abb.: Indien, 1765

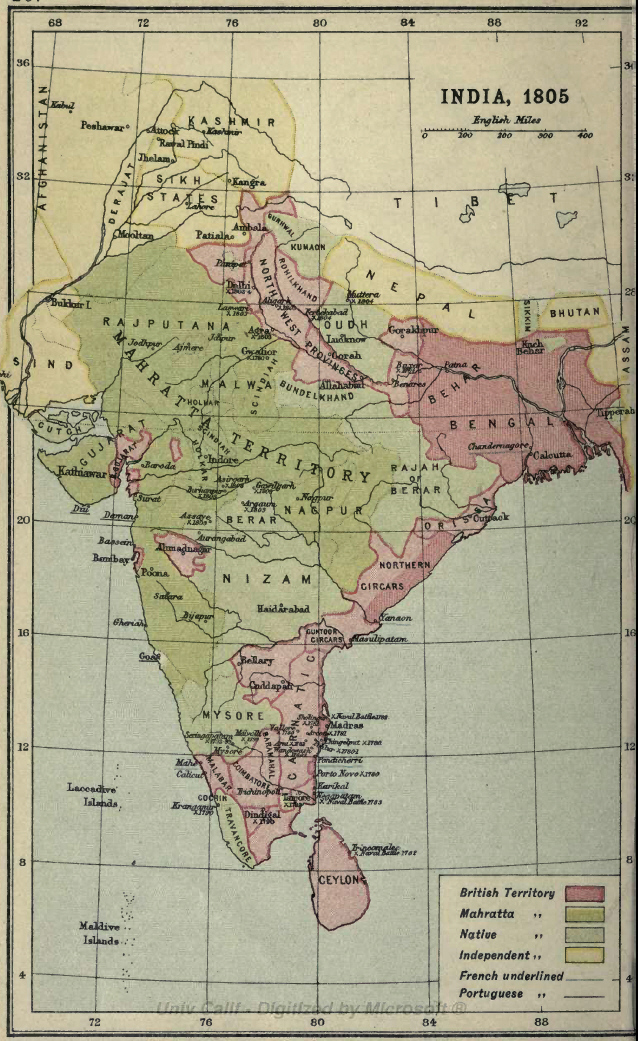

Abb.: Indien, 1805

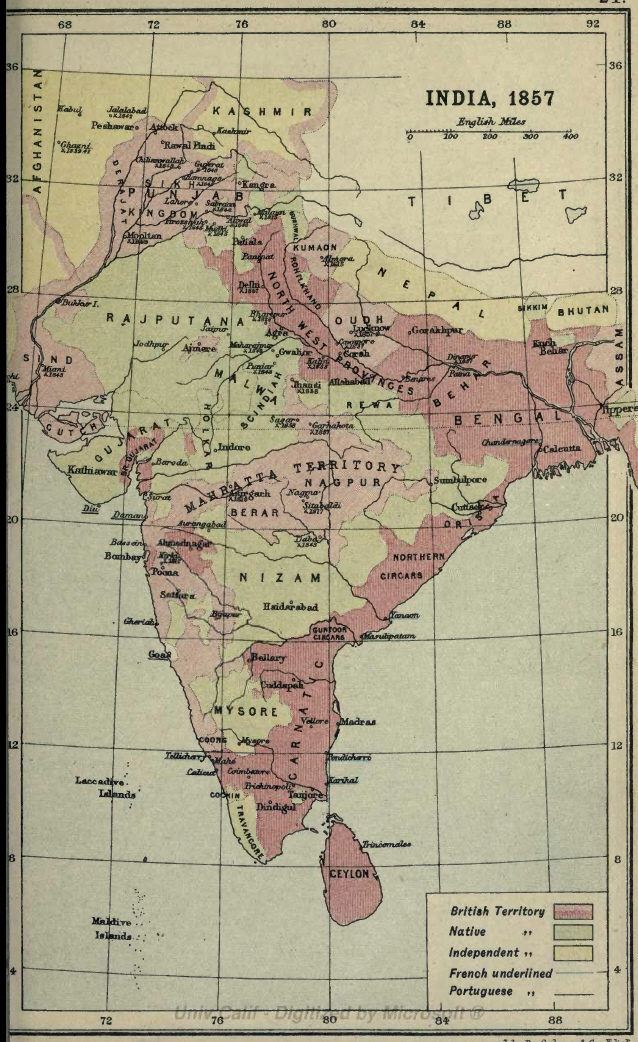

Abb.: Indien, 1857

[Quelle aller vier Karten: Bartholomew, J. G. (John George) <1860-1920>: A literary and historical atlas of Asia. -- London : [1912] -- xi, 226 S. ; Ill. : 18 cm. -- S. 18ff. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/literaryhistoric00bartrich. -- Zugriff am 2008-06-10. -- "Not in cpopyright".]

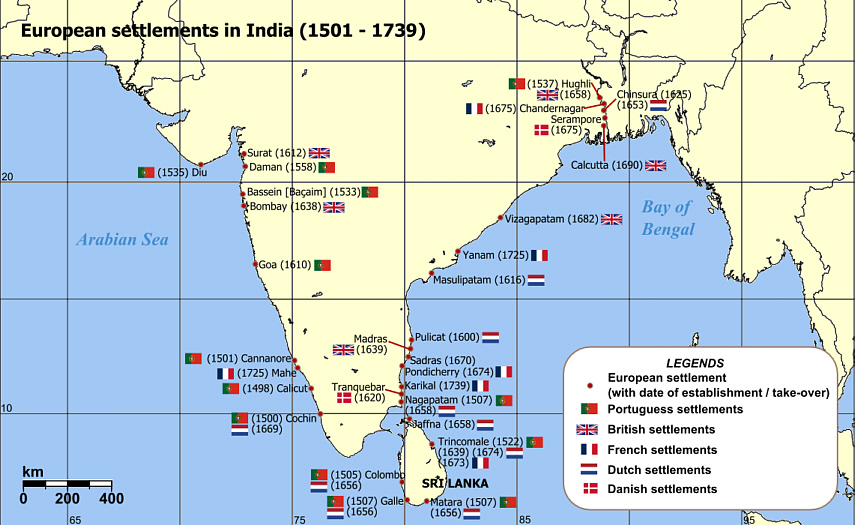

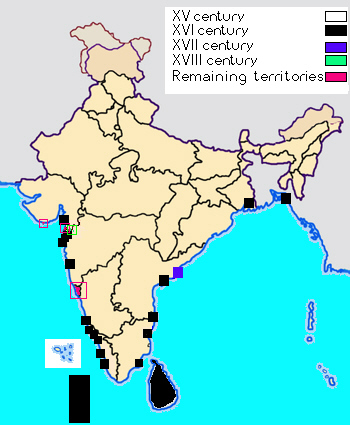

Abb.: Portugiesische Territorien in Indien

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

"Portugiesisch-Indien (auf portugiesisch: Estado da Índia) war eine portugiesische Kolonie in Indien. Portugiesisch-Indien bestand zum Ende der portugiesischen Herrschaft aus drei nicht miteinander verbundenen Territorien, die als Enklaven im britischen Kolonialgebiet lagen. Es waren dies die Gebiete von Goa, der Hauptstadt Portugiesisch-Indiens, Damão und Diu. Bis ins 18. Jahrhundert hinein wurden von Goa aus jedoch sowohl die Besitzungen in Ostafrika als auch die Stützpunkte in Hinterindien mit verwaltet. Geschichte

Im ausgehenden Mittelalter war Indien, auch wenn man in Europa nicht viel über den Subkontinent wusste, als Ursprungsland der äußerst begehrten und sehr kostbaren Gewürze geschätzt. Seit dem Fall Konstantinopels am 29. Mai 1453 an die Osmanen war der Gewürzhandel für christliche europäische Händler nicht mehr zugängig, das Monopol hatten nunmehr die Moslems. Die Suche nach einer von diesen nicht beherrschten Handelsroute wurde deshalb zu einem wichtigen Teil der Politik der europäischen Handelsnationen, besonders Portugals. Da die Moslems die Landroute kontrollierten, konnte dieser Zugang nur auf dem Seeweg gefunden werden, wofür die Südspitze Afrikas umrundet werden musste. Ein erster wichtiger Schritt auf diesem Weg war getan, als Bartolomeu Diaz 1488 das Kap der Guten Hoffnung erreichte. 1498 erreichte Vasco da Gama schließlich Indien auf dem Seewege.

Die Portugiesen begannen ab 1505 in Indien Gebiete zu erobern und dort Handelsstützpunkte einzurichten. Da der Weg nach Portugal beim Fehlen moderner Kommunikationsverbindungen zu weit war, um die indischen Gebiete effektiv von Portugal aus verwalten zu können, richteten die Portugiesen den „Estado da Índia“, den indischen Staat ein, unter der Regentschaft eines vom portugiesischen Monarchen ernannten Vizekönigs, der weitreichende Vollmachten besaß. Unter den ersten beiden Gouverneuren Francisco de Almeida und Afonso de Albuquerque („Alfonso der Große“) wurde die portugiesische Machtposition planmäßig ausgeweitet. 1509 erlangt Portugal durch die Vernichtung einer arabischen Flotte vor Diu die vollständige Seeherrschaft im Indischen Ozean. 1510 besetzt Alfonso de Albuquerque Goa. 1535 wird Diu, 1588 Damão portugiesisch.

Vor allem Alfonso de Albuquerque hatte begriffen, dass das kleine, bevölkerungsarme Portugal nicht in der Lage gewesen wäre, seine Herrschaft auf Landbesitz zu begründen. Unter seiner Führung stützten sich die Portugiesen daher auf ihre Seemacht. Albuquerque eroberte und sicherte die wichtigsten Stützpunkte an den afrikanischen und asiatischen Küsten des Indischen Ozeans, so dass im Falle von Gefahr das portugiesische Indiengeschwader schnell zu den Konfliktherden verlegt werden konnte. Sofala und Mosambik in Ostafrika, Maskat und Hormuz am Eingang zum Persischen Golf, Goa und Cochin in Indien sowie Malakka auf der Malaiischen Halbinsel bildeten die Eckpfeiler des portugiesischen Estado da Índia und legten die Grundlagen für die See- und Handelsherrschaft der Portugiesen im 16. Jahrhundert im Indischen Ozean. Da die Eroberung von Aden misslang, blieb der alte Handelsweg durch das Rote Meer für die Muslime weitgehend offen, zumal die Osmanen 1538 Aden besetzten.

Zu Beginn des 17. Jahrhunderts begann das Vordringen der Niederländer und der Engländer nach Süd- und Südostasien. Die Niederländer wichen dabei der portugiesischen Route nach Indien aus und steuerten, dank verbesserter geographischer und astronomischer Kenntnisse, vom Kap der Guten Hoffnung aus direkt das heutige Indonesien an.

Ab 1756 begannen die Briten den größten Teil Indiens zu erobern. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt hatte Portugal bereits den Zenit seiner Macht überschritten und konnte so der britischen Expansion nichts mehr entgegensetzen. 1802 bis 1813, während im portugiesischen Mutterland der Kampf zwischen den Briten und Napoleon tobt und Portugal danach de facto durch den britischen Militärbefehlshaber William Carr Beresford regiert wird, ist Portugiesisch-Indien britisch besetzt.

[...]

1946 hatte Portugiesisch-Indien als erste Kolonie den Status als Überseeprovinz erhalten, was allerdings zu keinen großen Veränderungen in der Verwaltung führte. 1954 übernahmen lokale, indische Nationalisten in den portugiesischen Besitzungen Dadra und Nagar Haveli die Kontrolle und schaffen eine proindische Verwaltung. Indien verweigerte für die portugiesischen Truppen den Zugang zu den Enklaven durch sein Territorium. 1961 verliert schließlich Portugal seine letzten indischen Kolonien Goa, Diu und Damão. Diese wurden von der indischen Armee handstreichartig besetzt. In Goa standen 3.000 schlecht ausgerüstete portugiesische Soldaten einer indischen Übermacht von 30.000 Mann gegenüber. Die portugiesische Regierung unter António de Oliveira Salazar war nicht bereit, ihre indischen Kolonien aufzugeben und befahl den dort stationierten Soldaten, in völliger Verkennung der militärischen Machtverhältnisse, sich gegen die Inder zu wehren. Die lokalen Befehlshaber sahen jedoch, dass der Widerstand zwecklos war, und leisteten deshalb dem indischen Einmarsch kaum Widerstand. Portugiesisch-Indien hörte somit nach über 450 Jahren portugiesischer Präsenz auf zu existieren und wurde in die Indische Union eingegliedert.

LiteraturFeldbauer, Peter: Die Portugiesen in Asien : 1498 - 1620. -- Essen : Magnus, 2005. - 254 S. : Ill. ; 23 cm. -- ISBN 3-88400-435-2. -- Frühere Ausg. u.d.T.: Estado da India

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portugiesisch-Indien. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-20]

Archiv:

Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (AHU), Lisboa. -- Webpräsenz: http://www.iict.pt/ahu/. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-26

Abb.: Vasco da Gama

Originaltext:

Velho, Alvaro <Vermutlicher Autor>: Roteiro da viagem de Vasco da Gama em MCCCCXCVII. -- 2. ed., correcta e augmentada de algumas observações principalmente philologicas / por A. Herculano e o barão do Castello de Paiva. -- Lisboa : Imprensa nacional, 1861. -- xliii, 180 S. ; 22 cm.

Deutsche Übersetzung:

Hümmerich, Franz <1868 - >: Vasco da Gama und die Entdeckung des Seewegs nach Ostindien ; auf Grund neuer Quellenuntersuchgn dargest. -- München: C. H. Beck, 1898. -- XIV, 203 S. ; 24 cm. -- S. 149 - 191

Teilausgabe der deutschen Übersetzung:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. -- 1a. Zum Beispiel: Roteiro da viagem de Vasco da Gama em 1497. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1501a.htm

"C. Die zwei ältesten Quellen zur Geschichte der ersten Indienfahrt. 1. Roteiro da viagem de Vasco da Gama em 1497, 2a ed.. correcta etc. por Alexandro Herculano e o barão do Castello da Paiva, Lisboa 1861, die im folgenden übersetzte Quelle.

2. La navigatione prima (di Vasco da Gama) scritta per un gentiluomo Fiorentino che si trovô al tornare dell' armata in Lisbona, gedruckt bei Ramusio, Delle Navigationi etc. Bd. I, S. 119 ff. & Paesi novamente retrovati, c. LI.

Wer die oben (S. 118) angeführte Stelle auf S. VI von Stanleys Einleitung liest, der muss zu der Meinung kommen, dass es außer den Werken des Correa, Castanheda, Barros, Goes und Osorio keine Quelle für die Kenntnis der ersten Indienfahrt gebe. Sie alle können aber nicht einmal als Quellen erster Hand angesehen werden, weil ihre Darstellung wieder auf andere Berichte zurückgeht. Und doch sind uns zwei Quellen erhalten, die als unmittelbarer Niederschlag der Ereignisse gelten dürfen, und von denen jede Kritik der anderen ausgehen muss. Das eine ist der Roteiro da viagem de Vasco da Gama em 1497 (Wegweiser von Vasco da Gamas Reise im Jahre 1497), der im folgenden übersetzte Bericht eines Seemannes, der die Entdeckungsfahrt mitmachte, das zweite, schon in den Paesi novamente retrovati 1507 und danach in Ramusios großem Werk erschienen, der Brief eines Florentiner Edelmannes, der sich zur Zeit der Rückkehr von Gamas Schiffen in Lissabon befand. Da wir es hier mit zwei von einander unabhängigen, in sich glaubwürdigen Berichten zu tun haben, so darf als kritischer Grundsatz für die Beurteilung von [S. 126] Ereignissen der Entdeckungsfahrt aufgestellt werden: Wo diese beiden Darstellungen inbezug auf eine Einzelheit der Reise übereinstimmen, muss die betreffende Tatsache als zweifellos erwiesen gelten. Von diesen beiden Berichten hat Stanley keinen benutzt; wer nun aus dieser Tatsache schließen wollte, dass er keinen davon gekannt habe, der würde einen Fehlschluss tun; denn im Appendix seines Buches, S. I, teilt er mit genauer Quellenangabe ein Dokument mit, das im Anhange des Roteiro veröffentlicht ist. Stanley wusste also von diesem Buche und hat es nicht für nötig befunden, dasselbe in den Kreis seiner Betrachtung auch nur mit einem Worte hereinzuziehen.

Der bei Ramusio gedruckte Brief des Florentiners stammt aus der zweiten Hälfte des Jahres 1499. Es ist zuerst von Angelo Bandini (Vita e Lettere di Amerigo Vespucci, Florenz 1745, p. 85 ff.) und danach von portugiesischen Forschern mehrfach dem Amerigo Vespucci zugeschrieben worden, kann aber nach der oben mitgeteilten Überschrift bei Ramusio, die auch durch den Inhalt bestätigt wird, von ihm nicht herrühren, da sich Vespucci zur Zeit von Gamas Heimkehr (August oder September 1499) auf seiner Reise mit Hojeda befand, von der er nach der bestbegründeten Ansicht erst im Juni 1500 zurückkam. Zweifellos aber war er in der zweiten Hälfte des Jahres 1499 nicht in Lissabon. Der Bericht zerfällt in zwei Abschnitte. Der erste derselben, Kap. I—VI umfassend, ist entstanden, ehe Vasco da Gama selbst oder sein Schiff Gabriel noch eingetroffen war, gründet sich also auf Erkundigungen, die der Verfasser von der Besatzung der Berrio eingezogen hatte. Der zweite Teil, Kap. VII und VIII. fußt auf Mitteilungen des bei Angediva gefangenen Juden, den er, ebenso wie andere Teilnehmer an der Fahrt, persönlich über alles befragt hat. Abgeschlossen wurde der Brief nach dem Eintreffen entweder des Vasco da Gama oder seiner von Santiago (Kapverden) kommenden S. Gabriel, sicher aber vor Ende des Jahres; das ergibt sich mit Bestimmtheit aus der Angabe des Schlusssatzes, dass in Lissabon bereits vier Schiffe und zwei Caravellen bereit lägen, um im kommenden Januar nach dem Osten abzugehen. Für die Kenntnis der Reise im einzelnen ist aus dem Brief wenig zu gewinnen; er enthält sogar einige fehlerhafte Angaben; der Verfasser, ein in Portugal heimischer Florentiner, will vielmehr die kommerziellen Resultate und voraussichtlichen Wirkungen der neuen Entdeckung feststellen; er verweilt mit Interesse bei der Frage, welche Artikel sich zum Export und Import in den neu entdeckten Ländern voraussichtlich eignen werden, bei der Herkunft und dem Preis der einzelnen Gewürze und Juwelen, bei den Handelswegen und Verkehrsmitteln, bei der Fahrbarkeit der östlichen Heere, den Münzverhältnissen u. s. w. Ihn interessiert die kaufmännische Seite der Sache, nicht die Reise selbst in erster Linie. Von diesem Bericht sind einige mehr oder minder genaue deutsche Übersetzungen aus dem 16. Jahrhundert erhalten. Die eine stammt aus Konrad Peutingers Nachlass, und ist mit dem Tagebuch des Lukas Rem (S. 120 ff.) von B. Greiff (Augsburg 1861) herausgegeben worden. Sie war dem Hause Welser von Rom aus zugesandt, enthält mancherlei Missverständnisse und ist mehr eine Inhaltsangabe als eine wirkliche Übersetzung. Eine andere findet sich in dem 1534 zu Strassburg erschienenen Sammelwerk von Michael Herr, "Die New Welt" (S. 18 ff.). Sie schließt sich einigermaßen an das Original an, ersetzt aber im ersten Abschnitt meist die dritte Person durch die erste. "Alss wir nu wider heim kumen warend" u. s. w. Auf die gleiche Quelle geht der Bericht bei Jobst Ruchamer "Unbekannthe Landte und ein newe Welt" (Nürnberg 1508), Kap. 51—62, zurück. Selbständigen Wert haben diese Übersetzungen neben dem italienischen Original [S. 127] alle nicht. Auch Bernaldez (Historia de los Reyes catholicos, Sevilla 1870, Kap. 158) hat aus dem Bericht unseres Florentiners seine Kenntnis der ersten Indienfahrt geschöpft.

Die zweite, durchaus selbständige und. wie wir sehen werden, wertvollste aller Quellen ist der in Übersetzung folgende Roteiro. Es ist der nach Tagebuchaufzeichnungen angefertigte Bericht eines Seemannes, der auf dem Schiffe des Paulo da Gama von Lissabon mitausfuhr. Dass er Seemann, nicht Soldat war, ergibt sich mit Wahrscheinlichkeit unter vielen anderen aus der Stelle in Kap. 12 von Beilage II, wo er sagt: "An selbigem Tage nach dem Essen fanden wir beim Aufsetzen eines Beisegels eine Elle unter dem Mastkorb einen Riss in dem Maste, und selbiger Riss öffnete und schloss sich." Die Tatsache, dass er zur Mannschaft des Paulo da Gama gehörte, ergibt sich aus Kap. 1, wo er erzählt, wie allmählich das zerstreute Geschwader sich wieder zusammenfindet. Fünf Schiffe sind es mit dem des Bartolomeo Diaz. Am Sonntag — erzählt unser Autor — kommen das Proviantschiff, die Caravelle des Nicolao Coelho und das Schiff des Bartolomeo Diaz in Sicht und am folgenden Mittwoch das des Geschwaderchefs; also muss er selbst mit Paulo da Gama gefahren sein. Zu den Kapitänen gehörte er nach dieser und anderen Stellen nicht; dass er auch kein Steuermann war, machen solche Stellen wahrscheinlich wie Kap. 71: "Und die Steuerleute sagten, dass wir auf den Untiefen des Rio Grande seien." Seinen Namen nennt er nicht, wie er denn überall seine Person bescheiden in den Hintergrund stellt. Was wir außer Kleinigkeiten von ihm erfahren, ist, dass er zu den ausgewählten Mannschaften gehörte, die Vasco da Gama zu der Audienz beim Raja von Calicut mit an Land nahm. Aus dieser Tatsache haben die portugiesischen Herausgeber des Roteiro — die erste Ausgabe veranstalteten (Porto 1838) Diogo Kopke und Antonio da Costa Paiva — durch Vergleich mit Castanheda seinen Namen zu ermitteln gesucht. Sie schließen S. XXV—XXXI folgendennassen: Castanheda (Historia do descobrimento, Liv. I, c. 16) nennt von den Begleitern des Kommandanten in Calicut den Diogo Diaz, Schreiber des Vasco da Gama, Fernão Martins, den Dolmetscher, ferner den Veador (Warenverwalter) des Vasco da Gama, dessen Name nicht angegeben wird, dann João de Sá, Schreiber des Paulo da Gama, einen Matrosen mit Namen Gonçalo Pires, einen gewissen Alvaro Velho und Alvaro de Braga, Schreiber des Nicolao Coelho. Nun steht durch die fast wörtliche Übereinstimmung beider Darstellungen fest, dass für Castanhedas Schilderung der Entdeckungsfahrt unser Roteiro die Quelle gewesen ist. Da Castanheda nicht gar lange nach den Ereignissen, welche er hier schildert, gelebt und eine seltene Sorgfalt darauf verwandt hat, die Wahrheit des Geschehenen möglichst vollständig zu ergründen, so ist anzunehmen, dass er von dem Autor unseres Roteiro den Namen wusste, und da derselbe nach seinem eigenen Bericht zu dem Gefolge des Kommandanten in Calicut gehörte, so wird er unter den bei dieser Gelegenheit von Castanheda Genannten schwerlich übergangen sein. Nun schließt aber die Erzählung des Roteiro ohne weiteres aus, dass der Autor des Tagebuches Diogo Diaz sein könnte oder Fernão Martins oder der Veador des Vasco da Gama oder Alvaro de Braga. Gegen João de Sá sprechen folgende Erwägungen: Erstens war unser Autor, wie es scheint, ein einfacher Matrose, zweitens wissen wir durch Castanheda (Hist. do descobr. Liv. I, c. 16), dass João de Sá von dem Christentum der Inder nicht so ganz überzeugt war, während unserem Autor darüber nicht der mindeste Zweifel gekommen ist. Es bleiben also nur noch Gonçalo Pires und Alvaro Velho. Die Entscheidung aber zwischen diesen beiden ist nicht schwer. Wenn man nämlich die Stellen nebeneinandersetzt, an [S. 128] denen bei Castanheda von Gonçalo Pires die Rede ist, und dann die Darstellung unseres Berichtes damit vergleicht, so ergibt sich klar, dass der Autor des Roteiro jenen von seiner Person trennt. Castanheda sagt a. a. O., Liv. I, c. 21: "Der Catual .... nahm Vasco da Gama längs des Strandes mit, und da derselbe auf Grund dessen, was ihm in Calicut widerfahren war, diesem Volk misstraute, so sagte er dem Gonçalo Pires, dem Matrosen, er solle mit noch zwei der Unseren vorausgehen, soweit er könne, und wenn er den Nicolao Coelho mit den Booten finde, ihm sagen, dass er sich in Sicherheit bringen möge." An der entsprechenden Stelle, Kap. 47, berichtet unser Autor: "Dann führten sie uns am Strande hin, und der Kommandant, dem das gefährlich schien, schickte drei Leute voraus mit dem Befehl, wenn sie die Boote von den Schiffen sähen, und sein Bruder da sei, dass er sich in Sicherheit bringen solle." Beide Autoren berichten dann, wie die drei Leute sich von den übrigen weg verlieren, und fahren fort: Castanheda: "So saßen sie, da kam Gonçalo Pires an, mit der Meldung von Nicolao Coelho, dass er ihn mit den Booten erwarte." Unser Autor (Kap. 49): "Und während wir so saßen, kam einer von den Leuten, die sich am Abend vorher verloren hatten, und meldete dem Kommandanten, dass Nicolao Coelho seit dem Abend vorher mit den Booten an Land sei und auf ihn warte." Es bliebe also von den Genannten als Autor für den Roteiro nur Alvaro Velho übrig. Die portugiesischen Herausgeber sind sich natürlich klar darüber, dass diese Kette von Schlussfolgerungen nur den Wert einer Konjektur hat, die lediglich unter der doppelten Voraussetzung zutrifft, dass Castanheda von unserem Autor den Namen gewusst und genannt hat, und dass er, über die Einzelheiten dieser Tage gut unterrichtet, in der Wiedergabe der Ereignisse ebenso gewissenhaft wie sonst im allgemeinen war.

Wer der Verfasser des Roteiro auch sein mag, sein Bericht ist das Wertvollste, was wir über die erste Indienfahrt des Vasco da Gama besitzen. Leider aber ist er nicht vollständig und war es vermutlich nie. Die Erzählung der Entdeckungsfahrt bricht mit dem 25. April 1499 jäh ab, unmittelbar vor dem Augenblick, wo Nicolao Coelho durch Sturm von dem Kommandanten getrennt wird, es folgt aber darauf ein Anhang über indische Länder und Reiche, Handelsprodukte und Gewürzpreise, der nach Stil und Inhalt von demselben Verfasser herzurühren scheint. Der Eindruck des Bewussten und Gewollten in dem plötzlichen Verstummen des Berichterstatters wird durch das Vorhandensein dieses Anhanges noch verstärkt. Dass Coelhos Schiff am 10. Juli allein in Lissabon einfuhr, steht fest durch die Übereinstimmung fast aller Quellen mit dem oben erwähnten Brief des Florentiner Edelmannes. Die Frage, ob jene Trennung von Nicolao Coelho beabsichtigt war, ob er, der größeren Geschwindigkeit seiner Caravelle vertrauend, der erste sein wollte, der von der Entdeckung Indiens dem König die Kunde brächte, muss offen gelassen werden. Castanheda nimmt das unlautere Motiv an, Barros und Goes schreiben die Trennung lediglich der Gewalt des Sturmes zu, und der erste erzählt sogar, Nicolao Coelho habe umkehren wollen, als er an der Barre von Lissabon vernahm, dass der Kommandant noch nicht eingetroffen sei. Nach dem Brief des Florentiners möchte man eher an eine beabsichtigte Trennung denken. Da der Sturm außerdem bei den Inseln des grünen Vorgebirges stattfand, diese Inseln aber für die Hinfahrt als Sammelpunkt für den Fall einer Trennung durch die Instruktion zweifellos bestimmt waren, und Vasco da Gama auch auf der Rückfahrt nach dem Sturm Santiago anlief, so wäre ein Gleiches bei Nicolao Coelho wohl das Natürlichere gewesen. Was hat aber diese Frage mit dem jähen Abbrechen unseres [S. 129] Tagebuches, was hat der Verfasser desselben mit Nicolao Coelho zu tun? Nach den übereinstimmenden Berichten unseres Autors, des Castanheda, Barros, Goes u. a. wurde bei der Rückkehr auf den Untiefen des heil. Raphael das Schiff des Paulo da Gama verbrannt und der Rest seiner Mannschaft teils auf die Gabriel, teils auf die Caravelle des Nicolao Coelho versetzt. Sollte unser Autor der letzteren zugeteilt worden sein? In diesem Falle würde sein jähes Verstummen für Nicolao Coelho schwerlich etwas Gutes bedeuten. Mit Sicherheit wird man indes nicht danach urteilen können.

Die Handschrift, auf Grund deren Diogo Kopke und Antonio da Costa Paiva die erste Ausgabe des Roteiro veranstalteten, die einzige Handschrift, in der er erhalten ist, stammt aus der Bibliothek des ehedem so reichen Klosters von Santa Cruz in Coimbra und befindet sich heute in der Bibliothek von Porto, wohin sie mit dem größten Teile jener alten und wertvollen Sammlung bei der Aufhebung der Klöster gebracht wurde. Dass man es mit keinem Autographen des Verfassers zu tun hat, ergibt sich aus Kap. 60, wo der Kopist auf eine Lücke im Text mit den Worten aufmerksam macht: "Wie diese Waffen aussehen, ist dem Verfasser des Buches in der Federspitze stecken geblieben." Dem Schriftcharakter nach gehört indes die Kopie, wie die Herausgeber bestimmt versichern, dem beginnenden 16. Jahrhundert an, ist also sehr früh. Die Vermutung, dass der Bericht nie vollständig gewesen sei, wird wahrscheinlich auch dadurch, dass schon Castanheda ihn nur soweit kannte, als er uns vorliegt. In der äußerst seltenen Ausgabe des ersten Buches seiner Historia do descobrimento vom Jahre 1551 sowie in der danach angefertigten spanischen Übersetzung, die zu Antwerpen 1554 erschien, steht (Kap. 27) fast wörtlich der Schlusssatz unseres Roteiro: "und die Piloten sagten, dass sie auf den Untiefen des Rio Grande seien", und dann folgt unmittelbar: "und die weiteren Einzelheiten, die der Kommandant von da an bis zu der Insel Santiago noch erlebte, konnte ich nicht erfahren, nur ..." Dieser Satz findet sich zwar in der zweiten Ausgabe von Castanhedas erstem Buch nicht mehr (1554), aber es wird über den Rest der Reise nicht eine Tatsache mehr als dort mitgeteilt. Auf Grund einer gewissen Ähnlichkeit der Schrift und aus dem Fundort des Manuskriptes, Coimbra, haben die portugiesischen Herausgeber vermutet, die erhaltene Abschrift des Roteiro könne, da Fernão Lopez de Castanheda die letzten Jahre seines Lebens in Coimbra verbracht und sein Werk daselbst verfasst hat, von ihm selbst geschrieben sein. Damit ist aber ihre andere Angabe nicht wohl vereinbar, wonach das Manuskript in die Anfänge des 16. Jahrhunderts gehören soll; und eine Stelle Castanhedas steht mit dieser Annahme in direktem Widerspruch. Hist. do descobr., Liv. I, c. 16, erzählt er nämlich, wie Vasco da Gama sich von Pandarane, wo die Schiffe verankert liegen, zur Audienz bei dem Raja nach Calicut begibt. "Nachdem Vasco da Gama," heißt es dort, "in diese Sänfte eingestiegen war, brach er mit dem Catual, der in einer anderen den Weg zurücklegte, nach einem Orte auf, von dem ich den Namen nicht erfahren konnte." Nun steht aber in unserem Manuskript in voller Übereinstimmung mit dem, was wir nach der Lage der Orte und den Berichten der Historiker als gesichert annehmen dürfen, dass Gamas Weg nach Calicut über Capocate ging, das der Roteiro Capuá nennt, und dass dort die Mittagsrast stattfand, von der Castanheda spricht. Dass das Capuá des Roteiro mit Capocate identisch sei, wusste derselbe, wie ein Vergleich zwischen Liv. I, c. 13 seiner Hist. do descobr. mit Kap. 37 unseres Berichtes ergibt. Der Bericht des Roteiro ist. wie schon erwähnt, nach der Lage der Orte völlig einwandfrei, und Castanheda [S. 130] konnte sachliche Bedenken gegen die Angabe desselben somit nicht haben; wenn er also erklärt, er habe den Namen nicht erfahren können, so kann unsere Kopie des Roteiro, die denselben enthält, sein Handexemplar nicht gewesen sein.

Was die Glaubwürdigkeit der Darstellung betrifft, so spricht alles für den Roteiro. Erstens ist er zweifellos nach einem Tagebuch gearbeitet, wie die mit Wochen- und Monatstag fest datierten Notizen, oft über ganz geringfügige Ereignisse, beweisen. Zweitens ist der Autor ein einfacher, bescheidener Mensch, der überall seine Person in den Hintergrund stellt, nirgends aus persönlicher Vorliebe oder Abneigung Tatsachen entstellt, sondern ruhig und sachlich, mit der frischen und naiven Auffassung eines ungebildeten, aber vortrefflich beobachtenden Mannes, mit behaglicher Breite und unverkennbarer Gutmütigkeit die Dinge, die er sieht und erlebt, unter dem frischen Eindruck des Geschehenen in einem sehr wenig gewandten, von Fehlern und Unbeholfenheiten wimmelnden, aber nicht reizlosen Portugiesisch aufzeichnet.

In diesem Tagebuch und dem schon besprochenen Briefe des Florentiner Edelmannes haben wir also für die erste Reise des Vasco da Gama zwei voneinander unabhängige, in sich glaubwürdige Quellen im eigentlichen Sinne; daher muss, um das noch einmal an den Schluss dieses Abschnittes zu stellen, wo diese beiden Quellen inbezug auf ein Geschehnis der Reise übereinstimmen, dasselbe als erwiesen angesehen werden. Unter diesem Gesichtspunkt gilt es, ihre Darstellung mit der des Correa zu vergleichen."

[Quelle: Hümmerich, Franz <1868 - >: Vasco da Gama und die Entdeckung des Seewegs nach Ostindien ; auf Grund neuer Quellenuntersuchgen dargest. -- München: C. H. Beck, 1898. -- XIV, 203 S. ; 24 cm. -- S. 125 - 130]

Correa, Gaspar <16. Jhdt>: Lendas de India par Gaspar correa / Gaspar Correa publicadas ... soba déreagãe de Rodrigo José de Lima Felner [1809 - 1877]. -- Lisboa : Typ. da Academia real das sciencias, 1858-1864. -- 4 Bde. : Ill. ; 28 cm. -- (Collecçao de monumentos eneditos para a historia das renquistas dos Portuguezes en Africa, Asia et America ; Ser. 1, T. 1-4)

Übersetzung:

Correa, Gaspar <16. Jhdt>: The three voyages of Vasco da Gama, and his viceroyalty. From the Lendas de India of Gaspar Correa. Accompanied by original documents / Translated from the Portuguese, with notes and an introd., by Henry E. J. Stanley. -- New York : Franklin, [1963?]. -- lxxx, 430, xxxv S. ; 23 cm. -- Reprint of the 1869 ed. published by the Hakluyt Society. -- (Hakluyt Society. Works ; no. 42.). -- Originaltitel: Lendas de India. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/voyageroundworld01tayl. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-22. -- "Not in copyright."

Teile der Übersetzung siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. -- 1. Zum Beispiel: Gaspar Correa <16. Jhdt.>: Lendas de India, erste Reise Vasco da Gamas nach Indien. -- Fassung vom 2008-05-25. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1501.htm

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. -- 2. Zum Beispiel: Gaspar Correa <16. Jhdt.>: Lendas de India, dritte Reise Vasco da Gamas nach Indien. -- Fassung vom 2008-05-26. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1502.htm

"INTRODUCTION. Louvarei antes o Camoens sublime,

E o bravo Gama, arando ignotos mares,

E as Nereidas nuas impellindo

As uaos, que ameaça o escolho.Francisco MANUEL

The account here given of Vasco da Gama's voyages is taken from Gaspar Correa's Lendas da India, and is entirely new ; for Correa's work, which has only been printed within the last ten years, enters into much more detail than the other chroniclers, frequently differs from them, and has not been made use of by the great majority of the historians who wrote subsequently to him.

Gaspar Correa went to India, as he says in his prologue, when very young, and sixteen years after India was discovered,—that would be in 1514. The editors of the history, printed by the Academy of Lisbon, say, however, that he sailed with Jorge de Mello in March of 1512, on the ground of a receipt of which a facsimile is given. The receipt is signed by Gaspar Correa, but bears no date. It does not appear to bear out the assumption that Correa sailed with Jorofe de Mello. It runs thus : [S. ii]

" tres adiçoes

Gaspar Correa que foy de Jorge de mello que foy mestre salla avera ho mes de Junho sem cevada ao respeito 406 reis Recebeo de nuno Rybeiro os quatrocentos e seys reis em cyma conteudos,

Bastião da costa. Gaspar Correa."Correa arrived in India fifteen years before Castanheda, and must have begun to write his history during the government of Alfonso d'Albuquerque, since while he was his secretary he got hold of a diary written by Joam Figueira, a priest, who accompanied Gama ; and this, he says, gave him the desire to write down all that he could learn of the deeds done in India. He wrote the history of fifty-three years of the Portuguese exploits in India, leaving off with the government of Jorge Cabral. He mentions having written part of his history in 1561. The year of his death, which, according to Barbosa Machado, occurred in Goa, is not known ; but, as the editors of the printed copy say, it must have been before 1583, since Miguel da Gama, son of D. Francisco, the second count of Vidigueira, left India on February 21st, 1583, bringing with him Correa's manuscript. D. Miguel's ship, the Reliquias, encountered many storms, and at length arrived in the Tagus, where fire broke out on board the ship, which was with difficulty extinguished, and Correa's manuscript escaped from this danger also.

Nicholas Antonio, in his Bibliotheca Scriptorum Hispaniae (Rome, 1672), mentions our author in the following terms, "Gaspar Correa, Lusitanus, a civibus suis laudatur eo quod scripserit, Historia da India" ; [S. iii] and the prologue of the Academy edition compares him to Polybius : so that it might be a matter of surprise that his work was not published till three centuries after it was written.

The printed edition explains the causes which operated to prevent this publication in later times : at an earlier period they must be attributed to the fact that Correa expressly intended his work to be a posthumous one, in order that he might speak the truth of all concerned ; after his death, from the corruption which had set in among the Portuguese, truth was still more unpalatable ; and it may also be supposed that many passages of Correa's history could not have passed through the censure of the Inquisition, since at that time they would have affixed upon D. Joam II. and upon D. Manuel the stigma of Judaism and necromancy.

Correa's work was hardly ever mentioned from that time till 1790, when the Lisbon Academy determined on obtaining a copy of it, for the purpose of printing it. Till lately they had not obtained more than a transcript of part of the first volume, made by two persons, apparently at the end of the last century or beginning of the present one. At length, in 1836, the second, third, and fourth volumes of Correa's manuscript, written in his own hand, were deposited in the library of the Archives by Senhor Dr. Antonio Nunes de Carvalho. The work, however, could not proceed for want of the first volume, which is lost without leaving any trace or hopes of recovery.

Some years ago, however, Senhor Aureliano Basto, [S. iv] father of Senhor Joam Basto, the Keeper of the Archives, was so fortunate as to hear of a copy of the first volume in the shop of a confectioner, where he bought it for twenty-eight thousand eight hundred reis. This copy is said to be of a date but a little more modern than the time of Correa.

A second copy exists in the Royal Library of the Ajuda, in two volumes, in a handwriting apparently of the eighteenth century, or end of the seventeenth. This copy is very imperfect. In many parts the copyist has been unable to read the original, besides which he took impardonable liberties with the text, correcting and mutilating it, and making large omissions. This copy, however, served to assist MM. Basto and Gomes Goes, also of the Archives, in preparing a copy for the press, which has been edited by Senhor Rodrigo J. de Lima Felner.

The translation now given to the Hakluyt Society has been made from a transcript taken from another copy of the first volume, the property of the Duke of Gor, and which before it belonged to his family, had belonged to the Count of Torrepalma. I was not aware till last year that copies of Correa existed at Lisbon ; and the editors of the Lisbon edition did not know of the copy in the possession of the Duke of Gor. Singularly enough, the Duke of Gor's copy and that rescued from the confectioner appear to have been written by the same scribe : the handwriting, size of the volume and page, columns and headings of the pages in red ink, are similar in the two copies. A whole leaf, however, of the [S. v] Lisbon copy had gone to wrap up sweetmeats, so that the beginning of chapter vi and end of chapter vii have been made to coalesce into chapter vi in the printed edition.

The various chroniclers who have related Gama's voyage to India vary very much in their dates, and agree only as to the date of his arrival at the river named Dos Reis, on Twelfth Day. They also differ in the number of ships that composed the squadron, some giving four and others three ships, and they vary as to where the three ships were reduced to two, Correa's account, however, differs still more from that of all the others, for he makes the departure from Melinde and arrival in India three months later than in any of the other narratives.

He also very much shortens the return voyage to Melinde, which the other historians represent as one of the most arduous passages, in which the crews suffered great hardships. In this, Camoens seems to have followed Correa, canto x, stanza 144 :

" Thus they set out, cutting through the sea serene,

With the wind always gentle, meeting no storm,

Until the desired land hove in sight again ;

The ever-beloved country in which they were born."MITCHELL.

They also differ in the fact that Correa names Gama's ship S. Rafael, whilst Barros names it S. Gabriel; but outside the town of Vidigueira, of which Gama was made Count, there is a chapel of St. Raphael, in which an image of that saint is preserved to whom Gama's ship was dedicated. Correa is also the only [S. vi] historian who relates that Gama visited Cananor [Kannur/കണ്ണൂര്] on leaving Calicut [Kozhikode/കോഴിക്കോട്].

The following are the reasons why, in my opinion, Correa's narrative should be preferred to the others.

Firstly, he came to India earlier than any of the other writers, and was the only one who made use of the diary of the priest Joam Figueira. Castanheda who went to India in 1528, is the only historian who competes with him in this respect. Damian de Goes did not visit India. Osorio takes almost all his facts from Goes, and Barros wrote much later.

Secondly, the reasons given by Correa why his work should be a posthumous one, and the religious respect for truth which he professes, ought to secure to him a large share of credibility.

Thirdly, in many of the points in which Correa is at variance with the other chronicles, his narrative is more in accordance with human nature and probability.

The salient points of the narratives of Castanheda, Barros and others, have been added at the foot of the text, and further reasons for preferring Correa's dates and version will be found in the footnotes.

The Lisbon edition does not examine which of the various accounts are to be preferred. The prologue only observes that Correa's work contains some chronological errors, and disputes what he says of the invention of nautical instruments, and of the use of portable firearms. It adds, that "these venial faults ought not to diminish the lustre of Caspar Correa, nor raise doubts as to his good faith, and the full truth with which he relates what he saw and [S. vii] heard." The prologue also disputes Correa's giving the credit of the voyage of Bartholomew Dias to Joam Infante. Here, however, geography supports Correa, for the name of Rio do Infante, the term of the voyage in which Joam Infante and Bartholomew Dias doubled the Cape of Good Hope, shows that Correa had not exaggerated the position held by Joam Infante in that voyage.

I do not know to what anachronism as to espingardas or firelocks the prologue refers : Barros, however, and not Correa, is the person who is guilty of them in Gama's first voyage. Correa only mentions the use of cross-bows.

Amongst the rare occasions in which Caspar Correa mentions himself, we find the following in the year 1547 (tom. iv, p. 596). At that time "D. Joao de Castro (the thirteenth governor) thought it right to preserve some recollection of the former governors, so he summoned me, Caspar Correa, as I understood painting, and because I had seen in this country all the governors who had governed in these parts; and he enjoined me to work at drawing all the governors naturally [the size of life ?]. In which I occupied myself with a painter, a man of the country, who had a great natural turn, and he, by the directions which I gave him, painted their faces so like nature, that whoever had seen them, at once, on seeing the paintings, recognised them. The governor also had himself painted there after nature, armed as if he was figuring in a triumph.1 All were painted on boards, [S. viii] each one separately, full size, and all armed with corslets, and some with the very weapons with which they armed themselves, and upon them garments of dark silk, with very rich gold embroidery, and handsome swords, and above their heads the escutcheons of their arms. At the foot of each was written in gilt letters their names, and the time during which they had governed. He ordered these to be placed in the hall of their house, covered with curtains. This was a thing which looked very well, and all the ambassadors and foreign merchants delighted much in seeing them ; so much so that some kings and lords sent to fetch them all together to see them. The governor put lay figures2 in the hall, with halberds,3 and with awful features to inspire dread in the Moors who saw them. As the first governor was the Viceroy D. Francisco d'Almeida, the head of the house of the Almeidas of Portugal, a man of great merit, as has been written in this history, and as the governor was much pleased with his noble deeds, he ordered an inscription to be written in this manner: 'Rejoice, O great and warlike Lusitania, over your good Portugal, since from thee issued Dom Francisco d'Almeida, the most illustrious man who conquered these parts : and warring in them subjected them to the lordship of Portugal, with so much glory to the royal sceptre."

1 This refers to the palm he holds in his hand, and the palm leaf crown on his head in the picture, tom. iv, p. 430.

2 Cabides.

3 BysarmasThe autograph manuscript of Correa contains his pen and ink sketches of these governors, which have been reproduced in the Lisbon edition. They are [S. ix] better than the portraits in Pedro Barreto de Resende's work, which are probably copied from the portraits at Goa. There is a MS. of P. B. de Resende in the Sloane collection of the British Museum."

[Quelle: Correa, Gaspar <16. Jhdt>: The three voyages of Vasco da Gama, and his viceroyalty. From the Lendas de India of Gaspar Correa. Accompanied by original documents / Translated from the Portuguese, with notes and an introd., by Henry E. J. Stanley. -- New York : Franklin, [1963?]. -- lxxx, 430, xxxv S. ; 23 cm. -- Reprint of the 1869 ed. published by the Hakluyt Society. -- (Hakluyt Society. Works ; no. 42.). -- Originaltitel: Lendas de India. -- S. i - viii. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/voyageroundworld01tayl. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-22. -- "Not in copyright."

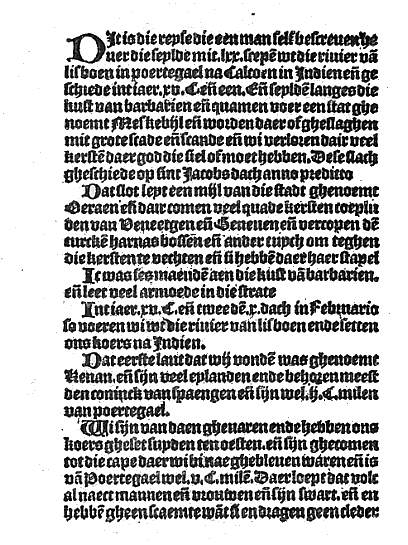

Abb.: Calcoen. -- Antwerpen, ca. 1504, 1. Seite [ein niederländischer Bericht

über Vasco da Gamas zweite Fahrt nach Indien]

[Bildquelle: Calcoen : a Dutch narrative of the second voyage of Vasco da Gama to Calicut, printed at Antwerp circa 1504 / with introduction and translation by J. Ph. Berjeau [1809 - 1891]. -- London : Pickering, 1874. -- Enthält das flämische Original in Faksimile. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/calcoendutchnarr00berjuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-06-08]

Abb.: Stützpunkte der Niederländer in Indien

[Bildquelle: Aliesin, Wikipedia, Creative Commons Lizenz:

Attribution ShareAlike 2.5]

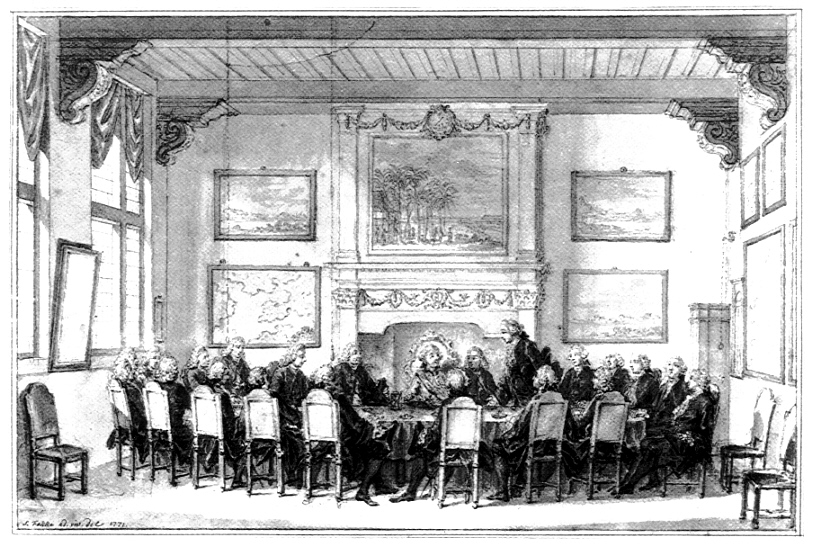

Abb.: Sitzung im Ostindienhaus, Amsterdam / von Simon Fokke, 1771

[Bildquelle: Gelder, Roelof van: Das ostindische Abenteuer : Deutsche in Diensten der Vereinigten Ostindischen Kompanie der Niederlande (VOC), 1600 - 1800. -- Hamburg : Convent, 2004. -- 271 S. : Ill. ; 27 cm. -- (Schriften des Deutschen Schiffahrtsmuseums ; Bd. 61). -- Originaltitel: Het Oost-Indisch avontuur : Duitsers in dienst van de VOC (1997). -- Zugleich. Amsterdam, Univ., Diss., 1997. -- ISBN 3-934613-57-8. -- S. 27]

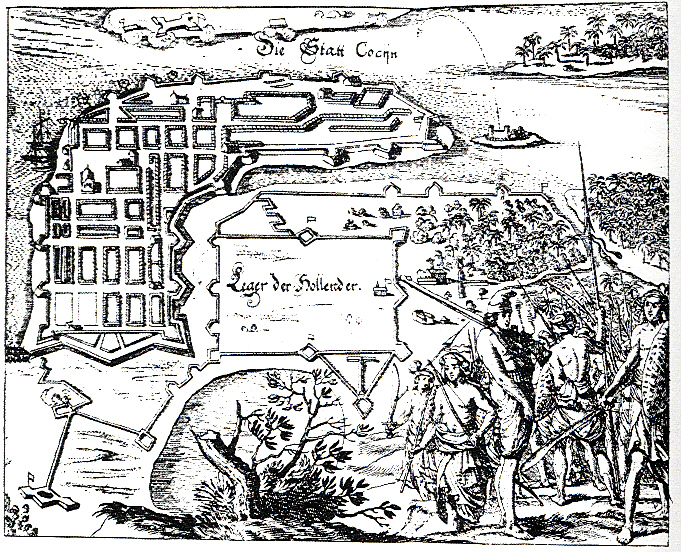

Abb.: "Leger der Hollender", Cochin, 1669

Abb.: Singhalesen auf Ceylon (Sri Lanka) huldigen dem holländischen

Befehlshaber, 1669

"DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY, THE (Oostindische Vereenigde Maatschappij), a body founded by a charter from the Netherlands states-general on the 20th of March 1602. It had a double purpose: first to regulate and protect the already considerable trade carried on by the Dutch in the Indian Ocean, and then to help in prosecuting the long war of independence against Spain and Portugal. Before the union between Portugal and Spain in 1580-81, the Dutch had been the chief carriers of eastern produce from Lisbon to northern Europe. When they were shut out from the Portuguese trade by the Spanish king they were driven to sail to the East in order to make good their loss. Unsuccessful attempts were made to find a route to the East by the north of Europe and Asia, which would have been free from interference from the Spaniards and Portuguese. It was only when these failed that the Dutch decided to intrude on the already well-known route by the Cape of Good Hope, and to fight their way to the Spice Islands of the Malay Archipelago. A first expedition, commanded by Cornelius Houtman, a merchant long resident at Lisbon, sailed on the and of April 1595. It was provided with an itinerary or book of sailing instructions drawn up by Jan Huyghen van Linschoten,1 a Dutchman who had visited Goa. The voyage was marked by many disasters and losses, but the survivors who reached the Texel on their return on the 20th of August 1597 brought back some valuable cargo, and a treaty made with the sultan of Bantam in Java. 1 Linschoten was born at Haarlem in or about 1563. He started his travels at the age of sixteen and, after some years in Spain, went with the Portuguese East India fleet to Goa, where he arrived in September 1583, returning in 1589. In 1594 and 1595 he took part in the Dutch Arctic voyages, and in 1598 settled at Enkhuizen, where he died on the 8th of February 1611. His Navigatio ac itinerarium (1595-1596) is a compilation based partly on his own experiences, partly on those of other travellers with whom he came in contact. It was translated into English and German in 1598; two Latin versions appeared in 1599 and a French translation in 1610. The famous English version was reprinted for the Hakluyt Society in 1885. Large selections, with an Introduction, are published in C. Raymond Beazley's Voyages and Travels, vol. ii. (English Garner, London, 1903).

These results were sufficient to encourage a great outburst of commercial adventure. Companies described as "Van Ferne" that is, of the distant seas were formed, and by 1602 from sixty to seventy Dutch vessels had sailed to Hindustan and the Indian Archipelago. On those distant seas the traders could neither be controlled nor protected by their native government. They fought among themselves as well as with the natives and the Portuguese, and their competition sent up prices in the eastern markets and brought them down at home. Largely at the suggestion of Jan van Oldenbarneveldt, and in full accordance with the economic principles of the time, the states-general decided to combine the existing separate companies into one united Dutch East India Company, which could discharge the functions of a government in those remote seas, prosecute the war with Spain and Portugal, and regulate the trade. A capital estimated variously at a little above and a little under 6,500,000 florins, was raised by national subscription in shares of 3000 florins. The independence of the states which constituted the United Netherlands was recognized by the creation of local boards at Amsterdam, in Zealand, at Delft and Rotterdam, Hoorn and Enkhuizen. The boards directed the trade of their own districts, and were responsible to one another, but not for one another as towards the public. A general directorate of 60 members was chosen by the local boards. Amsterdam was represented by 20 directors, Zealand by 12, Delft and Rotterdam by 14, and Hoorn and Enkhuizen also by 14. The real governing authority was the "Collegium," or board of control of 17 members, of whom 16 were chosen from the general directorate in proportion to the share which each local branch had contributed to the capital or joint stock. Amsterdam, which subscribed a half, had eight representatives; Zealand, which found a quarter, had four; Delft and Rotterdam, Hoorn and Enkhuizen had two respectively, since each of the pairs had subscribed an eighth. The seventeenth member was nominated in succession by the other members of the United Netherlands. A committee of ten was established at the Hague to transact the business of the company with the states-general. The "collegium" of seventeen nominated the governors-general who were appointed after 1608. The charter, which was granted for twenty-one years, conferred great powers on the company. It was endowed with a monopoly of the trade with the East Indies, was allowed to import free from all custom dues, though required to pay 3% on exports, and charged with a rent to the states. It was authorized to maintain armed forces by sea and land, to erect forts and plant colonies, to make war or peace, to arrange treaties in the name of the stadtholder, since eastern potentates could not be expected to understand what was meant by the states-general, and to coin money. It had full administrative, judicial and legislative authority over the whole of the sphere of operations, which extended from the west of the Straits of Magellan westward to the Cape of Good Hope.

The history of the Dutch East India Company from its formation in 1602 until its dissolution in 1798 is filled, until the close of the i7th century, with wars and diplomatic relations. Its headquarters were early fixed at Batavia in Java. But it extended its operations far and wide. It had to deal diplomatically with China and Japan; to conquer its footing in the Malay Archipelago and in Ceylon; to engage in rivalry with Portuguese and English; to establish posts and factories at the Cape, in the Persian Gulf, on the coasts of Malabar and Coromandel and in Bengal. Only the main dates of its progress can be mentioned here. By 1619 it had founded its capital in Batavia in Java on the ruins of the native town of Jacatra. It expelled the Portuguese from Ceylon between 1638 and 1658, and from Malacca in 1641. Its establishment at the Cape of Good Hope, which was its only colony in the strict sense, began in 1652. A treaty with the native princes established its power in Sumatra in 1667. The flourishing age of the company dates from 1605 and lasted till the closing years of the century. When at the summit of its prosperity in 1669 it possessed 150 trading ships, 40 ships of war, 10,000 soldiers, and paid a dividend of 40%. In the last years of the 17th century its fortunes began to decline. Its decadence was due to a variety of causes. The rigid monopoly it enforced wherever it had the power provoked the anger of rivals. When Pieter Both, the first governor-general, was sent out in 1608, his instructions from the Board of Control were to see that Holland had the entire monopoly of the trade with the East Indies, and that no other nation had any share whatever. The pursuit of this policy led the company into violent hostility with the English, who were also opening a trade with the East. Between 1613 and 1632 the Dutch drove the English from the Spice Islands and the Malay Archipelago almost entirely. The English were reduced to a precarious footing at Bantam in Java. One incident of this conflict, the torture and judicial murder of the English factors at Amboyna in 1623, caused bitter hostility in England. The success of the company in the Malay Archipelago was counterbalanced by losses elsewhere. It had in all eight governments: Amboyna, Banda, Ternate, Macassar, Malacca, Ceylon, Cape of Good Hope and Java. Commissioners were placed in charge of its factories or trading posts in Bengal, on the Coromandel coast, at Surat, and at Gambroon (or Bunder Abbas) in the Persian Gulf, and in Siam. Its trade was divided into the "grand trade" between Europe and the East, which was conducted in convoys sailing from and returning to Amsterdam; and the "Indies to Indies" or coasting trade between its possessions and native ports.

The rivalry and the hostilities of French and English gradually drove the Dutch from the mainland of Asia and from Ceylon. The company suffered severely in the War of American Independence. But it extended and strengthened its hold on the great islands of the Malay Archipelago. The increase of its political and military burdens destroyed its profits. In the early 18th century it was already embarrassed, and was bankrupt when it was dissolved in 1798, though its credit remained unshaken, largely, if its enemies are to be believed, because it concealed the truth and published false accounts. In the later stages of its history its revenue was no longer derived from trade, [S. 717] but from forced contributions levied on its subjects. At home, the directors, who were accused of nepotism and corruption, became unpopular at an early date. The company was subject to increasing demands and ever more severe regulation on the successive renewals of its charters at intervals of twenty-one years. The immediate causes of its destruction were the conquest of Holland by the French revolutionary armies, the fall of the government of the stadtholder, and the establishment of the Batavian Republic in 1798.

AUTHORITIES. The great original work on the history of the Dutch East India Company is the monumental Beschryving van oud en niew cost Indien (Dordrecht and Amsterdam, 1724), by Francois Valentyn, in 8 vols., folio, profusely illustrated. Two modern works of the highest value are: J. K. J. de Jonge, De Opkomst van het Nederlandsch Gezag in oost Indien (The Hague and Amsterdam, 1862-1888), in 13 vols. ; J. J. Meinsma, Geschiedenis van de Nederlandsche oost-Indische Bezittingen (3 vols., Delft and the Hague, 1872 - 1875). See also John Crawford, History of the Indian Archipelago (Edinburgh, 1820); Clive Day, The Dutch in Java (New York, 1904) ; Sir W. W. Hunter, A History of British India (London, 1899) ; and Pierre Bonnassieux, Les Grandes Compagnies de commerce (Paris, 1892)."

[Quelle: Encyclopaedia Britannica. -- 11. ed. -- 1910. -- Bd. 8. -- S. 716f.]

"Gründung und Organisation der Niederländisch-Ostindischen Gesellschaft Die Gründung und erste Organisation der Kompanie erfolgte durch die am 20. März 1602 von den Generalstaaten ihr erteilte Oktroi, wodurch sie auf 21 Jahre als merkantilistischer und politischer Körper privilegiert wurde. Schon durch diesen ersten Freibrief ward die Kompanie in vier Kammern geteilt, nämlich die von Amsterdam, von Zeeland, auf der Maas und von Nordholland und Westfriesland, von denen die Kammer auf der Maas wiederum die Kammern von Delft und Rotterdam, die Kammer von Nordholland aber die Kammern von Hoorn und Enkhuizen einbegriff. Der Anteil, welchen diese verschiedenen Kammern an der Kompanie haben sollten, ward so verteilt, dass die Kammer von Amsterdam die Hälfte, die von Zeeland ein Viertel und die beiden übrigen jede ein Achtel, also jede der vier Kammern, worin sich die beiden Kammern auf der Maas und von Nordholland teilten, ein Sechzehntel besitzen sollten. Die Angelegenheiten einer jeden Kammer sollen durch ihre Vorsteher oder Bewindhebber besorgt werden, die aber in der Folge bis auf zwanzig von Amsterdam, zwölf von Zeeland, und in jeder der vier übrigen Kammern bis auf sieben reduziert werden sollen. Zur Besetzung einer vakanten Direktorenstelle schlagen die übrigen Direktoren der Kammer die Kandidaten vor, aus welchen die Staaten der Provinz, wo die Kammer sich findet, einen ernennen. Ein jeder Direktor muss wenigstens für 1000 Pfund Flämisch Anteil an der Kompanie haben, ausgenommen

in den Kammern von Enkhuizen und Hoorn, wo 500 Pfund zureichen. Jede dieser verschiedenen Kammern besorgt ihre Privatangelegenheiten, ihre besonderen Ausrüstungen, Käufe und Verkäufe.Zur Besorgung der allgemeinen Angelegenheiten der Kompanie werden aus diesen 60 Vorstehern der einzelnen Kammern 17 Direktoren oder Bewindhebber gewählt, und zwar acht aus der Kammer von Amsterdam, vier aus der von Zeeland oder Middelburg, und zwei aus jeder der beiden übrigen Hauptkammern; die 17. soll durch die Kammern von Zeeland, auf der Maas und von Nordholland der Reihe nach hinzugefügt werden. Die Versammlungen dieses engeren Ausschusses der Siebzehner sollen abwechselnd sechs Jahre zu Amsterdam und zwei Jahre zu Middelburg abgehalten werden. Durch denselben wird bestimmt, wann Ausrüstungen vorgenommen werden, wann Schiffe und wie viel abgeschickt werden sollen; auch werden von ihm andere, den Handel im allgemeinen betreffende Angelegenheiten besorgt, und seine Beschlüsse müssen von den Kammern unweigerlich befolgt werden. Können die 17 Direktoren in vereinzelten Fällen nicht einig werden oder hat sich der eine über den anderen zu beklagen, so gehört die Entscheidung vor die Generalstaaten, welche auch die vakanten Stellen in diesem engeren Ausschusse besetzen, indem sie von drei ihnen vorgeschlagenen Kandidaten aus der Kammer, in der die Stelle vakant ist, einen ernennen.

An der neu errichteten ostindischen Kompanie kann jeder Untertan der Republik Anteil nehmen; jeder Teilnehmer kann aber auch schon nach den ersten zehn Jahren, beim Abschluss der Generalrechnung, aus der Gesellschaft austreten. Wie großen Anteil ein jeder an der Kompanie nehmen will, bleibt seinem Ermessen überlassen; wird aber mehr Geld angeboten, als verlangt wird, so sollen diejenigen, welche über 3000 Gulden Anteil an der Kompanie haben, ihr Kapital verhältnismäßig verringern, um den neu Eintretenden Platz zu machen.

Die Schiffe der Kompanie sollen immer da einlaufen, von wo sie ausgelaufen sind. Hat die eine Kammer Spezereien oder andere indische Waren erhalten, die andere aber noch nicht, so soll jene angehalten sein, diese auf ihr Ansuchen nach den Umständen damit zu versorgen. Drei Monate nach Absendung der Schiffe soll jedes Mal eine Berechnung von der Ausrüstung derselben verfertigt und den verschiedenen Kammern mitgeteilt werden; alle zehn Jahre aber soll nach vorhergegangener Anzeige eine Generalrechnung abgelegt werden, jedoch außerdem auch jede Kammer gehalten sein, denjenigen Provinzen oder Städten, welche einen Anteil von 50000 Gulden und darüber an der Gesellschaft haben, nach Rückkehr der Schiffe von den mitgebrachten Waren und deren Verkauf auf Verlangen Bericht abzustatten; auch können eben diese Provinzen

und Städte einen Agenten zur Wahrnehmung ihrer Geschäfte bei d Kammern bestellen.Von der Beute, welche die Schiffe der Kompanie machen werden bekommt die Admiralität jedes Mal einen Anteil; die Schiffe aber die Munition und das Geschütz der Kompanie sollen nur mit ihrer Bewilligung zum Dienste des Landes gebraucht werden können.

Die Gewürze, chinesische Seide und Kattune, welche die Gesellschaft aus Indien erhält, sollen weder bei der Einfuhr noch bei der Ausfuhr mit höheren Abgaben belegt werden, als bisher üblich war; alle Spezereien der Kompanie sollen aber nach einerlei Gewicht, dem Amsterdamer verkauft, nach dem Verkaufe gewogen und das Waagegeld davon erhoben werden.

Über die Schulden der Kompanie dürfen die Direktoren weder in ihren Personen noch in ihren Gütern angegriffen werden. Alle Befehlshaber über Flotten und einzelne Schiffe sollen angehalten sein, bei ihrer Rückkehr in das Vaterland den Generalstaaten von ihrer Reise und von der Lage der Angelegenheiten in Indien Bericht abzustatten.

Für diese Oktroi bezahlt die Kompanie an die Generalstaaten die Summe von 25000 Pfund Flämisch, das Pfund zu 40 Groten Flämisch, welche die Generalstaaten zu Ausrüstungen während der ersten Jahre zu gleichem Gewinne und gleichem Verluste mit den übrigen Interessenten einlegen.

So war die Organisation der Kompanie bei ihrer Errichtung beschaffen, und wenn gleich in der Folge in Nebenumständen verändert, blieb sie doch in der Hauptsache dieselbe. Die Oktroi der Kompanie ward von Zeit zu Zeit, so wie sie abgelaufen war, erneuert, bei welcher Gelegenheit nicht selten Veränderungen in der Organisation der Kompanie selbst vorgenommen wurden.

Aus: Saalfeld, F., Geschichte des holländischen Kolonialwesens in Ostindien, Bd. II (Göttingen 1813), S. 8-13.[Quelle: Saalfeld, Friedrich <1785 - 1834>: Geschichte des holländischen Kolonialwesens in Ostindien. -- Göttingen : Dieterich. -- Bd. 2. -- 1813. -- S. 8 - 13. -- Zitiert in: Die Entdeckung und Eroberung der Welt : Dokumente und Berichte / hrsg. von Urs Bitterli. -- München : Beck. -- (Beck'sche Sonderausgaben). -- Bd. 2. -- 1981. -- S. 90 - 92.]

Archivalien der Dutch East India Company (VOC) sind teils vernichtet worden, teils in einem schlechten Erhaltungszustand. Man findet sie zerstreut Archiven:

"A large portion of the voc 's archives have disappeared forever over the centuries as a result of bad circumstances for preservation (climate, mould, vermin), acts of war (the French occupation of the Netherlands, the annexation of voc establishments by England), or a simple lack of interest because the informative value of these archives was not recognized in the 19th century. For example, in 1821 10,000 volumes and in 1832 50,000 volumes of voc archival material were destroyed to save storage costs. What still remains of the voc archives (about four kilometres of paper) is currently kept in

- the National Archives of Indonesia (Jakarta),

- the Tamil Nadu Archives (Chennai, previously Madras, in India),

- the National Archives of Sri Lanka (Colombo),

- the Cape Town Archives Repository (South Africa), and

- the Dutch National Archives of the Netherlands (The Hague).

voc documents are also to be found in the United Kingdom

- in the India Office (London) and

- in the National Library of France (Paris, mainly maps and drawings).

But even the survival of the remaining archives is seriously threatened by a lack of resources for providing proper storage conditions, and by wear and tear resulting from the frequent consultation of the documents."

[Quelle: http://www.tanap.net/content/archives/preservation.cfm. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-26]

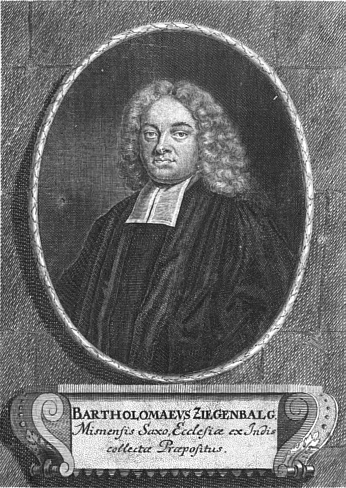

Abb.: Jan Huyghen van Linschoten (1563 - 1611)

[Bildquelle: Wikipedia, Public domain]

Übersetzung siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. -- 3. Zum Beispiel: Linschoten, Jan Huygen van <1563 - 1611>: Diary of occurrences in the Portuguese settlements in India, 1583-1588 A.D. -- Fassung vom 2008-05-22. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1503.htm

Gesamtübersetzung:

Linschoten, Jan Huygen van <1563 - 1611>: Iohn Huighen van Linschoten his Discours of voyages into ye Easte & West Indies : deuided into foure bookes. -- London : Wolfe, [1598]. -- Originaltitel: Itinerario, voyage ofte schipvaert van Jan Huygen van Linschoten naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien. -- Online: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/rbc/rbc0001/2007/2007kis1964006000001/2007kis1964006000001.pdf. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-22

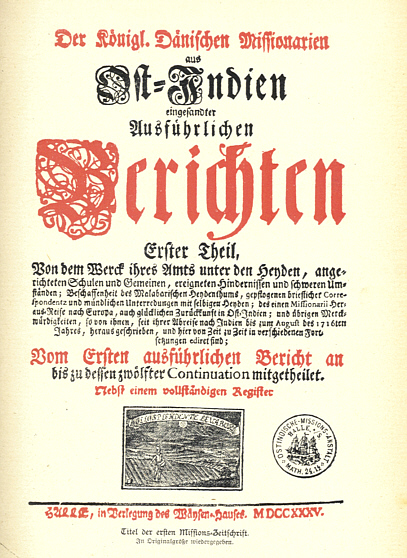

Abb.: Titelblatt

Abb.: Händler, Baniane, Bramene

[Bildquelle: a.a.O. , nach S. 78]

Abb.: Bauern und Krieger

[Bildquelle: a.a.O. , nach S. 78]

Abb.: Fischerboote

[Bildquelle: a.a.O. , nach S. 78]s

Abb.: Hochzeit in Ballagate, nördlich von Goa

[Bildquelle: a.a.O. , nach S. 78]

Abb.: Satī

[Bildquelle: a.a.O. , nach S. 78]

"Jan Huygen van Linschoten (* 1563 in Haarlem; † 8. Februar 1611 in Enkhuizen) war ein holländischer Kaufmann, Autor und Entdecker. Leben

Linschoten wurde in Haarlem geboren, lernte bei seinen Brüdern in Portugal und Spanien den Kaufmannsberuf. 1581 ging er als Sekretär des Erzbischofs von Goa nach Indien, wo er sechs Jahre verbrachte. Dort beschäftigte er sich auch mit dem Handel asiatischer Produkte und förderte ihn. Durch seine Position hatte Jan Huygen Zugang zu den geheimen Unterlagen einschließlich der Seekarten der Portugiesen, die diese über ein Jahrhundert geheimgehalten hatten. Er begann unter Bruch des in ihn gesetzten Vertrauens diese Unterlagen heimlich zu kopieren.

1587 mit dem Tod seines Gönners, des Erzbischofs von Goa, während dessen Reise nach Lissabon zum Rapport beim potugiesischen König endete das Abenteuer in Indien für Jan Huygens. Er fuhr mit dem Segler Richtung Lissabon im Januar 1589 und passierte im Mai 1589 den portugiesuschen Flottenstützpunkt mit Depot auf der Insel St. Helena.

Die Reise wurde unterbrochen durch einen Schiffbruch verursacht durch englische Piraten, so dass Jan zwei Jahre auf den Azoren verbrachte. Er landete 1592 in Lissabon und kehrte danach inseine Heimatstadt Enkhuizen zurück..

Mit Unterstützung des auf Schiffsthemen, Geographie und Reisen spezialisierten Amsterdamer Verlegers Cornelis Claesz, schrieb 1595 Jan das Buch Reys-gheschrift vande navigatien der Portugaloysers in Orienten (Reisebericht über die portugiesische Navigation im Orient). Das Werk beinhaltet eine Vielzahl von Segelrouten, nicht nur für die Strecken zwischen Portugal und Indien, sondern auch zwischen Indien, China und Japan.

Jan Huyghen schrieb auch zwei weitere Bücher, 1597 die Beschryvinghe van de gantsche custe van Guinea, Manicongo, Angola ende tegen over de Cabo de S. Augustijn in Brasilien, de eyghenschappen des gheheelen Oceanische Zees (Beschreibung der ganzen Küste von Guinea, Manicongo, Angola und zum Kap von St. Augustus in Brasilien.) und Itinerario: Voyage ofte schipvaert van Jan Huyghen van Linschoten naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien, 1579-1592 [2] (Reisebericht über die Fahrt des Seemanns Jan Huyghen van Linschoten nach portugiesisch Indien 1596).

Eine englische Ausgabe des Itinerario erschien 1598 in London, ebenso wurde im selben Jahr eine deutsche Ausgabe herausgegeben.

Nach seiner Rückkehr nach Holland schrieb Linschoten zwei Bücher (veröffentlicht 1595-96), über die Route nach Ostindien sowie über die dortigen Produkte und Erzeugnisse, Diese Bücher regten die erste holländische Ostexpedition unter Cornelis de Houtman an.

1594 begleitete Linschoten Willem Barents in die Arktis und ging 1595 mit Barents abermals nach Nowaja Semlja. Grund dieser Expeditionen war es unter anderem, auf dem Landweg über den Norden eine neue Route nach China zu finden. Diese Reisen sollten jedoch die Norddurchfahrt nach Indien entdecken; eine Beschreibung erschien 1601.

Literatur

- Van Linschoten, Jan Huyghen. The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies, Elibron Classics, 2001, 368 pages, ISBN 1-4021-9507-9, Replica of 1885 edition by the Hakluyt Society, London

- Van Linschoten, Jan Huyghen. Voyage to Goa and Back, 1583-1592, with His Account of the East Indies : From Linschoten's Discourse of Voyages, in 1598/Jan Huyghen Van Linschoten. Reprint. New Delhi, AES, 2004, xxiv, 126 p., $11. ISBN 81-206-1928-5.

[Quelle: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Huygen_van_Linschoten. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-20]

Für Quellen zu Indien in britischer Zeit (Company und Raj) ist die Institution die Abteilung "India Office Records" der British Library in London:

Webpräsenz: http://www.bl.uk/collections/orientaloffice.html. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-19

Dort findet man:

Siehe:

Abb.: TitelblattMoir, Martin: A general guide to the India Office Records. -- London : British Library, 1988. -- xvi, 331 p. : ill. ; 25 cm. -- ISBN: 0712306293

Für die Zeit von 1583 - 1619 hat William Foster eine sehr nützliche Anthologie zusammengestellt:

Early travels in India 1583 - 1619 / ed. by William Foster [1863 - 1951]. -- London [u.a.] : Milford, Oxford university press, 1921. -- xiv, 351 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- S. 125 - 187. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/earlytravelsinin00fostuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-19. -- "Not in copyright."

Darin werden Berichte zitiert von:

| Name | Lebensdaten | Auf Indienreise |

|---|---|---|

| Ralph Fitch | 1583 - 1591 | |

| John Mildenhall | 1599 - 1606 | |

| William Hawkins | 1608 - 1613 | |

| William Finch | 1608 - 1611 | |

| Nicholas Withington | 1612 - 1613 | |

| Thomas Coryat | 1612 - 1617 | |

| Edward Terry | 1616 - 1619 |

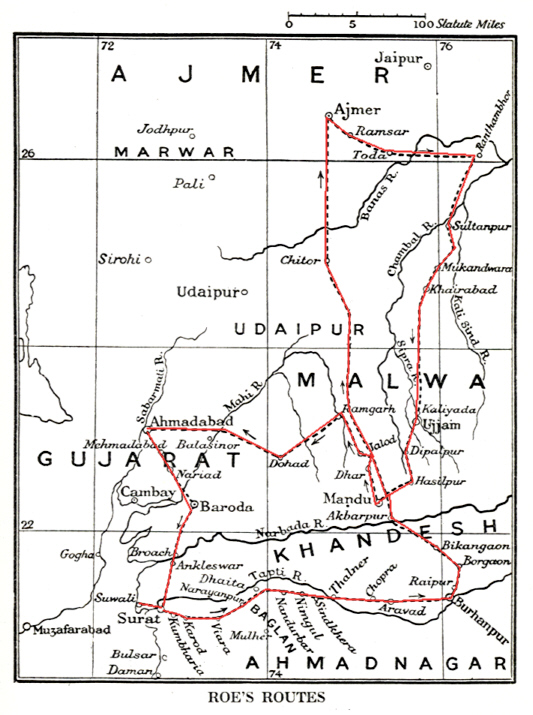

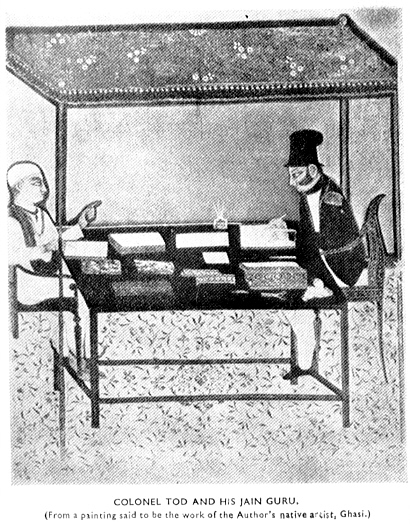

William Foster hat auch die Berichte von Thomas Roe neu herausgegeben, der 1615 - 1619 als Botschafter von König James am Hof des Großmogul weilte:

Roe, Thomas <1581?-1644>: The embassy of Sir Thomas Roe to India, 1615-19, as narrated in his Journal and correspondence / edited by William Foster [1863 - 1951]. -- New and rev. ed. -- London, Oxford University Press, 1926. -- lxxix, 532 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm.

"FITCH, RALPH (fl. 1583-1606), London merchant, one of the earliest English travellers and traders in Mesopotamia, the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, India proper and Indo-China. In January 1583 he embarked in the "Tiger" for Tripoli and Aleppo in Syria (see Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act I. sc. 3), together with J. Newberie, J. Eldred and two other merchants or employees of the Levant Company. From Aleppo he reached the Euphrates, descended the river from Bir to Fallujah, crossed southern Mesopotamia to Bagdad, and dropped down the Tigris to Basra (May to July 1583). Here Eldred stayed behind to trade, while Fitch and the rest sailed down the Persian Gulf to Ormuz, where they were arrested as spies (at Venetian instigation, as they believed) and sent prisoners to the Portuguese viceroy at Goa (September to October). Through the sureties procured by two Jesuits (one being Thomas Stevens, formerly of New College, Oxford, the first Englishman known to have reached India by the Cape route in 1579) Fitch and his friends regained their liberty, and escaping from Goa (April 1584) travelled through the heart of India to the court of the Great Mogul Akbar, then probably at Agra. In September 1585 Newberie left on his return journey overland via Lahore (he disappeared, being presumably murdered, in the Punjab), while Fitch descended the Jumna and the Ganges, visiting Benares, Patna, Kuch Behar, Hugli, Chittagong, &c. (1585-1586), and pushed on by sea to Pegu and Burma. Here he visited the Rangoon region, ascended the Irawadi some distance, acquired a remarkable acquaintance with inland Pegu, and even penetrated to the Siamese Shan states (1586-1587). Early in 1588 he visited Malacca; in the autumn of this year he began his homeward travels, first to Bengal; then round the Indian coast, touching at Cochin and Goa, to Ormuz; next up the Persian Gulf to Basra and up the Tigris to Mosul (Nineveh); finally via Urfa, Bir on the Euphrates, Aleppo and Tripoli, to the Mediterranean. He reappeared in London on the 29th of April 1591. His experience was greatly valued by the founders of the East India Company, who specially consulted him on Indian affairs (e.g. 2nd of October 1600; 29th of January 1601; 31st of December 1606).

See Hakluyt, Principal Navigations (1599), voj. ii. part i. pp. 245-271, esp. 250-268; Linschoten, Voyages (Itineraris), part i. ch. xcii. (vol. ii. pp. 158-169, &c., Hakluyt Soc. edition) ; Stevens and Birdwood, Court Records of the East India Company 1599-1603 (1886), esp. pp. 26, 123; State Papers, East Indies, &c., 1513-1616 (1862), No. 36; Pinkerton, Voyages and Travels (1808-1814), ix. 406-425."

[Quelle: Encyclopaedia Britannica. -- 11. ed. -- Bd. 10. -- 1910. -- S. 439]

Text:

Early travels in India 1583 - 1619 / ed. by William Foster [1863 - 1951]. -- London [u.a.] : Milford, Oxford university press, 1921. -- xiv, 351 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- S. 1 - 47. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/earlytravelsinin00fostuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-19. -- "Not in copyright."

Auswahl siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. --4. Zum Beispiel: Ralph Fitch, 1583 - 1591. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1504.htm

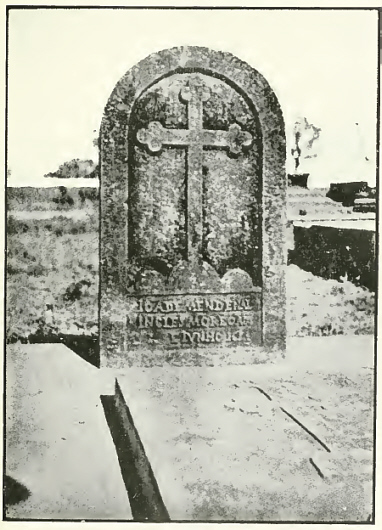

Abb.: John Mildenhall's Grabstein in Agra, Römisch-katholischer Friedhof

[Bildquelle: a.u.a.O., nach S. 50]

Text:

Early travels in India 1583 - 1619 / ed. by William Foster [1863 - 1951]. -- London [u.a.] : Milford, Oxford university press, 1921. -- xiv, 351 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- S. 48 - . -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/earlytravelsinin00fostuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-19. -- "Not in copyright."

Auswahl siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. --5. Zum Beispiel: John Mildenhall, 1599 - 1606. --http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1505.htm

Text:

Early travels in India 1583 - 1619 / ed. by William Foster [1863 - 1951]. -- London [u.a.] : Milford, Oxford university press, 1921. -- xiv, 351 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- S. 60 - 121. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/earlytravelsinin00fostuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-19. -- "Not in copyright."

Auswahl siehe:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. --6. Zum Beispiel: William Hawkins, 1608 - 1613. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1506.htm

"FINCH, WILLIAM (d. 1613), merchant, was a native of London. He was agent to an expedition sent by the East India Company, under Captains Hawkins and Keeling, in 1607 to treat with the Great Mogul. Hawkins and Finch landed at Surat on 24 Aug. 1608. They were violently opposed by the Portuguese. Finch, however, obtained permission from the governor of Cambay to dispose of the goods in their vessels. Incited by the Portuguese, who seized two of the English ships, the natives refused to have dealings with the company's representatives. During these squabbles Finch fell ill, and Hawkins, proceeding to Agra alone, obtained favourable notice from the Emperor Jehanghire. Finch recovered, and joined Hawkins at Agra on 14 April 1610. The two remained at the mogul's court for about a year and a half, Finch refusing tempting offers to attach himself permanently to the service of Jehanghire. Hawkins returned to England, but Finch delayed his departure in order to make further explorations, visiting Byana and Lahore among other places. Finch made careful observations on the commerce and natural products of the districts visited. In 1612 the mogul emperor confirmed and extended the privileges he had promised to Finch and Hawkins, and the East India Company in that year set up their first little factory at Surat. Finch died at Babylon on his way to Aleppo from drinking poisoned water in August 1613." [Purchas ; Prévost's Histoire de Voyages ; Dow's Hist, of Hindostan ; Cal. State Papers, East Indies, 1513-1617, Nos. 449, 649, 650 ]

J. B-Y. [James Burnley]"

[Quelle: Dictionary of national biography / ed by Sidney Lee. -- London : Smith, Elder. -- Bd. 19. -- 1889. -- S. 20]

Text:

Early travels in India 1583 - 1619 / ed. by William Foster [1863 - 1951]. -- London [u.a.] : Milford, Oxford university press, 1921. -- xiv, 351 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- S. 122 - 187. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/earlytravelsinin00fostuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-19. -- "Not in copyright."

Ebenfalls:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. --7. Zum Beispiel: William Finch, 1608 - 1611. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1507.htm

Text:

Early travels in India 1583 - 1619 / ed. by William Foster [1863 - 1951]. -- London [u.a.] : Milford, Oxford university press, 1921. -- xiv, 351 S. : Ill. ; 19 cm. -- S. 188 - 233. -- Online: http://www.archive.org/details/earlytravelsinin00fostuoft. -- Zugriff am 2008-05-19. -- "Not in copyright."

Auszug:

Payer, Alois <1944 - >: Quellenkunde zur indischen Geschichte bis 1858. -- 15. Frühe europäische Quellen und Quellen aus der Zeit der East India Companies. --8. Zum Beispiel: Nicholas Withington, 1612 - 1616. -- http://www.payer.de/quellenkunde/quellen1508.htm

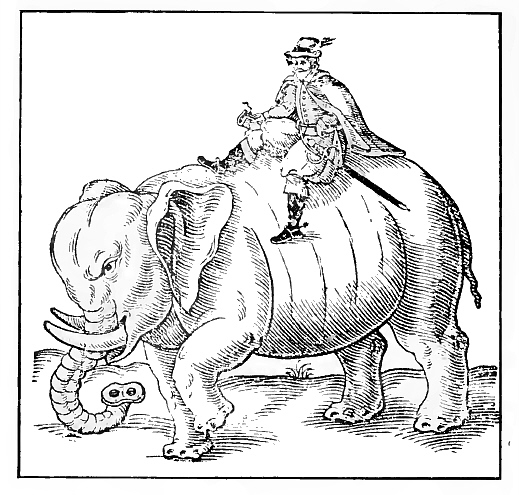

Abb.: Coryat auf einem Elefanten

[Bildquelle: a.u.a.O., nach S. 248]